Abstract

Background

To identify indications for staging laparoscopy (SL) in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer, and suggest a pre-operative algorithm for staging these patients.

Methods

Relevant articles were reviewed from the published literature using the Medline database. The search was performed using the keywords ‘pancreatic cancer’, ‘resectability’, ‘staging’, ‘laparoscopy’, and ‘Whipple's procedure’.

Results

Twenty four studies were identified which fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Of the published data, the most reliable surrogate markers for selecting patients for SL to predict unresectability in patients with CT defined resectable pancreatic cancer were CA 19.9 and tumour size. Although there are studies suggesting a role for tumour location, CEA levels, and clinical findings such as weight loss and jaundice, there is currently not enough evidence for these variables to predict resectability. Based on the current data, patients with a CT suggestive of resectable disease and (1) CA 19.9 ≥150 U/mL; or (2) tumour size >3 cm should be considered for SL.

Conclusion

The role of laparoscopy in the staging of pancreatic cancer patients remains controversial. Potential predictors of unresectability to select patients for SL include CA 19.9 levels and tumour size.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is associated with a poor prognosis, with 5-year survival rates of only 10% following resection with curative intent.1, 2, 3, 4 Surgery is offered to patients without evidence of locally advanced or metastatic disease, which accounts for only 15–20% of patients at diagnosis. Accurate staging is essential for treatment planning, and high-resolution, contrast-enhanced spiral computed tomography (CT) is the mainstay in determining resectability,5 being able to predict resectability in >75% of patients.6 Despite this, a proportion of patients have occult metastatic disease, where hepatic or peritoneal metastases are not identified.7

Staging laparoscopy (SL) is a minimally invasive modality for staging pancreatic cancer in patients at high-risk of unresectable disease despite CT evidence of resectable disease,6 and can identify occult metastases in 15–51% of cases.8 Some authors argue against using SL routinely, as the proportion of patients found to have metastatic disease at laparoscopy is decreasing due to the increased sensitivity of CT.6, 9, 10 Currently, there are no standard criteria for selecting patients who may benefit from SL as part of their pre-operative staging.

The aim of this review is to identify indications for SL in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer, and suggest a pre-operative algorithm for staging these patients.

Methods

An electronic search was performed of the Medline database for the period 2000–2014 using the MeSH headings: “pancreatic cancer” and “staging.” The search was limited to English language publications and human subjects. All titles and abstracts were reviewed, and appropriate papers further assessed. The reference sections of all papers deemed appropriate were further reviewed to identify papers missed on the primary search criteria.

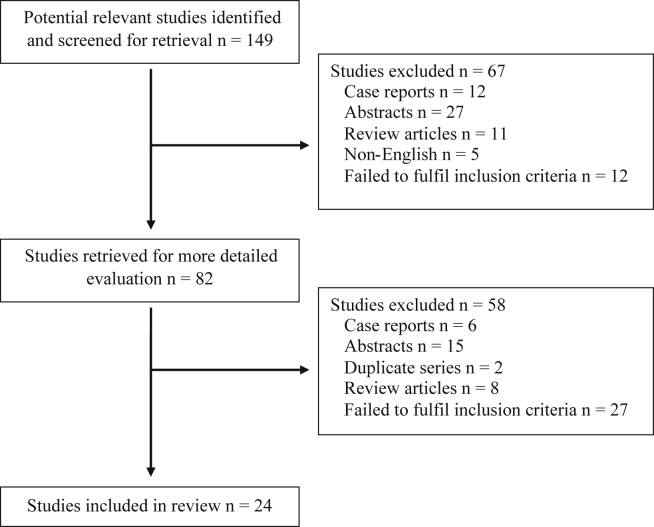

Studies were included if: (i) they investigated resectability in patients with pancreatic cancer; (ii) CT was used for pre-operative staging; (iii) studies investigated features suggestive of unresectable disease despite pre-operative staging suggestive of resectable disease; (iv) resectability was ultimately determined operatively (either laparotomy or laparoscopy); (v) a minimum of 20 patients were included; and (vi) data was published after 2000. Only studies published after 2000 were included as this coincides with the introduction of multi-detector CT (See Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Diagram demonstrating studies included in this review following the search criteria

Data collated included predictors of resectability, staging modalities used and outcomes at exploration. Case reports, editorials, abstracts and reviews were excluded.

Results

Tumour markers

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) are serum tumour markers used in the management of pancreatic cancer. Both tumour markers have limitations with respect to specificity, being elevated in other cancers and benign disease.11, 12 In addition, CA 19-9 is undetectable in 4–15% of the population with a Lewis negative (a–,b–) phenotype,13 and is increased in the presence of hyperbilirubinaemia, which makes interpretation in the presence of obstructive jaundice difficult.14, 15

Predictor of resectability

Several researchers have demonstrated a correlation between CA 19-9 levels and advanced disease,16, 17 and resectability.12, 18, 19

A study by Mehta et al. of 49 patients with resectable pancreatic cancer on CT, demonstrated that CA 19-9 and CEA levels of >3 times above the upper limit of normal had an increased risk of inoperability at laparotomy.20 More recently, Koenigsrainer and co-workers observed a significantly higher CA 19-9 level in pancreatic cancer patients (n = 29) with peritoneal carcinomatosis, compared to patients matched for clinico-pathological factors that had resectable disease (2,330 U/ml versus 387 U/ml; p = 0.041).21

Determination of a cut-off value for resectability

Numerous authors have attempted to determine a cut-off value for CA 19.9 and CEA as markers for advanced/metastatic disease in patients with a CT suggestive of resectable disease (Table 1). Such a cut-off value could be used to stratify patients according to risk of unresectable disease, and used as an indication for SL.

Table 1.

Published studies on CA 19.9 cut-off values to predict resectability. SL: Staging laparoscopy

| Study | n | CA 19.9 level | Type of surgery to determine resectability | Positive predictive value | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kilic et al. 2006 | 51 | 256.4 U/mL | Laparotomy | 91.4% | 82.4% | 92.3% |

| Schlieman et al. 2003 | 89 | 150 U/mL | Laparotomy | 88% | 71% | 68% |

| Zhang et al. 2008 | 104 | 353.15 U/mL | Laparotomy | 84.38% | 93.1% | 78.3% |

| Fujioka et al. 2007 | 244 | 157 U/ml | Laparotomy | – | 69.2% | 58.7% |

| Kim et al. 2009 | 72 | 92.77 U/mL | Laparotomy | – | 67.8% | 75.0% |

| Karachristos et al. 2005 | 63 | 100 U/ml | SL | – | 100% | 64% |

| Maithel et al. 2008 | 262 | 130 U/ml | SL | – | 50% | 74% |

| Connor et al. 2005 | 159 | 150 U/ml | SL | 95% | 44% | 88% |

| Halloran et al. 2008 | 164 | 150 U/ml | SL | 79% | 52% | 93% |

In a study by Kilic et al. of 51 patients with assumed resectable pancreatic cancer on CT, 33 patients had unresectable disease at laparotomy.22 The median CA 19-9 levels of these patients was 622 U/mL compared to 68.8 U/mL for patients with resectable disease. When a CA 19-9 level of 256.4 U/mL was used as a cut-off, the specificity and sensitivity was 92.3% and 82.4% respectively. In a similar study of 89 patients by Schlieman et al., the mean adjusted CA 19-9 levels were significantly lower for patients with resectable disease compared to patients with locally advanced (63 U/mL versus 592 U/mL; p = 0.003), or metastatic (63 U/mL versus 1387 U/mL; p < 0.001) disease. With a threshold adjusted CA 19-9 level of 150 U/mL, the positive predictive value for determining unresectable disease was 88%.23 Interestingly, the authors found no association between CEA levels and unresectability. Zhang et al., reported the median CA 19-9 levels in patients with unresectable disease was 5× higher when compared to patients with resectable disease (p < 0.01) in a study of 104 patients.24 When a cutoff value of 353.15 U/mL was used, the sensitivity and specificity were 93.1% and 78.3%, respectively.

Although the combined role of CEA and CA 19-9 levels for diagnosis and recurrence in pancreatic cancer have been previously investigated,25, 26, 27, 28 their combined role in determining resectability in patients with resectable disease on CT is less well defined. In a study by Fujioka et al., of 244 patients who underwent surgery for potentially resectable disease, a combined negative CEA and CA 19.9 predicted resectibility in 85%.19 They reported cut-off values for resectability of 157 U/ml and 5.5 ng/ml for CA 19-9 and CEA respectively. Similarly, Kim et al., in a study of 72 patients, of whom only 24 (33.3%) had completely resectable disease intra-operatively, calculated optimum cut-off values of CEA and CA 19.9 to predict resectability was 2.47 ng/mL and 92.77 U/mL, respectively.29

There is sufficient evidence demonstrating elevated CA 19.9 and CEA levels in the context of pancreatic cancer is suggestive of unresectable disease. The cut-off values used to predict unresectability varied from 92.77 to 353.15 U/mL for CA 19.9, and 2.47 to 5.5 ng/mL for CEA. ROC curve analysis was used to determine the cut-off values of CA 19.9 and CEA with the exception of Schlieman et al.23 The majority of studies addressed the effect of hyperbilibubinemia with a few exceptions.19, 20, 21 The groups of Schlieman and Kim adjusted tumour marker levels in the presence of hyperbilirubinemia (>2 mg/dL), by dividing the serum tumour marker level by the bilirubin level.12, 23, 29 However, other researchers did not adjusted tumour marker levels as they observed the mean total serum bilirubin level in patients with resectable and unresectable tumour were insignificant.22, 24 The studies reviewed, are limited by their retrospective nature, lack of randomisation and the small sample sizes, which, in some studies did not allow for a cut-off value to be determined.21

Tumour markers as predictors of laparoscopy findings

Of the previous studies described in this review, the potential yield of laparoscopy has been assessed indirectly at open surgery. This is likely to be inaccurate because although laparoscopy is sensitive in detecting small metastatic deposits (<3 mm) compared with laparotomy,30 it is less accurate in assessing vascular invasion, lymph node involvement,31 and intra-hepatic metastases. The studies below investigated the role of tumour markers in selecting patients for SL based on laparoscopy findings.

Karachristos et al. were the first to correlate CA 19.9 levels with SL findings32 in 63 patients with either resectable, or potentially resectable disease on CT. Patients with elevated CA 19.9 levels had a significantly higher incidence of metastatic disease at laparoscopy (p = 0.04). A CA 19.9 level of 100 U/ml as a cut-off would have increased the yield of SL in this series to 26.7%. Nevertheless, the cut-off value failed to predict resectability.

Ong and colleagues reported their series of 113 patients that underwent SL and intraoperative ultrasound, of which 55 (49%) patients were resectable and underwent resection, and the remaining 58 (51%) patients were unresectable.18 The unresectable group had a significantly higher median CA 19.9 than the resection group (p = 0.003), and an elevated CA 19.9 was found to be an independent risk factor for unresectable disease (p = 0.031).

Maithel and co-workers observed the median preoperative CA 19.9 for patients with unresectable disease at SL (n = 51) was 379 U/ml compared to 131 U/ml for patients who underwent resection (n = 211, p = 0.003).33 The optimal cut-off value of CA 19-9 as a predictor of unresectability was 130 U/ml (sensitivity 50%, specificity 74%). Using CA 19-9 level of >130 U/ml as a selection criterion would have avoided SL in 105 patients (50% of patients with resectable disease). Other authors have also shown similar results. Connor and colleagues observed a CA 19.9 level of ≤150 kU/L had a positive predictive value of 95% in predicting resectability at SL in a series of 159 patients.34 Using a cut-off CA 19.9 ≤150 kU/L, laparoscopy could have been avoided in 40% of patients, or 55% of patients when adjusted for jaundice. The yield from SL would have increased from 15% to 22% and 25%, respectively.

Halloran et al. reported their experience of 164 patients who were selected for SL with laparoscopic ultrasonography with a CA 19.9 level of >150 kU/l (or >300 kU/l in hyperbillirubinaemia).35 Fifty-five patients fulfilled the criteria and underwent SL, of which 37 patients underwent resection, 24 patients had bypass surgery, and nine (patients did not have surgery. The selective staging policy based on CA 19.9 levels avoided laparoscopy in 80 patients, and avoided a laparotomy in nine patients with advanced disease.

The cut-off value for CA 19-9 used to predict unresectability at laparoscopy ranged between 130 and 353.15 U/mL. A cut-off value of 100 U/mL was suggested by Karachristos, although it failed to predict resectability.32 All studies adjusted for hyperbilirubinemia, except one, as the authors found the median total serum bilirubin levels in patients with resectable and unresectable tumours to be insignificant.33 Although the above studies were based on reasonable sample sizes (n = 63–262), sufficient to calculate cut-off values, they do have their limitations with respect to their transferability. In the study by Maithel et al., an unknown number of patients in the cohort were staged pre-operatively by MRI instead of CT, which may have detected a higher number of liver metastases missed on CT.33 Two studies also used laparoscopic ultrasound which is more sensitive at detecting small liver metastases,18, 35 as well as locally advanced disease encasing the mesenteric vessels,36 which would have resulted in an increased yield of unresectable cases.

Clinical and laboratory factors

Clinical factors such as jaundice,37, 38, 39, 40 weight loss, performance status,40, 41 and pain,42, 43, 44, 45 as well as and laboratory factors such as C-reactive protein (CRP),40, 46, 47, 48 ferritin,47 neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio,49 lactate dehydrogenase (LDH),46 and platelet count,48 have been identified as prognostic indicators in pancreatic cancer. However, few authors have attempted to determine preoperative predictors of resectability.

Smith and co-workers reported the addition of platelet-lymphocyte ratio of ≤150 to a CA 19.9 level of ≤150 kU/l (based on the findings by Schlieman et al.23 and Connor et al.34), significantly improved the positive predictive value for resectability (from 85% to 95%) in patients with suspected periampullary cancers (p = 0.065).50 The authors concluded that 38 out of 183 laparoscopies could have been avoided if these criteria were used. The main limitation of this study was that all patients with ‘suspected’ periampullary malignancy were included (n = 263), even those that subsequently had benign disease.

Previous studies presented in this review have commented on the association between clinical features and unresectable disease. Interestingly, Koenigsrainer et al. observed that jaundice and diarrhoea were more frequently seen in patients without peritoneal carcinomatosis at exploration.21 Other authors have reported an association between pre-operative pain and unresectability (p = 0.01).33 Ong et al. reported patients with unresectable disease had significantly lower platelet count (p = 0.013), higher neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (p = 0.026) and higher CA 19.9-bilirubin ratio (p = 0.022).18 Weight loss has also been reported as a predictor of metastases.51 Many studies however, have failed to show any significant association between unresectability at SL with pain,21 weight loss,21 full blood count,18 liver and/or renal function tests,18 CRP52 and neutrophil-lymphocyte and/or platelet-lymphocyte ratio.52 Based on the inconsistency in results with regards to clinical predictors of resectability in patients with pancreatic cancer, further research is needed to determine clinical factors that may be used to select patients for SL.

Tumour size

Tumour size is one of the most important staging criteria and prognostic indicators in pancreatic cancer.53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58 Studies have shown increased tumour size is associated with metastases not identified on pre-operative CT. Yoshida et al. reported patients with resectable disease at laparotomy had a mean tumour size of 3.1 cm, compared to 4.4 cm in patients with metastatic disease (p < 0.005).59 Similarly, Morganti and co-workers observed patients (n = 54) with a tumour size >3 cm had significantly more metastases at exploration compared to patients with tumours <3 cm (22% versus 0%, respectively; p < 0.01).60 A large study (n = 385) by Slaar et al. found tumour size, weight loss and a history of jaundice were significant predictors of metastasis at exploration.51

A limited number of studies have evaluated the significance of pre-operative tumour size on findings at SL. Garcea and co-authors reported 21 out of 137 patients with resectable disease on CT, had occult metastases at SL. Tumour size of >40 mm increased the diagnostic yield of SL to 31.3% (p < 0.05).52 Similar results have been reported by Chiang et al., in a study of 372 patients, who reported a tumour size >4.8 cm is associated with a 5-fold increase of inoperability (p < 0.0001).61

Based on these results, tumour size ranging between 3 cm and 4.8 cm predicted unresectability. The size of the patient cohorts varied widely (n = 29–385), and the majority of studies calculated the cut-off for tumour size using ROC curve analysis.18, 51, 52, 55 Two of the studies used a combination of staging modalities in addition to CT such as US, ERCP, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography, MRI, and angiography.55, 60 In these studies, it is not clear whether all patients underwent CT and which imaging modality was used to determine tumour size, which limits the applicability of these findings. The combined use of modalities would also increase the accuracy of pre-operative staging compared to CT alone.

Tumour location

Pancreatic tumours of the body and tail are associated with a worse prognosis, presumably because of the advanced stage of disease at diagnosis, compared with pancreatic head cancers which present earlier with signs of obstructive jaundice.62, 63 There are limited studies in the literature reporting the effect on tumour location on resectability in patients with pre-operative staging suggestive of resectable disease.

Contreras et al. observed in patients with potentially resectable tumours (n = 25) or locally advanced disease (n = 33) who underwent SL, occult metastases were more likely with body and tail lesions (p = 0.012).64 Other authors have also reported in patients with resectable or potentially resectable disease undergoing SL, 25% with distal tumours had metastasis, in contrast to 18% of patients with proximal tumours.32 Fujioka et al. also found unresectable disease identified at laparoscopy was more common in patients with tumours in the body or tail of the pancreas (p = 0.0006).19

Due to the limited studies investigating the role of tumour location in the context of resectable disease, its role as an indicator for SL is undefined.

Reported algorithms

Few studies have suggested management algorithms to select patients for SL, to increase the diagnostic accuracy.

Shah and colleagues selected 19 patients for SL if they fulfilled the following criteria: tumour size >4 cm; weight loss >20%; ascites; or CA 19.9 > 1000 U/mL.65 At SL, 11 (58%) patients had metastatic or locally advanced disease and the remaining eight patients underwent resection. SL increased the positive predictive value from 69% to 89%.

Based on the findings from the groups of Schlieman23 and Morganti,60 Satoi and colleagues performed SL in patients with: CA 19.9 level ≥150 U/mL; or tumour size ≥3 cm.66 They compared the frequency of unnecessary laparotomy in 16 (26%) patients selected for SL based on the above criteria, with 33 patients who underwent laparotomy for planned resection prior to the introduction of the SL policy, and demonstrated the frequency of unnecessary laparotomy decreased by 15%. The study allowed for direct comparison of negative laparotomy rates pre and post introduction of SL. The main limitation is cytology of ascites fluid and laparoscopic ultrasonography were used, which would have increased the yield at SL.

Discussion

SL is a minimally invasive modality for staging pancreatic cancer,6 avoiding a laparotomy in patients with occult metastases. Compared to exploratory laparotomy, SL is associated with decreased postoperative pain, a shorter hospital stay, reduced cost, and a higher likelihood of receiving systemic therapy in unresectable cases.67, 68 The aim of this review is to identify indications for SL in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer, and suggest a pre-operative algorithm for staging these patients.

The studies included have their limitations. There is no level I evidence or randomized trials. All studies are retrospective, and from single institution specialized centers; hence the results reported may not be reproducible at other institutions. Although all studies included were published after year 2000, some of the patients were included prior to 2000, and it is likely that the CT used in these cases may have failed to detect metastases present on high-quality CT.18, 19, 21, 22, 23, 34, 50, 51, 55, 59, 69

The definition of unresectable disease varied between studies, with some studies lacking clear, objective criteria. For example, regarding nodal involvement, some authors defined any extra-pancreatic nodal involvement as unresectable,22, 23 whereas other studies did not exclude patients with peripancreatic nodal involvement from resection.18 Regarding vascular structures, the majority of studies state invasion of vascular structures precludes resection,22, 23 whereas other studies were more specific, defining unresectable vascular disease as superior mesenteric or portal vein encasement of >50% or more than >2 cm in length.35, 50, 66 The management of borderline resectable disease with vascular involvement also varies between centers, some being more aggressive with their surgical approach, offering neoadjuvant chemotherapy, followed by resection,70 +/− vascular reconstruction.71, 72, 73

In addition, a large proportion of the studies indirectly assessed the role of SL, by examining the presence of metastases or locally advanced disease at open surgery. The results of these studies must be interpreted with caution, as laparoscopy is unable to assess vascular invasion, lymph node involvement, and deep hepatic metastases.31

Moreover, numerous studies used a combination of pre-operative staging modalities (US, MRI, ERCP, EUS), which increases the diagnostic accuracy compared to CT alone.33, 51, 55, 60 Also, a number of studies used laparoscopic ultrasound with or without peritoneal cytology,50, 52 both of which improve the diagnostic accuracy of SL.18, 35, 63, 74, 75

Suggested staging algorithm

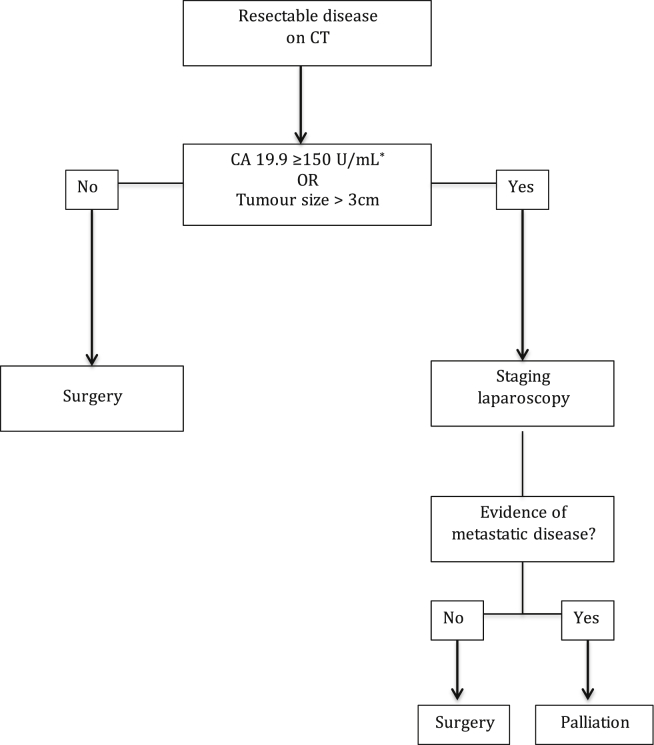

Based on the available data, the most reliable surrogate markers to use for selecting patients for SL to predict unresectability in patients with CT defined resectable pancreatic cancer are CA 19.9 and tumour size. Although there are studies suggesting a role for tumour location (body and tail of the pancreas), CEA levels, and clinical findings such as weight loss and jaundice, there is not enough evidence currently to support their inclusion into an algorithm. With the evidence presented, we propose any patient with a CT suggestive of resectable disease and (1) CA 19.9 of ≥150 U/mL; or (2) tumour size >3 cm should be considered for SL (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Suggested algorithm for selecting patients with pancreatic cancer for staging laparoscopy. [*: CA 19.9 level irrespective of bilirubin level.]

A CA 19.9 level ≥150 U/mL was chosen based on the results of five large studies (n = 159–262), which calculated cut-off values using ROC curve analysis.19, 33, 34, 35 Three of these studies determined resectability at SL, not laparotomy.33, 34, 35 Tumour size >3 cm was chosen based on results from two studies that showed tumours >3 cm were significantly more likely to have metastases at exploration60, 66 (See Fig. 2).

Conclusion

The role of laparoscopy in the staging of pancreatic cancer patients remains controversial. It is common practice that the initial step in the staging algorithm should involve high quality cross-sectional imaging, and selected patients may be considered for SL. Potential predictors of unresectability to select patients for SL include CA 19.9 levels and tumour size. A prospective, multi-center study is now required to validate this algorithm.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Takai S., Satoi S., Toyokawa H., Yanagimoto H., Sugimoto N., Tsuji K. Clinicopathologic evaluation after resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: a retrospective, single-institution experience. Pancreas. 2003;26:243–249. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200304000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeo C.J., Cameron J.L., Lillemoe K.D., Sohn T.A., Campbell K.A., Sauter P.K. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with or without distal gastrectomy and extended retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for periampullary adenocarcinoma, part 2: randomized controlled trial evaluating survival, morbidity, and mortality. Ann Surg. 2002;236:355–366. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200209000-00012. discussion 366–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim J.E., Chien M.W., Earle C.C. Prognostic factors following curative resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma – a population-based, linked database analysis of 396 patients. Ann Surg. 2003;237:74–85. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pedrazzoli S., DiCarlo V., Dionigi R., Mosca F., Pederzoli P., Pasquali C. Standard versus extended lymphadenectomy associated with pancreatoduodenectomy in the surgical treatment of adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas - a multicenter, prospective, randomized study. Ann Surg. 1998;228:508–514. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199810000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bipat S., Phoa S., van Delden O.M., Bossuyt P.M.M., Gouma D.J., Lameris J.S. Ultrasonography, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for diagnosis and determining resectability of pancreatic adenocarcinoma – a meta-analysis. J Comput Assisted Tomogr. 2005;29:438–445. doi: 10.1097/01.rct.0000164513.23407.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pisters P.W., Lee J.E., Vauthey J.N., Charnsangavej C., Evans D.B. Laparoscopy in the staging of pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2001;88:325–337. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2001.01695.x. England. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vargas R., Nino-Murcia M., Trueblood W., Jeffrey R.B. MDCT in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: prediction of vascular invasion and resectability using a multiphasic technique with curved planar reformations. Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:419–425. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.2.1820419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stefanidis D., Grove K.D., Schwesinger W.H., Thomas C.R. The current role of staging laparoscopy for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: a review. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:189–199. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camacho D., Reichenbach D., Duerr G.D., Venema T.L., Sweeney J.F., Fisher W.E. Value of laparoscopy in the staging of pancreatic cancer. JOP J Pancreas. 2005;6:552–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conlon K.C., Brennan M.F. Laparoscopy for staging abdominal malignancies. Adv Surg. 2000;34:331–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brockmann J., Emparan C., Hernandez C.A., Sulkowski U., Dietl K.H., Menzel J. Gallbladder bile tumor marker quantification for detection of pancreato-biliary malignancies. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:4941–4947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim H.J., Kim M.H., Myung S.J., Lim B.C., Park E.T., Yoo K.S. A new strategy for the application of CA19-9 in the differentiation of pancreaticobiliary cancer: analysis using a receiver operating characteristic curve. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1941–1946. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01234.x. United States. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritts R.E., Pitt H.A. CA 19-9 in pancreatic cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 1998;7:93–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mann D.V., Edwards R., Ho S., Lau W.Y., Glazer G. Elevated tumour marker CA19-9: clinical interpretation and influence of obstructive jaundice. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:474–479. doi: 10.1053/ejso.1999.0925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang C.M., Kim J.Y., Choi G.H., Kim K.S., Choi J.S., Lee W.J. The use of adjusted preoperative CA 19-9 to predict the recurrence of resectable pancreatic cancer. J Surg Res. 2007;140:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.vandenBosch R.P., vanEijck C.H.J., Mulder P.G.H., Jeekel J. Serum CA19-9 determination in the management of pancreatic cancer. Hepato-Gastroenterology. 1996;43:710–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yasue M., Sakamoto J., Teramukai S., Morimoto T., Yasui K., Kuno N. Prognostic values of preoperative and postoperative CEA and CA19.9 levels in pancreatic-cancer. Pancreas. 1994;9:735–740. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199411000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ong S.L., Garcea G., Thomasset S.C., Mann C.D., Neal C.P., Abu Amara M. Surrogate markers of resectability in patients undergoing exploration of potentially resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1068–1073. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujioka S., Misawa T., Okamoto T., Gocho T., Futagawa Y., Ishida Y. Preoperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 levels for the evaluation of curability and resectability in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surg. 2007;14:539–544. doi: 10.1007/s00534-006-1184-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehta J., Prabhu R., Eshpuniyani P., Kantharia C., Supe A. Evaluating the efficacy of tumor markers CA 19-9 and CEA to predict operability and survival in pancreatic malignancies. Trop Gastroenterol Off J Dig Dis Found. 2010;31:190–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koenigsrainer I., Zieker D., Symons S., Horlacher K., Koenigsrainer A., Beckert S. Do patient- and tumor-related factors predict the peritoneal spread of pancreatic adenocarcinoma? Surg Today. 2014;44:260–263. doi: 10.1007/s00595-013-0546-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kilic M., Gocmen E., Tez M., Ertan T., Keskek M., Koc M. Value of preoperative serum CA 19-9 levels in predicting resectability for pancreatic cancer. Can J Surg. 2006;49:241–244. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schlieman M.G., Ho H.S., Bold R.J. Utility of tumor markers in determining resectability of pancreatic cancer. Arch Surg. 2003;138:951–955. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.9.951. United States. discussion 955–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang S., Wang Y.-M., Sun C.-D., Lu Y., Wu L.-Q. Clinical value of serum CA19-9 levels in evaluating resectability of pancreatic carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3750–3753. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cappelli G., Paladini S., D'Agata A. Tumor markers in the diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma. Tumori. 1999;85:S19–S21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Civardi G., Cerri L., Cavanna L., Fornari F., Distasi M., Binelli F. Diagnostic-accuracy of a new tumor serologic marker, CA 19-9-comparison with CEA. Tumori. 1986;72:621–624. doi: 10.1177/030089168607200614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delfavero G., Fabris C., Plebani M., Panucci A., Piccoli A., Perobelli L. CA-19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen in pancreatic-cancer diagnosis. Cancer. 1986;57:1576–1579. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860415)57:8<1576::aid-cncr2820570823>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lundin J., Roberts P.J., Kuusela P., Haglund C. The prognostic value of preoperative serum levels of CA-19-9 and CEA in patients with pancreatic-cancer. Br J Cancer. 1994;69:515–519. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim Y.C., Kim H.J., Park J.H., Park D.I., Cho Y.K., Sohn C.I. Can preoperative CA19-9 and CEA levels predict the resectability of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1869–1875. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05935.x. Australia. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vollmer C.M., Drebin J.A., Middleton W.D., Teefey S.A., Linehan D.C., Soper N.J. Utility of staging laparoscopy in subsets of peripancreatic and biliary malignancies. Ann Surg. 2002;235:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200201000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menack M.J., Spitz J.D., Arregui M.E. Staging of pancreatic and ampullary cancers for resectability using laparoscopy with laparoscopic ultrasound. Surg Endoscopy-Ultrasound Interventional Tech. 2001;15:1129–1134. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-0030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karachristos A., Scarmeas N., Hoffman J.P. CA 19-9 levels predict results of staging laparoscopy in pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:1286–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maithel S.K., Maloney S., Winston C., Goenen M., D'Angelica M.I., DeMatteo R.P. Preoperative CA 19-9 and the yield of staging laparoscopy in patients with radiographically resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3512–3520. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Connor S., Bosonnet L., Alexakis N., Raraty M., Ghaneh P., Sutton R. Serum CA19-9 measurement increases the effectiveness of staging laparoscopy in patients with suspected pancreatic malignancy. Dig Surg. 2005;22:80–85. doi: 10.1159/000085297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halloran C.M., Ghaneh P., Connor S., Sutton R., Neoptolemos J.P., Raraty M.G.T. Carbohydrate antigen 19.9 accurately selects patients for laparoscopic assessment to determine resectability of pancreatic malignancy. Br J Surg. 2008;95:453–459. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomson B.N.J., Parks R.W., Redhead D.N., Welsh F.K.S., Madhavan K.K., Wigmore S.J. Refining the role of laparoscopy and laparoscopic ultrasound in the staging of presumed pancreatic head and ampullary tumours. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:213–217. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cleary S.P., Gryfe R., Guindi M., Greig P., Smith L., Mackenzie R. Prognostic factors in resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma: analysis of actual 5-year survivors. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:722–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klein F., Jacob D., Bahra M., Pelzer U., Puhl G., Krannich A. Prognostic factors for long-term survival in patients with ampullary carcinoma: the results of a 15-year observation period after pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB Surg World J Hepatic Pancreat Biliary Surg. 2014;2014:970234. doi: 10.1155/2014/970234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou J., Zhang Q., Li P., Shan Y., Zhao D., Cai J. Jaundice as a prognostic factor in patients undergoing radical treatment for carcinomas of the ampulla of vater. Chin Med J. 2014;127:860–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Papadoniou N., Kosmas C., Gennatas K., Polyzos A., MouratidoU D., Skopelitis E. Prognostic factors in patients with locally advanced (unresectable) or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a retrospective analysis. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:543–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tas F., Sen F., Odabas H., Kilic L., Keskin S., Yildiz I. Performance status of patients is the major prognostic factor at all stages of pancreatic cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2013;18:839–846. doi: 10.1007/s10147-012-0474-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okusaka T., Okada S., Ueno H., Ikeda M., Shimada K., Yamamoto J. Abdominal pain in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer with reference to clinicopathologic findings. Pancreas. 2001;22:279–284. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200104000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fitzgerald P.J. The pathology of pancreatic cancer and its possible relationship to pain. J Pain Symptom Manag. 1988;3:171–175. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(88)90027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kelsen D.P., Portenoy R., Thaler H., Tao Y., Brennan M. Pain as a predictor of outcome in patients with operable pancreatic carcinoma. Surgery. 1997;122:53–59. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(97)90264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ridder G.J., Klempnauer J. Back pain in patients with ductal pancreatic cancer – its impact on resectability and prognosis after resection. Scand J Gastroenterology. 1995;30:1216–1220. doi: 10.3109/00365529509101634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haas M., Heinemann V., Kullmann F., Laubender R.P., Klose C., Bruns C.J. Prognostic value of CA 19-9, CEA, CRP, LDH and bilirubin levels in locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer: results from a multicenter, pooled analysis of patients receiving palliative chemotherapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139:681–689. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1371-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alkhateeb A., Zubritsky L., Kinsman B., Leitzel K., Campbell-Baird C., Ali S.M. Elevation in multiple serum inflammatory biomarkers predicts survival of pancreatic cancer patients with inoperable disease. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2014;45:161–167. doi: 10.1007/s12029-013-9564-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miura T., Hirano S., Nakamura T., Tanaka E., Shichinohe T., Tsuchikawa T. A new preoperative prognostic scoring system to predict prognosis in patients with locally advanced pancreatic body cancer who undergo distal pancreatectomy with en bloc celiac axis resection: a retrospective cohort study. Surgery. 2014;155:457–467. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stotz M., Gerger A., Eisner F., Szkandera J., Loibner H., Ress A.L. Increased neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio is a poor prognostic factor in patients with primary operable and inoperable pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:416–421. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith R.A., Bosonnet L., Ghaneh P., Sutton R., Evans J., Healey P. The platelet-lymphocyte ratio improves the predictive value of serum CA19-9 levels in determining patient selection for staging laparoscopy in suspected periampullary cancer. Surgery. 2008;143:658–666. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Slaar A., Eshuis W.J., van der Gaag N.A., Nio C.Y., Busch O.R.C., van Gulik T.M. Predicting distant metastasis in patients with suspected pancreatic and periampullary tumors for selective use of staging laparoscopy. World J Surg. 2011;35:2528–2534. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garcea G., Cairns V., Berry D.P., Neal C.P., Metcalfe M.S., Dennison A.R. Improving the diagnostic yield from staging laparoscopy for periampullary malignancies the value of preoperative inflammatory markers and radiological tumor size. Pancreas. 2012;41:233–237. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31822432ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fortner J.G., Klimstra D.S., Senie R.T., Maclean B.J. Tumor size is the primary prognosticator for pancreatic cancer after regional pancreatectomy. Ann Surg. 1996;223:147–153. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199602000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Forssell H., Wester M., Akesson K., Johansson S. A proposed model for prediction of survival based on a follow-up study in unresectable pancreatic cancer. BMJ Open. 2013;3:6. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chiang K.-C., Yeh C.-N., Lee W.-C., Jan Y.-Y., Hwang T.-L. Prognostic analysis of patients with pancreatic head adenocarcinoma less than 2 cm undergoing resection. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4305–4310. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shimada K., Sakamoto Y., Sano T., Kosuge T., Hiraoka N. Reappraisal of the clinical significance of tumor size in patients with pancreatic ductal carcinoma. Pancreas. 2006;33:233–239. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000232917.78890.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Jong M.C., Li F., Cameron J.L., Wolfgang C.L., Edil B.H., Herman J.M. Re-evaluating the impact of tumor size on survival following pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2011;103:656–662. doi: 10.1002/jso.21883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Agarwal B., Correa A.M., Ho L. Survival in pancreatic carcinoma based on tumor size. Pancreas. 2008;36:E15–E20. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0b013e31814de421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoshida T., Matsumoto T., Morii Y., Ishio T., Kitano S., Yamada Y. Staging with helical computed tomography and laparoscopy in pancreatic head cancer. Hepato-Gastroenterology. 2002;49:1428–1431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morganti A.G., Brizi M.G., Macchia G., Sallustio G., Costamagna G., Alfieri S. The prognostic effect of clinical staging in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:145–151. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chiang K.-C., Lee C.-H., Yeh C.-N., Ueng S.-H., Hsu J.-T., Yeh T.-S. A novel role of the tumor size in pancreatic cancer as an ancillary factor for predicting resectability. J Cancer Res Ther. 2014;10:142–146. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.131464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Artinyan A., Soriano P.A., Prendergast C., Low T., Ellenhorn J.D.I., Kim J. The anatomic location of pancreatic cancer is a prognostic factor for survival. HPB. 2008;10:371–376. doi: 10.1080/13651820802291233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fernandez-del Castillo C.L., Warshaw A.L. Pancreatic cancer. Laparoscopic staging and peritoneal cytology. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 1998;7:135–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Contreras C.M., Stanelle E.J., Mansour J., Hinshaw J.L., Rikkers L.F., Rettammel R. Staging laparoscopy enhances the detection of occult metastases in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:663–669. doi: 10.1002/jso.21402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shah D., Fisher W.E., Hodges S.E., Wu M.-F., Hilsenbeck S.G., Brunicardi C. Preoperative prediction of complete resection in pancreatic cancer. J Surg Res. 2008;147:216–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Satoi S., Yanagimoto H., Toyokawa H., Inoue K., Wada K., Yamamoto T. Selective use of staging laparoscopy based on carbohydrate antigen 19-9 level and tumor size in patients with radiographically defined potentially or borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2011;40:426–432. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182056b1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Velanovich V., Wollner I., Ajlouni M. Staging laparoscopy promotes increased utilization of postoperative therapy for unresectable intra-abdominal malignancies. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:542–546. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(00)80099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jarnagin W.R., Bodniewicz J., Dougherty E., Conlon K., Blumgart L.H., Fong Y. A prospective analysis of staging laparoscopy in patients with primary and secondary hepatobiliary malignancies. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:34–42. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(00)80030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jimenez R.E., Warshaw A.L., Rattner D.W., Willett C.G., McGrath D., del Castillo C. Impact of laparoscopic staging in the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Arch Surg. 2000;135:409–414. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.White R.R., Paulson E.K., Freed K.S., Keogan M.T., Hurwitz H.I., Lee C. Staging of pancreatic cancer before and after neoadjuvant chemoradiation. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5:626–633. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(01)80105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Todd K.E., Gloor B., Lane J.S., Isacoff W.H., Reber H.A. Resection of locally advanced pancreatic cancer after downstaging with continuous-infusion 5-fluorouracil, mitomycin-C, leucovorin, and dipyridamole. J Gastrointest Surg Off J Soc Surg Aliment Tract. 1998;2:159–166. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(98)80008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.White R.R., Hurwitz H.I., Morse M.A., Lee C., Anscher M.S., Paulson E.K. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation for localized adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:758–765. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0758-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Al-Haddad M., Martin J.K., Nguyen J., Pungpapong S., Raimondo M., Woodward T. Vascular resection and reconstruction for pancreatic malignancy: a single center survival study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1168–1174. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0216-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schachter P.P., Avni Y., Shimonov M., Gvirtz G., Rosen A., Czerniak A. The impact of laparoscopy and laparoscopic ultrasonography on the management of pancreatic cancer. Arch Surg. 2000;135:1303–1307. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.11.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jimenez R.E., Warshaw A.L., Fernandez-Del Castillo C. Laparoscopy and peritoneal cytology in the staging of pancreatic cancer. J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat Surg. 2000;7:15–20. doi: 10.1007/s005340050148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]