Abstract

Although the real actual incidence of metallosis is unknown, it is described as a rare diagnosis with a 5% estimated incidence in the hip prosthetic replacements. The adoption of non-metallic articular prosthetic devices, made of polyethylene and ceramic, is the main reason to the diminishing number of reported cases. We present a case of metallosis with a clinical systemic presentation in a patient with a non-metallic hip prosthesis, which occurred due to a fracture of the acetabular liner component, leading to abnormal metal–metal contact. The metallic debris leads to a massive local and systemic release of cytokines. Revision is necessary whenever osteolysis and loosening of the prosthesis occur. Imaging evaluation, especially CT, has a central role in diagnosis and planning the surgical treatment.

Keywords: Metallosis, Hip prosthesis, Computed tomography

1. Introduction

Arthroplasty complications include many pathological entities. The most common are infection, peri-prosthetic fractures, dislocations, osteolysis and heterotopic ossification [1], [2].

Metallosis is a rare, potentially fatal complication after arthroplasty, but is generally associated with metal-on-metal prosthetic devices, but it has also been described in non-metallic prostheses [3]. It is defined as aseptic fibrosis, local necrosis, or loosening of a device secondary to metal corrosion and release of wear debris [4], [5]. It occurs due to metallic erosion and release of metallic debris products, which induce massive local cytokines liberation from inflammatory cells [3], [6]. The systemic absorption of metallic particles can cause several clinical presentations depending on the predominant affected system. We present a case of metallosis, with a hemolytic anemia presentation in a patient with a non-metallic prosthesis, which occurred due to facture of the non-metallic component, leading to metal-metal contact. Exuberant radiological findings are described and their importance in surgical treatment planning is highlighted.

2. Case report

A 55-year-old male presented to the emergence department complaining of right hip pain, malaise, intermittent fever and “red urine”. He also referred to weight loss. On physical examination he had jaundice and a right hip mass with fluctuation, but no significant inflammatory signs. Laboratorial findings revealed a hemolytic anemia, with elevated bilirubin and LDH and a positive Combs test, indicating an immunological mediated process. Hyperglycemia was also noted. The patient had a clinical history of total right hip arthroplasty four years previously with cementless modular ceramic–ceramic articulation prosthesis; the femoral and acetabular components were made of titanium alloy (titanium, aluminum and vanadium). A year later, he had a left total hip arthroplasty with a cementless prosthesis, with metal-polyethylene articulation and femoral stem and acetabular components made of titanium alloy. He had a recent (a year ago) history of surgical review of the right hip prosthesis due to a fracture of ceramic acetabular liner and its replacement with a polyethylene one.

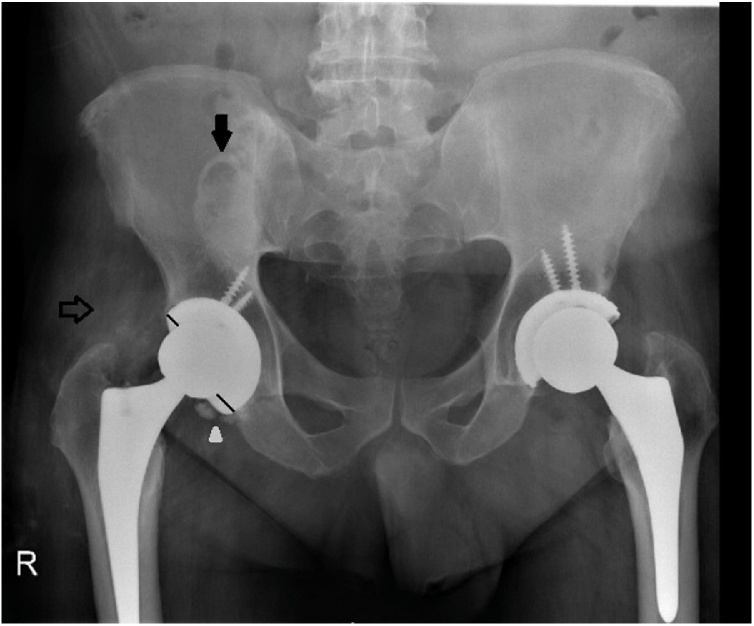

In the emergency department he performed a pelvic plain film that revealed a subtle misalignment, with eccentric location of the right femoral head, and two rounded high-density images: one denser image projected on the right iliac bone and the other above the femoral neck (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A 55-years-old man with metallosis. Plain film of pelvis, revealing two round high-density images, one denser projected on the right iliac bone and the other above the right femoral neck (arrows). High density fragments adjacent to the inferior acetabular border were also noted (arrowhead). There is also an eccentric position of the femoral head in the acetabular dome (non equal distance between the femoral head margin and the acetabular border – trace lines).

A non-imaging guide puncture to the periarticular right hip mass was performed in the emergency department with drainage of abundant black liquid (Fig. 2) indicating metallosis diagnosis. The black liquid color is due to the metallic components debris and basic chemistry is usually not necessary for the diagnosis.

Fig. 2.

A 55-years-old man with metallosis. Photograph of the black fluid drained after the right hip fluctuating mass puncture.

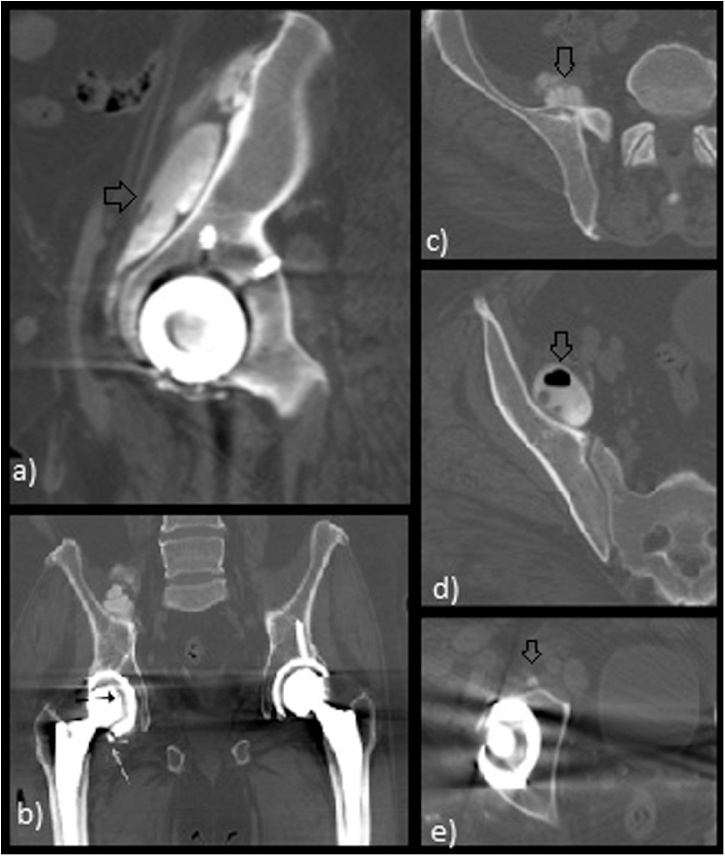

Hours after the procedure, the patient showed improvement of all clinical signs (fever, malaise) and analytical hyperglycemia values return to normal values. He was then discharged home, with referred appointment control in a week. Four days later, he returned to the emergency department, complaining of malaise. Analytical control in the emergency department reveled worsening of anemia and hyperglycemia levels. A CT scan was then performed. CT findings revealed a large elongated collection of high density content, extending from the articular space in to the pelvis along the right psoas muscle (Fig. 3), in relation with metallic components debris.

Fig. 3.

A 55-years-old man with metallosis. CT findings revealed a large elongated collection of high-density content, extending from the articular space into the pelvis along the right psoas muscle, in relation to metallic components debris.

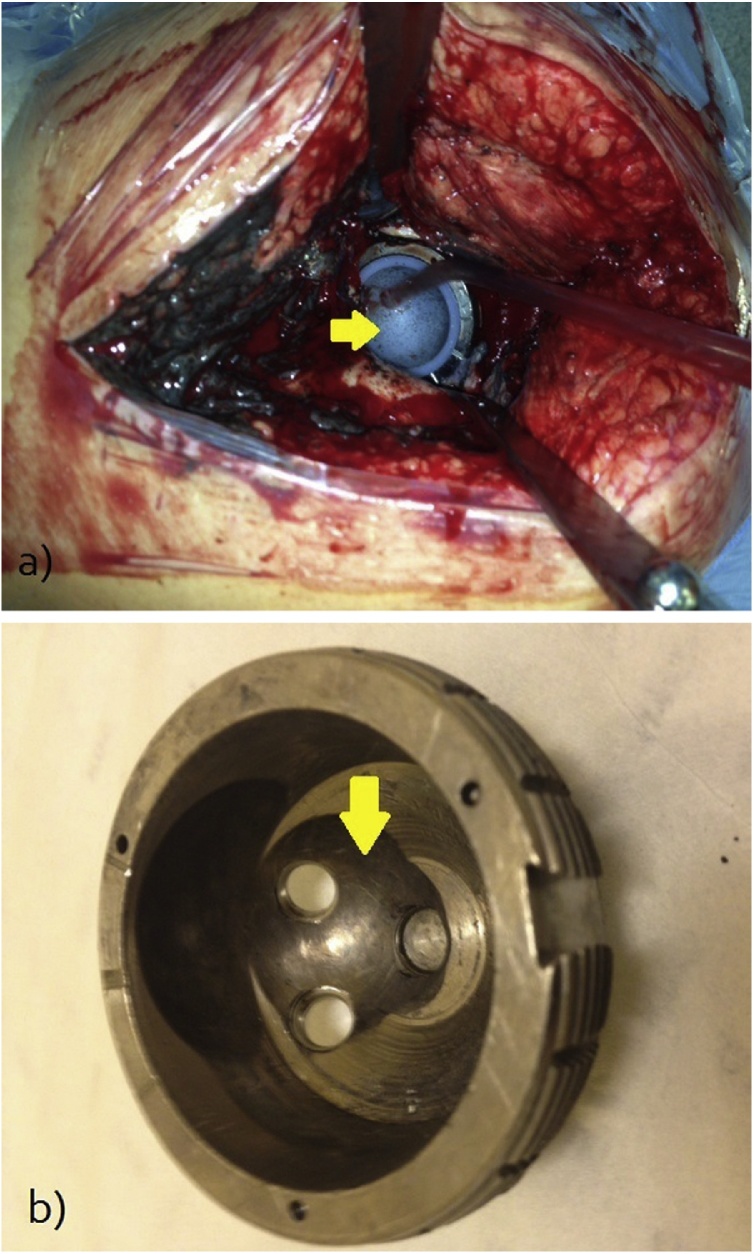

To avoid continuous absorption of the metallic particles, urgent surgical procedure to provide collection drainage was necessary. Due to the patient's systemic clinical impairment, a temporary pulsatile cleaning system was installed. An incision was made in the right lateral the hip and a draining cleaning system provided the liquid outlet. High-dose corticosteroid therapy and blood transfusion were performed, and after rising in red blood cells count, the patient underwent a second revision of the right hip prosthetic device. Intra-operatory findings confirmed the extensive metallosis; metal impregnation of the replaced polyethylene liner component, as well as wear of the acetabular metal dome. To allow direct access to the pelvic collection along the right psoas muscle, a trans-acetabular perforation was made and abundant black liquid was drained (Fig. 4). After surgery the patient made a good recovery, with improvement of all clinical parameters and analytical values.

Fig. 4.

(a and b) A 55-years-old man with metallosis. Intra-operatory pictures of the procedure showing extensive metallosis; metal impregnation of the replaced polyethylene liner component (a), as well as wear of the acetabular metal dome (b).

3. Discussion

Radiological evaluation of a prosthetic implant should always be preceded by the knowledge of the type of implant. Each of them has a different imaging appearance and different associated risk complications. Complications manifesting as dense areas are rare and have a narrow differential diagnosis. Most frequent are heterotopic ossification and cement extravasation [1]. Cement extravasation was excluded in this case, because this was a cementless prosthesis.

Heterotopic ossification occurs when primitive mesenchymal cells in the surrounding soft tissues are transformed into osteoblastic cells and form mature bone. It typically occurs around the femoral neck and adjacent to the greater trochanter in 15–50% of patients. Many patients with low-grade heterotopic ossification are asymptomatic. Articular stiffness and pain are the main clinical complaints [1], [2].

Metallosis was first described in association with setting of the fixation of fractures with metal implants [7]. The adoption of articular components made of other materials such as polyethylene or ceramic has dramatically reduced its incidence in patients with articular prostheses, and nowadays it is a rare complication (5.3% of total hip arthroplasty complications) [1], [2], [8]. Although less frequent, even with polyethylene or ceramic articular components metallosis can occur if there is abnormal metal-on-metal contact due to wear or fracture of the articular component [6], [9]. Wear-through and dislodgement of the acetabular liner may be influenced by several factors, including use of thin polyethylene insert and the method of sterilization treatment of polyethylene liners [9]. Chronic abrasion between the metal components induces the release and infiltration of metallic particles, activating a local chronic inflammatory reaction and systemic absorption of metallic particles. This gives rise to a variable range of local and systemic alterations, depending on metal type, particle size, volume and time of exposure [9].

Patients may be asymptomatic with isolated imaging findings suggesting wear-through, fracture or dislodgment of the liner; an eccentric femoral head will be evident in all cases [9]. Some patients may refer an audible crepitus or squeaking on weight bearing. Pain, pseudotumoral mass formation and osteolysis are the commonest local changes [2]. The spread of metallosis or infection along the psoas muscle has already been described and it may be associated to either direct spread through the bursa, or acetabular fissures arising at the time of surgery which allowed the initial process to extend [10], [11].

The systemic effects are mainly caused by an immunologic response due to metal sensitivity. High levels of chromium and cobalt components are related to headache and cognitive changes, hematological abnormalities and neuromuscular changes [12]. Titanium alloy components absorption effects (titanium, aluminum and vanadium) are less known, but have been recently described in the literature [3]. Although titanium has been regarded as inert and biocompatible, titanium particles and ions can also induce the release of potentially osteolytic cytokines and cause necrosis, fibrosis and other structural changes in regional lymph nodes, liver and spleen [5]. Hemolytic anemia process will probably be also related to an immunological process, induced by metal sensitivity, but the real mechanism has not yet been described.

Imaging findings in plain films and CT studies include misalignment of the femoral head in the acetabular roof, and loss of joint space suggesting wear or fracture of the prosthesis liner; the “cloud sign” – amorphous densities in the peri-prosthetic tissues and the “bubble sign” – hyper-dense rounded images with a higher contour (metal deposits) [1], [8], [9]. Subtle changes may be difficult to detect on radiographs, but all of the described signs could be found in the radiographic study of the presented case (Fig. 1).

Metallosis diagnosis may be made at joint aspiration only, when dense black fluid is obtained, so fluid analysis is not essential [9].

Treatment consists of surgical revision with replacement of the prosthesis components, complete surgical debridement of osteolytic lesions and bone grafting with allograft chips. Complete removal of all metal debris is difficult and may result in extensive tissue damage [9]. In the reported case, drainage of the large pelvic collection was also required. CT imaging allowed not only the diagnosis of the initially missed pelvic collection, but also contributed to the correct surgical planning. A successful collection drainage through a transacetabular approach during the prosthesis revision was performed.

In summary, metallosis occurs not only in metal-on-metal prostheses but also in non-metallic prostheses, and it has a very wide and nonspecific clinical presentation. Regular imaging control should be performed and metallosis should be suspected in a patient with hyperdense periarticular images, especially if associated with an eccentric femoral head sign. Complementary imaging evaluation is also essential to a correct surgical planning, allowing most of the metal debris material removal, crucial to a rapid and complete patient recovery.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Roth T.D., Maertz N., Parr J., Buckwalter K., Choplin R. CT of the hip prosthesis: appearance of components, fixation, and complications. Radiographics. 2012;32:1089–1107. doi: 10.1148/rg.324115183. PMID: 22786996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang E.Y., McAnally J.L., Van Horne J.R., Statum S., Wolfso T., Gams A. Metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: do symptoms correlate with MR imaging findings? Radiology. 2012;265(December (3)):848–857. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120852. PMID: 23047842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pesce V., Maccagnano G., Vicenti G., Notarnicola A., Lovreglio P., Soleo L. First case report of vanadium metallosis after ceramic-on-ceramic total hip arthroplasty. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2013;27(October–December (4)):1063–1068. PMID: 24382188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell P., Chun G., Kossovsky N., Amstutz H.C. Proceedings of 38th Annual Meeting Orthopaedic Research Society. 1992. Histological analysis of tissues suggest that ‘metallosis’ may really be ‘plasticosis’; p. 393. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miloŝev L., Antoliĉ V., Minoviĉ A., Cör A., Herman S., Pavlovcic V.P. Campbell extensive metallosis and necrosis in failed prostheses with cemented titanium-alloy stems and ceramic heads. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(April (3)):352–357. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.82b3.9989. PMID: 10813168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willis-Owen CA1, Keene G.C., Oakeshott R.D. Early metallosis-related failure after total knee replacement: a report of 15 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(February (2)):205–209. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B2.25150. PMID: 21282760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von Lüdinghausen M., Meister P., Probst J. Metallosis after osteosynthesis. Pathol Eur. 1970;5(3):307–314. PMID: 5477026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keogh C., Munk P., Gee R., Chan L., Marchinkow L. Imaging of the painful hip arthroplasty. AJR. 2003;180:115–120. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.1.1800115. PMID: 12490489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cipriano CA1, Issack P.S., Beksac B., Della Valle A.G., Sculco T.P., Salvati E.A. Metallosis after metal-on-polyethylene total hip arthroplasty. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2008;37(February (2)):E18–E25. PMID: 18401490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dauchy F., Dupon M., Dutroc H., Barbeyrac B., Lawson-Ayayi S. Association between psoas abscess and prosthetic hip infection: a case–control study. Acta Orthop. 2009;80(2):198–200. doi: 10.3109/17453670902947424. PMID: 19404803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rymaruk S., Razak A., McGivney R. Metallosis, psoas abscess and infected hip prosthesis in a patient with bilateral metal on metal total hip replacement. J Surg Case Rep. 2012;2012(May (5)):11. doi: 10.1093/jscr/2012.5.11. PMID: 24960139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell P., Shimmin A., Walter L., Solomon M. Metal sensitivity as a cause of groin pain in metal-on-metal hip resurfacing. Arthroplast J. 2008;23(October (7)):1080–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.09.024. PMID: 18534479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]