Abstract

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are environmental pollutants associated with non-alcoholic-steatohepatitis (NASH), diabetes, and obesity. We previously demonstrated that the PCB mixture, Aroclor 1260, induced steatohepatitis and activated nuclear receptors in a diet-induced obesity mouse model. This study aims to evaluate PCB interactions with the pregnane-xenobiotic receptor (Pxr: Nr1i2) and constitutive androstane receptor (Car: Nr1i3) in NASH. Wild type C57Bl/6 (WT), Pxr−/− and Car−/− mice were fed the high fat diet (42% milk fat) and exposed to a single dose of Aroclor 1260 (20 mg/kg) in this 12-week study. Metabolic phenotyping and analysis of serum, liver, and adipose was performed. Steatohepatitis was pathologically similar in all Aroclor-exposed groups, while Pxr−/− mice displayed higher basal pro-inflammatory cytokine levels. Pxr repressed Car expression as evident by increased basal Car/Cyp2b10 expression in Pxr−/− mice. Both Pxr−/− and Car−/− mice showed decreased basal respiratory exchange rate (RER) consistent with preferential lipid metabolism. Aroclor increased RER and carbohydrate metabolism, associated with increased light cycle activity in both knockouts, and decreased food consumption in the Car−/− mice. Aroclor exposure improved insulin sensitivity in WT mice but not glucose tolerance. The Aroclor-exposed, Pxr−/− mice displayed increased gluconeogenic gene expression. Lipid-oxidative gene expression was higher in WT and Pxr−/− mice although RER was not changed, suggesting PCB-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction. Therefore, Pxr and Car regulated inflammation, behavior, and energy metabolism in PCB-mediated NASH. Future studies should address the ‘off-target’ effects of PCBs in steatohepatitis.

Keywords: Aroclor 1260, PCBs, nuclear receptors, energy metabolism, steatohepatitis

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) refers to a pathological spectrum of physiological disorders ranging from lipid accumulation in hepatocytes (steatosis) to the development of superimposed inflammation, resulting in non-alcoholic-steatohepatitis (NASH), and ultimately fibrosis and cirrhosis. NAFLD is associated with multiple metabolic derangements and systemic responses, including: (1) obesity and its related sedentary lifestyle behaviors; (2) hepatic responses primarily steatosis (possibly a reflection of abnormal lipid and carbohydrate metabolism), inflammation and fibrosis; and (3) diabetes and insulin resistance. Typically, these metabolic derangements occur consecutively such that excessive caloric intake coupled with decreased exercise leads to hepatic steatosis and inflammation, resulting in worsened insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome. However, these phenomena can become dissociated wherein lean patients may develop NASH; only some NASH patients develop diabetes; and some patients develop only steatosis and never progress to steatohepatitis and fibrosis. A ‘two-hit’ theory has been proposed and environmental chemicals may represent the second hit.

Historically, NAFLD and NASH were attributed, in part, to the inappropriate over- or under-activation of nuclear receptors involved in endobiotic metabolism, including the liver-X-receptor (Lxr), farnesoid-X-receptor (Fxr), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (Ppars) that regulate cholesterol, bile acid and lipid metabolism respectively (Mangelsdorf et al., 1995; Novac and Heinzel, 2004). The role of hepatic receptors involved in xenobiotic detoxification, namely the pregnane-xenobiotic receptor (Pxr), constitutive androstane receptor (Car), and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Ahr) have more recently been associated with NAFLD/NASH. Although thought to be involved in xenobiotic metabolism, receptor over-activation or antagonism may lead to metabolic diseases (Kliewer et al., 2002; Konno et al., 2008; Merrell and Cherrington, 2011; Moya et al., 2010; Wei et al., 2000). Recent studies have demonstrated these receptors’ role in energy homeostasis, including regulation of lipid and carbohydrate metabolism (Konno et al., 2008; Wada et al., 2009). Car has been considered to be an anti-obesity nuclear receptor since its activation improves insulin sensitivity and ameliorates diabetes and NAFLD (Dong et al., 2009; Gao et al., 2009). Furthermore, Pxr and Car activation also suppresses gluconeogenesis by decreasing gluconeogenic gene expression most likely through the sequestration of forkhead boxO1 (Foxo1) (Kodama et al., 2004, 2007). The reported role of Pxr in obesity is controversial with some studies demonstrating obesity-protecting effects of Pxr (Ma and Liu, 2012) and others illustrating that ablating Pxr alleviated diet-induced obesity (Fernandez et al., 2013; Spruiell et al., 2014). Car and Pxr ligands vary from therapeutic drugs to industrial chemicals and environmental pollutants including polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) (Handschin and Meyer, 2003; Hernandez et al., 2009).

PCBs are persistent organic pollutants manufactured in the 1930s–70s and used in industrial applications. Epidemiologic studies have correlated PCB exposure with liver disease, type 2 diabetes, obesity, and related cardiovascular disorders (Silverstone et al., 2012). Moreover, 100% of the adult National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) participants had detectable circulating PCB levels with PCB 153 having the highest median serum concentration (Cave et al., 2010). PCB exposures were also correlated with elevation in liver enzymes such as alanine transaminase (ALT) in the NHANES participants. Monsanto Company, the only PCB manufacturer in North America, produced PCB mixtures under the brand name ‘Aroclor’ at its manufacturing plant located in Anniston, Alabama. Incidences of high-level environmental contamination during PCB production at the time resulted in increased PCB body burden in the Anniston residents till today. Aroclor 1260 (60% chlorine by weight) was one of the early PCB mixtures produced and it was later replaced by other PCB mixtures with lower chlorine content such as 1254, 1248, and 1242. Although being banned for over 30 years, highly chlorinated PCBs continue to persist in the environment due to their high thermodynamic stability and limited metabolism. Therefore, the profile of bio-accumulated PCBs closely resembles Aroclor 1260. Currently, PCB exposure is thought to occur primarily through ingestion of PCB contaminated food (Schecter et al., 2010), and thus, Aroclor 1260 was selected for this study to reflect current exposure paradigms.

Our initial studies in a diet-induced obesity model demonstrated that Aroclor 1260 exposure had modest effects on mice fed a control diet, but induced steatohepatitis in mice fed a high fat diet (HFD) (Wahlang et al., 2014b). Paradoxically, Aroclor 1260 exposure did not exacerbate obesity/diabetes in HFD-fed mice. Although the mode of action of non-dioxin-like PCBs is unknown in NASH, Aroclor 1260 activates nuclear receptors in both mice and humans (Wahlang et al., 2014a). Because Car activation (Dong et al., 2009; Gao et al., 2009) and Pxr inhibition (Fernandez et al., 2013) were previously shown to be protective against NAFLD, we hypothesized that: (1) Car ablation would worsen steatohepatitis in Aroclor 1260-exposed, HFD-fed mice, and that (2) Pxr ablation would be protective against steatohepatitis under these conditions. Thus, a more detailed study building on our previous work was performed using Pxr and Car single knockout mice fed HFD with or without environmentally relevant Aroclor 1260 exposures. Mechanistic understanding of PCB mode(s) of action could lead to new nuclear receptor-targeted therapies for NASH in exposed populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and diets

The animal protocol was approved by the University of Louisville Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Eight week-old wild type male C57Bl/6 J mice (WT), Car−/− and Pxr−/− mice (Taconic, Hudson, New York) were divided into 6 study groups (n = 10) based on Aroclor 1260 exposure utilizing a 2 × 3 design. Taconic developed the knockout mice in collaboration with CXR Biosciences. The Car−/− and Pxr−/− mice were generated by crossing a CAR and a PXR humanized mouse line, respectively, with a PhiC31 deleter mouse. All mice were fed a HFD (42% kCal from fat; TD.88137 Harlan Teklad) during this 12-week study. On week 1, Aroclor 1260 (AccuStandard, Connecticut) was administered in corn oil by oral gavage (vs corn oil alone) at 20 mg/kg. This dose was designed to mimic the highest human PCB exposures seen in the PCB-exposed Anniston cohort. Mice were housed in a temperature- and light-controlled room (12-h light; 12-h dark) with food and water ad libitum. During weeks 8–9, mice were placed in metabolic chambers (PhenoMaster, TSE systems, Chesterfield, Missouri) overnight to assess food/drink consumption and physical activity. A glucose tolerance test (GTT) was performed at week 11, and the animals were euthanized (ketamine/xylazine, 100/20 mg/kg body weight [BW], i.p.) at the end of week 12. Prior to euthanasia, the animals were analyzed for body fat composition by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scanning (Lunar PIXImus densitometer, Wisconsin). Thus, 6 different groups were evaluated; WT, WT+Aroclor 1260, Car−/−, Car−/−+Aroclor 1260, Pxr−/−, Pxr−/−+Aroclor 1260.

Histological studies

Sections from the liver and adipose tissue were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin for routine histological examination. Tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) or for chloroacetate esterase activity (CAE, Naphthol AS-D Chloroacetate [Specific Esterase] Kit, Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri) and examined by light microscopy. Photomicrographic images were captured using a high-resolution digital scanner at 10× and 40× magnification. After H&E staining, adipocyte size was measured using Image J software version 1.47 (NIH, Bethesda, Maryland).

Glucose tolerance test

On the day of the test, mice were fasted for 6 h (7 a.m.–1 p.m.), and fasting blood glucose levels were measured with a hand-held glucometer (ACCU-CHECK Aviva, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) using 1–2 µl blood via tail snip. Glucose was then administered (1 mg glucose/g BW, sterile saline, i.p.), and blood glucose was measured at 5, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min post-injection. Diabetic parameters including insulin resistance and insulin sensitivity were assessed. Insulin resistance was calculated by the homeostasis model assessment using the formula: homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) = fasting glucose (mg/dl) × fasting insulin (µU/ml)/405. Insulin sensitivity was assessed using the quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI) as follows: QUICKI = 1 / [log (fasting insulin) + log (fasting glucose)], and HOMA-β = [(360 × fasting insulin)/ (fasting glucose-63)] %.

Cytokine and adipokine measurement

The Milliplex Serum Cytokine and Adipokine Kits (Millipore Corp, Billerica, Massachusetts) were utilized to measure plasma cytokines (tumor necrosis factor alpha [Tnfα], interleukin-2 [IL-2], interferon gamma [Ifnγ], IL-17, macrophage chemoattractant protein-1 [Mcp-1], and macrophage inflammatory protein-1α [Mip-1α]), insulin, adipokines (adiponectin, leptin), and tissue plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (tPAI-1) on the Luminex IS 100 system (Luminex Corp, Austin, Texas), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Plasma ALT and aspartate transaminase (AST) activities, low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, triglycerides, and cholesterol levels were measured with the Piccolo Xpress Chemistry Analyzer using Lipid Panel Plus reagent discs (Abaxis, Union City, California).

Measurement of hepatic triglyceride and cholesterol content

Mouse livers were washed in neutral 1X phosphate buffered saline and pulverized. Hepatic lipids were extracted by an aqueous solution of chloroform and methanol, according to the Bligh and Dyer (1959) method, dried using nitrogen, and resuspended in 5% lipid-free bovine serum albumin. Triglycerides and cholesterol were quantified using the Cobas Mira Plus automated chemical analyzer. The reagents employed for the assay were L-Type Triglyceride M (Wako Diagnostics, Richmond, Virginia) and Infinity Cholesterol Liquid Stable Reagent (Fisher Diagnostics, Middletown, Virginia) for triglycerides and cholesterol, respectively.

Real-time PCR

Mouse liver samples were homogenized and total RNA was extracted using the RNA-STAT 60 protocol (Tel-Test, Austin, Texas). RNA purity and quantity were assessed with the Nanodrop (ND-1000, Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, Delaware) using the ND-1000 V3.8.1 software. cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, California). PCR was performed on the Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus Real-time PCR Systems using the Taqman Universal PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, California). Primer sequences from Taqman Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California) were as follows: tumor necrosis factor alpha (Tnfα); (Mm00443258_m1), fatty acid synthase (Fas); (Mm00662319_m1), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (Pparα); (Mm00440939_m1), carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1A (Cpt1a); (Mm01231183_m1), cytochrome P450s [Cyp4a10 (Mm02601690_gH), Cyp2b10 (Mm01972453_s1), Cyp3a11 (Mm007731567_m1), Cyp1a2 (Mm00487224_m1)], UDP glucuronosyltransferase 1 family, polypeptide A1 (Ugt1a1); (Mm02603337_m1), Cd36 (Mm01135198_m1), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxy kinase (Pepck-1); (Mm01247058_m1), Pparγ (Mm01184322_m1), stearoyl coenzyme A desaturase1 (Scd1); (Mm00772290_m1), fatty acid binding protein 1 (Fabp1); (Mm00444340_m1), IL-6; (Mm00446190_m1), chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3 (Mip-1); (Mm00441258_m1), chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 8 (Mcp-2); (Mm01297183_m1), Pxr (Mm01344139_m1), Car (Mm01283978_m1), patatin-like phospholipase domain containing protein-2 (Pnpla2); (Mm00503040_m1), solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose transporter), member 2 (Glut-2), (Mm00446229_m1), solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose transporter), member 4 (Glut-4), (Mm01245502_m1), glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase); (Mm00839363_m1), insulin induced gene 1 (Insig-1) (Mm00463389_m1), insulin induced gene 2 (Insig-2) (Mm01308255_m1) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gadph); (4352932E). The levels of mRNA were normalized relative to the amount of Gadph mRNA, and expression levels in mice fed control diet and administered vehicle were set at 1. Gene expression levels were calculated according to the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Immunoblots

Frozen liver samples (0.1 g) were homogenized in 0.5 ml radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium vanadate, and 1% w/w Triton X-100 w/v) containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, protease and phosphatase (tyrosine and serine/threonine) inhibitor cocktails (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri). Lysates were sonicated at 4°C for 4 h and subsequently centrifuged for 5 min at 16 000 g. The protein concentration of the supernatants was determined using the Bicinchoninic Acid Protein Assay Kit (Sigma Aldrich). Total protein was diluted in RIPA buffer and mixed with 4 × sample loading buffer (250 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 20% β-mercaptoethanol w/v, 40% glycerol, and 0.05% bromophenol blue) and incubated at 95°C for 5 min. The samples were loaded onto SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, California), followed by electrophoresis and Western blotting onto polyvinylidene difluoridemembranes (Immobilon-P; Millipore Corp, Billerica, Massachusetts). Antibodies against Car (Abcam, Cambridge, Massachusetts), Pxr (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, Texas), β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, Massachusetts), and Gapdh (Cell Signaling Technology) were used at dilutions recommended by the suppliers. Horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies were obtained from Abcam and Cell Signaling Technology. Chemiluminescence detection was performed using the Pierce ECL2 western blotting substrate reagents (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, Delaware). Densitometric quantitation was performed with the Image Lab software (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were conducted between the groups based on genotype (e.g. WT vs Car−/−, Car−/− vs Pxr−/−, and Pxr−/− vs WT, or Aroclor treatment (e.g. WT vs WT + Aroclor 1260, Car−/− vs Car−/− + Aroclor 1260, and Pxr−/− vs Pxr−/− + Aroclor 1260) or on both (WT+Aroclor 1260 vs Car−/−+Aroclor 1260, Car−/−+Aroclor 1260 vs Pxr−/−+Aroclor 1260, and Pxr−/−+Aroclor 1260 vs WT+Aroclor 1260). In the analysis, the P-value was calculated using 2 sample t test for comparisons (Dmitrienko et al., 2005). Results were declared statistically significant at significance level of 5% without adjusting for multiple comparisons due to the exploratory nature of the study. All calculations were performed with SAS statistical software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Receptor Expression and Activity

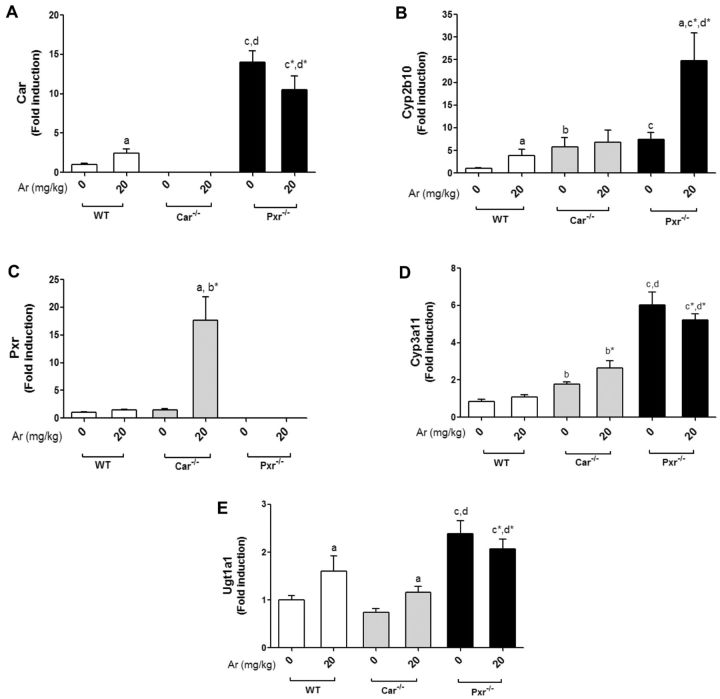

Hepatic Car mRNA levels were measured, and as anticipated, the Car−/− mice did not express Car (Figure 1A). Pxr appeared to repress Car expression as Pxr−/− mice had increased basal Car expression versus WT and Car−/− mice. Aroclor 1260 increased Car expression only in WT mice (approximately 2-fold). Basal mRNA levels of Cyp2b10, a Car target gene, were upregulated to a similar degree in both the Car−/− and Pxr−/− groups (Figure 1B). Aroclor 1260 slightly increased Cyp2b10 expression in WT mice, but markedly upregulated Cyp2b10 expression in Pxr−/− mice. In Pxr−/− mice, the increased basal and Aroclor-stimulated Cyp2b10 expression was probably due to loss of Pxr-mediated Car repression. The increased basal Cyp2b10 expression in Car−/− mice indicated that a compensatory mechanism was driving target gene expression in the absence of Car. Notably, Aroclor 1260 did not induce Cyp2b10 in the Car−/− group.

FIG. 1.

Aroclor 1260 exposure altered hepatic expression of Car and Pxr target genes. Hepatic mRNA expressions for (A), Car, (B) Cyp2b10 (Car target gene), (C) Pxr, (D) Cyp3a11 (Pxr target gene), and (E) Ugt1a1 (Pxr/Car target gene). Values are mean ± SEM, P < .05, a- Δ due to Aroclor 1260 exposure within genotype, b, b*- Δ between WT and Car−/− without or with Aroclor 1260 exposure, c, c*- Δ between WT and Pxr−/− without or with Aroclor 1260 exposure, d, d*- Δ between Car and Pxr ablation without or with Aroclor 1260 exposure.

Hepatic expression of Pxr was also evaluated, and as expected, Pxr expression was absent in Pxr−/− mice (Figure 1C). Contrary to Car, basal Pxr expression was not increased in Car−/−. Thus, while Pxr repressed Car expression, Car did not reciprocally repress Pxr expression. Aroclor 1260 did not induce Pxr expression in WT mice. In contrast, Aroclor 1260 exposure increased Pxr expression (approximately 17-fold) in the Car−/− mice. Akin to basal Cyp2b10 expression, the basal Cyp3a11 (Pxr target gene) expression levels were higher in both the knockout groups (Figure 1D), although it was greatest in Pxr−/− mice, indicating compensatory mechanisms with Pxr ablation. There was a trend towards Aroclor-induced Cyp3a11 induction in WT and Car−/− mice. In addition to Cyp3a11, the hepatic expression of Ugt1a1 (a predominant Pxr target gene which also happens to be a Car target gene) was measured (Figure 1E). Similar to Cyp3a11, basal Ugt1a1 expression was highest in the Pxr−/− mice, indicating a compensatory mechanism was upregulating Pxr target gene expression in the absence of Pxr. Aroclor 1260 induced Ugt1a1 in both WT and Car−/−, but not in Pxr−/− mice. Additionally, Car and Pxr proteins were also absent in the respective knockout mice as assessed by immunoblots (Supplementary Figure S1).

Apart from Car and Pxr targets, the hepatic expression of Cyp1a2, an AhR target gene, was also measured (Supplementary Figure S1). There were no significant differences in Cyp1a2 mRNA levels between the groups, indicating that the AhR was not activated by Aroclor 1260 at the dose used. Also, Car/Pxr ablation had no effect on AhR target gene expression. Overall, the results indicated that Pxr and Car expression were absent in the respective knockout groups, although a compensatory upregulation occurred in at least some target genes of these receptors. Pxr appeared to repress Car expression, and Aroclor 1260 was a better inducer of Car than Pxr targets. The relationships between PCBs and nuclear receptors Car and Pxr were more complicated than anticipated, due to the unexpected finding of Pxr-mediated Car suppression.

Bodyweight and Composition

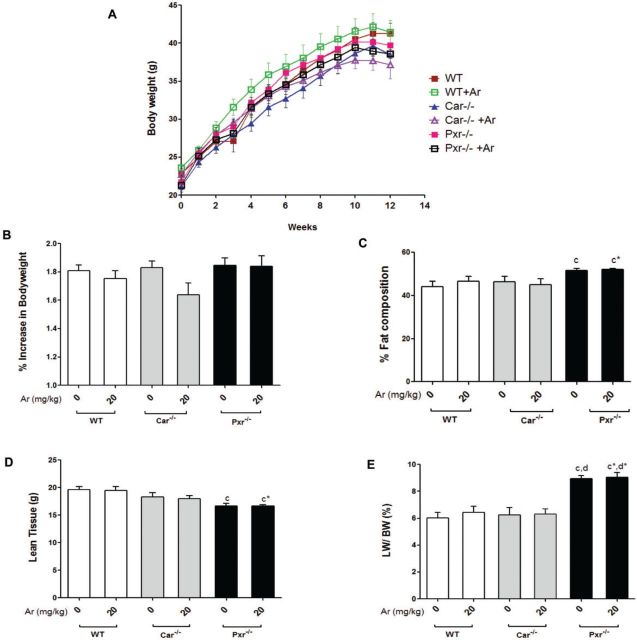

PCB exposures have been associated with changes in bodyweight and fat composition (Wahlang et al., 2014b). All groups experienced bodyweight gain until week 11 (Figure 2A). Aroclor 1260 exposure did not affect the % increase in bodyweight gain in WT or Pxr−/− groups (Figure 2B). However, Aroclor 1260 exposure in Car−/− mice was associated with a trend towards reduced bodyweight gain (P = .058). Because all groups were on HFD feeding, the average % body fat composition among the animals was approximately 40% (Figure 2C). Pxr ablation increased % body fat composition and decreased lean body mass, irrespective of Aroclor 1260 exposure (Figs. 2C and D). The Pxr−/− groups showed higher liver mass and LW/BW when compared with any other group (Figure 2E). There was no difference in the mean adipocyte size (µm2) in any of the groups irrespective of Aroclor 1260 exposure (Supplementary Figure S2). Ad libitum food consumption per mouse per day (g) was calculated over the 12-week period and there were no significant changes (Supplementary Figure S2). In summary, neither genotype nor Aroclor 1260 exposure significantly changed overall BW but genotype affected body composition.

FIG. 2.

Effects of Aroclor 1260 exposure on BW, visceral adiposity, and food consumption in Car−/− and Pxr−/− mice. A, Increase in BW with time for C57BL/6 (WT), Car−/− and Pxr−/− mice (n = 10) taken weekly from week 1 to 12. B, The % increase in BW gain with time was calculated and the BW at week 1 was taken as 100%. C, % fat composition and (D) lean tissue mass (g) were measured using the DEXA scanner. E, Livers were weighed at euthanasia and the liver to bodyweight ratio was calculated. Values are mean ± SEM, P < .05, a- Δ due to Aroclor 1260 exposure within genotype, b, b*- Δ between WT and Car−/− without or with Aroclor 1260 exposure, c, c*- Δ between WT and Pxr−/− without or with Aroclor 1260 exposure, d, d*- Δ between Car and Pxr ablation without or with Aroclor 1260 exposure.

Metabolic Phenotyping

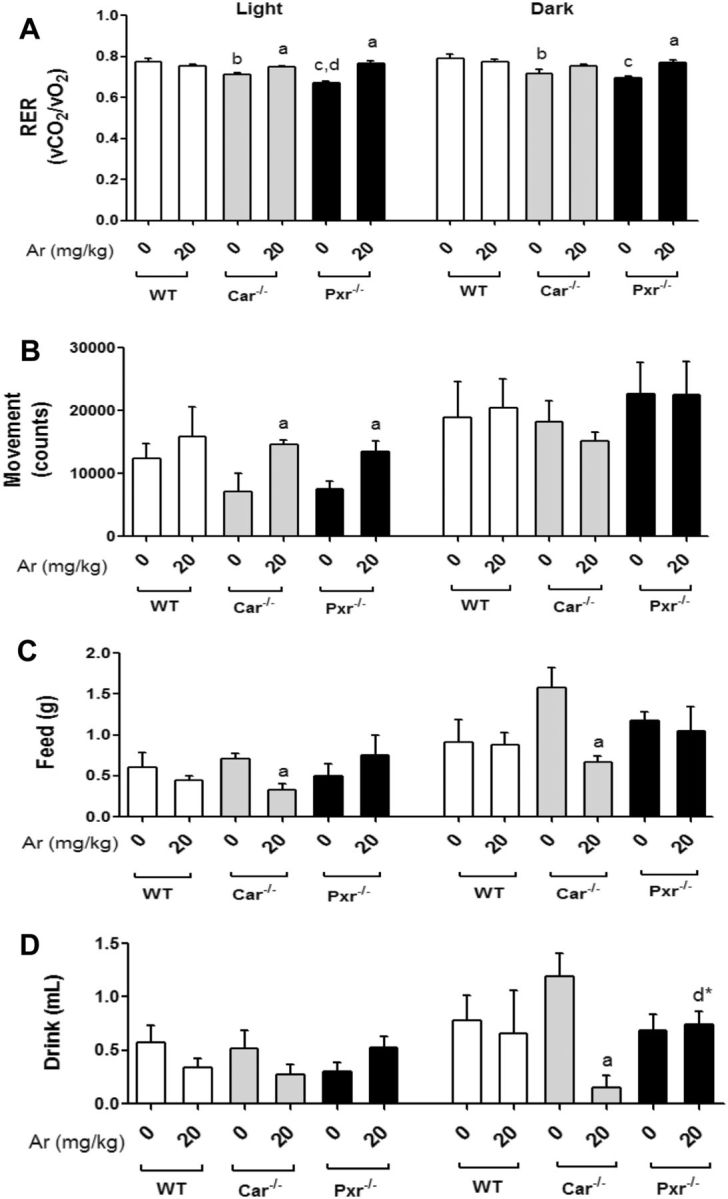

To assess the effects of PCB exposure on whole-body energy metabolism, animals were placed in metabolic cages at the beginning of week 8 for metabolic assessment (Figure 3A). Oxygen consumption (vO2) and carbon dioxide production (vCO2) were monitored and the respiratory exchange rate (RER, vCO2/vO2) was calculated. The total energy expenditure (EE) was computed using the following modified Weir equation: EE = (3.815 + 1.232 × RER) × VO2 (Weir, 1949). There were no differences in the EE between the groups (Supplementary Figure S3), although there was a trend towards decreased EE in the Aroclor 1260-exposed Car−/− versus Car−/− in the dark cycle (P = .052). The unexposed knockout groups displayed a lower RER (approximately 0.70) than WT, but the light-cycle RER was lower in Pxr−/− than Car−/− (Figure 3A). Aroclor 1260 exposure increased RER in both knockout groups in the light cycle. Additionally, the Aroclor 1260-exposed Pxr−/− mice also had a higher RER versus unexposed in the dark cycle. There was no difference in the RER in WT mice with or without Aroclor 1260 exposure.

FIG. 3.

Assessment of respiration exchange rate and EE utilizing metabolic cages. A, The RER which is the ratio of CO2 exhaled to O2 consumed was calculated. B, The total movement (counts) was measured as an indicator of physical activity. The average amount of (C) food (g)/day and (D) water (ml)/day consumed per group was measured. Values are mean ± SEM, P < .05, a- Δ due to Aroclor 1260 exposure within genotype, b, b*- Δ between WT and Car−/− without or with Aroclor 1260 exposure, c, c*- Δ between WT and Pxr−/− without or with Aroclor 1260 exposure, d, d*- Δ between Car and Pxr ablation without or with Aroclor 1260 exposure.

Physical activity was also assessed by beam breaks in the metabolic chambers. The Car−/− and Pxr−/− mice exposed to Aroclor 1260 showed increased movement/physical activity during the light cycle relative to the unexposed knockout mice (Figure 3B). Increased activity is known to increase carbohydrate utilization and this may be responsible for the observed Aroclor 1260-induced increase in light phase RER in the knockout groups. Furthermore, the Car−/− mice exposed to Aroclor 1260 demonstrated lower food consumption in both cycles and decreased drink consumption in the dark cycle versus any other group (Figs. 3C and D). This may account for the trend towards decreased % BW gain observed in the Car−/− group (Figure 2B). These metabolic phenotyping studies were critically important, because they revealed significant Aroclor effects on obesity-related behaviors and whole body energy metabolism which were not apparent on more crude measurements such as BW.

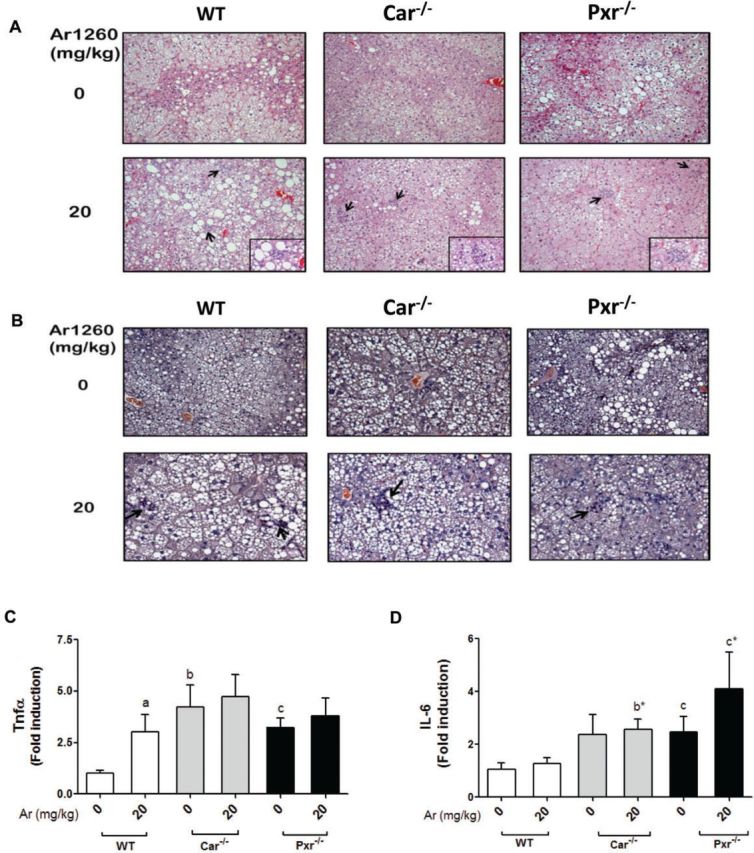

Steatohepatitis Assessment

Hepatic steatosis was assessed histologically, and biochemically via measurement of hepatic triglycerides and cholesterol. Hepatic necro-inflammation was assessed by serum aminotransferase activity, histology, serum cytokine levels, and hepatic cytokine gene expression. All groups developed steatosis by the end of the study due to HFD. The degree of steatosis was not altered by genotype or Aroclor 1260 exposure as assessed by histology (Figure 4A), or biochemical measurement of hepatic triglycerides or cholesterol (Supplementary Figure S4). This was somewhat surprising as the Pxr−/− mice had a higher body fat composition and higher liver weight (LW) to BW ratio. Serum lipids were also measured, including cholesterol and triglycerides (Supplementary Figure S4). Serum cholesterol levels were not altered between the groups whereas Aroclor 1260 exposure reduced serum triglycerides levels in the WT group.

FIG. 4.

Aroclor 1260 exposure caused steatohepatitis in WT, Car−/− and Pxr−/− mice. A, H&E staining of hepatic sections established the occurrence of centrilobular hepatocellular hypertrophy, karyomegaly, and multinucleate hepatocytes in the Aroclor 1260-exposed groups. B, CAE staining demonstrated neutrophil infiltration in the Aroclor 1260-exposed groups. Hepatic mRNA expression for (C) Tnfα and (D) IL-6. Values are mean ± SEM, P < .05, a- Δ due to Aroclor 1260 exposure within genotype, b, b*- Δ between WT and Car−/− without or with Aroclor 1260 exposure, c, c*- Δ between WT and Pxr−/− without or with Aroclor 1260 exposure, d, d*- Δ between Car and Pxr ablation without or with Aroclor 1260 exposure.

Scattered inflammatory foci with neutrophil infiltration were observed on H & E (Figure 4A) and CAE (Figure 4B) stained liver sections in all exposed groups. Although exposure to Aroclor 1260 caused liver injury (H & E and CAE staining), serum ALT (Supplementary Figure S5) and AST activities were not significantly elevated. Steatohepatitis with normal liver enzymes has been previously reported in other toxicant-associated steatohepatitis studies (Wahlang et al., 2013). Hepatic Tnfα expression (Figure 4C) and serum Tnfα levels (Supplementary Figure S6) were significantly increased with Aroclor 1260 exposure only in WT mice indicating that the presence of both nuclear receptors is required for this effect. However, both unexposed Pxr−/− and Car−/− mice had increased basal hepatic Tnfα expression (Figure 4C) while only Pxr−/− mice had increased basal serum Tnfα (Supplementary Figure S6) compared with WT. Similar to Tnfα, hepatic IL-6 expression was higher in the knockout groups than the WT group (Figure 4D). Aroclor 1260 exposure increased serum IL-2 and Ifnγ only in WT mice, while IL-2 was higher in the Pxr−/− group, irrespective of Aroclor exposure (Supplementary Figure S6). Neither hepatic expression of Mip-1α/Mcp-2 (data not shown) nor serum levels of Mip-1α/Mcp-1 differed between groups (Supplementary Figure S6). Likewise serum IL-17 and tPAI-1 did not differ between groups (Supplementary Figure S6). Thus, Aroclor 1260 was a ‘second hit’ mediating the transition from diet-induced steatosis to steatohepatitis, confirming the results of our previous study (Wahlang et al., 2014b). Notably, presence of both Pxr and Car were required for Aroclor-induced inflammation because the knockout groups, particularly Pxr−/− mice, had increased basal pro-inflammatory cytokines, indicating an anti-inflammatory role of this receptor.

Carbohydrate Metabolism

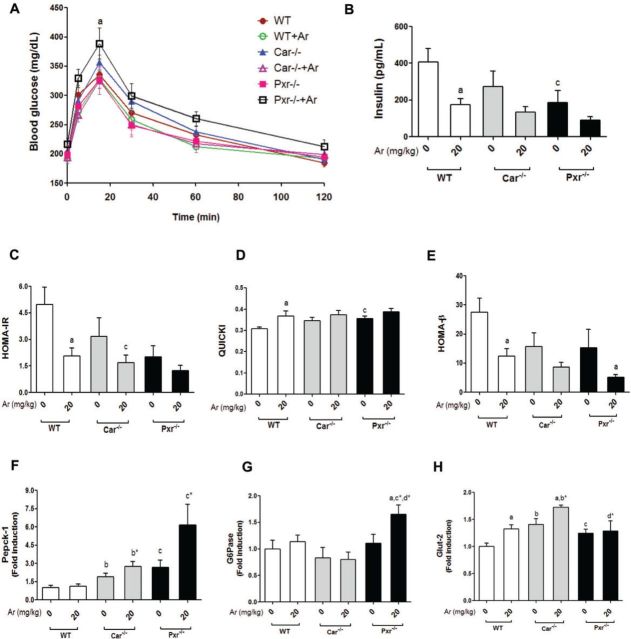

The metabolic chamber studies demonstrated altered RER, suggesting altered carbohydrate metabolism. Therefore, glucose tolerance, insulin resistance/sensitivity, adipokines, pancreatic insulin secretion, and hepatic gluconeogenesis/glucose transporters were measured and the results revealed widespread metabolic disruption by Aroclor 1260 in steatohepatitis. Fasting blood glucose levels were measured prior to performing the GTT. There were no differences in fasting blood glucose levels between the 6 groups (data not shown). GTT was then performed (Figure 5A) and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated from the GTT curves to measure the degree of glucose uptake and clearance in the fed state (data not shown). Aroclor 1260 exposure had no effect on AUC in WT and Car−/− groups. In contrast, Aroclor 1260 exposure significantly increased the AUC in Pxr−/− mice. Insulin resistance and sensitivity were determined by fasting insulin level/HOMA-IR and QUICKI respectively. Aroclor 1260 decreased fasting insulin (Figure 5B) and HOMA-IR (Figure 5C) in WT mice. These changes corresponded to an increase in QUICKI (Figure 5D) indicating that Aroclor decreased insulin resistance and improved insulin sensitivity although glucose tolerance was unchanged. Several other genotype-related effects were observed with regards to insulin resistance. The unexposed Pxr−/− mice (vs WT) had decreased insulin resistance and improved insulin sensitivity as measured by fasting insulin (Figure 5B), HOMA-IR (Figure 5C), and QUICKI (Figure 5D). However, these favorable metabolic changes did not result in improved glucose tolerance. There was a trend towards increased QUICKI and improved insulin sensitivity in unexposed Car−/− versus WT (P = .054).

FIG. 5.

Effects of Aroclor 1260, Car and Pxr in glucose metabolism and insulin resistance. A, Fasting blood glucose levels (mg/dl) were measured and GTT was performed. B, HOMA-IR was calculated. C, Serum insulin levels were measured using the Luminex IS 100 system. D, QUICKI and E, HOMA-β which are indices for insulin sensitivity were calculated. Hepatic (F) Pepck-1, (G) G6Pase, and (H) Glut-2 mRNA levels were quantified by RT-PCR. Values are mean ± SEM, P < .05, a- Δ due to Aroclor 1260 exposure within genotype, b, b*- Δ between WT and Car−/− without or with Aroclor 1260 exposure, c, c*- Δ between WT and Pxr−/− without or with Aroclor 1260 exposure, d, d*- Δ between Car and Pxr ablation without or with Aroclor 1260 exposure.

Serum leptin levels were unchanged with either genotype or Aroclor exposure (data not shown). Serum adiponectin levels were increased in the knockout mice, regardless of Aroclor 1260 exposure, leading to significantly decreased leptin/adiponectin ratios (Supplementary Figure S6) versus WT. The improved leptin:adiponectin ratios may partially explain the increased insulin sensitivity observed in Pxr−/− mice and the trend towards improved insulin sensitivity in Car−/− mice. However, these changes are paradoxical because Pxr−/− mice had increased % body fat while the % body fat did not decrease in Car−/− versus WT (Figure 1C).

In order to determine why glucose tolerance did not improve along with insulin sensitivity/resistance, pancreatic insulin secretion, hepatic gluconeogenesis, and hepatic glucose transporters were measured. Pancreatic insulin secretion was measured by HOMA-β. Insulin secretion was significantly reduced by Aroclor 1260 in WT mice with trends towards reductions in both knockout mice groups (P = .11–.19) (Figure 5E). The unexposed Car−/− and Pxr−/− mice tended to exhibit decreased insulin release versus WT, but these trends did not reach statistical significance (P = .10–.14). To assess gluconeogenesis, the hepatic expression of the Car/Pxr indirect targets, phosphoenol-pyruvate carboxykinase 1 (Pepck-1) and glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase) were measured. Both knockout groups displayed significantly higher Pepck-1 expression levels than WT mice (Figure 5F). Pxr−/− mice exposed to Aroclor 1260 had increased G6Pase expression (Figure 5G), with a trend towards increased Pepck-1 expression (P = .12). Hepatic expression of the glucose transporters Glut-2 (insulin independent, Figure 5H) and Glut-4 (Supplementary Figure S7) were increased in Car−/− mice, while only Glut-2 was increased in Pxr−/− mice. Glut-2 expression was increased by Aroclor 1260 in WT and Car−/− mice, but this induction by Aroclor 1260 was lost in the Pxr−/− group (Figure 5H). The worsened glucose tolerance observed in Aroclor-exposed, but insulin sensitive, Pxr−/− mice may be explained by inappropriately activated gluconeogenesis, the failure of induction of insulin-independent hepatic glucose transport, and the trend towards impaired pancreatic insulin secretion.

Hepatic Lipid Metabolism

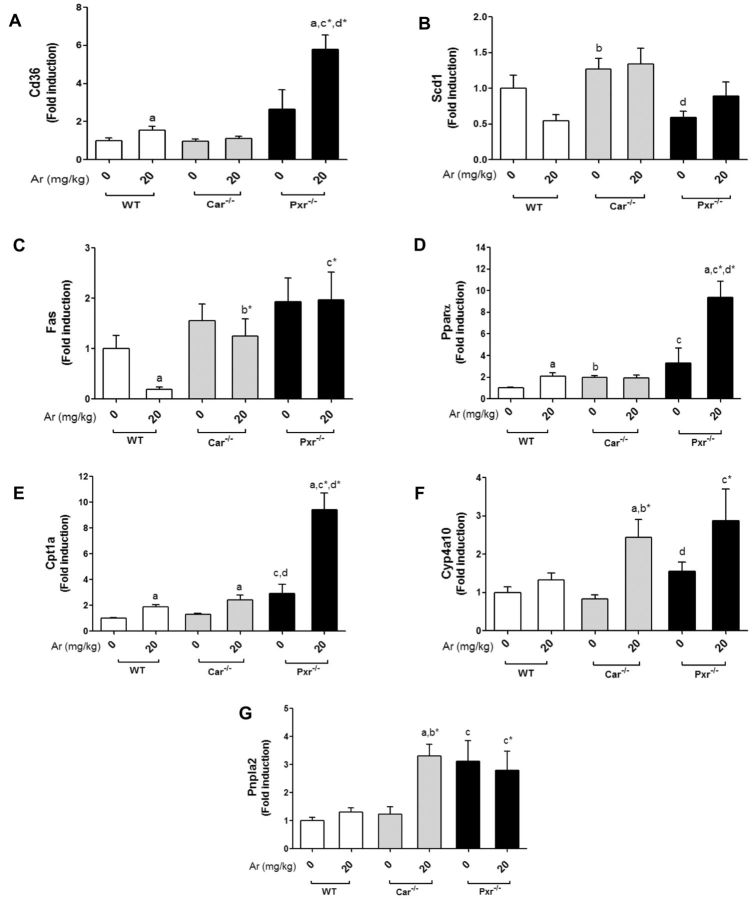

Previously, we demonstrated that Aroclor 1260 exposure modulated hepatic fat metabolism (Wahlang et al., 2014b). Hepatic lipid metabolism was assessed by measuring expression of genes related to lipid synthesis (Fas), uptake (Cd36 and Fabp1), oxidation (Pparα, Cpt1a, Cyp4a10), desaturation (Scd1), and lipolysis (Pnpla2). The hepatic expression of Cd36, a fatty acid-binding protein and a common target gene of Lxrα, Pxr, Ahr, and Pparγ, was assessed (Figure 6A). Interestingly, Aroclor 1260 exposure increased Cd36 expression in the WT and Pxr−/− groups. Car−/− mice had increased expression of Fabp1, another protein required for fatty acid uptake and transport across the cell membrane, and Aroclor exposure did not modify this genotype effect (Supplementary Figure S7). Basal expression of Scd1, another Lxrα target gene, was higher in Car−/− versus both WT and Pxr−/−, and this genotype effect was unchanged with exposure (Figure 6B). This result suggests that there could be differences in hepatic free fatty acids between genotypes. The hepatic expression of Fas, a classic Lxrα target gene, was decreased with Aroclor 1260 exposure in WT mice (Figure 6C), but this affect was lost in both knockout groups.

FIG. 6.

Effects of Aroclor 1260, Car and Pxr on hepatic expression of lipogenic and lipolytic genes. Hepatic mRNA expressions were measured for (A) Cd36, (B) Scd1, (C) Fas, (D) Pparα, (E) Cpt1a, (F) Cyp4a10, and (G) Pnpla2. Values are mean ± SEM, P < .05, a- Δ due to Aroclor 1260 exposure within genotype, b, b*- Δ between WT and Car−/− without or with Aroclor 1260 exposure, c, c*- Δ between WT and Pxr−/− without or with Aroclor 1260 exposure, d, d*- Δ between Car and Pxr ablation without or with Aroclor 1260 exposure.

Pparα drives the transcription of genes involved in fatty acid breakdown including Cpt1a and Cyp4a10. Hepatic expression of Pparα, Cpt1a, and Cyp4a10 were measured. Pparα mRNA levels were higher in the Aroclor 1260-exposed versus unexposed mice in the WT and Pxr−/− groups (Figure 6D). Pxr−/− mice had significantly higher basal Pparα expression than both WT and Car−/−. In contrast, Cpt1a was induced with Aroclor 1260 in all 3 groups irrespective of Car/Pxr ablation although the Pxr−/− knockout mice displayed higher basal Cpt1a expression levels than WT or Car−/− (Figure 6E). Aroclor 1260 induced Cyp4a10 only in Car−/− mice (Figure 6F), but there was a trend towards Cyp4a10 induction in Pxr−/− mice (P = .075). Lipases hydrolyze triglycerides prior to oxidation of free fatty acids. Hepatic expression of the lipolytic gene, Pnpla2, was measured. Aroclor 1260 exposure induced Pnpla2 in Car−/− mice only (Figure 6G). In Pxr−/− mice, the basal levels of Pnpla2 expression were elevated versus WT and Car−/− mice.

DISCUSSION

This study confirmed earlier findings demonstrating that Aroclor 1260 interacted with hepatic nuclear receptors and serves as a ‘second hit’ in the transition from diet-induced steatosis to steatohepatitis (Wahlang et al., 2014b). We hypothesized that Car ablation would worsen and Pxr ablation would protect against steatohepatitis in Aroclor 1260-exposed HFD mice. Although this did not prove to be the case, additional complexities were uncovered that could relate to ‘off-target’ PCB effects illustrating differences between PCBs and prototypical nuclear receptor ligands/activators; different HFD feeding protocols; and different genetic background of experimental mice as compared with other studies (Dong et al., 2009; Gao et al., 2009). Importantly, in this model, Pxr repressed basal Car expression and Aroclor-stimulated Car function, and this unexpected interaction likely modulated nuclear receptor cross-talk. To our knowledge, this study is the most extensive metabolic phenotype study performed to date on PCBs in metabolic syndrome. Careful phenotypic characterization was critical, because profound metabolic derangements could have been missed since Aroclor treatments did not impact the degree of obesity or hepatic steatosis.

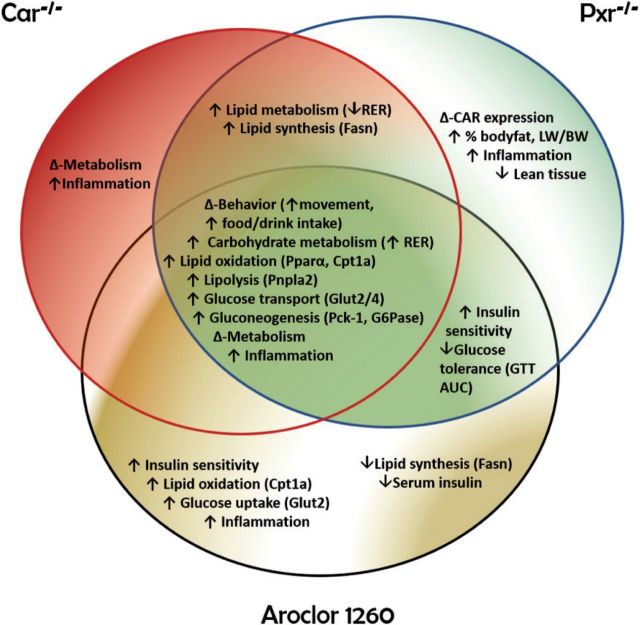

Key findings of this study include the impact of PCB-Pxr/Car interactions modulating endocrine disruption, energy metabolism, behavior, and inflammation to determine the response to diet-induced obesity in NAFLD. The function of the nuclear receptor subfamily 1 (Nr1) related receptors in lower organisms is to sense environmental conditions, such as food availability, and affect change in core life functions related to growth, development, and reproduction (Mooijaart et al., 2005). Due to their long half-life, PCBs may inappropriately activate these nuclear receptors, and the ensuing metabolic complexity appears to paradoxically dissociate foreign compound metabolism from components of the metabolic syndrome such as obesity, insulin resistance, and the pro-inflammatory state. Evidence supporting the concept that chronic NR1 receptor activation by xenobiotics leads to the dissociation of NAFLD from metabolic syndrome comes from the FLINT and PIVENS clinical trials. In the FLINT study, NASH patients were treated with obeticholic acid, a selective FXR agonist (Neuschwander-Tetri et al., 2015). Although obesity, steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis improved, HOMA-IR and hypercholesterolemia paradoxically worsened. In the PIVENS trial, NASH patients treated with the PPARγ agonist, pioglitazone, achieved improvements in hepatic lobular inflammation and HOMA-IR even though obesity paradoxically worsened (Sanyal et al., 2010). Thus, the major concepts illustrated by this study are that: (1) environmental pollution-nuclear receptor interactions may modify the response to diet-induced obesity in NAFLD, and (2) these interactions may lead to the paradoxical dissociation of NAFLD from other typically related components of metabolic syndrome. The specific results supporting the broad concepts in this study (Figure 7) are subsequently discussed.

FIG. 7.

A schematic diagram depicting potential PCB-receptor based mechanisms. The metabolic entities associated between Car−/−, Pxr−/−, and Aroclor 1260-exposed mice are shown at the center of the Venn Diagram.

Car and Pxr appeared to interact with one another as shown with increased basal Car in Pxr−/− mice, either implying that Pxr may repress Car expression in WT and Car−/− mice, or that Car−/− mice were merely compensating for the loss of Pxr by upregulating basal Car. Moreover, Car and Pxr appeared to be crucial in maintaining energy homeostasis because ablating either receptor decreased RER relative to WT mice, indicating a lipid-preferential metabolism (supported in part by increased basal expression of Pnpla2 and Pparα). RER estimates the respiratory quotient, which indicates whether the fuel source/EE originated from carbohydrate or lipid metabolism. An RER of 0.70 suggests that fat is the predominant fuel source, whereas an RER of 0.85 indicates a mix of fat and carbohydrate utilization. Aroclor 1260 exposure increased RER and carbohydrate utilization in the knockouts, despite upregulation of Pparα and lipid oxidative gene expression. However, Aroclor 1260 did not increase EE in any genotype, suggesting that Aroclor-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction may have occurred leading to impaired lipid metabolism, and the observed Pparα target gene expression may reflect attempted compensation.

Carbohydrate metabolism was altered at multiple levels including glucose tolerance, insulin resistance/sensitivity, adipokines, pancreatic insulin secretion, and hepatic gluconeogenesis/glucose transporters. In WT, Aroclor 1260 induced insulin sensitivity and insulin-independent hepatic glucose transporter expression. Unfortunately, glucose tolerance did not improve accordingly due to decreased glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and pancreatic dysfunction. Although the mechanism of PCB-mediated diabetes is debated in the literature (Perkins et al., 2015), a recent work demonstrated an inverse relation between PCB exposures and insulin levels (Jensen et al., 2014). Moreover, a recent chronic exposure study using Aroclor 1254 reported hyperinsulinemia in lean and diet-induced obese mice (Gray et al., 2013). However, the congener composition in Aroclor 1254 is strikingly different from that of Aroclor 1260 (Mayes et al., 1998), with the former containing higher amounts of dioxin-like PCBs. Importantly, the mechanisms underpinning Aroclor-mediated pancreatic dysfunction and insulin resistance are not entirely explained by PCB and Car/Pxr interactions, as similar trends occurred in HOMA-IR and HOMA-β regardless of genotype. Aroclor 1260-related reduction in pancreatic function appears to be an important novel determinant of hyperglycemia in diet-induced steatosis and these data demonstrate new modes of endocrine disruption by Aroclor 1260 in diabetes.

The positive fasting state conditions observed with PCB exposure were not reflected in the fed state with glucose challenge, as the GTT (AUC) worsened in Pxr−/− mice and failed to improve in other PCB-exposed groups. Furthermore, the PCB-exposed Pxr−/− mice showed a robust increase in hepatic gluconeogenic G6Pase expression, while both Pxr−/− and Car−/− mice showed increased basal Pepck-1 expression. These observations are consistent with previous studies demonstrating Car and Pxr to be repressors of hepatic gluconeogenic enzymes and Car/Pxr modulation of glucose metabolism via direct binding to the gluconeogenic transcription factor, Foxo1 (Dong et al., 2009; Kodama et al., 2004; Ma and Liu, 2012). The worsened glucose tolerance observed in Aroclor-exposed, insulin sensitive, Pxr−/− mice may be explained by elevated gluconeogenesis, failure of insulin-independent hepatic glucose transport, and a trend towards impaired pancreatic insulin secretion.

Although hepatic steatosis was unchanged, lipid metabolism was clearly regulated by PCB exposure and nuclear receptors. Aroclor 1260 decreased Fas expression in WT mice, indicating PCB suppression of hepatic lipogenesis and supporting studies documenting Car-mediated decreased hepatic expression of lipogenic genes (Dong et al., 2009; Gao et al., 2009) due to Car suppression of Lxrα transcriptional activity (Zhai et al., 2010). Notably, Aroclor 1260 induced Cpt1a (rate limiting enzyme of mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation), particularly in Pxr−/− mice. Studies have shown the repression of Cpt1a and other β-oxidation related genes with Pxr and Car activation and their enhanced expression in knockout models (Fernandez et al., 2013; Gao et al., 2009; Ueda et al., 2002). Cpt1a transcription is also mediated by the forkhead box protein A2 (FoxA2) and the hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha (Hnf4α) (Louet et al., 2002; Wolfrum et al., 2004). Pxr is a known inhibitor of Foxa2, hence its ablation increased Foxa2 basal expression and inducibility by Aroclor 1260 (Nakamura et al., 2007). Foxa2 activity is also positively regulated by low levels of insulin, which was displayed in Aroclor 1260-exposed groups (Wolfrum et al., 2003).

PCB-nuclear receptor interactions also modulated lifestyle behavior. Aroclor exposure induced a trend toward decreased bodyweight gain in Car−/− mice, which may be related to decreased food consumption and increased light phase movement. Aroclor 1260 also increased movement in the knockout groups during the light phase. Because laboratory mice are noc-turnal, both Pxr and Car are required to prevent PCB related sleep disturbances. Lifestyle changes including diet and exercise are the first line therapy for NASH patients; however, NASH was not improved in Aroclor-exposed Car−/− mice despite decreased food consumption and increased activity nor in Pxr−/− mice with increased activity, suggesting that PCB-nuclear receptor interactions may account for non-responsiveness to diet/exercise therapy in NASH.

With regard to inflammation, neither Car nor Pxr ablation improved steatohepatitis. Rather, Car−/− and Pxr−/− mice showed signs of hepatic inflammation with HFD feeding alone, as evident by both Tnfα and IL-6 basal expression levels. Suppression of the immune response by Pxr/Car in this animal model is not an entirely novel finding because previous studies have demonstrated that exposure to xenobiotic chemicals compromises immune function and that Pxr and nuclear factor kappa B mutually inhibit each other (Gerbal-Chaloin et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2006). Increased hepatic inflammation in NASH has been linked to insulin resistance, and insulin sensitizers have been proposed for the treatment of NASH (Sanyal et al., 2010). Paradoxically, PCBs worsened hepatic inflammation in WT mice even though insulin sensitivity was improved.

In summary, PCB exposures are a ‘second hit’ in the transition from diet-induced steatosis to steatohepatitis. PCB-Car/Pxr interactions modulate this transition, but are not completely responsible for it, as knocking out these receptors did not hinder this transition. Thus, the concept that Car is an anti-obesity receptor and Pxr is an obesity-promoting receptor may not reflect the full complexity of environmental contaminant-receptor interactions. Energy metabolism, behavior, and inflammation were regulated, in part, by PCB-nuclear receptor interactions. Furthermore, Pxr and Car paradoxically dissociated obesity, steatosis, insulin resistance, and inflammation in Aroclor-mediated NASH. Profound derangements in carbohydrate metabolism including changes in insulin sensitivity and pancreatic function were observed. The observed PCB-receptor interactions were only partially responsible for the observed phenotypic changes. Therefore, future directions include looking at other regulators of energy metabolism to explain some of the ‘off-target’ effects of PCB-induced endocrine disruption in NASH.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (1R01ES021375, 1R13ES024661, F30ES025099); the National Institute of Health (K23AA18399) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (200-2013-M-57311).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge (1) the University of Louisville Cancer Center biostatisticians, Dr Shesh Rai and Dr Jianmin Pan, for their assistance with the statistical analysis of the data; (2) the University of Louisville Alcohol Research Center; and the (3) Diabetes and Obesity Center for use of core resources. The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests relevant to this work.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at http://toxsci.oxfordjournals.org/.

REFERENCES

- Bligh E. G., Dyer W. J. (1959). A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37, 911–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cave M., Appana S., Patel M., Falkner K. C., McClain C. J., Brock G. (2010). Polychlorinated biphenyls, lead, and mercury are associated with liver disease in American adults: NHANES 2003–2004. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 1735–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmitrienko A., Molenberghs G., Chuang-Stein C., Offen W. (2005). Analysis of Clinical Trials Using SAS®: A practical Guide. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC. [Google Scholar]

- Dong B., Saha P. K., Huang W., Chen W., Abu-Elheiga L. A., Wakil S. J., Stevens R. D., Ilkayeva O., Newgard C. B., Chan L., et al. (2009). Activation of nuclear receptor CAR ameliorates diabetes and fatty liver disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 18831–18836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez A., Matias N., Fucho R., Ribas V., Von Montfort C., Nuno N., Baulies A., Martinez L., Tarrats N., Mari M., et al. (2013). ASMase is required for chronic alcohol induced hepatic endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial cholesterol loading. J. Hepatol. 59, 805–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., He J., Zhai Y., Wada T., Xie W. (2009). The constitutive androstane receptor is an anti-obesity nuclear receptor that improves insulin sensitivity. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 25984–25992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbal-Chaloin S., Iankova I., Maurel P., Daujat-Chavanieu M. (2013). Nuclear receptors in the cross-talk of drug metabolism and inflammation. Drug Metab. Rev. 45, 122–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray S. L., Shaw A. C., Gagne A. X., Chan H. M. (2013). Chronic exposure to PCBs (Aroclor 1254) exacerbates obesity-induced insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia in mice. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 76, 701–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handschin C., Meyer U. A. (2003). Induction of drug metabolism: The role of nuclear receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 55, 649–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez J. P., Mota L. C., Baldwin W. S. (2009). Activation of CAR and PXR by dietary, environmental and occupational chemicals alters drug metabolism, intermediary metabolism, and cell proliferation. Curr. Pharmacogenomics Person. Med. 7, 81–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G., Xu C., Staudinger J. L. (2010). Pregnane X receptor is SUMOylated to repress the inflammatory response. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 335, 342–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen T. K., Timmermann A. G., Rossing L. I., Ried-Larsen M., Grontved A., Andersen L. B., Dalgaard C., Hansen O. H., Scheike T., Nielsen F., et al. (2014). Polychlorinated biphenyl exposure and glucose metabolism in 9-year-old Danish children. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 99, E2643–E26451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer S. A., Goodwin B., Willson T. M. (2002). The nuclear pregnane X receptor: a key regulator of xenobiotic metabolism. Endocr. Rev. 23, 687–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama S., Koike C., Negishi M., Yamamoto Y. (2004). Nuclear receptors CAR and PXR cross talk with FOXO1 to regulate genes that encode drug-metabolizing and gluconeogenic enzymes. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 7931–7940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama S., Moore R., Yamamoto Y., Negishi M. (2007). Human nuclear pregnane X receptor cross-talk with CREB to repress cAMP activation of the glucose-6-phosphatase gene. Biochem. J. 407, 373–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno Y., Negishi M., Kodama S. (2008). The roles of nuclear receptors CAR and PXR in hepatic energy metabolism. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 23, 8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louet J. F., Hayhurst G., Gonzalez F. J., Girard J., Decaux J. F. (2002). The coactivator PGC-1 is involved in the regulation of the liver carnitine palmitoyltransferase I gene expression by cAMP in combination with HNF4 alpha and cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB). J. Biol. Chem. 277, 37991–8000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Liu D. (2012). Activation of pregnane X receptor by pregnenolone 16 alpha-carbonitrile prevents high-fat diet-induced obesity in AKR/J mice. PLoS One 7, e38734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf D. J., Thummel C., Beato M., Herrlich P., Schutz G., Umesono K., Blumberg B., Kastner P., Mark M., Chambon P., et al. (1995). The nuclear receptor superfamily: The second decade. Cell 83, 835–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes B. A., McConnell E. E., Neal B. H., Brunner M. J., Hamilton S. B., Sullivan T. M., Peters A. C., Ryan M. J., Toft J. D., Singer A. W., et al. (1998). Comparative carcinogenicity in Sprague-Dawley rats of the polychlorinated biphenyl mixtures Aroclors 1016, 1242, 1254, and 1260. Toxicol. Sci. 41, 62–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrell M. D., Cherrington N. J. (2011). Drug metabolism alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Drug Metab. Rev. 43, 317–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooijaart S. P., Brandt B. W., Baldal E. A., Pijpe J., Kuningas M., Beekman M., Zwaan B. J., Slagboom P. E., Westendorp R. G., van Heemst D. (2005). C. elegans DAF-12, Nuclear Hormone Receptors and human longevity and disease at old age. Ageing Res. Rev. 4, 351–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moya M., Gomez-Lechon M. J., Castell J. V., Jover R. (2010). Enhanced steatosis by nuclear receptor ligands: A study in cultured human hepatocytes and hepatoma cells with a characterized nuclear receptor expression profile. Chem. Biol. Interact. 184, 376–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K., Moore R., Negishi M., Sueyoshi T. (2007). Nuclear pregnane X receptor cross-talk with FoxA2 to mediate drug-induced regulation of lipid metabolism in fasting mouse liver. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 9768–9776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuschwander-Tetri B. A., Loomba R., Sanyal A. J., Lavine J. E., Van Natta M. L., Abdelmalek M. F., Chalasani N., Dasarathy S., Diehl A. M., Hameed B., et al. (2015). Farnesoid X nuclear receptor ligand obeticholic acid for non-cirrhotic, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (FLINT): A multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 385, 956–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novac N., Heinzel T. (2004). Nuclear receptors: Overview and classification. Curr. Drug Targets Inflamm. Allergy 3, 335–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins J. T., Petriello M. C., Newsome B. J., Hennig B. (2015). Polychlorinated biphenyls and links to cardiovascular disease. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 23, 2160–2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal A. J., Chalasani N., Kowdley K. V., McCullough A., Diehl A. M., Bass N. M., Neuschwander-Tetri B. A., Lavine J. E., Tonascia J., Unalp A., et al. (2010). Pioglitazone, vitamin E, or placebo for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 1675–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schecter A., Colacino J., Haffner D., Patel K., Opel M., Papke O., Birnbaum L. (2010). Perfluorinated compounds, polychlorinated biphenyls, and organochlorine pesticide contamination in composite food samples from Dallas, Texas, USA. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 796–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone A. E., Rosenbaum P. F., Weinstock R. S., Bartell S. M., Foushee H. R., Shelton C., Pavuk M. (2012). Polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) exposure and diabetes: Results from the Anniston Community Health Survey. Environ. Health Perspect. 120, 727–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruiell K., Richardson R. M., Cullen J. M., Awumey E. M., Gonzalez F. J., Gyamfi M. A. (2014). Role of pregnane X receptor in obesity and glucose homeostasis in male mice. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 3244–3261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda A., Hamadeh H. K., Webb H. K., Yamamoto Y., Sueyoshi T., Afshari C. A., Lehmann J. M., Negishi M. (2002). Diverse roles of the nuclear orphan receptor CAR in regulating hepatic genes in response to phenobarbital. Mol. Pharmacol. 61, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada T., Gao J., Xie W. (2009). PXR and CAR in energy metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 20, 273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlang B., Beier J. I., Clair H. B., Bellis-Jones H. J., Falkner K. C., McClain C. J., Cave M. C. (2013). Toxicant-associated steatohepatitis. Toxicol. Pathol. 41, 343–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlang B., Falkner K. C., Clair H. B., Al-Eryani L., Prough R. A., States J. C., Coslo D. M., Omiecinski C. J., Cave M. C. (2014a). Human receptor activation by aroclor 1260, a polychlorinated biphenyl mixture. Toxicol Sci. 140, 283–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlang B., Song M., Beier J. I., Cameron Falkner K., Al-Eryani L., Clair H. B., Prough R. A., Osborne T. S., Malarkey D. E., Christopher States J., et al. (2014b). Evaluation of Aroclor 1260 exposure in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 279, 380–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei P., Zhang J., Egan-Hafley M., Liang S., Moore D. D. (2000). The nuclear receptor CAR mediates specific xenobiotic induction of drug metabolism. Nature 407, 920–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir J. B. (1949). New methods for calculating metabolic rate with special reference to protein metabolism. J. Physiol. 109, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfrum C., Asilmaz E., Luca E., Friedman J. M., Stoffel M. (2004). Foxa2 regulates lipid metabolism and ketogenesis in the liver during fasting and in diabetes. Nature 432, 1027–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfrum C., Besser D., Luca E., Stoffel M. (2003). Insulin regulates the activity of forkhead transcription factor Hnf-3beta/Foxa-2 by Akt-mediated phosphorylation and nuclear/cytosolic localization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 11624–11629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Y., Wada T., Zhang B., Khadem S., Ren S., Kuruba R., Li S., Xie W. (2010). A functional cross-talk between liver X receptor-alpha and constitutive androstane receptor links lipogenesis and xenobiotic responses. Mol. Pharmacol. 78, 666–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C., Tabb M. M., Nelson E. L., Grun F., Verma S., Sadatrafiei A., Lin M., Mallick S., Forman B. M., Thummel K. E., et al. (2006). Mutual repression between steroid and xenobiotic receptor and NF-kappaB signaling pathways links xenobiotic metabolism and inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 2280–2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.