Abstract

Background:

Periodic drug shortages have become a reality in clinical practice. In 2010, in the context of a nationwide drug shortage, our hospital experienced an abrupt 3-month shortage of the surgical anesthetic propofol. The purpose of this retrospective study was to survey the clinical impact of the abrupt propofol shortage at our hospital and to survey for any change in perioperative mortality.

Methods:

A retrospective before-and-after analysis, comparing May through July 2010 (group A, prior to the propofol shortage) to August through October 2010 (group B, during the propofol shortage).

Results:

In May through July 2010, before the propofol shortage, a majority of patients (80%) received propofol (group A, n = 2,830). In August through October 2010, during the propofol shortage, a majority of patients (81%) received etomidate (group B, n = 3,066). We observed that net usage of etomidate increased by more than 600% in our hospital. Baseline health characteristics and type of surgery were similar between groups A and B. Thirty-day and 2-year mortality were similar between groups A and B. The reported causes and frequency of mortality in groups A and B were also similar.

Conclusion:

The propofol shortage led to an increased usage of etomidate by more than 600%. In spite of that, we did not detect an increase in mortality associated with the increased use of etomidate during a 3-month propofol shortage.

Keywords: drug shortage; etomidate; induction of anesthesia; intravenous anesthetics, propofol

Drug shortages have become increasingly common in the United States. The underlying economic, regulatory, and manufacturing forces that lead to drug shortages are complex.1,2 In mid 2010, there was a nationwide shortage of the surgical anesthetic propofol.3 Our hospital experienced this shortage acutely; during August, September, and October 2010, the usage of propofol was restricted by our pharmacy to preserve the availability of the drug for those patients who needed it critically. During the propofol shortage, our hospital system elected to utilize etomidate as the main alternative to propofol for induction of anesthesia.

Etomidate has been favored historically for intravenous induction of anesthesia in critically ill patients because of its speed of onset and superb hemodynamic stability.4 However, etomidate suppresses adrenal steroidogenesis and may place patients at risk for adrenal insufficiency or death.5 There is ongoing debate about the safety of etomidate in critically ill patients. Prospective human studies of a single induction dose of etomidate have produced conflicting results, with some pointing to increased mortality in patients exposed to etomidate6,7 and others finding no increased mortality with etomidate.8–10 Retrospective studies and meta-analyses of randomized trials have also produced mixed results; some identified increased mortality associated with etomidate,11,12 whereas others failed to detect any significant mortality associated with etomidate.13,14 A structured meta-analysis published by the Cochrane Collaboration in 2015 reported no evidence of increased mortality associated with a single induction dose of etomidate in critically ill patients, although it did find evidence of increased adrenal dysfunction and multiorgan failure.15 All of this has led to a spirited debate regarding the safety of a single dose of etomidate. The purpose of this retrospective study was to survey the clinical impact of the abrupt propofol shortage and to survey for any increase in perioperative mortality that may have been associated with the increased utilization of etomidate in our operating rooms.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective before-and-after study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Texas – Southwestern Medical Center (study number #STU112010–039). At the time of the propofol shortage, we confirmed with the hospital pharmacy that all operating rooms in the hospital were affected by the drug shortage. One central pharmacy oversees the supply of anesthesia medications for the operating rooms. To describe the timing of the drug shortage and our patient population, we performed a random audit of charts in the study window (May through October 2010). This was done by random sample, stratifying by day to account for fluctuations in operating room volume and drawing patients from the entire 6-month window. We stratified by day to account for daily fluctuations in operating room schedules during the week and weekend, ensuring that all charts had an equal probability of being chosen. A total of 600 charts were randomly selected from May through October 2010 using random number tables (100 charts per month) from the historical computerized operating room schedules. This random sample represents approximately 10% of the total operating room volume during that time period. We used this random sample to characterize our patient population. The type of surgery was categorized by surgical specialty. Health status was estimated by calculating Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II), Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II), and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) scores with clinical data derived from each chart using publically available calculators.16,17 The agent(s) used to induce anesthesia were recorded from the original anesthetic records. Other metrics recorded included American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status, mean and median case duration in minutes, scheduled versus emergency surgery, use of intra-operative steroids, and proportion of patients receiving general anesthesia versus sedation. These data were used to create Figures 1 through 6.

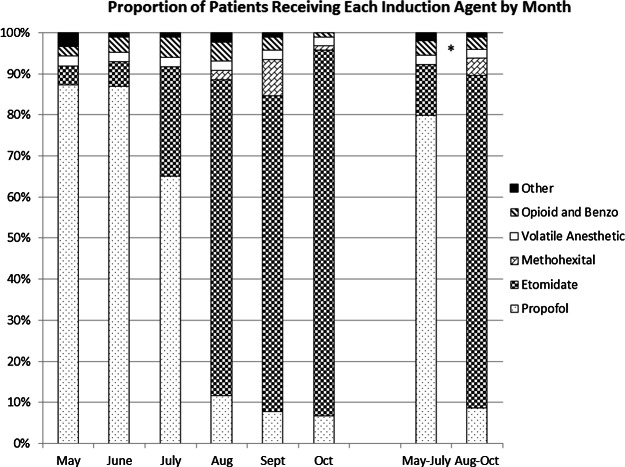

Figure 1.

Proportion of patients receiving each induction agent by month. During the study period, we observed a dramatic rise in the use of etomidate in the operating rooms during a 3-month drug shortage of propofol. We also observed an increased use of methohexital. Prior to the propofol shortage, most patients (80%) in our operating rooms received an induction of anesthesia with propofol. During the propofol shortage, most patients (81%) received etomidate. The asterisk indicates statistical significance, comparing proportional use of etomidate and propofol (P < .0001).

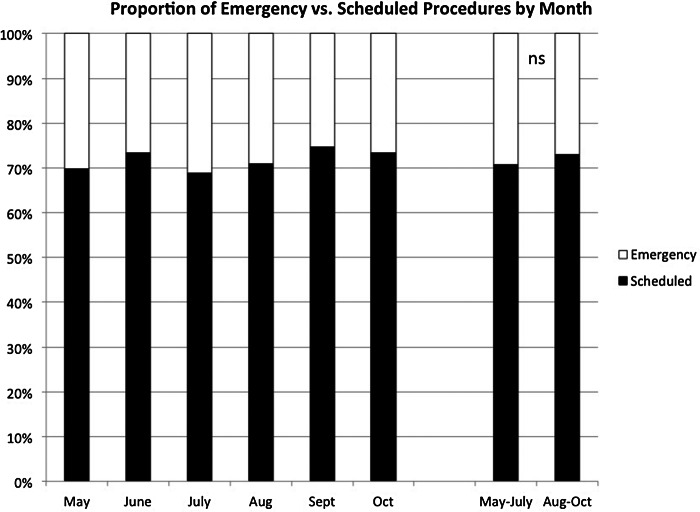

Figure 6.

Proportion of emergency versus scheduled procedures by month. We examined the proportion of procedures that were emergencies. We found that this proportion (approximately 30%) was stable throughout the study period. On chisquare test, there was no statistically significant difference, indicated by “ns,” between May-July and August-October.

In a separate analysis, we studied overall perioperative mortality by reviewing all the charts (N = 5,896) in the entire study window (May through October 2010). We did a more detailed review of the patients identified as deceased, and categorized the cause of death based on the reported cause of death documented in the chart, if a cause of death was noted. Patients who were discharged to hospice and subsequently died were assumed to have a cause of death that was consistent with their underlying diagnosis, for example, malignancy. In cases in which the cause of death was uncertain, we recorded the cause as “unknown.” We studied mortality at one shortterm endpoint (30 days) and one long-term endpoint (2 years). Patients who died more than 2 years after the study period were not counted as part of study mortality. The results of the mortality analysis are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Mortality analysis of all perioperative patients.

|

May-July (group A) n/N (%) |

Aug-Nov (group B) n/N (%) |

P | |

| Survival | |||

| 30 day | 2,796/2,830 (98.80) | 3,034/3,066 (98.96) | .6519 |

| 2 year | 2,735/2,830 (96.64) | 2,969/3,066 (96.84) | .7308 |

| Cause of death | |||

| Malignancy | 32 | 25 | .2700 |

| Septic shock | 13 | 19 | .5094 |

| Trauma | 9 | 14 | .5197 |

| Unknown | 9 | 16 | .3160 |

| Respiratory failure | 6 | 6 | .8805 |

| Hemorrhagic shock | 4 | 2 | .4361 |

| Burn | 3 | 1 | .3561 |

| ESRD | 3 | 0 | .1105 |

| CHF | 3 | 2 | .6759 |

| IC hemorrhage/CVA | 4 | 2 | .4361 |

| Ischemic bowel | 2 | 1 | .6105 |

| Aspiration | 2 | 1 | .6105 |

| PE | 2 | 0 | .2303 |

| MSOF | 1 | 1 | 1.0000 |

| Acute renal failure | 1 | 0 | .4800 |

| CAD/AMI | 1 | 2 | 1.0000 |

| Pneumonia | 0 | 2 | .5007 |

| CAHA | 0 | 1 | 1.0000 |

| AIDS | 0 | 1 | 1.0000 |

| ARDS | 0 | 1 | 1.0000 |

Note: For the mortality analysis, we reviewed all charts of all patients who received surgery in the study window (N = 5,896). For deceased patients, a further review was conducted to determine the cause of death. We did not observe a meaningful change in perioperative mortality during the propofol drug shortage. AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; CAHA = chronic autoimmune hemolytic anemia; CAD/AMI = coronary artery disease or acute myocardial infarction; CHF = congestive heart failure; ESRD = end-stage renal disease; IC hemorrhage/CVA = intracranial hemorrhage or cerebrovascular accident; MSOF = multi-system organ failure; PE = pulmonary embolism.

Statistical analyses were performed using Graph- Pad Prism 6 Software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). For comparison of categorical data including mortality, we used either chi-square test with Yates’ continuity correction or Fisher’s exact test. For comparison of continuous data, we used unpaired t tests. We used a P value less than .05 as an indication of statistical significance for all tests. The stratified random sample was made using random number tables generated by the Microsoft Excel spreadsheet program (Microsoft, Inc., Redmond, WA). All reported values are ±1 SD.

Results

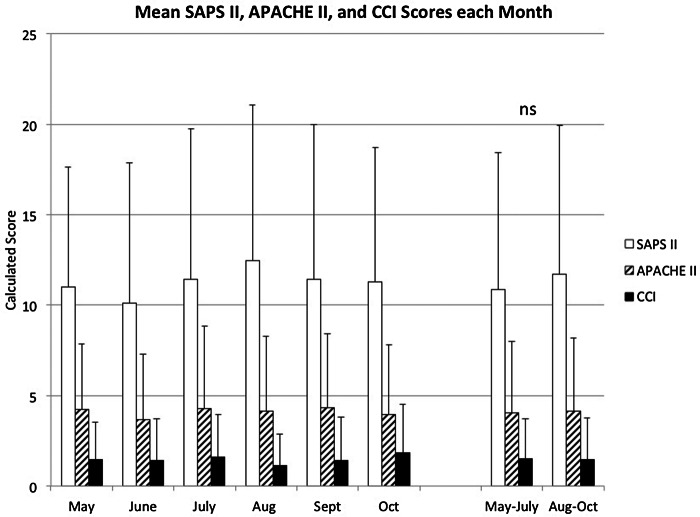

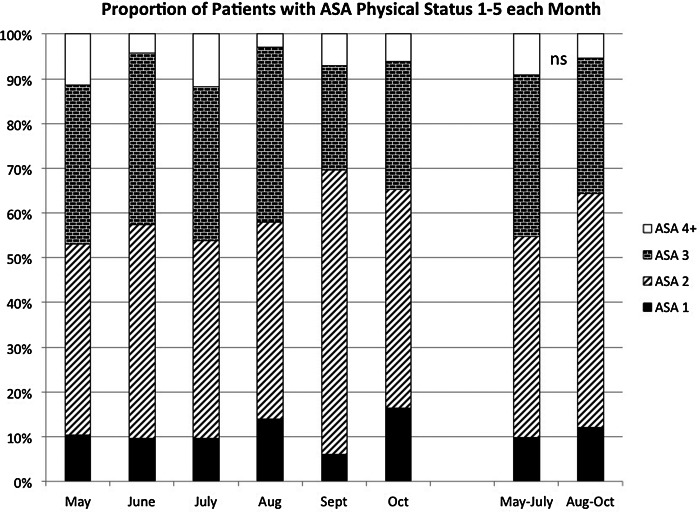

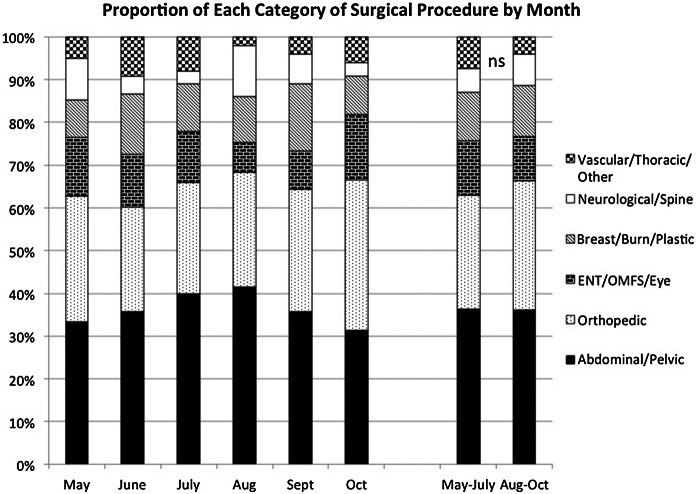

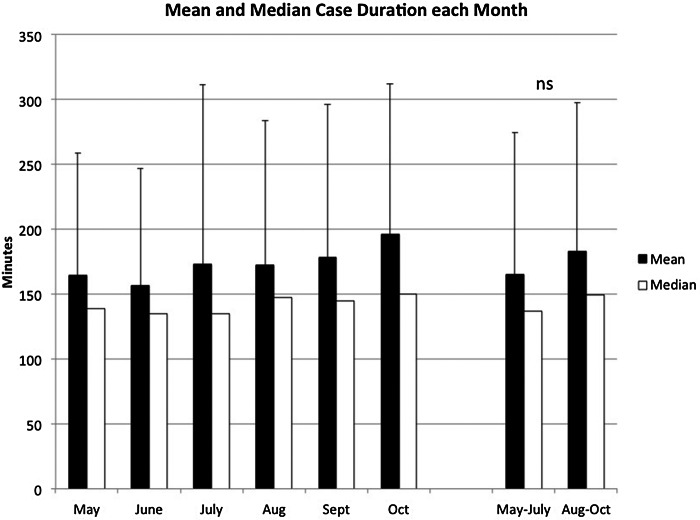

Using the operating room schedule, we identified all surgical patients in the months of May, June, July, August, September, and October 2010 (N = 5,896). Patients were further identified as belonging to group A (May through July, n = 2,830) or group B (August through October, n = 3,066). The proportion of patients receiving etomidate was significantly higher in group B than in group A (P < .0001) (Figure 1). Eighty percent of patients in group A received propofol for induction of anesthesia. Eighty-one percent of patients in group B received etomidate for induction of anesthesia. Comparing group A to group B, we found that the net effect of the propofol shortage was a greater than 6-fold increase in the use of etomidate. The types of surgical procedures performed in our operating rooms; baseline health characteristics measured by SAPS II, APACHE II, CCI, and ASA Physical Status; percentage of emergency procedures; mean anesthetic case duration; proportion of general anesthesia versus sedation; and the percentage of patients receiving intraoperative steroids did not change over the 6-month study window. Figures 2 through 6 illustrate some of these metrics.

Figure 2.

Mean SAPS II, APACHE II, and CCI scores each month. During the study period, we measured the mean Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II), Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II), and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) scores. We found that these scores did not change appreciably over the course of the study. Comparing May-July to August-October, we found no statistically significant difference on t tests in any of these scores, indicated by “ns.” The error bars are ± 1 SD. Lower numerical scores on SAPS II, APACHE II, and CCI are associated with healthier patients and less mortality.

In a separate analysis, we reviewed the charts of all 5,896 patients for mortality and included all patients in the 30-day and 2-year mortality analysis. We found no difference in mortality rate or cause of death between groups A and B at 30 days and 2 years. Nine patients in group A had unknown causes of death, and 16 patients in group B had unknown causes of death. This is illustrated in Table 1.

Discussion

The propofol shortage in 2010 led to an abrupt change in clinical practice in our operating rooms. We observed a substantial increase in the use of etomidate for induction of anesthesia, and a substantial concurrent decrease in the use of propofol (Figure 1). We also observed an increased frequency in the use of agents and techniques that are not commonly utilized in our operating rooms, including methohexital. We did not observe an increase in perioperative mortality associated with the use of etomidate during the propofol shortage (Table 1).

One of the strengths of our study is the relative stability of our surgical patient population compared to the relative instability in the use of propofol and etomidate. Figure 1 shows a substantial inversion in the choice of induction agent during the study period. This stands in contrast to the relative stability in measures of health status (SAPS II, APACHE II, CCI, and ASA Physical Status), types of surgery, surgical duration, and proportion of emergency versus scheduled surgeries (shown in Figures 2–6).

Figure 3.

Proportion of patients with ASA Physical Status 1–5 by month. During the study period, we assessed the proportion of patients each month who were assigned ASA Physical Status 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5. Lower ASA Physical Status (ASA 1) corresponds to healthier patients. We found that the proportion of patients within each ASA Physical Status category was similar month to month. On chi-square test, there was no statistically significant difference in proportional representation between May-July versus August-October, indicated by “ns.”

Figure 4.

Proportion of each category of surgical procedure by month. During the study period, we assessed the types of surgeries done at our institution. “Vascular/Thoracic/Other” indicates surgical procedures done on major blood vessels or noncardiac chest cavity procedures, as well as other miscellaneous procedures not categorized elsewhere. “Neurological/Spine” refers to any surgery done on the brain or spinal cord or spinal column. “Breast/Burn/Plastic” refers to any surgery done on the breasts, any nonfacial plastic surgery, and any burn surgery. “ENT/OMFS/Eye” refers to any surgery done on ear, nose, or throat (ENT); any oromaxilofacial surgery (OMFS); any eye surgery; and/or any facial plastic surgery. “Orthopedic” refers to any surgery done on extremity bones. “Abdominal/Pelvic” refers to any surgical procedure done on the abdomen or pelvis. Comparing May-July to August-October, we observed no statistically significant difference in proportional representation of any category of surgery on chi-square test, indicated by “ns.”

Figure 5.

Mean and median case duration each month. We assessed mean and median duration of surgical cases in the study period and found that there was no statistically significant difference between the mean May-July versus the mean August-October on t test, indicated by “ns.” Case duration is defined by the recorded “start” and “stop” anesthesia times. Case times are measured in minutes. The error bars are ±1 SD.

There are several obvious limitations of our study. First, the before-and-after study design is inherently less robust than a prospective randomized trial. Because of this limitation, it is not possible to draw a firm conclusion regarding the safety of etomidate, beyond noting that we did not observe any obvious increase in mortality. Second, the mortality analysis done in this study relied upon up-to-date mortality data. The hospital in which this study was performed is administrated by the local county government that tracks births and deaths. It is likely that some deaths were not detected in this study, although this effect would be expected to be equivalent throughout all study months. Third, most of the patients in our study were not critically ill, as demonstrated by SAPS II, APACHE II, CCI, and ASA Physical Status scores. Thus, our case series is probably not applicable to patients with critical illness.

There has been considerable debate in the last decade regarding the safety of etomidate. Etomidate is useful as an induction agent because of its superb hemodynamic stability, but its use is hindered by multiple reports of etomidate-associated adrenal dysfunction and possible mortality. A recent quantitative meta-analysis published by the Cochrane Collaboration in 2015 reported that a single induction dose of etomidate is associated with increased risk of adrenal gland dysfunction and multi-organ failure. However, this same meta-analysis concluded that there is no conclusive evidence that a single intubating dose of etomidate causes increased mortality.15 Thus, the debate as to whether etomidate should be used in critically ill patients is fundamentally unsettled. A suitably powered randomized controlled prospective trial is needed to settle this question.

Conclusion

The use of etomidate increased significantly in our operating rooms during a 3-month shortage of propofol. We did not detect an increase in morbidity or mortality associated with the increased use of etomidate.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by UT-Southwestern School of Medicine and the Department of Anesthesiology & Pain Management at UT-Southwestern Medical Center. No conflicts of interest are reported by any of the authors.

This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Texas-Southwestern (#STU 112010-039).

We would like to acknowledge Andrew Matchett, PhD, Department of Mathematics, University of Wisconsin – La Crosse, for his assistance with statistical design.

References

- 1.Kaakeh R, Sweet BV, Reilly C, et al. Impact of drug shortages on US health systems. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68(10):1811–1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Traynor K. Drug shortage solutions elude stakeholders. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68(22):2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen V, Rappaport BA. The reality of drug shortages – the case of the injectable agent propofol. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(9):806–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson-Bastin ML, Baker SN, Weant KA. Effects of etomidate on adrenal suppression: A review of intubated septic patients. Hosp Pharm. 2014;49(2):177–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coursin DB, Fish JT, Joffe AM. Etomidate—Trusted alternative or time to trust alternatives? Crit Care Med. 2013;41(3):917–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sprung CL, Annane D, Keh D, et al. , CORTICUS Study Group. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(2):111–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuthbertson BH, Sprung CL, Annane D, et al. The effects of etomidate on adrenal responsiveness and mortality in patients with septic shock. Intens Care Med. 2009;35(11):1868–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jabre P, Combes X, Lapostolle F, et al. Etomidate versus ketamine for rapid sequence intubation in acutely ill patients: A multicentre randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374(9686):293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tekwani KL, Watts HF, Sweis RT, Rzechula KH, Kulstad EB. A comparison of the effects of etomidate and midazolam on hospital length of stay in patients with suspected sepsis: A prospective, randomized study. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(5):481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tekwani KL, Watts HF, Rzechula KH, Sweis RT, Kulstad EB. A prospective observational study of the effect of etomidate on septic patient mortality and length of stay. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(1):11–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan CM, Mitchell AL, Shorr AF. Etomidate is associated with mortality and adrenal insufficiency in sepsis: A metaanalysis. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(11):2945–2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Komatsu R, You J, Mascha EJ, Sessler DI, Kasuya Y, Turan A. Anesthetic induction with etomidate, rather than propofol, is associated with increased 30-day mortality and cardiovascular morbidity after noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2013;117(6):1329–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner CE, Bick JS, Johnson D, et al. Etomidate use and postoperative outcomes among cardiac surgery patients. Anesthesiology. 2014;120(3):579–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McPhee LC, Badawi O, Fraser GL. Single-dose etomidate is not associated with increased mortality in ICU patients with sepsis: Analysis of a large electronic ICU database. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(3):774–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruder EA, Ball IM, Pickett W, Hohl C. Single induction dose of etomidate versus other induction agents for endotracheal intubation in critically ill patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD010225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cipolla J, Seamon MJ, Chovanes J, et al. Opus 12 Foundation scientific resources. http://www.opus12.org Accessed August2013.

- 17.Hall WH, Ramachandran R, Narayan S, Vijayakumar S. An electronic application for rapidly calculating Carlson comorbidity score. BMC Cancer. 2004;4:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]