Abstract

Objective. To study the effects of an early professional development series in a pharmaceutical care laboratory (PCL) course on first-year pharmacy students’ perceptions of the importance of professional attitudes and action.

Design. Three hundred thirty-four first-year students enrolled in a PCL course participated in a new required learning activity centered on development of professional attitudes and behaviors. Students discussed situational dilemmas in pharmacy practice in small groups, highlighting application of the Oath of a Pharmacist and the Pharmacists’ Code of Ethics.

Assessment. Students completed an optional questionnaire at the beginning and end of the semester to assess change in their attitudes and behaviors related to professionalism in pharmacy practice.

Conclusion. While students entered their training with a strong appreciation for professionalism, they felt more confident in applying the Oath of a Pharmacist and the Pharmacists Code of Ethics to dilemmas in practice following the new learning activity.

Keywords: professionalism, pharmaceutical care lab, professional ethics

INTRODUCTION

Student professionalism in pharmacy is documented in the literature, including its value, challenges, and strategies to foster professional attitudes and behaviors.1-5 Colleges and schools of pharmacy are responsible for cultivating behaviors related to professionalism as defined in the educational standards from the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) and the Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE).6,7 Thus, while the importance of instilling professional attitudes and behaviors in students is evident, published strategies and efforts in pharmacy curricula remain scarce.

The White Paper on Pharmacy Student Professionalism, authored by a task force from the American Pharmaceutical Association Academy of Students of Pharmacy (APhA-ASP) and the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Council of Deans (AACP-COD), provides a foundation for the definition of professionalism and school-wide strategies to develop professional behaviors and attitudes.3 A national survey of schools of pharmacy collected implementation efforts as described in the White Paper on Pharmacy Student Professionalism across admissions, recruitment, educational programs, and practice.8 The majority of responding schools’ efforts were limited to hosting a White Coat Ceremony, distributing the Oath of a Pharmacist, and involving students in professional organizations. These results indicate that a much broader, school-wide effort is still needed to enhance professional development.8

Pharmacy is not alone in facing the challenges of teaching professionalism. The literature of other health disciplines is extensive, if mostly theoretical.9-13 The challenges in medical education stem from the varied definitions of professionalism and lack of a theoretical model on which to base teaching strategies.14 Defining professionalism and providing recommendations for the medical curriculum have been widely published.9,10,13,15 There is also interest in the effectiveness of “hidden curriculum,” where professionalism is conveyed through behavior observation.16,17 Cohen reported most schools provide some component of professionalism such as small group seminars or discussions, courses in the history of medicine, medical ethics, and community service activities.10

However, there is not one standardized approach, and published strategies implemented in the medical curricula are uncommon. Michigan State University College of Human Medicine described varying components of ethics and professionalism within their curriculum that included: ethics and health policy, a mentoring program, elective offerings, and structured patient care experiences followed by discussion.18 An innovative strategy within a professionalism course at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University used structured reflective writing assignments on course topics and individualized feedback.19 Finally, a national demonstration project with 33 medical schools found that a community-based professionalism curriculum using service-learning pedagogy was a successful approach.20

Despite theoretical concepts and recommendations for didactic instruction, Salinas-Miranda et al suggested that role modeling was the foundation of learning professionalism.21 Their study participants, who were medical students and residents, indicated a disconnect between professional values taught early in their education and experiences in clinical training. The authors concluded more formal teaching regarding challenges in clinical settings and providing feedback on professional behavior are needed.21

An interdisciplinary approach to teaching professionalism concepts also has been reported. Students from 8 health care disciplines, including pharmacy and nursing, participated in a half-day orientation and a 2-hour field experience in a different discipline than their chosen study. The authors found the project increased students’ awareness of professionalism and helped increase understanding of the various roles of the health care team.22

The literature landscape of professionalism within pharmacy is extensive. The most widely published topics include the relevance and importance of professionalism, professionalism in experiential education, and the display of professional attitudes through social media and during clinical practice experiences.23–31

Conversely, studies supporting efforts in the didactic curriculum are limited to 3 studies. A cross-sectional study at the University of Georgia surveyed first-year through fourth-year pharmacy students to assess if professional behaviors within the school aligned with the school’s professionalism curricular competency statement. The survey used a 5-point Likert scale to indicate level of agreement with 42 survey items. Students believed there was overall agreement between the competency statement and behaviors exhibited by pharmacy professionals.32

An innovative approach at McWhorter School of Pharmacy evaluated raising awareness of professionalism prior to beginning the pharmacy curriculum.33 Students read classic short stories and essays prior to orientation and then discussed the readings in small groups during orientation. Students indicated they were more aware of the importance of professionalism through a survey developed by the investigators.33 Finally, team-based learning in a pharmacokinetics course was found to increase professional attitudes. Groups of 6 students worked together on weekly assessments and on patient case questions. Students were surveyed before and after the course on professional attitudes. Results showed a significant increase in overall professionalism score and altruism, honesty, and duty.34 These studies begin to provide evidentiary support that professionalism should be emphasized in the didactic curriculum. Combining these concepts to include early and frequent professionalism activities in the curriculum could be a more impactful approach.

Professionalism may increase throughout the pharmacy curriculum,35 which would support earlier publications alluding to the cultivation of professionalism as multifactorial. However, professional development remains an important concern among pharmacy educators, and few studies exist on cultivating these attitudes and behaviors in pharmacy curricula. Furthermore, efforts reported did not incorporate an early and frequent approach to address professional issues as recommended in the White Paper on Pharmacy Student Professionalism.3 Therefore, consistent with ACPE and CAPE charges to provide a culture that promotes professional behavior, a professional development series was implemented and assessed in a pharmaceutical care laboratory (PCL) course at our institution.6,7 The study was conducted over 2 semester offerings of the course to assess whether this new method of approaching professionalism affected students’ perceived level of professionalism and confidence in resolving situational and ethical dilemmas in future pharmacy practice.

DESIGN

Study participants included first-year PharmD candidates enrolled in the pharmaceutical care laboratory I course in fall 2012 and fall 2013 on the main and satellite campuses. The course is a 5-semester continuum class that meets in small groups (8 students) once weekly and closely aligns with content in concurrent didactic courses. Students are assigned to one of 18 laboratory groups, and the groups are divided into 3 sections, with 6 groups meeting concurrently in each section. The groups are led by third-professional year (PY3) teaching assistants (TAs), who are trained and supervised by the course coordinator.

All students enrolled in the course participated in the new learning activity designed to develop professional behaviors and demonstrate their application in pharmacy practice. It was anticipated that the new professional development series would do the following: provide a forum for students to openly discuss professional controversies; develop students’ personal professional standards; and prepare students to effectively apply the Oath of a Pharmacist and the Code of Ethics for Pharmacists to their experiential education and future pharmacy practice.36,37

On the first day of class, students were notified about the professional development research project and were asked to consider consenting and completing an electronic pre-exercise questionnaire during the first few minutes of class. Students then were introduced to professional expectations of pharmacists and the oath and code during a required 30-minute large group discussion. Students on both campuses participated together via video-teleconference. Electronic copies of the oath and code were made available to students on the course learning management system. Students were instructed to review these documents prior to the first small group laboratory in preparation for the learning activity.

The learning activity was designed to present 8 ethical scenarios over the course of the semester (2 per week). Students would individually reflect on the situation and participate in a small group discussion. All groups discussed the same scenarios, regardless of when their group met for the laboratory. The professional development series was dispersed throughout the semester (weeks 3, 6, 7, and 8), according to available time in the course. At the beginning of the activity, students were given hard copies of the week’s scenarios and given 5 minutes for personal reflection. They recorded their initial responses to the scenarios in the space below each scenario. Students were given instructions to include how the oath and code applied to the scenario and what courses of action might be taken. After personal reflection time, TAs led a 25-minute discussion connecting the oath and code to potential courses of action.

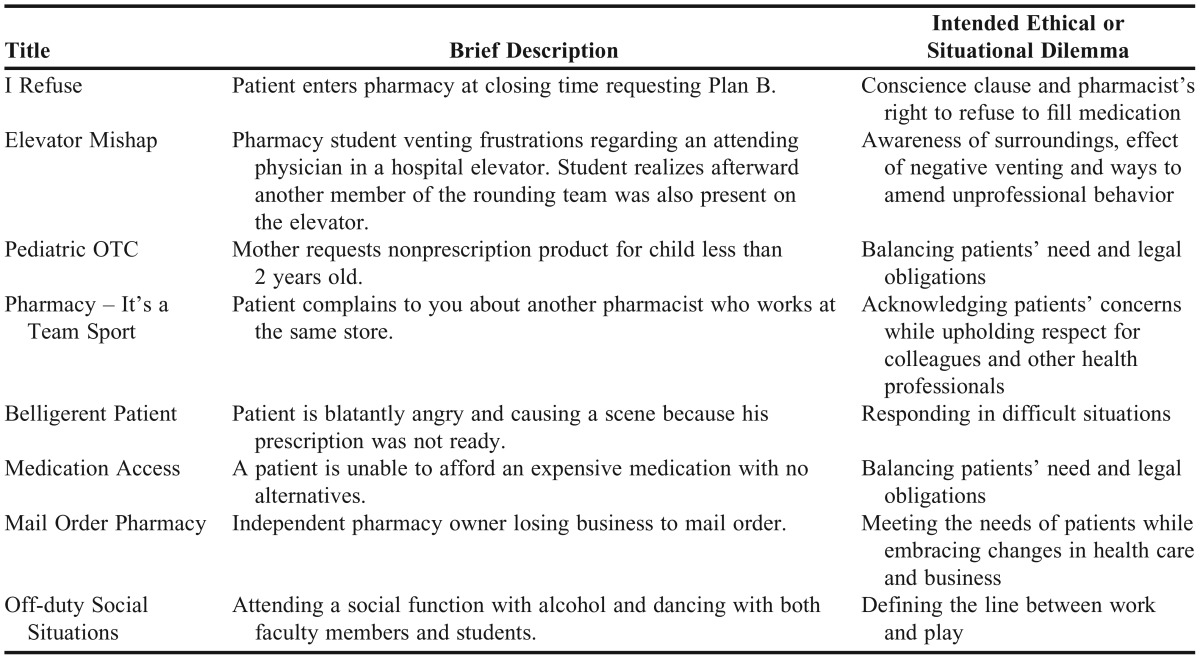

Scenarios presented either an ethical or situational dilemma and were based on current dilemmas in pharmacy practice spanning hospital, community, and social settings. Scenarios were designed as introductory topics to be further developed in a required pharmacy law and ethics course in the third professional year. Laboratory law and ethics faculty members and the director of experiential education reviewed scenarios prior to implementation. Examples of scenario topics and a brief description of each can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Scenarios in the Early Professional Development Series

At the end of the semester, students completed a final self-reflection assignment, which included a written response to a new scenario or one of their choice. In their response, students were instructed to design their own plan for professional action and behavior. After completion of the final assignment, students completed a postintervention questionnaire. Then, reflections were reviewed by TAs and feedback was provided to students on their professional development during a live individual student-TA evaluation session at the end of the course.

Third-year pharmacy students were employed as TAs in the course and were the facilitators for the small group discussions. Given that the TAs were not practicing pharmacists and had limited personal experience with handling similar scenarios, it was imperative for the course coordinator to provide thorough training prior to the laboratory activities. During an orientation to the professional development series, the course coordinator reviewed the oath and the code, including some basic concepts found in the documents (eg, empathy, autonomy). TAs also were briefed on the purpose of the module and expectations for student behavior during the discussions.

Prior to the learning activities in weeks 3, 6, 7, and 8, TAs participated in a meeting that focused on the specific scenarios for the week. TAs participated in a discussion, led by the course coordinator, which allowed for dialogue about the scenarios and time to share examples from theirs and the course coordinator’s experiences. The TAs were given a discussion guide (Appendix A) that listed several example courses of action and how the oath and/or code might guide a practitioner to choose each action. The examples represented varying levels of professionalism, with some answers potentially better than others.

Because of the nature of the discussion, many of the scenarios did not have one “best” or “right” course of action. Teaching assistants were instructed not to force the group to decide on a “right” answer, but instead to elaborate on potential courses of action and cases where they may or may not be appropriate. It was OK for students not to agree on the best approach to handling the scenario. In fact, uncovering different approaches was meant to allow students to cultivate and share their attitudes and beliefs. The TA discussion guide also provided questions to stimulate discussion about the scenario.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

Efficacy of the new professional development series was assessed using an optional 19-item pre/postintervention questionnaire. The questionnaire (Appendix B) was developed based on a previously published professionalism tool developed by Chisholm.38 Of the 18 survey items from the original survey, 13 were used in the questionnaire, and responses were modified from agree/disagree to level of importance (important, moderately important, extremely important). The questionnaire collected student responses to professional dilemmas, value of the oath and the code, and behavioral expectations of professionals. Additionally, the preintervention questionnaire gathered demographic, education, and work experience data. Development of the questionnaire included soliciting feedback from 4 faculty members and consulting staff on survey methodology at the institution.

While participation in the professional development series was a course requirement, completion of the study questionnaires was optional. The questionnaires were administered electronically via Qualtrics (Qualtrics Labs, Inc., Provo, UT) during class time, and students who agreed to participate acknowledged their consent in the first survey item. Students’ grades were not affected by their decision to participate or not participate in the study, and investigators and course coordinators were blinded to student participation lists. Questionnaire data were collected and analyzed using descriptive statistics and t tests. The study was approved by the school’s institutional review board.

During the fall 2012 and fall 2013 semesters, 334 students who enrolled in the course completed the new professional development series (278 on main campus, 56 on satellite campus). The preintervention questionnaire was completed by 216 students (65%), and 234 students (70 %) completed the postintervention questionnaire. Based on the preintervention questionnaire data, the majority of respondents (79%) reported an age of 18-25 years, with 14% stating they were 26-30 years, and 7% of respondents stating they were 31 years or older. Additionally, 39% of respondents reported previous full-time work experience, designated as 40 hours per week or more and not a temporary position (eg, summer or semester break work). Full-time work reported on the questionnaire included pharmacy and nonpharmacy related work. With regard to educational background, the majority of respondents (70%) had completed a bachelor’s degree, 23% had completed undergraduate prerequisites but not a degree, and 6% had earned a master’s degree. Sixty-two percent of respondents were female.

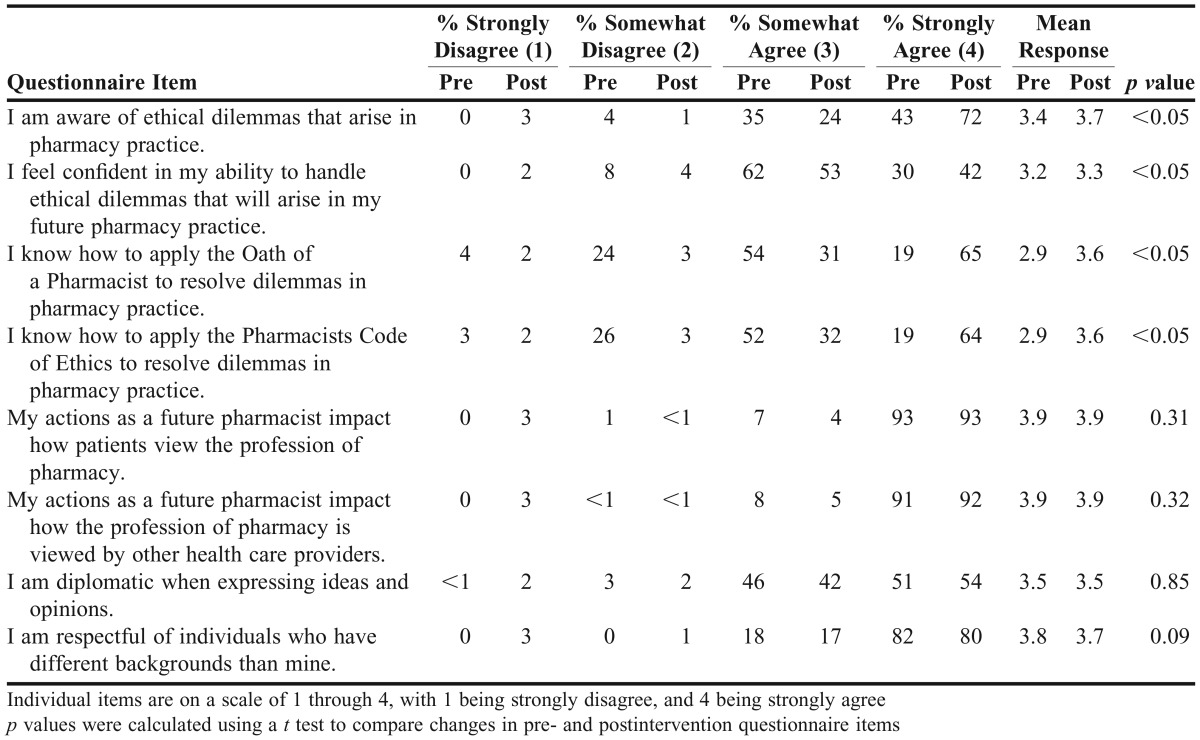

Respondents entered the course with a positive perception of their professional ideals, as evidenced by their responses to the preintervention questionnaire (Tables 2 and 3). More than 92% of respondents strongly agreed that their actions as future pharmacists affected how the profession was viewed by patients and other health care providers (Table 2). Additionally, 82% strongly agreed they were respectful of individuals who had backgrounds different than their own (Table 2). Only 51% of respondents strongly agreed they were diplomatic when expressing ideas and opinions, and this response only increased to 54% after the intervention (Table 2).

Table 2.

Assessment of Professionalism in Pharmacy Practice – Questionnaire Results (Respondents: Pre, n=216; Post, n=234)

Table 3.

Level of Importance of Professional Attributes – Pre/Post Intervention Questionnaire Results

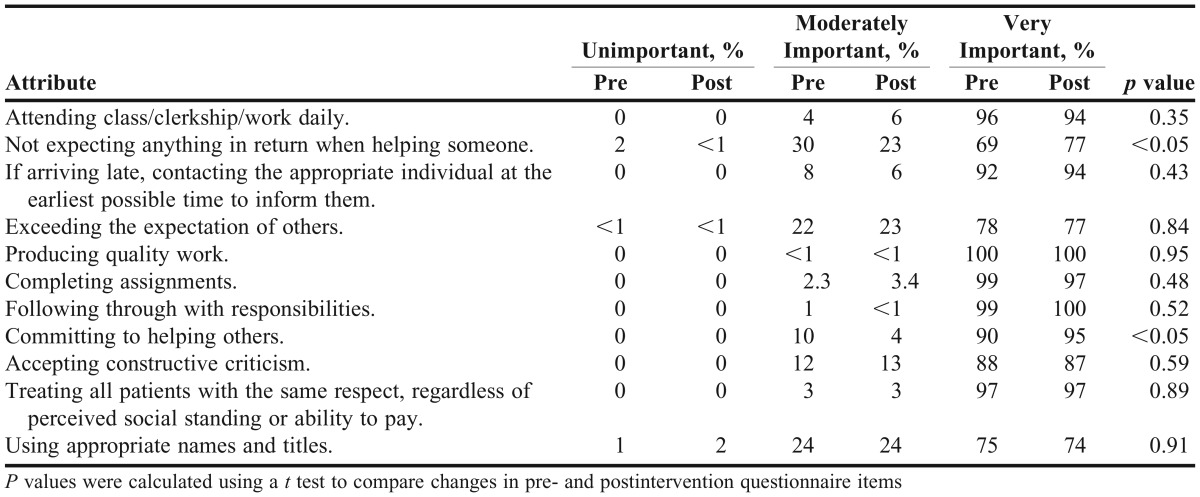

More than 90% of respondents reported characteristics such as attending work daily, producing quality work, following through with responsibilities, and treating all patients with respect were very important for them to uphold in their profession as a future pharmacist (Table 3). Students ranked the following as less important professional attributes: expecting nothing in return when helping someone, exceeding the expectation of others, and using appropriate names and titles. While below 90% on the preintervention questionnaire, only responses to “not expecting anything in return when helping someone” improved on the postintervention questionnaire (Table 3).

Perceived application of professional ideals to pharmacy practice improved after participation in the professional development series. Significantly more respondents strongly agreed after participation they were aware of ethical dilemmas that arise in pharmacy practice (78% vs 43%, p<0.001, Table 2). Forty-one percent strongly agreed they were confident in their ability to handle the dilemmas after the course, compared with 30% before (p=0.03, Table 2). Additionally, significantly more respondents strongly agreed they knew how to apply the oath (65% vs 19%, p<0.001) and the code (64% vs 19%, p<0.001) after the professional development series (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Schools of pharmacy historically have relied on ceremonies and involvement in student organizations to promote professional behavior. These approaches, while still important, place considerable responsibility on the student to recognize and evaluate their professional development. Previous studies showed improvement in professional awareness and professional characteristics through orientation discussions and team-based learning activities. Our study builds upon this knowledge by providing an early and frequent structured activity to engage students in application of pharmacy practice standards and participation in a rich discussion with their peers.

Throughout the professional development series, students were encouraged to share their perspectives, with the goal of cultivating personal professional standards. A larger aim was increasing student awareness of ethical or situational dilemmas early in their development to set the stage for how to manage such dilemmas during practice experiences and future practice. Overall, the results showed students perceived themselves as having a high level of professionalism upon entering the program, as more than 90% of students found 7 of the 11 professionalism traits to be very important (Table 3).

This may be because of a high level of maturity based on previous work experience and completion of a bachelor’s degree prior to matriculation. Of interest, only 68-77% of students ranked the characteristics of exceeding the expectation of others, using appropriate names and titles, and not expecting anything in return when helping others as very important, and only the response to not expecting anything in return when helping someone significantly improved from pre- to postquestionnaire. These may be areas of professional development to target for future activities, as the series did not appear to foster development of these attributes.

The professional development series allowed for successful achievement of applying the oath and the code to practice and to provide a forum for students to openly discuss professional dilemmas. Despite providing open discussion opportunities, it was surprising that more students did not strongly agree to expressing ideas diplomatically and respecting individuals’ backgrounds (Table 2). This may be a result of using PY3 TAs to guide discussions. While TAs were coached each week on the exercises, pharmacy faculty members did not have direct influence over each small group. The investigators observed several of the groups during the semester, and it was noted that some TAs over-directed the discussion, minimizing student participation. Additionally, since the course is the first small group experience in the curriculum, the development of diplomatic expression of ideas in a group setting may have been limited.

One major limitation of the study is that professional development was not influenced solely by the PCL course. Students learned about the importance of professionalism during orientation prior to the first day of class. Additionally, many students were involved in student organizations and receive mentoring from faculty members, which contributes to their development of professional attributes outside of the didactic curriculum. This study was not designed to measure the professional development that takes place outside of the PCL course.

Another limitation is that professionalism was self-assessed. To support students’ opinions of their professionalism, it would have been beneficial to include an observation by a faculty member or TA. A third limitation of the study is that pre- and postintervention data were not matched, allowing only for measurement of changes in self-reported professionalism on a global scale and not at the level of the individual student.

The professional development series will continue to be offered in the course, as it has met all 3 aims of the project. To better address the limitations, new scenarios will be developed to address the 3 areas where students self-assessed at lower levels: use of appropriate names and titles, exceeding the expectation of others, and not expecting anything in return. More focused training will be provided to TAs on how to lead an open discussion or forum to allow for more exchange of ideas within the groups. This should help students build confidence in their ability to be diplomatic when expressing their ideas and to be respectful of individuals who have backgrounds different than their own. Lastly, TA assessment of students’ professionalism will be collected and correlated to students’ self-assessment to determine if students accurately measure their professionalism.

SUMMARY

An innovative professional development series was designed to provide an early, frequent, and structured activity to engage students in application of pharmacy practice standards. Application of professional ideals to pharmacy practice improved after discussion of pharmacy dilemmas in the context of the Oath of a Pharmacist and the Pharmacists Code of Ethics. While students perceived themselves as possessing a high level of professionalism upon entering the program, students benefited from the early introduction to professional and ethical dilemmas in the first-year pharmaceutical care laboratory course.

Appendix A. Example Scenario and Teaching Assistant Discussion Guide

Belligerent Patient Week 8

You are a pharmacist at a busy community pharmacy and have a PY4 student on rotation with you. A patient arrives to pick up their prescription, but it is not ready yet. The patient becomes very angry and creates a scene by raising his voice. How do you respond to the patient? How do you respond to the student as a teaching opportunity?

TA Guided Discussion Questions

How can you use the Oath of a Pharmacist and the Code of Ethics for Pharmacists to guide your response?

Oath of a Pharmacist

•I will hold myself and my colleagues to the highest principles of our profession’s moral, ethical, and legal conduct.

•I will utilize my knowledge, skills, experiences, and values to prepare the next generation of pharmacists.

Code of Ethics for a Pharmacist

•A pharmacist respects the covenantal relationship between the patient and pharmacist.

•A pharmacist promotes the good of every patient in a caring, compassionate, and confidential manner

•A pharmacist respects the autonomy and dignity of each patient.

How would your response change, if at all, if the reason for the delay was your/staff fault or if the situation was out of your control? (If there is disagreement or a variety of answers from group (or if one person has not offered an opinion), directly ask one student how their classmates’ responses made them feel – does it respectfully reflect how they want to be perceived?)

What does it matter how one pharmacist will handle the situation? How does that affect you?

Potential Next Steps (varying levels of professionalism are represented)

•Move his prescription to the front of the queue and work as quickly as possible to get the patient’s prescription ready and get him out of the store

•Explain to the patient the process of the pharmacy and how it isn’t always feasible to have all the prescriptions ready at the same time

•Retort back all of the challenges in a busy pharmacy

•Apologize for the delay and assure the patient of your diligence to make sure his prescription is filled safely and appropriately

Appendix B. Professionalism Questionnaire for Student Pharmacists

For the following items, choose whether you strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, or strongly agree with the statement.

•I am aware of ethical dilemmas that arise in pharmacy practice.

•I feel confident in my ability to handle ethical dilemmas that will arise in my future pharmacy practice.

•I know how to apply the Oath of a Pharmacist to resolve dilemmas in pharmacy practice.

•I know how to apply the Code of Ethics for Pharmacists to resolve dilemmas in pharmacy practice.

•My actions as a future pharmacist impact how the profession of pharmacy is viewed by patients.

•My actions as a future pharmacist impact how the profession of pharmacy is viewed by other health care providers.

•I am diplomatic when expressing ideas and opinions.

•I am respectful of individuals who have different backgrounds than mine.

For the following items, choose how important the characteristic is for you as a future pharmacist in upholding the profession (unimportant, moderately important, very important).

•Attending class/clerkship/work daily

•Not expecting anything in return when helping someone

•If arriving late, contacting the appropriate individual at the earliest possible time to inform them

•Exceeding the expectation of others

•Producing quality work

•Completing assignments

•Following through with responsibilities

•Committing to helping others

•Accepting constructive criticism

•Treating all patients with the same respect, regardless of perceived social standing or ability to pay

•Using appropriate names and titles

(The following items appeared on the preintervention questionnaire only.)

What is your gender?

Male

Female

What is your age?

18-25 years

26-30 years

31-35 years

36-40 years

41-45 years

over 45 years

What is your highest level of training to date?

Undergraduate pharmacy prerequisites (no degree)

Bachelor’s degree

Master’s degree

Other

Please specify:

Do you have any full time work experience, 40 hours/week or more? Note: do not include temporary positions such as during summer or semester breaks. Full time work does not need to be pharmacy related.

Yes

No

REFERENCES

- 1.Hammer DP. Professional attitudes and behaviors: the “A’s and B’s” of professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64(4):455–464. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammer DP, Berger BA, Beardsley RS, Easton MR. Student professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;(3):67. Article 96. [Google Scholar]

- 3.APhA-ASP/AACP-COD Task Force on Professionalism. White paper on pharmacy student professionalism. http://file.cop.ufl.edu/studaff/forms/whitepaper.pdf Accessed January 17, 2015.

- 4.Roth MT, Zlatic TD. Development of student professionalism. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(6):749–756. doi: 10.1592/phco.29.6.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown D, Ferrill MJ. The taxonomy of professionalism: Reframing the academic pursuit of professional development. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;(4):73. doi: 10.5688/aj730468. Article 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/ACPE_Revised_PharmD_Standards_Adopted_Jan152006.pdf Accessed January 17, 2015.

- 7.Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) educational outcomes 2013. http://www.aacp.org/resources/education/cape/Open Access Documents/CAPEoutcomes2013.pdf Accessed January 17, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Sylvia LM. Enhancing professionalism of pharmacy students: results of a national survey. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(4):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brody H, Doukas D. Professionalism: a framework to guide medical education. Med Educ. 2014;48(10):980–987. doi: 10.1111/medu.12520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen JJ. Professionalism in medical education, an American perspective: from evidence to accountability. Med Educ. 2006;40(7):607–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wear D, Castellani B. The development of professionalism: curriculum matters. Acad Med. 2000;75(6):602–611. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200006000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stephenson A, Higgs R, Sugarman J. Medical education quartet teaching professional development in medical schools. Lancet. 2001;357:867–870. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04201-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doukas DJ, McCullough LB, Wear S, et al. The challenge of promoting professionalism through medical ethics and humanities education. Acad Med. 2013;88(11):1624–1629. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a7f8e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Archer R, Elder W, Hustedde C, Milam A, Joyce J. The theory of planned behaviour in medical education: a model for integrating professionalism training. Med Educ. 2008;42(8):771–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner P, Hendrich J, Moseley G, Hudson V. Defining medical professionalism: a qualitative study. Med Educ. 2007;41(3):288–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glicken AD, Merenstein GB. Addressing the hidden curriculum: understanding educator professionalism. Med Teach. 2007;29(1):54–57. doi: 10.1080/01421590601182602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karnieli-Miller O, Vu TR, Holtman MC, Clyman SG, Inui TS. Medical students’ professionalism narratives: a window on the informal and hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 2010;85(1):124–133. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c42896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andre J, Brody H, Fleck L, Thomason CL, Tomlinson T. Ethics, Professionalism, and Humanities at Michigan State University College of Human Medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78(10):968–972. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200310000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wald HS, Davis SW, Reis SP, Monroe AD, Borkan JM. Reflecting on reflections: enhancement of medical education curriculum with structured field notes and guided feedback. Acad Med. 2009. 84(7):830–837. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a8592f. http://apps.webofknowledge.com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/full_record.do?product=WOS&search_mode=GeneralSearch&qid=18&SID=4CWvOARE3H4novej2sQ&page=2&doc=11&cacheurlFromRightClick=no Accessed January 18, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Toole TP, Kathuria N, Mishra M, Schukart D. Teaching professionalism within a community context: perspectives from a national demonstration project. Acad Med. 2005;80(4):339–343. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200504000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salinas-Miranda AA, Shaffer-Hudkins EJ, Bradley-Klug KL, Monroe AD. Student and resident perspectives on professionalism: beliefs, challenges, and suggested teaching strategies. 2014;5:87–94. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5334.7c8d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brehm B, Breen P, Brown B, et al. An interdisciplinary approach to introducing professionalism Am J Pharm Educ 200670(4)Article 81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cain J, Scott DR, Akers P. Pharmacy students’ Facebook activity and opinions regarding accountability and e-professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;(6):73. doi: 10.5688/aj7306104. Article 104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cain J, Scott DR, Tiemeier AM, Akers P, Metzger AH. Social media use by pharmacy faculty: student friending, e-professionalism, and professional use. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2013;5(1):2–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammer D. Improving student professionalism during experiential learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;(3):70. doi: 10.5688/aj700359. Aricle 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kjos AL, Ricci DG. Pharmacy student professionalism and the internet. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2012;4(2):92–101. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prescott J, Wilson S, Becket G. Pharmacy students want guidelines on Facebook and online professionalism. Pharm J. 2012;289(7717):163. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rapport F, Doel MA, Hutchings HA, et al. Eleven themes of patient-centered professionalism in community pharmacy: innovative approaches to consulting. Int J Pharm Pract. 2010;18(5):260–268. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7174.2010.00056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rutter PM, Duncan G. Pharmacy professionalism and the digital age. Int J Pharm Pract. 2011;19(6):431–434. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7174.2011.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson DF, Farmer KC, Beall DG, et al. Identifying perceptions of professionalism in pharmacy using a four-frame leadership model. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;(4):72. doi: 10.5688/aj720490. Article 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waterfield J. Is pharmacy a knowledge-based profession? Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;(3):74. doi: 10.5688/aj740350. Article 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duke LJ, Klugh Kennedy W, McDuffie CH, Miller MS, Sheffield MC, Chisholm MA. Student attitudes, values, and beliefs regarding professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;(5):69. Article 104. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bumgarner GW, Spies AR, Asbill CS, Prince VT. Using the humanities to strengthen the concept of professionalism among first-professional year pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;(2):71. doi: 10.5688/aj710228. Article 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Persky AM. The impact of team-based learning on a foundational pharmacokinetics course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;(2):76. doi: 10.5688/ajpe76231. Article 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poirier TI, Gupchup G V. Assessment of pharmacy student professionalism across a curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(4):1–5. doi: 10.5688/ajpe740462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Oath of a Pharmacist. Developed by the American Pharmaceutical Association Academy of Students of Pharmacy/ American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Council of Deans (APhA-ASP/AACP-COD) Task Force on Professionalism; June 26, 1994. Revised by AACP House of Delegates July 2007.

- 37. Pharmacists Code of Ethics. Adopted by the membership of the American Pharmacists Association; October 27, 1994.

- 38.Chisholm MA, Cobb H, Duke L, McDuffie C, Kennedy WK.Development of an instrument to measure professionalism Am J Pharm Educ 200670(4)Article 85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]