Abstract

Background

In order to better understand the contribution of frailty to health-related outcomes in the elderly, it seems valuable to explore data from cohort studies across the world in an attempt to establish a comprehensive definition. The purpose of this report is to show the characteristics of frailty and observe its prognosis in a large sample of French community-dwelling elderly.

Methods

We used data from 6,078 persons aged 65 years and older participating in the Three-City Study (3C). Frailty was defined as having at least three of the following criteria: weight loss, weakness, exhaustion, slowness, and low activity. Principal outcomes were incident disability, hospitalization, and death. Multiple covariables were used to test the predictive validity of frailty on these outcomes.

Results

436 individuals (7%) met frailty criteria. Subjects classified as frail were significantly older, more likely to be female, less educated, and reported more chronic diseases, lower income, and poorer self-reported health status in comparison to nonfrail participants. In addition, frailty was significantly associated with 4-year incidence of disability for mobility, activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental ADL. Frailty was also significantly associated with incident hospitalization and death; nevertheless, after adjusting for many potential confounders, frailty was not a statistically significant predictor of mortality.

Conclusions

Frailty is not specific to a subgroup or region in the world. Our study confirms the predictive validity of Fried’s frailty criteria thus suggesting it may be useful in population screening and predicting service needs.

The concept of frailty has emerged as a condition associated with an increased risk of functional decline among the elderly, which may be differentiated from aging, disability and co-morbidity (1). Frailty describes a state of vulnerability to the adverse effects of a variety of environmental stressors, expressed as an increased risk of accumulating health related problems, hospitalization, need for long-term care, and death (2–4).

In order to identify frail individuals, several criteria have been proposed in recent years (3,5–8). According to the criteria used, heterogeneous results regarding frequency have been obtained when applied in clinical practice (9). Nevertheless, there is a general agreement that the core feature of frailty is increased vulnerability due to impairments in multiple, inter-related systems resulting in homeostatic reserve disturbance (3,10–13). Multiple impairments are demonstrated by the presence of a combination of several clinical characteristics, and it seems very unlikely that a single altered system is sufficient to explain this clinical state (1,14). Recently, a definition has been proposed by a working group which conceptualizes frailty as a clinical syndrome defined as the combination of shrinking, weakness, exhaustion, low walking speed and low physical activity (3). This conception of frailty implies a biological connection between all its components and is widely used.

To better understand the role of frailty in health outcomes for different subgroups, it is important to examine data from cohort studies across cultures to assess its ability to predict adverse outcomes in different populations. Therefore, the purpose of this report is to describe the characteristics and prognosis of subjects classified as “frail” in a large sample of French community-dwelling elderly. The main hypothesis is that frail subjects defined according to the criteria derived from Fried’s study present more adverse outcomes such as the incidence of disability, more frequent hospitalization and mortality even after adjustment for potential confounders.

METHODS

Study population

The participants in the present study are a subset from the Three-City Study (3C), a multicenter study aiming to evaluate the risk of dementia and cognitive impairment attributable to vascular factors. The methodology has been previously reported (15). Briefly, it is a 4-year cohort study of 3,650 men and 5,644 women aged 65 and older, initially noninstitutionalized. The sample was drawn from a random sample obtained from the electoral rolls of three French cities -- Bordeaux (southwest), Dijon (central east) and Montpellier (southeast) -- between 1999 and 2000. Two follow-ups have been carried out (2001–2002 and 2003–2004). A wide range of information was collected during face-to-face interviews (using a standardized questionnaire) by trained nurses and psychologists, including socio-demographic characteristics, educational level and lifestyle (smoking, drinking and food intake). The examination included blood pressure, cognitive evaluation and biological parameters. In addition, self-report of chronic diseases, depressive symptoms and functional status were recorded. The 3C Study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University Hospital of Kremlin-Bicêtre, and all participants signed an informed consent.

Definition of frailty

Frailty was defined according to the construct previously validated by Fried et al in the Cardiovascular Health Study (3). All five components from the original phenotype were retained for this study; however, the metrics used to characterize the frailty criteria were slightly different and defined as follows:

Shrinking: Recent and unintentional weight loss of 3 kg or more was identified and body mass index calculated. Subjects who answered “yes” for weight loss or had a body mass index lower than 21 kg/m2 were considered to be frail for this component. This threshold is used in the Mini-Nutritional Assessment (16) and has been shown to be associated with increased mortality (17). In addition, it was previously associated with adverse outcomes in community-dwelling elderly persons in France (18).

Poor endurance and energy: As indicated by self-report of exhaustion, identified by two questions from the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D [(19)]): “I felt that everything I did was an effort” and “I could not get going”. Participants were asked: “How often, in the last week, did you feel this way?” 0 = rarely or none of the time; 1 = some or a little of the time; 2 = a moderate amount of the time; or 3 = most of the time. Participants answering “2” or “3” to either of these questions were considered as frail by the exhaustion.

Slowness: The slowest quintile of the population was defined at baseline, based on timed 6-meter walking test, adjusting for gender and height as recommended. The lowest quintile was used to identify subjects with slowed walking speed.

Weakness: Participants answering “yes” to the following question were categorized as frail for this component: Do you have difficulty rising from a chair? Grip strength, which evaluates the muscular power and force that can be generated with the hands, was not available in the 3C Study dataset. However, a multidisciplinary expert consensus (nutritionist, neurologist, psychologist and geriatrician) determined that the question was an adequate “proxy” for weakness. In addition, it was shown that grip strength significantly correlates with muscular power in other muscle groups among the elderly (elbow flexion, knee extension, trunk extension, and trunk flexion [(20)]).

Low physical activity: A single response was used to estimate physical activity (21). Individuals who denied doing daily leisure activities such as walking or gardening and/or denied doing some sport activity per week were categorized as physically inactive. Those who reported doing them were considered to be physically active.

As proposed by Fried et al, the subjects were considered to be “frail” if they had three or more frailty components among the five criteria; they were considered “prefrail” or “intermediate” if they fulfilled one or two frailty criteria, and “nonfrail” if none (3).

Outcomes

Three measurements of disability were investigated as outcomes: mobility, instrumental (IADL) and basic activities of daily living (ADL). Mobility was assessed by the Rosow & Breslau scale (22): doing heavy housework, walking a half mile, and going up the stairs. For the IADL, participants reported their ability to perform 8 activities of daily living based on the Lawton & Brody scale: using the telephone, having responsibility for one’s own medication, managing money, being able to transport oneself, shopping, grooming, doing housework, and doing laundry (the last three were only asked of women [(23)]). For the ADL, participants were asked if they needed help for any task from the Katz ADL scale (bathing, dressing, transferring from bed to chair, toileting, and feeding [(24)]). For each domain of disability, if participants indicated that they were unable to perform one or more activities without help, according to the threshold defined by the authors of each scale, they were considered as having mobility, IADL or ADL disability (22–24). The four-year incidence of disability was established only among those without prevalent disability in the same domain at baseline.

Four-year incident hospitalization was considered when the participants declared it either at the first follow-up (2 years) or subsequent follow-up interview (4 years). Cause and time of death were obtained from interviews with family or from medical records at both follow-ups, and treated as cumulative 4-year mortality.

Covariables

Sociodemographic variables included age, sex, marital status, educational level, living alone, and monthly income. Participants were asked whether they had a physician’s diagnosis of cardiac failure, myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, fractures during the two preceding years (femoral or vertebral), cancer diagnosis or arthrosis. Participants were considered as hypertensive if self-reported or systolic pressure was ≥ 160 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure was ≥ 95 mmHg or they were on antihypertensive medications. Subjects were considered as diabetics if self-reported or having high glucose level (≥ 7.0 mmol/L) or they were on hypoglycemic treatment (oral diabetic medications or insulin). The presence of each of these diseases was summed up in a score ranging from 0 to 9, where a higher score indicates more chronic diseases. Self-reported health was also recorded and treated as a categorical variable (good, regular or poor).

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the CES-D (20-item version [(25)]). For the multivariate analyses, the two questions used for the frailty definition were excluded from the total CES-D score. This variable was used as continuous and a higher score represents worse mood.

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE [(26)]) was used to assess global cognitive function (0 to 30 points; higher score indicates better cognitive status).

Smoking status (non-smoker, former smoker, current smoker) and usual alcohol intake (non-drinker, former drinker and current drinker) were self-reported.

Plasma cholesterol total levels were used as continuous variable.

Sample

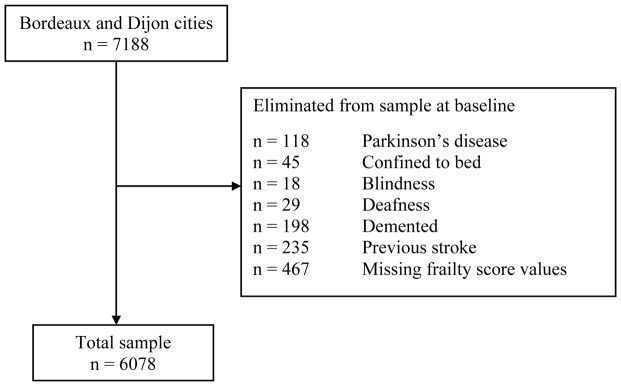

For the present research, only participants from two cities were considered, because in Montpellier, the timed walking test was not given. Moreover, of the 7,188 participants interviewed at baseline in Bordeaux and Dijon, subjects with conditions that could be a consequence of a single disease and not of generalized frailty as already proposed were excluded (3). In addition, in those whose frailty status could not be determined (missing data) were also excluded (Figure 1). Data for 2,354 (38.7%) men and 3,724 (61.3%) women, who had complete clinical and functional data at baseline, were finally included in the statistical analyses as well as their information concerning to the 2- and 4-year follow-ups.

Figure 1.

Assembly of the study sample selected among the 3C Study.

Statistical analysis

Variables were described using arithmetic means and standard deviations (SD) or frequencies and proportions where appropriate. The following statistical procedures were used according to the characteristics of each variable: chi square test for qualitative data or analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous data. Bonferroni’s correction was applied where indicated. In order to determine the predictive validity of frailty definition among this cohort study, separate logistic regression models were used to describe the unadjusted effect of frailty on the 4-year incidence of mobility, IADL and ADL disability and hospitalization. In a second model, multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to study the effect of frailty adjusting for multiple covariables (age, sex, education level, income, smoking status, drinker status, number of chronic diseases, self-reported health, CES-D score and MMSE score). To analyze the incidence of IADL disability, baseline mobility disability was considered. For the analyses of incident ADL disability, baseline mobility and IADL disability were also included. Baseline disability (mobility, IADL and ADL) was also taken into account in the model related to the incidence of hospitalization. Contrary to disability and hospitalization (for which data were obtained only at the time of the follow-ups), for mortality date of death were available and allow thus to determine hazard ratios. Cox proportional hazards model with delayed entry, in which the time-scale was the individuals’ age, was performed to estimate the cumulative risk of death and later was also performed using all variables mentioned above (excepting age), including baseline functional status, with frailty status as the main explanatory variable. All statistical tests were evaluated using a 95% confidence interval (CI), and a p value < .05. Statistical test were performed using the SPSS software for Windows® (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, version 13.0).

RESULTS

The study sample comprised 6,078 individuals. Mean age was 74.1 years (range 65 to 95 years) and 61.3% were females (Table 1). Hypertension, arthrosis, and diabetes were the most frequent chronic diseases, and 29.9% of participants reported 2 or more of the chronic diseases. Forty five percent had disability for mobility, 8.1% for IADL and only 0.4% for ADL at baseline. Disability was higher in women than in men for mobility (52.0% vs. 34.8% respectively; p < .001) and IADL (9.6% vs. 5.9% respectively; p < .001), but for the ADL the difference was not significant (0.3% vs. 0.4% respectively; p =.166). However, in older age (≥ 85 years), the differences between both sexes were statistically significant for the domains of disability (p < .001). Fifty-four percent of participants reported to be completely autonomous for the three domains of disability evaluated.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics and Health Status of Participants with Frailty at Baseline. The 3C Study

| Variable | All n = 6078 |

Nonfrail n = 2756 |

Prefrail n = 2896 |

Frail n = 426 |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 74.1 (5.2) | 73.5 (5.1)a | 74.4 (5.2)b | 76.6 (5.5)c | < .001 |

| Female gender (%) | 61.3 | 57.0 | 63.5 | 77.2 | < .001 |

| High education level (%) (>12 years) | 17.0 | 17.8 | 17.0 | 12.0 | .029 |

| Lives alone (%) | 37.4 | 35.7 | 37.7 | 47.6 | < .001 |

| Monthly income < 780 € (%) | 5.4 | 4.7 | 5.7 | 11.6 | < .001 |

| Poor self-reported health (%) | 4.4 | 1.1 | 5.0 | 21.6 | < .001 |

| High blood pressure (%) | 64.0 | 63.9 | 63.1 | 70.9 | .007 |

| Arthrosis (%) | 14.9 | 11.0 | 17.2 | 26.4 | < .001 |

| Diabetes (%) | 9.3 | 8.9 | 10.1 | 14.7 | .008 |

| Cancer (%) | 5.3 | 5.0 | 5.5 | 6.6 | .350 |

| Chronic diseases, mean (SD) | 1.2 (1.0) | 1.1 (0.9) | 1.3 (1.0) | 1.6 (1.1) | < .001 |

| Current smoker (%) | 5.5 | 4.8 | 6.3 | 4.2 | < .001 |

| Current drinker (%) | 79.2 | 81.4 | 79.3 | 65.7 | < .001 |

| MMSE, mean (SD) | 27.4 (1.9) | 27.5 (1.9)a | 27.4 (1.9)b | 26.9 (2.0)c | < .001 |

| CES-D, mean (SD) | 8.1 (7.4) | 5.6 (5.21)a | 9.3 (7.84)b | 15.7 (9.30)c | < .001 |

| Cholesterol, mmol/L, mean (SD) | 5.81 (1.0) | 5.79 (0.9) | 5.82 (1.0) | 5.85 (1.1) | .356 |

| Disability for mobility (%) | 44.9 | 34.9 | 50.0 | 81.9 | < .001 |

| Disability ≥ 1 IADL task (%) | 8.1 | 4.3 | 8.3 | 32.8 | < .001 |

| Disability ≥ 1 ADL task (%) | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 3.3 | < .001 |

Note: Chronic diseases: hypertension, diabetes, cardiac failure, myocardial infarction or angina pectoris, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, fractures (femoral or vertebral), cancer and arthrosis.

MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination (0–30 points); higher score indicates better cognitive status.

CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (excluding the two questions used for the frailty definition); higher score indicates worse mood status.

IADL = Instrumental activities of daily living (self-reported disability).

ADL = Basic activities of daily living (self-reported disability).

p value represents the global test.

Different letters indicate a statistically significant inter-group difference.

Table 2 presents the percentage for each component of frailty. Frailty was present in 436 (7.0%) individuals. Baseline comparison of demographic and health characteristics according to frailty status are shown in Table 1. As expected, subjects classified as frail were older (p < .001), more likely to be female (p < .001), less educated (p = .029), and reported more chronic diseases (p < .001), lower income (p < .001) and poorer self-reported health status (p < .001) in comparison to prefrail or nonfrail participants. In addition, the frail subgroup had a lower MMSE score (p < .001) and more depressive symptoms (p < .001) compared to the prefrail or nonfrail subgroups. Disability for mobility, IADL and ADL activities at baseline was also significantly more frequent in the prefrail and frail subgroups in comparison to the nonfrail subgroup. Total serum cholesterol total levels were not different between the three subgroups.

Table 2.

Proportions of Frailty Components by Sex in the 3C Study

| All n = 6078 |

Men n = 2354 |

Women n = 3724 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of Frailty Components (%) | |||

| Shrinking | 14.4 | 9.3 | 17.2 |

| Weakness | 12.7 | 9.1 | 14.9 |

| Exhaustion | 18.5 | 13.7 | 21.7 |

| Slowness | 20.8 | 20.6 | 21.0 |

| Low physical activity | 23.3 | 22.8 | 23.7 |

|

|

|||

| Number of Frailty Components (%) | |||

| 0 | 45.3 | 50.6 | 42.0 |

| 1 | 34.9 | 34.9 | 34.5 |

| 2 | 12.7 | 10.2 | 14.3 |

| 3 | 5.6 | 3.4 | 7.0 |

| 4 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 1.5 |

| 5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Total Frail (≥ 3 points) | 7.0% | 4.3% | 8.7% |

Disability

After 4 years, among those without mobility disability at baseline 44.4% of the nonfrail, 54.9% of the prefrail and 68.2% of the frail persons developed mobility disability. Incident IADL disability was 8.0%, 12.6% and 26.4% among nonfrail, prefrail and frail subgroups respectively, whereas incident ADL disability was 0.7%, 1.0% and 2.7% in nonfrail, prefrail and frail participants.

In comparison to the nonfrail subgroup, the prefrail and frail subgroups had significantly higher risk of incident disability for mobility and IADL (Table 3). However, only the frail subgroup was associated with an increased incidence of disability for ADL. Multivariate logistic regression analyses showed that after adjusting for socio-demographic and health covariables, frailty was still significantly associated with the incidence of disability for mobility, IADL and ADL. The prefrail subgroup was even significantly linked to mobility and IADL disability, but to a lesser extent (Table 3).

Table 3.

Incident 4-year Disability by Frailty Status at Baseline. The 3C Study

| Mobility disability n = 3000 |

IADL disability† n = 5029 |

ADL disability‡ n = 5449 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI* | p | p global | Odds Ratio | 95% CI* | p | p global | Odds Ratio | 95% CI* | p | p global | |

| Unadjusted | ||||||||||||

| Frailty | < .001 | .001 | .001 | |||||||||

| Nonfrail (reference) | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | |||

| Prefrail | 1.52 | 1.31–1.76 | < .001 | 1.76 | 1.45–2.13 | < .001 | 1.21 | 0.71–2.07 | .484 | |||

| Frail | 2.68 | 1.58–4.54 | < .001 | 4.10 | 2.96–5.66 | < .001 | 10.76 | 6.30–18.37 | < .001 | |||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Adjusted | ||||||||||||

| Frailty | .002 | < .001 | < .001 | |||||||||

| Nonfrail (reference) | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | |||

| Prefrail | 1.33 | 1.13–1.57 | < .001 | 1.43 | 1.15–1.78 | .001 | 0.80 | 0.47–1.46 | .556 | |||

| Frail | 1.58 | 0.88–2.85 | .131 | 2.10 | 1.41–3.11 | < .001 | 3.20 | 1.57–6.52 | .001 | |||

Note: Adjusted for age, sex, education level, income, smoking status, drinker status, number of chronic diseases, self-reported health, Center for epidemiologic studies-depression scale (excluding the two questions used for the frailty definition), and Mini-mental state examination. For incident IADL disability, odds ratios were also adjusted for baseline mobility disability. For incident ADL disability odds ratios were adjusted for baseline mobility and IADL disability.

CI = Confidence interval.

IADL = Instrumental activities of daily living.

ADL = Basic activities of daily living.

Hospitalization

After 4 years of follow-up, 31.3% of the frail subgroup and 23.8% of prefrail subjects had an incident hospitalization, compared to 20.3% of nonfrail participants.

Prefrail and frail status was significantly associated with the incidence of hospitalization (Table 4). Multivariate logistic regression analyses showed that after adjusting for all covariables mentioned above, including disability for mobility, IADL and ADL at baseline, frailty was still significantly associated to incident hospitalization and prefrail status showed a nonsignificant trend.

Table 4.

Incident 4-year Hospitalization by Frailty Status at Baseline. The 3C Study

| Unadjusted | Hospitalization

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p | p global | |

| Frailty | < .001 | |||

| Nonfrail (reference) | 1 | - | - | |

| Prefrail | 1.18 | 1.04–1.35 | .012 | |

| Frail | 1.69 | 1.32–2.16 | < .001 | |

|

|

||||

| Adjusted | ||||

| Frailty | .051 | |||

| Nonfrail (reference) | 1 | - | - | |

| Prefrail | 1.14 | 0.98–1.31 | .081 | |

| Frail | 1.36 | 1.01–1.81 | .042 | |

Note: Adjusted by age, sex, education level, income, smoking status, drinker status, number of chronic diseases, self-reported health, Center for epidemiologic studies-depression scale (excluding the two questions included in the frailty definition), Mini-mental state examination score, and baseline disability (mobility, instrumental activities of daily living and basic activities of daily living).

Mortality

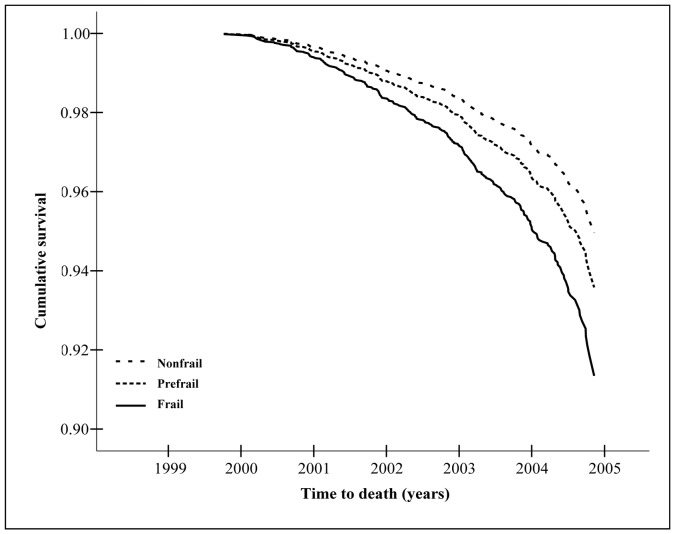

Incidence of death was 5.2% (316) at the 4-year follow-up. Cumulative mortality was 11.5%, 5.5% and 4.4% in frail, prefrail and nonfrail subjects, respectively.

The unadjusted Cox proportional hazard model showed that being frail at baseline significantly increased the risk of cumulative death at 4 years (Table 5 and Figure 2). However, after adjusting for socio-demographic and health covariates including disability for mobility, IADL and ADL at baseline, frailty was no longer a statistically significant predictor of death (Table 5).

Table 5.

Hazard Ratio* of Death Estimates over the 4-year of Follow-Up. The 3C Study

| Unadjusted | Death

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p | p global | |

| Frailty | .048 | |||

| Nonfrail (reference) | 1 | - | - | |

| Prefrail | 1.17 | 0.92–1.50 | .197 | |

| Frail | 1.54 | 1.09–2.17 | .015 | |

|

|

||||

| Adjusted | ||||

| Frailty | .465 | |||

| Nonfrail (reference) | 1 | - | - | |

| Prefrail | 1.17 | 0.90–1.54 | .234 | |

| Frail | 1.21 | 0.78–1.87 | .397 | |

Note: Adjusted for sex, education level, income, smoking status, drinker status, number of chronic diseases, self-reported health, Center for epidemiologic studies-depression scale (excluding the two questions included in the frailty definition), Mini-mental state examination score, and baseline disability (mobility, IADL and ADL).

Cox proportional hazards model with delayed entry.

Figure 2.

Survival curve estimate (adjusted) over the 4 years of follow-up according to frailty status at baseline. The 3C Study

DISCUSSION

The main purpose of this research was to describe the characteristics and prognosis of elderly subjects defined as frail in a large sample of French community-dwelling people. The results obtained in this study are consistent with those previously described in North America and other countries of Europe, which contribute to reinforce the predictive validity of the concept of frailty as well as its role in the health status of the elderly. Frailty status predicts multiple adverse outcomes and, even after adjusting for potentially confounding variables, the phenotype of frailty used in the present research remains an independent predictor of risk, principally of the incidence of disability and hospitalization. By showing the relationship between frailty and adverse health-related outcomes in a population having different lifestyle and food habits, these findings replicate those reported in Italian, African-American and Mexican-American populations where the same five components of frailty, as defined by Fried et al, were considered (27–29). However, it is necessary to consider that the prevalence of frailty has shown an important variability across populations (e.g.: 8.8% for Italians, 12.7% for African-American or 20% for Mexican-American) which could represent an independent association of race with frailty that is not explained by worse health, educational level, or lower socioeconomic status but rather by a different incidence and/or a different duration of this entity (28). A genetic basis for differences in the prevalence of frailty is also plausible.

The main limitation of this study may be the use of slightly different measures to define frailty criteria since the measures originally used by Fried et al (3) were not available in the 3C Study. Nonetheless, despite slightly different measurements, the prevalence of frailty in elderly French persons (around 7%) was similar to that reported in other studies carried out in community-dwelling white people and the strength of the association between frailty and the principal outcomes were as previously reported (3,27), although the phenotype used was not a statistically significant predictor of death after adjusting for multiple covariables. Indeed, persons classified as frail were more likely to be older and female or to have more depressive symptoms. Besides the association with co-morbidity and disability, adverse social conditions such as living alone or low income, were also more frequent among prefrail and frail people. However, it is necessary to insist that frailty overlapped, but is not synonymous with, co-morbidity and disability. Thus, for example, not all frail participants were disabled at baseline, and among those without disability at baseline and who met criteria for frailty, only 68.2%, 26.4% and 2.7% had mobility, IADL, or ADL disability, respectively, at the 4-year follow-up. These findings support the hypothesis that frailty often precedes disability and that they are distinct entities. Nevertheless, exclusion of participants with missing frailty scores (around 6.5% from original sample) could induce a selection bias, since those excluded were significantly older (78.4 vs. 74.1 years), more depressed (mean CES-D score 13.1 vs. 8.1) and more likely to be disabled for mobility (80.6% vs. 44.9%), IADL (29.3% vs. 8.1%) and ADL (1.8% vs. 0.4%) which could explain the lack of association between frailty and several outcomes, particularly the risk of death.

The amplitude of the confidence intervals in the significant strength of association between frailty and ADL disability in multivariate analyses may be explained by its low incidence - probably due to general good health of participants at baseline, the relatively short period of follow-up (4 years) and the hierarchic loss of activities of daily living (30). Nevertheless, a significant association reflects the independent contribution of frailty in the development of disability in its different forms. This last argument is also relevant for explaining the association between frailty and mobility and IADL disability for which the results were more consistent.

Although the phenotype of frailty has been shown to be applicable across diverse population samples, in this study for example, those classified as “prefrail” were not at higher risk for ADL disability or hospitalization in comparison to the frail subgroup. Nevertheless, our results are in line with those of Bandeen-Roche et al (13). Using data from the Women’s Health and Aging Studies I and II, they evaluated the cross-validity, criterion validity and internal validity of frailty as defined by Fried et al. These authors also analyzed the number of categories or “classes” that better capture heterogeneity in frailty measures. Although their results do not indicate that two phenotype categories (nonfrail and frail) are better than three (nonfrail, prefrail and frail), the two-class model performed better than the former and demonstrated that frailty criteria aggregate, as required for a medical syndrome. This conception could be useful in detecting frailty before disability or another adverse condition appears. As it has been proposed, frailty may represent one extreme of a health continuum and the inconsistency of this intermediate status in predicting middle-term adverse outcomes could be explained by the longer duration of this status before “true frailty” and its consequences manifest.

In addition to physical aspects, several domains have been considered to contribute to the definition of frailty (31). In this French study, even if the definition of frailty was not completely constructed via the measures originally proposed, the five characteristics were respected and their construct and predictive validity were demonstrated, since frailty was associated with higher risk of hospitalization, disability and death in comparison to prefrail and nonfrail individuals. In addition, the present results are consistent with the findings of other studies that included other surrogate measures of strength, mobility and weight loss (32–35). As reported recently, biological connections between all these components are plausible, and one should be related to another, giving a common pathophysiological pathway which is crucial for the prevention or delay of adverse consequences (1,27).

Even if characteristics of frailty constitute a multidimensional cluster of components, the application of which may help in identifying individuals at high risk of adverse outcomes, questions have been raised about specific criteria. For example, only considering “shrinking” among the key determinants could underestimate frailty in the obese people when they are a substantial subset of the frail population (36).

Although it has been suggested that, in addition to physical aspects, other domains have to be considered to define frailty (37), Fried’s definition of frailty proves to be reproducible and relevant to predict adverse outcomes through different populations showing its solidity and stability. The use of a standardized phenotype will lead to a comparison between different populations and, will possibly serve to identify etiological factors, components or other correlates of frailty. This may be an acceptable option and awaits studies that consider the frailty concept as their principal objective of research. Nevertheless, important advances have been occurred in the field with the proposal of methodological guidelines to include frail people in future research (38).

In spite of the limits previously mentioned, this study has several strengths. Previous research in frailty has been conducted in France (39,40). However, this is the first one that uses a definition of frailty widely acknowledged to identify the affected individuals and to report its characteristics and prognosis. In addition, the study was conducted in a large population-based sample and had a prospective design.

Exploration of other possible dominions of frailty is necessary. Understanding the medical, biological and environmental factors that contribute to the phenomenon of frailty is the goal of current research in the field (38). Elderly persons who are frail would benefit from complex, multidisciplinary care compared with usual care (41,42), which explains why efforts must be directed to detect this clinical state before irreversible disability or other adverse outcomes appear. Prospective research is required to ascertain whether intervention programs targeting frail subjects may delay or reverse disability and loss of autonomy.

Acknowledgments

The Three-City study is conducted under a partnership agreement between the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), the Victor Segalen-Bordeaux 2 University, and Sanofi-Aventis. The Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale funded the preparation and initiation of the study. The Three-City study is also supported by the Caisse Nationale Maladie des Travailleurs Salariés, Direction Générale de la Santé, MGEN, Institut de la Longévité, Conseils Régionaux d’Aquitaine et Bourgogne, Fondation de France, and Ministry of Research-INSERM Programme “Cohortes et collections de données biologiques”.

The fist author, Dr J.A. Ávila-Funes, was supported by a Bourse Charcot (2006–2007) from the Ministère des Affaires Étrangères in France.

References

- 1.Walston J, Hadley EC, Ferrucci L, et al. Research agenda for frailty in older adults: toward a better understanding of physiology and etiology: summary from the American Geriatrics Society/National Institute on Aging Research Conference on Frailty in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:991–1001. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bortz WM., 2nd A conceptual framework of frailty: a review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:M283–M288. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.5.m283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fried LP, Hadley EC, Walston JD, et al. From bedside to bench: research agenda for frailty. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2005;2005:pe24. doi: 10.1126/sageke.2005.31.pe24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chin A, Paw MJ, Dekker JM, et al. How to select a frail elderly population? A comparison of three working definitions. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:1015–1021. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rockwood K, Stadnyk K, MacKnight C, et al. A brief clinical instrument to classify frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 1999;353:205–206. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04402-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Syddall H, Cooper C, Martin F, et al. Is grip strength a useful single marker of frailty? Age Ageing. 2003;32:650–656. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afg111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Penninx BW, et al. Prognostic value of usual gait speed in well-functioning older people--results from the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1675–1680. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Iersel MB, Rikkert MG. Frailty criteria give heterogeneous results when applied in clinical practice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:728–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00668_14.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bortz WM., 2nd The physics of frailty. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:1004–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitnitski AB, Graham JE, Mogilner AJ, et al. Frailty, fitness and late-life mortality in relation to chronological and biological age. BMC Geriatr. 2002;2:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woods NF, LaCroix AZ, Gray SL, et al. Frailty: emergence and consequences in women aged 65 and older in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1321–1330. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bandeen-Roche K, Xue QL, Ferrucci L, et al. Phenotype of frailty: characterization in the women’s health and aging studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:262–266. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.3.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rockwood K. What would make a definition of frailty successful? Age Ageing. 2005;34:432–434. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The 3C study group. Vascular factors and risk of dementia: design of the Three-City Study and baseline characteristics of the study population. Neuroepidemiology. 2003;22:316–325. doi: 10.1159/000072920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guigoz Y. The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) review of the literature--What does it tell us? J Nutr Health Aging. 2006;10:466–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tayback M, Kumanyika S, Chee E. Body weight as a risk factor in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1065–1072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larrieu S, Peres K, Letenneur L, et al. Relationship between body mass index and different domains of disability in older persons: the 3C study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:1555–1560. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1997;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rantanen T, Pertti E, Kauppinen M, et al. Maximal isometric muscle strength and socioeconomic status, health, and physical activity in 75-year-old persons. J Aging Phys Activity. 1994;2:206–220. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson AW, Morrow JR, Jr, Bowles HR, et al. Construct validity evidence for single-response items to estimate physical activity levels in large sample studies. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2007;78:24–31. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2007.10599400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosow I, Breslau N. A Guttman Health Scale for the Aged. J Gerontol. 1969;21:557–560. doi: 10.1093/geronj/21.4.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katz S, Downs TD, Cash HR, et al. Progress in development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist. 1970;10:20–30. doi: 10.1093/geront/10.1_part_1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuhrer R, Rouillon F, Lellouch J. Diagnostic reliability among French psychiatrists using DSM-III criteria. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1986;73:12–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1986.tb02658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cesari M, Leeuwenburgh C, Lauretani F, et al. Frailty syndrome and skeletal muscle: results from the Invecchiare in Chianti study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1142–1148. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.5.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirsch C, Anderson ML, Newman A, et al. The association of race with frailty: the cardiovascular health study. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ottenbacher KJ, Ostir GV, Peek MK, et al. Frailty in older Mexican Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1524–1531. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barberger-Gateau P, Rainville C, Letenneur L, et al. A hierarchical model of domains of disablement in the elderly: a longitudinal approach. Disabil Rehabil. 2000;22:308–317. doi: 10.1080/096382800296665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rockwood K. Frailty and its definition: a worthy challenge. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1069–1070. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ory MG, Schechtman KB, Miller JP, et al. Frailty and injuries in later life: the FICSIT trials. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:283–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, et al. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:556–561. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tinetti ME, Inouye SK, Gill TM, et al. Shared risk factors for falls, incontinence, and functional dependence. Unifying the approach to geriatric syndromes. JAMA. 1995;273:1348–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown M, Sinacore DR, Binder EF, et al. Physical and performance measures for the identification of mild to moderate frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M350–M355. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.6.m350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blaum CS, Xue QL, Michelon E, et al. The association between obesity and the frailty syndrome in older women: the women’s health and aging studies. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:927–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Studenski S, Hayes RP, Leibowitz RQ, et al. Clinical Global Impression of Change in Physical Frailty: development of a measure based on clinical judgment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1560–1566. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Studenski S, et al. Designing randomized, controlled trials aimed at preventing or delaying functional decline and disability in frail, older persons: a consensus report. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:625–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vellas B, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Nourhashemi F, et al. Falls, frailty and osteoporosis in the elderly: a public health problem. Rev Med Interne. 2000;21:608–613. doi: 10.1016/s0248-8663(00)80006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nourhashemi F, Andrieu S, Gillette-Guyonnet S, et al. Instrumental activities of daily living as a potential marker of frailty: a study of 7364 community-dwelling elderly women (the EPIDOS study) J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M448–M453. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.7.m448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rockwood K, Stadnyk K, Carver D, et al. A clinimetric evaluation of specialized geriatric care for rural dwelling, frail older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1080–1085. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gill TM, Baker DI, Gottschalk M, et al. A program to prevent functional decline in physically frail, elderly persons who live at home. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1068–1074. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]