Abstract

We investigated by computational means the kinetics and stationary behavior of stochastic dynamics on an ensemble of rough two-dimensional energy landscapes. There are no obvious separations of temporal scales in these systems, which constitute a simple model for the behavior of glasses and some biomaterials. Even though there are significant computational challenges present in these systems due to the large number of metastable states, the Milestoning method is able to compute their kinetic and thermodynamic properties exactly. We observe two clearly distinguished regimes in the overall kinetics: one in which diffusive behavior dominates and another that follows an Arrhenius law (despite the absence of a dominant barrier). We compare our results with those obtained with an exactly-solvable one-dimensional model, and with the results from the rough one-dimensional energy model introduced by Zwanzig.

Keywords: Molecular Dynamics, Ergodicity, Glasses, Milestoning, First passage times

INTRODUCTION

Molecular Dynamics is a useful tool in the study of molecular systems in the condensed phases. Typically a single trajectory is computed according to deterministic or stochastic rules and samples of conformations are extracted from this trajectory. The samples are used to estimate averages of equilibrium or kinetic observables. For example, let A be an observable of interest. We write the time average of A over a long-running trajectory, x(t), as

This average, if x(t) is obtained under conditions of constant number of particles, temperature and volume, and if the system is ergodic, is equal to the canonical spatial average

| (1) |

The integral in (1) is typically high dimensional, which makes it difficult to compute it numerically. In moderate and high dimensional systems, trajectories or Markov chains are methods of choice for estimating thermodynamic averages. If sampled from the correct distribution function, the errors in the average will be of order L−1/2 as L → ∞, where L is the number of sampled points. Markov chains, by sampling from the correct distribution, avoid the need for exhaustive examination of the entire conformational space, which would be the procedure taken by straightforward quadrature schemes to approximate (1).

Despite the popularity of trajectories in the computation of averages, significant challenges remain. It is hard to prove that the system is indeed ergodic. In some cases we know with certainty that a large free energy barrier separates two thermodynamically-accessible basins and a single uninterrupted trajectory cannot provide accurate averages. The probability of observing transitions between the two basins, which are necessary to estimate the relative weights of the basins, is too low to be accurately estimated during the time-scales accessible using a single or a few trajectories.

To overcome the possible lack of ergodicity in the single trajectory approach, a number of techniques have been invented. The present manuscript is too short to review them in detail. We only mention the umbrella sampling approach23, and the free energy perturbation method10 as early techniques that profoundly influenced the field. Both approaches work in a reduced space of coarse variables —variables that are assumed to capture the essential characteristics of the process of interest—. In the extreme case, the coarse space is a single reaction coordinate. The umbrella sampling and the free energy perturbation approach are based on forcing the system to be in energetically unfavorable positions in coarse space by adding a biasing potential (umbrella sampling) or holonomic constraints (free energy perturbation11). As a result, and by construction, the unfavorable high-energy domains are sampled efficiently. The weight of the sampled configurations obtained with the bias requires a correction.

The above extremely useful approaches have some limitations. First, a choice of coarse variables must be made in advance and if the choice is inadequate, the sampling will not give good approximations to (1). For example, we may miss other degrees of freedom that require passage over significant barriers to sample accessible basins. Second, the use of biases limits the study to equilibrium phenomena. At present, it is not known how to study exact kinetics (i.e., without making additional simplifying approximations) using sampling with biasing potentials or constraints. Markov State Models27 (MSMs) are another approach that similarly to Milestoning partitions the space into cells. They constitute another important method to study kinetics however, except for a particular variant26, MSMs are not directly related to Milestoning and are not exact.

Coarse-graining is a promising direction for obtaining long time dynamics using free energy landscapes computed by umbrella sampling or free energy perturbation. These coarse-graining approaches reduce the number of degrees of freedom and speed up computations of kinetic properties. However, to rigorously study kinetics, it is necessary to compute memory functions12, a non-trivial task that is not feasible for many systems. Typically, significant approximations to the memory kernels (like assuming a constant friction and white noise) must be introduced. These approximations reproduce the correct equilibrium but they are only a model of the exact dynamics and cannot be used at all time scales. Time scales (and not the inclination to the most stable products) determine the occurrence of many cellular phenomena.

The above complications for the widely used enhanced sampling techniques are especially problematic on rough energy landscapes on which no obvious transition states are known, or a small number of coarse variables is insufficient to describe the kinetics and thermodynamics of the system. This is the typical case in glassy systems in which no separation of time scales is apparent, and the choice of coarse variables —even if possible— is far from obvious and may defy intuition. The challenges with rough energy landscapes go beyond computational efficiency. It is not clear that the rate coefficients are indeed constant (the kinetics may not be exponential in time). It is not obvious that Arrhenius dependence of the rate coefficient on the temperature is valid for these systems. These interesting questions can be investigated with the method of Milestoning, as we illustrate in the present manuscript. The method of Milestoning was first introduced in13 and has been recently extended7 to provide an exact theory.

In Milestoning, we use a large number of short trajectories to explore kinetics and thermodynamics instead of a single long trajectory typical of straightforward Molecular Dynamics. The advantages of using short trajectories are easy to understand: they are much easier to run in parallel, since individual trajectories can be computed independently, and each of the trajectories is not required to cover all phase space. Instead, these trajectories can be run more efficiently by carefully selecting initial conditions, and propagating them forward in time until they are terminated. The challenges in using short trajectories are the determination of the appropriate initial conditions and the rigorous combination of the results of many short runs to estimate the exact kinetics and thermodynamics. Often times, the number of trajectories required exceeds hundreds of thousands.

Milestoning solves these challenges in a two-step process. First, a partition of space into cells must be provided. Such cells are chosen to be small enough so that they can be effectively covered with short trajectories. Then, trajectories between boundaries of the cells, called milestones, are computed. These short trajectories are initiated at one boundary and propagated in time until they hit for the first time another boundary (milestone). The Milestoning theory allows the determination of mean first passage times and stationary probabilities from the sampled trajectories. This theory has been discussed extensively in the literature7,14 and is briefly summarized in the Methodology section. Note that the exact variant of Milestoning, as introduced in7, is used in this work.

Because the present manuscript does not deal with the partition of space into the aforementioned cells and takes the partition as given, we briefly discuss below how such partitions are obtained in practice for a real molecular system15–17. We first construct a sparse sampling of space that consists of a set of configurations (in full or coarse space), which we call anchors that must cover (albeit sparsely) the relevant landscape. Anchors can be extracted using a number of approaches. For example using Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics18, or even simpler, taking configurations obtained through Molecular Dynamics at high temperature. We note that this sampling process does not need to provide configurations with correct weights. The requirement is that the anchors should yield a kinetically-connected representation of the phase space. Generating this set is, in many cases, the greatest challenge to applying Milestoning in a completely automated fashion, because an input from the user is often required. So, while the use of the set of anchors (without necessarily a reference to coarse variables or to metastable states) is more general than the use of one or a few reaction coordinates, there are still challenges in optimally choosing the anchors.

Once a set of anchors is at hand (we have employed up to ~1,000 conformations in previous studies), we use them as the defining sites of a Voronoi tessellation that partitions the space into cells. A point in space is said to belong to a certain cell (which is in turn defined by a particular anchor) if the distance between the point and the anchor defining the cell is smaller than the distance between the point and any other anchor.

In terms of anchors, we define a milestone as the surface consisting of the points that are equidistant from two different anchors. It has been proposed19 that iso-committor surfaces should be used as milestones. These surfaces are optimal for one-dimensional reaction coordinates and overdamped systems but are difficult to compute in higher dimensions. In Milestoning, we compute short trajectories initiated at an initial milestone until they hit for the first time a different milestone. We repeat the sampling of short trajectories for all milestones. Because the cells bounded by the milestones can be chosen to be small in size (by generating more anchors), the trajectories are typically short (picoseconds) and can be trivially run in parallel. Furthermore, we can place the anchors (and, hence, the milestones) in positions that enhance the sampling of rare events, similarly to the free energy perturbation or thermodynamic integration approaches to the calculations of the potential of mean force10,11. The Milestoning approach provides both the kinetics and the thermodynamics of the system, as was discussed extensively in the literature and summarized in the Methodology section.

In this manuscript, we use Milestoning to study stochastic dynamics on a model of a corrugated potential surface in two dimensions. We report the thermodynamics and the kinetics for this two-dimensional rough energy landscape for which no obvious separation of temporal scales exists. We also investigate the temperature dependence of the kinetics and the thermodynamics.

METHODOLOGY

The energy landscape

We consider a two dimensional energy landscape determined by the potential energy function U(x1, x2). A point on this landscape is denoted by x = (x1, x2) with 0 ≤ x1, x2 < L and the potential energy satisfies U(x1, x2) = U(x1 + nL, x2 + mL) for all integers n, m. In other words, the conformational space of our system is the square Ω = [0, L) × [0, L) with periodic boundary conditions. Hence, the thermodynamics and kinetics of the system are fully characterized once a model for the dynamics (e.g., Newtonian, Langevin, etc.) is chosen. We model rough energy landscapes by truncated Fourier series of the form:

| (2) |

where Re denotes the real part of a complex number and N is the maximum allowed frequency (and ruggedness) of the potential. The constant zk1,k2 = ak1,k2 + i bk1,k2 ∈ ℂ is determined by the random variables ak1,k2, bk1,k2 distributed according to

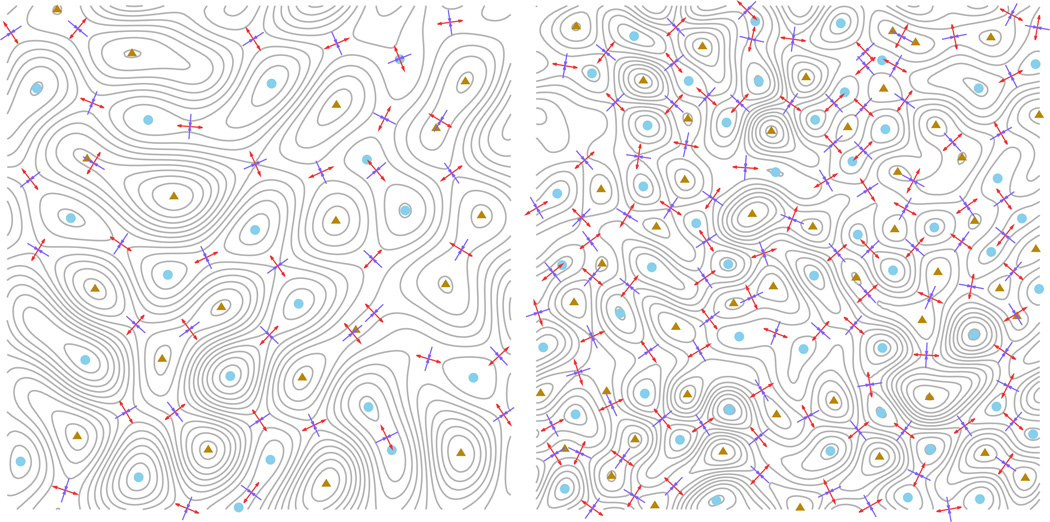

with c itself being a uniform random variable in the interval (−A, A). The value of A is the maximum amplitude of the terms in the trigonometric polynomial (2). Once the maximum frequency and the coefficients of the potential are sampled from their distribution at the beginning of a simulation, they remain fixed throughout the calculation of the kinetics and thermodynamics of this particular energy landscape. In Figure 1 we show some examples of particular realizations of these random energy landscapes.

Figure 1.

Contour plots of two different realizations of the energy landscapes discussed in the paper for N = 4 (left) and N = 7 (right). The blue circles are minima, the brown triangles are maxima, and the blue/red arrows cross at saddle points.

The maximum allowed frequency N is directly tied to the number of non-degenerate critical points (maxima, minima, and saddle points) in the landscape. The statistics gathered by analyzing more than 5 × 104 energy landscapes reveal that the number of local minima depends linearly on the maximum allowed frequency for N = 4, 5, 6, 7 (see Table 1). Since our conformational space (i.e., the square of side L with periodic boundary conditions) is equivalent to a torus, the number of saddle points in our model system is twice the number of minima3.

Table 1.

Average number of local minima, n0, as a function of the maximum frequency, N.

| N | n0 |

|---|---|

| 4 | 16.97 |

| 5 | 25.498 |

| 6 | 35.96 |

| 7 | 47.826 |

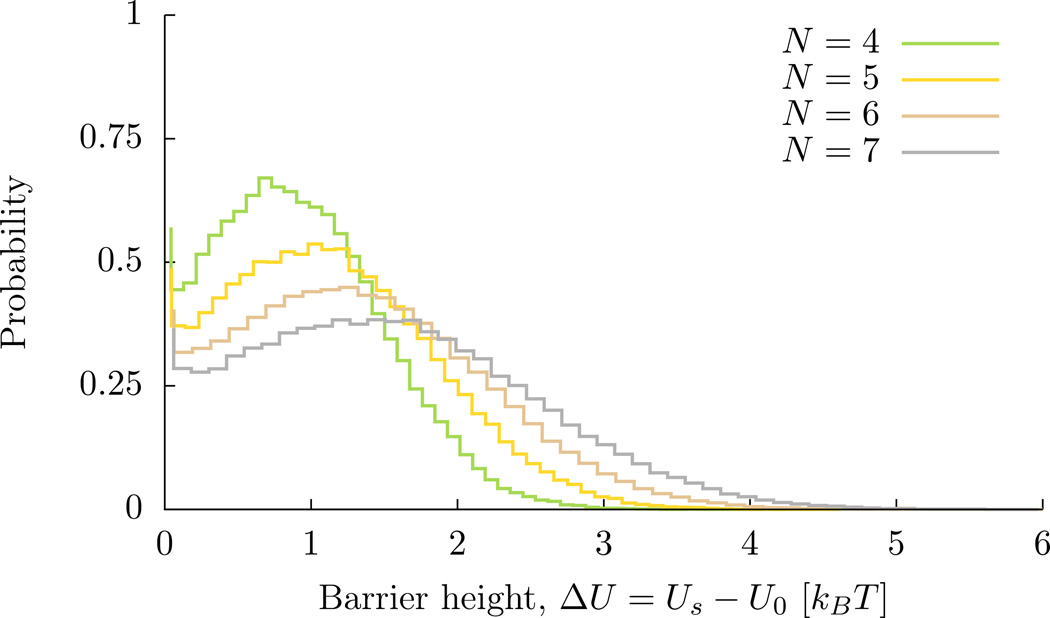

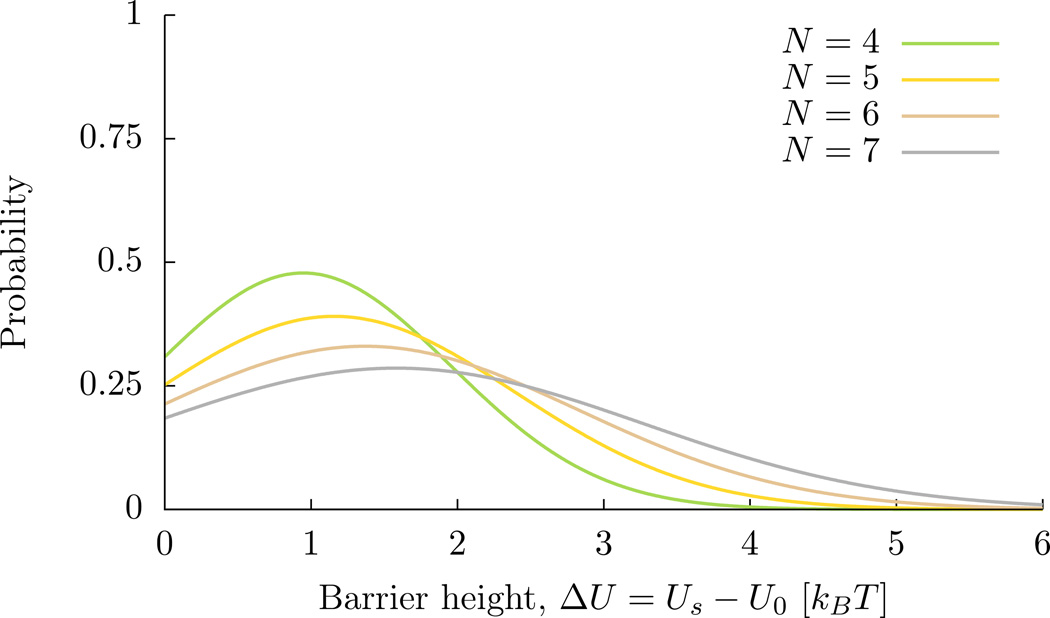

A barrier height is defined as the difference between the energy of a saddle point and the energy of a local minimum that is connected to the saddle point. The empirical distribution of barrier heights for the energy landscapes under consideration is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The distribution of barrier heights, ΔU, on the rough energy landscapes. Note the differences in the distribution for different values of the maximum frequency N.

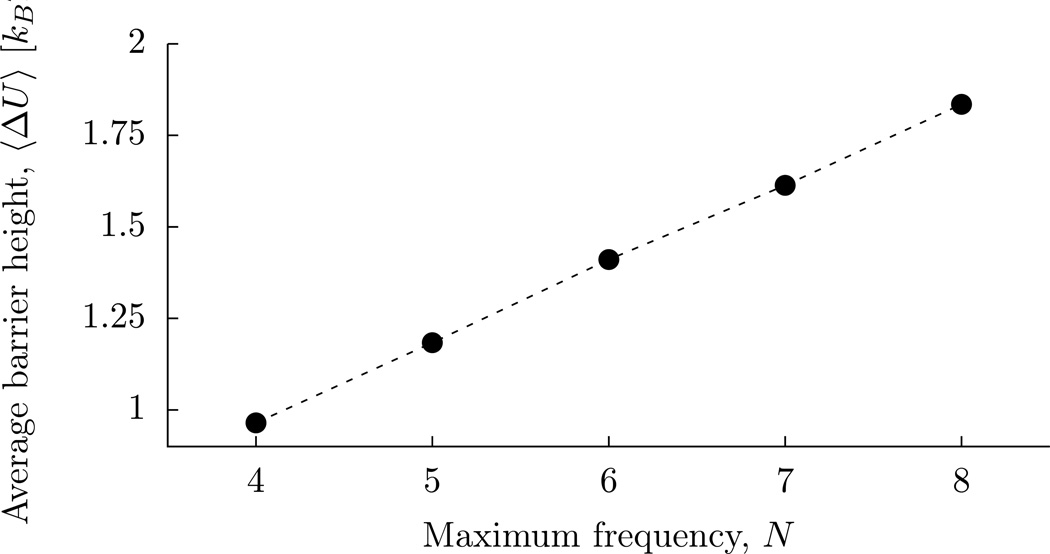

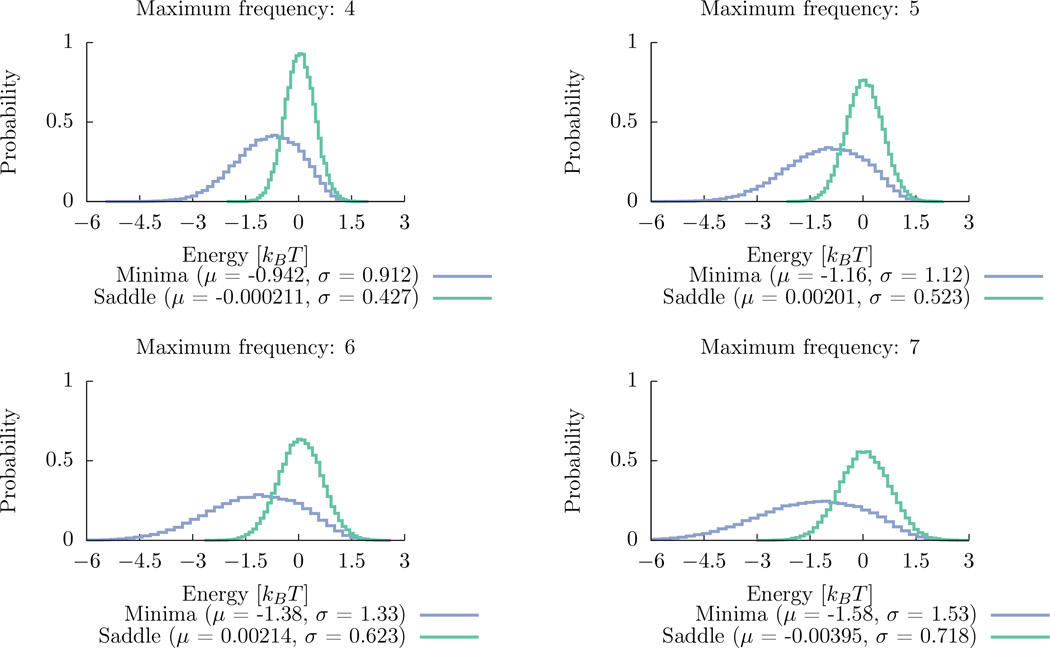

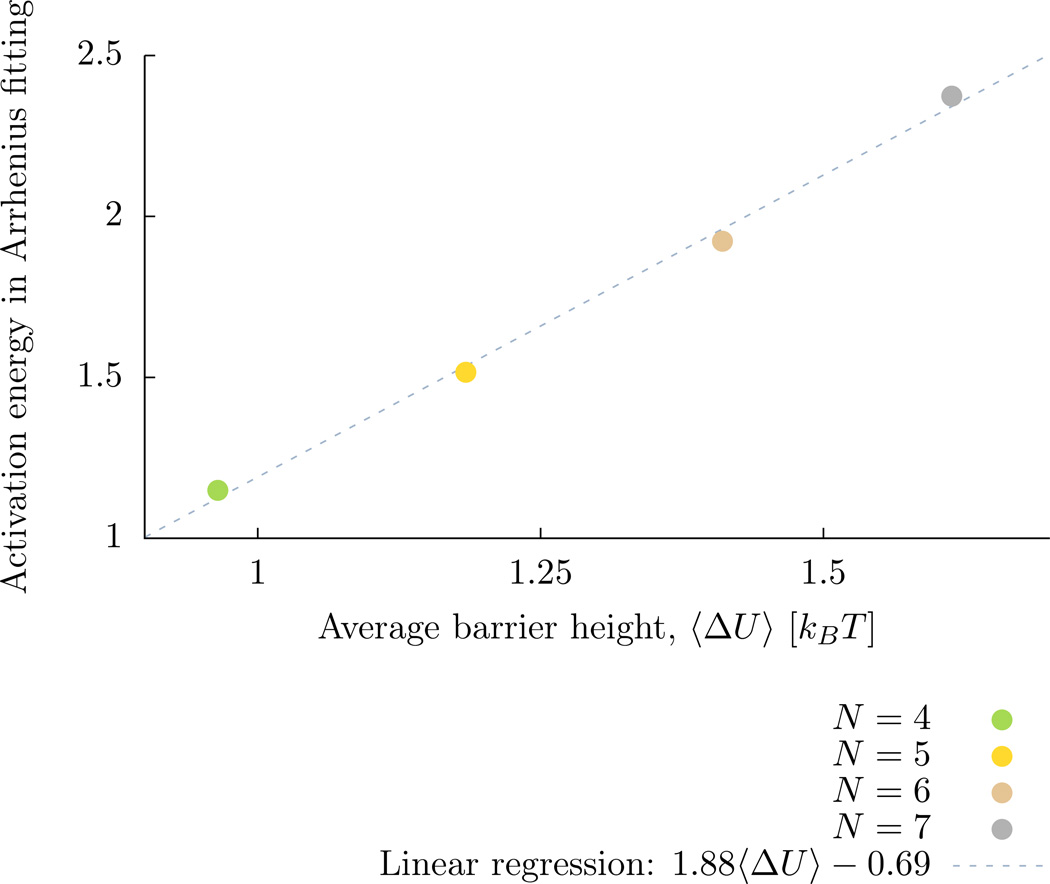

The average barrier height is a linear function of the frequency N, as illustrated in Figure 3. The linear dependence of the average barrier height on the frequency can be understood when we examine the absolute energies of the minima and the saddle points. As illustrated in Figure 4, both the minimum and the saddle point energies are approximately Gaussian.

Figure 3.

The average barrier height, 〈ΔU〉, shown as a function of the maximum frequency, N.

Figure 4.

Distribution of the energies of the minima and saddle points of our model for different maximum frequencies, N. Each minimum is connected to several saddle points and we have adjusted the statistical weight of each minimum to account for the number of saddle points it is connected to. This re-weighting makes it easier to model the distribution of the barrier heights (see Figure 5). Observe that the energy distributions are approximately Gaussian.

Based on the observation in Figure 4, we suggest a simple analytical model to better understand the distribution of barrier heights. Let U0 be an energy of a minimum sampled from the normal distribution and let Us be the energy of a saddle point sampled from . The difference of these two random variables is a new random variable distributed according to . Since barrier heights are always positive, we keep only positive values after the subtraction of the two Gaussian numbers. The resulting distribution of the above model calibrated with the empirical values of (μs, μ0, σs, σ0) is shown in Figure 5 and it resembles the empirical distribution of Figure 2.

Figure 5.

A Gaussian model is shown for the distribution of barrier heights at different maximum frequencies.

The model for the dynamics

The time-evolution of the system is determined by the Brownian dynamics equation

| (3) |

where β > 0 is the inverse temperature and B is a standard Brownian motion. The friction coefficient, γ, is assumed to be equal to one.

It was already stated in the Introduction that we distinguish two disjoint subsets R (for reactant) and P (for product) of the conformational space Ω. The initial point, x0, is a random sample from a probability distribution with density p0. The probability density, p0, is zero outside of R, so the trajectories of (3) always start from the reactant set.

Let T be the time it takes a trajectory of (3) to reach P for the first time. In other words, T is the first passage time of X(t) and we are interested in estimating its mean, 〈T〉, as well as the stationary probability of finding X(t) at an arbitrary region within the conformational phase space Ω.

The most straight-forward route to estimating 〈T〉 and the stationary probability is to compute a large number of trajectories of (3). Alternatively, as known from Stochastic Calculus4, we can solve the initial-boundary value problem (IBVP):

| (4) |

The solution, u, of the above problem is the density of trajectories that remain in Ω at time t. The operator 𝒥 is defined by 𝒥u = β−1u + u∇U. Furthermore, the function , defined in terms of the solution of (4), solves (by Duhamel’s principle5) the boundary value problem (BVP)

| (5) |

The solution υ is proportional to the density of the stationary probability8 and the mean first passage time (MFPT) is given by

| (6) |

The formulation as a BVP allows us to turn the problem into a deterministic one and to solve it using standard techniques from Numerical Analysis of Partial Differential Equations, thereby eliminating the sampling error and leaving only the discretization error. This is advantageous in the low-dimensional setting that we are dealing with in this paper because this approach is less computationally expensive than time-stepping and it allows us to carry out extensive sampling of the set of energy landscapes. Clearly, in higher dimensions the direct solution of the BVP becomes impractical and we must resort to trajectory-based methods.

As we previously stated, we are interested in the calculation of kinetics on the rough energy landscapes discussed, as well as in the determination of their stationary probabilities. More specifically, we will investigate the MFPT and the stationary probability as a function of system roughness (the frequency N) and as a function of temperature.

Milestoning framework

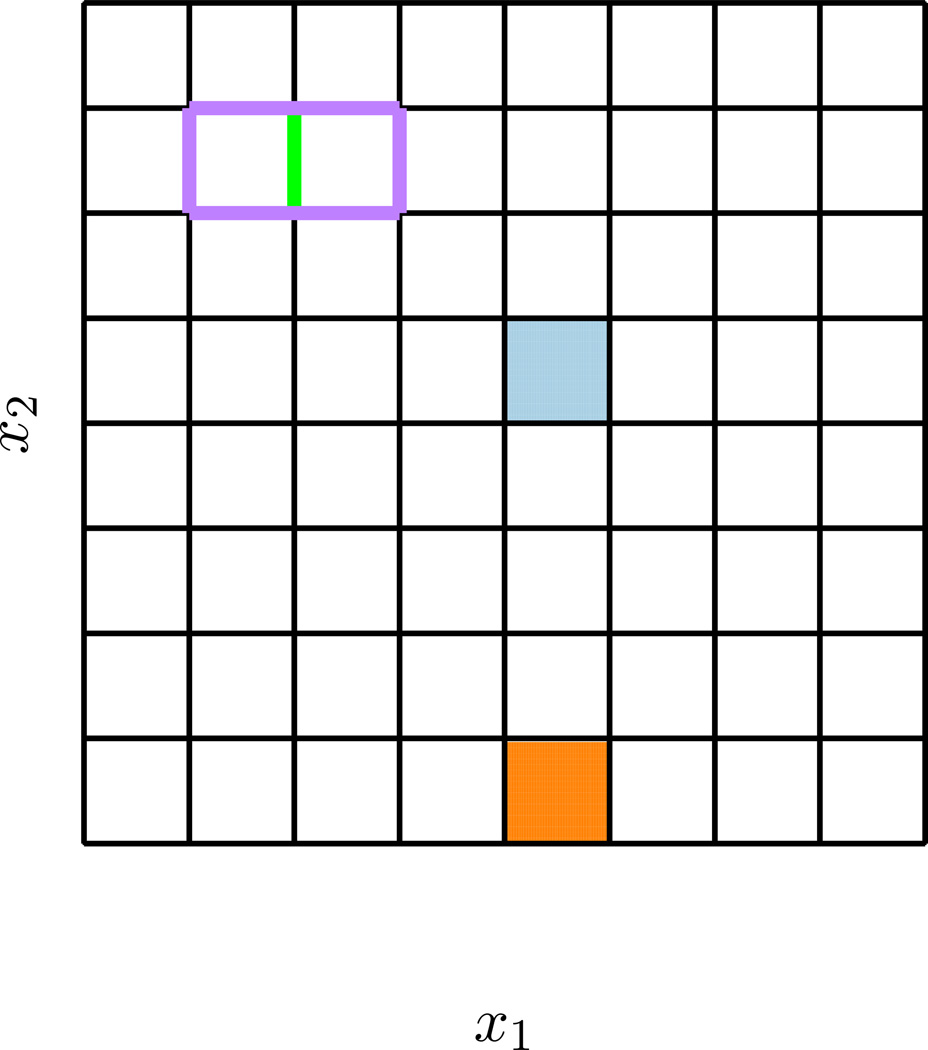

In the Introduction, we commented that the milestones are the common boundaries of pairs of cells in phase space. We denote these cells by Ωi. In the present paper, in which we consider the dynamics on a model of rough energy landscapes, we use an equally-spaced grid (Figure 6) of milestones which can be regarded as the Voronoi tessellation generated by a set of anchors placed at the centers of the squares. It is not required that the Voronoi tessellation be equally-spaced and arbitrary tessellations will work, as was first proposed in6. All that is required is that the boundaries of the reactant set R and the product set P should lie in the boundaries of some of the cells.

Figure 6.

Schematic drawing of the setup of boundary and initial conditions in the periodic domain under consideration. The small orange box at the lower edge is the location of the reactant state whereas the blue box at the center is the product state. Trajectories that reach the boundary of the product state are instantaneously reinjected at the boundary of the reactant state. Each segment of the mesh is a milestone. Also shown at the left is a single initial milestone (green line) and its corresponding neighboring (purple) milestones. In a Milestoning simulation, trajectories are started at a point xi on the green milestone and run until they reach a point xj on any of the purple milestones. See the Methodology section for more details.

In Milestoning, we consider explicit dynamics only between nearby milestones, i.e. the starting and the final milestones must share a cell and a trajectory only needs to exit a cell (a cell occupies only a small fraction of the total phase space volume). We initiate trajectories at one milestone (say, the green line of Figure 6) and integrate the equations of motion until the trajectory reaches another milestone (any of the purple segments in Figure 6) for the first time. The identity of the initiating and terminating milestones, and the length of the trajectory are recorded for further processing. The full theory of Milestoning is discussed elsewhere7,13,14 so here we describe the essential variables and the final equations for the iterative (exact) variant of the method.

The flux at milestone i is the density function, denoted by qi, that determines the distribution of trajectories passing through milestone i per unit area per unit time. Our trajectory fragments are obtained by sampling from a transition kernel, Kij(xi, xj, t) with xi drawn from the (a priori unknown and generally time-dependent) fluxes, qi. The kernel Kij determines the probability that a trajectory initiated at the point xi at milestone i will hit the point xj of the milestone j at time t > 0 before hitting any other milestone different from i.

We are particularly interested in the stationary regime in which all the fluxes become time-independent. The stationary (or steady-state) regime is attained because the reactant state R and the product state P act respectively as a source and a sink so that trajectories arriving to P are instantaneously reinjected at R. This construction is widely used in chemical kinetics, where we consider stationary conditions in which the rate of disappearance of intermediate species is equal to the rate in which the intermediates are created, leading to a time-independent state.

It is convenient to define the time-independent kernel,

| (7) |

as the probability density that a trajectory initiated at the point xi of milestone i will hit for the first time the point xj of milestone j before reaching any other milestone (different from i), regardless of the time required to arrive at xj.

The flux is unknown but it must be the (unique) eigenfunction corresponding to the unit eigenvalue of the time-independent kernel (7) (see14). That is,

| (8) |

The integration above is over the surface area of the i-th milestone (denoted from now on by Mi) and the summation is over all other milestones from which trajectories can reach milestone j directly (without passing through another milestone in between). The numerical estimation of the right hand side of (8) requires that we calculate the (short-)time evolution of trajectories started from points sampled from qi until the trajectories hit the milestone j. This time propagation problem can be solved either by sampling trajectories or by space discretization using PDE solvers. A numerical algorithm to solve the above integral equation in the unknown qi is based on the power iteration22

| (9) |

where will be defined below.

It is useful to break the calculation in (9) into several steps. We first define the weight of a milestone, , and the normalized distribution within a milestone, , by the formula

| (10) |

Next, we write

| (11) |

The function is the probability density of the distribution of first hitting points (FHPD) generated at milestone j by trajectories initiated at milestone i whose starting points are samples from the probability with density .

Substituting (10) into (9) and integrating over Mj, we have

| (12) |

where the are the entries of a matrix K(n). Note that (12) is simply a matrix eigenvalue problem. The can be determined by sampling trajectories or by solving BVPs (as shown at the end of this section) while the weights are the solution of the above eigenproblem (see7 for additional details). It follows from (10), (11), and (12) that

| (13) |

The iterative procedure determined by (9) and (12) converges to (8) whenever the matrices K(n) can be regarded as the transition kernels of an irreducible, aperiodic Markov chain.

In order to start the iterative process just described, we need an initial guess, . A choice that we have have found to be efficient for systems close to equilibrium is

From the flux, q, we can compute the stationary probability that the last milestone that was passed is i by the formula

| (14) |

The function ti(xi) is the average time it will take a trajectory initiated at milestone i until it hits for the first time any other milestone different from i. This can be written as the first moment of the time-dependent kernel

| (15) |

We refer to the value ti = ∫Mi ti(xi) dxi, as the local mean first passage time for milestone i.

The free energy, F, is estimated by

| (16) |

The free energy above should not be confused with the equilibrium free energy, as the term pi in (16) comes from a non-equilibrium system. However, in principle, it is possible to obtain equilibrium free energies using Milestoning by changing the nature of the boundary conditions of the system to ensure detailed balance. The mean first passage time is also obtained via the flux function q. In7, we derive the following formula for the MFPT

| (17) |

where the denominator is a sum over the converged weights of all the milestones, Mf, that constitute the boundary of the product state P.

Notice that the term in the denominator is different from the corresponding term in another formula for the MFPT presented in8. Despite the similarity, (17) is the formula that gives the correct results in the context of Milestoning.

Milestoning using boundary value problems

As we mentioned earlier, we partition the conformational space Ω into cells Ωi whose boundaries are the union of all the milestones. For each milestone, say Mi, there are exactly two cells, Ωi,1 and Ωi,2, that have Mi as a common boundary. At each iteration n, we can assign to Mi the following BVP

| (18) |

Notice that the problem above is just the result of modifying (5) so that Ω becomes Ωi1∪Ωi1, p0 is replaced by , and P is substituted by the set of points x ∉ Ωi1 ∪ Ωi2.

The solution, , allows us to extract the flux on the remaining boundaries of Ωi1 and Ωi2 as well as the local MFPT. Indeed, we have

where nj(xj) is the unit vector normal to the milestone Mj at the point xj. We can substitute the expression for into (12) and (13) to get the weights and the densities . Moreover, in the BVP formulation, the local mean first passage times are expressed, similarly to (6), as

and

where, as in (17), the indices f go through all the milestones in the boundary of the product set P.

In practice, we discretize (18) using an up-winding method for the transport term and centered differences for the remaining terms25 with a spatial step length of Δx1 = Δx2 = 0.006. Then, the problem becomes a system of linear equations Av = f on the unknown vector v with entries determined by where the right hand side f is characterized by . To reduce the cost of solving this linear system, we compute a sparse PA = QR decomposition22,24 where P is a permutation matrix, Q is a unitary matrix, and R is an upper-triangular matrix. This transforms the calculation into a simple back-substitution on the triangular system R v = QTP f. The cost of the QR decomposition is amortized over the iterations.

Closed form solution in the one-dimensional case

Here we show how to relate the formulas discussed in1 with the Milestoning framework previously described. The one-dimensional analogue of the potential energy function (2) is

| (19) |

where x ∈ [0, L). The mean first passage time of a trajectory started at R = L/2 and stopped when it reaches P = L for the first time has the closed form formula (used in1):

| (20) |

The expression (20) is the solution1,4 (evaluated at x = R) of the BVP

where Ω = (0, L) ⊂ ℝ (note the reflecting boundary condition at x = 0). In the present paper, we are concerned with the related BVP

| (21) |

The solution of the above problem evaluated at R yields the MFPT, 〈T〉, where both boundaries 0 and L are absorbing. A problem closely related to (21) is

| (22) |

where a < z < b. Indeed, (22) is the adjoint of (21) when (a, b) = Ω. Note that this is also the one-dimensional analogue of (5) and (18). As we have already seen, the solution υ provides us with all the information we need in Milestoning.

It is possible to obtain a closed form expression for υ, namely

| (23) |

and H is the Heaviside step function. Moreover, the mean first passage time of a process that started at z and stopped whenever it exits the interval (a, b) is

| (24) |

This means that Milestoning in a one-dimensional setting can be reduced to a quadrature problem by setting z = Mi, a = Mi−1, and b = Mi+1 and computing (23) and (24) for each i.

RESULTS

We computed a set of numerical experiments that consisted in calculating the flux, MFPT, and stationary probability for an ensemble of random energy landscapes of the form (2). In what follows we describe the details of the procedure. Each experiment was carried out for N = 4, 5, 6, 7 using a grid of 2 × 40 × 40 = 3200 milestones (the first factor of two comes from the fact that we count horizontal and vertical milestones) with the constants L = 10 and A = 1.59155. We considered a set of 20 temperatures ranging between β−1 = 0.2 and β−1 = 5. For each specified N and for each temperature, we generated more than 1600 random energy landscapes and computed the stationary flux, probability, and MFPT using Milestoning following the BVP-based procedure detailed in the Methodology section.

Even though our system is low dimensional, the choice of temperatures and parameters of the potential energy function makes the calculation of first passage times remarkably hard due to the number of metastable states and the depth of the energy barriers. Indeed, looking at the tails of the distributions in Figure 2 and the range of temperatures used, we see that the dimensionless barrier heights, βΔU, range between 1/2 and 20. Milestoning is useful for these experiments not just due the intrinsic parallel nature of the method (as opposed to computing long-running trajectories that require serial computation) but also because it is hard to reliably obtain good statistics of the MFPTs.

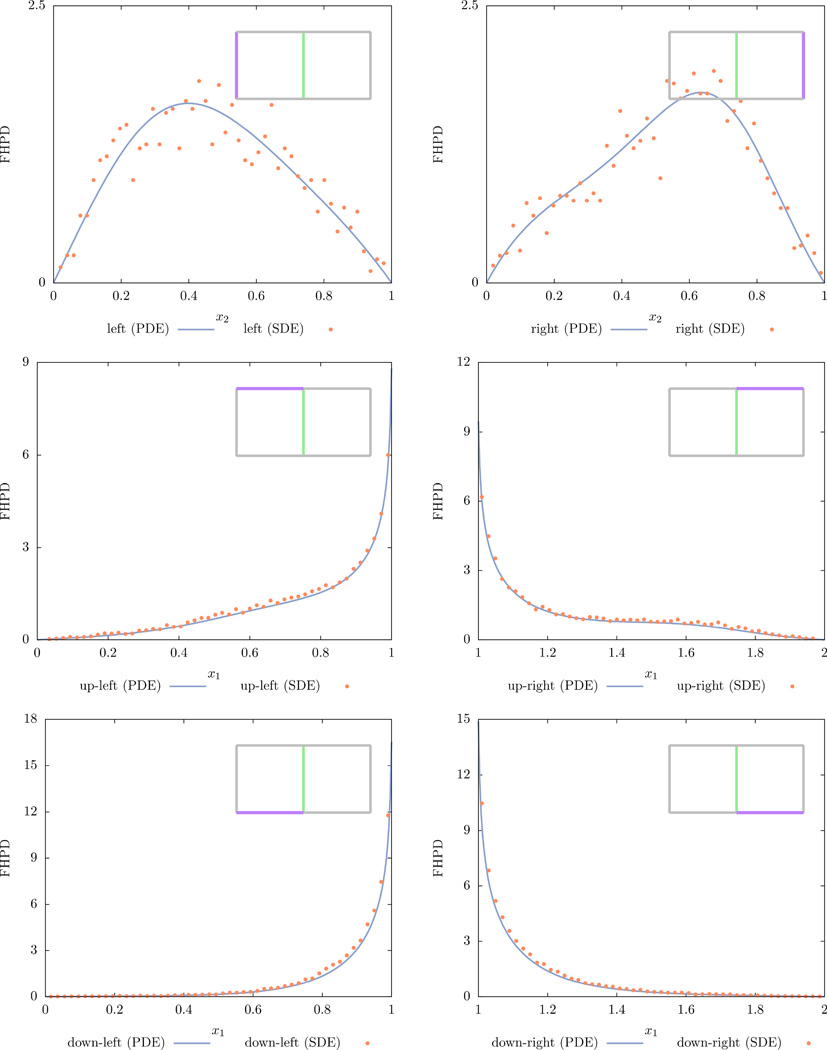

The actual computation of local MFPTs and FHPDs needed to obtain the flux q was done using the BVP-based formulation previously described. In Figure 7 and Table 2 we show a comparison of the FHPDs generated using the two methods for a milestone in order to illustrate the equivalence of the two approaches.

Figure 7.

Illustration of first hitting point distributions (FHPDs) used in Milestoning calculations. Trajectories are initiated at the central milestone (the vertical line at the center of the inset) and are computed until they hit for the first time a nearby milestone marked as a purple line. In orange dots, we show the average results of explicit trajectory calculations while in green we show the solution of a corresponding BVP (see text for more details). Table 2 shows the actual induced entries of the transition matrix Kij as well as the local MFPT for these milestones.

Table 2.

Example of the entries of a row of the transition matrix Kij. The results were obtained by integrating 105 trajectories using Δt = 10−6 (center column) and by solving the associated BVP using Δx1 = Δx2 = 10−3 (right column). The local MFPTs obtained are, respectively, 0.046 and 0.041. The entries and times correspond to the same tile displayed in Figure 7.

| j | Trajectory | BVP |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.014 | 0.013 |

| 2 | 0.023 | 0.02 |

| 3 | 0.133 | 0.136 |

| 4 | 0.123 | 0.127 |

| 5 | 0.335 | 0.333 |

| 6 | 0.373 | 0.37 |

If 〈T(n)〉 denotes the estimate for the MFPT at the n-th iteration, we stop the iterative procedure when the distances of the weights and the estimated MFPTs between two consecutive iterations go below a threshold of 10−2. That is, when |T(n) − T(n−1)| / |T(n)| < 10−2.

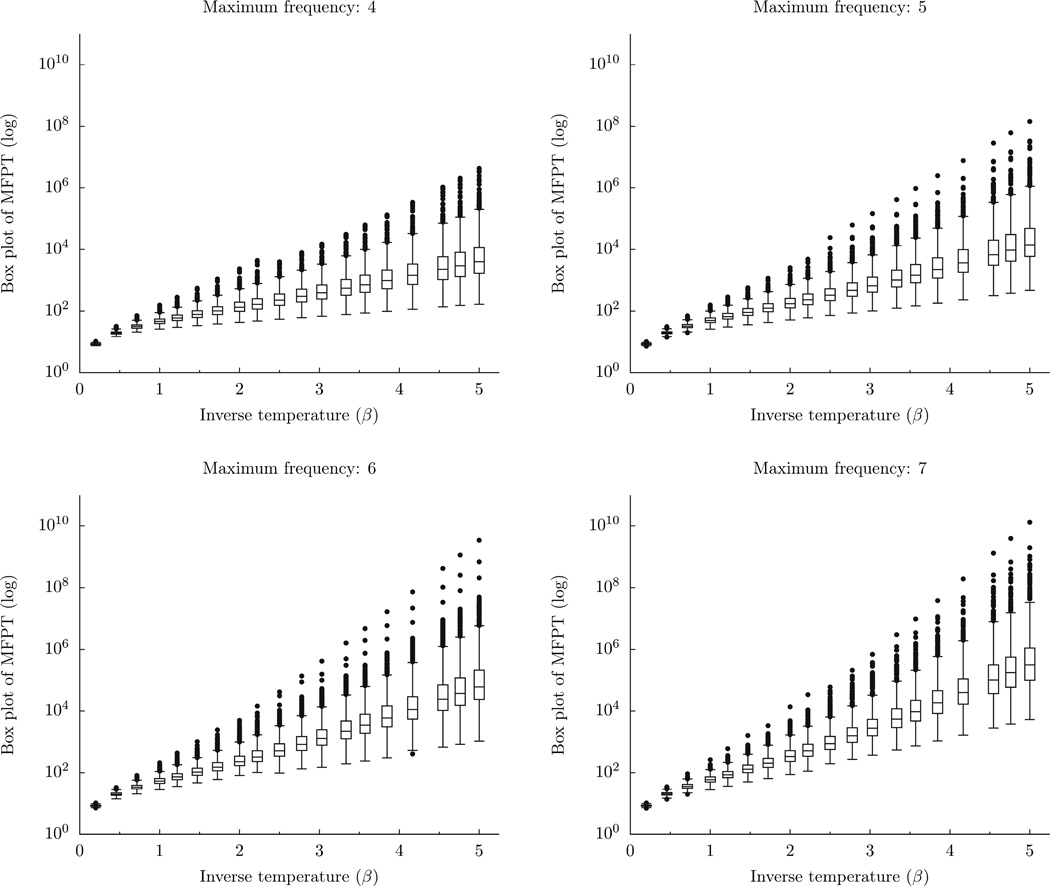

By carrying out Milestoning simulations on different values of the maximum allowed frequency and the temperature, we have estimated the dependence of the global MFPT (6) on the inverse temperature β and the maximum frequency N. These results shown in Figure 9 represent the outcome of more than 1600 realizations (per temperature per maximum frequency) of the basic experiment.

Figure 9.

Mean first passage time as a function of the inverse temperature for a number of maximum frequencies N.

DISCUSSION

The global MFPT, when regarded as a function of the inverse temperature, 〈T〉 = 〈T(β)〉 shows two markedly different behaviors. At high temperatures (say for β < 2.5) the MFPT is a linear function of β, as the influence of the energy landscape on the dynamics becomes much smaller than the effect of the thermal fluctuations (see Figure 9). This means that we are close to the purely diffusive regime (i.e., constant potential energy). By contrast, away from high temperatures (say, for β ≥ 2.5), the MFPT can be approximated by an exponential function of the form

where A, B, and C are constants (see Figure 10). Since we already saw evidence (see Figures 2 and 3) that the average barrier height, 〈ΔU〉, is a linear function in the maximum frequency, N, we conclude that the transition from reactant to product for the rough energy landscapes under consideration appears to behave like an activated process with a barrier determined by ℓ(N) = A〈ΔU〉 + B for low temperatures.

Figure 10.

Activation energy in Arrhenius fitting of the low temperature regime as a function of the average barrier height of the energy landscapes.

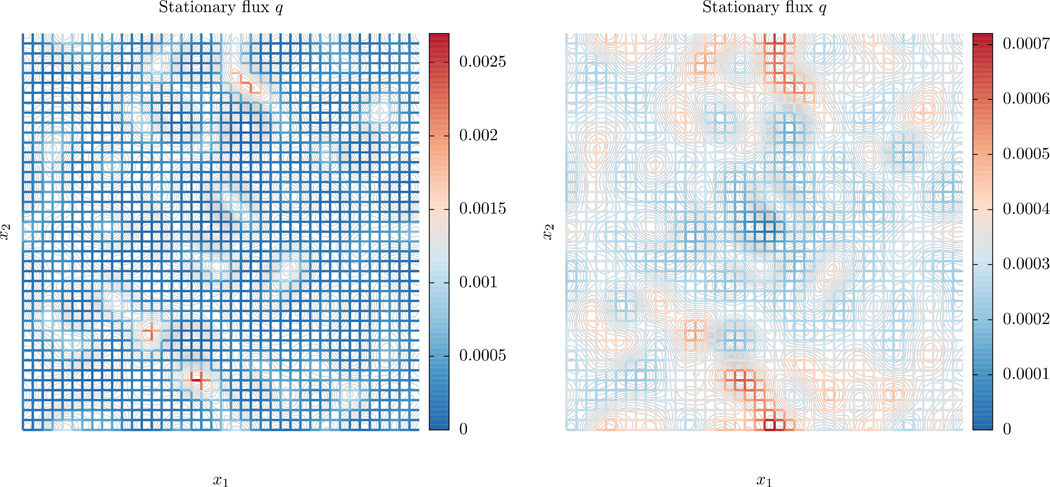

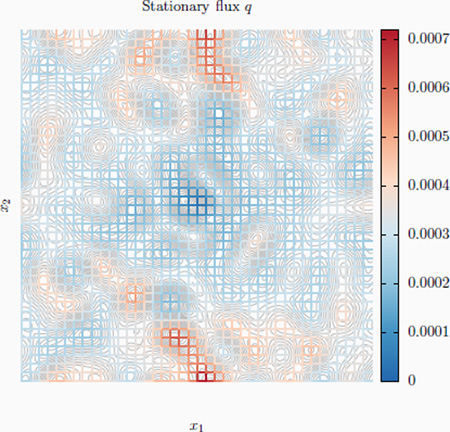

The values of p̄i, introduced in (14), indicate the milestones that are visited more frequently. In Figure 8, we see that the system visits many regions in the conformational phase space when the temperature is high. This is consistent with what we said earlier about the system behaving close to a diffusive motion at high temperatures. By contrast, at low temperatures (see again Figure 8) most of the time the system is trapped in the deepest energy basins, and it is the contribution to (17) of the milestones laying in those energy minima what primarily determines the global MFPT.

Figure 8.

Stationary fluxes (normalized to one) for a rough energy landscape computed with Milestoning. The reactant state (source) is the cell at the center of the lower edge, and the product state (sink) is the cell located at the center of the box. The upper panel is for temperature 0.8 and the lower panel for temperature of 2.

Our results are consistent with those obtained by applying the exact formula (24) in the case where the energy landscapes (2) are one-dimensional instead of two-dimensional. Additionally, these results appear to be in agreement with a simpler but related model introduced in9. We discuss below the one-dimensional case.

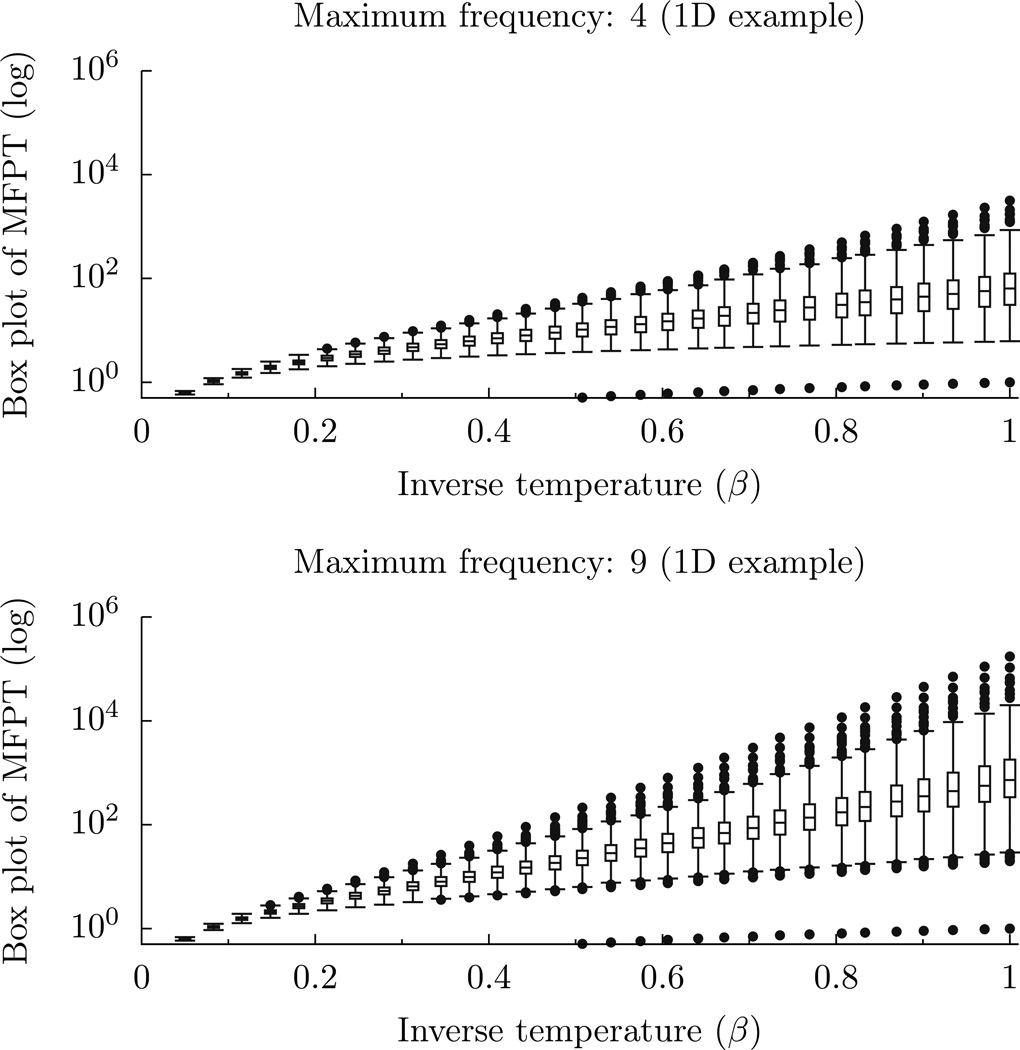

Comparison with the one-dimensional model of Zwanzig

Recall from the Methodology section that (24) allows us to completely solve problem of computing the mean first passage time in the one-dimensional case. Indeed, (24) can be accurately calculated using high-precision quadrature formulas2. In Figure 11, we show the expected value of the MFPT as a function of β for 103 random energy landscapes of the form (19). We find the same behavior of the MFPT as a function of temperature that we observed in the two-dimensional case: a linear dependence of β at high temperatures and an exponential dependence involving β and 〈U〉 at low temperatures.

Figure 11.

Estimated MFPTs as a function of temperature obtained by evaluating the exact formula (24) on 1000 one-dimensional energy landscapes of the form (19) for N = 4 and N = 9.

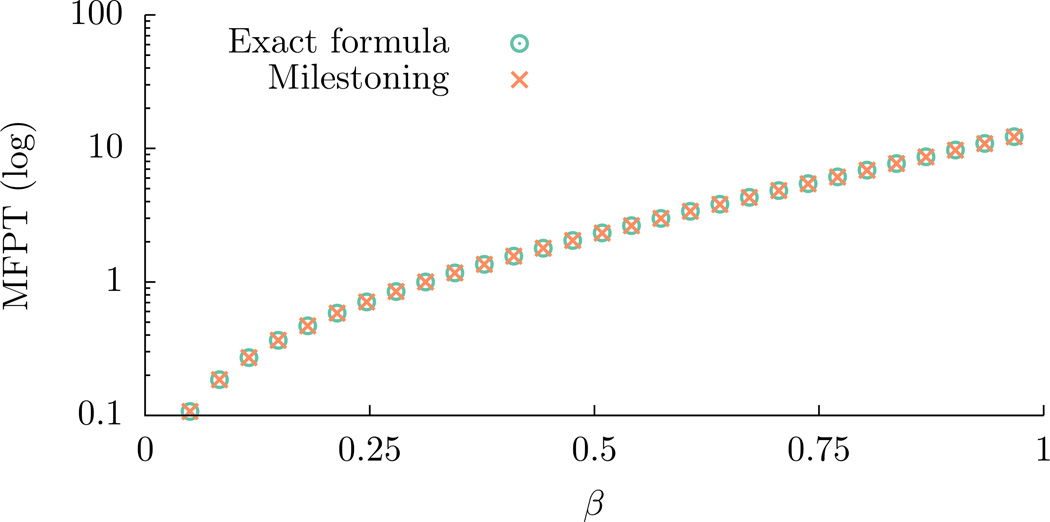

We can go one step further and compare the exact solution of the same energy landscape introduced in1 with the results obtained by doing Milestoning. Let the potential energy function be

and let Ω = (−2, 2) and R = 0 (note that U is the same as1). We did Milestoning in this case by partitioning the interval Ω into a set of 9 equally-spaced milestones M1, …, M9 and using (23), (24), and (17) to compute the MFPT (replacing z by the appropriate Mi and taking a = Mi−1, b = Mi+1). The computed value can be compared with the direct result coming from applying (24) with z = R, a = −2, and b = 2. The obtained MFPTs coincide and their values for a set of temperatures are shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Mean first passage time on the rough energy landscape considered by Zwanzig. The figure shows the results using Milestoning and direct computation of the MFPT by the appropriate closed form formula.

Unfeasibility of simulating long trajectories

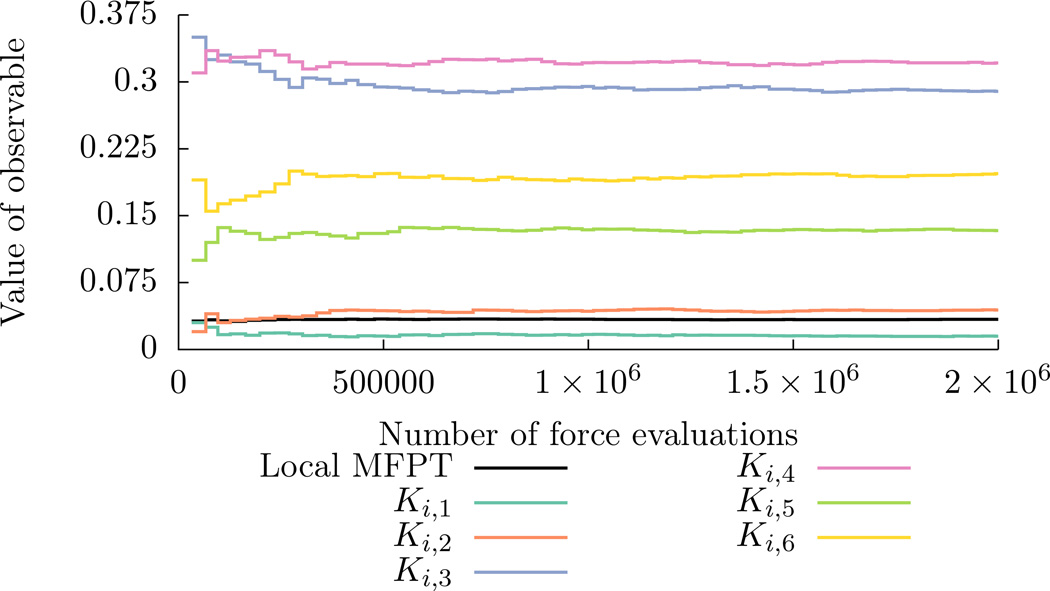

To show the intractability of simulations using long, uninterrupted trajectories, we randomly generated one of the energy landscapes of the form (2) with N = 7 and did a Milestoning simulation at β−1 = 0.2. Next, we located the milestone for which the local MFPT was the largest among all the milestones and then we ran an ensemble of short trajectories using Euler-Maruyama with a time-step length of Δt = 10−4. The cost in terms of number of force evaluations required to estimate the local MFPT and the first hitting point distributions is shown in Figure 13. We see from the results that 2 × 106 force evaluations suffice to attain convergence for the slowest converging milestone in that particular energy landscape.

Figure 13.

Estimates of the local MFPT and the values of the entries in the i-th row of the matrix Kij as a function of the number of force evaluations required for an ensemble of short Brownian dynamics trajectories. The initiating milestone was chosen to be the one for which the maximum value of the local MFPT was attained (that is, the slowest milestone).

To contrast the above findings with a set of long trajectories, we started a total of 104 trajectories from points randomly sampled from the reactant set on the same energy landscape using the same Δt and temperature. We allowed these trajectories to go on for 2 × 106 force evaluations and then we stopped them. It turned out that only 3 of the 104 trajectories started at the reactant were able to reach the product before the imposed bound on the number of force evaluations was exceeded. Moreover, these trajectories were unusually short (two orders of magnitude below the value of the MFPT) and their sample average is very far away from the true mean of the first passage time.

We clearly would not have been able to compute the large amount of estimates of MFPTs presented in this paper if instead of Milestoning we had used long-running Brownian dynamics trajectories.

CONCLUSIONS

We illustrated the method of Milestoning for computing kinetics and thermodynamics on a highly corrugated albeit low-dimensional system. By construction, the system does not have a clear separation of temporal scales and, as such, it presents a significant computational challenge since many techniques for obtaining kinetic properties rely on the existence of such separation.

Milestoning builds on the use of short trajectories to construct thermodynamic and kinetic profiles of complex systems and can efficiently investigate molecular processes without obvious reaction coordinates, transition states, or basins that are strong attractors. On the considered systems, we computed the stationary flux, the stationary probability, and the mean first passage time for migration from a reactant state to a product state.

We compute, using the Milestoning method, the stationary flux (shown), the mean first passage time of Brownian trajectories, and the free energy (not shown) on a large ensemble of random energy landscapes with varying degrees of roughness and at a wide range of temperatures. We find two different behaviors: a diffusive regime for high temperatures and an Arrhenius-like regime for low temperatures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by a grant from the NIH GM59796 and from the Welch Foundation Grant No. F-1783.

References

- 1.Zwanzig R. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85:2029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.7.2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Favati P, Lotti G, Romani F. ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software. 1991;17:218. ISSN 00983500. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold VI. Proceedings of the Steklov Institute of Mathematics. 2006;253:S13. ISSN 0081-5438. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karatzas I, Shreve SE. Brownian motion and stochastic calculus, vol. 113 of Graduate Texts in Mathematics. New York, NY: Springer New York; 1998. ISBN 978-0-387-97655-6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans LC. Partial differential equations, vol. 19 of Graduate Studies in Mathematics. 2nd ed. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society; 2010. ISBN 978-0-8218-4974-3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vanden-Eijnden E, Venturoli M. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 2009;130:194101. doi: 10.1063/1.3129843. ISSN 1089-7690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bello-Rivas JM, Elber R. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 2015;142:094102. doi: 10.1063/1.4913399. ISSN 0021-9606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reimann P, Schmid G, Hänggi P. Physical Review E. 1999;60:R1. doi: 10.1103/physreve.60.r1. ISSN 1063-651X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baronchelli A, Barrat A, Pastor-Satorras R. Physical Review E - Statistical, Non-linear, and Soft Matter Physics. 2009;80:1. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.80.020102. ISSN 15393755, 0905.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chipot C. New algorithms for macromolecular simulation. 2006:185–211. ISSN 14397358. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elber R. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1990;93:4312. ISSN 00219606. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zwanzig R. Nonequilibrium statistical mechanics. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faradjian AK, Elber R. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 2004;120:10880. doi: 10.1063/1.1738640. ISSN 0021-9606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirmizialtin S, Elber R. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 2011;115:6137. doi: 10.1021/jp111093c. ISSN 1520-5215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jas GS, Hegefeld WA, Májek P, Kuczera K, Elber R. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2012;116:6598. doi: 10.1021/jp211645s. ISSN 15206106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreuzer SM, Moon TJ, Elber R. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2013;139 doi: 10.1063/1.4811366. ISSN 00219606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cárdenas AE, Elber R. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2014;141 doi: 10.1063/1.4891305. ISSN 00219606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Earl DJ, Deem MW. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics : PCCP. 2005;7:3910. doi: 10.1039/b509983h. ISSN 1463-9076, 0508111v2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vanden-Eijnden E, Venturoli M, Ciccotti G, Elber R. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 2008;129:174102. doi: 10.1063/1.2996509. ISSN 1089-7690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Straub JE, Thirumalai D. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90:809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.809. ISSN 0027-8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Czerminski R, Elber R. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1989;86:6963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.6963. ISSN 0027-8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golub GH, Van Loan CF. Matrix computations, Johns Hopkins Studies in the Mathematical Sciences. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2013. ISBN 978-1-4214-0794-4; 1-4214-0794-9; 978-1-4214-0859-0. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valleau J. In: Classical and quantum dynamics in condensed phase simulations. Berne BJ, Coker D, editors. chap. 5. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis TA. ACM Trans. Math. Software. 2011;38:22. Art. 8, ISSN 0098-3500. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strikwerda JC. Finite difference schemes and partial differential equations. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics (SIAM); 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schütte C, Noé F, Lu J, Sarich M, Vanden-Eijnden E. The Journal of chemical physics. 2011;134:204105. doi: 10.1063/1.3590108. ISSN 1089-7690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chodera JD, Singhal N, Pande VS, Dill KA, Swope WC. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2007;126 doi: 10.1063/1.2714538. ISSN 00219606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]