Abstract

The t-tubular system plays a central role in the synchronisation of calcium signalling and excitation-contraction coupling in most striated muscle cells. Light microscopy has been used for imaging t-tubules for well over 100 years and together with electron microscopy (EM), has revealed the three-dimensional complexities of the t-system topology within cardiomyocytes and skeletal muscle fibres from a range of species. The emerging super-resolution single molecule localisation microscopy (SMLM) techniques are offering a near 10-fold improvement over the resolution of conventional fluorescence light microscopy methods, with the ability to spectrally resolve nanometre scale distributions of multiple molecular targets. In conjunction with the next generation of electron microscopy, SMLM has allowed the visualisation and quantification of intricate t-tubule morphologies within large areas of muscle cells at an unprecedented level of detail. In this paper, we review recent advancements in the t-tubule structural biology with the utility of various microscopy techniques. We outline the technical considerations in adapting SMLM to study t-tubules and its potential to further our understanding of the molecular processes that underlie the sub-micron scale structural alterations observed in a range of muscle pathologies.

Key Words: cardiac muscle, skeletal muscle, t-tubules, excitation-contraction coupling, super-resolution microscopy, human, rat, mouse, rabbit, horse

Cardiac myocytes and skeletal muscle fibres are among the largest cell types in vertebrate species. Ventricular myocytes can be ~20 µm in width and >100 µm long while skeletal muscle fibres are found in diameters in excess of 100 µm, extending over millimetres to centimetres from tendon to tendon. Forceful contraction of such striated muscle relies on the rapid and synchronised opening of the primary calcium (Ca2+) release channels of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) - the ryanodine receptors (RyRs).1 RyRs are clustered into dense arrays adjacent to t-tubules in both cardiac2 and skeletal muscle.3 A series of tubular membrane invaginations of the surface sarcolemma, collectively known as the transverse tubular system (t-system or t-tubules), is responsible for the synchronisation of excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling. They achieve this by the delivery of the excitation (action potential) to the Ca2+ release sites in junctions with terminal SR either at the z-line (in mammalian myocardium) or at the A-band boundary (in mammalian skeletal muscle).4 Junctions between t-tubules and nuclear envelope/ER also facilitate their putative role in excitation-transcription (E-T) coupling5 via pathways like store-operated Ca2+ entry dependent NFAT activation,6,7 IP3-receptor/Calmodulin Kinase-II mediated nuclear signalling8 and β-adrenergic stimulation.9 The structure of the t-tubules can greatly affect their roles in the above signalling mechanisms; for example, the widespread network structure of the t-system determines how well it synchronises the Ca2+ release in the muscle cell interior. Similarly, the tortuosity and local tubule diameters can also affect tubular luminal ion concentrations and effectively regulate t-system excitability and conduction properties.10 Models that simulate such ion/protein dynamics within a geometrically accurate environment are particularly useful for predicting the structural constraints on EC coupling.11 This approach has been used recently with models of tubular ionic movements that have been constructed either solely on microscopy data of t-tubules12 or a combination of experimentally-traced and simulated t-tubule features.13 Therefore we see such models as a primary motivator for the microscopy analysis of t-tubules.

Microscopy techniques that allow the visualisation of t-tubules either for accurate structural measurements (useful for modelling its function) or for functional studies have therefore been an integral part of muscle biology for well over 100 years (see reviews of history.14 Some of the pioneering work carried out since the 1950s, used high-contrast staining methods combined with electron microscopy (EM). In more recent decades, fluorescence techniques that are compatible with live cell imaging have become popular (see discussion below). The main appeal in fluorescence microscopies includes high-contrast images, high specificity of fluorescent labelling methods and 3D imaging applications with optical sectioning. However, the resolution achievable with these methods is fundamentally limited to approximately half the wavelength of the light (e.g. 250 nm) due to the wave properties of light (i.e. diffraction).15,16 In practical terms, we observe a considerable loss of the sub-micron scale features of muscle structure in conventional fluorescence micrographs, especially of t-tubules. Several recent optical microscopy methods that promise EM-like resolution, high specificity in mapping molecular targets while circumventing this “diffraction-limit” are optical super-resolution imaging (see recent reviews,17,18) In the following we discuss the application of one of these approaches, single molecule localisation microscopy (SMLM,) for visualising multi-scale morphologies of cardiac and skeletal muscle t-tubules, a technique which we have adopted in our own work.

Localisation microscopy: breaking the diffraction limit

SMLM utilises the stochastic photo-switching or modulation of individual fluorophore emission to localise individual fluorophores within the sample. This is typically achieved with a combination of light-induced photoactivation, photobleaching and/or supplementing the sample immersion medium with a ‘switching buffer’ that may consist of oxygen scavenging species and/or reducing agents (e.g. thiols).19 Photoswitching individual fluorophores typically yields a diffraction-limited spot of fluorescence with an intensity profile that reflects the point spread function (PSF) of the microscope (often approximated by a 2D-Gaussian), lasting up to a few frames in a fast and sensitive camera. In-focus fluorophore positions can be localised at nanometre-accuracy by fitting these 2D spots (“events”) with a model that approximates the PSF but one must be careful that the distance between adjacent events is larger than the minimum resolvable distance of the microscope (i.e. > half the wavelength) to avoid distortions by overlap. The resultant fluorophore coordinates can be reconstructed into greyscale images that, similar to standard fluorescence micrographs, report intensity in proportion to the local event densities20,21 but at a resolution of 10-30 nm. Multicolour SMLM has also been possible by spectral unmixing of fluorophore emissions.22,23) Chromatically separating the emissions of multiple fluorophores and examining the ratios of their respective emissions in two channels provides an emission ratio that is typically unique to each fluorophore – which can then be used for assigning the spectral identity to a given event.22 The primary appeal of this method to the muscle biology community is that it is compatible with a range of commercially available organic fluorophores (e.g. AlexaFluor and cyanine dyes), membrane dyes (e.g. DiI), genetically expressed reporters such as GFP, mEos (see a partial list of common SMLM markers: Table 2 of17). Depending on the mechanism of photoswitching and/or labelling the SMLM technique may be known by one of many acronyms such as dSTORM, PALM, GSDM (see Table 1 of17) for a summary).

Table 1.

Features of localisation microscopy techniques and their advantages and limitations towards t-tubule imaging in muscles

| Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Nanometre resolution across sub-millimetre sized areas | >10 fold improvement over diffraction-limited fluorescence techniques Direct measurement of subcellular structures Minimises over-estimation of protein co-localisation due to optical blurring |

Resolution is only limited by detectable light yield from a single event, size of the fluorescent label/complex and the local density of the fluorescent probes. |

| Can be performed in aqueous and non-aqueous sample environments | Compatible with correlative imaging with EM and other light microscopies Minimise shrinkage artefacts Customisable mounting medium to optimise photoswitching |

|

| Fluorophore photoswitching kinetics are adjustable | Can be modulated by excitation intensity, chemical constituents in the mounting buffer and/or a secondary activation laser. Optimal photoswitching rate can be achievable depending on the densities of the underlying fluorophores in the samples. Ability to improve localisation accuracy by avoiding simultaneous photoswitching of overlapping fluorophores or suppressing background/out of focus molecules |

Abbreviating the fluorophore ON time further than a few milliseconds reduces photon yield, compromising the localisation accuracy. Prolonging the ON and/or OFF time prolongs the image acquisition time and the image file size. The latter may limit the speed of real-time image reconstruction. Potentially many parameters and variables to chose from; may be confusing to non-specialist users |

| Image is generated based on localised map of fluorophore position and localisation error | Images are (in principle) quantifiable for in situ biochemical analysis Minimises geometry-dependent non-linearities in fluorescence intensity in diffraction-limited imaging Robust clustering or image binerisation methods based on local event densities |

Quantifiability of image data hinges on accurate localisation of overlapping events and correcting for local fluorophore density dependence of repeated photoswitching or limited yieldsof the molecules. |

| Single molecule events consist of a unique spectral signature | Spectral filtering can ‘unmix’ between multiple fluorophores or autofluorescence to achieve greater specificity in visualising the target structure. | |

| Reconstructed greyscale images are “background free” | More robust binarisation of images Local intensity is less dependent on gradients/patterns in the background compared to standard fluorescence microscopies |

Any background fluorescence limits localisation accuracy (hence, resolution) Non-specific binding of fluorescent probes or antibodies are indistinguishable from specific binding; hence requiring appropriate control experiments (an issue common to all marker binding methods) |

| Ability to resolve structures in “thick” samples | Compatible with immunocytochemistry and tissue samples sectioned with standard microtomes (typically 10-20 microns in thickness) | Light scattering, spherical aberration and out of focus fluorescence typically seen in thick samples diminish the localisation accuracy. Therefore, thin samples are ideal (e.g. cultured cells). The native t-tubule structure is poorly preserved in cultured myocytes or myoblasts. |

| 3D localisation | Suitable for resolving the three-dimensional complexities of t-tubles | Thin samples (<10 microns) with dense t-tubule labelling with low background fluorescence work best. |

| Photoswitchability of endogenous, genetically encoded or introduced fluorophores in aqueous physiological saline environments | Compatible with real-time imaging t-tubules in living/functional preparations Conducive to photo-tracking of labelled receptor/protein/lipid mobility in t-tubules |

Photodamage to the cells/fibres from prolonged intense light exposure and oxidants generated from the photoswitching (but yet to be quantified if any worse than other imaging approaches) Spatial distortions from drift or local contractures of the cells are difficult to correct for. Visualisation of fast events (protein trafficking, t-tubule membrane remodelling) may be limited by fluorophore photobleaching and photoswitching rates. |

The simplicity of this concept meant that an appropriate sample could be imaged with a basic fluorescence microscope and a camera sufficiently sensitive to record single molecule events. Total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopes, but used with a sub-critical beam angle24 are suitable for imaging muscle tissue that are often thicker than the cultured cell samples that are typically used in the majority of SMLM studies to date. This configuration allows an effective optical sectioning of the sample enabling the imaging of structures further away from the coverslip with an axial resolution similar to confocal microscopy. Electron multiplying charged coupled devices (EMCCD) or scientific CMOS cameras are currently the most widely used detectors for these experiments because of their high sensitivity, comparatively low read-noise and the high frame rates that can be obtained.25 Mapping the full complement of fluorophores within an image region may require acquisition of 10-50,000 frames over 5-30 minutes depending on the photoswitching rates. The computationally demanding features of fluorophore detection, fitting (localisation), spectral unmixing and reconstruction algorithms often require a powerful computer (readily available and very affordable as compared to microscope and camera hardware) with large storage capacity that can hold the large image sequences. However, increasingly, open-source or free analysis software packages are becoming available (e.g. rapid STORM26), which should help introduce non-experts to this approach and commercial systems are also available.

The use of SMLM has grown exponentially over the 8 years since its initial proof of principle (see recent reviews discussing the expansion of SMLM20,27,28). Additional to the obvious improvement in the resolution, images are often “background free” because fluorophore localisation above a standing non-uniform background implicitly exclude any sarcomeric autofluorescence patterns (e.g. mitochondria).22 The stochastic nature of the photoswitching means that the fluorophore coordinates can be used for quantitative analysis of the underlying protein/fluorophore densities or distances to the surrounding structures, although fully quantitative approaches need to carefully avoid artefacts, such as overcounting and failing to reject multi-emitter events.29 Overestimation of co-localising fractions between two proteins is avoided (to a larger extent) with the superior resolution while image binarisation tends to be more robust.30 Combined with lipophilic membrane dyes such as DiI, volumetric dyes (e.g. dextran conjugates) or extracellular markers (e.g. wheat germ agglutinin), SMLM provides potentially a very convenient method of resolving the structure or tracking any remodelling of t-tubules of living muscle preparations at nanometre resolution.31 Further advancements in the field include 3D SMLM methods that, with fairly straightforward optical modifications, can produce 3D super-resolution images with >10 fold finer axial resolution compared to confocal images32,33 that can be particularly useful for imaging a 3D structure like the t-system.

Achieving the super-resolution often promised by SMLM, however, requires consideration of several aspects with respect to sample preparation and imaging protocols. The effective resolution in the image is ultimately dependent on the localisation error and the effective labelling density of the underlying structure. The localisation error is approximately proportional to σ /√N where σ is the standard deviation of the best fit Gaussian (i.e. the diameter of the PSF) and N the number of photons collected from the event.34 Maximising N is typically achieved by increasing the excitation, integrating events lasting multiple frames, chemically increasing the lifetime of the fluorophore events and generally using an optical detection path that aims to minimise light losses. However, in a sample that has substantial background fluorescence (e.g. very high labelling densities or out of focus fluorescence, typically in ‘thick’ samples) the localisation error rises with the background intensity.34 Therefore, samples that are ultra-clean or ‘thin’ are ideal for SMLM performed with TIRF or Light-sheet microscopy.24 However, we have demonstrated that SMLM is compatible with isolated cardiomyocytes,30, 35,36 single skeletal muscle fibres37 and ‘thin’ (by confocal standards, i.e. 5-10 µm) tissue sections of ventricular32,38 and skeletal muscle3 to achieve ~30 nm resolution.

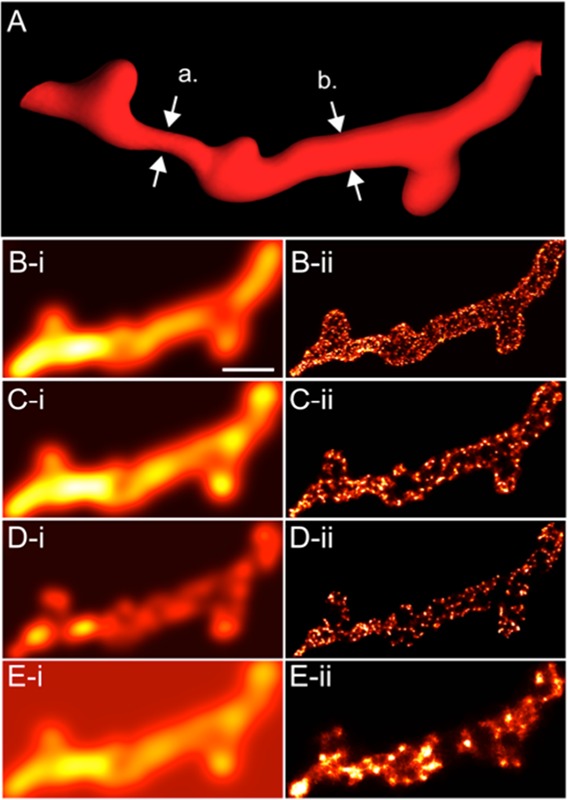

A perhaps more serious and frequently encountered issue is “under-labelling” which reduces the detectability of nanoscale features of t-tubules. This becomes a particularly concerning issue during 3D SMLM where sufficient fluorophore densities in the axial dimension are also vital towards a super-resolution 3D image. Fig. 1 illustrates a simulation that summarises the effect of labelling density and background fluorescence on the reconstructed super-resolution image. It is noteworthy that in an equivalent confocal micrograph under each condition, the structural features appear often unaffected and mainly result in a dimmer image (which will, however, affect the signal-to-noise ratio, but may be overcome to some extent by “turning up the laser” or increasing integration time). This underscores the greater emphasis that SMLM places on the quality of the samples for achieving super-resolution. Table 1 collates a summary of (our view on) advantages, technical considerations and limitations of SMLM with a particular view towards imaging in muscle.

Fig 1.

Simulating the effect of labelling densities and background fluorescence on diffraction-limited and SMLM images. (A) A phantom t-tubule with a varying diameter (a = 130 nm and b = 280 nm) and a 20 nm-thick layer of fluorescent markers (similar to combined thickness of a layer of primary and secondary antibodies bound to a t-tubular protein; e.g. caveolin-3) is simulated in (i) confocal micrographs and (ii) typical 2D dSTORM. Images were simulated for labelling densities of (B) 0.12/nm2, typical of very high fluorophore densities, (C) 0.008/nm2, typically achieved in experimental samples and (D) 0.0005/nm2 to simulate a 15-fold poorer labelling than typical. Notice the gradual loss of detail in the dSTORM images with the diminishing labelling density and little observable difference between the confocal images (B-i & C-i). To simulate the effect of higher background intensity (E), the background intensity was set to 50% of the foregraound intensity and a foreground labelling density comparable to the simulation in panel-C. Notice the lack of detail on the dSTORM image (E-ii compared to C-ii) while little change is seen in the morphologies in the confocal images (E-i compared to C-i). Scale bar: 500 nm.

Progress in sub-micron-scale microscopy of cardiac and skeletal muscle t-tubules

Historically, electron microscopy (EM) data have been instrumental to understanding of the fine ultrastructure of muscle, especially t-tubules. Optical microscopy techniques on the other hand have offered the muscle biologist a means for high contrast, 3D images over comparatively large regions of fibres (or tissue), ideal for high spatial sampling (many sarcomeres or large portions of the muscle cell width) and 3D visualisation of the structures of the t-system in the sub-micron to sub-millimetre scales, however, with the resolution limitations as discussed above. Therefore, EM, which is generally not compatible with live-cell imaging and often has limited molecular specificity (but excels at imaging membranes with suitable staining protocols), has remained the primary method to resolve its detailed features.

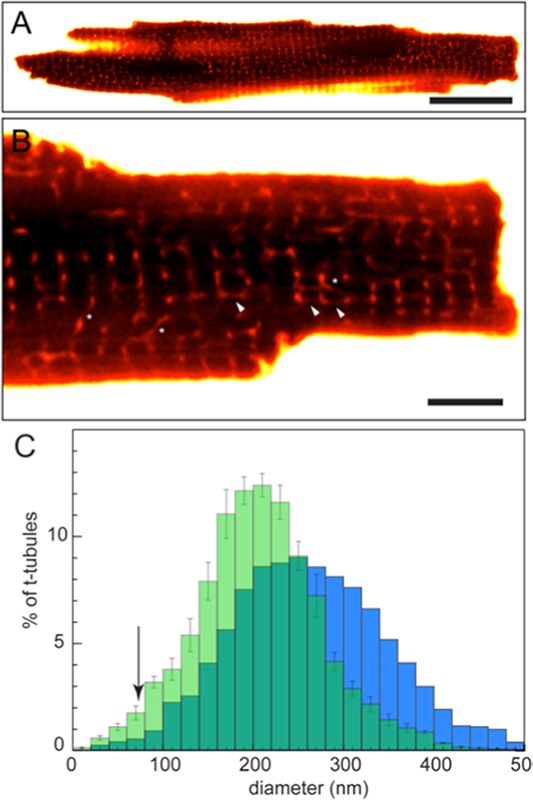

Soeller and Cannell39 used two-photon (diffraction-limited) micrographs (similar to Fig 2A &B), digital deconvolution and the entry of a volumetric dye (membrane impermeable fluorescein-dextran) into the rat cardiac t-system (previously used by Endo40) to overcome the lack of spatial detail in fluorescence micrographs to some degree. Whole-cell images like these (Fig 2A) were instrumental in observing t-tubules that were predominantly transverse in their orientation but can also run in longitudinal and oblique directions (see magnified image; Fig 2B). By calibrating the fluorescence intensity to the local tubule volume and geometry, they were able to characterise the full distribution of the diameters of t-tubules, many of which were well below the diffraction-limit (blue bar graph in Fig 2C). Direct measurements from antibody-labelled super-resolution images (unpublished data) have since validated these measurements (green bar graph, Fig 2C). A similar method has been used by Savio-Galimberti et al.41 to characterise the t-tubules of rabbit ventricular myocytes that were typically twice as wide as rat t-tubules and mostly resolvable with confocal microscopy. Their data were the first optical images indicating localised dilatations on t-tubules and flattened topologies that may act as reservoirs to compensate for potential ionic accumulations and/or depletion.

Fig 2.

Confocal fluorescence microscopy of t-tubules of isolated living myocytes. (A) A whole cell longitudinal confocal image of a rat ventricular myocyte immersed in a dextran-linked fluorescein solution similar to the method used by Soeller and Cannell.38 (B) Magnified view illustrates the membrane impermeable dextran-fluorescein entry into the t-tubules reporting local tubule geometry and volume against the dark background of the myoplasm. Note the oblique (asterisk) and longitudinal tubules (arrowheads) that are clearly visible with this approach. (C) The percentage distribution of local tubule diameter estimates from such diffraction-limited data (blue bars; Soeller & Cannell) has a similar mean to that based on dSTORM data. Note the limited measurements (poor detection) of tubule diameters that are <70 nm in the diffraction-limited analysis (arrow), while the dSTORM analysis is able to detect >2-times the fraction of tubules narrower than 70 nm. Scale bars: A: 20 µm, B: 5 µm.

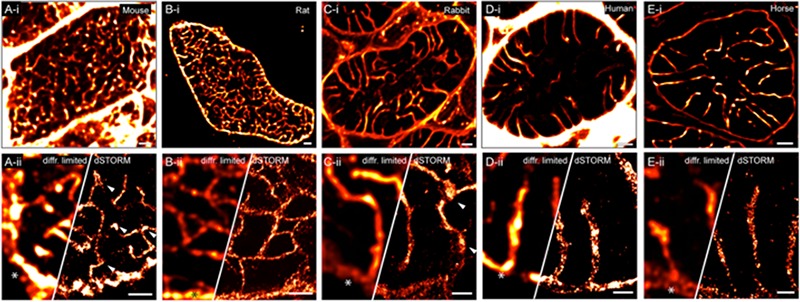

Similar structures can be better resolved by imaging the myocytes in an “end-on” orientation (i.e. in transverse optical sections)42 which limits artefacts that may be introduced into the images by the asymmetry of the confocal point spread function (PSF). The transverse view of the t-tubule network across the cell widths in these approaches, in our experience, provides a clearer view of the tubule geometries. The main benefits of this approach are the superior resolution and the greatly minimised geometry dependent intensity variations in the transverse tubules (see discussion in43); therefore we suggest it should be used in preference over the longitudinal (“side-on”) method of imaging t-tubules and dyads in every muscle type that has a predominantly transverse layout for these structures. We used this method to quantify the local variations in the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger density in the ttubules of rat myocytes and identified a small fraction of non-dyadic RyR clusters.43 This protocol also allowed us to trace the zigzag branchings of t-tubules in regions of misregistrations between adjacent myofibrils and measure the near-4-fold greater t-tubule density and branching in the rat t-system, which, similar to mouse, is highly tortuous and reticular (Fig 3 A&B) compared to the spoke-like t-tubules that project towards the cell centre in ventricular myocytes of larger mammals including human44) (Fig 3C-E). Intriguingly, extensive t-tubular networks have also been observed in atrial myocytes of larger mammals such as horse, sheep, cow and human.45 Analysis of transverse fluorescence images of t-tubules in these atrial samples has revealed a weak correlation between tubule density and cell size; however it is yet to be understood why a near-complete lack of tubules is seen in the atria of smaller animals (e.g. mouse, rat).45 Here it is noteworthy that one of the prime limitations in fluorescence microscopy of t-tubules in fixed samples (typically resorting to immunocytochemistry) is the lack of a gold-standard stain that reports the full extent of the t-system. Poor retention of fixable membrane stains in cardiac t-tubules fixed with formaldehyde-based fixatives and the incomplete staining patterns with common labels (e.g. caveolin-3 or wheat germ agglutinin) have led us to propose that cardiac t-tubules in small animals (e.g. rat and mouse) are often better visualised with the combined fluorescence of two or more independent stains.44

Fig 3.

Comparison of micron- and nanometre-scale morphologies in adult mammalian cardiac t-systems. Transverse (i) Confocal and (ii) dSTORM images blurred with a 2D Gaussian PSF equivalent to a confocal PSF (left panels) and super-resolution image (right). Shown myocytes of (A) C57-BL/6 mouse and (B) Wistar rat were stained with a combination of NCX1 and CAV3. Fixed ventricular tissue sections from (C) New Zealand White rabbit, (D) Human (54-year old donor with normal echocardiogram) and (E) Horse (12-year old female New Forest pony) were stained with fluorescent wheat germ agglutinin to visualise the t-tubules. Note the nanometre- and micron-scale t-tubule dilatations in mouse and rabbit myocytes respectively (arrowheads). Cell surface in each example is indicated by asterisks. Scale bars: i-panels: 2 µm; ii: 1 µm.

More recent advancements in t-tubule imaging have been achieved both with the newer optical super-resolution microscopy techniques and more recent EM volume imaging approaches. An example is tomographic EM that has enabled 3D reconstructions which have been instrumental in resolving the finer features of t-tubules. These include nanometre-scale reconstructions of the t-tubule membranes in dyad regions to visualise the contact areas of RyRs with transverse46,47 and longitudinal tubules.48 Serial block face scanning EM (SBF-SEM) more recently has produced 3D reconstructions of the t-system in cardiomyocytes from rat and sheep ventricles at nanometre resolution.49 These data volumes demonstrate the relative differences in the tubule widths between sheep and rat t-tubules and, for the first time, resolve local variations in tubule diameters that were previously not directly visualised in fluorescence micrographs due to the diffraction limit (although see our previous discussion of rat t-tubules,39 Sache et al.41 of rabbit; see arrowheads in Fig 3C-ii for example dSTORM image). Similar nanometre-scale dilatations were observed in the junctional segments of mouse ventricular t-tubules using tomographic EM and dSTORM data50 (arrowheads in Fig 3A-ii). More recent tomographic reconstructions suggest that these may be folds of the t-tubules that putatively improves the contact between RyR and the trigger.51 While no data are shown to clarify how consistently these folds are observed among all of the dyads or their role in EC-coupliong, these structures are apparently lost or not formed in the absence of Bin-1, resulting increased arrhythmogenesis.51 Alternative methods for imaging the nanoscale ultrastructure of t-tubules have been based on other optical super-resolution methods. Wagner et al.52 used STED microscopy to resolve the fine details of t-tubules stained in live mouse ventricular myocytes with the lipophilic membrane dye di-8-ANEPPS. <60 nm in-plane resolution provided them with high-contrast images of the tubule membranes (and hollow cores) that were relatively convenient to analyse with automated algorithms.

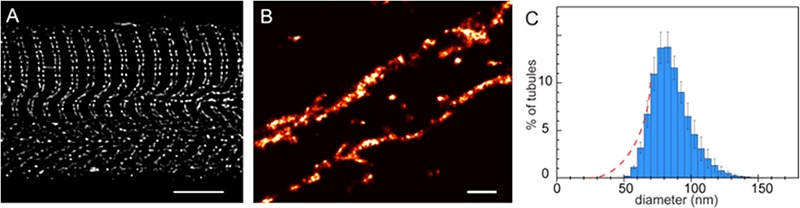

The skeletal muscle t-system, in comparison has classically been visualised in great detail in pioneering EM studies that used high-contrast membrane stains (e.g. Golgi stain).53 Characteristic of the mammalian skeletal muscle t-system are the doublets of tubules within each sarcomere (located at each A-band boundary; see Fig 4A), each with a flattened cross-sectional shape and flanked by two SR terminal cisterns in a structure classically known as a triad. In a recent study, we reconstructed the 3D structure of the rat fast-twitch fibre t-system using the calibrated confocal fluorescence of a membrane impermeable dye trapped within sealed t-tubules (Fig 4B).54 These reconstructions demonstrated a dense network of t-tubules lining the nuclear envelope, that were previously shown to bear junctions55 that may be important in excitation-transcription coupling. These 3D data volumes of mammalian muscle were also useful for estimating a mean tubule diameter of ~ 86 nm, which predicted a ~38 nm longitudinal width and a 132 nm transverse (flattened) on the assumption that these tubules had a cross-sectional aspect ratio of 3.5. These values were comparable with transverse widths of triads measured using dSTORM images of RyR1 labelling in rat EDL fibres.3 However, one major technical difficulty using the confocal imaging approach are the 3-4 times narrower diameters of the skeletal muscle t-tubules in comparison to the cardiac equivalent. As a result, the small tubular volumes and associated noise in confocal micrographs appeared to increase the uncertainty of detection (and correct calibration) of a small fraction of tubules that were on average narrower than 40 nm (in mean width; see Fig 4C). This limitation would be circumvented by using a super-resolution microscopy method as detailed above, which should overcome this size-dependent detection bias. We subsequently used dSTORM for the first time in a recent study to characterise the nano-architecture of the previously detected subsarcolemmal components56 of the mammalian skeletal muscle t-tubules that had been filled with fixable fluorescent dextrans.37 Facilitating the fast propagation of action potentials,57 buffering ion exchange between the external space and deeper t-tubules and/or communication with the tubular extensions of subsarcolemmal mitochondria (recently visualised with deconvolved confocal micrographs and focused ion beam SEM reconstructions58) are all possible functional roles of these tubules. dSTORM images of deeper tubules in rat skeletal muscle have since emerged,59 although quantitative measurements are yet to be described.

Fig 4.

Visualisation of t-tubules in mammalian skeletal muscle. (A) A longitudinal confocal micrograph of a “mechanically skinned” rat extensor digitorum longus (EDL) fibre with membrane impermeable dye trapped in the t-system. (B) A dSTORM image of t-tubule organisation in the flanks of a single z-line of a similar fibre. T-tubules were filled with fixable dextran and the fibre was skinned to trap the dye prior to fixation. (C) Shown is a percentage histogram of the mean diameter of t-tubules in adult rat EDL fibres calculated by modelling the tubules as flattened cylinders. Notice the left-skewed shape of the histogram, which is a result of the poor detection efficiency of tubules with a mean diameter narrower than ~40 nm. More tubules are expected to be detected with smaller diameters (expected fractions approximated by dashed lines) with the super-resolution method. Scale bars: A: 5 µm; B: 0.5 µm.

Altered t-tubule structure in health and disease: motivating renewed interest in t-tubules

One reason why there has been a resurgent interest in the structural imaging of t-tubules, using most of the imaging modalities mentioned above, are observations of changes in the tubule structure in a range of pathophysiological conditions. Loss of t-tubule density and concurrently diminished Ca2+ signalling have been observed in a wide range of human60-62 and animal63-65 cases of heart failure. Fluorescence (confocal) microscopy studies have commonly reported abnormalities that include focal loss of tubules (detubulation), loss of transverse elements of the t-system, a concurrent proliferation of longitudinal tubules and/or a general loss in spatial regularity of the t-system in a range of cardiac pathologies. These include myocardial hypertrophy,66,67 hypertensive cardiomyopathy,63 myocardial infarction,52,64,68) tachycardia-induced dilated cardiomyopathies,69 idiopathic cardiomyopathies 61,62 and types of long-QT syndrome70 (see more comprehensive reviews).71,72 Commonly-described t-tubule abnormalities in skeletal muscle include widening of triads73,74 and micron-scale dilatation (vacuolation).75,76 Such abnormalities have been observed in connection to pathologies such as human myotubular myopathies73, myotonic muscular dystrophy,77 rippling muscle disease78 and a range of genetic myopathies (see review79). Vacuolation is often seen in non-pathological conditions as fatigue 75 or in muscle damage due to eccentric contractions.80 Several recent studies have focused on the molecular mechanisms of t-tubule alterations; commonly implicated proteins include junctophilins (JPH), bin-1and teletholin. Such proteins either display altered expression or cleavage in correlation with the pathology. In the case of junctophilin, overexpression provided some resistance against t-tubule changes and knock-down led to alterations similar to those seen in failure.65,66,81-83 While the altered role(s) of such proteins is becoming clearer, questions relating to cause and effect are less well resolved.

A case for improving imaging methods

Study of the molecular machineries listed above and their dysfunction in muscle pathologies have indicated a tight relationship between the cellular scale topology of the t-system (as characterised, e.g. by the t-power66 and other tubule orientation indices, e.g. as provided by AutoTT,84 and other approaches61,62) and the nanoscale features of the t-system and associated structures (e.g. junctions). For example, overexpression of JPH could counter t-tubule alterations in failing myocytes but altered the nanoscale structure of dyads.65 Mechanistically this relationship between the micron-scale and nanometre-scale features of t-tubules is still poorly understood. This has probably been aggravated by the fact that widely used confocal fluorescence methods are excellent at detecting micron scale alterations but nanoscale differences generally require higher resolution. Table 1 of the review by Guo et al.71 provides a good summary of the wide use of diffraction-limited microscopy modalities to characterise the t-system alterations that occur in heart failure. We argue that a more complete understanding of the changed ultrastructure is only possible with an imaging approach that appropriately resolves also smaller scale changes. While this can be remedied to some extent by using EM techniques an approach that includes both scales (micron-scale and nano-scale) would be beneficial. Optical super-resolution methods and whole-cell tomographic EM techniques have already demonstrated their utility in fulfilling this need for a multi-scale analysis of t-tubule structure in such studies. One such example is a recent Stimulated Emission-Depletion (STED) microscopy study that demonstrated dilation of t-tubules in addition to the aforementioned re-arrangement in failing mouse ventricular myocytes.52 While dilated t-tubules had been visualised in larger species with naturally larger t-tubules (e.g. human, canine62, 85, 86), this was one of the first clear demonstrations of nanometre-scale “remodelling” of t-tubules in a small (murine) species and could be performed in intact myocytes. Whether it is approached with a single microscopy technique or a combination of microscopies, we propose that future studies examining t-tubule changes should generally address both these spatial scales.

With the benefits outlined in Table 1, SMLM is a modality that can be used for imaging the same fluorescent samples for observing the t-tubule nano-architecture and the distributions of accessory proteins that are implicated in the cardiac and skeletal muscle pathologies. Less demanding hardware35 in contrast to STED (e.g.52), compatibility with generic fluorescence labelling protocols (e.g. standard immunofluorescence35) and freely available image analysis and reconstruction software (e.g. rapidSTORM26) are key features of this technology that encourage muscle biologists to examine these samples with SMLM. It must be emphasised however that SMLM is not a replacement to other microscopy techniques such as EM or tomographic EM. Correlative or supplemented imaging SMLM samples with EM, whenever possible, promises additional information such as 3D nano-structure and relationship with other organelles as well as a means of validating the nano-scale measurements, e.g.50 We also underscore the potential utility of SMLM and other optical super-resolution modes in supplementing (diffraction-limited) confocal fluorescence microscopy of calcium micro- and nano-domains (e.g. imaging Ca2+ sparks with intra-dyadic Ca2+ sensors87) to correlate functional measurements with the local ultrastructure.

Conclusion

SMLM is emerging as a fluorescence microscopy technique capable of resolving nanometre-scale features of cardiac and skeletal muscle t-tubules that were previously restricted to EM. In a short period of application of this technique (<5 years) many new observations have been made to advance our understanding of the membrane and protein organisation of t-tubules. Sample preparation (ensuring high labelling densities, thin samples and low background fluorescence) and accurate localisation of single fluorophore locations are pivotal for obtaining high quality super-resolution images from SMLM data. However, its compatibility with hydrated samples is ideal for examining the nanometre- to micron-scale alterations in the t-tubule structure in a range of pathologies. The potentially quantitative nature of the data also means that image-based measurements of tubule structure and protein densities are likely to be particularly useful for computational simulations of t-tubule related structure-function relationships.

References

- 1.Franzini-Armstrong C, Protasi F. Ryanodine receptors of striated muscles: a complex channel capable of multiple interactions. Physiol Rev 1997;77:699-729. Epub 1997/07/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asghari P, Scriven DR, Sanatani S, et al. Nonuniform and variable arrangements of ryanodine receptors within mammalian ventricular couplons. Circ Res 2014;115:252-62. Epub 2014/05/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jayasinghe ID, Munro M, Baddeley D, Launikonis BS, Soeller C. Observation of the molecular organization of calcium release sites in fast- and slow-twitch skeletal muscle with nanoscale imaging. J R Soc Interface 2014;11(99). Epub 2014/08/08s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huxley AF. Local activation of striated muscle from the frog and the crab. J Physiol 1957;135:17-8P. Epub 1957/01/23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Escobar M, Cardenas C, Colavita K, Petrenko NB, Franzini-Armstrong C. Structural evidence for perinuclear calcium microdomains in cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2011;50:451-9. Epub 2010/12/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Launikonis BS, Murphy RM, Edwards JN. Toward the roles of store-operated Ca2+ entry in skeletal muscle. Pflugers Archiv 2010;460:813-23. Epub 2010/06/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyfenko AD, Dirksen RT. Differential dependence of store-operated and excitation-coupled Ca2+ entry in skeletal muscle on STIM1 and Orai1. J Physiol 2008;586:4815-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu X, Zhang T, Bossuyt J, et al. Local InsP3-dependent perinuclear Ca2+ signaling in cardiac myocyte excitation-transcription coupling. J Clin Invest 2006;116:675-82. Epub 2006/03/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lynch GS, Ryall JG. Role of beta-adrenoceptor signaling in skeletal muscle: implications for muscle wasting and disease. Physiol Rev 2008;88:729-67. Epub 2008/04/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fraser JA, Huang CL-H, Pedersen TH. Relationships between resting conductances, excitability, and t-system ionic homeostasis in skeletal muscle. J Gen Physiol 2011;138:95-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kekenes-Huskey PM, Cheng Y, et al. Modeling effects of L-type Ca2+ current and Na+-Ca2+ exchanger on Ca2+ trigger flux in rabbit myocytes with realistic t-tubule geometries. Front Physiol 2012;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu Z, Holst MJ, Cheng Y, McCammon JA. Feature-preserving adaptive mesh generation for molecular shape modeling and simulation. J Mol Graph Model 2008;26:1370-80. Epub 2008/03/14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng Y, Yu Z, Hoshijima M, Holst MJ, McCulloch AD, McCammon JA, et al. Numerical Analysis of Ca2+ Signaling in Rat Ventricular Myocytes with Realistic Transverse-Axial Tubular Geometry and Inhibited Sarcoplasmic Reticulum. PLoS Comput Biol 2010;6(10):e1000972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franzini-Armstrong C. Veratti and beyond: Structural contributions to the study of muscle activation. Rend Fis Acc Lincei. 2002;13:289-323. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbe E. Beiträge zur Theorie des Mikroskops und der mikroskopischen Wahrnehmung. Archiv f mikrosk Anatomie. 1873;9:413-8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rayleigh L. On the Theory of Optical Images, with special reference to the Microscope. Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society. 1903;23:474-82. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein T, Proppert S, Sauer M. Eight years of single-molecule localization microscopy. Histochem Cell Biol 2014;141:561-75. Epub 2014/02/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van de Linde S, Heilemann M, Sauer M. Live-cell super-resolution imaging with synthetic fluorophores. Ann Rev Phys Chem 2012;63:519-40. Epub 2012/03/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heilemann M, van de Linde S, Schüttpelz M, et al. Subdiffraction-Resolution Fluorescence Imaging with Conventional Fluorescent Probes. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2008;47:6172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Betzig E, Patterson GH, Sougrat R, et al. Imaging Intracellular Fluorescent Proteins at Nanometer Resolution. Science 2006;313:1642-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baddeley D, Cannell MB, Soeller C. Visualization of localization microscopy data. Microsc Microanal 2010;16:64-72. Epub 2010/01/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baddeley D, Crossman D, Rossberger S, et al. 4D super-resolution microscopy with conventional fluorophores and single wavelength excitation in optically thick cells and tissues. PloS one. 2011;6:e20645 Epub 2011/06/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bossi M, Folling J, Belov VN, et al. Multicolor far-field fluorescence nanoscopy through isolated detection of distinct molecular species. Nano letters. 2008;8:2463-8. Epub 2008/07/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tokunaga M, Imamoto N, Sakata-Sogawa K. Highly inclined thin illumination enables clear single-molecule imaging in cells. Nat Methods 2008;5:159-61. Epub 2008/01/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang F, Hartwich TMP, Rivera-Molina FE, et al. Video-rate nanoscopy using sCMOS camera-specific single-molecule localization algorithms. Nat Methods 2013;10:653-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolter S, Loschberger A, Holm T, et al. rapidSTORM: accurate, fast open-source software for localization microscopy. Nat Methods 2012;9:1040-1. Epub 2012/11/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hess ST, Girirajan TP, Mason MD. Ultra-high resolution imaging by fluorescence photoactivation localization microscopy. Biophys J 2006;91:4258-72. Epub 2006/09/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rust MJ, Bates M, Zhuang X. Sub-diffraction-limit imaging by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM). Nat Methods. 2006;3:793-5. Epub 2006/08/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Annibale P, Vanni S, Scarselli M, Rothlisberger U, Radenovic A. Quantitative photo activated localization microscopy: unraveling the effects of photoblinking. PloS one 2011;6:e22678 Epub 2011/08/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jayasinghe ID, Baddeley D, Kong CH, et al. Nanoscale organization of junctophilin-2 and ryanodine receptors within peripheral couplings of rat ventricular cardiomyocytes. Biophys J 2012;102:L19-21. Epub 2012/03/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shim S-H, Xia C, Zhong G, et al. Super-resolution fluorescence imaging of organelles in live cells with photoswitchable membrane probes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:13978-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baddeley D, Cannell M, Soeller C. Three-dimensional sub-100 nm super-resolution imaging of biological samples using a phase ramp in the objective pupil. Nano Res. 2011;4:589-98. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang B, Jones SA, Brandenburg B, Zhuang X. Whole-cell 3D STORM reveals interactions between cellular structures with nanometer-scale resolution. Nat Methods 2008;5:1047-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mortensen KI, Churchman LS, Spudich JA, Flyvbjerg H. Optimized localization analysis for single-molecule tracking and super-resolution microscopy. Nat Methods 2010;7:377-81. Epub 2010/04/07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baddeley D, Jayasinghe ID, Cremer C, Cannell MB, Soeller C. Light-induced dark states of organic fluochromes enable 30 nm resolution imaging in standard media. Biophys J 2009;96:L22-4. Epub 2009/01/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baddeley D, Jayasinghe ID, Lam L, et al. Optical single-channel resolution imaging of the ryanodine receptor distribution in rat cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:22275-80. Epub 2009/12/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jayasinghe ID, Lo HP, Morgan GP, Parton RG, Soeller C, Launikonis BS. Examination of the sub-sarcolemmal tubular system of mammalian skeletal muscle fibers. Biophys J. 2013, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hou Y, Crossman DJ, Rajagopal V, et al. Super-resolution fluorescence imaging to study cardiac biophysics: alpha-actinin distribution and Z-disk topologies in optically thick cardiac tissue slices. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2014. Epub 2014/07/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soeller C, Cannell MB. Examination of the transverse tubular system in living cardiac rat myocytes by 2-photon microscopy and digital image-processing techniques. Circ Res 1999;84:266-75. Epub 1999/02/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Endo M. Entry of fluorescent dyes into the sarcotubular system of the frog muscle. J Physiol 1966;185:224-38. Epub 1966/07/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Savio-Galimberti E, Frank J, Inoue M, et al. Novel features of the rabbit transverse tubular system revealed by quantitative analysis of three-dimensional reconstructions from confocal images. Biophys J 2008;95:2053-62. Epub 2008/05/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen-Izu Y, McCulle SL, Ward CW, et al. Three-dimensional distribution of ryanodine receptor clusters in cardiac myocytes. Biophys J 2006;91:1-13. Epub 2006/04/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jayasinghe ID, Cannell MB, Soeller C. Organization of ryanodine receptors, transverse tubules, and sodium-calcium exchanger in rat myocytes. Biophys J 2009;97:2664-73. Epub 2009/11/18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jayasinghe I, Crossman D, Soeller C, Cannell M. Comparison of the organization of T-tubules, sarcoplasmic reticulum and ryanodine receptors in rat and human ventricular myocardium. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2012;39:469-76. Epub 2011/07/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richards MA, Clarke JD, Saravanan P, et al. Transverse tubules are a common feature in large mammalian atrial myocytes including human Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2011. 2011-11-01 00:00:00. H1996-H2005 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00284.2011. Epub 2011 Aug 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hayashi T, Martone ME, Yu Z, et al. Three-dimensional electron microscopy reveals new details of membrane systems for Ca2+ signaling in the heart. J Cell Sci 2009;122(Pt 7):1005-13. Epub 2009/03/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Das T, Hoshijima M. Adding a new dimension to cardiac nano-architecture using electron microscopy: coupling membrane excitation to calcium signaling. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2013;58:5-12. Epub 2012/12/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Asghari P, Schulson M, Scriven DR, Martens G, Moore ED. Axial tubules of rat ventricular myocytes form multiple junctions with the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Biophys J 2009;96:4651-60. Epub 2009/06/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pinali C, Bennett H, Davenport JB, Trafford AW, Kitmitto A. Three-dimensional reconstruction of cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum reveals a continuous network linking transverse-tubules: this organization is perturbed in heart failure. Circ Res 2013;113:1219-30. Epub 2013/09/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wong J, Baddeley D, Bushong EA, et al. Nanoscale distribution of ryanodine receptors and caveolin-3 in mouse ventricular myocytes: dilation of t-tubules near junctions. Biophys J 2013;104:L22-4. Epub 2013/06/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hong T. Cardiac BIN1 folds T-tubule membrane, controlling ion flux and limiting arrhythmia. Nature Med 2014;20:624-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wagner E, Lauterbach MA, Kohl T, et al. Stimulated emission depletion live-cell super-resolution imaging shows proliferative remodeling of T-tubule membrane structures after myocardial infarction. Circ Res 2012;111:402-14. Epub 2012/06/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Franzini-Armstrong C, Peachey LD. A modified Golgi black reaction method for light and electron microscopy. J Histochem Cytochem 1982;30:99-105. Epub 1982/02/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jayasinghe I. D., Launikonis B. S. Three-dimensional reconstruction and analysis of the tubular system of vertebrate skeletal muscle. J Cell Sci 2013;126:4048-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peachey LD. The sarcoplasmic reticulum and transverse tubules of the frog’s sartorius. J Cell Biol 1965;25:Suppl:209-31. Epub 1965/06/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murphy RM, Mollica JP, Lamb GD. Plasma membrane removal in rat skeletal muscle fibers reveals caveolin-3 hot-spots at the necks of transverse tubules. Exp Cell Res 2009;315:1015-28. Epub 2008/12/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Edwards JN, Cully TR, Shannon TR, Stephenson DG, Launikonis BS. Longitudinal and transversal propagation of excitation along the tubular system of rat fast-twitch muscle fibres studied by high speed confocal microscopy. J Physiol 2012;590(Pt 3):475-92. Epub 2011/12/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dahl R, Larsen S, Dohlmann TL, et al. Three-dimensional reconstruction of the human skeletal muscle mitochondrial network as a tool to assess mitochondrial content and structural organization. Acta physiologica; (Oxford, England: ). 2014. Epub 2014/04/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sun M, Huang J, Bunyak F, et al. Superresolution microscope image reconstruction by spatiotemporal object decomposition and association: application in resolving t-tubule structure in skeletal muscle. Optics express. 2014;22:12160-76. Epub 2014/06/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Louch WE, Bito V, Heinzel FR, et al. Reduced synchrony of Ca2+ release with loss of T-tubules-a comparison to Ca2+ release in human failing cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res 2004;62:63-73. Epub 2004/03/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Crossman DJ, Ruygrok PN, Soeller C, Cannell MB. Changes in the organization of excitation-contraction coupling structures in failing human heart. PloS one. 2011;6:e17901 Epub 2011/03/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cannell MB, Crossman DJ, Soeller C. Effect of changes in action potential spike configuration, junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum micro-architecture and altered t-tubule structure in human heart failure. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 2006;27:297-306. Epub 2006/08/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Song LS, Sobie EA, McCulle S, Lederer WJ, Balke CW, Cheng H. Orphaned ryanodine receptors in the failing heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:4305-10. Epub 2006/03/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Louch WE, Mork HK, Sexton J, et al. T-tubule disorganization and reduced synchrony of Ca2+ release in murine cardiomyocytes following myocardial infarction. J Physiol 2006;574(Pt 2):519-33. Epub 2006/05/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guo A, Zhang X, Iyer VR, et al. Overexpression of junctophilin-2 does not enhance baseline function but attenuates heart failure development after cardiac stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:12240-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wei S, Guo A, Chen B, et al. T-tubule remodeling during transition from hypertrophy to heart failure. Circ Res 2010;107:520-31. Epub 2010/06/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tao W, Shi J, GW2nd Dorn, Wei L, Rubart M. Spatial variability in T-tubule and electrical remodeling of left ventricular epicardium in mouse hearts with transgenic Galphaq overexpression-induced pathological hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2012;53:409-19. Epub 2012/06/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Heinzel FR, Bito V, Biesmans L, et al. Remodeling of T-tubules and reduced synchrony of Ca2+ release in myocytes from chronically ischemic myocardium. Circ Res 2008;102:338-46. Epub 2007/12/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Balijepalli RC, Lokuta AJ, Maertz NA, et al. Depletion of T-tubules and specific subcellular changes in sarcolemmal proteins in tachycardia-induced heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 2003;59:67-77. Epub 2003/06/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mohler PJ, Schott JJ, Gramolini AO, et al. Ankyrin-B mutation causes type 4 long-QT cardiac arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death. Nature 2003;421:634-9. Epub 2003/02/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guo A, Zhang C, Wei S, Chen B, Song LS. Emerging mechanisms of T-tubule remodelling in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 2013;98:204-15. Epub 2013/02/09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ibrahim M, Gorelik J, Yacoub MH, Terracciano CM. The structure and function of cardiac t-tubules in health and disease. Proc Biol Sci 2011;278:2714-23. Epub 2011/06/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dowling JJ, Vreede AP, Low SE, et al. Loss of myotubularin function results in T-tubule disorganization in zebrafish and human myotubular myopathy. PLoS Genet 2009;5:e1000372 Epub 2009/02/07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lamb GD, Junankar PR, Stephenson DG. Raised intracellular [Ca2+] abolishes excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle fibres of rat and toad. J Physiol 1995;489 (Pt 2):349-62. Epub 1995/12/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lannergren J, Bruton JD, Westerblad H. Vacuole formation in fatigued single muscle fibres from frog and mouse. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 1999;20:19-32. Epub 1999/06/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Krolenko SA, Lucy JA. Reversible vacuolation of T-tubules in skeletal muscle: mechanisms and implications for cell biology. Int Rev Cytol 2001;202:243-98. Epub 2000/11/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fugier C, Klein AF, Hammer C, et al. Misregulated alternative splicing of BIN1 is associated with T tubule alterations and muscle weakness in myotonic dystrophy. Nat Med 2011;17:720-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lamb GD. Rippling muscle disease may be caused by “silent” action potentials in the tubular system of skeletal muscle fibers. Muscle Nerve. 2005;31:652-8. Epub 2005/03/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Al-Qusairi L, Laporte J. T-tubule biogenesis and triad formation in skeletal muscle and implication in human diseases. Skeletal muscle 2011;1:26 Epub 2011/07/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yeung EW, Balnave CD, Ballard HJ, Bourreau JP, Allen DG. Development of T-tubular vacuoles in eccentrically damaged mouse muscle fibres. J Physiol 2002;540(Pt 2):581-92. Epub 2002/04/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ibrahim M, Siedlecka U, Buyandelger B, et al. A critical role for Telethonin in regulating t-tubule structure and function in the mammalian heart. Hum Mol Genet 2013;22:372-83. Epub 2012/10/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Murphy RM, Dutka TL, Horvath D, Bell JR, Delbridge LM, Lamb GD. Ca2+-dependent proteolysis of junctophilin-1 and junctophilin-2 in skeletal and cardiac muscle. J Physiol 2013;591(Pt 3):719-29. Epub 2012/11/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.van Oort RJ, Garbino A, Wang W, et al. Disrupted junctional membrane complexes and hyperactive ryanodine receptors after acute junctophilin knockdown in mice. Circulation 2011;123:979-88. Epub 2011/02/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Guo A, Song LS. AutoTT: automated detection and analysis of T-tubule architecture in cardiomyocytes. Biophys J 2014;106:2729-36. Epub 2014/06/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kostin S, Scholz D, Shimada T, et al. The internal and external protein scaffold of the T-tubular system in cardiomyocytes. Cell tissue res 1998;294:449-60. Epub 1998/11/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sachse FB, Torres NS, Savio-Galimberti E, et al. Subcellular structures and function of myocytes impaired during heart failure are restored by cardiac resynchronization therapy. Circulation research. 2012;110:588-97. Epub 2012/01/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shang W, Lu F, Sun T, et al. Imaging Ca2+ nanosparks in heart with a new targeted biosensor. Circulation research 2014;114:412-20. Epub 2013/11/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]