Abstract

Background

Prenatal phthalate exposure is associated with altered male reproductive tract development, and in particular, shorter anogenital distance (AGD). AGD, a sexually dimorphic index of prenatal androgen exposure, may also be altered by prenatal stress. How these exposures interact to impact AGD is unknown. Here we examine the extent to which associations between prenatal phthalate exposure and infant AGD are modified by prenatal exposure to stressful life events (SLEs).

Methods

Phthalate metabolites (including those of diethylhexyl phthalate [DEHP] and their molar sum [∑DEHP]) were measured in first trimester urine from 738 pregnant women participating in The Infant Development and the Environment Study (TIDES). Women completed questionnaires on SLEs, and permitted infant AGD measurements at birth. Subjects were classified as “lower” and “higher” stress (0 first trimester SLEs vs. 1+).We estimated relationships between phthalate concentrations and AGD (by infant sex and stress group) using adjusted multiple regression interaction models.

Results

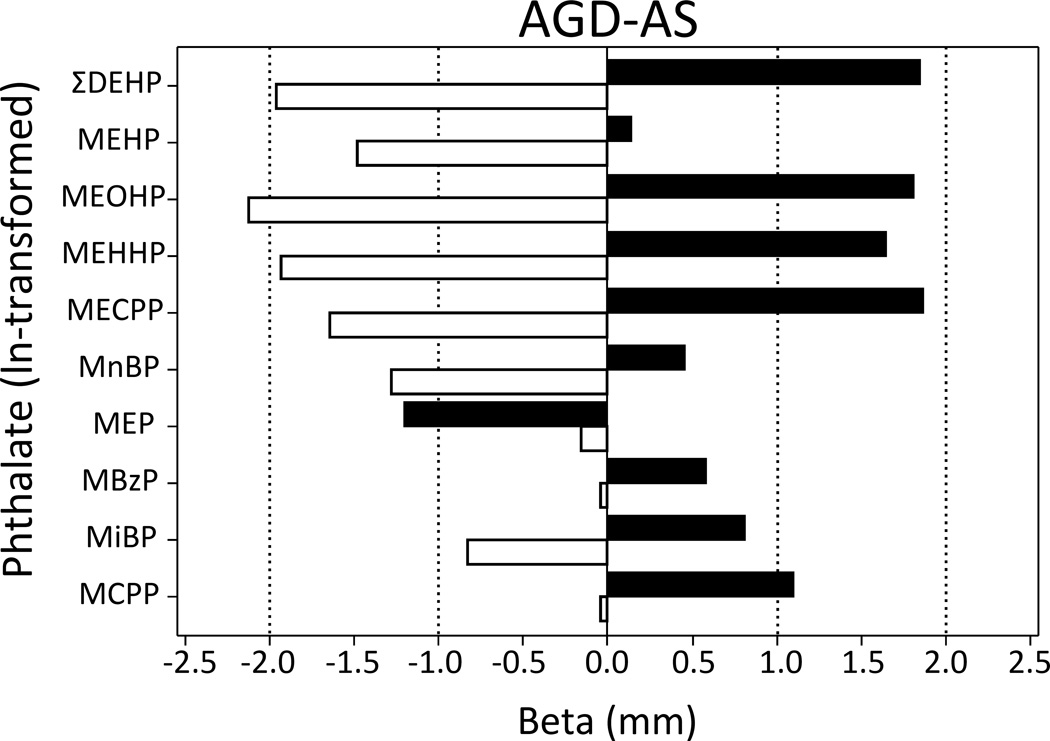

In the lower stress group, first trimester ∑DEHP was inversely associated with two measures of male AGD: anoscrotal distance (AGD-AS; β=−1.78; 95% CI: −2.97, −0.59) and anopenile distance (AGD-AP; β=−1.61; 95% CI: −3.01, −0.22). By contrast, associations in the higher stress group were mostly positive and non-significant in male infants. No associations were observed in girls.

Conclusions

Associations between prenatal phthalate exposure and altered genital development were only apparent in sons of mothers who reported no SLEs during pregnancy. Prenatal stress and phthalates may interact to shape fetal development in ways that have not been previously explored.

Introduction

In mammals, prenatal androgens are important in programming reproductive and sex-dependent development. Testosterone produced by the fetal testes early in pregnancy masculinizes the previously undifferentiated male reproductive tract, whereas in females, androgen levels remain low1. Perturbations to the in utero hormonal milieu can alter the course of development, with long-lasting health effects2. The most striking evidence comes from genetic disorders characterized by atypical androgen activity, such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), in which changes in the prenatal hormonal milieu can have profound impacts on reproductive physiology and neurodevelopment3. Androgen activity can also be altered in more subtle ways, such as by prenatal exposure to environmental chemicals (e.g. phthalates) or smoking4, 5.

Anogenital distance (AGD), the distance from the anus to the genitals, is a sensitive biomarker of the prenatal androgen environment and is typically 50–100% longer in males than in females6. In male rodents, prenatal anti-androgen administration shortens AGD7, whereas in female rodents, androgen administration results in longer, masculinized AGD8. AGD may also predict reproductive function and fertility later in life. In men, shorter AGD is linked to poorer semen quality and lower testosterone levels9, 10, whereas in women, longer AGD is associated with multifollicular ovaries and higher testosterone levels11, 12.

Prenatal exposure to diethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP), an environmental chemical that interferes with testosterone production, is associated with shorter AGD in newborn boys13, 14. DEHP is widely found in consumer goods and nearly 100% of Americans have measurable urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations15. In The Infant Development and the Environment Study (TIDES), the largest study on phthalate exposure and AGD to date (n=753), maternal DEHP metabolite concentrations measured during the first trimester (the critical time period for androgen-related programming of the male reproductive system) were inversely associated with AGD in newborn boys16. No associations were observed between prenatal phthalate exposure and female AGD.

Beyond environmental chemicals, any exposure affecting prenatal androgen concentrations may alter AGD as well. For instance, we found that prenatal exposure to stressful life events (SLEs) is associated with longer AGD in infant girls, suggesting that like phthalates, prenatal stress may alter typical androgen activity17. To the extent that prenatal exposure to stress and phthalates impact the same biological pathways (i.e. androgen production) or influence the same endpoints (i.e. AGD), there may be important interactions to consider. In a previous pregnancy cohort study (the Study for Future Families; SFF), we found an inverse association between maternal DEHP metabolite concentrations in pregnancy and son’s AGD in infancy among families reporting few stressful life events (SLEs) during pregnancy; no associations were observed in sons whose parents who experienced numerous SLEs during pregnancy18. However the sample size for that analysis was very small (n=105 mother-son dyads) and the timing of urine collection and AGD measurement was imprecise. Here, we use the larger TIDES cohort to further examine the extent to which the relationship between prenatal phthalate exposure and reproductive development may be modified by prenatal stress.

Methods

Study population

TIDES methods have been described elsewhere16. Briefly, women were recruited from prenatal clinics at four U.S. academic medical centers (University of California-San Francisco, University of Washington, University of Minnesota, and University of Rochester) from 2010–2012. Eligibility criteria included: less than 13 weeks pregnant, age 18 or older, pregnancy not medically threatened, and planning to deliver in a study hospital. Institutional Review Boards approved the study prior to the start of study activities and all subjects signed informed consent.

Questionnaires

Subjects completed questionnaires in each trimester, including items on lifestyle, demographics, and health. The third trimester questionnaire included questions on SLEs, adapted from two validated questionnaires19, 20, and used in our previous work17, 21. Women were asked if the following events had occurred during the current pregnancy, and if so, during which trimester: job loss; serious family illness or injury; death of a close family member; relationship difficulties with the partner; serious legal/financial issues; or any other major life event. We focus here on first trimester SLEs to target the male programming window (MPW). Women reporting 1 or more SLEs were considered a “higher stress” group, whereas women reporting no SLEs were considered a “lower stress” group.

Urine samples

In each trimester, subjects gave a spot urine sample during routine prenatal care, and urine sample collection, processing, and analysis have been described in greater detail elsewhere16. Here we focus solely on phthalate metabolites measured in first trimester samples, corresponding to the MPW. For funding reasons, first trimester phthalate metabolites were measured at two different labs. All samples from mothers who gave birth to boys were analyzed at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The CDC also measured phthalate metabolites in 25% of first trimester samples from mothers who gave birth to girls, with the remaining girls’ samples analyzed at the University of Washington16. Both laboratories used standard analytic methods based on enzymatic deconjugation of phthalate metabolites from their glucuronidated form, followed by automated on-line solid-phase extraction, high performance liquid chromatography separation, and detection by isotope-dilution tandem mass spectrometry22. Isotopically labelled internal standards and conjugated internal standards were used to improve precision and accuracy. Following convention, values below the limit of detection (LOD) were assigned the value LOD/(√2)23. Ten samples from mothers of girls were run in both labs for comparative purposes.

Birth exams

Shortly after birth, TIDES infants underwent physical examinations administered by trained study coordinators, as described in detail elsewhere24. Two AGD measurements (in mm) were made on each infant, each one a distance from the center of the anus to a genital landmark using dial calipers. In males, those landmarks were: 1) the anterior base of the penis, where penile tissue meets pubic bone (anopenile distance; AGD-AP); and 2) the base of the scrotum where skin texture changes from ruggated to smooth (anoscrotal distance; AGD-AS). In females, those landmarks were: 1) the anterior side of the clitoral hood (anoclitoral distance; AGD-AC); and 2) the posterior end of the fourchette, where the labia fuse (anofourchette distance; AGD-AF). In addition, we measured penile width (PW; diameter at the base of the flaccid penis) in males. For each measure, three independent measurements were taken, and the mean was used in the current analysis.

Statistical analysis

Phthalate metabolite concentrations were natural log-transformed and SpG-adjusted using the following formula: Pc= P [(1.014−1)/(SpG−1)]. In this formula, Pc is the SpG-corrected phthalate concentration, P is the phthalate concentration as measured, 1.014 is the mean SpG for all TIDES urine samples, and SpG is the specific gravity of the individual urine sample25. Based on previous research on phthalates and reproductive development, our primary analyses focused on male infants and on the metabolites of DEHP and their molar sum: ∑DEHP= (MEHP*(1/278)) + (MEHHP*(1/294)) + (MEOHP*(1/292)) + (MECPP*(1/308)) nmol/ml16. Secondarily, we examined associations in females and considered other phthalates. All analyses were stratified by infant sex. We calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficients to compare the results of phthalate metabolite assays across the two labs.

We examined univariate statistics for all variables of interest. A set of covariates predicting AGD in previous work were selected for a priori inclusion in all multivariable models: infant age at exam, gestational age at birth, study center, weight-for-length z-score, time of urine collection, maternal age, and race9, 16. We considered several additional potential covariates including: marital status, income, education, smoking during pregnancy, 1st trimester pregnancy complications and hospitalizations, pre-pregnancy weight, and maternal weight gain. We conducted bivariate analyses (correlations, chi-square, Wilcoxon, and Mantel-Haenszel tests) examining associations between these variables and our exposures and outcomes of interest. Only income and marital status were associated with our exposures and outcomes of interest in bivariate analyses, however did not change estimates in multivariable models more than 10% and were not retained. Ultimately, only the covariates selected a priori were included in final models.

We fit several sets of multivariable models..First we fit linear regression models examining maternal stress and genital endpoints (without phthalates), adjusting for our selected covariates. We then fit a set of linear regression models (without interaction terms) looking at the relationship between ∑DEHP concentrations and AGD, adjusting for our selected covariates as well as maternal stress. Next, we fit models including a stress × phthalate interaction term (including terms for the main effects of stress and phthalates), to estimate the significance of the interaction. By re-parameterizing these models, we obtained estimates specific to the higher and lower stress groups without reducing power by stratifying. We report all results of these models, regardless of the significance of the interaction term. Analyses were repeated for the individual DEHP metabolites and the other metabolites measured. In sensitivity analyses, we refit multivariable models using number of SLEs reported as an ordinal variable. Standard regression assumptions were checked including normality of residuals and homoscedasticity. Outliers (individuals with standardized residuals greater than three standard deviations) were removed from analyses. Analyses were conducted in SAS (Version 9.3, Cary, NC) and results were considered significant at p<0.05.

Results

In total 754 TIDES subjects had first trimester phthalate concentrations measured, completed questions on SLEs, and had a child who underwent a physical exam at birth (370 boys and 384 girls). Two boys who were outliers (residual values beyond 3 SD of the mean) were dropped from analyses. Nine infants were missing information on birth size and five women were missing information on marital status, age, and race. Finally, one boy was missing AGD-AP measurements and one girl was missing AGD-AC measurements, so they could only be included in models measuring AGD-AS and AGD-AF, respectively. Ultimately, 738 mothers and their infants were included in this analysis (Table 1). Overall, the cohort was well-educated and most were married or living as married. Three-quarters of women had a college education or more and nearly half had a household income over $75,000. Very few women reported smoking during pregnancy (5%). Physical exams took place at median age 1 day (mean age: 6 days).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of TIDES subjects.

| Boys | Girls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous variables; mean ±SD | All subjects (n=738) |

Lower stressa (n=293) |

Higher stressa (n=73) |

Lower stressa (n=302) |

Higher stressa (n=70) |

| Maternal age (years) | 31.1±5.5 | 31.1±5.4 | 30.3±5.1 | 31.7±5.5 | 29.2 ±5.8 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 25.6±6.4 | 25.2±5.9 | 27.8±7.7 | 25.2±6.3 | 26.3±6.7 |

| Number of life events stressors during first trimester | 0.3±0.6 | 0 ± 0 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 0±0 | 1.3 ±0.7 |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | 39.3±1.8 | 39.3± 1.7 | 39.2±2.0 | 39.4 ±1.9 | 39.4±1.4 |

| Age at birth exam (days) | 6.3± 15.4 | 6.6±14.1 | 9.5±19.2 | 5.2±14.7 | 7.0±18.7 |

| Weight for length z-score (ZWL) | −0.4±1.3 | −0.4 ±1.3 | −0.6±1.1 | −0.3±1.3 | −0.4±1.3 |

| Genital measurements- male infants | |||||

| AGD-AS (mm) | 49.6±5.6 | 49.6±5.8 | 49.4±4.9 | ||

| AGD-AP (mm) | 24.7±4.4 | 24.7 ±4.6 | 24.7±3.7 | ||

| Penile width (mm) | 10.8 ±1.3 | 10.8±1.3 | 11.0±1.3 | ||

| Genital measurements- female infants | |||||

| AGD-AF (mm) | 36.6±3.9 | 36.7±3.9 | 36.6±3.8 | ||

| AGD-AC (mm) | 16.0±3.2 | 16.0±3.2 | 16.4±3.0 | ||

| Categorical variables; N(%)b | |||||

| Study Center | |||||

| San Francisco, CA | 185 (25) | 69 (24) | 18 (25) | 86 (28) | 12 (17) |

| Minneapolis, MN | 200 (27) | 89 (31) | 19 (26) | 73 (24) | 19 (27) |

| Rochester, NY | 205 (28) | 73 (25) | 28 (38) | 77 (26) | 27 (39) |

| Seattle, WA | 148 (20) | 62 (21) | 8 (11) | 66 (22) | 12 (17) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 536 (73) | 210 (72) | 52 (71) | 231 (76) | 27 (39) |

| Other | 202 (27) | 83 (28) | 21 (29) | 71 (24) | 43 (61) |

| Smoked in last week | 40 (5) | 15 (5) | 4 (5) | 15 (5) | 6 (9) |

| Education: Less than college graduate | 185 (25) | 69 (24) | 27 (38) | 64 (21) | 26 (37) |

| Household income | |||||

| Less than $15,000 per year | 107 (15) | 31 (11) | 20 (27) | 34 (11) | 21 (31) |

| $15,000–$25,000 per year | 61 (8) | 22 (8) | 8 (11) | 25 (8) | 6 (9) |

| $25,001–$45,000 per year | 66 (9) | 28 (10) | 6 (8) | 22 (7) | 10 (14) |

| $45,001–$55,000 per year | 43 (6) | 18 (6) | 6 (8) | 13 (4) | 6 (9) |

| $55,001–$65,000 per year | 37 (5) | 19 (6) | 5 (7) | 13 (4) | 0 (0) |

| $65,001–$75,000 per year | 49 (7) | 21 (7) | 2 (3) | 23 (8) | 3 (4) |

| More than $75,000 per year | 354 (48) | 147 (50) | 26 (36) | 161 (53) | 20 (29) |

| Married or living as married | 616 (84) | 254 (87) | 53 (73) | 260 (86) | 49 (70) |

Lower stress= no life events during first trimester of pregnancy; higher stress=1 or more life events during first trimester.

Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding or missing values.

Nineteen percent of mothers reported one or more first trimester SLEs and were classified as “higher stress”. Of these, 111 reported one stressor, 23 reported two stressors, and 9 reported three or more stressors. Higher stress mothers were younger with higher pre-pregnancy BMI and a lower household income than lower stress mothers. They were also less likely to have a college education or be married, and more likely to be non-Caucasian and from the Rochester study center. Genital measurements were similar in infants born to higher and lower stress mothers. Overall, phthalate metabolite concentrations tended to be higher in higher stress mothers than in lower stress mothers (Table 2). In 10 urine samples from mothers of girls that were assayed at both labs, phthalate metabolite concentrations were highly correlated (r ranging from 0.78 to 0.98) with the exception of MBzP (r=0.52; not shown).

Table 2.

First trimester urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations in TIDES subjects by stress group (in ng/mL).

| Phthalate | Metabolite | LOD | %>LOD | All mothers (n=738) |

Lower stress (n=595) |

Higher stress (n=143) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDCa | UWb | Geometric mean (95% CI) | |||||

| Diethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) | Mono-2-ethylhexyl (MEHP) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 65.8 | |||

| Mono-2-ethyl-5-oxohexyl (MEOHP) | 0.2 | 1.0 | 97.1 | 1.93 [1.77, 2.12] | 1.87 [1.69, 2.07] | 2.21 [1.81, 2.70] | |

| Mono-2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl (MEHHP) | 0.2 | 0.2 or 1.0 | 97.1 | 4.23 [3.84, 4.65] | 4.07 [3.66, 4.52] | 4.94 [3.97, 6.14] | |

| 0.2 | 0.2 or 1.0 | 97.1 | 6.06 [5.51, 6.67] | 5.84 [5.25, 6.49] | 7.07 [5.65, 8.85] | ||

| Mono-2-ethyl-5-carboxypentyl (MECPP) | 8.16 [7.45, 8.94] | 7.88 [7.12, 8.72] | 9.46 [7.71, 11.62] | ||||

| ∑DEHPc | N/A | N/A | N/A | 71.92 [65.76, 78.66] | 69.32 [62.74, 76.58] | 83.84 [68.36, 102.84] | |

| Diethyl (DEP) | Mono-ethyl (MEP) | 0.6 | 1 | 99.1 | 28.17 [25.05, 31.69] | 26.51 [23.24, 30.24] | 36.31 [28.04, 47.03] |

| Butylbenzyl (BBzP) | Mono-benzyl (MBzP) | 0.3 | 1.0 | 87 | 3.31 [2.98, 3.68] | 3.10 [2.76, 3.49] | 4.34 [3.39, 5.55] |

| Dibutyl (DBP) | Mono-n-butyl (MnBP) | 0.4 | 1.0 or 2.0 | 92.1 | 6.36 [5.76, 7.01] | 6.07 [5.44, 6.77] | 7.72 [6.17, 9.67] |

| Di-isobutyl (DIBP) | Mono-isobutyl (MiBP) | 0.2 | 0.2 | 97.0 | 3.97 [3.59, 4.38] | 3.88 [3.48, 4.32] | 4.37 [3.43, 5.56] |

| Di-n-octyl (DNOP) | Mono-3-carboxy-propyl (MCPP) | 0.2 | 1.0 | 72.8 | 1.93 [1.73, 2.15] | 1.90 [1.68, 2.14] | 2.07 [1.61, 2.66] |

CDC=Centers for Disease Control

UW= University of Washington Environmental Health Laboratory

∑DEHP= (MEHP*(1/278))+(MEHHP*(1/294)) + (MEOHP*(1/292)) + (MECPP*(1/308)) × 1000 (nmol/L).

Multivariable models-boys

In multivariable models examining all mother-son dyads, there were no associations between stress and genital measurements (Table 3). When we included phthalates in those models, we observed significant associations between maternal DEHP metabolite concentrations and AGD measurements, similar to those reported in a previous paper on this cohort that did not consider stress (Table 4, “overall” estimates)16.

Table 3.

Linear regression coefficients and p-values for models examining the association between first trimester life events stressors (any/none) and genital measurements in newborns1.

| Boys (n=366) | Girls (n=372) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGD-AS | AGD-AP | PW | AGD-AS | AGD-AP | |

| 1st trimester life events stress2 | 0.03 (0.95) | −0.43 (0.47) | 0.06 (0.70) | 0.30 (0.44) | −0.20 (0.68) |

Adjusting for gestational age, weight-for-length z-score, infant age at exam, study center, and mother’s age.

Phthalates are not included in these models.

Reference group= no life events stressors

Table 4.

Regression phthalate metabolite coefficients [with 95% CIs] of minimally adjusted models predicting genital measurements in newborn boys (n=366) and girls (n=372) by stress groupa,b.

| Boys | Girls | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress group |

AGD-AS | Pintc | AGD-AP | Pintc | PW | Pintc | AGD-AF | Pintc | AGD-AC | Pintc | |

| ln(∑DEHP) | Overall | −1.26 [−2.38, −0.15] | −1.35 [−2.65, −0.05] | −0.30 [−0.64, 0.03] | 0.29 [−0.54, 1.13] | −0.34 [−1.40, 0.72] | |||||

| Lower | −1.78 [−2.97, −0.59] | −1.61 [−3.01, −0.22] | −0.35 [−0.71, 0.01] | 0.27 [−0.63, 1.17] | −0.42 [−1.56,0.73] | ||||||

| Higher | 1.62 [−1.09, 4.34] | 0.02 | 0.15 [−3.03, 3.33] | 0.31 | −0.02 [−0.84, 0.80] | 0.46 | 0.43 [−1.70, 2.55] | 0.89 | 0.09 [−2.60,2.77] | 0.73 | |

| ln(MEHP) | Overall | −1.14 [−2.18, −0.11] | −1.21 [−2.41, 0.00] | −0.25 [−0.56, 0.06] | 0.05 [−0.68, 0.78] | −0.15 [−1.07,0.78] | |||||

| Lower | −1.36 [−2.47, −0.25] | −1.30 [−2.60, −0.01] | −0.28 [−0.61, 0.05] | −0.03 [−0.81,0.76] | −0.16 [−1.14, 0.83] | ||||||

| Higher | 0.09 [−2.47, 2.66] | 0.30 | −0.65 [−3.64, 2.34] | 0.69 | −0.09 [−0.86, 0.68] | 0.65 | 0.57 [−1.42,2.55] | 0.96 | −0.08 [−2.59, 2.43] | 0.58 | |

| ln(MEOHP) | Overall | −1.44 [−2.48, −0.40] | −1.60 [−2.81, −0.38] | −0.25 [−0.57, 0.06] | 0.33 [−0.47, 1.13] | 0.01 [−1.01, 1.02] | |||||

| Lower | −1.95 [−3.05, −0.84] | −1.91 [−3.21, −0.62] | −0.28 [−0.61, 0.05] | 0.17 [−0.67,1.02] | −0.10 [−1.17, 0.98] | ||||||

| Higher | 1.58 [−0.97, 4.13] | 0.01 | 0.29 [−2.70, 3.28] | 0.17 | −0.09 [−0.86, 0.68] | 0.65 | 1.48 [−1.71,3.67] | 0.27 | 0.72 [−2.05, 3.49] | 0.59 | |

| ln(MEHHP) | Overall | −1.47 [−2.62, −0.31] | −1.29 [−2.28, −0.29] | −0.23 [−0.53, 0.07] | 0.27 [−0.51, 1.04] | −0.30 [−1.29, 0.68] | |||||

| Lower | −1.78 [−2.84, −0.72] | −1.72 [−2.97, −0.48] | −0.23 [−0.55, 0.09] | 0.22[−0.63,1.07] | −0.41 [−1.49, 0.66] | ||||||

| Higher | 1.65 [−0.79, 4.09] | 0.01 | 0.05 [−2.80, 2.90] | 0.28 | 0.01 [−0.72, 0.74] | 0.99 | 0.50 [−1.37,2.36] | 0.79 | 0.26 [−2.09, 2.62] | 0.61 | |

| ln(MECPP) | Overall | −0.97 [−2.09, 0.16] | −0.94 [−2.26, 0.37] | −0.32 [−0.66, 0.01] | 0.26 [−0.51, 1.03] | −0.44 [−1.41, 0.54] | |||||

| Lower | −1.47 [−2.69, −0.26] | −1.24 [−2.66, 0.19] | −0.42 [−0.79, −0.06] | 0.34 [−0.50,1.17] | −0.54 [−1.60, 0.52] | ||||||

| Higher | 1.68 [−1.03, 4.39] | 0.04 | 0.58 [−2.59, 3.75] | 0.30 | 0.22 [−0.06, 1.03] | 0.15 | −0.14 [−2.03,1.75] | 0.65 | −0.08 [−2.30, 2.46] | 0.64 | |

| ln(MnBP) | Overall | −0.95 [−2.05, 0.15] | −0.73 [−2.02, 0.55] | −0.01 [−0.35, 0.32] | 0.00 [−1.07, 1.07] | 0.67 [−0.17, 1.51] | |||||

| Lower | −1.17 [−2.36, −0.01] | −1.06 [−2.44, 0.32] | −0.06 [−0.41, 0.30] | −0.14 [−1.27,0.99] | 0.59 [−0.30, 1.47] | ||||||

| Higher | 0.32 [−2.36, 2.99] | 0.31 | 1.14 [−1.98, 4.25] | 0.20 | 0.23 [−0.57, 1.03] | 0.51 | 0.90 [−1.71,3.52] | 0.57 | 1.22 [−0.85, 3.28] | 0.46 | |

| ln(MEP) | Overall | −0.34 [−1.05, 0.37] | 0.00 [−0.83, 0.83] | −0.12 [−0.33, 0.10] | 0.02 [−0.49, 0.53] | 0.19 [−0.45, 0.84] | |||||

| Lower | −0.17 [−0.94, 0.61] | −0.14 [−1.05, 0.77] | −0.18 [−0.41, 0.05] | 0.28 [−0.29,0.85] | 0.13 [−0.59, 0.86] | ||||||

| Higher | −1.14 [−2.83, 0.54] | 0.30 | 0.65 [−1.31, 2.61] | 0.47 | 0.20 [−0.30, 0.70] | 0.18 | −0.81 [−1.80,0.17] | 0.05 | 0.39 [−0.86, 1.64] | 0.72 | |

| ln(MBzP) | Overall | 0.15 [−0.80, 1.10] | 0.39 [−0.71, 1.49] | 0.00 [−0.28, 0.29] | 0.42 [−0.28, 1.11] | 0.27 [−0.61, 1.14] | |||||

| Lower | 0.04 [−1.00, 1.08] | 0.03 [−1.18, 1.23] | −0.06 [−0.37, 0.24] | 0.28 [−0.36,1.11] | 0.07 [−0.86, 1.00] | ||||||

| Higher | 0.62 [−1.37, 2.61] | 0.60 | 1.89 [−0.42, 4.20] | 0.15 | 0.28 [−0.31, 0.88] | 0.29 | 0.66 [−1.02,2.34] | 0.76 | 1.45 [−0.67, 3.57] | 0.23 | |

| ln(MiBP) | Overall | −0.52 [−1.72, 0.68] | −0.48 [−1.87, 0.92] | −0.05 [−0.41, 0.30] | −0.23 [−1.02, 0.57] | −0.60 [−1.61, 0.41] | |||||

| Lower | −0.79 [−2.12, 0.54] | −0.79 [−2.34, 0.75] | −0.01 [−0.41, 0.39] | −0.28 [−1.15,0.60] | −0.57 [−1.68, 0.54] | ||||||

| Higher | 0.61 [−2.07, 3.29] | 0.36 | 0.85 [−2.27, 3.97] | 0.35 | −0.24 [−1.04, 0.57] | 0.62 | −0.02 [−1.73,1.69] | 0.79 | −0.72 [−2.88, 1.43] | 0.90 | |

| ln(MCPP) | Overall | 0.18 [−0.58, 0.95] | 0.32 [−0.56, 1.21] | −0.10 [−0.33, 0.13] | −0.09 [−0.62, 0.43] | −0.42 [−1.08, 0.24] | |||||

| Lower | 0.03 [−0.80, 0.86] | 0.40 [−0.56, 1.37] | −0.07 [−0.32, 0.18] | −0.07 [−0.65,0.52] | −0.57 [−1.3, 0.17] | ||||||

| Higher | 0.97 [−0.86, 2.97] | 0.35 | −0.07 [−2.19, 2.05] | 0.69 | −0.23 [−0.78, 0.31] | 0.59 | −0.21 [−1.40,0.98] | 0.83 | 0.22 [−1.28, 1.72] | 0.36 | |

Overall estimates are from models adjusted for infant age at exam, gestational age at birth, study center, weight-for-length z-score, specific gravity, time of day of urine collection, maternal age, maternal race (white/non-white), and maternal first trimester life events stress (any/none). Stress-group specific estimates and interaction p-values are from models including the interaction between stress and ln-metabolite concentration with adjustment for the same set of covariates.

Confidence intervals that do not contain the null are bolded.

Pint= interaction p-value based on re-parameterized models.

In interactive models (which allowed the slope of the association between phthalate metabolite concentrations and AGD measurements to vary by maternal stress), associations between maternal phthalate metabolite concentrations and boys’ AGD measurements differed between the lower and higher stress groups (Table 4). In models predicting AGD-AS, the differences in slope between the stress groups were statistically significant for ∑DEHP, MEOHP, MEHHP and MECPP, although not MEHP. No significant interactions were observedin AGD-AS models focused on other phthalate metabolites, nor in models predicting AGD-AP or PW.

Examining the stress-group specific slopes, among lower stress mothers of boys, ∑DEHP was strongly associated with AGD-AS (β=−1.78; 95% CI: −2.97, −0.59) and AGD-AP (β=−1.61; 95% CI: −3.01, −0.22) (Table 4; Figure 1). Similar associations were observed among lower stress mother-son dyads for all of the individual DEHP metabolites measured. In the lower stress group, maternal MnBP was associated with shorter AGD-AS (β=−1.17; 95% CI: −2.36, −0.01) and MECPP was associated with smaller penile width (β=−0.42; 95% CI: −0.79, −0.06). By contrast, among higher stress mother-son dyads, associations between ∑DEHP and AGD were typically positive and non-significant (Table 4). This pattern was true of all individual DEHP metabolites as well, with the exception of MEHP, where the coefficient was negative, but not statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Estimate of the association between first trimester phthalate metabolite concentration and infant male AGD, stratified by prenatal exposure to stressful life events. Black bars represent the “higher” stress group and open bars represent the “lower” stress group.

Multivariable models-girls

In multivariable models examining mother-daughters dyads, looking at the entire cohort, AGD measurements in girls were not associated with any maternal phthalate metabolite concentrations (Table 4). In interaction models, the only significant interaction was for the model examining female AGD-AF and maternal MEP concentrations (p=0.05). In general, maternal phthalate metabolite concentrations were not associated with daughters’ genital measurements in either group (Table 4).

In both boys and girls, results for our multivariable analyses were unchanged when we included number of SLEs as an ordinal, rather than binary, variable (not shown). In sensitivity analyses limited to infants measured at one week of age or younger (n=302 boys, 321 girls), associations were similar, but somewhat weaker; for instance, in the lower stress group, (log)molar sum DEHP was more strongly related to AGD-AS when infants measured at all ages were considered (β=−1.61), as compared to when only the infants measured at age one week or younger were considered (β=−1.34). As in the main analyses, significant associations were only observed in lower stress mother-son dyads, with no associations seen in higher stress boys or in girls (not shown).

Discussion

Numerous studies have reported associations between prenatal phthalate exposure and altered genital development in boys13, 14, 16. Our findings suggest that these associations may be modified by prenatal exposure to SLEs. Associations between maternal first trimester DEHP metabolite concentrations and altered genital measurements (shorter AGD and smaller PW) were observed only in lower stress group. Among sons of higher stress mothers, there were no significant associations between phthalate concentrations and AGD or PW. Prenatal exposure to stress and phthalates may interact to affect the developing male reproductive system in unexpected ways that have not been studied previously. By contrast, maternal phthalate concentrations were not associated with genital development in infant females regardless of the mothers’ exposure to SLEs during early pregnancy.

These results are similar to findings from SFF, our previous, smaller pregnancy cohort, in which associations between prenatal phthalates and AGD were also limited to boys from lower stress families26. In SFF, among boys born into “lower stress” households, the strength of the associations between maternal DEHP metabolite concentrations and son’s AGD were roughly equivalent to those in the current study (although somewhat stronger for AGD-AP). In SFF we also observed main effects of prenatal stress on sex-dependent outcomes in girls. More specifically, prenatal exposure to SLEs was associated with masculinization of female offspring including longer AGD and masculinized play behavior17, 27. In SFF boys, prenatal stress was weakly and non-significantly associated with less masculine AGD and play behavior. In TIDES, we did not observe main effects of prenatal stress on AGD in either sex, despite the larger sample size (Table 3). The reason for this discrepancy is unclear, although in SFF, associations were strongest when we created a composite of maternal and paternal stress17. We did not measure paternal stress in TIDES, but it could be important to consider in future work and it is possible that paternal stress may be conveyed to offspring epigenetically28.

The mechanisms underlying our surprising results are unclear. One possibility is that prenatal stress may counteract or mask phthalate-induced suppression of testicular testosterone production during the critical MPW29. A glucocorticoid-based mechanism is most obvious given that prenatal stress increases maternal cortisol, which may then swamp the placental barrier enzyme 11-β-HSD-2 to reach the fetus and alter physiology30. In rodents, the critical period during which prenatal glucocorticoid exposure disrupts fetal development overlaps with the MPW31 and some research suggests that stressors occurring during the MPW can alter hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis activity32. It is also possible that prenatal stress may act on adrenal androgen pathways. Adrenal androgen production is stimulated by corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) starting in the first trimester. Hyperstimulation of this pathway, as in CAH, can masculinize development in girls3. If prenatal stress upregulates CRH and/or ACTH production, stimulating fetal adrenal androgen activity, the increased adrenal androgen production might “compensate” for phthalate-induced testicular androgen suppression. Adrenal androgens are weaker than testicular androgens, nonetheless, this mechanism might explain the lack of association between phthalate exposure and AGD among highly stressed mother-son dyads. This model also fits with a lack of a main effect of stress on AGD given that under “normal” circumstances with low exposure, adrenal androgens are negligible compared to testicular contributions in males. This mechanism also predicts that daughters of highly stressed mothers would have longer, androgenized AGD, however we did not observe that in TIDES, in contrast to our previous work17.

The question of how multiple exposures interact to shape health is a particularly salient one in the modern environment, given the complex mixture of exposures experienced throughout the life course. Our study further demonstrates the importance of considering these exposures jointly, and further suggests that the effects of chemical exposures on health outcomes may vary depending on the larger biopsychosocial context. As evidence mounts that AGD predicts adult reproductive health, it will be important to better understand factors contributing to variation in AGD and the extent to which AGD is stable over time.

Among TIDES’ strengths is its large size, which allowed us to examine stress-phthalate interactions. Our study design was carefully developed to facilitate precision of exposure and outcome measurement. For instance, because the critical window for male reproductive development occurs during the late first trimester7, we collected first trimester urine samples (for phthalate metabolite analysis) at a mean gestational age of 11 weeks and asked about SLEs occurring during this period. Measurement of our outcomes, AGD and PW, was similarly rigorous24. Finally, our population, while obviously not nationally representative, was similar to pregnant women who participated in previous cycles of NHANES, suggesting that our results may be generalizable. Phthalate metabolite concentrations were lower than those measured in the most recent cycle of NHANES, consistent with a trend towards decreases in many phthalate metabolite concentrations over the last decade33. Despite the low levels of exposure, associations between phthalate exposure and AGD were observed in lower stress mother-son dyads. It is worth noting that alterations in AGD were subtle, perhaps due to the low levels of phthalate exposure among TIDES mothers. For instance, among lower stress families, a one unit increase in ln∑DEHP corresponds to a 4% change in AGD-AS for an average boy.

Arguably the most important limitation of this work is our stress assessment, based on a SLE questionnaire. We did not capture subjective experiences of SLEs, however the same SLE might affect women in very different ways. Similarly, there are numerous measures of stress and related constructs including anxiety, depression, daily hassles, and pregnancy-specific distress, which are more nuanced than our brief questionnaire. Women classified here as lower stress (based on no SLEs reported) may have nevertheless led very stressful lives. Future work should consider daily hassles, cumulative stress, and maternal anxiety as well as biological measures of stress, such as diurnal cortisol profiles or allostatic load. There could have also been some misclassification of timing of exposure, since the question on SLEs occurring in each trimester was asked in the third trimester. In the future, items regarding stress should be asked in each trimester to minimize the potential for misclassification. In addition, phthalate metabolites were only measured in a single first trimester urine sample, which may not reflect levels throughout the MPW. Finally, we considered several other variables that could explain our results, including race, socioeconomic status, and infant body size. After adjusting for these factors, the interactions between phthalate exposure and stress on infant male AGD remained, however there could be residual confounding or additional, important underlying factors that were not measured. It is also possible we did not adequately capture growth-related change in AGD in infants whose exams were delayed after birth, despite including age at exam as a covariate.

Our results are a first indication that in humans, prenatal stress may modify the effects of phthalate exposure on reproductive development in boys. Associations between first trimester phthalate exposure and shortened AGD were limited to boys born to mothers who reported no first trimester SLEs. No associations were observed in boys born to mothers who experienced one or more first trimester SLEs, or in girls. Additional work is needed to understand the possible mechanisms by which prenatal stress may act on the developing reproductive system alone or in combination with phthalates.

Acknowledgements

We thank the TIDES Study Team for their contributions. Coordinating Center: Fan Liu, Erica Scher; UCSF: Marina Stasenko, Erin Ayash, Melissa Schirmer, Jason Farrell, Mari-Paule Thiet, Laurence Baskin; UMN: Heather L. Gray Chelsea Georgesen, Brooke J. Rody, Carrie A. Terrell, Kapilmeet Kaur; URMC: Erin Brantley, Heather Fiore, Lynda Kochman, Jessica Marino, William Hulbert, Robert Mevorach, Eva Pressman; UW/SCH: Richard Grady, Kristy Ivicek, Bobbie Salveson, Garry Alcedo; and the families who participated in the study. In addition, we thank Antonia Calafat (Centers for Disease Control) for urinary phthalate metabolite analyses, Dr Sally Thurston (URMC) for statistical advice, the TIDES families for their participation, and the residents at URMC and UCSF who assisted in birth exams. Funding for TIDES was provided by the following grants from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences: R01ES016863-04 and R01 ES016863-02S4. Funding for the current analysis was provided by K12ES019852-01.

Works cited

- 1.Reyes FI, Winter JS, Faiman C. Studies on human sexual development. I. Fetal gonadal and adrenal sex steroids. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1973;37:74–78. doi: 10.1210/jcem-37-1-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gore AC, Martien KM, Gagnidze K, Pfaff D. Implications of prenatal steroid perturbations for neurodevelopment, behavior, and autism. Endocrine Reviews. 2014;35:961–991. doi: 10.1210/er.2013-1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bongiovanni AM, Root AW. The adrenogenital syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine. 1963;268:1283–1289. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196306062682308. contd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray LE, Ostby J, Furr J, Wolf CJ, Lambright C, Parks L, et al. Effects of environmental antiandrogens on reproductive development in experimental animals. Human Reproduction Update. 2001;7:248–264. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.3.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fowler PA, Bhattacharya S, Flannigan S, Drake AJ, O'Shaughnessy PJ. Maternal cigarette smoking and effects on androgen action in male offspring: unexpected effects on second-trimester anogenital distance. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;96:E1502–E1506. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dean A, Sharpe RM. Clinical review: Anogenital distance or digit length ratio as measures of fetal androgen exposure: relationship to male reproductive development and its disorders. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013;98:2230–2238. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-4057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Welsh M, Saunders PT, Fisken M, Scott HM, Hutchison GR, Smith LB, et al. Identification in rats of a programming window for reproductive tract masculinization, disruption of which leads to hypospadias and cryptorchidism. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008;118:1479–1490. doi: 10.1172/JCI34241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hotchkiss AK, Lambright CS, Ostby JS, Parks-Saldutti L, Vandenbergh JG, Gray LE., Jr Prenatal testosterone exposure permanently masculinizes anogenital distance, nipple development, and reproductive tract morphology in female Sprague-Dawley rats. Toxicological Sciences. 2007;96:335–345. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendiola J, Stahlhut RW, Jorgensen N, Liu F, Swan SH. Shorter anogenital distance predicts poorer semen quality in young men in Rochester, New York. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2011;119:958–963. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisenberg ML, Hsieh MH, Walters RC, Krasnow R, Lipshultz LI. The relationship between anogenital distance, fatherhood, and fertility in adult men. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mendiola J, Roca M, Minguez-Alarcon L, Mira-Escolano M-P, Lopez-Espin JJ, Barrett ES, et al. Anogenital distance is related to ovarian follicular number in young Spanish women: a cross-sectional study. Environmental Health. 2012;11:90. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-11-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mira-Escolano MP, Mendiola J, Minguez-Alarcon L, Melgarejo M, Cutillas-Tolin A, Roca M, et al. Longer anogenital distance is associated with higher testosterone levels in women: a cross-sectional study. BJOG. 2014;121:1359–1364. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swan SH. Environmental phthalate exposure in relation to reproductive outcomes and other health endpoints in humans. Environmental Research. 2008;108:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bornehag CG, Carlstedt F, Jonsson BA, Lindh CH, Jensen TK, Bodin A, et al. Prenatal Phthalate Exposures and Anogenital Distance in Swedish Boys. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2014 doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva MJ, Barr DB, Reidy JA, Malek NA, Hodge CC, Caudill SP, et al. Urinary levels of seven phthalate metabolites in the U.S. population from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2000. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2004;112:331–338. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swan SH, Sathyanarayana S, Barrett ES, Janssen SJ, Liu F, Nguyen RHN, et al. First-trimester phthalate exposure is linked to shorter anogenital distance in newborn boys. Human Reproduction. 2015 doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu363. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrett ES, Parlett LE, Sathyanarayana S, Liu F, Redmon JB, Wang C, et al. Prenatal exposure to stressful life events is associated with masculinized anogenital distance (AGD) in female infants. Physiology and Behavior. 2013;114–115:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barrett ES, Swan SH. Stress and Androgen Activity During Fetal Development. Endocrinology. 2015:en20151335. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1967;11:213–218. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dohrenwend BS, Krasnoff L, Askenasy AR, Dohrenwend BP. Exemplification of a method for scaling life events: the Peri Life Events Scale. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1978;19:205–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gollenberg AL, Liu F, Brazil C, Drobnis EZ, Guzick D, Overstreet JW, et al. Semen quality in fertile men in relation to psychosocial stress. Fertility and Sterility. 2010;93:1104–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva MJ, Samandar E, Preau JL, Jr, Reidy JA, Needham LL, Calafat AM. Quantification of 22 phthalate metabolites in human urine. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2007;860:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hornung R, Reed L. Estimation of average concentration in the presence of nondetectable values. Applied Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. 1990;5:46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sathyanarayana S, Grady R, Redmon JB, Ivicek K, Barrett E, Janssen SJ, et al. Anogenital distance and penile width measurements in The Infant Development and the Environment Study (TIDES): Methods and Predictors. Journal of Pediatric Urology. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.11.018. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boeniger MF, Lowry LK, Rosenberg J. Interpretation of urine results used to assess chemical exposure with emphasis on creatinine adjustments: a review. American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. 1993;54:615–627. doi: 10.1080/15298669391355134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barrett ES, Swan SH. Stress and androgen activity during fetal development. Endocrinology. 2015;156 doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1335. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barrett ES, Redmon JB, Wang C, Sparks A, Swan SH. Exposure to prenatal life events stress is associated with masculinized play behavior in girls. Neurotoxicology. 2014;41C:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bale TL. Lifetime stress experience: transgenerational epigenetics and germ cell programming. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2014;16:297–305. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.3/tbale. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson VS, Blystone CR, Hotchkiss AK, Rider CV, Gray LE., Jr Diverse mechanisms of anti-androgen action: impact on male rat reproductive tract development. International Journal of Andrology. 2008;31:178–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Donnell KJ, Bugge Jensen A, Freeman L, Khalife N, O'Connor TG, Glover V. Maternal prenatal anxiety and downregulation of placental 11beta-HSD2. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:818–826. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nyirenda MJ, Lindsay RS, Kenyon CJ, Burchell A, Seckl JR. Glucocorticoid exposure in late gestation permanently programs rat hepatic phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and glucocorticoid receptor expression and causes glucose intolerance in adult offspring. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1998;101:2174–2181. doi: 10.1172/JCI1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerardin DC, Pereira OC, Kempinas WG, Florio JC, Moreira EG, Bernardi MM. Sexual behavior, neuroendocrine, and neurochemical aspects in male rats exposed prenatally to stress. Physiology and Behavior. 2005;84:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zota AR, Calafat AM, Woodruff TJ. Temporal trends in phthalate exposures: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001–2010. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2014;122:235–241. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1306681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]