Abstract

Long intergenic noncoding RNAs (lincRNAs) can regulate the transcription of inflammatory genes and thus may represent a new group of inflammatory mediators with a potential pathogenic role in inflammatory diseases. Here, our genome-wide transcriptomic data show that TNF-α stimulation caused up-regulation of 171 lincRNAs and down-regulation of 196 lincRNAs in murine intestinal epithelial cells in culture. One of the up-regulated lincRNAs, lincRNA-Cox2, is an early-responsive lincRNA induced by TNF-α through activation of the NF-ĸB signaling pathway. Knockdown of lincRNA-Cox2 resulted in reprogramming of the gene expression profile in intestinal epithelial cells in response to TNF-α stimulation. Specifically, lincRNA-Cox2 silencing significantly (P < 0.05) enhanced the transcription of Il12b, a secondary late-responsive gene induced by TNF-α. Mechanistically, lincRNA-Cox2 promoted the recruitment of the Mi-2/nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (Mi-2/NuRD) repressor complex to the Il12b promoter region. Recruitment of the Mi-2/NuRD complex was associated with decreased H3K27 acetylation and increased H3K27 dimethylation at the Il12b promoter region, which might contribute to Il12b trans-suppression by lincRNA-Cox2. Thus, our data demonstrate a novel mechanism of epigenetic modulation by lincRNA-Cox2 on Il12b transcription, supporting an important role for lincRNAs in the regulation of intestinal epithelial inflammatory responses.—Tong, Q., Gong, A.-Y., Zhang, X.-T., Lin, C., Ma, S., Chen, J., Hu, G., Chen, X.-M. LincRNA-Cox2 modulates TNF-α–induced transcription of Il12b gene in intestinal epithelial cells through regulation of Mi-2/NuRD-mediated epigenetic histone modifications.

Keywords: LincRNAs, Il12b, Mi-2/NuRD complex, histone modifications, intestinal epithelium

Intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) lining the gastrointestinal mucosal surface not only function as a physical barrier to maintain mucosal integrity, but they also participate in the regulation of mucosal inflammatory reactions during microbial infection (1). IECs can recognize, process, and present antigen; produce a myriad of signaling molecules; and directly affect immune cell proliferation and differentiation (2). Their anatomic and functional abnormalities, such as increased permeability and abnormalities in IEC–immune cell interactions, can induce an overwhelming immune response, leading to intestinal inflammation. A persistent inflammatory state is a major pathologic hallmark for many intestinal diseases, including inflammatory bowel diseases, typified by Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis (3).

Cytokines control multiple aspects of the inflammatory response at the gastrointestinal mucosal surface. The imbalance between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines that occurs in inflammatory bowel diseases impedes the resolution of inflammation and instead leads to disease perpetuation and tissue destruction (4). Recent immunologic evidence shows that overexpression of proinflammation cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-12b, plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases (5). Genome-wide association studies have revealed that a variant of the Il12b gene confers genetic risk for developing Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. As with many other proinflammatory cytokines, IL-12b not only elicits intestinal inflammation but also protects the host against microbial invasion (6). Targeting these proinflammatory cytokines with monoclonal antibodies (e.g., ustekinumab and briakinumab) has emerged as a new and effective therapy.

Although only ∼1.2% of the human genome encodes mRNAs (generally referred as protein-coding genes), it is becoming increasingly apparent that most of the human genome is transcribed into non–protein-coding RNAs (ncRNAs). Long intergenic noncoding RNAs (lincRNAs; >200 nucleotides in length) have recently emerged as a class of key regulators of mammalian gene expression. Initial findings indicate that thousands of lincRNAs exist in the vertebrate genome, and their structures are evolutionarily conservative, suggesting that they may function in mammals. Many research efforts on the pathologic role of ncRNAs in inflammatory intestinal diseases have been focused on these short ncRNAs, such as microRNAs and PIWI-interacting RNAs (7). A potential role for lincRNAs in the regulation of IEC inflammatory responses has not been explored.

It has been reported that lincRNAs regulate gene expression via guiding chromatin-modifying complexes to specific genomic loci (8). Of more than 6000 lincRNAs, lincRNA-Cox2 is one of the better characterized lincRNAs. The lincRNA-Cox2 gene is proximal to the prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (Ptgs2/Cox2) gene, although they do not overlap, and is activated through TLR signaling in macrophages (9). It has been reported that lincRNA-Cox2 could mediate transcription of distinct classes of immune genes in the inflammatory response. It serves as both repressor and activator of inflammatory genes through physical interactions with nuclear ribonucleoprotein A/B and A2/B1 in macrophages (9).

In this study, we show that murine IECs displayed significant alterations in the lincRNA expression profile following TNF-α stimulation. LincRNA-Cox2, one of the up-regulated lincRNAs, may function as an important regulator for the transcription of many inflammatory genes in IECs. Specifically, induction of lincRNA-Cox2 promotes the recruitment of the Mi-2/nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (Mi-2/NuRD) repressor complex to the Il12b promoter region, resulting in trans-suppression of the Il12b gene. Our data demonstrate a novel mechanism of epigenetic modulation by lincRNA-Cox2 on transcription of the Il12b gene, supporting an important role for lincRNAs in the regulation of IEC inflammatory responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and TNF-α treatment

Mouse recombinant TNF-α was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). The murine IEC cell line (IEC4.1) was a kind gift from Dr. Pingchang Yang (McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada) and cultured in DMEM (Mediatech, Manassas, VA, USA) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 50 µg/ml gentamicin, and 1 ng/ml epidermal growth factor. IEC4.1 cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105/ml cells and, 16 h later, were moved to a medium with serum free for 2 h. TNF-α (10 ng/ml) was added to stimulate the cells for 4 h.

Real-time quantitative PCR

RNA was extracted using TRI reagent and treated with the DNA-freekit (Ambion, Grand Island, NY, USA) to remove any remaining DNA. Quantified RNA (500 ng) was reverse-transcribed using T100 thermal cyclers (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). For quantitative analysis of mRNA expression, comparative real-time PCR was performed using the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The sequences for the amplification of mouse Il-12b were as follows: 5′-TGTGACACGCCTGAAGAAGAT-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCAGAGTCTCGCCTCCTTTGT-3′ (reverse). The sequences for the amplification of mouse lincRNA-Cox2 were as follows: 5′-AAGGAAGCTTGGCGTTGTGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAGAGGTGAGGAGTCTTATG-3′ (reverse). The primer sequences for the amplification of the gene for mouse β-actin were as follows: 5′-TGGTGGGAATGGGTCAGAA-3′ (forward); 5′-TCTCCATGTCGTCCCAGTTG-3′ (reverse). Real-time PCR was performed in triplicate.

Small interfering RNAs and transfection

For gene silencing, the small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes for mouse lincRNA-Cox2 were synthesized using Integrated DNA Technologies. The siRNA sequences targeting lincRNA-Cox2 were as follows: sense, 5′-GCCCUAAUAAGUGGGUUGUUU-3′; antisense, 5′-ACAACCCACUUAUUAGGGCUU-3′. The siRNA duplexes for mouse Mi-2β (sc-37954) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The nonspecific scrambled siRNA sequence UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUUU was used for the control. Cells were treated with siRNAs (final concentration, 25 nM) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and were harvested 24 h after siRNA treatment. For lincRNA-Cox2 overexpression, lincRNA-Cox2 cDNA was amplified through PCR, inserted into the expression vector to generate lincRNA-Cox2, and subsequently sequenced. According to the manufacturer’s protocol, IEC4.1 cells were transfected with plasmid DNA using Lipofectamine 2000. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to determine the significant alteration of each target gene.

Cell lysate preparation and Western blot

IEC4.1 cells were harvested and washed twice in PBS. Whole-cell extracts were prepared using the whole cell extract buffer [20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, pH 7.4, 0.2 M NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM DTT, and cocktail protease inhibitor; Roche, Basel, Switzerland]. For preparation of nuclear extracts, cell pellets were resuspended in 1 ml lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and cocktail protease inhibitor) per 107 cells. Nuclei were collected by centrifugation and washed with lysis buffer devoid of Nonidet P-40. After centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in nuclei lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 400 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and cocktail protease inhibitor). The nuclei lysates were diluted 10-fold in the whole cell extract buffer and centrifuged to obtain the nuclear fraction. Cell lysates were then loaded in an 8–15% SDS-PAGE gel to separate proteins and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Antibodies to actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), p65 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and histone H3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) were used for detection.

Agilent microarray analysis

The LS Science Agilent SurePrint G3 Mouse Gene Expression Microarray (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and service to process the samples were applied to genome-wide analysis. In brief, IEC4.1 cells were treated with a lincRNA-Cox2 siRNA or the control siRNA for 24 h and cultured for an additional 4 h in the presence or absence of TNF-α (10 ng/ml). Experiments were performed in triplicate. Total RNAs (n = 3 for each group) were prepared with the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Ambion). The quality of isolated RNAs was verified by an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer profile. A mixture of equal amounts of total RNAs from each group was used as the reference pool. A total of 2 µg RNA from each sample was then labeled with the Agilent Gene Expression Hybridization Kit (Agilent p/n 5188-5242). After hybridization, the slides were scanned with the Agilent Microarray Scanner (Agilent p/n G2505C), and quantified signals were extracted and analyzed by using the Agilent Feature Extraction Software, in accordance with the MIAME (Minimum Information About a Microarray Experiment) guidelines.

Luciferase reporter constructs and luciferase assay

The lincRNA-Cox2 promoter sequence containing the IĸB binding site-1 was cloned into the multiple cloning site of the pGL3 Basic Luciferase vector (Ambion). The empty vector was used as a control. We then transfected cultured cells with each reporter construct. Luciferase activity was measured 24 h later and normalized to the control β-galactosidase level.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed as described previously (10). Briefly, IEC4.1 cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes, collected in ice-cold PBS, and resuspended in an SDS lysis buffer. Genomic DNA was then sheared to lengths ranging from 200 to 1000 bp by sonication. One percent of the cell extracts was taken as input, and the rest of the extracts was incubated with either anti-p65 mAb (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Mi-2β mAb (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-acetylation of histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9ac; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), anti-acetylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27ac; Abcam), anti-dimethylation of histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9me2), anti-dimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27me2; Cell Signaling Technologies), anti-trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3; Cell Signaling Technologies), anti-trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9me3; Upstate Biotechnology, Waltham, MA, USA), and anti-trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3; Cell Signaling Technologies), anti-H3K4me3 Ab (Cell Signaling Technologies), anti-H3K9me3 Ab (Upstate Biotechnology, Waltham MA, USA), anti-H3K27me3 Ab (Cell Signaling Technologies), or control IgG overnight at 4°C, followed by precipitation with protein G-agarose beads. The immunoprecipitates were sequentially washed once with a low-salt buffer, once with a high-salt buffer, once with an LiCl buffer, and twice with a Tris buffer. The DNA–protein complex was eluted, and proteins were then digested with proteinase K for 1 h at 45°C. The DNA was detected by real-time quantitative PCR analysis. ChIP primers for the NF-κB binding site regions of mouse lincRNA-Cox2 gene promoter were: site 1 (−2.9 to −3.1) (forward, 5′-TGGTGGGTAGGGTTGTGGA-3′ and reverse, 5′-TGAACACACTGGGAAACAAGC-3′); and site 2 (−9.0 to −9.2) (forward, 5′-ACTTATGCGTGGTGGTCAG-3′ and reverse, 5′-TTGGTCCAGTTATTGGCTG-3′); site 3 (−10.4 to −10.6) (forward, 5′-ACAAGGGAGGAAAGCCCAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCCCACACTTCAGTCTTCAT-3′). ChIP primers for mouse Il-12b gene promoter were: (proximal, −0.6 to −0.8) (forward, 5′-AATCTACACCGCCCGAAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCTTCTCCATTCCTGTCCCT-3′); (distal, −2.6 to −2.8) (forward, 5′-CTCCCTCTCT CCCTTTCTTCATTT-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCTTCTCTCTCCAGATGACTCCAT-3′).

RNA immunoprecipitation

Cross-linking RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) was performed as described previously (11, 12). All buffers used in this study contained RNase inhibitor. Nuclei from cells were isolated and used for chromatin fragmentation. After immunoprecipitation with anti–Mi-2β and IgG control antibodies, the beads were washed, and RNA was eluted and precipitated by ethanol. The precipitated RNA pellets were resuspended in nuclease-free water. An aliquot of RNA was used for a cDNA synthesis reaction and quantitative PCR analysis. The primer set for mouse lincRNA-Cox2 was 5′-AAGGAAGCTTGGCGTTGTGA-3′ and 5′-GAGAGGTGAGGAGTCTTATG-3′.

Chromatin isolation by RNA purification

Chromatin isolation by RNA purification (ChIRP) was performed as described previously (13). IEC4.1 cells were cross-linked with 1% glutaraldehyde, and the reaction was quenched in 125 mM glycine. The cell pellet was resuspended in nuclear lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors and RNase inhibitors and subjected to lysis by sonicating for 25 cycles on the Bioruptor. Chromatin was hybridized with the respective biotin-labeled probe sets and incubated at 37°C for 4 h. The biotin–probe–chromatin complexes then were pulled down with streptavidin magnetic beads, washed, eluted by proteinase K, and subjected to either DNase I or RNase A treatment. Recovered RNA and DNA were analyzed by quantitative PCR. The sequences for the biotin-labeled probes (3′ biotin) were as follows: lincRNA-Cox2_ChIRP1, 5′-CTCATATTCCACACCTGGGA-3′; lincRNA-Cox2_ChIRP2, 5′-ATAACAACCCACTTATTAGG-3′; lincRNA-Cox2_ChIRP3, 5′-CCACTCTTCTTCACCCTTTT-3′; lincRNA-Cox2_ChIRP4, 5′-TTCCTTAGTTCCTTGTGTAG-3′; lincRNA-Cox2_ChIRP5, 5′-TTTCAGGGCTGGCCAGTAAG-3′; lincRNA-Cox2_ChIRP6, 5′-CCTTGCTCTCTTTCAAATTC-3′. LACZ_ChIRP1, 5′-TTCAGACGGCAAACGACTGT-3′; LACZ_ChIRP2, 5′-TGATGCTCGTGACGGTTAAC-3′; LACZ_ChIRP3, 5′-TCAGTTGCTGTTGACTGTAG-3′. LACZ_ChIRP4, 5′- CCAGTGAATCCGTAATCATG-3′; LACZ_ChIRP5, 5′-AATGTGAGCGAGTAACAACC-3′; and LACZ_ChIRP6, 5′-GTAGCCAGCTTTCATCAACA-3′.

Injection of TNF-α in mice and isolation of small intestinal epithelium

The C57BL/6J mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were used and approved by the Creighton University Biosafety and Institutional Animal Care and Use committees (Protocol 0960). Animals received treatment of TNF-α (R&D Systems; 2.5 µg/30 g body weight in 200 µl of saline) by intraperitoneal injection, as reported previously (14). Small intestinal epithelium from the mice was isolated as reported previously (15). Total RNA from the intestinal epithelium was extracted for PCR analysis.

Statistical analysis

All values are given as means ± se. Means of groups were from at least 3 independent experiments and were compared with the Student t test (unpaired) or the ANOVA test when appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

TNF-α stimulation causes alterations in the expression profiles of protein-coding genes and genes coding lincRNAs in IEC4.1 cells

We first analyzed the gene expression profiles in IEC4.1 cells that were treated with the nonspecific control siRNA for 24 h, followed by an additional 4 h of incubation in the presence or absence of TNF-α. Agilent gene array analysis demonstrated that the expression levels of 688 protein-coding genes were increased by 2-fold or greater and 360 protein-coding genes decreased by 2-fold or greater in TNF-α–treated cells compared with the non–TNF-α–treated control (Supplemental Fig. 1 and ArrayExpress database E-MTAB-3904. Alterations in the expression profile of these protein-coding genes were consistent with results from previous studies (16). We found 171 putative lincRNAs whose expression levels were increased by 2-fold or greater and 196 lincRNAs decreased by 2-fold or greater in TNF-α–treated cells (Supplemental Fig. 1 and ArrayExpress database E-MTAB-3904). The top 25 up-regulated and top 25 down-regulated protein-coding genes and genes coding lincRNAs in TNF-α–treated cells are shown in Supplemental Fig. 1.

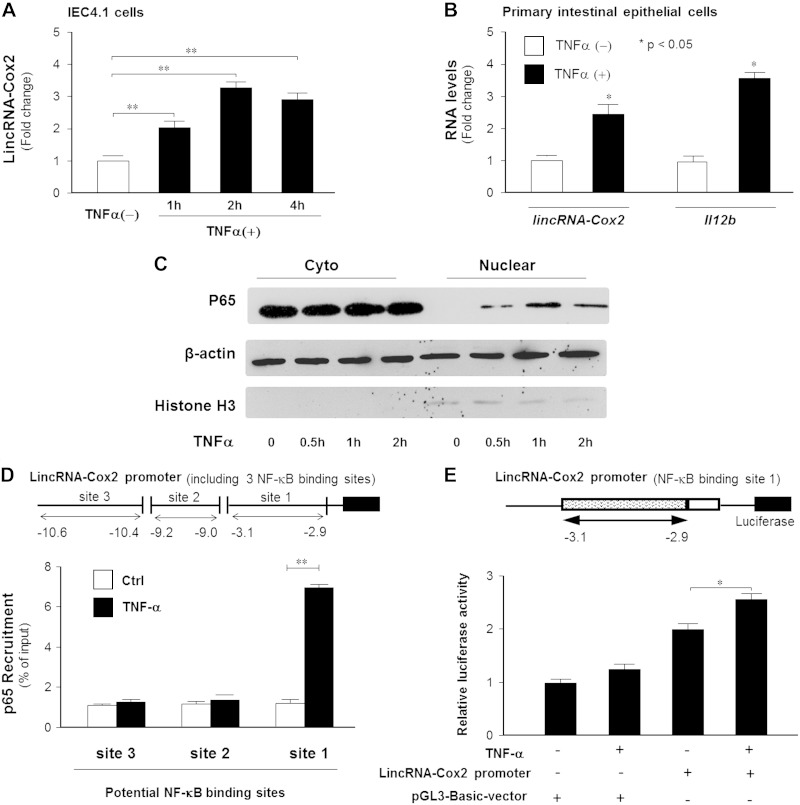

TNF-α induces lincRNA-Cox2 transcription through the NF-κB signaling pathway

Previous studies demonstrated that lincRNA-Cox2 modulates inflammatory reactions in macrophages (9). Although not within the top 25 up-regulated genes coding lincRNAs, lincRNA-Cox2 was significantly increased in cultured IECs after exposure to TNF-α, ranked as number 43 of the 171 up-regulated lincRNAs from the microarray analysis (ArrayExpress database E-MTAB-3904). We then tested the time course of lincRNA-Cox2 expression induced by TNF-α in IEC4.1 cells by quantitative real-time PCR. Consistent with previous data (9), we identified 3 splice variants of mouse lincRNA-Cox2 (accession numbers JX682706, JX682707, and JX682708) in IEC4.1 cells; consistently, variant 1 transcript (JX682706) was the most abundant lincRNA-Cox2 transcript in cells following TNF-α stimulation (data not shown). We then focused our analysis on variant 1 transcript. As shown in Fig. 1A, the expression level of lincRNA-Cox2 in IEC4.1 cells was significantly increased as early as 1 h after exposure to TNF-α and peaked at 2 h after TNF-α treatment (Fig. 1A). When TNF-α was injected to the abdominal cavity of mice, a significant increase in lincRNA-Cox2 levels was detected in the intestinal epithelium isolated at 2 and 4 h after TNF-α administration (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

TNF-α triggers lincRNA-Cox2 transcription through the NF-ĸB signaling pathway. A) Kinetics of lincRNA-Cox2 expression induced by TNF-α. IEC4.1 cells were exposed to TNF-α for up to 4 h. Expression levels of lincRNA-Cox2 were quantified by real-time PCR. B) LincRNA-Cox2 expression induced by TNF-α in vivo. Small intestinal epithelium was isolated from mice at 2 h after TNF-α administration. Expression levels of lincRNA-Cox2 and Il12b (as a positive control gene) were quantified by real-time PCR. C) Activation of NF-ĸB signaling in IEC4.1 cells in response to TNF-α stimulation. Cells were exposed to TNF-α for up to 2 h, and nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were isolated, followed by Western blot analysis for NF-ĸB subunit p65. Actin and H3 were also blotted for control. D) Binding of p65 to lincRNA-Cox2 promoter induced by TNF-α. IEC4.1 cells were exposed to TNF-α for 4 h, followed by ChIP assay using anti-p65 and PCR primers covering 3 different regions of the lincRNA-Cox2 promoter. E) Luciferase reporter assay demonstrating TNF-α–stimulated transcription associated with the lincRNA-Cox2 promoter. Cells were transfected with the luciferase reporter with the lincRNA-Cox2 promoter for 24 h, followed by measurement of luciferase activity. Data represent means ± se from 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

One of the key intracellular signaling pathways activated by TNF-α to trigger gene transcription is the NF-ĸB signaling pathway (17). We then tested whether TNF-α induces lincRNA-Cox2 transcription in IECs through the NF-ĸB signaling pathway. Activation of NF-ĸB signaling in IEC4.1 cells in response to TNF-α stimulation was evident by nuclear translocation of the NF-ĸB subunit p65 (Fig. 1C). Based on TFSEARCH (http://www.cbrc.jp/research/db/TFSEARCH.html) and MOTIF (http://motif.genome.jp/) database searches (18, 19), there are 3 potential NF-ĸB binding sites in the promoter region of the lincRNA-Cox2 gene. Using an antibody against p65 and PCR primers covering each potential NF-ĸB binding site, we performed a ChIP assay to test the direct binding of p65 to the lincRNA-Cox2 promoter region. As shown in Fig. 1D, a significant enrichment of p65 was detected to the proximal binding site 1 region of the lincRNA-Cox2 promoter in cells following TNF-α stimulation. We then cloned the promoter with the site 1 region of the lincRNA-Cox2 gene and inserted it into the pGL3-luciferase reporter vector (Fig. 1E). TNF-α stimulation increased luciferase activity in cells transfected with the luciferase reporter construct that encompassed the binding site for p65 at the site 1 region of the lincRNA-Cox2 gene (Fig. 1E). The above data indicate that lincRNA-Cox2 is an early NF-ĸB–responsive gene in IECs and that TNF-α induces lincRNA-Cox2 transcription through the NF-ĸB signaling pathway.

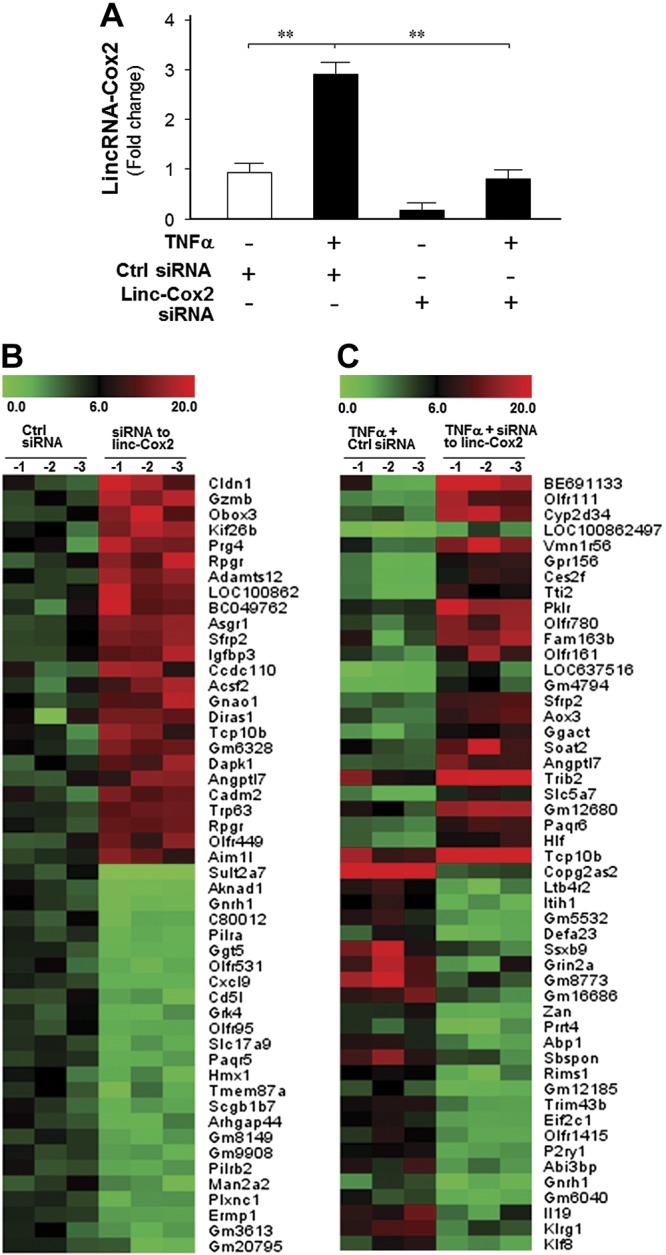

LincRNA-Cox2 mediates both activation and repression of protein-coding genes in IECs

To determine the impact of lincRNA-Cox2 induction on the TNF-α–induced inflammatory response in IECs, we designed specific siRNAs to knockdown lincRNA-Cox2 in IEC4.1 cells, as evidenced by real-time PCR in Fig. 2A. We then performed analysis using the Gene Expression Microarray on IEC4.1 cells that were treated with a lincRNA-Cox2 siRNA in the presence or absence of TNF-α. A nonspecific siRNA was used as the siRNA control. Cells were first treated with the siRNA for 24 h, followed by exposure to TNF-α for 4 h.

Figure 2.

LincRNA-Cox2 mediates both activation and repression of protein-coding genes. A) Knockdown of lincRNA-Cox2 by siRNA. Cells were treated by designed siRNAs specific to lincRNA-Cox2 for 24 h and cultured for an additional 4 h in the presence or absence of TNF-α. LincRNA-Cox2 expression levels were measured by real-time PCR. **P < 0.01. B, C) Effects of lincRNA-Cox2 knockdown on the expression profile of protein-coding genes. Cells were treated with lincRNA-Cox2 siRNA for 24 h and cultured for an additional 4 h in the presence or absence of TNF-α, followed by gene expression microarray analysis. The top 25 up-regulated and top 25 down-regulated protein-coding genes between lincRNA-Cox2 siRNA and control siRNA-treated cells (B), as well as between TNF-α–stimulated cells treated with lincRNA-Cox2 siRNA and control siRNA (C), are shown in the heatmaps.

Our analysis revealed 87 protein-coding genes whose expression levels were increased by 2-fold or greater and 50 genes decreased by 2-fold or greater in cells after lincRNA-Cox2 siRNA treatment for 24 h in the absence of TNF-α compared with cells treated with the nonspecific control siRNA (ArrayExpress database E-MTAB-3904). A total of 661 protein-coding genes’ expression levels increased significantly and 339 genes’ expression levels decreased significantly in cells treated with lincRNA-Cox2 siRNA followed by exposure to TNF-α for 4 h compared with the cells treated with the nonspecific control siRNA followed by TNF-α stimulation (ArrayExpress database E-MTAB-3904). The top 25 up-regulated and top 25 down-regulated protein-coding genes in lincRNA-Cox2 knockdown IECs that were either stimulated with TNF-α or unstimulated are shown in Fig. 2B and C. Whereas most of these altered genes are associated with cell metabolism or differentiation, some of them are important to inflammatory responses, including Il12b and Il10. An enhanced expression level of Il12b (ranked number 49 of the 661 enhanced genes) and a significant inhibition of Il10 expression (ranked number 161 of the 339 suppressed genes) were observed in cells treated with lincRNA-Cox2 siRNA followed by exposure to TNF-α for 4 h compared with the cells treated with the control siRNA followed by TNF-α stimulation. Silencing of lincRNA-Cox2 did not alter expression of its neighboring gene Ptgs2 (Cox2) (ArrayExpress database E-MTAB-3904).

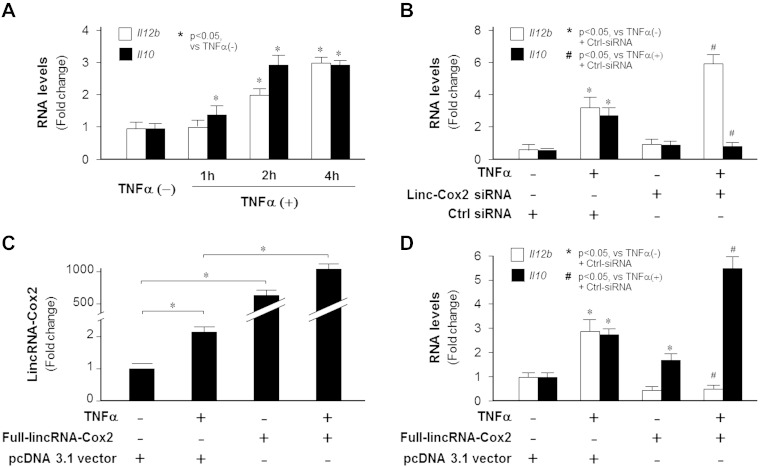

We then focused on the inhibitory effects of lincRNA-Cox2 on Il12b gene transcription. Il12b is a secondary late NF-ĸB–responsive gene, characterized by a delayed transcription of the gene in cells following NF-ĸB signaling activation (20). We first performed the time course analysis of Il12b expression level in IEC4.1 cells following TNF-α stimulation by quantitative real-time PCR. Consistent with results from previous studies (21), Il12b mRNA level was increased at 2 h after TNF-α stimulation (Fig. 3A), later than that of lincRNA-Cox2 induction (Fig. 1A). Consistent with our array results, an enhanced expression level of Il12b mRNA was observed in cells treated with lincRNA-Cox2 siRNA followed by exposure to TNF-α for 4 h compared with the cells treated with TNF-α alone (Fig. 3B). In addition, we further cloned the full-length lincRNA-Cox2 variant 1 transcript (9), and IEC4.1 cells transfected with the full-length lincRNA-Cox2 for 24 h displayed a marked increase in lincRNA-Cox2 level (Fig. 3C). As unphysiological as it may be, these cells showed a modest decrease in Il12b expression level (Fig. 3D). A significant inhibition of Il12b expression level induced by TNF-α was observed in cells expressing the full lincRNA-Cox2 (Fig. 3D). Accordingly, we detected an increase in Il10 expression level in cells following TNF-α stimulation (Fig. 3A). LincRNA-Cox2 siRNA attenuated TNF-α–induced Il10 expression (Fig 3B), and transfection of IEC4.1 cells with the full-length lincRNA-Cox2 enhanced Il10 expression in response to TNF-α (Fig. 3D). It is noteworthy that enforced expression of lincRNA-Cox2 increased Il10 expression in cells in the absence of TNF-α (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

LincRNA-Cox2 inhibits Il12b and promotes Il10 expression in IECs. A) Kinetics of Il12b and Il10 expression induced by TNF-α. IEC4.1 cells were exposed to TNF-α for up to 4 h. Expression levels of Il12b and Il10 were quantified by real-time PCR. B) Effects of lincRNA-Cox2 knockdown on Il12b and Il10 expression. Cells were treated with lincRNA-Cox2 siRNA for 24 h and cultured for an additional 4 h in the presence or absence of TNF-α, followed by real-time PCR. C, D) Effects of lincRNA-Cox2 overexpression on Il12b and Il10 expression. Cells were transfected with the pcDNA 3.1-lincRNA-Cox2 construct for 24 h and cultured for an additional 4 h in the presence or absence of TNF-α, followed by real-time PCR for lincRNA-Cox2 (C) or Il12b and Il10 (D). Data represent means ± se from 3 independent experiments.

NF-κB p65 is not a mediator for lincRNA-Cox2–mediated Il12b suppression

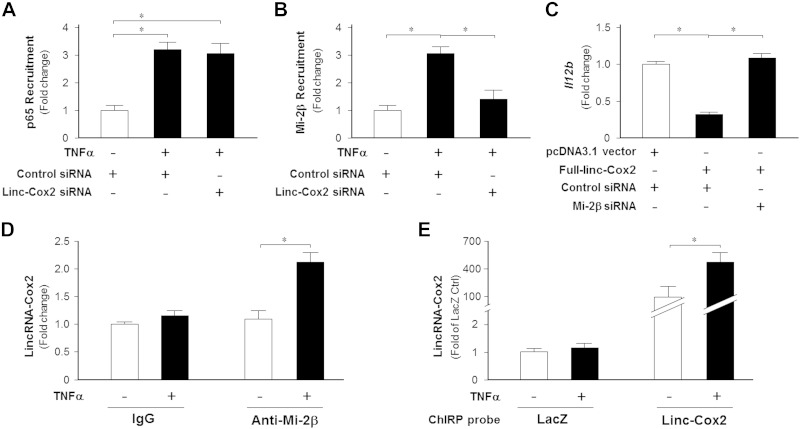

Il12b is an NF-ĸB–responsive gene in many cell types, and binding of NF-ĸB p65 to the promoter region of the gene is required for its transcription in response to TNF-α stimulation (22). We found that the lincRNA-Cox2 siRNA did not have a significant effect on the cytoplasmic activation of the NF-κB pathway triggered by extracellular stimuli (data not shown). To test the possibility that lincRNA-Cox2 may impact the binding of NF-ĸB p65 to the Il12b gene promoter to modulate its transcription, we measured the effects of lincRNA-Cox2 knockdown on TNF-α–induced p65 binding to the Il12b gene promoter by ChIP analysis. As shown in Fig. 4A, lincRNA-Cox2 siRNA showed no effects on the recruitment of NF-ĸB p65 to the Il12b gene promoter induced by TNF-α stimulation.

Figure 4.

The Mi-2/NuRD repression complex is recruited to the Il12b promoter region to regulate its transcription by lincRNA-Cox2. A, B) Effects of lincRNA-Cox2 knockdown on the recruitment of NF-ĸB p65 and Mi-2β to Il12b promoter induced by TNF-α. IEC4.1 cells were exposed to TNF-α for 4 h, followed by ChIP analysis using anti-p65 or anti–Mi-2β and PCR primers covering different regions of the Il12b promoter. C) Mi-2β knockdown attenuated the inhibitory effects of lincRNA-Cox2 overexpression on Il12b expression. IEC4.1 cells were cotransfected with the pcDNA 3.1-lincRNA-Cox2 construct and Mi-2β siRNA for 24 h, followed by PCR analysis of Il12b mRNA. D) Assembly of lincRNA-Cox2 to the Mi-2/NuRD complex induced by TNF-α. IEC4.1 cells were exposed to TNF-α for 4 h, followed by RIP analysis using anti–Mi-2β and PCR for lincRNA-Cox2. Anti-IgG was used as the control. LincRNA-Cox2 was detected in the Mi-2/NuRD complex in cells following TNF-α stimulation. E) Recruitment of lincRNA-Cox2 to the Il12b promoter region induced by TNF-α. IEC4.1 cells were exposed to TNF-α for 4 h, followed by ChIRP analysis using probes for lincRNA-Cox2 and PCR primers covering different regions of the Il12b promoter. Data represent means ± se from 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

Mi-2/NuRD repression complex is recruited to the Il12b promoter region to regulate its transcription by lincRNA-Cox2

Given the requirement of the Mi-2/NuRD repression complex for secondary gene transcription (23), we asked whether this complex is involved in lincRNA-Cox2–modulated trans-suppression of the Il12b gene in IECs in response to TNF-α stimulation. Consistent with results of previous reports (23), we detected an increased recruitment of the Mi-2/NuRD complex to the Il12b gene promoter in cells following TNF-α stimulation by ChIP analysis (Fig. 4B). Knockdown of lincRNA-Cox2 decreased TNF-α–induced recruitment of the Mi-2/NuRD complex to the Il12b gene promoter (Fig. 4B). Complementarily, knockdown of Mi-2β, a key component of the Mi-2/NuRD complex (24), attenuated the suppression of the Il12b gene induced by overexpressing lincRNA-Cox2 in IEC 4.1 cells (Fig. 4C), suggesting the involvement of Mi-2/NuRD complex recruitment in lincRNA-Cox2–mediated Il12b trans-suppression. We then asked whether there is a direct physical association between lincRNA-Cox2 and the Mi-2/NuRD complex. By RIP analysis, we detected the presence of lincRNA-Cox2 in the Mi-2/NuRD complex in cells following TNF-α stimulation (Fig. 4D). To further test whether lincRNA-Cox2 is recruited to the Il12b promoter, we performed ChIRP analysis, using a pool of tiling oligonucleotide probes with affinity specific to the lincRNA-Cox2 sequence and glutaraldehyde cross-linking for chromatin isolation. The DNA sequences of the chromatin immunoprecipitates were confirmed by real-time PCR using the PCR primer covering the Il12b promoter (upstream 0.6–0.8 kb of the transcription start site). We detected that lincRNA-Cox2 is recruited to the promoter region of the Il12b gene in cells following TNF-α stimulation (Fig. 4E).

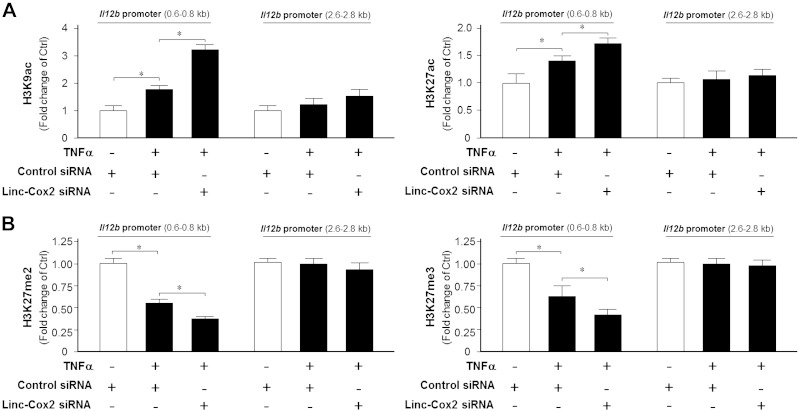

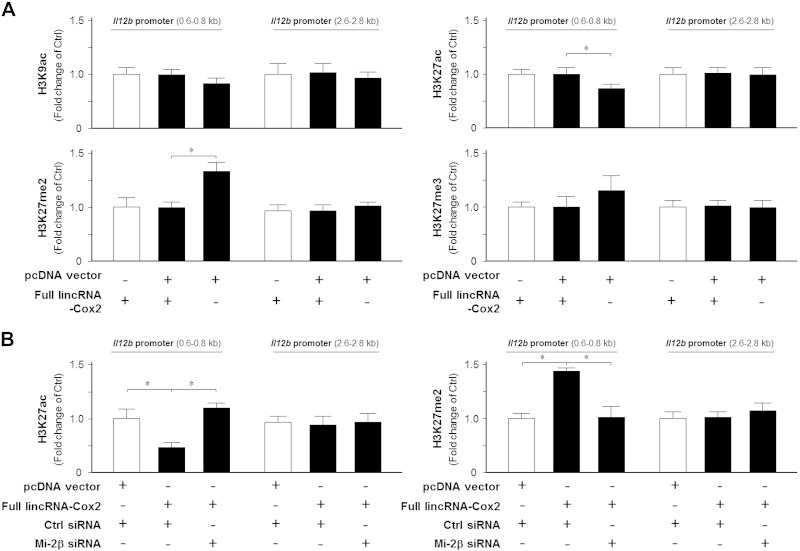

LincRNA-Cox2 promotes Mi-2/NuRD-mediated histone modifications to suppress Il12b transcription in IECs in response to TNF-α stimulation

It has been speculated that the chromatin of the secondary-responsive genes is packed tightly compared with the chromatin of early-primary genes (23). The recruitment of Mi-2/NuRD complex to secondary-responsive genes will promote chromatin remodeling through epigenetic mechanisms, such as histone modifications, resulting in transcriptional regulation of these genes (23, 25). Consistent with previous findings (26), we detected an increase of H3K9ac and H3K27ac within the Il12b promoter 0.6- to 0.8-kb region in cells following TNF-α stimulation (Fig. 5A). A decrease in H3K27me2 and H3H27me3 at the region was also observed in TNF-α–treated cells (Fig. 5B). Knockdown of lincRNA-Cox2 through siRNA resulted in an enhanced increase of H3K9ac and H3K27ac, as well as a further decrease of H3K27me2 and H3K27me3, within the promoter region in cells following TNF-α stimulation (Fig. 5 A, B). No changes in the H3K4me3 levels were detected in TNF-α–treated cells (Supplemental Fig. 2). Although a decrease of H3K9 methylations was detected in cells following TNF-α stimulation, siRNA to lincRNA-Cox2 showed no effects on TNF-α–induced H3K9 methylations (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Figure 5.

LincRNA-Cox2 promotes suppressive histone modifications in the Il12b promoter region induced by TNF-α. IEC4.1 cells were treated with lincRNA-Cox2 siRNA for 24 h and cultured for an additional 4 h in the presence or absence of TNF-α. Cells were then collected and applied for ChIP analysis for histone modifications associated with the Il12b promoter region. H3K9ac and H3K27ac associated with the Il12b promoter region are shown in A and methylations of H3K27 in B. Data represent means ± se from 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

Complementarily, overexpression of lincRNA-Cox2 decreased H3K27ac and increased H3K27me2 within the Il12b promoter 0.6- to 0.8-kb region in IEC4.1 cells (Fig. 6A). No significant alterations in H3K9ac and H3K27me3 were detected in cells overexpressing lincRNA-Cox2 (Fig. 6A). Knockdown of Mi-2β through siRNA attenuated the increase of H3K27ac and decrease of H3K27me2 induced by lincRNA-Cox2 overexpression (Fig. 6B). Moreover, knockdown Mi-2β further enhanced H3K27ac and inhibited the enrichment of H3K27me2 within the Il12b promoter 0.6- to 0.8-kb region in IEC4.1 cells induced by TNF-α stimulation (Supplemental Fig. 3). Taken together, the above data suggest that lincRNA-Cox2 promotes Mi-2/NuRD–mediated histone modifications to suppress Il12b transcription in IECs in response to TNF-α stimulation.

Figure 6.

LincRNA-Cox2 promotes TNF-α–mediated suppressive histone modifications in the Il12b promoter region in a Mi-2/NuRD complex–dependent manner. A) Overexpression of lincRNA-Cox2 on the suppressive histone modifications in the Il12b promoter region. IEC4.1 cells were transfected with the pcDNA 3.1-lincRNA-Cox2 construct for 24 h, followed by ChIP analysis for histone modifications associated with the Il12b promoter region. B) Knockdown of Mi-2β on lincRNA-Cox2–mediated histone modifications in the Il12b promoter region. IEC4.1 cells were cotransfected with the pcDNA 3.1-lincRNA-Cox2 construct and siRNA to Mi-2β for 24 h, followed by ChIP analysis for H3K27ac and H3K27me2 in the Il12b promoter region. Data represent means ± se from 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

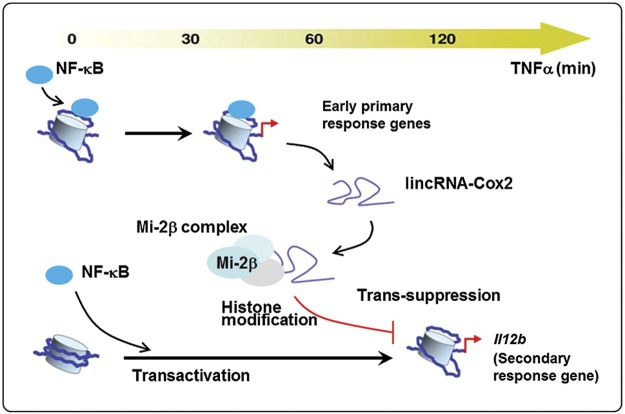

In this study, we provide evidence that TNF-α stimulation causes significant alterations in the expression profiles of protein-coding genes or genes coding lincRNAs in IECs in culture. One of the up-regulated lincRNAs, lincRNA-Cox2, is an early NF-ĸB–responsive gene in IECs following TNF-α stimulation. Functionally, lincRNA-Cox2 may be an important regulator for the transcription of many inflammatory genes. Specifically, lincRNA-Cox2 promotes the recruitment of the Mi-2/NuRD repressor complex to the promoter region of Il12b, a secondary late-responsive gene in IECs in response to TNF-α stimulation. Recruitment of the Mi-2/NuRD complex induced by lincRNA-Cox2 suppresses the transcription of the Il12b gene through epigenetic histone modifications. Thus, our data demonstrate a novel mechanism of epigenetic modulation by lincRNA-Cox2 on the transcription of the Il12b gene, supporting an important role for lincRNAs in the regulation of IEC inflammatory responses (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Model of lincRNA-Cox2 on transcription of the Il12b gene in IECs induced by TNF-α. LincRNA-Cox2 is an early NF-ĸB–responsive gene triggered by TNF-α stimulation. LincRNA-Cox2 is then assembled into the Mi-2/NuRD complex and subsequently recruited to the Il12b gene locus, resulting in trans-suppression through histone modification-mediated epigenetic mechanisms.

LincRNAs are a class of newly identified lncRNA molecules in the mammalian genome. Similar to mRNAs, their transcription in mammalian cells has been demonstrated to be tightly regulated and responsive to various extracellular stimuli (27). Accordingly, we observed significant alterations in the expression profiles for mRNAs and lincRNAs in cultured IECs following TNF-α stimulation. Although the transcriptional regulation of genes coding lincRNAs in response to extracellular stimuli is still less understood compared with protein-coding genes, many transcription factors may also control the transcription of the genes coding lincRNAs (28). In support of this concept, we found the transcriptional control of lincRNA-Cox2 gene through the promoter binding of NF-ĸB p65 in IECs following TNF-α stimulation.

Physiologically, lincRNAs may modulate the transcription of many genes in IECs either at the basal conditions or in response to extracellular stimuli. Knockdown of lincRNA-Cox2 resulted in significant alterations in the expression profile of protein-coding genes in cultured IEC4.1 cells in the absence of TNF-α. Furthermore, cells treated with siRNA to lincRNA-Cox2 displayed a different expression profile of protein-coding genes in response to TNF-α stimulation, with some genes further up-regulated and others down-regulated. Obviously, the involvement of lincRNA-Cox2 in the transcriptional regulation of protein-coding genes is gene specific and may involve different mechanisms. Notably, lincRNA-Cox2 is an early NF-ĸB–responsive gene. The trans-suppression of Il12b, a secondary late-responsive inflammatory gene, by lincRNA-Cox2 suggests to us that transcription of genes coding lincRNAs may provide inhibitory regulation to these late inflammatory genes, preventing an overreaction to inflammatory stimuli. Transcription of inflammatory genes in many cell types in response to extracellular stimuli, including IECs, is a dynamic process, with the acute proinflammatory genes activated earlier followed by these late proinflammatory genes and the anti-inflammatory genes (29). Therefore, induction of lincRNAs, in particular these early-responsive ones, may provide fine-tuning regulation to transcription of the late-responsive inflammatory genes.

Epigenetic histone modifications may account for the transcriptional suppression of the Il12b gene induced by lincRNA-Cox2. The late-responsive genes, such as Il12b, are usually tightly packed in the chromatin compared with the early-responsive genes (23). Promoter recruitment of the SWI/SNF complex has been reported to trigger the transcription of several late-responsive genes (30). In contrast, enrichment of the Mi-2/NuRD complex at the promoter region has been implicated in the transcriptional repression of the Il12b gene (23). The Mi-2/NuRD complex, an abundant deacetylase complex with a broad cellular and tissue distribution, contains multiple protein subunits, including the class I histone deacetylase, class II histone deacetylase and the Mi-2β protein (31). Besides histone deacetylation, the Mi-2/NuRD complex has also been implicated in promotion of H3K27 methylations (32, 33). A reduction of histone H3K27me3 was found in plants lacking the NuRD component, the chromatin remodeling factor EPP1 (enhanced photomorphogenic 1) PKL (34). In this study, we found increased H3K9ac and H3K27ac and decreased H3K27 methylations at the Il12b promoter region in IECs following TNF-α stimulation. Importantly, knockdown of either Mi-2β or lincRNA-Cox2 attenuated the associated histone modifications in the Il12b promoter region induced by TNF-α.

LincRNAs are versatile molecules that can interact physically with DNA, other RNAs, and proteins, either through nucleotide base pairing or via formation of structural domains generated by RNA folding. These properties endow lincRNAs with a versatile range of capabilities to modulate gene transcription that are only beginning to be appreciated. Data from this study indicate that lincRNA-Cox2 is required for the recruitment of the Mi-2/NuRD complex to the Il12b promoter region in cells in response to TNF-α stimulation. LincRNAs may function as scaffold molecules through their interactions with various RNA-binding proteins in the chromatin remodeling complexes (27). Indeed, lincRNA-Cox2 has been shown to interact with several RNA-binding proteins, including heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein A/B and A2/B1 (9). Because heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein A/B and A2/B1 function mainly to regulate the RNA stability and splicing of mRNA transcripts (35), such an interaction may have a global effect on gene transcription, but should not be gene specific. Therefore, they may not contribute to lincRNA-Cox2–induced Il12b trans-suppression. Alternatively, lincRNA-Cox2 may “guide” the initial recruitment of the Mi-2/NuRD complex to the Il12b gene locus. A genome-wide chromatin binding analysis for lincRNA-Cox2 can clarify this possibility.

In summary, our data demonstrate that murine IECs displayed significant alterations in lincRNA expression profile following TNF-α stimulation. Induction of lincRNA-Cox2 in response to TNF-α stimulation promotes the recruitment of the Mi-2/NuRD repressor complex to the Il12b promoter region, resulting in trans-suppression of the Il12b gene. Our findings suggest a new regulatory mechanism of epigenetic modulation on the transcription of the proinflammatory cytokine Il12b gene in IECs through the induction of lincRNA-Cox2. Further studies should investigate the regulatory function of lincRNAs in IEC inflammatory responses at physiologic conditions in vivo and explore the pathologic role of lincRNA dysregulation at various pathologic conditions, such as inflammatory bowel diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Barbara L. Bittner for assistance in writing the manuscript. This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grants AI095532 and AI116323 and by Creighton Cancer and Smoking Development Award LB595 (to X.-M.C.). This project was also supported by NIH National Center for Research Resources Grant G20RR024001. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- ChIRP

chromatin isolation by RNA purification

- H3K9ac

acetylation of histone H3 lysine 9

- H3K27ac

acetylation of histone H3 lysine 27

- H3K9me2

dimethylation of histone H3 lysine 9

- H3K9me3

trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 9

- H3K27me2

dimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27

- H3K27me3

trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27

- H3K4me3

trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4

- IEC

intestinal epithelial cell

- lincRNA

long intergenic noncoding RNA

- Mi-2/NuRD

Mi-2 nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase

- RIP

RNA immunoprecipitation

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mahida Y. R. (2004) Microbial-gut interactions in health and disease. Epithelial cell responses. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 18, 241–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheroutre H., Huang Y. (2013) Crosstalk between adaptive and innate immune cells leads to high quality immune protection at the mucosal borders. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 785, 43–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dharmani P., Chadee K. (2008) Biologic therapies against inflammatory bowel disease: a dysregulated immune system and the cross talk with gastrointestinal mucosa hold the key. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 1, 195–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pedersen J., Coskun M., Soendergaard C., Salem M., Nielsen O. H. (2014) Inflammatory pathways of importance for management of inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 64–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Z., Hinrichs D. J., Lu H., Chen H., Zhong W., Kolls J. K. (2007) After interleukin-12p40, are interleukin-23 and interleukin-17 the next therapeutic targets for inflammatory bowel disease? Int. Immunopharmacol. 7, 409–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danese S. (2012) New therapies for inflammatory bowel disease: from the bench to the bedside. Gut 61, 918–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pekow J. R., Kwon J. H. (2012) MicroRNAs in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 18, 187–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hung T., Chang H. Y. (2010) Long noncoding RNA in genome regulation: prospects and mechanisms. RNA Biol. 7, 582–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carpenter S., Aiello D., Atianand M. K., Ricci E. P., Gandhi P., Hall L. L., Byron M., Monks B., Henry-Bezy M., Lawrence J. B., O’Neill L. A., Moore M. J., Caffrey D. R., Fitzgerald K. A. (2013) A long noncoding RNA mediates both activation and repression of immune response genes. Science 341, 789–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das P. M., Ramachandran K., vanWert J., Singal R. (2004) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay. Biotechniques 37, 961–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis B. N., Hilyard A. C., Lagna G., Hata A. (2008) SMAD proteins control DROSHA-mediated microRNA maturation. Nature 454, 56–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki H. I., Yamagata K., Sugimoto K., Iwamoto T., Kato S., Miyazono K. (2009) Modulation of microRNA processing by p53. Nature 460, 529–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu C., Quinn J., Chang H. Y. (2012) Chromatin isolation by RNA purification (ChIRP). J. Vis. Exp. 25, 3912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bluthé R. M., Pawlowski M., Suarez S., Parnet P., Pittman Q., Kelley K. W., Dantzer R. (1994) Synergy between tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1 in the induction of sickness behavior in mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology 19, 197–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lantier L., Lacroix-Lamandé S., Potiron L., Metton C., Drouet F., Guesdon W., Gnahoui-David A., Le Vern Y., Deriaud E., Fenis A., Rabot S., Descamps A., Werts C., Laurent F. (2013) Intestinal CD103+ dendritic cells are key players in the innate immune control of Cryptosporidium parvum infection in neonatal mice. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murakami T., Mataki C., Nagao C., Umetani M., Wada Y., Ishii M., Tsutsumi S., Kohro T., Saiura A., Aburatani H., Hamakubo T., Kodama T. (2000) The gene expression profile of human umbilical vein endothelial cells stimulated by tumor necrosis factor alpha using DNA microarray analysis. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 7, 39–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He F., Peng J., Deng X. L., Yang L. F., Camara A. D., Omran A., Wang G. L., Wu L. W., Zhang C. L., Yin F. (2012) Mechanisms of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced leaks in intestine epithelial barrier. Cytokine 59, 264–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kast C., Wang M., Whiteway M. (2003) The ERK/MAPK pathway regulates the activity of the human tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 6787–6794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Musikacharoen T., Matsuguchi T., Kikuchi T., Yoshikai Y. (2001) NF-κB and STAT5 play important roles in the regulation of mouse Toll-like receptor 2 gene expression. J. Immunol. 166, 4516–4524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Natoli G. (2009) Control of NF-κB-dependent transcriptional responses by chromatin organization. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 1, a000224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berthier-Vergnes O., Bermond F., Flacher V., Massacrier C., Schmitt D., Péguet-Navarro J. (2005) TNF-α enhances phenotypic and functional maturation of human epidermal Langerhans cells and induces IL-12 p40 and IP-10/CXCL-10 production. FEBS Lett. 579, 3660–3668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geisel J., Brück J., Glocova I., Dengler K., Sinnberg T., Rothfuss O., Walter M., Schulze-Osthoff K., Röcken M., Ghoreschi K. (2014) Sulforaphane protects from T cell-mediated autoimmune disease by inhibition of IL-23 and IL-12 in dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 192, 3530–3539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramirez-Carrozzi V. R., Nazarian A. A., Li C. C., Gore S. L., Sridharan R., Imbalzano A. N., Smale S. T. (2006) Selective and antagonistic functions of SWI/SNF and Mi-2β nucleosome remodeling complexes during an inflammatory response. Genes Dev. 20, 282–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams C. J., Naito T., Arco P. G., Seavitt J. R., Cashman S. M., De Souza B., Qi X., Keables P., Von Andrian U. H., Georgopoulos K. (2004) The chromatin remodeler Mi-2beta is required for CD4 expression and T cell development. Immunity 20, 719–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhatt D. M., Pandya-Jones A., Tong A. J., Barozzi I., Lissner M. M., Natoli G., Black D. L., Smale S. T. (2012) Transcript dynamics of proinflammatory genes revealed by sequence analysis of subcellular RNA fractions. Cell 150, 279–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angrisano T., Pero R., Peluso S., Keller S., Sacchetti S., Bruni C. B., Chiariotti L., Lembo F. (2010) LPS-induced IL-8 activation in human intestinal epithelial cells is accompanied by specific histone H3 acetylation and methylation changes. BMC Microbiol. 10, 172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ulitsky I., Bartel D. P. (2013) LincRNAs: genomics, evolution, and mechanisms. Cell 154, 26–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheik Mohamed J., Gaughwin P. M., Lim B., Robson P., Lipovich L. (2010) Conserved long noncoding RNAs transcriptionally regulated by Oct4 and Nanog modulate pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. RNA 16, 324–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharif O., Bolshakov V. N., Raines S., Newham P., Perkins N. D. (2007) Transcriptional profiling of the LPS induced NF-κB response in macrophages. BMC Immunol. 8, 1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belandia B., Orford R. L., Hurst H. C., Parker M. G. (2002) Targeting of SWI/SNF chromatin remodelling complexes to estrogen-responsive genes. EMBO J. 21, 4094–4103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Denslow S. A., Wade P. A. (2007) The human Mi-2/NuRD complex and gene regulation. Oncogene 26, 5433–5438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reynolds N., Salmon-Divon M., Dvinge H., Hynes-Allen A., Balasooriya G., Leaford D., Behrens A., Bertone P., Hendrich B. (2012) NuRD-mediated deacetylation of H3K27 facilitates recruitment of polycomb repressive complex 2 to direct gene repression. EMBO J. 31, 593–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morey L., Brenner C., Fazi F., Villa R., Gutierrez A., Buschbeck M., Nervi C., Minucci S., Fuks F., Di Croce L. (2008) MBD3, a component of the NuRD complex, facilitates chromatin alteration and deposition of epigenetic marks. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 5912–5923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang H., Rider S. D. Jr., Henderson J. T., Fountain M., Chuang K., Kandachar V., Simons A., Edenberg H. J., Romero-Severson J., Muir W. M., Ogas J. (2008) The CHD3 remodeler PICKLE promotes trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 22637–22648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goodarzi H., Najafabadi H. S., Oikonomou P., Greco T. M., Fish L., Salavati R., Cristea I. M., Tavazoie S. (2012) Systematic discovery of structural elements governing stability of mammalian messenger RNAs. Nature 485, 264–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.