Abstract.

Cocaine abuse can lead to cerebral strokes and hemorrhages secondary to cocaine’s cerebrovascular effects, which are poorly understood. We assessed cocaine’s effects on cerebrovascular anatomy and function in the somatosensory cortex of the rat’s brain. Optical coherence tomography was used for in vivo imaging of three-dimensional cerebral blood flow (CBF) networks and to quantify CBF velocities (CBFv), and multiwavelength laser-speckle-imaging was used to simultaneously measure changes in CBFv, oxygenated () and deoxygenated hemoglobin () concentrations prior to and after an acute cocaine challenge in chronically cocaine exposed rats. Immunofluorescence techniques on brain slices were used to quantify microvasculature density and levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). After chronic cocaine (2 and 4 weeks), CBFv in small vessels decreased, whereas vasculature density and VEGF levels increased. Acute cocaine further reduced CBFv and decreased and this decline was larger and longer lasting in 4 weeks than 2 weeks cocaine-exposed rats, which indicates that risk for ischemia is heightened during intoxication and that it increases with chronic exposures. These results provide evidence of cocaine-induced angiogenesis in cortex. The CBF reduction after chronic cocaine exposure, despite the increases in vessel density, indicate that angiogenesis was insufficient to compensate for cocaine-induced disruption of cerebrovascular function.

Keywords: brain imaging, optical coherence Doppler tomography, multiwavelength laser speckle imaging, cocaine, ischemia, angiogenesis

1. Introduction

Cocaine is a highly addictive drug and its sympathomimetic effects are associated with adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular effects. Its cerebrovascular effects can result in strokes, hemorrhages, and transient ischemic attacks.1–3 These complications are partly attributed to cocaine-induced cerebral vasospasm and ischemia.2–5 Brain imaging techniques including positron emission tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and more recently, optical coherence Doppler tomography (ODT), have revealed marked decreases in cerebral blood flow (CBF) and cerebral blood volume, along with the presence of cerebral vasospasm, both in clinical cocaine abusers and in cocaine-exposed laboratory animals.6–8 However, the response of the brain to cocaine-induced decreases in CBF and ischemia are still not well elucidated, nor is the influence of these effects on the clinical presentation as a function of acute and chronic cocaine exposures understood.

It is recognized that cerebral ischemia triggers angiogenesis in rodents9 and humans,10 which is a process that involves vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).11 Although cocaine exposure can trigger microischemia,8 no study to our knowledge has evaluated the effects of chronic cocaine on cerebral angiogenesis. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that cocaine-induced ischemia would trigger angiogenesis.

To test this hypothesis, we used optical imaging to simultaneously measure the effects of acute and chronic cocaine on CBF, hemoglobin oxygenation [] in vivo in the somatosensory cortex and used immunohistochemistry in brain slices to measure microvasculature density and VEGF, which is a sensitive marker of angiogenesis.12 Specifically, we integrated ODT and multiwavelength laser speckle imaging (MW-LSI) to enable concurrent assessment of changes in the cerebrovasculature in vivo along with the associated hemodynamic and metabolic measurements in the rat’s somatosensory cortex. While ODT was used for three-dimensional (3-D) imaging of the vasculature and for quantitative CBFv assessments, MW-LSI was applied for the simultaneous detection of dynamic changes in CBFv (i.e., ), oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin concentrations (i.e., and Δ[HbR]) prior to and after an acute cocaine challenge. In addition, ex vivo fluorescence histochemistry was performed on brain slices to assess the effects of chronic cocaine on microvascular density and VEGF levels in the cerebral cortex.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Pretreatments

Adult Sprague–Dawley male rats (250 to , ) were divided into four different groups, as summarized in Table 1, in which some animals received daily intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of 0.9% saline () or cocaine HCl () for consecutive 2 or 4 weeks, which were administered in their home cage. We chose a cocaine dose of (i.p.) since this dose results in cocaine plasma levels consistent to those observed in cocaine abusers.13 In vivo imaging experiments were performed after 1-day withdrawal from pretreatments.

Table 1.

Experimental design: animal groups, pretreatment and imaging approaches.

| Animal groups | Pretreatment | Drug challenge during experiment | Imaging approach | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | A Control () | 2-week control () | 0.9% saline (, i.p.) | N/A | In vivo (3-D OCT) |

| 4-week control () | |||||

| B Cocaine (2 weeks, ) | Cocaine (2 weeks) (, i.p.) | ||||

| C Cocaine (4 weeks, ) | Cocaine (4 weeks) (, i.p.) | ||||

| Group 2 | A Control () | 2-week control () | 0.9% saline ( i.p.) | N/A | Ex vivo(fluorescein isothiocyanate-Dextran) |

| 4-week control () | |||||

| B Cocaine (2 weeks, ) | Cocaine (2 weeks) (, i.p.) | ||||

| C Cocaine(4 weeks, ) | Cocaine (4 weeks) (, i.p.) | ||||

| Group 3 | A Control () | 2-week control () | 0.9% saline ( i.p.) | N/A | Ex vivo (VEGF) |

| 4-week control () | |||||

| B Cocaine (2 weeks, ) | Cocaine (2 weeks) (, i.p.) | ||||

| C Cocaine (4 weeks, ) | Cocaine (2 weeks) (, i.p.) | ||||

| Group 4 | A Control () | 2-week control () | 0.9% saline (, i.p.) | 0.9% saline (, i.v.) | In vivo (MW-LSI) |

| 4-week control () | |||||

| B Cocaine (2 weeks, ) | Cocaine (2 weeks) (, i.p.) | Cocaine (, i.v.) | |||

| C Cocaine(4 weeks, ) | Cocaine (4 weeks) (, i.p.) | Cocaine (, i.v.) | |||

2.2. Surgical Preparation for In Vivo Imaging

Rats were anesthetized and ventilated with 1.5% to 3% isoflurane mixed in pure oxygen during the surgery. A femoral artery was catheterized for continuous arterial blood pressure monitoring and a femoral vein from the same side was catheterized for drug administration. The rat was then positioned in a stereotaxic frame (KOPF 900) to minimize brain motion. A cranial window () was created above the right somatosensory cortex (AP: to ; LR to ). After the dura was carefully removed, the exposed brain surface was immediately covered with 1.25% agarose gel and affixed with a -thick glass coverslip using biocompatible cyanocrylic glue to maintain normal cranial pressure. During the surgery and the later imaging of the brain, the physiological state of the animal was continuously monitored, including electrocardiography, mean arterial blood pressure (MABP), respiration rate, and body temperature (Module 224002, Small Animal Instruments). All of the procedures were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Stony Brook University.

2.3. In Vivo Optical Imaging

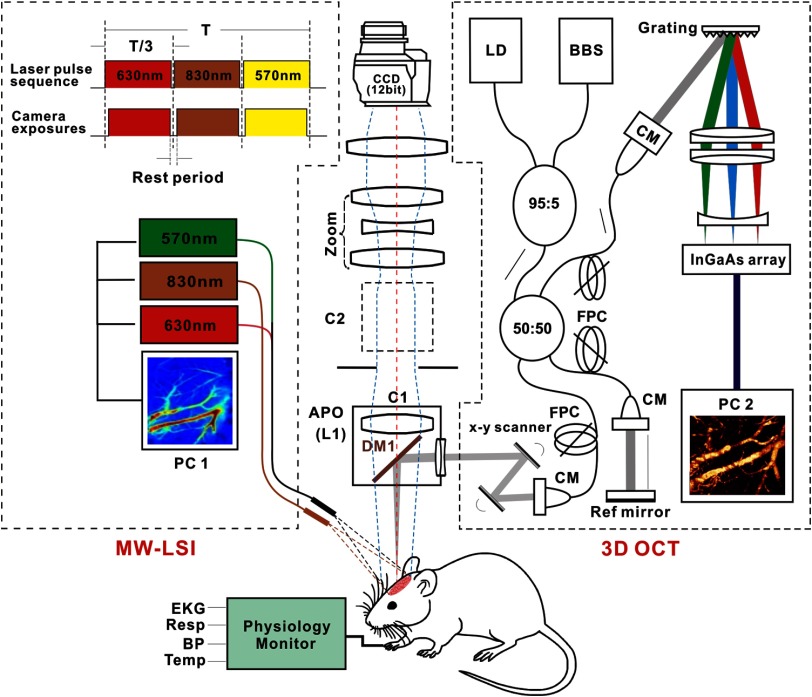

Figure 1 shows a multimodality optical imaging platform employed to acquire all the in vivo image data presented in this study, in which 3-D ODT and MW-LSI were integrated into a modified zoom fluorescence microscope (AZ100, Nikon) allowing for simultaneous imaging. For 3-D ODT, a fast spectral-domain OCT system illuminated with a broadband source (, ; Inphenix) was integrated into the zoom microscope via a custom dichroic mirror (DM1) reflecting . The collimated light beam () exiting the sample arm of the OCT engine was transversely scanned by a pair of servo mirrors (VM500, Cambridge Tech.), focused by an achromate (), and reflected by DM1 onto the cortex. The backscattered light from brain was recombined with the reference light and detected by a high-speed linear spectrograph (a 1024-pixel InGaAs array; Goodrich). By synchronizing with servo mirrors, two-dimensional (2-D) OCT image ( cross section) was acquired at up to 140 fps and 3-D OCT was acquired by additional -axis scanning. The acquired OCT dataset were transferred to a solid-state drive on a workstation in which graphics processing unit accelerated computing enabled parallel image processing for real-time display of 2-D and 3-D images of both amplitude (i.e., OCT, OCA or optical coherence angiography) and phase (e.g., CBFv) distributions on the cortical brain. The axial resolution of was determined by the coherence length and the transverse resolution of was determined by the focusing optics (). A typical field of view (FOV) of on the rat’s cortex was acquired; and specific raster scanning schemes (e.g., dense sampling along -axis) were implemented to optimize flow detection sensitivity for 3-D ODT and simultaneous 3-D OCA imaging (vasculature). For MW-LSI, two light emitting diodes () at the wavelengths of and were coupled into a fiber bundle () for illumination of the exposed cortex to image the dynamical changes of total blood volume (), deoxygenated hemoglobin (), and thus oxygenated hemoglobin ().14,15 In addition, a pigtailed diode laser (60 mW) at was delivered through 1:3 monomode fiber couplers (NA/0.12) to a ring illuminator (C1) for LSI imaging. All three channels were pulse modulated via a time-base (time-sharing) for sequential “wavelength-multiplexed” imaging at up to 16 Hz. Synchronized with spectral illumination, the backreflection from the exposed cortex (e.g., a FOV of ) in each channel was collected via the microscope optics () and imaged by a 16-bit sCMOS camera (Zyla 5.5, Andor). Changes in [] and [HbR] were calculated directly through the time-lapse images at and ;16 the LSI flow image series were reconstructed by computing the speckle variances in both spatial domain (i.e., calculating speckle variance within adjacent pixels in each frame) and temporal domain (i.e., across adjacent frames).17 The 2-D flow images by LSI were coregistered with 3-D CBFv images by ODT to map the absolute flow rates of individual vessels and identify their flow types (venous or arterial flows), but LSI was used to track fast dynamic features of the vascular trees after acute cocaine.

Fig. 1.

A schematic diagram of a multimodality optical imaging platform that combines 3-D optical coherence tomography (3-D OCT) and multiple wavelength laser speckle contrast imaging (MW-LSI) used in this study. The left dashed box represents the MW-LSI, which consists of three alternatively switching light sources, e.g., a laser diode for CBFv imaging and two LEDs at for oxygenation imaging. The right dashed box is a 1310-nm OCT system. SM, single mode; CM, collimator; BBS, broadband source (); LD, aiming laser (); FPC, fiber-optic polarization controller. Left dash box: modified zoom microscope. C1, C2: epi-illumination cube 1, 2. DM1: dichroic beam splitter (); L1: (, ).

During the in vivo studies, 3-D OCA and ODT images were acquired by the OCT system to evaluate the effects of chronic cocaine on vascular density and CBFv in the somatosensory cortex of rats in Group 1 (A–C) in Table 1. MW-LSI images were captured every 2 min starting 10 min before saline or cocaine injection (i.e., baseline) till 30 min postsaline or cocaine injection, so that the dynamic characteristics of cocaine or saline injection on CBF, [HbR] and [] were derived for each rat in Group 4 (A–C).

2.4. Ex Vivo Assessment of Microvascular Density in Cortex

To further study the effect of cocaine on vascular density, we used ex vivo fluorescence measurement to assess microvascular density in the brain of animals with or without chronic cocaine pretreatment. As listed in Group 2 (A–C) in Table 1, animals were sacrificed 24 h after pretreatment withdrawal of either saline (, i.p., Group 2A) or cocaine (, i.p.) given for 2 weeks (Group 2B) or 4 weeks (Group 2C). fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-Dextran (mol wt , ), a fluorescence dye, was intracardiacally infused () at 1 min before the animal was euthanized. Then, the whole brain of the rat was removed from the skull, immediately immersed and incubated in cold 4% formaldehyde solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts) overnight at 4°C. The brain was then continually immersed and fixed with increasing sucrose (, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri) gradients from 10% to 20% and 30%. The prepared brain was then embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and was cut into thick coronal slices at bregma on the cryostat (Leica CM3050 S, Leica Biosystems, Richmond, Illinois). Five or more fluorescence images were taken for each brain slice in the region of interest (ROI) with a objective using a fluorescence microscope (E80i, Nikon Instruments).

2.5. Assessment of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Histochemistry in Cortex

Animals from Group 3 were used for VEGF immunofluorescence assessment, including control animals (Group and ) and animals with 2-week and 4-week cocaine pretreatment (i.e., Group 3B and Group 3C, respectively). After 24-h withdrawal from the pretreatment, each animal was perfused with 4% formaldehyde (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and brains were collected, postfixed in 4% formaldehyde solution overnight, and kept in 30% sucrose until they sank to the bottom of the tube. Then the brains were cryosectioned into -thick coronal slices (Leica CM3050 S, Leica Biosystems). The brain slices were first blocked with 5% goat serum (ab 7481, Abcam) for 30 min. Then the samples were incubated with anti-VEGF antibody (ab 52917, Abcam) at 1:200 dilution for 1 h, followed by a further 1-h incubation with an Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated Goat Antirabbit IgG H&L (1:1000 ab150077, Abcam). The slices were finally mounted with 2-[4-(aminoiminomethyl)phenyl]-1H-indole-6-carboximidamide, dihydrochloride Fluoromount-G® (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, Alabama). All procedures were done at room temperature. The negative controls underwent all the procedures in parallel with other slices except that they were incubated in normal antibody dilution buffer ( normal goat serum Triton X-100) instead of in the anti-VEGF antibody. All VEGF fluorescence images were acquired at the same exposure time with a Nikon E80i fluorescence microscope.

2.6. Image Processing and Data Analysis

Reconstruction of 3-D OCA images for assessing the vascular density was computed based on a speckle variation approach using Hessian filtering,18,19 and reconstruction of 3-D ODT image for assessing CBFv was based on Doppler flow reconstruction algorithms, such as phase subtraction method or phase intensity method to enhance minute flow detection.8,20 To quantify size-dependent vasoconstriction induced by chronic cocaine, we divided the vessels in the FOV as small ( to ), medium ( to ), and large () vessels. The vascular density was quantified by the fill factor (FF), defined as the ratio of the number of pixels occupied by vessels to the total number of pixels within the selected ROI, i.e.,

| (1) |

where (e.g., ) represents the total number of ROIs selected in each image.

For MW-LSI images, cocaine or saline induced changes, e.g., () and were calculated directly through the time-lapse images at (i.e., [HbT]) and (i.e., [HbR]); the LSI flow image series were reconstructed by computing the speckle variances at in both spatial domain (i.e., calculating speckle variance within adjacent pixels in each frame) and temporal domain (i.e., across adjacent frames).21 Several ROIs in avascular areas (avoiding of apparent vessels) were selected to compute tissue and at each time point.

To assess microvascular density from the ex vivo fluorescent images, we adopted the Otsu threshold selection method, an unsupervised segmentation algorithm which utilized discriminant analysis (e.g., measurement of separability) to evaluate the “goodness” of threshold and thus automatically select an optimal threshold.22 Briefly, Otsu’s method is based on the separation of graylevel class (objects) from (background) by a threshold . To obtain the optimal threshold, the total variance of levels :

| (2) |

as a function of threshold level , was adopted as the discriminant criterion whose maximum corresponds to the optimal threshold . and are based on the class variance and class mean, respectively, whose relation satisfies the following equations:

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

where and were mean graylevel and variance of corresponding class, respectively. denotes the probability of class occurrence:

| (6) |

For microvascular density analysis, the Otsu’s thresholding method was applied to each fluorescence image (grayscale image), converting it into a binarized image for further analysis by using ImageJ software for counting the vessel numbers within the FOV of the image. The variation of the threshold from image to image was small and negligible; thus, the same threshold was applied in the density quantification. The microvasculature density of a unit area was defined as the ratio of the vessel number over the actual size of the FOV () in each area. To get the vessel density of each area from each animal, densities of five randomly chosen images were averaged.

VEGF levels were analyzed by calculating the percentage of VEGF fluorescent pixels over the total pixels within the ROI of the image to result in the % area of VEGF. Specifically, ImageJ was used to analyze all the VEGF fluorescently labeled images (grayscale images), with a preset threshold (T) defined by the averaged graylevel of multiple selected background ROI () to segment VEGF signal against its background noise:

| (7) |

where denotes the mean greylevel of th background ROI.

The expression level of VEGF was calculated by taking the ratio of the pixels with the VEGF fluorescence over the total pixels of the ROI image (presented as % area). Three randomly chosen images of the somatosensory cortex from each rat were analyzed and averaged for statistical comparisons.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as . and -values were analyzed by performing paired -test or one-way factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) test (Systat software) to determine differences between groups. Significance was set at (double tail).

3. Results

3.1. Chronic Cocaine Decreased Cerebral Blood Flow Velocity Across the Cerebrovascular Tree

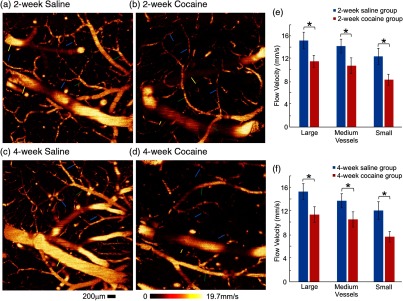

Figures 2(a) and 2(c) show CBFv images of the somatosensory cortex in control rats with saline pretreatment (0.9% saline, , i.p.) for 2 and 4 weeks, and Figs. 2(b) and 2(d) show the images for rats exposed to chronic cocaine (, i.p.) for 2 and 4 weeks. Compared with control animals, chronic cocaine exposure for either 2 or 4 weeks significantly decreased CBFv across the cerebrovascular network. Figures 2(e) and 2(f) summarize the quantitative comparisons of CBFv in large (), medium (), and small vessels () from rats with or without cocaine pretreatment [Group 1(A–C), Table 1]. Specifically, after 2-week cocaine pretreatment (Group 1B, Table 1), basal CBFv decreased in large vessels from in control rats to (); in medium vessels, it decreased from to (); and in small vessels, it decreased from to (). For the 4-week cocaine-exposed group (Group 1C, Table 1), basal CBFv in big vessels was reduced from in control rats to (); in medium vessels, it was decreased from to (), and in small vessels from to () [Fig. 2(f)].

Fig. 2.

Chronic cocaine decreased CBFv across the cerebrovascular tree. Quantitative CBFv (ODT) images in the somatosensory cortex of the (a, c) saline-treated control groups versus (b, d) those of the chronic cocaine-treated groups for 2 and 4 weeks. Image sizes are , . Yellow, green, and blue arrows are used to demonstrate the large (; ), medium (; ), and small vessels (; ), respectively. (e, f) Statistical comparisons of CBFv among various groups, indicating the significant decreases of CBFv across the whole vascular trees. * significant differences between saline- and cocaine-treated groups (, ; ).

A comparison between the cocaine groups showed that CBFv in small vessels was significantly lower after 4-week than 2-week cocaine exposures, e.g., versus , respectively (). Therefore, these results show that chronic cocaine decreased CBFv across all blood vessel sizes in the cerebral cortex and that in small vessels, the decreases were larger after 4 weeks than 2 weeks of cocaine exposures.

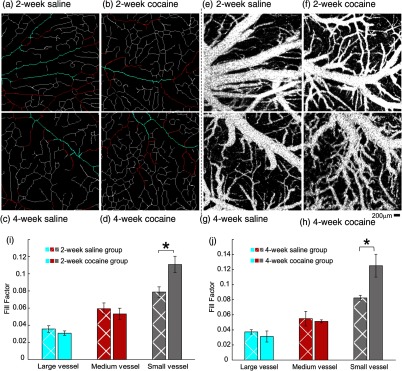

3.2. Chronic Cocaine Increased Density of Small Vessels in Cortex: In Vivo Measures

Figures 3(a) through 3(d) illustrate the skeletonized cerebral vasculature maps extracted from the OCA images [Figs. 3(e) through 3(h)] in the somatosensory cortex. Different colors were selected to represent vessels within three different diameter ranges, i.e., “blue” for large vessels (), “red” for medium vessels ( to ), and “white” for small vessels (), and their vascular densities were quantified by the corresponding FFs, defined above in Eq. (1).

Fig. 3.

Chronic cocaine increased the density of small vessels in the somatosensory cortex in vivo. Skeletonized vasculature maps of the rat somatosensory cortex among (a, c) saline-treated control groups and (b, d) chronic cocaine-treated groups for 2 and 4 weeks. Image sizes are (scale bar: ). “Blue,” “red,” and “white” illustrate the large (), medium (), and small () vessels, respectively. (e–h) Optical coherence angiography (OCA) of the rat somatosensory cortex. (i, j) Statistical comparisons of vascular density change elicited by chronic cocaine indicate that the vascular density of small vessels increased in both cocaine groups. In the 2-week cocaine group, the FF increased from in control to (). For the 4-week cocaine group, the density increased from in control to (). A significant difference was found between saline-treated and cocaine-treated groups, but no significant difference was found between 2-week and 4-week cocaine groups (, ).

Figures 3(i) and 3(j) show the comparisons for FFs in large, medium, and small vessels between control rats ( in total) with 2-week or 4-week saline pretreatment and 2-week [Fig. 3(i)] or 4-week [Fig. 3(j)] cocaine pretreatments. Vascular density of small vessels increased in both cocaine groups [Figs. 3(i) and 3(j)]. For the 2-week cocaine group, the FF increased from in control to () and for the 4-week cocaine group, it increased from in control to (). The differences between the 2-week (Group 1B) and the 4-week (Group 1C) cocaine groups were not significant (). In contrast for the large and medium vessels, there were no significant differences in vascular density among control and 2-week [Fig. 3(i)] and 4-week [Fig. 3(j)] cocaine pretreatment groups.

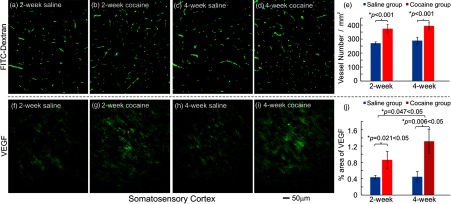

3.3. Chronic Cocaine Increased Microvascular Density and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Levels in the Cortex: Ex Vivo Measures

In parallel to in vivo image analyses of cocaine-induced vascular density changes, ex vivo histochemistry results are presented in Figs. 4(a)–4(d), which correspond to micrographs of the microvasculature labeled with FITC-Dextran fluorescence indicator in control rats (, Group 2A, Table 1) and in rats pretreated with cocaine for 2 and 4 weeks (, 2 weeks for Group 3B, , 4 weeks for Group 2C, Table 1). Figure 4(e) compares the microvasculature densities in the somatosensory cortex between control and chronic cocaine rats. It indicates that microvasculature density, in which control rats were for the 2-week saline and for the 4-week saline, was significantly higher in rats exposed to cocaine corresponding to for the 2-week exposures () and to for the 4-week exposures (). The difference between the 2- and 4-week cocaine groups did not reach significance ().

Fig. 4.

Chronic cocaine increased microvascular density and VEGF expression levels in the somatosensory cortex. Micrographs of the microvasculature (FITC-Dextran) in the somatosensory cortex (a, c) after saline pretreatment and (b, d) after chronic cocaine administration. (e) Statistical comparisons of microvasculature density (, , ). Micrographs of VEGF expression in (f, h) saline-treated rats and (g, i) cocaine-treated rats. Scale bar: ; (j) Statistical comparisons of VEGF expression in the somatosensory cortex among all groups (, ; ). *: significant differences between saline-treated and cocaine-treated groups.

Figures 4(f)–4(i) illustrate the VEGF fluorescence from the somatosensory cortex in control and chronic cocaine rats. It shows that VEGF expression was increased after chronic cocaine. For the 2-week cocaine group (i.e., Group 3B), VEGF fluorescence increased from to (% area of VEGF, ) and for the 4-week cocaine group (i.e., Group 3C, Table 1), it increased from to (). Comparisons between the cocaine groups showed that VEGF levels were significant higher in the 4-week than the 2-week cocaine groups ().

3.4. Cortical Cerebral Blood Flow Volume was Transiently Decreased with Acute Cocaine Challenge and was Longer Lasting in 4-week Than 2-week Cocaine Exposed Rats

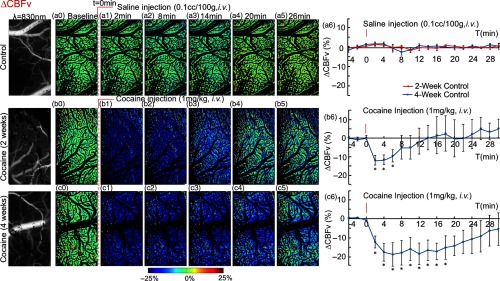

Figure 5 illustrates the dynamic CBFv maps in the somatosensory cortex obtained with MW-LSI from a different group of animals (Group 4, Table 1), in control (Group 4A) and 2-week (Group 4B) and 4-week cocaine rats (Group 4C). The grayscale images at the first of each row represent baseline CBFv maps (), the color image series show the ratio images of CBFv at various time points (e.g., , 8, 14, 20, and 26 min) after saline or cocaine challenge versus its baselines in order to track CBFv changes with time. For example, Figures 5(a0)–5(a5) show the CBFv changes in a control rat before (i.e., ) and after saline (, i.v.). The “green” tone across the FOV reflects the level of blood flow in tissue, which does not change after saline injection. Figure 5(a6) summarizes the time course of CBFv changes for control rats (Group 4A) in response to saline, showing no significant change in CBFv before and after saline administration.

Fig. 5.

Acute cocaine abruptly decreased CBFv in somatosensory cortex of chronically cocaine-exposed rats. Dynamic CBFv maps in the somatosensory cortex of control rats with 2-week (red curve) and 4-week (blue curve) saline-treatment (a0–a5), and cocaine treated rats treated for 2 weeks (b0–b5) or 4 weeks (c0–c5) in response to saline (, i.v.) or acute cocaine (, i.v.). The first column presents the laser speckle contrast images taken at , reflecting the CBFv changes in this area. (a6, b6, c6) Time courses of CBF changes in response to saline or cocaine among all groups, indicating an abrupt and transient CBFv decrease after acute cocaine in chronically exposed cocaine rats and this decrease was more dramatic and longer-lasting in the 4-week than the 2-week cocaine rats. *significant differences between saline- and cocaine-treated groups (, , ).

Figures 5(b0) through 5(b5) illustrate the CBFv changes to an acute cocaine challenge (, i.v.) in a rat exposed to 2 weeks of cocaine (Group 4B, Table 1), where the “blue” tone reveals global transient CBFv decrease in somatosensory cortex till when it returns to baseline levels. Figure 5(b6) summarizes the time course of CBFv changes for the 2-week cocaine rats (Group 4B) exposed to acute cocaine, showing an abrupt decrease in CBFv within of cocaine injection (minimum decrease ; ) followed by a gradual recovery after 14-min postinjection.

Figures 5(c0) through 5(c6) illustrate the CBFv changes to an acute cocaine challenge (, i.v.) in a rat exposed to 4 weeks of cocaine (Group 4C, Table 1), showing also an abrupt CBFv decrease within to 6 min after cocaine injection (minimum ; ). The decline in CBFv was significantly longer lasting than for the 2-week cocaine pretreated animals and did not fully recover even after 30-min postcocaine injection [Fig. 5(c6)]. Specifically, in 2-week cocaine rats (Group 4B), CBFv recovered within to baseline levels (i.e., ), whereas in 4-week cocaine rats (Group 4C), CBFv was still below baseline; the differences between the groups were significant ().

3.5. and HbR in Somatosensory Cortex After Acute Cocaine Challenge in Chronic Cocaine Rats

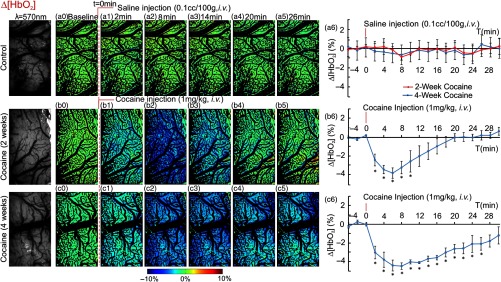

Figure 6 shows the dynamic changes of [] after saline (, i.v.) in control rats (Group 4A, Table 1) and after acute cocaine (, i.v.) in cocaine pretreated for 2-week (Group 4B, Table 1) or 4-week rats (Group 4C, Table 1). Saline injection did not change [] [maps in Figs. 6(a0) through 6(a5) and time course in Fig. 6(a6)]. By contrast, acute cocaine in the 2-week exposed rats significantly decreased [] (; ) at postcocaine [Figs. 6(b1) through 6(b3)] and [] was within to 22 min, indicating that at that time, it had returned to baseline [Fig. 6(b6)]. In the 4-week cocaine group, decreases in [] were significantly larger than for the 2-week group (; within to 8 min) and longer-lasting (e.g., still within to 22 min postinjection) () and did not recover even after 30-min postinjection [Fig. 6(c6)].

Fig. 6.

Acute cocaine decreased [] in somatosensory cortex of chronically cocaine exposed rats. Dynamic changes of tissue [] in the somatosensory cortex of control rats with 2-week (red curve) and 4-week (blue curve) saline-treatment (a0–a5), and the rats treated with chronic cocaine for 2 weeks (b0–b5) and 4 weeks (c0–c5) in response to saline (, i.v.) or cocaine (, i.v.). The first column presents the images taken at , reflecting the concentration of total hemoglobin in tissue. (a6, b6, c6) Time courses of [] changes in response to saline or cocaine among all groups. [] did not fluctuate after a saline injection in control rats while a single dose of cocaine dramatically decreased [] in cocaine exposed rats. The varying pattern of [] was similar with that of CBFv. *significant differences between saline- and cocaine-treated groups (, , ).

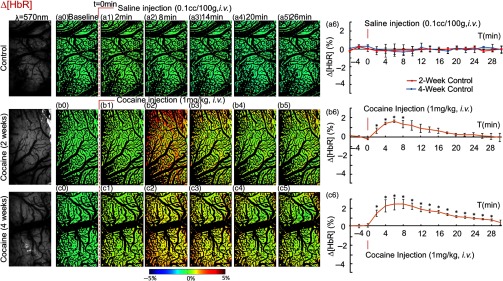

Figure 7 shows the comparison of the dynamic changes in deoxygenated hemoglobin concentration [HbR]. Again, saline injection did not change [HbR] in control rats [Figs. 7(a0) through 7(a6)], but acute cocaine triggered a significant [HbR] increase to (, ) at after cocaine injection in the 2-week and to (, ) at in the 4-week cocaine group and at [HbR] changes were and . [HbR] returned to baseline after 20-min postcocaine in the 2-week group but in the 4-week group, [HbR] were still elevated over the baseline 28-min postcocaine.

Fig. 7.

Acute cocaine increased [HbR] in somatosensory cortex of chronically cocaine exposed rats. Dynamic changes in tissue [HbR] of control rats with 2-week (red curve) and 4-week (blue curve) saline-treatment (a0–a5), and of rats treated with chronic cocaine for 2 weeks (b0–b5) and 4 weeks (c0–c5) in response to saline (, i.v.) or cocaine (, i.v.). The first column presents images taken at , reflecting the concentration of total hemoglobin in tissue. (a6, b6, c6) Time courses of [HbR] variations in response to saline or cocaine among all groups. In contrast to the decrease of CBFv and [], [HbR] increased in response to acute cocaine in cocaine pretreated rats. *significant differences between saline-treated and cocaine-treated groups (, , ).

4. Discussion

Here, we document that chronic cocaine (2- and 4-week exposures) increases small vessel density and that it increases VEGF in the cerebral cortex (shown in somatosensory cortex) consistent with chronic cocaine inducing angiogenesis. Despite evidence of angiogenesis, we also show that acute cocaine in the chronic cocaine exposed animals significantly reduced CBFv and while increasing HbR, an effect that was more accentuated after 4 weeks than after 2 weeks of cocaine exposures. These results are consistent with chronic cocaine sensitizing the cerebral vessels to the reductions in CBFv triggered by acute cocaine, temporarily triggering ischemia (decrease in and increase in HbR). Taken together, our studies provide evidence that chronic cocaine triggers angiogenesis in the cortex and that this is likely due to cocaine-induced ischemia.

Angiogenesis has been reported after the onset of cerebral ischemia in rodents9 and in humans.10 We had previously shown that cocaine-induced cerebral microischemia in the rodent brain8 consistent with clinical reports of cocaine-induced transient ischemic attacks and strokes,1–3 but no study to our knowledge had evaluated whether this triggered angiogenesis. The results from our current study showed on the one hand that acute cocaine triggers ischemia,8 and on the other hand that cocaine’s reductions of CBF are exacerbated with longer cocaine exposures while in parallel, there are increases in new blood vessels and in VEGF, which supports our hypothesis that cocaine-induced ischemia triggers angiogenesis.

However, despite the increases in vessel density and in markers of angiogenesis, we showed that the baseline CBFv was significantly decreased in animals after chronic cocaine exposure. Small vessels () presented the most severe CBFv decreases from to after 2-week as well as from to after 4-week cocaine exposures. Interestingly, the vasculature images acquired with optical coherence angiography [OCA, Figs. 3(e) through 3(h)] showed that the increases in vessel densities after chronic cocaine were observed only in small vessels [, Figs. 3(i) and 3(j)], which suggests that these new small vessels might not be functionally viable. The increases in vessel density with cocaine were corroborated by the ex vivo results showing increases in FITC-Dextran and in VEGF in rats chronically exposed to cocaine.

The detected decrease in cortical CBFv might have contributed to the increase in small vessel density if it triggered hypoxia, as previously shown in animal models of stroke.23 Thus, to test if the reduction in CBF was associated with a reduction in oxygen content in tissue, we simultaneously evaluated the hemodynamic and metabolic variations induced by an acute cocaine challenge in chronic cocaine exposed rats using MW-LSI. We show that acute cocaine further decreased CBF and temporarily deprived the somatosensory cortex of oxygen content in animals that had chronic cocaine exposures. The magnitude and duration of the decreases in CBF and hypoxia were greater for the 4-week than the 2 week-cocaine exposed rats, indicative of a sensitization to the vasoconstricting effects of cocaine. Though MW-LSI provided only with relative measures through ODT, we were able to quantify absolute CBF measures and showed that chronically cocaine-exposed rats also had significant decreases in baseline CBF. Thus, this indicates that the decreases in CBF that occur with acute cocaine are occurring in animals that already show significant decreases in baseline CBF, in which acute cocaine would further exacerbate the deficits in CBF (and presumably also in ) resulting in ischemia. The large reductions in blood and oxygen supply to the cortex with chronic cocaine indicate that this might underlie the angiogenesis we observed in the animals exposed to chronic cocaine. However, the CBFv decreases observed in the chronically cocaine exposed rats both at baseline and during acute cocaine, along with the deteriorating oxygen supply to cortical tissue, despite the increases in vessel numbers observed in the chronically cocaine-exposed rats, indicates that cocaine-induced angiogenesis was insufficient to compensate for cerebrovascular dysfunction.

In this study, we recorded the MABP continuously during the imaging experiments in all animals. Basal MABP values in the different groups were in the normal blood pressure range (e.g., Groups 1A: ; Group 1B: ; and Group 1C: ). In Groups 4B and 4C, the MABP was slightly deceased (i.e., ) within to 8 min after acute cocaine (, i.v.). This hypotension was modest () and short lasting (), suggesting that cocaine-induced changes in CBF, , and HbR were unlikely to be driven by failure of cerebral autoregulation.24

Here, we postulate that angiogenesis reflects cocaine-induced ischemia. Indeed, in the current study, consistent with our prior work, we show that acute cocaine elicited cerebral microischemic changes and these were accentuated with repeated cocaine exposures.8 Endothelin-1 (ET-1), which is a potent vasoconstricting peptide produced by endothelial cells and implicated in cocaine’s vasconstricting effects, is a viable candidate.25 Cocaine releases ET-1 from endothelial cells and is associated with endothelial dysfunction following chronic cocaine exposures.26 In cocaine abusers, ET-1 levels in plasma are increased and decline after cocaine withdrawal.27–29 ET-1 is a strong angiogenic factor that exerts direct effects on endothelial cells via the receptor and indirectly through the receptor via release of VEGF, which is proangiogenic.30 VEGF and its receptors are critically involved in the regulation of pathological blood vessel growth in diseases associated with tissue hypoxia, such as solid tumor growth and ischemic diseases.23,31 There is also evidence that cocaine increases VEGF levels reported by ex vivo experiment in rodent’s C6 glial cells32 and evidence from clinical reports of increased VEGF in the pleural of cocaine abusers.33 This prominent angiogenic growth factor triggers endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and enhances vascular permeability attending the formation of nascent vessels.34–36 Thus, the persistent hypoxia from chronic cocaine exposure is likely to stimulate expression of ET-1 and VEGF resulting in angiogenesis.

Since acute cocaine elicited microischemic changes,8 it is possible that daily administration of cocaine could serve as an ischemic preconditioning (IPC). IPC also known as ischemic tolerance, refers to an intrinsic process whereby repeated short episodes of ischemia protect the cells and tissues against a subsequent ischemic insult. It was first identified in myocardium37 and subsequently found in brain.38 Several growth factors have been associated with the neuroprotective effect of IPC, including VEGF.39–41 In our current study, the expression of VEGF in the somatosensory cortex increased after chronic cocaine, which could promote local angiogenesis. Further studies are needed to determine if VEGF increases from chronic cocaine were due to IPC.

However, newly formed vessels, which consist of immature endothelium with few pericytes and little mature matrix, are consequently leaky.34,35 In this regard, it is possible that angiogenesis contributes to the blood-brain barrier dysfunction associated with chronic cocaine exposure.42–44 The immaturity of these newly formed vessels could also explain why despite the increases in vessel numbers, CBF remained significantly decreased in chronic cocaine-exposed animals.

Our findings have clinical implications for they indicate that chronic cocaine abusers are at increased risk of ischemic attacks particularly during cocaine intoxication and that these risks are likely to worsen with more protracted exposures. The increase in angiogenesis we observed in our study might be a mechanism by which the brain attempts to compensate for cocaine-induced hypoxia and with time might contribute to the process of recovery from cocaine-induced vascular deficits. Future studies are needed to assess the extent to which these new vessels might contribute to recovery of function and to assess the value of strategies to promote angiogenesis45,46 for recovery of cocaine-induced neurotoxic effects.

In summary, we provide evidence that chronic cocaine exposure triggers angiogenesis as a consequence of cocaine-induced transient ischemia that gets exacerbated with more protracted chronicity.

Acknowledgments

We especially thank K. Park for assisting with animal surgery and T. Ontiveros, Kevin Clare for assisting with VEGF image and for ex vitro imaging analysis. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) [Grant Nos. R21DA032228 (YP/CD), 1R01DA029718 (CD/YP), R01NS084817 (XH/CD)], the China Scholarship Council (QJZ), and NIH’s Intramural Program (NDV). C.D., Y.P., and N.D.V. designed the research; Q.J.Z., J.Y., and J.H.C. carried out the experiments and data analysis; W.Y.R. guided VEGF measurement and C.D., Y.P., and W.W. supervised Q.J.Z. Q.J.Z., C.D., Y.P., and N.D.V. wrote the manuscript and contributed significantly to discuss the results.

Biographies

Nora D. Volkow is director of NIDA at NIH. Her work was instrumental in demonstrating that drug addiction is a disease of the brain. She pioneered the use of brain imaging to investigate toxic and addictive effects of drugs, documenting for the first time reduced dopamine signaling in addiction that leads to impaired function of frontal brain regions involved with motivation and self-control. She has also made important contributions in obesity, ADHD, and aging.

Yingtian Pan is a professor of biomedical-engineering at SUNY Stony Brook, New York. He has been conducting research and development in advanced biophotonic imaging techniques, as well as their applications for biological tissues in vivo. His current research focuses on optical coherence tomography, laser-scanning endoscopy, and 3-D Doppler tomography. Preclinical and clinical applications in his lab include early diagnoses of bladder cancer, interstitial cystitis, tissue engineering growth, and high-resolution 3-D imaging of cerebral hemodynamics.

Congwu Du is currently a professor at BME, Stony Brook University, New York, USA. She was trained as a biomedical engineer at the University of Luebeck, Germany, and has spent 20 years in the application of optical imaging for characterization and detection of physiological processes in the brain and heart. Her current projects include the simultaneous detection of the cerebral blood flow/volume and oxygenation as well as intracellular calcium in vivo for drug addiction studies.

Biographies for the other authors are not available.

References

- 1.Sordo L., et al. , “Cocaine use and risk of stroke: a systematic review,” Drug Alcohol Depend. 142, 1–13 (2014). 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.06.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toossi S., et al. , “Neurovascular complications of cocaine use at a tertiary stroke center,” J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 19(4), 273–278 (2010). 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2009.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Treadwell S. D., Robinson T. G., “Cocaine use and stroke,” Postgrad. Med. J. 83(980), 389–394 (2007). 10.1136/pgmj.2006.055970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conway J. E., Tamargo R. J., “Cocaine use is an independent risk factor for cerebral vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage,” Stroke 32(10), 2338–2343 (2001). 10.1161/hs1001.097041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daras M., Tuchman A. J., Marks S., “Central nervous system infarction related to cocaine abuse,” Stroke 22(10), 1320–1325 (1991). 10.1161/01.STR.22.10.1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volkow N. D., et al. , “Cerebral blood flow in chronic cocaine users: a study with positron emission tomography,” Br. J. Psychiatry 152, 641–648 (1988). 10.1192/bjp.152.5.641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo F., et al. , “Differential responses in CBF and CBV to cocaine as measured by fMRI: implications for pharmacological MRI signals derived oxygen metabolism assessment,” J. Psychiatr. Res. 43(12), 1018–1024 (2009). 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ren H., et al. , “Cocaine-induced cortical microischemia in the rodent brain: clinical implications,” Mol. Psychiatry 17(10), 1017–1025 (2012). 10.1038/mp.2011.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayashi T., et al. , “Temporal profile of angiogenesis and expression of related genes in the brain after ischemia,” J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 23(2), 166–180 (2003). 10.1097/01.WCB.0000041283.53351.CB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krupinski J., et al. , “Role of angiogenesis in patients with cerebral ischemic stroke,” Stroke 25(9), 1794–1798 (1994). 10.1161/01.STR.25.9.1794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yancopoulos G. D., et al. , “Vascular-specific growth factors and blood vessel formation,” Nature 407(6801), 242–248 (2000). 10.1038/35025215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murukesh N., Dive C., Jayson G. C., “Biomarkers of angiogenesis and their role in the development of VEGF inhibitors,” Br. J. Cancer 102(1), 8–18 (2010). 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrell J. I., Basso J. C., Pereira M., “Both high and low doses of cocaine derail normal maternal caregiving– Lessons from the laboratory rat,” Front. Psychiatry 2, 30 (2011). 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du C., et al. , “Simultaneous detection of blood volume, oxygenation, and intracellular calcium changes during cerebral ischemia and reperfusion in vivo using diffuse reflectance and fluorescence,” J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 25(8), 1078–1092 (2005). 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouchard M. B., et al. , “Ultra-fast multispectral optical imaging of cortical oxygenation, blood flow, and intracellular calcium dynamics,” Opt. Express 17(18), 15670–15678 (2009). 10.1364/OE.17.015670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hillman E. M. C., et al. , “Depth-resolved optical imaging and microscopy of vascular compartment dynamics during somatosensory stimulation,” Neuroimage 35(1), 89–104 (2007). 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boas D. A., Dunn A. K., “Laser speckle contrast imaging in biomedical optics,” J. Biomed. Opt. 15(1), 011109 (2010). 10.1117/1.3285504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olabarriaga S. D., Breeuwer M., Niessen W. J., “Evaluation of Hessian-based filters to enhance the axis of coronary arteries in CT images,” Int. Congr. Ser. 1256, 1191–1196 (2003). 10.1016/S0531-5131(03)00307-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mariampillai A., et al. , “Optimized speckle variance OCT imaging of microvasculature,” Opt. Lett. 35(8), 1257–1259 (2010). 10.1364/OL.35.001257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Y., et al. , “Phase-resolved optical coherence tomography and optical Doppler tomography for imaging blood flow in human skin with fast scanning speed and high velocity sensitivity,” Opt. Lett. 25(2), 114–116 (2000). 10.1364/OL.25.000114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan Z., et al. , “Imaging separation of neuronal from vascular effects of cocaine on rat cortical brain in vivo,” Neuroimage 54(2), 1130–1139 (2011). 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.08.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otsu N., “A threshold selection method from gray-scale histograms,” IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 9, 62–66 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marti H. J. H., et al. , “Hypoxia-induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression precedes neovascularization after cerebral ischemia,” Am. J. Pathol. 156(3), 965–976 (2000). 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64964-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alessandro G., et al. , “A multimodality investigation of cerebral hemodynamics and autoregulation in pharmacological MRI,” Magn. Reson. Imaging 25(6), 826–833 (2007). 10.1016/j.mri.2007.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jośko J., “Cerebral angiogenesis and expression of VEGF after subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) in rats,” Brain Res. 981(1–2), 58–69 (2003). 10.1016/S0006-8993(03)02920-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pradhan L., et al. , “Molecular analysis of cocaine-induced endothelial dysfunction: role of endothelin-1 and nitric oxide,” Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 8(4), 161–171 (2008). 10.1007/s12012-008-9025-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sáez C. G., et al. , “Increased number of circulating endothelial cells and plasma markers of endothelial damage in chronic cocaine users,” Thrombosis Res. 128(4), e18–e23 (2011). 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tai H., et al. , “HIV infection and cocaine use induce endothelial damage and dysfunction in African Americans,” Int. J. Cardiol. 161(2), 83–87 (2012). 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.04.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai H., et al. , “Cocaine abstinence and reduced use associated with lowered marker of endothelial dysfunction in African Americans: a preliminary study,” J. Addict. Med. 9(4), 331–339 (2015). 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bagnato A., Spinella F., “Emerging role of endothelin-1 in tumor angiogenesis,” Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 14(1), 44–50 (2003). 10.1016/S1043-2760(02)00010-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marti H. H., Risau W., “Angiogenesis in ischemic disease,” Thrombosis Haemostasis 82(Suppl. 1), 44–52 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agharahimi M., et al. , “Cocaine induces HIF1 (Hypoxia Inducible Factor1) in rat C6 glial cells (LB619),” FASEB J. 28(Suppl. 1) (2014). 10.1096/fj.1530-6860 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strong D. H., et al. , “Eosinophilic “empyema” associated with crack cocaine use,” Thorax 58(9), 823–824 (2003). 10.1136/thorax.58.9.823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferrara N., Gerber H. P., LeCouter J., “The biology of VEGF and its receptors,” Nat. Med. 9(6), 669–676 (2003). 10.1038/nm0603-669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carmeliet P., “Angiogenesis in health and disease,” Nat. Med. 9(6), 653–660 (2003). 10.1038/nm0603-653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Z. G., et al. , “Correlation of VEGF and angiopoietin expression with disruption of blood-brain barrier and angiogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia,” J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 22(4), 379–392 (2002). 10.1097/00004647-200204000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murry C. E., Jennings R. B., Reimer K. A., “Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium,” Circulation 74(5), 1124–1136 (1986). 10.1161/01.CIR.74.5.1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kitagawa K., et al. , “‘Ischemic tolerance’ phenomenon detected in various brain regions,” Brain Res. 561(2), 203–211 (1991). 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91596-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawata H., et al. , “Ischemic preconditioning upregulates VEGF mRNA expression and neovascularization via nuclear translocation of PKC- in the rat ischemic myocardium,” Circ. Res. 88, 696–704 (2001). 10.1161/hh0701.088842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang H. L., et al. , “Effect of focal ischemic preconditioning on the expression of VEGF and survivin in ischemia hippocampus CA_1 region after focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in rats,” J. Apoplexy Nervous Dis. 32, 25–28 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu Y., et al. , “Neuroprotective effect of ischemic preconditioning in focal cerebral infarction: relationship with upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor,” Neural Regen. Res. 9(11), 1117–1121 (2014). 10.4103/1673-5374.135313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma H. S., et al. , Chapter 11 in Cocaine-Induced Breakdown of the Blood–Brain Barrier and Neurotoxicity, pp. 297–334, Academic Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts: (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yao H., et al. , “Cocaine hijacks σ1 receptor to initiate induction of activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule: implication for increased monocyte adhesion and migration in the CNS,” J. Neurosci. 31(16), 5942–5955 (2011). 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5618-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fiala M., et al. , “Cocaine increases human immunodeficiency virus type 1 neuroinvasion through remodeling brain microvascular endothelial cells,” J. Neurovirol. 11(3), 281–291 (2005). 10.1080/13550280590952835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greenberg D., “Cerebral angiogenesis: a realistic therapy for ischemic disease?,” in Cerebral Angiogenesis, Milner R., ed., pp. 21–24, Springer, New York: (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu J., et al. , “Vascular remodeling after ischemic stroke: mechanisms and therapeutic potentials,” Prog. Neurobiol. 115, 138–156 (2014). 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]