Summary

Filamentous fungi are renowned for the production of bioactive secondary metabolites. Typically, one distinct metabolite is generated from a specific secondary metabolite cluster. Here, we characterize the newly described trypacidin (tpc) cluster in the opportunistic human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. We find that this cluster as well as the previously characterized endocrocin (enc) cluster both contribute to the production of the spore metabolite endocrocin. Whereas trypacidin is eliminated when only tpc cluster genes are deleted, endocrocin production is only eliminated when both the tpc and enc non-reducing polyketide synthase-encoding genes, tpcC and encA, respectively, are deleted. EncC, an anthrone oxidase, converts the product released from EncA to endocrocin as a final product. In contrast, endocrocin synthesis by the tpc cluster likely results from incomplete catalysis by TpcK (a putative decarboxylase), as its deletion results in a nearly 10-fold increase in endocrocin production. We suggest endocrocin is likely a shunt product in all related non-reducing polyketide synthase clusters containing homologues of TpcK and TpcL (a putative anthrone oxidase), e.g. geodin and monodictyphenone. This finding represents an unusual example of two physically discrete secondary metabolite clusters generating the same natural product in one fungal species by distinct routes.

Introduction

Fungi are well known for the ability to synthesize bioactive secondary metabolites (SMs) of diverse chemical structure and complexity. The dominant SM-producing taxa belong to several genera of filamentous ascomycetes. Secondary metabolites are generally thought to contribute to the fitness of filamentous fungi, primarily as protection from abiotic stress (e.g. melanins) and/or for niche securement or defense in conflicts with other microbes or insects (e.g. toxins) (reviewed in Rohlfs and Churchill, 2011; Scherlach et al., 2013). The same or similar metabolites can also serve as virulence factors in pathogenic fungi, including plant (Friesen et al., 2008) and animal (Dagenais and Keller, 2009) pathogens.

Aspergillus fumigatus is the primary causative agent of invasive aspergillosis (IA) among immunocompromised individuals (Brakhage, 2005; Maschmeyer et al., 2007). This species is notorious for producing a plethora of SMs (e.g. gliotoxin, helvolic acid, hexadehydroastechrome, trypacidin, endocrocin, neosartoricin, and fumagillin) shown to exhibit immunomodulatory and/or cytotoxic properties that are thought to facilitate the pathogenicity of this fungus (Amitani et al., 1995; Bok et al., 2005; 2006; Spikes et al., 2008; Lodeiro et al., 2009; Gauthier et al., 2012; Berthier et al., 2013; Chooi et al., 2013; Yin et al., 2013), although their ecological role may relate to their antimicrobial activity (Carberry et al., 2012; Kang et al., 2013) and UV protective capacity (Allam and Abd El-Zaher, 2012).

Secondary metabolism is spatially and temporally regulated in fungi with metabolites produced in different compartments of the fungal thallus (Lim and Keller, 2014; Kistler and Broz, 2015). Mycelial SMs such as gliotoxin and helvolic acid have been extensively studied over the last decades (Amitani et al., 1995; Bok et al., 2006; Spikes et al., 2008; Kwon-Chung and Sugui, 2009). However, with the exception of dihydroxynaphthalene (DHN) melanin (Jahn et al., 1997; Sugui et al., 2007; Bayry et al., 2014), the spore-borne SMs are relatively understudied, despite spores being crucial to the fungus for dispersal and colonization of new substrates.

Recent studies have identified two spore metabolites that may contribute to the virulence of A. fumigatus. Endocrocin, a spore-borne product of a non-reducing polyketide synthase (NR-PKS) in A. fumigatus, was demonstrated to inhibit neutrophil migration both in vitro and in vivo, and deletion of the endocrocin polyketide synthase-encoding encA yielded a less pathogenic strain using the Toll-deficient Drosophila model (Berthier et al., 2013). Another spore metabolite, trypacidin, was shown to exhibit cytotoxic properties against both the A549 pulmonary adenocarcinoma cell line and human bronchial epithelial cells (Gauthier et al., 2012). Interestingly, trypacidin, first isolated from A. fumigatus, was identified as an anti-protozoal agent (Balan et al., 1963; Turner, 1965), and the conidia of A. fumigatus have multiple reported defences against predation by soil amoebae (Van Waeyenberghe et al., 2013; Hillmann et al., 2015).

Despite being isolated more than 50 years ago, the genes responsible for trypacidin production in A. fumigatus have not been identified. Trypacidin is similar in structure to polyketides that belong to the clade of NR-PKSs involved in the synthesis of anthraquinone-derivatives, which include geodin in Aspergillus terreus (Nielsen et al., 2013), monodictyphenone in Aspergillus nidulans (Chiang et al., 2010; Sanchez et al., 2011; Simpson, 2012) and endocrocin in A. fumigatus (Lim et al., 2012). These NR-PKSs lack the canonical thioesterase (TE) domain responsible for releasing the nascent products from the enzyme. Instead, a separate gene encoding a metallo-β-lactamase type thioesterase (MβL-TE) is located adjacent to these NR-PKSs (Awakawa et al., 2009). These two enzymes catalyse the first steps in the biosynthesis of polyketides of this TE-less NR-PKS clade, discussed in recent reviews (Ahuja et al., 2012; Chooi and Tang, 2012). Genome mining in A. fumigatus identified three NR-PKSs, two of which have been characterized and found to synthesize endocrocin (Lim et al., 2012; Berthier et al., 2013) and neosartoricin (Chooi et al., 2013).

Here, we found that the third TE-less NR-PKS is responsible for the biosynthesis of the polyketide trypacidin. The 13-gene trypacidin (tpc) cluster is nearly identical to the 13-gene ged NR-PKS cluster, and several tpc genes also share homology with both the 12-gene mdp cluster and the 4-gene enc cluster. Unexpectedly, we found that both the tpc and enc clusters contribute to the production of endocrocin, with the former cluster ultimately producing trypacidin. Through tpc and enc gene deletions coupled with metabolite profiling of these strains, we characterized two distinct routes to endocrocin production differentiated by early enzymatic steps in their respective pathways.

Results

Identification of the trypacidin-producing gene cluster

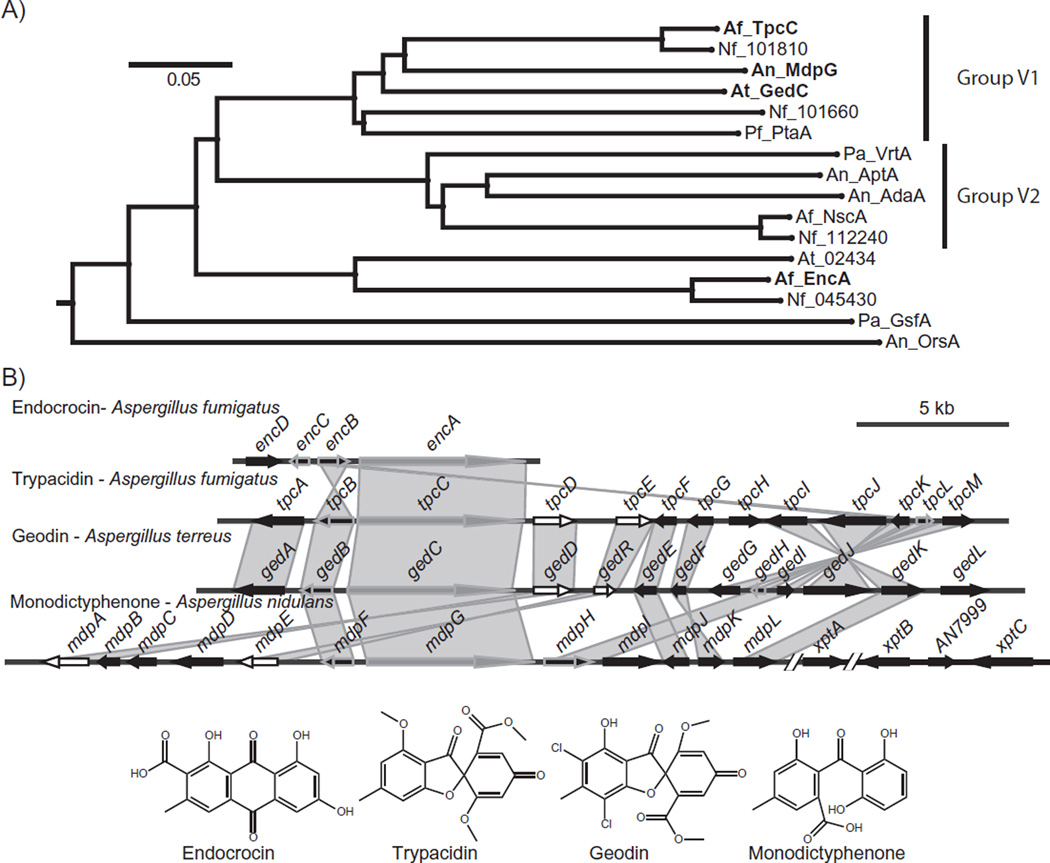

The cluster containing the NR-PKS-encoding gene AFUA_4G14560 (hereafter referred to as tpcC) was first identified as one of the SM clusters regulated by the global regulator of secondary metabolism, LaeA (Perrin et al., 2007). Analysis of the product template (PT) domain of TpcC shows that it belongs to the same clade of NR-PKS as the monodictyphenone PKS of A. nidulans (Chiang et al., 2010), the endocrocin PKS of A. fumigatus (Lim et al., 2012), and the recently described geodin PKS of A. terreus (Nielsen et al., 2013) (Fig. 1A and Table S1). The PT domains of PKSs determine the regio-selectivity of cyclization during the synthesis of the polyketide backbone (Crawford et al., 2009) and have been used for phylogenetic analyses. The phylogenetic group of PKSs to which TpcC belongs has previously been designated Group V1 (Li et al., 2011), a subdivision of Group V (Li et al., 2010) which, with a few exceptions, make a C6–C11 bond during the initial cyclization (Ahuja et al., 2012).

Fig. 1.

A. Phylogenetic tree showing the relationships between the Group V PKSs in the aspergilli based on their PT domains. This is an excerpt of the tree described in the methods, chosen to include the Group V PKSs, with the orsellinic acid PKS, OrsA, as an outgroup. The tree shows that these PKSs fall into two main subgroups, Group V1 and V2 (Li et al., 2011), with EncA basal to both. The PKSs corresponding to clusters shown in Fig. 1B are in bold.

B. The trypacidin gene cluster and its homologous characterized Group V1 NR-PKS gene clusters in the aspergilli. The producing species are listed above each cluster and their respective products are displayed below. All but the endocrocin cluster also have homologues of the paired transcriptional regulators of the aflatoxin gene cluster, AflR/AflS, shown in white. PKS genes are shown in gray, genes conserved in all clusters shown with a gray outline, and all other genes in black. Shaded regions connect homologous genes, and non-contiguous segments are separated by slashes.

The set of genes surrounding tpcC also has significant identity to the monodictyphenone, endocrocin, and geodin biosynthetic clusters (Fig. 1B). Genetic characterization of the geodin-producing cluster from A. terreus (Nielsen et al., 2013) highlighted a high degree of similarity between these two clusters and their final products (Fig. 1B and Table S2). Given this similarity, we hypothesized that tpcC was the most likely candidate to initiate trypacidin synthesis in A. fumigatus. While initial in silico predictions of the trypacidin biosynthetic gene cluster spanned a 66 kb region with 31 genes (AFUA_4G14420 – AFUA_4G14730) (Khaldi et al., 2010; Medema et al., 2011; Inglis et al., 2013), homology with the geodin cluster suggests the tpc cluster consists of a 25 kb region with 13 genes: AFUA_4G14580 through AFUA_4G14460, which we term tpcA-M (Fig. 1B and Table S2).

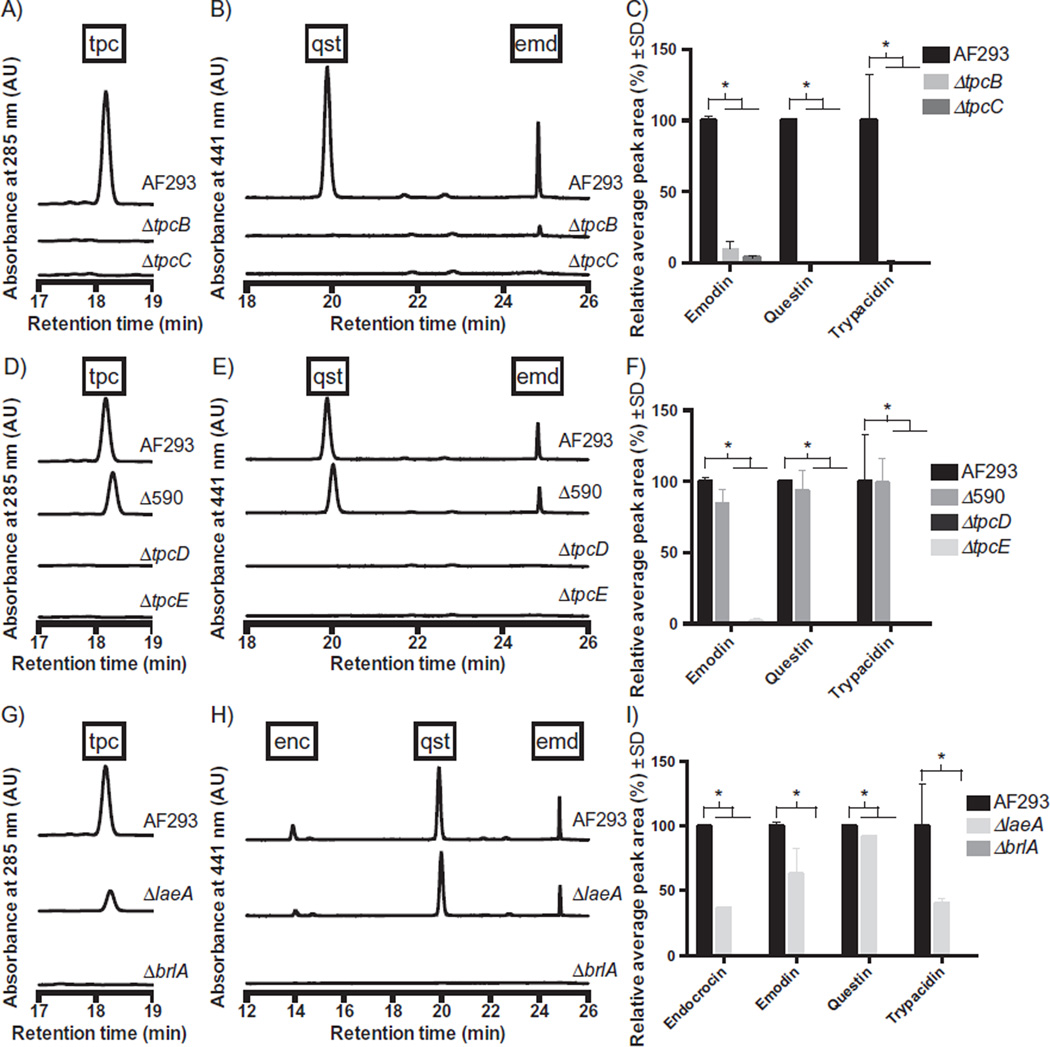

In order to confirm the assignment of these genes to trypacidin biosynthesis, we created deletion mutants of tpcC, encoding the NR-PKS, and tpcB, encoding the MβL-TE (Table S2 and Fig. S1). Deletion of either gene resulted in loss of trypacidin and pathway intermediates including questin as determined by comparison to purified standards (Fig. 2A–C; Figs S2 and 3). Additionally, we identified two Zn2Cys6 transcription factor-encoding genes in the region of the tpc cluster, namely, tpcE and AFUA_4G14590 (Table S2). Deletion of tpcE but not AFUA_4G14590 resulted in loss of trypacidin and questin (Fig. 2D–F; Fig. S4). TpcE is a homologue of AflR, the sterigmatocystin/aflatoxin Zn2Cys6 transcription factor (Woloshuk et al., 1994). The co-activator AflS (formerly called AflJ) is also required for sterigmatocystin/aflatoxin synthesis (Woloshuk et al., 1994; Ehrlich et al., 2012) and enhances AflR activity. An aflS homologue, tpcD, is located next to tpcE, and its deletion also resulted in loss of trypacidin (Fig. 2D–F, Fig. S4). We also confirmed regulation of the trypacidin and endocrocin clusters by LaeA and the conidiation-specific transcription factor BrlA (Mah and Yu, 2006) (Fig. 2G–I, Fig. S5) as reported or suggested by earlier studies (Perrin et al., 2007; Gauthier et al., 2012). Both production of metabolites and gene expression showed BrlA to more tightly regulate the clusters than LaeA.

Fig. 2.

Representative chromatograms from HPLC analysis of wild-type (AF293) and trypacidin cluster mutants (ΔtpcB and ΔtpcC, A–C; ΔtpcE, ΔtpcD, and ΔAFUA_4G14590 (Δ590), D–F; ΔlaeA and ΔbrlA, G–I) at 285 nm (A, D and G) and 441 nm (B, E and H). These data are trimmed to show only the relevant ranges of retention times for detection of trypacidin (tpc), its precursors questin and emodin (qst and emd, respectively), and endocrocin (enc). Quantification of duplicate analyses is presented in the bar graphs (C, F and I), and asterisks represent statistical significance of the indicated pairwise comparisons with α = 0.05.

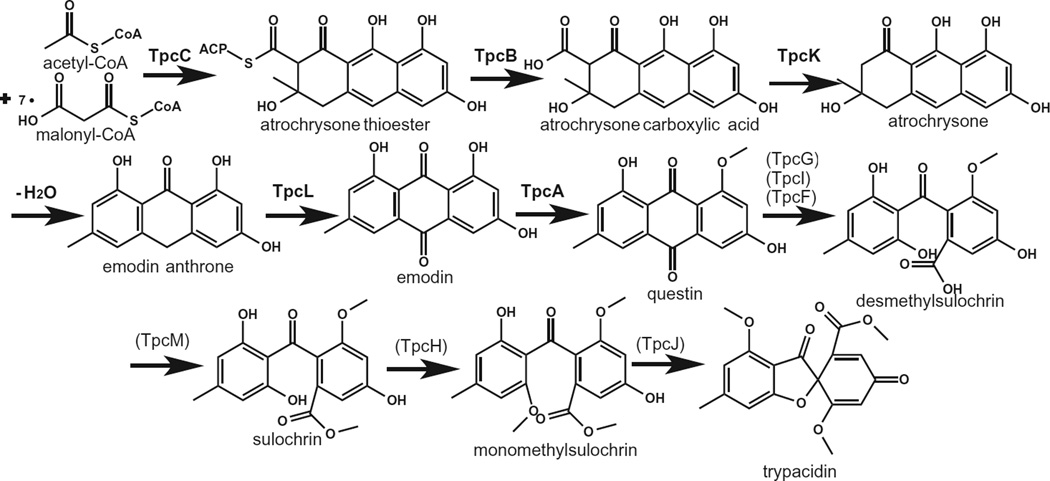

We present a likely biosynthetic pathway for trypacidin synthesis (Fig. 3) based on these data and proposed and characterized polyketide biosynthetic pathways, primarily geodin, aflatoxin, monodictyphenone and prenyl xanthones (Henry and Townsend, 2005a,b; Chiang et al., 2010; Sanchez et al., 2011; Simpson, 2012; Nielsen et al., 2013).

Fig. 3.

The proposed biosynthetic pathway of trypacidin. The protein putatively catalysing each step is indicated over the arrow, and the dehydration potentially occurs spontaneously. Genes-encoding enzymes in bold were deleted in this study, whereas the assignment of roles for enzymes that are in regular font and parentheses were made based on comparison to similar characterized biosynthetic pathways. The assignment of the methyltransferases TpcA, TpcH and TpcM was determined by analysis of a ΔtpcA strain (Fig. S3) and comparison to the proposed cluster and biosynthetic pathway for geodin (Nielsen et al., 2013). Note the conversion of questin to desmethylsulochrin, and similar reactions in monodictyphenone and aflatoxin biosynthesis, have multiple proposed mechanisms (Henry and Townsend, 2005a,b; Simpson, 2012).

Endocrocin produced by both the tpc and enc clusters through distinct routes

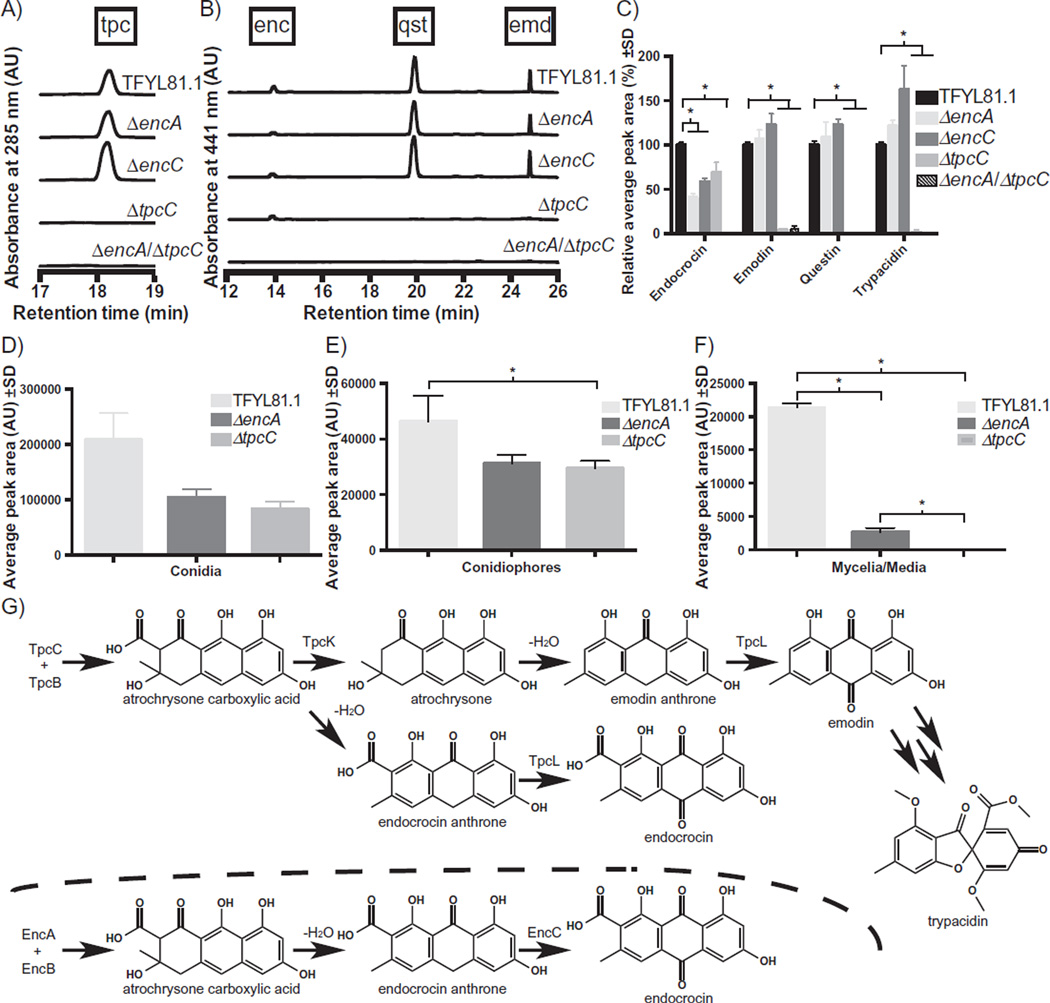

Because trypacidin and endocrocin are both regulated by LaeA and BrlA (Fig. 2G – I) and the PKSs involved in their syntheses belong to the same phylogenetic clade, Group V (Li et al., 2010), we thought it possible that their biosyntheses might have a unique interrelationship. Therefore, we assessed the AF293 strain, which produces both endocrocin and trypacidin, to determine if any such relationship existed. In contrast to the ΔencA mutation in the CEA10 background that displayed a complete loss of endocrocin (Lim et al., 2012), we found that the AF293 ΔencA mutant surprisingly still produced endocrocin, although at lower levels than wild type (WT; Fig. 4A – C). Extracts of the ΔtpcC strain also appeared to show a reduction, but not elimination, of endocrocin relative to the wild-type control (Fig. 4A – C). Previous work had characterized the enc cluster in strains derived from the A. fumigatus isolate CEA10 (Lim et al., 2012). However, this strain does not produce trypacidin or its intermediates, despite the presence of the tpc cluster (Fig. S6). Examination of the nucleotide sequence of the tpc cluster in CEA10 uncovered a single-nucleotide insertion in the fourth exon of tpcC. This is predicted to result in a frameshift and premature termination codon, which would explain the inability of this isolate to produce these metabolites (Table S3).

Fig. 4.

Representative chromatograms from HPLC analysis of WT (TFYL81.1), ΔencA, ΔencC, ΔtpcC, and ΔencA/ΔtpcC mutants at 285 nm (A) and 441 nm (B). These data are trimmed to show only the relevant ranges of retention times for detection of trypacidin (tpc), its precursors questin and emodin (qst and emd, respectively), and endocrocin (enc). Quantification of duplicate analyses is presented in the bar graph (C). Quantification of triplicate analyses of the tissue-specific production and localization of endocrocin (detected at 441 nm) to the conidia (D), conidiophores (E) and mycelia/media (F) assessed by HPLC analysis of WT (TFYL81.1), ΔencA, and ΔtpcC mutants. Asterisks (C–F) represent statistical significance of the indicated pairwise comparisons with α = 0.05. Comparison of the early steps of the predicted trypacidin and endocrocin biosynthetic pathways (D). The protein putatively catalysing each step is indicated over the arrow, and the dehydration potentially occurs spontaneously.

Given this, as well as the similarity of the genes encoding the initial enzyme activities of the two clusters (Lim et al., 2012), we hypothesized that the source of endocrocin in the AF293 ΔencA mutant might be the tpc cluster (Fig. 4G). We therefore created several ΔencA/ΔtpcC double deletion mutants and found that all of them exhibited a complete loss of endocrocin production (Fig. 4A – C). This observation confirms that the trypacidin biosynthetic cluster contributes to the production of endocrocin and indicates that, in wild-type AF293, endocrocin is derived from both the tpc and enc clusters. Conversely, it does not appear that the enc cluster contributes to the trypacidin pathway as demonstrated by complete loss of trypacidin and its precursors in tpc cluster deletants despite the presence of an intact enc cluster (Fig. 2A – F). This might suggest that the pathways are independent or perhaps compartmentalized within the cell.

Both trypacidin and endocrocin have been reported as spore metabolites. To more thoroughly assess tissue localization of endocrocin produced by either pathway, spore (Fig. 4D), conidiophore (containing fallen spores and some surface mycelium; Fig. 4E), and mycelia/agar (Fig. 4F) fractions were analysed for endocrocin in both the ΔencA mutant and ΔtpcC mutants. Supporting earlier studies, endocrocin was primarily localized to the spore fraction (Fig. 4D). Lesser amounts were found in conidiophore and mycelial fractions (Fig. 4E – F). Interestingly, a small amount of endocrocin was detectable in the mycelial fraction of the ΔencA mutant but not of the ΔtpcC mutant, suggesting more specific localization of the endocrocin produced by the enc cluster to the spore (Fig. 4F).

We asked whether the redundancy of endocrocin production could be attributed to utilization of an early intermediate common to both pathways by downstream enzymes in the endocrocin pathway. Specifically, we asked whether the monooxygenase EncC (the first decorating enzyme in the endocrocin biosynthetic pathway after release of the backbone from EncA by EncB; Fig. 4G) might use early pathway intermediates derived from either the enc or tpc clusters as a substrate to generate endocrocin. EncC possesses similarity to HypC, an anthrone oxidase involved in a similar conversion in aflatoxin biosynthesis (Ehrlich et al., 2010), and deletion of EncC results in loss of endocrocin in the CEA10 background (Lim et al., 2012). If EncC could utilize precursors from early steps in trypacidin synthesis, we hypothesized that deletion of encC would result in complete loss of endocrocin, much like the ΔencA/ΔtpcC mutants. However, endocrocin production in the AF293 ΔencC mutant was similar to that of the AF293 ΔencA mutant showing a reduction but not elimination of endocrocin (Fig. 4A – C). While these results cannot rule out the possibility of intermediate sharing between the two pathways, they are consistent with the hypothesis that endocrocin is produced as a shunt product of the trypacidin pathway.

The hypothetical endocrocin shunt would likely occur from the early steps in the trypacidin pathway. Previous work had shown that deletion of mdpH in A. nidulans resulted in accumulation of endocrocin (Chiang et al., 2010), and tpcK and tpcL are homologous to the 5′ and 3′ halves of mdpH respectively (Fig. 1B and Fig. 5A). TpcL also shows homology to the anthrone oxidases HypC and EncC, whereas TpcK is a putative decarboxylase, based on the prediction of the same activity for MdpH (Chiang et al., 2010). We therefore made single and double deletions of tpcK and tpcL to address if either of the encoding enzyme activities contributed to endocrocin production.

Fig. 5.

A diagram of the homologues of tpcK and tpcL in A. fumigatus, A. terreus and A. nidulans (A). Representative chromatograms from HPLC analysis of WT (TFYL81.1) and endocrocin and trypacidin cluster mutants (ΔencC, ΔtpcK, ΔtpcL, ΔtpcK/Δ tpcL, and ΔAFUA_4G09250 (Δ250), B–D; ΔencC, ΔtpcK/ΔencC, ΔtpcL/ΔencC, ΔtpcK/Δ tpcL/ ΔencC, and ΔAFUA_4G09250/ΔencC (Δ250/ΔencC), E–G) at 285 nm (B and E) and 441 nm (C and F). These data are trimmed to show only the relevant ranges of retention times for detection of trypacidin (tpc), its precursors questin and emodin (qst and emd, respectively), and endocrocin (enc). Quantification of duplicate analyses is presented in the bar graphs (D and G), and asterisks represent statistical significance of the indicated pairwise comparisons with α = 0.05.

Deletion of tpcK increased endocrocin production nearly 10-fold and exhibited concomitant loss of downstream trypacidin pathway metabolites, emodin and questin (Fig. 5B–D; Fig. S7). This observation is consistent with the proposed role of TpcK as a decarboxylase (Figs 2G and 4G) and similar to the result of mdpH deletion in A. nidulans. Deletion of tpcL resulted in modest decrease in the production of questin but an approximately twofold increase in endocrocin and emodin (Fig. 5B–D; Fig. S7). This suggests that the proposed enzymatic step for TpcL (Figs 2G and 4G) might be catalysed by other oxidases in the genome or may occur spontaneously. Double deletion of tpcK and tpcL resulted in a similar phenotype to the ΔtpcK mutant, suggesting that tpcK is upstream of tpcL in the trypacidin pathway. A third putative anthrone oxidase-encoding gene, AFUA_4G09250, was found in the A. fumigatus genome, however, its deletion had no effect on the levels of metabolites in the endocrocin or trypacidin pathways (Fig. 5B–D; Fig. S7).

We also examined the metabolic output of deletions of tpcK, tpcL, tpcK/L, or AFUA_4G09250 in a ΔencC background. These mutants yielded approximately half the amount of endocrocin relative to the amount produced by their respective single deletants in a wild-type encC background, but no other significant changes (Fig. 5E – G). Thus, it appears that endocrocin production from the trypacidin pathway results from incomplete conversion of atrochrysone carboxylic acid to downstream products, specifically by TpcK. Taken together, these results strongly support independent mechanisms leading to endocrocin biosynthesis by the tpc and enc clusters where one cluster yields endocrocin as a shunt metabolite (tpc) and one as an end metabolite (enc) (Fig. 4G).

Contribution of tpc and enc clusters to virulence in Toll-deficient Drosophila melanogaster

An earlier study had shown that encA deletion resulted in a less virulent strain using the Toll-deficient Drosophila model of IA (Lionakis et al., 2005; Berthier et al., 2013). We again used this model to compare the pathogenicity of both single ΔencA and ΔtpcC deletion mutants and the double deletant to wild type (Fig. S8). The results show that the ΔencA mutant has significantly decreased virulence in two of three trials, while the ΔtpcC mutant has no consistent effect. The ΔencA/ΔtpcC mutant is also significantly impaired in virulence in two of the three trials.

Discussion

The tpc cluster constitutes the fifth described example of a LaeA- and BrlA-regulated spore SM cluster alongside DHN melanin, fumigaclavines, endocrocin, and the fumiquinazolines (Coyle et al., 2007; Perrin et al., 2007; Twumasi-Boateng et al., 2009; Lim et al., 2012; 2014; Upadhyay et al., 2013). Although trypacidin was initially reported to be isolated from the mycelium (Turner, 1965), it was later found to localize to the conidia (Parker and Jenner, 1968; Gauthier et al., 2012), a finding supported by our work. In an unexpected twist, we find that both the tpc and enc clusters contribute to the synthesis of endocrocin. To our knowledge, only two prior studies have described two physically discrete clusters contributing to the synthesis of the same metabolite in one fungal species (Forseth et al., 2013; Guo et al., 2015). This finding is in contrast to the recently discovered phenomenon of superclusters, in which a single co-regulated cluster can produce two distinct metabolites (e.g. fumagillin and pseurotin) (Wiemann et al., 2013), and thus expands our concept of SM plasticity in filamentous fungi.

The tpc and enc clusters, along with the ged and mdp clusters, contain a TE-less NR-PKS coupled with a MβL-TE, characteristic of this phylogenetic clade of PKSs (Fig. 1A). In three of these four clusters, these genes are present as a divergently oriented pair (Fig. 1B). In addition to maintaining this gene pair, the early biosynthetic steps proposed for all four metabolites are very similar, consisting of the PKS-MβL step followed by anthrone oxidase activity (Figs 2G and 4G) (Chiang et al., 2010; Lim et al., 2012; Nielsen et al., 2013). Interestingly, in vitro expression of the geodin PKS-encoding gene, gedC (formerly called ACAS), and MβL-TE-encoding gene, gedB (formerly called ACTE), yielded endocrocin, emodin, and their precursors (Awakawa et al., 2009). Also, as mentioned, deletion of mdpH of the monodictyphenone cluster resulted in accumulation of endocrocin (Chiang et al., 2010). Coupling these data with our finding that the tpc cluster can produce endocrocin, likely because of incomplete TpcK activity, we suggest that endocrocin production may be generated as a shunt product from NR-PKS/ MβL-TE clusters containing TpcK and TpcL homologues or produced directly by those clusters containing a TpcL (but not TpcK) homologue. The anthrone oxidase and decarboxylase activities are keys in endocrocin metabolism, either directing to (TpcL/EncC) or diverting from (TpcK/MdpH) its synthesis.

Previous studies (Awakawa et al., 2009) suggest that the NR-PKS/MβL-TE pairing alone could produce some amount of endocrocin which may be oxidized non-enzymatically from an anthrone precursor (Fig. 4G). Deletion of the anthrone oxidase HypC in Aspergillus parasiticus revealed a similar situation where conversion of norsolorinic acid anthrone to norsolorinic acid also occurred non-enzymatically (Ehrlich et al., 2010). Deletion of tpcL in our study still allowed for emodin accumulation, presumably through processing of emodin anthrone either non-enzymatically or by another oxidase encoded in the genome. Interestingly, endocrocin production is reported not only from numerous fungi (Kurobane et al., 1979; Räisänen et al., 2000; Yang et al., 2013), but also insects (Kikuchi et al., 2011) and plants (Jan et al., 2015) which may reflect yet other biosynthetic pathways leading to endocrocin.

From where might the additional genes in the more complex NR-PKS/MβL-TE clusters derive? The tpc cluster was referenced in a 2007 study of the evolution of the aflatoxin gene cluster (Carbone et al., 2007). Aflatoxin is a polyketide generated from a large NR-PKS cluster containing several genes with significant similarity to tpc cluster genes, in addition to the already noted hypC, which was not yet discovered in 2007. In this paper, the authors identify modules, consisting primarily of highly correlated gene pairs that they propose are duplicated and evolved in secondary metabolite gene clusters.At the time, five genes in what we now know as the tpc cluster were speculated as having arisen from a hypothetical cluster ancestral to the aflatoxin cluster. These were tpcD/E, which are homologous to aflR/S; tpcG/I, which are homologous to aflX/Y; and tpcC, homologous to aflC. Expansion of an ancestral enc-like cluster can be envisioned by ‘capture’ of such modules. It is possible that the current enc and tpc clusters both arose from a small ancestral cluster in A. fumigatus. Alternatively, the enc cluster, comprising fewer genes than the tpc cluster, may have arisen from loss of modules from an ancestral tpc-like cluster.

Though previous predictions of the trypacidin cluster range from AFUA_4G14420-AFUA_4G14730 (Khaldi et al., 2010; Medema et al., 2011; Inglis et al., 2013), the cluster is nearly identical to the geodin-producing cluster in A. terreus (Nielsen et al., 2013). Twelve of the 13 genes in these clusters are homologous, with only the methyltransferase-encoding tpcH and halogenase-encoding gedL unique to each cluster. These two activities are reflected in the chemical structures of their respective end metabolites (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, these unique genes are on either side of a five-gene inversion, suggesting a possible mechanism for introduction and maintenance of variation in an ancestral SM-producing gene cluster. Variations of fungal SM clusters resulting from inversions and deletions are common and contribute to the production of biosynthetically related but different end metabolites, e.g. the aflatoxin and sterigmatocystin gene clusters of A. flavus and A. nidulans (Hodges et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2006; Carbone et al., 2007) and the sirodesmin and gliotoxin clusters of Leptosphaeria maculans and A. fumigatus (Gardiner et al., 2004; Fox and Howlett, 2008).

The enc and tpc clusters are both regulated by LaeA and BrlA, while the tpc cluster is further regulated by the TpcD/E pair. The acquisition or maintenance of tpcD/E might allow for more dynamic production of trypacidin and its intermediates, many of which are bioactive (Fujimoto et al., 1999; Ohashi et al., 1999; Choi et al., 2007; Shrimali et al., 2013). The presence of cluster-specific transcription factors potentiates a more nuanced activation of the cluster perhaps to time the production of the metabolites. As suggested for aflatoxin biosynthesis (Meyers et al., 1998; Du et al., 2007; Roze et al., 2007), and consistent with observations of the geodin cluster (Nielsen et al., 2013), the AflR/S homologues may enable the uncoupling of early and late phases of the biosynthetic pathway. In total, the coordinated timing of this and the conidiation-specific level of regulation, involving BrlA, may facilitate the specific accumulation of the end metabolite, trypacidin, into the spore.

For this study, we utilized A. fumigatus strain AF293, which produces trypacidin and endocrocin, however, the previous study characterizing the enc cluster used CEA10-derived strains, which do not produce trypacidin. There are other examples of differential production of a metabolite between strains of a given species, including A. fumigatus (Frisvad et al., 2009). In some cases, genetic defects responsible for this differential metabolite production have been described in the cluster. For example, in AF293, a point mutation in ftmD prevents the strain from producing fumitremorgins in contrast to CEA10 and A. fumigatus strain BM939 (Kato et al., 2013). Further examples have been suggested in Aspergillus niger (Andersen et al., 2011), and such defects are thought to have resulted in the loss of aflatoxin production in some Aspergillus oryzae strains (Lee et al., 2006; Kiyota et al., 2011).

In summary, the newly described trypacidin cluster and the endocrocin cluster both produce endocrocin through distinct routes in A. fumigatus. The trypacidin and endocrocin clusters are both regulated by LaeA and BrlA, and their end metabolites are localized to the asexual spores. Relatively little is known about the biological significance of endocrocin and trypacidin synthesis, but we speculate that they may have a role in protection of the spore from abiotic stressors. Endocrocin and precursors of trypacidin (e.g. questin and emodin) are pigmented anthraquinones. Anthraquinones have been shown to provide protection from UV radiation to the producing organism (Nybakken et al., 2004) and may contribute to protection to A. fumigatus as well. Other than the trypanocidal activity of trypacidin (Balan et al., 1963), additional studies are required to confirm any biological function of these metabolites and the redundancy in endocrocin production for the fungus.

Experimental procedures

Fungal strains and growth conditions

All strains used in this study are listed in Table S4. Mutants were derived from pyrG1 or argB1/pyrG1 auxotrophic backgrounds of Aspergillus fumigatus strain AF293 (Osherov et al., 2001; Xue et al., 2004). Stocks of each strain were stored in 30% (v/v) glycerol in 0.01% (v/v) TWEEN-80 at −80°C. Strains were activated and grown on solid glucose minimal medium (GMM) (Shimizu and Keller, 2001) with appropriate supplements at 37°C for 3 days for spore collection. For pyrG1 auxotrophs, 5.2 mM uridine and 5 mM uracil were added as supplements, and for argB1 auxotrophs, 5.7 mM L-arginine was added as a supplement. Spores were collected in 0.01% (v/v) TWEEN-80 and enumerated using a hemacytometer. For isolation of genomic DNA for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Southern blot, 10 ml of liquid minimal medium (Shimizu and Keller, 2001) with yeast extract was inoculated with spores from solid medium and grown overnight at 37°C. For assessment of metabolite production, 5 µL of a suspension of 2 × 106 spores ml−1 of each strain were point inoculated on solid GMM and grown at 29°C for 120 h without light selection. For tissue-specific metabolite analysis, this time was increased to 192 h. The conidial fraction of the culture was collected by tapping the plate with a spatula with the lid down, the conidiophore/surface mycelial fraction (also containing residual spores) was collected by scraping into 5 ml 0.01% (v/v) TWEEN-80, and the mycelial fraction was collected by taking three 1.5 cm diameter cores after rinsing the plate with ddH2O.

Construction of mutants

The mutants used in this study were created using the double-joint PCR method (Szewczyk et al., 2006). Genomic DNA was isolated as previously described (Shimizu and Keller, 2001). Generation of protoplasts and transformation were performed as previously described (Szewczyk et al., 2006). Primers (Table S5) were designed to amplify 800– 1000 bp flanks with 20 bp of overlap with the selection cassette-containing plasmid (Table S6) with dnastar’s Lasergene12 suite (DNASTAR; Madison, WI) and Primer3 (Koressaar and Remm, 2007; Untergasser et al., 2012). For deletion strains, the plasmid used was pJW24 (Calvo et al., 2004), encoding the A. parasiticus pyrG gene, or pJMP4 (Sekonyela et al., 2013), encoding the A. fumigatus argB gene. The A. fumigatus akuA gene was deleted in AF293.6 (Xue et al., 2004) using A. parasiticus pyrG amplified from pJW24 (Calvo et al., 2004) to produce TFYL43.2. To generate TFYL44.1, A. parasiticus pyrG was removed from the akuA locus by transforming strain TFYL43.2 with single-joint PCR product containing 0.5–1 kb genomic DNA fragments flanking the pyrG sequence. TFYL45.1 was generated from TFYL43.2 by replacing the A. parasiticus pyrG at the akuA locus with firefly luciferase constitutively expressed by the A. nidulans gpdA promoter amplified from pJMP147 (J. Palmer and N. Keller, unpubl.). For both TFYL44.1 and TFYL45.1, transformants were plated onto sorbitol minimal media supplemented with the above-mentioned concentrations of uridine, uracil, arginine and sub-inhibitory concentration (0.75 mg ml−1) of 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA). Both encA and encC were deleted in strain TFYL45.1 using A. parasiticus pyrG amplified from pJW24 to generate strains TFYL68.1 and TFYL69.1 respectively. tpcC was deleted in strain TFYL45.1 using A. fumigatus argB amplified from pJMP4 to generate strain TFYL71.1. To generate the double encA and tpcC deletion mutant (TFYL72.1), tpcC was deleted from strain TFYL68.1 using A. fumigatus argB amplified from pJMP4 (Sekonyela et al., 2013). Both TFYL68.1 and TFYL69.1, arginine auxotrophs, were transformed with pJMP4 to generate the prototrophs TFYL73.1 and TFYL74.1, respectively, while TFYL71.1, a uridine and uracil auxotroph, was transformed with pKJA12.1 (K. Affeldt and N. Keller, unpubl.) to generate the prototroph TFYL76.1. Transformants were screened for proper integration of the construct first by PCR, then by Southern blot (Fig. S1). For all auxotrophic mutants, maintenance of the mutant allele(s) was confirmed via PCR after complementation to prototrophy. The wild-type control used for all strains created in the ΔakuA background, TFYL81.1, was created from TFYL43.2 by complementation to prototrophy with A. fumigatus argB. This strain was comparable to AF293 in production of the metabolites assessed in this study.

Comparative genomic analysis

Sequence information and genome annotation were derived from the Aspergillus Genome Database aspgd.org (Cerqueira et al., 2014). Comparison of orthologous genes in various fungal species was carried out using the sybil browser hosted at AspGD. The National Center for Biotechnology Information’s blast (Altschul et al., 1990) was used to manually supplement the annotations of AspGD and the predictions made by the sybil browser. dnastar’s lasergene12 suite (including SeqBuilder, SeqMan Pro and EditSeq) was used for sequence analysis (DNASTAR, Madison, WI). For phylogenetic tree construction Clustal Omega (Sievers et al., 2011) was used to align a large set of NR-PKSs (Table S1), and UGene was used to extract the PT domain based on the canonical PT domain from the A. parasiticus PksA. These PT domains were then realigned and used as the basis for the phylogenetic tree with Clustal Omega and FigTree (Rambaut, 2007).

SM extraction and chromatography

For tissue-specific metabolite extraction from the conidial fraction (see above), the spores were collected in 6 ml of 50:50 ethyl acetate : methanol, the conidiophore fraction was extracted with an equal volume (5 ml) of ethyl acetate. The mycelial fraction and all other samples were processed as follows: A 1.5 cm core was taken from each plate grown as described above, and homogenized in 2.5 ml of double-distilled water (ddH2O) in a glass extraction vial with a Kinematica homogenizer. To each vial, 2.5 ml of ethyl acetate was added, vortexed and allowed to steep overnight. The vials were then centrifuged at 1100 g for 3 min and 1.9 ml of the organic layer was transferred to a new vial. This extract was allowed to evaporate at room temperature. For thin-layer chromatography (TLC), the extracts were dissolved in 50 µL ethyl acetate and 10 µL was spotted to a 250 µm silica gel plate (Whatman, Cat#15–4410-222), which was then placed in a mobile phase of toluene, ethyl acetate and formic acid in a 50:40:7 volume ratio. The plate was then imaged at 366 and 254 nm using a FOTO/Analyst Investigator gel imaging system (Fotodyne). For high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis, the extracts were re-suspended in 50% (v/v) acetonitrile in ddH2O and filtered using a 0.2 µm syringe filter. The samples were analysed using a Perkin Elmer Flexar Instrument as previously described (Lim et al., 2014), but with 1% (v/v) formic acid in solvents A (ddH2O) and B (acetonitrile), a 1.5 ml min−1 flow rate, and using the following modified program: equilibration in 20% B for 10 min before each sample injection, 20% B for 2 min, ramp to 50% B over 20 min, ramp to 100% B over 1 min, hold at 100% B for 5 min. Strains were analysed in duplicate, the peak areas for each compound averaged and calculated as a proportion of their respective wild-type controls, either AF293 or TFYL81.1 (Table S4). TFYL81.1 was comparable to AF293 in production of the metabolites assessed in this study. Statistical significance of pairwise comparisons between the metabolite profiles of different strains was assessed by multiple t-tests with a threshold of 0.05 and the Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons in Prism (GraphPad Software). Trypacidin standard was obtained from Dr. Olivier Puel (UMR1331 ToxAlim, French National Institute for Agricultural Research, INP, UPS, Toulouse, France), and endocrocin, emodin and questin standards from Dr. Clay Wang (USC School of Pharmacy, 1985 Zonal Avenue, Los Angeles, California, U.S.A.) (Fig. S2).

Drosophila assays

Flies were generated by crossing a Drosophila melanogaster line carrying a thermosensitive allele of Toll (Tl r632) with a line carrying a null allele of Toll (Tl I-RXA) (Lionakis et al., 2005). Five to seven-day-old adult female Toll-deficient flies were used for all experiments. Twenty to thirty-two flies were infected with each A. fumigatus strain. A. fumigatus isolates were grown on yeast extract agar glucose at 25°C. Conidia were collected from 2-day-old cultures in sterile 0.9% (w/v) saline, enumerated using a hemacytometer and adjusted to a concentration of 5 × 107 conidia ml−1. The dorsal thorax of CO2 anaesthetized flies was punctured using a sterile 10 µm needle dipped in this conidial suspension. As a negative control, flies were punctured with a needle that was not dipped in conidial suspension. Flies were monitored daily for survival over 7 days. Death within 3 h was considered a result of the injection procedure, and these flies were not included in subsequent analysis. The flies were housed in a 29°C incubator to maximize expression of the Tl r632 phenotype (Lionakis et al., 2005). The Toll-deficient flies were transferred into fresh vials every 3 days. Each experiment was repeated three times on different days at a consistent time of day to eliminate variability due to circadian rhythm.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Clay Wang for endocrocin, emodin and questin standards, and Dr. Olivier Puel for the trypacidin standard. We would like thank Nathaniel Albert for carrying out the Drosophila assays, and Dr. Philipp Wiemann for general consultation and proofreading. We would also like to thank our funding sources: grants from the American Asthma Foundation (11-0137), the USDA Hatch Formula Fund (WIS01710), and the NIH (R01 AI065728) to N.P.K. and the University of Wisconsin-Madison Genetics Department (5T32GM07133).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahuja M, Chiang YM, Chang SL, Praseuth MB, Entwistle R, Sanchez JF, et al. Illuminating the diversity of aromatic polyketide synthases in Aspergillus nidulans. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8212–8221. doi: 10.1021/ja3016395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allam NG, Abd El-Zaher EHF. Protective role of Aspergillus fumigatus melanin against ultraviolet (UV) irradiation and Bjerkandera adusta melanin as a candidate vaccine against systemic candidiasis. Afr J Biotech. 2012;11:6566–6577. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amitani R, Taylor G, Elezis EN, Llewellyn-Jones C, Mitchell J, Kuze F, et al. Purification and characterization of factors produced by Aspergillus fumigatus which affect human ciliated respiratory epithelium. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3266–3271. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3266-3271.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen MR, Salazar MP, Schaap PJ, van de Vondervoort PJ, Culley D, Thykaer J, et al. Comparative genomics of citric-acid-producing Aspergillus nigerATCC 1015 versus enzyme-producing CBS 513.88. Genome Res. 2011;21:885–897. doi: 10.1101/gr.112169.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awakawa T, Yokota K, Funa N, Doi F, Mori N, Watanabe H, Horinouchi S. Physically discrete beta-lactamase-type thioesterase catalyzes product release in atrochrysone synthesis by iterative type I polyketide synthase. Chem Biol. 2009;16:613–623. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balan J, Ebringer L, Nemec P, Kovac S, Dobias J. Antiprotozoal Antibiotics. II. Isolation and characterization of trypacidin, a new antibiotic, active against Trypanosoma cruzi and Toxoplasma gondii . J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1963;16:157–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayry J, Beaussart A, Dufrêne YF, Sharma M, Bansal K, Kniemeyer O, et al. Surface structure characterization of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia mutated in the melanin synthesis pathway and their human cellular immune response. Infect Immun. 2014;82:3141–3153. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01726-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthier E, Lim FY, Deng Q, Guo CJ, Kontoyiannis DP, Wang CC, et al. Low-volume toolbox for the discovery of immunosuppressive fungal secondary metabolites. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003289. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok JW, Balajee SA, Marr KA, Andes D, Nielsen KF, Frisvad JC, Keller NP. LaeA, a regulator of morphogenetic fungal virulence factors. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:1574–1582. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.9.1574-1582.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok JW, Chung D, Balajee SA, Marr KA, Andes D, Nielsen KF, et al. GliZ, a transcriptional regulator of gliotoxin biosynthesis, contributes to Aspergillus fumigatus virulence. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6761–6768. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00780-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakhage AA. Systemic fungal infections caused by Aspergillus species: epidemiology, infection process and virulence determinants. Curr Drug Targets. 2005;6:875–886. doi: 10.2174/138945005774912717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo AM, Bok J, Brooks W, Keller NP. veA is required for toxin and sclerotial production in Aspergillus parasiticus . Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:4733–4739. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.8.4733-4739.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carberry S, Molloy E, Hammel S, O’Keeffe G, Jones GW, Kavanagh K, Doyle S. Gliotoxin effects on fungal growth: Mechanisms and exploitation. Fungal Genet Biol. 2012;49:302–312. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone I, Ramirez-Prado JH, Jakobek JL, Horn BW. Gene duplication, modularity and adaptation in the evolution of the aflatoxin gene cluster. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:111. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerqueira GC, Arnaud MB, Inglis DO, Skrzypek MS, Binkley G, Simison M, et al. The Aspergillus Genome Database: Multispecies curation and incorporation of RNA-Seq data to improve structural gene annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D705–D710. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang YM, Szewczyk E, Davidson AD, Entwistle R, Keller NP, Wang CC, Oakley BR. Characterization of the Aspergillus nidulans monodictyphenone gene cluster. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:2067–2074. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02187-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SG, Kim J, Sung ND, Son KH, Cheon HG, Kim KR, Kwon BM. Anthraquinones, Cdc25B phosphatase inhibitors, isolated from the roots of Polygonum multiflorum Thunb. Nat Prod Res. 2007;21:487–493. doi: 10.1080/14786410601012265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chooi YH, Tang Y. Navigating the fungal polyketide chemical space: from genes to molecules. J Org Chem. 2012;77:9933–9953. doi: 10.1021/jo301592k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chooi YH, Fang J, Liu H, Filler SG, Wang P, Tang Y. Genome mining of a prenylated and immunosuppressive polyketide from pathogenic fungi. Org Lett. 2013;15:780–783. doi: 10.1021/ol303435y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle CM, Kenaley SC, Rittenour WR, Panaccione DG. Association of ergot alkaloids with conidiation in Aspergillus fumigatus . Mycologia. 2007;99:804–811. doi: 10.3852/mycologia.99.6.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford JM, Korman TP, Labonte JW, Vagstad AL, Hill EA, Kamari-Bidkorpeh O, et al. Structural basis for biosynthetic programming of fungal aromatic polyketide cyclization. Nature. 2009;461:1139–1143. doi: 10.1038/nature08475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagenais TR, Keller NP. Pathogenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus in invasive Aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:447–465. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00055-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W, Obrian GR, Payne GA. Function and regulation of aflJ in the accumulation of aflatoxin early pathway intermediate in Aspergillus flavus . Food Addit Contam. 2007;24:1043–1050. doi: 10.1080/02652030701513826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich KC, Li P, Scharfenstein L, Chang PK. HypC, the anthrone oxidase involved in aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:3374–3377. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02495-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich KC, Mack BM, Wei Q, Li P, Roze LV, Dazzo F, et al. Association with AflR in endosomes reveals new functions for AflJ in aflatoxin biosynthesis. Toxins (Basel) 2012;4:1582–1600. doi: 10.3390/toxins4121582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forseth RR, Amaike S, Schwenk D, Affeldt KJ, Hoffmeister D, Schroeder FC, Keller NP. Homologous NRPS-like gene clusters mediate redundant small-molecule biosynthesis in Aspergillus flavus . Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:1590–1594. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox EM, Howlett BJ. Biosynthetic gene clusters for epipolythiodioxopiperazines in filamentous fungi. Mycol Res. 2008;112:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesen TL, Faris JD, Solomon PS, Oliver RP. Host-specific toxins: Effectors of necrotrophic pathogenicity. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:1421–1428. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisvad JC, Rank C, Nielsen KF, Larsen TO. Metabolomics of Aspergillus fumigatus. Med Mycol. 2009;47(Suppl. 1):S53–S71. doi: 10.1080/13693780802307720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto H, Fujimaki T, Okuyama E, Yamazaki M. Immunomodulatory constituents from an ascomycete, Microascus tardifaciens . Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1999;47:1426–1432. doi: 10.1248/cpb.47.1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner DM, Cozijnsen AJ, Wilson LM, Pedras MS, Howlett BJ. The sirodesmin biosynthetic gene cluster of the plant pathogenic fungus Leptosphaeria maculans . Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:1307–1318. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier T, Wang X, Sifuentes Dos Santos J, Fysikopoulos A, Tadrist S, Canlet C, et al. Trypacidin, a spore-borne toxin from Aspergillus fumigatus, is cytotoxic to lung cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e29906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C, Sun W, Bruno KS, Oakley BR, Keller NP, Wang C. Spatial regulation of a common precursor from two distinct genes generates metabolite diversity. Chem Sci. 2015 doi: 10.1039/c5sc01058f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry KM, Townsend CA. Synthesis and fate of o-carboxybenzophenones in the biosynthesis of aflatoxin. J Am Chem Soc. 2005a;127:3300–3309. doi: 10.1021/ja045520z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry KM, Townsend CA. Ordering the reductive and cytochrome P450 oxidative steps in demethylsterigmatocystin formation yields general insights into the biosynthesis of aflatoxin and related fungal metabolites. J Am Chem Soc. 2005b;127:3724–3733. doi: 10.1021/ja0455188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillmann F, Novohradská S, Mattern DJ, Forberger T, Heinekamp T, Westermann M, et al. Virulence determinants of the human pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus protect against soil amoeba predation. Environ Microbiol. 2015 doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges RL, Kelkar HS, Xuei X, Skatrud PL, Keller NP, Adams TH, et al. Characterization of an echinocandin B-producing strain blocked for sterigmatocystin biosynthesis reveals a translocation in the stcW gene of the aflatoxin biosynthetic pathway. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;25:333–341. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.7000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglis DO, Binkley J, Skrzypek MS, Arnaud MB, Cerqueira GC, Shah P, et al. Comprehensive annotation of secondary metabolite biosynthetic genes and gene clusters of Aspergillus nidulans, A. fumigatus, A. niger and A. oryzae . BMC Microbiol. 2013;13:91. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn B, Koch A, Schmidt A, Wanner G, Gehringer H, Bhakdi S, Brakhage AA. Isolation and characterization of a pigmentless-conidium mutant of Aspergillus fumigatus with altered conidial surface and reduced virulence. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5110–5117. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5110-5117.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan S, Kamili AN, Parray JA, Bedi YS. Differential response of terpenes and anthraquinones derivatives in Rumex dentatus and Lavandula officinalis to harsh winters across north-western Himalaya. Nat Prod Res. 2015 doi: 10.1080/14786419.2015.1030404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang D, Son GH, Park HM, Kim J, Choi JN, Kim HY, et al. Culture condition-dependent metabolite profiling of Aspergillus fumigatus with antifungal activity. Fungal Biol. 2013;117:211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato N, Suzuki H, Okumura H, Takahashi S, Osada H. Apoint mutation in ftmD blocks the fumitremorgin biosynthetic pathway in Aspergillus fumigatus strain Af293. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2013;77:1061–1067. doi: 10.1271/bbb.130026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaldi N, Seifuddin FT, Turner G, Haft D, Nierman WC, Wolfe KH, Fedorova ND. SMURF: genomic mapping of fungal secondary metabolite clusters. Fungal Genet Biol. 2010;47:736–741. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi N, Teshiba M, Tsutsumi T, Fudou R, Nagasawa H, Sakuda S. Endocrocin and its derivatives from the Japanese mealybug Planococcus kraunhiae . Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2011;75:764–767. doi: 10.1271/bbb.100742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistler HC, Broz K. Cellular compartmentalization of secondary metabolism. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:68. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyota T, Hamada R, Sakamoto K, Iwashita K, Yamada O, Mikami S. Aflatoxin non-productivity of Aspergillus oryzae caused by loss of function in the aflJ gene product. J Biosci Bioeng. 2011;111:512–517. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koressaar T, Remm M. Enhancements and modifications of primer design program Primer3. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1289–1291. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurobane I, Vining LC, McInnes AG. Biosynthetic relationships among the secalonic acids. Isolation of emodin, endocrocin and secalonic acids from Pyrenochaeta terrestris and Aspergillus aculeatus . J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1979;32:1256–1266. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.32.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon-Chung KJ, Sugui JA. What do we know about the role of gliotoxin in the pathobiology of Aspergillus fumigatus? Med Mycol. 2009;47(Suppl. 1):S97–S103. doi: 10.1080/13693780802056012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YH, Tominaga M, Hayashi R, Sakamoto K, Yamada O, Akita O. Aspergillus oryzae strains with a large deletion of the aflatoxin biosynthetic homologous gene cluster differentiated by chromosomal breakage. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;72:339–345. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0282-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Image II, Xu W, Image I, Tang Y. Classification, prediction, and verification of the regioselectivity of fungal polyketide synthase product template domains. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22764–22773. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.128504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Chooi YH, Sheng Y, Valentine JS, Tang Y. Comparative characterization of fungal anthracenone and naphthacenedione biosynthetic pathways reveals an α-hydroxylation-dependent Claisen-like cyclization catalyzed by a dimanganese thioesterase. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:15773–15785. doi: 10.1021/ja206906d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim FY, Keller NP. Spatial and temporal control of fungal natural product synthesis. Nat Prod Rep. 2014;31:1277–1286. doi: 10.1039/c4np00083h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim FY, Hou Y, Chen Y, Oh JH, Lee I, Bugni TS, Keller NP. Genome-based cluster deletion reveals an endocrocin biosynthetic pathway in Aspergillus fumigatus . Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:4117–4125. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07710-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim FY, Ames B, Walsh CT, Keller NP. Co-ordination between BrlA regulation and secretion of the oxidoreductase FmqD directs selective accumulation of fumiquinazoline C to conidial tissues in Aspergillus fumigatus . Cell Microbiol. 2014;16:1267–1283. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionakis MS, Lewis RE, May GS, Wiederhold NP, Albert ND, Halder G, Kontoyiannis DP. Toll-deficient Drosophila flies as a fast, high-throughput model for the study of antifungal drug efficacy against invasive aspergillosis and Aspergillus virulence. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1188–1195. doi: 10.1086/428587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodeiro S, Xiong Q, Wilson WK, Ivanova Y, Smith ML, May GS, Matsuda SP. Protostadienol biosynthesis and metabolism in the pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus . Org Lett. 2009;11:1241–1244. doi: 10.1021/ol802696a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah JH, Yu JH. Upstream and downstream regulation of asexual development in Aspergillus fumigatus . Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:1585–1595. doi: 10.1128/EC.00192-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschmeyer G, Haas A, Cornely OA. Invasive aspergillosis: epidemiology, diagnosis and management in immunocompromised patients. Drugs. 2007;67:1567–1601. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200767110-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medema MH, Blin K, Cimermancic P, de Jager V, Zakrzewski P, Fischbach MA, et al. antiSMASH: rapid identification, annotation and analysis of secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters in bacterial and fungal genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W339–W346. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers DM, Obrian G, Du WL, Bhatnagar D, Payne GA. Characterization of aflJ, a gene required for conversion of pathway intermediates to aflatoxin. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3713–3717. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3713-3717.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen MT, Nielsen JB, Anyaogu DC, Holm DK, Nielsen KF, Larsen TO, Mortensen UH. Heterologous reconstitution of the intact geodin gene cluster in Aspergillus nidulans through a simple and versatile PCR based approach. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e72871. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nybakken L, Solhaug KA, Bilger W, Gauslaa Y. The lichens Xanthoria elegans and Cetraria islandica maintain a high protection against UV-B radiation in Arctic habitats. Oecologia. 2004;140:211–216. doi: 10.1007/s00442-004-1583-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi H, Ueno A, Nakao T, Ito J, Kimura K, Ishikawa M, et al. Effects of ortho-substituent groups of sulochrin on inhibitory activity to eosinophil degranulation. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9:1945–1948. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00305-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osherov N, Kontoyiannis DP, Romans A, May GS. Resistance to itraconazole in Aspergillus nidulans and Aspergillus fumigatus is conferred by extra copies of the A. nidulans P-450 14alpha-demethylase gene, pdmA . J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;48:75–81. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker GF, Jenner PC. Distribution of trypacidin in cultures of Aspergillus fumigatus . Appl Microbiol. 1968;16:1251–1252. doi: 10.1128/am.16.8.1251-1252.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin RM, Fedorova ND, Bok JW, Cramer RA, Wortman JR, Kim HS, et al. Transcriptional regulation of chemical diversity in Aspergillus fumigatus by LaeA. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e50. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A. FigTree. 2007 [WWW document]. URL http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/

- Räisänen R, Björk H, Hynninen PH. Two-dimensional TLC separation and mass spectrometric identification of anthraquinones isolated from the fungus Dermocybe sanguinea . Z Naturforsch [C] 2000;55:195–202. doi: 10.1515/znc-2000-3-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlfs M, Churchill AC. Fungal secondary metabolites as modulators of interactions with insects and other arthropods. Fungal Genet Biol. 2011;48:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roze LV, Arthur AE, Hong SY, Chanda A, Linz JE. The initiation and pattern of spread of histone H4 acetylation parallel the order of transcriptional activation of genes in the aflatoxin cluster. Mol Microbiol. 2007;66:713–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez JF, Entwistle R, Hung JH, Yaegashi J, Jain S, Chiang YM, et al. Genome-based deletion analysis reveals the prenyl xanthone biosynthesis pathway in Aspergillus nidulans . J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:4010–4017. doi: 10.1021/ja1096682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherlach K, Graupner K, Hertweck C. Molecular bacteria-fungi interactions: effects on environment, food, and medicine. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2013;67:375–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekonyela R, Palmer JM, Bok JW, Jain S, Berthier E, Forseth R, et al. RsmA regulates Aspergillus fumigatus gliotoxin cluster metabolites including cyclo(L-Phe-L-Ser), a potential new diagnostic marker for invasive aspergillosis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e62591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K, Keller NP. Genetic involvement of a cAMP-dependent protein kinase in a G protein signaling pathway regulating morphological and chemical transitions in Aspergillus nidulans . Genetics. 2001;157:591–600. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.2.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrimali D, Shanmugam MK, Kumar AP, Zhang J, Tan BK, Ahn KS, Sethi G. Targeted abrogation of diverse signal transduction cascades by emodin for the treatment of inflammatory disorders and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2013;341:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol. 2011:7. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson TJ. Genetic and biosynthetic studies of the fungal prenylated xanthone shamixanthone and related metabolites in Aspergillus spp. revisited. Chembiochem. 2012;13:1680–1688. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spikes S, Xu R, Nguyen CK, Chamilos G, Kontoyiannis DP, Jacobson RH, et al. Gliotoxin production in Aspergillus fumigatus contributes to host-specific differences in virulence. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:479–486. doi: 10.1086/525044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugui JA, Pardo J, Chang YC, Müllbacher A, Zarember KA, Galvez EM, et al. Role of laeA in the regulation of alb1, gliP, conidial morphology, and virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus . Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:1552–1561. doi: 10.1128/EC.00140-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szewczyk E, Nayak T, Oakley CE, Edgerton H, Xiong Y, Taheri-Talesh N, et al. Fusion PCR and gene targeting in Aspergillus nidulans . Nat Protoc. 2006;1:3111–3120. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner WB. The production of trypacidin and monomethylsulochrin by Aspergillus fumigatus . J Chem Soc [Perkin 1] 1965:6658–6659. doi: 10.1039/jr9650006658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twumasi-Boateng K, Yu Y, Chen D, Gravelat FN, Nierman WC, Sheppard DC. Transcriptional profiling identifies a role for BrlA in the response to nitrogen depletion and for StuA in the regulation of secondary metabolite clusters in Aspergillus fumigatus . Eukaryot Cell. 2009;8:104–115. doi: 10.1128/EC.00265-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, Ye J, Faircloth BC, Remm M, Rozen SG. Primer3 – new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay S, Torres G, Lin X. Laccases involved in 1,8-dihydroxynaphthalene melanin biosynthesis in Aspergillus fumigatus are regulated by developmental factors and copper homeostasis. Eukaryot Cell. 2013;12:1641–1652. doi: 10.1128/EC.00217-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Waeyenberghe L, Baré J, Pasmans F, Claeys M, Bert W, Haesebrouck F, et al. Interaction of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia with Acanthamoeba castellanii parallels macrophage-fungus interactions. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2013;5:819–824. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiemann P, Guo CJ, Palmer JM, Sekonyela R, Wang CC, Keller NP. Prototype of an intertwined secondary-metabolite supercluster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:17065–17070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313258110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woloshuk CP, Foutz KR, Brewer JF, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland TE, Payne GA. Molecular characterization of aflR, a regulatory locus for aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2408–2414. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2408-2414.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue T, Nguyen CK, Romans A, Kontoyiannis DP, May GS. Isogenic auxotrophic mutant strains in the Aspergillus fumigatus genome reference strain AF293. Arch Microbiol. 2004;182:346–353. doi: 10.1007/s00203-004-0707-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X-L, Awakawa T, Wakimoto T, Abe I. Induced production of novel prenyldepside and coumarins in endophytic fungi Pestalotiopsis acaciae . Tetrahedron Lett. 2013;54:5814–5817. [Google Scholar]

- Yin WB, Baccile JA, Bok JW, Chen Y, Keller NP, Schroeder FC. A nonribosomal peptide synthetase-derived iron(III) complex from the pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:2064–2067. doi: 10.1021/ja311145n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.