Abstract

Aims

To estimate relationships of tobacco outlet density, cigarette sales without ID checks, and local enforcement of underage tobacco laws with youth’s lifetime cigarette smoking, perceived availability of tobacco and perceived enforcement of underage tobacco laws and changes over time.

Design

The study involved: (a) three annual telephone surveys, (b) two annual purchase surveys in 2,000 tobacco outlets, and (c) interviews with key informants from local law enforcement agencies. Analyses were multilevel models (city, individual, time).

Setting

A sample of 50 mid-sized non-contiguous cities in California, USA.

Participants

1,478 youths (aged 13–16 at Wave 1, 52.2% male). 1,061 participated in all waves.

Measurements

Measures at the individual-level included lifetime cigarette smoking, perceived availability, and perceived enforcement. City-level measures included tobacco outlet density, cigarette sales without ID checks, and compliance checks.

Findings

Outlet density was positively associated with lifetime smoking (OR=1.12, p<.01). An interaction between outlet density and wave (OR=0.96, p<.05) suggested that higher density was more closely associated with lifetime smoking at the earlier waves when respondents were younger. Greater density was positively associated with perceived availability (β=0.02, p<.05) and negatively associated with perceived enforcement (β=−0.02, p<.01). Sales rate without checking IDs was related to greater perceived availability (β=0.01, p<.01) and less perceived enforcement (β=−0.01, p<.01). Enforcement of underage tobacco laws was positively related to perceived enforcement (β=0.06, p<.05).

Conclusions

Higher tobacco outlet density may contribute to lifetime smoking among youths. Density, sales without ID checks and enforcement levels may influence beliefs about access to cigarettes and enforcement of underage tobacco sales laws.

Keywords: youths, cigarette smoking, tobacco-related beliefs, tobacco outlet density, retailer non-compliance, enforcement

Introduction

Smoking in adolescence is related to a range of short- and long-term health problems, including a higher risk for tobacco dependence in adulthood, increased number and severity of respiratory illnesses, decreased fitness, and potential retardation of lung growth (1). In the U.S. in 2013, 16.3% of high school seniors (≈17–18 years old), 9.1% of 10th graders (≈15–16 years old), and 4.5% of 8th graders (≈13–14 years old) reported smoking cigarettes in the past 30 days (2). Although these rates are well below the peak smoking levels reported in the 1990s, smoking by young people remains a serious public health issue. Because nearly two-thirds of adult smokers begin daily smoking before age 18 (3–5), it is imperative to develop effective interventions to prevent and reduce smoking by young people.

Environmental approaches to reduce youths’ access to tobacco, such as controlling outlet density, improving retailer compliance with underage sales laws, and enforcing underage tobacco laws may be important strategies for preventing and reducing smoking by young people (6). The overall goal of this paper is to investigate the longitudinal relationships of these community-level factors with youths’ cigarette smoking and beliefs. A number of cross-sectional studies have examined the associations between tobacco outlet density and youths’ cigarette smoking. Results of these studies, however, are mixed. Some studies have shown positive associations (7–12), whereas others have found no or small relationships (13–17). In addition, no longitudinal studies have investigated if tobacco outlet density is related to youths’ smoking over time.

Reducing sales of tobacco products to underage youths is a common approach of numerous community interventions targeting adolescents’ smoking. Many studies have found that enforcement of underage sales laws through compliance checks is associated with decreased rates of tobacco sales to youths (18, 19). Similarly, programs that reinforce retailers for not selling tobacco products to minors have been shown to be effective in increasing ID checking rates (20). The effect of reduced underage sales on youths’ cigarette smoking, however, remains inconclusive. Some studies have found that higher compliance rates were related to lower levels of youths’ smoking (21–24). Others have reported no relationship (25–27).

Although a key purpose of policies targeting youths’ access to tobacco is to reduce smoking, it is important also to consider if such policies are associated with adolescents’ tobacco-related beliefs. A central assumption of cognitive social-learning approaches to understanding behavior is that human actions, including smoking, are the result of an individual’s beliefs about the relative costs and benefits associated with them (28, 29). Within this framework, costs include not only anticipated social and physical consequences (e.g., getting into trouble with police or parents) and economic costs (i.e., price), but also the opportunity costs (e.g., effort) associated with a behavior. From this perspective, adolescents’ beliefs relating to the ease of access to tobacco products and to enforcement of underage tobacco laws may be particularly important in their decision to smoke. To date, there are conflicting study results linking tobacco compliance checks to decreases in perceived access to tobacco (30). Moreover, few studies, if any, have investigated whether outlet density and levels of enforcement are related to such beliefs.

Going beyond previous research, the goals of this longitudinal study are to examine the relations of retail access measures, including tobacco outlet density, cigarette sales without ID checks, and local enforcement of underage tobacco laws with youths’ (a) lifetime cigarette smoking, (b) perceived ease of access to tobacco, and (c) perceived enforcement of underage tobacco laws. We examined interactions between the retail access measures and time to assess changes in these relationships over time.

Methods

Overview

The study involved three data collection activities undertaken in a geographically representative sample of 50 mid-sized non-contiguous California communities: (a) three-wave annual longitudinal telephone survey of adolescents (aged 13–16 at Wave 1), (b) purchase surveys to assess rates of cigarette sales without ID checks, and (c) interviews with representatives from local law enforcement agencies to determine enforcement of underage tobacco sales laws. To determine tobacco outlet density, we obtained data about the number of licensed tobacco retail outlets in each city. Institutional review board approval was obtained prior to study implementation.

Sample of cities

A geographic sampling method was used to select non-contiguous 50 California cities with populations between 50,000 and 500,000. Specifically, a list of all such cities in California was generated. A city was then randomly selected for inclusion and all contiguous cities and cities adjacent to contiguous cites were eliminated. A second city from among those remaining on the list was then randomly selected and contiguous and adjacent cities were eliminated. This process was repeated until a geographically diverse sample of 50 midsized cities was obtained. This sampling procedure is described elsewhere in more detail (9, 31).

Survey

Survey sample

The survey targeted youths aged 13–16 at Wave 1 in the 50 communities. Households within each city were sampled from a purchased list of telephone numbers and addresses. At each wave, an invitation letter describing the study and inviting participation was mailed to sampled households, followed by a telephone contact. Interviewers obtained parental consent for the interviews followed by assent from the youth respondents. Respondents received $25 at Waves 1 and 2 and $35 at Wave 3 as compensation for their participation in the study.

Of 3,062 sampled households with eligible respondents, 1,543 (50.4%) participated in the first interview (Wave 1). Of these, 1,312 participated in the second telephone interview (Wave 2) one year later (85% follow-up) and 1,121 also participated in the third telephone interview (Wave 3) two years after Wave 1 (72% follow-up from Wave 1).

Survey methods

Youths were surveyed using a computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI). The interviews were given in either English or Spanish at the respondent's request and lasted approximately 30–40 minutes. Wave 1 took place in 2009. The current study is based on data from 1,478 youths (52.2% male, M age at Wave 1= 14.6 years, SD =1.0) who (a) participated in at least one wave of data collection, (b) lived in the same city across the study years and (c) provided complete data for all non-varying demographic measures (i.e., age at Wave 1, gender, race and ethnicity). Of the 1,478 youth participants, 1,061 (71.8%) responded to all three waves, 187 (12.7%) responded to two waves and 230 (15.6%) responded to one wave only. An average of 29.6 youths (range: 20–47, SD=5.97) in each city provided data used for the analyses reported here.

Survey Measures

Lifetime cigarette smoking

Respondents to the survey were asked if they ever smoked a whole cigarette in their life, more than just a few puffs (“No”/“Yes”).

Perceived availability of cigarettes

Perceived availability of cigarettes was ascertained by asking: “If you wanted to get cigarettes how easy or difficult would that be for you?” Possible response options were “Very easy,” “Somewhat easy,” “Somewhat difficult,” and “Very difficult.” This item was coded so a higher value represented greater perceived availability of cigarettes.

Perceived enforcement of underage tobacco laws

Three questions were used to measure perceived enforcement of underage tobacco laws. Respondents were asked to indicate how likely they thought it was that a person their age would: (a) get in trouble with the police for having cigarettes, (b) get in trouble with the police if he or she were smoking in public, and (c) get in trouble if he or she tried to buy cigarettes at a store. Response options were, “Very unlikely,” “Somewhat unlikely,” “Somewhat likely,” and “Very likely.” A mean score was computed, with a higher score indicating greater perceived enforcement. The internal reliability (Cronbach’s α) for this scale ranged from 0.76 to 0.90 across the three survey waves.

Demographics

Youth respondents were asked their gender, age, race, and ethnicity. Because too few participants identified with a specific racial group other than white to allow for meaningful analysis, race and ethnicity were treated as dichotomous variables (White versus non-White and Hispanic versus non-Hispanic). Age at Wave 1 was treated as a continuous variable. Because respondents who were 16 years old at Wave 1 were of legal age to purchase tobacco in California at Wave 3 (18 years old), we included a dummy variable indicating whether the respondent was 18 years old at each wave. All respondents had a zero value at Waves 1 and 2 and about 20% of the sample were 18 years old at Wave 3 and were given a value of 1 for that wave.

Tobacco Purchase Surveys

Rates of cigarette sales without ID checks were assessed with purchase surveys conducted in 2011 and 2012 by 8 confederate buyers (4 males and 4 females), who were over age 18, but judged to appear younger by independent panels. At each outlet, a single confederate buyer attempted to purchase a pack of cigarettes. If asked about their age, they stated that they were over 18 years old and if asked for age identification they indicated they had none. If a sale was refused, the buyers left without attempting to pressure the clerk. After leaving the outlet, the buyer documented whether the sale was made. Purchase attempts were made at 1,000 randomly selected tobacco outlets, 20 per community, each year of the purchase survey for a total of 2,000 attempts (31). To obtain a more reliable estimate of sales rates without checking IDs, the overall percentage of outlets that sold a pack of cigarettes in each city across the two waves was calculated (32)

Enforcement Interviews

Between 2010 and 2012, three annual telephone interviews were conducted with key informants from police departments in each of the 50 cities. The interviews asked about enforcement activities focusing on reducing youths’ access to tobacco. Representatives from police departments in 45 of the 50 communities (90%) participated in the first interview, 47 (94%) participated in the second interview and 39 (78%) in the third interview. A representative from all of the 50 police departments participated in at least one interview. Respondents were asked to estimate the number of retail compliance checks their agency conducted in the past year to enforce underage tobacco sales laws. The mean number of compliance checks the agency conducted served as a measure of local enforcement of underage tobacco sales laws. Because this variable was skewed, with 44% of the cities not conducting any compliance checks, it was coded as a dichotomous variable (none versus any compliance checks).

Tobacco Outlet Density

The total number of licensed tobacco retail outlets in each city was obtained from State of California Board of Equalization data files for September 2011. These data files included the total number of licensed tobacco outlets by city and ZIP code, but not outlet names or addresses. Outlet density in each city was calculated as the number of outlets per 10,000 persons.

City Demographics

Measures of city demographics were obtained from 2010 GeoLytics data (33). A community-level socioeconomic status (SES) indicator was derived from median household income, percentage of population with a college education, and percentage of population unemployed. The correlations among these measures ranged from .52 to .79. A principal components analysis yielded a single-factor solution, accounting for 75.1% of the variance (factor loadings range: .78–.91). A factor score was used to represent community SES. Additional city demographics included population density (i.e., population per square mile), percentage of population under 18 years old, percentage White, percentage African American, and percentage Hispanic. These measures were transformed to z-scores.

Data Analysis

We conducted three-level multilevel random effects logistic and linear regression analyses with HLM version 7.0 software (34). Importantly, HLM accommodates missing data points in longitudinal data, allowing the inclusion of all cases in the analyses. Spatial autocorrelation was not a concern in analyses, since the 50 cities were specifically chosen to be non-contiguous. We utilized three models to investigate associations between the retail access measures and each of the outcomes: (1) lifetime cigarette smoking, (2) perceived availability of cigarettes and (3) perceived enforcement of underage tobacco laws. The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) indicated that 0.05%, 0.08% and 1.03% in the variability in lifetime cigarette smoking, perceived availability of cigarettes, and perceived enforcement of underage tobacco policies, respectively, lies between cities. These city-level effects are relatively small but indicate the importance of including cities as a random third-level unit.

In each model, outlet density, rates of tobacco sales without an ID check, enforcement levels, and city demographics were included as city-level variables (Level 3). Gender, age at Wave 1, race and ethnicity were included as individual-level variables (Level 2). A time variable (i.e., survey wave) and the dummy variable indicating whether a respondent was 18 years old were included at the observation-level (Level 1). Intercept coefficients at Levels 2 and 3 were allowed to vary and a random effects term for residual variance was included at Level 1. To examine whether the retail access measures were associated with lifetime smoking and beliefs over time, cross-level interactions between the retail access measures and time were included. The interaction terms were dropped from the model if not statistically significant. Variables in each model were entered simultaneously.

The number of communities and the survey sample size were based on power analyses which took into account the nested design assuming an ICC of .10 and an 82% retention rate between each survey wave. The sampling frame provided 80% power to detect small to moderate effects at the city (δ = .31) and individual (δ = .12) levels.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics for the study variables are in Table 1. The average city-level rate of cigarette sales without ID checks was 10.2% (SD=7.8). This rate is somewhat higher than the Synar non-compliance rates reported by California Department of Public Health in 2011 (5.6%) and 2012 (8.7%) (35). The average number of compliance checks the local enforcement agencies conducted each year ranged from 0 to 8, with 44% of city agencies reporting that they did not conduct any compliance checks. The number of tobacco outlets per 10,000 persons in the 50 cities ranged from 3.32 to 19.18 with a mean of 10.3 (SD=3.3). No statistically significant association was found between outlet density and rates of sales without ID checks (r=0.10).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Variables | % or mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| City level (N=50) | ||

| Retail access | ||

| Sales without ID checks | 10.2 (7.8) | 0.0–32.5 |

| Compliance checks (yes/no) | 56 | 0.0–8.0 |

| Tobacco outlet density (per 10,000 persons) | 10.3 (3.3) | 3.3–19.2 |

| City demographics | ||

| Population density | 4870.1 (3347.5) | 1337.2–22330.2 |

| Percentage age < 18 years | 23.7 (3.2) | 17.0–30.0 |

| Socioeconomic statusa | 0.0 (1.0) | −1.7–1.7 |

| Percentage White | 79.2 (14.5) | 33.5–97.9 |

| Percentage African-American | 5.3 (6.3) | 0.6–33.5 |

| Percentage Hispanic | 34.2 (20.2) | 8.2–97.4 |

| Individual level (N=1,478) | ||

| Age | 14.6 (1.0) | 13.0–16.0 |

| Male | 52.2 | |

| Hispanic | 20.7 | |

| White | 57.8 | |

| Observation level | ||

| Wave 1 (N=1,478) | ||

| Lifetime cigarette smoking | 8.9 | |

| Perceived availability of cigarettesc (N=1,466) | 2.3 (1.1) | 1.0–4.0 |

| Perceived enforcement of underage tobacco lawsc (N=1,477) | 3.8 (0.8) | 1.0–4.0 |

| Wave 2 (N=1,248) | ||

| Lifetime cigarette smoking | 12.7 | |

| Perceived availability of cigarettesc (N=1,240) | 2.6 (1.1) | 1.0–4.0 |

| Perceived enforcement of underage tobacco lawsc | 2.9 (0.8) | 1.0–4.0 |

| Wave 3 (N=1,061) | ||

| Lifetime cigarette smoking | 13.7 | |

| Perceived availability of cigarettesc (N=1,054) | 2.9 (1.1) | 1.0–4.0 |

| Perceived enforcement of underage tobacco lawsc | 2.5 (1.0) | 1.0–4.0 |

Socioeconomic status measured as a factor score derived from: median household income, percentage of population with a college education, and percentage of population unemployed.

Mean (SD) of 1–7 point response scale

Mean (SD) of 1–4 point response scale

Prevalence rates for lifetime cigarette smoking increased as the sample aged (8.9% at Wave 1, 12.7% at Wave 2, and 13.7% at Wave 3). Perceived availability of cigarettes also increased over time and perceived enforcement of underage tobacco laws decreased.

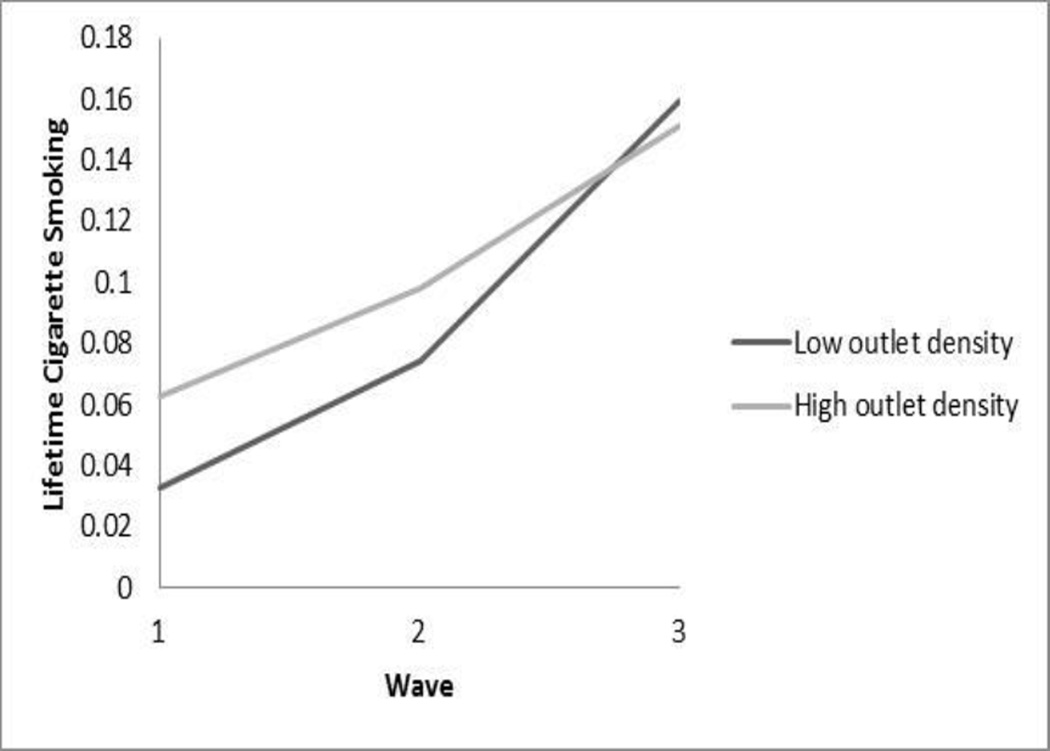

Lifetime cigarette smoking

Results of the multilevel analyses are shown in Table 2. Overall, controlling for individual- and city-level demographics, greater tobacco outlet density was associated with increased likelihood of lifetime smoking. In addition, a significant cross-level interaction was found between outlet density and time. Specifically, at Wave 1, the likelihood of lifetime smoking among youths who lived in cities with greater density of tobacco outlets was higher than that of youths who lived in cities with lower density of tobacco outlets. By Wave 3, however, the likelihood of lifetime smoking of youths in cities with lower tobacco outlet density converged with that of youths who lived in cities with higher tobacco outlet density. Figure 1 shows the regression slopes of wave and lifetime cigarette smoking for high and low levels of tobacco outlet density (25th and 75th percentiles). Neither sales rates nor local enforcement of underage tobacco sales laws were associated with youths’ lifetime smoking. Sensitivity analyses were conducted excluding data from those who were of legal tobacco purchase age in California at Wave 3 (i.e., 18 years old). Results were very similar to those for the complete sample but because of reduced power, the interaction between time and outlet density only approached significance (p=0.09).

Table 2.

Results of multi-level analyses predicting youth cigarette smoking initiation and beliefs over time

| Predictors | Lifetime cigarette smoking OR (95% CIs) |

Perceived cigarette availability Beta (95% CIs) |

Perceived enforcement Beta (95% CIs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| City level (N=50) | |||

| Sales without ID checks | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.02)** | −0.01 (−0.01, –0.01)** |

| Compliance checks | 1.26 (0.83, 1.53) | −0.07 (−0.17, 0.03) | 0.06 (−0.00, 0.12)* |

| Tobacco outlet density | 1.12 (1.04, 1.22)** | 0.02 (−0.00, 0.04)* | −0.02 (−0.04, 0.00)** |

| Time X Sales without ID checks | --- | --- | --- |

| Time X Compliance Checks | --- | --- | --- |

| Time X Outlet density | 0.96 (0.93, 0.99)* | --- | --- |

| Population density | 0.81 (0.69, 0.96)* | −0.15 (−0.25, –0.05)** | 0.10 (0.06, 0.14)** |

| Percentage age < 18 years | 0.96 (0.75, 1.23) | 0.01 (−0.08, 0.09) | −0.00 (−0.06, 0.06) |

| Socioeconomic status | 1.13 (0.91, 1.41) | 0.06 (−0.02, 0.14) | −0.06 (−0.12, 0.00)* |

| Percentage White | 1.12 (0.85, 1.48) | 0.01 (−0.07, 0.09) | 0.05 (−0.01, 0.11) |

| Percentage African-American | 1.13 (0.88, 1.45) | −0.04 (−0.10, 0.02) | 0.07 (0.01, 0.13)* |

| Percentage Hispanic | 1.12 (0.82, 1.53) | 0.05 (−0.07, 0.17) | −0.05 (−0.13, 0.031) |

| Individual level | N=1,478 | N=1,475 | N=1,478 |

| Age | 1.70 (1.44, 2.01)** | 0.33 (0.29, 0.37)** | −0.27 (−0.29, −0.25)** |

| Male | 1.76 (1.31, 2.36)** | 0.09 (0.01, 0.17)* | −0.01 (−0.069, 0.049) |

| Hispanic | 1.38 (0.75, 2.53) | 0.07 (−0.07, 0.21) | 0.02 (−0.10, 0.14) |

| White | 0.79 (0.54, 1.16) | −0.07 (−0.19, 0.05) | −0.02 (−0.10, 0.06) |

| Observation level | N=3,787 | N=3,760 | N=3,786 |

| Survey Wave | 3.04 (2.09, 4.46)** | 0.27 (0.25, 0.29)** | −0.23 (−0.27, −0.19)** |

| Age 18 years | 0.86 (0.60, 1.21) | 0.36 (0.26, 0.46)** | −0.80 (−0.92, −0.68)** |

p<.05;

p<.01

Fig 1.

Lifetime cigarette smoking by survey wave and levels of tobacco outlet density

Tobacco beliefs

Controlling for individual- and city-level demographics, greater tobacco outlet density and rates of sales without ID checks were associated with greater perceived availability of cigarettes and with less perceived enforcement of underage tobacco laws (Table 2). Local enforcement of underage tobacco sales laws was associated with increased perceived enforcement of underage tobacco policies.

Discussion

This study examined the associations of tobacco outlet density, retailer sales rates without ID checks, and enforcement of underage tobacco laws with youths’ lifetime cigarette smoking and tobacco beliefs over three years. Consistent with some other studies (7–11), results showed that tobacco outlet density was associated with smoking among youths. That is, lifetime smoking by adolescents was greater in cities with higher outlet density. This is also consistent with results of another study which found that adolescents who visited tobacco outlets two or more times per week had greater odds of smoking initiation (36). Our results also showed that tobacco outlet density was related to youths’ tobacco beliefs, such that greater density was associated with greater perceived cigarette availability and with lower perceived enforcement of underage tobacco policies. These results suggest that increased exposure to tobacco outlets may affect youth’s beliefs about ease of access to cigarettes and about the likelihood of getting into trouble for smoking or buying cigarettes, as well as their smoking behavior.

Considering tobacco outlet density and lifetime cigarette smoking over time, we found that the likelihood of smoking at Wave 1, when respondents were relatively young (13–16 years old), was greater in communities with higher outlet density compared with youths who lived in cities with lower density of tobacco outlets. Two years later, however, lifetime smoking among youths in cities with lower density of tobacco outlets converged with that of youths who lived in cities with higher tobacco outlet density. These results suggest that higher tobacco outlet density may be associated with smoking among youths at earlier ages. The implications of these results should be considered when implementing interventions that target younger youths, since early smoking initiation is associated with progression to daily smoking, heavier smoking, nicotine dependence in adulthood, and to greater difficulty with smoking cessation (1).

No main effects were found for levels of local enforcement or for retailer sales of cigarettes without ID checks on youths’ lifetime smoking. Rate of sales without ID checks, however, was positively related to youths’ beliefs about the ease of obtaining cigarettes and negatively related to beliefs about enforcement of underage tobacco laws. Conversely, local enforcement was associated with beliefs about enforcement of underage tobacco policies. These findings are important given that these beliefs are associated with, and may be predisposing factors, for youths’ cigarette smoking (37, 38). These findings thus suggest that compliance checks and other programs to increase retailer compliance with underage tobacco sales laws may be of value as well.

The findings from this study have implications for prevention. Living in communities with higher outlet densities was associated with smoking by youths, greater perceived access to cigarettes, and lower levels of perceived enforcement of underage tobacco laws. The relationship between density and smoking was most pronounced at the initial waves of the survey when the participants were younger. Overall, these findings suggest that controls on the numbers and locations of tobacco outlets is a key element in a comprehensive strategy for delaying smoking, especially among younger adolescents. High densities of tobacco outlets may serve a normative function as well, affecting adolescents’ beliefs about the ease of obtaining cigarettes and the likelihood of getting into trouble with authorities for smoking.

Results of this study should be considered in light of some limitations. The study only included mid-sized cities in California. A different pattern of relations might obtain in rural or more urban communities. Also, data about local enforcement were obtained from a single key informant in each community and therefore may not be accurate or may be subject to social desirability biases. The positive association, however, between the reports obtained from the key informants and youths’ perceived enforcement of underage tobacco laws suggests the single source of enforcement information may not have jeopardized study validity. It should be further noted that this study focused on the associations of community-level outlet density, sales without ID checks, and enforcement with youths’ smoking behaviors and beliefs. Considering these factors at smaller geographic units such as the neighborhood level or within youths’ every day activity spaces may further clarify how they relate to smoking beliefs and behaviors (39). Finally, this study did not consider youth’s access to cigarettes outside their city of residence. As youths grow older, they experience increased mobility, through driving or increased use of public transportation, which may moderate any relationship between retail access to cigarettes within city boundaries and youths’ smoking behaviors and beliefs. Future studies should consider youths’ mobility and retail access to cigarettes in the broader environment where they spend their time. Despite these limitations, the current study makes a significant contribution by providing additional evidence regarding the roles that outlet density, enforcement of underage sales laws, and retailer non-compliance may play in youths’ lifetime cigarette smoking and beliefs.

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding: This research and preparation of this manuscript were made possible by grants CA138956 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and AA006282 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and grant 19CA-016 from the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (TRDRP; http://www.trdrp.org). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of NIH, NCI, NIAAA, or TRDRP.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: None

REFERENCES

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2012: Volume I, secondary school students. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. The Path to Smoking Addiction Starts at Very Young Ages. Washington, DC: Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2000–2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;59(33):1063–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friend KB, Lipperman-Kreda S, Grube J. The impact of local U.S. tobacco policies on youth tobacco use: A critical review. Open Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;1:34–43. doi: 10.4236/ojpm.2011.12006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan WC, Leatherdale ST. Tobacco retailer density surrounding schools and youth smoking behaviour: a multi-level analysis. Tobacco Induced Diseases. 2011;9(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-9-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henriksen L, Feighery E, Schleicher N, Cowling D, Kline R, Fortmann S. Is adolescent smoking related to the density and proximity of tobacco outlets and retail cigarette advertising near schools? Preventive Medicine. 2008;47(2):210–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipperman-Kreda S, Grube JW, Friend KB. Local tobacco policy and tobacco outlet density: Associations with youth smoking. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50(6):547–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Novak SP, Reardon SF, Raudenbush SW, Buka SL. Retail tobacco outlet density and youth cigarette smoking: A propensity-modeling approach. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:670–676. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.061622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.West JH, Blumberg EJ, Kelley NJ, Hill L, Sipan CL, Schmitz KE, et al. Does proximity to retailers influence alcohol and tobacco use among Latino adolescents? Journal of Immigrant Minority Health. 2010;12:626–633. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9303-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams ML, Jason LA, Pokorny S, Hunt Y. Exploration of the link between tobacco retailers in school neighborhoods and student smoking. The Journal of school health. 2013;83(2):112–118. doi: 10.1111/josh.12006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leatherdale ST, Strath JM. Tobacco retailer density surrounding schools and cigarette access behaviors among underage smoking students. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;33(1):105–111. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3301_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lovato CY, Hsu HC, Sabiston CM, Hadd V, Nykiforuk CI. Tobacco Point-of-Purchase marketing in school neighbourhoods and school smoking prevalence: A descriptive study. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2007;98(4):265–270. doi: 10.1007/BF03405400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarthy WJ, Mistry R, Lu Y, Patel M, Zheng H, Dietsch B. Density of tobacco retailers near schools: effects on tobacco use among students. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(11):2006–2013. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.145128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pokorny SB, Jason LA, Schoeny ME. The relation of retail tobacco availability on initiation and continued cigarette smoking. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003:193–204. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3202_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loomis BR, Kim AE, Busey AH, Farrelly MC, Willett JG, Juster HR. The density of tobacco retailers and its association with attitudes toward smoking, exposure to point-of-sale tobacco advertising, cigarette purchasing, and smoking among New York youth. Prev Med. 2012;55(5):468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy DT, Friend K, Holder H, Carmona M. Effect of policies directed at youth access to smoking: Results from the SimSmoke computer simulation model. Tobacco Control. 2001;10(2):108–116. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.2.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy DT, Friend KB. Strategies for reducing youth access to tobacco: A framework for understanding empirical findings on youth access policies. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy. 2002;9(3):285–303. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krevor BS, Ponicki WR, Grube JW, DeJong W. The effect of mystery shopper reports on age verification for tobacco purchases. Journal of health communication. 2011;16(8):820–830. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.561912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biglan A, Ary D, Smolkowski K, Duncan T, Black C. A randomised controlled trial of a community intervention to prevent adolescent tobacco use. Tobacco Control. 2000;9(1):24–32. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dent C, Biglan A. Relation between access to tobacco and adolescent smoking. Tobacco Control. 2004;13:334–338. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.004861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher KE. Enforcement of underage sales laws as a predictor of daily smoking among adolescents: A national study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:107. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jason LA, Pokorny SB, Schoeny ME. Evaluating the effects of enforcements and fines on youth smoking. Critical Public Health. 2003;13(1):33–45. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fichtenberg CM, Glantz SA. Youth access interventions do not affect youth smoking. Pediatrics. 2002;109(6):1088–1092. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.6.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rigotti NA, DiFranza JR, Chang YC, Tisdale T, Kemp B, Singer DE. The effect of enforcing tobacco-sales laws on adolescents' access to tobacco and smoking behavior. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337(15):1044. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710093371505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomson CC, Hamilton WL, Siegel MB, Biener L, Rigotti NA. Effects of local youth-access regulations on progression to established smoking among youths in Massachusetts. Tobacco Control. 2007;16:119–126. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.018002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. p. xiii.p. 617. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. New York: Psychology Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stead LF, Lancaster T. Interventions for preventing tobacco sales to minors. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews. 2005:25. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001497.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lipperman-Kreda S, Grube JW, Friend KB. Contextual and community factors associated with youth access to cigarettes through commercial sources. Tobacco Control. 2014;23(1):39–44. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levinson AH, Patnaik JL. A practical way to estimate retail tobacco sales violation rates more accurately. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(11):1952–1955. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.GeoLytics Inc. Estimates Premium 2010. Brunswick, NJ: 2010. [DVD] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raudenbush S, Bryk AYFC, Congdon R, Du Toit M. HLM 7: Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35.California Department of Public Health. Percent of Retailers Selling Tobacco to Youth, 1995–2011. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johns M, Sacks R, Rane M, Kansagra SM. Exposure to tobacco retail outlets and smoking initiation among New York City adolescents. J Urban Health. 2013;90(6):1091–1101. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9810-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lipperman-Kreda S, Grube JW. Students' perception of community disapproval, perceived enforcement of school antismoking policies, personal beliefs, and their cigarette smoking behaviors: Results from a structural equation modeling analysis. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11(5):531. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lipperman-Kreda S, Paschall MJ, Grube JW. Perceived enforcement of school tobacco policy and adolescents’ cigarette smoking. Preventive Medicine. 2009;48:562–566. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lipperman-Kreda S, Morrison C, Grube JW, Gaidus A. Youth activity spaces and daily exposure to tobacco outlets. Health Place. 2015;34:30–33. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]