Abstract

Sirtuins are evolutionarily conserved NAD-dependent deacetylases that catalyze the cleavage of NAD+ into nicotinamide (NAM), which can act as a pan-sirtuin inhibitor in unicellular and multicellular organisms. Sirtuins regulate processes such as transcription, DNA damage repair, chromosome segregation, and longevity extension in yeast and metazoans. The founding member of the evolutionarily conserved sirtuin family, SIR2, was first identified in budding yeast. Subsequent studies led to the identification of four yeast SIR2 homologs HST1, HST2, HST3, and HST4. Understanding the downstream physiological consequences of inhibiting sirtuins can be challenging since most studies focus on single or double deletions of sirtuins, and mating defects in SIR2 deletions hamper genome-wide screens. This represents an important gap in our knowledge of how sirtuins function in highly complex biological processes such as aging, metabolism, and chromosome segregation. In this report, we used a genome-wide screen to explore sirtuin-dependent processes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by identifying deletion mutants that are sensitive to NAM. We identified 55 genes in total, 36 of which have not been previously reported to be dependent on sirtuins. We find that genome stability pathways are particularly vulnerable to loss of sirtuin activity. Here, we provide evidence that defects in sister chromatid cohesion renders cells sensitive to growth in the presence of NAM. The results of our screen provide a broad view of the biological pathways sensitive to inhibition of sirtuins, and advance our understanding of the function of sirtuins and NAD+ biology.

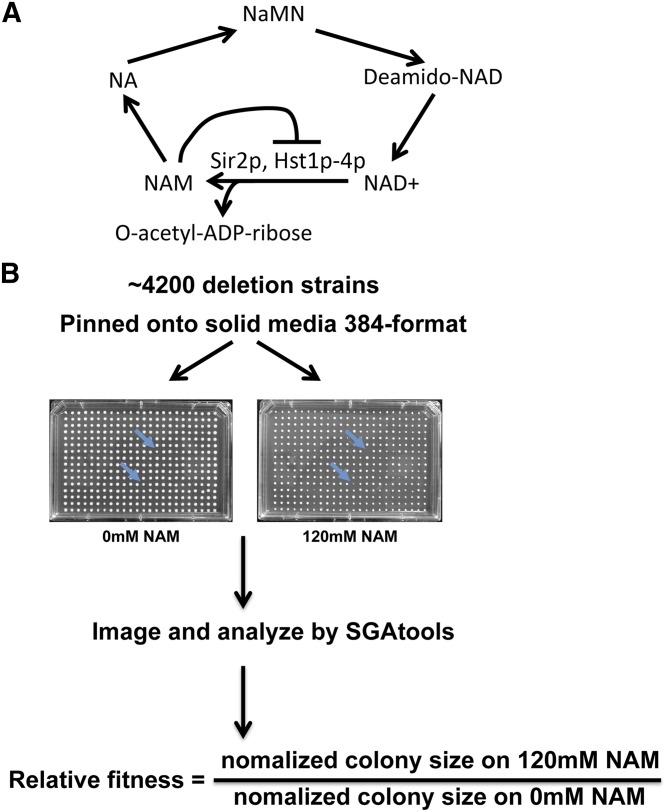

Sirtuins are class III NAD-dependent deacetylases that serve key roles in the assembly of repressive chromatin structures, genome integrity, chromosome segregation, and are the targets of caloric restriction-mediated longevity extension in some systems (Aparicio et al. 1991; Nasmyth 1982; Rine and Herskowitz 1987; Lin et al. 2000; Holmes et al. 1997; Tissenbaum and Guarente 2001; Pillus and Rine 1989; Choy et al. 2011). Sirtuin-catalyzed deacetylation is coupled with the cleavage of NAD+ into nicotinamide (NAM) and 2′O-acetyl ADP-ribose (Figure 1A). Moreover, NAM is an effective pan-sirtuin noncompetitive inhibitor in both single celled eukaryotes and metazoans (Avalos et al. 2005; Zhao et al. 2004). Thus, the balance between NAD+ and NAM levels can modulate the activity of sirtuins and influence a range of biological functions. NAM has been shown to influence tumorigenesis in mice and humans as well as alleviating Alzheimer’s-associated pathologies in mice (Yiasemides et al. 2009; Gupta 1999; Gotoh et al. 1988; Bryan 1986; Zhang et al. 2013; Gong et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2013). Inhibition of sirtuins is thought to underlie the efficacy of some NAM-based therapies but the precise mechanism of NAM action and the downstream targets of sirtuins remains unclear in many cases. Therefore, elucidation of pathways/genes that are affected by NAM is crucial for understanding pathways that are dependent on sirtuin activity and may help to identify therapeutic targets for sirtuin-related diseases.

Figure 1.

A genome-wide screen for identifying deletion mutants sensitive to NAM. (A) Diagram showing the general pathway utilized by yeast to generate nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+). Sirtuins use NAD+ as a cofactor and generate nicotinamide (NAM) as well as 2′O-acetyl ADP-ribose during a single deacetylation event. NAM can be converted to nicotinic acid (NA), which in turn is used to generate nicotinic acid mononucleotide (NaMN). Next, NaMN is converted to Deamido-NAD, and in turn NAD+ is regenerated. (B) Approach used to screen and score deletion mutants that are sensitive to NAM. A collection of ∼4200 yeast deletion mutants were arrayed in 384-format on YPD agar containing 0 or 120 mM NAM. Arrows indicate examples of the fitness defect observed in NAM sensitive mutants. Relative fitness was determined from normalized colony sizes obtained by analysis of plate images using SGAtools.

Budding yeast, which has five sirtuins (SIR2, HST1, HST2, HST3, HST4), provides an effective model system to study sirtuin biology (Blander and Guarente 2004; Smith et al. 2002). Sir2p is the prototypic sirtuin, first discovered in yeast, that regulates chromatin structure by deacetylating key acetylated lysine residues found on histone H3 and H4 (Smith et al. 2002). Yeast treated with NAM display defects in transcriptional silencing, hyper-recombination at the rDNA locus, sister chromatid cohesion, and have reduced lifespan (Tripathi et al. 2012; Gallo et al. 2004; Anderson et al. 2003; Thaminy et al. 2007). We previously reported that mutants in the yeast centromeric specific histone, CSE4, are sensitized to NAM and treatment of wild-type cells with NAM increases the frequency of chromosome loss (Choy et al. 2011). Studies have shown that yeast treated with NAM have a reduced replicative lifespan that is associated with hyper-acetylation of histone H3K56 and H4K16, in part through inhibition of Sir2p (Bitterman et al. 2002; Hachinohe et al. 2011; Choy et al. 2011). In addition, assembly of sister-chromatid cohesion and DNA damage repair are promoted by Hst3p- and Hst4p-mediated deacetylation of H3K56, demonstrating shared substrates among yeast sirtuins and the importance of histone acetylation/deacetylation in genome maintenance mechanisms (Maas et al. 2006; Celic et al. 2006, 2008; Thaminy et al. 2007). This redundancy can obfuscate the identification of sirtuin-dependent biological processes using single or double sirtuin deletions. Moreover, genome-wide approaches to investigate the myriad of biological activities using multiple deletions in sirtuins, which include SIR2, require a method to bypass the sir2Δ mating defect (Rine and Herskowitz 1987; Shore et al. 1984; Ivy et al. 1986; Liu et al. 2010). To circumvent these limitations, we used NAM at a concentration that inhibits all five sirtuins in a genome-wide screen to identify gene deletions that confer sensitivity to NAM. Here, we report the results of our screen and provide novel insights into biological processes that are dependent on sirtuin activity.

Materials and Methods

Genome-wide screen to identify gene deletions sensitive to NAM

A Saccharomyces cerevisiae library of deletions in ∼4200 nonessential genes in BY4741 was generously provided by the Boone laboratory (Toronto, Canada). A VersArray Colony Arrayer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) equipped with a 384-pinning head was used to array out the library on 15 YPD agar plates, using Omni plates from Nunc, and allowed to grow at 30° for 3 d. Colonies were then pinned onto fresh YPD plates or YPD + 120 mM NAM (N3376 from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) plates, incubated for 3 d at 30°, then imaged with a Nikon digital camera. Images were analyzed by SGAtools as described below. Strains available upon request.

Quantitative analysis of genome-wide screen

Images of all plates were analyzed using SGAtools (sgatools.ccbr.utoronto.ca) (Wagih et al. 2013). Ratios of normalized colony sizes from NAM treated and untreated mutants were used as a measure of sensitivity. Normalized colony sizes were used to determine sensitivity by comparing growth on YPD vs. YPD + 120 mM NAM. The screen was performed twice and Table 1 indicates the score obtained for each screen. The raw scores for all mutants from both replicate screens are found in Supporting Information, Table S2 and Table S3.

Table 1. Scores for the top 59 mutants from genome-wide screen.

| ORF | Gene Name | Screen 1 | Screen 2 | Average Score | Genome Stabilitya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOS1 | YHL031C | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.18 | |

| SMI1 | YGR229C | 0.31 | 0.42 | 0.37 | |

| SRB2 | YHR041C | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | + |

| BUB1 | YGR188C | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.20 | + |

| FBP26 | YJL155C | 0.09 | 0.24 | 0.17 | + |

| MPH1 | YIR002C | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.24 | + |

| POL32 | YJR043C | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.26 | + |

| LAS21 | YJL062W | 0.32 | 0.41 | 0.36 | |

| SWF1 | YDR126W | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.02 | |

| TOP3 | YLR234W | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.27 | + |

| VPS53 | YJL029C | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.14 | + |

| UBP3 | YER151C | 0.39 | 0.24 | 0.32 | + |

| YDR455C | YDR455C | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.30 | |

| HHY1 | YEL059W | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.31 | |

| RAD51 | YER095W | 0.15 | 0.45 | 0.30 | + |

| BST1 | YFL025C | 0.28 | 0.50 | 0.39 | |

| SPF1 | YEL031W | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.40 | |

| RPO41 | YFL036W | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.41 | |

| RPL19B | YBL027W | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.23 | |

| MRC1 | YCL061C | 0.37 | 0.19 | 0.28 | |

| SLX5 | YDL013W | 0.37 | 0.36 | 0.37 | + |

| PER1 | YCR044C | 0.19 | 0.46 | 0.32 | + |

| RIC1 | YLR039C | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.28 | |

| SWI6 | YLR182W | 0.20 | 0.33 | 0.27 | |

| YJL175W | YJL175W | 0.18 | 0.49 | 0.33 | |

| BUB3 | YOR026W | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.13 | |

| DIA2 | YOR080W | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.34 | + |

| PAP2 | YOL115W | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.29 | + |

| VAM3 | YOR106W | 0.20 | 0.35 | 0.27 | |

| VAM10 | YOR068C | 0.17 | 0.42 | 0.30 | |

| SHE4 | YOR035C | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.32 | |

| TLG2 | YOL018C | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.45 | |

| YPT6 | YLR262C | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.20 | |

| ARC1 | YGL105W | 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.24 | |

| COG8 | YML071C | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.20 | + |

| YMR031W-A | YMR031W-A | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.10 | |

| YNL171C | YNL171C | 0.37 | 0.21 | 0.29 | |

| YMR166C | YMR166C | 0.14 | 0.48 | 0.31 | |

| COG6 | YNL041C | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.25 | |

| SAC1 | YKL212W | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.02 | |

| CPS1 | YJL172W | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.41 | |

| RPE1 | YJL121C | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.17 | |

| HTZ1 | YOL012C | 0.41 | 0.48 | 0.44 | |

| JHD2 | YJR119C | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.32 | + |

| DPB3 | YBR278W | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.41 | |

| EAF1 | YDR359C | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.21 | + |

| MNN10 | YDR245W | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.13 | + |

| PPH3 | YDR075W | 0.31 | 0.19 | 0.25 | |

| SPT3 | YDR392W | 0.05 | 0.34 | 0.20 | + |

| SWI4 | YER111C | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.19 | |

| SNX4 | YJL036W | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.26 | + |

| ASC1 | YMR116C | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.17 | |

| COG7 | YGL005C | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.21 | + |

| VAM7 | YGL212W | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.11 | |

| DBF2 | YGR092W | 0.12 | 0.46 | 0.29 | + |

| CKB1 | YGL019W | 0.27 | 0.47 | 0.37 | |

| LEA1 | YPL213W | 0.40 | 0.24 | 0.32 | |

| VPS1 | YKR001C | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| ERG3 | YLR056W | 0.38 | 0.27 | 0.33 |

Genome stability (+) indicates that the respective gene has been reported to have function(s) in pathway(s) important for maintaining genome integrity.

Growth assays to validate results from genome-wide screens

Yeast media and techniques were performed as described (Guthrie and Fink 1991). Yeast strains for growth assays were from the deletion collection (described in Genome-wide screen) provided by Dr. Charles Boone or as indicated in Table S6. Cultures of each strain were grown overnight in 96-well plates, serially diluted five-fold, and then 3–4 μl of each dilution was spotted onto agar plates and grown at the indicated temperatures. Typically, plates were imaged after 3–5 d of incubation at the indicated temperatures. Shown are representative spot tests from three independent replicate assays. Yeast strains are described in Table S6.

Gene ontology mapper

Generic Gene Ontology (GO) Term Mapper (go.princeton.edu/cgi-bin/GOTermMapper) was used to bin the 55 top scoring genes into GO terms (Boyle et al. 2004). The results are plotted in Figure 3. GeneMANIA (genemania.org) was used to analyze the reported genetic and physical interactions for the 55 top scoring genes shown in Figure 4 (Zuberi et al. 2013).

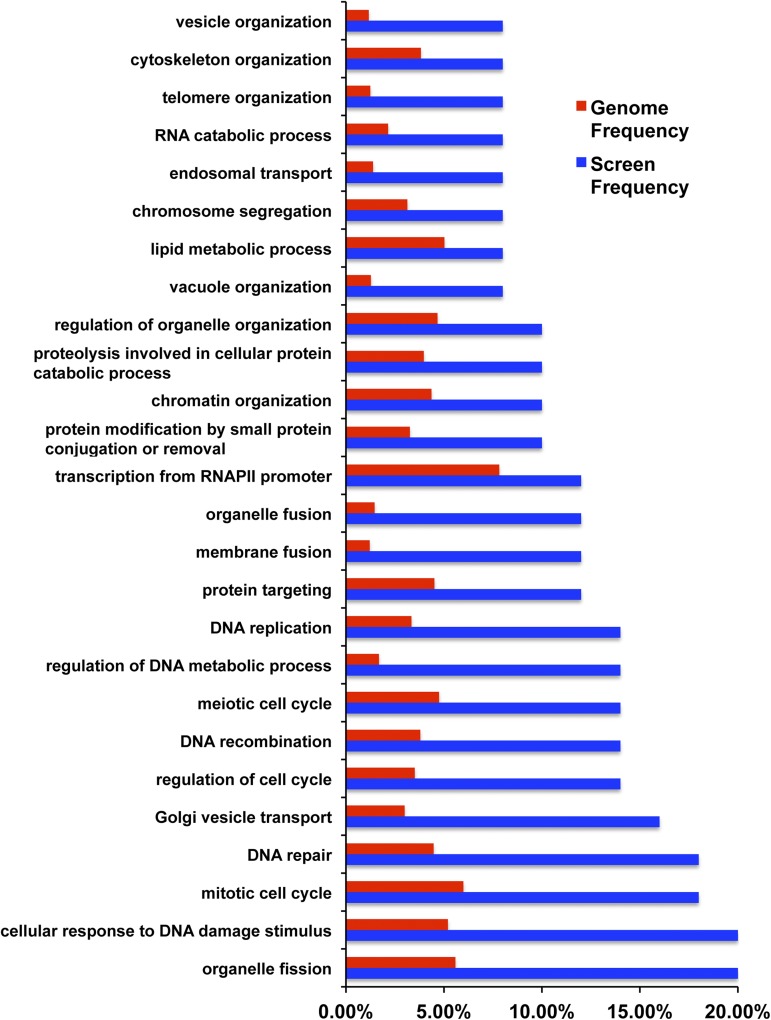

Figure 3.

Gene Ontology (GO) Term Mapper indicates a variety of processes affected by nicotinamide (NAM) treatment. The 55 most sensitive deletions are in genes with nuclear functions such as DNA replication and repair, and mitosis. A subset of these deletions is in genes with functions in lipid metabolism and organelle organization. Screen frequency (blue) and genome frequency (red) represent the frequency of observing genes with the respective GO terms on the y-axis. Note that the frequency of occurrence of genes in a given category, except for RNA polymerase II transcription, is several fold higher in our screen compared to the genome.

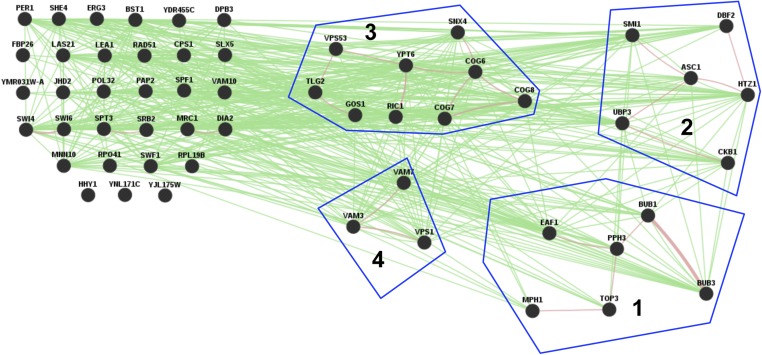

Figure 4.

Genetic and physical interactions between the highest scoring 55 genes. Green and pink edges indicate genetic and physical interactions, respectively. Groups 1, 2, 3, and 4 indicate physical interaction networks within a subset of the proteins encoded by their respective genes. Genetic and physical interactions were determined using GeneMANIA to analyze the top 55 scoring genes.

Results and Discussion

Genome-wide screen for mutants that are sensitive to NAM

NAM is a precursor molecule used to synthesize NAD+ and an inhibitor of sirtuins both in vivo and in vitro (Figure 1A) (Kato and Lin 2014). To gain a better understanding of pathways regulated by NAM and sirtuins, we performed a genome-wide screen to identify gene deletion strains that displayed sensitivity to sublethal levels of NAM. We screened a collection of deletions in ∼4200 nonessential genes in 384-format on YPD agar plates containing either no NAM or 120 mM NAM (Figure 1B). The screen was performed twice and plates were incubated at 30° for 2–3 d and then imaged. We used SGAtools to quantify and analyze the colony sizes of strains grown in the absence or presence of NAM (Wagih et al. 2013). Ratios of normalized colony sizes between NAM treated and control plates were calculated, and mutants with ratios ≤0.5 were selected as sensitive if they scored similarly in both replicate screens (Table 1, Table S1, Table S2, and Table S3). Based on this criterion, a total of 59 mutants were considered sensitive (Table 1).

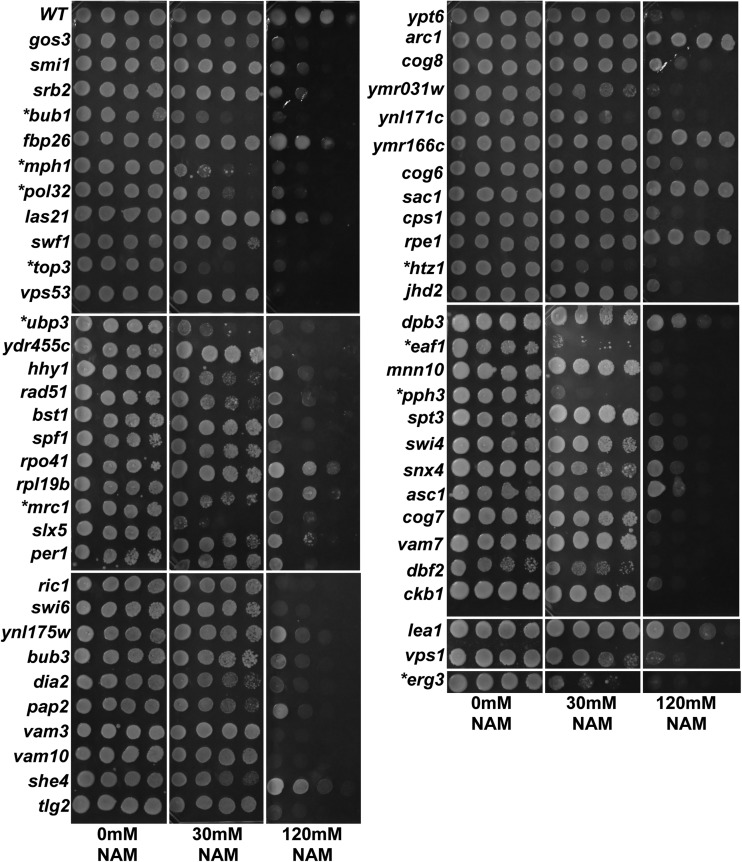

To validate the results of the screen, we performed growth assays using spot tests for each of the 59 deletions. We observed a high rate of true positives in which 55/59 of the mutants tested confirmed their respective sensitivity to 120 mM NAM. Only deletions in ARC1, YMR166C, SAC1, and RPE1 displayed no compromise in growth on NAM (Figure 2). In addition, we found that 16% of mutants (UBP3, HTZ1, MRC1, EAF1, PPH3, BUB1, MPH1, POL32, VPS1, ERG3) displayed marked growth sensitivity even in the presence of much lower concentrations of NAM (30 mM) (Figure 2). Gene Ontology Term Mapper of the 55 sensitive mutants indicated that categories related to mitotic cell cycle, DNA repair, replication, and recombination were highly represented (Figure 3 and Table S5). We note that organelle fission is also highly represented but nearly every gene in that category is known to function in the spindle assembly checkpoint or in DNA damage repair and recombination (Table S5). These results suggest that disruption of pathways that preserve genomic integrity render cells highly vulnerable to excess NAM. In addition, we found that only 19 of the 55 genes we identified have been previously reported to exhibit a negative genetic interaction with any individual sirtuin deletion strain, and nearly 62% (34/55) of genes have human homologs based on YeastMine (Table S4) (Balakrishnan et al. 2012). These results suggest that sirtuin-dependent pathways are evolutionarily conserved and may yield critical insights into sirtuin biology in humans. Analysis by GeneMANIA, which provides information on functional association between genes of interest, revealed that over 50% (30/55) of the encoded gene products are reported to have physical interactions with each other, 24 being grouped into one of four physical interaction networks with at least three or more members (Figure 4). Most of the highly sensitive mutants (UBP3, HTZ1, EAF1, PPH3, BUB1, MPH1, VPS1) were also found within each of the four physical interaction networks. There are a large number of genetic interactions between these 55 genes that are not part of the physical interaction networks, suggesting that many have overlapping functions (Figure 4). Moreover, a subset of mutants found in interaction network 1 (BUB1, BUB3, TOP3) support a possible role for sirtuins in the regulation of sister chromatid cohesion, which is essential for faithful chromosome segregation.

Figure 2.

Growth assays for sensitivity of deletion mutants to increasing concentrations of NAM. Nearly 90% of mutants initially identified in the screen show greater sensitivity to 120 mM nicotinamide (NAM) compared to a wild-type control (WT). Scores for the growth in the genome-wide screen for each strain are shown in Table 1. A subset of mutants is considered highly sensitive when there is a loss of viability even at 30 mM NAM. Asterisks indicate the most sensitive mutants. Three biological replicates were done and results were similar for all three experiments. Overnight cultures of each deletion strain were serially diluted five-fold and 3 μl were spotted on indicated media and incubated at 30°C for 2–3 d.

Gene deletions for NAM sensitivity form physical interaction networks

Twenty-eight of the 55 genes identified in the NAM screen can be classified into four physical networks, representing either genes required for genome stability and the DNA damage response (networks 1 and 2) or Golgi and vacuolar functions (networks 3 and 4) (Figure 4). Although the genes that comprise networks 3 and 4 have well-established roles in Golgi and vacuolar functions, they nonetheless might have important roles in the DNA damage response pathway. For example, gene deletions in Golgi and vacuolar functions not only exhibit defects in these pathways but also show sensitivity to DNA damaging agents (Costanzo et al. 2014; Skrzypek and Hirschman 2011). Furthermore, negative genetic interactions have been reported between deletions in Golgi/vacuolar genes and mutations in genes with functions in genome stability (Costanzo et al. 2014; Skrzypek and Hirschman 2011). Thus, all four networks likely have important roles in genome integrity mechanisms.

Physical interaction network 1: genomic stability

Within this network there are seven genes (BUB1, BUB3, PPH3, EAF1, TOP3, and MPH1) with functions in genomic stability (Figure 4A). Bub1p and Bub3p form a key kinase complex that regulates the spindle assembly checkpoint and centromeric recruitment of the cohesion Sgo1p to ensure faithful chromosome segregation (Hoyt et al. 1991; Kawashima et al. 2010). Top3p is the catalytic subunit of a trimeric complex that associates with Rmi1p and Sgs1p to form the topoisomerase III complex, which resolves recombination intermediates and plays a role in chromosome cohesion assembly (Lai et al. 2007). Eaf1p is a component of the NuA4 histone acetyltransferase complex that acts as a platform where subunits of NuA4 assemble and function in transcription and DNA damage repair (Auger et al. 2008). Mph1p encodes a 3′-5′ DNA helicase similar to the human Fanconi anemia group protein that regulates error-free bypass of DNA lesions (Zheng et al., 2011).

Physical interaction network 2: DNA repair, protein trafficking, and translation

Within this network there are eight genes (CKB1, UBP3, ASC1, SMI1, HTZ1, DBF2) that function in DNA damage repair, protein trafficking, and translation (Figure 4A).

Ckb1p is the regulatory subunit of casein kinase 2, which functions in transcription of RNA PolIII genes that can be activated during DNA damage (Guillemain et al. 2007). Ubp3p is an ubiquitin protease with functions in transport between the ER and Golgi and its protein levels increase as a result of replication stress (Cohen et al. 2003; Bilsland et al. 2007; Tkach et al. 2012). Asc1p is the yeast ortholog of RACK1 (receptor for activated protein kinase C1) and is a component of the 40S ribosomal subunit that acts as a translational inhibitor. It also functions as a G-protein β subunit for G alpha protein, Gpa2, and can bind to adenylate cyclase, thereby decreasing cAMP production (Zeller et al. 2007; Tkach et al. 2012; Coyle et al. 2009). Smi1p regulates cell wall synthesis and coordinates its synthesis with cell cycle progression (Martin-Yken et al. 2003). HTZ1 encodes a histone H2A variant (H2AZ) that has important functions in transcriptional regulation, while the SWR1 complex mediates exchange of canonical H2A for H2AZ at promoter sites (Mizuguchi et al. 2004; Zhang et al. 2005). H2AZ has been proposed to play a role in centromeric chromatin and in DNA damage repair (Van et al. 2015; Krogan et al. 2004). Dbf2p is a kinase that functions in the mitotic exit network and in stress responses (Lee et al. 2001).

Physical interaction network 3: Golgi transport/traffic

This network is comprised of a group of nine genes (COG6, COG7, COG8, SNX4, YPT6, RIC1, VPS53, TLG2, and GOS1) which have functions primarily related to Golgi transport/traffic (Figure 4A). Cog4p, Cog6p, and Cog7p are part of a multi-subunit cytosolic tethering complex that traffics protein to mediate the fusion of vesicles to the Golgi (Kudlyk et al. 2013; Loh and Hong 2004). Snx4p is a member of the sorting nexin family that functions in cytoplasm-to-vacuole protein transport and in autophagy (Hettema et al. 2003). Ypt6p is a Ras-like GTP binding protein that is required for vesicle fusion with the late Golgi (Luo and Gallwitz 2003). Ric1p is involved with retrograde transport to the cis-Golgi and together with Rgp1p acts as a Ypt6p GTP exchange factor (Siniossoglou et al. 2000). Vps53p is one of four subunits that comprise the GARP (Golgi-associated retrograde protein) complex that recycles proteins from endosomes to the late Golgi and is involved with DNA damage arrest recovery (Conibear et al. 2003). Tlg2p is one subunit of a trimeric complex that mediates fusion of vesicles derived from endosomes with the late Golgi (Abeliovich et al. 1998). Gos1p is a v-SNARE protein that functions in Golgi transport (McNew et al. 1998).

Physical interaction network 4: vacuolar trafficking

This is the smallest network composed of three genes (VPS1, VAM3, VAM7) that are critical for vacuolar trafficking (Figure 4A). Vps1p is a dynamin-like GTPase that plays a role in vacuolar sorting, endocytosis, and peroxisome biogenesis (Ekena et al. 1993). Vam3p and Vam7p are vacuolar SNARE proteins that function together in vacuolar trafficking (Sato et al. 1998).

Genes encoding proteins that are not members of physical interaction networks 1–4

Twenty-seven of the 55 genes identified in the NAM screen do not fit within the four physical interaction networks (Figure 4). Based on information from the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD), five of the 27 genes are predicted to be dubious ORFs as they overlap with verified ORFs. Nonetheless, many genetic interactions are present between all 27 genes, between each other, and within the other 28 genes (Figure 4). Importantly, nearly a third of these genes (ERG3, PAP2, SWI4, SWI6, DPB3, DIA2, MRC1, SLX5, RAD51, POL32) have functions in DNA replication and repair (Table 1). This further supports the possibility that NAM treatment affects genome integrity. The remaining 16 verified genes encode proteins with functions in organelle trafficking/transport/morphogenesis (BST1, CPS1, SPF1, SWF1, HHY1, SHE4, VAM10), anabolic processes such as lipid and GPI synthesis (LAS21, PER1), gluconeogenesis (FBP26, MNN10), translation/RNA processing (LEA1, RPL19B), and transcription (SPT3, SRB2, JHD2) (Table 1 and Table S1). As indicated by SGD, there are genetic interactions between these genes and the DNA replication/repair genes suggesting that they may be operating directly or indirectly in genome integrity mechanisms.

The five deletions that occur in dubious ORFs are YDR455C, YMR031W-A, YNL171C, YJL175W, and YPR050C. Information for each of the five dubious ORFs was obtained from SGD. It is likely that replacement of the dubious ORF by kanMX disrupts the overlapping verified ORF. Deletion of YDR455C removes the first 196 bp of NHX1, which encodes a Na+/H+ and K+/H+ exchanger. YMR031W-A overlaps with the first 34 bp of EIS1, which encodes a component of the eisosome. YNL171C overlaps with 153 bp of the very end of APC1, encoding the largest subunit of the anaphase-promoting complex. YJL175W overlaps with 481 bp of the beginning of SWI3 transcription factor. YPR050C nearly overlaps completely with MAK3 (beginning at 7 bp of the 5′-end and ending at 124 bp before the end of MAK3), the catalytic subunit of N-terminal acetyltransferase. The data from large-scale studies indicates that deletions in all of these dubious ORFs, except YDR455C, confer sensitivity to DNA damage agents. It remains unknown if the phenotypes associated with deletion of these dubious ORFs are due to a loss-of-function in the overlapping ORFs.

Loss of cohesion function in BUB1 and BUB3 confers NAM sensitivity

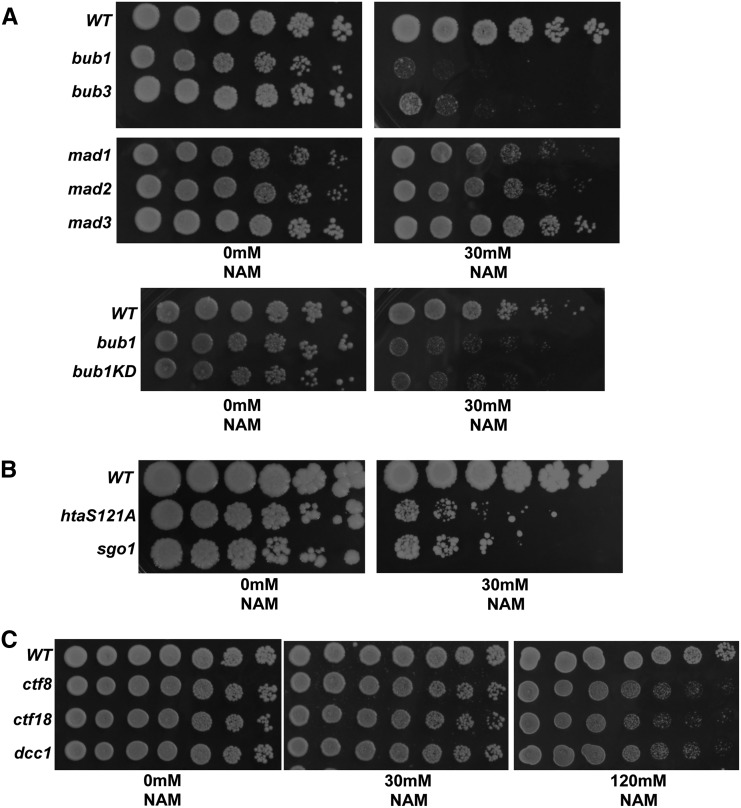

Our screen identified deletions in BUB1 and BUB3 as highly sensitive to NAM (Table 1). Bub1p and Bub3p form part of the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) complex that is crucial in sensing a lack of microtubule-kinetochore attachments (London and Biggins 2014). In addition, Bub1 is required for the assembly of centromeric cohesion (Hoyt et al. 1991; Kawashima et al. 2010; Fernius and Hardwick 2007). Importantly, both functions are conserved from yeast to humans (Lara-Gonzalez et al. 2012). Thus, we sought to determine if the sensitivity to NAM observed in deletions of BUB1 and BUB3 is related to SAC and/or cohesion function. In addition to Bub1p and Bub3p, Mad1p, Mad2p, and Mad3p are required for SAC function (Li and Murray 1991; Hardwick and Murray 1995; Hardwick et al. 2000). If the defects conferred by NAM treatment required an intact SAC, we predicted that deletions in the MAD genes would also confer a similar sensitivity. Deletions in MAD1, 2, and 3 were present in the library of deletions that we screened; however, these strains were not sensitive to NAM (Table S2 and Table S3). To rule out the possibility that these were false negatives, we performed growth assays using deletions in MAD1, MAD2, and MAD3 (Figure 5A). Unlike bub1Δ and bub3Δ, which displayed sensitivity to NAM, mad1Δ, mad2Δ, and mad3Δ strains did not exhibit growth defects on NAM medium (Figure 5A and Figure S1). Therefore, the sensitivity of bub1∆ and bub3∆ to NAM may not be due to their role in SAC.

Figure 5.

Growth assays show that mutants in the Bub1-Sgo1-H2A cohesion pathway render cells sensitive to NAM. (A) Deletion in BUB1, BUB3, and BUB1 with its kinase domain deleted (bub1KD) all confer sensitivity to 30 mM nicotinamide (NAM). In contrast, deletions in MAD1, MAD2, or MAD3 lead to little to no sensitivity to NAM. Loss of Bub1 kinase activity phenocopies the sensitivity displayed in BUB1 deletion mutants to NAM. (B) The nonphosphorylatable H2A (htaS121A) mutant and deletion in SGO1 both show similar sensitivity to NAM. (C) Deletions in subunits of the alternative replication complex leads to sensitivity to 120 mM NAM. Overnight cultures of each strain were serially diluted fivefold and 3 μl were spotted and incubated at 30°C. WT, wild-type.

Bub1p in budding yeast, fission yeast, and humans is required for centromeric localization of Sgo1p, which is important for assembly of centromeric cohesion (Kawashima et al. 2010). In budding yeast, Bub1p phosphorylates H2A on serine 121 and this mediates recruitment of Sgo1p to the centromere. Thus, we sought to determine if loss of Bub1p kinase activity alone would cause NAM sensitivity. Indeed, we found that the kinase-deficient bub1KD mutant also showed growth sensitivity on NAM medium (Figure 5B). To test if NAM sensitivity was related to Bub1p’s function in cohesion, we tested deletions in SGO1 and the nonphosphorylatable H2A mutant for sensitivity to NAM. Consistent with NAM having an effect on centromeric cohesion, we found that both sgo1Δ and the htaS121A strains were as sensitive to NAM as bub1Δ (Figure 5B). Taken together, these results suggest that the sensitivity of bub1∆ and bub3∆ to NAM is due to their role in cohesion and not to a defect in the SAC.

Cohesin mutants are sensitive to NAM

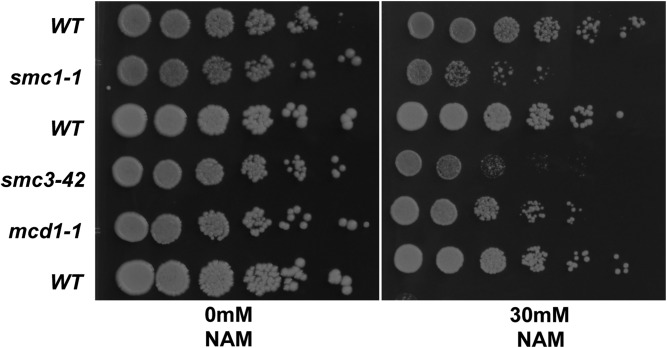

The sensitivity of bub1Δ, sgo1Δ, and htaS121A mutants suggests that defects in cohesion renders cells sensitive to NAM. In addition to bub1Δ and bub3Δ, deletions in all three subunits of the topoisomerase III complex (TOP3, RMI1, SGS1) were identified as highly sensitive (Figure 2 and Table 1). Notably, the Top3p complex plays an important role not only in resolving recombination intermediates and telomere stability, but also in cohesion assembly (Lai et al. 2007). Our primary screen also revealed that several subunits that comprise the alternative replication machinery, which functions in cohesion assembly, scored slightly higher than our 0.5 cut-off for sensitive mutants (Mayer et al. 2001)(Table S2 and Table S3). Hence, we tested a subset of mutants in the alternative replication complex and determined that deletions in ctf8, ctf18, and dcc1 showed mild sensitivity to growth on plates containing 120 mM NAM (Figure 5C). The very mild NAM sensitivity of these strains may be due to redundancy in these pathways/genes. Together, these results support our conclusion that cohesion mutants are sensitive to NAM. To further explore the effect of NAM on cohesion, we examined NAM sensitivity of conditional alleles for essential cohesin genes (SMC1, SMC3 and MCD1) that were not present in our genome-wide screen (Guacci et al. 1997; Michaelis et al. 1997). Consistent with cohesion defects leading to sensitivity to NAM, we found that smc1-1 and smc3-2 strains were highly sensitive to NAM and that the mcd1-1 strain was mildly sensitive to NAM (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Growth assays reveal that conditional mutants in the essential cohesion complex subunits are sensitive to NAM. Strains with temperature sensitive mutations in the core cohesin genes (smc1-1, smc3-42, and mcd1-1) display sensitivity to nicotinamide (NAM) at permissive temperature. Overnight cultures of each strain were serially diluted fivefold and 3 μl were spotted and incubated at 30°C.

The deacetylation reactions carried out by the sirtuins (Sir2p, Hst1p-4p) consume NAD+ yielding NAM and 2′O-acetyl ADP-ribose. NAM can be used in the “NAD+ salvage” pathway, first by conversion to NA by nicotinamidase (Pnc1p), followed by several enzymatic steps to yield more NAD+ (Bogan and Brenner 2008; Wierman and Smith 2014). Therefore, another possible explanation for the observed effects of NAM might be through the increased production of NA or potentially by increasing the levels of NAD+. We performed growth assays for several deletion and temperature sensitive mutants that affect cohesion in the presence or absence of 30 mM NA. As shown in (Figure 7) we observed no growth effects for any mutants tested on NA. These results support our conclusion that the effect of NAM is likely through its activity as an inhibitor of the sirtuins and perhaps an unknown activity of NAM that is independent of NAD+ biosynthesis.

Figure 7.

Growth assays of yeast carrying mutations in genes with defects in cohesion reveal an absence of sensitivity to nicotinic acid (NA). Each mutant tested here displays marked sensitivity to nicotinamide (NAM) but they are not sensitive to NA. Overnight cultures of each strain were serially diluted fivefold and 3 μl were spotted and incubated at 30°C.

Summary

The results of our genome-wide screen show that genome stability pathways are particularly vulnerable to loss of sirtuin activity. A chemical-genomics approach using NAM, a pan-sirtuin inhibitor, provided novel insights into sirtuin-dependent activities in the cell, as demonstrated by the majority of genes we identified not previously being reported to have genetic interactions with sirtuin deletions. Importantly, GeneMANIA analysis of the 55 mutants revealed networks of genetic and physical interactions that have important functions in responding to and repairing DNA lesions. We also identified genes required for Golgi, vacuolar, and ribosome function, suggesting that sirtuin activity is indispensable for these processes. Gene deletions in these processes, which are not typically thought to be part of the DDR pathway, nonetheless have activities that relate to DDR directly or indirectly. For example, deletions in several Golgi genes (YPT6, COG8, VPS53) have negative interactions with DNA repair and recombination mutants. Many of the same genes that are important for DNA damage have been reported to have roles in cohesion assembly/maintenance (e.g., TOP3, HTZ1). In turn, we showed that yeast deleted in BUB1, BUB3, SGO1, or carrying the H2A mutant that is nonphosphorylatable by Bub1 are all highly sensitive to NAM. In contrast, deletions in MAD1, MAD2, or MAD3 did not result in NAM sensitivity. Taken together, these results indicate that the role of BUB1 and BUB3 in cohesion contributes to their sensitivity to NAM. In addition, mutants in genes that encode the essential cohesins are also sensitive to NAM, further showing that sirtuin activity is required when chromosome cohesion is compromised. Cohesion is known to have an important role in DNA damage repair and can form postreplicatively in response to DNA damage, supporting the role of sirtuins in protecting the genome. Moreover, this work confirms previous studies using NAM and deletions in the HST3 and HST4 sirtuins, which revealed important roles for HST3- and HST4-mediated H3K56 deacetylation in suppressing spontaneous DNA damage and establishing sister chromatid cohesion during S-phase (Maas et al. 2006; Celic et al. 2006, 2006; Thaminy et al. 2007). Our genome-wide screen for NAM sensitive mutants reveals biological pathways that are dependent on sirtuin activity, provides insights into the range of processes sirtuin activity impacts, and may aid in the identification of therapeutic targets for sirtuin-related diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Charlie Boone for generously providing the nonessential yeast deletion collection, Kevin Hardwick, Douglas Koshland, and Satoshi Kawashima for yeast strains, the Choy and Basrai laboratory members for discussions, and Jack Warren for proofreading of the manuscript. The Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, supports work in M.A.B.’s laboratory. J.S.C. gratefully acknowledges the Litovitz Family Fund for generously supporting work in his laboratory.

Footnotes

Supporting information is available online at www.g3journal.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/g3.115.022244/-/DC1

Communicating editor: C. Boone

Literature Cited

- Abeliovich H., Grote E., Novick P., Ferro-Novick S., 1998. Tlg2p, a yeast syntaxin homolog that resides on the Golgi and endocytic structures. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 11719–11727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R. M., Bitterman K. J., Wood J. G., Medvedik O., Sinclair D. A., 2003. Nicotinamide and PNC1 govern lifespan extension by calorie restriction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 423: 181–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio O. M., Billington B. L., Gottschling D. E., 1991. Modifiers of position effect are shared between telomeric and silent mating-type loci in S. cerevisiae. Cell 66: 1279–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auger A., Galarneau L., Altaf M., Nourani A., Doyon Y., et al. , 2008. Eaf1 is the platform for NuA4 molecular assembly that evolutionarily links chromatin acetylation to ATP-dependent exchange of histone H2A variants. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28: 2257–2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avalos J. L., Bever K. M., Wolberger C., 2005. Mechanism of sirtuin inhibition by nicotinamide: altering the NAD(+) cosubstrate specificity of a Sir2 enzyme. Mol. Cell 17: 855–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan R., Park J., Karra K., Hitz B. C., Binkley G., et al. , 2012. YeastMine–an integrated data warehouse for Saccharomyces cerevisiae data as a multipurpose tool-kit. Database (Oxford) 2012: bar062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilsland E., Hult M., Bell S. D., Sunnerhagen P., Downs J. A., 2007. The Bre5/Ubp3 ubiquitin protease complex from budding yeast contributes to the cellular response to DNA damage. DNA Repair (Amst.) 6: 1471–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitterman K. J., Anderson R. M., Cohen H. Y., Latorre-Esteves M., Sinclair D. A., 2002. Inhibition of silencing and accelerated aging by nicotinamide, a putative negative regulator of yeast sir2 and human SIRT1. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 45099–45107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blander G., Guarente L., 2004. The Sir2 family of protein deacetylases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73: 417–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogan K. L., Brenner C., 2008. Nicotinic acid, nicotinamide, and nicotinamide riboside: a molecular evaluation of NAD+ precursor vitamins in human nutrition. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 28: 115–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle E. I., Weng S., Gollub J., Jin H., Botstein D., et al. , 2004. GO:TermFinder–open source software for accessing Gene Ontology information and finding significantly enriched Gene Ontology terms associated with a list of genes. Bioinformatics 20: 3710–3715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan G. T., 1986. The influence of niacin and nicotinamide on in vivo carcinogenesis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 206: 331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celic I., Masumoto H., Griffith W. P., Meluh P., Cotter R. J., et al. , 2006. The sirtuins hst3 and Hst4p preserve genome integrity by controlling histone h3 lysine 56 deacetylation. Curr. Biol. 16: 1280–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celic I., Verreault A., Boeke J. D., 2008. Histone H3 K56 hyperacetylation perturbs replisomes and causes DNA damage. Genetics 179: 1769–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy J. S., Acuna R., Au W. C., Basrai M. A., 2011. A role for histone H4K16 hypoacetylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae kinetochore function. Genetics 189: 11–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M., Stutz F., Dargemont C., 2003. Deubiquitination, a new player in Golgi to endoplasmic reticulum retrograde transport. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 51989–51992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conibear E., Cleck J. N., Stevens T. H., 2003. Vps51p mediates the association of the GARP (Vps52/53/54) complex with the late Golgi t-SNARE Tlg1p. Mol. Biol. Cell 14: 1610–1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo M. C., Engel S. R., Wong E. D., Lloyd P., Karra K., et al. , 2014. Saccharomyces genome database provides new regulation data. Nucleic Acids Res. 42: D717–D725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle S. M., Gilbert W. V., Doudna J. A., 2009. Direct link between RACK1 function and localization at the ribosome in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29: 1626–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekena K., Vater C. A., Raymond C. K., Stevens T. H., 1993. The VPS1 protein is a dynamin-like GTPase required for sorting proteins to the yeast vacuole. Ciba Found. Symp. 176: 198–211, discussion 211–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernius J., Hardwick K. G., 2007. Bub1 kinase targets Sgo1 to ensure efficient chromosome biorientation in budding yeast mitosis. PLoS Genet. 3: e213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo C. M., Smith D. L., Jr, Smith J. S., 2004. Nicotinamide clearance by Pnc1 directly regulates Sir2-mediated silencing and longevity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24: 1301–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong B., Pan Y., Vempati P., Zhao W., Knable L., et al. , 2013. Nicotinamide riboside restores cognition through an upregulation of proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1alpha regulated beta-secretase 1 degradation and mitochondrial gene expression in Alzheimer’s mouse models. Neurobiol. Aging 34: 1581–1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh H., Nomura T., Nakajima H., Hasegawa C., Sakamoto Y., 1988. Inhibiting effects of nicotinamide on urethane-induced malformations and tumors in mice. Mutat. Res. 199: 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guacci V., Koshland D., Strunnikov A., 1997. A direct link between sister chromatid cohesion and chromosome condensation revealed through the analysis of MCD1 in S. cerevisiae. Cell 91: 47–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemain G., Ma E., Mauger S., Miron S., Thai R., et al. , 2007. Mechanisms of checkpoint kinase Rad53 inactivation after a double-strand break in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27: 3378–3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta K. P., 1999. Effects of nicotinamide on mouse skin tumor development and its mode of action. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 12: 177–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie C., Fink G. R., 1991. Guide to Yeast Genetics and Molecular Biology. Methods Enzymol. 194: 3–933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachinohe M., Hanaoka F., Masumoto H., 2011. Hst3 and Hst4 histone deacetylases regulate replicative lifespan by preventing genome instability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Cells 16: 467–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwick K. G., Murray A. W., 1995. Mad1p, a phosphoprotein component of the spindle assembly checkpoint in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 131: 709–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwick K. G., Johnston R. C., Smith D. L., Murray A. W., 2000. MAD3 encodes a novel component of the spindle checkpoint which interacts with Bub3p, Cdc20p, and Mad2p. J. Cell Biol. 148: 871–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema E. H., Lewis M. J., Black M. W., Pelham H. R., 2003. Retromer and the sorting nexins Snx4/41/42 mediate distinct retrieval pathways from yeast endosomes. EMBO J. 22: 548–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes S. G., Rose A. B., Steuerle K., Saez E., Sayegh S., et al. , 1997. Hyperactivation of the silencing proteins, Sir2p and Sir3p, causes chromosome loss. Genetics 145: 605–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt M. A., Totis L., Roberts B. T., 1991. S. cerevisiae genes required for cell cycle arrest in response to loss of microtubule function. Cell 66: 507–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivy J. M., Klar A. J., Hicks J. B., 1986. Cloning and characterization of four SIR genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6: 688–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M., Lin S. J., 2014. Regulation of NAD+ metabolism, signaling and compartmentalization in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. DNA Repair (Amst.) 23: 49–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima S. A., Yamagishi Y., Honda T., Ishiguro K., Watanabe Y., 2010. Phosphorylation of H2A by Bub1 prevents chromosomal instability through localizing shugoshin. Science 327: 172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogan N. J., Baetz K., Keogh M. C., Datta N., Sawa C., et al. , 2004. Regulation of chromosome stability by the histone H2A variant Htz1, the Swr1 chromatin remodeling complex, and the histone acetyltransferase NuA4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 13513–13518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudlyk T., Willett R., Pokrovskaya I. D., Lupashin V., 2013. COG6 interacts with a subset of the Golgi SNAREs and is important for the Golgi complex integrity. Traffic 14: 194–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M. S., Seki M., Ui A., Enomoto T., 2007. Rmi1, a member of the Sgs1-Top3 complex in budding yeast, contributes to sister chromatid cohesion. EMBO Rep. 8: 685–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Gonzalez P., Westhorpe F. G., Taylor S. S., 2012. The spindle assembly checkpoint. Curr. Biol. 22: R966–R980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. E., Frenz L. M., Wells N. J., Johnson A. L., Johnston L. H., 2001. Order of function of the budding-yeast mitotic exit-network proteins Tem1, Cdc15, Mob1, Dbf2, and Cdc5. Curr. Biol. 11: 784–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Murray A. W., 1991. Feedback control of mitosis in budding yeast. Cell 66: 519–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S. J., Defossez P. A., Guarente L., 2000. Requirement of NAD and SIR2 for life-span extension by calorie restriction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science 289: 2126–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Larsson L., Caballero A., Hao X., Oling D., et al. , 2010. The polarisome is required for segregation and retrograde transport of protein aggregates. Cell 140: 257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Pitta M., Jiang H., Lee J. H., Zhang G., et al. , 2013. Nicotinamide forestalls pathology and cognitive decline in Alzheimer mice: evidence for improved neuronal bioenergetics and autophagy procession. Neurobiol. Aging 34: 1564–1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh E., Hong W., 2004. The binary interacting network of the conserved oligomeric Golgi tethering complex. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 24640–24648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London N., Biggins S., 2014. Signalling dynamics in the spindle checkpoint response. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15: 736–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z., Gallwitz D., 2003. Biochemical and genetic evidence for the involvement of yeast Ypt6-GTPase in protein retrieval to different Golgi compartments. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 791–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas N. L., Miller K. M., Defazio L. G., Toczyski D. P., 2006. Cell cycle and checkpoint regulation of histone H3 K56 acetylation by Hst3 and Hst4. Mol. Cell 23: 109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Yken H., Dagkessamanskaia A., Basmaji F., Lagorce A., Francois J., 2003. The interaction of Slt2 MAP kinase with Knr4 is necessary for signalling through the cell wall integrity pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 49: 23–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M. L., Gygi S. P., Aebersold R., Hieter P., 2001. Identification of RFC(Ctf18p, Ctf8p, Dcc1p): an alternative RFC complex required for sister chromatid cohesion in S. cerevisiae. Mol. Cell 7: 959–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNew J. A., Coe J. G., Sogaard M., Zemelman B. V., Wimmer C., et al. , 1998. Gos1p, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae SNARE protein involved in Golgi transport. FEBS Lett. 435: 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis C., Ciosk R., Nasmyth K., 1997. Cohesins: chromosomal proteins that prevent premature separation of sister chromatids. Cell 91: 35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuguchi G., Shen X., Landry J., Wu W. H., Sen S., et al. , 2004. ATP-driven exchange of histone H2AZ variant catalyzed by SWR1 chromatin remodeling complex. Science 303: 343–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasmyth K. A., 1982. The regulation of yeast mating-type chromatin structure by SIR: an action at a distance affecting both transcription and transposition. Cell 30: 567–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillus L., Rine J., 1989. Epigenetic inheritance of transcriptional states in S. cerevisiae. Cell 59: 637–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rine J., Herskowitz I., 1987. Four genes responsible for a position effect on expression from HML and HMR in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 116: 9–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T. K., Darsow T., Emr S. D., 1998. Vam7p, a SNAP-25-like molecule, and Vam3p, a syntaxin homolog, function together in yeast vacuolar protein trafficking. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18: 5308–5319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore D., Squire M., Nasmyth K. A., 1984. Characterization of two genes required for the position-effect control of yeast mating-type genes. EMBO J. 3: 2817–2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siniossoglou S., Peak-Chew S. Y., Pelham H. R., 2000. Ric1p and Rgp1p form a complex that catalyses nucleotide exchange on Ypt6p. EMBO J. 19: 4885–4894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrzypek, M. S., and J. Hirschman, 2011 Using the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD) for analysis of genomic information. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 35:1.20.1–1.20.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. S., Avalos J., Celic I., Muhammad S., Wolberger C., et al. , 2002. SIR2 family of NAD(+)-dependent protein deacetylases. Methods Enzymol. 353: 282–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaminy S., Newcomb B., Kim J., Gatbonton T., Foss E., et al. , 2007. Hst3 is regulated by Mec1-dependent proteolysis and controls the S phase checkpoint and sister chromatid cohesion by deacetylating histone H3 at lysine 56. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 37805–37814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissenbaum H. A., Guarente L., 2001. Increased dosage of a sir-2 gene extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 410: 227–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tkach J. M., Yimit A., Lee A. Y., Riffle M., Costanzo M., et al. , 2012. Dissecting DNA damage response pathways by analysing protein localization and abundance changes during DNA replication stress. Nat. Cell Biol. 14: 966–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi K., Matmati N., Zzaman S., Westwater C., Mohanty B. K., 2012. Nicotinamide induces Fob1-dependent plasmid integration into chromosome XII in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 12: 949–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van C., Williams J. S., Kunkel T. A., Peterson C. L., 2015. Deposition of histone H2A.Z by the SWR-C remodeling enzyme prevents genome instability. DNA Repair (Amst.) 25: 9–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagih O., Usaj M., Baryshnikova A., Vandersluis B., Kuzmin E., et al. , 2013. SGAtools: one-stop analysis and visualization of array-based genetic interaction screens. Nucleic Acids Res. 41: W591–W596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierman M. B., Smith J. S., 2014. Yeast sirtuins and the regulation of aging. FEMS Yeast Res. 14: 73–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yiasemides E., Sivapirabu G., Halliday G. M., Park J., Damian D. L., 2009. Oral nicotinamide protects against ultraviolet radiation-induced immunosuppression in humans. Carcinogenesis 30: 101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller C. E., Parnell S. C., Dohlman H. G., 2007. The RACK1 ortholog Asc1 functions as a G-protein beta subunit coupled to glucose responsiveness in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 25168–25176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Roberts D. N., Cairns B. R., 2005. Genome-wide dynamics of Htz1, a histone H2A variant that poises repressed/basal promoters for activation through histone loss. Cell 123: 219–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. G., Zhao G., Qin Q., Wang B., Liu L., et al. , 2013. Nicotinamide prohibits proliferation and enhances chemosensitivity of pancreatic cancer cells through deregulating SIRT1 and Ras/Akt pathways. Pancreatology 13: 140–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao K., Harshaw R., Chai X., Marmorstein R., 2004. Structural basis for nicotinamide cleavage and ADP-ribose transfer by NAD(+)-dependent Sir2 histone/protein deacetylases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 8563–8568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X. F., Prakash R., Saro D., Longerich S., Niu H., et al. , 2011. Processing of DNA structures via DNA unwinding and branch migration by the S. cerevisiae Mph1 protein. DNA Repair (Amst.) 10: 1034–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuberi K., Franz M., Rodriguez H., Montojo J., Lopes C. T., et al. , 2013. GeneMANIA prediction server 2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 41: W115–W122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.