Abstract

Background and purpose — During the last decade, many hospitals have implemented fast-track protocols for total knee arthroplasty (TKA). These protocols reduce the length of hospital stay, but there is no literature on the first period after hospital discharge. We determined how patients experienced the first 6 weeks after hospital discharge after fast-track TKA surgery.

Patients and methods — 34 consecutive patients who had TKA surgery with fast track received a diary for 6 weeks, which contained various international validated questionnaires. In addition, general questions regarding pain, the wound, physiotherapy, and thrombosis prophylaxis injections were posed.

Results — 4 of the 34 patients were excluded during the study. Of the remaining 30 patients, 28 were positive regarding the short length of hospital stay. Pain gradually decreased and quality of life and function gradually improved during the 6 weeks. Mean hours of weekly physiotherapy were 0.6 for the first week and 0.9 during the sixth week, with high variance of treatment modalities due to the lack of standardized treatment protocols. Additional clinical consultations were needed in 9 patients during the 6-week period.

Interpretation — 28 of 30 patients were satisfied with the short length of hospital stay. The intensity of physiotherapy was surprisingly low. The quality of life 6 weeks after discharge was similar to that before the surgery.

Historically, patients were usually hospitalized for several weeks after total knee arthroplasty (TKA), which mainly consisted of a period of bed rest (Berger et al. 2009). However, the length of hospital stay after TKA has decreased in the last decade through implementation of fast-track protocols (Weingarten et al. 1998, Kim et al. 2003, Husted et al. 2008, Barbieri et al. 2009, Husted et al. 2012). Moreover, the quality of life after TKA with fast track improves substantially during the first 3 months after hospital discharge, compared to the quality of life of patients treated with a non-fast-track protocol (Larsen et al. 2008). Also, a decrease in the number of complications and re-admissions can be achieved with fast track (Dowsey et al. 1999, den Hertog et al. 2012). The prevalence of manipulation under anesthesia for stiffness of the knee has been found to be lower or comparable with the use of fast-track protocols, compared to conventional pathways (Husted et al. 2015) and the risk of thromboembolic complications is reduced (Husted et al. 2010b). Fast-track protocols have proven to be safe for patients, including the elderly (Jorgensen and Kehlet 2013).

Most studies of fast-track surgery have focused on optimizing the hospital stay or have evaluated functioning of the patient 6 weeks after surgery. To our knowledge, no studies have been performed in which the first weeks after hospital discharge following TKA surgery with fast-track protocol were analyzed. We therefore determined how patients experienced the first 6 weeks after hospital discharge after TKA surgery with fast track.

Patients and methods

Patients

Consecutive primary TKA patients, operated at the Reinier de Graaf Hospital, Delft, between January 2014 and November 2014 were asked to participate. Exclusion criteria were: patients with revision TKA surgery, patients with an insufficient command of Dutch, mentally disabled patients, and patients in which a prosthesis in another joint of the ipsilateral or contralateral lower limb had been placed within 6 months before TKA surgery. All patients received the NexGen prosthesis (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN) through an anteromedial approach.

The fast-track protocol in our institution is summarized in Table 1. The discharge criteria were functional: patients had to be able to walk 30 meters with crutches, climb stairs, dress independently, and go to the toilet independently. In addition, sufficient pain relief had to have been achieved by oral medication before discharge, with a numeric rating scale (NRS) pain score below 3 at rest and below 5 during mobilization.

Table 1.

Summary of the fast-track protocol

| • Preoperative education |

| • Spinal anesthesia with additional local infiltration anesthesia |

| • Standardized protocol for pain medication |

| • Opioid medication only on request (rescue medication) |

| • No drains |

| • No standard urine catheters |

| • Start rehabilitation and mobilization on day of surgery |

| • Checking the fulfillment of discharge criteria twice a day |

| • Optimization of the aftercare |

Measurements

Preoperatively, all the patients completed an NRS pain score, the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score–Physical Function Short Form (KOOS-PS), Oxford knee score (OKS), and the Euro Quality of Life (EQ-5D). At discharge, all the patients received a diary which contained specific questionnaires for each day. The questionnaires included were: KOOS-PS, OKS, EQ-5D, SF-12, and the Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain score (ICOAP). The SF-12 provides a physical component subscale (PCS) and a mental component subscale (MCS) (Ware et al. 1996). The EQ-5D score varies between −0.333 and 1.000, in which 1.000 represents full health (Lamers et al. 2005). The OKS score ranges from 0 to 48, where 48 is the best function and pain score. The KOOS-PS score ranges from 0 to 100%, where 0 represents no difficulty in physical functioning. NRS for pain was scored every day, which represented the mean pain score for that day.

The preoperative questions were answered digitally a few weeks before the surgery. Patients started to complete the diary on the day of discharge. Occasions when patients had to complete the questionnaires are shown in Table 2. In addition, general questions regarding pain, the wound, physiotherapy, and thrombosis injections were added each day. Table 3 (see Supplementary data) provides an English translation of the general questions. These questions were composed based on the outcome of 2 focus group meetings, which we organized before we performed the present study (Egmond et al. 2015).

Table 2.

Frequency of the questionnaires

| Questionnaire | Frequency |

|---|---|

| KOOS-PS | Preoperatively, twice a week |

| OKS | Preoperatively, once a week |

| EQ-5D | Preoperatively, twice a week |

| SF-12 | Once at week 2, once at week 6 |

| ICOAP | Once a week |

| General satisfaction | Once a week |

KOOS-PS: Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score - Physical Function Short Form score;

OKS: Oxford knee score;

SF-12: 12-item Short Form Health Survey score;

EQ-5D: Euro Quality of Life 5-dimensions score;

ICOAP: Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain score.

The length of hospital stay was defined by the number of nights the patients were kept in hospital. At discharge, all of them received a prescription for 1 week of celecoxib (200 mg once a day), which could be used in addition to paracetamol (1 g 4 times a day). If necessary, additional pain medication such as tramadol (50 mg) or oxycodone (5 mg) was prescribed. During the study, we called all patients every week to check if there were problems in completing the questions in the diary. After 6 weeks, the patients returned their completed diary when they visited the outpatient clinic.

Statistics

No sample size calculation was done, since this was an observational pilot study. Missing data were handled according to the rules of the specific questionnaire. The distribution of the outcomes was determined by the Shapiro-Wilk test, given the number of patients included in this study. Descriptive statistics were obtained to evaluate the results. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) analyses with an exchangeable correlation structure were applied to study the changes in pain, quality of life, and function scores over time. We used IBM SPSS statistics for Windows version 21 for statistical analysis. Any p-value of 0.05 or less was considered to be statistical significant.

Ethics

The study protocol (NL45040.098.13) was approved by the local ethics committee and all participants gave their written informed consent.

Results

Between January 2014 and November 2014, 78 patients were eligible for the study and 24 of them were included. 13 patients were excluded due to insufficient command of Dutch or to co-morbidity, and 31 patients declined participation. During the study, 4 patients were excluded: for 3 of them, the diary was not completed correctly and more than half of the answers were missing. In 1 patient, the TKA was complicated by a lateral collateral ligament rupture; the patient was treated with a brace and was therefore excluded.

The mean age of the remaining 30 patients was 68 (range 52–85) years old, and 18 patients were female. Mean BMI was 29 (19–40). Patients were admitted on the day of surgery. Since length of stay was not normally distributed, the median was 2.5 (IQR 1) nights. All patients went home after discharge. No complications were found during the hospital stay.

Pain

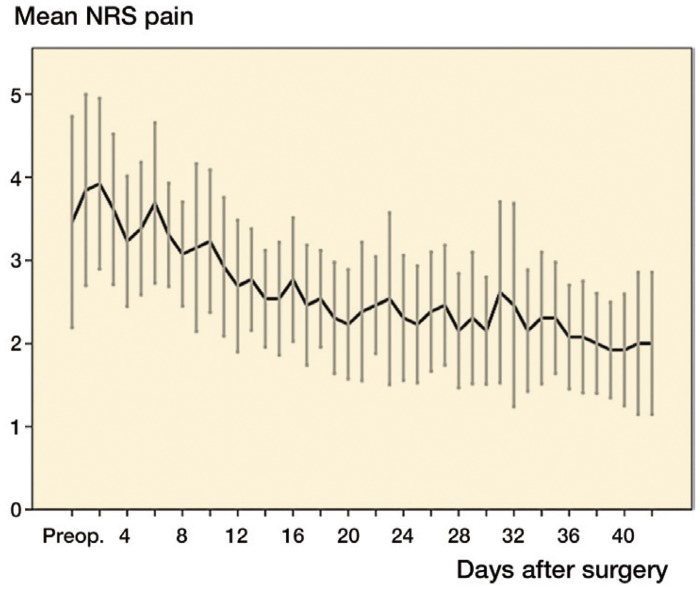

The mean preoperative NRS pain score was 3.6 (SD 2.3) during rest. The mean pain scores on day 1 and day 42 were 3.6 (SD 1.5) and 1.9 (SD 1.4), respectively (p < 0.01). In all patients, the NRS pain score gradually decreased over the 6-week period (Figure 1). GEE showed a statistically significant decrease from day 14 compared to day 1, and this persisted to day 42. (All pain scores given are a mean pain score for the day).

Figure 1.

Mean NRS pain score. Error bars are 95% CI.

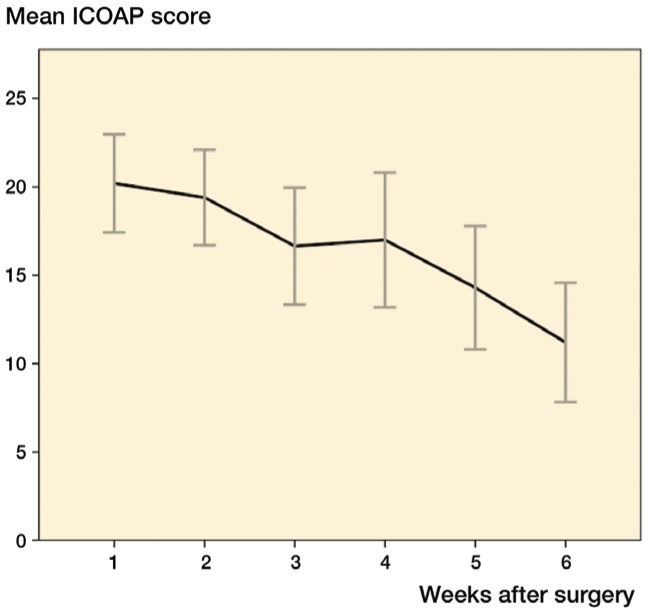

Moreover, the mean ICOAP total score gradually decreased. The mean total ICOAP score for week 1 was 21 (SD 6.7) on a scale from 0 to 44, where 44 is maximum pain, and for week 6 it was 12 (SD 7.1). The ICOAP total score decreased after week 2 (p < 0.01) which was maintained during the following weeks (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean ICOAP score. Error bars are 95% CI.

Pain medication

During the first week, all patients used paracetamol, 27 patients used celecoxib, 12 patients used tramadol, and 5 patients used oxycodon. The use of pain medication slightly declined over the following weeks.

Wound care

In 13 patients, the wound leaked blood or wound serum on the first day after discharge, which had decreased but persisted in 4 patients at the end of week 2. After discharge, 4 patients experienced problems with dressing the wound. These problems were mostly based on fear and uncertainty in treating the wound correctly.

Anticoagulation

All patients were prescribed low-molecular-weight heparin injections once a day for 6 weeks, which they had to inject into their subcutaneous abdominal fat. The complaints regarding the injections increased during the 6 weeks. 6 patients had complaints regarding the injections on week 1. This had increased to 12 patients by week 6.

Complications

During the first 6 weeks after hospital discharge, before the patients had had their first outpatient control visit, 9 patients had visited a doctor because of health problems related to the TKA, such as (groundless) fear of wound infection and problems sleeping. Most of the visits (5 patients) were during the first week after hospital discharge. 6 patients visited the outpatient clinic for wound leakage, fear of infection, pain, and extension deficit. In 1 of the cases, medication was prescribed; the other cases were treated by watchful waiting. 3 patients visited their general practitioner for insomnia and for fear of wound infection; all of them were given medication. None of the patients had to be re-admitted to hospital.

Physiotherapy

The mean amount of physiotherapy per week was 0.6 hours during week 1 and 0.9 hours during week 6. The treatment modality of the physiotherapist varied between patients.

Functioning

Preoperatively, the OKS was 23 (SD 8.1). In the first week after discharge, the mean value of the OKS was 25 (SD 4.3). After week 2, the OKS gradually increased to 35 (SD 6.4) at week 6 (p < 0.01) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mean OKS score. Error bars are 95% CI.

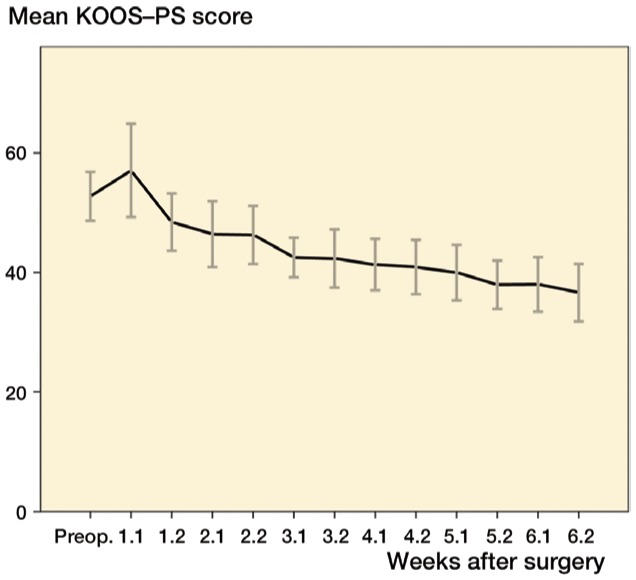

The preoperative KOOS-PS score was 50 (SD 12). From week 3 to week 6, a gradual decrease occurred (p < 0.01) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Mean KOOS-PS score, scored twice every week. Error bars are 95% CI.

Sleep

During the first 2 weeks, 70–80% of the patients rated their sleep to be good or reasonable. At week 6, all the patients had good or reasonable sleep.

Quality of life

The median daily mean SF-12 scores on the second week after discharge were 31 (IQR 6.5) on the PCS and 54 (IQR 18.8) on the MCS. At week 6, the median daily mean PCS score had increased to 35 (IQR 8.5) (p < 0.01). On the other hand, the median daily mean MCS did not increase significantly, and was 55 (IQR 15.8) at week 6 (p = 0.3).

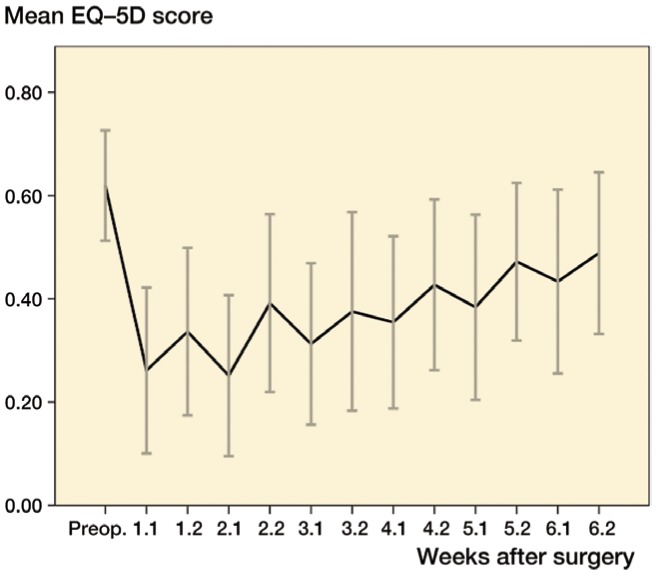

The mean EQ-5D was 0.63 before surgery and decreased to 0.28 one week after discharge (p < 0.01). During the weeks that followed, the EQ-5D gradually increased until week 5 (p < 0.05). At week 6, patients scored 0.51 for the EQ-5D. However, the mean daily score at week 6 was still less than preoperatively (p = 0.2) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Mean EQ-5D score, scored twice every week. Error bars are 95% CI.

General patient satisfaction

28 patients were pleased with the short hospital stay. The reason that 2 patients would have liked to have stayed longer in hospital was because both of them did not feel ready to be at home, despite the fact that they met the discharge criteria. After 6 weeks, patients rated their satisfaction regarding the effect of the prosthesis as 7.7 on a scale from 0 to 10. 20 patients indicated that there was an improvement in functioning during daily activities compared to their preoperative function.

Discussion

In general, most patients were satisfied with their short hospital stay, and preferred to complete the rehabilitation at home instead of in hospital.

9 of 30 patients visited a doctor before the routine outpatient control visit at 6 weeks. Husted et al. (2010a) found a re-admission rate of 16% at 90 days after fast-track TKA. The high rate of medical consultation in our study might be explained by the easy access to the hospital for patients who undergo arthroplasty. A specialized nurse can be contacted during the weeks after surgery, and when patients are in doubt, an appointment can be made with the doctor. This procedure is part of the fast-track protocol. Most patients visited a doctor because they were concerned about possible health problems. In most cases, no treatment was needed; in the other cases, oral antibiotics were prescribed.

The patients experienced most pain during the first 2 weeks after discharge, and 5 patients needed oxycodone in the second week to achieve enough pain relief. Otherwise, good pain relief had been achieved with the standard prescribed medication. We presume that the high intake of paracetamol was probably the result of its accessibility, since it is available without a doctor’s prescription. The high pain scores during the first 2 weeks is in accordance with the findings of Chan et al. (2013). Andersen et al. (2009) found moderate pain scores and concomitant use of opioid medication in half of the patients 1 month after TKA (Andersen et al. 2009).

As described by Lee et al. (2003), the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) in a functional outcome score is of more importance than a significant change in that score (Lee et al. 2003). Beard et al. (2015) have found that an MCID of 9 points in the OKS is needed to detect a change over time in a group of patients. In the present study, an increase of 10 points was measured in 6 weeks, and therefore knee functioning improved beyond the MCID. Singh et al. (2014) found that the MCID for the ICOAP was 18.5 points and that it was 2.2 points for the KOOS-PS. We found a decrease of 9 points in 6 weeks for the ICOAP and a decrease of 20 points in 6 weeks for the KOOS-PS.

In contrast to the study by Schneider et al. (2009) in which 12% of the patients were given physiotherapy, all our patients received physiotherapy. However, the total number of hours of physiotherapy was lower than we had expected. Moreover, the type of treatment varied between patients. As concluded by Bandholm and Kehlet (2012), physiotherapy exercises, including strength training, should be initiated early after surgery and should be intensive—to reduce the loss of muscle strength and function. On the other hand, a study by Jakobsen et al. (2014) concluded that additional progressive strength training does not give any improvement in functional performance. No standardized treatment protocol for physiotherapy is available; only recommendations have been made by the KNGF (Dutch physical therapy organisation). In these recommendations, massage, balance exercise, and gait exercise are not recommended. There is a need for a standardized rehabilitation protocol as described in the systematic review by Pozzi et al. (2013) and also by Peter et al. (2014).

In our previous study, patients described difficulties in injecting themselves with anticoagulation medication (Egmond et al. 2015). In the present study, 12 of 30 patients experienced problems in injecting themselves. Thus, the type of anticoagulation treatment should be reconsidered. Furthermore, there is a lower risk of thromboembolic incidents in fast track, so a shorter duration of anticoagulation therapy should be considered (Husted 2010b, Kjaersgaard-Andersen and Kehlet 2012, Jorgensen et al. 2013).

In this study, most patients slept well during the first 6 weeks. Pain was the most frequent reason given for insomnia, and only 3 patients needed a prescription for sleep medication.

The study had some limitations. Firstly, since this was a pilot study, the patient numbers were small. Secondly, it was a single-arm study with no controls. Thirdly, no objective physical examination function scores were used—only questionnaires. Fourthly, we attempted to have a representative patient group from our clinical practice, so the inclusion and exclusion criteria were straightforward. Although we excluded several patients because of other prosthesis surgery or poor command of the language (Dutch), we presume that our patient group was representative of our clinical practice. Since an appreciable amount of effort is needed to complete all the questionnaires in the diary, several patients refused to join the study. This may have led to selection bias, so that only the motivated patients completed the questionnaires. Based on the variety of reactions of the patients, we presume that this had no influence on the outcome.

Lastly, healthcare in the Netherlands is in several ways differently organized from that in other countries, so the outcome of this study cannot always be compared to the outcomes of other studies. Moreover, the infrastructure is different: all patients have quite easy access to a physiotherapist, a general practitioner, and a hospital. In addition, general practitioners and hospitals have an almost round-the-clock care system.

In conclusion, with concomitant use of analgesics patients experienced most pain during the first 2 weeks after discharge. The pain and the use of analgesics gradually decreased over 6 weeks. Moreover, functioning increased, and even during the first week after surgery patients had a better function score than preoperatively. Although 28 of 30 patients were positive regarding their early discharge after TKA with fast track, 9 patients had consulted their general practitioner or our institution before the outpatient visit 6 weeks after discharge. Most consultations were for anxiety about wound infection, pain, or insomnia, and most patients were treated with watchful waiting.

Supplementary data

Table 3 is available at the Acta Orthopaedica website at www.actaorthop.org, identification number 8922.

No competing interests declared.

We thank the Foundation for Scientific Research of Reinier de Graaf Groep, Delft, for funding this study. We are grateful to all the patients for their efforts in completing their diaries, and we especially thank N. de Esch for her help during the study.

JE composed the diary, and performed the data collection and data analysis. He wrote and revised the manuscript. NM designed the study, supported data analysis, and critically reviewed the manuscript. HV operated several of the patients, designed the study, and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

References

- Andersen L O, Gaarn-Larsen L, Kristensen B B, Husted H, Otte K S, Kehlet H.. Subacute pain and function after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Anaesthesia 2009; 64 (5): 508-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandholm T, Kehlet H.. Physiotherapy exercise after fast-track total hip and knee arthroplasty: time for reconsideration? Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012; 93 (7): 1292-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri A, Vanhaecht K, Van Herck P, Sermeus W, Faggiano F, Marchisio S, et al. Effects of clinical pathways in the joint replacement: a meta-analysis. BMC Med 2009; 7: 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard D J, Harris K, Dawson J, Doll H, Murray D W, Carr A J, et al. Meaningful changes for the Oxford hip and knee scores after joint replacement surgery. J Clin Epidemiol 2015; 68 (1): 73-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger R A, Sanders S A, Thill E S, Sporer S M, Della Valle C.. Newer anesthesia and rehabilitation protocols enable outpatient hip replacement in selected patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467 (6): 1424-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan E Y, Blyth F M, Nairn L, Fransen M.. Acute postoperative pain following hospital discharge after total knee arthroplasty. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013; 21 (9): 1257-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hertog A, Gliesche K, Timm J, Muhlbauer B, Zebrowski S.. Pathway-controlled fast-track rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized prospective clinical study evaluating the recovery pattern, drug consumption, and length of stay. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2012; 132 (8): 1153-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowsey M M, Kilgour M L, Santamaria N M, Choong P F.. Clinical pathways in hip and knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomised controlled study. Med J Aust 1999; 170 (2): 59-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egmond J C, Verburg H, Vehmeijer S B W, Mathijssen N M C.. Early follow-up after primary total knee and total hip arthroplasty with rapid recovery: Focus groups. Acta Orthopaedica Belgica. In press 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Holm G, Jacobsen S.. Predictors of length of stay and patient satisfaction after hip and knee replacement surgery: fast-track experience in 712 patients. Acta Orthop 2008; 79 (2): 168-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Otte K S, Kristensen B B, Orsnes T, Kehlet H.. Readmissions after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010a; 130 (9): 1185-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Otte K S, Kristensen B B, Orsnes T, Wong C, Kehlet H.. Low risk of thromboembolic complications after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2010b; 81 (5): 599-605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Jensen C M, Solgaard S, Kehlet H.. Reduced length of stay following hip and knee arthroplasty in Denmark 2000-2009: from research to implementation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2012; 132 (1): 101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Jorgensen C C, Gromov K, Troelsen A.. Low manipulation prevalence following fast-track total knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (1): 86-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen T L, Kehlet H, Husted H, Petersen J, Bandholm T.. Early progressive strength training to enhance recovery after fast-track total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014; 66 (12): 1856-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen C C, Kehlet H.. Role of patient characteristics for fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth 2013; 110 (6): 972-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen C C, Jacobsen M K, Soeballe K, Hansen T B, Husted H, Kjaersgaard-Andersen P, et al. Thromboprophylaxis only during hospitalisation in fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty, a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2013; 3 (12): e003965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Losina E, Solomon D H, Wright J, Katz J N.. Effectiveness of clinical pathways for total knee and total hip arthroplasty: literature review. J Arthroplasty 2003; 18 (1): 69-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaersgaard-Andersen P, Kehlet H.. Should deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis be used in fast-track hip and knee replacement? Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (2): 105-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers L M, Stalmeier P F M, McDonnell J, Krabbe P F M, van Busschbach J J.. Kwaliteit van leven meten in economische evaluaties: het Nederlands EQ-5D-tarief. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2005; (149): 1574-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen K, Sorensen O G, Hansen T B, Thomsen P B, Soballe K.. Accelerated perioperative care and rehabilitation intervention for hip and knee replacement is effective: a randomized clinical trial involving 87 patients with 3 months of follow-up. Acta Orthop 2008; 79 (2): 149-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J S, Hobden E, Stiell I G, Wells G A.. Clinically important change in the visual analog scale after adequate pain control. Acad Emerg Med 2003; 10 (10): 1128-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter W F, Nelissen R G, Vlieland T P.. Guideline recommendations for post-acute postoperative physiotherapy in total hip and knee arthroplasty: are they used in daily clinical practice? Musculoskeletal Care 2014; 12 (3): 125-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzi F, Snyder-Mackler L, Zeni J.. Physical exercise after knee arthroplasty: a systematic review of controlled trials. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2013; 49 (6): 877-92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M, Kawahara I, Ballantyne G, McAuley C, Macgregor K, Garvie R, et al. Predictive factors influencing fast track rehabilitation following primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2009; 129 (12): 1585-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J A, Luo R, Landon G C, Suarez-Almazor M.. Reliability and clinically important improvement thresholds for osteoarthritis pain and function scales: a multicenter study. J Rheumatol 2014; 41 (3): 509-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J Jr., Kosinski M, Keller S D.. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996; 34 (3): 220-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weingarten S, Riedinger M S, Sandhu M, Bowers C, Ellrodt A G, Nunn C, et al. Can practice guidelines safely reduce hospital length of stay? Results from a multicenter interventional study. Am J Med 1998; 105 (1): 33-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.