Highlights

-

•

HRV is the most common respiratory virus detected in hematologic malignancy patients.

-

•

51 distinct HRV types were identified in 110 patients in a one-year period.

-

•

Respiratory illness severity is not attributable to HRV species or type.

-

•

Bacterial co-infection is common in patients with HRV lower respiratory infection.

Keywords: Human rhinovirus, Viral pneumonia, Rhinovirus species, Immunocompromised hosts, Hematologic malignancy

Abstract

Background

Human rhinoviruses (HRVs) are common causes of upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) in hematologic malignancy (HM) patients. Predictors of lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) including the impact of HRV species and types are poorly understood.

Objectives

This study aims to describe the clinical and molecular epidemiology of HRV infections among HM patients.

Study design

From April 2012–March 2013, HRV-positive respiratory specimens from symptomatic HM patients were molecularly characterized by analysis of partial viral protein 1 (VP1) or VP4 gene sequence. HRV LRTI risk-factors and outcomes were analyzed using multivariable logistic regression.

Results

One hundred and ten HM patients presented with HRV URTI (n = 78) and HRV LRTI (n = 32). Hypoalbuminemia (OR 3.0; 95% CI, 1.0–9.2; p = 0.05) was independently associated with LRTI, but other clinical and laboratory markers of host immunity did not differ between patients with URTI versus LRTI. Detection of bacterial co-pathogens was common in LRTI cases (25%). Among 92 typeable respiratory specimens, there were 58 (64%) HRV-As, 12 (13%) HRV-Bs, and 21 (23%) HRV-Cs, and one Enterovirus 68. LRTI rates among HRV-A (29%), HRV-B (17%), and HRV-C (29%) were similar. HRV-A infections occurred year-round while HRV-B and HRV-C infections clustered in the late fall and winter.

Conclusions

HRVs are associated with LRTI in HM patients. Illness severity is not attributable to specific HRV species or types. The frequent detection of bacterial co-pathogens in HRV LRTIs further substantiates the hypothesis that HRVs predispose to bacterial superinfection of the lower airways, similar to that of other community-acquired respiratory viruses.

1. Background

Human rhinoviruses (HRVs) are traditionally considered “common cold” viruses, but they also play a substantial role in lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs) in children, elderly, and immunocompromised hosts. HRVs are classified taxonomically within the enterovirus (EV) group and subdivided into three species: A, B and C. Across the three species are more than 100 different serotypes. Since identification and designation of HRV-C species in 2006 [1], several studies have demonstrated increased rates of asthma exacerbations and LRTIs among children with HRV-C versus HRV-A or HRV-B infections [2], [3], [4]. However, more recent data have failed to observe an association between HRV species and illness severity [5], [6].

Patients with hematologic malignancy (HM) are at risk for complications of respiratory viral infections including prolonged illness, progression to LRTI, and bacterial superinfection. Understanding predictors and outcomes of HRV LRTI in HM patients including the effect of HRV species and type may aid in risk-stratification and empiric antibiotic use in patients with acute respiratory illness.

2. Objectives

This study aims to describe the clinical and molecular epidemiology of HRV infections among HM patients engaged in care at a New York City (NYC) hospital over a 12-month period.

3. Study design

3.1. Study population and data collection

At New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center (NYP/WCMC), all symptomatic HM patients are tested by molecular methods for respiratory viruses via nasopharyngeal (NP) swab or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). From April 2012 to March 2013, we reviewed the NYP/WCMC Clinical Microbiology Laboratory records daily to identify adult HM patients (age ≥ 18 years) testing positive for HRV. We excluded patients with HM that was in remission and who had not received chemotherapy in the previous year. All hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients were included if transplant occurred within the previous 12 months and/or chronic graft-versus-host disease was present. HRV-positive respiratory specimens were frozen and shipped to Wadsworth Center at the New York State Department of Health in Albany, NY for molecular characterization. Clinical data corresponding to each episode of HRV infection were abstracted from the electronic medical record.

3.2. Clinical microbiologic evaluation

During the study, the NYP/WCMC Clinical Microbiology Laboratory performed molecular testing for 17 respiratory viruses by multiplex real-time PCR (FilmArray Respiratory Panel [RP], BioFire Diagnostics, Inc., Salt Lake City, UT). All three HRV and four EV species are detected by the RP. Due to sequence homology, the RP assay does not reliably distinguish HRV from EV. For the purposes of this study, patients testing positive for the HRV/EV target on the RP assay were assumed to have HRV infection, which was confirmed by molecular testing at Wadsworth. In addition to the RP, the following diagnostic microbiology studies were performed on BAL fluid from immunocompromised patients at NYP/WCMC using standard procedures: Gram stain and bacterial culture, calcofluor white potassium hydroxide stain and fungal culture, acid-fast bacillus stain and mycobacterial culture, PCRs for Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, and Bordetella pertussis, Legionella direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) and culture, Pneumocystis jirovecii DFA, and Aspergillus galactomannan.

3.3. Virologic methods

An aliquot of 350 μl from each respiratory sample was extracted and eluted into 110 μl on the bioMérieux easyMAG (bioMérieux, Durham, NC). Reverse transcription was performed on 10 μl of RNA using the Quanta cDNA kit with random primers (Quanta, Gaithersburg, MD). The viral protein 1 (VP1) gene sequence of HRV was initially targeted using PCR primers designed at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Unpublished, kindly provided by Dr. Dean Erdman). If this assay failed to produce a band for sequencing, a further assay with primers targeting a different region of the VP1 gene was used [7]. If the VP1 gene assays failed, the VP4 gene sequence was amplified with primers described in Coiras et al. [8]. PCR products were visualized on a 1.5% TAE gel, and purified using Affimetrix ExoZapIt on samples displaying the appropriate size products (Affimetrix Santa Clara, CA). Sequencing was performed using the PCR primers from each of the assays.

Sequences from either the VP1 or VP4 genes were first BLAST analyzed to determine the HRV type. Sequences obtained using the CDC unpublished VP1 assay were aligned to representative VP1 sequences from species A, B and C imported from GenBank using the Clustal W multiple alignment program in MEGA 6.0 [9]. The maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA 6.0 with the neighbor-joining method for HRV-A and -B, and HRV-C. Since the sequences obtained using the Nix et al. assay (VP1) [7] and Coiras et al. assay (VP4) [8] target different regions, they were not used in the phylogenetic analysis.

3.4. Definitions

URTI was defined as having rhinorrhea, pharyngitis, or cough without clinical or radiographic evidence of lower respiratory involvement or hypoxia. LRTI was defined as having cough, dyspnea, sputum production, fever or hypoxia and new radiographic pulmonary infiltrates. LRTI was further sub-classified as (1) proven HRV LRTI when HRV was detected in BAL fluid and (2) possible HRV LRTI when bronchoscopy was not performed and HRV was detected in a NP swab. A separate URTI or LRTI episode required at least a two-week symptom-free period between episodes.

3.5. Statistical analysis

Given the conflicting literature about the effect of HRV species on illness severity, we sought statistical power to detect a difference in LRTI rates between HRV-A/HRV-B versus HRV-C if one truly existed. We hypothesized that HRV-C is associated with LRTI more often than HRV-A or HRV-B. Based on prevalence studies in other geographic locations, [3], [10], [11], [12], [13], we estimated a 1-to-1 ratio of HRV-A and HRV-B versus HRV-C infections. We predicted that 40% of HM patients would have HRV LRTI [14], [15], and we estimated an absolute difference of 30% in LRTI rates between HRV-A/-B and HRV-C infections [3], [4], [12], [15]. Therefore, a sample size of 41 subjects was needed in each group to detect a 30% difference in rates of LRTI with a 5% level of significance and 80% power.

Recognizing that HRV illness severity may also be driven by host, geographic, or temporal events, we evaluated other factors associated with HRV LRTI. We excluded patients co-infected with other respiratory pathogens from this analysis because patients with LRTI are likely to undergo more thorough microbiologic evaluation, a potential confounder. Univariable analysis was conducted using chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate, for categorical variables; a P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. Variables with a P-value ≤ 0.1 on univariable analysis were subsequently analyzed by multivariable logistic regression. Patients were followed for six months after the first HRV infection. Data were analyzed using STATA 12.1 (College Station, TX).

4. Results

4.1. Study population and respiratory co-pathogens

From April 2012 to March 2013, 110 HM patients had HRV-associated respiratory illness. HRV was the most common respiratory virus detected in symptomatic HM patients, followed by influenza H3N2 (N = 53), respiratory syncytial virus (N = 37), parainfluenza virus 3 (N = 30), coronavirus OC43 (N = 24), and human metapneumovirus (N = 18).

Patients were diagnosed with HRV during routine or acute outpatient visits (37%), or during inpatient admissions for chemotherapy or HSCT (16%), fever and/or respiratory symptoms (40%), or other acute reasons (6%). Forty-nine (45%) patients were HSCT recipients and 35 (32%) had acute leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome. Seventy-three (66%) patients had received chemotherapy, corticosteroids, or other immunosuppressive medications in the previous 30 days. Additional patient characteristics are outlined in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of hematologic malignancy patients with acute HRV infections.

| Variable | Total n = 110 (%) |

URTI n = 78 (%) |

Possible LRTI n = 19 (%) | Proven LRTI n = 13 (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 69 (63) | 47 (60) | 12 (63) | 10 (77) | 0.52 |

| Age > 50 years-old | 71 (65) | 46 (59) | 16 (84) | 9 (69) | 0.11 |

| Inpatient status | 69 (63) | 41 (53) | 17 (89) | 11 (85) | 0.002 |

| Underlying hematologic malignancy | 0.13 | ||||

| Acute leukemia or MDS | 35 (32) | 30 (38) | 2 (11) | 3 (23) | |

| Chronic leukemia | 21 (19) | 12 (15) | 5 (26) | 4 (31) | |

| Lymphoma, multiple myeloma or other | 54 (49) | 36 (46) | 12 (63) | 6 (46) | |

| HSCT recipient | 49 (45) | 37 (47) | 5 (26) | 7 (54) | 0.20 |

| Transplant type | 0.90 | ||||

| Autologous | 19 (17) | 15 (19) | 2 (11) | 2 (15) | |

| Allogeneic | 30 (27) | 22 (28) | 3 (16) | 5 (38) | |

| Donor relationa | 0.15 | ||||

| Matched-related | 14 (13) | 12 (15) | 1 (5) | 1 (8) | |

| Matched-unrelated | 9 (8) | 7 (9) | 1 (5) | 1 (8) | |

| Cord blood | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 1 (5) | 2 (15) | |

| Haploidentical and cord blood | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (8) | |

| Graft-versus-host diseaseb | 15 (14) | 11 (14) | 1 (5) | 3 (23) | 0.37 |

| Myeloablative conditioning | 27 (25) | 21 (27) | 2 (11) | 4 (31) | 0.15 |

| Chronic lung diseasec | 12 (11) | 8 (9) | 3 (16) | 1 (8) | 0.73 |

| Current tobacco use d | 11 (10) | 8 (11) | 3 (16) | 0 | 0.40 |

| Pneumonia within previous 30 days | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 2 (11) | 0 | 0.12 |

HSCT: hematopoietic stem cell transplant; LRTI: lower respiratory tract infection; MDS: myelodysplastic syndrome; URTI: upper respiratory tract infection.

Donor type was unknown for one patient who underwent HSCT.

Includes patients with acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) grades 2-4 and/or chronic GVHD.

Includes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma (n = 9), environmental hypersensitivity pneumonitis (n = 1), radiation pneumonitis (n = 1), desquamating interstitial pneumonitis (n = 1), bronchiectasis (n = 1) and GVHD of the lung (n = 1).

Defined as tobacco use within the previous 12 months.

At HRV diagnosis, 78 (71%) patients had a clinical diagnosis of URTI, 19 (17%) patients had possible HRV LRTI, and 13 (12%) patients had proven HRV LRTI. Among patients with HRV URTI, eight (10%) had viral co-infections. There were no cases of bacterial or fungal co-infection. Among patients with HRV LRTI, bacterial co-infection occurred in eight (25%), and viral and fungal co-infection occurred in two patients (6%) each (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Respiratory co-pathogens in patients with HRV lower respiratory tract infection (n = 12 patients).

| Bacterial (n = 8) | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniaea |

| Haemophilus influenzae(2 patients) | |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia(2 patients) | |

| Legionella pneumophila | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | |

| Viral (n = 2) | Influenza A H3N2 |

| Parainfluenza virus 3 | |

| Fungal (n = 2) | Pneumocystis jirovecii(2 patients) |

The two pathogens were detected in one patient.

4.2. Factors associated with HRV lower respiratory tract infection

Table 3 illustrates the clinical and laboratory variables that were associated with HRV LRTI in patients without respiratory co-pathogens. As there were no significant differences in putative risk factors between proven and possible HRV LRTI, these cases were combined for analysis. In univariable analysis, inpatient status and hypoalbuminemia were associated with HRV LRTI. In multivariable analysis, only hypoalbuminemia (OR 3.0; 95% CI, 1.0–9.2; P = 0.05) remained independently associated with HRV LRTI.

Table 3.

Factors associated with proven or possible HRV lower respiratory tract infections.a

| Variable | URTI n = 68 (%) | LRTI n = 20 (%)b | Univariable odds ratio (95% CI) |

Univariable P value | Multivariable odds ratio (95% CI) | Multivariable P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age > 50 years | 42 (62) | 15 (75) | 1.8 (0.6–5.7) | 0.28 | ||

| Inpatient status | 33 (49) | 17 (85) | 6.0 (1.6–22.4) | 0.008 | 3.9 (1.0–15.7) | 0.06 |

| Allogeneic HSCT recipient | 18 (26) | 3 (15) | 0.5 (0.1–1.9) | 0.3 | ||

| Acute leukemia or MDS or allogeneic HSCT recipient | 40 (59) | 15 (75) | 2.1 (0.7–6.4) | 0.2 | ||

| Chronic lung disease | 8 (13) | 3 (15) | 1.3 (0.3–5.5) | 0.7 | ||

| Current tobacco usec | 7 (10) | 2 (10) | 0.97 (0.2–5.1) | 0.97 | ||

| Chemotherapy within 30 daysd | 37 (54) | 12 (60) | 1.3 (0.5–3.5) | 0.66 | ||

| Corticosteroids within 30 dayse | 16 (23) | 4 (20) | 1.1 (0.3–3.7) | 0.93 | ||

| Any immunosuppressive therapy within 30 days | 43 (63) | 13 (65) | 1.1 (0.4–3.1) | 0.89 | ||

| Antibiotic use within 1 week | 15 (22) | 7 (35) | 1.9 (0.6–5.6) | 0.2 | ||

| Neutropenia (ANC ≤ 500 cells/μl) | 14 (21) | 4 (20) | 0.96 (0.3–3.3) | 0.95 | ||

| Lymphopenia (ALC ≤ 200 cells/μl) | 12 (18) | 7 (35) | 2.5 (0.8–7.6) | 0.1 | 1.5 (0.5–5.1) | 0.5 |

| Serum albumin ≤ 3.0 mg/dl | 20 (29) | 13 (65) | 4.5 (1.5–12.8) | 0.006 | 3.0 (1.0–9.2) | 0.05 |

| Renal insufficiency (GFR < 50 ml/min) | 13 (19) | 7 (35) | 2.3 (0.8–6.8) | 0.14 |

ALC: absolute lymphocyte count; ANC: absolute neutrophil count; CI: confidence interval; GFR: glomerular filtration rate; HSCT: hematopoietic stem cell transplant; LRTI: lower respiratory tract infection; MDS: myelodysplastic syndrome; URTI: upper respiratory tract infection.

Twenty patients with respiratory co-pathogens and two patients with HRV URTI and non-HRV pneumonia (bronchoscopy performed and HRV not detected in BAL fluid) were excluded from the analysis.

Includes n = 6 cases of proven HRV LRTI and n = 14 cases of possible HRV LRTI.

Defined as tobacco use within the previous 12 months.

Includes HSCT conditioning regimens.

Includes systemic corticosteroids for chemotherapy, treatment of graft-versus-host disease or other comorbid illnesses if ≥ 20mg prednisone per day.

4.3. Molecular epidemiology

BLAST analysis determined a genotype for 102 HRV-positive specimens from 92 patients, including ten specimens from eight patients with recurrent HRV infection during the follow-up period.

Fifty-eight (64%) patients had HRV-A, 12 (13%) had HRV-B, and 21 (23%) had HRV-C infections. One EV68 was identified in a patient with URTI. The signs, symptoms, and severity of respiratory illness were similar across HRV species (Table 4 ). In univariable analysis, there was no difference in the rate of LRTI among patients with HRV-C versus HRV-A/HRV-B infections. Among the 13 patients with proven HRV LRTI, HRV type was determined from 10 BAL fluid specimens, yielding nine distinct HRV-As and one HRV-C.

Table 4.

Clinical features of HRV infections according to HRV species.

| HRV-A | HRV-B | HRV-C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 58 (%) | n = 12 (%) | n = 21 (%) | |

| Fever | 30 (52) | 4 (33) | 8 (38) |

| Dyspnea | 20 (34) | 2 (17) | 6 (29) |

| Cough | 51 (88) | 8 (67) | 15 (71) |

| Sputum | 37 (64) | 6 (50) | 11 (52) |

| Rhinorrhea | 33 (57) | 6 (50) | 10 (48) |

| Respiratory co-pathogens | |||

| Bacterial | 4 (7) | 0 | 2 (10) |

| Viral | 2a(3) | 3 (25) | 2 (10) |

| Fungal | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| URTI | 41 (71) | 10 (83) | 15 (71) |

| LRTIb | 17 (29) | 2 (17) | 6 (29) |

| Possible LRTI | 8 (14) | 2 (17) | 5 (24) |

| Proven LRTI | 9 (16) | 0 | 1 (5) |

LRTI: lower respiratory tract infection; URTI: upper respiratory tract infection.

3 respiratory viruses detected in 2 patients.

LRTI rates among patient with HRV-C versus HRV-A and HRV-B: OR 1.1; 95% CI, 0.4 – 3.2; P = 0.9.

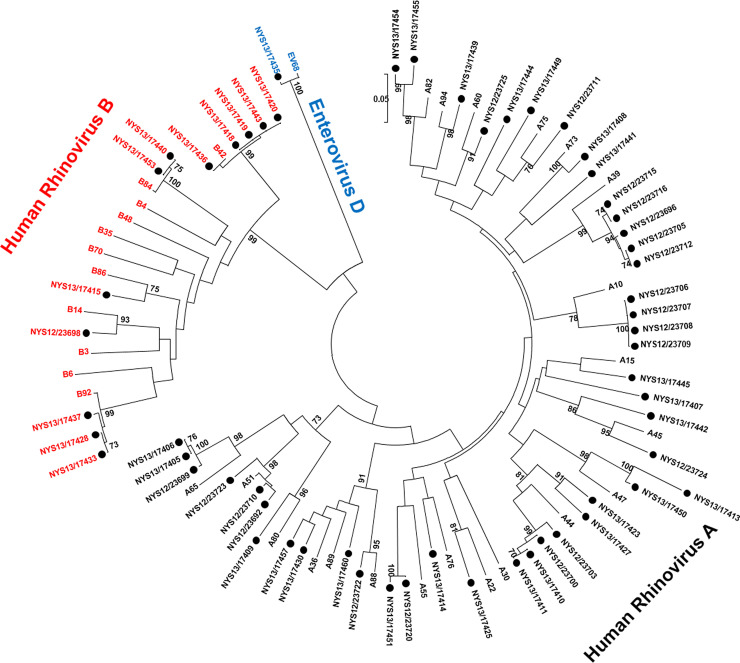

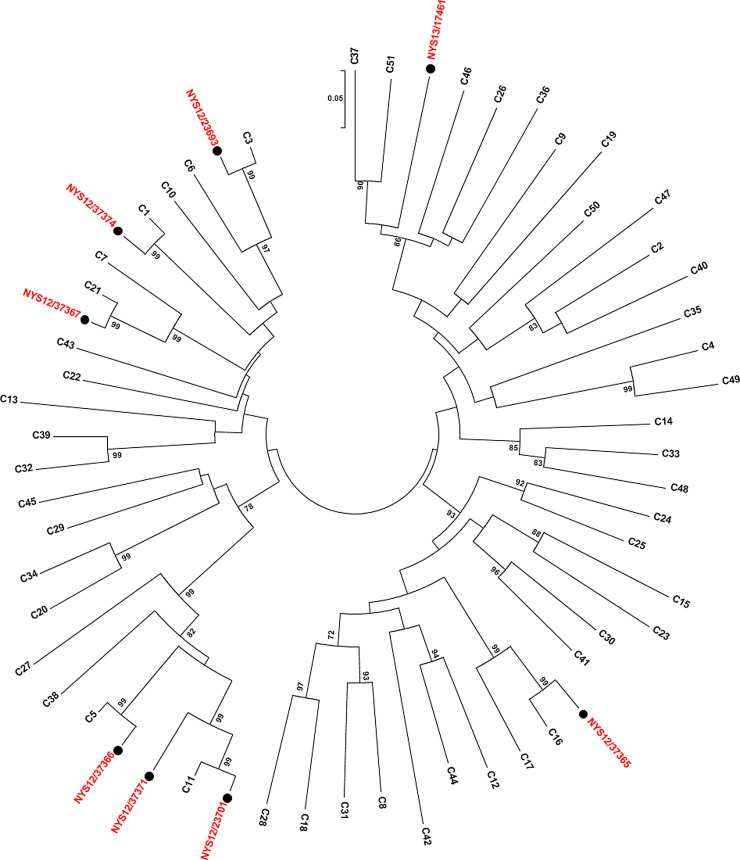

Fifty-one different HRV types were determined from VP4 or VP1 sequence analysis, including 34 HRV-As, five HRV-Bs, and 12 HRV-Cs. HRV-A1, HRV-A44, and HRV-B42 were the most common circulating types, each detected in five or more patients. Phylogenetic analysis of the VP1 gene region amplified by the CDC unpublished primers was performed on sequences from 58HRV-As and -Bs (Fig. 1 A) and eight HRV-Cs (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

(A) Phylogenetic analysis of VP1 gene of HRV-A and HRV-B reference strains and samples from this study. Phylogenetic tree constructed by neighbor-joining analysis of Maximum Likelihood method. Bootstrap values >70% shown (500 replicates). The analysis involved 91 nucleotide sequences and 108 positions. Reference strains are indicated by HRV-A or B-genotype and rooted to enterovirus D68; study samples are labeled with ●. VP: viral protein. (B) Phylogenetic analysis of VP1 gene of HRV-C reference strains and samples from this study. Phylogenetic tree constructed by neighbor-joining analysis of Maximum Likelihood method. Bootstrap values >70% shown (1000 replicates). The analysis involved 58 nucleotide sequences and 256 positions. Reference strains are indicated by HRV-C genotype and study samples are indicated by ●. VP: viral protein.

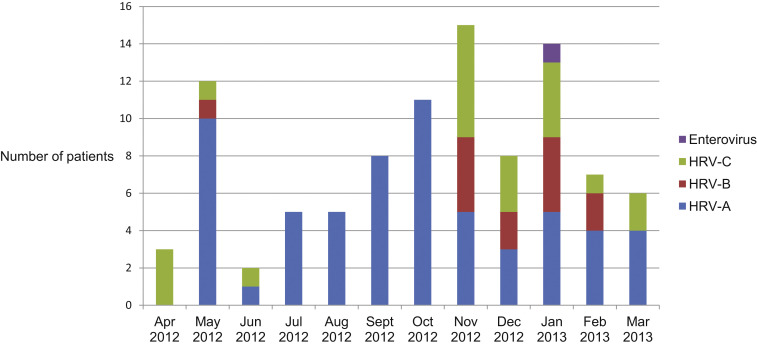

HRV infections peaked in the fall and winter (Fig. 2 ). HRV-A infections occurred year-round, peaking in the late spring and fall. HRV-B and HRV-C infections clustered in the late fall and winter months.

Fig. 2.

HRV species by month in patients with hematologic malignancy, n = 92.

4.4. Outcomes

Among the 76 patients with HRV URTI, 71 (93%) patients had symptomatic resolution of infection. Four (5%) patients developed signs and symptoms of LRTI within 30 days, including two cases of bronchiolitis. No respiratory co-pathogens were detected in sputum or BAL fluid (latter available in two cases). One patient was lost to follow-up. Overall 30-day survival was 95%.

Among the 32 patients with HRV LRTI, overall 30-day mortality was 25%, and 16% of patients died from respiratory causes. As compared to patients with possible HRV LRTI, patients with proven HRV LRTI were more likely to require oxygen supplementation, mechanical ventilation, and intensive care unit admission (data not shown). Overall 30-day mortality was similar between groups, but death due to respiratory causes was more common in patients with proven HRV LRTI (P = 0.006).

There were 12 episodes of recurrent HRV-associated respiratory illness among 10 patients during the six months following initial HRV infection. HRV type was determined in 10 recurrent illness episodes (median time between episodes 69 days [range 26–135 days]). The same molecular type for a given patient was detected in six episodes, and a different type was detected in four episodes.

5. Discussion

During a 12-month period, 110 HM patients were diagnosed with HRV infections at NYP/WCMC. To our knowledge, this is the largest study of the clinical and molecular epidemiology of HRVs among HM patients. The majority of patients had HRV URTI, but a substantial minority, 30%, had LRTI. As cases of mild HRV URTI may have been missed if clinicians did not pursue diagnostic testing, one cannot infer the absolute frequency of LRTI. Among the 76 patients with HRV URTI, 5% progressed to LRTI within 30 days. This suggests that symptomatic HRV LRTI is relatively uncommon among HM patients with HRV infection and that the observed rate of 30% in our study stems from the greater tendency to seek medical care when one is more ill. Nevertheless, in those patients with proven HRV LRTI, illness severity was considerable, with nearly 70% requiring ICU monitoring.

The relative roles of the virus and the host immune response in HRV pathogenicity is a subject of debate [16] and perhaps is even more complex among HM patients with innate and adaptive immune dysregulation due to underlying disease and chemotherapy. Hypoalbuminemia was independently associated with HRV LRTI and likely marks a catabolic state due to infection or possibly malnutrition. Other routine clinical and laboratory markers of immunosuppression were similar between HRV URTI and LRTI cases. Prospective measurement of cytokines and chemokines in nasal lavage and BAL fluids from HRV-infected HM patients is another means by which to understand HRV pathogenicity in immunocompromised hosts [17], [18].

Detection of bacterial co-pathogens occurred in 25% of patients with HRV LRTI. This observation supports in vitro data that HRV increases susceptibility to bacterial infection of the upper and lower respiratory epithelium [16] with pathogens including Staphylococcus aureus [19] and Streptococcus pneumoniae [20], [21], and impairs cytokine responses in HRV-activated alveolar macrophages [22]. Unfortunately, due to the low number of cases in our study and other studies of immunocompromised hosts [14], [23], [24], [25], we were unable to compare risk factors and outcomes in HM patients with HRV LRTI with and without co-pathogens.

The phylogenetic analysis illustrates the remarkable diversity of HRV types circulating in the Greater NYC area in a 12 month-period. Fifty-one HRV types and one EV were identified, suggesting community-acquisition of infection in this cohort of immunocompromised patients. Among those patients infected with the same HRV type, there were no readily identifiable risk factors for healthcare-associated transmission.

We observed the following LRTI rates across HRV species: HRV-A (29%), HRV-B (17%), and HRV-C (29%). Studies in other patient populations have failed to associate HRV species and LRTI when comparing HRV-A and HRV-C [6], [26], but HRV-B is often omitted from these analyses due to relatively low prevalence. Consistent with our observed trend that HRV-B is less frequently associated with LRTI, Nakagome et al. demonstrated that HRV-B has lower and slower replication in cultured sinus epithelial cells, as well as lower cytokine and chemokine production as compared to HRV-A and HRV-C [27].

Prolonged shedding of HRV is well-described in immunocompromised hosts [28]. While this study was not designed to assess microbiologic resolution of infection, among 10 episodes of clinically distinct HRV infection occurring after the initial episode, the same HRV type was identified in six episodes. We hypothesize that the recurrent symptoms may be due to viral reactivation as host immunity fluctuates. Conversely, the acquisition of new HRV types in four of 10 patients with recurrent URTI suggests a role for improved preventive measures including social distancing, respiratory masks, and hand hygiene.

This study has several limitations. First, microbiologic data were captured at a single time point so we could not confirm that HRV infection preceded, and therefore, predisposed to cases of bacterial co-infection. Second, among patients with different HMs, there is considerable heterogeneity in host immunity due to underlying disease and chemotherapy that may have confounded our ability to isolate host factors associated with HRV LRTI. It is possible that the frequency of HRV was underestimated in our cohort given that most PCR assays are not able to detect all known HRVs [29]. Twenty (16%) respiratory specimens were not molecularly typed, usually due to low viral load. Additionally, despite the use of highly degenerate primers, extensive sequence variability in the regions targeted make universal typing of HRV challenging [30], [31].

In conclusion, HRVs are associated with severe LRTI in HM patients; yet, the clinical spectrum of infection is not attributable to specific HRV species or types. Additional studies are needed to assess how viral and host characteristics influence HRV illness severity and transmission among immunocompromised patients, and thereby inform antiviral and vaccine efforts.

6. Competing interest

None.

7. Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health (grant T32 AI007613) and by the Clinical and Translational Science Center at Weill Cornell Medical College (grant UL1TR000457). Dr. Walsh is a scholar of the Sharp Family Foundation in Pediatric Infectious Diseases and a Scholar in Emerging Infectious Diseases of the Save Our Sick Kids Foundation.

8. Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Weill Cornell Medical College (1201012109) and the New York State Department of Health (12-030).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Lauren Mahoney technical assistance with the testing of the clinical samples and the Wadsworth Center Applied Genomics Technology Core for performing all the di-deoxy sequencing.

References

- 1.Lamson D., Renwick N., Kapoor V. MassTag polymerase-chain-reaction detection of respiratory pathogens, including a new rhinovirus genotype, that caused influenza-like illness in New York State during 2004–2005. J. Infect. Dis. 2006;194:1398–1402. doi: 10.1086/508551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bizzintino J., Lee W.-M., Laing I. Association between human rhinovirus C and severity of asthma in children. Eur. Respir. J. 2011;37:1037–1042. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00092410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linsuwanon P., Payungporn S., Samransamruajkit R. High prevalence of human rhinovirus C infection in Thai children with acute lower respiratory tract disease. J. Infect. 2009;59:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lauinger I.L., Bible J.M., Halligan E.P. Patient characteristics and severity of human rhinovirus infections in children. J. Clin. Virol. 2013;58:216–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwane M.K., Prill M.M., Lu X. Human rhinovirus species associated with hospitalizations for acute respiratory illness in young U.S. children. J. Infect. Dis. 2011;204:1702–1710. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiang Z., Gonzalez R., Xie Z. Human rhinovirus C infections mirror those of human rhinovirus A in children with community-acquired pneumonia. J. Clin. Virol. 2010;49:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nix W.A., Oberste M.S., Pallansch M.A. Sensitive, seminested PCR amplification of VP1 sequences for direct identification of all enterovirus serotypes from original clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44:2698–2704. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00542-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coiras M.T., Aguilar J.C., García M.L., Casas I., Pérez-Breña P. Simultaneous detection of fourteen respiratory viruses in clinical specimens by two multiplex reverse transcription nested-PCR assays. J. Med. Virol. 2004;72:484–495. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (GA) software version 4. 0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller E.K., Edwards K.M., Weinberg G.A. A novel group of rhinoviruses is associated with asthma hospitalizations. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009;123:98–104.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renwick N., Schweiger B., Kapoor V. A recently identified rhinovirus genotype is associated with severe respiratory-tract infection in children in Germany. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;196:1754–1760. doi: 10.1086/524312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau S.K.P., Yip C.C.Y., Lin A.W.C. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of human rhinovirus C in children and adults in Hong Kong reveals a possible distinct human rhinovirus C subgroup. J. Infect. Dis. 2009;200:1096–1103. doi: 10.1086/605697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calvo C., Casas I., García-García M.L. Role of rhinovirus C respiratory infections in sick and healthy children in Spain. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2010;29:717–720. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181d7a708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs S.E., Soave R., Shore T.B. Human rhinovirus infections of the lower respiratory tract in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2013;15:474–486. doi: 10.1111/tid.12111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferguson P.E., Gilroy N.M., Faux C.E. Human rhinovirus C in adult haematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients with respiratory illness. J. Clin. Virol. 2013;56:255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs S.E., Lamson D.M., St George K., Walsh T.J. Human rhinoviruses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2013;26:135–162. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00077-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gern J.E., Galagan D.M., Jarjour N.N., Dick E.C., Busse W.W. Detection of rhinovirus RNA in lower airway cells during experimentally induced infection. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1997;155:1159–1161. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.3.9117003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gentile D.A., Villalobos E., Angelini B., Skoner D. Cytokine levels during symptomatic viral upper respiratory tract infection. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91:362–367. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61683-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Passariello C., Schippa S., Conti C. Rhinoviruses promote internalisation of Staphylococcus aureus into non-fully permissive cultured pneumocytes. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:758–766. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J.H., Kwon H.J., Jang Y.J. Rhinovirus enhances various bacterial adhesions to nasal epithelial cells simultaneously. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:1406–1411. doi: 10.1002/lary.20498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishizuka S., Yamaya M., Suzuki T. Effects of rhinovirus infection on the adherence of Streptococcus pneumoniae to cultured human airway epithelial cells. J. Infect. Dis. 2003;188 doi: 10.1086/379833. 1928 -1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oliver B.G.G., Lim S., Wark P. Rhinovirus exposure impairs immune responses to bacterial products in human alveolar macrophages. Thorax. 2008;63:519–525. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.081752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ison M.G., Hayden F.G., Kaiser L., Corey L., Boeckh M. Rhinovirus infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients with pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003;36:1139–1143. doi: 10.1086/374340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gutman J.A., Peck A.J., Kuypers J., Boeckh M. Rhinovirus as a cause of fatal lower respiratory tract infection in adult stem cell transplantation patients: a report of two cases. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40:809–811. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaiser L., Aubert J.D., Pache J.C. Chronic rhinoviral infection in lung transplant recipients. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006;174:1392–1399. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-489OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin Y., Yuan X.H., Xie Z.P. Prevalence and clinical characterization of a newly identified human rhinovirus C species in children with acute respiratory tract infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47:2895–2900. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00745-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakagome K., Bochkov Y.A., Ashraf S. Effects of rhinovirus species on viral replication and cytokine production. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milano F., Campbell A.P., Guthrie K.A. Human rhinovirus and coronavirus detection among allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients. Blood. 2010;115:2088–2094. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-244152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faux C.E., Arden K.E., Lambert S.B. Usefulness of published PCR primers in detecting human rhinovirus infection. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011;17:296–298. doi: 10.3201/eid1702.101123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kistler A.L., Webster D.R., Rouskin S. Genome-wide diversity and selective pressure in the human rhinovirus. Virol. J. 2007:4. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simmonds P., McIntyre C., Savolainen-Kopra C., Tapparel C., Mackay I.M., Hovi T. Proposals for the classification of human rhinovirus species C into genotypically assigned types. J. Gen. Virol. 2010;91:2409–2419. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.023994-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]