Abstract

Youths’ risk for adjustment problems in contexts of political violence is well-documented. However, outcomes vary widely, with many children functioning well. Accordingly, moving beyond further documenting the risk for many negative outcomes associated with living in contexts of political violence, a second generation of research is moving towards identifying the mechanisms and conditions that contribute to children’s adjustment. Increasing support is emerging for understanding effects on children in terms of changes in the social contexts in which children live, and in the psychological processes engaged by these social ecologies. Selected themes are considered, including (a) the need to study multiple levels of the social ecology, (b) differentiating between the effects of exposure to contexts of political versus non-political violence, and (c) theories about explanatory processes. Selected research pertinent to these directions is reviewed, including findings from a six-wave longitudinal study on political violence and children in Northern Ireland.

Keywords: Political violence, Social ecological model, Community violence, Family conflict, Child adjustment, Emotional security

Given the prevalence and extent of violent conflicts throughout the world, understanding the impact of political violence on children is an urgent concern, identified as a strategic goal of the Society for Research in Child Development (Masten, 2013). A first generation of research encompassing hundreds of studies has documented the risk for maladjustment associated with exposure to political violence across a wide range of negative outcomes, including externalizing problems (e.g. aggression), internalizing disorders (e.g. depression), and post-traumatic stress symptoms. Yet outcomes are also found to vary widely, with some youth evidencing positive functioning in the face of threats and challenges (Barber, 2013). Given this diversity of outcomes, a second generation of research is now urgently needed to elevate understanding of processes accounting for relations between political violence and child development, including identifying the mechanisms and conditions that relate to risk for maladjustment or foster positive outcomes (Cummings, Goeke-Morey, Schermerhorn, Merrilees, & Cairns, 2009; Sagi-Schwartz, 2008). Although calls for such research were first made over a decade and a half ago (e.g., Cairns & Dawes, 1996), the rigorous, longitudinal studies, guided by well-articulated theories, required to accomplish such a new level of understanding are only now emerging (e.g., Betancourt, Brennan, Rubin-Smith, Fitzmaurice, & Gilman, 2010; Dubow et al., 2010; Qouta, Punamäki, Montgomery, & El Sarraj, 2007).

This second generation of research can be characterized as reflecting a social-ecological, process-oriented perspective, consistent with the principles of developmental psychopathology, including concern with process as well as outcome, differentiating contextual influences, and interest in positive as well as negative influences, effects, and outcomes (Cummings & Valentino, in press). It typifies a small but growing body of research (e.g., Betancourt et al., 2010; Cummings et al., 2009; Dubow, Huesmann, & Boxer, 2009). This work reflects an emerging conceptualization of the impact of political violence on children in terms of effects on communities, families, and other contexts in which children live, including interest in the psychological processes engaged by these social ecologies. Another characteristic is longitudinal research designs that can identify directional relations between the social environments associated with political violence, mediating contextual or psychological processes, and child maladjustment and positive outcomes (e.g., for findings related to prosocial outcomes, see Taylor, et al., in press).

In this paper, research and theory is considered on selected topics consistent with a process-oriented social-ecological model. Topics include: (a) a social-ecological model as a framework for studying children and political violence; (b) differentiating contexts to determine effects attributable to political violence as opposed to other contextual influences, and (c) testing theories about specific explanatory processes. We address these topics with results from our research studying the impact on children of political violence in Belfast, Northern Ireland.

A Six-Wave Longitudinal Study

Since 2005, we have been conducting research based on a social-ecological, process-oriented perspective for the effects of political violence on child development in Northern Ireland (Cummings et al., 2009). This longitudinal study has involved 999 mother-child dyads drawn from economically-deprived neighborhoods in Belfast. Six waves of data were collected over consecutive years (with about 80–85% retention between waves). Children were evenly divided in gender and ranged in age from very early to late adolescence, with mean age about 12 years old at the initiation of the study. The study neighborhoods reflected the separation between Catholics and Protestants; the majority of study participants lived in homogenous wards (over 90% Catholic or Protestant) that were interfaced, that is, shared a border with neighborhoods predominately populated by the “other” group.

The Social-Ecological Model: A Framework for Studying Political Violence and Children

In order to better understand relations between political violence and child development, multiple levels of societal functioning require investigation. This social-ecological approach includes incorporating effects associated with the communities, families, and broader social contexts in which children live. A guiding assumption is that political violence does not only impact children as a “main effect,” but also as a function of the intervening contextual and psychological processes engaged by the social ecology of intergroup conflict.

Following an influential conceptualization by Bronfenbrenner (1979), we, and others (e.g., Betancourt et al., 2010; Boxer et al., 2013), are programmatically testing social- ecological, process-oriented frameworks for the effects of political violence on child development (Cummings et al., 2009; see our model in Figure 1). The fundamental concept of a social-ecological model is broad, with theorists and researchers varying in the elements studied across a wide range of areas of political violence worldwide. Given the great scope and extent of the social ecology, and possible differences across contexts of political violence, investigators must decide on which elements to focus, guided by an assessment of salient factors in a particular region. Dubow et al. (2009) proposed a social ecological framework for studying political violence and children in Israel and Palestine, focusing on cognitive processes as explanatory variables. Betancourt, McBain, Newnham, and Brennan (2013) have documented the significance of the post-accord period for the adjustment and well-being of former child soldiers in Sierra Leone. In Belfast, as in many other areas world-wide, post-accord violence and tension between conflicting groups persists, with an impact on the children.

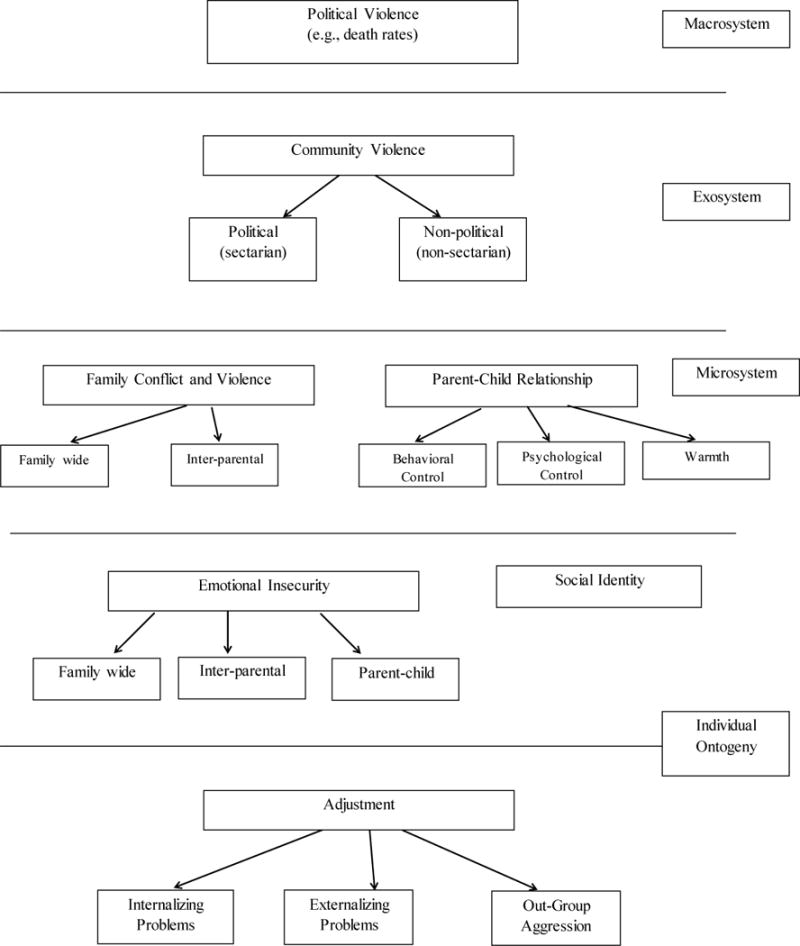

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework for social ecology of political violence in Northern Ireland. Adapted from Cummings et al. (2009).

An important first step in a research program from a social-ecological perspective is to hypothesize the elements of the social ecology to be examined in a region. Consistent with the assumptions of a social-ecological perspective, the model guiding our research program includes multiple levels, including the macrosystem (e.g., historical political violence), the exosystem (e.g., sectarian and non-sectarian community violence), the microsystem (e.g., family, martial violence and parenting), and individual ontogeny (e.g., emotional insecurity, social identity, maladjustment) (see Figure 1).

Distinguishing between Political (Sectarian) and Non-Political Community Violence

We posited at the outset that political violence affecting children and families occurs at the community level and that politically-motivated (sectarian) violence is unique in expression compared to community violence that is not politically motivated. Moreover, we hypothesized that (a) sectarian community violence would have distinctive effects on children compared to community violence that was not politically-motivated, reflecting the particular impact of violence associated with sectarian conflict, and (b) the mechanisms by which sectarian community violence affected child adjustment may differ compared with non-sectarian community violence. We posited that sectarian community violence would be more likely to elevate insecurity, thereby increasing risk for maladjustment by this mechanism, because it posed particular threats to intercommunity relations and the integrity of the political system and to the individual’s personal identity by being directed at people like oneself. Accordingly, prior to initiating our longitudinal study, we conducted focus group and pilot research to develop psychometrically-supported measures that distinguished politically-motivated (e.g., blast bombs exploded by the other community; stones or other objects thrown over walls dividing communities) and non-political (e.g., home break-ins; robberies/muggings) community violence (Goeke-Morey et al., 2009; Taylor et al., 2011; see Cummings. Schermerhorn et al., 2010, for the specific items on these scales).

Results have supported the significance of distinguishing these forms of community violence. Compared to non-sectarian community violence, youth’s emotional insecurity is more impacted by sectarian violence, with elevated insecurity shown to mediate relations with youth maladjustment. For example, Cummings, Schermerhorn et al. (2010) reported that sectarian community violence influenced family conflict and children’s reduced security about family and community, with links to adjustment problems indexed by the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ, Goodman, 1997). A pathway to youth adjustment problems through heightened emotional insecurity did not emerge for non-sectarian community violence. Supporting the cogency of conceptualizing the impact of political violence through the lens of a social ecological model (see Figure 1), Cummings, Merrilees and colleagues (2010) found (a) historical political violence predicted both sectarian and non-sectarian community violence, (b) sectarian community violence was associated with marital conflict and reduced parental monitoring, (c) sectarian community violence and marital conflict were each related to children’s emotional insecurity, which, in turn, (d) predicted externalizing and internalizing problems.

Relatedly, Cummings, Merrilees et al. (2013), based on three-level modeling, which allows for the study of inter-individual differences in intra-individual change and nesting by neighborhood, sectarian community violence over time was linked with youth adjustment problems on the SDQ. This link was accentuated in neighborhoods with higher crime rates, suggesting that the impact of political violence on youth adjustment is elevated in high crime areas. Further underscoring the psychological impact of sectarian community violence, Taylor et al. (2011) found that mothers reported vivid differences in focus group discussions between experiences with sectarian and non-sectarian violence, with participants describing pulling together and greater in-group social cohesion in reaction to sectarian violence. These evaluations by mothers suggest the particular risk posed by sectarian community violence. Relatedly, Shirlow et al. (2013) reported that mothers’ perceived sectarian crime was disproportionately much greater than perceived nonsectarian crime indexed by recorded reports by police. Thus, the psychological significance of sectarian violence far exceeded what the base rates of these incidents would suggest.

However, it is important to recognize that non-sectarian community violence has also, albeit less consistently, been associated with youth adjustment problems in Belfast. For example, Cummings et al. (2011) reported relations between non-sectarian community violence and youth maladjustment, although emotional insecurity did not mediate these relations. Thus, nonsectarian community violence is related to youth adjustment problems, but sectarian community violence is more consistently related to youth maladjustment when both types of community violence are included in the same statistical models, with emotional insecurity only mediating relations with youth maladjustment for sectarian community violence. In summary, although both forms of community violence pose risk for youth maladjustment, sectarian community violence underscores the particular problems for youth development presented by political violence.

The Importance of Theories about Explanatory Processes

Theory is essential for achieving adequate understanding of the processes underlying relations between political violence and child development, including the mechanisms and conditions accounting for maladjustment or fostering positive functioning (Masten & Narayan, 2012). Extending the extensive literature documenting negative outcomes for youth of exposure to political violence, research is now beginning to present, and systematically test, the propositions of well-articulated theoretical models in the context of multi-wave, longitudinal research designs.

Emotional Security Theory (EST)

EST has a foundation in attachment theory concerned with emotional security in parent-child relationships (Bowlby, 1969) and children’s emotional security in contexts of marital conflict and violence (Cummings & Davies, 2010), and has recently been extended outside the family system to explain children’s functioning in the face of community conflict and violence (Cummings et al., 2009). Emotional security is conceptualized as a set goal, fundamental to youths’ adaptive emotional, behavior, cognitive, and physiological regulatory responses in threatening contexts, such as family or community violence. Youth who sense their family and community are safe havens can utilize parents and neighbors to provide security and protection (Qouta, Punamäki, & El Sarraj, 2008). A growing body of empirical studies demonstrates relations between emotional insecurity and maladjustment in response to violence at different levels of the social ecology (Cummings & Davies, 2010). Facing political violence threatens children’s appraisals of felt-security, stability and safety in socio-emotional environments (e.g., Bar-Tal & Jacobson, 1998; Bleich, Gelkopf, & Solomon, 2003; Jordans et al., 2010; McAloney, McCrystal, Percy, & McCartan, 2009; Sagi-Schwatz, 2012). Thus, guided by EST, we have explored the hypothesis that the effects of political violence on children’s adjustment are mediated, at least in part, by children’s emotional insecurity about multiple levels of the social ecology, including the family and community.

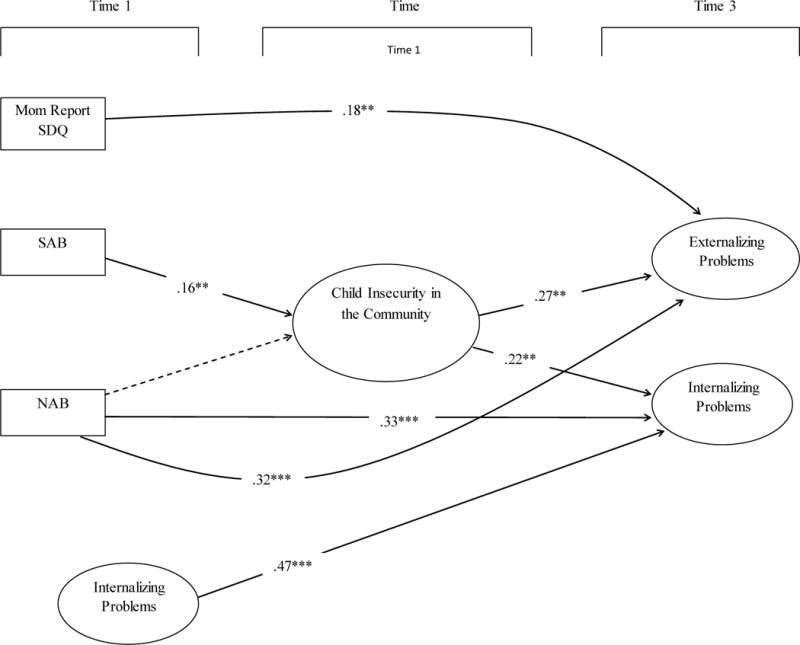

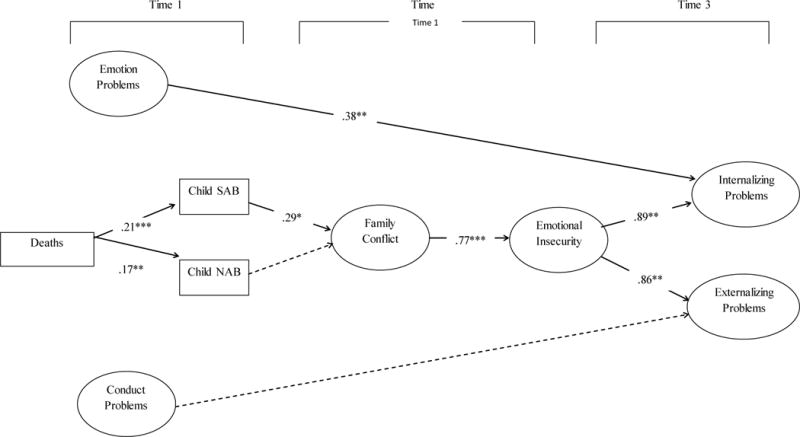

Our recent research further supports that youths’ emotional insecurity about both the community and family are psychological processes mediating the effects of political violence on children’s maladjustment. Cummings et al. (2011) specifically tested emotional insecurity about the community as a mediator in relations between sectarian community violence and youths’ externalizing and internalizing problems as assessed by mother and child report on the SDQ. Based on a three-wave model test, with controls for initial levels of adjustment, emotional insecurity about the community fully mediated relations between sectarian community violence and youths’ externalizing and internalizing problems (Figure 2). Cummings et al. (2012) specifically tested emotional insecurity about the family as a mediator in relations between sectarian community violence and youths’ adjustment problems. Based on a three-wave model test, with controls for initial levels of adjustment, family conflict and emotional security about the family fully mediated relations between sectarian community violence and youths’ externalizing (based on the SDQ reported by mother and child, and a child report measure of aggression) and internalizing problems (based on the SDQ measures) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Tests of the conceptual model of the role of children’s emotional security in relations between community violence and child adjustment. SAB sectarian antisocial behavior; NAB nonsectarian antisocial behavior; SDQ Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Standardized path coefficients reported. Error variances omitted from the model. *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

Figure 3.

Testing a social ecological model of relations between political violence and child outcomes. SAB = sectarian antisocial behavior; NAB= nonsectarian antisocial behavior; SDQ = Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Standardized path coefficients are reported. Solid lines denote significant paths; dashed lines indicate nonsignificant paths. *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

Finally, Cummings, Taylor et al. (in press) examined relations between individual trajectories of emotional insecurity about the community over four consecutive years and children’s adjustment in contexts of sectarian community violence. This approach allowed exploration of the within-person development of, or change in, emotional security about the community over time, rather than simply based on a “snap shot” at one point in time (Cummings et al., 2011). Sectarian antisocial behavior served as a time-varying covariate of emotional insecurity, thereby controlling for variations in children’s experience with sectarian antisocial behavior within each time point. Complementing the findings of Cummings et al. (2011), but adding a demonstration of the significance of emotional insecurity over time to adjustment, youths’ trajectories of emotional insecurity about the community were related to risk for developing both internalizing and externalizing problems.

Social Identity Theory

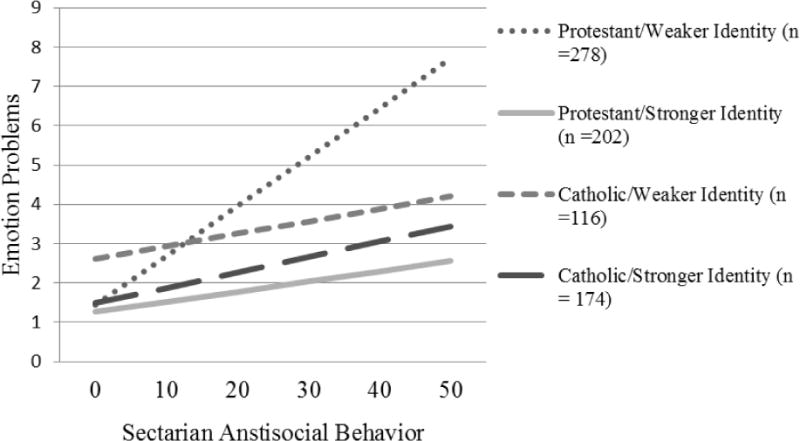

Social identity as reflected in ethnic group identity has long been held pertinent to understanding the impact of contexts of intergroup sectarian conflict (Cairns, 1996). Social identity refers to an individual’s self-categorization as a member of a particular group and the evaluative meaning of that group membership (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Thus, the strength of identification with a group in conflict is likely to alter the psychological experience of group-based conflicts such as the conflict in Northern Ireland. Results support the relevance of social identity to youths’ adjustment in contexts of political violence, although a relatively complex pattern of positive and negative effects are reported (Cummings, Taylor & Merrilees, 2012). Merrilees et al. (2011) reported that the strength of mothers’ social identity moderated pathways between the impact of the political violence and her mental health, with social identity serving as a protective factor for Catholic mothers and a risk factor for Protestant mothers. Based on three waves of data collection, Merrilees et al. (in press-a) reported that youth with higher ethnic group identity reported fewer emotion problems in the face of sectarian antisocial behavior, with this buffering effect stronger for Protestants in relation to Catholics (Figure 4). The moderating effect of social identity observed in these two studies may reflect the changing political context in Belfast in recent years, with Catholics gaining economic and educational achievement relative to Protestants in post-accord Belfast. At the present time, Protestant youth seem more motivated to come together with their in-group members, finding strength in this group membership, whereas Catholics may have possessed greater in-group motivation during the period of the mothers’ youth (i.e., pre-accord Belfast). However, further suggesting the complex pattern of effects associated with ethnic group identity, Merrilees et al. (in press-b) found that in-group social identity weakened relations between exposure to sectarian antisocial behavior and aggressive behaviors. However, youth with higher in-group identity were more likely to aggress against the out-group, with effects stronger for boys than girls. Finally, Merrilees et al. (in press-c) reported evidence for relations between strength of identity and insecurity about the community in late adolescence. Overall, the results of these studies suggest that strength of identity with in-group members can fuel buffering processes through the use of positive social support and pulling together with in-group members. At the same time, strength of identity may act as a risk factor if identification promotes aggressive responses to other group members.

Figure 4.

Three-way Interaction: The Moderating Roles of Ethno-Political Group Membership and Strength of Ethno-political Identity on the Relation between Sectarian Antisocial Behavior and Emotion Problems.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Although the negative effects of political violence on children are well-documented, research has only begun to systematically articulate and test explanatory models for child development in these contexts. This next step is necessary for advances in scientific understanding and, ultimately, stronger bases for effective intervention. The research reviewed advances the merits of a social-ecological process-oriented perspective, focusing on child development processes and trajectories in contexts of political violence. Specifically, the findings support the (a) utility of social ecological models, (b) the value and importance for understanding pathways of influences of differentiating effects attributable to political violence as opposed to other contextual influences, and (c) the promise for greater conceptual understanding of testing theories about specific explanatory processes.

With regard to future directions, children are faced with political violence in many areas of the world but relatively few regions have been subject to systematic study, even fewer at a level of analysis consistent with the empirical standards required by a social-ecological, process-oriented perspective. Commonalities as well as differences are expected to emerge in relations between political violence and child development across contexts of intergroup conflict worldwide (Cummings et al., 2009). Study of many different parts of the world is essential for building an integrated, sophisticated understanding of the processes underlying relations between political violence and child development.

Approaches to understanding relations between political violence and child outcomes at a process-oriented, social ecological level of analysis are still evolving; there are many gaps. Few studies have investigated well-articulated models about the social ecology; even fewer have tested theory-based models about explanatory processes. Only a subset of the elements of the social ecology that may affect children have been identified and studied. Additional theoretical models about mediating processes require articulation and empirical analysis.

Finally, given the well-documented risks for youth, there is an urgent need for more effective interventions. Applied programs based on empirically-supported findings, principles, and theories offer particular potential for more effective interventions. Programs that improve the welfare of children are most likely to emerge if closely informed by high-quality research about pertinent contexts and processes related to youth maladjustment or positive outcomes (Barber, 2013; Masten, 2013; Masten & Narayan, 2012).

Contributor Information

E. Mark Cummings, University of Notre Dame.

Marcie Goeke-Morey, Catholic University of America.

Christine E. Merrilees, State University of New York, Geneseo

Laura K. Taylor, University of North Carolina, Greensboro

Peter A. Shirlow, Queens University, Belfast

References

- Barber BK. Annual research review: The experience of youth with political conflict—Challenging notions of resilience and encouraging research refinement. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54:461–473. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tal D, Jacobson D. A psychological perspective on security. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 1998;47(1):59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Brennan RT, Rubin-Smith J, Fitzmaurice GM, Gilman SE. Sierra Leone’s former child soldiers: A longitudinal study of risk, protective factors and mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:606–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, McBain R, Newnham EA, Brennan RT. Trajectories of internalizing problems in war-affected Sierra Leonean youth: Examining conflict and postconflict factors. Child Development. 2013;84(2):455–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01861.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleich A, Gelkopf M, Solomon Z. Exposure to terrorism, stress-related mental health symptoms, and coping behaviors among a nationally representative sample in Israel. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:612–620. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. A future perspective. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd, Thousand Oaks, CA; 2005. 1979. pp. 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Disruption of affectional bonds and its effects on behavior. Canada’s Mental Health Supplement. 1969;59:12–12. [Google Scholar]

- Boxer P, Huesmann LR, Dubow EF, Landau SF, Gvirsman SD, Shikaki K, Ginges J. Exposure to violence across the social ecosystem and the development of aggression: A test of ecological theory in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Child Development. 2013;84(1):163–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01848.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns E. Children and political violence. Oxford: Blackwell; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns E, Dawes A. Children: Ethnic and political violence—a commentary. Child Development. 1996;67:129–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Marital conflict and children: An emotional security perspective. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press, New York, NY; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Valentino K. Invited chapter prepared for. In: Overton WF, Molenaar Peter CM, editors. Theory and Method Volume 1 of the Handbook of child psychology and developmental science. 7th. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; (in press) Editor-in-Chief: Richard M Lerner. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Schermerhorn AC, Merrilees CE, Cairns E. Children and Political Violence from a Social Ecological Perspective: Implications from Research on Children and Families in Northern Ireland. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2009;12:16–38. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Taylor LK, Merrilees CE. A social ecological perspective on risk and resilience for children and political violence. In: Jonas KJ, Morton T, editors. Restoring civil societies: The psychology of intervention and engagement following crisis. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing; 2012. pp. 78–97. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Merrilees CE, Schermerhorn AC, Goeke-Morey MC, Shirlow P, Cairns E. Testing a social ecological model for relations between political violence and child adjustment in Northern Ireland. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:405–418. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Merrilees CE, Schermerhorn AC, Goeke-Morey MC, Shirlow P, Cairns E. Longitudinal Pathways between Political Violence and Child Adjustment: The Role of Emotional Security about the Community in Northern Ireland. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:213–224. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9457-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Merrilees CE, Taylor LK, Shirlow P, Goeke-Morey M, Cairns E. Longitudinal relations between sectarian and non-sectarian community violence and child adjustment in Northern Ireland. Development and Psychopathology. 2013 doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Merrilees CE, Schermerhorn AC, Goeke-Morey MC, Shirlow P, Cairns E. Political violence and child adjustment: Longitudinal tests of sectarian antisocial behavior, marital conflict and emotional security as explanatory mechanisms. Child Development. 2012;83:461–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01720.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Schermerhorn AC, Merrilees CE, Goeke-Morey MC, Shirlow P, Cairns E. Political violence and child adjustment in Northern Ireland: Testing pathways in a social-ecological model including single-and two-parent families. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:827–841. doi: 10.1037/a0019668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Taylor LK, Merrilees CE, Goeke-Morey MC, Shirlow P, Cairns E. Relations between political violence and child adjustment: A four-wave test of the role of emotional insecurity about community. Developmental Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0032309. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Boxer P, Huesmann LR, Shikaki K, Landau S, Gvirsman SD, Ginges J. Exposure to conflict and violence across contexts: Relations to adjustment among Palestinian children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39(1):103–116. doi: 10.1080/15374410903401153. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15374410903401153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Huesmann LR, Boxer P. A social-cognitive-ecological framework for understanding the impact of exposure to persistent ethnic–political violence on children’s psychosocial adjustment. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2009;12(2):113–126. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0050-7. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10567-009-0050-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings E, Ellis K, Merrilees C, Schermerhorn A, Shirlow P, Cairns E. The differential impact on children of inter- and intra-community violence in Northern Ireland. Journal of Peace Psychology. 2009;15:367–383. doi: 10.1080/10781910903088932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 1997;38:581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten A, Narayan AJ. Child development in the context of disaster, war, and terrorism: Pathways of risk and resilience. Annual Review of Psychology. 2012;63:227–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten A. Society for Research in Child Development. Seattle, WA: 2013. Apr 18, 2013. Global perspectives on resilience in child and youth. [Conference] [Google Scholar]

- McAloney K, McCrystal P, Percy A, McCartan C. Damaged youth: Prevalence of community violence exposure and implications for adolescent well-being in post-conflict Northern Ireland. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;37(5):635–648. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20322. [Google Scholar]

- Merrilees CE, Cairns E, Goeke-Morey MC, Schermerhorn AC, Shirlow P, Cummings EM. Associations between mothers’ experience with the troubles in Northern Ireland and mothers’ and children’s psychological functioning: The moderating role of social identity. Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;39:60–75. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrilees CE, Cairns E, Taylor LK, Goeke-Morey MC, Shirlow P, Cummings EM. Social identity and youth aggressive and delinquent behaviors in a context of political violence. Political Psychology. doi: 10.1111/pops.12030. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrilees CE, Cairns E, Goeke-Morey MC, Shirlow P, Cummings EM. Risk and resilience: The moderating role of social coping for maternal mental health in a setting of political conflict. International Journal of Psychology. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2012.658055. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrilees CE, Taylor LK, Goeke-Morey MC, Shirlow P, Cummings EM. Youth in contexts of political violence: A developmental approach to the study of youth identity and emotional security in their communities. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0035581. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrilees CE, Taylor LK, Goeke-Morey MC, Shirlow P, Cummings EM, Cairns E. The protective role of group identity: Sectarian antisocial behavior and adolescent emotion problems. Child Development. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12125. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qouta S, Punamäki R, Montgomery E, El Sarraj E. Predictors of psychological distress and positive resources among Palestinian adolescents: Trauma, child, and mothering characteristics. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31(7):699–717. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.07.007. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qouta S, Punamäki R, El Sarraj E. Child development and family mental health in war and military violence: The Palestinian experience. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2008;32(4):310–321. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0165025408090973. [Google Scholar]

- Sagi-Schwartz A. The well being of children living in chronic war zones: The Palestinian-Israeli case. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2008;32:322–336. [Google Scholar]

- Sagi-Schwartz A. Children of war and peace: A human development perspective. Journal of Conflict Resolution. 2012;56:933–951. [Google Scholar]

- Shirlow P, Taylor LK, Merrilees CE, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM. Space and Polity. Vol. 17. Taylor LK; 2013. Hate crime: Record or perception? pp. 237–252. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor LK, Merrilees CE, Campbell A, Shirlow P, Cairns E, Goeke-Morey MC, Schermerhorn AC, Cummings EM. Sectarian and nonsectarian violence: Mothers’ appraisals of political conflict in Northern Ireland. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology. 2011;17:343–366. doi: 10.1080/10781919.2011.610199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor LK, Merrilees CE, Goeke-Morey MC, Shirlow P, Cummings EM. Adolescent prosocial behaviors and outgroup attitudes: Implications for positive intergroup relations. Social Development. doi: 10.1111/sode.12074. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]