Abstract

Major terrorist events, such as the recent attacks in Ankara, Sinai, and Paris, can have profound effects on a nation’s values, attitudes, and prejudices. Yet psychological evidence testing the impact of such events via data collected immediately before and after an attack is understandably rare. In the present research, we tested the independent and joint effects of threat (the July 7, 2005, London bombings) and political ideology on endorsement of moral foundations and prejudices among two nationally representative samples (combined N = 2,031) about 6 weeks before and 1 month after the London bombings. After the bombings, there was greater endorsement of the in-group foundation, lower endorsement of the fairness-reciprocity foundation, and stronger prejudices toward Muslims and immigrants. The differences in both the endorsement of the foundations and the prejudices were larger among people with a liberal orientation than among those with a conservative orientation. Furthermore, the changes in endorsement of moral foundations among liberals explained their increases in prejudice. The results highlight the value of psychological theory and research for understanding societal changes in attitudes and prejudices after major terrorist events.

Keywords: threat, terrorism, morality, prejudice

The July 7, 2005 (7/7), bombings on the London Underground and bus transport system were an Al Qaeda attack orchestrated by three British-born Muslims from Pakistani immigrant families and one Jamaican man who had converted to Islam. The attack left 52 people dead and 770 injured. The 7/7 bombings are the first and only major terrorist attack to have affected London this century.

Public reactions following major terrorist incidents, such as the November 13, 2015, attacks on Paris, are often difficult to gauge, because the aftermath provokes a focus on the horror of the attack and the trauma suffered by victims. But beyond these immediate reactions, research is necessary to test whether such incidents polarize people’s existing ideologies, as might be suggested by terror-management theory (Greenberg & Jonas, 2003), or shift people only toward the conservative end of the spectrum, as suggested by the motivated-social-cognition model of conservatism (Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski, & Sulloway, 2003).

The present research drew on a unique data set that allowed us to compare nationally representative samples of the British population about 6 weeks before and 1 month after the 7/7 bombings. We investigated people’s endorsement of fundamental moral principles, their political ideology, and their attitudes toward Muslims and immigrants. This unique evidence enabled us to test predictions drawn from moral-foundations theory and from theories of political ideology and prejudice.

Moral-Foundations Theory

According to moral-foundations theory (Graham, Haidt, & Nosek, 2009; Haidt & Graham, 2007), liberals and conservatives prioritize different visions of a good society. Liberals prioritize two specific moral foundations—harm-care and fairness-reciprocity (or fairness). In contrast, conservatives prioritize three additional moral foundations—in-group–loyalty (or in-group), authority-respect (or authority), and purity-sanctity (or purity).

Moral-foundations theory suggests that each of the five foundations may have different associations with negative outcomes such as prejudice. Kugler, Jost, and Noorbaloochi (2014) showed that the in-group, respect, and purity foundations are positively related to intergroup hostility and discrimination, whereas the harm-care and fairness-reciprocity foundations are negatively related to these variables. In the current research, we directly tested whether the 7/7 attacks affected people’s prioritization of different moral foundations and whether different moral foundations were associated with prejudices toward Muslims and immigrants. Muslims can be considered the immediately relevant out-group for the majority of the population because the terrorist attack was directly linked to Islamic fundamentalism; immigrants can be considered a more general out-group because the attackers were non-White and second-generation immigrants.

Conservatism as Motivated Social Cognition

People may adopt ideological belief systems to satisfy their psychological needs (e.g., to reduce threat). Conservatism is associated with lowered fear and uncertainty, the avoidance of change and ambiguity, and the justification of inequality (Jost et al., 2003). An important social psychological insight is that, beyond individual differences associated with conservatism, conservative tendencies can be affected by contextual changes. Various studies using limited ad hoc or student samples have shown that participants respond to contextual threats by shifting toward conservative positions (e.g., Bonanno & Jost, 2006; Echebarria-Echabe & Fernández-Guede, 2006; Florian, Mikulincer, & Hirschberger, 2001; Landau et al., 2004; McGregor, Nail, Marigold, & Kang, 2005; McGregor, Zanna, Holmes, & Spencer, 2001; Ullrich & Cohrs, 2007).

Drawing on the motivated-social-cognition theory of Jost et al. (2003), Nail, McGregor, Drinkwater, Steele, and Thompson (2009) proposed, and provided experimental evidence for, the reactive-liberals hypothesis, which proposes that conservatives constantly feel under threat and are therefore less reactive to situational threats than are liberals, who become more attitudinally conservative following situational threats (see also Hetherington & Weiler, 2009). Indeed, van der Toorn, Nail, Liviatan, and Jost (2014) also showed that after experimental threat manipulations, liberals became more patriotic, but conservatives did not. This shift effectively eliminated their previous ideological gap in patriotism.

Nevertheless, other research has shown that liberals become more liberal after threats, whereas conservatives become more conservative (Castano et al., 2011), and that people high in authoritarianism actually respond to threat more strongly than people low in authoritarianism (Feldman & Stenner, 1997). The current research directly tested the reactive-liberals hypothesis by exploring whether liberals became more attitudinally conservative after the 7/7 bombings.

The Present Research

Prior research has indicated that liberals and conservatives prioritize different moral foundations and that threats may produce greater increases in conservatism among liberals than among conservatives. Recent research has reconciled the moral-foundations theory and the motivated-social-cognition theory to examine social attitudes (e.g., Kugler et al., 2014; Van Leeuwen & Park, 2009). This is an essential step in the literature given that both theories examine people’s attitudes as a function of their political ideology. We propose that psychological accounts of social responses to threat (Bassett, Van Tongeren, Green, Sonntag, & Kilpatrick, 2015; Echebarria-Echabe & Fernández-Guede, 2006) can also be enriched by integrating insights from these two theories.

A significant limitation of prior research has been the use of relatively small-scale student or opportunity samples, which makes it difficult to evaluate the generalizability or the real-world implications of theory and evidence. In the present research, we addressed this limitation by using two nationally representative samples surveyed about 6 weeks before and 1 month after the 7/7 bombings. We tested (a) whether a major terrorist event affected moral foundations and prejudice, (b) whether this effect differed among liberals and conservatives, and (c) whether effects of threat and political orientation on prejudice were mediated by specific moral foundations.

Hypotheses

On the basis of the motivated-social-cognition theory and moral-foundations theory, we hypothesized that the elevated threat from the 7/7 bombings should increase (a) people’s prioritization of conservative relative to liberal foundations and (b) people’s prejudice. On the basis of the reactive-liberals hypothesis we predicted that this effect would be larger among liberals than among conservatives. Thus, differences in threat (before 7/7 vs. after 7/7) should interact with political orientation to predict prioritization of moral foundations and prejudice. Finally, we predicted that differences in endorsement of the foundations before and after 7/7 should explain differences in prejudices.

Method

Participants and design

Two cross-sectional nationally representative surveys designed by Abrams and Houston (2006) were conducted approximately 6 weeks before and 1 month after the July 7 attacks in London. Participant age ranged from 16 to 98 years (M = 45.76, SD = 19.18). The majority of participants were White (87.1%) and non-Muslim (95.4%). London residents made up 14.4% of respondents (for further information, see the Supplemental Material available online).

Procedure

TNS United Kingdom (U.K.) was commissioned by the U.K. government’s Women and Equality Unit (now called the Government Equalities Office) to collect the data through its omnibus face-to-face computer-assisted personal interviews survey series (for details of the method and measures employed for the two surveys in the present research, see Abrams & Houston, 2006). Sample sizes were prescribed and defined to provide reliable data from a representative sample of the British population. We were not involved in the recruitment or interviewing of respondents. The two surveys used identical sampling and interview methods and were administered to nationally representative samples of people who were older than 16 years and resided in England, Scotland, or Wales. To avoid response sets and biases, we counterbalanced left and right scale anchor points between participants and rotated item orders within sections of the survey.

Measures

Moral foundations

Four of the five moral foundations were assessed in this research (i.e., in-group–loyalty, authority-respect, fairness-reciprocity, and harm-care). Each of these is clearly relevant to the social implications of a terrorist attack because such attacks may directly threaten the national in-group, may directly challenge authority (which governments usually try to reassert rapidly), may instigate media focus on whether some groups are being treated unfairly (e.g., whether Muslims or immigrants have “too many rights”), and may prompt governments to debate whether to retaliate and inflict harm on the terrorists (e.g., wage a “war on terror”; see Breton, 2010; Clarke, 2008; Landau et al., 2004). At the time of the surveys, the moral-foundations theory was in its infancy (Haidt & Joseph, 2004); therefore, we operationalized these four moral foundations by using two measures from a short form of the Schwartz Values Inventory (Schwartz, 2003) and two other measures developed by us for the purposes of this survey. We recognize that these are not perfect measures of moral foundations. Nevertheless, the moral-foundations framework provides a useful way to specify predictions for the different types of measures, and we carefully mapped the measures onto the definitions of relevant moral foundations as defined by Haidt and Graham (2007, pp. 103–105).

In-group–loyalty

The in-group foundation was assessed by asking participants to rate their agreement with the following item: “I feel loyal to Britain despite any faults it may have.” Participants responded on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Authority-respect

The authority foundation was assessed by asking participants to rate the extent to which they believed that people should do what they are told. Specifically, participants responded to the item “I think people should follow rules at all times, even when no-one is watching.” They responded on a scale from 1 (not at all like me) to 6 (very much like me).

Harm-care

The harm foundation was assessed by asking participants to respond to the item “I want everyone to be treated justly, even people I do not know. It is important to me to protect the weak in society.” Participants responded on a scale from 1 (not at all like me) to 6 (very much like me).

Fairness-reciprocity

The fairness foundation was assessed by asking participants to rate their agreement with the following item: “There should be equality for all groups in Britain.” Participants responded on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Negative attitudes toward Muslims

Participants were asked to rate their agreement with the following two items: “Britain would begin to lose its identity if more Muslims came to live in Britain” and “British Muslims are more loyal to other Muslims around the world than they are to other people in Britain.” Participants responded on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The items correlated significantly (r = .49, p < .001), and a mean score was calculated.

Negative attitudes toward immigrants

Participants were asked to rate their agreement with the following two items: “Government spends too much money assisting immigrants (people who come to settle in Britain)” and “Immigrants increase crime rates.” Participants responded on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The items correlated significantly (r = .58, p < .001), and a mean score was calculated.

Political orientation

Participants’ political orientation was measured using the following item: “Political views can be described as more left wing (e.g., traditional Labour Party) or more right wing (e.g., Conservative Party). How would you describe your political view?” Participants responded on a scale from 1 (definitely left) to 6 (definitely right); 38% defined themselves as left wing, 35% as right wing, and 28% as neither. This result maps onto public opinion polls of the time (Ipsos MORI, 2015). Any participants who did not respond to this measure were assigned the mean score (M = 3.40, SD = 1.29) to reflect that they did not express a preference for either side of the political spectrum.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Muslim participants were excluded from analyses (4.6% across samples). Table S1 in the Supplemental Material reports the correlations as well as means, standard deviations, and confidence intervals for the key variables of interest within the pre-7/7 and post-7/7 data sets. There were some significant relationships among participants’ self-defined race, religion, age, whether they lived in or near London, and their attitudes and endorsement of moral foundations. To adjust for these demographic characteristics, we included them as covariates in subsequent analyses. However, it is worth noting that even when these covariates were not included, the results were unchanged: Significant effects remained significant, and nonsignificant effects remained nonsignificant.

Moderation analyses

Moderation analyses were conducted to test whether time (before 7/7 vs. after 7/7) interacted with political orientation to predict (a) endorsement of the in-group foundation, (b) endorsement of the fairness foundation, (c) endorsement of the authority foundation, (d) endorsement of the harm foundation, (e) attitudes toward Muslims, and (f) attitudes toward immigrants.

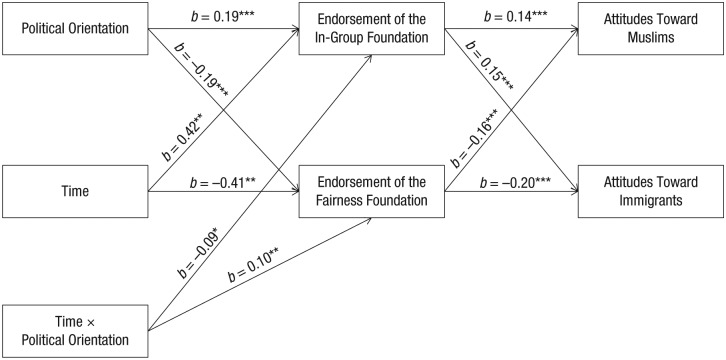

In-group foundation

There was a significant interactive effect of time and political orientation, b = −0.09, SE = 0.04, 95% CI = [−0.16, −0.02], t(1922) = −2.49, p = .013, on the endorsement of the in-group foundation (see Table S2 in the Supplemental Material). Conditional effects revealed that time increased endorsement of the in-group foundation among liberals, b = 0.21, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = [0.10, 0.32], t(1922) = 3.71, p < .001, but not among conservatives, b = 0.01, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = [−0.10, 0.12], t(1922) = 0.22, p > .250. Put differently, the difference in endorsement of the in-group foundation between liberals and conservatives before 7/7, b = 0.10, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.05, 0.16], t(1922) = 4.03, p < .001, disappeared after 7/7, b = 0.02, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [−0.03, 0.06], t(1922) = 0.61, p > .250 (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Results for the in-group foundation. The graph shows endorsement of the in-group foundation before and after the July 7, 2005, London bombings, separately for liberals (i.e., participants 1 SD above the mean for political orientation, and above the scale’s midpoint) and conservatives (i.e., those 1 SD below the mean for political orientation, and below the scale’s midpoint). Error bars represent ±1 SE of the conditional effect of time on endorsement of the in-group foundation at values of political orientation.

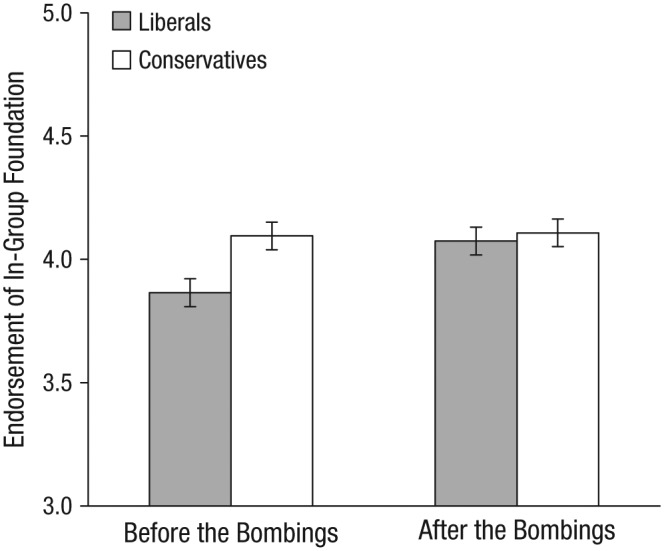

Fairness foundation

There was a significant interactive effect of time and political orientation, b = 0.10, SE = 0.04, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.17], t(1922) = 2.72, p = .007, on endorsement of the fairness foundation (see Table S2 in the Supplemental Material). Conditional effects revealed that time reduced endorsement of the fairness foundation among liberals, b = −0.19, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = [−0.30, −0.08], t(1922) = −3.40, p < .001, but not among conservatives, b = 0.02, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = [−0.09, 0.13], t(1922) = 0.41, p > .250. Put differently, the difference in endorsement of the fairness foundation between liberals and conservatives before 7/7, b = −0.09, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = [−0.14, −0.04], t(1922) = −3.59, p < .001, disappeared after 7/7, b = 0.004, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [−0.04, 0.05], t(1922) = 0.17, p > .250 (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Results for the fairness foundation. The graph shows endorsement of the fairness foundation before and after the July 7, 2005, London bombings, separately for liberals (i.e., participants 1 SD above the mean for political orientation, and above the scale’s midpoint) and conservatives (i.e., those 1 SD below the mean for political orientation, and below the scale’s midpoint). Error bars represent ±1 SE of the conditional effect of time on endorsement of the fairness foundation at values of political orientation.

Authority foundation

Contrary to expectations, our results revealed no significant main effect of time, b = −0.13, SE = 0.22, 95% CI = [−0.55, 0.30], t(1922) = −0.58, p > .250, political orientation, b = 0.05, SE = 0.10, 95% CI = [−0.15, 0.24], t(1922) = 0.47, p > .250, or their interaction, b = 0.04, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = [−0.08, 0.16], t(1922) = 0.67, p > .250, on endorsement of the authority foundation.

Harm foundation

Again, contrary to expectations, our results revealed no significant main effect of time, b = −0.18, SE = 0.14, 95% CI = [−0.46, 0.10], t(1922) = −1.26, p = .208, political orientation, b = −0.08, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = [−0.20, 0.04], t(1922) = −1.26, p = .209, or their interaction, b = 0.04, SE = 0.04, 95% CI = [−0.04, 0.12], t(1922) = 1.05, p > .250, on endorsement of the harm foundation.

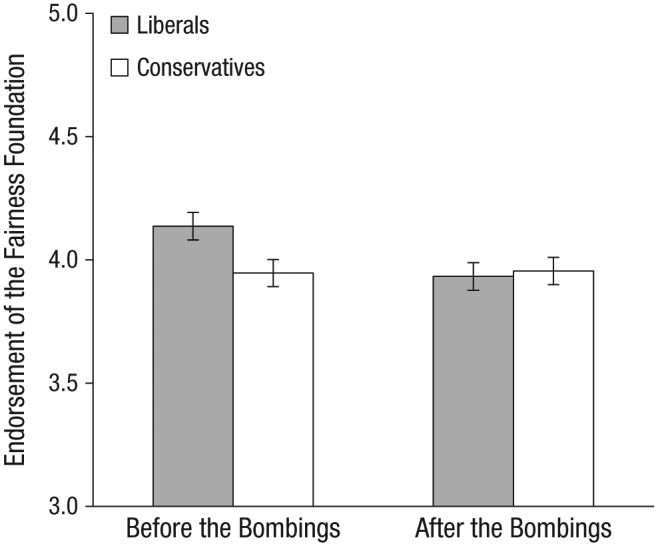

Attitudes toward Muslims

There was a significant interactive effect of time and political orientation on attitudes toward Muslims, b = −0.08, SE = 0.04, 95% CI = [−0.15, −0.01], t(1922) = −2.12, p = .034 (see Table S2 in the Supplemental Material). Time increased negative attitudes among liberal participants, b = 0.13, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.24], t(1922) = 2.34, p = .020, but did not affect attitudes among conservative participants, b = −0.04, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = [−0.15, 0.07], t(1922) = −0.64, p > .250. Put differently, the difference between liberals’ and conservatives’ attitudes was greater before 7/7, b = 0.14, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.09, 0.19], t(1922) = 5.36, p < .001, than after 7/7, b = 0.06, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.11], t(1922) = 2.53, p = .012 (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Results for attitudes toward Muslims. The graph shows prejudice toward Muslims before and after the July 7, 2005, London bombings, separately for liberals (i.e., participants 1 SD above the mean for political orientation, and above the scale’s midpoint) and conservatives (i.e., those 1 SD below the mean for political orientation, and below the scale’s midpoint). Error bars represent ±1 SE of the conditional effect of time on attitudes toward Muslims at values of political orientation.

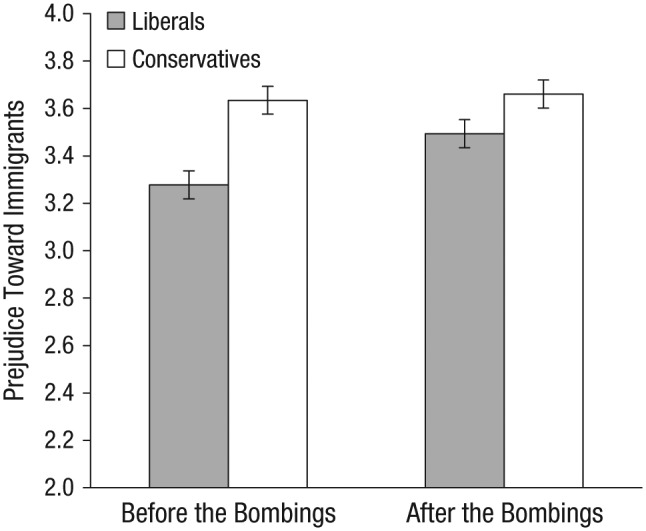

Attitudes toward immigrants

There was a significant interactive effect of time and political orientation on attitudes toward immigrants, b = −0.09, SE = 0.04, 95% CI = [−0.16, −0.01], t(1922) = −2.28, p = .023 (see Table S2 in the Supplemental Material). Time increased negative attitudes among liberal participants, b = 0.22, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = [0.10, 0.33], t(1922) = 3.63, p < .001, but did not affect attitudes among conservative participants, b = 0.03, SE = 0.06, 95% CI = [−0.09, 0.14], t(1922) = 0.45, p > .250. Put differently, the difference between liberals’ and conservatives’ attitudes was greater before 7/7, b = 0.16, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.11, 0.22], t(1922) = 5.92, p < .001, than after 7/7, b = 0.08, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.13], t(1922) = 2.90, p = .004 (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Results for attitudes toward immigrants. The graph shows prejudice toward immigrants before and after the July 7, 2005, London bombings, separately for liberals (i.e., participants 1 SD above the mean for political orientation, and above the scale’s midpoint) and conservatives (i.e., those 1 SD below the mean for political orientation, and below the scale’s midpoint). Error bars represent ±1 SE of the conditional effect of time on attitudes toward immigrants at values of political orientation.

Moderated mediation analyses

If our integration of the reactive-liberal hypothesis and moral-foundations theory is correct, the combined effects of political orientation and the 7/7 attack on prejudice should be mediated by differences in endorsement of moral foundations. Because we observed a similar pattern of results for the endorsement of the in-group and fairness foundations and for prejudice, we used moderated mediation analyses (Hayes, 2013, Model 8) to test the hypothesis that higher endorsement of the in-group foundation and lower endorsement of the fairness foundation mediate the interactive effect of time and political orientation on attitudes toward Muslims and attitudes toward immigrants.

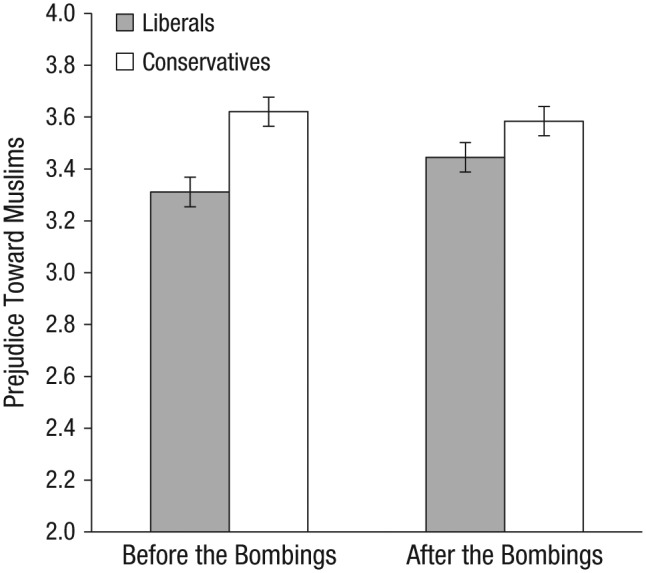

Attitudes toward Muslims

Results revealed that endorsement of the in-group foundation (indirect effect: b = −0.01, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.03, −0.003]) and the fairness foundation (indirect effect: b = −0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.03, −0.003]) significantly mediated the interactive effect of time and political orientation on attitudes toward Muslims. Specifically, the significant interactive effect of time and political orientation on attitudes toward Muslims reported earlier was eliminated when we accounted for the effects of endorsement of the in-group and fairness foundations, b = −0.05, SE = 0.04, 95% CI = [−0.12, 0.02], t(1920) = −1.38, p = .168. Note that endorsement of the in-group foundation mediated the effect of time on attitudes among liberals, b = 0.03, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.05], but not among conservatives, b = 0.002, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.01, 0.02]. Likewise, endorsement of the fairness foundation mediated the effect of time on attitudes only among liberals, b = 0.03, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.05], and not among conservatives, b = −0.004, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.02, 0.02] (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Path diagram for the moderated mediation analysis showing the influence of political orientation, time, and their interaction on attitudes toward Muslims and immigrants, as mediated by endorsement of the in-group and fairness foundations. Asterisks indicate significant paths (*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001).

Attitudes toward immigrants

Results revealed that endorsement of the in-group foundation indirect effect (b = −0.01, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.03, −0.003]) and endorsement of the fairness foundation (indirect effect: b = −0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.04, −0.004]) significantly mediated the interactive effect of time and political orientation on attitudes toward immigrants. Specifically, the significant interactive effect of time and political orientation on attitudes toward immigrants reported earlier was eliminated when we accounted for the effects of endorsement of the in-group and fairness foundations, b = −0.05, SE = 0.04, t(1920) = −1.44, p = .151, 95% CI = [−0.13, 0.02]. Endorsement of the in-group foundation mediated the effect of time on attitudes among liberals, b = 0.03, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.06], but not among conservatives, b = 0.002, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.01, 0.02]. Likewise, endorsement of the fairness foundation also mediated the effect of time on attitudes only among liberals, b = 0.04, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.07], but not among conservatives, b = −0.01, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.03, 0.02] (see Fig. 5).

Discussion

In the present research, we used data from representative samples of the British population tested before and after the London 7/7 bombings. Participants questioned after 7/7 showed greater endorsement of the in-group foundation, lower endorsement of the fairness foundation, and greater prejudice toward Muslims and immigrants. Moreover, respondents who were more conservative (as opposed to liberal) showed greater prioritization of the in-group foundation, lower prioritization of the fairness foundation, and were less favorable toward Muslims and immigrants. However, the shift in both the foundations and prejudices was larger among those with a liberal orientation than among those with a conservative orientation.

Overall, these results revealed that endorsement of the in-group and fairness foundations can be affected by changes in the intergroup context. Specifically, when an in-group is threatened by a terrorist attack, liberals become just as likely as conservatives to value the in-group foundation (measured as loyalty to the in-group)—which is usually valued more by conservatives. Furthermore, liberals reduce their prioritization of the fairness foundation (measured as support for equality for all groups), which is more in line with a conservative position. The changes in endorsement of these foundations among liberals predicted greater prejudice toward Muslims and immigrants. Therefore, after threat, liberals became more intolerant of outgroups, and this effect was explained by the endorsement of in-group and fairness foundations.

These findings have a number of implications. For psychological theory, these findings establish a meaningful connection between moral-foundations theory (Haidt & Graham, 2007) and motivated-social-cognition theory (Jost et al., 2003). This is an important bridge that should stimulate future research. The findings show that people’s moral foundations depend on context. The results also show that not all foundations are affected by threat equally, perhaps because some foundations are more relevant to the specific contextual change (i.e., the terrorist attack) than others (Breton, 2010; Clarke, 2008). Indeed, the idea that some foundations are more relevant to the specific contextual change than others is consistent with the correlational findings showing that endorsement of the in-group and fairness foundations correlates more strongly with prejudice scores both before and after 7/7 than does endorsement of the authority and harm foundations. The correlations between both measures of prejudice and endorsement of the in-group and fairness foundations (|r| range: .15–.19) were all significantly different from the correlations between both measures of prejudice and endorsement of the authority and harm foundations (|r| range: .01–.09), pairwise t(1934)s ≥ 2.50, ps < .01 (see the Supplemental Material). Future research should continue to develop the cross-connections between moral-foundations theory and motivated-social-cognition theory.

For people working to tackle prejudice, it is important to be aware that terror events may have different effects on the attitudes of people who start from different political orientations. Among people who tend to be conservative, such events may consolidate their existing priorities, making them resistant to change. Among people who tend to be liberal, the same events may prompt a shift in their priorities and propel them toward more prejudiced attitudes. Therefore, different interventions may be required to tackle these responses.

For policy strategists who wish to strengthen national solidarity around shared values, it may be important to recognize the danger that national solidarity itself could promote in-group loyalty, which may result in population shifts toward prejudice rather than away from it. This risk arises from the shift from what Abrams (2010) termed harmonious cohesion to rivalrous cohesion that can follow intergroup conflict (Abrams & Vasiljevic, 2014; cf. Sherif, 1966).

We are aware of the limitations of the present research. The use of matched rather than longitudinal samples means that we can examine change at the level of societal attitudes rather than change in individual attitudes. It could be argued that our findings are due to a failure to replicate differences between liberals and conservatives after 7/7. Additional measurement points would also have provided insight into the time course and duration of changes. To overcome these limitations, we performed additional data analyses on data sets from British Social Attitudes Survey (BSAS) samples similar to those in our main analysis. The relevant BSAS data were collected in 2005 (beginning in August) and in 2008 (National Centre for Social Research, 2007, 2010). We expected that the differences between liberals and conservatives that appeared before 7/7 and that were diminished after 7/7 would reemerge and, in the absence of a repeat attack of similar magnitude, remain relatively stable. Our own data showed that the strength of association between political orientation and attitudes toward immigrants before 7/7, Cohen’s d = 0.39, r = .19, N = 931, was significantly reduced after 7/7, Cohen’s d = 0.18, r = .09, N = 1,100. Analyses of the BSAS data demonstrated that, as expected, the association between political orientation and attitudes toward immigrants had strengthened again later in 2005, Cohen’s d = 0.39, r = .19, N = 289, and remained consistent in 2008, Cohen’s d = 0.39, r = .19, N = 2,072 (for further information, see the Supplemental Material).

In the current research, we used indirect measures (rather than direct matches) to tap into four of the five moral foundations. The different measures do clearly and distinctively map onto the in-group, harm, authority, and fairness foundations. Conceptually, therefore, they are informative about the relative importance of these different foundations. We are aware that the particular items may also tap other constructs that are not central to moral-foundations theory. However, the findings provide powerful society-level evidence that is in line with past experimental or opportunity sample research showing that, after contextual threats, liberals shift toward conservative positions (e.g., Nail et al., 2009; van der Toorn et al., 2014). Therefore, the present findings provide valuable insights into the larger societal implications and thus the real-world relevance of predictions from moral-foundations theory and motivated-social-cognition theory. Moreover, pursuing the measurement issues and potential limitations offers interesting avenues for future research into the impact of terrorist events.

The present findings provide a rare example of substantial psychological data from a survey containing relevant measures administered before and after a major terrorist event, allowing us to examine the impact on the national population. Furthermore, the data were collected by an independent organization that had no insight into our hypotheses or interest in the responses and that used extremely rigorous methodology. Thus, we have considerable confidence in the quality and interpretability of the data.

The post-7/7 evidence has not been available for publication until now. However, the 7/7 attack remains highly salient in the United Kingdom, which held 10th-anniversary commemorations in July 2015. Sadly, besides the Charlie Hebdo attack that stunned Paris in January, there have been nearly 300 terror attacks around the world in 2015. In the 4 months during which this article was being revised and finalized, there were 12 major terror attacks, each with more than 50 fatalities, including attacks in Ankara (Turkey), Beirut (Lebanon), Kabul (Afghanistan), Kahn Bani Saad (Iraq), Kukawa (Nigeria), Paris (France), and Sinai (Egypt). These have often been followed by strong political responses from governments and, in some cases, by military responses. Understanding the psychological responses to these events, and their potential effects in facilitating or constraining retaliatory or defensive political reactions, is an important avenue for future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Age UK, the United Kingdom Equality and Human Rights Commission, NatCen Social Research, Amy Cuddy, Susan Fiske, and colleagues at the Centre for the Study of Group Processes for contributions to discussions and consultation in the preparation for the research.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest with respect to their authorship or the publication of this article.

Funding: This work was supported by the Women and Equality Unit, People United (http://www.peopleunited.org.uk), and the United Kingdom Economic and Social Research Council (Grant ES/J500148/1).

Supplemental Material: Additional supporting information can be found at http://pss.sagepub.com/content/by/supplemental-data

References

- Abrams D. (2010). Processes of prejudice: Theory, evidence and intervention (Equalities and Human Rights Commission Research Report 56). Retrieved from http://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/documents/research/56_processes_of_prejudice.pdf

- Abrams D., Houston D. M. (2006). Equality, diversity and prejudice in Britain: Results from the 2005 national survey (Report for the Cabinet Office Equalities Review). Retrieved from http://kar.kent.ac.uk/4106/1/Abrams_KentEquality_Oct_2006.pdf

- Abrams D., Vasiljevic M. (2014). How does macroeconomic change affect social identity (and vice versa?): Insights from the European context. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 14, 311–338. doi: 10.1111/asap.12052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett J. F., Van Tongeren D. R., Green J. D., Sonntag M. E., Kilpatrick H. (2015). The interactive effects of mortality salience and political orientation on moral judgments. British Journal of Social Psychology, 54, 306–323. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno G. A., Jost J. T. (2006). Conservative shift among high-exposure survivors of the September 11 th terrorist attacks. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 28, 311–323. doi: 10.1207/s15324834basp2804_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breton H. O. (2010). Feeling persecuted? The definitive role of paranoid anxiety in the constitution of “war on terror” television. In Brecher B., Devenney M., Winter A. (Eds.), Discourses and practices of terrorism: Interrogating terror (pp. 78–92). London, England: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Castano E., Leidner B., Bonacossa A., Nikkah J., Perrulli R., Spencer B., Humphrey N. (2011). Ideology, fear of death, and death anxiety. Political Psychology, 32, 601–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2011.00822.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke R. A. (2008). Against all enemies: Inside America’s war on terror. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Echebarria-Echabe A., Fernández-Guede E. (2006). Effects of terrorism on attitudes and ideological orientation. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36, 259–265. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.294 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman S., Stenner K. (1997). Perceived threat and authoritarianism. Political Psychology, 18, 741–770. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00077 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Florian V., Mikulincer M., Hirschberger G. (2001). An existentialist view on mortality salience effects: Personal hardiness, death-thought accessibility, and cultural worldview defence. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 437–453. doi: 10.1348/014466601164911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J., Haidt J., Nosek B. A. (2009). Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96, 1029–1046. doi: 10.1037/a0015141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg J., Jonas E. (2003). Psychological motives and political orientation—the left, the right, and the rigid: Comment on Jost et al. (2003). Psychological Bulletin, 129, 376–382. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J., Graham J. (2007). When morality opposes justice: Conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Social Justice Research, 20, 98–116. doi: 10.1007/s11211-007-0034-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J., Joseph C. (2004). Intuitive ethics: How innately prepared intuitions generate culturally variable virtues. Daedalus, 133(4), 55–66. doi: 10.1162/0011526042365555 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. F. (2013). An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington M. J., Weiler J. D. (2009). Authoritarianism and polarization in American politics. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ipsos MORI. (2015). Voting intentions in Great Britain: Recent trends. Retrieved from https://www.ipsos-mori.com/researchpublications/researcharchive/107/Voting-Intention-in-Great-Britain-Recent-Trends.aspx#2005

- Jost J. T., Glaser J., Kruglanski A. W., Sulloway F. J. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 339–375. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugler M., Jost J. T., Noorbaloochi S. (2014). Another look at moral foundations theory: Do authoritarianism and social dominance orientation explain liberal-conservative differences in “moral” intuitions? Social Justice Research, 27, 413–431. doi: 10.1007/s11211-014-0223-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landau M., Solomon S., Greenberg J., Cohen F., Pyszczynski T., Arndt J., . . . Ogilvie D. M. (2004). Deliver us from evil: The effects of mortality salience and reminders of 9/11 on support for President George W. Bush. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1136–1150. doi: 10.1177/0146167204267988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor I., Nail P. R., Marigold D. C., Kang S.-J. (2005). Defensive pride and consensus: Strength in imaginary numbers after self-threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 978–996. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor I., Zanna M. P., Holmes J. G., Spencer S. J. (2001). Compensatory conviction in the face of personal uncertainty: Going to extremes and being oneself. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 472–488. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.3.472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nail P. R., McGregor I., Drinkwater A., Steele G., Thompson A. (2009). Threat causes liberals to think like conservatives. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.04.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Centre for Social Research. (2007). British Social Attitudes Survey, 2005 [Data set]. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-5618-1

- National Centre for Social Research. (2010). British Social Attitudes Survey, 2008 [Data set]. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-6390-1

- Schwartz S. H. (2003). A proposal for measuring value orientations across nations. In Questionnaire development report of the European Social Survey (pp. 259–319). Retrieved from https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/docs/methodology/core_ess_questionnaire/ESS_core_questionnaire_human_values.pdf

- Sherif M. (1966). Group conflict and co-operation: Their social psychology. London, England: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich J., Cohrs C. (2007). Terrorism salience increases system justification: Experimental evidence. Social Justice Research, 20, 117–139. doi: 10.1007/s11211-007-0035-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van der Toorn J., Nail P. R., Liviatan I., Jost J. T. (2014). My country, right or wrong: Does activating system justification motivation eliminate the liberal-conservative gap in patriotism? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 54, 50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2014.04.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen F., Park J. H. (2009). Perceptions of social dangers, moral foundations, and political orientation. Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.02.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.