Abstract

Objective

To investigate factors influencing the adoption of kangaroo mother care in different contexts.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science and the World Health Organization’s regional databases, for studies on “kangaroo mother care” or “kangaroo care” or “skin-to-skin care” from 1 January 1960 to 19 August 2015, without language restrictions. We included programmatic reports and hand-searched references of published reviews and articles. Two independent reviewers screened articles and extracted data on carers, health system characteristics and contextual factors. We developed a conceptual model to analyse the integration of kangaroo mother care in health systems.

Findings

We screened 2875 studies and included 112 studies that contained qualitative data on implementation. Kangaroo mother care was applied in different ways in different contexts. The studies show that there are several barriers to implementing kangaroo mother care, including the need for time, social support, medical care and family acceptance. Barriers within health systems included organization, financing and service delivery. In the broad context, cultural norms influenced perceptions and the success of adoption.

Conclusion

Kangaroo mother care is a complex intervention that is behaviour driven and includes multiple elements. Success of implementation requires high user engagement and stakeholder involvement. Future research includes designing and testing models of specific interventions to improve uptake.

Résumé

Objectif

Étudier les facteurs qui influencent l'adoption de la méthode de la mère «kangourou» dans différents contextes.

Méthodes

Nous avons recherché dans PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science et les bases de données régionales de l'Organisation mondiale de la Santé des études sur la méthode de la mère «kangourou», les soins «kangourou» ou les soins peau contre peau du 1er janvier 1960 au 19 août 2015, sans restrictions de langues. Nous avons inclus des rapports programmatiques et des références, recherchées manuellement, d'études et d'articles publiés. Deux réviseurs indépendants ont examiné les articles et extrait des données sur les aidants, les caractéristiques des systèmes de santé et les facteurs contextuels. Nous avons élaboré un modèle conceptuel pour analyser l'intégration de la méthode de la mère «kangourou» dans les systèmes de santé.

Résultats

Nous avons examiné 2875 études et inclus 112 études contenant des données qualitatives sur la mise en œuvre. La méthode de la mère «kangourou» a été appliquée de différentes façons selon les contextes. Les études démontrent qu'il existe plusieurs obstacles à la mise en œuvre de la méthode de la mère «kangourou»: elle requiert du temps et un soutien social, et suppose des soins médicaux et une acceptation par les familles. Les obstacles inhérents aux systèmes de santé résidaient notamment dans l'organisation, le financement et la prestation de services. Dans l'ensemble, les normes culturelles ont influencé les perceptions et le succès de l'adoption de cette méthode.

Conclusion

La méthode de la mère «kangourou» est une intervention complexe axée sur le comportement qui inclut de multiples éléments. Le succès de sa mise en œuvre exige un engagement fort des utilisateurs et une mobilisation des parties intéressées. De futurs travaux de recherche incluent la conception et l'essai de modèles d'interventions spécifiques pour favoriser l'adoption de cette méthode.

Resumen

Objetivo

Investigar los factores que influencian la adopción del método madre canguro en diferentes contextos.

Métodos

Se realizaron búsquedas en las bases de datos PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science y la Organización Mundial de la Salud sobre estudios relacionados con el “método madre canguro”, “cuidado canguro” o “contacto directo de la piel” desde el 1 de enero de 1960 al 19 de agosto de 2015, sin limitación de idiomas. Se incluyeron informes sistemáticos y búsquedas manuales de referencias de revisiones y artículos publicados. Dos revisores independientes revisaron los artículos y extrajeron datos sobre los cuidadores, las características del sistema sanitario y los factores contextuales. Se desarrolló un modelo conceptual para analizar la integración del método madre canguro en los sistemas sanitarios.

Resultados

Se revisaron 2 875 estudios y se incluyeron 112 estudios que contenían datos cualitativos sobre la implementación. El método madre canguro se aplicó de formas diferentes en contextos diferentes. Los estudios muestran que existen diversas barreras a la hora de implementar el método madre canguro, incluyendo la necesidad de tiempo, apoyo social, asistencia médica y aceptación familiar. Las barreras dentro de los sistemas sanitarios incluían la organización, la financiación y el suministro de servicios. En el contexto general, las normas culturales influenciaron las percepciones y el éxito de la adopción.

Conclusión

El método madre canguro es una intervención compleja impulsada por el comportamiento e incluye múltiples elementos. El éxito de la implementación requiere una participación elevada del usuario y la involucración del interesado. Las futuras investigaciones incluyen diseñar y probar modelos de intervenciones específicas para mejorar la aceptación.

ملخص

الهدف

النظر في العوامل التي تؤثر على تبني طريقة رعاية الأمهات لمواليدهن على طريقة الكنغر في سياقات مختلفة.

الطريقة

لقد بحثنا في قواعد بيانات PubMed و Embase و Scopus و Web of Science وقواعد البيانات الإقليمية التابعة لمنظمة الصحة العالمية لإيجاد دراسات حول "رعاية الأم لوليدها على طريقة الكنغر" أو "الرعاية على طريقة الكنغر" أو "رعاية الوليد بملامسة بشرة الأم" بدءًا من 1 يناير/كانون الثاني 1960 وحتى 19 أغسطس/آب 2015 من دون القيود اللغوية. وقمنا بتضمين التقارير الصادرة عن البرامج ومراجع المقالات والمراجعات التي تم إجراء البحث بشأنها بشكل يدوي. ثم قام اثنان من المراجعين المستقلين بتصفح المقالات واستخلاص البيانات حول مقدمي الرعاية، وخصائص النظام الصحي، والعوامل السياقية. كما قمنا بوضع نموذج تصوري لتحليل عملية إدماج رعاية الأم لوليدها على طريقة الكنغر في الأنظمة الصحية.

النتائج

قمنا بفحص دراسات بلغ عددها 2875 دراسة، كما قمنا بتضمين 112 دراسة اشتملت على بيانات نوعية حول التنفيذ. كانت رعاية الأم لوليدها على طريقة الكنغر قد تم تطبيقها بطرق مختلفة في سياقات مختلفة. وتكشف الدراسات عن وجود العديد من العوائق في طريق تطبيق رعاية الأم لوليدها على طريقة الكنغر، من بينها الحاجة إلى الوقت، والدعم الاجتماعي، والرعاية الصحية، وتقبل الرعاية من جانب الأسرة. ومن بين العوائق الكامنة في النظم الصحية كانت هناك النواحي التنظيمية، والتمويل، وتقديم الخدمة. وفي السياق الأعم، أثرت المعايير الثقافية على التصورات المحيطة بهذا النوع من الرعاية ومدى نجاح تطبيقه.

الاستنتاج

تمثل رعاية الأم لوليدها على طريقة الكنغر وسيلة معقدة للتدخل تعتمد على السلوك، وتتضمن عدة عناصر. ويحتاج نجاح تطبيقها إلى مشاركة كبيرة من جانب المستفيدين فضلاً عن إدراج جهود الجهات المعنية. وتتضمن البحوث المستقبلية نماذج لتصميم واختبار عمليات تدخل محددة بغرض زيادة تبني هذا النوع من الرعاية.

摘要

目的

旨在调查不同环境下采用袋鼠妈妈式护理的影响因素。

方法

我们搜索了 PubMed、Embase、Scopus、Web of Science 以及世界卫生组织的区域数据库,以查找 1960 年 1 月 1 日到 2015 年 8 月 19 日期间关于“袋鼠妈妈式护理”或“袋鼠式护理”或“肌肤接触护理”的研究。我们包括了项目报告以及手工检索到已发表的评论与文章等参考资料。两个独立的评论员分别筛选出关于护理人员、卫生系统特征和环境因素的文章并提取了数据。我们开发了一个概念模型,以分析袋鼠妈妈式护理在卫生系统中的整合。

结果

我们筛选出 2875 项研究,其中 112 项研究中包含实施方面的定性数据。 袋鼠妈妈式护理以各种方式应用于不同的环境中。该研究表明实施袋鼠妈妈式护理存在几个障碍,包括需要时间、社会支持、医疗护理和家庭的接受。卫生系统内部的障碍包括组织、筹资和提供服务。在大环境中,文化规范影响人们对采用该护理方式的看法和成功率。

结论

袋鼠妈妈式护理是一种复杂的干预措施,受行为驱动且涵盖多种因素。 成功的实施要求用户的高度参与以及其他利益相关者的参与。未来的研究包括具体干预措施的设计和测试模型,以提高该护理方式的接受率。

Резюме

Цель

Изучить факторы, влияющие на применение метода «кенгуру» в различных контекстах.

Методы

Нами был проведен поиск по базам данных PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, а также по региональным базам данных Всемирной организации здравоохранения; целью поиска были исследования по теме «метод "кенгуру"», или «принцип "кенгуру"», или «метод телесного контакта» в период с 1 января 1960 г. по 19 августа 2015 г. без ограничений по языку. Мы включили в рассмотрение отчеты о программах и найденные вручную ссылки на опубликованные обзоры и статьи. Два независимых эксперта просматривали статьи и извлекали из них данные о лицах, осуществляющих уход, о характеристиках систем здравоохранения и факторах, определяющих контекст. Мы разработали концептуальную модель для анализа интеграции метода «кенгуру» в системы здравоохранения.

Результаты

Мы проверили 2875 исследований и включили в обзор 112 исследований, которые содержали количественные данные, касающиеся осуществления метода. В различных контекстах способы осуществления ухода по методу «кенгуру» были различными. Исследования показали, что существует несколько препятствий на пути осуществления ухода методом «кенгуру», включая потребность во времени, социальной поддержке, медицинском уходе, а также в принятии со стороны семьи. Препятствия со стороны системы здравоохранения включают организационные аспекты, финансирование и предоставление услуг. В широком контексте культурные нормы оказывали влияние на восприятие и успех осуществления метода.

Вывод

Уход по методу «кенгуру» представляет собой комплексное вмешательство, в основе которого лежат поведенческие факторы и которое включает множество элементов. Для успешного осуществления необходима высокая степень заинтересованности участников, а также привлечение партнеров. В будущих исследованиях планируется уделить время разработке и тестированию моделей конкретных вмешательств с целью улучшения усвоения метода.

Introduction

More than 2.7 million newborns die each year, accounting for 44% of children dying before the age of five years worldwide. Complications of preterm birth are the leading cause of death among newborns.1 Kangaroo mother care can include early and continuous skin-to-skin contact, breastfeeding, early discharge from the health-care facility and supportive care.2 The clinical efficacy and health benefits of kangaroo mother care have been demonstrated in multiple settings. In low birthweight newborns (< 2000 g) who are clinically stable, kangaroo mother care reduces mortality and if widely applied could reduce deaths in preterm newborns.3,4 However, in spite of the evidence, country-level adoption and implementation of kangaroo mother care has been limited and global coverage remains low. Few studies have examined the reasons for the poor uptake of kangaroo mother care.

To understand factors influencing adoption of kangaroo mother care in different contexts, we did a systematic review. We created a narrative analysis of the articles and reports identified, guided by a conceptual framework5 with five elements: (i) the problem being addressed – neonatal mortality; (ii) the intervention or innovation aimed at addressing the problem; (iii) the adoption system – those implementing the intervention, those benefiting from it and those affected by it; (iv) the health system – organization, financing and service delivery; and (v) the broad context – demographic, epidemiological, political, economic and sociocultural factors. These five elements interact to influence the extent, pattern and rate of adoption of interventions in health systems.5

Methods

We searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, African Index Medicus (AIM), Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS), Index Medicus for the Eastern Mediterranean Region (IMEMR), Index Medicus for the South-East Asian Region (IMSEAR) and Western Pacific Region Index Medicus (WPRIM) without language restrictions, from 1 January 1960 to 19 August 2015 using the search terms “kangaroo mother care” or “kangaroo care” or “skin-to-skin care.” We excluded studies without human subjects or without primary data collection. We screened studies for inclusion if they discussed barriers to kangaroo mother care implementation or enablers for successful implementation. Our population of interest included mothers, newborns or mother-newborn dyads who had practiced kangaroo mother care, and health-care providers, health facilities, communities and health systems that have implemented such care. We hand-searched the reference lists of published systematic reviews and references of the included articles. To search the grey literature for unpublished studies, we explored programmatic reports and requested data from programmes implementing kangaroo mother care.

Two reviewers independently extracted data from identified articles using standardized forms to identify potential determinants of kangaroo mother care uptake, including data on knowledge, attitudes and practices. Reviewers compared their results to reach consensus and ties were broken by a third party. To assess study quality, we evaluated each study in five quality domains: selection bias, appropriateness of data collection, appropriateness of data analysis, generalizability and ethical considerations.6

A deductive approach was used to fit the outputs of the analysis to the elements of the conceptual framework and explore emerging themes.7 Using the qualitative analytical software NVivo (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia), two researchers indexed and annotated the data through several rounds of coding to analyse themes, viewpoints, ideas and experiences. Once major themes were established, we constructed narratives and categorized the data into matrices by theme. We highlighted quotes that summarized multiple perspectives from the articles. Narratives and matrices were used to define specific concepts and explore associations between themes.

Themes were explored at each level of implementation (mothers, fathers and families; health-care workers; facilities). We examined the interactions between implementers and described health system characteristics that could influence the uptake of kangaroo mother care.

Results

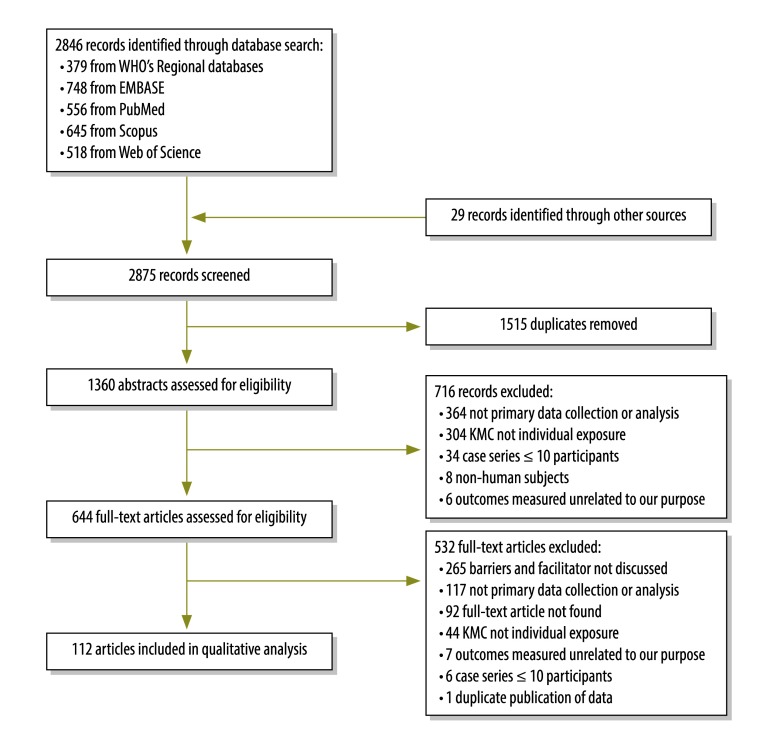

Of the 2875 papers identified, we included 112 studies with qualitative data on barriers to and enablers of kangaroo mother care (Fig. 1). Most of the studies were published between 2010 and 2015 (66; 59%) and had less than 50 participants (67; 60%). Nearly half of the studies were surveys or interviews (50; 45%). Forty studies (36%) were conducted in the WHO Region of the Americas; 29 (26%) in WHO African Region; 64 (57%) in countries with low neonatal mortality, defined as less than 15 deaths per 1000 live births;8 48 (43%) in urban settings; and 67 (60%) at health facilities. Many studies did not include neonatal characteristics such as gestational age (68; 61%) or weight (75; 67%; Table 1). The majority (68; 60%) of the studies appropriately addressed at least four of the five quality domains.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart showing the selection of studies on kangaroo mother care (KMC)

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies in the systematic review on kangaroo mother care.

| Study characteristic | No. (%) of studies (n = 112) |

|---|---|

| Year | |

| 20159–15 | 7 (6) |

| 2010 to 201416–75 | 59 (53) |

| 2000 to 200976–115 | 40 (36) |

| 1988 to 1999116–120 | 5 (5) |

| No. of participants | |

| < 5010–12,14,15,17,22,24–26,28–31,33,35,36,39–41,45,47,50,52,53,55–57,59,60,63,64,67,69,72,74,77,79,80,83–87,89–97,99–103,106,108,110–112,114,115,117 | 66 (59) |

| 50 to < 10013,16,20,21,27,32,37,42–44,51,66,68,71,118,120 | 15 (13) |

| 100 to < 20023,46,48,54,61,65,73,78,82,88,104,105,107,109 | 15 (13) |

| ≥ 2009,18,19,34,38,49,58,62,70,75,76,81,98,113,116,119 | 16 (14) |

| Study type | |

| Survey or interview11–14,16,18,21,28,29,32,33,35,39–45,48–52,58,63,64,66,69,72,74,75,77,79,87,89–91,94–97,101,102,106,107,111,114,115,117 | 50 (45) |

| Facilities’ evaluation24,25,27,31,34,47,53–55,57,59,60,67,80,82,83,100,108,113 | 19 (17) |

| Randomized control trial9,10,37,61,68,76,99,103,105,110,112,119 | 12 (11) |

| Cohort study23,56,81,92,116 | 5 (4) |

| Other (chart review, case control, surveillance)15,17,19,20,22,26,30,36,38,46,62,65,70,71,78,84–86,88,98,104,109,118,120 | 24 (21) |

| Pre-post73 | 1 (1) |

| Interventional trial93 | 1 (1) |

| WHO region | |

| Americas12,21,28,33–37,42–44,50,52,56,63,65,71–75,84–91,94,97,101,106,108,112–115,119,120 | 40 (36) |

| African9–11,16,17,20,23–26,29,47,51,55,58–60,68,80–83,92,96,99,100,102,110,116 | 29 (26) |

| European13–15,38–41,45,48,49,53,54,64,66,70,95,104,107,118 | 19 (17) |

| South-East Asia18,19,22,30,32,67,76,77,93,98,103,109 | 12 (11) |

| Eastern Mediterranean46,61,62,69 | 4 (3) |

| Western Pacific31,78,105,111 | 4 (3) |

| Multiple regions27,57,79 | 3 (3) |

| Missing117 | 1 (1) |

| Country-level neonatal mortality rate (deaths per 1000 live birth) | |

| < 514,15,36–45,48,49,52–54,56,63–66,70,71,82,94,95,104–108,111–113,120 | 36 (32) |

| 5 to < 1512,21,28,33–35,46,50,58,59,61,62,69,74,75,84–91,97,101,114,115,119 | 28 (25) |

| 15 to < 309–11,16–19,22–26,29,30,32,47,51,57–60,68,76–78,80–83,93,98–100,102,103,109,110 | 37 (33) |

| ≥ 30 50, 57, 88 | 4 (4) |

| Missing13,20,27,31,73,79,117 | 7 (6) |

| Setting | |

| Urban17,23,28,33,35,36,38,39,41,43,44,49,50,52,56,60,61,63,65–67,72,77,78,80,81,87,89–92,96,97,100–102,105,106,108,109,111,114–120 | 48 (43) |

| Urban and rural19,34,42,58,62,70,75,79,84,85,88,99,104,110,113 | 15 (13) |

| Rural16,21,51,68,76,98 | 6 (5) |

| Missing9–15,18,20,22,24–27,29–32,37,40,45–48,53–55,57,59,64,69,71,73,74,82,83,86,93–95,103,107,112 | 43 (38) |

| Population source | |

| Health facility10,11,13,14,16,17,23–30,33–36,41,46,47,49,50,52,55–57,59–61,64,67,69–71,75,76,78–92,94,96,97,99,100,102,106,108,110,113–116,118,119 | 67 (60) |

| Neonatal intensive care unit or stepdown unit12,15,22,31,37–40,42–45,48,53,54,63,65,66,72–74,93,95,103–105,107,109,111,112,117,120 | 32 (28) |

| Community or population-based surveillance9,18,19,21,32,51,58,62,68,77,98,101 | 12 (11) |

| Missing20 | 1 (1) |

| Gestational age | |

| Preterm 34 to < 37 weeks15,16,35,50,72,84,87,97,102,114,117,118,120 | 13 (12) |

| All gestational ages9,10,19,36,38,39,58,62,68,76,77,98 | 12 (11) |

| Very preterm < 34 weeks40,48,63–65,70,95,101,112 | 9 (8) |

| Mixed preterm and very preterm < 37 weeks33,37,89,90,94,109 | 6 (5) |

| Full term ≥ 37 weeks41,49,61,71 | 4 (3) |

| Missing11–14,17,18,20–32,34,42–47,51–57,59,60,66,67,69,73–75,78–83,85,86,88,91–93,96,99,100,103–108,110,111,113,115,116,119 | 68 (61) |

| Birthweight | |

| Low birthweight 1500 to < 2500 g33,50,51,72,80,81,85,88,91,93,96,116,119 | 13 (12) |

| All birthweights9,10,19,36,38,39,48,58,62,68,76,77,98 | 13 (12) |

| Mixed low and very low birthweight < 2500 g17,23,90,92,101,109,120 | 7 (6) |

| Very low birthweight < 1500 g78,89,103,105 | 4 (3) |

| Missing11–16,18,20–22,24–32,34,35,37,40–47,49,52–57,59–61,63–67,69–71,73–75,79,82–84,86,87,94,95,97,99,100,102,104,106–108,110–115,117,118 | 75 (67) |

WHO: World Health Organization.

Note: Inconsistencies arise in some values due to rounding.

Conceptual framework

Problem

The narrative synthesis of the studies showed that the burden of death and disability of newborns was acknowledged as an important problem.9–11,16–32,76–83

Intervention

The included studies revealed that kangaroo mother care is a complex intervention with several possible components – skin-to-skin contact, breastfeeding, early discharge and follow-up (Table 2). The included components varied across locations and by individual implementer.

Table 2. Descriptions of kangaroo mother care in studies included in the systematic review.

| Characteristic | Common theme | Less common theme | Quotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration skin-to-skin contact | As long as possible 24 hours/day Early/prolonged/continuous 2 hours or more per day To begin once newborn had stabilized |

During breastfeeding Less than 24 hours/day To begin immediately after birth To begin 24 hours after birth |

“Kangaroo mother care is defined as early, prolonged and continuous (or as far as circumstances permit) skin-to-skin care between the low birthweight infant and mother.”39 |

| Extended duration skin-to-skin contact | As long as possible As long as circumstances permit Until newborn weight of 2500 g |

First month of life Until 24 hours after birth Until 37 weeks post menstrual age |

“Mothers were instructed to continue kangaroo position at least until the baby reached 2500 g.”116 |

| Breastfeeding | Exclusive On demand Breastfeeding encouraged Breastfeeding would begin only after skin-to-skin contact had been completed for a given period of time |

Kangaroo mother care integrated as part of a larger breastfeeding package Discharge after breastfeeding established Breastfeeding only after suturing and skin-to-skin contact had been completed |

“Exclusive breastfeeding wherever possible and early discharge from the health facility when breastfeeding has been established.”88 |

| Newborn clothing | Blanket cover Naked Diaper |

Cap Booties |

“Undressed except for a diaper and was covered with the mother’s gown and a baby sheet.”93 |

| Newborn position | Sleeping upright Vertical against chest Between mother’s breasts skin-to-skin contact Held after being removed from incubator Prone |

Upright On adult’s chest On mother’s or father’s chest Vertical under clothes Prone position Against mother’s chest |

“The baby is kept upright, close to the chest of the adult.”84 |

| Bathing | Clean baby with damp or dry cloth | Dry infant after birth | “The routines included quickly drying the newborn immediately after birth and then placing it naked (skin-to-skin) on the mother’s chest.”41 |

| Caregiver clothing | Open gown Wrap (cloth or blanket) |

Dupatta Specialized kangaroo mother care bra |

“Held in position by using innovations like dupatta (stole), sports bra, loose blouse or a specially designed sling.”109 |

| Caregiver position | Upright Prone Inclined |

Seated in chair Walking around |

“Skin-to-skin contact prone or semi-upright position.”101 |

| Early discharge | Early discharge (undefined) Early discharge based on clinical conditions Infant weight gain, mother competency in kangaroo mother care |

Skin-to-skin contact encouraged before discharge Discharge after breastfeeding established |

“Discharge when the mother shows an appropriate level of infant-handling competency and the infant is gaining weight.”33 |

| Follow-up | Follow up (undefined) Adequate follow-up Within the facility at: 1−2 weeks 1–6 months 1 year |

As part of Brazilian Ministry of Health guidelines: Week 1: 3 times (home) Week 2: 2 times (home) Week 3: 1 time (home) |

“With a proper follow-up system in place for regular review of the infant.”90 |

Note: The quotes were concise examples of common themes found across many articles.

The promotion of skin-to-skin contact for as long as possible once the newborn was stabilized emerged as a common theme in several studies.33–35,84–91,116 However, there was limited information on the recommended frequency and duration of skin-to-skin contact and the specific criteria for stopping skin-to-skin contact.31,36–38,89,92,93,117

Implementation

The complexity of kangaroo mother care and lack of a standardized operational definition makes it challenging to implement. Implementation of kangaroo mother care can be considered at three levels: (i) mothers, fathers and families; (ii) health-care workers; and (iii) facilities. The location of facilities and the resources available determine whether kangaroo mother care takes place in the health facility or at home.18,27,33

Mothers, fathers and families were usually the primary caregivers of preterm newborns and involved in decision-making and practice of care.11,16,94,95,117 Health-care workers were critical for implementation in hospitals or health facilities. Their main role was to educate the parents about kangaroo mother care.

We identified six major themes concerning barriers and enablers for implementation of kangaroo mother care: (i) buy-in and bonding; (ii) social support; (iii) time; (iv) medical concerns; (v) access and (vi) context (Table 3).

Table 3. Summary of enablers and barriers to implementation of kangaroo mother care.

| Level of implementation | Adoption systems |

Health systems access | Context, cultural norms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buy-in and bonding | Social support | Access | Medical concerns | |||

| Parents | ||||||

| Enablers | Calming, natural, instinctive, healing for parents and infant | Father, health-care worker, family and community support for mothers and fathers was crucial to success of kangaroo mother care | Kangaroo mother care at home allowed parents to perform other duties | Helped mothers recover emotionally | Belief that kangaroo mother care was cheaper than incubator care | Mother preferred kangaroo mother care to incubator, inspired confidence Gender equality |

| Barriers | Stigma, shame, kangaroo mother care felt forced | Fear, guilt, discomfort of family members to participate or condone kangaroo mother care in public Privacy |

Caregivers were unable to devote time Mothers lonely in kangaroo mother care ward |

Maternal fatigue and pain | Associated costs Transport |

Traditional, bathing, carrying and breastfeeding practices did not always align with kangaroo mother care guidelines |

| Health-care workers | ||||||

| Enablers | Nurses more likely to use kangaroo mother care after seeing positive effects. Support from more experienced nurses improved buy-in |

Management promotion of kangaroo mother care Role of parents and other health-care workers |

Kangaroo mother care did not increase workload | Temperature stability. Experienced nurses more comfortable with kangaroo mother care |

Virtual communication and training. Integration of kangaroo mother care into health-care curriculum |

None |

| Barriers | Nurses fail to have strong belief in importance of kangaroo mother care Inconsistent knowledge and application of kangaroo mother care |

Management did not prioritize kangaroo mother care Parents could serve as a hindrance to health-care worker |

Extra workload Takes away time from other patients |

Nurses did not feel kangaroo mother care appropriate for infants who they felt were too small/young/ill | Difficulty finding time for training Inadequate/inconsistent training |

Traditional protocols interfered (bathing, carrying) Nurse excluding father from infant care was a cultural norm |

| Facilities | ||||||

| Enablers |

Leadership Management support |

Staffing support Good communication Use of committees to advocate for kangaroo mother care |

Unlimited visitation preferred | Access to private space including family rooms or privacy screen. Higher breast milk feeding rates at discharge when breast feeding was allowed and encouraged throughout the hospital |

Access to structural resources Quiet atmosphere within facilities allows mothers to rest Breast milk banks provide milk and can be an educational tool among mothers |

Reporting and data Collection of data Use of performance standards and quality improvement measures Site assessment tools |

| Barriers | Leadership lack of buy-in led to lack of adequate resources | Staffing shortages, high staff and leadership turnover Staff resisted changing protocols |

There was limited visitation time due to staff shortages | Disagreement over clinical stability Facilities did not provide food for mothers Only low birthweight infants received kangaroo mother care in some locations |

Lack of money at the facility for mother’s transportation Distance to the hospital for mothers without hospital-provided transportation Lack of space and privacy for mothers to do kangaroo mother care Lack of money for transportation, beds and kangaroo mother care wrappers Poor management of resources donated to the hospital |

Lack of use of data to document skin-to-skin contact practised on electronic medical record Nurses not given feedback on kangaroo mother care data collected Visitation policies sometimes prevented mothers from performing skin-to-skin contact continuously. Staff found visitors get in the way. |

Buy-in and bonding

Buy-in and bonding refer to the acceptance of kangaroo mother care, belief in the benefits of such care to mothers and preterm or low birthweight infants and reported perceptions of bonding. Fear, stigma and/or anxiety about having a preterm infant impaired the care process. Mothers felt shame or guilt for having a preterm infant96,97 and some did not want to keep their baby.16

Positive perceptions of the potential benefits of kangaroo mother care for caregivers and for newborns among mothers, fathers and families promoted uptake. Studies used words such as relaxed, calm, happy, natural, instinctive and safe to describe the bonding process that mothers and fathers reported during and after kangaroo mother care.35,39,40,94,95,98 Mothers observed their newborns sleeping longer during skin-to-skin contact; infants were described as less anxious, more restful, more willing to breastfeed and happier than when in an incubator.41,121

A lack of belief in kangaroo mother care and limited knowledge of such care restricted its uptake among health-care workers.39,42–45 In some facilities, there was reluctance by management to allocate dedicated space to kangaroo mother care or to rearrange staffing schedules to allow for supervision of kangaroo mother care.12,16,22,25,29,36,46,82,99,122 Facility leadership had high turnover as leaders trained in kangaroo mother care frequently left for better positions.25,27,29,42,47,82,99,100,123 On the other hand, facilities that had successfully implemented kangaroo mother care reported support from management and good communication among the staff.24,42

Social support

Social support refers to assistance received from other people to perform kangaroo mother care. While practicing kangaroo mother care, both mothers and fathers did not feel supported by their families or communities.35,96 Mothers experienced a lack of support from health-care workers. In settings like Zimbabwe, fathers voiced unease about performing kangaroo mother care because of societal norms that childcare should be the role of the mother.79,96 In contrast, among mothers, fathers and families, uptake was promoted by societal acceptance of paternal participation in childcare, by family and community acceptance of kangaroo mother care and by the presence of engaged health-care workers.32,48 In societies where gender roles were more equal (e.g. Scandinavian countries), there were fewer barriers to fathers performing kangaroo mother care.48,49 Paternal involvement played a large role in uptake – either by division of labour or by helping the mother feel comfortable. In Brazil, mothers were grateful to have someone help them during kangaroo mother care, such as grandmothers and sisters, who could take care of housework and help with the newborn.101 Within the maternity ward, peer support from other mothers through sharing their kangaroo mother care experiences also helped promote acceptance.79,102

When institutional leadership did not prioritize kangaroo mother care, health-care workers were less motivated to practice or teach it,42,44 but felt empowered to do so when management allowed for roles in decision-making, promoted kangaroo mother care or mobilized resources for it.24 Staffing shortages and staff turnover created barriers to implementation of kangaroo mother care within a facility.42 By contrast, effective coordination of and communication between staff helped facilitate implementation.82

Time

The time needed to provide kangaroo mother care was a potential barrier for mothers, fathers and families, due to responsibilities at home and work and time needed for commuting, preventing them from devoting the time needed for continuous and extended kangaroo mother care.16,39,41,50,79,91,102 Conversely, practice of such care at home promoted its uptake.92 High workload of health-care workers did not allow sufficient time to dedicate to teaching kangaroo mother care, which further increased workload, especially in facilities with staffing shortages.78,79,103

One study showed that uptake of kangaroo mother care increased with expansion of visiting hours at health facilities.104

Medical concerns

Clinical conditions of the mother and/or newborn may prevent kangaroo mother care from occurring. The medical effects of delivery for mothers, including fatigue, depression and postpartum pain, especially after a caesarean section, can reduce uptake of kangaroo mother care.48,51,52,77,98 Particularly for very preterm or unstable infants, concern about potential adverse consequences, such as fear of dislocation of intravenous lines, was an obstacle to kangaroo mother care.38,53,54 Knowledge that kangaroo mother care supported newborns in stabilizing their temperatures, helped with breathing and promoted mother–child bonding, encouraged its use.118

Access

While parents believed that kangaroo mother care was less costly than incubator care,96 lack of money for transportation and the distance to hospital were often reported as the biggest challenges55,81,82,105 as were low resources for newborn-care services.82 Lack of private space for mothers to perform kangaroo mother care and to remain in the hospital with the newborn hindered its uptake,24,25 as did allocation of resources intended for kangaroo mother care to other programmes.24 Uptake improved with transportation for mothers not staying at the hospital, wrappers to hold the baby, furniture/beds where mothers could conduct kangaroo mother care, rooms where mothers could spend the night with the baby,24,48 private spaces and dedicated resources.40,106

Without uniform knowledge and protocols within a facility, health-care workers were uncomfortable promoting kangaroo mother care.16,27,42,99,107 In-service training82,100 of health-care workers enhanced kangaroo mother care implementation.56 Virtual communication and training, often within facilities, allowed more nurses to be trained in kangaroo mother care despite busy schedules and staffing shortages.36 Expanding training to other health-care personnel, such as administrators and interns, also enabled care. Many nurses reported that integration of kangaroo mother care into pre-service and training curricula was beneficial.36,57

Context

Sociocultural context and sociocultural constructs of gender and roles of parents in childcare, men in the household and other family members influenced uptake.79,85,96 Parental and familial adherence to traditional newborn practices was reported as a barrier to kangaroo mother care.105 Traditional practices of early bathing and wrapping infants soon after birth were ingrained behaviours in many cultures that were difficult to change, even after training.16,58 In areas in which carrying the baby on the back was common, it seemed strange to place the baby on the front.23 In some contexts, it was considered unclean to have the mother carry the baby on her chest without a diaper.79

Please refer to the supplementary Table 4 (available at: http://www.who.int/volumes/94/2/15-157818) for full details of the included studies.

Table 4. Description of studies included in the systematic review on kangaroo mother care .

| Author, year | Country | Rural or urban | Study design | Sample size | Newborn characteristics | Kangaroo mother care components | Onset of skin-to-skin care | Provision of kangaroo mother care |

Barriers and facilitators |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hours per day | Days | Caregivers | Health-care workers | Facilities | Policies and guidelines | |||||||||

| Abul-Fadl, 201262 | Egypt | Mixed | Pop based surveillance, facility evaluation | 1052 mothers | All ages | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | Xa | X | X | –a | |

| Aliganyira, 201429 | Uganda | Mixed | Facility evaluation, focus group/interview | 11 facilities | N/A | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | X | X | – | |

| Alves, 200784 | Brazil | Mixed | Chart review, focus group/ interview | 33 dyads | Premature; N/A cut-off | N/A | Once eligible: N/A definition | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| de Araújo, 201033 | Brazil | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 30 parents | Premature, ≥ 2000 g | N/A | Once eligible: N/A definition | 5–6 | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Arivabene, 201028 | Brazil | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 13 mothers | N/A | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| Bazzano, 201251 | Ghana | Rural | Focus group/ interview | 9 mothers, 23 health-care workers | Low birthweight; N/A cut-off |

Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| Bergh, 201359 | Ghana | N/A | Facility evaluation | 38 facilities | N/A | Skin-to-skin care, exclusive breastfeeding, | Immediately after birth | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | X | |

| Bergh, 2003100 | South Africa | Urban | Facility evaluation | 2 facilities | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | X | X | – | |

| Bergh, 201267 | Indonesia | Urban | Facility evaluation | 10 facilities | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| Bergh, 200899 | South Africa | Mixed | Randomized controlled trial | 36 facilities | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Bergh, 201226 | Ghana | N/A | Pop based surveillance, facility evaluation | 38 facilities | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | – | X | |

| Bergh, 200983 | Ghana | N/A | Facility evaluation | 4 regions (out of 10) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Bergh, 201225 | Malawi | N/A | Facility evaluation | 14 facilities | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | X | |

| Bergh, 201255 | Mali | N/A | Facility evaluation | 7 facilities | N/A | Skin-to-skin care, exclusive breastfeeding, discharge, follow-up | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | X | |

| Bergh, 200782 | Malawi | N/A | Facility evaluation | 6 facilities | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Bergh, 201247 | Rwanda | N/A | Facility evaluation | 7 facilities | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Bergh, 201224 | Uganda | N/A | Facility evaluation | 11 facilities | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | X | |

| Bergh, 201427 | Malawi, Mali, Rwanda, and Uganda | Urban | Facility evaluation, Focus group/interview | 39 facilities | N/A | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | X | |

| Blencowe, 200981 | Malawi | Urban | Prospective cohort | 272 newborns | < 2000 g | N/A | Once eligible: N/A definition | N/A | N/A | X | – | X | – | |

| Blencowe, 200580 | Malawi | Urban | Facility evaluation | 1 facility | < 2000 g | Skin-to-skin care, exclusive breastfeeding, discharge, follow-up | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| Blomqvist, 201348 | Sweden | N/A | Focus group/ interview | 76 mothers, 74 fathers | 28–33 weeks, 740–2920 g | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Blomqvist, 201139 | Sweden | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 23 dyads | All ages | Skin-to-skin care, exclusive breastfeeding | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Boo, 2007105 | Malaysia | Urban | Randomized controlled trial | 126 dyads | < 1501 g | Skin-to-skin care | Once eligible: N/A definition | 1 | 10 | X | X | X | – | |

| Brimdyr, 201269 | Egypt | N/A | Focus group/ interview | 40 nurses and health-care workers | N/A | Skin-to-skin care | Immediately after birth | 1 | 1 | X | X | X | – | |

| Calais, 201049 | Sweden, Norway | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 117 mothers, 107 fathers | Full term | Skin-to-skin care, discharge, follow-up | Immediately after birth | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | X | |

| Castiblanco López, 201150 | Colombia | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 8 mothers | < 36 weeks, 2320 g | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | X | – | |

| Charpak, 200679 | 15 developing countries | Mixed | Focus group/ interview | 17 kangaroo mother care co-ordinators, 15 facilities | N/A | Skin-to-skin care, discharge, follow-up | Immediately after birth | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Chia, 2006111 | Australia | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 34 nurses | N/A | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Chisenga, 201511 | Malawi | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 113 mothers | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| Colameo, 200685 | Brazil | Mixed | Cross sectional | 28 facilities | Low birthweight; N/A cut-off | N/A | Once eligible: N/A definition | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Cooper, 201473 | United States of America | Mixed | Pre-post | 48 nurses and 101 parents | N/A | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | – | – | |

| Crenshaw, 201271 | United States of America | N/A | Descriptive | 261 dyads | Full term | Skin-to-skin care | ≤ 2 mins after birth | N/A | 1 | X | X | X | – | |

| Dalal, 201430 | India | Mixed | Cross sectional | 145 HCPs | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | – | – | |

| Dalbye, 201141 | Sweden, Norway | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 20 mothers | Full term | Skin-to-skin care | Immediately after birth | N/A | N/A | X | X | – | – | |

| Darmstadt, 200698 | India | Rural | Intervention | 2063 mothers | All ages | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | X | – | |

| De Vonderweid, 2003104 | Italy | Mixed | Pop based surveillance | 109 facilities | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | X | X | X | |

| Duarte, 200197 | Brazil | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 1 mother | Premature; N/A cut-off | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | 38 | X | – | X | – | |

| Eichel, 2001108 | United States of America | Urban | Facility evaluation | 1 facility | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | X | |

| Eleutério, 2008114 | Brazil | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 9 mothers | Premature; N/A cut-off | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | – | X | – | |

| Engler, 2002113 | United States of America | Mixed | Facility evaluation | 537 facilities | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Ferrarello, 201452 | United States of America | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 15 mothers, 14 nurses | N/A | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | X | |

| Flynn, 201066 | Ireland | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 62 health-care workers | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | – | – | |

| Freitas, 200786 | Brazil | N/A | Prospective cohort, descriptive | 22 newborns | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | – | X | – | |

| Furlan, 200387 | Brazil | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 10 parents | Premature; N/A cut-off | Skin-to-skin care | Once eligible: N/A definition | 10; mean | N/A | X | – | X | X | |

| Gontijo, 201034 | Brazil | Mixed | Facility evaluation | 293 facilities | N/A | Skin-to-skin care, exclusive breastfeeding | Once eligible: N/A definition | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| Gontijo, 201275 | Brazil | Mixed | Focus group/ interview | 293 facilities | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | – | X | – | |

| Gonya, 201363 | United States of America | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 32 mothers | < 27 weeks | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | X | X | |

| Haxton, 201236 | United States of America | Urban | Intervention, qualitative | 30 mothers | All ages | Skin-to-skin care, exclusive breastfeeding | Within one hour after birth | 3 | 1 | X | X | X | X | |

| Heinemann, 201340 | Sweden | N/A | Focus group/ interview | 7 mothers, 6 fathers | < 27 weeks | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | X | – | |

| Hendricks-Muñoz, 201044 | United States of America | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 59 nurses | N/A | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | X | – | – | |

| Hendricks-Muñoz, 201365 | United States of America | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 143 mothers, 42 health-care workers | < 34 weeks | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | – | – | |

| Hendricks-Muñoz, 201456 | United States of America | Urban | Prospective cohort | 30 nurses | N/A | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| Hennig, 200688 | Brazil | Mixed | Cross sectional | 148 doctors and nurses, 11 facilities | Low birthweight; N/A cut-off | N/A | Clinical stable | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Higman, 201513 | England | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 6 nurses and 51 clinicians | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | – | – | |

| Hill, 201058 | Ghana | Mixed | Focus group/ interview | 635 mothers, 14 villages | All ages | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | – | – | |

| Hunter, 201432 | Bangladesh | Rural | Focus group/ interview | 121 participants | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | – | – | |

| Ibe, 200492 | Nigeria | Urban | Crossover | 13 newborns, 11 mothers and female relatives | 1200–1999 g | Skin-to-skin care | After enrolment | 12 | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| Johnson, 2007106 | United States of America | Peri-urban/slum | Focus group/ interview | 17 nurses | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Johnston, 201137 | Canada | N/A | Randomized controlled trial crossover | 62 newborns | 28–36 weeks | Skin-to-skin care | ≥ 15 minute before heel lance | ≤ 1 | 2 | X | – | – | – | |

| Kambarami, 200296 | Zimbabwe | Urban | Focus group/ interview | N/A mothers | Low birthweight: N/A cut-off | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | X | – | |

| Keshavarz, 201061 | Islamic Republic of Iran | Urban | Randomized controlled trial | 160 dyads | Full term | Skin-to-skin care | 2 hours after caesarean | 3 | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| Kostandy, 2008112 | United States of America | N/A | Randomized controlled trial crossover | 10 newborns | 30–32 weeks | Skin-to-skin care | 30 minute before heel stick | 0.83 | 1 | – | X | – | – | |

| Kymre, 201345 | Sweden, Norway, Denmark | N/A | Focus group/ interview | 18 nurses | N/A | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | – | – | |

| Lee, 201242 | United States of America | Mixed | Focus group/ interview | 69 health-care providers, 11 facilities | N/A | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Legault, 1995120 | Canada | Urban | Randomized controlled trial, pre-post, crossover | 61 dyads | Premature: N/A cut-off 1000–1800 g | Skin-to-skin care | Once eligible: N/A definition | 0.5 | 1 | X | – | – | – | |

| Lemmen, 201364 | Sweden | N/A | Focus group/ interview | 12 families | 24–35 weeks | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | – | – | |

| Leonard, 2008102 | South Africa | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 6 parents | Premature: N/A cut-off | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| Lincetto, 1998116 | Mozambique | Urban | Prospective cohort | 246 newborns | < 2000 g | Skin-to-skin care, exclusive breastfeeding, discharge, follow-up | Stabilized health condition, presence of a sucking reflex, thermoregulation, mother's condition enabling her to care for the low birthweight infant, cessation of the infant's need for IV therapy, oxygen, photo-therapy or feeding by NG tube | > 20 | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Maastrup, 201253 | Denmark | N/A | Facility evaluation | 19 facilities | N/A | Skin-to-skin care | 18 out of 19 within 24 hour postpartum for stable preterm infant | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| Mallet, 2007107 | France | N/A | Focus group/ interview | 121 doctors and paramedical staff | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Martins, 2008115 | Brazil | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 5 mothers | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| McMaster, 200078 | Papua New Guinea | Urban | Chart review, facility evaluation | 109 newborns | < 1500 g | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| Moreira, 2009101 | Brazil | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 8 mothers | 30–32 weeks, < 2000 g | Skin-to-skin care | Once eligible: N/A definition | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| Mörelius, 201515 | Sweden | Urban | Survey | 129 nurses | All newborns | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | – | – | |

| Mörelius, 201270 | Sweden | Mixed | Pop based surveillance | 520 newborns | < 27 weeks | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | X | – | – | |

| Nahidi, 201446 | Islamic Republic of Iran | Urban | Questionnaire | 292 midwives | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | – | – | |

| Namazzi, 201510 | Uganda | Rural | Randomized controlled trial | 20 health facilities | All newborns | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Neu, 1999117 | N/A | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 8 mothers, 1 father | Premature; N/A cut-off | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | 1 | 2 | X | X | X | – | |

| Nguah, 201123 | Ghana | Urban | Prospective cohort | 195 dyads | 1000–2000 g | Skin-to-skin care, exclusive breastfeeding, follow-up | After admission in hospital and if mother was willing | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| Niela–Vilén, 201338 | Finland | Urban | Prospective cohort, qualitative | 170 mothers, 381 staff | All NICU newborns | N/A | Immediately after birth | N/A | N/A | X | X | – | – | |

| Nimbalkar, 201422 | India | Urban | Questionnaire | 52 paediatricians | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | X | – | – | |

| Nyqvist, 200895 | Sweden | N/A | Focus group/ interview | 13 mothers | < 32 weeks | Skin-to-skin care, discharge, follow-up | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | X | |

| Parmar, 2009109 | India | Urban | Retrospective cohort | 135 newborns | 26–37 weeks, 550–2500 g | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Pattinson, 2005110 | South Africa | Mixed | Randomized controlled trial | 34 facilities | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | – | X | – | |

| Priya, 200493 | India | N/A | Crossover | 30 dyads | Low birthweight; N/A cut-off | Skin-to-skin care | After routine care was observed and data were collected | 2 | 2 | X | – | – | – | |

| Quasem, 200377 | Bangladesh | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 35 mothers | All ages | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | X | – | |

| Ramanathan 2001103 | India | N/A | Randomized controlled trial | 28 newborns | < 1500 g | N/A | Once eligible: N/A definition | ≥ 4 | N/A | X | X | – | – | |

| Roller, 200594 | United States of America | N/A | Focus group/ interview | 10 mothers | 32–37 weeks | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | X | |

| Sá, 201035 | Brazil | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 10 mothers, 7 health-care providers | Premature; N/A cut-off | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| Sacks, 201321 | Honduras | Rural | Focus group/ interview | 48–72 traditional birthing attendant (6 focus groups with 8–12 participants per group) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | – | – | |

| Santos, 201372 | Brazil | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 12 mothers | Premature, low birthweight; N/A cut-off | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | X | – | |

| Shamba, 201420 | United Republic of Tanzania | Mixed | Focus group/ interview | 57 mothers and 14 traditional birthing attendants | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| Silva, 201474 | Brazil | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 20 nursing technicians | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | – | – | |

| Silva, 201512 | Brazil | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 8 nurses | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | X | – | – | |

| Silva, 200889 | Brazil | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 5 dyads | Premature: N/A cut-off, < 1000–1550 g | Skin-to-skin care | Once eligible: N/A definition | ≤ 24 | Depended on mothers length of stay | X | – | – | – | |

| Singh, 201219 | India | Mixed | Case control | 145 662 newborns, 810 204 mothers | All ages | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | – | – | X | |

| Sinha, 201418 | India | Rural | Focus group/ interview | 320 mothers, 61 accredited social health activists, 19 home visits | N/A | Skin-to-skin care, exclusive breastfeeding | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | – | – | |

| Sloan, 200876 | Bangladesh | Rural | Cluster randomized controlled trial | 39 888 mothers | All ages | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | 2; data available for first 2 days of life | X | X | – | – | |

| Solomons, 201217 | South Africa | Urban | Cross sectional | 30 mothers, 15 nurses | < 2500 g | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Stikes, 201343 | United States of America | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 56 nurses | N/A | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | X | |

| Strand, 201454 | Sweden | N/A | Facility evaluation | 126 staff | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Tessier, 1998119 | Colombia | Urban | Randomized controlled trial | 488 newborns | < 2001 g | Skin-to-skin care, discharge, follow-up | Adapted to extra-uterine life and able to breastfeed | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| Toma, 200390 | Brazil | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 14 mothers, 7 fathers | Premature: N/A cut-off, 1150–2300 g | N/A | Ranged from 3 to 39 days of life | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| Toma, 200791 | Brazil | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 41 mothers | < 2000 g | N/A | Mean 18 days of life | N/A | N/A | X | – | X | – | |

| Undefined author: Save the Children, 201157 | Ethiopia, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Nigeria, United Republic of Tanzania, Uganda, Bolivia, Indonesia, Nepal, Viet Nam | N/A | Facility evaluation | 12 countries | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | X | |

| Vesel, 201368 | Ghana | Rural | Cluster randomized controlled trial | 98 zones | All ages | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| Wahlberg, 1992118 | Sweden | Urban | Retrospective cohort | 66 dyads | Premature; N/A cut-off | Skin-to-skin care | N/A | N/A | N/A | – | X | X | – | |

| Waiswa, 201016 | Uganda | Rural | Focus group/ interview | 30 health-care workers and mothers, 16 facilities | Premature; N/A cut-off | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Waiswa, 20159 | Uganda | Rural | Cluster randomized controlled trial | 395 women | All newborns | Skin-to-skin care, exclusive breastfeeding | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | – | – | |

| Wobil, 201060 | Ghana | Urban | Facility evaluation | 2 facilities | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | – | X | – | |

| Zhang, 201431 | Singapore | Urban | Facility evaluation | 1 ICU | Less than 34 weeks; Less than 1500 g | Skin-to-skin care | Once eligible: stable preterm or low birthweight babies, excluding infants with poor respiratory status, invasive lines, or parents who are depressed, not willing to do kangaroo mother care, having infectious skin disease on chest, unfit physically, or with flu-like symptoms. | At least 1 hour several times per day | N/A | X | X | X | – | |

| Zwedberg, 201514 | Sweden | Urban | Focus group/ interview | 8 midwives | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | X | X | – | – | |

a ‘X means included in the study and ‘–’ means not included in the study.

ICU: intensive care unit; N/A: not available; NICU: neonatal intensive care unit.

Discussion

The core components of kangaroo mother care are skin-to-skin contact and feeding support. Additional features such as the frequency and location of early-discharge and follow-up depend on the context.57,98 Multiple factors influence the uptake of kangaroo mother care. To support the implementation of kangaroo mother care, context-specific materials such as guidelines, behaviour change materials, training curriculums, and job aids are needed. Simple interventions are more likely to be generalizable to a range of different contexts.5 When designing kangaroo mother care interventions, contextual factors and sociocultural norms need to be taken into account.

The stresses and stigma associated with having a preterm infant can hinder buy-in and support from parents and families for practicing kangaroo mother care. This problem is compounded by a lack of knowledge about kangaroo mother care among parents, families and health-care workers. Clear articulation of the benefits of kangaroo mother care for mothers and for newborns, creation of a community among parents, caregivers and health-care workers and engagement of fathers in childcare can help overcome these barriers. Collaboration among health-care workers, with shared goals and team commitments, partnering inexperienced nurses with nurses experienced in kangaroo mother care can also help.42,106,108

There are substantial barriers to kangaroo mother care within health systems, especially financing and service delivery. Dedicated financing for kangaroo mother care is critical for it to be seriously considered and implemented. Funding should consider creation of suitable environments (beds, wraps, chairs and private spaces), reducing burden of transport costs to mothers, home visits by community health workers and training parents to perform kangaroo mother care as independently as possible. Financing should be augmented with policies, guidelines, role definitions (to enable health-care workers to allocate protected time for kangaroo mother care), education (in service and pre-service) and monitoring systems that are suitably tailored for different settings (including in the community).

Logistic issues, such as time for travel and kangaroo mother care, can be challenging but could be partly overcome by incorporating targeted assistance and support and extension of visiting times. Buy-in from policy-makers is critical to promote kangaroo mother care, especially through policies like maternity and paternity leave.42,107 At the national level, kangaroo mother care should be integrated with essential newborn, maternal and child health guidelines, with appropriate monitoring and evaluation.57

We may not have captured all the programmatic reports and data available. In particular, most of the studies included in our review were published from regions with low neonatal mortality. This limits the generalizability of our findings.

Conclusion

Prolonged skin-to-skin care demands time and energy from mothers recovering from labour and carers who may have other obligations. Many women are not aware of kangaroo mother care; health workers have not been trained or, if trained, do not promote such care. Kangaroo mother care may not be socially acceptable or even conflict with traditional customs. There is lack of standardization on who should receive kangaroo mother care and the presence of admissions criteria in neonatal units.

Kangaroo mother care should be practiced more systematically and consistently to enhance adoption25 and to build trust, with motivated trained staff, education of staff and parents, clear eligibility criteria, improved referral practices and creation of communities among kangaroo mother care participants through support groups. By addressing barriers and by building trust, effective uptake of kangaroo mother care into the health system will increase and this will help to improve neonatal survival.

KMC: kangaroo mother care.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by the Saving Newborn Lives program of Save the Children Federation, Inc. We thank Ellen Boundy, Roya Dastjerdi, Sandhya Kajeepeta, Stacie Constantian, Tobi Skotnes, and Ilana Bergelson for reviewing and abstracting data. Rodrigo Kuromoto and Eduardo Toledo reviewed non-English articles. We acknowledge Kate Lobner for developing and running the search strategy.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, Perin J, Rudan I, Lawn JE, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000–13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2015. January 31;385(9966):430–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61698-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kangaroo Mother Care. A practical guide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawn JEM-KJ, Mwansa-Kambafwile J, Horta BL, Barros FC, Cousens S. ‘Kangaroo mother care’ to prevent neonatal deaths due to preterm birth complications. Int J Epidemiol. 2010. April;39 Suppl 1:i144–54. 10.1093/ije/dyq031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conde-Agudelo A, Díaz-Rossello JL. Kangaroo mother care to reduce morbidity and mortality in low birthweight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;4:CD002771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atun R, de Jongh T, Secci F, Ohiri K, Adeyi O. Integration of targeted health interventions into health systems: a conceptual framework for analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2010. March;25(2):104–11. 10.1093/heapol/czp055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuper A, Lingard L, Levinson W. Critically appraising qualitative research. BMJ. 2008;337 aug07 3:a1035. 10.1136/bmj.a1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pope C, and Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mortality rate, neonatal (per 1000 live births). Washington: The World Bank; 2014. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.DYN.NMRThttp://[cited 2014 October].

- 9.Waiswa P, Pariyo G, Kallander K, Akuze J, Namazzi G, Ekirapa-Kiracho E, et al. ; Uganda Newborn Study Team. Effect of the Uganda Newborn Study on care-seeking and care practices: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Glob Health Action. 2015;8(0):24584. 10.3402/gha.v8.24584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Namazzi G, Waiswa P, Nakakeeto M, Nakibuuka VK, Namutamba S, Najjemba M, et al. Strengthening health facilities for maternal and newborn care: experiences from rural eastern Uganda. Glob Health Action. 2015;8(0):24271. 10.3402/gha.v8.24271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chisenga JZC, Chalanda M, Ngwale M. Kangaroo Mother Care: A review of mothers’ experiences at Bwaila hospital and Zomba Central hospital (Malawi). Midwifery. 2015. February;31(2):305–15. 10.1016/j.midw.2014.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silva LJL, Leite JL, Scochi CGS, Silva LR, Silva TP, Scochi J, et al. Nurses' adherence to the Kangaroo Care Method: support for nursing care management. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2015;23(3):483–90. Epub20150715. 10.1590/0104-1169.0339.2579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higman WW, Wallace LM, Law S, Bartle NC, Blake K, Law L, et al. Assessing clinicians' knowledge and confidence to perform kangaroo care and positive touch in a tertiary neonatal unit in England using the Neonatal Unit Clinician Assessment Tool (NUCAT). J Neonatal Nurs. 2015;21(2):72–82. 10.1016/j.jnn.2014.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zwedberg S, Blomquist J, Sigerstad E. Midwives’ experiences with mother-infant skin-to-skin contact after a caesarean section: ‘fighting an uphill battle’. Midwifery. 2015. January;31(1):215–20. 10.1016/j.midw.2014.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mörelius E, Anderson GC. Neonatal nurses’ beliefs about almost continuous parent-infant skin-to-skin contact in neonatal intensive care. J Clin Nurs. 2015. September;24(17-18):2620–7. 10.1111/jocn.12877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waiswa P, Nyanzi S, Namusoko-Kalungi S, Peterson S, Tomson G, Pariyo GW. ‘I never thought that this baby would survive; I thought that it would die any time’: perceptions and care for preterm babies in eastern Uganda. Trop Med Int Health. 2010. October;15(10):1140–7. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02603.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Solomons N, Rosant C. Knowledge and attitudes of nursing staff and mothers towards kangaroo mother care in the eastern sub-district of Cape Town. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2012;25(1):33–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sinha LNK, Kaur P, Gupta R, Dalpath S, Goyal V, Murhekar M. et al. Newborn care practices and home-based postnatal newborn care programme - Mewat, Haryana, India, 2013. West Pac Surveill Response. 2014;5(3):22–9. Epub20150205. 10.5365/wpsar.2014.5.1.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh A, Yadav A, Singh A. Utilization of postnatal care for newborns and its association with neonatal mortality in India: an analytical appraisal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12(1):33. 10.1186/1471-2393-12-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shamba D, Schellenberg J, Hildon ZJ, Mashasi I, Penfold S, Tanner M, et al. Thermal care for newborn babies in rural southern Tanzania: a mixed-method study of barriers, facilitators and potential for behaviour change. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):267. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sacks E, Bailey JM, Robles C, Low LK. Neonatal care in the home in northern rural Honduras: a qualitative study of the role of traditional birth attendants. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2013. Jan-Mar;27(1):62–71. 10.1097/JPN.0b013e31827fb3fd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nimbalkar SPH, Dongara A, Patel DV, Bansal S. Usage of EMBRACE(TM) in Gujarat, India: Survey of Paediatricians. Adv Prev Med. 2014;2014:415301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguah SB, Wobil PN, Obeng R, Yakubu A, Kerber KJ, Lawn JE, et al. Perception and practice of Kangaroo Mother Care after discharge from hospital in Kumasi, Ghana: a longitudinal study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11(1):99. 10.1186/1471-2393-11-99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergh AM, Davy K, Otai CD, Nalongo AK, Sengendo NH, Aliganyira P. Evaluation of Kangaroo Mother Care Services in Uganda; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bergh AM, Banda L, Lipato T, Ngwira G, Luhanga R, Ligowe R. Evaluation of Kangaroo Mother Care Services in Malawi. Report. Washington (DC): Save the Children and the Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergh AM, Manu R, Davy K, van Rooyen E, Asare GQ, Williams JK, et al. Translating research findings into practice–the implementation of kangaroo mother care in Ghana. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):75. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bergh AM, Kerber K, Abwao S, de-Graft Johnson J, Aliganyira P, Davy K, et al. Implementing facility-based kangaroo mother care services: lessons from a multi-country study in Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):293. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arivabene JC, Tyrrell MAR. Kangaroo mother method: mothers’ experiences and contributions to nursing. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2010. Mar-Apr;18(2):262–8. 10.1590/S0104-11692010000200018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aliganyira P, Kerber K, Davy K, Gamache N, Sengendo NH, Bergh AM. Helping small babies survive: an evaluation of facility-based Kangaroo Mother Care implementation progress in Uganda. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;19:37. 10.11604/pamj.2014.19.37.3928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dalal A, Bala DV, Chauhan S. A cross-sectional study on knowledge and attitude regarding kangaroo mother care practice among health care providers in Ahmedabad District. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2014;3(3):253–6. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang SHY, Yip WK, Lim PF, Goh MZ. Evidence utilization project: implementation of kangaroo care at neonatal ICU. Int J Evid-Based Healthc. 2014. June;12(2):142–50. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunter EC, Callaghan-Koru JA, Al Mahmud A, Shah R, Farzin A, Cristofalo EA. et al. Newborn care practices in rural Bangladesh: Implications for the adaptation of kangaroo mother care for community-based interventions. Soc Sci Med. 1982;2014(122):21–30. PMID 25441314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Araújo CL, Rios CT, dos Santos MH, Gonçalves AP. [Mother Kangaroo Method: an investigation about the domestic practice]. Cien Saude Colet. 2010. January;15(1):301–7. Portuguese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gontijo TL, Meireles AL, Malta DC, Proietti FA, Xavier CC. Evaluation of implementation of humanized care to low weight newborns - the Kangaroo Method. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2010. Jan-Feb;86(1):33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sá Fed, Sá RCd, Pinheiro LMdF, Callou FEdO. Interpersonal relationships between professionals and mothers of premature from Kangaroo-Unit. Revista Brasileira em Promoção da Saúde. 2010;23(2):144–9. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haxton D, Doering J, Gingras L, Kelly L. Implementing skin-to-skin contact at birth using the Iowa model: applying evidence to practice. Nurs Womens Health. 2012. Jun-Jul;16(3):220–9. 10.1111/j.1751-486X.2012.01733.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnston CC, Campbell-Yeo M, Filion F. Paternal vs maternal kangaroo care for procedural pain in preterm neonates: a randomized crossover trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011. September;165(9):792–6. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niela-Vilén H, Axelin A, Salanterä S, Lehtonen L, Tammela O, Salmelin R, et al. Early physical contact between a mother and her NICU-infant in two university hospitals in Finland. Midwifery. 2013. December;29(12):1321–30. 10.1016/j.midw.2012.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blomqvist YT, Nyqvist KH. Swedish mothers’ experience of continuous Kangaroo Mother Care. J Clin Nurs. 2011. May;20(9-10):1472–80. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03369.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heinemann AB, Hellström-Westas L, Hedberg Nyqvist K. Factors affecting parents’ presence with their extremely preterm infants in a neonatal intensive care room. Acta Paediatr. 2013. July;102(7):695–702. 10.1111/apa.12267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dalbye R, Calais E, Berg M. Mothers’ experiences of skin-to-skin care of healthy full-term newborns–a phenomenology study. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2011. August;2(3):107–11. 10.1016/j.srhc.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee HC, Martin-Anderson S, Dudley RA. Clinician perspectives on barriers to and opportunities for skin-to-skin contact for premature infants in neonatal intensive care units. Breastfeed Med. 2012. April;7(2):79–84. 10.1089/bfm.2011.0004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stikes R, Barbier D. Applying the plan-do-study-act model to increase the use of kangaroo care. J Nurs Manag. 2013. January;21(1):70–8. 10.1111/jonm.12021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hendricks-Muñoz KD, Louie M, Li Y, Chhun N, Prendergast CC, Ankola P. Factors that influence neonatal nursing perceptions of family-centered care and developmental care practices. Am J Perinatol. 2010. March;27(3):193–200. 10.1055/s-0029-1234039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kymre IG, Bondas T. Balancing preterm infants’ developmental needs with parents’ readiness for skin-to-skin care: a phenomenological study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2013;8(1):21370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nahidi F, Tavafian SS, Haidarzade M, Hajizadeh E. Opinions of the midwives about enabling factors of skin-to-skin contact immediately after birth: a descriptive study. J Family Reprod Health. 2014. September;8(3):107–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bergh AM, Sayinzoga F, Mukarugwiro B, Zoungrana JA, Gloriose, Karera C, Ikiriza C. Evaluation of Kangaroo Mother Care Services in Rwanda; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blomqvist YT, Frölund L, Rubertsson C, Nyqvist KH. Provision of Kangaroo Mother Care: supportive factors and barriers perceived by parents. Scand J Caring Sci. 2013. June;27(2):345–53. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01040.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calais E, Dalbye R, Nyqvist Kh, Berg M. Skin-to-skin contact of fullterm infants: an explorative study of promoting and hindering factors in two Nordic childbirth settings. Acta Paediatr. 2010. July;99(7):1080–90. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01742.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Castiblanco López N, Muñoz de Rodríguez L. Vision of mothers in care of premature babies at home. Av Enferm. 2011;29(1):120–9. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bazzano A, Hill Z, Tawiah-Agyemang C, Manu A, Ten Asbroek G, Kirkwood B. Introducing home based skin-to-skin care for low birth weight newborns: a pilot approach to education and counseling in Ghana. Glob Health Promot Educ. 2012. September;19(3):42–9. 10.1177/1757975912453185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferrarello D, Hatfield L. Barriers to skin-to-skin care during the postpartum stay. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2014. Jan-Feb;39(1):56–61. 10.1097/01.NMC.0000437464.31628.3d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maastrup R, Bojesen SN, Kronborg H, Hallström I. Breastfeeding support in neonatal intensive care: a national survey. J Hum Lact. 2012. August;28(3):370–9. 10.1177/0890334412440846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strand H, Blomqvist YT, Gradin M, Nyqvist KH. Kangaroo mother care in the neonatal intensive care unit: staff attitudes and beliefs and opportunities for parents. Acta Paediatr. 2014. April;103(4):373–8. 10.1111/apa.12527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bergh AM, Sylla M, Traore IMA, Diall Bengaly H, Kante M, Kaba DN. Evaluation of Kangaroo Mother Care Services in Mali. Report. Washington (DC): Save the Children; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hendricks-Muñoz KD, Mayers RM. A neonatal nurse training program in kangaroo mother care (KMC) decreases barriers to KMC utilization in the NICU. Am J Perinatol. 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scaling Up Kangaroo Mother Care. Report of Country Survey Findings. Report. Washington (DC): Save the Children - Saving Newborn Lives Program; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hill Z, Tawiah-Agyemang C, Manu A, Okyere E, Kirkwood BR. Keeping newborns warm: beliefs, practices and potential for behaviour change in rural Ghana. Trop Med Int Health. 2010. October;15(10):1118–24. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02593.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bergh AM, Manu R, Davy K, Van Rooyen E, Quansah Asare G, Awoonor-Williams J, et al. Progress with the implementation of kangaroo mother care in four regions in Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2013. June;47(2):57–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wobil P. Report on the kangaroo mother care project at Komfo Anokye teaching hospital in Kumasi. Ghana: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Keshavarz M, Haghighi NB. Effects of kangaroo contact on some physiological parameters in term neonates and pain score in mothers with cesarean section. Koomesh. 2010;11(2):91–9. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abul-Fadl AM, Shawky M, El-Taweel A, Cadwell K, Turner-Maffei C. Evaluation of mothers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice towards the ten steps to successful breastfeeding in Egypt. Breastfeed Med. 2012. June;7(3):173–8. 10.1089/bfm.2011.0028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gonya J, Nelin LD. Factors associated with maternal visitation and participation in skin-to-skin care in an all referral level IIIc NICU. Acta Paediatr. 2013. February;102(2):e53–6. 10.1111/apa.12064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lemmen D, Fristedt P, Lundqvist A. Kangaroo care in a neonatal context: parents’ experiences of information and communication of nurse-parents. Open Nurs J. 2013;7:41–8. 10.2174/1874434601307010041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hendricks-Muñoz KD, Li Y, Kim YS, Prendergast CC, Mayers R, Louie M. Maternal and neonatal nurse perceived value of kangaroo mother care and maternal care partnership in the neonatal intensive care unit. Am J Perinatol. 2013. November;30(10):875–80. 10.1055/s-0033-1333675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Flynn A, Leahy-Warren P. Neonatal nurses' knowledge and beliefs regarding kangaroo care with preterm infants in an Irish neonatal unit. J Neonatal Nurs. 2010;16(5):221–8. 10.1016/j.jnn.2010.05.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bergh AM, Rogers-Bloch Q, Pratomo H, Uhudiyah U, Sidi IP, Rustina Y, et al. Progress in the implementation of kangaroo mother care in 10 hospitals in Indonesia. J Trop Pediatr. 2012. October;58(5):402–5. 10.1093/tropej/fmr114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vesel L, ten Asbroek AH, Manu A, Soremekun S, Tawiah Agyemang C, Okyere E, et al. Promoting skin-to-skin care for low birthweight babies: findings from the Ghana Newhints cluster-randomised trial. Trop Med Int Health. 2013. August;18(8):952–61. 10.1111/tmi.12134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brimdyr K, Widström AM, Cadwell K, Svensson K, Turner-Maffei C. A Realistic Evaluation of Two Training Programs on Implementing Skin-to-Skin as a Standard of Care. J Perinat Educ. 2012. Summer;21(3):149–57. 10.1891/1058-1243.21.3.149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mörelius E, Angelhoff C, Eriksson J, Olhager E. Time of initiation of skin-to-skin contact in extremely preterm infants in Sweden. Acta Paediatr. 2012. January;101(1):14–8. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02398.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Crenshaw JT, Cadwell K, Brimdyr K, Widström AM, Svensson K, Champion JD, et al. Use of a video-ethnographic intervention (PRECESS Immersion Method) to improve skin-to-skin care and breastfeeding rates. Breastfeed Med. 2012. April;7(2):69–78. 10.1089/bfm.2011.0040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Santos LM, Morais RA, Mirada JOF, Santana RCB, Oliveira VM, Nery FS. Percepção materna sobre o contato pele a pele com o prematuro através da posição canguru. Rev Pesquisa Cuidado Fundamental online. 2013;5:3504–14. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cooper L, Morrill A, Russell RB, Gooding JS, Miller L, Berns SD. Close to me: enhancing kangaroo care practice for NICU staff and parents. Adv Neonatal Care. 2014. December;14(6):410–23. 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Silva RA, Barros MC, Nascimento MHM. Conhecimento de técnicos de enfermagem sobre o método canguru na unidade neonatal. Rev Bras Prom Saude. 2014;27(1). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gontijo TL, Xavier CC, Freitas MI. Avaliacao da implantacao do Metodo Canguru por gestores, profissionais e maes de recem-nascidos [Evaluation of the implementation of Kangaroo Care by health administrators, professionals, and mothers of newborn infants]. Cad Saude Publica. 2012. May;28(5):935–44. [.] 10.1590/S0102-311X2012000500012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sloan NL, Ahmed S, Mitra SN, Choudhury N, Chowdhury M, Rob U, et al. Community-based kangaroo mother care to prevent neonatal and infant mortality: a randomized, controlled cluster trial. Pediatrics. 2008. May;121(5):e1047–59. 10.1542/peds.2007-0076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]