Abstract

Although several strategies to three-dimensionally print cardiovascular grafts exist, these technologies either have required extensive culturing of cells on scaffolds prior to implantation to impart mechanical stability, necessitate additional fabricated components after 3D printing, or have not been proven in vivo. Here, we demonstrate a material and methodology utilizing digital stereolithography for the fabrication of non-cellular biodegradable polymeric vascular grafts. Using this approach, we show, for the first time, the functionality of a 3D printed vascular graft in vivo as an inferior vena cava conduit interposition graft. Our 3D printing materials and methodology should provide a platform for future efforts to fabricate wholly 3D printed, custom-tailored cardiovascular grafts. Such a platform will also enable the precise control over both macroscale—like curvature and bifurcations—and microscale features—like porosity and surface roughness—to improve the performance and integration of these patient-specific vascular scaffolds.

Keywords: 3D printing, vascular grafts, biomaterials, biodegradable polyesters, poly(propylene fumarate)

The most common form of birth defect worldwide is congenital heart disease (CHD).[1] Treating CHD presents unique complications. For example, specific defects may present uniquely in different patients due to anatomical differences. Proper design and adaptation of implanted grafts to correct these defects is crucial because graft orientation and shape is integral to successful CHD surgical outcomes.[2,3] In addition, current grafts used in these procedures suffer from progressive obstruction, infection, increased risk of thromboembolitic complications, a lack of growth potential, poor long-term durability, and calcification.[4–8] Graft failure is expected in 70–100% of cases in 10–15 years.

To over the challenges of growth potential, host-tissue integration, and anatomical differences, 3D printing patient-specific grafts offers tremendous opportunity in tissue engineering. Yet there are many limitations to overcome. Current bioprinting efforts have enabled the fabrication of biologically functional blood vessels.[9,10] But these vessels are more suited for vascularization of larger tissues due to material and size constraints, along with insufficient mechanical properties for larger-scale vessels unless they've been extensively cultured to allow for tissue maturation. Previous studies have also examined the use of fabricating grafts utilizing solvent-cast molding processes, but 3D printing the graft directly can reduce the steps necessary to construct a scaffold.[11,12] An earlier study documented the development of a printable polyurethane that may be suitable for vascular materials and another described the printing of combined 3D printing and electrospinning technique,[13,14] but none to our knowledge have demonstrated in vivo functionality of a fully 3D printed non-cellular vascular graft. Our study presents the development and application of a platform for the fully 3D printed fabrication of non-cellular biodegradable scaffolds for vascular tissue engineering demonstrated in vivo. Such a platform may eventually enable the production of more complex structures customized for experimental studies or clinical applications by incorporating customized macroscale geometry—like vessel bifurcations and curves—with controlled microscale architecture—like porosity and surface roughness.

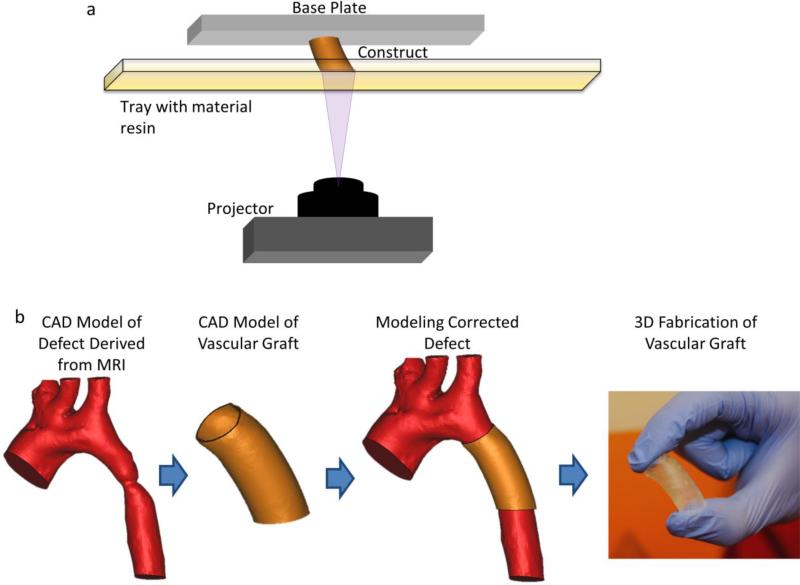

We examine techniques and materials developed for the 3D printing of vascular tissue engineering scaffolds utilizing poly(propylene fumarate) (PPF) and demonstrate its efficacy in the mouse venous system. For this study, we focused on a venous graft model because there are no ideal commercially available synthetic biomaterials for the repair or reconstruction of vessels in venous circulation. PPF is a biocompatible and biodegradable polyester that contains a carbon-carbon double bond along its backbone.[15] This enables crosslinking between polymer chains. Such crosslinking can be initiated via photoinitiators. Due to this photocrosslinkability and its biocompatibility, PPF is a prime candidate for 3D fabrication techniques such as digital light stereolithography (DLP) (as depicted in Figure 1a) to construct functional, tissue-engineering scaffolds. The overall process is demonstrated in Figure 1b. As we are focused on CHD, this represents a relatively simple case of coarctation of the aorta. Images of the aorta are first obtained via MRI or CT and segmented for analysis. A custom graft is designed to fit the specific curvature of this patient's anatomy and subsequently can be tested both for fit and fluid dynamics before eventual 3D fabrication of the customized implant.

Figure 1.

(a) Digital light processing (DLP) stereolithography. The fabrication method involves DLP printing. In short, the PPF-based material resin is a viscous liquid at room temperature within the material resin tray. A single layer of the construct is cured at once, before the construct (attached to the base plate), is moved vertically to allow for curing of the next layer. (b) Design and fabrication process of 3D printed graft to treat a coarctation of the aorta. Images obtained via medical imaging technologies such as MRI or CT are segmented and used to create a 3D computer model. A customized vascular graft can then be created via CAD software, and subsequently assessed with the segmented model of the defect. Once the graft design has been finalized, it can be 3D printed.

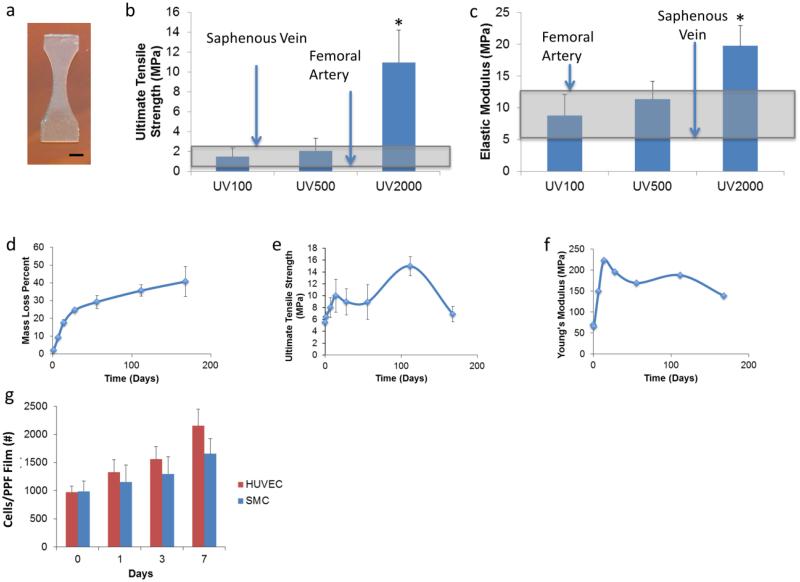

To ensure the viability of PPF grafts for vascular applications, we first performed mechanical testing on 3D printed dogbones (Figure 2a). Most current methodologies of printing do not directly produce devices with adequate mechanical strength.[16,17] Bioprinting strategies necessitate cell seeding and culturing to develop tissue-based grafts with adequate strength to be viable once implanted. Still, few non-cellular vascular graft printing strategies have been pursued that demonstrate the mechanical properties shown immediately after fabrication by the PPF-based grafts. Mechanical properties of the 3D printed structure relied largely on the amount of post-printing exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation via an Otoflash lamp, which increased polymer crosslinking. Each flash of the Otoflash emits ~11 W. Thus, 100 flashes yields ~1100 W (UV100), 500 flashes yields ~5500 W (UV500), and 2000 flashes yields ~22,000 W (UV2000) of power over the spectrum of UV light radiated by the lamp. Results of tensile testing can be observed in Figure 2b–c. With 100 flashes of the UV lamp, 3D printed PPF samples demonstrated an ultimate tensile strength (UTS) of 1.48 ± 0.88 MPa and an elastic modulus of 8.79 ± 3.28 MPa; 500 flashes yielded samples with an UTS of 2.06 ± 1.28 MPa and an elastic modulus of 11.32 ± 2.82 MPa; and 2000 flashes yielded an UTS of 2.06 ± 1.28 MPa and an elastic modulus of 11.32 ± 2.82 MPa. The printed grafts demonstrated initial mechanical properties comparable to native vessels using in grafting procedures and appropriate for use as venous scaffolds.[18–22] There were no significant differences between UV100 and UV500 grafts, although UV2000 grafts demonstrated mechanical properties beyond those demonstrated for cardiovascular tissues.

Figure 2.

Mechanical characterization of 3D printed PPF material. (a) shows the dogbone shape 3D printed for mechanical studies; scale bar, 2.0 mm. (b,c) mechanical properties of 3D printed grafts exposed to UV light post-printing via the Otoflash curing device. These properties are compared with the saphenous vein and femoral artery. The shaded gray box highlights the range of mechanical properties found in such autologous tissue implants. (d–f) In vitro degradation of 3D printed Grafts over 6 months. (d) Mass loss over time. (d) and (f) represent the change in ultimate tensile strength and Young's modulus, respectively. (g) shows the growth of HUVEC and SMC populations on 3D printed substrates in cell culture. *represents statistical significance between groups (p < 0.05).

Since PPF is biodegradable, it is crucial to assess the effects of degradation on graft mechanical properties to predict long-term mechanical support once implanted. After 6 months of in vitro degradation (Figure 2d–f), printed grafts experienced a 40.76 ± 8.37 % decrease in mass. The UTS, Figure 2e, of these printed materials increased over time, peaking at 4 months of degradation after which it returned to values comparable to the initial UTS. The elastic modulus of the grafts appeared to increase initially before slowly decreasing as shown in Figure 2f.

These properties were generally maintained throughout the duration of our 6 month degradation study, despite the mass loss of the scaffold. We hypothesize that the increase in strength during degradation, evidenced by the changes in elastic modulus and UTS, may have been caused by a combination of two phenomena. First, during the printing process, the PPF chains are not fully crosslinked. This may result in the ongoing, long-term crosslinking of polymer chains well after the scaffolds were initially printed. In addition, we believe that as smaller chains degrade, there may be reduced steric hindrance between the larger chains. This enables increased crosslinking and entanglement between these chains, which may increase the elastic modulus and UTS of the scaffolds.

Before implantation of the grafts, we also assessed the viability of relevant vascular cell types. Human umbilical vein cells (HUVECs) and human umbilical vein smooth muscle cells (HUSMCs) were seeded on 3D printed PPF surfaces to assess initial attachment. 19.5 ± 2.1 % of seeded HUVECs and 19.8 ± 3.7 % of seeded HUSMCs successfully attached. As shown in Figure 2g, over 7 days HUVECs experienced a 1.91 ± 0.66 fold increase in total population, and HUSMCs demonstrated a 1.29 ± 0.70 fold increase in total population. This established cell viability on the 3D printed surfaces.

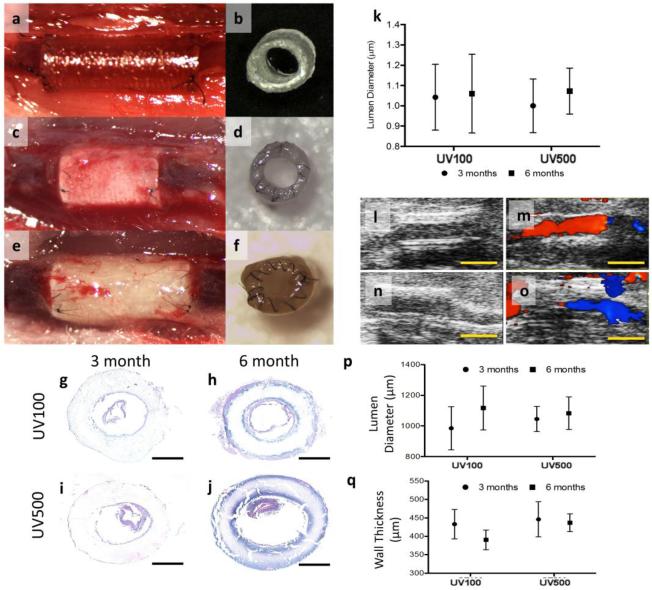

Once implanted in mice, non-cellular 3D printed PPF scaffolds demonstrated their functionality as venous interposition grafts (Figure 3a–f). We were particularly interested in studying whether the UV100 or UV500 grafts performed any differently in vivo due to slight differences in mechanical properties. No significant differences existed between the two graft groups (n=6). All grafts demonstrated no thrombosis, graft aneurysm, or stenosis at any time over the 6 months implantation experiment. Additionally, grafts remained patent throughout the experiment. Histological morphometry of paraffin embedded sections demonstrated no significant difference in graft thickness between time points, suggesting minimal to no restenosis. Confirming this, lumen diameters (Figure 3k) obtained from ultrasound images over the 6 month time course are shown in Figure 3l–o. Color Doppler ultrasound confirmed graft patency in all animals of both groups. Lumen diameters measured from B-mode images suggest that the inner diameter of both graft types increased over the course of implantation, possibly due to graft degradation.

Figure 3.

Evolution of 3D printed graft over 6 months in vivo. (a, b) 3D printed graft at the time of implantation, (c, d) 3 months after implantation and (e, f) 6 months after implantation. No thrombosis or stenosis was observed upon gross examination at the time of explantation in either graft type. (k) Lumen diameters obtained from ultrasound images over the 6 month time course. (l) Representative B-Mode image of UV100 at 6 months. (m) Representative color Doppler of UV100 at 6 months. (n) Representative B-Mode image of UV500 at 6 months. (o) Representative color Doppler of UV500 at 6 months. Color Doppler ultrasound confirmed graft patency in all animals of both groups; Scales bars, 2.0 mm. (g–j) Histomorphometry cross-section of implanted graft. H&E staining of UV100 (g, h) and UV500 (i, j) at 3 months (g, i) and 6 months (h, j) after implantation. Of note, detachment of intimal layer was an artificial effect that created during the slicing of tissue. Although no cellular infiltration was observed at either time point, graft degradation is evident at 6 months and UV500 appears saturated with eosinophilic serum proteins; scale bars, 500 μm. Quantification of (p) lumen diameter and (q) wall thickness over the time course of observation.

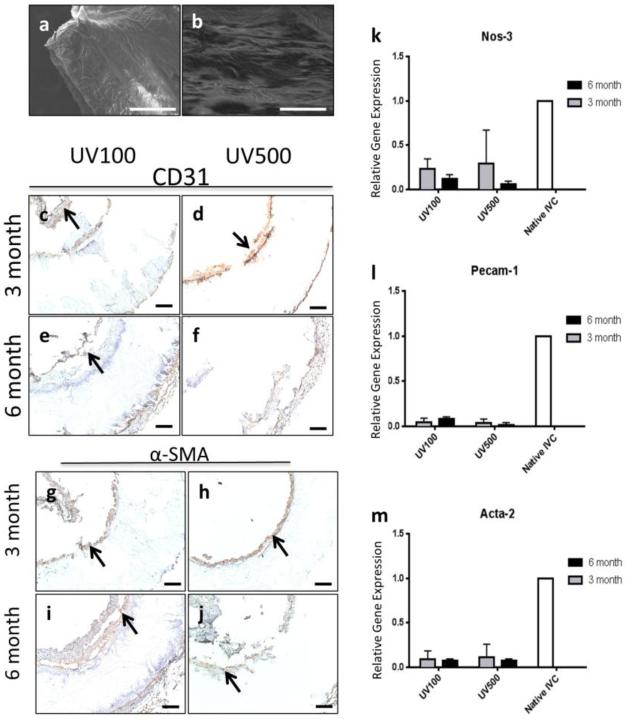

H&E staining of explanted graft sections are shown in Figure 3g–j. Of note, detachment of the intimal layer was an artificial effect created during tissue slicing. Neotissue formation was mainly found along the inner lumen and exterior of the graft, while lumen diameter and wall thickness were maintained throughout the experiment (Figure 3p–q). Most importantly, endothelialization of the grafts was observed. SEM imaging illustrated an intact endothelial monolayer in both groups (Figure 4a–b), confirming a confluent attached endothelial monolayer. Endothelial cells (CD-31 staining) and SMC (α-SMA staining) proliferation could be observed along graft surfaces as seen in Figure 4a–j. This was observed even without the aid of cell-seeding or the addition of biofunctional molecules to promote cell attachment and growth. Still, minimal cellular infiltration within the graft was observed at any time point. To improve this in future work, porous features may be incorporated into the 3D printed structure that could induce cell infiltration before and during bulk degradation. In assessing tissue functionality, NOS-3 and PECAM-1 gene expression (Figure 4k–l) was lower in the 3D printed graft tissues compared to native IVCs. While less endothelial functionality was present in grafts when compared to native IVC according to qt-PCR results, positive expression of eNOS in both groups suggests active vascular tissue repair and remodeling processes. This may also be one reason for the low incidence of thrombosis observed in the present study. To identify SMCs, α-SMA staining of explanted grafts sections was observed and can be seen in Figure 4g–j. SMC layers can be observed in both groups. RT-qPCR for Acta-2 indicated that Acta-2 expression and SMC proliferation occurred within neotissues formed on grafts although they were markedly lower than that of native IVC over the 6 month time course (Figure 4m).

Figure 4.

Endothelialization of 3d printed graft. SEM imaging of (a) UV100 and (b) UV500 illustrates an intact endothelial monolayer in both groups confirmed a confluent attached endothelial monolayer. Scale bars are 500 μm. CD-31 staining of (c, e) UV100 and (d, f) UV500 (c, d) graft walls to identify endothelial cells at the (c, d) 3 month and (e, f) 6 month time points demonstrated a endothelial monolayer although there is the detachment of the endothelial cell layer during the histological preparation process. CD-31 stained cells indicated by arrows. RT-qPCR for (k) eNOS and (i) Pecam-1 expressin in tissues adhered to grafts compared to native IVC. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation in 3d printed graft. α-SMA staining of (g, i) UV100 and (h, j) UV500 sections to identify smooth muscle cells at the (g, h) 3 month and (i, j) 6 month time points. α-SMA stained cells indicated by arrows. Scale bars, 100 μm. RT-qPCR for (m) Acta-2 indicated that Acta-2 expression and smooth muscle cell proliferation although they were markedly lower than that of native IVC in both graft types over the 6 month time course.

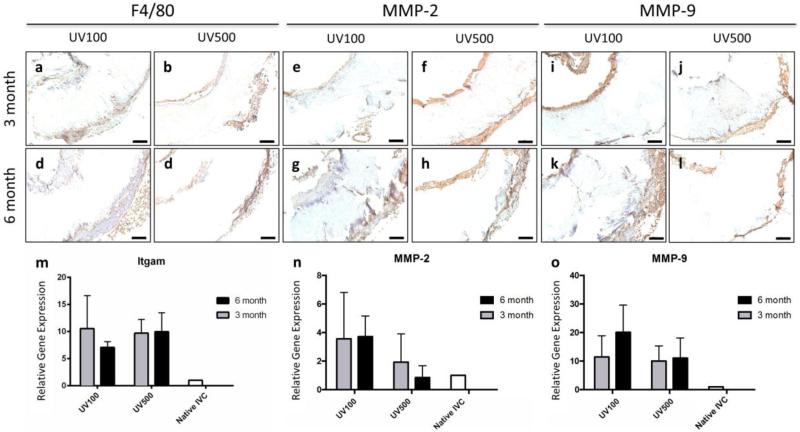

Vascular remodeling processes underway in the 3D printed grafts was also demonstrated with the secretion of matrix metalloproteases (MMP) and macrophage attachment, a crucial step in graft and tissue formation.[23] To identify macrophages and secreted matrix MMP activity, stains were performed for F4/80, MMP-2, and MMP-9 as seen in Figure 5a–l. Corresponding RT-qPCR for confirmed gene expression of Itgam, MMP-2, and MMP-9. Extended inflammation, as evidenced by F4/80 positive cells and relatively high expression of Itgam in both groups over the course of 6 months (Figure 5m–o), suggests that implanted scaffolds from both groups elicited a continued foreign body response. Concomitant with macrophage attachment to scaffolds was significant secretion of matrix MMP, highlighting the degree of extended inflammation and tissue remodeling processes underway. Extended inflammation suggests that implanted scaffolds elicited a continued foreign body response. Such a persistent response may result in tissue calcification.[24–26] This may be avoided through improvement and modulation of the degradation rate of the current PPF vascular graft printing materials and the graft design by altering the molecular weight of the PPF polymer, introducing more surface features to increase surface area, decreasing amount of crosslinking, etc.

Figure 5.

Inflammation and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling in 3d printed graft. (a–d) F4/80, (e–h) MMP-2, and (k–n) MMP-9 staining of (a, c, f, h, k, m) UV100 and (b, d, g, I, l, n) UV500 sections to identify macrophages and secreted matrix MMP activity at the (a, b, f, g, k, l) 3 month and (c, d, h, i, m, n) 6 month time points; scale bars, 100 μm. RT-qPCR for (e) Itgam, (j) MMP-2, and (o) MMP-9 confirm positive staining observed in tissue samples.

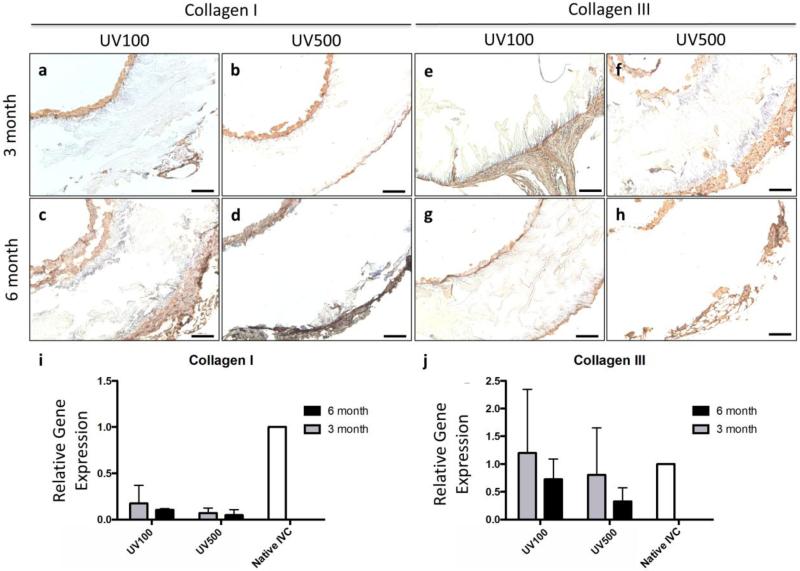

Additional evidence of tissue formation was demonstrated by collagen deposition and ECM remodeling. Immunostaining to identify collagen deposition remodeling at the 3 month and 6 month time points illustrates that vascular neotissue in both groups was collagen-rich and active ECM turnover occurred in these constructs over 6 months as seen in Figure 6a–h. While Collagen I expression appeared reduced compared to native IVC (Figure 6i), gene expression of Collagen III appeared similar to that of native IVC at 3 months (Figure 6j). Early (3 month) expression of Collagen III is a common observation in graft implants and suggests active ECM deposition, tissue remodeling, and immature neotissue. However, the lack of Collagen I expression at later time points could be attributed to either the extended inflammation and high MMP activity (Figure 5n–o) or a reduced influence of mechanobiological and biomechanical stimuli on infiltrating cells and deposited ECM due to the slow degradation rate of the 3D printed polymer scaffold.

Figure 6.

ECM deposition in 3d printed graft. Immunostaining of (a, c, f, h) UV100 and (b, d, g, i) UV500 sections to identify collagen deposition and ECM remodeling at the (a, b, f, g) 3 month and (c, d, h, i) 6 month time points illustrates that vascular neotissue in both groups was collagen-rich and active ECM turnover occurred in these constructs over 6 months. RT-qPCR of frozen graft explants for (i) Collagen I in 3d printed scaffolds and (j) Collagen III was similar in comparison to native IVC; scale bars, 100 μm.

To conclude, we examined and present here a novel method of 3D printing biodegradable materials for vascular tissue engineering. Overall this graft fabrication strategy enabled the printing of scaffolds with inner diameters of 1 mm and wall thicknesses of 150 μm which sustained patency and functionality over 6 months of implantation in the venous system of mice. The scaffolds and materials we designed and analyzed possessed adequate mechanical properties and were capable of supporting vascular tissue growth both in vitro and in vivo. Implantation of the 3D printed grafts within mice demonstrated the suturability and long-term efficacy of the scaffolds up to 6 months after surgery. Future efforts in this arena will incorporate more complex microarchitectural features along with patient-specific macroscale geometries. This material and technique provides a powerful platform that can be expanded upon for the study and development of customized vascular tissue engineering scaffolds utilizing 3D printing technologies.

Experimental Section

Experimental details can be found in the Supporting Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under the Award Number R01 AR061460 and through a seed grant from Children's National Sheikh Zayed Institute for Pediatric Surgical Innovation and the A. James Clark School of Engineering at the University of Maryland. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- [1].Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Magid D, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Schreiner PJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. Circulation. 2013:127. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Frommelt PC, Mitchell ME, Lamers LJ, Jaquiss RDB, Tweddell JS, Mussatto KA. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2012;143:1098. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Whitehead KK, Sundareswaran KS, Parks WJ, Harris MA, Yoganathan AP, Fogel MA. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2009;138:96. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.11.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dearani JA, Danielson GK, Puga FJ, Schaff HV, Warnes CA, Driscoll D, Schleck CD, Ilstrup D. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2003;75:399. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04547-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Petrossian E, Reddy VM, McElhinney DB, Akkersdijk GP, Moore P, Parry AJ, Thompson LD, Hanley FL. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1999;177:688. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(99)70288-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jonas RA, Freed MD, Mayer JE, Castaneda AR. Circulation. 1995;72:II77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cleveland DC, Williams WG, Razzouk AJ, Trusler GA, Rebeyka IM, Duffy L, Kan Z, Coles JG, Freedom RM. Circulation. 1992;86:II150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Stark J. Pediatr. Cardiol. 1998;86:II150. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Skardal A, Zhang J, Prestwich GD. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6173. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Yu Y, Zhang Y, Martin J. a, Ozbolat IT. J. Biomech. Eng. 2013;135:91011. doi: 10.1115/1.4024575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Nelson GN, Mirensky T, Brennan MP, Roh JD, Yi T, Wang Y, Breuer CK. Arch. Surg. 2008;143:488. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.5.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Melchiorri AJ, Hibino N, Brandes ZR, Jonas R. a, Fisher JP. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2013:1. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhang C, Wen X, Vyavahare NR, Boland T. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3781. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lee SJ, Heo DN, Park JS, Kwon SK, Lee JH, Lee JH, Kim WD, Kwon IK, Park S. a. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014;17:2996. doi: 10.1039/c4cp04801f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wang MO, Etheridge JM, Thompson J. a, Vorwald CE, Dean D, Fisher JP. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:1321. doi: 10.1021/bm301962f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Pataky K, Braschler T, Negro A, Renaud P, Lutolf MP, Brugger J. Adv. Mater. 2011:391. doi: 10.1002/adma.201102800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Billiet T, Vandenhaute M, Schelfhout J, Van Vlierberghe S, Dubruel P. Biomaterials. 2012;33:6020. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sell S. a, McClure MJ, Barnes CP, Knapp DC, Walpoth BH, Simpson DG, Bowlin GL. Biomed. Mater. 2006;1:72. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/1/2/004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Han DW, Park YH, Kim JK, Jung TG, Lee KY, Hyon SH, Park JC. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:1054. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lamm P, Juchem G, Milz S, Schuffenhauer M, Reichart B. Circulation. 2001;104:I. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].L'Heureux N, Pâquet S, Labbé R, Germain L, Auger FA. FASEB J. 1998;12:47. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].L'Heureux N, Dusserre N, Konig G, Victor B, Keire P, Wight TN, Chronos N. a F., Kyles AE, Gregory CR, Hoyt G, Robbins RC, McAllister TN. Nat. Med. 2006;12:361. doi: 10.1038/nm1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hibino N, Yi T, Duncan DR, Rathore A, Dean E, Naito Y, Dardik A, Kyriakides T, Madri J, Pober JS, Shinoka T, Breuer CK. FASEB J. 2011;25:4253. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-186585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Abedin M, Tintut Y, Demer LL. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004;24:1161. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000133194.94939.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Moe SM, Chen NX. Blood Purif. 2005;23:64. doi: 10.1159/000082013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].New SEP, Aikawa E. Circ. J. 2011;75:1305. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-11-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.