Abstract

Significant differences in the aberrant methylation of genes exist among various histological types of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which includes adenocarcinoma (AC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Different chemotherapeutic regimens should be administered to the two NSCLC subtypes due to their unique genetic and epigenetic profiles. The purpose of this meta-analysis was to generate a list of differentially methylated genes between AC and SCC. Our meta-analysis encompassed 151 studies on 108 genes among 12946 AC and 10243 SCC patients. Our results showed two hypomethylated genes (CDKN2A and MGMT) and three hypermethylated genes (CDH13, RUNX3 and APC) in ACs compared with SCCs. In addition, our results showed that the pooled specificity and sensitivity values of CDH13 and APC were higher than those of CDKN2A, MGMT and RUNX3. Our findings might provide an alternative method to distinguish between the two NSCLC subtypes.

Introduction

Lung cancer remains the main contributor to cancer-related mortality, with 224,210 new cases and 159,260 deaths in the United States in 2014, although the incidence rate of lung cancer has been declining since the middle of 2000s [1,2]. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), accounting for almost 84% of lung cancer, includes two histological subtypes adenocarcinoma (AC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which stem from epithelial cells that line the larger airways and the peripheral small airways, respectively [2].

Differential diagnosis between AC and SCC is of clinical significance. Chemotherapy regimens for AC and SCC are different according to the guidelines of National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) for NSCLC. For instance, pemetrexed is a multiple-enzyme inhibitor, which is utilized in AC patients rather than in SCC patients [3–5]. The current methods in the differential diagnosis often involve in immunohistochemical stainings of complete surgical resection specimens. The staining proteins consist of AC positive markers (TTF-1, CK7, Muci, and Napsin A) and SCC positive markers (CK5/6, HMWCK, NTRK1/2, and p63) [6]. The sensitivity of the most widely used TTF-1 is only 62%, suggesting a need to develop new markers for the differential diagnosis [6]. Moreover, almost 25% poorly differentiated NSCLC patients cannot be classified by TTF-1, suggesting that complimentary markers are needed to enhance the specificity [7–9].

Epigenetic modifications have been shown to be an important regulatory mechanism during the multistep development of human cancers [10]. Different epigenetic modifications [11] and different microRNA and gene expression profiles were found between AC and SCC [12], suggesting that there were distinct molecular signatures between the two subtypes [13,14]. Several studies have reported that the methylation rates of APC, CDH13, RARβ, LINE-1, RASSF1, and RUNX3 were significantly higher in AC than in SCC [15,16], while higher methylation frequencies of DAPK, TIMP3, TGIF and SFRP4 were more often observed in SCC compared to AC [17,18]. In addition, there were significantly different chemotherapeutic outcomes between AC and SCC [19].

Due to the increasing amount of evidence, it was necessary to establish a short list of methylated genes through a comprehensive literature review. Meta-analysis can overcome the limitation of small-size samples in single study, and achieve more reliable and completed consequences through the combination and quantitative assessment of various studies [20]. In this study, we systematically reviewed the recent methylation studies and summarized the differential gene methylation between AC and SCC, and aimed to provide a handful of epigenetic clues to elaborate the molecular biomarkers of the different histological subtypes of NSCLC.

Materials and Methods

Identification of relevant studies

All the relevant studies, updated until January 11, 2016, were systematically searched for in the PubMed, China National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wanfang literature databases. The keywords were as follows: “(histolog* OR patholog* OR clinic*) AND lung cancer (methylation OR epigene*)”. In addition, a manual search was performed to seek other potential studies in the references of the retrieved publications.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All the eligible studies should meet the following criteria: (1) the study should refer to the measurement of the gene methylation status in NSCLC patients rather than cancer cell lines; (2) the study should have sufficient methylation information on the relative genes; and (3) the study should provide detailed information on NSCLC, such as the pathological subtypes of NSCLC and the number of NSCLC subtypes. In addition, neither reviews nor abstracts were included in our analysis. Studies without detailed information on gene methylation or pathological types of NSCLC data were also excluded from the current study. The current meta-analysis was reported based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement (S1 PRISMA Checklist).

Data extraction

For the eligible studies, we extracted the gene, the first author’s name, the published year, the race of the study subjects, the methylation assessment method, the number of cases of AC and SCC, and the frequency of gene methylation (S1 Table).

Statistical analysis

Review manager 5.2 software (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) was used to calculate the combined odds ratios (ORs) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) to estimate the association in the meta-analysis. χ2 test was used to assess the significant heterogeneity across studies, and the result of χ2 test was expressed by I2 metric. When I2 metric was more than 50%, we considered that obvious heterogeneity existed in the involved studies, and a random-effect model was applied for the meta-analysis. Otherwise, a fixed-effect model was used. The aggregated sensitivity, specificity, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) and their 95% CIs were calculated by STATA software (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX).

Results

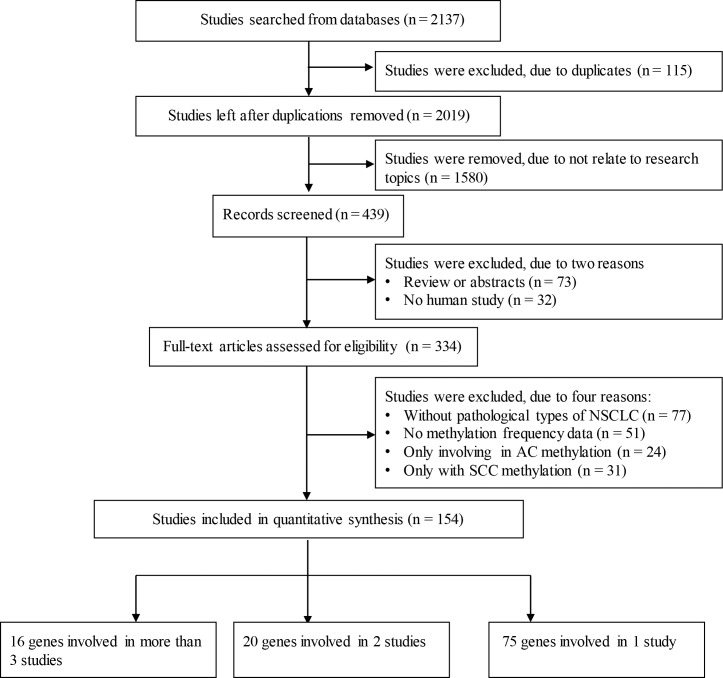

As shown in Fig 1, a total of 2137 articles were initially retrieved from the literature databases. A filtration removed 115 duplicated publications, 1685 studies that were not human studies or full-text inaccessible studies, 77 studies without detailed information regarding pathological types of NSCLC, 51 studies without methylation frequency data, 24 studies only including AC methylation data, and 31 studies only including SCC methylation data as controls. Finally, a total of 154 eligible studies on 111 genes were included in the current meta-analysis. Among the identified genes, there were 75 genes reported by only one study, 20 genes involved in two studies, and 16 genes covered by at least three studies. The 16 genes reported by at least three studies were CDKN2A, RASSF1, MGMT, MLH1, CDH13, CDH1, DAPK, RUNX3, APC, FHIT, SFRP1, RARB, WIF1, DLEC1, IGFBP7 and TFPI2 (Table 1). The genes with fewer than 3 studies were listed in S2 Table.

Fig 1. Flow diagram.

The flow diagram of the stepwise selection from relevant studies.

Table 1. Meta-analyses of 16 gene methylation frequencies between AC and SCC.

| Gene | Studies | Overall OR [95% CI] | I2 | P Value | Median Methylation (AC/SCC, %) | 25% Methylation Quartile (AC/SCC, %) | 50% Methylation Quartile (AC/SCC, %) | 75% Methylation Quartile (AC/SCC, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDH13 | 8 | 2.60 [1.73, 3.90] | 0% | < 0.00001 | 40/25 | 36/19 | 44/25 | 66/36 |

| RUNX3 | 7 | 3.34 [2.10, 5.31] | 35% | < 0.00001 | 36/11 | 27/7 | 36/11 | 41/26 |

| APC | 7 | 2.82 [1.72, 4.62] | 18% | < 0.0001 | 62/37 | 43/30 | 63/37 | 73/57 |

| MGMT | 15 | 0.66 [0.52, 0.82] | 0% | 0.0003 | 32/36 | 29/27 | 32/36 | 40/53 |

| CDKN2A | 40 | 0.75 [0.63, 0.89] | 39% | 0.0008 | 36/49 | 23/33 | 37/49 | 58/57 |

| WIF1 | 4 | 0.67 [0.43, 1.02] | 0% | 0.06 | 32/39 | 8/3 | 25/16 | 35/30 |

| RASSF1 | 19 | 1.15 [0.94, 1.40] | 33% | 0.16 | 39/36 | 14/5 | 17/15 | 26/22 |

| FHIT | 6 | 0.82 [0.57, 1.17] | 25% | 0.27 | 27/31 | 7/10 | 14/18 | 23/29 |

| SFRP1 | 5 | 1.23 [0.81, 1.86] | 0% | 0.33 | 37/31 | 9/4 | 11/10 | 36/19 |

| DLEC1 | 4 | 0.80 [0.42, 1.55] | 53% | 0.51 | 34/40 | 8/16 | 12/19 | 25/31 |

| CDH1 | 8 | 1.06 [0.63, 1.78] | 22% | 0.82 | 39/33 | 4/3 | 5/5 | 13/6 |

| DAPK | 8 | 1.02 [0.69, 1.51] | 0% | 0.92 | 35/36 | 7/6 | 12/9 | 16/12 |

| MLH1 | 9 | 0.98 [0.53, 1.78] | 63% | 0.94 | 57/55 | 6/10 | 11/19 | 33/36 |

| TFPI2 | 3 | 0.99 [0.50, 1.94] | 0% | 0.97 | 26/29 | 2/6 | 15/7 | NA/NA |

| RARB | 5 | 1.00 [0.40, 2.46] | 82% | 0.99 | 50/49 | 7/10 | 32/17 | 45/55 |

| IGFBP7 | 3 | 1.00 [0.50, 2.00] | 0% | 0.99 | 47/47 | 3/1 | 25/4 | NA/NA |

NA stands for not available. From the overall OR values, CDH13, RUNX3 and APC were significantly more methylated in AC than in SCC; MGMT and CDKN2A were significantly less methylated in AC than in SCC.

According to our systematic review, there were 5 aberrantly methylated genes (including CDKN2A, MGMT, CDH13, RUNX3 and APC) associated with the pathological types of NSCLC, and the remaining 11 gene methylation events showed no significant difference between AC and SCC. As shown in Table 1, CDKN2A and MGMT were significantly less methylated in AC rather than in SCC, while CDH13, RUNX3 and APC genes were significantly more methylated in AC than in SCC.

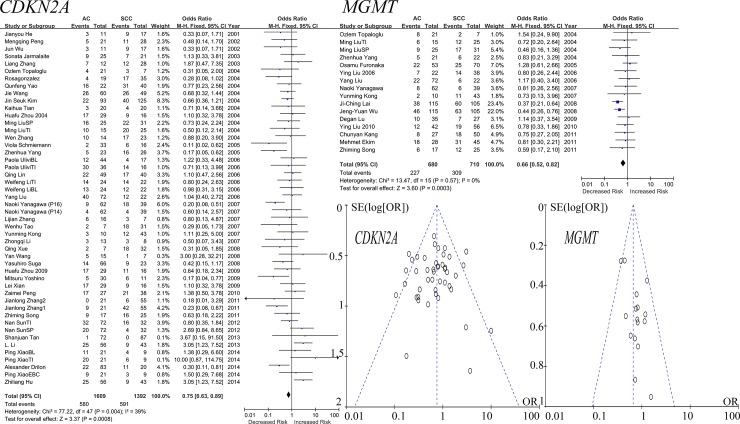

As shown in Fig 2, the meta-analysis of CDKN2A methylation in 40 studies among 1609 ACs and 1392 SCCs revealed that CDKN2A methylation was less frequently observed in AC than in SCC (OR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.63–0.89, P = 0.0008, I2 = 39%). Meta-analysis of 15 studies among 680 ACs and 710 SCCs showed that MGMT was significantly more methylated in SCC than in AC (OR = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.52–0.82, P = 0.0003, I2 = 0%).

Fig 2. Forest and funnel plots of CDKN2A and MGMT.

The forest plots of CDKN2A and MGMT displayed the effect size and 95% CIs for the included studies. Funnel plots suggested no publication bias in the meta-analyses of CDKN2A and MGMT genes. Our results showed that the total ORs for CDKN2A and MGMT were less than1, which demonstrated the methylation of CDKN2A and MGMT in AC were relatively higher than in SCC. Funnel plots of meta-analyses of CDH13, RUNX3 and APC demonstrated no publication biases in the included studies. In addition, M-H denotes Mantel-Haenszel statistical method to calculate the combined odds ratios (ORs) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Weight denotes the weighted average of the intervention effect estimated in each study. SE denotes standard errors.

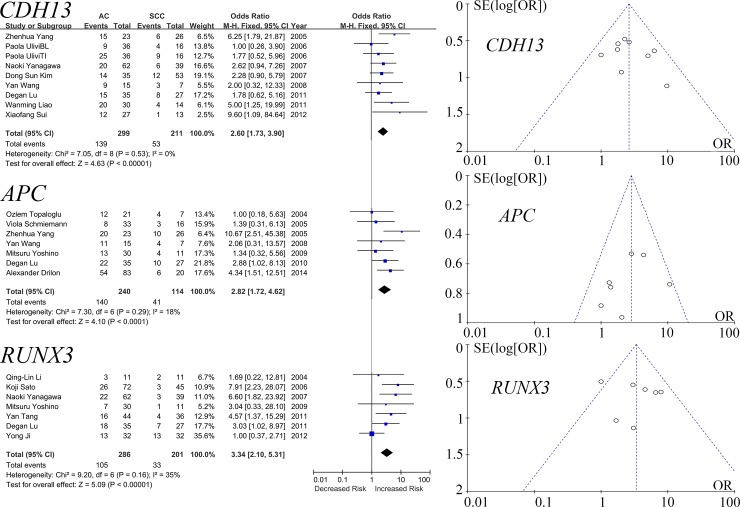

CDH13, RUNX3 and APC genes were shown to have significantly higher methylation frequencies in AC. Specifically, our meta-analysis of 8 studies among 299 ACs and 211 SCCs revealed that CDH13 methylation was more frequently observed in AC than in SCC (OR = 2.60, 95% CI = 1.73–3.90, P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%). Meta-analysis of 7 studies among 286 ACs and 201 SCCs showed that RUNX3 was more often methylated in SCC than in AC (OR = 3.34, 95% CI = 2.10–5.31, P < 0.00001, I2 = 35%). The meta-analysis of APC in 7 studies among 157 ACs and 94 SCCs showed that APC methylation was more often methylated in AC than in SCC (OR = 2.82, 95% CI = 1.72–4.62, P < 0.0001, I2 = 18%, Fig 3).

Fig 3. Forest and funnel plots of CDH13, RUNX3 and APC.

The forest plots of CDH13, RUNX3 and APC displayed the effect size and 95% CIs for the included studies. Our results showed that the total ORs of CDH13, RUNX3 and APC demonstrated that the methylation of CDH13, RUNX3 and APC in AC were significantly more frequent than in SCC. Funnel plots of meta-analyses of CDH13, RUNX3 and APC demonstrated no publication biases in the included studies. The details of abbreviations (M-H, ORs, CIs, and SE) and weight were shown in the legends of Fig 2.

As shown in Table 1, the methylation of 11 genes (including RASSF1, MLH1, CDH1, DAPK, FHIT, SFRP1, RARB, WIF1, DLEC1, IGFBP7 and TFPI2) could not distinguish between AC and SCC. And as demonstrated in Figs 2 and 3, the funnel plots of CDKN2A, MGMT, CDH13, RUNX3 and APC indicated no significant publication bias.

Subsequently, we performed sensitivity meta-analyses of the five significant genes (Table 2). Our results showed that the pooled specificity values as differential diagnostic markers between AC and SCC for CDH13, APC, CDKN2A, MGMT and RUNX3 were 0.74 (0.65–0.81), 0.65 (0.55–0.74), 0.55 (0.47–0.63), 0.60 (0.52–0.68) and 0.86 (0.75–0.92), respectively. The aggregated sensitivity values of CDH13, APC, CDKN2A, MGMT and RUNX3 were 0.49 (0.38–0.59), 0.60 (0.44–0.74), 0.37 (0.29–0.45), 0.32 (0.27–0.37) and 0.47 (0.42–0.51), respectively

Table 2. Specificity and sensitivity of five differentially methylated genes between AC and SCC.

| Gene | Specificity [95% CI] | Sensitivity [95% CI] | AUC [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDH13 | 0.74 [0.65, 0.81] | 0.49 [0.38, 0.59] | 0.68 [0.64, 0.72] |

| APC | 0.65 [0.55, 0.74] | 0.60 [0.44, 0.74] | 0.66 [0.62, 0.70] |

| CDKN2A | 0.55 [0.47, 0.63] | 0.37 [0.29, 0.45] | 0.45 [0.41, 0.49] |

| MGMT | 0.60 [0.52, 0.68] | 0.32 [0.27, 0.37] | 0.40 [0.35, 0.44] |

| RUNX3 | 0.86 [0.75, 0.92] | 0.47 [0.42, 0.51] | 0.47 [0.42, 0.51] |

Discussion

Some chemotherapeutic regimens were more effective in SCC, while other drugs were more effective in non-squamous histological types [3–5]. Thus, it is necessary to differentiate the two major types of NSCLC (AC and SCC). Generally, well-differentiated AC can be identified according to the immunohistochemical staining results of TTF-1, napsin-A, and other markers [6]. However, some studies have reported that a minor fraction of poorly differentiated SCC still reacted with TTF-1 [7–9]. Our results showed that the pooled specificity and sensitivity values of CDH13 and APC were higher than those of CDKN2A, MGMT and RUNX3. The joint effect of these methylation markers is of interest to be explored in the future.

Epigenetic modifications have been shown to account for the mechanisms in the development of different histological subtypes of cancers [21]. Besides, other studies have identified genes with significantly different methylation between different subtypes, and the differentially methylated genes (including CDKN2A, APC, CDH13, THBS2 and ERG) have been utilized to distinguish these different histological subtypes of cancers [22,23]. Previous study has identified that CDKN2A, APC and CDH13 have significantly different methylation frequencies between AC and SCC [23]. Another study observed that RUNX3 methylation was significantly more often in AC than in SCC [15]. The above findings were also confirmed in the current meta-analyses. However, MGMT methylation frequency was not different between 77 AC and 38 SCC in the previous study [23], and this might be due to a lack of power [23]. In contrast, our meta-analyses among 680 ACs and 710 SCCs found MGMT methylation was significantly less in AC than in SCC.

In the current study, we identified five differentially methylated genes between AC and SCC. These five methylated genes could also be found in many other cancers. Loss of CDH13 expression caused by promoter hypermethylation was observed in breast [24], lung [24], colorectal [25,26], prostate [27], and nasopharyngeal [28] cancers. Besides, Methylated CDH13 could serve as a potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in nasopharyngeal carcinoma [28] and cervical cancer [29], respectively. Aberrantly methylated levels of APC and MGMT were also observed in colorectal cancer tissues [30]. Methylated APC was shown to be associated with prognostic outcomes in gastric carcinomas [31], breast cancer [32], and hepatocellular carcinoma [33]. MGMT was a DNA-repair gene, which greatly contributed to the microsatellite instability (MSI) in colorectal cancer [34]. Studies demonstrated that MGMT methylation triggered the incidence of MSI [35,36]. CDKN2A was a well-established gene, which played a critical role in cancer progression [37]. The inactivation of CDKN2A by promoter hypermethylation was observed in leukemia [38], colorectal [39], gastric [40], esophagus [41], and lung cancers [42]. Aberrantly methylated RUNX3 was found to be associated with the risk of multiple cancers, such as hepatocellular carcinoma [43], esophageal cancer [43], gastric carcinoma [44] and NSCLC [44].

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) is known to be an important tumor suppressor gene with regulatory roles affecting CDK4 and p53 in cell cycle G1 control. This gene is frequently mutated or deleted, as well as hypermethylated, in a wide variety of tumors including NSCLC [45–47]. Interestingly, previous studies reported that the methylation status of CDKN2A might correlate with the response to certain chemotherapeutic drugs in breast cancer [48]. Cell line studies demonstrated that the usage of demethylating agents could reactivate CDKN2A, which was able to be silenced by hypermethylation [49]. Other clinical studies reported that NSCLC patients who underwent epigenetic therapy tended to have improved overall survival with statistical significance [46]. Our systematic review concluded that the methylation of CDKN2A was significantly more common in SCC than in AC.

MGMT plays a key role in regulating DNA repair via removing a methyl group from mutagenic O6-methylguanine, which can lead to a transition mutation through DNA replication [50]. Thus, inactivation of the O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) gene plays an important role in the progression of cancer characterized by the accumulation of genetic changes. In addition, the epigenetic silencing of MGMT was shown to play a pivotal role in DNA repair pathway that was associated with cisplatin sensitivity [51]. MGMT promoter methylation was shown to be inversely correlated with MGMT expression, and silenced MGMT by promoter hypermethylation was observed in NSCLC [52]. Our meta-analysis found that the hypermethylation of MGMT was more common in SCC than in AC.

Cadherin 13 (CDH13), also known as T-cadherin or H-cadherin (heart), is a unique member of the cadherin superfamily [53,54]. CDH13 proteins play important roles in cell differentiation and in anti-apoptosis [55]. However, CDH13 expression was generally down regulated by CDH13 promoter hypermethylation in human cancers [56,57]. CDH13 methylation was a common event in NSCLC, and it was also associated with its clinicopathological features. CDH13 hypermethylation was observed at higher frequency in AC than in SCC [23]. Patients with CDH13 hypermethylation tended to have lower survival [58], suggesting that CDH13 hypermethylation could serve as a prognostic biomarker in NSCLC. The current meta-analysis also confirmed this observation.

The RUNX3 proteins belong to the runt domain-containing family of transcription factors in the regulation of gene expression [59]. Transcriptional silencing of RUNX3 by hypermethylation was associated with various human cancers, including NSCLC [60–62]. Low RUNX3 mRNA expression level was found to be associated with RUNX3 promoter hypermethylation [62]. RUNX3 hypermethylation was mostly detected in AC [53]. Further studies demonstrated that patients with higher RUNX3 hypermethylation in AC had shorter survival even when undergoing positive treatment [63]. Our analysis indicated that RUNX3 hypermethylation might have the potential to predict treatment outcome as a differential diagnostic marker for NSCLC subtypes.

The tumor suppressor gene adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) is correlated with inhibition of the Wnt signaling pathway [64]. Mutation of APC was shown to be associated with the emergence of colorectal cancer [65]. Decreased expression of APC by its promoter hypermethylation was also often observed in NSCLC [66]. Aberrant epigenetic modification of APC was also observed in colorectal cancer as well as in NSCLC [66,67]. The current analysis revealed that APC hypermethylation was more frequent in AC than in SCC.

Although our meta-analyses were performed through carefully screening numerous relevant studies, several limitations should not be underestimated. Above all, conference abstracts and inaccessible full-text articles were excluded from our meta-analyses because we were unable to retrieve relevant data for the meta-analysis. Moreover, only reports in the English or Chinese languages were chosen, and this might introduce bias in the literature selection. Meanwhile, the majority of the harvested genes with only one or two studies were excluded from this analysis. It was possible that some of them were certain specific-histology genes. Thus, future analyses of these genes in larger sample sizes were needed to confirm our findings.

In summary, our meta-analysis provided a list of differently methylated genes between AC and SCC and identified two hypomethylated (CDKN2A and MGMT) and three hypermethylated genes (CDH13, RUNX3 and APC) that might help distinguish between AC and SCC.

Supporting Information

(DOCX)

(DOC)

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31100919 and 81371469), the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LR13H020003), the K. C. Wong Magna Fund in Ningbo University, the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LY16H160005), Project of Scientific Innovation Team of Ningbo (2015B11050) and the Ningbo Natural Science Foundation (2014A610235). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The research was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31100919 and 81371469), the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LR13H020003), the K. C. Wong Magna Fund in Ningbo University, the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LY16H160005), Project of Scientific Innovation Team of Ningbo (2015B11050) and the Ningbo Natural Science Foundation (2014A610235). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2014;64(1):9–29. 10.3322/caac.21208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.America Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2014. American Cancer Society. 2014. Available: http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancerfactsfigures2014/index

- 3.Hirsch FR, Spreafico A, Novello S, Wood MD, Simms L, Papotti M. The prognostic and predictive role of histology in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a literature review. Journal of thoracic oncology: official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2008;3(12):1468–81. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318189f551 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scagliotti G, Brodowicz T, Shepherd FA, Zielinski C, Vansteenkiste J, Manegold C, et al. Treatment-by-histology interaction analyses in three phase III trials show superiority of pemetrexed in nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of thoracic oncology: official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2011;6(1):64–70. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f7c6d4 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scagliotti G, Hanna N, Fossella F, Sugarman K, Blatter J, Peterson P, et al. The differential efficacy of pemetrexed according to NSCLC histology: a review of two Phase III studies. The oncologist. 2009;14(3):253–63. 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0232 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terry J, Leung S, Laskin J, Leslie KO, Gown AM, Ionescu DN. Optimal immunohistochemical markers for distinguishing lung adenocarcinomas from squamous cell carcinomas in small tumor samples. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(12):1805–11. 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181f7dae3 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fabbro D, Di Loreto C, Stamerra O, Beltrami CA, Lonigro R, Damante G. TTF-1 gene expression in human lung tumours. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A(3):512–7. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pelosi G, Fraggetta F, Pasini F, Maisonneuve P, Sonzogni A, Iannucci A, et al. Immunoreactivity for thyroid transcription factor-1 in stage I non-small cell carcinomas of the lung. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(3):363–72. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan D, Li Q, Deeb G, Ramnath N, Slocum HK, Brooks J, et al. Thyroid transcription factor-1 expression prevalence and its clinical implications in non-small cell lung cancer: a high-throughput tissue microarray and immunohistochemistry study. Hum Pathol. 2003;34(6):597–604. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feinberg AP, Ohlsson R, Henikoff S. The epigenetic progenitor origin of human cancer. Nature reviews Genetics. 2006;7(1):21–33. 10.1038/nrg1748 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J, Yang XY, Shi WJ. Identifying differentially expressed genes and pathways in two types of non-small cell lung cancer: adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Genetics and molecular research: GMR. 2014;13(1):95–102. 10.4238/2014.January.8.8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsiung CA, Lan Q, Hong YC, Chen CJ, Hosgood HD, Chang IS, et al. The 5p15.33 locus is associated with risk of lung adenocarcinoma in never-smoking females in Asia. PLoS genetics. 2010;6(8). 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daraselia N, Wang Y, Budoff A, Lituev A, Potapova O, Vansant G, et al. Molecular signature and pathway analysis of human primary squamous and adenocarcinoma lung cancers. American journal of cancer research. 2012;2(1):93–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lockwood WW, Wilson IM, Coe BP, Chari R, Pikor LA, Thu KL, et al. Divergent genomic and epigenomic landscapes of lung cancer subtypes underscore the selection of different oncogenic pathways during tumor development. PloS one. 2012;7(5):e37775 10.1371/journal.pone.0037775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin M, Kawakami K, Fukui Y, Tsukioka S, Oda M, Watanabe G, et al. Different histological types of non-small cell lung cancer have distinct folate and DNA methylation levels. Cancer science. 2009;100(12):2325–30. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01321.x . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toyooka S, Maruyama R, Toyooka KO, McLerran D, Feng Z, Fukuyama Y, et al. Smoke exposure, histologic type and geography-related differences in the methylation profiles of non-small cell lung cancer. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2003;103(2):153–60. 10.1002/ijc.10787 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castro M, Grau L, Puerta P, Gimenez L, Venditti J, Quadrelli S, et al. Multiplexed methylation profiles of tumor suppressor genes and clinical outcome in lung cancer. Journal of translational medicine. 2010;8:86 10.1186/1479-5876-8-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niklinska W, Naumnik W, Sulewska A, Kozlowski M, Pankiewicz W, Milewski R. Prognostic significance of DAPK and RASSF1A promoter hypermethylation in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Folia histochemica et cytobiologica / Polish Academy of Sciences, Polish Histochemical and Cytochemical Society. 2009;47(2):275–80. 10.2478/v10042-009-0091-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hou J, Aerts J, den Hamer B, van Ijcken W, den Bakker M, Riegman P, et al. Gene expression-based classification of non-small cell lung carcinomas and survival prediction. PloS one. 2010;5(4):e10312 10.1371/journal.pone.0010312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical meta-analysis Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 2001. ix, 247 p. p. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feinberg AP. Epigenetics at the epicenter of modern medicine. Jama. 2008;299(11):1345–50. 10.1001/jama.299.11.1345 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelemen LE, Kobel M, Chan A, Taghaddos S, Dinu I. Differentially methylated loci distinguish ovarian carcinoma histological types: evaluation of a DNA methylation assay in FFPE tissue. BioMed research international. 2013;2013:815894 10.1155/2013/815894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toyooka S, Toyooka KO, Maruyama R, Virmani AK, Girard L, Miyajima K, et al. DNA methylation profiles of lung tumors. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2001;1(1):61–7. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toyooka KO, Toyooka S, Virmani AK, Sathyanarayana UG, Euhus DM, Gilcrease M, et al. Loss of expression and aberrant methylation of the CDH13 (H-cadherin) gene in breast and lung carcinomas. Cancer research. 2001;61(11):4556–60. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hibi K, Nakayama H, Kodera Y, Ito K, Akiyama S, Nakao A. CDH13 promoter region is specifically methylated in poorly differentiated colorectal cancer. British journal of cancer. 2004;90(5):1030–3. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toyooka S, Toyooka KO, Harada K, Miyajima K, Makarla P, Sathyanarayana UG, et al. Aberrant methylation of the CDH13 (H-cadherin) promoter region in colorectal cancers and adenomas. Cancer research. 2002;62(12):3382–6. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maruyama R, Toyooka S, Toyooka KO, Virmani AK, Zochbauer-Muller S, Farinas AJ, et al. Aberrant promoter methylation profile of prostate cancers and its relationship to clinicopathological features. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2002;8(2):514–9. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun D, Zhang Z, Van do N, Huang G, Ernberg I, Hu L. Aberrant methylation of CDH13 gene in nasopharyngeal carcinoma could serve as a potential diagnostic biomarker. Oral oncology. 2007;43(1):82–7. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.01.007 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Widschwendter A, Ivarsson L, Blassnig A, Muller HM, Fiegl H, Wiedemair A, et al. CDH1 and CDH13 methylation in serum is an independent prognostic marker in cervical cancer patients. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2004;109(2):163–6. 10.1002/ijc.11706 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michailidi C, Theocharis S, Tsourouflis G, Pletsa V, Kouraklis G, Patsouris E, et al. Expression and promoter methylation status of hMLH1, MGMT, APC, and CDH1 genes in patients with colon adenocarcinoma. Experimental biology and medicine. 2015;240(12):1599–605. 10.1177/1535370215583800 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balgkouranidou I, Matthaios D, Karayiannakis A, Bolanaki H, Michailidis P, Xenidis N, et al. Prognostic role of APC and RASSF1A promoter methylation status in cell free circulating DNA of operable gastric cancer patients. Mutation research. 2015;778:46–51. 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2015.05.002 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muller HM, Widschwendter A, Fiegl H, Ivarsson L, Goebel G, Perkmann E, et al. DNA methylation in serum of breast cancer patients: an independent prognostic marker. Cancer research. 2003;63(22):7641–5. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calvisi DF, Ladu S, Gorden A, Farina M, Lee JS, Conner EA, et al. Mechanistic and prognostic significance of aberrant methylation in the molecular pathogenesis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117(9):2713–22. 10.1172/JCI31457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kohonen-Corish MR, Daniel JJ, Chan C, Lin BP, Kwun SY, Dent OF, et al. Low microsatellite instability is associated with poor prognosis in stage C colon cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(10):2318–24. 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.109 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ogino S, Hazra A, Tranah GJ, Kirkner GJ, Kawasaki T, Nosho K, et al. MGMT germline polymorphism is associated with somatic MGMT promoter methylation and gene silencing in colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28(9):1985–90. 10.1093/carcin/bgm160 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitehall VL, Walsh MD, Young J, Leggett BA, Jass JR. Methylation of O-6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase characterizes a subset of colorectal cancer with low-level DNA microsatellite instability. Cancer research. 2001;61(3):827–30. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foulkes WD, Flanders TY, Pollock PM, Hayward NK. The CDKN2A (p16) gene and human cancer. Molecular medicine. 1997;3(1):5–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nosaka K, Maeda M, Tamiya S, Sakai T, Mitsuya H, Matsuoka M. Increasing methylation of the CDKN2A gene is associated with the progression of adult T-cell leukemia. Cancer research. 2000;60(4):1043–8. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shima K, Nosho K, Baba Y, Cantor M, Meyerhardt JA, Giovannucci EL, et al. Prognostic significance of CDKN2A (p16) promoter methylation and loss of expression in 902 colorectal cancers: Cohort study and literature review. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2011;128(5):1080–94. 10.1002/ijc.25432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng D, Zhang H, Sun G. The relationship between P16 gene promoter methylation and gastric cancer: a meta-analysis based on Chinese patients. Journal of cancer research and therapeutics. 2014;10 Suppl:292–5. 10.4103/0973-1482.151535 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bian YS, Osterheld MC, Fontolliet C, Bosman FT, Benhattar J. p16 inactivation by methylation of the CDKN2A promoter occurs early during neoplastic progression in Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(4):1113–21. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan EC, Lam SY, Fu KH, Kwong YL. Polymorphisms of the GSTM1, GSTP1, MPO, XRCC1, and NQO1 genes in Chinese patients with non-small cell lung cancers: relationship with aberrant promoter methylation of the CDKN2A and RARB genes. Cancer genetics and cytogenetics. 2005;162(1):10–20. 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2005.03.008 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang X, He H, Zhang X, Guo W, Wang Y. RUNX3 Promoter Methylation Is Associated with Hepatocellular Carcinoma Risk: A Meta-Analysis. Cancer investigation. 2015;33(4):121–5. 10.3109/07357907.2014.1003934 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hong H, Zhou K, Fu P, Huang Q, Wang J, Yuan X, et al. [Relationship between promoter methylation of Syk and Runx3 genes and postoperative recurrence and metastasis in gastric carcinoma]. Zhonghua zhong liu za zhi [Chinese journal of oncology]. 2014;36(5):341–5. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Belinsky SA. Gene-promoter hypermethylation as a biomarker in lung cancer. Nature reviews Cancer. 2004;4(9):707–17. 10.1038/nrc1432 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Juergens RA, Wrangle J, Vendetti FP, Murphy SC, Zhao M, Coleman B, et al. Combination epigenetic therapy has efficacy in patients with refractory advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer discovery. 2011;1(7):598–607. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Narayan G, Arias-Pulido H, Koul S, Vargas H, Zhang FF, Villella J, et al. Frequent promoter methylation of CDH1, DAPK, RARB, and HIC1 genes in carcinoma of cervix uteri: its relationship to clinical outcome. Molecular cancer. 2003;2:24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klajic J, Busato F, Edvardsen H, Touleimat N, Fleischer T, Bukholm I, et al. DNA methylation status of key cell-cycle regulators such as CDKNA2/p16 and CCNA1 correlates with treatment response to doxorubicin and 5-fluorouracil in locally advanced breast tumors. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2014;20(24):6357–66. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0297 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu WG, Dai Z, Ding H, Srinivasan K, Hall J, Duan W, et al. Increased expression of unmethylated CDKN2D by 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine in human lung cancer cells. Oncogene. 2001;20(53):7787–96. 10.1038/sj.onc.1204970 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soejima H, Zhao W, Mukai T. Epigenetic silencing of the MGMT gene in cancer. Biochemistry and cell biology = Biochimie et biologie cellulaire. 2005;83(4):429–37. 10.1139/o05-140 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosell R, Taron M, Ariza A, Barnadas A, Mate JL, Reguart N, et al. Molecular predictors of response to chemotherapy in lung cancer. Seminars in oncology. 2004;31(1 Suppl 1):20–7. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Esteller M, Hamilton SR, Burger PC, Baylin SB, Herman JG. Inactivation of the DNA repair gene O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase by promoter hypermethylation is a common event in primary human neoplasia. Cancer research. 1999;59(4):793–7. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Angst BD, Marcozzi C, Magee AI. The cadherin superfamily: diversity in form and function. Journal of cell science. 2001;114(Pt 4):629–41. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takeuchi T, Ohtsuki Y. Recent progress in T-cadherin (CDH13, H-cadherin) research. Histology and histopathology. 2001;16(4):1287–93. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rubina K, Kalinina N, Potekhina A, Efimenko A, Semina E, Poliakov A, et al. T-cadherin suppresses angiogenesis in vivo by inhibiting migration of endothelial cells. Angiogenesis. 2007;10(3):183–95. 10.1007/s10456-007-9072-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chan DW, Lee JM, Chan PC, Ng IO. Genetic and epigenetic inactivation of T-cadherin in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2008;123(5):1043–52. 10.1002/ijc.23634 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ren JZ, Huo JR. Correlation between T-cadherin gene expression and aberrant methylation of T-cadherin promoter in human colon carcinoma cells. Med Oncol. 2012;29(2):915–8. 10.1007/s12032-011-9836-9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xue R, Yang C, Zhao F, Li D. Prognostic significance of CDH13 hypermethylation and mRNA in NSCLC. OncoTargets and therapy. 2014;7:1987–96. 10.2147/OTT.S67355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bangsow C, Rubins N, Glusman G, Bernstein Y, Negreanu V, Goldenberg D, et al. The RUNX3 gene—sequence, structure and regulated expression. Gene. 2001;279(2):221–32. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim TY, Lee HJ, Hwang KS, Lee M, Kim JW, Bang YJ, et al. Methylation of RUNX3 in various types of human cancers and premalignant stages of gastric carcinoma. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 2004;84(4):479–84. 10.1038/labinvest.3700060 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim WJ, Kim EJ, Jeong P, Quan C, Kim J, Li QL, et al. RUNX3 inactivation by point mutations and aberrant DNA methylation in bladder tumors. Cancer research. 2005;65(20):9347–54. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1647 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li QL, Kim HR, Kim WJ, Choi JK, Lee YH, Kim HM, et al. Transcriptional silencing of the RUNX3 gene by CpG hypermethylation is associated with lung cancer. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2004;314(1):223–8. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yanagawa N, Tamura G, Oizumi H, Kanauchi N, Endoh M, Sadahiro M, et al. Promoter hypermethylation of RASSF1A and RUNX3 genes as an independent prognostic prediction marker in surgically resected non-small cell lung cancers. Lung cancer. 2007;58(1):131–8. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.05.011 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Groden J, Thliveris A, Samowitz W, Carlson M, Gelbert L, Albertsen H, et al. Identification and characterization of the familial adenomatous polyposis coli gene. Cell. 1991;66(3):589–600. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miyaki M, Konishi M, Kikuchi-Yanoshita R, Enomoto M, Igari T, Tanaka K, et al. Characteristics of somatic mutation of the adenomatous polyposis coli gene in colorectal tumors. Cancer research. 1994;54(11):3011–20. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Esteller M, Sparks A, Toyota M, Sanchez-Cespedes M, Capella G, Peinado MA, et al. Analysis of adenomatous polyposis coli promoter hypermethylation in human cancer. Cancer research. 2000;60(16):4366–71. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Usadel H, Brabender J, Danenberg KD, Jeronimo C, Harden S, Engles J, et al. Quantitative adenomatous polyposis coli promoter methylation analysis in tumor tissue, serum, and plasma DNA of patients with lung cancer. Cancer research. 2002;62(2):371–5. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOC)

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.