Abstract

Multiple imputation (MI) has been widely used for handling missing data in biomedical research. In the presence of high-dimensional data, regularized regression has been used as a natural strategy for building imputation models, but limited research has been conducted for handling general missing data patterns where multiple variables have missing values. Using the idea of multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE), we investigate two approaches of using regularized regression to impute missing values of high-dimensional data that can handle general missing data patterns. We compare our MICE methods with several existing imputation methods in simulation studies. Our simulation results demonstrate the superiority of the proposed MICE approach based on an indirect use of regularized regression in terms of bias. We further illustrate the proposed methods using two data examples.

Missing data are often encountered for various reasons in biomedical research and present challenges for data analysis. It is well known that inadequate handling of missing data may lead to biased estimation and inference. A number of statistical methods have been developed for handling missing data. Largely due to its ease of use, multiple imputation (MI)1,2 has been arguably the most popular method for handling missing data in practice. The basic idea underlying MI is to replace each missing data point with a set of values generated from its predictive distribution given observed data and to generate multiply imputed datasets to account for uncertainty of imputation. Each imputed data set is then analyzed separately using standard complete-data analysis methods and the results are combined across all imputed data sets using Rubin’s rule1,2. MI can be readily conducted using available software packages3,4,5 in a wide range of situations and has been investigated extensively in many settings6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Most of the existing MI methods rely on the assumption of missingness at random (MAR)2, i.e., missingness only depends on observed data; our current work also focuses on MAR. In recent years, the amount of data has increased considerably in many applications such as omic data and electronic health record data. In particular, the high dimensions in omic data may cause serious problems to MI in terms of applicability and accuracy. In what follows, we first describe some challenges of MI in the presence of high-dimensional data and explain why regularized regressions are suitable in this setting, and then review existing MI methods for general missing data patterns and propose their extensions for high-dimensional data.

Advances in technologies have led to collection of high-dimensional data such as omics data in many biomedical studies where the number of variables is very large and missing data are often present. Such high-dimensional data present unique challenges to MI. When conducting MI, Meng13 suggested imputation models be as general as data allow them to be, in order to accommodate a wide range of statistical analyses that may be conducted using multiply imputed data sets. However, in the presence of high-dimensional data, it is often infeasible to include all variables in an imputation model. As such, machine learning and model trimming techniques have been used in building imputation models in these settings. Stekhoven et al.14 proposed a random forest-based algorithm for missing data imputation called missForest. Random forest utilizes bootstrap aggregation of multiple regression trees to reduce the risk of overfitting, and combines the predictions from trees to improve accuracy of predictions15. Shah et al.16 suggested a variant of missForest and compared it to parametric imputation methods. They showed that their proposed random forest imputation method was more efficient and produced narrower confidence intervals than standard MI methods. Liao et al.17 developed four variations of K-nearest-neighbor (KNN) imputation methods. However, these methods are improper in the sense of Rubin (1987)1 since they do not adequately account for the uncertainty of estimating parameters in the imputation models. Improper imputation may lead to biased parameter estimates and inference in subsequent analyses. In addition, KNN methods are known to suffer from the curse of dimensionality18,19 and hence may not be suitable for high-dimensional data. Apart from random forest and KNN, regularized regression, which allows for simultaneous parameter estimation and variable selection, presents another option for building imputation models in the presence of high-dimensional data. The basic idea of regularized regression is to minimize the loss function of a regression, subject to some penalties. Different penalty specifications give rise to various regularized regression methods. Zhao and Long (2013)20 investigated the use of regularized regression for MI including lasso21, elastic net22 (EN), and adaptive lasso23 (Alasso). They also developed MI using a Bayesian lasso approach. However, they focused on the setting where only one variable has missing values. There has been limited work on MI methods for general missing data patterns where multiple variables have missing values in the presence of high-dimensional data.

To handle general missing data patterns, there are two MI approaches, one based on joint modeling (JM)24 and the other based on fully conditional specifications, the latter of which is also known as multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) and has been implemented independently by van Buuren et al. (2011)3 and Raghunathan et al. (1996)25. While JM has strong theoretical justifications and works reasonably well for low-dimensional data, its performance deteriorates as the data dimension increases26 and it is difficult to extend to high-dimensional data. MICE involves specifying a set of univariate imputation models. Since each imputation model is specified for one partially observed variable conditional on the other variables, it simplifies the modeling process. While MICE lacks theoretical justifications except for some special cases27,28, it has been shown to achieve satisfactory performance in extensive numerical studies and empirical examples. White et al. (2011)29 provides a nice review and guidance for MICE. It is worth mentioning that standard MICE methods cannot handle high-dimensional data. For example, the MICE algorithms proposed by van Buuren et al.3 and Su et al.5 cannot handle the prostate cancer data used in our data analysis and the high-dimensional data generated in our simulations. As such, we focus on extending MICE to high-dimensional data settings for handling general missing data patterns.

Methodology

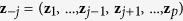

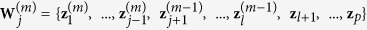

Suppose that our data set Z has p variables, z1, …, zp. Without loss of generality, we assume that the first l (l ≤ p) variables contain missing values. Suppose the data consist of n observations and we have rj observed values in variable zj. We denote the observed components and missing components for variable j by zj,obs and zj,mis. Let  be the collection of the p − 1 variables in Z except zj. Let z−j,obs and z−j,mis denote the two components of z−j corresponding to the complement data of zj,obs and zj,mis.

be the collection of the p − 1 variables in Z except zj. Let z−j,obs and z−j,mis denote the two components of z−j corresponding to the complement data of zj,obs and zj,mis.

Multiple imputation by chained equations

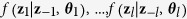

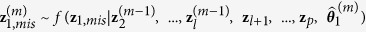

Let the hypothetically complete data Z be a partially observed random draw from a multivariate distribution  . We assume that the multivariate distribution of Z is completely specified by the unknown parameters θ. The standard MICE algorithm obtains a posterior distribution of θ by sampling iteratively from conditional distributions of the form

. We assume that the multivariate distribution of Z is completely specified by the unknown parameters θ. The standard MICE algorithm obtains a posterior distribution of θ by sampling iteratively from conditional distributions of the form  . Note that the parameters θ1, …, θl are specific to the conditional densities, which might not determine the unique ‘true’ joint distribution

. Note that the parameters θ1, …, θl are specific to the conditional densities, which might not determine the unique ‘true’ joint distribution  .

.

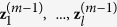

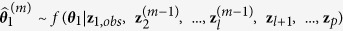

To be specific, MICE starts with a simple imputation, such as imputing the mean, for every missing value in the data set. Initial values are denoted by  . Then given values

. Then given values  at iteration

at iteration  , for variable

, for variable  , new parameter estimates

, new parameter estimates  of the next iteration are generated from

of the next iteration are generated from  through a regression model. Then the missing values

through a regression model. Then the missing values  for

for  are replaced with predicted values from the regression model with model parameter

are replaced with predicted values from the regression model with model parameter  . Note that when

. Note that when  is subsequently used as a predictor in the regression model for other variables that have missing values, both the observed and predicted values are used. These steps are repeated for each variable with missing values, that is, z1 to zl. Each iteration entails cycling through imputing z1 to zl. At the end of each iteration, all missing values are replaced by the predictions from regression models that expose the relationships observed in the data. We then repeat the procedures iteratively until convergence. The complete algorithm can be described as follows:

is subsequently used as a predictor in the regression model for other variables that have missing values, both the observed and predicted values are used. These steps are repeated for each variable with missing values, that is, z1 to zl. Each iteration entails cycling through imputing z1 to zl. At the end of each iteration, all missing values are replaced by the predictions from regression models that expose the relationships observed in the data. We then repeat the procedures iteratively until convergence. The complete algorithm can be described as follows:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note that while the observed data zobs do not change in the iterative updating procedure, the missing data zmis do change from one iteration to another. After convergence, the last  imputed data sets after appropriate thinning are chosen for subsequent standard complete-data analysis.

imputed data sets after appropriate thinning are chosen for subsequent standard complete-data analysis.

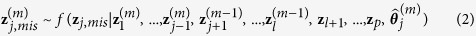

In the case of high-dimensional data, where p > rj or p ≈ rj, it is not feasible to fit the imputation model (1) using traditional regressions. In the following two subsections, we provide details of two approaches to apply regularized regression techniques in the presence of high-dimensional data for general missing data patterns.

Direct use of regularized regression for multiple imputation

For variable zj, our goal is to fit the imputation model (1) using rj cases with observed zj. Assuming that qj variables in z−j,obs are associated with zj,obs, we denote this set of  variables by

variables by  , which is also known as the true active set. We define the subset of predictors that are selected to impute

, which is also known as the true active set. We define the subset of predictors that are selected to impute  as the active set by

as the active set by  , and denote the corresponding design matrix as

, and denote the corresponding design matrix as  .We first consider an approach where a regularization method is used to conduct both model trimming and parameter estimation and a bootstrap step is incorporated to simulate random draws from

.We first consider an approach where a regularization method is used to conduct both model trimming and parameter estimation and a bootstrap step is incorporated to simulate random draws from  . This approach is referred to as MICE through the direct use of regularized regression (MICE-DURR). The purpose of the boostrap is to accommodate sampling variation in estimating population regression parameters, which is part of ensuring that imputations are proper16. In the

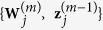

. This approach is referred to as MICE through the direct use of regularized regression (MICE-DURR). The purpose of the boostrap is to accommodate sampling variation in estimating population regression parameters, which is part of ensuring that imputations are proper16. In the  -th iteration and for variable

-th iteration and for variable  , (j = 1, …, l), define

, (j = 1, …, l), define  . Denote by

. Denote by  the component of

the component of  corresponding to

corresponding to  . The algorithm can be described as follows:

. The algorithm can be described as follows:

Generate a bootstrap data set

of size

of size  by randomly drawing

by randomly drawing  observations from

observations from  with replacement. Denote the observed values of

with replacement. Denote the observed values of  by

by  and the corresponding component of

and the corresponding component of  by

by  .

.Regarding

as the outcome and

as the outcome and  as predictors, use a regularized regression method to fit the model and obtain

as predictors, use a regularized regression method to fit the model and obtain  . Note that

. Note that  is considered a random draw from

is considered a random draw from  .

.Predict

with

with  by drawing randomly from the predictive distribution

by drawing randomly from the predictive distribution  , noting that imputation is conducted on the original data set

, noting that imputation is conducted on the original data set  , not the bootstrap data set

, not the bootstrap data set  .

.

We conduct the above procedure for  variables that have missing values in one iteration and repeat iteratively to obtain

variables that have missing values in one iteration and repeat iteratively to obtain  imputed data sets. Subsequently, standard complete-data analysis can be applied to each one of the

imputed data sets. Subsequently, standard complete-data analysis can be applied to each one of the  imputed data sets.

imputed data sets.

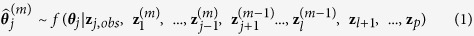

We make our approach clear by linking the above three steps to the MICE algorithm. In the first step, we bootstrap the data from the last iteration to ensure that the following imputations are proper. In the second step, we use regularized regressions to fit model (1) and obtain an estimate of θj. Then, we use this estimate to predict the missing values from the model (2). Details of MICE-DURR for three types of data can be found as Supplementary Method S1 online.

Indirect use of regularized regression for multiple imputation

MICE-DURR uses regularized regression for both model trimming and parameter estimation. An alternative approach to MICE-DURR is to use a regularization method for model trimming only and then followed by a standard multiple imputation procedure using the estimated active set ( ), say, through a maximum likelihood inference procedure. We refer to this approach as MICE through the indirect use of regularized regression (MICE-IURR). Suppose

), say, through a maximum likelihood inference procedure. We refer to this approach as MICE through the indirect use of regularized regression (MICE-IURR). Suppose  is defined as above. Denote by

is defined as above. Denote by  the component of

the component of  corresponding to

corresponding to  . At the

. At the  -th iteration and for variable

-th iteration and for variable  , the algorithm of the MICE-IURR approach is as follows:

, the algorithm of the MICE-IURR approach is as follows:

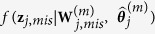

We use a regularized regression method to fit a multiple linear regression model regarding

as the outcome variable and

as the outcome variable and  as the predictor variable, and identify the active set,

as the predictor variable, and identify the active set,  . Let

. Let  denote the subset of

denote the subset of  that only contains the active set. Correspondingly, denote two components of

that only contains the active set. Correspondingly, denote two components of  by

by  and

and  .

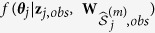

.Approximate the distribution of

by using a standard inference procedure such as maximum likelihood.

by using a standard inference procedure such as maximum likelihood.Predict

: randomly draw

: randomly draw  from

from  and subsequently predict

and subsequently predict  with

with  by drawing randomly from the predictive distribution

by drawing randomly from the predictive distribution  .

.

These three steps are conducted iteratively until convergence. We obtain the last  imputed data sets for the following analyses. In the third step, instead of fixing one

imputed data sets for the following analyses. In the third step, instead of fixing one  for all iterations, we randomly draw

for all iterations, we randomly draw  from the distribution and use it to predict

from the distribution and use it to predict  at each iteration. This strategy can guarantee that our imputations are proper30. Details of MICE-IURR for three types of data can be found as Supplementary Method S2 online.

at each iteration. This strategy can guarantee that our imputations are proper30. Details of MICE-IURR for three types of data can be found as Supplementary Method S2 online.

Simulation Studies

Extensive simulations are conducted to evaluate the performance of the two proposed methods MICE-DURR and MICE-IURR in comparison with the standard MICE and several other existing methods under general missing data patterns. For MICE-DURR and MICE-IURR, we consider three regularization methods, namely, lasso, EN and Alasso. We summarize the simulation results over 200 Monte Carlo (MC) data sets.

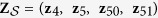

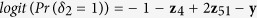

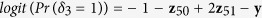

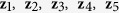

The setup of the simulations is similar to what was used in Zhao and Long (2013). Specifically, each MC data set has a sample size of  and includes

and includes  , the fully observed outcome variable, and

, the fully observed outcome variable, and  , the set of predictors and auxiliary variables. We consider settings with

, the set of predictors and auxiliary variables. We consider settings with  and

and  . We consider

. We consider  ,

,  , and

, and  having missing values, which follow a general missing data pattern. We first generate

having missing values, which follow a general missing data pattern. We first generate  from a multivariate normal distribution with mean

from a multivariate normal distribution with mean  and a first order autoregressive covariance matrix with autocorrelation

and a first order autoregressive covariance matrix with autocorrelation  varying as 0, 0.1, 0.5, and 0.9. Given

varying as 0, 0.1, 0.5, and 0.9. Given  , variables

, variables  ,

,  , and

, and  are generated independently from a normal distribution

are generated independently from a normal distribution  , where

, where  represents the common true active set with a cardinality of

represents the common true active set with a cardinality of  for all variables with missing values. We further consider settings where

for all variables with missing values. We further consider settings where  and 20, and

and 20, and  for

for  ;

;  for

for  . For

. For  and 20, the corresponding true active set

and 20, the corresponding true active set  and

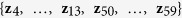

and  . Given Z, the outcome variable y is generated from

. Given Z, the outcome variable y is generated from  , where

, where  , and

, and  is random noise and independent of

is random noise and independent of  . Missing values are created in

. Missing values are created in  ,

,  , and

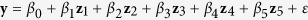

, and  using the following logit models for the corresponding missing indicators,

using the following logit models for the corresponding missing indicators,  ,

,  , and

, and  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  , resulting in approximately 40% of observations having missing values.

, resulting in approximately 40% of observations having missing values.

We compare our proposed MICE-DURR and MICE-IURR with the random forest imputation method (MICE-RF)16 and two KNN imputation methods17, one by the nearest variables (KNN-V) and the other by the nearest subjects (KNN-S). When applying MICE-RF, KNN-V, and KNN-S, the corresponding R packages returned errors when the incomplete dataset contains large number of variables (i.e.  ). As a result, these three methods are only applied to the setting of

). As a result, these three methods are only applied to the setting of  . Since the standard MI method as implemented in the R package mice is not directly applicable to the setting of

. Since the standard MI method as implemented in the R package mice is not directly applicable to the setting of  , we consider a standard MI approach that uses the true active set

, we consider a standard MI approach that uses the true active set  plus y to impute

plus y to impute  and

and  , denoted by MI-true. Of note, MI-true is not applicable in practice since the true active set is in general unknown.

, denoted by MI-true. Of note, MI-true is not applicable in practice since the true active set is in general unknown.

Following Shah et al.16, 10 imputed datasets are generated using each MI method; then a linear regression model is fitted to regress y on ( ) in each imputed data set and Rubin’s rule is applied to obtain

) in each imputed data set and Rubin’s rule is applied to obtain  and their SEs. Consistent with the recommendations in the literature3,29, we find in our numerical studies that imputed values using all the MI methods are fairly stable after 10 iterations and hence fix the number of iterations to 20. To benchmark bias and loss of efficiency in parameter estimation, two additional approaches that do not involve imputations are also included: a gold standard (GS) method that uses the underlying complete data before missing data are generated, and a complete-case analysis (CC) method that uses only complete-cases for which all the variables are observed2. We calculate the following measures to summarize the simulation results for

and their SEs. Consistent with the recommendations in the literature3,29, we find in our numerical studies that imputed values using all the MI methods are fairly stable after 10 iterations and hence fix the number of iterations to 20. To benchmark bias and loss of efficiency in parameter estimation, two additional approaches that do not involve imputations are also included: a gold standard (GS) method that uses the underlying complete data before missing data are generated, and a complete-case analysis (CC) method that uses only complete-cases for which all the variables are observed2. We calculate the following measures to summarize the simulation results for  ,

,  , and

, and  : mean bias, mean standard error (SE), Monte Carlo standard deviation (SD), mean square error (MSE) and coverage rate of the 95% confidence interval (CR).

: mean bias, mean standard error (SE), Monte Carlo standard deviation (SD), mean square error (MSE) and coverage rate of the 95% confidence interval (CR).

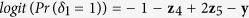

Tables 1, 2, 3 summarize the results for  ,

,  and

and  , respectively. Within each table different methods are compared and the effects of the cardinality of the true active set

, respectively. Within each table different methods are compared and the effects of the cardinality of the true active set  and dimension

and dimension  are evaluated with the correlation

are evaluated with the correlation  fixed. In all scenarios, GS and MI-true, neither of which is applicable in real data, lead to negligible bias and their CRs are close to the nominal level, whereas the complete-case analysis and the existing MI methods including MICE-RF, KNN-V and KNN-S lead to substantial bias. In particular, MICE-RF, with a large bias, tends to obtain a large coverage rate close to 1. KNN-V and KNN-S, on the other hand, impute the missing values only once and exhibit under-coverage of 95% CI, likely a result of improper imputation. MICE-DURR performs poorly with substantial bias in our settings with general missing data patterns. Of note, MICE-DURR was shown in Zhao and Long (2013)20 to improve the accuracy of the estimate in the simulation settings where only one variable has missing values. In comparison, the MICE-IURR approach achieves better performance–in terms of bias–than the other imputation methods except for MI-true. In all settings, the MICE-IURR method using lasso or EN exhibits small to negligible bias, similar to MI-true. When

fixed. In all scenarios, GS and MI-true, neither of which is applicable in real data, lead to negligible bias and their CRs are close to the nominal level, whereas the complete-case analysis and the existing MI methods including MICE-RF, KNN-V and KNN-S lead to substantial bias. In particular, MICE-RF, with a large bias, tends to obtain a large coverage rate close to 1. KNN-V and KNN-S, on the other hand, impute the missing values only once and exhibit under-coverage of 95% CI, likely a result of improper imputation. MICE-DURR performs poorly with substantial bias in our settings with general missing data patterns. Of note, MICE-DURR was shown in Zhao and Long (2013)20 to improve the accuracy of the estimate in the simulation settings where only one variable has missing values. In comparison, the MICE-IURR approach achieves better performance–in terms of bias–than the other imputation methods except for MI-true. In all settings, the MICE-IURR method using lasso or EN exhibits small to negligible bias, similar to MI-true. When  , the biases and MSEs for MICE-RF, KNN-V, and MICE-DURR decrease as

, the biases and MSEs for MICE-RF, KNN-V, and MICE-DURR decrease as  increases, whereas the performance of KNN-S deteriorates. The MICE-IURR methods tend to give fairly stable results as

increases, whereas the performance of KNN-S deteriorates. The MICE-IURR methods tend to give fairly stable results as  changes. When

changes. When  and

and  are fixed, the results of MICE-DURR and MICE-IURR with

are fixed, the results of MICE-DURR and MICE-IURR with  are very similar compared with the results with

are very similar compared with the results with  .

.

Table 1. Simulation results for estimating β 1 = β 2 = β 3 = 1 in the presence of missing data based on 200 monte carlo data sets, where n = 100 and ρ = 0.1.

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias | SE | SD | MSE | CR | Bias | SE | SD | MSE | CR | Bias | SE | SD | MSE | CR | ||

| q = 4 | GS | 0.010 | 0.519 | 0.484 | 0.233 | 0.960 | −0.004 | 0.518 | 0.514 | 0.263 | 0.930 | −0.003 | 0.522 | 0.507 | 0.255 | 0.960 |

| CC | −0.273 | 0.560 | 0.570 | 0.398 | 0.910 | −0.277 | 0.561 | 0.556 | 0.385 | 0.915 | −0.350 | 0.566 | 0.570 | 0.446 | 0.865 | |

| MI-true | 0.023 | 0.718 | 0.676 | 0.455 | 0.940 | −0.013 | 0.719 | 0.721 | 0.517 | 0.920 | −0.109 | 0.728 | 0.692 | 0.489 | 0.950 | |

| p = 200 | ||||||||||||||||

| MICE-RF | −0.618 | 0.697 | 0.364 | 0.514 | 0.970 | −0.469 | 0.699 | 0.331 | 0.329 | 1.000 | −0.615 | 0.701 | 0.341 | 0.494 | 0.940 | |

| KNN-V | −0.800 | 0.696 | 0.584 | 0.979 | 0.845 | −0.369 | 0.700 | 0.552 | 0.440 | 0.975 | −0.696 | 0.712 | 0.547 | 0.782 | 0.900 | |

| KNN-S | −0.273 | 0.560 | 0.570 | 0.398 | 0.910 | −0.277 | 0.561 | 0.556 | 0.385 | 0.915 | −0.350 | 0.566 | 0.570 | 0.446 | 0.865 | |

| MICE-DURR(Lasso) | −0.781 | 0.572 | 0.404 | 0.773 | 0.775 | −0.543 | 0.567 | 0.431 | 0.479 | 0.895 | −0.759 | 0.583 | 0.431 | 0.760 | 0.775 | |

| MICE-DURR(EN) | −0.784 | 0.575 | 0.407 | 0.779 | 0.790 | −0.534 | 0.568 | 0.428 | 0.467 | 0.895 | −0.759 | 0.585 | 0.432 | 0.761 | 0.755 | |

| MICE-DURR(Alasso) | −0.774 | 0.589 | 0.374 | 0.739 | 0.800 | −0.557 | 0.581 | 0.384 | 0.458 | 0.925 | −0.768 | 0.600 | 0.392 | 0.742 | 0.820 | |

| MICE-IURR(Lasso) | −0.031 | 0.684 | 0.711 | 0.503 | 0.935 | −0.017 | 0.681 | 0.697 | 0.484 | 0.920 | −0.173 | 0.692 | 0.676 | 0.485 | 0.930 | |

| MICE-IURR(EN) | −0.047 | 0.673 | 0.731 | 0.534 | 0.920 | −0.009 | 0.670 | 0.703 | 0.491 | 0.910 | −0.144 | 0.676 | 0.703 | 0.513 | 0.900 | |

| MICE-IURR(Alasso) | −0.105 | 0.759 | 0.813 | 0.668 | 0.905 | −0.181 | 0.751 | 0.794 | 0.660 | 0.910 | −0.283 | 0.759 | 0.751 | 0.641 | 0.925 | |

| p = 1000 | ||||||||||||||||

| MICE-DURR(Lasso) | −0.769 | 0.579 | 0.412 | 0.761 | 0.810 | −0.568 | 0.576 | 0.474 | 0.547 | 0.885 | −0.720 | 0.580 | 0.405 | 0.682 | 0.855 | |

| MICE-DURR(EN) | −0.766 | 0.578 | 0.414 | 0.758 | 0.835 | −0.558 | 0.581 | 0.465 | 0.526 | 0.900 | −0.719 | 0.584 | 0.413 | 0.687 | 0.840 | |

| MICE-DURR(Alasso) | −0.748 | 0.582 | 0.364 | 0.691 | 0.855 | −0.576 | 0.583 | 0.441 | 0.525 | 0.905 | −0.751 | 0.588 | 0.396 | 0.720 | 0.815 | |

| MICE-IURR(Lasso) | 0.021 | 0.683 | 0.780 | 0.605 | 0.885 | −0.037 | 0.677 | 0.778 | 0.603 | 0.910 | −0.168 | 0.689 | 0.714 | 0.536 | 0.910 | |

| MICE-IURR(EN) | 0.050 | 0.671 | 0.776 | 0.601 | 0.890 | −0.049 | 0.671 | 0.779 | 0.606 | 0.900 | −0.158 | 0.680 | 0.724 | 0.546 | 0.915 | |

| MICE-IURR(Alasso) | −0.159 | 0.791 | 0.901 | 0.834 | 0.905 | −0.245 | 0.777 | 0.849 | 0.777 | 0.905 | −0.366 | 0.786 | 0.767 | 0.720 | 0.925 | |

| q = 20 | GS | 0.012 | 0.540 | 0.492 | 0.241 | 0.975 | 0.010 | 0.535 | 0.548 | 0.299 | 0.930 | −0.008 | 0.542 | 0.508 | 0.256 | 0.965 |

| CC | −0.366 | 0.529 | 0.554 | 0.439 | 0.865 | −0.359 | 0.526 | 0.517 | 0.395 | 0.905 | −0.443 | 0.535 | 0.495 | 0.440 | 0.865 | |

| MI-true | −0.097 | 0.715 | 0.627 | 0.400 | 0.950 | −0.089 | 0.713 | 0.660 | 0.441 | 0.930 | −0.133 | 0.728 | 0.683 | 0.482 | 0.950 | |

| p = 200 | ||||||||||||||||

| MICE-RF | −0.468 | 0.730 | 0.429 | 0.402 | 0.975 | −0.384 | 0.710 | 0.416 | 0.320 | 0.980 | −0.447 | 0.725 | 0.412 | 0.369 | 0.980 | |

| KNN-V | −0.412 | 0.684 | 0.527 | 0.446 | 0.945 | −0.266 | 0.678 | 0.531 | 0.351 | 0.960 | −0.389 | 0.691 | 0.544 | 0.445 | 0.945 | |

| KNN-S | −0.366 | 0.529 | 0.554 | 0.439 | 0.865 | −0.359 | 0.526 | 0.517 | 0.395 | 0.905 | −0.443 | 0.535 | 0.495 | 0.440 | 0.865 | |

| MICE-DURR(Lasso) | −0.494 | 0.675 | 0.464 | 0.458 | 0.960 | −0.374 | 0.666 | 0.442 | 0.334 | 0.970 | −0.443 | 0.678 | 0.442 | 0.390 | 0.970 | |

| MICE-DURR(EN) | −0.499 | 0.677 | 0.480 | 0.478 | 0.965 | −0.379 | 0.660 | 0.430 | 0.328 | 0.965 | −0.435 | 0.679 | 0.448 | 0.389 | 0.975 | |

| MICE-DURR(Alasso) | −0.488 | 0.685 | 0.475 | 0.462 | 0.945 | −0.378 | 0.675 | 0.412 | 0.312 | 0.980 | −0.457 | 0.693 | 0.423 | 0.387 | 0.985 | |

| MICE-IURR(Lasso) | −0.058 | 0.695 | 0.714 | 0.510 | 0.915 | 0.058 | 0.671 | 0.732 | 0.536 | 0.875 | −0.048 | 0.698 | 0.756 | 0.570 | 0.905 | |

| MICE-IURR(EN) | −0.049 | 0.691 | 0.705 | 0.496 | 0.930 | 0.023 | 0.679 | 0.715 | 0.509 | 0.880 | −0.041 | 0.697 | 0.743 | 0.551 | 0.910 | |

| MICE-IURR(Alasso) | −0.214 | 0.714 | 0.735 | 0.583 | 0.905 | −0.197 | 0.700 | 0.774 | 0.635 | 0.890 | −0.309 | 0.719 | 0.760 | 0.671 | 0.880 | |

| p = 1000 | ||||||||||||||||

| MICE-DURR(Lasso) | −0.435 | 0.677 | 0.470 | 0.409 | 0.970 | −0.401 | 0.673 | 0.461 | 0.372 | 0.964 | −0.471 | 0.679 | 0.437 | 0.412 | 0.976 | |

| MICE-DURR(EN) | −0.443 | 0.673 | 0.476 | 0.422 | 0.964 | −0.403 | 0.669 | 0.476 | 0.387 | 0.952 | −0.451 | 0.678 | 0.463 | 0.416 | 0.982 | |

| MICE-DURR(Alasso) | −0.434 | 0.678 | 0.475 | 0.412 | 0.976 | −0.401 | 0.681 | 0.451 | 0.363 | 0.982 | −0.474 | 0.683 | 0.433 | 0.411 | 0.970 | |

| MICE-IURR(Lasso) | 0.095 | 0.686 | 0.781 | 0.616 | 0.909 | −0.019 | 0.687 | 0.858 | 0.732 | 0.885 | −0.073 | 0.711 | 0.737 | 0.545 | 0.933 | |

| MICE-IURR(EN) | 0.082 | 0.689 | 0.776 | 0.606 | 0.897 | −0.009 | 0.687 | 0.870 | 0.752 | 0.867 | −0.069 | 0.705 | 0.749 | 0.562 | 0.915 | |

| MICE-IURR(Alasso) | −0.212 | 0.739 | 0.758 | 0.615 | 0.927 | −0.352 | 0.721 | 0.767 | 0.708 | 0.897 | −0.394 | 0.732 | 0.745 | 0.707 | 0.885 | |

Bias, mean bias; SE, mean standard error; SD, Monte Carlo standard deviation; MSE, mean square error; CR, coverage rate of 95% confidence interval; GS, gold standard; CC, complete-case; KNN-V, KNN by nearest variables; KNN-S, KNN by nearest subjects; MICE-DURR, MICE through direct use of regularized regressions; MICE-IURR, MICE through indirect use of regularized regressions; EN, elastic net; Alasso, adaptive lasso.

Table 2. Simulation results for estimating β 1 = β 2 = β 3 = 1 in the presence of missing data based on 200 monte carlo data sets, where n = 100 and ρ = 0.5.

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias | SE | SD | MSE | CR | Bias | SE | SD | MSE | CR | Bias | SE | SD | MSE | CR | ||

| q = 4 | GS | 0.007 | 0.515 | 0.478 | 0.228 | 0.970 | −0.014 | 0.515 | 0.533 | 0.283 | 0.940 | −0.037 | 0.519 | 0.496 | 0.246 | 0.970 |

| CC | −0.274 | 0.569 | 0.560 | 0.387 | 0.890 | −0.272 | 0.570 | 0.588 | 0.418 | 0.910 | −0.265 | 0.573 | 0.529 | 0.349 | 0.935 | |

| MI-true | −0.068 | 0.687 | 0.687 | 0.474 | 0.925 | 0.010 | 0.698 | 0.717 | 0.512 | 0.915 | −0.062 | 0.693 | 0.685 | 0.470 | 0.925 | |

| p = 200 | ||||||||||||||||

| MICE-RF | −0.628 | 0.747 | 0.352 | 0.518 | 0.960 | −0.355 | 0.711 | 0.371 | 0.263 | 0.980 | −0.510 | 0.725 | 0.349 | 0.382 | 0.975 | |

| KNN-V | −0.930 | 0.708 | 0.545 | 1.160 | 0.800 | −0.242 | 0.711 | 0.535 | 0.343 | 0.980 | −0.655 | 0.720 | 0.557 | 0.738 | 0.925 | |

| KNN-S | −0.274 | 0.569 | 0.560 | 0.387 | 0.890 | −0.272 | 0.570 | 0.588 | 0.418 | 0.910 | −0.265 | 0.573 | 0.529 | 0.349 | 0.935 | |

| MICE-DURR(Lasso) | −0.853 | 0.548 | 0.407 | 0.892 | 0.720 | −0.475 | 0.544 | 0.384 | 0.373 | 0.925 | −0.688 | 0.546 | 0.418 | 0.647 | 0.860 | |

| MICE-DURR(EN) | −0.852 | 0.548 | 0.412 | 0.894 | 0.695 | −0.474 | 0.541 | 0.386 | 0.372 | 0.935 | −0.688 | 0.550 | 0.411 | 0.641 | 0.845 | |

| MICE-DURR(Alasso) | −0.844 | 0.566 | 0.349 | 0.834 | 0.785 | −0.486 | 0.563 | 0.351 | 0.359 | 0.945 | −0.701 | 0.570 | 0.374 | 0.631 | 0.870 | |

| MICE-IURR(Lasso) | −0.094 | 0.668 | 0.690 | 0.483 | 0.930 | −0.080 | 0.669 | 0.729 | 0.536 | 0.885 | −0.068 | 0.661 | 0.703 | 0.496 | 0.925 | |

| MICE-IURR(EN) | −0.092 | 0.653 | 0.701 | 0.498 | 0.935 | −0.074 | 0.667 | 0.724 | 0.527 | 0.910 | −0.069 | 0.647 | 0.705 | 0.499 | 0.915 | |

| MICE-IURR(Alasso) | −0.091 | 0.720 | 0.744 | 0.559 | 0.940 | −0.076 | 0.710 | 0.790 | 0.626 | 0.880 | −0.123 | 0.719 | 0.761 | 0.592 | 0.920 | |

| p = 1000 | ||||||||||||||||

| MICE-DURR(Lasso) | −0.809 | 0.560 | 0.392 | 0.807 | 0.715 | −0.534 | 0.558 | 0.445 | 0.482 | 0.905 | −0.713 | 0.568 | 0.437 | 0.698 | 0.825 | |

| MICE-DURR(EN) | −0.806 | 0.560 | 0.398 | 0.808 | 0.710 | −0.530 | 0.560 | 0.458 | 0.490 | 0.920 | −0.711 | 0.568 | 0.433 | 0.693 | 0.815 | |

| MICE-DURR(Alasso) | −0.803 | 0.567 | 0.354 | 0.770 | 0.755 | −0.544 | 0.565 | 0.409 | 0.463 | 0.905 | −0.730 | 0.577 | 0.379 | 0.676 | 0.840 | |

| MICE-IURR(Lasso) | 0.058 | 0.677 | 0.836 | 0.698 | 0.860 | −0.040 | 0.676 | 0.811 | 0.656 | 0.890 | −0.197 | 0.677 | 0.752 | 0.601 | 0.905 | |

| MICE-IURR(EN) | 0.073 | 0.664 | 0.808 | 0.655 | 0.850 | −0.041 | 0.667 | 0.800 | 0.638 | 0.890 | −0.192 | 0.670 | 0.739 | 0.581 | 0.885 | |

| MICE-IURR(Alasso) | −0.036 | 0.793 | 0.912 | 0.829 | 0.865 | −0.209 | 0.783 | 0.852 | 0.765 | 0.885 | −0.335 | 0.779 | 0.792 | 0.737 | 0.910 | |

| q = 20 | GS | 0.014 | 0.521 | 0.500 | 0.249 | 0.950 | −0.008 | 0.523 | 0.550 | 0.301 | 0.920 | −0.023 | 0.527 | 0.506 | 0.255 | 0.970 |

| CC | −0.352 | 0.525 | 0.536 | 0.410 | 0.855 | −0.357 | 0.529 | 0.541 | 0.418 | 0.875 | −0.387 | 0.533 | 0.520 | 0.419 | 0.890 | |

| MI-true | −0.077 | 0.689 | 0.593 | 0.356 | 0.965 | −0.047 | 0.688 | 0.675 | 0.456 | 0.920 | −0.092 | 0.692 | 0.628 | 0.401 | 0.965 | |

| p = 200 | ||||||||||||||||

| MICE-RF | −0.390 | 0.717 | 0.427 | 0.333 | 0.990 | −0.286 | 0.708 | 0.466 | 0.298 | 0.985 | −0.412 | 0.721 | 0.382 | 0.315 | 0.995 | |

| KNN-V | −0.450 | 0.685 | 0.530 | 0.482 | 0.950 | −0.214 | 0.697 | 0.561 | 0.359 | 0.970 | −0.441 | 0.703 | 0.469 | 0.413 | 0.980 | |

| KNN-S | −0.352 | 0.525 | 0.536 | 0.410 | 0.855 | −0.357 | 0.529 | 0.541 | 0.418 | 0.875 | −0.387 | 0.533 | 0.520 | 0.419 | 0.890 | |

| MICE-DURR(Lasso) | −0.491 | 0.631 | 0.451 | 0.444 | 0.955 | −0.329 | 0.633 | 0.486 | 0.343 | 0.970 | −0.532 | 0.644 | 0.421 | 0.459 | 0.975 | |

| MICE-DURR(EN) | −0.489 | 0.631 | 0.455 | 0.445 | 0.920 | −0.340 | 0.627 | 0.486 | 0.351 | 0.970 | −0.518 | 0.641 | 0.401 | 0.428 | 0.970 | |

| MICE-DURR(Alasso) | −0.481 | 0.655 | 0.425 | 0.412 | 0.940 | −0.348 | 0.653 | 0.452 | 0.325 | 0.975 | −0.529 | 0.668 | 0.377 | 0.422 | 0.960 | |

| MICE-IURR(Lasso) | −0.022 | 0.678 | 0.729 | 0.530 | 0.905 | −0.024 | 0.684 | 0.752 | 0.563 | 0.870 | −0.057 | 0.683 | 0.689 | 0.475 | 0.905 | |

| MICE-IURR(EN) | −0.023 | 0.666 | 0.695 | 0.481 | 0.920 | −0.022 | 0.670 | 0.730 | 0.531 | 0.855 | −0.036 | 0.675 | 0.674 | 0.453 | 0.925 | |

| MICE-IURR(Alasso) | −0.144 | 0.731 | 0.721 | 0.539 | 0.910 | −0.103 | 0.719 | 0.764 | 0.591 | 0.895 | −0.181 | 0.720 | 0.718 | 0.546 | 0.955 | |

| p = 1000 | ||||||||||||||||

| MICE-DURR(Lasso) | −0.436 | 0.640 | 0.415 | 0.361 | 0.978 | −0.399 | 0.628 | 0.490 | 0.396 | 0.956 | −0.458 | 0.640 | 0.393 | 0.363 | 0.989 | |

| MICE-DURR(EN) | −0.459 | 0.631 | 0.437 | 0.399 | 0.978 | −0.375 | 0.626 | 0.492 | 0.380 | 0.967 | −0.460 | 0.636 | 0.407 | 0.375 | 1.000 | |

| MICE-DURR(Alasso) | −0.450 | 0.651 | 0.419 | 0.376 | 0.978 | −0.387 | 0.642 | 0.482 | 0.380 | 0.978 | −0.487 | 0.655 | 0.384 | 0.382 | 0.989 | |

| MICE-IURR(Lasso) | 0.012 | 0.682 | 0.750 | 0.556 | 0.900 | 0.004 | 0.660 | 0.712 | 0.502 | 0.956 | −0.079 | 0.687 | 0.630 | 0.398 | 0.933 | |

| MICE-IURR(EN) | 0.020 | 0.672 | 0.738 | 0.539 | 0.878 | 0.018 | 0.662 | 0.725 | 0.521 | 0.911 | −0.086 | 0.653 | 0.660 | 0.438 | 0.933 | |

| MICE-IURR(Alasso) | −0.204 | 0.766 | 0.767 | 0.624 | 0.878 | −0.135 | 0.745 | 0.778 | 0.617 | 0.889 | −0.318 | 0.737 | 0.666 | 0.540 | 0.911 | |

Bias, mean bias; SE, mean standard error; SD, Monte Carlo standard deviation; MSE, mean square error; CR, coverage rate of 95% confidence interval; GS, gold standard; CC, complete-case; KNN-V, KNN by nearest variables; KNN-S, KNN by nearest subjects; MICE-DURR, MICE through direct use of regularized regressions; MICE-IURR, MICE through indirect use of regularized regressions; EN, elastic net; Alasso, adaptive lasso.

Table 3. Simulation results for estimating β 1 = β 2 = β 3 = 1 in the presence of missing data based on 200 monte carlo data sets, where n = 100 and ρ = 0.9.

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias | SE | SD | MSE | CR | Bias | SE | SD | MSE | CR | Bias | SE | SD | MSE | CR | ||

| q = 4 | GS | 0.029 | 0.515 | 0.476 | 0.226 | 0.960 | 0.003 | 0.512 | 0.521 | 0.270 | 0.945 | 0.008 | 0.517 | 0.489 | 0.238 | 0.970 |

| CC | −0.219 | 0.583 | 0.609 | 0.417 | 0.905 | −0.245 | 0.585 | 0.560 | 0.371 | 0.925 | −0.242 | 0.582 | 0.582 | 0.395 | 0.945 | |

| MI-true | −0.012 | 0.711 | 0.699 | 0.487 | 0.935 | −0.027 | 0.710 | 0.715 | 0.509 | 0.915 | −0.007 | 0.701 | 0.685 | 0.467 | 0.940 | |

| p = 200 | ||||||||||||||||

| MICE-RF | −0.483 | 0.721 | 0.358 | 0.361 | 0.980 | −0.277 | 0.704 | 0.376 | 0.218 | 1.000 | −0.372 | 0.722 | 0.380 | 0.283 | 0.975 | |

| KNN-V | −1.034 | 0.747 | 0.584 | 1.408 | 0.765 | −0.113 | 0.741 | 0.596 | 0.366 | 0.990 | −0.676 | 0.758 | 0.630 | 0.852 | 0.895 | |

| KNN-S | −0.219 | 0.583 | 0.609 | 0.417 | 0.905 | −0.245 | 0.585 | 0.560 | 0.371 | 0.925 | −0.242 | 0.582 | 0.582 | 0.395 | 0.945 | |

| MICE-DURR(Lasso) | −0.857 | 0.547 | 0.435 | 0.922 | 0.670 | −0.549 | 0.532 | 0.417 | 0.475 | 0.905 | −0.643 | 0.545 | 0.441 | 0.606 | 0.835 | |

| MICE-DURR(EN) | −0.862 | 0.548 | 0.443 | 0.939 | 0.670 | −0.534 | 0.537 | 0.420 | 0.461 | 0.880 | −0.649 | 0.550 | 0.438 | 0.612 | 0.815 | |

| MICE-DURR(Alasso) | −0.841 | 0.571 | 0.409 | 0.874 | 0.745 | −0.525 | 0.564 | 0.377 | 0.417 | 0.935 | −0.677 | 0.576 | 0.396 | 0.615 | 0.855 | |

| MICE-IURR(Lasso) | −0.049 | 0.676 | 0.701 | 0.491 | 0.915 | −0.047 | 0.671 | 0.694 | 0.481 | 0.920 | −0.027 | 0.669 | 0.702 | 0.492 | 0.920 | |

| MICE-IURR(EN) | −0.028 | 0.671 | 0.716 | 0.511 | 0.915 | −0.059 | 0.676 | 0.707 | 0.501 | 0.910 | −0.052 | 0.677 | 0.706 | 0.498 | 0.935 | |

| MICE-IURR(Alasso) | −0.005 | 0.684 | 0.710 | 0.502 | 0.920 | −0.024 | 0.685 | 0.727 | 0.526 | 0.915 | −0.031 | 0.679 | 0.710 | 0.503 | 0.935 | |

| p = 1000 | ||||||||||||||||

| MICE-DURR(Lasso) | −0.787 | 0.556 | 0.399 | 0.778 | 0.740 | −0.494 | 0.538 | 0.405 | 0.408 | 0.920 | −0.688 | 0.559 | 0.375 | 0.613 | 0.845 | |

| MICE-DURR(EN) | −0.793 | 0.554 | 0.414 | 0.799 | 0.715 | −0.490 | 0.534 | 0.410 | 0.407 | 0.900 | −0.681 | 0.562 | 0.373 | 0.603 | 0.840 | |

| MICE-DURR(Alasso) | −0.801 | 0.572 | 0.363 | 0.772 | 0.775 | −0.496 | 0.557 | 0.369 | 0.382 | 0.930 | −0.705 | 0.577 | 0.339 | 0.611 | 0.880 | |

| MICE-IURR(Lasso) | −0.014 | 0.682 | 0.744 | 0.550 | 0.930 | −0.058 | 0.672 | 0.763 | 0.582 | 0.915 | −0.144 | 0.680 | 0.709 | 0.521 | 0.920 | |

| MICE-IURR(EN) | 0.009 | 0.679 | 0.729 | 0.529 | 0.935 | −0.062 | 0.667 | 0.744 | 0.555 | 0.915 | −0.155 | 0.672 | 0.702 | 0.515 | 0.930 | |

| MICE-IURR(Alasso) | −0.029 | 0.729 | 0.739 | 0.545 | 0.935 | −0.024 | 0.716 | 0.818 | 0.666 | 0.895 | −0.130 | 0.715 | 0.760 | 0.592 | 0.910 | |

| q = 20 | GS | 0.018 | 0.514 | 0.478 | 0.228 | 0.945 | −0.010 | 0.512 | 0.519 | 0.268 | 0.945 | −0.003 | 0.515 | 0.488 | 0.237 | 0.975 |

| CC | −0.260 | 0.570 | 0.562 | 0.382 | 0.930 | −0.295 | 0.566 | 0.533 | 0.370 | 0.930 | −0.304 | 0.568 | 0.537 | 0.379 | 0.925 | |

| MI-true | −0.056 | 0.681 | 0.561 | 0.316 | 0.975 | −0.075 | 0.671 | 0.590 | 0.352 | 0.980 | −0.009 | 0.667 | 0.566 | 0.319 | 0.960 | |

| p = 200 | ||||||||||||||||

| MICE-RF | −0.334 | 0.747 | 0.361 | 0.241 | 0.995 | −0.153 | 0.707 | 0.362 | 0.154 | 1.000 | −0.269 | 0.756 | 0.398 | 0.230 | 1.000 | |

| KNN-V | −0.798 | 0.749 | 0.555 | 0.943 | 0.895 | −0.108 | 0.739 | 0.555 | 0.318 | 1.000 | −0.506 | 0.757 | 0.569 | 0.578 | 0.960 | |

| KNN-S | −0.260 | 0.570 | 0.562 | 0.382 | 0.930 | −0.295 | 0.566 | 0.533 | 0.370 | 0.930 | −0.304 | 0.568 | 0.537 | 0.379 | 0.925 | |

| MICE-DURR(Lasso) | −0.690 | 0.576 | 0.412 | 0.645 | 0.880 | −0.392 | 0.557 | 0.404 | 0.316 | 0.945 | −0.575 | 0.574 | 0.406 | 0.495 | 0.930 | |

| MICE-DURR(EN) | −0.679 | 0.579 | 0.420 | 0.636 | 0.880 | −0.379 | 0.556 | 0.404 | 0.306 | 0.955 | −0.591 | 0.572 | 0.414 | 0.520 | 0.920 | |

| MICE-DURR(Alasso) | −0.668 | 0.616 | 0.382 | 0.592 | 0.915 | −0.393 | 0.593 | 0.391 | 0.306 | 0.970 | −0.611 | 0.611 | 0.381 | 0.519 | 0.945 | |

| MICE-IURR(Lasso) | −0.051 | 0.665 | 0.646 | 0.418 | 0.935 | −0.031 | 0.666 | 0.678 | 0.458 | 0.910 | 0.007 | 0.660 | 0.658 | 0.431 | 0.950 | |

| MICE-IURR(EN) | −0.031 | 0.665 | 0.645 | 0.415 | 0.935 | −0.057 | 0.662 | 0.660 | 0.436 | 0.930 | 0.006 | 0.659 | 0.655 | 0.427 | 0.945 | |

| MICE-IURR(Alasso) | −0.035 | 0.668 | 0.691 | 0.476 | 0.915 | −0.063 | 0.667 | 0.660 | 0.437 | 0.935 | −0.003 | 0.667 | 0.684 | 0.466 | 0.935 | |

| p = 1000 | ||||||||||||||||

| MICE-DURR(Lasso) | −0.738 | 0.582 | 0.417 | 0.717 | 0.850 | −0.408 | 0.569 | 0.417 | 0.340 | 0.955 | −0.531 | 0.586 | 0.444 | 0.478 | 0.905 | |

| MICE-DURR(EN) | −0.729 | 0.587 | 0.416 | 0.704 | 0.860 | −0.416 | 0.569 | 0.421 | 0.350 | 0.945 | −0.526 | 0.587 | 0.443 | 0.472 | 0.925 | |

| MICE-DURR(Alasso) | −0.723 | 0.614 | 0.384 | 0.670 | 0.920 | −0.433 | 0.600 | 0.374 | 0.327 | 0.950 | −0.540 | 0.612 | 0.401 | 0.451 | 0.945 | |

| MICE-IURR(Lasso) | 0.055 | 0.687 | 0.725 | 0.526 | 0.905 | −0.057 | 0.676 | 0.770 | 0.593 | 0.890 | −0.124 | 0.676 | 0.735 | 0.553 | 0.895 | |

| MICE-IURR(EN) | 0.052 | 0.675 | 0.746 | 0.556 | 0.900 | −0.053 | 0.673 | 0.782 | 0.611 | 0.910 | −0.113 | 0.669 | 0.751 | 0.573 | 0.915 | |

| MICE-IURR(Alasso) | −0.003 | 0.742 | 0.769 | 0.589 | 0.930 | −0.105 | 0.728 | 0.803 | 0.653 | 0.920 | −0.082 | 0.732 | 0.792 | 0.631 | 0.915 | |

Bias, mean bias; SE, mean standard error; SD, Monte Carlo standard deviation; MSE, mean square error; CR, coverage rate of 95% confidence interval; GS, gold standard; CC, complete-case; KNN-V, KNN by nearest variables; KNN-S, KNN by nearest subjects; MICE-DURR, MICE through direct use of regularized regressions; MICE-IURR, MICE through indirect use of regularized regressions; EN, elastic net; Alasso, adaptive lasso.

Compared with Tables 1, 2, 3 show similar patterns in terms of comparisons between the imputation methods. Among the three MICE-IURR algorithms, Alasso tends to underperform lasso and EN when  (Table 1), but not so when

(Table 1), but not so when  and

and  (Tables 2 and 3). In addition, when

(Tables 2 and 3). In addition, when  , the biases and MSEs decrease for MICE-IURR using lasso and EN and increase for MICE-IURR using Alasso, as

, the biases and MSEs decrease for MICE-IURR using lasso and EN and increase for MICE-IURR using Alasso, as  increases from 200–1000.

increases from 200–1000.

Data Examples

We illustrate the proposed methods using two data examples.

Georgia stroke registry data

Stroke is the fifth leading cause of death in the United States and a major cause of severe long-term disability. The Georgia Coverdell Acute Stroke Registry (GCASR) program is funded by Centers for Disease Control Paul S. Coverdell National Acute Stroke Registry cooperative agreement to improve the care of acute stroke patients in the pre-hospital and hospital settings. In late 2005, 26 hospitals initially participated in GCASR program and this number increased to 66 in 2013, which covered nearly 80% of acute stroke admissions in Georgia. Intravenous (IV) tissue-plasminogen activator (tPA) improves the outcomes of acute ischemic stroke patients, and brain imaging is a critical step in determining the use of IV tPA. Time plays a significant role in determining patients’ eligibility for IV tPA and their prognosis. The American Heart and American Stroke Association and CDC set a goal that hospitals should complete imaging within 25 minutes of patients arrival to a hospital. The objective of this study, thus, is to identify the factors that might be associated with hospital arrival-to-imaging time. GCASR collected data on 86,322 clinically diagnosed acute stroke admissions between 2005 and 2013. The registry has 203 data elements of which 121 (60%) have missing values, attributed to lack of answers, service not provided, poor documentation and data abstraction or ineligibility of a patient to a specific care. The extent of missingness varies from 0.01–28.72%.

In this analysis, we consider arrival-to-CT time the outcome and the other 13 variables the predictors. These 13 variables of interest can be classified into two categories: patient-related variables such as age, gender, health insurance, and medical history; pre-hospital-related variables such as EMS notification. Only gender, age and race are fully observed among 13 variables. A CC analysis is conducted which uses only 15% of the original subjects after the removal of incomplete cases. In addition, MI methods are also used. We first remove variables that have missing rate greater than 40% and the remaining variables are used to impute the missing values of partially observed variables that are of interest. After imputations, each imputed datasets of 86,322 subjects are used to fit the regression models separately and results are combined by Robin’s rules. We use a straightforward and popular strategy to handle skip pattern: first treat skipped item as missing data and impute them along with other real missing values, then restore the imputed values for skipped items back to skips in the imputed data sets to preserve skip patterns. We apply five MI methods, namely, the MICE method proposed by van Buuren et al.3 (mice), the MI method proposed by Su et al.5 (mi), the random forest MICE method proposed by Shah et al.16 (MICE-RF), and our MICE-DURR and MICE-IURR methods. When applying KNN-V and KNN-S, the R software returned errors. Thus, KNN-V and KNN-S are not included in this data example.

Table 4 provides the results from our data analyses. In the CC analysis, only NIH stroke score and race are shown to be associated with the arrival-to-CT time. The results from all five MI methods are similar in terms of the p-value and the direction of the association. By comparison, while only 2 variables are shown to be statistically significant in the CC analysis, this number increases to 11, 11, 10, 9 and 9 for mi, mice, MICE-RF, MICE-DURR, and MICE-IURR, respectively. For example, after adjusting for other variables, the mean arrival-to-CT time in patients that arrive during the day time (Day) was 18.4 minutes shorter than that in patients arriving at night ( ) based on MICE-IURR imputation. Health insurance and three variables about history of diseases become statistically significant after we apply the MI methods. However, NIH stroke score and race, which are shown to be statistically significant by CC analysis, turn out to be not significant by MICE-DURR and MICE-IURR.

) based on MICE-IURR imputation. Health insurance and three variables about history of diseases become statistically significant after we apply the MI methods. However, NIH stroke score and race, which are shown to be statistically significant by CC analysis, turn out to be not significant by MICE-DURR and MICE-IURR.

Table 4. Regression coefficients estimates of the Georgia stroke registry data.

| Characteristics | CC | mi | mice | MICE-RF | MICE-DURR | MICE-IURR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIH stroke score | −1.95 (<0.001) | −2.04 (0.010) | −6.07 (<0.001) | −5.01 (<0.001) | −1.10 (0.236) | −1.00 (0.176) |

| [−2.7, −1.2] | [−3.48, −0.6] | [−8.5, −3.64] | [−6.38, −3.63] | [−3.04, 0.84] | [−2.5, 0.49] | |

| EMS pre-notification | −3.17 (0.590) | −19.83 (0.043) | −0.82 (0.957) | −5.23 (0.604) | −2.22 (0.819) | −5.92 (0.658) |

| [−14.69, 8.35] | [−38.7, −0.96] | [−34.04, 32.4] | [−25.35, 14.9] | [−21.59, 17.14] | [−34.44, 22.59] | |

| Serum total lipid | −0.07 (0.201) | −0.47 (<0.001) | −0.52 (<0.001) | −0.36 (<0.001) | −0.26 (0.036) | −0.26 (0.005) |

| [−0.18, 0.04] | [−0.62, −0.32] | [−0.7, −0.33] | [−0.53, −0.19] | [−0.49, −0.02] | [−0.43, −0.08] | |

| Age | 0.02 (0.936) | −0.87 (0.022) | −0.78 (0.042) | −0.71 (0.061) | −0.76 (0.045) | −0.80 (0.037) |

| [−0.51, 0.56] | [−1.62, −0.12] | [−1.53, −0.03] | [−1.46, 0.03] | [−1.51, −0.02] | [−1.54, −0.05] | |

| Male(referent: female) | 5.33 (0.372) | 21.20 (0.013) | 24.83 (0.004) | 19.15 (0.025) | 16.57 (0.053) | 16.54 (0.053) |

| [−6.37, 17.02] | [4.41, 37.98] | [8, 41.66] | [2.41, 35.89] | [−0.24, 33.38] | [−0.19, 33.27] | |

| White(referent: African American) | −16.64 (0.007) | −14.44 (0.107) | −20.07 (0.028) | −17.64 (0.048) | −14.11 (0.114) | −13.85 (0.121) |

| [−28.82, −4.45] | [−32.01, 3.14] | [−37.98, −2.15] | [−35.16, −0.12] | [−31.62, 3.41] | [−31.34, 3.65] | |

| Health insurance by medicare | −4.07 (0.617) | −24.95 (0.032) | −24.89 (0.032) | −24.35 (0.036) | −24.36 (0.036) | −24.05 (0.038) |

| [−20.04, 11.9] | [−47.72, −2.19] | [−47.7, −2.08] | [−47.13, −1.57] | [−47.11, −1.6] | [−46.8, −1.3] | |

| Arrive in the daytime | 4.94 (0.420) | −23.10 (0.011) | −24.64 (0.006) | −10.27 (0.275) | −18.97 (0.043) | −18.41 (0.045) |

| [−7.07, 16.96] | [−40.89, −5.31] | [−42.35, −6.94] | [−28.74, 8.2] | [−37.38, −0.56] | [−36.39, −0.42] | |

| NPO | 8.37 (0.393) | 58.79 (0.001) | 121.04 (<0.001) | 81.03 (0.001) | 39.98 (0.006) | 43.31 (0.001) |

| [−10.84, 27.58] | [26.65, 90.93] | [76.21, 165.88] | [39.6, 122.45] | [11.87, 68.08] | [17.25, 69.37] | |

| History of stroke | −2.57 (0.695) | −36.55 (0.001) | −34.10 (0.002) | −28.99 (0.009) | −31.96 (0.008) | −33.24 (0.002) |

| [−15.43, 10.29] | [−57.15, −15.96] | [−55.86, −12.35] | [−50.72, −7.27] | [−55.52, −8.41] | [−54.47, −12] | |

| History of TIA | −16.30 (0.097) | −64.53 (<0.001) | −89.47 (<0.001) | −64.94 (<0.001) | −62.39 (<0.001) | −60.34 (<0.001) |

| [−35.54, 2.94] | [−95.93, −33.13] | [−123.95, −55] | [−97.47, −32.41] | [−96.59, −28.19] | [−92.47, −28.2] | |

| History of cardiac valve prosthesis | −27.25 (0.349) | 89.28 (0.016) | 136.94 (<0.001) | 126.22 (0.022) | 103.18 (0.008) | 104.15 (0.007) |

| [−84.27, 29.78] | [16.98, 161.59] | [79.4, 194.48] | [19.67, 232.77] | [27.19, 179.16] | [28.31, 179.98] | |

| Family history of stroke | −17.33 (0.406) | −85.07 (0.014) | −51.10 (0.078) | −82.91 (0.022) | −79.79 (0.028) | −76.82 (0.034) |

| [−58.18, 23.51] | [−153.23, −16.92] | [−107.91, 5.72] | [−153.95, −11.87] | [−150.94, −8.65] | [−147.91, −5.74] |

KNN-V and KNN-S are not included because of errors. NPO, nil per os, Latin for “nothing by mouth”, a medical instruction to withhold oral intake of food and fluids from a patient. P-value, (); 95% confidence interval, [].

Prostate cancer data

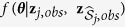

The second data set is from a prostate cancer study (GEO GDS3289). It contains 99 samples, including 34 benign epithelium samples and 65 non-benign samples, with 20,000 genomic biomarkers. Missing values are present for 17,893 biomarkers, nearly 89% of all genomic biomarkers in this data set. In this analysis, we consider a binary outcome  , defined as

, defined as  if it is a benign sample and

if it is a benign sample and  if otherwise, and test whether some genomic biomarkers are associated with the outcome. For the purpose of illustration, we choose three biomarkers (FAM178A, IMAGE:813259 and UGP2), for which the missing rates are 31.3%, 45.5% and 26.3%, respectively. We conduct a logistic regression of

if otherwise, and test whether some genomic biomarkers are associated with the outcome. For the purpose of illustration, we choose three biomarkers (FAM178A, IMAGE:813259 and UGP2), for which the missing rates are 31.3%, 45.5% and 26.3%, respectively. We conduct a logistic regression of  on the three biomarkers. In this analysis, mi and mice packages give error messages and MICE-RF approach is computationally very expensive. Therefore, we only use our two proposed MI methods (MICE-DURR and MICE-IURR) and the KNN-V and KNN-S methods in addition to the complete-case analysis. All 2107 biomarkers that do not have missing values are used to impute missing values in the three biomarkers.

on the three biomarkers. In this analysis, mi and mice packages give error messages and MICE-RF approach is computationally very expensive. Therefore, we only use our two proposed MI methods (MICE-DURR and MICE-IURR) and the KNN-V and KNN-S methods in addition to the complete-case analysis. All 2107 biomarkers that do not have missing values are used to impute missing values in the three biomarkers.

Table 5 presents the results on logistic regression for the prostate cancer data. Based on our results, all three biomarkers become statistically significant after using our multiple imputation methods, except in one case that the p-value of UGP2 after MICE-DURR method is slightly larger than 0.05. In addition, in most cases, the estimates and p-values by MICE-DURR are consistent with those results by MICE-IURR. For example, the regression coefficients of biomarker (IMAGE:813259) after using two different multiple imputations (MICE-DURR and MICE-IURR) are 3.47 and 3.50, with p-values of 0.031 and 0.039, respectively.

Table 5. Regression coefficients estimates of the prostate cancer data.

| Biomarkers | CC | KNN-V | KNN-S | MICE-DURR | MICE-IURR | Missing-rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAM178A | 5.80 (<0.119) | 5.62 (<0.001) | 5.33 (0.001) | 4.43(0.003) | 4.70(0.002) | 31.3% |

| [−1.49, 13.09] | [2.62, 8.62] | [2.31, 8.35] | [1.61, 7.25] | [1.76, 7.64] | ||

| IMAGE:813259 | 6.03 (0.151) | 4.20 (0.009) | 4.43 (0.016) | 3.47 (0.031) | 3.50 (0.039) | 45.5% |

| [−2.2, 14.26] | [1.06, 7.34] | [0.82, 8.04] | [0.37, 6.57] | [0.23, 6.77] | ||

| UGP2 | −2.57 (0.386) | −3.44 (0.021) | −3.45 (0.021) | −2.32 (0.067) | −3.15 (0.025) | 26.3% |

| [−8.37, 3.23] | [−6.36, −0.52] | [−6.37, −0.53] | [−4.77, 0.13] | [−5.85, −0.45] |

MICE-RF is not included because of errors. P-value, (); 95% confidence interval, [].

Discussion

We investigate two approaches for multiple imputation for general missing data patterns in the presence of high-dimensional data. Our numerical results demonstrate that the MICE-IURR approach performs better than the other imputation methods considered in terms of bias, whereas the MICE-DURR approach exhibits large bias and MSE. Of note, while MICE-RF leads to substantial bias in subsequent analysis of imputed data sets, it tends to yield smaller MSE than MICE-IURR due to smaller SD. In the case of comparing multiple imputation methods, it can be argued when one imputation method leads to substantial bias and hence incorrect inference in subsequent analysis of imputed data sets then whether this method yields smaller MSE may not be very relevant. Two data examples are used to further showcase the limitations of the existing imputation methods considered.

As alluded to earlier, while MICE is a flexible approach for handling different data types, its theoretical properties are not well-established. The specification of a set of conditional regression models may not be compatible with a joint distribution of the variables being imputed. Liu et al. (2013)27 established technical conditions for the convergence of the sequential conditional regression approach if the stationary joint distribution exists, which, however, may not happen in practice. Zhu and Raghunathan (2014)28 assessed theoretical properties of MI for both compatible and incompatible sequences of conditional regression models. However, their results are established for the missing data pattern where each subject may have missing values in at most one variable. One direction for future work is to extend these results to the settings of our interest.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Deng, Y. et al. Multiple Imputation for General Missing Data Patterns in the Presence of High-dimensional Data. Sci. Rep. 6, 21689; doi: 10.1038/srep21689 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a PCORI award (ME-1303-5840). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the PCORI.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Q.L. conceived the idea. Q.L. and Y.D. developed the methods. Y.D. performed the simulations and the data analyses. M.I. provided the GCASR data. Y.D., C.C., M.I. and Q.L. contributed to writing.

References

- Rubin D. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys (Wiley, New York, 1987). [Google Scholar]

- Little R. & Rubin D. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data (John Wiley, New York, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- van Buuren S. & Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw 45(3), 1–67 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Raghunathan T., Lepkowski J., Van Hoewyk J. & Solenberger P. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Surv Methodol 27, 85–96 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Su Y., Gelman A., Hill J. & Yajima M. Multiple imputation with diagnostics (mi) in R: Opening windows into the black box. J Stat Softw 45(2), 1–31 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Harel O. & Zhou X.-H. Multiple imputation for the comparison of two screening tests in two-phase alzheimer studies. Stat Med 26, 2370–2388 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Yucel R. & Raghunathan T. A functional multiple imputation approach to incomplete longitudinal data. Stat Med 30, 1137–1156 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C., Taylor J., Murray S. & Commenges D. Survival analysis using auxiliary variables via nonparametric multiple imputation Stat Med 25, 3503–3517 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little R. & An H. Robust likelihood-based analysis of multivariate data with missing values. Stat Sin 14, 949–968 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Long Q., Hsu C. & Li Y. Doubly robust nonparametric multiple imputation for ignorable missing data. Stat Sin 22, 149–172 (2012). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi L., Wang Y.-F. & He Y. A comparison of multiple imputation and fully augmented weighted estimators for cox regression with missing covariates. Stat Med 29, 2592–2604 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G. & Little R. Extensions of the penalized spline of propensity prediction method of imputation. Biometrics 65, 911–918 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X.-L. Multiple-imputation inferences with uncongenial sources of input. Stat Sci 9, 538–558 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Stekhoven D. J. & Bühlmann P. MissForest–non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics 28, 112–118 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn 45, 5–32 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Shah A. D., Bartlett J. W., Carpenter J., Nicholas O. & Hemingway H. Comparison of random forest and parametric imputation models for imputing missing data using mice: a caliber study. Am J Epidemiol 179, 764–774 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao S. G. et al. Missing value imputation in high-dimensional phenomic data: imputable or not, and how? BMC Bioinformatics 15, 346 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marimont R. & Shapiro M. Nearest neighbour searches and the curse of dimensionality. IMA J Appl Math 24, 59–70 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- Stone C. J. Optimal rates of convergence for nonparametric estimators. Ann Stat 8, 1348–1360 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. & Long Q. Multiple imputation in the presence of high-dimensional data. Stat Methods Med Res, doi: 10.1177/0962280213511027 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol 58, 267–288 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Zou H. & Hastie T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol 67, 301–320 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Zou H. The adaptive lasso and its oracle properties. J Am Stat Assoc 101, 1418–1429 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J. L. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data (CRC press, 1997). [Google Scholar]

- Raghunathan T. E. & Siscovick D. S. A multiple-imputation analysis of a case-control study of the risk of primary cardiac arrest among pharmacologically treated hypertensives. J R Stat Soc Ser C Appl Stat 45, 335–352 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res 16, 219–242 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Gelman A., Hill J., Su Y.-S. & Kropko J. On the stationary distribution of iterative imputations. Biometrika 101, 155–173 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J. & Raghunathan T. E. Convergence properties of a sequential regression multiple imputation algorithm. J Am Stat Assoc 110, 1112–1124 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- White I. R., Royston P. & Wood A. M. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med 30, 377–399 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen S. F. Proper and improper multiple imputation. Int Stat Rev 71, 593–607 (2003). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.