Abstract

Mammalian mitochondria contain multiple small genomes. While these organelles have efficient base excision removal of oxidative DNA lesions and alkylation damage, many DNA repair systems that work on nuclear DNA damage are not active in mitochondria. What is the fate of DNA damage in the mitochondria that cannot be repaired or that overwhelms the repair system? Some forms of mitochondrial DNA damage can apparently trigger mitochondrial DNA destruction, either via direct degradation or through specific forms of autophagy, such as mitophagy. However, accumulation of certain types of mitochondrial damage, in the absence of DNA ligase III (Lig3) or exonuclease G (EXOG), enzymes required for repair, can directly trigger cell death. This review examines the cellular effects of persistent damage to mitochondrial genomes and discusses the very different cell fates that occur in response to different kinds of damage.

Keywords: mitochondria, mitochondrial DNA, DNA repair, autophagy, human disease

2. INTRODUCTION

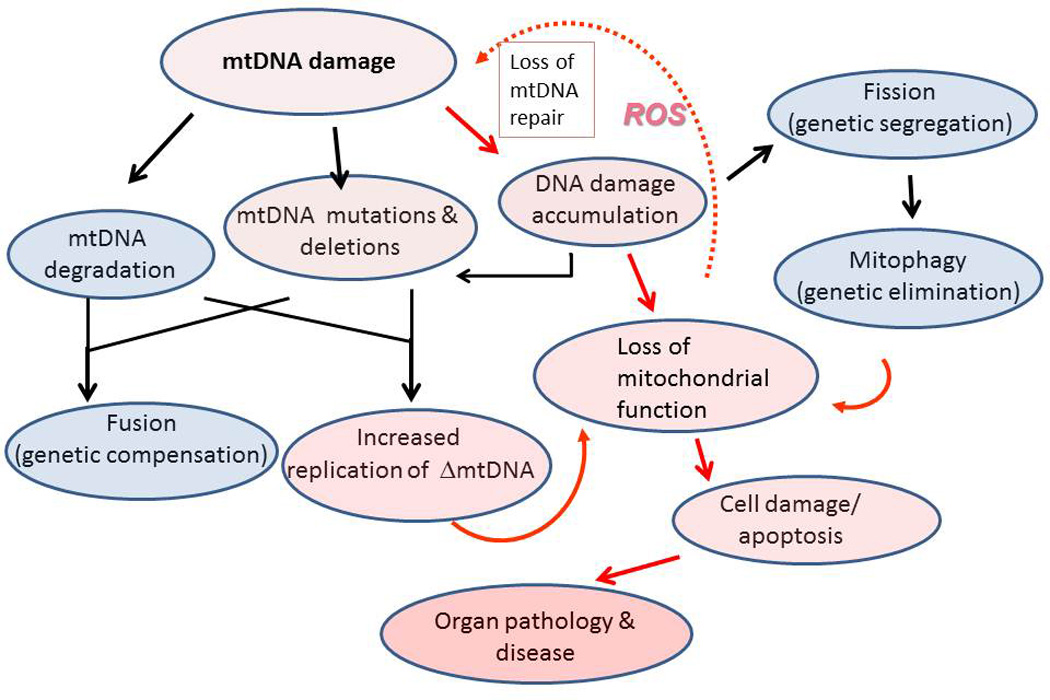

Mitochondria are essential cellular organelles that provide energy in the form of ATP and important metabolic intermediates to a number of cellular functions including lipid biogenesis. In addition, mitochondria are important for other key processes including calcium homeostasis, iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis, and heme production. Interestingly, mitochondria also have several proteins with multiple roles; for example, cytochrome C carries electrons in the intermembrane space as part of the electron transport chain, but cytochrome C release is also responsible for triggering cellular apoptosis. Mitochondria maintain a small genome, which in human cells is 16,569 bp in length and encodes 22 tRNAs, 2 ribosomal RNAs and 13 polypeptides. These polypeptides comprise seven subunits of Complex I, one subunit of Complex III, three subunits of Complex IV and two subunits of Complex V. Most mitochondrial proteins are nuclear encoded, and all of the 1000 plus proteins necessary for DNA replication, repair, and transcription must be imported into the mitochondria (1–3). Thus, synthesis of mitochondrial proteins must be well coordinated with nuclear events, and there is an important cross-talk between these two organelles (4). This chapter reviews evidence that mitochondrial damage and/or loss of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) repair proteins promotes a cascade of quality control events, including mitochondrial fission and fusion, and that when quality control is insufficient such insults may culminate in cellular loss, pathology and disease (Figure 1).

Figure. 1.

Cellular responses to mitochondrial DNA damage. MtDNA damage can result from endogenous, cytoplasmic, and environmental sources, and the persistence of mtDNA damage can cause mtDNA degradation. Faulty repair or replication can result in mtDNA point mutations or deletions, resulting in heteroplasmy. Such mutations ultimately results in loss of mitochondrial function. Fusion provides genetic complementation through the mixing of mtDNA damaged/depleted products with intact mtDNA, a process which maintains mitochondrial respiratory activity. Fission segregates mitochondrial fragments containing excessively damaged or depleted mtDNA. Mitochondrial membrane depolarization and increased ROS production in the mitochondrial fragments triggers their destruction by mitophagy. Increased ROS or loss of DNA repair enzymes can increase mtDNA damage and mitophagy of dysfunctional mitochondrial fragments. When the affected population of mitochondria exceeds the threshold, cellular dysfunction and subsequent end-organ damage ensue. Red arrows trace the pathophysiological responses, red shading indicates severity of the cellular response to mtDNA damage. Black arrows trace mtDNA quality control mechanisms, shaded blue areas show protective responses to mtDNA damage.

REPAIR OF MITOCHONDRIAL DNA

Base excision repair (BER)

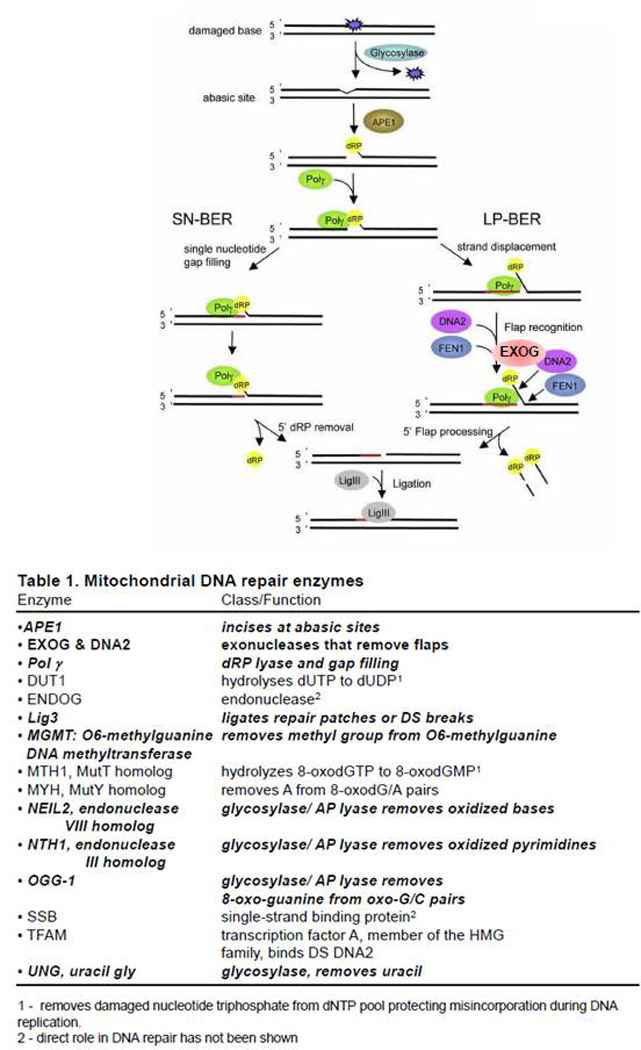

Base excision repair (BER) in mitochondria has been well characterized (Figure 2 and Table 1), as discussed in two recent and excellent thorough reviews (2, 3). Briefly, during the process of mitochondrial BER, one of several glycosylases recognizes a specific type of base damage, typically oxidized bases or bases with small adducts such as methyl groups. It seems logical that mitochondria would require this repair pathway, since most intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced in mitochondria, and mtDNA suffers a larger amount of oxidative damage than the nuclear genome after exposure to oxidants, such as hydrogen peroxide (5). Thus, a common BER pathway involves 8-oxo-deoxyguanine glycosylase (OGG1). OGG1 removes the 8-oxo-deoxyguanine moiety by breaking the glycosidic bond between the DNA base and the sugar. OGG1 is a bifunctional glycosylase with an associated lyase activity of that can then cleave the resulting abasic site, leaving a 3’-phospho-α,β unsaturated aldehyde. Monofunctional base damage specific glycosylases which lack lyase activity generate an abasic site that is acted on by apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease, APEI (also called ref-1), which cleaves the phosphodiester backbone. DNA polymerase gamma (PolG) requires a 3’-hydroxyl group, which serves as a primer on which to add new nucleotides, and APEI generates such an end in pathways involving both monofunctional or bifunctional glycosylases. Although PolGhas an associated lyase activity which removes deoxyribose moieties from DNA during single nucleotide (SN)-BER (the insertion of a single nucleotide during the repair of a damaged base) (6), PolGis thought to carry out strand displacement synthesis generating a 5’ flap that needs to be processed by a flap endonuclease when carrying out long patch (LP)-BER (7). LP-BER is required in the repair of oxidized bases lacking a 5’ aldehyde group (which would otherwise be acted upon by a lyase) and results in the synthesis of a repair patch containing 2–12 nucleotides. Flap structure-specific endonuclease 1 (FEN1), DNA replication helicase/nuclease 2 (DNA2), and exonuclease G (EXOG) have each been proposed to remove the 5’-flap generated in LP-BER (reviewed in (3, 8)). Once the repair patch has been made by PolG and the 5’-flap has been trimmed, the resulting nick is sealed by the action of DNA ligase III (LIG3), which works both in the mitochondria and the nucleus (9).

Figure 2.

Mitochondrial base excision repair. Base damage is detected by one of several glycosylases, which are directed to the mitochondria through differential splicing and an MLS amino-terminal sequence. Once a damaged base is removed, AP endonuclease (APEI) cleaves the phosphodiester backbone generating a deoxyribose moiety that can be excised by DNA polymerase γ (PolG) in short patch single-nucleotide (SN) repair. However, depending on the damage processing, mitochondria may also perform long-patch (LP) repair in which PolGdoes strand displacement synthesis creating a 5’ flap that must be cleaved by one of several putative mitochondrial flap-endonucleases. Strong evidence suggests that EXOG is primarily responsible for this action. Once the flap has been processed, LIG3 can seal the newly synthesized repair patch. Loss of EXOG or LIG3 appear to be lethal to most mammalian cells tested. Adapted from reference (77) with permission.

Table 1.

Mitochondrial DNA repair enzymes

| Enzyme | Class/Function |

|---|---|

| • APE1 | Incises at abasic sites |

| • EXOG & DNA2 | exonucleases that remove flaps |

| • Pol γ | dRP lyase and gap filling |

| • DUT1 | hydrolyses dUTP to dUDP1 |

| • ENDOG | endonuclease2 |

| • Lig3 | ligates repair patches or DS breaks |

| • MGMT: O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase | removes methyl group from O6-methylguanine |

| • MTH1, MutT homolog | hydrolyzes 8-oxodGTP to 8-oxodGMP1 |

| • MYH, MutY homolog | removes A from 8-oxodG/A pairs |

| • NEIL2, endonuclease VIII homolog | glycosylase/AP lyase removes oxidized bases |

| • NTH1, endonuclease III homolog | glycosylase/AP lyase removes oxidized pyrimidines |

| • OGG-1 | glycosylase/AP lyase removes 8-oxo-guanine from oxo-G/C pairs |

| • SSB | single-strand binding protein2 |

| • TFAM | transcription factor A, member of the HMG family, binds DS DNA2 |

| • UNG, uracil gly | glycosylase, removes uracil |

removes damaged nucleotide triphosphate from dNTP pool protecting misincorporation during DNA replication

direct role in DNA repair has not been shown

Other pathways

Another repair pathway in mitochondria is direct reversal, in which mitochondria apparently have the ability to enzymatically reverse O6-methylguanine lesions (reviewed in (2, 3)). Some evidence also exists for mismatch repair and double strand break repair in mammalian cells, the latter of which is discussed in more detail in section 5.3. However, one robust repair system that operates in the nucleus and is notably absent in the mitochondria is nucleotide excision repair (NER), reviewed in (2, 3, 10). Since NER is responsible for the removal of a wide range of DNA lesions that are caused by many environmental insults such as ultraviolet (UV) radiation, food contaminants (e.g. aflatoxin B1) and air pollutants (e.g. polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) the lack of removal of these replication-inhibiting lesions can lead to grave consequences for mtDNA stability, a problem examined in detail later in this article.

4. LOSS OF KEY MTDNA ENZYMES CAUSES CELL DEATH

EXOG

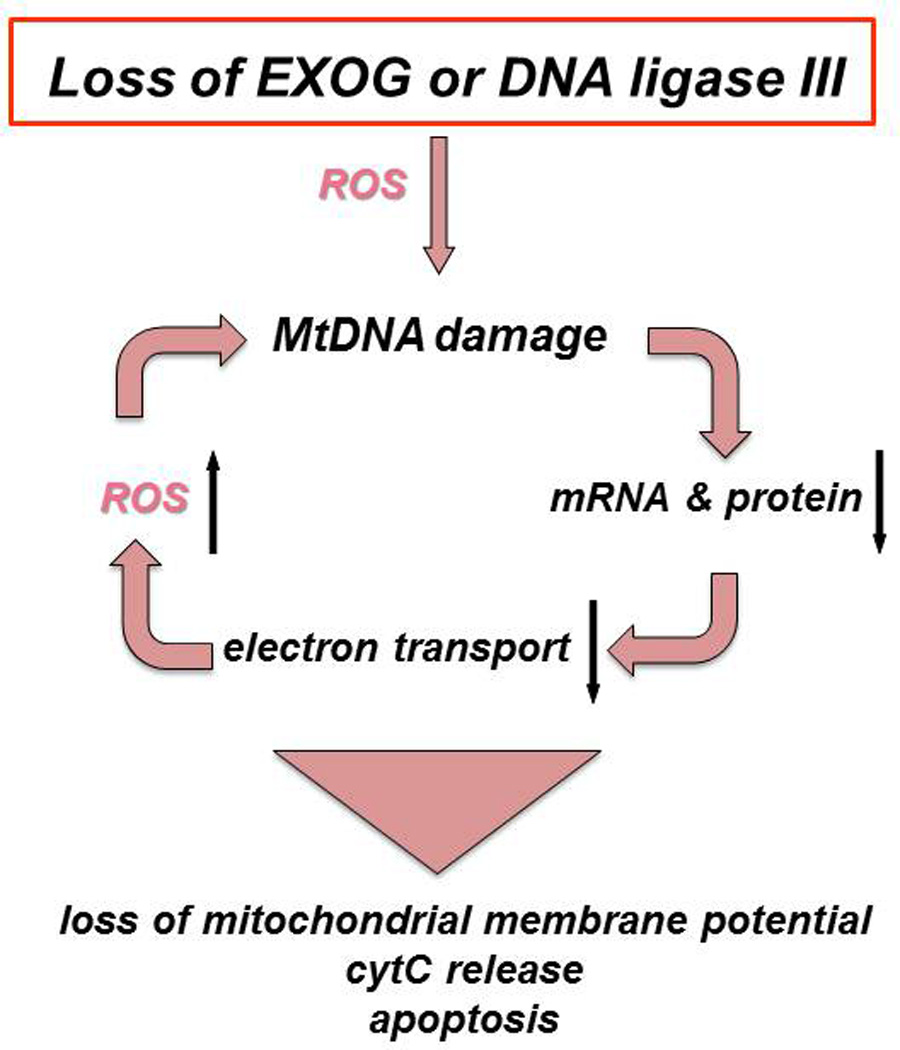

In 2008, the eukaryotic homolog of endonuclease G (ENDOG), EXOG, was found to exist exclusively in the mitochondria using several criteria including: 1) the identification of a bona fide mitochondrial leader sequence (MLS) which was later shown to promote exclusive mitochondrial localization of enhanced GFP; 2) gold particle-antibody labeling of EXOG that revealed the enzyme in the mitochondrial matrix, and 3) a demonstration of 5’ ↓ 3’ exonuclease activity in highly purified mitochondrial extracts (11). Subsequently, working with Sankar and Szczesny, we found that siRNA knock down of EXOG resulted in persistent mtDNA damage as detected using a quantitative PCR (QPCR) assay, and the rapid onset of apoptosis (8). An analysis of highly purified mitochondrial extracts from EXOG-depleted cells showed that BER was interrupted prior to ligation, indicating that the loss of EXOG flap-endonuclease activity inhibited this pathway. MCF7 cells, which lack caspase-3 activity and were silenced for EXOG expression, have decreased oxidative phosphorylation, implicating EXOG in the maintenance of mitochondrial function (8). Further experiments in myoblasts have shown that the knockdown of EXOG causes cell death and that the ectopic expression of EXOG facilitates myoblast differentiation into myotubes, suggesting that age-related loss of EXOG in humans may contribute to the sarcopenia common in older individuals (12). Since EXOG is exclusively a mitochondrial protein (11), the collective data imply that a loss of EXOG exacerbates mtDNA damage through the build-up of toxic BER intermediates, which diminish organelle function due to the loss of mtDNA integrity and induce rapid mitochondrial-initiated apoptosis; strongly supporting the hypothesis that mtDNA damage is sufficient to cause cell death (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Consequences of losing either of two key mitochondrial DNA metabolizing enzymes. EXOG and LIG3 prevent the accumulation of mtDNA damage and subsequent loss of mitochondrial function. Loss of EXOG can increase ROS production and initiate a vicious cycle of mtDNA damage (8). Deficiency in either EXOG (8) or LIG3 (9) causes persistent mtDNA damage that can trigger a cascade of events including loss of the mitochondrial membrane potential, increased ROS generation, release of cytochrome C and apoptotic cell death.

DNA Ligase III (LIG3)

DNA Ligase III (LIG3) is the only known DNA ligase activity in mitochondria. Thus, it might be expected that loss of this activity would cause persistent mtDNA damage and functional decline of mitochondria. However, since this enzyme also has important nuclear functions, its roles in mitochondrial and nuclear events have been difficult to dissect. The Jasin group used a pre-emptive complementation approach to both knock out the expression of DNA LIG3 and introduce either a nuclear or mitochondrial targeted protein. Surprisingly, cells containing the enzyme only in their mitochondria survived, while those cells having only nuclear DNA LIG3 were not viable. They further showed that active catalytic activity of DNA LIG3 in the mitochondria was responsible for this rescue. Furthermore, Jasin’s group in collaboration with our laboratory showed that the expression of any DNA ligase activity in mitochondria was sufficient to rescue the knockout, maintain a high mtDNA copy number and support rapid repair of hydrogen peroxide-induced mtDNA damage (9). The McKinnon group extended this work in a mouse model showing that removal of DNA LIG3 from the mouse nervous system resulted in mtDNA loss and profound mitochondrial dysfunction causing severe ataxia (13). Subsequent studies of DNA LIG3 deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts revealed that ligase deficiency depleted mtDNA and that the cells could only be cultured in media supplemented with uridine and high levels of glucose, a hallmark of the rho(0) phenotype (14). Since the loss of mitochondrial DNA ligase activity has profound effects on cell viability, several researchers, including Tomkinson and coworkers, have synthesized specific inhibitors of DNA ligases for potential therapeutic use. These inhibitors can cause rapid onset of cell death and are potentially useful in the treatment of cancer (15, 16).

Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease (APEI)

As detailed above, APEI is important in both nuclear and mitochondrial BER. Knock out of APEI in mice caused early embryonic lethality between implantation and day 5.5 post-implantation (E5.5), and an inability to derive mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) (17). To overcome this problem, Mitra and co-workers created a floxed allele of human APE1 (hAPE1) in which the both mouse alleles of APE1 were deleted (18). While the human transgene was insufficient to allow normal embryogenesis and a viable mouse, the researchers were able to isolate MEF from day E9.5 embryos. Expression of Cre recombinase in these MEF caused loss of hAPEI expression and rapid onset of apoptosis. Loss of APEI was shown to result in rapid onset of caspase 3 activation and apoptosis (18). It has been demonstrated that APEI also has a crucial role in redox signaling, further protecting cells from oxidative stress. Subsequent work has suggested that the amino acid Cys-65 is vital for the redox activity of APEI. The C65S variant of APEI causes reduced protein folding and altered mitochondrial localization (resulting in the accumulation of APEI in the intermembrane space rather than allowing protein-mediated import of APEI into the matrix) (19). Taken collectively, these results indicate that mitochondrial localization after oxidative stress is essential for cell survival (19).

DNA polymerase gamma (Pol γ)

Mutations in DNA polymerase gamma (POL γ) might be expected to have profound cellular and organismal effects. Surprisingly, mutations in human POLG are quite common (20) and are associated with several dominant and recessive genetic diseases causing ataxia, liver failure, seizures and blindness (20). It is also interesting to note that mice expressing a variant of PolG lacking the 3’ ↓ 5’ exonuclease proof reading function accumulate mitochondrial mutations and age prematurely (21, 22). Mitochondrial-targeted catalase can partially restore cardiac function and longevity to these mice (23). Taken together, these studies suggest that an increase in mtDNA mutations can result in an elevated production of ROS, which if mitigated by catalase, can result in longer life span. Additional work is needed to directly test this hypothesis, as previous studies with the Pol γ exo deficient mice did not reveal evidence of free radical damage (22).

EFFECT OF DNA DAMAGING AGENTS ON MTDNA

Oxidants

5.1.1. Oxidants cause more mitochondrial than nuclear DNA damage

Based on the premise that damaged templates cannot participate in an amplification reaction (24), my group developed a novel quantitative PCR assay for mtDNA damage and found that mtDNA was highly susceptible to damage by hydrogen peroxide (5, 25). Since hydrogen peroxide is exceedingly more reactive in the presence of divalent metal ions such as Fe2+, one explanation for this increased damage is the fact that mitochondria are important for FeS cluster biogenesis. These studies also showed that brief hydrogen peroxide exposure causes mtDNA lesions that are rapidly repaired, but protracted exposures results in persistent mtDNA damage and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (5, 25). These findings raised questions about the fate of the ROS-damaged mitochondrial genomes and the subsequent rates of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation.

5.1.2. Oxidants cause loss of mtDNA and mitochondrial function

Wilson et al. showed that persistent mitochondrial damage causes rapid degradation of the mitochondrial genome (26, 27). Simultaneously, we showed that hydrogen peroxide induces significant persistent mtDNA damage, a 60% loss of mtDNA from cells, and a subsequent loss of more than 60% of mitochondrial function within eight hours of the exposure (28). Surprisingly, treatment with the alkylating agent, methylmethanesulfonate (MMS), at concentrations that cause an equal number of mtDNA lesions as hydrogen peroxide, did not induce mtDNA loss or loss of mitochondrial function (28). These studies indicate that oxidant stress causes not just mtDNA damage but also loss of mitochondrial DNA, perhaps through autophagy or mitophagy (discussed in more detail below).

5.2. UV-induced and bulky lesions

As described above (section 3.2.), NER is absent from mitochondria. As a result, damage that is normally repaired in the nuclear genome by NER persists in the mitochondrial genome. This is particularly important from the perspective of environmental exposures, because many environmental genotoxins cause damage that is only repaired by NER (29, 30). Examples of such damage include photodimers, “bulky” DNA chemical adducts, and a small but potentially important subset of oxidative DNA damage. Some drugs, such as cisplatin, also cause DNA damage that is repaired by NER. Photodimers (including 6,4-photoproducts and cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers) are caused by exposure to ultraviolet B and C wavelength ultraviolet radiation that has sufficient energy to cause the dimerization of adjacent DNA bases. “Bulky” adducts are formed by the binding of activated metabolites of various organic pollutants, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons present in smoke and mycotoxins such as aflatoxin that often contaminate food items. Because these compounds are highly lipophilic, they often concentrate in mitochondria (31). Finally, a subset of the oxidative DNA damage that occurs at high levels in mtDNA (section 5.1.) is repaired in the nucleus by NER (32–34). Thus, all organisms are constantly faced with genetic insults that produce high levels of mtDNA damage that cannot be repaired.

Some nuclear DNA polymerases bypass common DNA lesions (translesion synthesis) to confer cellular ‘tolerance’ to unrepaired damage. The sole replicative mtDNA polymerase, DNA Pol γ, appears to have very little translesion synthesis capacity; photodimers and bulky lesions are powerful blocks to mtDNA replication in vitro (35–37). There is also strong biochemical evidence that similar forms of damage inhibit transcription by the mitochondrial RNA polymerase (30, 38). Thus, common environmental exposures result in high levels of irreparable mtDNA damage and arrested DNA and RNA synthesis in vitro. These characteristics suggest a critical vulnerability for the mitochondrial genome. However, the mitochondrial genome can be replicated and degraded (via autophagy) without cell division, and its high copy number per cell may confer buffering. In fact, the mitochondrial population within a cell can be shuffled via fusion and fission of the organelles. What then might the effects of irreparable mtDNA damage be?

We carried out experiments in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans to test the effect of persistent mtDNA damage, using a protocol that resulted in the accumulation of high levels of mtDNA photoproducts while allowing for the repair of most of the simultaneously induced nDNA damage (39, 40). This damage was generated by UV exposure in the first of the four larval stages of the organism. The irradiation resulted in lower levels of mtDNA (i.e., lower mtDNA copy number per cell), lower levels of ATP, lower levels of oxygen consumption, and dose-responsive inhibition of larval development (39, 40). The mRNA levels for mtDNA-encoded proteins were initially lower than in unexposed nematodes, but later rebounded (40). Persistent mtDNA damage generated by three exposures to 10 J/m2 UVC radiation, which resulted in mild and reversible developmental delay (39), led to dopaminergic neurodegeneration in young adults (41). The mRNA levels for the mtDNA POLG were increased strongly and autophagy was induced, suggesting a compensatory response (39, 40). Genetic deficiencies in mitochondrial fusion and autophagy enhanced the larval arrest observed with UV irradiation (39), and mitochondrial fusion, fission, and autophagy genes were also required for the slow disappearance of photoproducts from mtDNA (39). It is important to note that these photoproducts are not removed by a DNA repair process but are depleted by loss of mtDNA during mitophagy. Genetic deficiencies in fission, while not exacerbating larval arrest, did cause a greater depletion of mtDNA after photoproduct formation (42). This work suggests that, in a process facilitated by mitochondrial fusion and fission, autophagy functions to remove mitochondria containing irreparably damaged mtDNAs. It also implies that mitochondrial fusion is particularly protective, at least in the short term, in the context of damaged mtDNA (42, 43). The longer-term effects of persistent mtDNA damage, especially in the context of genetic deficiencies, is yet to be determined, as is the question of whether damaged mtDNAs are targeted for autophagic removal or simply are cleared as a result of normal or increased autophagy-mediated removal of mitochondria. Regardless of the answer, the results discussed here highlight the fact that human genetic variation in the processes of autophagy and mitochondrial dynamics may sensitize some individuals to exposure to environmental genotoxicants.

It is important to note that work in mammalian cell culture has also demonstrated the slow removal of photoproducts (24, 44), coupled to mitochondrial degradation and induction of autophagy (44), as well as effects of irreparable mtDNA damage on mitochondrial function (45). Interestingly, we did not observe major effects of photoproduct damage on mitochondrial function (44), potentially due to the much higher mtDNA copy number present in the mammalian cells compared to cells in C. elegans. On the other hand, Marullo et al. (46), who investigated the effect of cisplatin exposure in cell culture, were able to attribute a significant portion of the cellular toxicity to mitochondrial toxicity resulting from inhibition of mitochondrial protein synthesis and resultant production of ROS. The extent of these effects varied by cell type (46). The potential involvement of the recently-reported mitochondrial-derived vesicle (47) and transcellular (48) mechanisms of mitophagy in responding to irreparable mtDNA damage is not yet clear. Overall, the nematode and mammalian model systems are consistent in showing that levels of irreparable damage slowly decrease, but that the mechanistic consequences of such damage are likely to depend on the cell type.

Similarly, the long-term in vivo effects of irreparable mtDNA damage remain unclear. There is biochemical evidence that photodimers, metabolites of the air pollution constituent benzo(a)pyrene, and acrolein may all result in mtDNA mutations (35–37). This is important because mtDNA mutations cause approximately 200 known diseases affecting at least 1/10,000 people (49, 50), but the origin of those mutations is not understood. To our knowledge, in vivo experiments designed to test whether exposure to such agents can result in heritable mtDNA mutations have not been carried out and are an important area of future research.

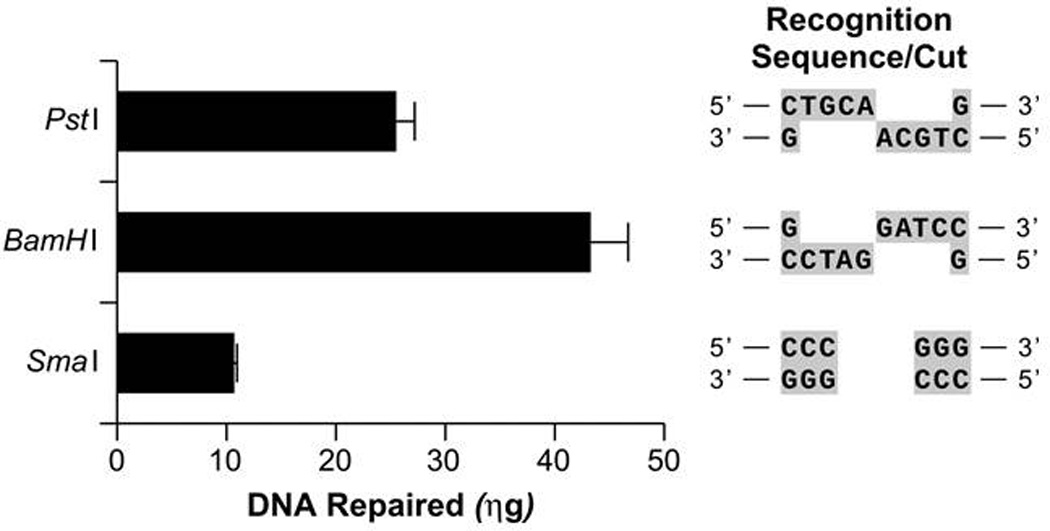

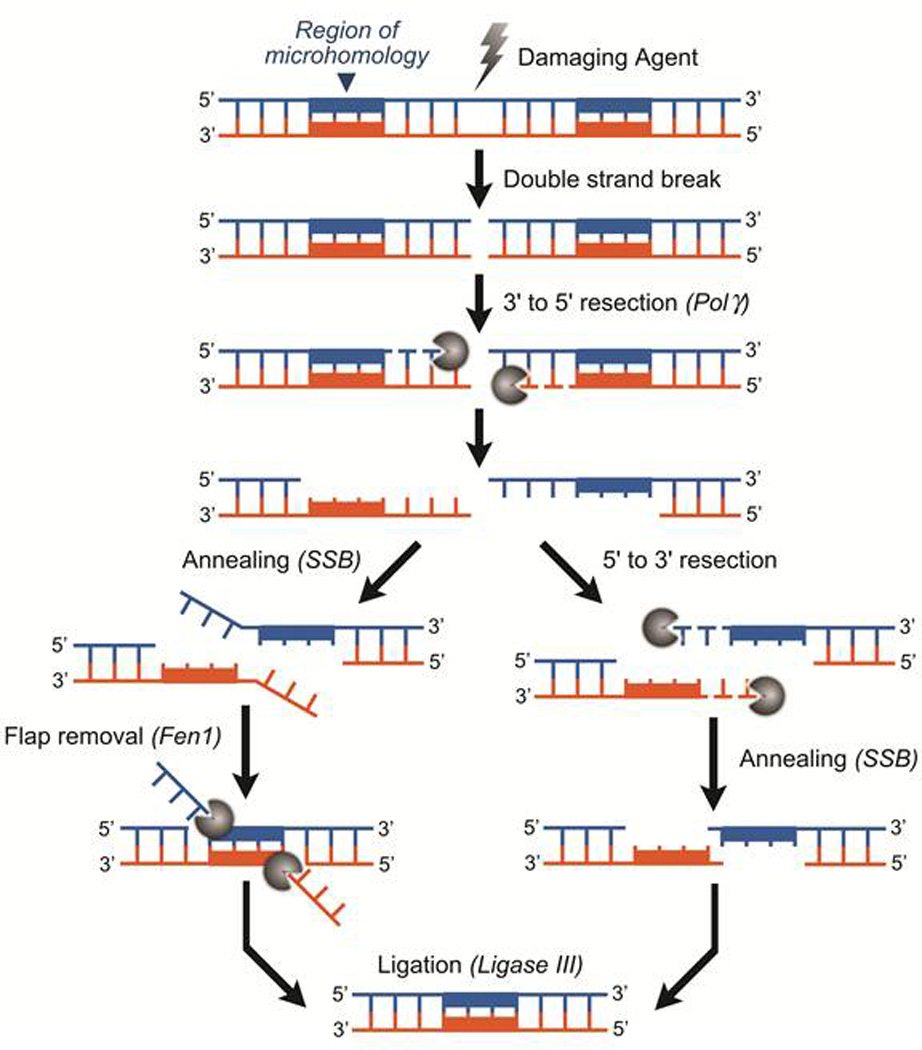

5.3. DNA double-strand breaks

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) occur endogenously following assault by ROS, errors in DNA metabolism by nucleases and topoisomerases, or arrest of DNA replication forks. These lesions are also produced by exogenous agents such as ionizing radiation and certain chemotherapeutic drugs. The repair of DSBs in the nuclear genome has been well characterized and is accomplished by three pathways: homologous recombination (HR); non-homologous end joining (NHEJ); and microhomology-mediated end-joining (MMEJ, also known as alternative NHEJ) (reviewed in (51) and (52)). HR is essential for the maintenance of mtDNA integrity in plants, fungi and yeast, and although mammalian mitochondria are capable of DSB repair, its relevance in vivo remains unclear. mtDNA recombination following the induction of DSBs by a mitochondrial-targeted restriction endonuclease was noted in mice (53). Using a mitoplast system, we detected DSB repair in vitro. This DSB repair results in the loss of nucleotides surrounding and including the original lesion (Figure 4). Consistent with previous literature, we found that several repair products contain short stretches of homology flanking the deleted portions of DNA, implicating MMEJ in mtDNA repair and associating DSB repair with the formation of mtDNA deletions (Figure 5) which are strikingly similar to those observed in patients with mitochondrial disorders and certain cancers. This microhomology mediated pathway might explain how such deletions occur in mtDNA and by definition cause loss of essential genetic information.

Figure. 4.

Human mitoplast protein extracts catalyze the repair of various DSBs. pUC-19 plasmid DNA was treated with PstI, BamHI or SmaI restriction endonuclease to create a single DSB containing either a 3’ or 5’ overhang or a blunt end respectively. The recognition sequences and cut sites of the endonucleases are given in the right panel. The DSB-DNA molecules (0.3.3 µg) were incubated with mitochondrial extracts from GM847 human fibroblasts and subsequent DSB repair was detected using QPCR and measured using Picogreen analysis. The subsequent fluorescence values were compared to those obtained using varying concentrations of the PCR standard DNA which were subjected to QPCR concurrently with the DSB-DNA repair samples and the concentration of DNA repaired by mitochondrial extracts calculated.

Figure. 5.

Mitochondrial DSB Repair. The schematic represents our proposed mechanism for microhomology-mediated, DNA deletion-generating mitochondrial DSB repair. DSB-DNA undergoes 3’ to 5’ resection by PolG to reveal flanking DNA repeats. 3’ to 5’ resection must also be accompanied by a 5’ to 3’ exonuclease or a flap endonuclease activity to remove the remaining single strand regions of DNA. Synapsis occurs following resection, potentially by mitochondrial Single Strand Binding protein (mtSSB). The DNA repeats are annealed and strands ligated by LIG3, the sole mitochondrial ligase. The result is a circular molecule containing the resected genetic material flanked by direct repeats. This type of mtDNA repair would cause a loss of expression of critical mitochondrial encoded proteins resulting in a drastic decrease in oxidative phosphorylation, as is seen in patients harboring deleted portions of their mtDNA genome.

It is yet to be determined if the mtDNA DSB repair observed in vitro represents the primary mechanism by which DSBs in mammalian mitochondrial genomes are resolved in vivo. Current data suggests that mitochondrial DSB repair pathways are unable to effectively repair excessive damage. In human and rodent cell lines, mtDNA molecules challenged with DSB induction via mitochondria-directed endonucleases are completely and irreversibly degraded (54). Similar induction of DSBs in a mouse model harboring heteroplasmic mtDNA results in rapid degradation of cleaved mtDNA molecules by endogenous nucleases, followed by replication of the uncleaved mtDNA haplotype (55). Such depletion of mtDNA along with increased mitochondrial replication following the accumulation of DSBs has been demonstrated in cardiac, liver and skeletal muscle cells (55–57).

Recent data provides evidence that mitophagy may also be important in responding to mtDNA DSBs, as for photoproducts (described above), serving as a clearance mechanism when mtDNA DSBs overwhelm repair mechanisms. Rapid declines in mtDNA copy number are followed by a reduction of the mitochondrial components of the electron transport chain such as cytochrome c oxidase (COX) (53), decreasing mitochondrial respiratory activity and contributing to ROS production and membrane depolarization. The organelle handles these insults via mechanisms that include fusion, fission and mitophagy (39). As described above, fusion provides genetic complementation by combining intact mitochondria with organelles containing mutated or depleted mtDNA (58), and fission provides a means of segregating mitochondria with excessive damage that are destined for destruction. Such mitochondria are removed via autophagy or mitophagy (see Figure 1). Chen et al. report that disrupting mitophagy in mitofusin 2-deficient mice results in the accumulation of mtDNA DSBs and linearized mtDNA products (57). This data supports the theory that unrepaired mtDNA containing DSBs are cleared via mitophagy. Failure of cells to remove mtDNA DSB products via mitophagy is sufficient to cause cardiomyopathy (57). The mechanism by which mtDNA DSBs cause end-organ damage is yet to be established. However, it is plausible that the loss of functional respiratory chain complexes secondary to mtDNA deletions and depletion is a factor. Dysfunctional oxidative phosphorylation along with differential susceptibility to oxidative stress has been shown to contribute to an increase in free radicals leading to cellular death and end-organ damage (59, 60). This pathway could be induced by the accumulation of broken mtDNA. Additionally, apoptosis is induced by persistent single-strand DNA breaks in the mitochondrial genome (8). A similar mechanism involving apoptosis may be initiated by the presence of mtDNA DSBs, leading to end-organ damage.

6. MtDNA DAMAGE/LOSS IN HUMAN DISEASE

Since oxidative damage to mitochondria and mtDNA causes functional decline of oxidative phosphorylation, it might be expected that organs with large demand for mitochondrially-generated energy would be most affected by mtDNA damage. For example, Kearns-Sayre Syndrome (KSS) is a neurodegenerative disorder resulting in such impairments as chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia, cardiac conduction abnormalities, cerebellar ataxia and proximal muscle weakness, affecting organs involving high oxidative stress and/or high metabolic demands. Patients with KSS have been found to have spontaneously inherited mtDNA deletions (similar to those observed in the MMEJ pathway discussed above) and resulting cellular energy deficits that are postulated to be induced by oxidative mtDNA damage. Several other human pathologies have been associated with free radical damage and subsequent mtDNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunction (reviewed in (61)). These diseases include diabetes mellitus, liver diseases (e.g. hemochromatosis), cardiovascular disease (e.g. atherosclerosis) and several neurodegenerative diseases (e.g. Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s Disease, Friedreich’s Ataxia and Huntington’s disease). In fact, multiple studies have linked human diseases associated with oxidative stress and loss of mitochondrial function to mtDNA damage (55, 59–67). Castro et al. showed that liver biopsies of aged rhesus monkeys have increased oxidative stress and greater mtDNA damage as compared to their younger counterparts, coupling end-organ pathology to oxidation-induced mtDNA damage (67). A mechanism similar to that proposed for aging (10, 68–71) is thought to occur in alcoholic hepatitis. A correlation of oxidative stress and reduced mitochondrial function also exists in neurological disorders (45, 68–70, 72–74) and lung injury (75). It will be of particular importance to test the combined effects of deficiencies in mtDNA homeostasis processes such as those described above with environmental exposures; for example, Stumpf and Copeland recently showed that MMS exposure leads to increases in mtDNA mutagenesis in the presence of human disease variants of PolG(76).

7. SUMMARY

This review highlights the effect of mitochondrial DNA damage on cellular respiration, survival and disease. Data discussed here suggests that mitochondrial DNA damage can trigger select removal of dysfunctional mitochondrial through fission and subsequent mitophagy, and loss of mitochondrial DNA repair can cause cell death, tissue pathology and organismic decline associated with aging and other degenerative diseases. Future work is needed to increase our understanding of the important cross-talk between mitochondrial DNA damage and other cellular events (4).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by PA CURE Funds (BVH) and a NIH Grant, R01ES017540 (JNM).

REFERENCES

- 1.Holt IJ, Reyes A. Human mitochondrial DNA replication. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2012;4(12):a012971. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012971. pii(12) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kazak L, Reyes A, Holt IJ. Minimizing the damage: repair pathways keep mitochondrial DNA intact. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2012;13(10):659–671. doi: 10.1038/nrm3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexeyev M, Shokolenko I, Wilson G, LeDoux S. The maintenance of mitochondrial DNA integrity--critical analysis and update. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2013;5(5):a012641. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaughnessy DT, McAllister K, Worth L, Haugen AC, Meyer JN, Domann FE, et al. Mitochondria, Energetics, Epigenetics, and Cellular Responses to Stress. Environmental health perspectives. 2014 doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yakes FM, Van Houten B. Mitochondrial DNA damage is more extensive and persists longer than nuclear DNA damage in human cells following oxidative stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(2):514–519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Longley MJ, Prasad R, Srivastava DK, Wilson SH, Copeland WC. Identification of 5'-deoxyribose phosphate lyase activity in human DNA polymerase gamma and its role in mitochondrial base excision repair in vitro. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(21):12244–12248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szczesny B, Tann AW, Longley MJ, Copeland WC, Mitra S. Long patch base excision repair in mammalian mitochondrial genomes. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(39):26349–26356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803491200. PMCID: 2546560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tann AW, Boldogh I, Meiss G, Qian W, Van Houten B, Mitra S, et al. Apoptosis Induced by Persistent Single-strand Breaks in Mitochondrial Genome: CRITICAL ROLE OF EXOG (5'-EXO/ENDONUCLEASE) IN THEIR REPAIR. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286(37):31975–31983. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.215715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simsek D, Furda A, Gao Y, Artus J, Brunet E, Hadjantonakis AK, et al. Crucial role for DNA ligase III in mitochondria but not in Xrcc1-dependent repair. Nature. 2011;471(7337):245–248. doi: 10.1038/nature09794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandavilli BS, Santos JH, Van Houten B. Mitochondrial DNA repair and aging. Mutation research. 2002;509(1–2):127–151. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cymerman IA, Chung I, Beckmann BM, Bujnicki JM, Meiss G. EXOG, a novel paralog of Endonuclease G in higher eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(4):1369–1379. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1169. PMCID: 2275078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szczesny B, Olah G, Walker DK, Volpi E, Rasmussen BB, Szabo C, et al. Deficiency in repair of the mitochondrial genome sensitizes proliferating myoblasts to oxidative damage. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e75201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao Y, Katyal S, Lee Y, Zhao J, Rehg JE, Russell HR, et al. DNA ligase III is critical for mtDNA integrity but not Xrcc1-mediated nuclear DNA repair. Nature. 2011;471(7337):240–244. doi: 10.1038/nature09773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shokolenko IN, Fayzulin RZ, Katyal S, McKinnon PJ, Wilson GL, Alexeyev MF. Mitochondrial DNA ligase is dispensable for the viability of cultured cells but essential for mtDNA maintenance. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288(37):26594–26605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.472977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomkinson AE, Howes TR, Wiest NE. DNA ligases as therapeutic targets. Translational cancer research. 2013;2(3):1219. pii(3) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomkinson AE, Sallmyr A. Structure and function of the DNA ligases encoded by the mammalian LIG3 gene. Gene. 2013;531(2):150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.08.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xanthoudakis S, Smeyne RJ, Wallace JD, Curran T. The redox/DNA repair protein, Ref-1, is essential for early embryonic development in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(17):8919–8923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Izumi T, Brown DB, Naidu CV, Bhakat KK, Macinnes MA, Saito H, et al. Two essential but distinct functions of the mammalian abasic endonuclease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(16):5739–5743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500986102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vascotto C, Bisetto E, Li M, Zeef LA, D'Ambrosio C, Domenis R, et al. Knock-in reconstitution studies reveal an unexpected role of Cys-65 in regulating APE1/Ref-1 subcellular trafficking and function. Molecular biology of the cell. 2011;22(20):3887–3901. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-05-0391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Copeland WC. Defects in mitochondrial DNA replication and human disease. Critical reviews in biochemistry and molecular biology. 2012;47(1):64–74. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2011.632763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kujoth GC, Hiona A, Pugh TD, Someya S, Panzer K, Wohlgemuth SE, et al. Mitochondrial DNA mutations, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in mammalian aging. Science. 2005;309(5733):481–484. doi: 10.1126/science.1112125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trifunovic A, Wredenberg A, Falkenberg M, Spelbrink JN, Rovio AT, Bruder CE, et al. Premature ageing in mice expressing defective mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nature. 2004;429(6990):417–423. doi: 10.1038/nature02517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dai DF, Chen T, Wanagat J, Laflamme M, Marcinek DJ, Emond MJ, et al. Age-dependent cardiomyopathy in mitochondrial mutator mice is attenuated by overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria. Aging Cell. 2010;9(4):536–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00581.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalinowski DP, Illenye S, Van Houten B. Analysis of DNA damage and repair in murine leukemia L1210 cells using a quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20(13):3485–3494. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.13.3485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santos JH, Hunakova L, Chen Y, Bortner C, Van Houten B. Cell sorting experiments link persistent mitochondrial DNA damage with loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and apoptotic cell death. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278(3):1728–1734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208752200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shokolenko I, Venediktova N, Bochkareva A, Wilson GL, Alexeyev MF. Oxidative stress induces degradation of mitochondrial DNA. Nucleic acids research. 2009;37(8):2539–2548. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shokolenko IN, Wilson GL, Alexeyev MF. Persistent damage induces mitochondrial DNA degradation. DNA repair. 2013;12(7):488–499. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Furda AM, Marrangoni AM, Lokshin A, Van Houten B. Oxidants and not alkylating agents induce rapid mtDNA loss and mitochondrial dysfunction. DNA repair. 2012;11(8):684–692. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyer JN, Leung MC, Rooney JP, Sendoel A, Hengartner MO, Kisby GE, et al. Mitochondria as a target of environmental toxicants. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2013;134(1):1–17. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cline SD. Mitochondrial DNA damage and its consequences for mitochondrial gene expression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1819(9–10):979–991. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.06.002. PMCID: 3412069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Backer JM, Weinstein IB. Interaction of benzo(a)pyrene and its dihydrodiol-epoxide derivative with nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in C3H10T 1/2 cell cultures. Cancer Res. 1982;42(7):2764–2769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brooks PJ. The 8,5'-cyclopurine-2'-deoxynucleosides: candidate neurodegenerative DNA lesions in xeroderma pigmentosum, and unique probes of transcription and nucleotide excision repair. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008;7(7):1168–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeong YC, Nakamura J, Upton PB, Swenberg JA. Pyrimido(1,2-a)-purin-10(3H)-one, M(1)G, is less prone to artifact than base oxidation. Nucleic Acids Research. 2005;33(19):6426–6434. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson KA, Fink SP, Marnett LJ. Repair of propanodeoxyguanosine by nucleotide excision repair in vivo and in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(17):11434–11438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kasiviswanathan R, Minko IG, Lloyd RS, Copeland WC. Translesion synthesis past acrolein-derived DNA adducts by human mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(20):14247–14255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.458802. PMCID: 3656281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graziewicz MA, Sayer JM, Jerina DM, Copeland WC. Nucleotide incorporation by human DNA polymerase gamma opposite benzo(a)pyrene and benzo(c)phenanthrene diol epoxide adducts of deoxyguanosine and deoxyadenosine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(1):397–405. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kasiviswanathan R, Gustafson MA, Copeland WC, Meyer JN. Human mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma exhibits potential for bypass and mutagenesis at UV-induced cyclobutane thymine dimers. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(12):9222–9229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.306852. PMCID: 3308766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cline SD, Lodeiro MF, Marnett LJ, Cameron CE, Arnold JJ. Arrest of human mitochondrial RNA polymerase transcription by the biological aldehyde adduct of DNA, M1dG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(21):7546–7557. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq656. PMCID: 2995074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bess AS, Crocker TL, Ryde IT, Meyer JN. Mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy aid in removal of persistent mitochondrial DNA damage in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40(16):7916–7931. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leung MC, Rooney JP, Ryde IT, Bernal AJ, Bess AS, Crocker TL, et al. Effects of early life exposure to ultraviolet C radiation on mitochondrial DNA content, transcription, ATP production, and oxygen consumption in developing Caenorhabditis elegans. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;14:9. doi: 10.1186/2050-6511-14-9. PMCID: 3621653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gonzalez-Hunt CP, Leung MC, Bodhicharla RK, McKeever MG, Arrant AE, Margillo KM, et al. Exposure to Mitochondrial Genotoxins and Dopaminergic Neurodegeneration in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e114459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114459. PMCID: 4259338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bess AS, Leung MC, Ryde IT, Rooney JP, Hinton DE, Meyer JN. Effects of mutations in mitochondrial dynamics-related genes on the mitochondrial response to ultraviolet C radiation in developing Caenorhabditis elegans. Worm. 2013;2(1):e23763. doi: 10.4161/worm.23763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meyer JN, Bess AS. Involvement of autophagy and mitochondrial dynamics in determining the fate and effects of irreparable mitochondrial DNA damage. Autophagy. 2012;8(12):1822–1823. doi: 10.4161/auto.21741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bess AS, Ryde IT, Hinton DE, Meyer JN. UVC-induced mitochondrial degradation via autophagy correlates with mtDNA damage removal in primary human fibroblasts. Journal of biochemical and molecular toxicology. 2013;27(1):28–41. doi: 10.1002/jbt.21440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Acevedo-Torres K, Berrios L, Rosario N, Dufault V, Skatchkov S, Eaton MJ, et al. Mitochondrial DNA damage is a hallmark of chemically induced and the R6/2 transgenic model of Huntington's disease. DNA repair. 2009;8(1):126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marullo R, Werner E, Degtyareva N, Moore B, Altavilla G, Ramalingam SS, et al. Cisplatin Induces a Mitochondrial-ROS Response That Contributes to Cytotoxicity Depending on Mitochondrial Redox Status and Bioenergetic Functions. PLoS One. 2013;8(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McLelland GL, Soubannier V, Chen CX, McBride HM, Fon EA. Parkin and PINK1 function in a vesicular trafficking pathway regulating mitochondrial quality control. The EMBO journal. 2014;33(4):282–295. doi: 10.1002/embj.201385902. PMCID: 3989637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davis CH, Kim KY, Bushong EA, Mills EA, Boassa D, Shih T, et al. Transcellular degradation of axonal mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(26):9633–9638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404651111. PMCID: 4084443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holt IJ. Zen and the art of mitochondrial DNA maintenance. Trends Genet. 2010;26(3):103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chinnery PF, Elliott HR, Hudson G, Samuels DC, Relton CL. Epigenetics, epidemiology and mitochondrial DNA diseases. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(1):177–187. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr232. PMCID: 3304530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haber JE. Partners and pathways repairing a double-strand break. Trends Genet. 2000;16(6):259–264. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stracker TH, Petrini JH. The MRE11 complex: starting from the ends. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12(2):90–103. doi: 10.1038/nrm3047. PMCID: 3905242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bacman SR, Williams SL, Moraes CT. Intra- and inter-molecular recombination of mitochondrial DNA after in vivo induction of multiple double-strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(13):4218–4226. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp348. PMCID: 2715231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kukat A, Kukat C, Brocher J, Schafer I, Krohne G, Trounce IA, et al. Generation of rho0 cells utilizing a mitochondrially targeted restriction endonuclease and comparative analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(7):e44. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn124. PMCID: 2367725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bacman SR, Williams SL, Garcia S, Moraes CT. Organ-specific shifts in mtDNA heteroplasmy following systemic delivery of a mitochondria-targeted restriction endonuclease. Gene therapy. 2010;17(6):713–720. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bacman SR, Williams SL, Hernandez D, Moraes CT. Modulating mtDNA heteroplasmy by mitochondria-targeted restriction endonucleases in a 'differential multiple cleavage-site' model. Gene Ther. 2007;14(18):1309–1318. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302981. PMCID: 2771437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen Y, Sparks M, Bhandari P, Matkovich SJ, Dorn GW., 2nd Mitochondrial Genome Linearization Is a Causative Factor for Cardiomyopathy in Mice and Drosophila. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013 doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nakada K, Inoue K, Ono T, Isobe K, Ogura A, Goto YI, et al. Inter-mitochondrial complementation: Mitochondria-specific system preventing mice from expression of disease phenotypes by mutant mtDNA. Nat Med. 2001;7(8):934–940. doi: 10.1038/90976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Diaz F, Enriquez JA, Moraes CT. Cells lacking Rieske iron-sulfur protein have a reactive oxygen species-associated decrease in respiratory complexes I and IV. Molecular and cellular biology. 2012;32(2):415–429. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06051-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Diaz F, Garcia S, Padgett KR, Moraes CT. A defect in the mitochondrial complex III, but not complex IV, triggers early ROS-dependent damage in defined brain regions. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(23):5066–5077. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Van Houten B, Woshner V, Santos JH. Role of mitochondrial DNA in toxic responses to oxidative stress. DNA repair. 2006;5(2):145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bacman SR, Williams SL, Pinto M, Peralta S, Moraes CT. Specific elimination of mutant mitochondrial genomes in patient-derived cells by mitoTALENs. Nature medicine. 2013;19(9):1111–1113. doi: 10.1038/nm.3261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pickrell AM, Pinto M, Moraes CT. Mouse models of Parkinson's disease associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. Molecular and cellular neurosciences. 2013;55:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pinto M, Pickrell AM, Fukui H, Moraes CT. Mitochondrial DNA damage in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease decreases amyloid beta plaque formation. Neurobiology of aging. 2013;34(10):2399–2407. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang X, Moraes CT. Increases in mitochondrial biogenesis impair carcinogenesis at multiple levels. Molecular oncology. 2011;5(5):399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang X, Pickrell AM, Rossi SG, Pinto M, Dillon LM, Hida A, et al. Transient systemic mtDNA damage leads to muscle wasting by reducing the satellite cell pool. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(19):3976–3986. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang X, Pickrell AM, Zimmers TA, Moraes CT. Increase in muscle mitochondrial biogenesis does not prevent muscle loss but increased tumor size in a mouse model of acute cancer-induced cachexia. PloS one. 2012;7(3):e33426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Castro Mdel R, Suarez E, Kraiselburd E, Isidro A, Paz J, Ferder L, et al. Aging increases mitochondrial DNA damage and oxidative stress in liver of rhesus monkeys. Experimental gerontology. 2012;47(1):29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vogel KS, Perez M, Momand JR, Acevedo-Torres K, Hildreth K, Garcia RA, et al. Age-related instability in spermatogenic cell nuclear and mitochondrial DNA obtained from Apex1 heterozygous mice. Molecular reproduction and development. 2011;78(12):906–919. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mandavilli BS, Ali SF, Van Houten B. DNA damage in brain mitochondria caused by aging and MPTP treatment. Brain research. 2000;885(1):45–52. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02926-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Maslov AY, Ganapathi S, Westerhof M, Quispe-Tintaya W, White RR, Van Houten B, et al. DNA damage in normally and prematurely aged mice. Aging Cell. 2013;12(3):467–477. doi: 10.1111/acel.12071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Siddiqui A, Rivera-Sanchez S, Castro Mdel R, Acevedo-Torres K, Rane A, Torres-Ramos CA, et al. Mitochondrial DNA damage is associated with reduced mitochondrial bioenergetics in Huntington's disease. Free radical biology & medicine. 2012;53(7):1478–1488. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pascucci B, Lemma T, Iorio E, Giovannini S, Vaz B, Iavarone I, et al. An altered redox balance mediates the hypersensitivity of Cockayne syndrome primary fibroblasts to oxidative stress. Aging Cell. 2012;11(3):520–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Trushina E, Dyer RB, Badger JD, 2nd, Ure D, Eide L, Tran DD, et al. Mutant huntingtin impairs axonal trafficking in mammalian neurons in vivo and in vitro. Molecular and cellular biology. 2004;24(18):8195–8209. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8195-8209.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cho HY, van Houten B, Wang X, Miller-DeGraff L, Fostel J, Gladwell W, et al. Targeted deletion of nrf2 impairs lung development and oxidant injury in neonatal mice. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17(8):1066–1082. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4288. PMCID: 3423869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stumpf JD, Copeland WC. MMS exposure promotes increased MtDNA mutagenesis in the presence of replication-defective disease-associated DNA polymerase gamma variants. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(10):e1004748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004748. PMCID: 4207668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Copeland WC, Longley MJ. DNA2 resolves expanding flap in mitochondrial base excision repair. Mol Cell. 2008;32(4):457–458. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.007. PMCID: 3967838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]