Abstract

American elderberries are commonly collected from wild plants for use as food and medicinal products. The degree of phytochemical variation amongst wild populations has not been established and might affect the overall quality of elderberry dietary supplements. The three major flavonols identified in elderberries are rutin, quercetin and isoquercetin. Variation in the flavonols and chlorogenic acid was determined for 107 collections of elderberries from throughout the eastern United States using an optimized high performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection method. The mean content was 71.9 mg per 100g fresh weight with variation ranging from 7.0 to 209.7 mg per 100 g fresh weight within the collected population. Elderberries collected from southeastern regions had significantly higher contents in comparison with those in more northern regions. The variability of the individual flavonol and chlorogenic acid profiles of the berries was complex and likely influenced by multiple factors. Several outliers were identified based on unique phytochemical profiles in comparison with average populations. This is the first study to determine the inherent variability of American elderberries from wild collections and can be used to identify potential new cultivars that may produce fruits of unique or high-quality phytochemical content for the food and dietary supplement industries.

Keywords: Sambucus nigra subsp. canadensis, American Elderberry, Wild Collections, Flavonols, Phenolic Acids, HPLC-UV, Geographic Variation, Berries, Food analysis, Food composition

1. Introduction

American elderberry, Sambucus nigra subsp. canadensis (L.) Bolli (Adoxaceae), is native to eastern and central North America and Central America. Elderberry shrubs are multi-stemmed with small, weak branches that can easily bend under the weight of mature fruit clusters (Martin & Mott, 1997). These clusters can contain as many as 2000 elderberries with diameters ranging from 5 to 9 mm for the individual berries (Charlebois, 2007). Ripe berries have deep purple/black colors that act as attractants for birds and mammals that consume the fruits and disperse seeds. The shrubs are commonly found growing along forest edges, roadsides and in open disturbed land, allowing accessibility for those relying on wild collections.

Traditionally, American elderberries and elderflowers are used in herbal remedies primarily for colds and flu and for anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and tonic activities (Moerman, 1988; Drapeau & Charlebois, 2012; Foster & Duke, 2014). Elderberries are used to manufacture foods such as jams, pies, wines and juices. The majority of the products created with American elderberries come from wild collections, while most European elderberry products are manufactured with berries from established cultivars grown at commercial production sites (Thomas et al., 2013). There are several established American elderberry cultivars that were developed decades ago at agricultural research stations, some of which have high quality berry production (Charlebois, 2007). Elderberries are more frequently promoted for their medicinal benefit, which has spiked demand for their products. This increased demand for berries and flowers has enabled the growth of small and large scale production sites throughout the United States and Canada. These sites are using established cultivars and/or wild cuttings for their elderberry production (Thomas et al., 2009). Although studies of American elderberries have focused on established cultivars, it is important to establish determinants of quality for wild elderberries used in food and medicinal products (Drapeau & Charlebois, 2012; Lee & Finn, 2007; Thomas et al., 2008).

Although small in size, elderberries are packed with non-nutritive compounds responsible for their high antioxidant properties (Ozgen et al., 2009; Mikulic-Petrovsek et al., 2012). As the majority of research relating to these phytochemicals in elderberries focuses on established cultivars, little is known about the natural phytochemical distribution of wild American elderberries. Ozgen et al. (2009) determined the total phenolic content of wild American elderberries, after transplantation to a single agricultural site, where they reported similar phenolic contents in comparison with previous reports of American elderberry cultivars (Lee & Finn, 2007). This report gave little information on the wild collections, and transplanting the shrubs minimized environmentally mediated variation, which is unlike the conditions of commercial wild harvest for food production. It is known that phenolic compounds can provide protective effects from pests, predators and environmental stressors such as altitude and UV radiation (Ozgen et al., 2009; Reiger et al., 2008), suggesting that environmental factors may affect the phytochemical composition of wild elderberries.

In order to establish the phytochemical variability of wild American elderberries, collection of wild elderberry fruits was undertaken over a two-year period throughout the eastern United States. Profiles of select flavonols and chlorogenic acid of the berries were determined and those from different geographic regions compared using high performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet (HPLC-UV) detection. The goal of this project was to determine whether phytochemical diversity within this species is great enough to create a potential for selection of source material for new cultivars based on increased phytochemical content.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Plant Collections

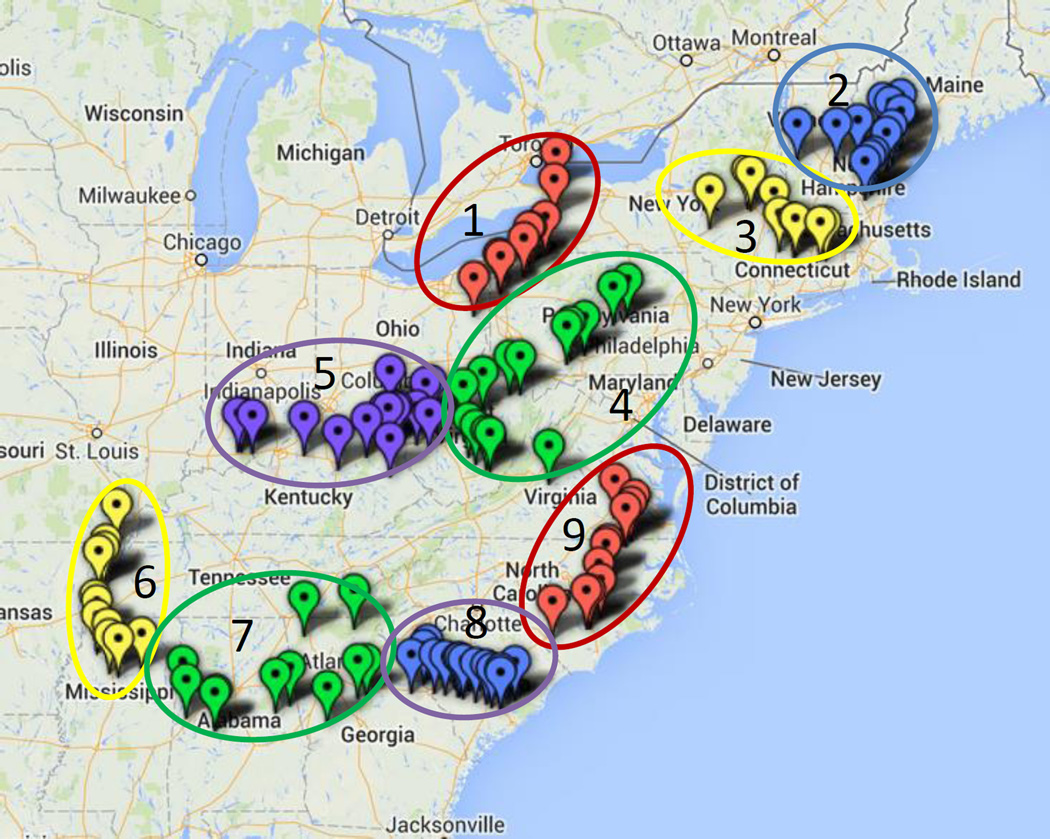

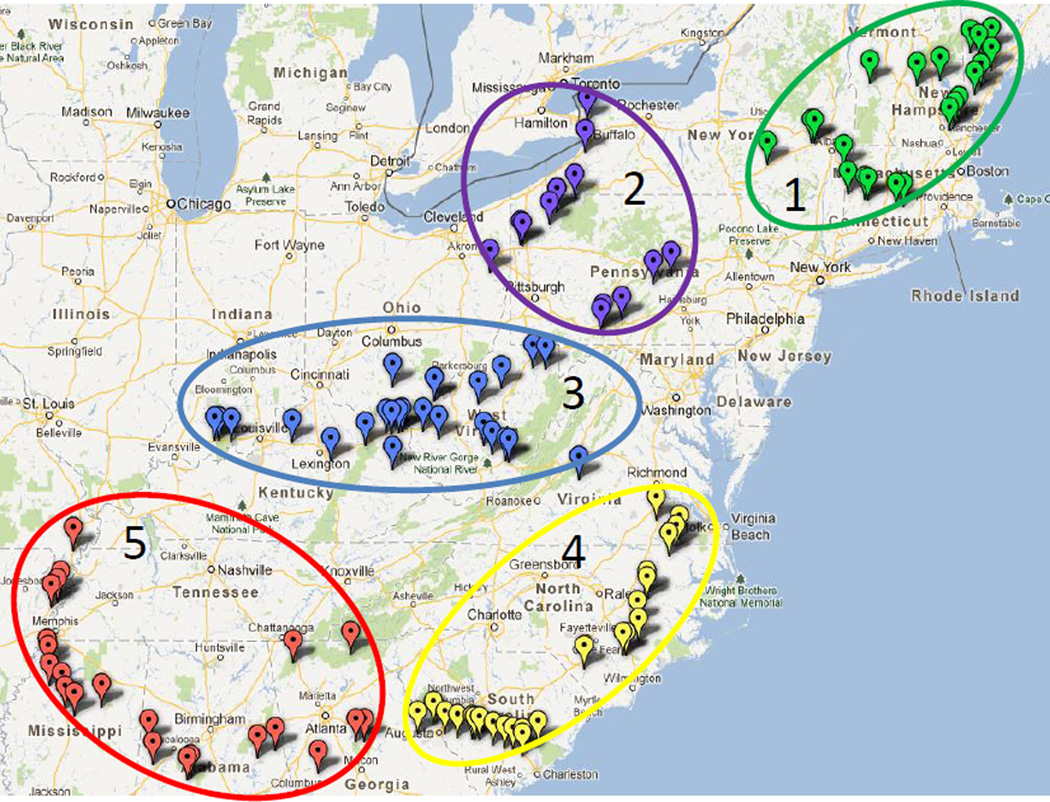

Wild collections of Eastern American Elderberry (Sambucus nigra subsp. canadensis) took place in 2010 and 2011 throughout the eastern United States. A total of 107 samples were collected. The following states and number of collections per state are summarized: Alabama (7), Arkansas (3), Connecticut (5), Georgia (4), Indiana (1), Kentucky (9), Maine (6), Missouri (2), Mississippi (7), North Carolina (9), New Hampshire (5), New York (6), Ohio (2), Pennsylvania (11), South Carolina (14), Virginia (3), Vermont (1) and West Virginia (12). Figure 1 shows the distribution of wild elderberry collections. The date and exact coordinates were recorded for all collections, and voucher specimens were preserved in the Missouri Botanical Garden herbarium. Berries were frozen after collection and stored at −20 °C until use for chemical analysis.

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of American elderberry (Sambucus nigra subsp. canadensis) collections in the Eastern United States.

2.2 Reagents and Reference Materials

HPLC grade methanol, acetonitrile, tetrahydrofuran and isopropanol were purchased from VWR International (Mississauga, ON, Canada). HPLC grade phosphoric acid and acetic acid were purchased from VWR International. The primary grade reference standards chlorogenic acid (purity: 93.9%), rutin (purity: 89.3%), quercetin (purity: 93.4%) and isoquercetin (purity: 93.2%) were purchased from Chromadex (Irvine, CA, USA). Water was deionized using a Barnstead water purification system (Fisher Scientific, Ottawa, ON, Canada). Stock solutions of the reference standards were prepared at 1000 µg/mL. Each day mixed calibration solutions ranging from 0.5 to 200 µg/mL were prepared.

2.3 Sample Preparation

Several elderberry clusters were collected from individual trees and pooled together as a single collection. Elderberries were separated from the stems and freeze dried. Dried samples were ground to less than 500 µm particle size to ensure a homogeneous sample from each collection location. 150 mg of dried berries were extracted with 15 mL of extraction solvent composed of water:methanol:acetic acid (66:30:4 v/v). The samples were extracted using a wrist action shaker for 1 hour and then centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 minutes. 1 mL of supernatant was filtered with a 0.22 µm Teflon filter into an HPLC vial and subjected to HPLC analysis described in Section 2.4. Each individual collection was prepared in triplicate.

2.4 HPLC Analysis

The analytical separation was adopted from an in-house modified method for flavonoids in leaves and berries (Upton, 1999). An Agilent 1290 Infinity Binary Liquid Chromatography system equipped with an in-line degasser, autosampler, binary pump and a diode array ultraviolet (UV) detector (Agilent Technologies, Mississauga, ON, Canada) was used. The separation was achieved on a Kinetex® 2.6 micron C18 100Å (4.6 × 100 mm, 2.6 µm) column (Phenomenex, Terrance, CA, USA). The composition of the mobile phase was: (A) 0.1% phosphoric acid in water and (B) Tetrahydrofuran/Acetonitrile/Isopropyl alcohol (4:4:1 % v/v). The separation was as follows: 0–10 mins: 5–15% B, 10–22 mins: 15–50% B, 22–22.90 mins: 50% B. The column was subsequently washed with 80% B and re-equilibrated with 5% B prior to injection of the next sample. The flow rate was 0.6 mL/min and the column temperature was 20 °C. The injection volume was 5 µL. UV spectra were collected from 200 to 400 nm where 325 nm was used for the quantitation of chlorogenic acid and 375 nm was used for the quantitation of rutin, quercetin and isoquercetin. Data was processed using OpenLab software (Agilent Technologies).

The elderberry samples were separated into seven batches composed of 14–16 samples per batch. Each sample was extracted in triplicate. The mixed calibration solutions were analyzed at the beginning of each batch. The berry extractions followed the calibration solutions, with quality control (QC) samples containing approximately 25 µg/mL of each individual standard randomly placed throughout the sequence. The coefficient of variations of the QC samples were to be maintained below 5% in order for that run to be considered acceptable.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

The flavonol and phenolic acid contents were determined with external calibration using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond WA, USA). The mean of each sample was converted to wet weight from the loss on drying data from the freeze drier. Data was imported into Solo+MIA (Eigenvector Research Inc., Manson, WA, USA). The data were preprocessed using autoscaling prior to multivariate statistical analysis. Principal component analysis (PCA) was applied to the datasets and score plots were generated for the entire data set to visualize proximity in all cases. Analysis of variance-PCA (ANOVA-PCA) was utilized to determine whether any of the factors identified had an impact on the dataset (Harrington et al., 2005). The variations in the contents between different locations were evaluated using Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance and Tukey-Kramer method for unequal sample sizes. These statistical tests were performed using Microsoft Excel 2011.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Chromatographic Analysis of Flavonols and Chlorogenic Acid

An in-house method for extraction of flavonoids in hawthorn leaves and berries was adopted for extraction in elderberries (Upton, 1999). The method was originally optimized using a multi-level factorial design evaluating extraction solvent, acid content, time and water percentage. The optimal extraction solvent was determined to be 66:30:4 methanol:water:acetic acid (% v/v) for 1 hour with wrist-action shaking. When adopted to elderberries, the repeatability was consistently less than 5% for triplicate extractions. Re-extraction of the spent berries yielded <3.0 % for individual components, which is from the residual solvent remaining in the material, therefore complete extraction of the flavonols and phenolic acids was achieved. Linearity of the calibration standards consistently produced r2 values ≥0.999 and the limits of detection were determined as 0.05 µg/mL for chlorogenic acid, 0.09 µg/mL for rutin, 0.08 µg/mL for isoquercetin and 0.1 µg/mL for quercetin. Spike recovery studies using spent materials found recovery at 100.9% for rutin.

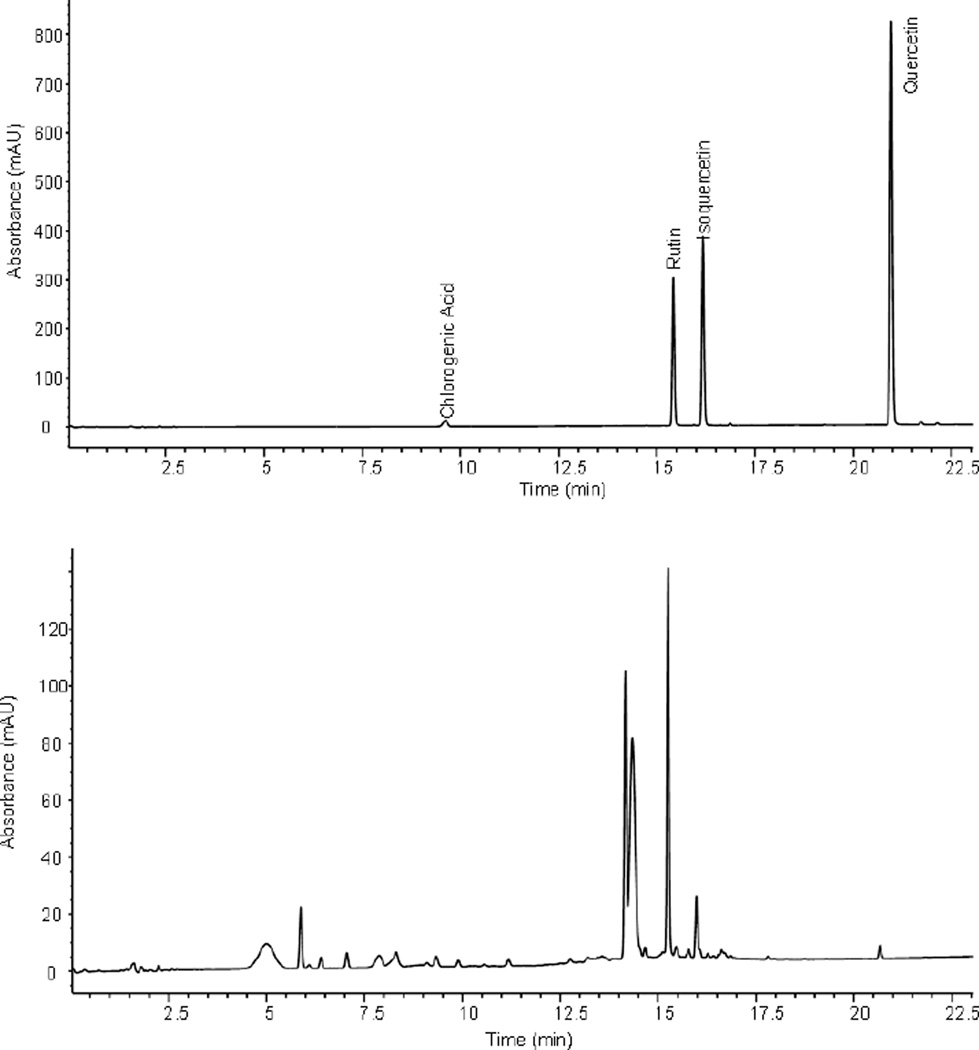

The chromatographic separation was optimized for the compounds of interest using the hawthorn method as a starting point, since the limited publications on flavonols and phenolic acid analysis in elderberries have long run times and large solvent consumption (Upton, 1999). This method was established to reduce the analytical run time for each sample due to the high number of samples and to reduce the use of organic solvents. As flavonols and chlorogenic acid are relatively polar compounds, they elute with less than 50% organic solvent in the mobile phase when using the Kinetex C18 column. The analysis time was decreased to 22 minutes and a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min, which further reduced the solvent usage compared to previously published methods (Lee & Finn, 2007; Thomas et al., 2008). The HPLC chromatogram for the individual flavonols is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

HPLC chromatograms of (a) reference standard solution and (b) American elderberry extract for flavonols and chlorogenic acid.

3.2 Flavonol and Chlorogenic Acid Content of American Elderberry Populations

The flavonols present in American elderberries include rutin, hyperoside, isoquercitin, quercetin, and kaempferol, in addition to chlorogenic acid. The most abundant flavonol has been established as rutin (Rieger et al., 2008). Lee & Finn (2007) evaluated the flavonoid content of several established American elderberry cultivars, identifying rutin, isoquercetin and chlorogenic acid contents ranging from 15–41.9 mg/100g, 2.1–7.7 mg/100g and 8.1–25.5 mg/100g respectively. Isoquercetin was quantified as rutin equivalent in their publication. The flavonols quantified in the present work were chlorogenic acid, rutin, quercetin and isoquercetin, which were quantified against individual reference standards. The variability in the individual phytochemicals is significantly higher in these wild collections, in which the contents of rutin, isoquercetin, chlorogenic acid and quercetin ranged from 3.5–170 mg/100g, 0.7–48.5 mg/100g, 0.6–45.4 mg/100g and 0–25.7 mg/100g respectively. The average of these phytochemicals and variation are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Average individual and total flavonol and chlorogenic acid contents (mg/100 g fresh weight) of wild American elderberries collected in the Eastern US (n=107).

| Flavonoid | Flavonol & chlorogenic acid content (mg /100 g fresh weight) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Minimum | Maximum | Standard deviation | RSD (%) | |

| Chlorogenic Acid | 10.7 | 0.7 | 53.5 | 9.6 | 89.3 |

| Rutin | 52.5 | 3.5 | 170 | 32.5 | 61.8 |

| Quercetin | 2.2 | nd* | 25.6 | 3.2 | 146 |

| Isoquercetin | 6.5 | 0.7 | 48.5 | 5.8 | 88.8 |

| Total | 71.9 | 7.0 | 2109.7 | 39.8 | 55.3 |

nd=0.02 mg/100 g fresh weight

The highest content of the individual berry collections was 209.7 mg/100 g FW and the lowest was 7.0 mg/100g FW, indicating that there was about a 30-fold difference in flavonol content among sampled populations. This was calculated as the sum of the three flavonols and chlorogenic acid combined. The overall quality of wild American elderberries is variable, which may affect the quality of food that are manufactured from these collections and, if flavonols are among the important active compounds, the efficacy of medicinal products. Latti et al. (2008) compared the total anthocyanin content in wild bilberry collections in Finland and also identified large variances among populations. Their study similarly was unable to determine the factors responsible for variance, as there may be many contributing factors simultaneously.

3.3 Individual Flavonol and Chlorogenic Acid Variation

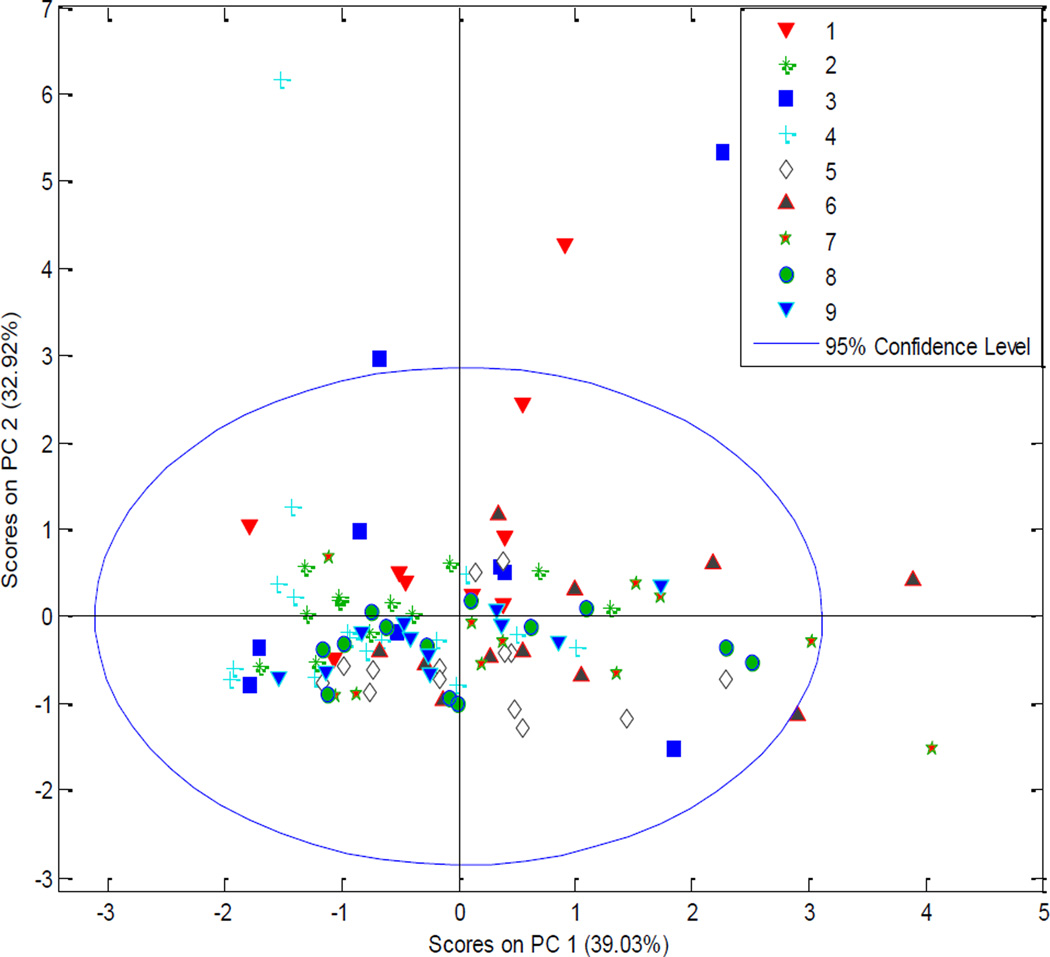

With over 100 wild elderberry collections, there was interest in determining if the geographical location of the plants influenced their phytochemical contents by evaluating the content of rutin, chlorogenic acid, quercetin and isoquercetin individually. The collections were visually divided into 9 zones based on their geographical locations (see Figure 1). These zones contained between 9 and 16 collections. The contents were evaluated with multivariate analysis (PCA) to visualize any clustering of the data. Based on the initial PCA score plot, there was no grouping of the data based on individual flavonol and chlorogenic acid contents of the berries, as shown in Figure 3, indicating that there are no differences observed among geographical zones.

Figure 3.

PCA score plot of the individual flavonols and chlorogenic acid in American elderberries separated into nine geographical zones.

There were several other proposed methods for grouping sampled populations based on environmental exposure such as hardiness zones, sunlight/rain exposure, altitude, collection year or photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) rating. PCA score plots for these other options did not show any significant clustering after separation by groups, confirming that no single factor could be identified that was responsible for variation in individual phytochemicals. The ANOVA-PCA results presented no clustering along the first component, indicating that none of the factors examined had a significant impact. Flavonol and phenolic acid production may be affected by the microclimates and environmental stressors on individual plants such as pests, UV radiation, soil composition, etc., as well as genetic variation (Lila, 2006; Ramakrishna & Ravishankar, 2011). Therefore, since contents vary considerably and the data are limited only to the four components, PCA was not suitable for evaluating the individual flavonols and chlorogenic acid based on geographical location or individual environmental stressors.

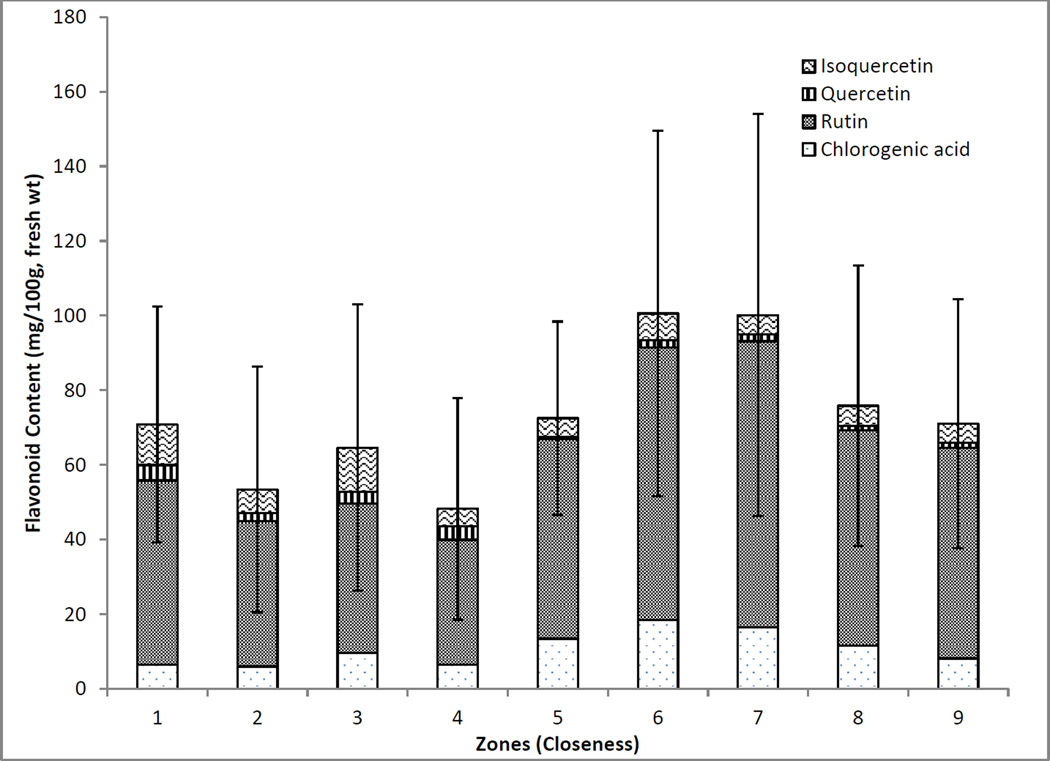

3.4 Total Flavonol and Chlorogenic Acid Variation based on Geographical Location

The average total contents (flavonols and chlorogenic acid) of samples from the original 9 zones based on geographical location (closeness) were plotted for a visual comparison as shown in Figure 4. It was evident that zones 6 and 7 had higher average levels of flavonols and chlorogenic acid in comparison with the other groups. As the number of collections varied among groups, Kruskal-Wallis and Tukey-Kramer statistical analyses were used. According to Kruskal-Wallis statistical analysis, there was a significant difference between the different groups (p=0.025) and using Tukey-Kramer, the significant differences were between zone 4 and zones 6 and 7. As zone 4 is located along the coastal regions in a more northern climate in comparison with zones 6 and 7 it is thought that the average total flavonols is impacted by the geographical location. With such a large data set, by plotting the average quantified phytochemical content per region, the effect of variability in the content of individual flavonols and chlorogenic acid among samples from a single region is minimized and regional differences are more easily identified.

Figure 4.

Total flavonol and chlorogenic acid contents of American elderberries separated into nine geographical zones. (Zone 1 n=9; Zone 2 n=12; Zone 3 n=10, Zone 4 n=16; Zone 5 n=14; Zone 6 n=11; Zone 7 n=11; Zone 8 n=13; Zone 9 n=11)

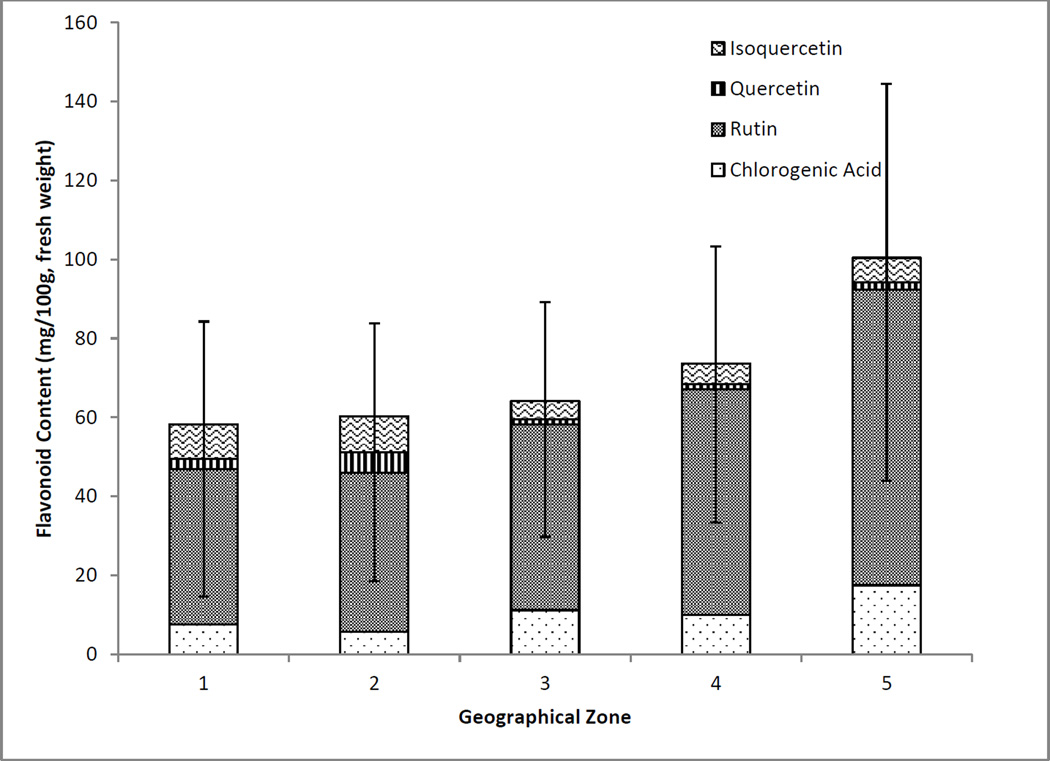

In a second analysis, the original 9 geographic zones were reduced to 5 post hoc in an attempt to create regional boundaries with maximum explanatory power as shown in Figure 5. The original zones 1 and 2 were combined, zone 3 and the northern section of 4 were combined, the southern section of 4 and 5 were combined, 6 and 7 were combined, and 8 and 9 were combined. The number of collections in of these larger zones ranged from 14 to 25. Kruskal-Wallis analysis confirmed there was a statistical difference between the zones (p=0.005). Using Tukey-Kramer it was determined that the statistically significant differences were observed between zone 5 and zones 1, 2 and 3. This confirms that there is a correlation between the geographical location of wild collections and the total flavonol and chlorogenic acid content.

Figure 5.

American elderberry collections separated into five broader geographical zones.

Zones 4 and 5 both had higher overall flavonols and chlorogenic acid compared with zones 1 to 3 as shown in Figure 6. These elderberry shrubs are located in more southern regions, which have warmer climates in comparison with the more northern regions. It was further determined that the more interior the southern collections, the higher the contents which is likely due to higher chlorogenic acid and rutin. Cheng et al. (2014) observed increased anthocyanin and flavonol content in Vaccinium uliginosum berries at increased altitude, which was suspected to be attributed to increased solar radiation. By contrast, Latti et al. (2008) found that wild bilberry anthocyanin contents were significantly lower in southern populations in comparison to central and northern regions when the collected population was grouped into small distinct zones.

Figure 6.

Average flavonol and chlorogenic acid content of American elderberries separated into 5 broader geographical zones. (Zone 1 n=21; Zone 2 n=15; Zone 3 n=21; Zone 4 n=24; Zone 5 n=22)

Average quercetin content was higher in samples from zone 2 compared with the other regions and chlorogenic acid content was lower, while the rutin content of samples from zone 2 was similar to those from zones 1 and 3. The average values for flavonols and chlorogenic acid content may be affected by outliers that are present in each of the regions, although the existence of such outliers shows that multiple factors affect phytochemical content.

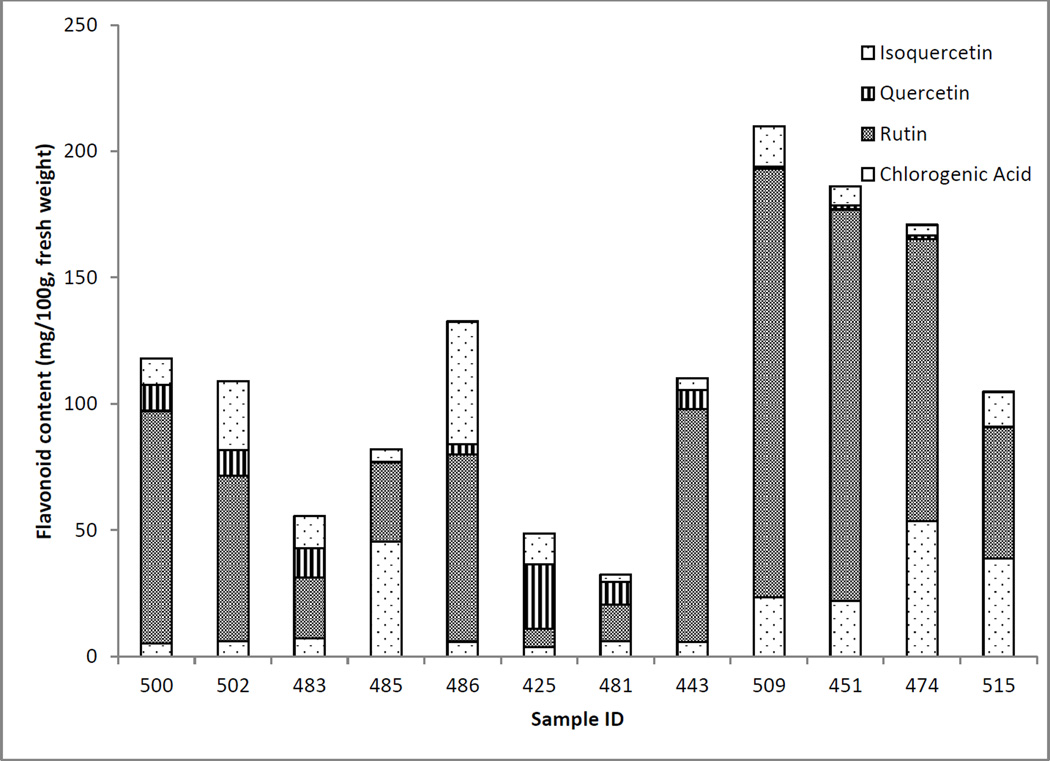

3.3 Elderberry Outliers

Literature regarding the flavonoid content of elderberries identifies rutin as the most abundant (Lee & Finn, 2007; Rieger et al., 2008). Based on the plots of average total flavonoids and chlorogenic acid, this appears to be the case. Although this average appears to be consistent, it is not necessarily the case for all wild elderberry collections from the Eastern United States.

Using multivariate analysis, 12 outliers were identified from the 107 collections. The outliers were characterized by unusual individual flavonol and chlorogenic acid profiles; their corresponding contents are plotted in Figure 7. The first 7 collections were identified in the northern groups, while the last 5 were identified in the southern regions. There is a clear distinction between the outliers identified in the southern and northern regions. The majority of the southern outliers have considerable levels of chlorogenic acid and rutin. Samples 509, 542 and 474 have the three highest total flavonols and chlorogenic acid throughout the collected population.

Figure 7.

Flavonol and chlorogenic acid profiles of elderberry samples that were identified as statistical outliers relative to other collected populations.

In comparison, the outliers identified in the more northern regions have different phytochemical profiles, in which on average their total contents are lower in comparison with the southern outliers. For example, sample 425 has a low total flavonol and chlorogenic acid content, a very small amount of rutin, and a considerable amount of quercetin. There may have been some degradation of rutin in these berries, which formed the high content of quercetin, or another factor that inhibited the formation of rutin in this plant.

The outliers identified did not include the samples with the lowest contents. The two samples with lowest flavonol and chlorogenic acid content, collected from West Virginia and Pennsylvania, had a total content of 7.0 mg/100 g and 7.1 mg/100 g respectively. As these two samples had very similar levels, they were not considered outliers.

Many factors, including genetic and environmentally mediated variation and perhaps slight differences in fruit ripeness, can affect the flavonol and chlorogenic acid contents in berries. As this work was performed on wild American elderberry, the environmental factors that may have affected the phytochemicals and composition were uncontrolled. In order to determine if variation in the flavonol and chlorogenic acid contents of wild elderberry collections is primarily environmental or genetic in origin, the next step in this work is to collect cuttings from the collections which were identified as interesting either due to high or low total flavonols or due to unique profiles and bring them into cultivation at a single site. Those collections could potentially be used to establish cultivars that have berries with improved phytochemical profiles.

4. Conclusion

Over 100 cuttings of wild elderberry fruits were collected from throughout the Eastern United States ranging from as far north as Maine down to Alabama and Georgia and as far west as Mississippi and Kansas. The berries were evaluated for flavonol and chlorogenic acid contents to determine the variations within geographical regions. The berries growing in the southern regions were found to have higher average total flavonol and chlorogenic acid contents than those growing in more northern regions, especially among populations growing in more interior regions. Several samples were identified as outliers in comparison to the average elderberry flavonol profiles. These had significantly higher total flavonols, or unique phytochemical profiles, which may be due to genetic or environmental factors. The future direction of this work is to collect the propagatable material of phytochemically unusual wild elderberry populations to determine if their flavonol and chlorogenic acid contents are influenced primarily by genetic or environmental variation and for potential cultivar development.

Highlights.

We surveyed flavonol content of wild American elderberry throughout Eastern US.

Substantial variation in content of prominent flavonols was observed.

A correlation was identified with geographical location of collections.

Findings established regions or populations of elderberry with superior phytochemistry.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by Grant Number P50AT006273 (MU Center for Botanical Interaction Studies) from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicines (NCCAM), the Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS), and the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCCAM, ODS, NCI, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Charlebois D. Elderberry as a Medicinal Plant. In: Janick J, Whipkey A, editors. Issues in New Crops and New Uses. Alexandria, VA: ASHS Press; 2007. pp. 284–292. [Google Scholar]

- Drapeau R, Charlebois D. American elder cultivation under cold climates: Potential and limitations. Canadian Journal of Plant Science. 2012;92:473–484. [Google Scholar]

- Foster S, Duke JA. Peterson Field Guide to Medicinal Plants and Herbs of Eastern and Central North America. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington P, Vieira NE, Espinoza J, Kae Nien J, Romero R, Yergey AL. Analysis of variance-principal component analysis: A soft tool for proteomic discovery. Analytica Chemica Acta. 2005;544:118–127. [Google Scholar]

- Latti AK, Riihinen KR, Kainulainen PS. Analysis of anthocyanin variation in wild populations of bilberry (Vaccimium myrtillus L.) in Finland. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2008;56:190–196. doi: 10.1021/jf072857m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Finn CE. Anthocyanins and other polyphenolics in American elderberry (Sambucus canadensis) and European elderberry (S. nigra) cultivars. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2007;87:2665–2675. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lila MA. The nature-versus-nurture debate on bioactive phytochemicals: the genome versus terrior. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2006;86:2510–2515. [Google Scholar]

- Martin CO, Mott SP. Technical report EL-97-14. Ecosystem Management and restoration research program; 1997. American Elder (Sambucus canadensis) Section 7.5.7, US army corps of engineers wildlife resources management manual. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulic-Petkovsek M, Slatnar A, Stampar F, Veberic R. HPLC-MSn identification and quantification of flavonol glycosides in 28 wild and cultivated elderberry species. Food Chemistry. 2012;135:2138–2146. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.06.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moerman DE. Native American Ethnobotany. Portland, OR: Timber Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ozgen M, Scheerens JC, Reese RM, Miller RA. Total phenolic, anthocyanin contents and antioxidant capacity of selected elderberry (Sambucus canadensis L.) accessions. Pharmacognosy Magazine. 2010;6:198–203. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.66936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishna A, Ravishankar GA. Influence of abiotic stress signals on secondary metabolites in plants. Plant Signaling & Behavior. 2011;6:1720–1731. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.11.17613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiger G, Muller M, Guttenberger H, Bucar F. Influence of altitudinal variation on the content of phenolic compounds in wild populations of Calluna vulgaris, Sambucus nigra and Viccinium myrtillis. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2008;56:9080–9086. doi: 10.1021/jf801104e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AL, Byers PL, Finn CED, Chen YC, Rottinghaus GE, Malone AM, Applequist WL. Occurrence of rutin and chlorogenic acid in elderberry leaf, flower and stem in response to genotype, environment and season. Acta Horticulturae. 2008;76:197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AL, Byers PL, Ellersieck MR. Productivity and characteristics of american elderberry in response to various pruning methods. HortScience. 2009;44:671–677. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AL, Perkins-Veazie P, Byers PL, Finn CE, Lee J. A comparison of fruit characteristics among diverse elderberry genotypes grown in Missouri and Oregon. Journal of Berry Research. 2013;3:159–168. doi: 10.3233/JBR-130054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton R. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) for c-glycosylated flavonoids measured as vitexin. Santa Cruz, CA, USA: American Herbal Pharmacopeia; 1999. Hawthorn Leaf with Flower. Crataegus spp. American Herbal Pharmacopeis and Therapeutic Compendium; pp. 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wang LJ, Su S, Wu J, Du H, Li SS, Huo JW, Zhang Y, Wang LS. Variation of anthocyanins and flavonols in Vaccinium uliginosum bery in Lesser Khingan Mountains and its antioxidant activity. Food Chemistry. 2014;160:357–364. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.03.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]