Abstract

There is a clinical need to test new schemes of benznidazole administration that are expected to be at least as effective as the current therapeutic scheme but safer. This study assessed a new scheme of benznidazole administration in chronic Chagas disease patients. A pilot study with intermittent doses of benznidazole at 5 mg/kg/day in two daily doses every 5 days for a total of 60 days was designed. The main criterion of response was the comparison of quantitative PCR (qPCR) findings prior to and 1 week after the end of treatment. The safety profile was assessed by the rate of suspensions and severity of adverse effects. Twenty patients were analyzed for safety, while qPCR was tested for 17 of them. The average age was 43 ± 7.9 years; 55% were female. Sixty-five percent of treated subjects showed detectable qPCR results prior to treatment of 1.45 (0.63 to 2.81) and 2.1 (1.18 to 2.78) parasitic equivalents per milliliter of blood (par.eq/ml) for kinetoplastic DNA (kDNA) qPCR and nuclear repetitive sequence satellite DNA (SatDNA) qPCR, respectively. One patient showed detectable PCR at the end of treatment (1/17), corresponding to 6% treatment failure, compared with 11/17 (65%) patients pretreatment (P = 0.01). Adverse effects were present in 10/20 (50%) patients, but in only one case was treatment suspended. Eight patients showed mild adverse effects, whereas moderate reactions with increased liver enzymes were observed in two patients. The main accomplishment of this pilot study is the promising low rate of treatment suspension. Intermittent administration of benznidazole emerges a new potential therapeutic scheme, the efficacy of which should be confirmed by long-term assessment posttreatment.

INTRODUCTION

Benznidazole was developed by Roche, and after its trypanocidal effect was demonstrated, it was marketed in 1973 (1). The original studies determined a therapeutic dose of 5 mg/kg of body weight/day for adult subjects with chronic Trypanosoma cruzi infection, with no differences in effectiveness between 30 and 60 consecutive days of benznidazole administration, as measured by serial xenodiagnoses (2).

Since the beginning of benznidazole use, several adverse effects were noted mainly in adults (3). Some of them are probably not dependent on the cumulative dose, as would be the case of delayed-hypersensitivity dermatitis, which usually occurs in the first 15 days of administration and whose mechanisms are not well known. Other adverse effects, such as peripheral neuropathy and blood dyscrasias, appear to be related empirically to the cumulative dose of benznidazole (4).

Several observational studies with benznidazole administered at 5 mg/kg/day for 30 days in adult patients with Chagas disease have shown a reduction in the progression of heart disease and a conversion to negative findings by conventional serological tests up to 30% of treated patients after a long-term follow-up (4–9). On the other hand, two randomized studies with benznidazole administered for 60 days in T. cruzi-infected children up to 14 years of age demonstrated an antiparasitic efficacy (10, 11) and led to extrapolation of this duration of treatment to adult patients, as stated in most international guidelines.

However, nowadays both the dose and duration of administration are under discussion in order to improve the safety of benznidazole administration (3, 12). A recent clinical study showed, surprisingly, that 20% of patients with chronic Chagas disease, who received benznidazole for a median of 10 days due to the appearance of severe side effects, could achieve parasitological cure (13), reinforcing that new schemes of benznidazole administration must be tested. An experimental study in a mouse model of chronic T. cruzi infection has recently shown that intermittent administration of benznidazole (100 mg/kg/day in doses over the course of 60 days) was as effective as the standard treatment with 100 mg/kg/day for 40 days, which cured 100% of treated animals (14).

Herein, we report a pilot short-term follow-up study to assess the safety and the antiparasitic efficacy of a new scheme of intermittent administration of benznidazole in chronically T. cruzi-infected patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Treatment schedule.

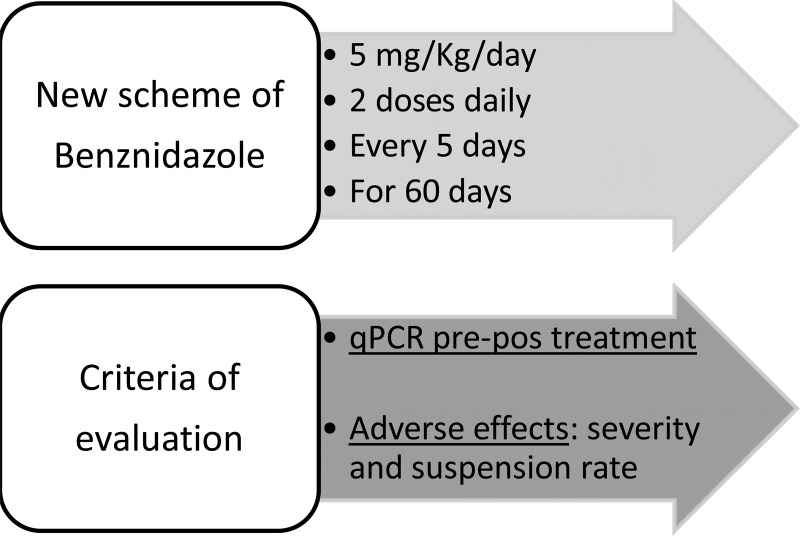

A pilot study for evaluation of the antiparasitic action and safety of a new scheme of treatment with benznidazole administered in intermittent doses of 5 mg/kg/day, divided into two daily doses every 5 days, for a total of 60 days (i.e., 12 days of intermittent treatment) was designed (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

New treatment scheme and criteria of evaluation of intermittent benznidazole administration in patients with chronic Chagas disease. pre-pos, pretreatment versus posttreatment.

The research hypotheses was that the intermittent administration of benznidazole might lead to a low rate of treatment failure (5 to 10%), as assessed by quantitative PCR (qPCR), but with a reduction in the number of treatment suspensions, as well as a reduction in the severity of adverse effects observed with the standard treatment scheme.

Study population.

Twenty adult patients with confirmed chronic Chagas disease (i.e., positive findings on at least 2 serological tests using different antigens and based on different methodological principles performed in parallel) between 18 and 60 years of age were included. All subjects recruited in the study signed an informed consent form. Patients with a history of or laboratory findings compatible with liver or kidney disease, blood dyscrasias, or concomitant systemic illnesses were excluded from the study. Other exclusion criteria were previous etiological treatment, pregnancy or presumption of failure in contraception during the treatment period, and a location of residence that could interfere with patient participation in the study.

Assessment criteria of antiparasitic response.

The primary endpoint for a parasiticidal effect of treatment was the rate of positive detection of T. cruzi by qPCR in blood collected 1 week after the end of treatment, evaluated blindly by two independent laboratories.

Five milliliters of whole blood was mixed with 5 ml of buffer containing equal volumes of 6 M guanidine hydrochloride (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 0.2 M EDTA (pH 8.00), kept at room temperature for 1 week and then at 4°C until use. Blood samples were centralized, codified for distribution in aliquots, and sent to the two research centers that performed PCR detection without knowledge of clinical data or sampling time. After 48 to 72 h at room temperature, blood samples were boiled with GE buffer for 15 min and stored at 4°C for DNA extraction and subsequent analysis by two types of qPCR: kinetoplastid DNA (kDNA) qPCR and satellite DNA (SatDNA) qPCR. Each participating laboratory processed the samples in duplicates by both qPCR techniques. A qPCR was considered positive if T cruzi DNA was detectable in at least one assay (with 4 assays in each participating laboratory).

Real-time qPCR assays were based on TaqMan technology: one qPCR directed to the conservative region of the DNA minicircle kinetoplastid (kDNA) and the other to the nuclear repetitive sequence satellite DNA (SatDNA). These techniques were carried out according to the international workshop sponsored by the Special Program PAHO/WHO Research and Training in Tropical Diseases for validation and standardization of laboratory quantitative PCR (15). The limits of quantification were 0.90 parasitic equivalent in 1 ml of blood (par.eq/ml) and 1.53 par.eq/ml for the kDNA qPCR and SatDNA qPCR, respectively.

Safety profile.

A detailed search of potential adverse effects was performed by clinical monitoring with an interview, physical examination, and laboratory testing. Follow-up visits were performed once a week, with unplanned consultations at the onset of adverse effects. Laboratory testing that included blood count, liver function, renal function, and lipid levels was performed prior to treatment and at day 7 after completion of treatment.

The primary endpoint of safety was the percentage of definitive suspension of prescribed treatment—around 20% with a conventional treatment schedule with benznidazole in adult patients (3). Another criterion for evaluating the safety profile was the number and severity of adverse effects established as mild, moderate, severe, requiring hospitalization, or life-threatening (16).

In the case of adverse effects that led to the temporary or permanent suspension of treatment, new laboratory testing was performed.

Methodology and data collection.

Patients were included in two health centers with extensive experience in the etiological treatment of chronic Chagas disease. Eleven patients were treated at the Hospital Interzonal General de Agudos Eva Perón, San Martin, Buenos Aires, Argentina, and 9 patients were treated at the National Institute of Parasitology Dr. Mario Fatala Chaben, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

For those patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria, medical history, physical examination and electrocardiogram (ECG) at rest were recorded. Subsequently, participation in the study of intermittent treatment with benznidazole was proposed. An informative text was handed out, and patients were asked freely and voluntarily for their signature on the informed consent form.

Scheduled visits were made at admission and thereafter weekly up to completion of the 60-day treatment period. For all patients, a form listing adverse effects designed for this purpose was completed. In case of appearance of adverse effects, patients were encouraged to immediately attend the corresponding health center, and a contact phone number was also provided for guidance.

To facilitate compliance and homogenize the indications in both health centers participating in the study, a low-fat and hypoallergenic diet was advised for all patients in writing.

Ethical considerations.

There is a clear clinical need to test new schemes of benznidazole treatment, at least with the same level of efficacy as but safer than conventional treatment. The recommendation to treat chronic Chagas disease patients has been accompanied by resistance to the practical implementation and dissemination at the different levels of the health care system, mainly due to the fear of side effects.

In this pilot study, the safety and efficacy of a new scheme of intermittent administration of benznidazole were explored in a short-term follow-up. From the ethical point of view, if the results were not as expected regarding the main criteria for a positive response to treatment, a conventional treatment schedule for all patients included in the study was offered.

The project was approved by the Committee for Research and Bioethics of the Hospital Eva Peron. The latter is enrolled in the Provincial Registry for Ethics Committees accredited by the Central Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health, Buenos Aires, Argentina, dated 17 September 2010 under no. 18/2010, p. 54 of the Minutes Book No. 1.

Statistical analysis.

Data from descriptive statistics, such as the proportions of the total and percentages, mean and standard deviation, or median and interquartile range are presented, as appropriate. The Spearman correlation test was used to compare PCR data between both laboratories. To compare PCR findings prior to and after treatment, a McNemar test was applied.

RESULTS

Characteristics of study patients.

Twenty patients who completed the safety assessment were included for the analysis. In 17 of the 20 patients, the parasite load in peripheral blood was determined by qPCR prior to and after completion of the treatment schedule. Blood samples at the end of treatment were not available for 3 patients due to traveling in two cases and study discontinuity because of refusal to undergo a blood extraction in the remaining case.

The average age of patients was 43 ± 7.9 years; 11 were female (55%) and 9 male (45%). Patients were grouped according to Kuschnir classification (17): 75% (15/20) of the patients were from group 0, 20% (4/20) from group I, and 5% (1/20) from group II. Patients with heart failure (group III of the Kuschnir classification) were not included.

Ninety percent (18/20) of patients presented three reactive conventional serological tests (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA], indirect hemagglutination, and immunofluorescence), while the remaining 2 patients only had 2 positive serological tests (10%). ECG abnormalities suggestive of chronic Chagas heart disease were detected in 25% (5/20) of participants, including left anterior fascicular block plus ventricular premature contractions of Lown grade IVa in one patient, ventricular premature contractions of Lown grade IVa in one patient, left anterior fascicular block plus ventricular premature contractions of Lown grade II in one patient, and complete right bundle branch block in two patients.

Monitoring of antiparasitic response.

Sixty-five percent of patients who completed the PCR assays (11/17) had detectable T. cruzi DNA prior to treatment, six of them with quantifiable values of 2.87 (1.56 to 6.60) and 3.07 (1.88 to 8.47) par.eq/ml for the kDNA qPCR and SatDNA qPCR, respectively, whereas five patients showed detectable nonquantifiable samples. Two of the three patients without qPCR measurement after treatment had detectable T. cruzi DNA before treatment.

Only one patient showed detectable parasitemia at the end of treatment (1/17; P = 0.01), corresponding to 6% treatment failure at the time of evaluation. This patient showed a detectable nonquantifiable qPCR for both techniques.

The correlations of measurements of parasite load between both participating laboratories were R = 0.86 and P < 0.001 for kDNA qPCR and R = 0.94 and P < 0.001 for SatDNA qPCR.

Safety profile.

Nineteen of 20 (95%) patients were able to complete the scheme of intermittent treatment under evaluation. The only case of treatment suspension showed mild symptoms of digestive intolerance, with an increase in liver enzymes of more than 3-fold the basal values.

Adverse effects occurred in 10/20 patients (50%), distributed as dermatitis in 7/20 (35%), gastrointestinal intolerance in 5/20 (25%), increased liver enzymes in 4/20 (20%), loss of appetite in 1/20 (5%), and insomnia in 1/20 (5%). Peripheral neuritis and headache were not observed in any patient.

The degree of adverse effects was mild in 8/10 (80%) patients (dermatitis in 6 patients and digestive intolerance in 2 patients) and moderate in 2/10 (20%) patients (both cases with an increase of liver enzymes of >3-fold the basal values). No serious adverse effects or patient hospitalization were reported. The presence of digestive intolerance symptoms was associated with an increase in liver enzymes in 4/5 cases (80%).

The two cases with increased levels of liver enzymes of >3-fold the basal value were detected by 30 and 60 days of treatment, respectively, associated with mild symptoms of digestive intolerance. Increased values returned to normal following 45 and 10 days after diagnosis, respectively. In the former patient, treatment was suspended, whereas in the other subject, abnormal values were detected after completion of treatment with benznidazole.

Table 1 shows a summary of the characteristics and the main findings of intermittent treatment in the 17 patients who completed the qPCR assays.

TABLE 1.

Summary of main findings of safety and response to intermittent administration of benznidazole in 17 chronic Chagas disease patients

| Patient ID | Age (yr) | Sex | Abnormal ECG | Kuschnir group | Result (par.eq/ml) bya: |

Adverse effects (degree) | Dermatitis | Digestive intolerance | Increased liver enzymes | Suspension | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal qPCR |

Final qPCR |

||||||||||||

| kDNA | SatDNA | kDNA | SatDNA | ||||||||||

| 1 | 53 | F | No | 0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | Yes (mild) | Yes | No | No | No |

| 2 | 42 | F | Yes | II | ND | ND | ND | ND | No | No | No | No | No |

| 3 | 45 | F | Yes | I | ND | ND | ND | ND | Yes (mild) | Yes | No | No | No |

| 4 | 47 | M | No | 0 | <0.90* | <1.53* | ND | ND | No | No | No | No | No |

| 5 | 57 | M | Yes | I | ND | ND | <0.90* | <1.53* | Yes (mild) | Yes | No | No | No |

| 6 | 41 | F | No | 0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | No | No | No | No | No |

| 7 | 55 | M | Yes | I | 3.15 | 2.16 | ND | ND | Yes (moderate) | No | Yes | Yes (>3-fold) | No |

| 8 | 46 | F | No | 0 | 1.30 | 1.60 | ND | ND | No | No | No | No | No |

| 9 | 49 | F | No | 0 | <0.90* | <1.53* | ND | ND | Yes (moderate) | Yes | Yes | Yes (>3-fold) | Yes |

| 10 | 49 | M | No | 0 | 1.83 | <1.53* | ND | ND | Yes (mild) | No | Yes | No | No |

| 11 | 46 | M | No | 0 | 10.06 | 13.36 | ND | ND | Yes (mild) | Yes | No | No | No |

| 12 | 28 | M | No | 0 | <0.90* | 3.07 | ND | ND | No | No | No | No | No |

| 13 | 40 | F | No | 0 | <0.90* | <1.53* | ND | ND | Yes (mild) | No | Yes | Yes (<3-fold) | No |

| 14 | 35 | M | No | 0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | Yes (mild) | Yes | Yes | Yes (<3-fold) | No |

| 15 | 45 | M | No | 0 | <0.90* | <1.53* | ND | ND | Yes (mild) | Yes | No | No | No |

| 16 | 33 | F | No | 0 | <0.90* | <1.53* | ND | ND | No | No | No | No | No |

| 17 | 38 | M | No | 0 | 2.87 | 3.59 | ND | ND | No | No | No | No | No |

The maximal value detectable among replicates is shown. ND, not detectable by the type of qPCR shown; *, detectable nonquantifiable samples (limits of quantification of 0.90 and 1.53 par.eq/ml for the kDNA and SatDNA qPCRs, respectively).

DISCUSSION

The dose and duration of treatment with benznidazole have been largely debated since the appearance of this drug, mainly with regard to administration for 30 versus 60 days. At present, it is presumed that the effective dose might be lower, and the best administration scheme to either avoid or diminish adverse effects as well as to increase efficacy is not yet known.

The findings of this pilot study show a satisfactory safety profile following intermittent administration of benznidazole, with a low rate of treatment suspension and a low rate of treatment failure, as assessed by qPCR 1 week after the end of treatment.

The mechanisms of action of antimicrobial treatments can be classified into two groups: concentration dependent and time dependent (18). In the former, the effect is obtained with maximum concentrations of the drug produced rapidly, while in the time-dependent group, the effect is achieved with constant drug concentrations slightly higher than the MIC. It is likely that a constant concentration of benznidazole as described for a time-dependent effect of treatment is not essential, supporting, at least from a theoretical point of view, the use of intermittent administration of benznidazole.

During its cell cycle in mammalian cells, Trypanosoma cruzi is able to invade various tissues; within the cell, the amastigote form is reproduced approximately every 12 h, completing 9 binary divisions in cell culture (19, 20). Parasitized cells are full of amastigotes within 5 days of multiplication (19).

The development of new anti-T. cruzi drugs is auspicious, but so far the outcomes with new drugs have not been as good as expected (21, 22). However, the efficacy of benznidazole was further reinforced in these studies, since treatment with benznidazole was used as a branch of comparative research. In addition, the scarcity of knowledge about the pharmacology of benznidazole has led the scientific community to point out the necessity to test old and new schemes to improve efficiency and achieve a reduction in adverse effects. Several options have been proposed, including a reduction in dose, changes in the scheme of treatment, or combination of antiparasitic drugs (23).

Of note, a 20% rate of parasitological cure, during a long-term follow-up of patients who received incomplete treatment with benznidazole for a median of 10 days due to the appearance adverse effects, has been reported (13). On the other hand, an experimental study with a mouse model of chronic T. cruzi infection in which an accurate methodology to determine the parasitological cure was used demonstrated the effectiveness of an intermittent scheme of benznidazole administered every 5 days for 40 days, further sustaining the results of this study (14).

The implementation of antiparasitic treatment for adults with chronic Chagas disease is a very important and long-delayed issue in health policy. The lack of early markers of effectiveness and the slow clinical progression in chronically T. cruzi-infected subjects determined that for decades the recommendation of treatment in the chronic phase of Chagas disease was abandoned. Once the idea that treatment in the chronic phase would not be useful had weakened (24), the other major obstacle remained the presence of adverse effects, which generate strong resistance in the medical practice to treatment of chronic Chagas disease patients. In this pilot study, the frequency of severe adverse effects that may lead to treatment suspension was lower than expected according to our experience in the clinical practice, which fluctuates around 20% (25, 26). So far there have not been experimental models available to reproduce benznidazole-induced adverse effects, and thus a pilot study might encourage further studies with experimental models to look for the best intermittent-administration scheme for benznidazole.

Since the efficacy of treatment as measured by qPCR was limited to a short-term follow-up period, these findings should be taken with caution until the low rate of treatment failure can be further confirmed in the longer term. However, the low percentage of detectable PCR found at the end of the intermittent treatment is in agreement with that reported for an experimental mouse model of infection in which this scheme of intermittent doses was first assessed (14), reinforcing the usefulness of animal models to evaluate the efficacy of new drugs or new therapeutic schemes.

Summarizing, the main accomplishment of this pilot study is the promising low rate of treatment suspension. The intermittent administration of benznidazole emerges as a new potential therapeutic scheme whose efficacy should be confirmed by long-term assessment posttreatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Fundación Mundo Sano for financial support to perform the qPCR assays.

Sergio Sosa-Estani and Alejandro Schijman are members of the Scientific Career, CONICET, Argentina. Alejandro Schijman, Marcelo Abril, Sergio Sosa-Estani, and Rodolfo Viotti are members of the Latin American Network for Chagas Disease (NHEPACHA).

REFERENCES

- 1.Richle R. 1973. Chemotherapy of experimental acute Chagas disease in mice: beneficial effects of Ro 7-1051 on parasitaemia and tissue parasitism. Prog Med 101:282. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barclay CA, Cerisola JA, Lugones H, Ledesma O, Lopez Silva J, Mouzo G. 1978. Aspectos farmacológicos y resultados terapéuticos del benznidazol en el tratamiento de la infección chagásica. Prens Med Argent 65:239–244. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viotti R, Vigliano C, Lococo B, Alvarez MG, Petti M, Bertocchi G, Armenti A. 2009. The side effects of benznidazole as treatment in chronic Chagas disease: fears and realities. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 7:157–163. doi: 10.1586/14787210.7.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cançado JR. 2002. Long term evaluation of etiological treatment of Chagas disease with benznidazole. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 44:29–37. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652002000100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Viotti R, Vigliano C, Armenti H, Segura E. 1994. Treatment of chronic Chagas' disease with benznidazole: clinical and serologic evolution of patients with long-term follow-up. Am Heart J 127:151–162. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(94)90521-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fabbro De Suasnabar D, Arias E, Streiger M, Piacenza M, Ingaramo M, Del Barco M, Amicone N. 2000. Evolutive behavior towards cardiomyopathy of treated (nifurtimox or benznidazole) and untreated chronic chagasic patients. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 42:99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallerano RR, Sosa RR. 2000. Interventional study in the natural evolution of Chagas disease. Evaluation of specific antiparasitic treatment. Retrospective-prospective study of antiparasitic therapy. Rev Fac Cien Med Univ Nac Cordoba 57:135–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Viotti R, Vigliano C, Lococo B, Bertocchi G, Petti M, Alvarez MG, Postan M, Armenti A. 2006. Long-term cardiac outcomes of treating chronic Chagas disease with benznidazole versus no treatment. A nonrandomized trial. Ann Intern Med 144:724–734. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sosa-Estani S, Viotti R, Segura E. 2009. Therapy, diagnosis and prognosis of chronic Chagas disease: insight gained in Argentina. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 104:167–180. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762009000900023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Andrade AL, Zicker F, de Oliveira RM, Almeida Silva S, Luquetti A, Travassos LR, Almeida IC, de Andrade SS, de Andrade JG, Martelli CM. 1996. Randomised trial of efficacy of benznidazole in treatment of early Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Lancet 348:1407–1413. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)04128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sosa Estani S, Segura EL, Ruiz AM, Velazquez E, Porcel BM, Yampotis C. 1998. Efficacy of chemotherapy with benznidazole in children in the indeterminate phase of Chagas' disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg 59:526–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altcheh J, Moscatelli G, Mastrantonio G. 2010. Paediatric clinical pharmacology population pharmacokinetics study of benznidazole in children with Chagas disease. Paper 951. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 107(Suppl 1):173. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alvarez MG, Vigliano C, Lococo B, Petti M, Bertocchi G, Viotti R. 2012. Seronegative conversion after incomplete benznidazole treatment in chronic Chagas disease. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 106:636–638. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bustamante JM, Craft JM, Crowe BD, Ketchie SA, Tarleton RL. 2014. New, combined, and reduced dosing treatment protocols cure Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice. J Infect Dis 209:150–162. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramírez JC, Cura CI, Moreira OC, Lages-Silva E, Juiz N, Velázquez E, Ramírez JD, Alberti A, Pavia P, Flores-Chávez MD, Muñoz-Calderón A, Pérez-Morales D, Santalla J, Guedes PMM, Peneau J, Marcet P, Padilla C, Cruz-Robles D, Valencia E, Crisante GE, Greif G, Zulantay I, Costales JA, Alvarez-Martínez M, Martínez NE, Villarroel R, Villarroel S, Sánchez Z, Bisio M, Parrado R, Galvão LMC, da Câmara ACJ, Espinoza B, de Noya BA, Puerta C, Riarte A, Diosque P, Sosa-Estani S, Guhl F, Ribeiro I, Aznar C, Britto C, Yadón ZE, Schijman AG. 2015. Analytical validation of qPCR methods for quantification of Trypanosoma cruzi DNA in blood samples from Chagas disease patients. J Mol Diagn 17:605–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Cancer Institute. 14 June 2010. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) version 4.03. National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuschnir E, Sgammini H, Castro R, Evequoz C, Ledesma R, Brunetto J. 1985. Valoración de la función cardiaca por angiografía radioisotópica, en pacientes con cardiopatía chagásica crónica. Arq Bras Cardiol 45:249–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soriano F. 2002. Aspectos farmacocinéticos y farmacodinámicos para la lectura interpretada del antibiograma. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 20:407–412. doi: 10.1016/S0213-005X(02)72829-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brener Z. 1973. Biology of Trypanosoma cruzi. Annu Rev Microbiol 27:347–382. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.27.100173.002023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martins AV, Gomes AP, Gomes de Mendonça E, Lopes Rangel Fietto J, Santana LA, Goreti de Almeida Oliveira M, Geller M, de Freitas Santos R, Vitorino RR, Siqueira-Batista R. 2012. Biology of Trypanosoma cruzi: an update. Infection 16:45–58. doi: 10.1016/S0123-9392(12)70057-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Molina I, Gómez i Prat J, Salvador F, Treviño B, Sulleiro E, Serre N, Pou D, Roure S, Cabezos J, Valerio L, Blanco-Grau A, Sánchez-Montalvá A, Vidal X, Pahissa A. 2014. Randomized trial of posaconazole and benznidazole for chronic Chagas' disease. N Engl J Med 370:1899–1908. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torrico F. 2013. Resultados de un ensayo clínico de prueba de concepto en pacientes con enfermedad de Chagas indeterminada crónica, abstr E1224 Simposio ASTMH organizado por DNDi Enfermedad de Chagas: Avances Recientes en Investigación y Desarrollo,” sesión no. 53, 14 November 2013 American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, Deerfield, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pérez-Mazliah D, Álvarez M, Cooley G, Lococo BE, Bertocchi G, Petti M, Albareda MC, Armenti AH, Tarleton RL, Laucella SA, Viotti R. 2013. Sequential combined treatment with allopurinol and benznidazole in the chronic phase of Trypanosoma cruzi infection: a pilot study. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:424–437. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viotti R, Alarcón de Noya B, Araujo-Jorge T, Guhl F, López MC, Ramsey JM, Ribeiro I, Schijman A, Sosa-Estani S, Torrico F, Gascon J, Latin American Network for Chagas Disease (NHEPACHA) . 2014. Towards a paradigm shift in the treatment of chronic Chagas disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:635–639. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01662-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sosa-Estani S, Armenti A, Araujo G, Viotti R, Lococo B, Ruiz Vera B, Vigliano C, De Rissio AM, Segura EL. 2004. Tratamiento de la enfermedad de Chagas con benznidazol y ácido tióctico. Medicina (Buenos Aires) 64:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasslocher-Moreno A, do Brasil P, de Sousa A, Xavier S, Chambela M, Sperandio da Silva G. 2012. Safety of benznidazole use in the treatment of chronic Chagas' disease. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:1261–1266. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]