Diethylstilbestrol (DES) was used in the United States from 1947 to 1971 to prevent miscarriage. Approximately one-million women were exposed in utero to DES (ref. 1). Women prenatally exposed to DES commonly display epithelial and/or structural changes in the uterus, cervix, or vagina, and can develop clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina or cervix at an early age2–5. The frequency of DES-associated reproductive tract anomalies6 and cancer7 appears temporally related to the time of exposure, with most abnormal findings occurring in women exposed to DES in the first trimester. The specific molecular response to DES that fully accounts for the DES syndrome remains unknown. We recently reported that mice lacking Wnt7a have malformed female reproductive tracts8 (FRTs). The observed phenotype closely resembles the reproductive tract morphologies observed in female mice prenatally exposed to DES (ref. 9), and indicates that Wnt7a may have a role in the DES response in the developing FRT.

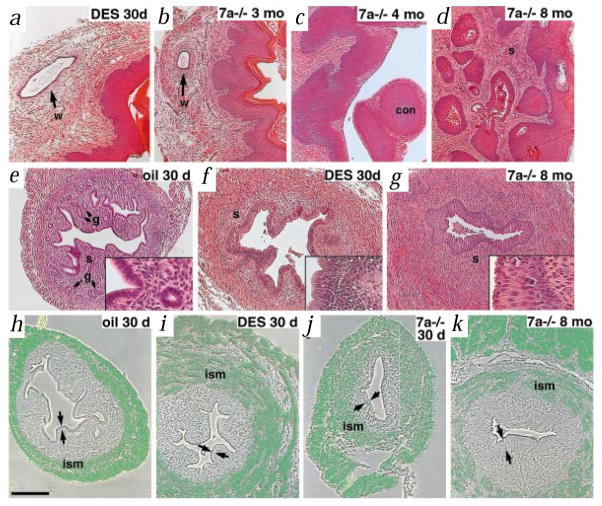

To directly compare the effects of loss of Wnt7a with the effects of DES in the FRT, we generated mice with DES-induced malformed FRTs using an established protocol9,10. DES-exposed mice had shallow vaginal fornices, malformed oviducts that lacked coils, Wolffian duct remnants (Fig. 1a), vaginal concretions and adenotic lesions in the vagina9,11,12. Wnt7a−/− mice also had shallow vaginal fornices (data not shown) and malformed oviducts8. Similarly, Wnt7a−/− FRTs contained Wolffian duct remnants (Fig. 1b), vaginal concretions (Fig. 1c) and epithelial inclusions in the vaginal stroma (Fig. 1d). Control FRTs (oil treated) had normal morphology and tissue cytoarchitecture (Fig. 1e). DES-exposed and Wnt7a−/− FRTs displayed stratified epithelium with reduced stroma and glands (Fig. 1f,g). DES-exposed women were reported to display uterine abnormalities which were attributed to abnormal smooth muscle proliferation13. Both Wnt7a−/− and DES-exposed mice had a disorganized and thickened inner layer of smooth muscle (Fig. 1i–k).

Fig. 1.

Prenatal DES treatment mimics the phenotype of the Wnt7a−/− female reproductive tract. Pregnant CD-1 mice were treated with 200 μg/day of DES (Sigma) suspended in sesame oil, or with oil alone, on days 15–18 of gestation9,10. The exposed female offspring were analysed on the day of birth (day 0) and at subsequent time points. Haematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of DES-exposed and Wnt7a−/− FRTs displayed lesions including Wolffian duct (w) remnants (a,b). Wnt7a−/− FRTs displayed concretions (con) forming in the vaginal fornices (c) and epithelial inclusions in the vagina stroma (adenosis, d), lesions that have been described in DES-exposed mice9,11,12. e, Control (oil treated) uteri had simple columnar epithelium (inset), stroma (s) populated by glands (g) and compact layers of smooth muscle (h). f, Uteri from DES-exposed mice had stratified epithelium (inset), reduced stroma, reduction or lack of glands and a disorganized inner layer of smooth muscle (i). g, Similar to DES mice, Wnt7a−/− uteri had stratified epithelium (inset), reduced stroma, lack of glands and a disorganized inner layer of smooth muscle (j,k). h–k, The organization of the smooth muscle layers is shown using a probe to the myosin heavy chain of smooth muscle. The photomicrographs are composites of the phase images and dark-field silver grains (green) to allow direct comparison of tissue and signal. The inner smooth muscle layer (ism) was compact and organized in the control uterus (h), but disorganized in the DES-exposed uterus (i). The disorganization of the inner smooth muscle in the Wnt7a−/− uterus was less pronounced at one month (j), but easily discernible by eight months (k). The luminal epithelium is denoted by double arrows. Scale bar, 50 μm (insets), 200 μm (a–k).

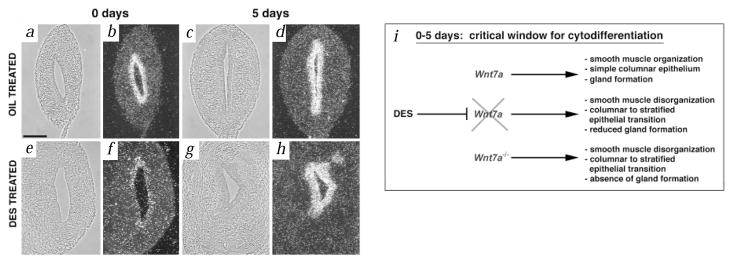

Wnt7a is normally expressed perinatally in the luminal epithelium of the uterus8. As expected, Wnt7a was found to be expressed in the epithelium of the control uterus (Fig.2 b,d). In the DES-exposed uteri, however, low levels of Wnt7a transcripts were detected at birth (Fig. 2f). Wnt7a expression in the DES-exposed uteri returned to high levels five days after birth (Fig. 2h) and was maintained at later stages (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Wnt7a expression is downregulated in DES-exposed mice at the time of birth. The photomicrographs show phase (a,c,e,g) and dark-field images (b,d,f,h) of control and DES-exposed uteri at birth and at 5 days postnatal examining Wnt7a expression. Wnt7a is expressed in the luminal epithelium of the control uterine horn at birth (b) and at five days (d). Low levels of Wnt7a are detected in the luminal epithelium of the DES-exposed uterus at birth (e), however, normal levels of expression are observed by 5 days after birth (h). (i) Schema depicting DES action through Wnt7a. Wnt7a expression is required for proper smooth muscle, epithelial and gland formation in the uterus. DES exposure results in downregulation of Wnt7a during a critical postnatal period, thereby interfering with proper uterine morphogenesis. DES exposure also results in a phenocopy of the Wnt7a−/− uterus. Scale bar, 200 μm.

Previous studies have shown that cytodifferentiation of the female reproductive tract in mice is determined 5–7 days after birth and is dependent on mesenchymal-epithelial interactions14. After this time period, the uterine epithelium is no longer responsive to inductive signals from vaginal stroma15. Thus, the FRT has a critical temporal window during which key patterning events occur. We propose that the observed downregulation of Wnt7a during this critical window is sufficient to account for the mouse DES syndrome. DES-like substances such as tamoxifen have recently been shown to be effective in decreasing the incidence of breast cancer in premenopausal women, although uterine cancer increases twofold (NCI clinical trials web site, http://cancertrials.nci.nih.gov). Understanding the molecular responses in breast and uterine tissues to steroidal pharmacological agents will be of high importance should their use increase in clinical applications.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge A.P. McMahon and B. Parr for Wnt7a mutant mice. We thank J. Miano for the SMMHC plasmid and E. Yang for valuable discussion. This work was supported by NIHNIA-AG13784, NIDR RO1DE11953, a Hirschl Award to D.S. and NIH-T32GM08553 to C.M.

References

- 1.Heinonen OP. Cancer. 1973;31:573–577. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197303)31:3<573::aid-cncr2820310312>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herbst AL, Scully RE, Robboy S. J Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1975;18:185–194. doi: 10.1097/00003081-197509000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaufman RH, Binder GL, Gray PM, Adam E. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;128:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(77)90294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haney AF, Hammond CB, Soules MR, Creasman WT. Fertil Steril. 1979;31:142–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bibbo M, et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1977;49:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sonek M, Bibbo M, Weid GL. J Reprod Med. 1976;16:65–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herbst AL, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;154:814–822. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(86)90464-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller C, Sassoon DA. Development. 1998;125:3201–3211. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.16.3201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iguchi T, Takase M, Takasugi N. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1986;181:59–65. doi: 10.3181/00379727-181-42224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iguchi T, Takasugi N. Biol Neonate. 1987;52:97–103. doi: 10.1159/000242690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLachlan JA, Newbold RR, Bullock BC. Cancer Res. 1980;40:3988–3999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newbold RR, McLachlan JA. Cancer Res. 1982;42:2003–2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaufman RH, Adam E, Binder GL, Gerthoffer E. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;137:299–308. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(80)90913-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cunha GR. Int Rev Cytol. 1976;47:137–194. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cunha GR. J Exp Zool. 1976;196:361–370. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401960310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]