Abstract

Background and purpose — Previous studies have found different outcomes after revision of knee arthroplasties performed after high tibial osteotomy (HTO). We evaluated the risk of revision of total knee arthroplasty with or without previous HTO in a large registry material.

Patients and methods — 31,077 primary TKAs were compared with 1,399 TKAs after HTO, using Kaplan-Meier 10-year survival percentages and adjusted Cox regression analysis.

Results — The adjusted survival analyses showed similar survival in the 2 groups. The Kaplan-Meier 10-year survival was 93.8% in the primary TKA group and 92.6% in the TKA-post-HTO group. Adjusted RR was 0.97 (95% CI: 0.77–1.21; p = 0.8).

Interpretation — In this registry-based study, previous high tibial osteotomy did not appear to compromise the results regarding risk of revision after total knee arthroplasty compared to primary knee arthroplasty.

High tibial osteotomy (HTO) is a well-established joint preserving procedure for the treatment of medial knee osteoarthritis. The goal is to achieve unloading of the affected medial compartment of the knee to prevent or postpone the need for an artificial knee joint. This is performed by slightly overcorrecting the knee joint from varus malalignment to valgus or neutral position. Osteotomy was a standard treatment option for unicompartmental knee osteoarthritis in earlier years before knee arthroplasty was a surgical option, but osteotomy lost importance in the 1980s because of the success of knee replacement surgery (Smith et al. 2013). However, there has been an increase in osteotomies during the last 15 years, especially in younger patients in some countries (Seil et al. 2013). National arthroplasty registers have demonstrated higher risk of revision for knee arthroplasty in younger patients (under the age of 60) (NAR 2014, SKAR 2013). The 2 most commonly used methods for HTO are lateral closing wedge and medial opening wedge osteotomy. Both methods have shown improvement in knee pain and function (Naudie et al. 1999, van Raaij et al. 2008, Efe et al. 2011, W-Dahl et al. 2012). Nevertheless, some patients later require a second procedure, a total knee arthroplasty (Naudie et al. 1999), depending on the degree of osteoarthritis, their level of pain and function, and the degree of correction achieved. Although total knee arthroplasty appears to be technically more challenging after HTO in cases with severe overcorrection, bone stock loss, altered joint line (Figures 1 and 2), or patella infera, only a few studies have found inferior results compared to primary TKA (Windsor et al. 1988, Parvizi et al. 2004, Haslam et al. 2007, Farfalli et al. 2012). The aim of this study was to evaluate the risk of revision after TKA, comparing primary TKA with and without previous high tibial osteotomy using data from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR).

Figure 1.

Example of extra-articular malalignment after high tibial osteotomy (HTO) with opening wedge technique. The red line on the left radiograph (a) indicates the mechanical axis lateral to the knee joint. The radiograph to the right (b) indicates the extra-articular angulation of the tibia in the osteotomy area.

Figure 2.

Example of intra-articular malalignment after high tibial osteotomy (WTO) with closing wedge technique. The solid red line indicates that the tibial plateau has been elevated medially and is not perpendicular to the tibial axis.

Material and methods

56,939 primary knee replacements were registered in the NAR between 1994 and 2013. The NAR provides information on specific previous surgery prior to the primary knee replacement surgery, such as previous fractures, meniscectomies, or HTO, in addition to the patient’s diagnosis.

Revision was defined as a partial or complete removal/exchange/addition of implant component(s), and was linked to the primary surgery by the unique national identification number of the patient.

We also obtained anonymous data from the Norwegian Patient Register (NPR) regarding the numbers of HTOs performed in Norway in the period 1999–2013, since primary HTO is not registered in the NAR. The data covered patients with osteoarthritis only. Before1999, another coding system was used, which did not differentiate between osteotomies on the femur or tibia. The date of death and emigration during follow-up was provided by Statistics Norway (Furnes et al. 2002).

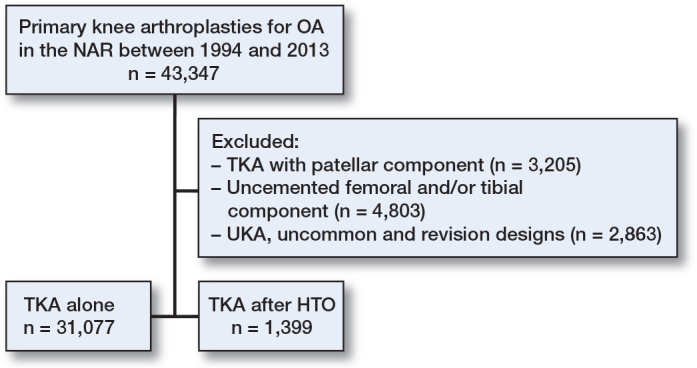

The inclusion and exclusion of patients in this study is shown in Figure 3. To obtain comparable groups for analysis, diagnoses other than osteoarthritis were excluded, giving a total of 43,347 cases. The rationale for this was that HTO is not the method of choice in diagnoses such as inflammatory diseases (and others). TKA without patellar component cemented with antibiotics is the most commonly used combination in Norway. Implant variations could be a source of confounding in comparison of revision rates, so all uncemented implants and total knee replacements with a patellar component were also excluded. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasties, uncommon designs, and constraint implants were also excluded. 31,077 primary TKAs were compared with 1,399 TKAs after HTO. There were 1,387 revisions in the primary TKA group and 83 revisions in the TKA-post-HTO group (Table 1).

Figure 3.

31,077 primary total knee arthroplasties and 1,399 total knee arthroplasties after previous high tibial osteotomy (HTO) were selected for inclusion in the study. Total knee arthroplasties with a patellar component, uncemented total knee arthroplasty, knees treated with unicompartmental or revision implants, and uncommon implant brands were excluded.

Table 1.

Patient and procedure characteristics for TKA with and without previous HTO from 1994 to 2013 with the diagnosis osteoarthritis

| TKA alone | TKA after HTO | p-value | |

| No. of primary procedures | 31,077 | 1,399 | |

| No. of revisions | 1,387 | 83 | 0.01 |

| Male sex, % | 32.4 | 48.8 | 0.001 |

| Age, years a | 71 (28–101) | 69 (41–93) | 0.001 |

| Surgery time, min a | 90 (7–950) | 103 (40–900) | 0.001 |

| Stemmed implants, % | 1 | 1.6 | |

| No. of procedures in time period: | 0.001 | ||

| 1994–1999 | 2,648 | 266 | |

| 2000–2005 | 8,540 | 524 | |

| 2006–2013 | 19,889 | 609 |

aMedian (range).

The 2 groups were compared for survivorship using Cox regression adjusted for age, sex, duration of surgery, time period of surgery, and relative risk (RR) estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Statistics

Survival analyses were performed with any revision of the implant as endpoint. The survival times of unrevised implants were censored at the last date of observation or at the time of death or emigration. The Kaplan-Meier method was used for estimation of survival probabilities for the prostheses, with 95% CIs.

To evaluate the impact of a previous HTO on prosthesis survival, we used the Cox regression model to calculate hazard rate ratios (HRs) to estimate the relative risk (RR) of revision. These are represented with 95% CIs and p-value relative to the knee arthroplasties without previous HTO. All p-values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Adjustments were made for age, sex, duration of surgery, and time period of surgery. The specific variables were chosen based on previous studies and clinical experience. Age was divided into 5 groups (< 50, 51–60, 61–70, 71–80, and > 80), surgery time was divided into 4 groups (< 30 min, 30–60 min, 61–90 min, and > 90 min), and 3 time periods were defined (1994–1999, 2000–2004, and 2005–2013). Adjusted Cox regression survival curves were constructed.

The inclusion of bilateral knee arthroplasty can be a violation of the assumption of independent observations in survival analyses, but studies have shown that the effect is minor regarding statistical precision for survival analysis of knee replacements (Robertsson and Ranstam 2003). In this study, 19% of procedures were bilateral.

The reason for revision was also analyzed, with comparison of the 2 groups. In Table 3, the reasons for revision are hierarchical from top to bottom. When more than 1 reason for revision was reported, the top reason in the hierarchy was used as endpoint in the analysis. We used Pearson chi-square test to test whether proportions of specific causes of revision differed in the 2 groups in a material restricted to revised implants.

Table 3.

Reasons for revision

| TKA alone n (%) | TKA after HTO n (%) | p-value | |

| Infection | 289 (21) | 10 (12) | 0.1 |

| Loosening/PE wear | 395 (28) | 29 (35) | 0.2 |

| Dislocation | 275 (20) | 19 (23) | 0.5 |

| Pain only | 90 (6) | 9 (11) | 0.2 |

| Other/progression of OA | 338 (25) | 16 (19) | 0.3 |

| Total | 1387 (100) | 83 (100) |

Fine and Grey analyses, including death as a competing risk, were applied and provided similar estimates to those in the Cox regression analysis (Table 2). We performed sub-analyses of complication rates, and they are referred to in the Results section.

Table 2.

Cox regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, duration of surgery, and time period of surgery

| No. of TKAs | No. of revisions | 10-year survivala (95% CI) | Adjusted RRb (95% CI) | p-value | |

| TKA alone | 31,077 | 1,387 | 93.8 (93.4–94.2) | 1 (ref) | |

| TKA after HTO | 1,399 | 83 | 92.6 (91.0–94.2) | 0.97 (0.77–1.21) | 0.8 |

aKaplan-Meier estimated cumulative survival at 10 years, %.

bRelative risk

The proportional hazards assumption of the Cox model was tested based on scaled Schoenfeld residuals (Grambsch et al. 1995), and was found to be fulfilled for the factor previous osteotomy (p = 0.8).

We used SPSS version 22.0 and R software version 3.1.1.

Results

Demographics

The proportion of women was 68% in the primary TKA group (sex ratio 2.1 to 1) and 51% in the TKA-post-HTO group (sex ratio 1.1 to 1). The mean age for the primary TKA group was 71 (28–101) years and the mean age for the TKA-post-HTO group was 69 (41–93) years. The age distribution was similar for the 2 groups, examining 5 different age categories.

Analyzing NAR data in the 3 time periods from 1994, TKA after HTO was a more frequent procedure in the period1994–1999 (9%) than in the periods 2000–2004 (6%) and 2005–2012 (3%), relative to the total number of arthroplasties (Table 1).

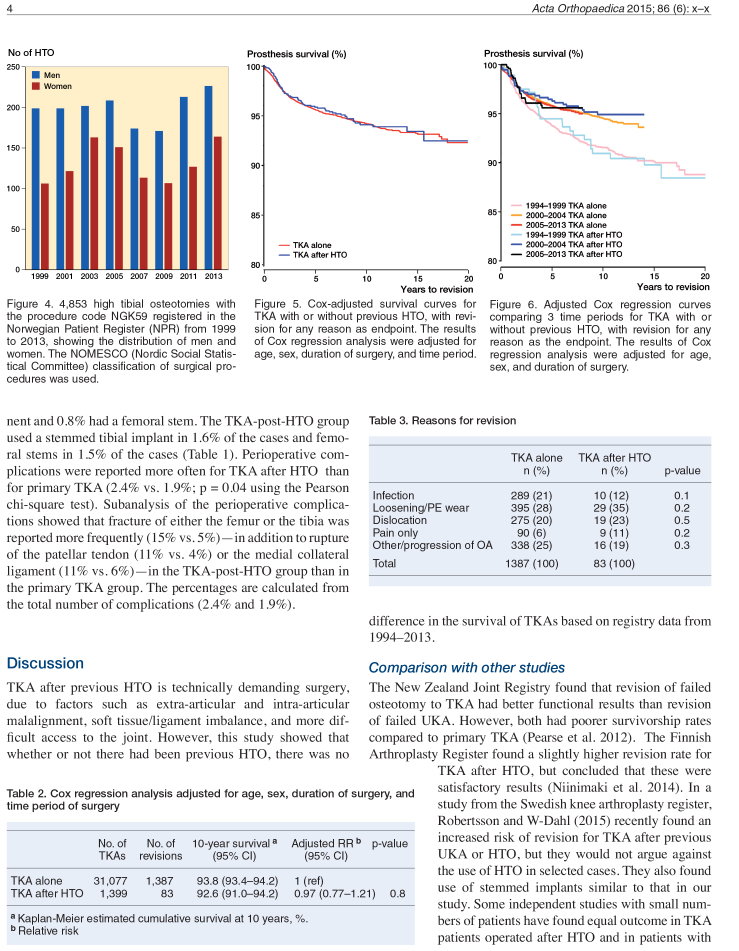

According to the Norwegian Patient Register (NPR), the number of HTO procedures in the period 1999–2013 was 4,853. The annual procedure volume had a range of 278–406 (mean 324 annually), varying every year, with a slight increase in the last 3 years. There were 2,933 men and 1,920 women (ratio 1.5 to 1) (Figure 4). The age distribution for HTOs was 1,632 patients < 40 years of age, 2,436 patients in the age group 40–60, and 785 patients > 60 years of age.

Figure 4.

4,853 high tibial osteotomies with the procedure code NGK59 registered in the Norwegian Patient Register (NPR) from 1999 to 2013, showing the distribution of men and women. The NOMESCO (Nordic Social Statistical Committee) classification of surgical procedures was used.

Revision rate

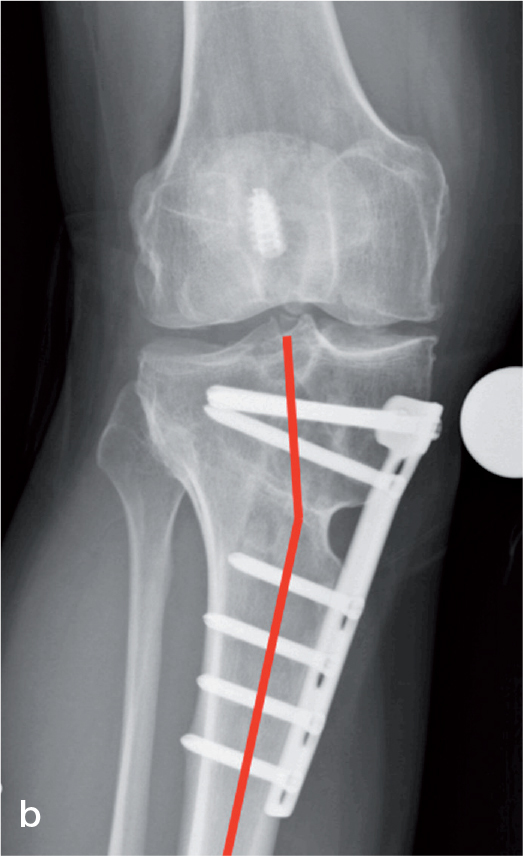

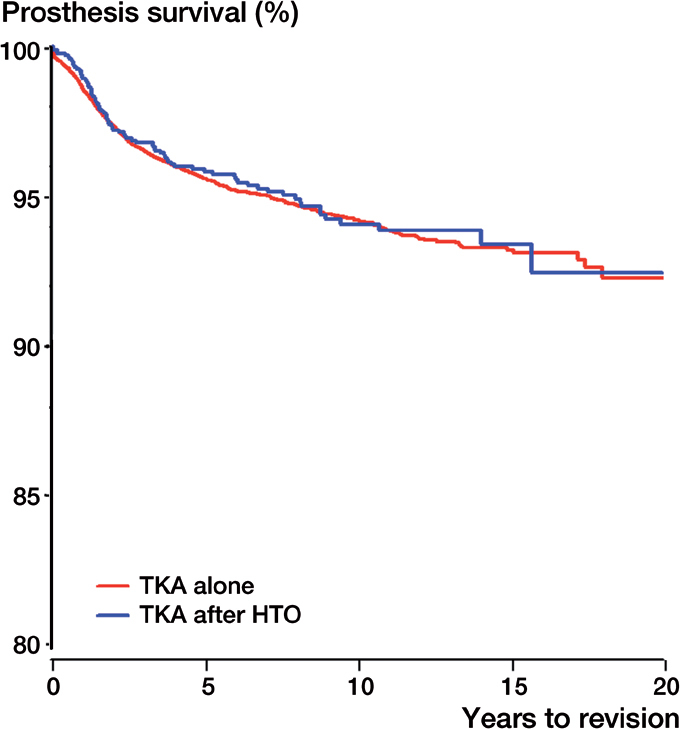

Altogether, the adjusted survival analyses did not show any statistically significant difference between the 2 groups (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Cox-adjusted survival curves for TKA with or without previous HTO, with revision for any reason as endpoint. The results of Cox regression analysis were adjusted for age, sex, duration of surgery, and time period.

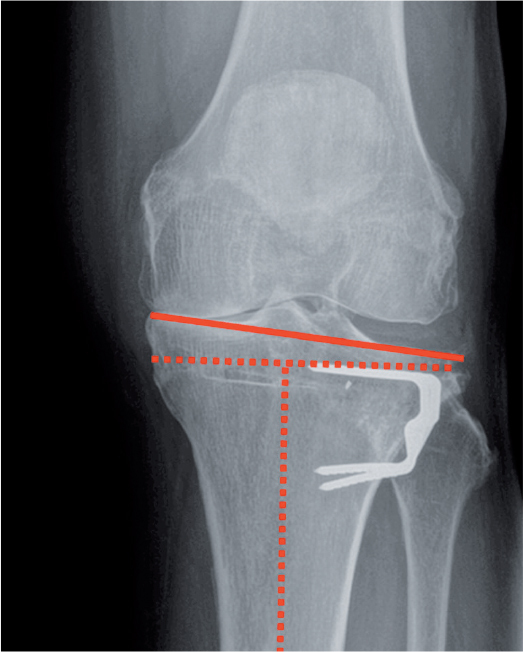

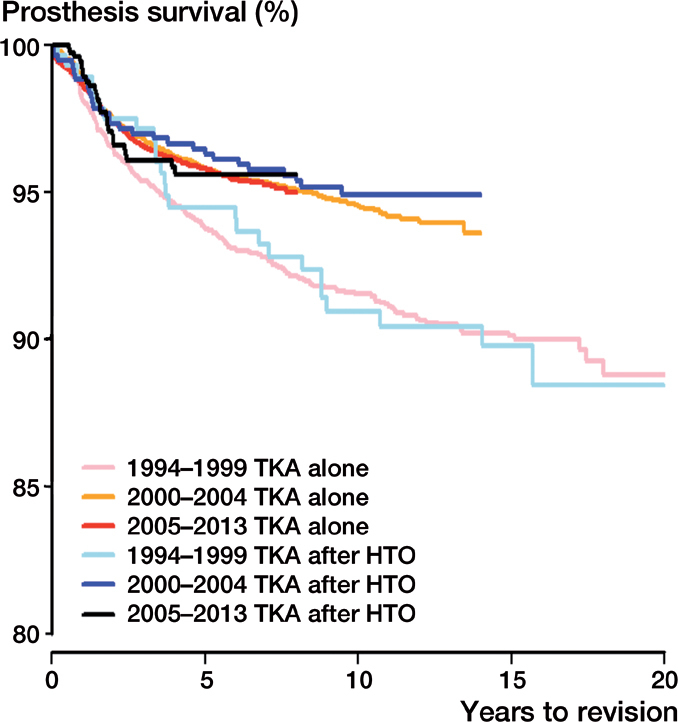

The adjusted Cox regression curves comparing the 3 time periods for primary TKA vs. TKA after HTO showed an improvement over time in both groups, as has been described previously for TKA in another study (Badawy et al. 2013) (Figure 6). The TKA-post-HTO group showed inferior survival results for the 2 latest time periods, whereas this group had better survival than the primary TKA group in the first time period.

Figure 6.

Adjusted Cox regression curves comparing 3 time periods for TKA with or without previous HTO, with revision for any reason as the endpoint. The results of Cox regression analysis were adjusted for age, sex, and duration of surgery.

The Kaplan-Meier 10-year survival analyses did not show any statistically significant difference between the revision rates for the 2 groups. The primary TKA group had a 10-year survival of 93.8% and the TKA-post-HTO group had a 10-year survival of 92.6%. The TKA-post-HTO group had an RR of 0.97 (CI: 0.77–1.21; p = 0.8) in comparison to the primary TKA group as reference (with RR = 1). The analysis included Fine and Grey analyses, taking into account the different proportions of dead patients, with estimates similar to those of the Cox analysis (Table 2).

Reasons for revision

The most common reasons for revision in both groups were aseptic loosening of the distal and/or proximal component, instability, deep infection, and pain. There were no statistically significant differences in the distribution of the causes of revision, comparing the 2 groups (Table 3).

Surgical complexity

The mean duration of surgery for the primary TKA group was 90 min, whereas the mean duration of surgery for the TKA-post-HTO group was 103 min (p = 0.001). 1% of the patients in the primary TKA group required a stemmed tibial component and 0.8% had a femoral stem. The TKA-post-HTO group used a stemmed tibial implant in 1.6% of the cases and femoral stems in 1.5% of the cases (Table 1). Perioperative complications were reported more often for TKA after HTO than for primary TKA (2.4% vs. 1.9%; p = 0.04 using the Pearson chi-square test). Subanalysis of the perioperative complications showed that fracture of either the femur or the tibia was reported more frequently (15% vs. 5%)—in addition to rupture of the patellar tendon (11% vs. 4%) or the medial collateral ligament (11% vs. 6%)—in the TKA-post-HTO group than in the primary TKA group. The percentages are calculated from the total number of complications (2.4% and 1.9%).

Discussion

TKA after previous HTO is technically demanding surgery, due to factors such as extra-articular and intra-articular malalignment, soft tissue/ligament imbalance, and more difficult access to the joint. However, this study showed that whether or not there had been previous HTO, there was no difference in the survival of TKAs based on registry data from 1994–2013.

Comparison with other studies

The New Zealand Joint Registry found that revision of failed osteotomy to TKA had better functional results than revision of failed UKA. However, both had poorer survivorship rates compared to primary TKA (Pearse et al. 2012). The Finnish Arthroplasty Register found a slightly higher revision rate for TKA after HTO, but concluded that these were satisfactory results (Niinimaki et al. 2014). In a study from the Swedish knee arthroplasty register, Robertsson and W-Dahl (2015) recently found an increased risk of revision for TKA after previous UKA or HTO, but they would not argue against the use of HTO in selected cases. They also found use of stemmed implants similar to that in our study. Some independent studies with small numbers of patients have found equal outcome in TKA patients operated after HTO and in patients with a primary TKA regarding functional outcome and survival (Meding et al. 2000), or functional measures only (Treuter et al. 2012), whereas other studies have indicated more failures with higher reoperation rates (Parvizi et al. 2004, Haslam et al. 2007).

Explanations and mechanisms

The 10-year survival rate was practically the same for the primary TKA group (93.8%) and the TKA-post-HTO group (92.6%). One would expect a higher risk of revisions in the post-HTO group, not only because of the more technically challenging procedure but also because the post-HTO patients were younger and had a higher proportion of males than the primary TKA group. It is possible that most of the post-HTO patients had been taken care of by more experienced surgeons, due to anticipation of technical challenges. Our finding of a longer duration of surgery in the TKA-post-HTO group might be explained by the surgery being more technically demanding, and/or that removal of the osteotomy implants took time.

Perioperative complications were reported to the registry more frequently in TKA after HTO, with fractures and ligament injuries being most commonly reported. We have data on HTO from the NPR from 1999 onwards. These data showed that more men than women have been treated with an HTO for osteoarthritis (ratio: 1.5 to 1). Bellemans et al. (2012) found constitutional varus in 32% of men and in 17% of women, and constitutional varus was associated with increased sports activities during growth; this suggests that men are more often candidates for valgus producing osteotomy. In the present study, the number of women converted to a TKA later was similar to the number of men (51% vs. 49%). This might suggest that there is better survival of the HTO procedure in male patients. In Norway, the number of tibial osteotomies has been stable since 1999, with a slight increase in the last 3 years, whereas the number of TKAs has increased substantially.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of our study was the large database of the NAR with a high completeness of registration (Espehaug et al. 2006, NAR 2014), enabling exclusions and adjustments for confounding factors.

The main limitation of our study was the lack of information on surgical experience and surgical technique used for osteotomy. However, a study from Preston et al. (2014) showed no differences between lateral and medial osteotomy approaches regarding functional outcomes or survivorship of TKA.

We also lacked the information given by patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) data regarding pain and function before and after surgery. PROMs could have supplied information on whether satisfaction was different in the 2 groups.

We chose to include TKA without patellar component, as this is the standard method in Norway. However, there tended to be more frequent use of patellar components in TKA with previous HTO than in primary TKA (12% vs. 8%). This is probably due to the occurrence of patella infera, tibial slope changes, or patellofemoral malalignment leading to secondary patellofemoral osteoarthritis in some cases after HTO. However, we found equal rates of revision with insertion of patellar component only in the 2 groups.

Selection and information bias must always be considered in registry studies. However, the completeness of registration with a minimal dataset has been validated in registries, as has the accuracy of data (Espehaug et al. 2006, SKAR 2013). The information on HTO prior to TKA has not been validated.

Possible implications and future research

The systematic review by van Raaij et al. (2009) on total knee arthroplasty after HTO concluded that there was a need for knee arthroplasty registry data or high-quality, observational multicenter studies to produce larger numbers and possibly generate higher quality of evidence to reach more solid conclusions. Our registry-based study containing 1,860 TKAs after HTO provided evidence to support the conclusion that they give results similar to those with primary TKA concerning revision rates. PROM data would add interesting information on whether patient satisfaction is similar in the 2 groups. The anonymous data obtained from the NPR could not give certain information on survival after HTO before a secondary procedure with TKA, due to lack of information on which side the surgery was performed. This could be linked to the NAR in a future study identifying particular patients.

Conclusion

In this registry-based study, previous high tibial osteotomy did not appear to increase the risk of revision after a secondary procedure with total knee arthroplasty.

Acknowledgments

MB, AMF, and OF designed the study. MB, AMF, LIH, and OF collected and analyzed the data. MB wrote the manuscript, which was edited by all the authors.

There was no external funding and there were no competing interests. The NAR is financed by the Regional Health Board of Western Norway. We thank the Norwegian orthopedic surgeons for excellent reporting to the NAR.

References

- Badawy M, Espehaug B, Indrekvam K, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI, Furnes O. Influence of hospital volume on revision rate after total knee arthroplasty with cement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 95(18): e131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellemans J, Colyn W, Vandenneucker H, Victor J. The Chitranjan Ranawat award: is nneutral mechanical alignment normal for all patients? The concept of constitutional varus. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012; 470(1): 45-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efe T, Ahmed G, Heyse TJ, Boudriot U, Timmesfeld N, Fuchs-Winkelmann S, et al. Closing-wedge high tibial osteotomy: survival and risk factor analysis at long-term follow up. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011; 12: 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espehaug B, Furnes O, Havelin LI, Engesaeter LB, Vollset SE, Kindseth O. Registration completeness in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2006; 77(1): 49-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farfalli LA, Farfalli GL, Aponte-Tinao LA. Complications in total knee arthroplasty after high tibial osteotomy. Orthopedics 2012; 35(4): e464-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnes O, Espehaug B, Lie SA, Vollset SE, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI. Early failures among 7,174 primary total knee replacements: a follow-up study from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1994-2000. Acta Orthop Scand 2002; 73(2): 117-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grambsch PM, Therneau TM, Fleming T R . Diagnostic plots to reveal functional form for covariates in mulitiplicative intensity models. Biometrics 1995; 51 (4): 1469-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam P, Armstrong M, Geutjens G, Wilton TJ. Total knee arthroplasty after failed high tibial osteotomy long-term follow-up of matched groups. J Arthroplasty 2007; 22(2): 245-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meding JB, Keating EM, Ritter MA, Faris PM. Total knee arthroplasty after high tibial osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2000; (375): 175-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAR The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Annual report 2014. nrlhelse.ihelse.net

- Naudie D, Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH, Bourne TJ. The Install Award. Survivorship of the high tibial valgus osteotomy. A 10- to -22-year followup study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999; (367): 18-27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niinimaki T, Eskelinen A, Ohtonen P, Puhto AP, Mann BS, Leppilahti J. Total knee arthroplasty after high tibial osteotomy: a registry-based case-control study of 1,036 knees. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2014; 134(1): 73-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvizi J, Hanssen AD, Spangehl MJ. Total knee arthroplasty following proximal tibial osteotomy: risk factors for failure. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004; 86-a(3): 474-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearse AJ, Hooper GJ, Rothwell AG, Frampton C. Osteotomy and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty converted to total knee arthroplasty: data from the New Zealand Joint Registry. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27(10): 1827-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston S, Howard J, Naudie D, Somerville L, McAuley J. Total knee arthroplasty after high tibial osteotomy: no differences between medial and lateral osteotomy approaches. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472(1): 105-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O, Ranstam J. No bias of ignored bilaterality when analysing the revision risk of knee prostheses: analysis of a population based sample of 44,590 patients with 55,298 knee prostheses from the national Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2003; 4: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O, W-Dahl A. The risk of revision after TKA is affected by previous HTO or UKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015; 473(1): 90-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seil R, van Heerwaarden R, Lobenhoffer P, Kohn D. The rapid evolution of knee osteotomies. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013; 21(1): 1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SKAR Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register. Annual report 2013. www.knee.se

- Smith JO, Wilson AJ, Thomas NP. Osteotomy around the knee: evolution, principles and results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013; 21(1): 3-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treuter S, Schuh A, Honle W, Ismail MS, Chirag TN, Fujak A. Long-term results of total knee arthroplasty following high tibial osteotomy according to Wagner. Int Orthop 2012; 36(4): 761-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Raaij T, Reijman M, Brouwer RW, Jakma TS, Verhaar JN. Survival of closing-wedge high tibial osteotomy: good outcome in men with low-grade osteoarthritis after 10-16 years. Acta Orthop 2008; 79(2): 230-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Raaij TM, Reijman M, Furlan AD, Verhaar JA. Total knee arthroplasty after high tibial osteotomy. A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2009; 10: 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- W-Dahl A, Robertsson O, Lohmander LS. High tibial osteotomy in Sweden 1998-2007: a population-based study of the use and rate of revision to knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2012; 83(3): 244-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windsor RE, Insall JN, Vince KG. Technical considerations of total knee arthroplasty after proximal tibial osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1988; 70(4): 547-55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]