Abstract

Background and purpose — There have been few comparative studies on total knee replacement (TKR) with cemented tibia and uncemented femur (hybrid TKR). Previous studies have not shown any difference in revision rate between cemented and hybrid fixation, but these studies had few hybrid prostheses. We have evaluated the outcome of hybrid TKR based on data from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR).

Patients and methods — We compared 4,585 hybrid TKRs to 20,095 cemented TKRs with risk of revision for any cause as the primary endpoint. We included primary TKRs without patella resurfacing that were reported to the NAR during the years 1999–2012. To minimize the possible confounding effect of prosthesis brands, only brands that were used both as hybrids and cemented in more than 200 cases were included. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Cox regression analysis were done with adjustment for age, sex, and preoperative diagnosis. To include death as a competing risk, cumulative incidence function estimates were calculated.

Results — Estimated survival at 11 years was 94.3% (95% CI: 93.9–94.7) in the cemented TKR group and 96.3% (CI: 95.3–97.3) in the hybrid TKR group. The adjusted Cox regression analysis showed a lower risk of revision in the hybrid group (relative risk = 0.58, CI: 0.48–0.72, p < 0.001). The hybrid group included 3 brands of prostheses: LCS classic, LCS complete, and Profix. Profix hybrid TKR had lower risk of revision than cemented TKR, but the LCS classic and LCS complete did not. Kaplan-Meier estimated survival at 11 years was 96.8% (CI: 95.6–98.0) in the hybrid Profix group and 95.2% (CI: 94.6–95.8) in the cemented Profix group. Mean operating time was 17 min longer in the cemented group.

Interpretation — Survivorship of the hybrid TKR at 11 years was better than that for cemented TKR, or the same, depending on the brand of prosthesis. Hybrid fixation appears to be a safe and time-efficient alternative to cemented fixation in total knee replacement surgery.

Total knee joint replacement (TKR) is a highly successful operation with survival rates of more than 90% at 10 years (Carr et al. 2012). Only a few large comparative studies on different designs have been published (Knutson et al. 1986, Rand and Ilstrup 1991, Knutson et al. 1994, Robertsson 2000, Furnes et al. 2002, 2007, Sibanda et al. 2008). Most previous studies were not conclusive, due to their being too small or being biased with potential conflicts of interests (Carr et al. 2012). In the only meta-analysis on this topic, Nakama et al. (2012) found only 3 small randomized controlled studies that could be included for quantitative analysis. These authors were not able to make any conclusions about whether the prostheses should be cement-fixated, cementless, or hybrid.

The fixation of primary TKRs has been extensively discussed, but no general agreement has been reached (Nakama et al. 2012). Cemented prostheses are regarded as the gold standard for TKR, supported by the long-term clinical success and survivorship analysis from registry-based and clinical studies (Robertsson 2000, Bellemans et al. 2005, Nakama et al. 2012). Cementless fixation is, however, still of interest to clinicians, who have used it in an attempt to reduce operation time, improve prosthetic durability, and preserve bone stock (Bassett 1998, Duffy et al. 1998, Nelissen et al. 1998, Regner 1998, Abu-Rajab et al. 2006).

There have been few studies comparing the survival of different prosthesis brands and implant designs. A previous study from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR) did not find any significant short-term differences at 5 years between the most commonly used brands in Norway (Furnes et al. 2002). The study did not show any significant differences in the overall revision rates between different fixation methods, but the number of hybrid prostheses was low, with only 739 knees (10%). The median follow-up time was short, number of prosthesis brands was high (7), and the power of the study was low regarding fixation method, due to low numbers of hybrid and cementless prostheses.

In Sweden, almost all TKRs are cemented (SKAR, 2012). In Australia, there is more variation in fixation; more than 20% of TKRs have hybrid fixation (AOA 2012). In the report from 2011, for the first time hybrid fixation performed better than both cemented and cementless fixation at 10 years. Annual cumulative percent revision of primary TKR at 10 years was 5.6% (5.3–6.0) with cement fixation and 5.0 (4.6–5.3) with hybrid fixation (p = 0.02) (AOA 2012).

There have been very few randomized prospective studies comparing primary TKRs using cemented fixation and primary TKRs using hydroxyapatite-coated, hybrid fixation. Most of them have compared uncemented fixation of the tibia and cemented fixation of the tibia. These studies have shown similar or inferior results for uncemented fixation (Nilsson et al. 1999, Regner et al. 2000, Carlsson et al. 2005, Beauprè et al. 2007). Short-term studies of hybrid fixation with cemented femur showed promising results (Faris et al. 2008). However, 1 medium-term report of 65 press-fit condylar arthroplasties had unacceptable implant survivorship and problems with the femoral component (Campbell et al. 1998).

We compared the failure rates and mechanisms of failure of primary hybrid TKRs with those of primary cemented TKRs using the nationwide prospective observational register of knee implants in Norway.

Patients and methods

The Norwegian Orthopaedic Association started the national register for total hip replacements in 1987 (Havelin et al. 1993). In January 1994, the register was expanded to include all joint replacements (Havelin et al. 2000) in order to detect inferior implants, cements, and techniques as early as possible.

At the time of surgery, a form is completed and sent to the register. The form includes information on the hospital performing the procedure, age, sex, laterality, ASA category, date of surgery, preoperative diagnosis, previous knee surgery, prosthesis type and brand, prophylactic antibiotics, antithrombotic medication, approach (minimally invasive or not), surgical method, fixation method, intraoperative complications, status of the cruciate ligaments, whether the present operation was a primary or secondary procedure (revision), and reason for revision. Revision is defined as complete or partial removal/exchange of the implant, or insertion of a patellar component (Furnes et al. 2002). Primary operations are linked to subsequent revisions by the unique identification number of all Norwegian residents.

Of all the knee replacements performed in Norway, 99% of the primary operations and 97% of the revisions are estimated to be reported to the register (Espehaug et al. 2006).

Patients and follow-up

From January 1, 1999 to December 31, 2012, 36,188 primary TKRs had been reported to the NAR. The regular use of hybrid TKRs in Norway started at the end of 1998. The vast majority of TKRs in Norway are cemented or hybrid fixated, non-patellar resurfaced. We therefore included non-patellar resurfaced primary cemented and hybrid TKRs reported during the years 1999–2012. To minimize the possible confounding effect of prosthesis brands rarely used, such as learning curve, we only included brands used as hybrids and as cemented TKRs in more than 200 cases. 33 different brands were reported to the NAR. Of those, 22 had been used in less than 200 cases and 1 brand had not been used as a hybrid. Of the 10 brands used both with cemented and hybrid fixation, 7 had rarely been used as a hybrid (1–19 cases) and were therefore excluded. The implant brands that fulfilled our criteria were the LCS classic (DePuy), the LCS complete (DePuy), and the Profix (Smith and Nephew).

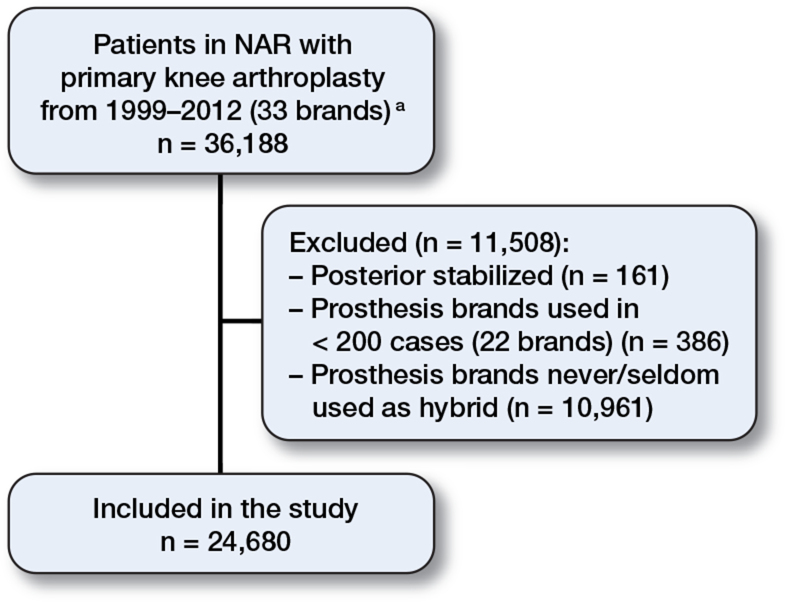

We ended up with 4,585 hybrid TKRs and 20,095 cemented TKRs. There were no hinged, posterior-stabilized, or tumor prostheses in this material (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selection chart showing inclusion and exclusion criteria for total knee replacements in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR) reported during the period 1999–2012. a Patella-resurfaced, hinged, and tumor prostheses are not included in the primary material.

The mean follow-up time was 8.9, 3.4, and 5.7 years in the cemented LCS, LCS complete, and Profix groups and it was 9.0, 3.0, and 4.9 years in the hybrid LCS, LCS complete, and Profix groups, respectively.

Statistics

We compared cemented TKRs with hybrid TKRs with respect to survivorship, using the Kaplan-Meier (KM) method for unadjusted survival rates. Revision was defined as a complete or partial removal/exchange of the implant, or insertion of a patellar component (Furnes et al. 2002). Information on deaths or emigrations was collected from the Norwegian Resident Registration Office until December 31, 2012 (14% in the cemented group and 11% in the hybrid group). The survival of implants in patients who had died or emigrated without revision of the prosthesis was censored at the date of death or emigration. Otherwise, the survival was censored at the end of the study on December 31, 2012. Survival analyses were performed with any revision of the implant as endpoint.

To study the relative risk (RR) between prosthesis fixation types (cemented or hybrid), and between various prosthesis brands, we used a Cox regression model with adjustment for possible confounding by age (< 60 years, 60–70 years, and >70 years), sex, and diagnosis (primary osteoarthritis of the knee, other). Cemented implants were used as the reference group when comparing the 2 fixation methods, while Profix was used as reference when comparing prosthesis brands since this implant was the most used and had been in continuous use throughout the whole study period. The adjusted RR estimates are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values relative to the cemented group. Cox regression was also used to construct survival curves for the treatment groups, with adjustment for the factors described above. Survival curves for the various prosthesis brands were constructed in a similar way. In sub-analyses, the results of hybrid and cemented knees were obtained for each prosthesis brand.

In a Cox analysis with adjustment for age, sex, and diagnosis, we estimated the RR of revision for different reasons in cemented and hybrid TKR. The reasons for revision were loosening of the femoral component, loosening of the tibial component, patellar luxation, instability, malalignment, deep infection, and pain. As the surgeons sometimes report more than 1 reason, infection was considered to be the leading cause of revision if reported together with other reasons, whereas pain was used only if no other reasons were reported. The proportional hazards assumption of the Cox model was tested based on scaled Schoenfeld residuals (Grambsch et al. 1994), and found to be reasonable.

In addition to Cox regression analysis, cumulative incidence function estimates (Fine and Grey) were calculated taking into account the difference in the proportions of dead patients in the 2 groups (14% in the cemented group and 11% in the hybrid group) (Ranstam et al. 2011). The estimates were similar.

To include bilateral knee arthroplasty (18% in these data) may violate the assumption of independent observations in survival analyses. Earlier studies have shown that any possible effect on statistical precision of including bilateral cases is negligible for survival analysis of knee replacements (Robertsson and Ranstam 2003).

SPSS versions 21.0 and 22.0 and R software version 3.0.2 were used for the statistical analyses. P-values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Ethics

The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register has permission from the Norwegian Data Inspectorate to collect patient data based on a concession and dependent on obtaining patient-written consent (issued May 19, 2012, reference number 03/00058-15/JTA)

Results

Demographics

The groups were similar regarding age, sex, laterality, diagnosis, and ASA category (Table 1). As ASA category is a prognostic factor for revision surgery, we chose to investigate the effect of ASA distribution and included it in the Cox model. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups (p = 0.07). Previous surgery of the knee was more common in patients in the hybrid group. In the cemented group, 49% had an intact PCL after the operation whereas in the hybrid group, 68% had an intact PCL postoperatively (Table 1). The main reason for this is that removing the PCL is a standard procedure in the LCS prosthesis.

Table 1.

Demographic data regarding primary total knee replacements without patellar component, hybrid or cemented, reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1999–2012

| Hybrid TKR | Cemented TKR | p-value | |

| Number | 4,585 | 20,095 | |

| Men, % | 34 | 33 | 0.2 |

| Age, years | 69 | 70 | |

| (95% CI) | 68.9–69.4 | 69.6–69.9 | 0.8 |

| Right knee, % | 53 | 54 | 0.2 |

| ASA category a, % | 74 | 70 | 0.7 |

| ASA 1 | 17 | 17 | |

| ASA 2 | 62 | 63 | |

| ASA 3 | 19 | 18 | |

| ASA 4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | |

| ASA missing | 2 | 2 | |

| Diagnosis preoperatively, % | < 0.001 | ||

| Primary osteoarthritis | 90 | 88 | |

| Other | 10 | 12 | |

| Died before revision, % | 11 | 14 | |

| Previous operations of the knee, % | 31 | 29 | 0.001 |

| Osteosynthesis affecting the knee joint | 2 | 2 | 0.2 |

| Osteotomy | 3 | 4 | 0.03 |

| Synovectomi | 1 | 2 | < 0.001 |

| Other | 26 | 22 | < 0.001 |

| Operation time, min (SD) | 79 (28) | 96 (29) | < 0.001 |

| Intact ACL preoperatively, % | 83 | 80 | 0.02 |

| Intact PCL postoperatively, % | 68 | 49 | 0.003 |

aASA category: American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification system, only reported from 2005.

Overall survivorship

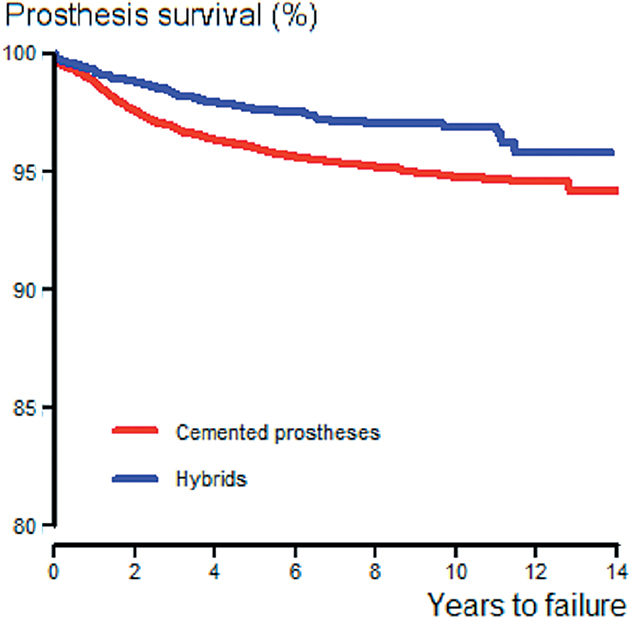

The cemented group had an greater risk of revision than the hybrid group (Figure 2). At 11 years, the KM survivorship was 94.3% (CI: 93.9–94.7) in the cemented TKR group and 96.3% (CI: 95.3–97.3) in the hybrid TKR group. Cox regression analysis, adjusting for age, sex, and preoperative diagnosis, showed a lower RR of revision in the hybrid TKR group than in the cemented TKR group (RR = 0.58, CI: 0.48–0.72; p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Cox regression survivorship of the various fixation methods, adjusted for age, sex, and diagnosis, in hybrid and cemented TKR in Norway 1999–2012.

Table 2.

Kaplan-Meier (KM) survivorship and adjusted Cox regression relative risk (RR) for cemented TKR and hybrid TKR, without patella resurfacing, reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1999–2012

| Revised/total | Median follow-up (IQR) a, years | 11-year KM survivorship (95% CI) | At risk at 11 years | Cox adjustedb RR (95% CI) | |

| Cemented | 787/20,095 | 4.98 (2.52–7.92) | 94.3 (93.9–94.7) | 1,234 | 1 |

| Hybrid | 102/4,585 | 4.60 (1.90–7.66) | 96.3 (95.3–97.3) | 269 | 0.58 (0.48–0.72)c |

a IQR: interquartile range.

badjusted for sex, age, and preoperative diagnosis.

cp < 0.001

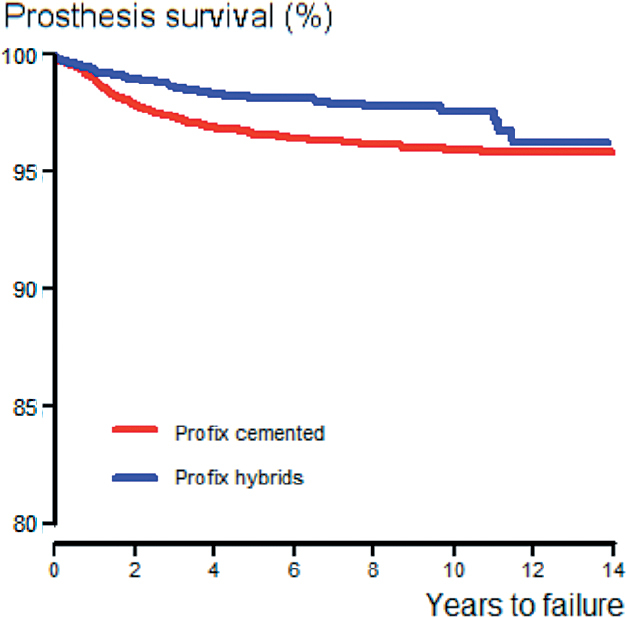

Figure 3.

Cox regression survivorship of the Profix TKR prosthesis with respect to fixation method, adjusted for age, sex, and diagnosis.

Cumulative incidence function estimates, taking into account the difference in the proportions of dead patients in the 2 groups, showed similar results (RR = 0.59, CI: 0.38–0.79; p < 0.001).

Prosthesis brands

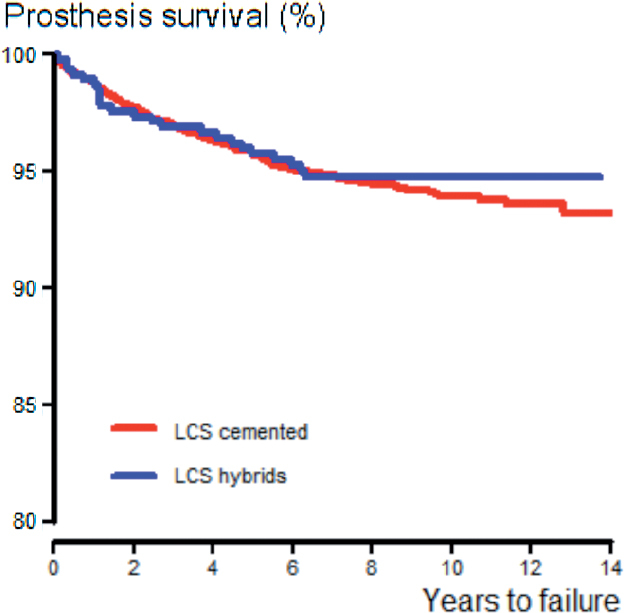

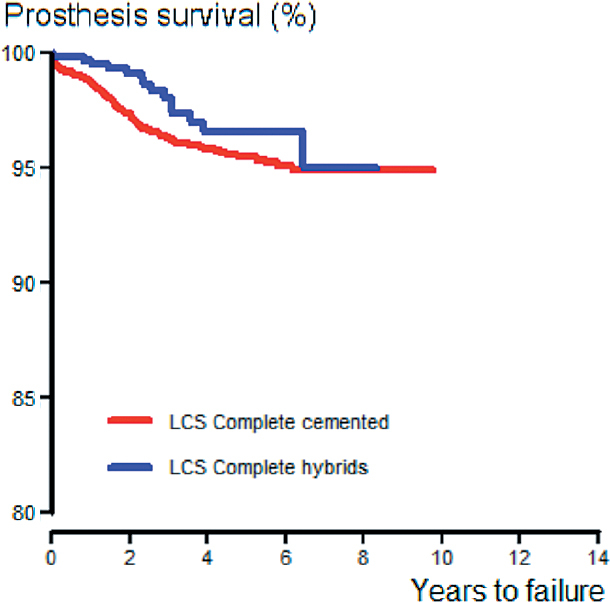

KM-estimated survival at 11 years was 96.8% (CI: 95.6–98.0) in the hybrid Profix group and 95.2% (CI: 94.6–95.8) in the cemented Profix group. The adjusted Cox regression analysis showed a lower risk of revision in the hybrid Profix group (RR = 0.57, CI: 0.44–0.75; p < 0.001) (Table 3). There were no statistically significant differences between cemented and hybrid fixated LCS classic TKRs (Figure 4) and LCS complete TKRs (Figure 5).

Table 3.

Kaplan-Meier (KM) survivorship and adjusted Cox regression relative risk (RR) for different brands of cemented and hybrid TKRs, without patella resurfacing, reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1999–2012

| Revised/total | Median follow-up (IQR) a, years | 6-year survivor-ship (95% CI) | At risk at 6 years | 11-year survivor-ship (95% CI) | At risk at 11 years | Cox adjustedb RR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| LCS classic | ||||||||

| Cemented | 197/3,358 | 8.9 | 94.8 (94.0–95.6) | 2,762 | 93.4 (92.4–94.4) | 710 | 1 | |

| Hybrid | 23/395 | 9.0 | 94.5 (92.1–96.9) | 337 | 0.86 (0.55–1.34) | 0.5 | ||

| LCS complete | ||||||||

| Cemented | 275/7,789 | 3.4 | 94.9 (94.3–95.5) | 933 | 1 | |||

| Hybrid | 14/663 | 3.0 | 96.2 (94.0–98.4) | 81 | 0.62 (0.36–1.06) | 0.08 | ||

| Profix | ||||||||

| Cemented | 315/8,948 | 5.7 | 96.0 (95.6–96.4) | 4,094 | 95.2 (94.6–95.8) | 523 | 1 | |

| Hybrid | 65/3,527 | 4.9 | 97.9 (97.3–98.5) | 1,201 | 96.8 (95.6–98.0) | 197 | 0.57 (0.44–0.75) | < 0.001 |

a IQR: interquartile range.

badjusted for sex, age, and preoperative diagnosis.

Figure 4.

Cox regression survivorship of the LCS TKR prosthesis with respect to fixation method, adjusted for age, sex, and diagnosis.

Figure 5.

Cox regression survivorship of the LCS Complete TKR prosthesis with respect to fixation method, adjusted for age, sex, and diagnosis.

Hospital volume and hospital-specific results

65 centers had performed between 1 and 3,345 TKRs in the observation period; 65 had used cemented fixation (1–2,912 TKRs each) and 29 had used hybrid fixation (1–3,044 TKRs each). There had been 3,752 LCS TKRs operated by 36 centers (1–804 TKRs each). Of those, 395 had been hybrid fixated and 3,358 had been cemented.

There had been 8,452 LCS complete TKRs operated by 37 centers (1–2,108 TKRs each). Of those, 663 had been hybrid fixated and 7,789 had been cemented. 1 center had performed over 27% of all cemented LCS complete TKRs. Exclusion of this center did not affect the results.

There had been 12,475 Profix TKRs operated by 44 centers (1–3,344 TKRs each). Of those, 3,527 had been hybrid fixated and 8,948 had been cemented. 1 center had done almost all the hybrids (n = 3,044). Exclusion of this center affected the results, and the difference between hybrid and cemented fixation was no longer statistically significant (RR = 0.79, 95% CI: 0.44–1.45, p = 0.5). When comparing hybrid TKR and cemented TKR performed at this center, we found no statistically significant difference (RR = 0.85, CI: 0.40–1.80), p = 0.7).

By investigating hospital volume in this study, we found that only 0.6% of the hybrid TKRs and 5.7% of the cemented TKRs had been done by low-volume hospitals. Exclusion of low-volume hospitals did not alter the results (RR = 0.57, CI: 0.46–0.71).

Causes of revision

The most common reasons for revision (in order of frequency) were pain alone, tibial loosening, deep infection, instability, and femoral loosening in the cemented group and deep infection, instability, pain, and tibial loosening in the hybrid group. When we adjusted for age and sex, the hybrid TKRs showed reduced risk of revision due to loosening of the femur and of the tibia, and reduced risk of revision due to pain alone. Revisions due to malalignment and deep infection were less frequent in the hybrid TKR group, but neither difference was statistically significant (Table 4).

Table 4.

Causes of revision and Cox relative risk (RR) with 95% CI, comparing hybrid TKRs with cemented TKRs in total knee replacements reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register, 1999–2012. (There may be more than one cause of revision reported in each revised case)

| Cemented TKR, n (%) | Hybrid TKR, n (%) | RR (95% CI) a | p-value | |

| Loose femur | 82 (0.4) | 3 (0.07) | 0.17 (0.05–0.52) | 0.002 |

| Loose tibia | 222 (1.1) | 10 (0.2) | 0.20 (0.11–0.38) | < 0.001 |

| Patellar dislocation | 5 (0.02) | 1 (0.02) | 0.94 (0.11–8.08) | 1.0 |

| Dislocation, not patella | 24 (0.1) | 3 (0.07) | 0.58 (0.18–1.94) | 0.4 |

| Instability | 104 (0.5) | 28 (0.6) | 1.22 (0.81–1.86) | 0.3 |

| Malalignment | 52 (0.3) | 7 (0.2) | 0.62 (0.28–1.36) | 0.2 |

| Deep infection | 184 (0.9) | 33 (0.7) | 0.81 (0.56–1.17) | 0.3 |

| Pain (alone) | 295 (1.5) | 24 (0.5) | 0.37 (0.24–0.56) | < 0.001 |

aCemented TKR as reference

Operating time

Mean operating time was 17 min longer in the cemented TKR group (Table 1). Using operation time as a confounding factor and adjusting for it did not change the results (RR = 0.62, CI: 0.50–0.77; p < 0.001)

Discussion

In this registry-based study, we found a higher risk of revision in the cemented TKR group than in the hybrid TKR group after 11 years. This may depend on prostheses brand or on the effect of high hospital volume. The majority of the Profix hybrid cases had been operated in 1 hospital. Exclusion of this hospital affected the results, and the difference between hybrid and cemented fixation was no longer statistically significant. Thus, a high-volume effect cannot be excluded.

The main reasons for inferior survivorship were tibial loosening, femoral loosening, and pain in the cemented group. Mean operating time was 17 min shorter in the hybrid group. This reduction in operation time is favorable, as earlier studies have shown a higher postoperative complication rate and increased bacterial contamination of the wound with increased operation time (Jonsson et al. 2014).

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study was the large number of knee replacements. The implant brands studied are widely used in Norway and around the world. The results are therefore relevant to all orthopedic surgeons. The large number of hybrid TKRs contributed to a strong evaluation of this fixation method. The completeness of registration was high (Espehaug et al. 2006), the primary data in the NAR had been validated, and most of the data were correctly registered (Arthursson et al. 2005). Regarding fixation method, no validation is done. All prostheses and cements used in Norway are labeled with stickers by the manufacturers. These stickers include catalog numbers, and they are sent to the registry together with the registration forms that are filled out by the surgeons immediately after surgery. When looking at causes of revision, one has to rely on the registration done by the surgeons who fill out the forms when radiographs, workup to surgery, and visualization during operation have been completed. This reduces the possibility of misclassification of the prosthesis, the fixation technique, and the cause of revision. On the other hand, the main limitation of our study was that most of the hybrid TKRs were done in 1 high-volume center, which is why a positive effect of high-volume surgery cannot be excluded. In a study from the NAR (Badawy et al. 2013), there were higher rates of revision in low-volume hospitals. By examining hospital volume, we found out that only 0.6% of the hybrid TKRs and 6% of the cemented TKRs were done by low-volume hospitals in this study. Exclusion of low-volume hospitals did not alter the results.

Comparison with other studies

There have been few studies involving TKRs with cemented tibia and uncemented femur (hybrid). Previous studies have not shown any difference in revision rate between the different fixation methods, but these studies had very few hybrid prostheses or they mostly compared cemented fixation and cementless fixation of the tibia (Nilsson et al. 1999, Regner et al. 2000, Carlsson et al. 2005, Beauprè et al. 2007, Nakama et al. 2012). In a meta-analysis, Nakama et al. (2012) were unable to evaluate hybrid fixation because the study was not designed to investigate it. The main outcome was to compare cemented tibia with cementless tibia and cemented femur with cementless femur.

Failure of the tibial component is still a major reason for revision in TKR (Paxton et al. 2008). In the hybrid group, there was statistically significantly less loosening of the tibia. This is rather unexpected, as the tibia was cemented in both groups, but one reason for this could be better cementing technique and better timing of the cementation of the tibia when only 1 component is cemented. Failure of the tibial component as the main reason for revision was also the main finding in a review by Cawley et al. (2013); this indicates that optimizing the way in which the cement is applied is important for improvement of survival in TKR.

In an RSA-based study comparing 41 patients randomized to cemented or cementless femoral fixation, there were similar results with both fixation methods after 2 years of follow-up (Gao et al. 2009). This indicates that uncemented femoral components behave as well as cemented femoral components in the long term.

Comparison with other registries

In the Australian Joint Replacement Registry, hybrid TKRs constituted about 20% of all TKRs, and they were doing better than both cemented and uncemented prostheses at 10 years (AOA 2012). Comparison of our data with the Australian data is difficult, because Australian surgeons have another usage profile, with few Profix and LCS prostheses being used. The overall results of that study showed that altogether, hybrid prostheses are doing better (hazard ratio = 1.06, 95% CI: 1.01–1.12; p = 0.02).

In Sweden, hybrids were widely used in the years 1985–1994, but today almost all prostheses are cemented. Subanalysis has shown more revisions in uncemented tibial components than in cemented tibial components, but there were no further data on hybrid prostheses, so comparison between registries was not possible (SKAR 2012).

In New Zealand, no difference was found between hybrids and cemented prostheses (NZOA 2014). It is not possible to compare brand-related results in different registries without having more data. In the UK, 1.1% of all TKRs are hybrids. To date, no statistically significant difference between hybrids and cemented TKRs has been found after 9 years (NJR 2013).

In Denmark, 14% of all TKRs are hybrids. In the last 2 annual reports, hybrids were doing better than cemented TKRs, with a hazard ratio adjusted for age and sex of 0.84 (95% CI: 0.75–0-94) (DKAR 2012).

Comparisons of prosthesis brands between registries are difficult because of differences in presentation and because of the lack of raw data to work with.

Clinical relevance

We believe that our results are of clinical relevance. The NAR, the Australian joint registry, and the Danish joint registry have all had statistically significantly better survival of TKRs with hybrid fixation. None of these registries have shown inferior results with hybrid fixation.

Conclusion

Survivorship of the hybrid primary TKRs at 11 years was the same as or better than that of cemented TKRs, depending on the brand of prosthesis. Hybrid fixation appears to be a safe and time-efficient alternative to cemented fixation in total knee replacement surgery, based on the present study with 11 years of follow-up. An effect of high volume in the hybrid group cannot be excluded in the present study. These results apply to implants used in more than 200 cases. We are unable to make any conclusions about newer implants.

Acknowledgments

GP analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. AMF supervised analysis and wrote the manuscript. LIH wrote the manuscript. ØG wrote the manuscript. SHLL supervised analysis and wrote the manuscript. SMR wrote the manuscript. OF planned the study, supervised analysis, and wrote the manuscript. All the authors contributed to editing and revision of the manuscript.

No competing interest declared.

References

- Abu-Rajab RB, Watson WS, Walker B, Roberts J, Gallacher SJ, Meek RM. Periprosthetic bone mineral density after total knee arthroplasty. Cemented versus cementless fixation. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2006; 88: 606–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthursson AJ, Furnes O, Espehaug B, Havelin LI, Søreide JA. Validation of data in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register the Norwegian Patient Register: 5,134 primary total hip arthroplasties and revisions operated at a single hospital between 1987 and 2003. Acta Orthop 2005; 76(6): 823–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Annual Report. Adelaide:AOA; 2012.

- Badawy M, Espehaug B, Indrekvam K, Engesæter LB, Havelin LI, Furnes O. Influence of Hospital Volume on Revision Rate After Total Knee Arthroplasty with Cement. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2013; 95: e131 (1-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett RW. Results of 1,000 Performance knees: cementless versus cemented fixation. J Arthroplasty 1998; 13: 409–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauprè LA, al-Yamani M, Huckell JR, Johnston DWC. Hydoxyapitite-coated tibial implants compared with cemented tibial fixation in primary total knee arthroplasty. A randomized trial of outcomes at five years. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2007; 89: 2204–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellemans J, Ries MD, Victor J. Total knee arthroplasty. A guide to get better performance. Springer Science & Business Media. 2005.

- Campbell MD, Duffy GP, Trousdale RT. Femoral component failure in hyprid total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1998; 356: 58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson A, Bjorkman A, Besjakov J, Onsten I. Cemented tibial component fixation performs better than cenentless fixation: a randomized radiostereometric study comparing porous-coated, hydroxyapatite-coated and cemented tibial components over 5 years. Acta Orthop 2005; 76: 362–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr AJ, Robertsson O, Graves S, Price AJ, Arden NK, Judge A, Beard DJ. Knee replacement. Lancet 2012; 379: 1331–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawley DT, Kelly N, McGarry JP, Shannon FJ. Cementing techniques for the tibial component in primary total knee replacement. Bone Joint J 2013; 95-B(3): 295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DKAR (Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register). Annual report 2012. Århus Denmark (www.dkar.dk).

- Duffy GP, Berry DJ, Rand JA. Cement versus cementless fixation in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1998; (356): 66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espehaug B, Furnes O, Havelin L, Engesæter LB, Vollset S, Kindseth O. Registration completeness in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2006; 77(1): 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faris PM, Keating EM, Farris A, Meding JB, Ritter MA. Hybrid total knee arthroplasty: 13-year survivorship of AGC total knee systems with average 7 years followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008; 466: 1204–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnes O, Espehaug B, Lie SA, Vollset SE, Engesæter LB, Havelin LI. Early failures among 7.174 primary total knee replacements. A follow-up study from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1994-2000. Acta Orthop Scand 2002; 73(2): 117–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnes O, Espehaug B, Lie SA, Vollset SE, Engesæter LB, Havelin LI. Failure Mechanisms After Unicompartmental and Tricompartmental Primary Knee Replacement with Cement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2007; 89(3): 519–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F, Henricson A, Nilsson KG. Cemented versus uncemented fixation of the femoral component of the NexGen CR total knee replacement in patients younger than 60 years: a prospective randomised controlled RSA study. Knee 2009; 16 (3): 200–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika 1994; 81(3): 515–526. [Google Scholar]

- Havelin LI, Espehaug B, Vollset SE, Engesæter LB, Langeland N. The Norwegian arthroplasty register. A survey of 17, 444 hip replacements 1987-1990. Acta Orthop Scand 1993; 64: 245–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havelin LI, Engesæter LB, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Lie SA, Vollset SE. The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register: 11 years and 73,000 arthroplastiew. Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71: 337–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson EÖ, Johannesdottir H, Robertsson O, Mogensen B. Bacterial contamination of the wound during primary total hip and knee replacement. Acta Orthop 2014; 85(2): 159–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson K, Lindstrand A, Lidgren L. Survival of knee arthroplastiew. A nation-wide multicentre investigation of 8000 cases. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1986; 68: 795–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson K, Lewold S, Robertsson O, Lidgren L. The Swedish knee arthroplasty register. A nation-wide study of 30.003 knees 1976-1992. Acta Orthop Scand 1994; 65: 375–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakama GY, Peccin MS, Almeida G JM, Lira N O DA, Queiroz A AB, Navarro RD. Cemented, cementless or hybrid fixation options in total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis and other non-traumatic diseases. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012; Issue 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- New Zealand Orthopaedic Association The New Zealand Joint Registry. Fifteen year report January 1999 to December 2013. www.nzoa.org.nz/nz-joint-registry; 2014.

- NJR (National Joint Registry for England and Wales). 10th Annual Report 2013. (www.njrcentre.org.uk).

- Nelissen RG, Valstar ER, Rozing PM. The effect of hydoxyapatite on the micromotion of total knee prostheses. A prospective, randomized, double-blind study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1998; 80: 1665–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson KG, Karrholm J, Carlsson L, Dalen T. Hydroxyapatite coating versus cemented fixation of the tibial component in total knee arthroplasty: prospective randomized comparison of hydroxyapatite-coated and cemented tibial components with 5-year follow-up using radiostereometry. J Arthroplasty 1999; 14: 9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton EW, Inacio M, Slipchenko T, Fithian DC. The Kaiser Permanente National Total Joint Replacement Registry. Perm J 2008; 12(3): 12–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand JA, Ilstrup DM. Survivorship analysis of total knee arthroplasty. Cumulative rates of survival of 9200 total knee arthroplastiew. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1991; 73 (3): 397–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranstam J, Kärrholm J, Pulkkinen P, Mäkelä K, Espehaug B, Pedersen AB, Mehnert F, Furnes O. Statistical analysis of arthroplasty data II. Guidelines. 2011; 82 (3): 258–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regner L, Carlsson L, Karrholm J, Herberts P. Ceramic coating improves tibial component fixation in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 1998; 13: 882–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regner L, Carlsson L, Karrholm J, Herberts P. Tibial component fixation in porous- and hydroxyapatite-coated total knee arthroplasty: a radiostereo metric evaluation of migration and inducible displacement after 5 years. J Arthroplasty 2000; 15: 681–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O. The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register. Validity and Outcome. Thesis, University of Lund 2000.

- Robertsson O, Ranstam J. No bias of ignored bilaterality when analysing the revision risk of knee prostheses: analysis of a population based sample of 44,590 patients with 55,298 knee prostheses from the national Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2003; 4: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibanda N, Copley LP, Lewsey JD, Borroff M, Gregg P, MacGregor AJ, Pickford M, Porter M, Tucker K, van der Meulen JH. Revision Rates after Primary Hip Knee Replacements in England between 2003 and 2006. PLoS medicine 2008; 5 (9): 1398–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SKAR (Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register). Annual report 2012. Lund, Sweden (www.knee.se).