Abstract

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, in partnership with Oak Ridge Associated Universities, designed an online social marketing strategy tool, MessageWorks, to help health communicators effectively formulate messages aimed at changing health behaviors and evaluate message tactics and audience characteristics. MessageWorks is based on the advisor for risk communication model that identifies 10 variables that can be used to predict target audience intentions to comply with health recommendations. This article discusses the value of the MessageWorks tool to health communicators and to the field of social marketing by (1) describing the scientific evidence supporting use of MessageWorks to improve health communication practice and (2) summarizing how to use MessageWorks and interpret the results it produces.

Keywords: audience-centered messaging, innovation

Background

Messaging strategies are an essential component of social marketing and strategic communication frameworks. Social marketers are directed to create effective messages by considering their communication goals and their intended audience’s preferences (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2006; National Cancer Institute, 2004). However, audience-centered messaging guidance is limited and practitioners struggle to incorporate communication and behavioral theories into messages that help audiences initiate and sustain behavior change (Macstravic, 2000; Mattson & Basu, 2010; Peattie & Peattie, 2003; Wallack, 1994; Wallack & Dorfman, 1996; Wisner, 1987).

The CDC’s Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, in partnership with Oak Ridge Associated Universities, has designed an online social marketing strategy tool, MessageWorks, to help health communicators effectively formulate messages aimed at changing health behaviors and evaluate message tactics and audience characteristics. MessageWorks (https://cdc.orau.gov/healthcommworks) is publicly available and provides a means of improving the effectiveness of messages as they are being developed.

This article discusses the value of the MessageWorks tool to health communicators and to the field of social marketing by (1) describing the scientific evidence supporting use of MessageWorks to improve health communication practice and (2) summarizing how to use MessageWorks and interpret the results it produces.

Evidence to Support Using MessageWorks to Improve Health Communication

MessageWorks is based on the advisor for risk communication (ARC) model developed by Keller and Lehmann (2008), which offers an evidence-based approach to audience-centered messaging. The ARC model was developed from a meta-analysis of 60 studies on health behaviors, representing 22,500 participants. ARC identifies 10 variables—4 audience characteristics and 6 message tactics—that predict whether target audiences state they will comply with health recommendations “stated health intentions”. Table 1 includes a list of the 10 significant variables from the ARC model, a description of each, and corresponding recommendations for message development based on associations with higher intentions to change behavior.

Table 1.

Ten Variables From the Advisor for Risk Communication Model (Keller & Lehmann, 2008)—Definitions and Message Development Recommendations.

| Ten Variables | Description | Message Development Recommendations (Due to Associations With Higher Intentions to Change Behavior) |

|---|---|---|

| Audience characteristics | ||

| Age | The average age of your target audience |

|

| Gender | The percentage of your target audience that is male and female |

|

| Race | The percentage of your target audience that is “White” or “non-White” |

|

| Regulatory focus | A psychological variable that explains how individuals may prefer to meet promotion goals (e.g., growth and accomplishment) or prevention goals (e.g., safety and security) |

|

| Message tactics | ||

| Health goals | The health message targets a detection, prevention, or treatment behavior and discourages unhealthy behavior or encourages healthy behavior |

|

| Framing | The consequences of engaging in a behavior are described as a gain or loss |

|

| Consequences | The costs to the target audience or others of engaging/not engaging in a healthy behavior are described as physical or social |

|

| Referencing | The consequences of engaging/not engaging in a healthy behavior are focused on the self or others |

|

| Emotion | The mental or physiological reactions or feelings evoked by a message that may be negative (e.g., worry, fear, and guilt) or positive (e.g., relief, joy, and hope) |

|

| Vividness | The degree to which elements of the message portray the target behavior or the consequences of engaging/not engaging in the target behavior using pictures, concrete information, and examples of specific cases or stories |

|

The ARC model produces a numerical estimated intentions score that predicts whether a specific audience intends to comply with health recommendations based on the message tactics used. Social marketers can develop effective communications by using the combination of message tactics that will result in the highest estimated intentions score for their chosen target audience. They can also compare the estimated intentions scores of a message across several audiences, to select the target audience for whom their message will have the greatest impact.

Because intention does not directly relate to actual behavior, the ARC model also provides an estimated behavior score. Recalibration is required to convert intentions into predicted behavior (Jamieson & Bass, 1989; Kalwani & Silk, 1983). A useful approximation is related to the square of intentions. Specifically, behavior = 0.5 (intentions)2. The estimated behavior score allows social marketers to estimate the percentage of a target audience expected to change their behavior when they read, watch, or hear a message. By incorporating the recommended combinations of audience characteristics and message tactics deemed most effective by the ARC model, MessageWorks provides an evidence-based approach to craft, predict, and defend tailored health communications for different target audiences.

The behavior estimate is likely to be on the high side, because the formula is based on data obtained from consumer durable goods (and health behaviors are more challenging than consumer purchases). In addition, other elements of the marketing mix such as price and accessibility can undermine the conversion of intentions to behavior. Gaps between actual and predicted behavior scores may reflect the role of the noncommunication elements of the marketing mix such as pricing/cost, product ease of use, and accessibility.

How to Use the MessageWorks Tool and Interpret Its Findings

Using MessageWorks, health communicators can:

craft effective messages using the six message tactics most likely to influence the behavior of a specific audience or

identify the four characteristics of a target audience most likely to change their behavior when they read, watch, or hear an existing message.

MessageWorks is accessible online (https://cdc.orau.gov/healthcommworks) and users can register for a free account. Users can access information from previous sessions each time they log into their account. Upon entry into the tool, users may choose to (Figure 1):

craft a new message or

assess an existing message.

Figure 1.

“Craft a new message” or “assess an existing message.”

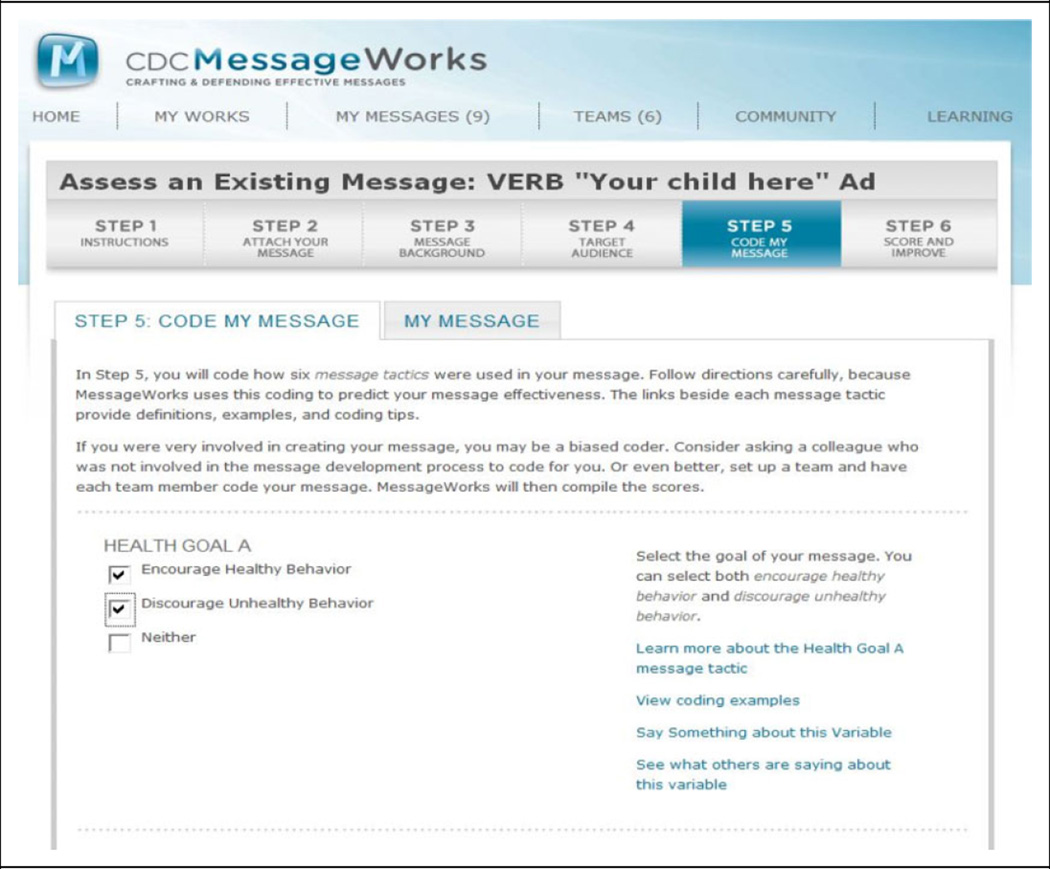

Users are guided through a step-by-step process to input information needed to apply the ARC model (Figure 2). The steps required to “craft a new message” and “assess an existing message” are summarized in this section (Table 2). Also, an example of how to apply MessageWorks is provided.

Figure 2.

The six steps of “assess an existing message.”

Table 2.

Description of the MessageWorks Step-by-Step Processes to “Craft a New Message” or “Assess an Existing Message.”a

| Craft a New Message |

|---|

| Step 1: Instructions |

| Learn how to use MessageWorks to create an effective message based on your target audience |

| Step 2: Message background |

| Add key information from a health communication or social marketing plan |

| Step 3: Target audience |

| Define target audience by inputting data based on the four audience characteristics from the advisor for risk communication model |

| Step 4: Message recommendations |

| Receive recommendations for the six best message tactics to incorporate to most effectively reach the defined target audience |

| Step 5: Attach or draft my message |

| Make a message available to view in MessageWorks by uploading an attachment or copying and pasting directly into a text box. |

| Step 6: Code my message |

| Code use of six message tactics so that MessageWorks can calculate an estimated intentions score |

| Step 7: Score and improve |

| Review the estimated intentions score and determine whether or not to improve. If users chose to improve a message, they can return to Step 3 to input different audience characteristics or Step 6 to recode their message tactics to receive a new score |

Assess an existing message contains all steps except for Step 4: message recommendations.

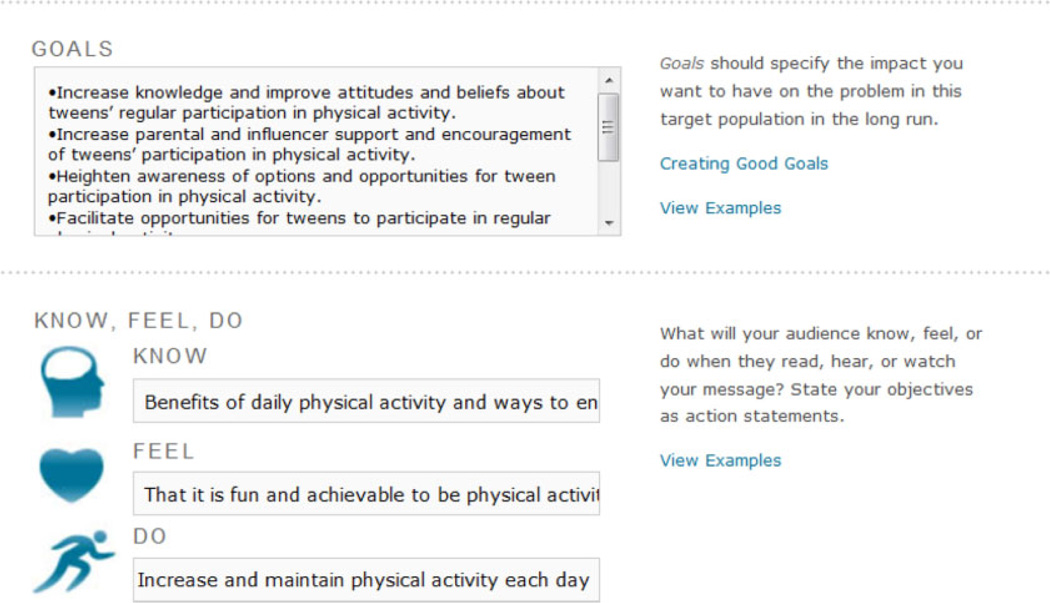

Message Background

MessageWorks prompts users to input the health problem, goals and objectives, target audience, vulnerabilities and barriers, and dissemination strategies for their communication campaign. Users are asked to enter their message goals and objectives in terms of quantifiable changes in audience knowledge, behavior, and attitude (i.e., what should your audience know, feel, and do) depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Message background—goals.

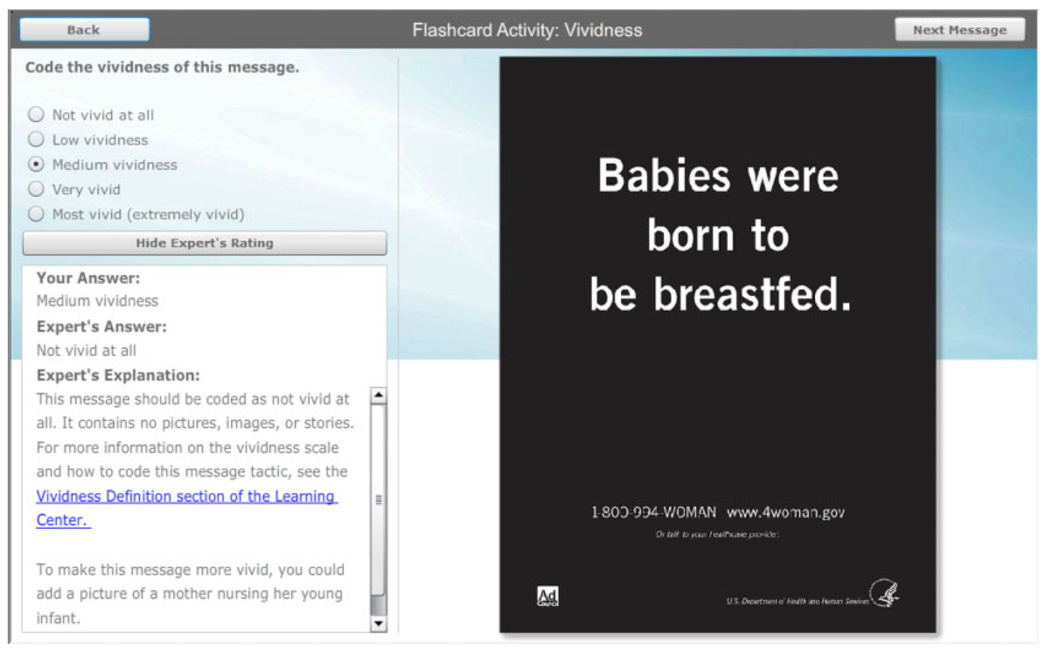

Message Coding

To receive an “estimated intentions score” for a message, users must describe or code their use of 10 variables (Table 1). MessageWorks provides guidance on coding messages accurately with interactive instructions (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Interactive instructions.

Score and Improve a Message

For each coded message, users receive an estimated intentions score. This score can provide feedback on a messages’ effectiveness prior to conducting costly audience testing. The estimated intentions score helps a user learn to what extent the model finds the target audience an appropriate match for the message tactics or to what extent the message tactics are deemed a match for the target audience. The user receives specific suggestions on how to revise a message to receive the “best possible score” based on changing either the six message tactics or the four audience characteristics. MessageWorks allows users the ability to recode a message to produce a new score rather than starting at the beginning of the tool.

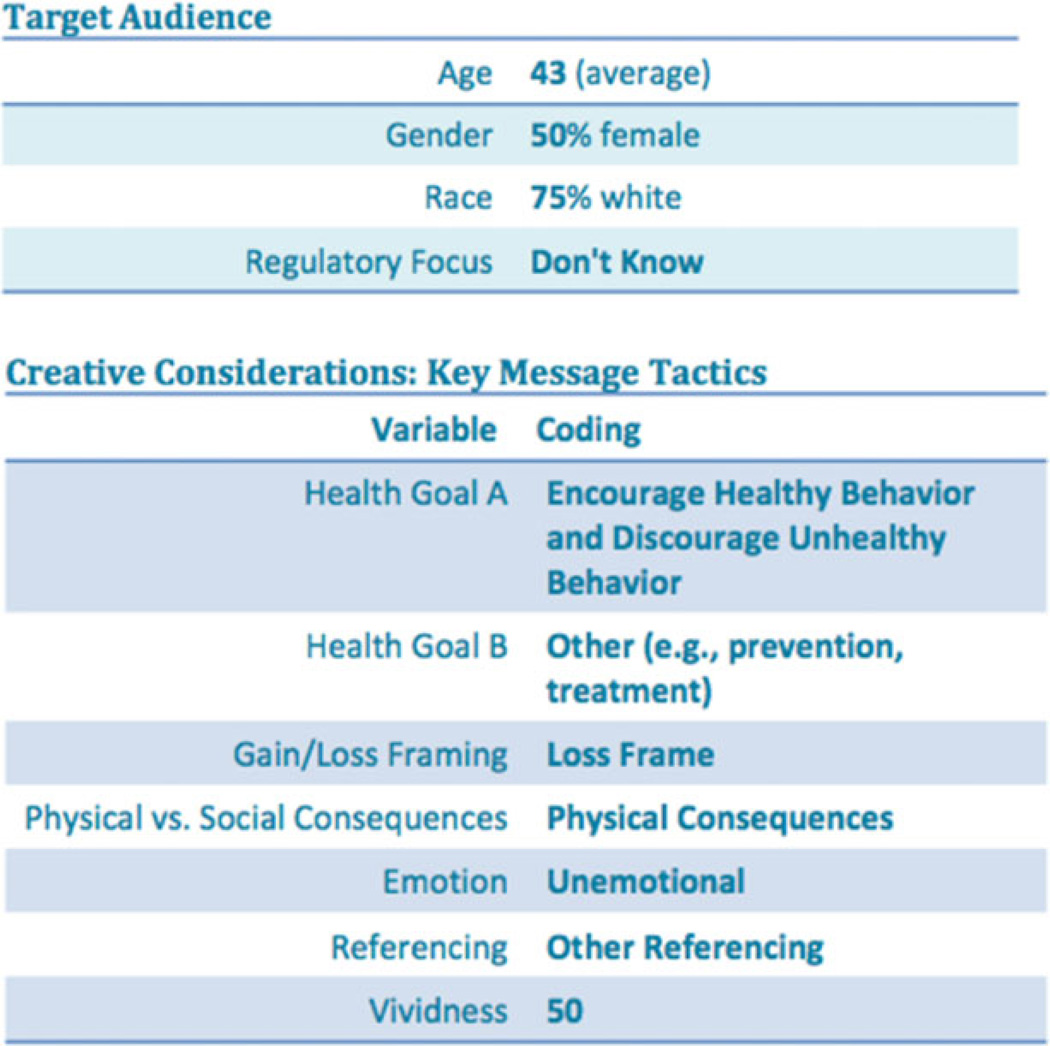

Application of MessageWorks to a CDC Campaign Advertisement

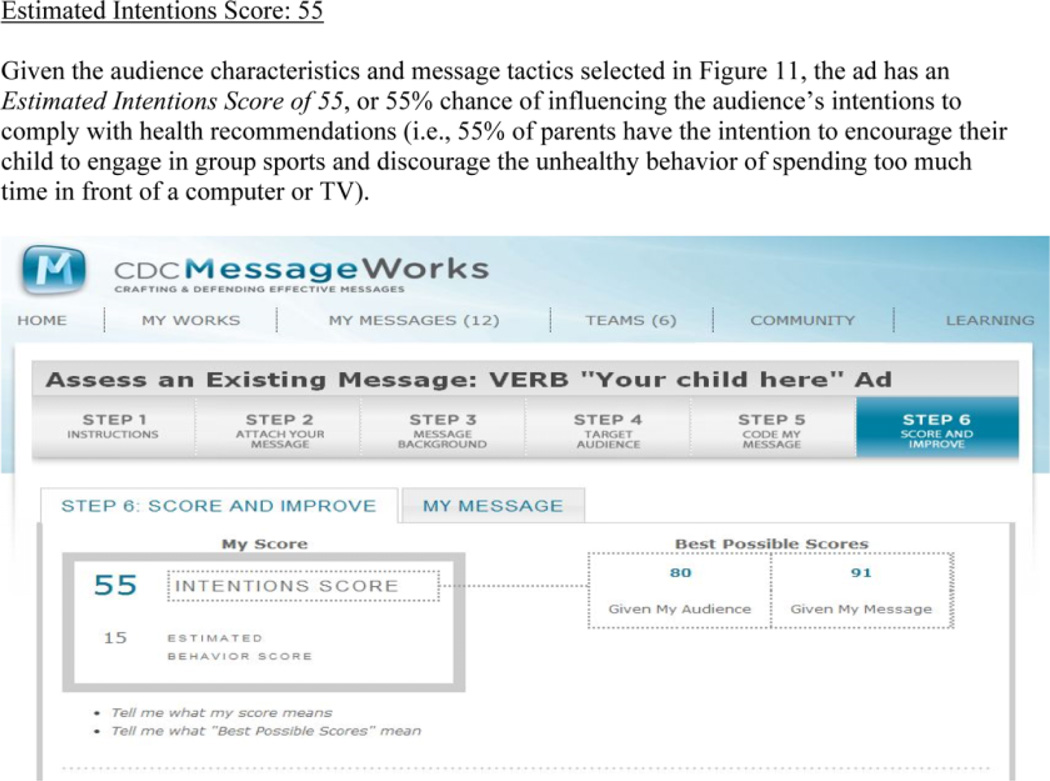

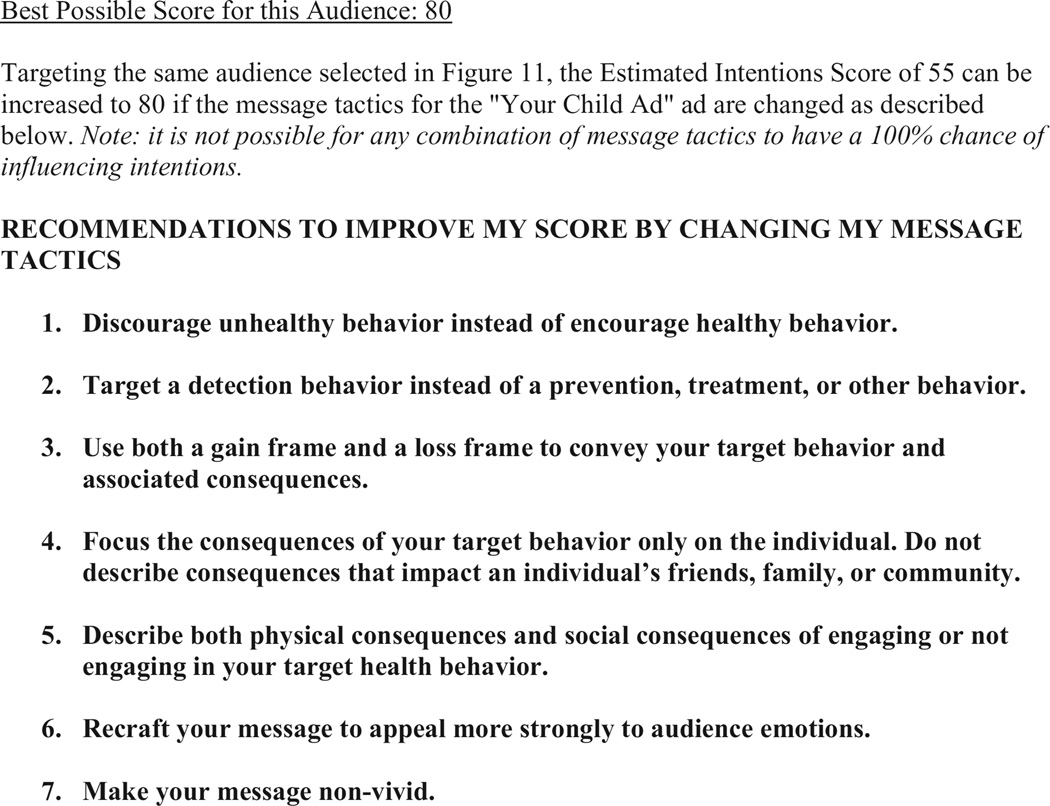

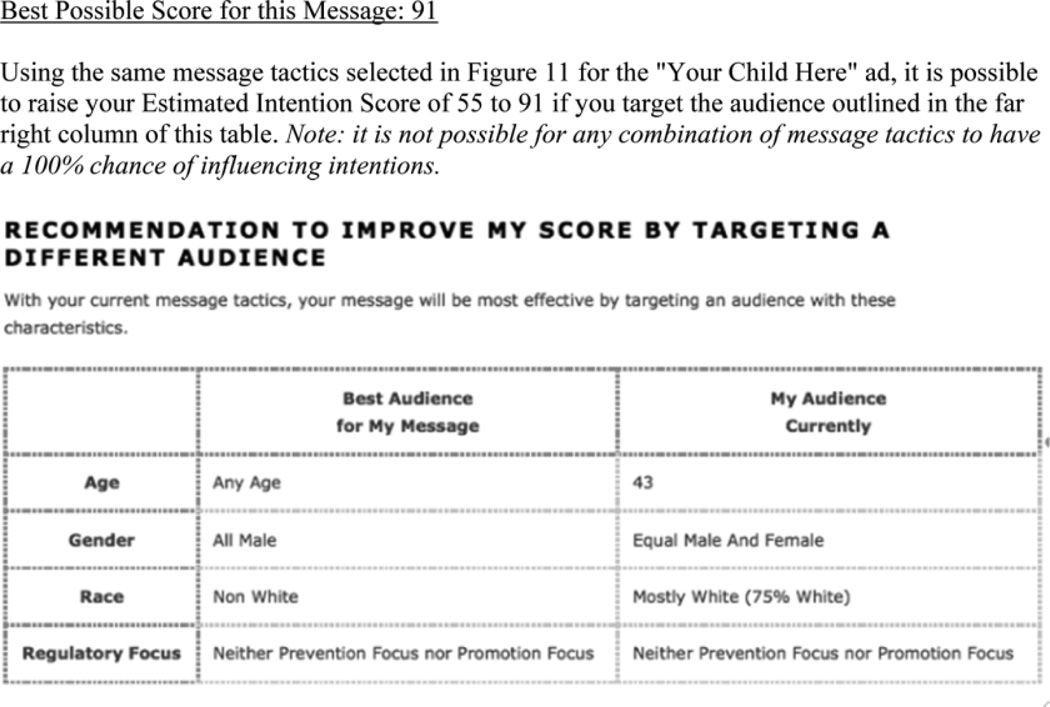

To demonstrate MessageWorks coding and scoring functionality, we will assess an existing message from CDC’s 2010 VERB campaign titled “your child here” (Figure 5). Audience characteristics and message tactics for the Your Child Here advertisement were coded (Figure 6) to produce an estimated intentions score (Figure 7). MessageWorks provides recommendations for how to improve this score by either changing the message tactics or finding the best target audience for the existing message (Figures 8 and 9).

Figure 5.

“Your child here” advertisement.

Figure 6.

MessageWorks coding summarized for “your child here” ad.

Figure 7.

MessageWorks scores for “your child here” ad.

Figure 8.

VERB campaign scenario: I cannot change the audience. How can I improve the “your child here” ad by changing the message tactics?

Figure 9.

VERB campaign scenario: I cannot change the “your child here” ad. How can I find the best target audience for this ad?

Value to Social Marketing

MessageWorks is a health communication tool that can be used to promote tangible health products such as condoms and sunscreen as well as intangible health services such as HIV/AIDS diagnostic testing and exercising. The product and service examples listed above contributed to the data used to develop the MessageWorks algorithm (Keller & Lehmann, 2008).

MessageWorks provides the following benefits to health communicators and social marketers.

- Communicators can use MessageWorks to:

-

◦Predict the effectiveness of a message. MessageWorks provides research-based recommendations for using message tactics that are most likely to persuade a target audience to change its health behavior.

-

◦Find the best audience for a message. MessageWorks identifies the target audience most likely to be persuaded by the message tactics currently being used in your message.

-

◦Pick the most effective message from a set of messages. MessageWorks provides message developers with evidence-based and unbiased data needed to decide which message will be most effective for reaching a target audience.

-

◦

Messages can be pretested by MessageWorks before they are tested by audiences. Using MessageWorks can improve the efficiency of implementing a social marketing plan by minimizing the number of iterative cycles of planning, message development, audience pretesting, and revision of messages and message tactics. Improved efficiency results in the elimination of costly audience testing rounds.

Social marketers can compare the effect of a health message versus the effect of other elements of the social marketing mix. In general, all elements of the social marketing mix may determine intentions to comply with health messages and actual behavior changes. A comparison of the intention and behavior scores from MessageWorks with surveyed intentions and behavior change metrics will indicate the effect of the health message versus the effect of the other elements of the social marketing mix, such as free product distribution.

Communicators and social marketers can be trained in evidence-based “best practices” of message development. Application of the ARC model through MessageWorks allows a communicator to follow a formula for effective message development. By using the tool, social marketers and communicators can learn tactics of developing a successful message that is grounded in an evidence-based approach. They can bring their emerging understanding of message development to better decide what to ask audiences during testing and how to analyze and interpret audience feedback. The educational aspect of MessageWorks can prepare student and professional health communicators to become thought leaders of message development.

The availability of effective messages and those tailored for different audiences could increase. MessageWorks has the potential to advance the field of health communication by widening the availability of messages that promote behavior change (that score highly on intention to change behavior measures) for a variety of audiences. Use of this accessible tool could assist communicators in developing materials for diverse populations and audiences with characteristics considered hard to reach, particularly for message developers with few resources to conduct extensive formative research.

Scientific Validation

To validate MessageWorks’ ability to predict the effectiveness of tailored health communications for different target audiences, MessageWorks’ data were compared to survey data collected from a popular health communication campaign. The CDC’s 2004–2006 VERB campaign focused on increasing and maintaining physical activity among children aged 9–13 years. VERB employed a broad mix of campaign tactics to reach children and their parents. Television advertising, placed mainly on cable networks popular with children, was the primary delivery vehicle for the intervention. A total of nine TV advertisements were created and aired (four ads aired in 2004, three new ads and one previously shown ad were aired in 2005, and two new ads were aired in 2006). A comprehensive evaluation of the VERB campaign was undertaken in a longitudinal survey (Berkowitz et al., 2008).

Method

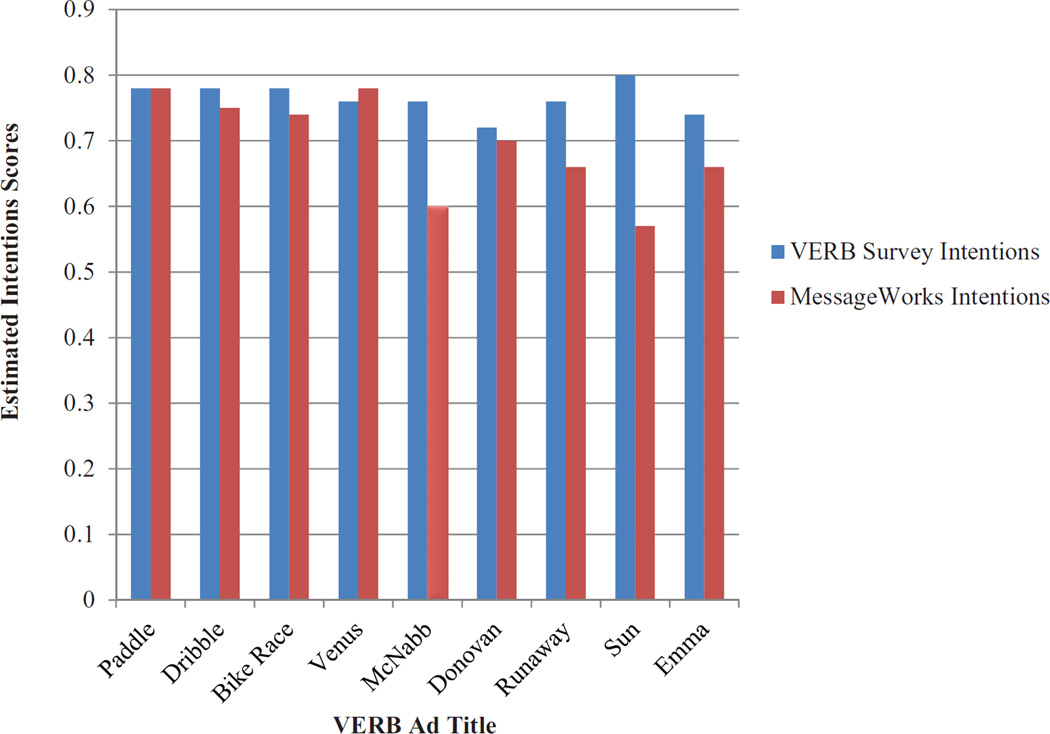

A trained research assistant used MessageWorks to code the message tactics (Table 1) used in the nine VERB TV ads. MessageWorks then computed intention and behavior scores. VERB survey data of self-reported intention and behavior was analyzed to create intention and behavior scores for audience segments who watched between 1–4 ads each year. MessageWorks scores and VERB survey data intention and behavior scores were plotted against each other (see Figure 10).

Figure 10.

VERB survey and MessageWorks intention estimates for the nine VERB campaign advertisements.

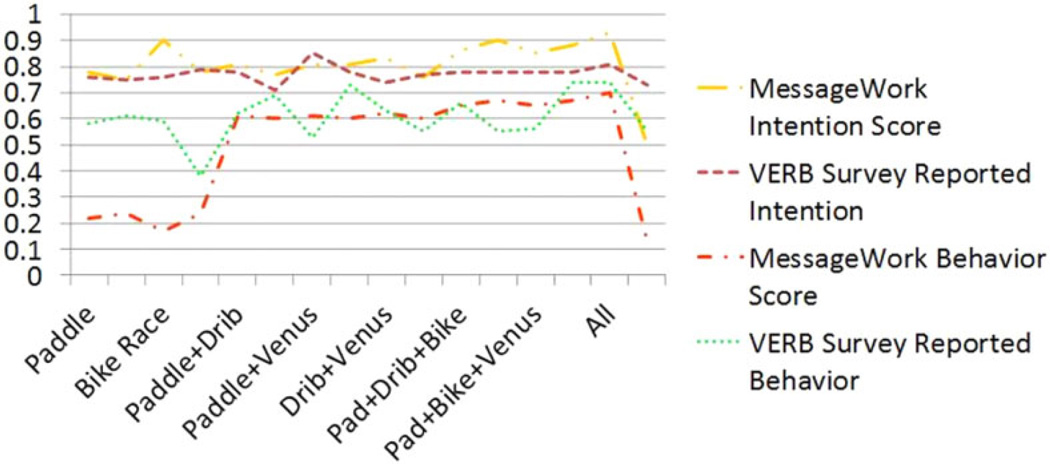

Since multiple advertisements were aired in the same period, MessageWorks’ scores for single and combinations of advertisements were also computed. An average MessageWorks score (sum of MessageWorks scores/number of ads) was calculated for the combination of ads for each year. Figure 11 indicates the MessageWorks intention and behavior scores for 2004.

Figure 11.

Sample cluster membership and intention and behavior MessageWorks estimates in year 2004.

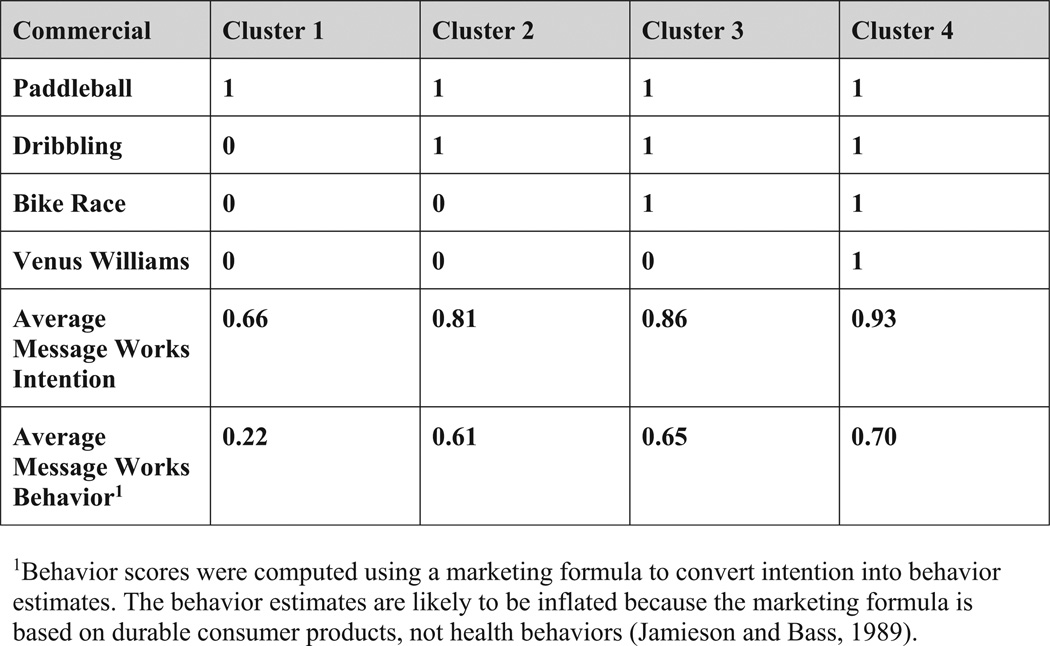

A K-means cluster analysis was performed on the VERB survey data to classify children into segments with all possible combinations of ad exposures for each year (2004–2006). The cluster analysis was based on VERB survey data indicating the number of ads each survey participant stated they viewed. To ensure reliability, MessageWorks scores were only computed for ad combinations viewed by at least 10 children. Table 3 shows the number of possible ad combination exposures viewed by groups.

Table 3.

Number of Possible Ad Combination Exposures Viewed by Groups.

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of ads aired | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Number of ad combinations | 16 | 16 | 4 |

| Number of ad combinations (n > 10) | 16 | 10 | 4 |

| Sample size | 2,256 | 1,946 | 1,623 |

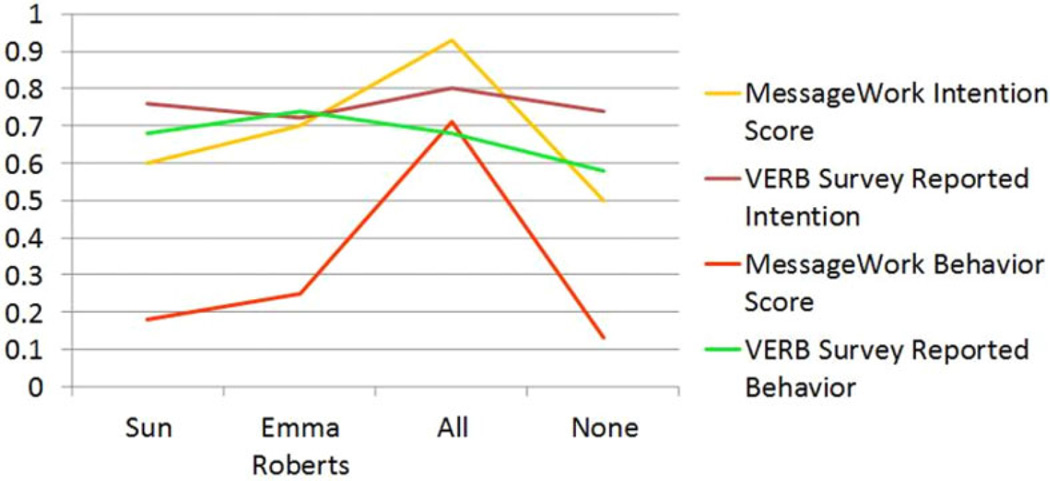

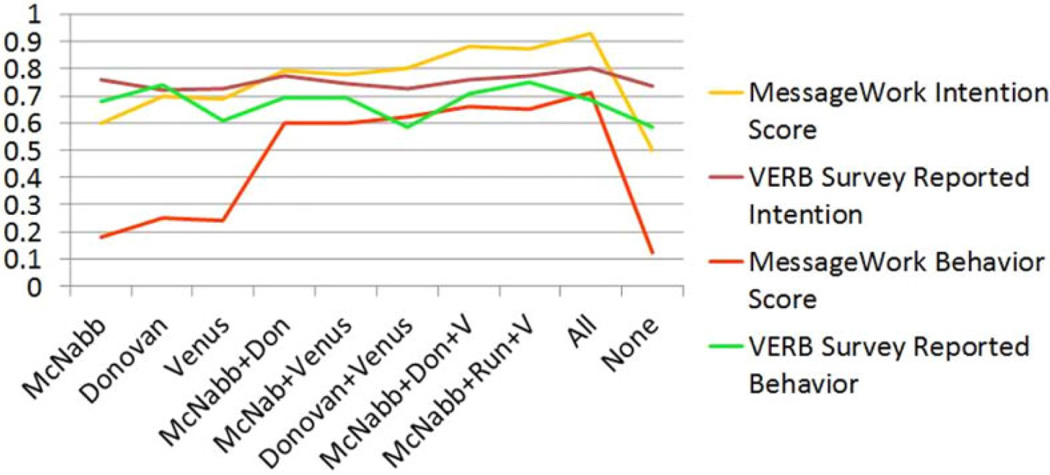

A VERB survey intention and behavior score was computed for each cluster (e.g., simple average for the group of children who remembered viewing the Paddle and Dribble ads). Figures 12–14 indicate the MessageWorks and VERB survey intention and behavior scores for each combination of VERB advertisements in 2004, 2005, and 2006, respectively.

Figure 12.

MessageWorks and VERB survey intention and behavior estimates among tweens who claimed to have seen one or more VERB ads in years 2004–2006: Group 1 of ads.

Figure 14.

MessageWorks and VERB survey intention and behavior estimates among tweens who claimed to have seen one or more VERB ads in years 2004–2006: Group 3 of ads.

Results

MessageWorks accurately predicted intentions to exercise among children exposed to TV advertisements when compared to intention data collected in a longitudinal survey. MessageWorks came within 0.10 of predicting intention scores for each of the nine advertisements in the VERB campaign. For half the advertisements, MessageWorks intention scores were 0.05 or less than the intention scores provided in the VERB evaluation survey (Berkowitz et al., 2008).

Discussion

This application demonstrates the value of MessageWorks for predicting target population intentions for multi-advertisement health campaigns. The results indicate impressive overlaps between Message-Works intention and behavior scores and the same measures obtained from the VERB survey. Specifically, different combinations of advertisements produced similar MessageWorks and VERB intention scores.

This validation study demonstrates that MessageWorks is more effective for predicting health intentions than health behavior. This result is not surprising because intentions constitute the bulk of the empirical evidence used for developing the MessageWorks algorithm. In addition, behavior increases substantially at high levels of intention. However, the formula for converting intentions to behavior [behavior = 0.5 (intentions)2] should be used cautiously for health behaviors since it is based on consumer products data (Jamieson & Bass, 1989).

Conclusion

The MessageWorks tool provides an evidence-based approach to craft, predict, and defend tailored health communications for different target audiences. MessageWorks incorporates recommended combinations of audience characteristics and message tactics deemed effective by the ARC model. Estimated intention and behavior scores from MessageWorks were compared to self-reported intention and behavior data collected from CDC’s VERB campaign as a first step in validating the ARC model and MessageWorks’ effectiveness in predicting which message appeals and tactics are likely to affect an audience’s compliance with health recommendations. The use of MessageWorks streamlines the message development process by helping its users predict the effectiveness of a message, find the best audience for a message, and identify the most appropriate message from a set of messages. Message-Works allows health communicators and social marketers to pretest messages before they are tested by audiences, and learn evidence-based “best practices” of message development. The adoption of MessageWorks by communicators could potentially widen the availability of evidence-based, audience-centered messages in the field that promote behavior change.

Figure 13.

MessageWorks and VERB survey intention and behavior estimates among tweens who claimed to have seen one or more VERB ads in years 2004–2006: Group 2 of ads.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following individuals for contributing their expertise to the development of the MessageWorks tool. MessageWorks Expert Panel Members are in alphabetical order: Jodie Abbatangelo Gray, ScD, MA, MS, Summit Research Associates NYC; Jill Bartholomew, MS, MBA, National Institutes of Health; Cynthia Baur, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Kelly Burke, KELCOM Media Services; Galen Cole, PhD, MPH, LPC, American Institutes for Research; Dogan Eroglu, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Fred Fridinger, DrPH, CHES, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Kelly Holton, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Mary Frances Luce, PhD, Fuqua School of Business, Duke University; Punam Keller, MBA, PhD, Tuck School of Business, Dartmouth University; Susan D. Kirby, DrPH, MPH, Kirby Marketing Solutions (Facilitator); Dave Mason, Multiple, Inc.; Elizabeth W. Mitchell, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Barbara D. Powe, PhD, RN, Director, Cancer Communication Science; American Cancer Society; Lisa Richardson, MD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Dick Tardif, PhD, Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education; Skot Waldron, Multiple, Inc.; Michael Wilkes, MD, PhD, School of Medicine University of California, Davis.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Biography

Galen E. Cole, PhD, MPH, LPC, WCPC, is a Senior Scientist for Mental Health at the American Institutes for Research. At the time he conceptualized and directed the development of Message Works he was the Associate Director for Communication Science, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

When Dr. Cole led the development of MessageWorks, he was serving as the associate director for communication science, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the American Institutes for Research or Oak Ridge Associated Universities.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Berkowitz JM, Huhman M, Heitzler CD, Ptter LD, Nolin MJ, Banspach WE. Overview of formative, process, and outcome evaluation methods used in the VERB campaign. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;34:S222–S229. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Retrieved March 18, 2011];CDCynergy health marketing. 2006 from the CDC Web site http://www.cdc.gov/healthmarketing/cdcynergy/

- Jamieson LF, Bass FM. Adjusting stated intention measures to predict trial purchase of new products: A comparison of models and methods. Journal of Marketing Research. 1989;26:336–345. [Google Scholar]

- Kalwani M, Silk AJ. On the reliability and predictive validity of purchase intention measures. Marketing Science. 1983;1:243–286. [Google Scholar]

- Keller PA, Lehmann DR. Designing effective health communications: A meta-analysis. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing. 2008;27:117–130. [Google Scholar]

- MacStravic S. The missing links in social marketing. Journal of Health Communication. 2000;5:255–263. doi: 10.1080/10810730050131424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson M, Basu A. The message development tool: A case for effective operationalization of messaging in social marketing practice. Health Marketing Quarterly. 2010;27:275–290. doi: 10.1080/07359683.2010.495305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. [Retrieved May 1, 2011];Making health communications programs work. 2004 from the NCI Web site http://www.cancer.gov/pinkbook.

- Peattie S, Peattie K. Ready to fly solo? Reducing social marketing’s dependence on commercial marketing theory. Marketing Theory. 2003;3:365–385. [Google Scholar]

- Wallack L. Media advocacy: A strategy for empowering people and communities. Journal of Public Health Policy. 1994;15:420–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallack L, Dorfman L. Media advocacy: A strategy for advancing policy and promoting health. Health Education Quarterly. 1996;23:293–317. doi: 10.1177/109019819602300303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisner B. Doubts about social marketing. Health Policy and Planning. 1987;2:178–179. [Google Scholar]