Abstract

Objective. To identify specific preceptor teaching-coaching, role modeling, and facilitating behaviors valued by pharmacy students and to develop measures of those behaviors that can be used for an experiential education quality assurance program.

Methods. Using a qualitative research approach, we conducted a thematic analysis of student comments about excellent preceptors to identify behaviors exhibited by those preceptors. Identified behaviors were sorted according to the preceptor’s role as role model, teacher/coach, or learning facilitator; measurable descriptors for each behavior were then developed.

Results. Data analysis resulted in identification of 15 measurable behavior themes, the most frequent being: having an interest in student learning and success, making time for students, and displaying a positive preceptor attitude. Measureable descriptors were developed for 5 role-modeling behaviors, 6 teaching-coaching behaviors, and 4 facilitating behaviors.

Conclusion. Preceptors may need to be evaluated in their separate roles as teacher-coach, role model, and learning facilitator. The developed measures in this report could be used in site quality evaluation.

Keywords: experiential learning, pharmacy education, clinical clerkship, qualitative research, preceptorship

INTRODUCTION

Schools and colleges of pharmacy are expected to evaluate preceptor performance as part of the experiential education quality assurance process requirement stated in the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Standards 20071 and in ACPE Draft Standards 2016.2 Guideline 21.1 in Standards 2016 states that schools and colleges must apply quality criteria when conducting preceptor performance evaluation.2 Guidance Statement 21b of the Draft Guidance for Standards 2016 states that preceptors should demonstrate an aptitude for teaching in the various roles of instructing, coaching, modeling, and facilitating.3

Evaluating preceptor performance is more complex than evaluating teacher performance in the classroom because of the dynamic aspect of practice, uniqueness of each student-preceptor interaction, and the variety of ways students learn. As teachers, preceptors encourage application of didactic knowledge through discussion with students during learning situations as they evolve.4 As coaches, preceptors guide students through new experiences and difficult decision-making situations.5 As role models, preceptors embody professional attitudes, values, and ethics by continually demonstrating these attributes over the course of the experience.4 As facilitators, preceptors create the infrastructure within a practice site that fosters and supports student learning.6 Coaching and teaching in the practice environment involve instruction by the preceptor and interaction between student and preceptor, and thus, are difficult to distinguish and easier to evaluate if merged. The teacher-coach role is different from role modeling, where students learn from the role model, often subconsciously, through sensory application (seeing and listening) and emulation (or a conscious decision to not emulate). The teacher-coach role is also different from the facilitator role, which relies on the preceptor creating an environment conducive to student learning. Perhaps, then, preceptors should be evaluated in each of these 3 roles.

Appendix C of Standards 20071 contained a list of 10 desired behaviors, qualities, and values of preceptors. In 2007, all of these statements were incorporated into the University of Washington advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE) evaluation instrument submitted by students at the completion of each APPE. In spring 2012, feedback from a student focus group on the site/preceptor evaluation instrument indicated that students were unsure how to evaluate or did not understand 5 attributes: a desire to educate others; an aptitude to facilitate learning; competency in the documentation and assessment of student performance; a systematic, self-directed approach to their own continuing professional development; and commitment to their practice organization, professional societies, and community. A search of the literature to find more specific, data-derived pharmacist-preceptor performance behaviors identified only one published study. An investigator in Thailand examined frequency-scale and adequacy-scale scoring differences between students and preceptors of 47 different teaching behaviors and found that preceptors tended to rank their performance as “well done and adequate” more frequently than their students did.7 The 47 teaching behaviors measured in this study were derived from the medical education literature.

Studies of precepting behaviors published in the medical8-18 and nursing19-21 literature most frequently require student or resident response to a series of educator-defined value statements,8-19 but there may be other characteristics valued by students not represented in the educator-defined value statements. Student-defined value statements about medical and nursing preceptor behaviors are derived from qualitative studies where open-ended statements made by medical students or residents on their evaluation are analyzed and used to identify what students valued (or didn’t) about their preceptors.22-27 For example, Ullian and colleagues analyzed student evaluations of their preceptors to identify desirable physician-preceptor characteristics.24 Identification of student-defined and valued preceptor behaviors has not yet been described in the pharmacy education literature.

When the draft guidance to Standards 2016 was released in early February 2014 and contained the same preceptor behavior and value statements as the previous standards, we decided to design and conduct this study. The primary goal of the study was to create measurable statements of preceptor behaviors that University of Washington students could understand and that could be used as student-derived quality measures for preceptor performance.

METHODS

This study used thematic analysis28 of all student statements made about selected preceptors between July 2008 and December 2013. The statements were voluntarily made in response to the prompt “comments about your preceptor.” The 21 preceptors selected were winners of the University of Washington School of Pharmacy Excellence in Clinical Teaching award, given annually to one or two individuals who are nominated for or invariably noted by students as exemplary preceptors.

Statements made about these preceptors were uploaded into a spreadsheet and de-identified by removing all information such as the preceptor’s name, practice setting name, description of services offered, etc. The study protocol was reviewed by a University of Washington Human Subjects Division Subcommittee, who determined it did not meet the federal regulatory definition of human subjects research.

Two fourth-year doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) students, guided by faculty mentors, independently identified common themes in the student statements by manually highlighting words and phrases that shared similarities in contextual meaning across statements.28 The two students then met repeatedly to compare identified themes, reconcile differences, improve theme descriptions, identify trigger words, and develop coding descriptions.29,30 All statements were coded with the possibility of one response being categorized into multiple themes. To test robustness of theme descriptions, a third fourth-year student pharmacist independently coded a subset of the responses (the first 7-10 responses per preceptor) using the descriptions created by the first 2 coders.31 Cohen’s kappa coefficient (ƙ) was used to compare level of agreement between coders and verifier. A kappa >0.6 was considered satisfactory agreement in this analysis.32 Themes with kappas below 0.6 underwent analysis by the primary author to identify presence of the theme within each discrepantly coded comment, using the coding descriptions that had been written by the coders and used by the verifier. Additional trigger words arising from analysis of discrepancies in intercoder agreement were added to theme descriptions to increase description robustness. All statistical analysis was done using R, v3.0.3 (R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).33

This process was repeated with 2 other groups of preceptors in order to test theme representativeness.34 The first group included 12 randomly selected preceptors (from a list of community, clinic, and inpatient preceptors with 5 or more student comments during the same time period) who had not received the Excellence in Clinical Teaching award, and thus were considered representative of the “average” preceptor at the University of Washington. The second preceptor group was composed of excellent preceptors from the University of Wyoming, as evidenced by student nominations for the Preceptor of the Year award. The comments about preceptors in this group were generated by students in response to the prompt, “If you would recommend this preceptor for the Preceptor of the Year Award, please explain why.”

In the final stage of this study, theme descriptions were grouped according to whether the behaviors best described the broader categories of role modeling (learning acquired through observation of the preceptor interacting with others), teaching-coaching (learning acquired during preceptor-student interaction), or facilitation (learning enabled by the structure or environment of the experience).4-6 Only themes describing measurable behaviors were applied to this grouping. The finalized theme descriptions were then translated to statements of measurable behaviors using verbs from the higher levels of Krathwohl’s affective domain, since the affective domain best describes exhibited behaviors.35

RESULTS

Four hundred fifty-nine qualitative statements were made by 286 students about 21 selected preceptors (4 community pharmacists, 10 inpatient pharmacists, 5 clinic pharmacists, and 2 pharmacists working in nonpatient care settings) between July 2008 and December 2013. During this time, there were 620 opportunities for student comments about these individuals, so 74% of the students chose to comment on their preceptor. The average age of these students upon admission was 25 years, the classes were 63-70% female, and 75% to 85% of students had a prior degree.

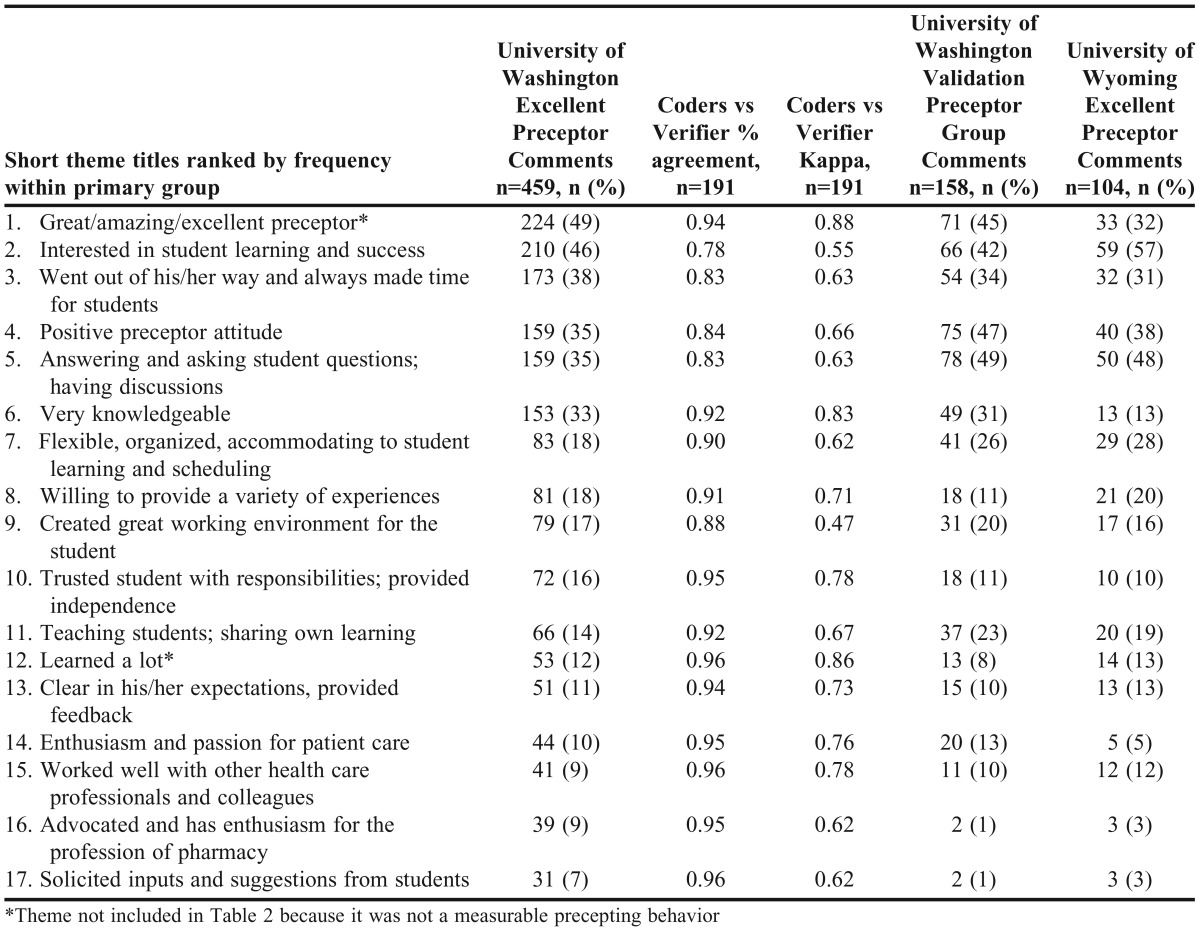

All 459 statements were examined in the analysis by the coders. Seventeen different themes emerged from the data (short titles listed in Table 1), with the final theme (“solicits inputs and suggestions from student”) first appearing in comment #40; no new themes emerged in the 419 subsequent comments. Use of complimentary but nonspecific adjectives to describe the preceptor was the most common theme, followed by an interest in student learning and success. A willingness to make time for students was the third most common theme.

Table 1.

Frequency of Themes and Level of Agreement Among Students Regarding Preceptor Behavior

One hundred ninety-one comments were coded by the verifier student. All but 2 themes (interested in student learning and success, created great working environment for the student) met the threshold for satisfactory agreement between primary coders and verifier (Table 1). Discrepancy analysis by the primary author resulted in modifications to the theme descriptions for the 2 themes not initially reaching satisfactory agreement.

Comments (n=159) made by 141 students about 12 preceptors (4 community, 4 clinic, and 4 inpatient) who were not recipients of the Excellence in Clinical Teaching award were then analyzed for new themes about these “average” preceptors—none were discovered. The numbers and frequency of themes from this group of preceptors can be seen in Table 1.

No additional themes were identified when comments (n=104) about University of Wyoming preceptors were coded using themes developed from the University of Washington data. Frequencies of the learning themes for University of Wyoming data are listed in Table 1. The 5 most frequently occurring themes in the University of Washington excellent preceptors data were also the 5 most frequently occurring themes in the University of Wyoming data. University of Wyoming students had an age range upon graduation was 24 to 48 years, with a mean of 28 years.

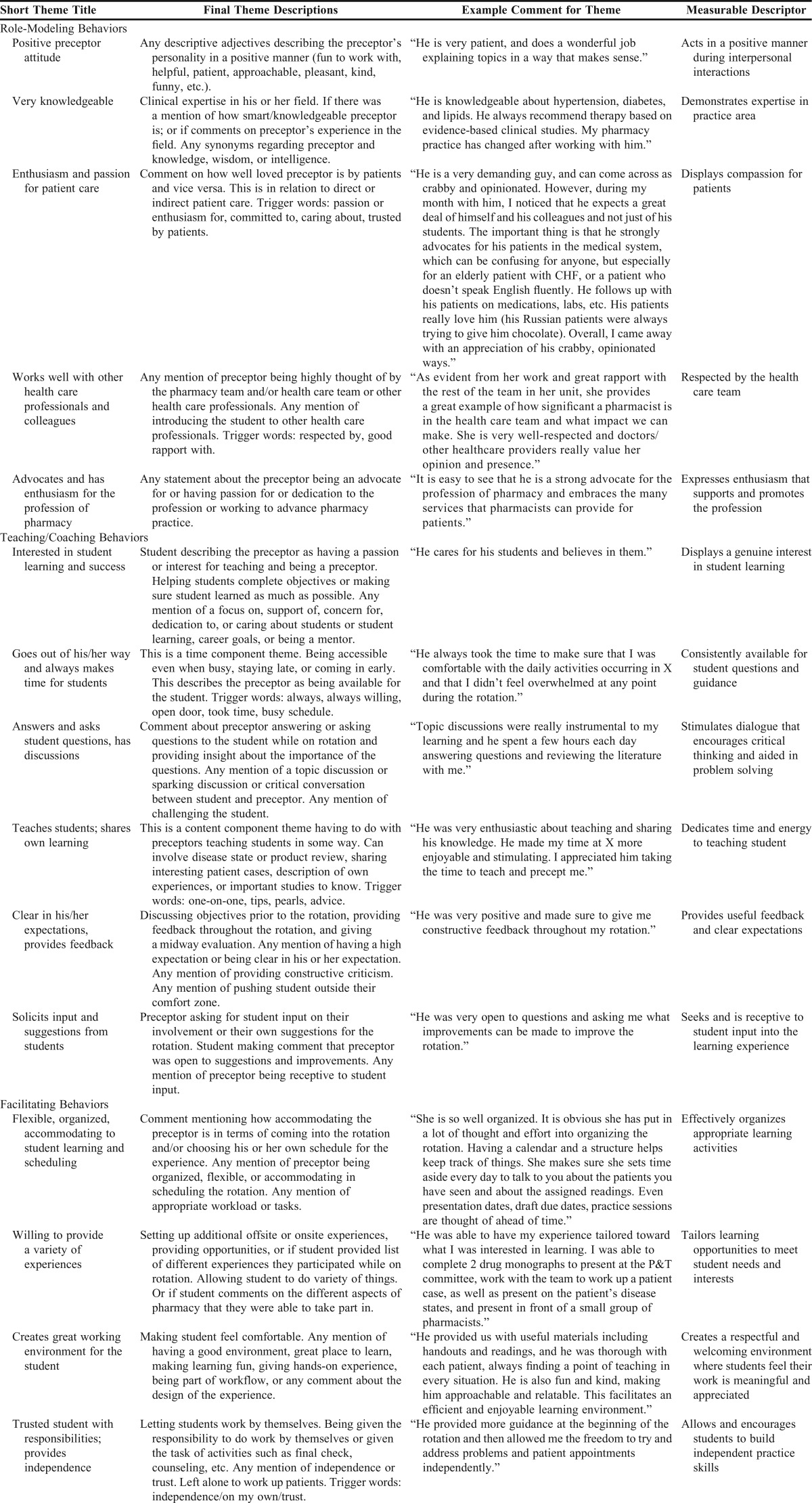

Of the 17 identified themes, one (use of complimentary adjectives) was not translatable into a measurable precepting behavior and another (learned a lot) was a student behavior rather than a precepting behavior. Of the remaining 15 themes, 5 were translated into measurable descriptors of role-modeling behaviors, 6 translated to measurable descriptors of teaching-coaching behaviors, and 4 translated to measurable descriptors of facilitating behaviors. The short titles for these behaviors, the final theme descriptors written by the coders and modified by the primary author, and an example student comment for each behavior are in Table 2. Also in Table 2 is the measurable descriptor that was developed for each behavior using verbs from Krathwohl’s affective domain.36

Table 2.

Theme Coding Rules, Examples, and Measurable Descriptor Developed from Theme Analysis

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to develop measurable descriptors of excellent preceptors based on what students appeared to value about those preceptors, and 15 such descriptors were identified. These identified descriptors will be used in future student evaluations of preceptors.

In April 2014, when we had completed thematic analysis, a retrospective cohort study by Young and colleagues was published.37 Student Likert-scale agreement rankings of 14 different precepting characteristics were examined for frequency of occurrence in excellent preceptors relative to other preceptors. Excellent precepting was most highly associated with 4 characteristics: relating to the student as an individual, showing interest in teaching, encouraging students to actively participate in discussion and problem-solving exercises, and serving as a role model. Four other significant characteristics were availability of the preceptor to answer student questions, provision of good direction and feedback, adequate organization and structure of the experience, and willingness to spend time discussing issues with students.

Six of the 8 characteristics of excellent preceptors identified by Young and colleagues are nearly identical to the behaviors described in our study: displayed a genuine interest in student learning, stimulated dialogue that encouraged critical thinking and aided in problem-solving, consistently available for student questions and guidance, provided useful feedback and clear expectations, effectively organized appropriate learning activities, and dedicated time and energy to teaching student.37 One characteristic identified by Young and colleagues, serving as a role model, is broken down into separate behaviors characterizing good role models in our study. Relating to the student as an individual, the characteristic most highly associated with excellent preceptors in the study by Young and colleagues, was not detected as a separate theme in our study. One explanation for this discrepancy is that relating to the student as an individual is one of the subthemes in our study’s theme of interest in student learning and success, an explanation supported by some of the words (eg, support of...career goals, being a mentor) used in that theme description.

One of the more frequently mentioned themes in our study was preceptor knowledge, but this attribute was not significantly associated with preceptor excellence in the study by Young and colleagues.37 Perhaps students consider most preceptors to be knowledgeable, scoring them similarly in this behavior, but are more likely to comment upon knowledge exhibited by exemplary teachers in an open-text comment. This concept is consistent with thematic analysis of journal entries made by medical students during practice experiences,38 where the most frequent preceptor behavior theme was “demonstrates professional expertise.”

Only 11% of the statements analyzed in our study mentioned preceptor feedback to students, a significant attribute of excellent preceptors in the study by Young and colleagues, where all students were specifically asked about this characteristic.37 Some studies of medical preceptors also show that feedback is not as commonly remarked upon in student evaluations as other attributes.10,23 It may be that lack of feedback is highly recognized by students, but sufficient feedback is expected and less likely to be singled out for commentary. In their qualitative study of student comments about physician preceptors, Kernan and O’Conner found the second most highly valued preceptor characteristic was giving constructive and timely feedback, but it was primarily in the context of preceptor deficiencies rather than attributes.26

The methods and results of our study are somewhat similar to those described by Ullian and colleagues, who analyzed comments written by 268 medical residents on evaluations of 490 clinical teachers over a 5-year period to determine what residents considered to be the important components of the clinical teacher role.24 Content analysis of these comments resulted in 157 categories in 37 clusters that were applied to the 4 roles of the physician-preceptor: physician (role model), supervisor, teacher, and person. Categories with the highest frequency rankings were use of complimentary but nonspecific adjectives or phrases to describe some aspect of the preceptor: knowledgeable, gives resident responsibility/opportunities, supportive, commitment to/interest in teaching, clinical competence/role model, available, easy to work with, and dialogue and rapport with patients. The current study had similar themes, with the exception of flexibility/organization/accommodation to student schedule, a preceptor characteristic that may be more highly valued by pharmacy students at the University of Washington and University of Wyoming compared to the medical residents in the study by Ullian and colleagues.

Many of the themes identified in our study (eg, displayed a genuine interest in student learning, allowed and encouraged students to build independent practice skills) are described in the list of preceptor characteristics identified in the report by the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) 2003-2004 Professional Affairs Committee (eg, demonstrates interest and enthusiasm in teaching, stimulates the student to learn independently, and allows autonomy that is appropriate to the student’s level of experience and competence).6 This committee was charged with identifying how academic pharmacy could improve development and evaluation of experiential learning, and one of their recommendations was that AACP should facilitate development of standard assessment instruments for preceptor evaluation and quality assurance for use at all schools of pharmacy. This study may contribute to the evidence base for instrument development.

The conclusions of 2003-2004 AACP Professional Affairs Committee report and competency statements for preceptor excellence arising from the 2004 AACP Academic-Practice Partnership Initiative Summit39 were reiterated in the 2011-2012 AACP Professional Affairs Committee report4 promoting teaching effectiveness of volunteer preceptors. One of the statements made in this report was that each school of pharmacy should develop its own definition and criteria for preceptor excellence. The methods used in this study may be of use to faculty members of other schools who wish to use their own student data to develop criteria for preceptor excellence.

Many of the themes identified in our study are interconnected. For example, stimulated dialogue that encouraged critical thinking and aided in problem solving, provided useful feedback and clear expectations, as well as sought and was receptive to student input into the learning experience, all require dialogue to occur between preceptor and student. These categories could be lumped together under a more general behavior descriptor such as “effective communicator,” but the more general feedback becomes, the less helpful it is to preceptors interested in knowing specifically what they are doing well and what areas need improvement.40

Data obtained from other groups are likely to yield different themes. For example, data in this study contained few comments from introductory pharmacy practice experience students, who may value different behaviors in their preceptors from their APPE student colleagues. Students who chose not to respond to the prompt inviting comments about the preceptor may have different opinions about that preceptor compared to students who chose to respond, and those different opinions might generate additional themes. Data in this study included statements about only 2 preceptors working in nonpatient care settings; an analysis of more preceptors of this type might identify additional valued behaviors. Data from this study was derived only from students: it is probable that educators, administrators, employers, or preceptors themselves would list a different set of valued behaviors. For example, “practices continuous professional development” may be a behavior valued by the educational institution or an employer, but a student is unlikely to observe evidence of this behavior in the short time period spent with the preceptor. Students at other schools of pharmacy may have important demographic differences (eg, average age, number with undergraduate degrees, different ethnic diversity) compared to the student populations in our study, which could affect the kinds of statements students would make about their preceptors and so identify different themes.

Another limitation is placement of the open-ended prompt “Comments about this preceptor” after student Likert-scale response to behaviors suggested in ACPE Standards 2007 Appendix C. This placement may have primed or channeled students to consider only certain kinds of behaviors in their open-ended comments.

A final limitation is the low agreement between coders and verifier for 2 of the identified themes: interested in student learning and success and created great working environment for the student. The coding themes were modified after discrepancy analysis but it is unknown if this modification would have increased agreement between coders and verifier if they had recoded the data.

One criticism of the current study could be the use of data obtained from the site and preceptor evaluation instrument submitted by students, rather than data derived from a survey specifically designed to ask students what they value about their preceptors. This was done purposefully. A survey would yield data from only one class of students at a single point in time and might not yield a response rate adequate to represent the opinions of the majority of the class, producing an inadequate amount of potentially biased data for thematic analysis.

CONCLUSION

This qualitative study used data to identify measurable desired preceptor behaviors from students’ point of view. Students valued 5 specific role-modeling behaviors, 6 teaching-coaching behaviors, and 4 facilitating behaviors. Evaluating specific and measurable precepting behaviors in each of these roles may aid in assessing the overall quality of experiential sites.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Donal O’Sullivan, PhD, in the statistical analysis of the data and Lynne Robins, PhD, Joy B. Plein, PhD, and Brian Werth, PharmD, for their careful review of the manuscript and editing suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy degree, version 2.0. Chicago (IL): Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education; 14 Feb 2011. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/standards/S2007Guidelines2.0_ChangesIdentifiedinRed.pdf. August 1, 2013.

- 2. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy degree, draft standards 2016. Chicago (IL): Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education; 3 Feb 2014. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/deans/Standards2016DRAFTv60FIRSTRELEASEVERSION.pdf. Accessed February 4, 2014.

- 3. Guidance for the accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy degree, draft guidance for standards 2016. Chicago (IL): Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education; 3 Feb 2014. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/deans/GuidanceStandards2016DRAFTv60FIRSTRELEASEVERSION.pdf. Accessed February 4, 2014.

- 4.Harris BJ, Butler M, Cardello E, et al. Report of the 2011-2012 AACP Professional Affairs Committee: addressing the teaching excellence of volunteer pharmacy preceptors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(6) doi: 10.5688/ajpe766S4. Article S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chase SM, Crabtree BF, Stewart EE, et al. Coaching strategies for enhancing practice transformation. Fam Pract. 2014 Oct 4;pii:cmu062. Available at: fampra.oxfordjournals.org/. Accessed November 20, 2014.

- 6.Littlefield LC, St Haines, Harralson AF, et al. Academic pharmacy’s role in advancing practice and assuring quality in experiential education: report of the 2003-2004 Professional Affairs Committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(3) Article S8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sonthisombat P. Pharmacy student and preceptor perceptions of preceptor teaching behaviors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(5) doi: 10.5688/aj7205110. Article 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright SM, Kern DE, Kolodner K, Howard DM, Brancati FL. Attributes of excellent attending-physician role models. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(27):1986–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812313392706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irby DM. Clinical teacher effectiveness in medicine. J Med Educ. 1978;53(10):808–815. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197810000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elnicki DM, Kolarik R, Bardella I. Third-year medical students’ perceptions of effective teaching behaviors in a multidisciplinary ambulatory clinic. Acad Med. 2003;78(8):815–819. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200308000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schultz KW, Kirby J, Delva D, et al. Medical students’ and residents’ preferred site characteristics and preceptor behaviours for learning in the ambulatory setting: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ. 2004:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-4-12. Article 12. Available from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/4/12. Accessed June 26, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Litzelman DK, Westmoreland GR, Skeff KM, Stratos GA. Student and resident evaluations of faculty – how dependable are they? Acad Med. 1999;74(10):S25–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199910000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robins LS, Gruppen LD, Alexander GL, Fantone JC, Davis WK. A predictive model of student satisfaction with the medical school learning environment. Acad Med. 1997;72(2):134–139. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199702000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donnelly MB, Woolliscroft JO. Evaluation of clinical instructors by third-year medical students. Acad Med. 1989;64(3):159–164. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198903000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Copeland HL, Hewson MG. Developing and testing an instrument to measure the effectiveness of clinical teaching in and academic medical center. Acad Med. 2000;75(2):161–166. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200002000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramsbottom-Lucier MT, Gillmore GM, Irby DM, Ramsey PG. Evaluation of clinical teaching by general internal medicine faculty in outpatient and inpatient settings. Acad Med. 1994;69(2):152–154. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199402000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boerebach BCM, Lombarts KMJMH, Keijzer C, Heineman MJ, Arah OA. The teacher, the physician and the person: how faculty’s teaching performance influences their role modelling. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032089. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3299651/ Accessed September 24, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torre DM, Sebastian JL, Simpson DE. Learning activities and high-quality teaching: perceptions of third-year IM clerkship students. Acad Med. 2003;78(8):812–814. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200308000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith C, Swain A, Penprase B. Congruence of perceived effective clinical teaching characteristics between students and preceptors of nurse anesthesia programs. AANA J. 2011;79(4):S62–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Billay DB, Yonge O. Contributing to the theory development of preceptorship. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:566–574. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaviani N, Stillwell Y. An evaluative study of clinical preceptorship. Nurse Educ Today. 2000;20(3):218–26. doi: 10.1054/nedt.1999.0386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irby DM. What clinical teachers in medicine need to know. Acad Med. 1994;69(5):333–342. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199405000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor C, Dunn TG, Lipsky MS. Extent to which guided-discovery teaching strategies were used by 20 preceptors in family medicine. Acad Med. 1993;68(3):385–387. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199305000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ullian JA, Bland CJ, Simpson DE. An alternative approach to defining the role of the clinical teacher. Acad Med. 1994;69(10):832–838. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199410000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goertzen J, Stewart M, Weston W. Effective teaching behaviours of rural family medicine preceptors. CMAJ. 1995;153(2):161–168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kernan WN, O’Conner PG. Site accommodations and preceptor behaviors valued by 3rd year students in ambulatory internal medicine. Teach Learn Med. 1997;9:96–102. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ende J, Pomerantz A, Erickson F. Preceptors’ strategy,ies for correcting residents in an ambulatory care medicine setting: a qualitative analysis. Acad Med. 1995;70(3):224–229. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199503000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications Inc. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hasieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Saldana J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications Inc., 2013.

- 31.Burla L, Kneirim B, Barth J, Liewald K, Duetz M, Abel T. From text to codings: intercoder reliability assessment in qualitative content analysis. Nurs Res. 2008;57(2):113–117. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000313482.33917.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: The kappa statistic. Fam Med. 2005;37(5):360–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.R Core Team. The R Project for statistical computing, version 3.0.3. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. http://www.R-project.org. Accessed March 30, 2014.

- 34.Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res. 1999;34(5 part 2):1189–1208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krathwohl DR, Bloom BS, Masia BB. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook 2: Affective Domain. New York: Longman, Inc; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murray B. Learning taxonomy – Krathwohl’s affective domain. assessment.uconn.edu/docs/LearningTaxonomy_Affective.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2014.

- 37.Young S, Vos SS, Cantrell M, Shaw R. Factors associated with students’ perception of preceptor excellence. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(3) doi: 10.5688/ajpe78353. Article 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huggett KN, Warrier R, Maio A. Early learner perceptions of the attributes of effective preceptors. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2008;13(5):649–658. doi: 10.1007/s10459-007-9069-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Academic-Practice Partnership Initiative (APPI) preceptor-specific critera of excellence. http://www.aacp.org/resources/education/APPI/Documents/Preceptor%20Criteria%20PPEs.pdf . Accessed February 5, 2014.

- 40.Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education. JAMA. 1983;250(6):777–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]