Abstract

Wide local excision (WLE) is a common surgical intervention for solid tumors such as those in melanoma, breast, pancreatic, and gastrointestinal cancer. However, adequate margin assessment during WLE remains a significant challenge, resulting in surgical re-interventions to achieve adequate local control. Currently no label-free imaging method is available for surgeons to examine the resection bed in vivo for microscopic residual cancer. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) enables real-time high-resolution imaging of tissue microstructure. Previous studies have demonstrated that OCT analysis of excised tissue specimens can distinguish between normal and cancerous tissues by identifying the heterogeneous and disorganized microscopic tissue structures indicative of malignancy. In this translational study involving 35 patients, a handheld surgical imaging OCT probe was developed for in vivo use to assess margins both in the resection bed and on excised specimens for the microscopic presence of cancer. The image results from OCT showed structural differences between normal and cancerous tissue within the resection bed following WLE of the human breast. The ex vivo images were compared to standard post-operative histopathology to yield sensitivity of 91.7% (95% CI: 62.5–100%) and specificity of 92.1% (95% CI: 78.4–98%). This study demonstrates in vivo OCT imaging of the resection bed during WLE with the potential for real-time microscopic image-guided surgery.

Keywords: cancer margins, human subjects, in vivo, optical coherence tomography, surgical guidance

Introduction

Wide local excision (WLE) is commonly performed in the surgical treatment of many solid tumors, with the goal to achieve local disease control by removing the primary tumor along with a surrounding rim of additional tissue. To minimize the physical and psychological morbidity associated with surgery, the smallest possible amount of normal tissue must be removed while still ensuring that the tumor tissue is completely excised. (1) Failure to excise all tumor tissue, as determined during conventional post-operative histopathology assessment of excised specimens, requires re-intervention to remove additional tissue.

Standard-of-care WLE specimen evaluation includes the surgeon’s estimate of tumor size based on pre-operative radiologic images (e.g. ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography) to plan the extent of resection, and intraoperative visual, tactile, and radiographic specimen evaluation, as well as post-operative gross and histological analysis, which can typically require several days. Additional methods for intraoperative assessment of tumor margins include frozen section (2) and touch-prep cytology (3) of the resected ex vivo specimen; however, these are infrequently used as they significantly extend surgery time, require real-time coordination with pathologists, and/or are highly operator-dependent. (4) It is also challenging to spatially correlate the analyzed regions on excised specimens with the corresponding locations in the resection bed. (5) As the currently available tools are limited, there is a compelling need to improve upon these existing intraoperative methods to enable real-time microscopic detection of residual disease both within the resection bed and on resected specimens.

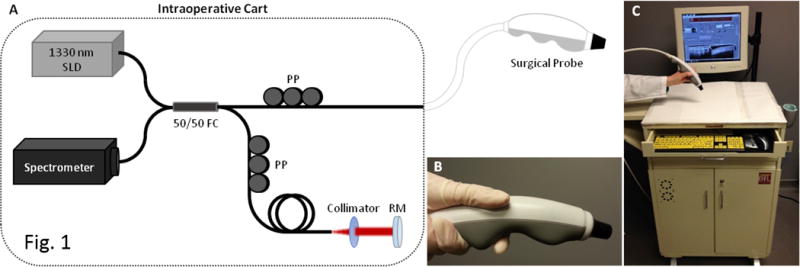

To address this need, we introduce in vivo label-free video-based imaging of the WLE resection bed. A unique custom-designed handheld imaging probe integrated with a custom-built portable Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) system (Fig. 1) is used for in vivo imaging during WLE in the human breast. OCT is a high-resolution label-free imaging technique that is analogous to ultrasound imaging, but offers resolutions that are 1–2 orders-of-magnitude higher. OCT relies on the use of near-infrared light instead of sound to image biological tissues with micrometer-scale (10−6 m) resolution, comparable to low-magnification histology, at depths up to 2 mm in dense tissue. (6) OCT has previously been used to image ex vivo tissue specimens for differentiation between normal and cancerous tissue (6–13), and a portable OCT system has been used for intraoperative imaging of ex vivo breast specimen margins and lymph nodes. (8–9)

Figure 1.

Handheld surgical imaging probe and portable OCT system for in vivo assessment of the WLE resection bed. (a) Schematic showing the OCT system components. (b) The handheld surgical probe is used by the surgeon to image inside the in vivo resection bed and across the excised tumor specimens. (c) The OCT system is integrated in a portable cart for easy transportation into the operating room and positioning near the sterile surgical field. Abbreviations: SLD: superluminescent diode; FC: fiber optic coupler; PP: fiber polarization paddle controller; RM: reference mirror.

Several systems have been developed for label-free intraoperative assessment of excised breast specimens. By measuring the local electrical properties of breast tissue from a 7 mm diameter region, a handheld probe (MarginProbe®, Dune Medical) applied to the surface of the excised tissue provides a positive or negative reading at each probe location. (14) A quantitative diffuse reflectance imaging (QDRI) instrument measures diffuse reflectance spectra from eight discrete sites during each acquisition in breast tumor specimens. (15) Fresh excised breast tumor specimens have also been rapidly imaged using confocal mosaicking microscopy. (16) Finally, ex vivo breast cancer tumor margins have been imaged using OCT needle probes (11) and full-field OCT. (13)

While these technologies are capable of assessing excised specimens, they have not been demonstrated for in vivo imaging in the resection bed. Ideally, both the ex vivo specimen and the WLE resection bed assessments should be performed during the surgical procedure, in real time, to best enable the surgeon to immediately decide whether further tissue excision is required. This would likely improve oncologic outcomes without having to resort to a second “take back” surgical procedure. The MarginProbe® and QDRI instruments are also not able to provide quantitative depth-resolved tumor tissue information, potentially making adherence to margin depth guidelines difficult. Furthermore, the unmet need for resection bed assessment methods is compounded by the challenges associated with existing point-by-point tissue assessment techniques or those with slow data acquisition rates, as these cannot be used practically to image the entire surface area of a surgical specimen while maintaining the high resolution needed to identify microscopic margin involvement. Most critically, none of these systems have been demonstrated for in vivo assessment of the WLE resection bed.

New label-free imaging methods such as OCT are often preferred for in vivo assessment because the regulatory path for translation to clinical use can potentially be shorter. Label-free imaging methods also avoid the risks associated with dye/drug reactions and the challenges associated with specific tumor targeting and non-specific binding. Several studies, however, have investigated the use of intravenously injected (17) or topically-applied (18) fluorescent dyes to discriminate tumor from normal tissue in wide-field optical fluorescence imaging. These methods, however, are more costly, require switching off room lighting to maximize detection of the weak fluorescence, and do not provide visualization of cellular features on the micrometer scale.

In contrast to other methods that are restricted to time-consuming point-by-point analysis, the handheld OCT probe system presented here provides a transverse scan range of 8.8 mm and an imaging rate of 11.5 frames per second. The handheld probe tip, which is placed in contact with tissue, can be manually swept over tissue surfaces to perform depth-resolved cross-sectional imaging over large tissue surfaces, where the images are captured as videos in a manner similar to that of an ultrasound probe. This method enables the surgeon to rapidly visualize and microscopically assess the entire resection bed in addition to the excised specimens. In this work, we demonstrate assessment of the resection bed immediately following primary breast tumor mass removal for the identification of residual in vivo tumor tissue.

Materials and Methods

Optical Coherence Tomography System

A portable custom-designed spectral-domain OCT system was developed to be easily maneuvered into the operating room and positioned close to the surgical field for real-time imaging of the in vivo resection bed during the primary WLE procedure. The OCT system (Fig. 1) employs a superluminescent diode source (Praevium Research, Inc.; 1330 nm center wavelength, 105 nm bandwidth) and a 50/50 fiber coupler to split light between the sample arm (the handheld surgical probe) and the reference arm. The reflected light is detected by a spectrometer and the 2D OCT images (B-scans) are displayed on the computer screen with axial and transverse resolutions of approximately 9 μm, an image width of 8.8 mm, and a frame rate of 11.5 frames/s. The laser power on the tissue is less than 10 mW. Images were collected as a video of frames as the probe was swept across the tissue. The custom-designed probe was draped with a sterile sheath before it was used for in vivo imaging of the resection bed.

Imaging Study Protocol

In this study, the portable OCT system and handheld probe were used to image 35 patients undergoing WLE (22 patients, including both primary and re-excision procedures) or mastectomy (13 patients) for biopsy-proven invasive and/or in situ breast carcinoma (see Table 1 for a summary of patient clinicopathological data) under protocols approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Carle Foundation Hospital (Urbana, Illinois, USA). Written informed consent for this IRB-approved study was obtained from all human subjects. Real-time videos and images of OCT data were acquired from both the in vivo resection bed and the excised tissue specimens in the operating room immediately following excision of the primary WLE specimen(s). For this study, the surgeons used their standard protocol for intraoperative assessment of margin adequacy and remained blinded to the results of data analysis. OCT data was not used for clinical decision making.

Table 1.

Summary of Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Lumpectomy/partial mastectomy | Complete mastectomy | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of subjects | 22 | 63% | 13 | 37% | 35 | |

|

| ||||||

| Age, years | ||||||

| Mean | 65 | 55 | 61 | |||

| St. Dev. | 11 | 14 | 13 | |||

| Range | 40–84 | 34–79 | 34–84 | |||

| ≤ 65 | 12 | 55% | 10 | 77% | 22 | 63% |

| > 65 | 10 | 45% | 3 | 23% | 13 | 37% |

|

| ||||||

| Surgical diagnosis* | ||||||

| Ductal carcinoma in situ | 14 | 64% | 9 | 69% | 23 | 66% |

| Lobular carcinoma in situ | 2 | 9% | 2 | 15% | 4 | 11% |

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 17 | 77% | 8 | 62% | 25 | 71% |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 2 | 9% | 2 | 15% | 4 | 11% |

| Invasive mammary carcinoma | 1 | 5% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 3% |

| Invasive micropapillary carcinoma | 1 | 5% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 3% |

| No tumor | 2 | 9% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 6% |

|

| ||||||

| Tumor size (greatest dimension) | ||||||

| < 1 cm | 9 | 41% | 4 | 31% | 13 | 37% |

| 1–2 cm | 9 | 41% | 2 | 15% | 11 | 31% |

| > 2 cm | 3 | 14% | 7 | 54% | 10 | 29% |

| No tumor | 2 | 9% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 6% |

|

| ||||||

| Closest tumor margin | ||||||

| < 1 mm | 3 | 13% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 8% |

| 1–3 mm | 9 | 39% | 1 | 8% | 10 | 28% |

| > 3 mm | 9 | 39% | 12 | 92% | 21 | 58% |

| No tumor | 2 | 9% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 6% |

|

| ||||||

| Specimen imaging | ||||||

| # of imaged margins | 31 | 23 | 54 | |||

| Cancer | 5 | 16% | 0 | 0% | 5 | 9% |

| No cancer | 21 | 68% | 5 | 22% | 26 | 48% |

| Lacking histology correlation | 5 | 16% | 8 | 35% | 13 | 24% |

|

| ||||||

| Additional margin resection | ||||||

| # of imaged margins | 16 | 1 | 17 | |||

| Cancer | 3 | 19% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 18% |

| No cancer | 12 | 75% | 0 | 0% | 12 | 71% |

| Lacking histology correlation | 1 | 6% | 1 | 100% | 2 | 12% |

Note: Multiple tumor types may occur in same patient.

The surgical procedures were performed at Carle Foundation Hospital (Urbana, Illinois, USA) using the following protocol. (1) The surgeon excised the primary WLE specimen and determined if excision of additional tissue was necessary via palpation, visual inspection, and, optionally, specimen radiography. (2) The surgeon used the handheld OCT probe to sweep across the six aspects (posterior, anterior, superior, inferior, medial, and lateral) of the in vivo resection bed, collecting real-time video-based OCT images. (3) The surgeon optionally excised additional tissue as a result of the intraoperative standard-of-care margin analysis in Step 1. OCT data was not used for interventional decision-making. (4) If additional tissue was excised, the surgeon used the handheld OCT probe to image the new aspect(s) of the resection bed. (5) All excised tissue specimens were evaluated with the handheld OCT probe in the operating room by the research staff. (6) Specimens were marked with dye at the OCT imaging sites for correlation and returned to the operating room staff for routine histopathological examination by a board-certified pathologist.

Image Analysis

The OCT images were visually analyzed to assess the tissue composition and presence/absence of cancer. Structural features in the OCT images were distinguished by differences in scattering intensity in the OCT images. (8) Low sparse scattering which forms a relatively uniform “honeycomb” structure is characteristic of normal adipose (fatty) tissue. Banded and fibrous structures indicate normal stromal tissue and collagen. Heterogeneous dense, high scattering patterns and irregular disruption in the structure indicates tissue that is suspicious for malignancy.

Statistical Analysis

A blinded reader study was performed to evaluate the statistical performance of the OCT imaging system in assessing tumor margins. Fifty (50) OCT images from 21 patients were analyzed by 5 trained OCT readers who were blinded to whether the image contained cancer or not. The readers were given a training set of sample OCT images showing normal adipose and stromal breast tissue as well as images portraying cancerous features. The corresponding histology images from the same tissue locations were independently analyzed by a trained pathologist who determined that 12 of the images contained cancer and 38 of the images were not cancerous. In order to assess intra-reader variability a duplicate set of the 50 images were reversed (left to right) and the total 100 images were randomly arranged. Each image was viewed separately in a slide show and readers were instructed to view and assess the images sequentially and not go back to review previous images. The images were scored on a scale of 1 to 4 as follows: (1) a score of 1 means that the reader is confident the image is negative for cancer; (2) a score of 2 means that reader thinks that the image is likely negative for cancer, but there is some doubt; (3) a score of 3 means that the reader thinks that cancer is likely present, but there is some doubt; (4) a score of 4 means that the reader is confident the image is positive for cancer.

Results

In Vivo OCT Imaging of the Surgical Tumor Bed

Of the 22 WLE patients that were imaged for this study, 3 were found to have positive or “very close” margins (0‐1 mm) on histological analysis and another 10 were found to have cancer within 1–3 mm of the margin. None of the mastectomy patients were found to have positive margins. Imaging results from two representative cases are shown below.

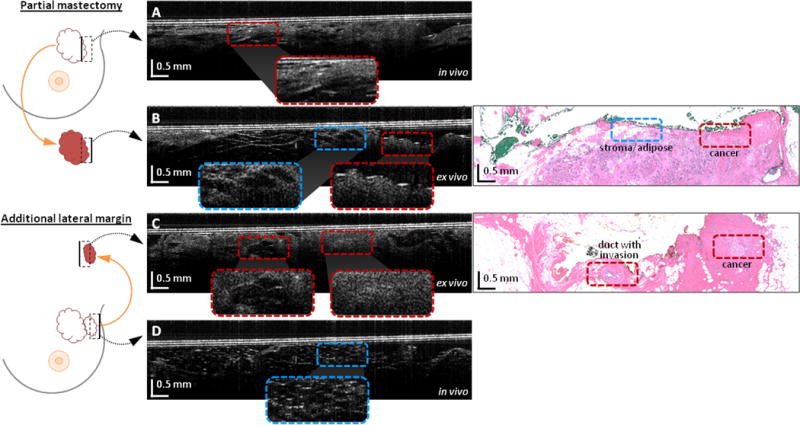

The OCT and histopathology results from the first representative case: a 72-year-old woman undergoing WLE for biopsy-proven invasive ductal carcinoma of the left breast are shown in Fig. 2. After excision of the primary WLE specimen, OCT videos and images were acquired from all six aspects of the resection bed by the surgeon using the handheld OCT probe. OCT imaging of the lateral aspect of the resection bed, of which one image is shown in Fig. 2A, suggested a positive margin based on the microscopic architecture and scattering features present within the video data, which was confirmed as DCIS on post-operative histological examination. Within the same operation, an additional lateral margin specimen was removed and the surgeon again used the handheld probe to acquire OCT video images within the resection bed. OCT imaging of the lateral aspect of the resection bed after re-excision, of which one image is shown in Fig. 2D, indicated a negative margin. In addition to the in vivo OCT assessment of the resection bed, ex vivo video images from the corresponding regions on the excised specimens (shown in Fig. 2B and 2C) were acquired during the WLE procedure. Strong correspondence was found between in vivo (before excision) and ex vivo (after excision) OCT images of the same tissue region (see Fig. 2A and 2C) and post-operative histopathology. Note that histology images are only provided for the corresponding OCT images in 2B and 2C since the images in 2A and 2D were acquired in vivo and hence do not have histology images to compare. An OCT video acquired during the surgeon’s sweep of the cavity showing an example positive margin is shown in Supplementary Video S1.

Figure 2.

Video OCT cross-sectional images of a positive tumor margin from the in vivo resection bed and ex vivo excised tissue. Images are from a 72 year-old female WLE patient with invasive ductal carcinoma of the left breast. Diagrams on the left indicate the imaged regions (dashed boxes) of the resection bed or the excised specimen (not to scale), and the solid black lines in the black dashed boxes indicate the top of the corresponding OCT image. (a) OCT image of the positive in vivo lateral tumor margin. (b) OCT image of the positive ex vivo lateral specimen margin, with corresponding histology. (c) OCT image of the positive additional ex vivo lateral margin tissue (same tissue as imaged in vivo in (a)), with corresponding histology. (d) OCT image of the final negative in vivo lateral margin. Areas of interest are magnified and shown in the insets to compare normal stroma and adipose with cancerous regions. Note that histology images are only provided for the corresponding OCT images in 2B and 2C since the images in 2A and 2D were acquired in vivo and hence do not have histology images to compare.

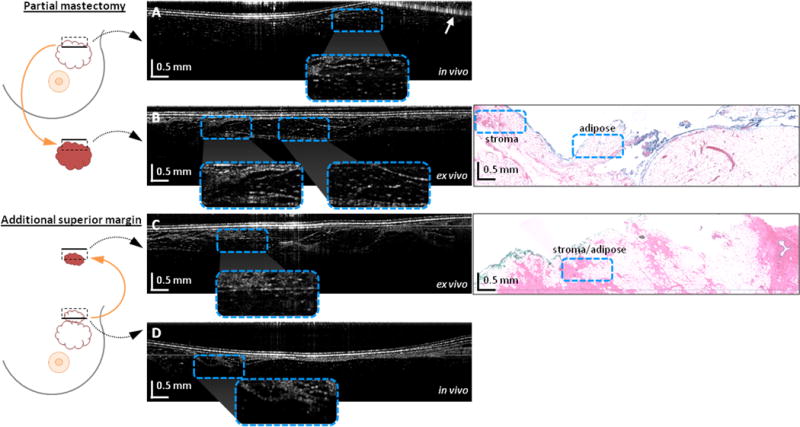

Fig. 3 shows the OCT and histology results from a second representative case: a 56 year-old woman undergoing WLE for biopsy-proven invasive ductal carcinoma of the left breast. As in the previous case, OCT video images were obtained from all six aspects of the in vivo resection bed and the primary WLE specimen. OCT imaging of the superior aspect of the resection bed, of which one image is shown in Fig. 3A, suggested a negative margin containing regions of adipose and normal breast stroma, which was confirmed on post-operative histological examination. Within the same operation, the surgeon removed additional tissue from the superior margin, as it was deemed suspicious based on visual and tactile assessment during the surgery. Final post-operative histological analysis, however, confirmed the intraoperative OCT finding of a negative margin, which meant that the additional normal tissue was removed unnecessarily. An OCT video acquired during the surgeon’s sweep of the cavity showing an example negative margin (from a different subject) is shown in Supplementary Video S2.

Figure 3.

Video OCT cross-sectional images of a negative tumor margin from the in vivo resection bed and ex vivo excised tissue. Images are from a 56 year-old female WLE patient with invasive ductal carcinoma in the left breast. Diagrams on the left indicate the imaged regions (dashed boxes) of the resection bed or excised specimen (not to scale), and the solid black lines in the black dashed boxes indicate the top of the corresponding OCT image. (a) OCT image of the negative in vivo superior tumor margin. (b) OCT image of the negative ex vivo superior specimen margin, with corresponding histology. (c) OCT image of the negative additional ex vivo superior margin tissue (same tissue as imaged in vivo in (a)), with corresponding histology. (d) OCT image of the final negative in vivo superior margin. Areas of interest are magnified and shown in the insets to compare the normal stroma and adipose regions. The top right of the image in (a) is obscured by a complex conjugate artifact (arrow). Note that histology images are only provided for the corresponding OCT images in 3B and 3C since the images in 3A and 3D were acquired in vivo and hence do not have histology images to compare.

Statistical Analysis

The results of the blinded reader analysis are summarized in Table 2, showing the sensitivity (Sens.) and specificity (Spec.) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy (Acc). The images were declared negative if given a score of 1 and positive/suspicious if given a score of 2, 3 or 4. This represents a division of the responses by declaring the image as positive if there is any level of suspicion of cancer (a score of 2, 3, or 4) and declaring the image as negative only if the reader was fully confident that there was no cancer in the image (a score of 1), which represents the clinical scenario where any margin considered “suspicious” (i.e. not fully confident to be negative) would subsequently be removed and the region would be reimaged to determine if it is clear. The table lists the statistics for the individual readers as well as a “majority vote” where the image is declared positive or negative if at least 3 out of 5 readers gave a response of positive or negative, respectively. The statistical results are calculated from the 50 unique images (with duplicates removed). Overall, the analysis resulted in sensitivity of 91.7% (95% CI: 62.5–100%) and specificity of 92.1% (95% CI: 78.4–98%). Intra-reader analysis (including duplicates) showed that out of a total of 250 scoring sets (5 readers, 50 sets of images) there were 41 sets where a reader assigned different scores to the duplicates images and 11 (out of the 41) cases where a reader switched from a score leaning toward negative (1 or 2) to a score leaning toward positive (3 or 4). Overall, the intra-reader variability was low (16.4% and 0.04%, respectively).

Table 2.

Summary of statistics from OCT analysis of 50 ex vivo images. The table lists the sensitivity and specificity (with 95% confidence intervals), positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and accuracy (Acc) for each of five blinded readers and from a majority (three out of five readers).

| Reader | Sens. | 95% CI | Spec | 95% CI | PPV | NPV | Acc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 83.3 | 54.0 – 96.5 | 89.5 | 75.3 – 96.4 | 71.4 | 94.4 | 88 |

| 2 | 91.7 | 62.5 – 100 | 47.4 | 32.4 – 62.7 | 35.5 | 94.7 | 58 |

| 3 | 33.3 | 13.6 – 61.2 | 97.4 | 85.3 – 100 | 80 | 82.2 | 82 |

| 4 | 72.7 | 42.9 – 90.8 | 84.6 | 70.0 – 93.1 | 57.1 | 91.7 | 82 |

| 5 | 83.3 | 54.0 – 96.5 | 86.8 | 72.2 – 94.7 | 66.7 | 94.3 | 86 |

|

| |||||||

| Majority (3:5) | 91.7 | 62.5 – 100 | 92.1 | 78.4 – 98.0 | 78.6 | 97.2 | 92 |

Discussion

The results presented here show high-resolution label-free video-based imaging of the resection bed following WLE of the human breast. We have demonstrated that differences in the microstructural features of OCT images enable differentiation between normal and tumor tissue within the in vivo resection bed, and that these features correlate well with ex vivo OCT images and post-operative histopathology from the same regions. The results in Fig. 2 show similar features in the tissue imaged in vivo (Fig. 2A) and the same tissue imaged ex vivo (Fig. 2C), while differences are seen between the additional tissue margin imaged in vivo (Fig. 2C) and the cross-border margin imaged ex vivo on the primary tumor specimen. These differences can be due to changes in the tissue features due to extraction and handling during and following excision. Although exact correlation with histology is difficult due to tissue processing artifacts, distinct features indicative of positive tumor margins are evident in both OCT and histology images, and both correlate with and validate similar findings in prior studies. (7, 8, 11) Moreover, OCT images of the in vivo resection bed correlate with the ex vivo cross-border regions of the same margin on the resected tumor specimen.

The primary focus of this study was to demonstrate in vivo OCT imaging of the surgical cavity during wide local excision. In order to perform a blinded reader study to assess sensitivity and specificity the OCT images must be compared to the gold standard histology at the corresponding tissue locations. Since histology cannot be used for comparison with the OCT images acquired in vivo, the analysis was performed using the excised specimens (both primary and additional margins). For the cases where additional margins were removed during the surgery, the tissue specimen was imaged both in vivo and ex vivo; however, the specimen was inked at the OCT imaging location only after excision, so only the ex vivo images can be directly correlated with histology.

The outcome of any blinded image analysis study is highly dependent on the training received by the readers. For this study the training set of images given to the readers was very limited since the small number of positive images were reserved for the analysis. The statistical analysis shows a wide discrepancy between the five blinded readers. Readers 1 and 5 had previous experience studying OCT images of breast tissues (not related to this study). Readers 2 and 4 had previous experience studying OCT images of other tissue types. Reader 3 had almost no previous experience studying OCT images of any type. The use of a “majority vote” for the margin assessment compensates for variability in reader experience.

Intra-reader analysis was performed by comparing the grades given by the readers on duplicate images that were reversed (left to right). Some readers commented that they recognized a few of the images and suspected that they were duplicated; however, they viewed the images sequentially and were not permitted to go back to check what they had scored previous images. The overall low intra-reader variability (16.4% and 0.04%, respectively) increases confidence in the readers’ ability to assess OCT images.

The statistical analysis was performed using the OCT images collected from ex vivo specimens in order to directly compare the blinded analysis to the gold standard “true” responses from histology. Since histology cannot be performed on in vivo tissues which were imaged within the surgical cavity inside the human subject, direct correlation and analysis could not be performed for in vivo imaging. However, the OCT images shown in Figs. 2 and 3 show the ability of OCT to image corresponding features of the “mirror image” cross-border regions from the in vivo and ex vivo tissues. The in vivo performance of the system will be assessed in future studies where the surgeon would use the information provided by OCT for interventional decisions, compared to the cases where the surgeon would only use current standard assessment methods (e.g. visual cues, palpation). Additionally, ongoing studies which are investigating the OCT/optical differences between tumor types will likely be useful for future intraoperative tumor pathology identification.

OCT image quality can potentially be further improved using computational methods such as interferometric synthetic aperture microscopy (ISAM), (19, 20) a computed real-time 3D microscopic image reconstruction technique which addresses the inverse-scattering challenge in coherence microscopy. ISAM correction offers spatially-invariant resolution throughout the imaged tissue volume, equivalent to that traditionally limited to the focal plane, and thereby eliminating the compromise between transverse resolution and depth-of-field. (19, 20) ISAM-corrected OCT images of excised breast tumor tissue have shown meaningful structures at distances well outside the focal plane and normal depth-of-field (20), demonstrating the potential to further improve real-time in vivo imaging capabilities in the surgical setting.

This work demonstrates real-time label-free video-based imaging of the in vivo resection bed following WLE to detect microstructural changes characteristic of residual cancer. The incorporation of a custom-designed handheld OCT surgical probe places the technology in the surgeon’s hand for immediate assessment during the primary surgery. The ability to optically image label-free inside the tumor cavity and across the resection bed addresses the critical need for improved intraoperative detection of residual disease in order to ensure local control, and to potentially eliminate re-intervention due to post-operative margin findings. Future work will involve OCT imaging of the in vivo resection bed during other surgical procedures such as for melanoma, pancreatic, gastrointestinal, and thyroid cancer.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Video S1. Positive surgical margin. Video OCT cross-sectional images of a positive tumor margin from the in vivo resection bed of a 72 year-old female WLE patient with invasive ductal carcinoma as the surgeon sweeps the handheld probe along the margin.

Supplementary Video S2. Negative surgical margin. Video OCT cross-sectional images of a negative tumor margin from the in vivo resection bed of a 72 year-old female WLE patient with invasive ductal carcinoma as the surgeon sweeps the handheld probe along the margin.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Darold Spillman for his operations and information technology support for this research. We also thank the clinical research and surgical nursing staff at Carle Foundation Hospital for their contributions.

Financial support: This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (1 R01 EB012479 and 1 R01 CA166309, S.A.B.). S.J.E-B. was supported by a Beckman Institute Fellowship.

Footnotes

Author contributions: S.J.E-B., R.M.N, N.D.S., and S.G.A. constructed the OCT system, operated the OCT system in the operating room, analyzed results, and wrote the paper. J.P., D.D., D.T.M., A.J.C., and A.M.Z. designed and constructed the handheld surgical imaging probe. M.M. and E.J.C. coordinated imaging and surgical schedules, managed the IRB protocol, and analyzed data. G.L.M. and F.A.S. operated the OCT system and collected data. K.A.C., M.S., and P.S.R. performed the surgeries and acquired OCT video image data. Z.G.L. analyzed the histopathological findings. S.A.B. conceived of the idea, designed the study, obtained funding, analyzed results, and edited the paper.

Conflict of interests: S.A.B. is co-founder of Diagnostic Photonics, which is licensing intellectual property from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign related to Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Microscopy. All other authors have no conflicts.

References

- 1.Singletary SE. Surgical margins in patients with early-stage breast cancer treated with breast conservation therapy. Am J Surg. 2002;184(5):383–393. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)01012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jorns JM, Visscher D, Sabel M, Breslin T, Healy P, Daignaut S, et al. Intraoperative frozen section analysis of margins in breast conserving surgery significantly decreases reoperative rates: one-year experience at an ambulatory surgical center. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;138(5):657–69. doi: 10.1309/AJCP4IEMXCJ1GDTS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Halluin F, Tas P, Rouquette S, Bendavid C, Foucher F, Meshba H, et al. Intra-operative touch preparation cytology following lumpectomy for breast cancer: a series of 400 procedures. Breast. 2009;18(4):248–53. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emmadi R, Wiley EL. Evaluation of resection margins in breast conservation therapy: the pathology perspective-past, present, and future. Int J Surg Oncol. 2012;2012:180259. doi: 10.1155/2012/180259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molina MA, Snell S, Franceschi D, Jorda M, Gomez C, Moffat FL, et al. Breast specimen orientation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(2):285–288. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0245-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boppart SA, Luo W, Marks DL, Singletary KW. Optical coherence tomography: feasibility for basic research and image-guided surgery of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;84(2):85–97. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000018401.13609.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsiung PL, Phatak DR, Chen Y, Aguirre AD, Fujimoto JG, Connolly JL. Benign and malignant lesions in the human breast depicted with ultrahigh resolution and three-dimensional optical coherence tomography. Radiology. 2007;244(3):865–74. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2443061536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen FT, Zysk AM, Chaney EJ, Kotynek JG, Oliphant UJ, Bellafiore FJ, et al. Intraoperative evaluation of breast tumor margins with optical coherence tomography. Cancer Res. 69(22):8790–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen FT, Zysk AM, Chaney EJ, Adie SG, Kotynek JG, Oliphant UJ, Bellafiore FJ, Rowland KM, Johnson PA, Boppart SA. Optical coherence tomography: the intraoperative assessment of lymph nodes in breast cancer. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 2010;29(2):63–70. doi: 10.1109/MEMB.2009.935722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuo WC, Kim J, Shemonski ND, Chaney EJ, Spillman DR, Jr, Boppart SA. Real-time three-dimensional optical coherence tomography image-guided core-needle biopsy system. Biomed Opt Express. 2012;3(6):1149–61. doi: 10.1364/BOE.3.001149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLaughlin AG, Quirk BC, Curatolo A, Kirk RW, Scolaro L, Lorenser D, et al. Imaging of breast cancer with optical coherence tomography needle probes: feasibility and initial results. IEEE J Sel Top Quantum Electron. 2012;18:1184–1191. [Google Scholar]

- 12.John R, Adie SG, Chaney EJ, Marjanovic M, Tangella KV, Boppart SA. Three-dimensional optical coherence tomography for optical biopsy of lymph nodes and assessment of metastatic disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(11):3685–93. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2434-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Assayag O, Antoine M, Sigal-Zafrani B, Riben M, Harms F, Burcheri A, et al. Large field, high resolution full-field optical coherence tomography: A pre-clinical study of human breast tissue and cancer assessment. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2014;13(5):455–68. doi: 10.7785/tcrtexpress.2013.600254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnabel F, Boolbol SK, Gittleman M, Karni T, Tafra L, Feldman S, et al. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(5):1589–95. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3602-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown JQ, Bydlon TM, Kennedy SA, Caldwell ML, Gallagher JE, Junker M, et al. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abeytunge S, Li Y, Larson B, Peterson G, Seltzer E, Toledo-Crow R, et al. Confocal microscopy with strip mosaicing for rapid imaging over large areas of excised tissue. J Biomed Opt. 2013;18(6):61227. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.18.6.061227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tummers QR, Verbeek FP, Schaafsma BE, Boonstra MC, van der Vorst JR, Liefers GJ, et al. Real-time intraoperative detection of breast cancer using near-infrared fluorescence imaging and Methylene Blue. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:850–858. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.02.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Urano Y, Sakabe M, Kosaka N, Ogawa M, Mitsunaga M, Asanuma D, et al. Rapid cancer detection by topically spraying a γ-glutamyltranspeptidase-actived fluorescent probe. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:110ra119. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmad A, Shemonski ND, Adie SG, Kim HS, Hwu WM, Carney PS, et al. Real-time in vivo computed optical interferometric tomography. Nat Photonics. 2013;7(6):444–448. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2013.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ralston TS, Marks DL, Carney PS, Boppart SA. Interferometric synthetic aperture microscopy. Nat Phys. 2007;3:129–34. doi: 10.1038/nphys514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Video S1. Positive surgical margin. Video OCT cross-sectional images of a positive tumor margin from the in vivo resection bed of a 72 year-old female WLE patient with invasive ductal carcinoma as the surgeon sweeps the handheld probe along the margin.

Supplementary Video S2. Negative surgical margin. Video OCT cross-sectional images of a negative tumor margin from the in vivo resection bed of a 72 year-old female WLE patient with invasive ductal carcinoma as the surgeon sweeps the handheld probe along the margin.