Abstract

Background and purpose — Cancellous bone appears to heal by mechanisms different from shaft fracture healing. There is a paucity of animal models for fractures in cancellous bone, especially with mechanical evaluation. One proposed model consists of a screw in the proximal tibia of rodents, evaluated by pull-out testing. We evaluated this model in rats by comparing it to the healing of empty drill holes, in order to explain its relevance for fracture healing in cancellous bone. To determine the sensitivity to external influences, we also compared the response to drugs that influence bone healing.

Methods — Mechanical fixation of the screws was measured by pull-out test and related to the density of the new bone formed around similar, but radiolucent, PMMA screws. The pull-out force was also related to the bone density in drill holes at various time points, as measured by microCT.

Results — The initial bone formation was similar in drill holes and around the screw, and appeared to be reflected by the pull-out force. Both models responded similarly to alendronate or teriparatide (PTH). Later, the models became different as the bone that initially filled the drill hole was resorbed to restore the bone marrow cavity, whereas on the implant surface a thin layer of bone remained, making it change gradually from a trauma-related model to an implant fixation model.

Interpretation — The similar initial bone formation in the different models suggests that pull-out testing in the screw model is relevant for assessment of metaphyseal bone healing. The subsequent remodeling would not be of clinical relevance in either model.

Humans most often get fractures in the corticocancellous bone of metaphyses, such as in the distal radius or proximal femur. However, fracture models in experimental animals almost exclusively deal with shaft fractures. This is unfortunate, since shaft and metaphyseal fractures may be different in several important respects. The lack of experimental data regarding metaphyseal fracture healing may be due to practical difficulties, particularly when it comes to mechanical testing.

There are several reasons for expecting metaphyseal fractures to heal in a way that is different from the common description of shaft fracture healing. The metaphyseal bone is often rich in mesenchymal stem cells, in spite of the fact that the marrow may not be hematopoetic (Suh et al. 2012, Siclari et al. 2013). Therefore, recruitment of cells that are able to contribute to new bone formation might be less of a problem than in the shaft, where healing is dependent on the recruitment of cells from distant sources in addition to the periosteum (Kumagai et al. 2008).

There is some evidence that in humans also, healing of metaphyseal fractures is different from healing of shaft fractures, where the classical description involves a cartilaginous phase. In biopsies from distal radial fractures, direct bone formation was found after as little as 1 week, occurring in the marrow compartment, with no obvious connection to trabecular surfaces (Aspenberg and Sandberg 2013). Furthermore, John Charnley—while working with knee arthrodeses in the 1950s (before he started the joint replacement era)—described large biopsies from patients 4 weeks after the operation, showing a thin band of new, woven bone at the resection surfaces, apparently formed in the marrow. He thought that this was derived from trabecular surfaces (Charnley and Baker 1952).

Regarding shaft fractures, there are expectations that various treatments with drugs or other factors can modify the healing process. For example, the negative effects of NSAIDs on shaft fractures are well known. This knowledge is based on a multitude of animal experiments, and on 1 randomized clinical trial (Burd et al. 2003). We now know that metaphyseal fractures respond differently (Sandberg and Aspenberg 2014). Because the latter type of fracture may have a different biology, it is important to have animal models for metaphyseal fractures, with robust, preferably mechanical, outcome measures.

This study was carried out to characterize the morphological and mechanical behavior—and the response to some drugs—of a metaphyseal fracture-healing model designed for mechanical testing.

Methods

Overview

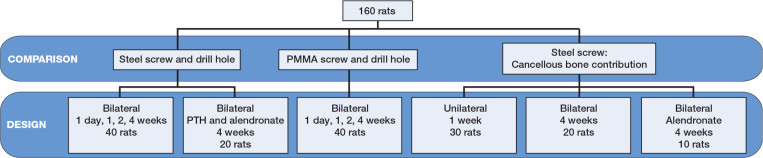

160 male Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing 331 (SD 22) g were used to evaluate 3 different metaphyseal fracture models: an empty drill hole, a drill hole with a stainless steel screw, and a drill hole with a radiolucent PMMA screw. All models were used for time series. The stainless steel screw was used for mechanical pull-out testing. In some groups, this was preceded by unscrewing half a turn, to eliminate osseointegration and thus measure only the strength of the bony threads holding the screw. In other groups, we removed the cancellous bone around the screw, to differentiate the role of the cortex. The screw was then screwed back to its original position before pull-out testing. This was also combined with drugs known to improve implant fixation. The drill hole and the PMMA screws were used for morphometric measurements using microCT. The PMMA screws were similar to the steel screws in both size and shape. Altogether, 16 groups or data sets were analyzed, each of them usually involving 10 rats (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of the experimental groups.

Drill-hole model

For details of anesthesia, surgery, and microCT, see Supplementary data.

A 5- to 8-mm longitudinal incision was made along the tibia, and a hole was drilled by hand, using a 1.2-mm (18G) syringe needle, in the anterio-medial surface of the proximal metaphysis, about 3 mm from the growth plate. The skin was sutured after the procedure.

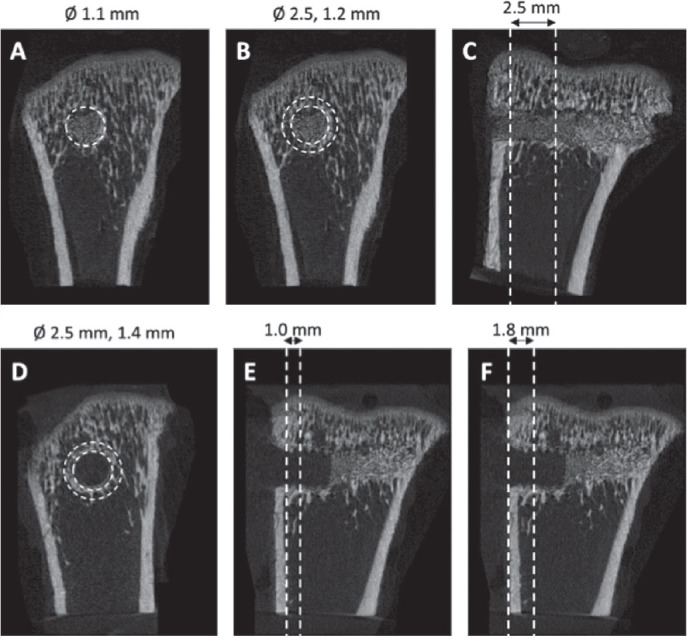

The drill holes were analyzed with microCT. A volume of interest was defined as a cylinder with a diameter of 1.1 mm and a length of 2.5 mm into the bone marrow cavity, starting at the endosteal side of the cortical bone. For measurement of the bone formation surrounding the drill hole, another volume of interest was defined as a cylindrical pipe with an outer diameter of 2.5 mm, an inner diameter of 1.2 mm, and a length of 2.5 mm (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Regions of interest for microCT analyses of drill holes and PMMA screws. 4 volumes of interest were defined. A) For the drill hole: a cylinder with a diameter of 1.1 mm and 2.5 mm in length. B and C) For the bone adjacent to the drill hole: a cylinder pipe with an outer diameter of 2.5 mm and inner diameter of 1.2 mm, extending from the cortex 2.5 mm into the marrow cavity. D and E) For measuring the bone formation surrounding the screw: a cylinder pipe with an outer diameter of 2.5 mm, inner diameter of 1.4 mm, extending from the cortex 1.0 mm into the marrow cavity. F) For measuring the tissue mineral density (TMD) surrounding the screw a longer cylinder, 1.8 mm in length, was defined including the cortical bone.”

Steel screw model

Stainless steel (316L) screws (thread M 1.7) were used. The threaded part of the screw is 2.8 mm long. The screws were custom-made and fitted with a head that enabled them to be mounted in a materials testing machine.

Surgery was carried out as described above, but the steel screw was screwed into the drill hole before the skin was sutured.

After the rats were killed (with CO2 after sedation with isoflurane), the tibiae were harvested and the pull-out force of the screw was measured using a materials testing machine (100 R; DDL Inc., Eden Prairie, MN). The tibiae were mounted so that the head of the screw projected through a hole in a metal plate. The screw head was fixed in a connector and the screw was pulled out at a speed of 0.1 mm/s. The maximal force during the pull-out was considered to be the pull-out force. All measurements were performed with the examiner blind regarding treatment.

PMMA screw model

Surgery was carried out as described above, but a PMMA screw, similar to the steel screws in size and shape, was screwed into the drill hole before the skin was sutured.

The bone formation surrounding the PMMA screws was analyzed with microCT. Scanning and reconstruction were carried out with settings as given above. A volume of interest was defined as a cylindrical pipe with an outer diameter of 2.5 mm, an inner diameter of 1.4 mm around the screw, and a length of 1.0 mm into the bone marrow cavity, starting at the endosteal side of the cortical bone. Another volume of interest was defined as a cylindrical pipe with an outer diameter of 2.5 mm, an inner diameter of 1.4 mm around the screw, and a length of 1.8 mm into the bone marrow cavity, starting from the bottom of the screw head, thus including the cortex (Figure 2).

PTH and alendronate treatment

Rats included in the drug-treatment groups received subcutaneous injections of either PTH (10 µg/kg), alendronate (20 µg/kg), or saline 6 days a week.

Statistics

This was a descriptive analysis, and no hypothesis was specified in advance, except the notion that there would be similarities between the models. We therefore refrained from formulating and testing hypotheses in retrospect, and thus present no p-values. Confidence intervals for differences between means are given at the 95% level.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee for Animal Experiments, and the animals were treated according to the institutional guidelines for care and treatment of laboratory animals (entry no. 55-12).

Results

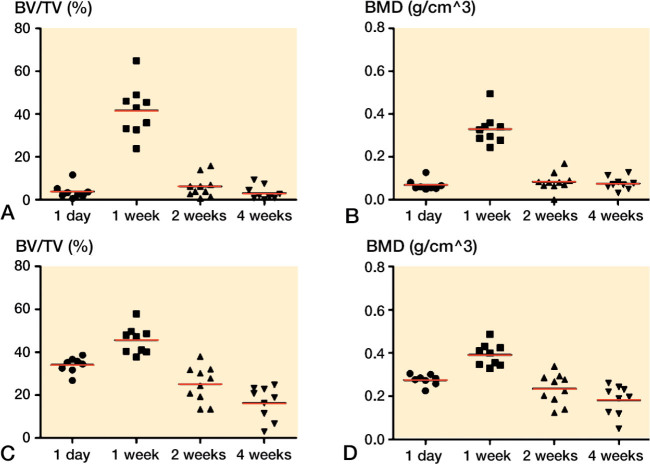

Drill holes quickly fill with bone, and then lose it

The empty drill holes were already filled with new bone after 1 week. After 2 weeks, this bone was mostly gone. The bone surrounding the drill hole increased in density during the first week and then declined to the level at day 1 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

MicroCT data from former drill hole in metaphyseal tibia. New bone was formed in the drill holes during the first week (panels A, B) and then gradually disappeared. The bone density surrounding the drill holes also increased during the first week before it decreased (C, D).

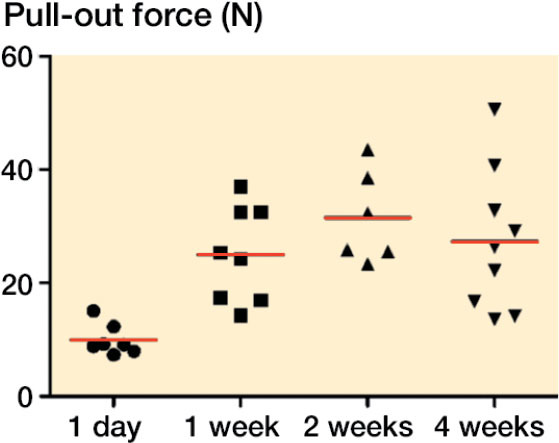

Steel screws quickly improve in fixation, which is then maintained

The strength of the bone surrounding the screws, as measured by pull-out force, more than doubled during the first week (an increase of 140%, 95% CI: 78–201). There was then a trend towards further increase during week 2 (Figure 4). From 2 to 4 weeks, there was no clear change. Some previous studies have shown a further increase (Wermelin et al. 2007), but others have not (Agholme et al. 2011).

Figure 4.

Pull-out force for metaphyseal screws. The force increased gradually during the first 2 weeks. From 2 to 4 weeks, there was no clear change.

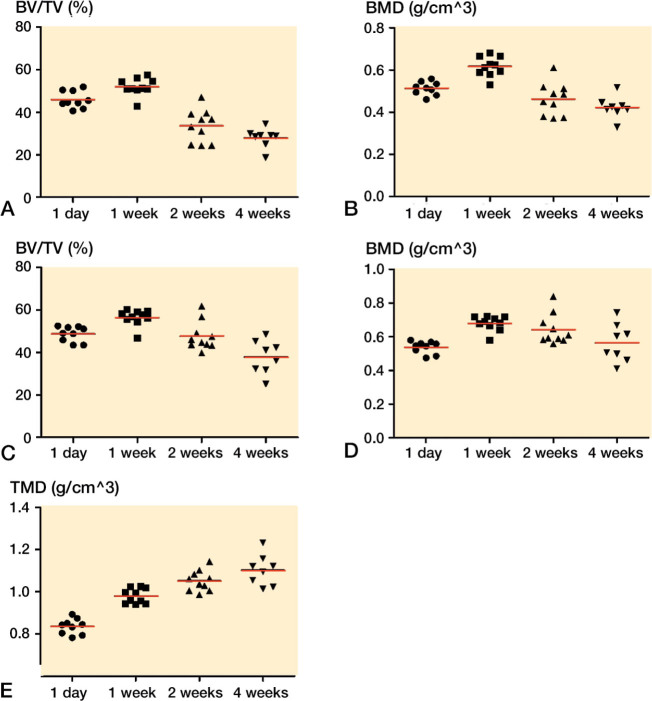

Bone density around PMMA screws suggests improved bone quality over time

The bone density surrounding the screws in the marrow compartment, measured as BV/TV, increased by 15% (95% CI: 6–24) during the first week, and then declined to the level at day 1. The changes were small. In contrast, the density of the volume of interest, including the cortex, defined as bone by a threshold value (TMD), continued to increase up to 4 weeks (analyzed versus log-time, r2 = 0.76, p < 0.001; Figure 5). This suggests that the density of the existing bone increased over time similar to the pull-out force, indicating that pull-out force may reflect bone quality more than volume.

Figure 5.

MicroCT data from PMMA screws in metaphyseal tibia. Bone volume (BV/TV) and bone density (BMD) around the screws, cortex excluded, increased during the first week and then declined (panels A, B). Bone formation, including cortex, around the screws increased during the first week, and then declined (C, D). Tissue mineral density (TMD), cortex included, continued to increase up to 4 weeks (E).

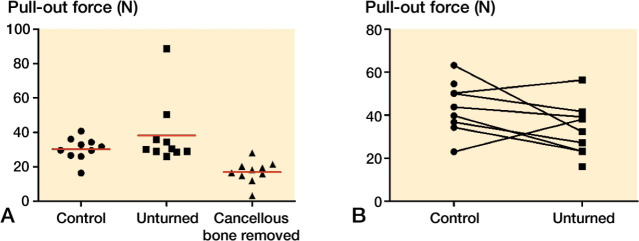

Cancellous bone provided half of the screw pull-out resistance at 1 week

30 rats received a steel screw, which was implanted for 1 week. The rats were randomly allocated to 3 groups: the screw was either untouched, unscrewed half a turn and screwed back, or had the cancellous bone around it removed before testing. For removal of cancellous bone, the tibia was opened from the side opposite the screw, and the screw loosened until the tip was in the cortex. The cancellous bone was then removed and the screw returned to its original position. Unscrewing could not be shown to reduce the pull-out force suggesting that direct contact between implant and bone (osseointegration) does not contribute substantially to the pull-out force. Removal of the cancellous bone reduced the pull-out force by 44% (95% CI: 24-65) (Figure 6). Cancellous bone obviously contributes to a large part of the pull-out resistance. This contribution is probably greater than the 44% measured, because—for technical reasons—we could not remove the cancellous bone very close to the cortex.

Figure 6.

Pull-out force for metaphyseal screws, 1 week (panel A) and 4 weeks (B) after insertion. Unskrewing of the screw had no important effect on the pull-out force compared to controls, either at 1 week or at 4 weeks. Removal of the cancellous bone reduced the pull-out force compared to leaving the cancellous bone intact after unscrewing.

Cancellous bone provided no important pull-out resistance at 4 weeks

10 rats received bilateral steel screws, which were implanted for 4 weeks. On one side, chosen randomly for each rat, the screw was unscrewed by half a turn to loosen any possible osseointegration, and then turned back to its original position. Both screws were then subjected to pull-out testing, which showed that the unskrewing reduced the pull-out force by 25% (95% CI: −3 to 52) (Figure 6).

10 rats received bilateral steel screws, which were implanted for 4 weeks. Both sides underwent unscrewing as above before testing, but on one side the cancellous bone was removed as described above. Removal of the cancellous bone reduced the pull-out force by 19% (95% CI: −17 to 55) (Figure 7, see Supplementary data).

Alendronate increased the pull-out resistance at 4 weeks by adding cancellous bone

We then investigated whether a drug treatment that has been previously shown to increase the pull-out force at 4 weeks does so through effects on cancellous bone. 10 rats received bilateral steel screws, implanted for 4 weeks. These rats received alendronate as above. Both sides underwent unscrewing as above before testing, but on one side the cancellous bone was removed. Removal of the cancellous bone reduced the pull-out force by 37% (95% CI: 18–57) (Figure 7, see Supplementary data). Because the cancellous bone showed no substantial contribution to the pull-out force at 4 weeks without drug treatment, but did so with alendronate, it appears that the positive effect of alendronate is to a large extent due to increased amounts of cancellous bone.

Alendronate and PTH preserved the new bone in drill holes and around screws

At 4 weeks, PTH and alendronate roughly doubled the pull-out force for the screws. For PTH, the increase was 160% (95% CI: 111–213) and for alendronate the increase was 220% (95% CI: 183–56). Similarly, both PTH and alendronate increased the amount of bone in and around the empty drill hole (Figure 7, see Supplementary data).

Exclusions

Of the 100 microCT specimens, 3 were excluded due to placement in the epiphysis and 4 were excluded due to placement in the cortex.

Of the 90 pull-out tests, 2 were excluded due to misplacement of the screws and 6 were excluded because they loosened before the pull-out test.

Discussion

We found that the initial bone-formation response to metaphyseal trauma by drilling a hole in the rat tibia is consistent, and can be evaluated either by morphological methods or by pull-out testing of a screw inserted in the hole. There was a rapid bone-formation response already in the first week, which was similar in both the hole model and the screw model, leading to a rapid increase in pull-out resistance. Thereafter, the 2 models developed differently. In both models, bone resorption followed: the bone in the empty holes left space for a marrow cavity, whereas a thin bony sheath remained around the screws after 2 weeks.

Concerning the screws at 1 week, the bone in the marrow compartment contributed with at least half of the pull-out resistance, but without pharmacological treatment its contribution almost disappeared after a few more weeks. Still, the strong pull-out resistance remained. This may be partly because the new-formed cancellous bone had been remodeled to become indistinguishable from an endosteal cortical thickening, but also because of an improved mechanical property of the remaining bone in the marrow compartment, reflected by the increased total mineral content. In contrast, rats treated with an anabolic drug or an anti-catabolic drug showed greatly increased amounts of bone in the cancellous compartment. The pull-out resistance had increased further from the first week, largely because of this cancellous response.

Before discussing the relevance of these models for fracture healing in cancellous bone, one must define fracture healing in this context. The common teaching on fracture healing lists a series of interrelated events that follow on from a shaft fracture, stable or unstable (Reikerås 1990, Einhorn and Gerstenfeld 2014). As mentioned in the introduction, much of this may be irrelevant for fractures in cancellous bone, judging by the histological differences (Aspenberg and Sandberg 2013). After the initial events, when the fragments are united by primitive bone, remodeling may also have different consequences in cortical and cancellous bone. Shaft fracture remodeling tends to replace the woven, cancellous bone that is initially formed with new cortex. Remodeling in cancellous bone may in part restore the marrow cavity, so that the load-bearing function of the bone in the marrow compartment is gradually taken over by the surrounding cortex (which may heal more slowly), or by a few stronger trabeculae. This load-dependent process is probably dependent on site, shape, and loading—and therefore difficult to mimic in an animal model that could allow generalization. Moreover, when a sufficient amount of cancellous primitive bone has formed, a metaphyseal fracture is likely to be stable and pain-free. In the clinic, a patient would then be considered to be clinically healed, although not by conventional radiological criteria (Aspenberg and Johansson 2010).

After the initial bone formation has provided sufficient strength, remodeling will adapt the site according to mechanical or other demands. This will optimize the bone architecture further, but from a patient standpoint this remodeling process is less interesting. Thus, we believe that in metaphyseal fracture models the first healing phase is of prime interest. In rats, our data suggest that this corresponds to the first week.

The screw model gives meaningful information from longer follow-up than the first week, especially with regard to drug treatment with bisphosphonates, PTH, and various drugs that interfere with Wnt signaling (Skripitz and Aspenberg 2001, Wermelin et al. 2008, Agholme et al. 2014). These results are obviously relevant for implant fixation, but as with fracture healing, implant fixation is a somewhat ambiguous term. The literature is rather focused on osseointegration, meaning a bond—at some level—between implant and bone. The common way of measuring osseointegration of dental screws is to measure torque resistance, which includes friction due to surface irregularities (Javed and Romanos 2010). However, implanted screws are almost never loaded by torque in vivo. Because we found only minimal differences between pull-out forces before and after breaking any possible bonds by loosening (uscrewing) of the screw in our model, we believe that osseointegration is not much involved in its fixation, especially as the screws were made of stainless steel, and not titanium. Rather, the model appears to measure the strength of the bony threads that form after screw insertion, both in the cortex and in the marrow compartment.

The thin bony sheath around the screw within the marrow compartment is probably caused by surface phenomena. Mechanical loading could be part of this, since steel is stiffer than cancellous bone, and this could conceivably lead to stress concentration at the surface. However, we have also seen a similar sheath around softer implants such as birch wood, suggesting that there are causes other than mechanical ones (Aspenberg 2014). It would be interesting to systematically compare screws with different degrees of stiffness.

Another model that allows mechanical evaluation of metaphyseal fracture healing uses a locking plate to create a stable osteotomy in the distal metaphysis of mouse femurs (Histing et al. 2012). Healing was mostly free from cartilage in this model, but there is a considerable external callus. In a metaphyseal fracture model in rabbits, a histological pattern different from shaft healing, was described (Chen et al. 2015). This pattern is similar to metaphyseal healing in the clinic (Aspenberg and Sandberg 2013), although cartilage may also be formed in metaphyseal fractures under unstable conditions (Claes et al. 2011). The metaphyseal plate model in mice allows evaluation of torsional stiffness, which was found to double between weeks 2 and 5 (Histing et al. 2012). This indicates a slower degree of healing than we have seen in mouse shaft models, where the peak force at failure is reached after about 2–3 weeks (Sandberg and Aspenberg 2014). This difference is unexplained. However, the plating paper reported stiffness, but not torque at failure (Histing et al. 2012). In our pull-out model, force at failure and stiffness correlate reasonably well (r2 = 0.5 for all, and r2 = 0.8 for 4 weeks, cancellous contribution experiments not included) but for many years we have chosen to consistently use force at failure as the principal outcome measure.

It must be noted that metaphyseal fractures always include cortical bone, and that a strict division between cortical and cancellous healing is not possible in the clinic.

Drug effects are strong in the screw model after the first week, leading to more cancellous bone (Wermelin et al. 2007, Skripitz et al. 2000). This appeared to be an effect exerted on the bone-formation response to trauma, as there were minimal effects on non-traumatized bone.

In conclusion, it appears that both the drill-hole model and the screw pull-out model reflect a fracture-healing response during the first week. The remodeling that ensues after that week tends to drive the models in different directions, so that the drill-hole model recreates a marrow cavity, and the screw model tends to favor the maintenance of the new-formed bone around it, possibly due to surface phenomena.

Supplementary data

For details of anesthesia, surgery, and microCT, and for Figure 7, see Supplementary data on the Acta Orthopaedica website at www.actaorthop.org, identification number 8727.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

PA, MB, and OS planned the study. MB and OS conducted the experiments. PA, MB, and OS did the data analysis. MB wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

This study was supported by the Swedish Research Council (2031-47-5), AFA insurance company, the EU Seventh Framework program (FP7/2007-2013, grant 279239), and a specific grant from Linköping University.

PA has shares in Addbio AB, and has received institutional research support from Eli Lilly and Company. The other authors have no competing interests.

References

- Agholme F, Isaksson H, Kuhstoss S, Aspenberg P. The effects of dickkopf-1 antibody on metaphyseal bone and implant fixation under different loading conditions. Bone 2011; 48(5): 988–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agholme F, Macias B, Hamang M, Lucchesi J, Adrian MD, Kuhstoss S, et al. . Efficacy of a sclerostin antibody compared to a low dose of PTH on metaphyseal bone healing. J Orthop Res 2014; 32(3): 471–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspenberg P. Alendronate-eluting polyglucose-lignol composite (POGLICO). Acta Orthop 2014; 85(6): 687–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspenberg P, Johansson T. Teriparatide improves early callus formation in distal radial fractures. Acta Orthop 2010; 81(4): 508–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspenberg P, Sandberg O. Distal radial fractures heal by direct woven bone formation. Acta Orthop 2013; 84(3): 297–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burd TA, Hughes MS, Anglen JO. Heterotopic ossification prophylaxis with indomethacin increases the risk of long-bone nonunion. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2003; 85(5): 700–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charnley J, Baker SL. Compression arthrodesis of the knee; a clinical and histological study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1952; 34 B(2): 187–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WT, Han DC, Zhang PX, Han N, Kou YH, Yin XF, Jiang BG. A special healing pattern in stable metaphyseal fractures. Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (2): 238–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claes L, Reusch M, Göckelmann M, Ohnmacht M, Wehner T, Amling M, et al. . Metaphyseal fracture healing follows similar biomechanical rules as diaphyseal healing. J Orthop Res 2011; 29(3): 425–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einhorn TA, Gerstenfeld LC. Fracture healing: Mechanisms and interventions. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2014; 11(1): 45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Histing T, Klein M, Stieger A, Stenger D, Steck R, Matthys R, et al. . A new model to analyze metaphyseal bone healing in mice. J Surg Res 2012; 178(2): 715–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javed F, Romanos GE. The role of primary stability for successful immediate loading of dental implants. A literature review. J Dent 2010; 38(8): 612–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai K, Vasanji A, Drazba JA, Butler RS, Muschler GF. Circulating cells with osteogenic potential are physiologically mobilized into the fracture healing site in the parabiotic mice model. J Orthop Res 2008; 26(2): 165–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reikerås O. Healing of osteotomies under different degrees of stability in rats. J Orthop Trauma 1990; 4(2): 175–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg O, Aspenberg P. Different effects of indomethacin on healing of shaft and metaphyseal fractures. Acta Orthop 2014; 86(2): 243–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siclari VA, Zhu J, Akiyama K, Liu F, Zhang X, Chandra A, et al. . Mesenchymal progenitors residing close to the bone surface are functionally distinct from those in the central bone marrow. Bone 2013; 53(2): 575–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skripitz R, Aspenberg P. Early effect of parathyroid hormone (1-34) on implant fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001; (392): 427–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skripitz R, Andreassen TT, Aspenberg P. Strong effect of PTH (1-34) on regenerating bone: A time sequence study in rats. Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71(6): 619–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh KT, Ahn JM, Lee JS, Bae JY, Lee IS, Kim HJ, et al. . MRI of the proximal femur predicts marrow cellularity and the number of mesenchymal stem cells. J Magn Reson Imaging 2012; 35(1): 218–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wermelin K, Tengvall P, Aspenberg P. Surface-bound bisphosphonates enhance screw fixation in rats–increasing effect up to 8 weeks after insertion. Acta Orthop 2007; 78(3): 385–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wermelin K, Suska F, Tengvall P, Thomsen P, Aspenberg P. Stainless steel screws coated with bisphosphonates gave stronger fixation and more surrounding bone. Histomorphometry in rats. Bone 2008; 42(2): 365–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.