Abstract

Introduction

Subjective cognitive decline (SCD) may indicate unhealthy cognitive changes, but no standardized SCD measurement exists. This pilot study aimed to identify reliable SCD questions.

Methods

A total of 112 cognitively normal (NC; 76 ± 8 years; 63% female), 43 mild cognitive impairment (MCI; 77 ± 7 years; 51% female), and 33 diagnostically ambiguous participants (79 ± 9 years; 58% female) were recruited from a research registry and completed 57 self-report SCD questions. Psychometric methods were used for item reduction.

Results

Factor analytic models assessed unidimensionality of the latent trait (SCD); 19 items were removed with extreme response distribution or trait-fit. Item response theory (IRT) provided information about question utility; 17 items with low information were dropped. Post hoc simulation using computerized adaptive test (CAT) modeling selected the most commonly used items (n = 9 of 21 items) that represented the latent trait well (r = 0.94) and differentiated NC from MCI participants (F [1, 146] = 8.9, P = .003).

Discussion

IRT and CAT modeling identified nine reliable SCD items. This pilot study is a first step toward refining SCD assessment in older adults. Replication of these findings and validation with Alzheimer's disease biomarkers will be an important next step for the creation of a SCD screener.

Keywords: Subjective cognitive decline, Item response theory, Factor analysis, Computerized adaptive testing, Psychometrics, Mild cognitive impairment

1. Introduction

Emerging evidence suggests that subjective cognitive decline (SCD), or a self-reported concern regarding a change in cognition, may represent a clinically relevant change in cognitive health, such as early Alzheimer's disease (AD) or unhealthy brain aging [1]. Recent work has linked SCD with markers of AD pathology, including smaller medial temporal lobe volumes on magnetic resonance imaging [2], amyloid burden quantified by positron emission tomography [3], and postmortem neuropathology [4]. SCD predicts cognitive decline [5], [6], incident mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [7], and incident dementia [7], [8] in nondemented older adults.

Not all studies to date support SCD as a marker of brain health [9], [10], [11] and there are several explanations for such variability. First, SCD is prevalent among older adults regardless of cognitive status [12]. Current SCD assessment methods lack specificity with as many as 95% of elders endorsing cognitive changes [13]. Such poor specificity prevents effective identification of individuals at risk for cognitive decline. Another explanation for discrepant SCD findings in the literature is the lack of standardized definition and the variable methods used to assess SCD. SCD measurement can vary based on the number of questions used (i.e., a single question [14] vs. multiple questions [15]) or based on the referent for defining decline (i.e., compared with one's own past abilities [16], compared with one's peers [17], or functional ability [18]). Given the variability in assessment methods, it is not surprising that different SCD questions have diverse associations with markers of brain health [19].

The longstanding absence of a standard SCD definition has brought about inconsistent utilization of SCD methods in both research and clinical practice. Furthermore, the lack of operationalization for SCD is in stark contrast to other markers of early AD pathology. First, accepted standards now exist for classifying elders as “amyloid positive” using either in vivo amyloid imaging [20] or amyloid-β42 values quantified by cerebral spinal fluid [21]. Similarly, there are standard structural neuroimaging markers of AD pathology, such as medial temporal lobe atrophy [22], and Food and Drug Administration-approved software is available to empirically define atrophy consistent with AD in clinical practice [23]. Finally, there is consensus on how to assess and define cognitive impairment in AD and MCI (i.e., impairment in a standard set of domains, such as memory, language, and executive functioning, is demarcated as 1.5 standard deviations below the normative mean) [24].

In light of growing support that SCD is a marker of unhealthy brain aging (e.g., SCD is a criterion for the MCI diagnosis [24]), efforts are underway to establish a standard method for defining SCD [25] to strengthen its utility in early AD detection. One proposed definition for SCD includes the following criteria: (1) self-experienced decline in cognitive capacity compared with a previous state and (2) normal objective cognitive functioning in the absence of MCI, dementia, or another symptom-explaining etiology. Although these criteria were defined for research purposes, a measure that has been validated and detects a threshold of SCD implicating a pathologic process would have broad implications. Clinically, such a tool would offer a quick and cost-effective screener for adults aged >65 years that triggers a more indepth cognitive assessment (e.g., administration of Montreal Cognitive Assessment or specialty referral for a memory loss workup). In research settings, such a screener could provide an efficient means for enriching research studies with prodromal AD individuals. To alleviate patient and clinician burden when administering the tool, a shortened questionnaire maintaining maximal precision in measuring SCD is desirable.

With a proposed criteria for SCD defined, the present study aimed to enhance ongoing efforts and operationalize the assessment of SCD by identifying questions that most reliably capture SCD. We use in succession a series of psychometric modeling techniques commonly used for data reduction (i.e., factor analysis [26]), item response theory (IRT) [27], and adaptive testing (i.e., computerized adaptive testing [CAT] [28]) to select a small but reliable subset of SCD items from a larger question bank. We hypothesized that the combination of these statistical modeling efforts would yield a subset of 5–10 items, which could be piloted as a short SCD questionnaire or screener. This study represents an important contribution to ongoing efforts to create a brief and efficient SCD tool and will support further endeavors to define and standardize SCD in cognitive aging.

2. Methods

Participants were recruited from the Boston University Alzheimer's Disease Center Registry. As previously described [29], this cohort includes adults aged ≥65 years who undergo a standard evaluation annually, including clinical interview, medical history, neurologic examination, and neuropsychological evaluation as part of the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center uniform data set [30]. The study was approved by our institutional review board.

The present study recruited 266 individuals free of dementia (i.e., diagnosed as cognitively normal [NC], MCI, or ambiguous) at their last annual visit before January 12, 2010. Cognitive diagnoses are based on a multidisciplinary consensus team using information from the comprehensive standard evaluation. NC was defined by (1) clinical dementia rating (CDR) [31] = 0 (no dementia); (2) no deficits in activities of daily living directly attributable to cognitive impairment; (3) no evidence of cognitive impairment defined as performance on neuropsychological tests within 1.5 standard deviations of the age-adjusted normative mean [32] on tests assessing language, attention, memory, and executive functioning; and (4) no cognitive complaint. MCI was based on Peterson et al. [33] criteria and defined as (1) CDR ≤0.5 (reflecting at most mild impairment), (2) relatively spared activities of daily living, (3) objective cognitive impairment in at least one cognitive domain (i.e., performances >1.5 standard deviations of the age-adjusted normative mean) or a significant decline over time on the neuropsychological evaluation, (4) report of a cognitive change by the participant or informant (i.e., endorsement of cognitive change as assessed by a brief questionnaire) or as observed by a clinician, and (5) absence of dementia. Of note, the subjective cognitive change questions used for consensus diagnostic purposes were not included in the current scale development activities. Individuals were classified as ambiguous if they were free of dementia but did not meet all criteria for either NC or MCI (i.e., cognitive impairment but no complaint or significant report of cognitive change but normal objective neuropsychological performance).

Between January 6, 2011 and January 12, 2011, all 266 nondemented participants were mailed a 57-item SCD questionnaire, of which 191 participants completed and returned. The 57 SCD items were derived from publically available tools assessing memory changes, including the everyday cognition questionnaire [18], memory functioning questionnaire [34], and individual SCD questions drawn from the literature [12]. Response options were dichotomous (yes/no) for 43 questions and Likert scale (i.e., always, sometimes, or never a problem; major, minor, or no problems) for 14 questions (Table 1 lists all SCD items). Responses to these SCD items were not used in the diagnostic determination.

Table 1.

Subjective cognitive decline questions, endorsement rates, and item response theory parameters

| Question number | SCD question | Response choices | Response % |

P value∗ | Discrimination | Difficulty | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC, n = 115 | MCI, n = 43 | ||||||

| 1. | Do you think you have problems with your memory? | Yes No |

50 50 |

79 21 |

<.01 | 4.19 | −0.10 |

| 2. | Do you have difficulty remembering a conversation from a few days ago? | Yes No |

26 74 |

37 63 |

.20 | 1.43 | 1.36 |

| 3. | Do you have complaints about your memory in the last 2 years? | Yes No |

40 60 |

47 53 |

.45 | 2.35 | 0.93 |

| 4. | How often is the following a problem for you: Personal dates (e.g., birthdays) | Always Sometimes Never |

56 39 5 |

35 58 7 |

.06 | 1.17 | 1.89† |

| 5. | How often is the following a problem for you: Phone numbers you use frequently | Always Sometimes Never‡ |

66 32 4 |

60 40 0 |

.30 | 1.28 | 0.96 |

| 6. | On a whole, do you think that you have problems remembering things that you want to do or say? | Yes No |

34 66 |

46 54 |

.18 | 2.15 | 1.21 |

| 7. | How often is the following a problem for you: Going to the store and forgetting what you wanted to buy | Always Sometimes Never‡ |

40 58 0 |

30 70 0 |

.33 | 1.01 | −0.41 |

| 8. | Do you think that your memory is worse than 5 years ago? | Yes No |

57 43 |

78 22 |

.02 | 2.62 | −0.44 |

| 9. | Do you feel you are forgetting where things were placed? | Yes No |

29 71 |

37 63 |

.30 | 1.96 | 1.57 |

| 10. | How often is the following a problem for you: Knowing whether you've already told someone something | Always Sometimes Never |

35 58 7 |

19 79 2 |

.05 | 1.22 | 1.51† |

| 11. | Overall, do you feel you can remember things as well as you used to? | Yes No |

66 34 |

88 12 |

<.01 | 3.24 | −1.50 |

| 12. | Has your memory changed significantly? | Yes No |

12 88 |

24 75 |

.06 | 2.79 | 3.81 |

| 13. | Do you feel that you have more memory problems than most? | Yes No |

8 92 |

21 79 |

.03 | 2.29 | 3.89 |

| 14. | Do memory problems make it harder to complete tasks that used to be easy? | Yes No |

13 87 |

24 76 |

.09 | 3.25 | 3.88 |

| 15. | Do you have more trouble remembering things that have happened recently? | Yes No |

18 82 |

29 71 |

.11 | 1.79 | 2.07 |

| 16. | Do you notice yourself repeating the same question or story? | Yes No |

20 80 |

16 84 |

.63 | 1.06 | 1.95 |

| 17. | Do you lose objects more often than you did previously? | Yes No |

24 76 |

33 67 |

.24 | 1.80 | 1.82 |

| 18. | Do you feel you are unable to recall the names of good friends? | Yes No |

14 86 |

33 67 |

<.01 | 1.31 | 2.10 |

| 19. | On a whole, do you think that your memory is good or poor? | Good Poor |

14 86 |

20 80 |

.39 | 2.01 | 2.85 |

| 20. | How often is the following a problem for you: Things people tell you | Always Sometimes Never‡ |

37 63 0 |

21 74 0 |

.07 | 1.40 | −0.86 |

| 21. | How often is the following a problem for you: Words | Always Sometimes Never‡ |

25 70 5 |

23 72 5 |

.95 | 1.12 | −1.22 |

| 22. | Do you think that your memory is worse than 2 years ago?§ | Yes No |

28 72 |

57 43 |

<.01 | 2.37 | 1.42 |

| 23. | Do you have difficulty recalling the date or day of the week?§ | Yes No |

10 90 |

24 76 |

.02 | 1.55 | 2.73 |

| 24. | Do you have trouble remembering things from one moment to the next?§ | Yes No |

19 81 |

26 74 |

.35 | 1.97 | 2.30 |

| 25. | Do other people say you ask the same question or repeat the same story?§ | Yes No |

10 90 |

14 86 |

.44 | 0.96 | 2.52 |

| 26. | Do you often have trouble finding the word you want to use in everyday conversation?§ | Yes No |

47 53 |

47 53 |

.96 | 1.28 | 0.35 |

| 27. | Do you have any trouble following the plot of a story you are reading/have read?§ | Yes No |

14 86 |

29 71 |

.04 | 1.69 | 2.35 |

| 28. | Do you have difficulty in remembering 2 or 3 items to buy when shopping if you don't have a list?§ | Yes No |

29 71 |

49 51 |

.02 | 1.41 | 1.09 |

| 29. | Do you have difficulty in remembering to turn off the stove or lights?§ | Yes No |

11 89 |

14 86 |

.55 | 2.13 | 3.68 |

| 30. | Do you have difficulty remembering medical appointments?§ | Yes No |

11 89 |

9 91 |

.72 | 1.33 | 2.93 |

| 31. | Are you able to remember appointments without writing them down or using a calendar?§ | Yes No |

72 28 |

74 26 |

.76 | 0.81 | −0.97 |

| 32. | How often is the following a problem for you: Phone numbers you've just checked§ | Always Sometimes Never |

32 62 6 |

23 67 9 |

.48 | 0.86 | 1.17† |

| 33. | How often is the following a problem for you: Keeping up correspondence§ | Always Sometimes Never |

59 37 4 |

47 40 14 |

.08 | 0.97 | 1.77† |

| 34. | How often is the following a problem for you: Beginning to do something and forgetting what you were doing§ | Always Sometimes Never‡ |

45 52 3 |

30 67 2 |

.22 | 0.89 | −0.31 |

| 35. | Do you have problems with your memory compared to the way it was 1 year ago?¶ | Major problems Minor problems No problems‡ |

54 44 2 |

31 69 0 |

.02 | 2.06 | 0.25 |

| 36. | Has your memory changed?¶ | Yes No |

69 31 |

93 7 |

<.01 | 2.59 | −1.68 |

| 37. | Do you have difficulty with your memory?¶ | Yes No |

43 57 |

63 37 |

.03 | 2.82 | 0.68 |

| 38. | If you have memory difficulties, do you think they are significant?¶ | Yes No |

11 88 |

26 74 |

.01 | 2.49 | 3.40 |

| 39. | I don't remember things as well as I used to.¶ | Agree Disagree |

70 30 |

80 20 |

.21 | 2.31 | −1.47 |

| 40. | Do you consider your own memory to be worse than others that are your same age?¶ | Yes No |

10 90 |

21 79 |

.09 | 1.77 | 2.99 |

| 41. | Do you ever have difficulty remembering an event that occurred last week?¶ | Yes No |

25 75 |

38 62 |

.10 | 1.48 | 1.42 |

| 42. | Do you have difficulty remembering where you placed objects (i.e., keys, wallet, glasses)?¶ | Yes No |

46 54 |

49 51 |

.72 | 0.74 | 0.27 |

| 43. | Are you worse at remembering where belongings are kept?¶ | Yes No |

11 89 |

26 74 |

.03 | 2.11 | 2.99 |

| 44. | Do you have difficulty recalling names of family (children, grandchildren, siblings)?¶ | Yes No |

8 92 |

26 74 |

<.01 | 1.38 | 2.59 |

| 45. | Do you have difficulty remembering the phone numbers of your own children?¶ | Yes No |

35 | 36 64 |

.92 | ||

| 46. | How often is the following a problem for you: Losing the train of through in conversation¶ | Always Sometimes Never‡ |

45 51 3 |

26 74 0 |

.02 | ||

| 47. | If you have memory difficulties, are they concerning you?¶ | Yes No |

27 73 |

47 53 |

.02 | ||

| 48. | Do you have problems with your memory compared to the way it was 5 years ago?¶ | Major problems Minor problems No problems |

37 57 6 |

17 69 14 |

.03 | ||

| 49. | Do you have problems with your memory compared to the way it was 10 years ago?¶ | Major problems | 29 62 9 |

17 55 29 |

<.01 | ||

| Minor problems | |||||||

| No problems | |||||||

| 50. | Do you have problems with your memory compared to the way it was 20 years ago?¶ | Major problems | 27 60 13 |

14 53 33 |

.01 | ||

| Minor problems | |||||||

| No problems | |||||||

| 51. | Do you feel that your everyday life is difficult now due to your memory decline?# | Yes No |

4 96 |

10 90 |

.22 | ||

| 52. | Do you feel you are unable to follow a conversation?# | Yes No |

5 95 |

17 83 |

.02 | ||

| 53. | Do you talk less because of memory or word-finding difficulties?# | Yes No |

6 94 |

14 86 |

.11 | ||

| 54. | Have you become lost driving or walking in areas near your home?# | Yes No |

3 97 |

5 95 |

.52 | ||

| 55. | Have you been unsure of how to navigate to a familiar location (grocery store, pharmacy)?# | Yes No |

3 97 |

5 95 |

.51 | ||

| 56. | Do you have difficulty recognizing familiar people?# | Yes No |

8 92 |

7 93 |

.86 | ||

| 57. | Do you have trouble remembering social arrangements?# | Yes No |

6 94 |

12 88 |

.25 | ||

Abbreviations: SCD, subjective cognitive decline; NC, normal control; MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

NOTE. *P value is from Pearson test comparing endorsement/response rates of each item between diagnostic groups.

Difficulty parameter is an average of the Likert-scale responses.

Likert-scale response was collapsed into dichotomous response due to low response pattern.

Items dropped because of low factor loadings.

Item dropped because of duplicative or dependent content.

Item dropped because of extreme response profile.

To assess any differences between participants who returned the survey versus those that did not return the survey, baseline clinical characteristics were compared between responder status groups using Welch's t test for continuous variables (because only aggregated data were available for nonresponders) and Pearson's χ2 test for categorical variables. For responders (n = 191), baseline characteristics and SCD items were compared across diagnostic groups (NC, MCI, and ambiguous) using Pearson's χ2 test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables. We chose the Wilcoxon test because it does not impose normality assumptions and is less sensitive to the effects of outliers. Characteristics included age, sex, race, education, length in the cohort, and mini-mental state examination (MMSE [35]) score.

The analytical plan involved a series of sequential steps and applied only to the responder group (n = 191). First, using the entire 57-item SCD bank, items with three possible response choices (i.e., Likert-type scale) were collapsed into dichotomous items if one response choice had less than 5% proportion of endorsement or response. Dichotomous or Likert-scale items with extreme response profiles, or endorsement rate of ≥90% or ≤10%, were removed.

To assess unidimensionality, one important assumption of IRT, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted. Items were then removed that did not load highly on any factors of EFA, had duplicate content, or were dependent on a response from another item. Residual item correlations were examined to assess the assumption of local independence, another important assumption of IRT. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was completed to assess the unidimensionality of the remaining questions. The resultant group of items represented the bank of possible questions to select. To refine the inventory and develop a precise instrument, IRT models were used to obtain item parameters for each individual item. Specifically, IRT-graded response modeling for ordinal polytomous data were fitted to the bank because all questions had two or three response options with graded SCD severity. IRT modeling provided discrimination and difficulty parameters and item information curves for individual items and test information curves (TIC) for compiled sets of questions. All items were anchored using a mean of 0. IRT θ scores for participants with complete data were also obtained using empirical Bayes estimates.

To identify a reduced number of items from this bank, post hoc simulations using CAT models [36], [37] were performed using discrimination and difficulty parameters from the IRT model. Items most frequently administered in the CAT simulation were incorporated for possible inclusion in the final tool. Then, using the most frequently used items, we calculated TIC curves for each possible iteration of the questions. The questions with the highest information at the median level of MCI SCD ability were selected. For all the aforementioned steps, the entire sample was used (n = 191). Finally, to assess the clinical utility of the SCD bank and the reduced number of items (i.e., the brief screening tool), the total scores of the bank and reduced selection (summation of the raw scores) were compared between only the NC and MCI participants using Wilcoxon tests. Cohen's D effect sizes were calculated. All analyses were conducted using R (version 3.1.2, www.r-project.org) with package “ltm” (function “grm” for IRT) and package “sem” (function “cfa” for CFA) packages [38] and FIRESTAR [36].

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

Survey respondents (n = 191) and non-respondents (n = 75) were comparable for sex (χ2 [1, 266] = 0.42; P = .52), time in cohort (t [1, 147] = 0.50; P = .62), and MMSE score (t [1, 116] = 1.35, P = .18). However, responders were significantly different from nonresponders on age (t [1, 146] = 2.00; P = .048), education (t [1, 119] = 2.44; P = .02), race (χ2 [1, 266] = 7.6; P < .01), and cognitive diagnosis (χ2 [1, 266] = 8.1; P = .02).

Of the respondents, participants included 115 NC, 43 MCI, and 33 ambiguous individuals. Between-group comparisons by diagnosis suggested no differences in age (F [2, 188] = 1.5; P = .23), sex (χ2 = 2; P = .36), race (χ2 [1, 191] = 3.1; P = .21), education (F [2, 188] = 0.33; P = .72), or length in cohort (F [2, 188] = 2.9, P = .06); however, there was a main effect for MMSE score (F [2, 188] = 11.0; P < .001). All results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics by responder status

| Characteristics | Responders |

Nonresponders, n = 75 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC, n = 115 | MCI, n = 43 | Ambiguous, n = 33 | Total, n = 191 | ||

| Age, y | 75.9 ± 7.5 | 77.0 ± 6.5 | 78.5 ± 8.5 | 76.6 ± 7.5 | 75.3 ± 7.1** |

| Sex, % female | 63 | 51 | 58 | 60 | 64 |

| Race, % white | 83 | 70 | 79 | 79 | 63** |

| Education, y | 16.4 ± 2.7 | 15.9 ± 2.6 | 16.1 ± 2.6 | 16.2 ± 2.6 | 15.3 ± 3.2** |

| Length in cohort, y | 8.1 ± 2.6 | 7.5 ± 2.0 | 7.7 ± 2.7 | 7.9 ± 2.5 | 7.9 ± 2.2 |

| MMSE, total score | 29.2 ± 1.0 | 28.1 ± 1.8 | 28.6 ± 1.0 | 28.9 ± 1.3* | 28.5 ± 1.6 |

Abbreviations: NC, normal control; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MMSE, mini-mental state examination.

NOTE. *P value between responder groups, including NC, MCI, and ambiguous, is <.05; **P value between all responders and nonresponders is <.05.

3.2. Unidimensionality and logical dependence assessment

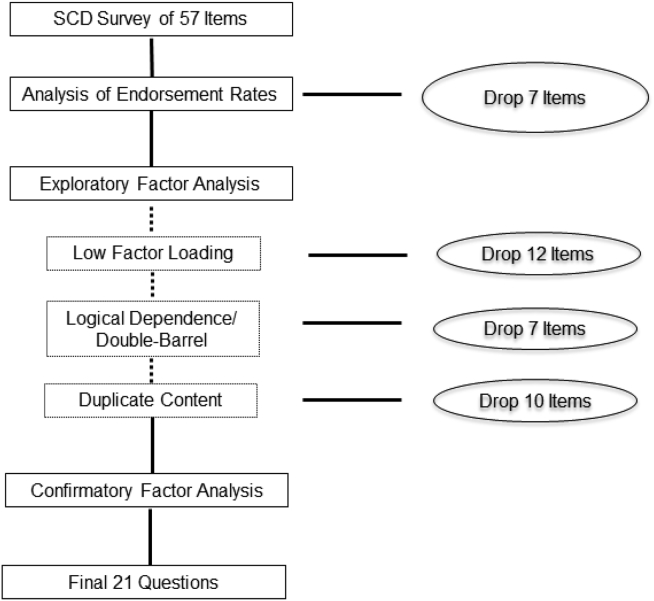

The frequencies of item responses by NC and MCI are presented in Table 1. Comparison between the two diagnostic groups was conducted using Pearson's χ2 test. Seven 3-point Likert-scale items had one response with less than 5% proportion and, thus, were collapsed into dichotomous items (i.e., 5, 7, 20, 21, 34, 35, and 46). Seven dichotomous items had extreme response profiles (i.e., more than 90% endorsement) and were excluded because of low variation (i.e., items 51–57; Table 1). An EFA on the remaining 50 items yielded the first eigenvalue of 13.69, followed by a second eigenvalue of 2.80 (ratio 1:2 = 4.88), suggesting a strong general factor. Parallel analysis was used to determine the number of factors, which suggested that up to eight additional factors could be extracted from the inventory. Then, an EFA with eight factors were conducted. Twelve items (items 22–34) with factor loadings less than 0.4 on any of the eight factors were removed. High residual correlations were noted possibly due to local dependence in logic or duplicate content, suggesting poor local dependence and the need for further item reduction/removal. For example, item 47 (“If you have memory difficulties, are they concerning you?”) is dependent on the answer to item 37 (“Do you have difficulty with your memory?”). Item 29 “Do you have difficulty in remembering to turn off the stove or lights?” could be considered double-barreled (i.e., relates to two different concepts). We excluded six dependent or double-barreled items (items 36–41). Redundant content across questions was noted, such as item 11 “Overall, do you feel you can remember things as well as you used to?” and item 45 “I don't remember things as well as I used to.” We removed 10 questions with redundant content (items 35, and 42–50) using IRT parameter estimates (in the following) and selecting the item with the most item information at the median latent trait level of the MCI group. Finally, a CFA one-factor model was fitted to the remaining 21 items. Goodness-of-fit indices were 0.05 for the root mean square error of approximation, 0.93 for the Tucker-Lewis index, and 0.95 for the comparative-fit index. The residual correlations of those remaining 21 items from the one-factor CFA ranged from −0.27 to 0.36 with only one residual correlation of included items that was larger than 0.3 (i.e., r = 0.36 for items 12 and 13), suggesting no local dependence in the sample. An alternative empirically derived bi-factor CFA model was also fitted. Factor loadings on the primary factor of the two CFA models were quite close to each other. Factor loadings on the secondary factor were less than the corresponding loadings on the primary factor in the bi-factor CFA model. These results suggested essential unidimensionality of the SCD bank with 21 items. See Fig. 1 for description of the item reduction process.

Fig. 1.

Item reduction process. Abbreviations: SCD, subjective cognitive decline.

3.3. IRT parameter estimates and scoring of the bank

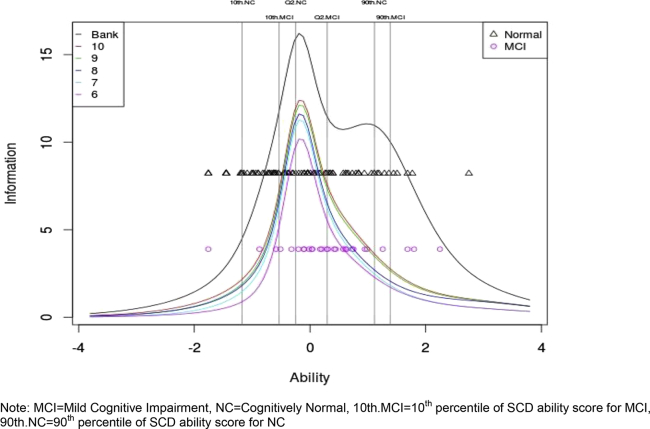

IRT models were fit to the SCD items. The difficulty parameter estimates (relative difficulty of getting an item right) and discrimination parameter estimates (usefulness of the item in distinguishing among people with different latent trait; Table 1) were obtained. The IRT θ score is a measure of the latent trait where higher θ score indicates more severe SCD. The item with the lowest difficulty, which was the easiest to endorse, was item 11 “Overall, do you feel you can remember things as well as you used to?” The item with the highest difficulty was item 13 “Do you feel you have more memory problems than most?” which is more likely to be endorsed by participants with higher latent trait, i.e., more SCD. θ scores generated from IRT across the items ranged from −1.76 to 2.75 with a mean of −0.01 ± 0.9 and median of 0.01 (25th percentile = −0.64, 75th percentile = 0.6) for the entire sample (n = 191). The mean θ score was −0.12 ± 0.90 (25th percentile = −0.71, median = −0.25, 75th percentile = 0.39) for NC and 0.34 ± 0.83 (25th percentile = −0.1, median = 0.30, 75th percentile = 0.83) for MCI. The θ score of MCI was significantly higher than NC with mean difference of 0.46 (P = .009). See Fig. 2 for depiction of median and 10th and 90th percentile of TICs for NC and MCI for the total bank.

Fig. 2.

Test information curves for the bank and selected SCD items. Abbreviations: SCD, subjective cognitive decline; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; NC, cognitively normal; 10th MCI, 10th percentile of SCD ability score for MCI; 90th NC, 90th percentile of SCD ability score for NC.

3.4. A brief screening tool (using CAT models)

To reduce the administrative burden, a shortened list of SCD items was selected from the questionnaire bank using post hoc simulations from CAT modeling. First, simulated responses for the 21 SCD items were generated for 10,000 participants using discrimination and difficulty parameter estimates from the IRT model. Next, the questionnaire was “administered” to each participant using CAT and the specific items given and order of administration were recorded. Finally, frequencies of administered items based on the 10,000 simulated participants were obtained, and the top 10 items with highest frequencies were retained (ordered by frequency: Table 3, questions 1–10). The TICs of the bank and a series of subquestionnaires (i.e., the top 5–10 selected items) were generated (Fig. 2). The TICs are nested because the information monotonically increases with more items added. Larger information corresponded to greater precision in measuring SCD. Between NC and MCI, most overlapping θ scores (−0.53 to 1.11) correspond to the top of the TICs and reflect the highest information values, indicating the bank was most reliable at measuring levels of SCD severity where NC and MCI participants might share similar levels of SCD. There was minimal difference between TICs of the 10- and 9-item shortened questionnaire, although the 9-item TIC encompassed a lower overall θ score. However, the 8-item TIC is much lower than the 9-item TIC. When examining the association between different scores, the traditional 21-item total score was strongly and significantly correlated with both the 10-item (r = 0.96, P < .001) and 9-item total scores (r = 0.95, P < .001). The 9-item total score was highly correlated with the latent trait (i.e., θ of the bank, r = 0.95, P < .001). On the basis of these analyses, the top nine items were selected for inclusion into a brief screening tool.

Table 3.

SCD 21-item bank and top nine selected SCD items

| Question number | SCD question |

|---|---|

| 1. | Do you think you have problems with your memory? |

| 2. | Do you have difficulty remembering a conversation from a few days ago? |

| 3. | Do you have complaints about your memory in the last 2 years? |

| 4. | How often is the following a problem for you: Personal dates (e.g., birthdays) |

| 5. | How often is the following a problem for you: Phone numbers you use frequently |

| 6. | On a whole, do you think that you have problems remembering things that you want to do or say? |

| 7. | How often is the following a problem for you: Going to the store and forgetting what you wanted to buy |

| 8. | Do you think that your memory is worse than 5 years ago? |

| 9. | Do you feel you are forgetting where things were placed? |

| 10. | How often is the following a problem for you: Knowing whether you've already told someone something |

| 11. | Overall, do you feel you can remember things as well as you used to? |

| 12. | Has your memory changed significantly? |

| 13. | Do you feel that you have more memory problems than most? |

| 14. | Do memory problems make it harder to complete tasks that used to be easy? |

| 15. | Do you have more trouble remembering things that have happened recently? |

| 16. | Do you notice yourself repeating the same question or story? |

| 17. | Do you lose objects more often than you did previously? |

| 18. | Do you feel you are unable to recall the names of good friends? |

| 19. | On a whole, do you think that your memory is good or poor? |

| 20. | How often is the following a problem for you: Things people tell you |

| 21. | How often is the following a problem for you: Words |

Abbreviation: SCD, subjective cognitive decline.

3.5. Clinical utility of SCD scores

The total score from the 21-item bank and the total score from the 9-item brief screening tool were evaluated between NC and MCI participants. The 21-item total bank score (Table 4) has a median of 6.0 (25th percentile = 3.5, 75th percentile = 11.5) for NC and median of 9.5 (25th percentile = 7.0, 75th percentile = 13.0) for MCI and significantly differed between groups (F [1, 117] = 5.8; P = .017). The 9-item total score had a median of 3.0 (25th percentile = 1.0, 75th percentile = 6.0) for NC and median of 5.0 (25th percentile = 3.0, 75th percentile = 7.0) for MCI and also significantly differed between groups (F [1, 117] = 6; P = .015; Table 4), suggesting clinical utility of these items. See Table 4 for depiction of effect sizes between diagnostic groups and mean SCD scores.

Table 4.

Clinical utility of the SCD bank and shortened item list

| Selected SCD Items | NC, n = 91 |

MCI, n = 28 |

P value* | Effect size | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | 25th percentile | 50th percentile | 75th percentile | Mean (SD) | 25th percentile | 50th percentile | 75th percentile | |||

| Theta ability of the bank | −0.1 ± 0.9 | −0.7 | −0.25 | 0.4 | 0.3 ± 0.8 | −0.1 | 0.3 | 0.7 | <.01 | 0.47 |

| Total score of bank (21 items) | 7.7 ± 5.1 | 3.5 | 6.0 | 11.5 | 10.1 ± 4.9 | 7.0 | 9.5 | 13.0 | .02 | 0.48 |

| Total score of top 10 items | 4.4 ± 3.1 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 7.0 | 5.8 ± 2.8 | 3.8 | 6.0 | 8.0 | .02 | 0.47 |

| Total score of top nine items | 3.8 ± 2.9 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 5.1 ± 2.4 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 7.0 | .02 | 0.49 |

| Total score of top eight items | 3.5 ± 2.6 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 4.8 ± 2.3 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 6.2 | .02 | 0.53 |

| Total score of top seven items | 2.8 ± 2.4 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 3.9 ± 2.1 | 2.8 | 4.0 | 5.2 | .02 | 0.49 |

| Total score of top six items | 2.2 ± 2.1 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 3.1 ± 1.9 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 | .03 | 0.45 |

| Total score of top five items | 1.9 ± 1.8 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 2.7 ± 1.6 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 4.0 | .02 | 0.47 |

Abbreviations: SCD, subjective cognitive decline; NC, cognitively normal; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; SD, standard deviation.

NOTE. *P value for Wilcoxon test used to compare diagnostic groups; effect size presented as Cohen's D.

4. Discussion

In a cohort of nondemented older adults, we used advanced statistical methods, such as factor analysis, IRT, and CAT modeling, to identify a subset of reliable SCD questions for the purpose of creating a SCD screener. Among individuals with NC and MCI, results suggest that SCD may be adequately assessed using a smaller subset of items (i.e., from an initial larger selection of SCD questions). SCD items were chosen here because they possessed specific psychometric properties (i.e., reliability) necessary for the creation of a screening tool to identify individuals with clinically relevant levels of SCD. Although replication and validation of these findings are needed, this initial study represents an early stage effort to operationalize SCD assessment to create a screening tool for general use.

The nine questions identified in the current results are characterized by different SCD domains, such as global memory functioning, temporal comparisons, and more specific items querying for an individual's ability to complete daily or routine activities. For example, global memory functioning items include “Do you think you have problems with your memory?” and “On a whole, do you think that you have problems remembering things that you want to do or say?” Endorsement of similar global memory functioning questions has been linked to smaller medial temporal lobe volumes [14] and poorer cognitive performances [9], [39]. Temporal comparison questions include “Do you have complaints about your memory in the last 2 years?” and “Do you think that your memory is worse than 5 years ago?” Using a time referent as a benchmark for change is common in other SCD methodologies, such as the cognitive change index [2]. The final domain of SCD items queries about the individual's ability to complete daily or routine activities, such as “Do you have difficulty remembering a conversation from a few days ago?,” “How often is the following a problem for you: Personal dates (e.g., birthdays),” “How often is the following a problem for you: Phone numbers you use frequently,” “How often is the following a problem for you: Going to the store and forgetting what you wanted to buy”, and “Do you feel you are forgetting where things were placed?” These daily activities–based questions have also been used in previous SCD analyses and endorsement is related to amyloid positivity [40].

An important next step is relating the SCD items identified here to cognitive, neuroimaging, and biospecimen markers of unhealthy brain aging to ensure the questionnaire is valid. Although this important step is beyond the scope of the present article, previous research using similar items offers preliminary support that the identified SCD questions may have some validity. For example, NC [9], [41] or MCI individuals [42] who endorse the question “Do you think you have problems with your memory?” (i.e., question 1 of the present study) showed poorer episodic memory performance. Similarly, in nondemented older adults the question “Do you have memory impairment?” (i.e., analogous to questions 1, 3, and 8 of the present study) was related to lower objective cognitive performance [39]. NC older adults who endorsed the question “Do you feel like your memory is becoming worse,” (i.e., similar to item 8 of the present study) evidenced smaller medial temporal lobe volumes [14] and poorer verbal episodic memory performance [16]. NC participants endorsing the item “Have you had memory loss in the past year” or “Do you have complaints about your memory” (i.e., questions 1 and 3 of the present study) are at increased risk of developing dementia [43], [44]. Collectively, these prior studies offer some preliminary support for the validity of the questions identified in the present study.

Despite converging evidence, not all existing literature supports the potential validity of the items selected here. For example, the question “Do you feel that you have more memory problems than most?” (item 13 of the current bank) was not one of the SCD items selected by our advanced psychometric modeling techniques despite existing evidence that this question may be related to poorer episodic memory in MCI [45]. The discrepancy in current versus past work suggests that although this question is valid and one possibility for measuring SCD, the item may not be the most reliable method for assessing SCD. Alternatively, it may be more valid in assessing SCD in MCI as compared with cognitively intact older adults.

Coupled with recent work from Snitz et al. [46], examining the utility of IRT and related scoring techniques to refine the assessment of SCD, the current findings highlight that IRT is a useful method for identifying a reliable set of questions from a larger bank. The present study used a well-characterized sample (i.e., standardized assessment and diagnostic procedures) of nondemented older adults and highlighted the potential value of a brief SCD screener to distinguish worried well from truly at-risk older adults. Furthermore, the current results suggest that using a simple summation or total score can differentiate NC from MCI. This initial effort closely aligns with an important international initiative to define and standardize SCD [25]. Thus, further work is needed to replicate our findings and validate selected items with other markers of unhealthy brain aging, such as cognitive performance, diagnosis, or other biomarkers. With the new definition of SCD described [25], concurrent research is needed to create and validate new tools for use in different populations for enhanced identification of individuals at risk for cognitive impairment.

Despite numerous strengths, several key limitations must be considered. First, the sample size is small, particularly when using IRT. Second, the cohort is generally well educated and predominantly white, which may limit the generalizability of findings. Third, the present study does not include an examination of the best methods for measuring informant report of cognitive decline, despite growing evidence that corroboration of SCD by a loved one may enhance clinical utility [6], [47]. Finally, our analyses are cross-sectional and limit our ability to assess the predictive ability of these SCD items with respect to cognitive performance or diagnostic conversion over time. A longitudinal study is needed to assess these important factors.

The current findings are an important step in reliably operationalizing cognitive complaint. Further research is needed to evaluate and define best practices for assessing and quantifying cognitive complaint. Such research will provide practical information and assessment tools for primary-care providers of older adults and help streamline identification of at-risk elders in research settings.

Research in context.

-

1.

Systematic review: Subjective cognitive decline (SCD) may be an early marker of unhealthy brain aging. However, review of the literature revealed no standardized means for assessing SCD and a lack of systematic identification of the best questions to measure the construct.

-

2.

Interpretation: Our findings suggest that use of quantitative methodology, such as item response theory and computerized adaptive test models, can identify a standard set of SCD items. Results highlight specific questions that may be useful in the creation of a SCD screening tool.

-

3.

Future directions: Further research is needed to replicate the findings and selected items. Validation of these questions on known markers of unhealthy brain aging will also be important to create a screener for research or clinical settings that efficiently identifies older adults at risk of cognitive impairment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by K12-HD043483 (K.A.G.); Alzheimer's Association NIRG-13-283276 (K.A.G); T32-AG036697 (K.A.G.); K23-AG030962 (Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award in Aging; A.L.J.); K24-AG046373 (A.L.J.); Alzheimer's Association IIRG-08-88733 (A.L.J.); R01-AG034962 (A.L.J.); R01-HL11516 (A.L.J.); P30-AG013846 (Boston University Alzheimer's Disease Core Center); and the Vanderbilt Memory and Alzheimer's Center.

References

- 1.Jessen F., Wiese B., Bachmann C., Eifflaender-Gorfer S., Haller F., Kolsch H. Prediction of dementia by subjective memory impairment: Effects of severity and temporal association with cognitive impairment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:414–422. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saykin A.J., Wishart H.A., Rabin L.A., Santulli R.B., Flashman L.A., West J.D. Older adults with cognitive complaints show brain atrophy similar to that of amnestic MCI. Neurology. 2006;67:834–842. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000234032.77541.a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perrotin A., Mormino E.C., Madison C.M., Hayenga A.O., Jagust W.J. Subjective cognition and amyloid deposition imaging: A Pittsburgh compound B positron emission tomography study in normal elderly individuals. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:223–229. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes L.L., Schneider J.A., Boyle P.A., Bienias J.L., Bennett D.A. Memory complaints are related to Alzheimer disease pathology in older persons. Neurology. 2006;67:1581–1585. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000242734.16663.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glodzik-Sobanska L., Reisberg B., De Santi S., Babb J.S., Pirraglia E., Rich K.E. Subjective memory complaints: Presence, severity and future outcome in normal older subjects. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24:177–184. doi: 10.1159/000105604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gifford K.A., Liu D., Carmona H., Lu Z., Romano R., Tripodis Y., Martin B., Kowall N., Jefferson A.L. Inclusion of an informant yields strong associations between cognitive complaint and longitudinal cognitive outcomes in non-demented elders. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;43:121–132. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gifford K.A., Liu D., Lu Z., Tripodis Y., Cantwell N.G., Palmisano J. The source of cognitive complaints predicts diagnostic conversion differentially among nondemented older adults. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang L., van Belle G., Crane P.K., Kukull W.A., Bowen J.D., McCormick W.C. Subjective memory deterioration and future dementia in people aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:2045–2051. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dik M.G., Jonker C., Comijs H.C., Bouter L.M., Twisk J.W., van Kamp G.J. Memory complaints and APOE-epsilon4 accelerate cognitive decline in cognitively normal elderly. Neurology. 2001;57:2217–2222. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.12.2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jorm A.F., Christensen H., Korten A.E., Jacomb P.A., Henderson A.S. Memory complaints as a precursor of memory impairment in older people: A longitudinal analysis over 7-8 years. Psychol Med. 2001;31:441–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Purser J.L., Fillenbaum G.G., Wallace R.B. Memory complaint is not necessary for diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and does not predict 10-year trajectories of functional disability, word recall, or short portable mental status questionnaire limitations. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:335–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reid L.M., Maclullich A.M. Subjective memory complaints and cognitive impairment in older people. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22:471–485. doi: 10.1159/000096295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slavin M.J., Brodaty H., Kochan N.A., Crawford J.D., Trollor J.N., Draper B. Prevalence and predictors of “subjective cognitive complaints” in the Sydney Memory and Ageing Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;18:701–710. doi: 10.1097/jgp.0b013e3181df49fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jessen F., Feyen L., Freymann K., Tepest R., Maier W., Heun R. Volume reduction of the entorhinal cortex in subjective memory impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:1751–1756. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y., West J.D., Flashman L.A., Wishart H.A., Santulli R.B., Rabin L.A. Selective changes in white matter integrity in MCI and older adults with cognitive complaints. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2012;1822:423–430. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jessen F., Wiese B., Cvetanovska G., Fuchs A., Kaduszkiewicz H., Kolsch H. Patterns of subjective memory impairment in the elderly: Association with memory performance. Psychol Med. 2007;37:1753–1762. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lam L.C., Lui V.W., Tam C.W., Chiu H.F. Subjective memory complaints in Chinese subjects with mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:876–882. doi: 10.1002/gps.1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farias S.T., Mungas D., Reed B.R., Cahn-Weiner D., Jagust W., Baynes K. The measurement of everyday cognition (ECog): Scale development and psychometric properties. Neuropsychology. 2008;22:531–544. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.22.4.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amariglio R.E., Townsend M.K., Grodstein F., Sperling R.A., Rentz D.M. Specific subjective memory complaints in older persons may indicate poor cognitive function. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1612–1617. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aizenstein H.J., Nebes R.D., Saxton J.A., Price J.C., Mathis C.A., Tsopelas N.D. Frequent amyloid deposition without significant cognitive impairment among the elderly. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1509–1517. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.11.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blennow K., Hampel H. CSF markers for incipient Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:605–613. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00530-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jack C.R., Jr., Shiung M.M., Weigand S.D., O'Brien P.C., Gunter J.L., Boeve B.F. Brain atrophy rates predict subsequent clinical conversion in normal elderly and amnestic MCI. Neurology. 2005;65:1227–1231. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000180958.22678.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brewer J.B., Magda S., Airriess C., Smith M.E. Fully-automated quantification of regional brain volumes for improved detection of focal atrophy in Alzheimer disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:578–580. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albert M.S., Dekosky S.T., Dickson D., Dubois B., Feldman H.H., Fox N.C. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jessen F., Amariglio R.E., van Boxtel M., Breteler M., Ceccaldi M., Chetelat G. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:844–852. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonald R.P. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Mahwah, NJ: 1999. Test theory: A unified treatment. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lord F.M. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 1980. Applications of item response theory to practical testing problems. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gibbons R.D., Weiss D.J., Kupfer D.J., Frank E., Fagiolini A., Grochocinski V.J. Using computerized adaptive testing to reduce the burden of mental health assessment. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:361–368. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.4.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jefferson A.L., Lambe S., Chaisson C., Palmisano J., Horvath K., Karlawish J. Clinical research participation among aging individuals enrolled in an Alzheimer's Disease Center research registry. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2011;23:443–452. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beekly D.L., Ramos E.M., Lee W.W., Deitrich W.D., Jacka M.E., Wu J. The National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center (NACC) database: The uniform data set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21:249–258. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318142774e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris J.C. The clinical dementia rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weintraub S., Salmon D., Mercaldo N., Ferris S., Graff-Radford N.R., Chui H. The Alzheimer's Disease Centers' Uniform Data Set (UDS): The neuropsychologic test battery. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:91–101. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318191c7dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petersen R.C. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256:183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilewski M.J., Zelinski E.M., Schaie K.W. The memory functioning questionnaire for assessment of memory complaints in adulthood and old age. Psychol Aging. 1990;5:482–490. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Folstein M.F., Folstein S.E., McHugh P.R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi S.W., Swartz R.J. Comparison of CAT item selection criteria for polytomous items. Appl Psychol Meas. 2009;33:419–440. doi: 10.1177/0146621608327801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi S.W., Reise S.P., Pilkonis P.A., Hays R.D., Cella D. Efficiency of static and computer adaptive short forms compared to full-length measures of depressive symptoms. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:125–136. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9560-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2010. Available at: http://www.R-project.org. Accessed October 31, 2014.

- 39.Miranda B., Madureira S., Verdelho A., Ferro J., Pantoni L., Salvadori E. Self-perceived memory impairment and cognitive performance in an elderly independent population with age-related white matter changes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2008;79:869–873. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.131078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amariglio R.E., Becker J.A., Carmasin J., Wadsworth L.P., Lorius N., Sullivan C. Subjective cognitive complaints and amyloid burden in cognitively normal older individuals. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50:2880–2886. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang P.N., Wang S.J., Fuh J.L., Teng E.L., Liu C.Y., Lin C.H. Subjective memory complaint in relation to cognitive performance and depression: A longitudinal study of a rural Chinese population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:295–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schofield P.W., Marder K., Dooneief G., Jacobs D.M., Sano M., Stern Y. Association of subjective memory complaints with subsequent cognitive decline in community-dwelling elderly individuals with baseline cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:609–615. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.5.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.St John P., Montgomery P. Are cognitively intact seniors with subjective memory loss more likely to develop dementia? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17:814–820. doi: 10.1002/gps.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geerlings M.I., Jonker C., Bouter L.M., Ader H.J., Schmand B. Association between memory complaints and incident Alzheimer's disease in elderly people with normal baseline cognition. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:531–537. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gifford K.A., Liu D., Damon S.M., Chapman W.G., Romano R.R., Samuels L.R. Subjective memory complaint only relates to verbal episodic memory performance in mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2015;44:309–318. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Snitz B.E., Yu L., Crane P.K., Chang C.C., Hughes T.F., Ganguli M. Subjective cognitive complaints of older adults at the population level: An item response theory analysis. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012;26:344–351. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3182420bdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carr D.B., Gray S., Baty J., Morris J.C. The value of informant versus individual's complaints of memory impairment in early dementia. Neurology. 2000;55:1724–1726. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.11.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]