In this Article we compare how AIDS in Malawi is represented in two sources of data, newspaper articles and conversational field journals that depict local interpretations of the epidemic, over the ten-year period 1999–2008. In each of these discursive fields we focus on “moral vocabularies”—the sets of instructions about what people should and should not do to reduce their personal risks or to mitigate the burdens of HIV infection.

During this decade, international AIDS organizations came to define the epidemic in the global South as a crisis to be managed less by individual effort than by interactions with bureaucratic institutions. In Malawi, these include Government of Malawi health facilities that provide testing, treatment, and other forms of medical care, as well as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and associations that support people living with HIV or AIDS (PLWHA) and orphans. In 1995 there were 12 NGOs registered as implementing AIDS activities; by 2005, there were approximately 300, most of them small but formalized community-based organizations in rural areas (Wangel 1995; National AIDS Commission 2005; Swidler and Watkins 2009). Correspondingly, we found a shift in the moral vocabularies deployed in response to AIDS, from injunctions about individual behavioral choices toward those that require engagement with formal institutions.

By comparing the moral vocabularies in media accounts and informal conversations, we uncover striking differences. While the frequency of injunctions to engage with specialized institutions increased in both sources, the increase was far greater in the media than in the journals. And while the media articles echoed the stark injunctions of the international AIDS organizations, the conversational journals describe considerable skepticism, uncertainty, and debate about what people must do to avoid AIDS.

Mapping the moralities of AIDS

We focus on AIDS prevention, treatment, and care as discursive objects, by which we mean they exist primarily in representation and imagination, though with profound implications for materially grounded actions. Our discursive object of interest is the “struggle against AIDS,” manifested in moral injunctions about what ought to be done or not done in response to the risk of HIV infection and the challenges of caring for people most directly affected by AIDS—those who are themselves infected and the orphans of those who have died. These injunctions are both instructive, in that they identify specific personal behaviors such as using condoms or getting an HIV test, and value-laden, in that these behaviors are associated with socially desirable qualities, such as kindness, responsibility, and justice.

Together, the injunctions in each data source constitute a unique moral vocabulary, a lexicon of instructions about how to behave in the face of the epidemic (Lowe 2006; Hitlin and Vaisey 2010). Moral vocabularies are coherent and patterned; they provide shared frameworks for interpretation and may lead those who share them to experience similar emotional reactions to specific events (Lowe 2006; see also Poletta 2006). They are also dynamic and contested. The moral claims that comprise them continually evolve through dialogue and strategic actions by individuals and groups (Black 2011; Zelizer 2007).

In contrast to earlier research that conceived of moral systems as universally shared, recent scholarship on the sociology of morality seeks to identify contrasting and competing systems of morality within a given social setting (Hitlin and Vaisey 2010). Moral understandings are thus challenged and negotiated, and different organizations and subpopulations are understood to have their particular moralities (Smith 2003). This perspective focuses on the social processes that create and sustain understandings of right and wrong for specific individuals at particular moments in time (Lukes 2008). Following Hitlin (2008), we consider actions as moral if they define an individual as a certain kind of socially recognized person (see also Tavory 2011; Frye 2012). Behaviors that are highly morally salient imbue a sense of personal identity that transcends specific situations and “colors our entire being” (Tavory 2011: 280).

In comparing the moral vocabulary found in the newspapers to that in local conversations, we focus on the processes by which moral meanings are shaped by particular institutional domains (Zelizer 2007; Healy 2006). Roth (2010) describes how notions of morality intersect with local constructions of risk, as “increasingly, what people know to be true, good, right, healthy, or dangerous is communicated through the language of risk” (Roth 2010: 469). When social groups confront new risks, moral boundaries are contested, redefined, and contested again as people attempt to contain the threat (Douglas 1992; Healy 2006).

Risks related to personal health are particularly likely to invoke moral responses. From the historical cases of leprosy in Medieval Europe and nineteenth-century sanitation movements in North America, to more recent popular understandings of the American obesity epidemic and efforts to prevent strokes, disease and ill health have often been interpreted as an outward sign of inward depravity and irresponsibility (Turner 1996; Douglas 1992; Saguy 2013; Daneski, Higgs, and Morgan 2010). Because HIV is spread through sex, which is subject to intense moral regulation and surveillance, the perceived risk of AIDS is especially morality-laden. The AIDS epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa is fertile ground for examining how moral evaluations and categorizations evolve over time and across different settings.

Popular moralities: Moral restraint and avoidance of sexual excess

Before the arrival of biomedical interventions to diagnose and treat AIDS, the only guidance for managing the epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa operated through individual-level moral judgment and called for the control of sexual appetites by confining them to loving heterosexual relationships between equals (Esacove 2010). Translated into the idiom of the conversational journals, this means resisting the temptations to have sex “anyhow” (without abiding by traditions that prescribe when and with whom sex is permissible) and to “change partners like clothes.” Such injunctions to practice self-restraint are not new: Malawians have long advised each other to regulate sexual activity in order to avoid ethnocultural ritual illnesses brought about by transgression (Zulu 1996); more recently, missionaries attempted to strengthen Malawians' self-restraint in sexual activity (Linden and Linden 1974; Setel, Lewis, and Lyons 1999).

Contemporary entreaties to practice self-restraint can be understood as an adaptation of older moralities to contain the threat of the AIDS epidemic (Klaits 2005). Once Malawians knew that HIV was transmitted through sex, men and women mobilized their existing moral understandings, including categories of bad people (e.g., prostitutes and bar girls, mobile men, and sugar daddies) and typologies of bad behaviors (e.g., “moving” with many partners, old men seducing young women with money, young women seducing rich men by wearing miniskirts, and spending money on alcohol rather than on one's family). These enduring moral understandings became increasingly important as people strove to find safety in the face of the new threat (Kaler 2006).

Institutional rationalities: Knowledge and technologies of the self

Over time and particularly in the media accounts, this emphasis on individual-level moral restraint was increasingly overshadowed by instructions to interact with organizations in order to develop a studied and technical knowledge of one's own health and body. The shift can be understood in terms of Foucault's “technologies of the self,” which he defines as “specific techniques that human beings use…which permit individuals to effect by their own means or with the help of others a certain number of operations on their own bodies and souls, thoughts, conduct, and way of being, so as to transform themselves” (Foucault et al. 1988: 18).

In the context of AIDS, technologies of the self include participation in support groups and networks that forge collective identities for people living with HIV; the rituals of getting tested for the virus and receiving certified evaluations of one's health status; and, above all, the stringent antiretroviral treatment regimen, with its requirements for precisely timed consumption of medication and ongoing surveillance of bodily responses through which one comes to know and, ultimately, protect and care for oneself (Dilger 2012; Mykhalovskiy, McCoy, and Bresalier 2004; Nguyen 2010).

Two features of Foucault's theory of technologies of the self are particularly relevant to the institutionalization of the struggle against AIDS: the emphasis on self-knowledge attained through particular actions (e.g., “get tested and know your status”) and the emphasis on accepting disciplined, lifelong relations with authoritative others, such as medical professionals and health workers (Dilger 2012). An HIV-positive activist in South Africa talking about starting treatment makes the connection between treatment and relations with expert authority even clearer, perhaps not coincidentally adopting the same religious terminology used by Foucault (1997): “I am like a born-again.… It's like committing yourself to life, because the drugs are a lifetime thing. ARVs [antiretrovirals] are my life now” (Robins 2004). As we demonstrate below, the acknowledgment and acceptance of this expertise and authority, and the conversion of that acceptance into new forms of behavior, are increasingly prevalent in the moral vocabularies of both of the discursive fields we examine, but become particularly paramount and uncontested in the newspaper accounts.

Material responses to AIDS, 1999–2008

Before analyzing how these two moralities evolved in newspaper articles and conversational journals, we briefly identify the actors and events involved in the response to AIDS in Malawi between 1999 and 2008. This period was characterized by a proliferation of institutional actors in the epidemiological, economic, political, and social landscapes of AIDS (Watkins, Swidler, and Hannan 2012). The massive global response to AIDS greatly intensified the involvement of the state and of state-like institutions in daily life (Nguyen 2005; Comaroff 2007).

The global funding for the response to AIDS generated a host of new organizations. Some were formally organized by intragovernmental and non-governmental organizations and national states, such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (“Global Fund,” an intergovernmental organization), the Joint United Nations Programme on AIDS (UNAIDS, the lead organization in developing a global response to the pandemic, also intergovernmental), the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR, an American bilateral aid initiative), and the Malawi National AIDS Commission (NAC, a national agency) (Watkins et al. 2012). Concurrently, new national NGOs were organized and staffed by Malawians, including national-level groups such as The Evangelical Alliance Relief Fund (TEARFUND) and Malawi's National Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS (NAPHAM), and community-based organizations such as the Chimwemwe Orphan Support Group in Zidyana Village and the Imam AIDS Support and Drama Group in the Balaka mosque (Hannan 2012). International NGOs that antedated the epidemic adopted the struggle against AIDS as part of their core mission, such as Save the Children, World Vision, and Population Services International (Robinson 2011). A study of the growth of AIDS-related NGOs in Malawi between 1999 and 2004 found that the number of NGOs registered by the government as AIDS organizations increased from 31 to 55, and those registered as working on orphan support increased from 17 to 53; the number of NGOs in other sectors, such as water and sanitation, the environment, and health in general either remained the same or declined (Morfit 2011). In 2006, the National AIDS Commission counted 311 AIDS organizations (National AIDS Commission 2006).

The decade on which we focus was also characterized by a dramatic shift in funding from prevention and care to testing and treatment. In the late 1990s, HIV testing and antiretroviral therapies were already commonplace in the United States and Europe but were not yet available in Africa, except among a wealthy and well-connected minority. In the early 2000s, the Global Fund, as well as other donor institutions, began providing funding. Malawi received one of the first, and one of the largest, Global Fund grants to high-prevalence countries in sub-Saharan Africa. About two-thirds of the funds were allocated to the health sector for biomedical care (primarily testing and treatment of opportunistic infections and AIDS); the rest went to prevention and support of defined groups, particularly people living with AIDS and orphans. Other donors complemented the Global Fund, including PEPFAR, which provided more than $US200 million in support between 2006 and 2010 (International Business Publications USA 2013).

This infusion of funds shifted the organizational response to AIDS toward testing and treatment and away from behavior change. HIV counseling and testing were requirements for accessing life-prolonging antiretroviral drugs. As a result, the staff of health organizations had to be taught to administer the technologies of testing and treatment and trained to counsel HIV-positive individuals on specific practices requiring disciplined knowledge of the self, such as adhering to a specific regimen for taking the drugs, “living positively” by eating a balanced diet and exercising, and using condoms consistently if one had an HIV-positive sexual partner. Because testing was the crucial first step and because global funders gave priority to prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV, a policy was established of routine testing of pregnant women at antenatal services in health clinics. Although official policy on testing holds that HIV tests are voluntary, in practice pregnant women report that they would not be given antenatal care unless they were tested by a health professional, which was justified as necessary to receive the medication nevirapine to prevent transmission from mother to unborn child (Angotti, Dionne, and Gaydosh 2011). These technologies thus led to new forms of official coercion or pressure that went beyond the strategies that Malawians previously used to regulate each other's sexual excesses.

In addition to the tidal wave of funds targeting testing and treatment, these new sources also provided funds for prevention and support, resulting in the creation of rigid bureaucratic standards for aiding the afflicted. What had been household-level care of the sick was institutionalized as village-level Home Based Care (HBC) committees, with formally drafted constitutions, slates of elected officers, and “HBC Kits” with aspirin and a few other medications and basic supplies such as gauze and gloves. What had been care of orphans by extended families became OVC, care for “orphans and other vulnerable children” (Watkins and Swidler 2012). To participate in these activities, all organizations had to learn new techniques of monitoring, including forms on which to report accomplishments and expenditures and vocabularies to incorporate in reports and proposals in order to convey technical expertise.

AIDS was not the first phenomenon in Malawi to become institutionalized or to generate new technologies of the self. The colonial and post-colonial eras were replete with “development” projects, such as formal education, “improved” agriculture, and basic health care, which encouraged the transformation of Malawians into modern subjects expected to engage in new ways of governing themselves. Beginning in the 1930s, the British colonial government mounted a health campaign to deal with sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). It established STD clinics, distributed pamphlets with information about the infections, and emphasized that a cure was available at government hospitals and dispensaries (Chirwa 1999: 156). AIDS, however, is qualitatively different from its predecessors. Unlike STDs in the colonial period, which were seen as a problem that primarily affected labor force productivity, AIDS has been understood by UNAIDS as a historically unprecedented global emergency, and by Malawians as threatening the continued existence of the nation. Framing AIDS as a uniquely threatening phenomenon makes the actions that people take in response to this threat distinct from the actions taken in response to developmental imperatives to attend school, grow improved crops, or seek basic health care. Indeed the technologies of the self enjoined by AIDS are meant not only to improve lives, but to save them from annihilation. The response to AIDS is thus a moral action (Tavory 2011; Hitlin and Vaisey 2010), insofar as it invokes an imperative to not harm others or oneself, in a way that other development initiatives have not been.

Data

Our data consist of two collections of texts. First, to identify the trends in normative AIDS injunctions in the media, we analyze a collection of all the articles mentioning “AIDS” in the leading Malawian newspaper, The Nation, from 1999 through 2008.1 The articles consist of both news and human interest stories and were written primarily by staff writers or reporters for Reuters and the Associated Press. Each article was digitally photographed and archived. We randomly selected 50 percent of all articles from each year, resulting in an analytic sample of 708 articles (see Table 1).2 The unit of analysis is the article.

Table 1. Number of articles and field journals analyzed in two-year periods between 1999 and 2008.

| Year | Articles | Journals |

|---|---|---|

| 1999–2000 | 81 | 42 |

| 2001–2002 | 143 | 50 |

| 2003–2004 | 157 | 169 |

| 2005–2006 | 216 | 186 |

| 2007–2008 | 111 | 41 |

| Total | 708 | 488 |

The second source of texts, a large archive of observational field journals covering the same time period as the articles, is unusual. Written by local participant observers, the journals document the discourse on AIDS as it occurred in everyday life (Watkins and Swidler 2009). The journals project was conducted alongside the Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Households (MLSFH, 1998–2012), a longitudinal household study on responses to family planning and to AIDS.3 As part of the study, 22 skilled field assistants were asked to keep journals of everyday conversations in natural settings, such as bus stations and clinic waiting areas. They were then asked to write what they heard, in English, in a journal. The journals were subsequently typed and anonymized.4

The unit of analysis for the journals was a conversational incident, conceptualized as an exchange between two or more people, bounded by time and space (Angotti and Kaler 2013; Kaler and Watkins 2010). For example, a conversational incident might begin with three women talking at a water tap; others might join, some might leave; the topic might shift from talk about how HIV is spread to talk about the death of a neighbor from AIDS to the risk of becoming infected by one's spouse. The incident ends when the conversation turns to an unrelated topic, such as expectations for the current grain harvest, or when the women leave the water tap. To draw our sample, we first stratified the list of journals by region (North/South) to approximate the regional ratio of the population of Malawi according to the 2008 census.5 We then used cluster sampling, with journals as the primary sampling unit, and sampled all conversational incidents within each selected journal. This resulted in a total of 150 journals analyzed and a total of 488 conversational incidents (see Table 1). Given the large number of clusters and small mean incidents per cluster (3.25), this approach should have limited effect on the precision of our estimates.

Methods

We identified four broad categories of injunctions: “Change your sexual behavior,” “Seek biomedical care,” “Treat people living with AIDS equitably,” and “Talk about AIDS.” Each category contains two to four sub-categories (see Table 2). The injunctions are typically directed at categories of individuals, such as women, men, or “youth of today,” rather than at specific organizations, such as the Ministry of Health or the Living Waters Church. As we demonstrate, the two sets of data diverge in the relative frequency of specific injunctions and the certainty with which these are expressed. Although most injunctions appear in both the articles and the journals, some injunctions appear regularly in the journals but rarely in an article. The advice to be selective in choosing a sexual partner as an alternative to strict abstinence or fidelity, for instance, is not on the list of recommendations promoted by international organizations or the Government of Malawi, but rather a strategy developed through conversations in local social networks (Watkins 2004), and is rarely legitimized in an article.

Table 2. Normative injunctions in the struggle against AIDS.

| Major category | Sub-category |

|---|---|

| 1. Change your sexual behavior |

|

| 2. Seek biomedical care |

|

| 3. Treat people with AIDS equitably |

|

| 4. Talk about AIDS |

|

To compare the levels of debate and uncertainty surrounding moral injunctions about AIDS in the two data sources, we specified in our coding scheme whether the source includes injunctions that conform to orthodox global AIDS policy (e.g., one must be faithful), injunctions that dissent from the orthodoxy (e.g. condoms promote immorality), or both (e.g., one person says it is good to learn your HIV status, while another says it is bad because a positive test result will lead to emotional distress and even suicide).

We use two measures to analyze trends in injunctions over time. First, we examine the absolute numbers of injunctions in the articles, which represent a random sample of the complete universe of articles mentioning AIDS in the country's leading newspaper. Second, we calculate the proportion of articles or conversational incidents in which a particular conforming or dissenting injunction was mentioned. Not all articles or incidents contained injunctions;6 the denominators for these calculations were all articles and conversational incidents mentioning HIV. To avoid fluctuations in proportions due to differences in denominators (i.e., the total number of journals or articles in a given year), we pooled the data into two-year periods. For both articles and journals, our data are sparsest at the beginning of the period and most plentiful during the period 2005–2006, the peak of the rollout in HIV testing across Malawi (see Table 1).

We developed a coding spreadsheet in which each row contained the article name or the identifier of a conversational incident in a journal and each column contained the injunctions. All coded data were imported into STATA 12.0 for analysis. Combining the articles and journals provided nearly 1,000 texts. We evenly divided and randomly assigned the articles and journals among the co-authors to code.7 Our communication about coding began with pilot coding to establish inter-rater consistency. It continued for a full year, with semi-annual face-to-face meetings, bimonthly conference calls, and frequent email exchanges to discuss questions or concerns that arose during the coding of manifest content, as well as to share interpretations of latent content in the data.

Methodologists debate the applicability of reliability in qualitative research (Armstrong et al. 1997). In our case, ensuring reliability was paramount for our analytic goal of identifying and quantifying AIDS injunctions (Neuendorf 2002). Nonetheless, despite our best attempts to be consistent, we do not claim that there are no inconsistencies in our coding. Indeed, issues of ambiguity and re-evaluation routinely occur in coding qualitative data.

Trends in major categories of moral injunctions

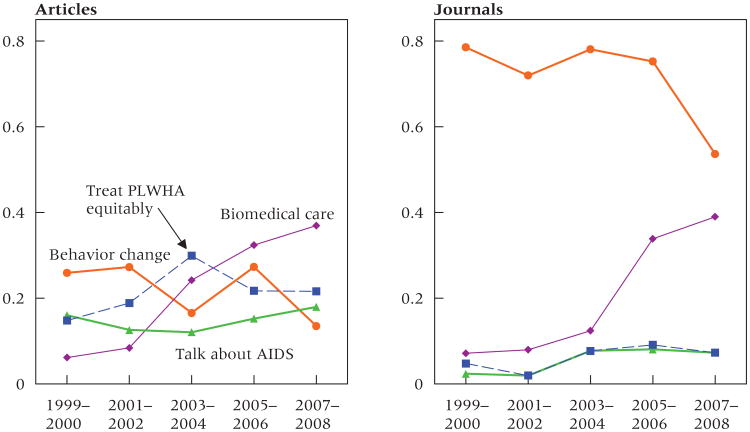

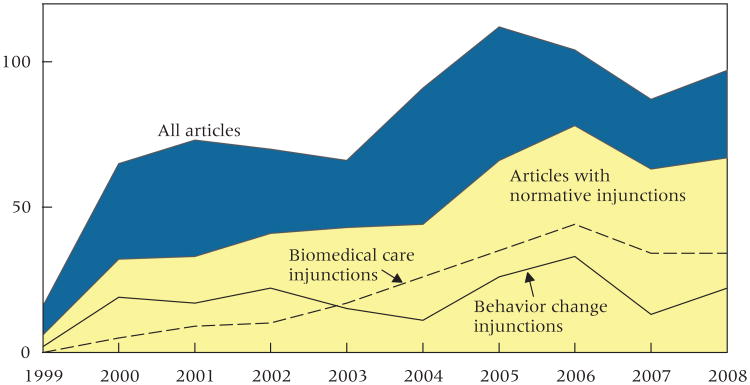

We begin by examining trends in the overall categories of moral injunctions in the two sources, then discuss each category in greater detail. Figure 1 shows a steep increase in the proportion of injunctions encouraging individuals to seek biomedical care, and a concomitant decrease in injunctions about sexual behavior in both the articles and the journals.

Figure 1. Prevalence of normative AIDS injunctions by overall categories in articles and field journals, 1999–2008 (proportions in each category).

Biomedical care is the most institutionalized area of the struggle against AIDS: it is not possible to be tested for HIV or receive free treatment without interacting with the elaborate health system bureaucracy. As biomedical technologies became more readily available, exhortations to individuals to interact with this bureaucracy increased. Sexual behavior is the least institutionalized. Changing sexual behavior to avoid AIDS is quintessentially about personal moral restraint and self-discipline. When directives to change one's sexual behavior are discussed, AIDS is often characterized as an avoidable problem, the result of personal moral failure. A 2000 article illustrates:

AIDS should not scare us. Unlike tuberculosis, cholera, and other diseases, one actually goes out in search of AIDS through promiscuity. It does not catch a person unawares. (Kalulu 2000)

In the early 2000s, as international policy shifted toward biomedical care, yet before these new technologies were widely available in Malawi, newspaper articles often discussed sexual behavior change in conjunction with the institutionally mediated strategies of testing and treatment. During this period, injunctions to restrain sexual desires were framed as steps that individuals could take even as they waited for testing or antiretroviral therapies to reach their villages. An article from 2002 summarized recent national-level developments:

Unfortunately, antiretroviral therapy is still prohibitively expensive, though many humanitarian organizations are trying to make it more affordable to the poor people. Up to that time, our main solution is prevention. To succeed in our fight to prevent AIDS, we have just three weapons: abstinence, mutual faithfulness and consistent use of condoms. We should use all three weapons accordingly and we should not hesitate to offer them as different solutions to different people. (Toufexis 2002)

The rise in biomedical injunctions in the articles is steepest between 2001–2002 and 2003–2004, a period that coincides with the influx of Global Fund support and the growing availability of free antiretroviral therapy (ART). The increase is slightly later, and steeper, in the field journals. That the press led the shift toward biomedical injunctions may be attributable to a tacit but mutually advantageous arrangement between institutions promoting biomedical solutions, which need the press to disseminate their messages, and the newspaper editors, publishers, and staff writers, who need a constant supply of content. Newspapers have become increasingly available in rural areas, but readership remains more limited than in urban areas, such that the diffusion of messages about the availability and importance of antiretroviral therapy would have reached rural residents later than those living in urban areas. The lagged increase in informal conversation was probably influenced by the earlier availability of testing and treatment in urban areas. In contrast, testing and treatment were not realistic opportunities in rural areas until they became available in local health facilities, between 2004 and 2006. Once they were available, however, there were many conversations about friends, relatives, or neighbors who had been on the verge of death but had now become “plump” and were back at work on their plots.

There was still reason for debate. Although MLSFH survey responses suggest that Malawians have known for years that one cannot tell who is HIV positive just by looking, the journals reveal many examples of conversations in which participants combine information on visible symptoms with information on a person's medical and sexual histories in order to determine who had AIDS (Watkins 2004). This difficulty acquired a new twist with the availability of ART. In the past, they said, one could see who was infected and who was not and thus select a safe partner, but now one could easily be mistaken and die as a result. For an individual with AIDS, ART was good; for the community, it was considered akin to a public health hazard.

The early rise of biomedical injunctions may also be related to the role of the African press in prescribing and defining developmental goals. News media, particularly press and radio, have historically been used to promote socially desirable forms of behavior, in stories that blur the distinction between reporting and advocating. Family planning and home hygiene, for instance, have been covered by the press in the form of news stories or features, in tandem with public awareness campaigns launched by government ministries or NGOs. Consequently, press coverage is a component of efforts by national elites to prescribe certain types of behavior and proscribe others. Given the timing of global campaigns to promote HIV testing and treatment, it is reasonable to assume that the timing of local press coverage is in part related to this prescriptive role of national media.

Following the rollout of free antiretroviral therapy to rural health facilities, we see in both sources a decrease in the relative frequency of injunctions to change behavior. This marks a shift in the conceptual center of gravity of the struggle against AIDS. As the injunctions to interact with health institutions increased, injunctions to change sexual behavior declined in both sources. By the middle years of our analysis, the frequency of sexual behavior injunctions in the articles dropped below that of biomedical injunctions. In the journals, however, the frequency with which people advised each other to change their sexual behavior continued to exceed injunctions to seek biomedical care.

The changes in the relative frequency of injunctions related to biomedical care and behavior change charted in Figure 1 are consistent with changes in the absolute frequency of discussions of these topics in the newspaper data (see Appendix Figure 1). The number of articles about AIDS increased sixfold between 1999 and 2008, with articles discussing biomedical care rising between 2002 and 2006 and articles discussing behavior change declining after 2006.

As shown in Figure 1, the other two categories of injunctions, “Talk about AIDS” and “Treat PLWHA equitably,” were much more frequent in the articles than in the journals. These morally charged injunctions about de-mystifying AIDS and reducing stigma emanate primarily from international organizations such as the World Health Organization and UNAIDS and reach Malawi directly through wire stories and indirectly through the programs of global NGOs.

Injunctions calling for equitable treatment for PLWHA and talking about AIDS are interpreted differently in the articles than in the journals. In the articles, equitable treatment for PLWHA is framed in terms of human rights in general and stigma in particular, perhaps because of the influence of Western experience of AIDS as a disease associated with gay men (Angotti 2012; Shilts 1987). According to the press articles, the rights of PLWHA are to be protected through the formation of organizations, such as national networks of HIV-positive people and local support groups. A 2005 article quoting a religious leader deftly combines the international rhetoric of rights, the religious rhetoric of care, and the institutionalization of the struggle against AIDS. Father James Chifisi of a Catholic diocese in Malawi states:

The church has a duty of giving hope and support to people, as the HIV/AIDS pandemic has reached a climax…. We are also forming committees on HIV/AIDS rights from parish to archdeaconry levels, sensitizing people on AIDS care and support. (Tayanjah-Phiri 2005)

These groups work to “break the silence” and reduce stigma. In this context “talking about AIDS” means disclosing one's own serostatus publicly and taking on an identity as a person “living positively” with AIDS.

In the journals, on the other hand, these injunctions mean something different. Although churches have long promoted faithfulness to one partner as an ideal, in the journals sex is considered a normal and enjoyable activity, fundamental to human nature, and AIDS is readily discussed. The injunction to treat equitably those who are infected is more often interpreted as referring to the normal obligations of reciprocity and interdependence, and less often as extending a helping hand to a despised minority. In addition, in a country in which virtually everyone claims a religious denomination, the injunction echoes religious responsibilities to care for those who are ill. Sermons about AIDS call for congregation members to “love each other,” “treat each other with kindness,” and refrain from blaming or isolating others (Trinitapoli 2009). In this context, the injunctions of institutions to treat PLWHA equitably and kindly were redundant.

Trends in sub-categories of moral injunctions

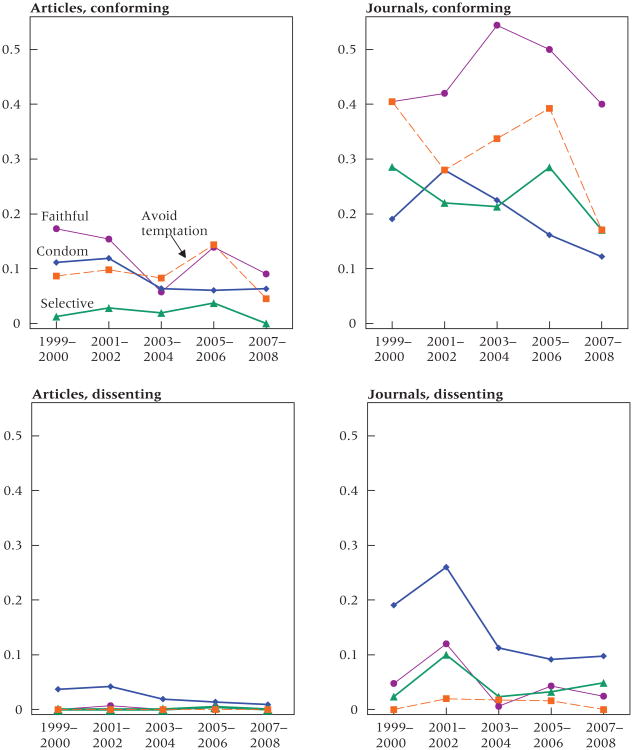

Change your sexual behavior

In Figure 2 we examine the trends in each of the four sub-categories of injunctions to change sexual behavior: be faithful and avoid having sex outside of marriage, use a condom, be selective in the partner you choose to have sex with, and avoid “temptation” by prostitutes, sugar daddies, and others. The difference in magnitude between the two sources is striking: conversations in the journals privilege all four sub-categories much more than do the articles. When we examine the frequency with which each sub-injunction is discussed in ways that conform to international AIDS discourse (Figure 2, top panels), the preferred route to safety in both sources is faithfulness in marriage. Between 2005–2006 and 2007–2008, the proportion of both articles and journals containing sexual behavior injunctions drops, but the proportion of conversational incidents in the journals that emphasize faithfulness remains high, above 40 percent.

Figure 2. Prevalence of conforming and dissenting injunctions, by type, to “change your sexual behavior” in newspaper articles and field journals, 1999–2008 (proportions of each type).

Injunctions to stay faithful are often discussed in tandem with injunctions to “avoid temptation.” For men, temptation takes the form of seductive women wearing miniskirts, who are perceived to be mercenary and therefore dangerous; men are perceived to be unable to resist infidelity. For women, temptation comes when the husband does not provide for his wife and children, when he does not adequately fulfill his sexual duties, and/or when he has outside partners, encouraging his wife to seek revenge by taking an extramarital partner of her own (Tawfik and Watkins 2007).

The proportion of dissenting injunctions—those that run counter to international AIDS discourse—marks another distinction between the moral vocabularies in the articles and those in the journals. The frequency of dissenting injunctions is greater in the journals; it appears that newspaper editors and writers are either true believers or simply remain silent rather than dissent from the international advice. By contrast, the journals provide evidence of considerable debate about what should or should not be done to avoid AIDS.

This debate was particularly common in discussions about condoms. While dissenting injunctions about condoms are considerably more frequent in the journals, condom use receives more debate and critical discussion relative to the other behavior change sub-injunctions in both sources throughout the ten-year period. In the journals, the trends in conforming and dissenting injunctions regarding condom use are similar to each other, an indication that both perspectives are often voiced during the same conversational incident. One participant might say, “we must use condoms when going with prostitutes” (a conforming injunction), while another might counter that condoms should be avoided because they encourage sinful behavior (a dissenting injunction). Dissent was often phrased in terms of the moral wrongness of condom use—it contradicts religious teachings and promotes immorality—and in terms of the idea that condoms are a barrier to the exchange of fluids, regarded as critical to experiencing the joys of sex (Chimbiri 2007; Tavory and Swidler 2009).

Although faithfulness is the most common behavior change injunction in both sources, it is not unanimously regarded as the panacea for avoiding AIDS. Reservations were expressed in the journals about fidelity as a prevention strategy. It is never said that one should not, in principle, be faithful, but rather that having only one partner reduces pleasure by limiting variety in partners and, especially, that faithfulness is difficult if not impossible to accomplish, given human nature and abundant temptations. Similarly, there is both agreement and disagreement about the value of careful partner selection. While it is mentioned positively far more often in the journals than in the media, partner selection, like faithfulness, is said to be difficult in practice, since diligent investigation to gain useful knowledge of the past behavior of potential partners is impractical or unlikely in some circumstances in which people find themselves, such as traveling, drinking to excess, or being tempted by an attractive woman (for men) or a man with money (for women).

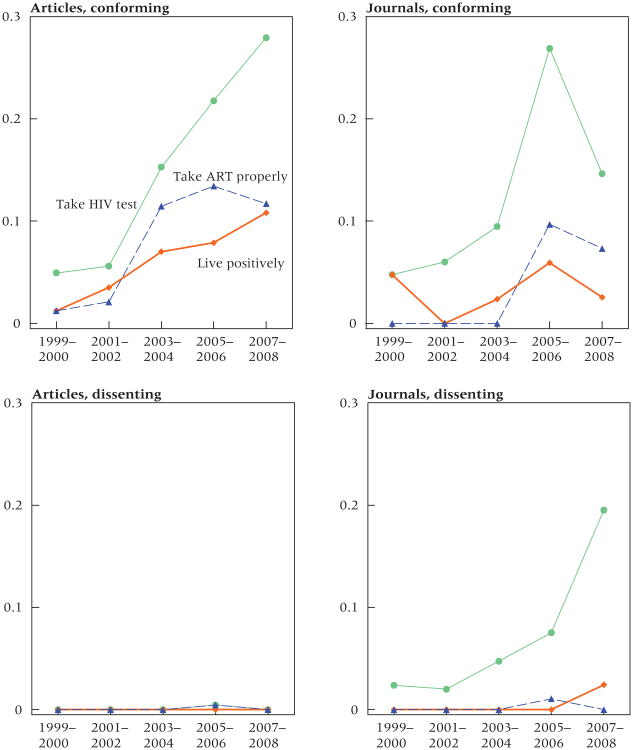

Seek biomedical care

As noted earlier, we document a sharp increase in biomedical strategies for fighting AIDS in both sources, as evidenced by the increased proportion of injunctions that call on Malawians to visit test centers and follow the dictates of medical personnel (Figure 3). The sub-categories of biomedical injunctions include taking an HIV test, taking antiretroviral therapy properly, and following the injunctions of HIV counselors to “live positively”—for example, caring for oneself through proper nutrition and maintaining an optimistic outlook after receiving a positive test result.

Figure 3. Prevalence of conforming and dissenting injunctions, by type, to “seek biomedical care” in newspaper articles and field journals, 1999–2008 (proportions of each type).

In newspaper articles, the proportion of biomedical injunction sub-categories that conform to international AIDS discourse rises across the decade, but taking an HIV test experienced the steepest increase. It peaks in 2007–2008, when 28 percent of all articles include an exhortation to take an HIV test. Similarly, in the journals, there is a sharp increase in the proportion of injunctions that are biomedical in type, particularly taking an HIV test (though note the decline in conforming injunctions about HIV testing between 2005–2006 and 2007–2008). The other two injunctions, taking ART properly and living positively, receive less discussion in the journals than they do in the articles. For example, in 2007–2008, the proportion of articles containing injunctions to live positively is 11 percent, more than three times the proportion over the same period in the journals (3 percent).

In both articles and journals, there is virtually no debate over whether taking ART properly and living positively is a good idea. By contrast, taking an HIV test is subject to considerable doubt and debate in the journals, as shown through the steep rise in the proportion of dissenting injunctions in the journals over the decade. Between 2005–2006 and 2007–2008 the proportion of injunctions advising Malawians against getting tested rose from 8 percent to 20 percent.

Examples from the two data sources illustrate the difference between the unambiguous support for testing in the articles and the ambivalence and doubt in the journals. A newspaper feature story in 2004, “The Positive Story of Fred Purse,” profiles a man who was tested and found to be HIV positive. Purse admits, “I used to go around bars and nightclubs. I used to play around with the girls a lot.” But now, living on ARVs, he is a frequent speaker at events encouraging Malawians to be tested and a prominent member of the Association of People Living with HIV/AIDS in Malawi. And he assures the article's journalist that he “is not touching” his wife anymore. The article presents Purse as a model of a person living positively, which the journalist defines as “living life to the full, without fear of intimidation, or being daunted by the belief that being HIV positive means the end of the world for the infected individual.” The article repeatedly calls upon Malawians to get tested to find out their status, and extols the societal and individual benefits of testing (Nyoni 2004).

In contrast, the following passage from an observational journal written in 2005 shows much greater ambivalence. Tennison, a friend of the field assistant, is telling a story to a group of men at the market about the time he went into town to get an HIV test. On the way there, he met a friend on the minibus. The journal entry reads:

He [Tennison] said that his friend discouraged him and said that that's very stupid and change that idea immediately because lots of his friends who had gone for testing had died because most of them were told that you have the virus but that is not the end of the life but take care of yourself by having exercises and ample time of resting and avoid unprotected sex and eat well balanced diet. Tennison's friend said that because his friends knew that they had the virus they became very mad as regards to sex for they were not choosing carefully who to sleep with and going plain [no condom] to the bargirls knowing that they had already gone [contracted AIDS].

Tennison went on saying that he was convinced and cancelled his plan to go and get tested. (Simon_050101)

Significantly, the arguments made both by those who spoke negatively and by those who spoke positively about the value of testing were based on the assumption that one would learn from testing that one was HIV positive. This assumption reflects the absence of accurate information about the transmission probabilities of HIV. The MLSFH survey, conducted in the same areas of Malawi as the journals were written, found that 60 percent of rural Malawians thought the likelihood of becoming infected through a single act of unprotected intercourse with an HIV-positive person was certain, with another third considering it to be highly likely (Anglewicz and Kohler 2009: 89). Epidemiological studies, by contrast, put transmission probabilities at under 1 percent, even when there are co-factors such as genital sores (Gray et al. 2001; Hughes et al. 2012).

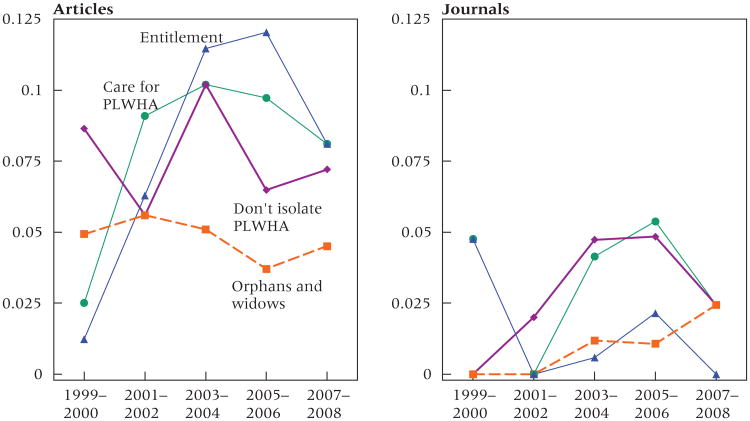

Treat people with AIDS equitably

The proportion of statements urging that people with AIDS be treated equitably increased in the articles, in particular in the early half of the time period studied (1999–2004). In contrast, the frequency with which such injunctions were mentioned in the journals changed little over time (Figure 1).8 Figure 4 examines trends in the sub-injunctions: providing medical care and social support to the sick, providing HIV-positive individuals with goods and services to which they are entitled, not isolating or stigmatizing the infected, and caring for orphans and widows left behind by the deceased. The proportion of articles that mention caring for people living with HIV/AIDS increased from 3 percent in 1999 to 10 percent by 2005–2006. Injunctions related to the need to provide people living with HIV/AIDS with the special allotments of goods and services to which they are entitled follows a similar trajectory, increasing from almost nothing to about 12 percent in 2005–2006. The proportion of articles that include advice related to orphans and widows, however, actually decreases slightly over the decade.

Figure 4. Prevalence of normative injunctions, by type, to “treat people with AIDS equitably” in newspaper articles and field journals, 1999–2008 (proportions of each type).

In the journals, these types of injunctions are far less common than in the articles, an indicator, as discussed above, that the need to provide for the afflicted is taken for granted as part of everyday responsibilities to others, reinforced by religious commitments to care and kindness. The most common injunction is caring for PLWHA, which peaks in 2005–2006 at 5 percent. The injunction to provide the goods and services to which PLWHA are entitled is directed primarily at institutions, particularly the government. PLWHA, for example, should be able to receive continuing access to antiretroviral treatment and should be given supplementary nutritious foods. Where hospitals are overburdened and there is no public financing for orphanages or pensions for widows, care for the sick and support for orphans and widows are still most often provided by family members and relatives. Nonetheless, with the institutionalization of the struggle against AIDS, these tasks are increasingly recognized as the province of organizations and associations, which systematize the work of care and claim moral legitimacy for it.

Talk about AIDS

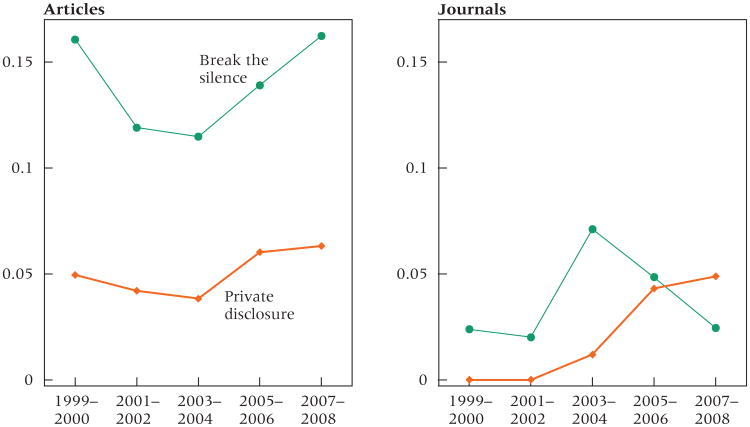

Like injunctions to care for people with AIDS, injunctions to talk freely and openly about AIDS were more frequent in the articles than in the journals (see Figure 1).9 In Figure 5, we examine the two sub-injunctions that fall under the category “talk about AIDS” by publicly discussing HIV and privately disclosing one's HIV status to loved ones. In a 2001 article about AIDS-related attitudes among youth, a Nation reporter writes:

There is a growing tendency to distance oneself from the reality of the pandemic, thinking that it affects ‘other people.’ This attitude is augmented in the Malawian culture. People do not disclose cases of death due to AIDS, a thing which could instill the reality of the disease among people. It appears that no one dies of AIDS in Malawi. They die of a short illness. Or they contract an unspecified fever, or vomit so much that they cannot drink. It appears to be taboo to explicitly disclose that someone has died of AIDS. (Mdalla 2001)

Figure 5. Prevalence of normative injunctions, by type, to “talk about AIDS” in newspaper articles and field journals, 1999–2008 (proportions of each type).

In both articles and journals, injunctions about private disclosure of a positive test result to family members, friends, and sexual partners often take the form of stories about supportive experiences related to telling loved ones about one's HIV status. For example, a journal from 2003 describes a conversation held on the way to the health clinic:

When going to the hospital to visit a friend, I met another friend, Jephter, who was traveling away from the clinic. I asked him [why he was] found there at the hospital on that day and he was so open to state his real problem because he told me that he had HIV…. I then asked him about what was the reaction from his parents when he told them that he tested positive for HIV and he told me that his parents told him that this was not the end of the lives and that they had to be loving each other and supporting him when he could have a problem. I also [asked] Graciano about his friends, from the time that he was tested positive and he told him that nothing has changed with his friends. (Diston_030614)

While the frequency of injunctions to privately disclose one's status is relatively stable in the articles over the period of study, such injunctions are virtually nonexistent in the conversational accounts before 2003, and then increase as discussions about testing become more commonplace, until by the end of the period this sub-injunction is discussed with about the same frequency in the journals and the articles.

With respect to public discussions about AIDS, the articles and journals diverge more markedly. The proportion of newspaper articles that mention an exhortation to break the silence about AIDS is far greater than the proportion that encourage people to privately disclose their HIV status. For example, in 2007–2008 the proportion of articles that mention public discussion about AIDS is 16 percent, compared with 6 percent for private disclosure. Early in the decade, the amount of newspaper coverage for each sub-injunction drops, but after 2003–2004 it generally rises through the end of the period. The difference in magnitude between injunctions about public versus private disclosure is less pronounced in the journals; the peak for breaking the silence, at 7 percent, occurs in 2003–2004.

In rural Malawi, “breaking the silence” means something different from what is meant in the media stories. Talking about AIDS in the abstract was commonplace, as people talked about the risks they faced and developed strategies to avoid infection (Watkins 2004). Publicly acknowledging oneself or others as HIV positive, however, was associated with conflict, discord, and antisocial behavior: when a death is attributed to “AIDS” in the journals, the usual supposition is that it was self-inflicted, akin to suicide, that the deceased killed himself or herself by willfully disregarding the dangers of sex in the time of AIDS (Ashforth and Watkins 2013). As further evidence that the local moralities revolve more around self-restraint and suppressing sexual passions, the subject is said to “choose death” by “moving” with many partners or by not being careful in selecting a sexual partner. As one man put it,

The world nowadays has changed. There are several diseases and some of them are the sexually transmitted diseases. Now if he keeps on falling in love with women unknowingly, he can commit suicide by getting infected with the diseases which are spread by sex. (Alice_040508)

In both Christian and Muslim traditions, suicide is a sin punishable by eternal damnation. Few people are willing to countenance such a future for those they loved or cared for, nor to embrace the shame and disgrace such a death would bring to their family among the living. This circumstance may help explain why circumspection is the standard when publicly naming a disease AIDS in local conversations.

Discussion and conclusion

During the decade covered by this study, 1999–2008, texts published in newspaper articles and texts of informal conversations in rural Malawi documented a shift from normative injunctions directed to the moral choices of individual actors to a focus on their choices as necessarily mediated through institutions. This shift coincided with the dissemination, through international funding and directives, of authoritative global knowledge and technologies of AIDS prevention and treatment within clinics, associations, and organizations. The definition of a good and responsible individual shifted from one who exercises moral restraint and suppresses sexual desire toward one who seeks technical information about one's body through scripted encounters with formal organizations. Biomedical interventions, by their very nature, require a large, formal organizational apparatus. The moral injunctions emanating from these institutions are performed in clinics by staff who test and treat. Biomedical approaches to the struggle against AIDS in general require a consistent—and in the case of HIV-positive individuals, lifelong—involvement with Western authoritative knowledge and medical expertise, embodied in bureaucratic institutions. In some cases these institutions antedated the growth of testing and treatment (campaigns against STDs in the colonial period and the later campaigns for safe motherhood and family planning, both of which required women to engage with a bureaucratic institution). The campaign against AIDS built on the template provided by the family planning movement (Cleland and Watkins 2006), but the enormous streams of funding that followed the declaration of AIDS as a global emergency stimulated even more nongovernmental institutions to confront the epidemic. We can thus connect the increasing institutionalization of the struggle against AIDS with the growth of “technologies of the self” as the main conduit for individual engagement with the struggle.

Our study demonstrated that the emerging technologies of the self have not gone uncontested. In the journals, which provide access to everyday life, the frequency of injunctions encouraging moral restraint of sexual behavior decreased relative to injunctions to seek biomedical care, but prevention of AIDS through moral restraint was never entirely superseded by recourse to institutional means. Injunctions about personal sexual morality and the need to seek out biomedical advice were debated, as we might expect, in the normal push–pull rhythm of casual local conversations. Although rural Malawians are well aware of the global script of appropriate actions to take in response to the epidemic, they did not consistently defer to the expertise of science and medicine to fight AIDS. The institutionalization of the struggle against AIDS, particularly its biomedicalization, was met with ambivalence in informal discussions. By contrast, because the media almost always adhere to the official line, dissenting injunctions are far less common in the articles. The two discourses, one individualized and the other institutionalized, exist side by side.

Debate and dissension about moral injunctions are most common during unsettled times, when new technologies emerge or new challenges must be confronted (Swidler 1986). It is thus likely that were our data to continue past 2008, we would see the upsurge in dissenting injunctions concerning HIV testing in the conversational journals subside, as occurred for dissension about condoms after 2001–2002. However, while the specific subjects that are debated have changed over time, the AIDS epidemic continues to present Malawians with a discrepant set of behavioral instructions and moral standards. For example, as local and international organizations disseminate information showing that male circumcision is highly protective against HIV, men must now decide whether to act on this information. In the context of rural Malawi, this is an emotionally charged choice, since male circumcision is strongly correlated with ethnic and religious identity (Dionne and Poulin 2013; Poulin and Muula 2011).

Through our analysis of almost a decade of newspaper articles and conversations from everyday life in Malawi, we uncovered a transformation of the discourse of the struggle against AIDS from concerns with individual moral responsibility to an orientation toward collective institutions, with rules and norms governing behavior and interactions. The embrace of these new institutionalized “technologies of the self,” however, is not unanimous, nor even particularly enthusiastic. Malawians have not been uniform in their desire to adopt new ways of being and behaving. Rather, they expressed ambivalence and even resisted global injunctions about the biomedical management of the struggle against AIDS (Angotti and Kaler 2013; Kaler and Watkins 2010). They continue to debate and question the expertise and authority of these institutions, even when this wisdom comes with the backing of powerful authorities. Malawians continue to consult their own local forms of expertise and the authority of their friends, relatives, and neighbors, rooted in experience and observation.

Acknowledgments

The conversational journals were collected in conjunction with the Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project, which received funding from NIH/NICHD (RO1-HD372-276; RO1- HD41713; RO1-HD050142-01), NICHD (R01-HD044228), and a PARC/Boettner/NICHD Pilot Award from the University of Pennsylvania. The collection of articles was made possible by funding from the National Science Foundation (Award 0825308) and the Canadian Institutes of Advanced Research. We appreciate the research assistance of Kondwani Chavula, Gloria Namadingo, Kim Yi Dionne, and Lynn Hancock. For additional assistance we are grateful to Agatha Bula and Chodziwadziwa Whiteson Kabudula. For helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper, we thank Crystal Biruk, Claire Decoteau, John Meyer, and Ann Swidler.

Appendix

Figure 1. Annual number of newspaper articles discussing AIDS and those including normative injunctions, 1999–2008.

Footnotes

We also read and coded 20 randomly selected articles from the weekend edition of The Nation, which includes a local-language newspaper written in chiChewa, called Tamvani. Because we found no apparent differences between the injunctions identified in the chiChewa articles and those in The Nation, nor in the relative frequency with which they appeared, we exclude the former from our analysis.

Because of technical problems in the field, we had a smaller absolute number of articles from 2008. We thus coded all 27 articles collected.

Information about the MLSFH can be found at www.malawi.pop.upenn.edu.

For additional information, see Watkins and Swidler (2009) and http://investinknowledge.org/projects/research/malawian_journals_project.

There were few journals from the Central region, so these were omitted.

Specifically, 39 percent of articles and 16 percent of conversational incidents did not contain an injunction. As an example, an article that reports changes in international HIV/AIDS funding would not contain an injunction about individual-level actions. It was considerably more likely for the discussions captured in informal conversations to reflect on things individuals could or should do.

All six co-authors evenly split the coding for the articles, and five co-authors evenly split the coding for the journals.

Dissenting injunctions about treating people with HIV/AIDS differently were rare, accounting for 8 percent of the journal injunctions and less than 1 percent of article injunctions in this category, so we do not distinguish them in Figure 4.

Dissenting injunctions advising people not to talk about AIDS or not to disclose their status were relatively uncommon, accounting for only 12 percent of journal injunctions and 2 percent of article injunctions in this category, so we do not distinguish them in Figure 5.

An earlier version was presented at the Annual Meetings of the American Sociological Association, Panel on Social Dimensions of AIDS, Denver, CO, 19 August 2012.

References

- Angotti Nicole. Testing differences: The implementation of western HIV testing norms in sub-Saharan Africa. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2012;14(4):365–378. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.644810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angotti Nicole, Dionne Kim Yi, Gaydosh Lauren. An offer you can't refuse? Provider-initiated HIV testing in antenatal clinics in rural Malawi. Health Policy and Planning. 2011;26(4):307–315. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angotti Nicole, Kaler Amy. The more you learn the less you know? Interpretive ambiguity across three modes of qualitative data. Demographic Research. 2013;28(33):951–980. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2013.28.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglewicz Philip, Kohler Hans-Peter. Overestimating HIV infection: The construction and accuracy of subjective probabilities of HIV infection in rural Malawi. Demographic Research. 2009;20(6):65–96. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2009.20.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong David, Gosling Ann, Weinman John, Marteau Theresa. The place of inter-rater reliability in qualitative research: An empirical study. Sociology. 1997;31(3):597–606. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth Adam, Watkins Susan Cotts. PSC Working Paper Series, PSC 13-07. Population Studies Center, University of Pennsylvania; Philadelphia: 2013. Narratives of death in the time of AIDS in rural Malawi. [Google Scholar]

- Black Donald. Moral Time. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chimbiri Agnes M. The condom is an ‘intruder’ in marriage: Evidence from rural Malawi. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64(5):1102–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirwa Wiseman Chijere. Sexually transmitted diseases in colonial Malawi. In: Setel Philip, Lewis Milton James, Lyons Maryinez., editors. Histories of Sexually Transmitted Diseases and HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press; 1999. pp. 143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Cleland John, Watkins Susan Cotts. Sex without birth or death: A comparison of two international humanitarian movements. In: Wells Jonathan CK, Strickland Simon, Laland Kevin., editors. Social Information Transmission and Human Biology. London: Taylor and Francis; 2006. pp. 207–224. [Google Scholar]

- Comaroff Jean. Beyond bare life: AIDS, (bio)politics, and the neoliberal order. Public Culture. 2007;19(1):197–219. [Google Scholar]

- Daneski Katharine, Higgs Paul, Morgan Myfanwy. From gluttony to obesity: Moral discourses on apoplexy and stroke. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2010;32(5):730–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilger Hansjörg. Targeting the empowered individual: Transnational policy making, the global economy of aid, and the limitations of biopower in Tanzania. In: Dilger Hansjörg, Kane Abdoulaye, Langwick Stacey A., editors. Medicine, Mobility, and Power in Global Africa: Transnational Health and Healing. Indiana University Press; 2012. pp. 60–91. [Google Scholar]

- Dionne Kim, Poulin Michelle. Ethnic identity, region, and attitudes towards male circumcision in a high HIV-prevalence country. Global Public Health. 2013;8(5):607–618. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2013.790988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas Mary. Risk and Blame: Essays in Cultural Theory. New York: Routledge; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Esacove Anne W. Love matches: Heteronormativity, modernity, and AIDS prevention in Malawi. Gender & Society. 2010;24(1):83–109. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault Michel. The History of Sexuality, Vol 1: An Introduction. New York: Vintage Books; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault Michel, Martin LH, Gutman H, Hutton PH. Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Frye Margaret. Bright futures in Malawi's new dawn: Educational aspirations as assertions of identity. American Journal of Sociology. 2012;117(6):1565–1624. doi: 10.1086/664542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray Ronald H, et al. Probability of HIV-1 transmission per coital act in monogamous, heterosexual, HIV-1-discordant couples in Rakai, Uganda. The Lancet. 2001;357:1149–1153. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan Thomas. World culture at the world's periphery: The role of small-scale transnational altruistic networks in the diffusion of world culture. paper presented at the American Sociological Association Annual Meetings; Denver, CO. 17–20 August.2012. [Google Scholar]

- Healy Kieran. Last Best Gifts: Altruism and the Market for Human Blood and Organs. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hitlin Steven. Moral Selves, Evil Selves: The Social Psychology of Conscience. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hitlin Steven, Stephen Vaisey., editors. Handbook of the Sociology of Morality. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes James P, et al. Determinants of per-coital-act HIV-1 infectivity among African HIV-1-serodiscordant couples. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2012;205(3):358–365. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Business Publications USA. Malawi: Strategic Information and Developments. Washington DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kaler Amy. ‘When they see money, they think it's life’: Money, modernity and morality in two sites in rural Malawi. Journal of Southern African Studies. 2006;32(2):335–349. [Google Scholar]

- Kaler Amy, Watkins Susan Cotts. Asking God about the date you will die: HIV testing as a zone of uncertainty in rural Malawi. Demographic Research. 2010;23(32):905–932. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2010.23.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalulu Yammie. You want AIDS? Go ahead. The Nation. 2000 no date. [Google Scholar]

- Klaits Frederick. The widow in blue: Blood and the morality of remembering in Bot swana's time of AIDS. Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 2005;75:46–62. [Google Scholar]

- Linden Ian, Linden Jane. Catholics, Peasants, and Chewa Resistance in Nyasaland 1889–1939. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe Brian M. Emerging Moral Vocabularies: The Creation and Establishment of Moral and Ethical Meanings. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lukes Steven. Moral Relativism. New York: Picador; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mdalla MacPherson Tadziwa. HIV and the productive age group. The Nation. 2001 Jul 4 [Google Scholar]

- Morfit N Simon. AIDS is money”: How donor preferences reconfigure local realities. World Development. 2011;39(1):64–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mykhalovskiy Eric, McCoy Liza, Bresalier Michael. Compliance/adherence, HIV, and the critique of medical power. Social Theory & Health. 2004;2(4):315–340. [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS Commission. Organizations working with AIDS in Malawi, 2005 update. Lilongwe, Malawi: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS Commission. Organizations working with AIDS in Malawi: Update. Lilongwe, Malawi: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Neuendorf Kimberly. The Content Analysis Guidebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen Vinh-Kim. Antiretroviral globalism, biopolitics, and therapeutic citizenship. In: Ong Aihwa, Collier Stephen J., editors. Global Assemblages: Technology, Politics, and Ethics as Anthropological Problems. Malden: Blackwell Publishing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen VinhKim. The Republic of Therapy: Triage and Sovereignty in West Africa's Time of AIDS. Durham: Duke University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nyoni Amos. The positive story of Fred Purse. The Nation. 2004 no date. [Google Scholar]

- Poletta Francesca. It Was Like a Fever: Storytelling in Protest and Politics. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Poulin Michelle, Muula Adamson. An inquiry into the uneven distribution of women's HIV infection in rural Malawi. Demographic Research. 2011;25(28):869–902. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2011.25.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins S. WISER and CRESP Symposium on Life and Death in the Time of AIDS. The South African Experience; Johannesburg: 2004. Oct, ARVs and the passage from ‘near death’ to ‘new life’: AIDS activism and the responsibilized citizen in South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson Rachel S. From population to HIV: The organizational and structural determinants of HIV outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2011;14(Suppl. 2):S6. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-14-S2-S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth Leslie T. The moral construction of risk. In: Hitlin Steven, Vaisey Stephen., editors. The Handbook of the Sociology of Morality. New York: Springer; 2010. pp. 469–484. [Google Scholar]

- Saguy Abigail. What's Wrong with Fat? New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Setel Philip W, Lewis Milton James, Maryinez Lyons., editors. Histories of Sexually Transmitted Diseases and HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Shilts Randy. And the Band Played On: Politics, People and the AIDS Epidemic. New York: St. Martin's Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Christian. Moral, Believing Animals: Human Personhood and Culture. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Swidler Ann. Culture in action: Symbols and strategies. American Sociological Review. 1986;51(2):273–286. [Google Scholar]

- Swidler Ann, Watkins Susan Cotts. ‘Teach a man to fish’: The sustainability doctrine and its social consequences. World Development. 2009;37(7):1182–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavory Iddo. The question of moral action: A formalist position. Sociological Theory. 2011;29(4):272–293. [Google Scholar]

- Tavory Iddo, Swidler Ann. Condom semiotics: Meaning and condom use in rural Malawi. American Sociological Review. 2009;74:171–189. [Google Scholar]

- Tawfik Linda, Watkins Susan Cotts. Sex in Geneva, sex in Lilongwe, sex in Balaka. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64:1090–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tayanjah-Phiri Francis. Diocese celebrating with gains in AIDS fight. The Nation. 2005 Jun 29 [Google Scholar]

- Toufexis Spiros. Artillery against AIDS. The Nation. 2002 no date. [Google Scholar]

- Trinitapoli Jenny. Religious teachings and influences on the ABCs of HIV prevention in Malawi. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69(2):199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner Bryan. The Body and Society: Explorations in Social Theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wangel Ann-Marie. Dissertation for Master of Science in Public Health in Developing Countries. London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 1995. A conspiracy of silence? [Google Scholar]

- Watkins Susan Cotts. Navigating the AIDS epidemic in rural Malawi. Population and Development Review. 2004;30(4):673–705. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins Susan Cotts, Swidler Ann. Hearsay ethnography: Conversational journals as a method for studying culture in action. Poetics. 2009;37(2):162–184. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins Susan Cotts, Swidler Ann. Working misunderstandings: Donors, brokers, and villagers in Africa's AIDS industry. Population and Development Review. 2012;38(Suppl):197–218. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins Susan Cotts, Swidler Ann, Hannan Thomas. Outsourcing social transformation: Development NGOs as organizations. Annual Review of Sociology. 2012;38:285–315. [Google Scholar]

- Zelizer Viviana. The Purchase of Intimacy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zulu Eliya Msiyaphazi. PhD dissertation. University of Pennsylvania; 1996. Sociocultural factors affecting reproductive behavior in Malawi. [Google Scholar]