Abstract

Background:

Specialty psychosomatic clinics are a felt need in low- and middle-income countries, but its benefits and challenges have not been reported so far.

Aims:

To describe the process, challenges, and opportunities that we encountered in setting up a specialty psychosomatic clinic at a government medical college in South India.

Methods:

The biweekly psychosomatic clinic was located in the Department of Psychiatry and manned by a multimodal team. Structured questionnaires were used to evaluate all patients. All psychiatric diagnoses were made as per International Classification of Diseases-10, clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Management comprised both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapeutic interventions.

Results:

A total of 72 patients registered for services in the 1st year of the clinic. The mean age of the sample was 36.6 years (range 14–60 years). A median of 2 years and 19 visits to various care providers had elapsed before their visit to the clinic. The index contact was a general practitioner in the majority of cases though an overwhelming majority (95.6%) had also sought specialist care. The most common diagnostic cluster was the somatoform group of disorders (50.0%). Antidepressants were the most commonly prescribed medications (70.6%).

Conclusion:

The specialty psychosomatic clinic provided better opportunities for a more comprehensive evaluation of people with medically unexplained symptoms and better resident training and focused inter-disciplinary research. It describes a scalable model that can be replicated in similar resource constrained settings.

Keywords: Challenges, clinic, medically unexplained symptoms, opportunities, psychosomatic

Introduction

Clinicians commonly encounter patients with physical symptoms that lack a sufficient organic basis.[1] Often, unclear and overlapping terms such as atypical, functional, nonorganic, somatoform, and psychogenic are used to label them. Most of these are seen to have a pejorative connotation and end up doing more harm than good to the patient as physicians become very dismissive in their dealings with such patients.[2] The term “medically unexplained symptoms” (MUS) is now preferred for these complaints as they do not imply psychological causation and are more likely to be acceptable to the sufferers.[3] They are often associated with steep healthcare costs and lower economic productivity.[4,5,6,7] MUS has many intrinsic features such as possible neural sensory amplification and preoccupation with the meaning of symptoms, which make it an attractive model for understanding and treating psychosomatic conditions.[8] In India, the management of people with MUS poses unique issues as the extant medical training system does not produce an exclusive stream of primary care practitioners who look after most MUS patients like in the West.[9,10,11] Hence, most of their management is left to specialist care that is obviously a strain on the meagre resources. Poor rates of completed psychiatry referrals, rejection of physician reassurance and normalizing explanations, and conflicting models of understanding the problems are some of the challenges in managing MUS.[12,13,14] Evidence from randomized controlled trials, mostly conducted in primary care settings, reveal that multi-dimensional strategies involving principles of cognitive-behavioral therapy, targeted pharmacotherapy, and patient-centered management can be cost effective, and, at the same time, increase patient satisfaction and health outcomes.[3] If all these required services are available in a single place, it may logically enhance follow-up rates, patient satisfaction and reduce redundant consultations. In this study, we aim to describe our novel attempt to set up a psychosomatic clinic, in a tertiary care hospital in South India, with the goal of providing comprehensive services to patients with MUS. The practical challenges and opportunities that emerged in this process are elaborated so that similar initiatives can be encouraged. We also report the patient profiles and their pathways to care.

Methods

Context of the clinic

This Psychosomatic Clinic was established in the Department of Psychiatry of a state-funded teaching cum Tertiary Care Hospital in South India. The hospital has all clinical and paraclinical departments functioning within its own premises. Any patient can just walk-in and avail all the services without any prior appointment. Treatment is heavily subsidized, and most of the investigations and many basic medications are dispensed free of cost. The majority of patients who avail the services belong to lower socioeconomic strata. The Department of Psychiatry has a good consultation-liaison service and gets a fair number of cases referred from other departments. Many of the patients are referred for somatic complaints for which no commensurate physical diagnosis could be entertained. Since many of them are unhappy at being sent to a psychiatrist and also because of high attrition levels, the need was felt for a separate clinic to specifically address the complex concerns of patients with psychosomatic problems. Initially, it was decided to focus upon people presenting with MUS as they formed the bulk of psychosomatic referrals. Prior to the inception of the clinic, letters were sent to all clinical departments sensitizing them to its nature and scope to ensure prompt referrals.

Structure of the clinic

The psychosomatic clinic was spaced in the department of psychiatry for reasons of feasibility. The workflow of the clinic is shown in Figure 1. It was planned as a biweekly clinic, with 1 day of the week dedicated for detailed assessment of new cases and the other day for follow-up of the registered cases. The team manning the clinic comprised a consultant psychiatrist, one senior resident (equivalent to registrar), one junior resident trainee (equivalent to PG registrar) posted on rotation, a clinical psychologist as well as a psychiatric social worker. The consultant supervised the overall functioning of the clinic and discussed the case workups. The senior resident was involved in providing clinical care and managing administrative issues. The junior resident did detailed assessments and carried out psychotherapeutic interventions in selected cases. As per International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10, clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines,[15] and formulation of management plan, allotment of diagnosis was done after discussion with the consultant psychiatrist. The clinical psychologist provided structured psychotherapeutic interventions for cases, and psychiatric social worker attended to psychosocial issues if any.

Figure 1.

Workflow of the psychosomatic clinic

Assessment and management

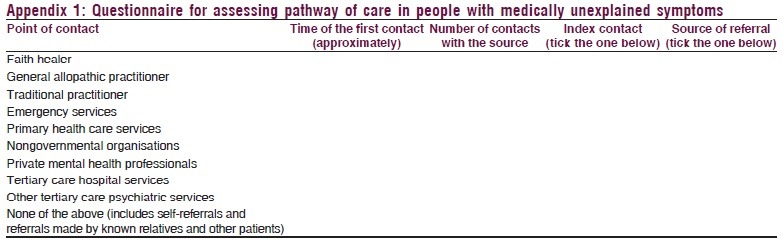

The patients who were referred to Department of Psychiatry with primarily somatic complaints were screened by a senior resident, and an appointment was given for further detailed assessment that was conducted in a single day using a structured questionnaire. The first part of the questionnaire covers basic demographic and clinical details. Subsequently, several-structured instruments were used to assess various parameters such as explanatory models of illness, pathways to care, psychological morbidity, social support, coping, and quality of life. The pathway of care was recorded using a specially designed questionnaire to explore the sequence of healthcare providers accessed prior to being evaluated in the clinic [Appendix 1]. The questionnaire elicited the details about the first contact (year and number of visits), the sequence of accessing various healthcare providers, and source of referral to the psychiatry department. It was tested for content validity by three subject experts, each with more than 7 years of experience in the field. Subsequently, its inter-rater reliability was tested in a small sample (n = 15) of subjects and found to be adequate (Cohen's Kappa = 0.73, P < 0.001). To reduce recall bias, information was also collected from the informant and medical records wherever available. A detailed elaboration of all the other instruments used in the clinic is beyond the scope of this paper.

The average assessment time for a single patient was 45 min. After detailed assessment of every patient, the case was discussed with the consultant following whom an ICD-10 diagnosis was allotted and further management plan drawn up. Management comprised both pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions. Psychotherapy was delivered by clinical psychologists and psychiatry residents. Regular follow-ups were advised to keep the patient in the treatment loop.

Data analysis and synthesis

Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows, version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL, USA). The analysis was conducted for the patients enrolled in the clinic in the 1st year of its existence (January 2014 to December 2014). The present paper aims to report the demographic and clinical profile of the sample and their pathways to care. The analysis was mainly descriptive in nature, and inferential statistics was not carried out. Missing value imputation was not done, and the analysis was conducted with the available data. The various opportunities and challenges stemming from the establishment of this psychosomatic clinic were synthesized.

Results

Demographic characteristics and pathways of care

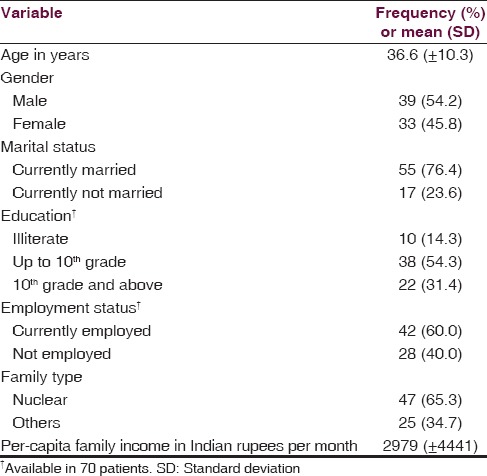

During the 1st year of the clinic, 72 patients were registered in the clinic. The demographic characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the sample was 36.6 years with a range of 14–60 years. Men slightly outnumbered women at the clinic. The majority of the patients were married, educated up to 10th grade, employed, and belonged to a nuclear family.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients (n=72)

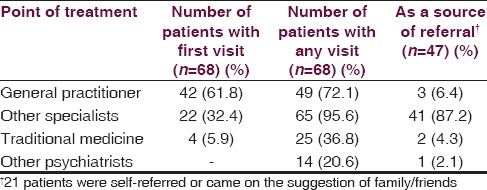

The pathway of care data was available for 68 patients (94.4% of the sample) and is shown in Table 2. The patients had a median of 19 visits (inter-quartile range [IQR] of 9–30 visits) to various care providers over a median period of 24 months (IQR 12–84 months), before being evaluated in the department of psychiatry. The index contact was with a general practitioner in the majority of the cases (61.8%) though a substantial proportion of the patients (32.4%) had visited specialists at the first contact. A large majority of the patients (95.6%) had visited specialists at some point of time before seeking treatment at the center. The source of referral to the Psychiatry Department was the patient himself/herself or family/friends in 21 patients (30.88%).

Table 2.

Pathways of care

Clinical features

Somatoform group of disorders constituted the most common diagnosis in the sample (n = 36, 50.0%), followed by depressive disorders (n = 22, 30.6%) and anxiety spectrum disorders (n = 15, 20.8%). The somatoform cluster could be further broken up into - undifferentiated somatoform disorder in 16, somatoform pain disorder in 10, somatic-autonomic dysfunction in 4, somatization disorder in 1, and other somatoform disorder/somatoform disorder not otherwise specified in 5. About one-tenth of the sample (n = 8) had more than one psychiatric diagnosis while 2 patients (2.8% of the sample) had only physical disorders and no psychiatric disorders.

Discussion

Challenges posed and opportunities provided by the clinic

The present psychosomatic clinic, though in its infancy, provides some opportunities and highlights key challenges. The clinic provides convenience of services in a single location to patients with MUS, instead of being referred to different specialists for various aspects of care. In the current Indian scenario of human resource supply constraints, it is also scalable and can facilitate development of locally acceptable and efficacious models of care. A possible suggestion would be to train the physicians skilled in alternate systems of medicine who form a sizeable pool to manage these patients in primary care and vertically integrate them with such clinics in other higher centers. This may preempt visit to specialists unless deemed necessary. As far as tertiary Care Centers are concerned, offering care in a psychosomatic clinic may yield further opportunities for collaboration with medical and surgical specialists and de-stigmatize mental healthcare for these patients. The clinic provides opportunities for better training of healthcare personnel dealing with MUS patients. The psychiatry residents get wider exposure to the varied psychosomatic presentations, and treatment approaches used. At present, the clinic is involved in training psychiatry residents, but modules can be developed for the training of other health professionals in the future. Last, such a dedicated clinic may yield better and diverse research opportunities focusing on MUS.

Some of the challenges that have been experienced in running the clinic include first, the poor referral rates (1–2 patients/week) and second, convincing patients of the efficacy of psychological treatments for their problems. Third, as per locally prevalent cultural beliefs, patients expect some blood test and some tablets (and preferably colored injections and intravenous “glucose”) to be given as a part of most treatments. As of present, advocating the efficacy of psychotherapeutic measures has been found to be challenging. Fourth, training modules need to be developed for more focused training of the residents and other professionals, emphasizing on communication and nonconfrontational approach toward patients with MUS.

To conclude, this psychosomatic clinic provided an opportunity for detailed evaluation of MUS patients. It unlocks opportunities for inter-disciplinary cross talk and better dissemination of information about the special needs of people with MUS. There is very little systematic research output on psychosomatic disorders from developing countries, despite previous investigators reporting prevalence of psychosomatic symptoms among psychiatric populations comparable to that in the West.[16] Other spinoffs included better training of psychiatry residents in a difficult area where clinicians are often wanting. Possible limitations of our clinic include its location in a tertiary care hospital setting, working with group concepts, and lumping together patients with different spectrum of diagnostic categories such as anxiety and depression for easier treatment logistics. Lack of dedicated in-patient beds and funding constraints are other limitations to its growth and expansion. The challenge for future healthcare researchers from developing countries such as India, where there is no pool of primary care physicians, is to develop cost-effective and culturally compatible models of care which vertically integrate the tertiary healthcare and primary healthcare systems for MUS patients. Such models may eventually take the locus of care away from specialists to the primary healthcare arena sparing much needed human resources. We hope this paper will provide practical insights to clinicians working with MUS, stem further research in this area and promote the development of more such clinics across the length and breadth of the country.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

A preliminary version of this paper was presented as a research poster at the 67th Annual National Conference of the Indian Psychiatric Society (ANCIPS 2015), Hyderabad from January 8th to 11th, 2015.

Appendix 1

The following questions are intended to assess your various points of contact with health care providers and source of referral before the current consultation. Please try to recollect and answer them as accurately as possible.

References

- 1.Burton C. Beyond somatisation: A review of the understanding and treatment of medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS) Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53:231–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirmayer LJ. Mind and body as metaphors: Hidden values in biomedicine. In: Lock M, Gordon D, editors. Biomedicine Examined. Springer Netherlands: 1988. [Last cited on 2015 Aug 16]. pp. 57–93. Available from: http://www.link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-009-2725-4_4 . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith RC, Lein C, Collins C, Lyles JS, Given B, Dwamena FC, et al. Treating patients with medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:478–89. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20815.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hiller W, Fichter MM, Rief W. A controlled treatment study of somatoform disorders including analysis of healthcare utilization and cost-effectiveness. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54:369–80. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00397-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin A, Rauh E, Fichter M, Rief W. A one-session treatment for patients suffering from medically unexplained symptoms in primary care: A randomized clinical trial. Psychosomatics. 2007;48:294–303. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.48.4.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barsky AJ, Ettner SL, Horsky J, Bates DW. Resource utilization of patients with hypochondriacal health anxiety and somatization. Med Care. 2001;39:705–15. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200107000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koola MM, Kuttichira P. Psychosocioeconomic study of medically unexplained physical symptoms. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34:159–63. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.101785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirmayer LJ, Groleau D, Looper KJ, Dao MD. Explaining medically unexplained symptoms. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49:663–72. doi: 10.1177/070674370404901003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh S, Badaya S. Health care in rural India: A lack between need and feed. South Asian J Cancer. 2014;3:143–4. doi: 10.4103/2278-330X.130483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parker R, Forrest L, Ward N, McCracken J, Cox D, Derrett J. How acceptable are primary health care nurse practitioners to Australian consumers? Collegian. 2013;20:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Badrakalimuthu VR, Rangasamy Sathyavathy V. Mental health practice in private primary care in rural India: A survey of practitioners. World Psychiatry. 2009;8:124–5. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Page LA, Wessely S. Medically unexplained symptoms: Exacerbating factors in the doctor-patient encounter. J R Soc Med. 2003;96:223–7. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.5.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards TM, Stern A, Clarke DD, Ivbijaro G, Kasney LM. The treatment of patients with medically unexplained symptoms in primary care: A review of the literature. Ment Health Fam Med. 2010;7:209–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rief W, Heitmüller AM, Reisberg K, Rüddel H. Why reassurance fails in patients with unexplained symptoms – An experimental investigation of remembered probabilities. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Description and Diagnostic Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaturvedi SK, Michael A. Psychosomatic disorders in psychiatric patients in a developing country. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1988;34:123–9. doi: 10.1177/002076408803400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]