ABSTRACT

Deacetylation of 7-aminocephalosporanic acid (7-ACA) at position C-3 provides valuable starting material for producing semisynthetic β-lactam antibiotics. However, few enzymes have been characterized in this process before now. Comparative analysis of the genome of the thermophilic bacterium Alicyclobacillus tengchongensis revealed a hypothetical protein (EstD1) with typical esterase features. The EstD1 protein was functionally cloned, expressed, and purified from Escherichia coli BL21(DE3). It indeed displayed esterase activity, with optimal activity at around 65°C and pH 8.5, with a preference for esters with short-chain acyl esters (C2 to C4). Sequence alignment revealed that EstD1 is an SGNH hydrolase with the putative catalytic triad Ser15, Asp191, and His194, which belongs to carbohydrate esterase family 12. EstD1 can hydrolyze acetate at the C-3 position of 7-aminocephalosporanic acid (7-ACA) to form deacetyl-7-ACA, which is an important starting material for producing semisynthetic β-lactam antibiotics. EstD1 retained more than 50% of its initial activity when incubated at pH values ranging from 4 to 11 at 65°C for 1 h. To the best of our knowledge, this enzyme is a new SGNH hydrolase identified from thermophiles that is able to hydrolyze 7-ACA.

IMPORTANCE Deacetyl cephalosporins are highly valuable building blocks for the industrial production of various kinds of semisynthetic β-lactam antibiotics. These compounds are derived mainly from 7-ACA, which is obtained by chemical or enzymatic processes from cephalosporin C. Enzymatic transformation of 7-ACA is the main method because of the adverse effects chemical deacylation brought to the environment. SGNH hydrolases are widely distributed in plants. However, the tools for identifying and characterizing SGNH hydrolases from bacteria, especially from thermophiles, are rather limited. Here, our work demonstrates that EstD1 belongs to the SGNH family and can hydrolyze acetate at the C-3 position of 7-ACA. Moreover, this study can enrich our understanding of the functions of these enzymes from this family.

INTRODUCTION

Deacetyl cephalosporins are highly valuable building blocks for the industrial production of various kinds of semisynthetic β-lactam antibiotics. These compounds are derived mainly from 7-aminocephalosporanic acid (7-ACA), which is obtained from cephalosporin C by chemical or enzymatic processes (1). Environmentally friendly enzymatic processes are widely used because of the advantages of mild reaction conditions, such as pH, temperature, and high yield. In many cases, chemical modifications can be made at the C-3′ position of 7-ACA by nucleophilic displacement of the acetate group; the removal of the acetate group is necessary to make other modifications at this position. The enzyme cephalosporin C deacetylase (CCD; also called acetylesterase) catalyzes the hydrolysis of acetate from the 3′ position of 7-ACA. These enzyme activities have been found in citrus peels (2) and mammalian tissues, where it appears to be most prevalent in the liver and kidney (3).

Presently, esterases and deacetylases that are active on carbohydrate substrates have been classified into 16 families by Cantarel and coworkers (Carbohydrate-Active enZymes Server [CAZy]; http://www.cazy.org) (4). According to this classification, 7-ACA deacetylases or acetylesterases can be classified into carbohydrate esterase family 7 and 12 (CE-7 and CE-12), respectively. Thus far, only 9 sequences have been characterized among the 526 sequences submitted for classification in the CE-7 family. Among these characterized proteins, only 6 have been demonstrated to have 7-ACA deacetylase activity, including acetyl xylan esterase (AXE) from Bacillus subtilis CICC 20034 (5), CAH from B. subtilis SHS 0133 (6), Axe from Bacillus pumilus PS213 (7), Cah from B. subtilis subsp. subtilis strain 168 (8), Axe1 from Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum JW/SL-YS485 (9), and TM0077 from Thermotoga maritima MSB8 (10, 11). In the CE-12 family, only 11 sequences have been characterized among the 570 sequences submitted. Thus far, only BH1115 from Bacillus halodurans C-125 (12), a CCD from Bacillus sp. strain KCCM10143 (13), and YesT from B. subtilis subsp. subtilis strain 168 (14) have been demonstrated to have 7-ACA deacetylase activity among these characterized proteins. Thus, the importance of the CE-7 and CE-12 family lies in, for instance, the industrial application of some of their members for the production of semisynthetic β-lactam antibiotics. Moreover, sequence alignment reveals that BH1115 from Bacillus halodurans C-125 and CCD from Bacillus sp. strain KCCM10143 also belong to the SGNH hydrolase family, which has unique structural features (15). However, this family is not well known, and only a few members have been characterized. CCD has been used for the industrial transformation of 7-ACA into the corresponding 3-deacetyl compound, which is an advanced intermediate in the production of semisynthetic β-lactam antibiotics (13). To date, little information about the characterization of the SGNH hydrolase superfamily from microorganisms has been obtained (16, 17). Furthermore, besides BH1115 and CCD, no member of the SGNH hydrolase family has been shown to be involved in the deacetylation of 7-ACA. Alicyclobacillus tengchongensis is a Gram-positive thermophilic bacterium that can grow well at temperatures higher than 50°C (18). However, there currently are no reports about the identification or characterization of enzymes involved in the deacetylation of 7-ACA from this genus.

In this study, we present the identification and characterization of a new deacetylase, EstD1, from A. tengchongensis. Sequence structural features and enzyme activity over a broad range of pHs distinguish EstD1 from other previously reported deacetylases. Site-directed mutagenesis was employed to study the catalytic triad of EstD1. In addition, the deacetylase activity of EstD1 toward 7-ACA also was studied.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and materials.

7-Aminocephalosporanic acid (7-ACA; 98% purity) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The substrates p-nitrophenol (p-NP) acetate (p-NPC2), p-NP butyrate (p-NPC4), p-NP caproate (p-NPC6), p-NP caprylate (p-NPC8), p-NP caprate (p-NPC10), p-NP laurate (p-NPC12), p-NP myristate (p-NPC14), p-NP palmitate (p-NPC16), and α- and β-naphthyl acetate were from Sigma-Aldrich or TCI (Tokyo, Japan). The acetic acid detection kit (K-ACET) was from Megazyme (Dublin, Ireland). Nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA)-agarose was purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). Fast PFU DNA polymerase, the pEASY-E2 expression kit, and the fast mutagenesis system were provided by TransGen Biotech (Beijing, China). All other regents and solvents used in this study were of analytical grade and commercially available. A. tengchongensis was isolated from a hot spring in Tengchong, Yunnan, China, and cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 50°C.

Genome sequencing and sequence analysis.

Genomic DNA of the A. tengchongensis strain was extracted using a genomic DNA isolation kit (TianGen, Beijing, China) from cells grown overnight at 50°C. Genomic sequencing was performed by the Beijing Genomics Institute (Guangzhou, China) using a Solexa Genome Analyzer, and a partial genomic sequence was obtained. Oligonucleotide primers were synthesized by Shanghai Sangon Biological Engineering Technology and Services Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The full-length esterase gene estD1 was revealed based on the prediction of open reading frames (ORFs) from the partial genomic sequence by using the GeneMark.hmm online tool (http://exon.gatech.edu/GeneMark/gmhmmp.cgi). CAZy (http://www.cazy.org) and dbCAN (http://csbl.bmb.uga.edu/dbCAN/index.php) were used for the classification of EstD1. Putative functions were inferred using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST). Protein similarity searches and alignment were performed using the data from CLUSTAL W alignments (19). The signal sequence for peptide cleavage of EstD1 was predicted using SignalP 4.0 (20). The Pfam database (version 27.0; available at http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/) was used to search for conserved domains in the predicted amino acid sequences. ESPript output was used to render the analysis of multiple-sequence alignments (21). The neighbor-joining method in the molecular evolutionary genetic analysis (MEGA) software package, version 6.0 (http://www.megasoftware.net/), was used to construct a phylogenetic tree. The theoretical molecular mass of the deduced EstD1 protein sequence was calculated using the Compute pI/Mw tool on the ExPASy proteomics server (available at http://expasy.org/tools/pi_tool.html).

Expression and purification of heterologously expressed His6-EstD1.

The estD1 gene was amplified by Fast PFU DNA polymerase from the genomic DNA of A. tengchongensis using primers EstD1-F (5′-CGCTTAGAAGCAAACAGCAAAC-3′) and EstD1-R (5′-GCATTGCGAGCCAATTTCGC-3′). Direct ligations of PCR products to the pEASY-E2 expression vector were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The ligation mix then was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells (EMD Biosciences, Madison, WI) for heterologous expression. Recombinant E. coli strains were grown at 37°C in LB medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin. The culture was induced by adding 0.7 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside until reaching an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6, and then the culture was grown at 20°C for 10 h. E. coli cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 20 mM citrate-phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Cells were disrupted by ultrasonication (7 s, 150 W) on ice with a Scientz-IID sonicator (Ningbo Scientz Biotechnology, Ningbo, China), and His6-EstD1 was purified using a column of Ni-NTA-agarose (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The success of the purification was examined using SDS-PAGE. The protein within the SDS-PAGE gel was identified using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) performed by Boyuan (Shanghai, China). The protein concentration was estimated using the Bradford procedure, employing bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard (Sigma-Aldrich) (22). Purified His-EstD1 was stored at −70°C for further study.

Enzyme assays.

Esterase activity was measured using p-NP esters as described previously (23), with some changes. Briefly, the standard assay consisted of activity measurements with 0.6 mM p-NPC2 as the substrate in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.5) at 65°C. The amount of p-NP liberated was measured continuously at 405 nm on a Specord 200 Plus (Analytic, Jena, Germany) with a temperature-controlled cuvette holder. The calibration curve was prepared using p-nitrophenol as a standard. One unit of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to release 1 μM p-NP from the substrate per minute. Kinetic parameters were determined by direct fitting of the data, obtained from multiple measurements, to the Michaelis-Menten curve. Substrate concentrations ranged from 0.1 to 1.1 mM (0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1.0, and 1.1 mM).

The effect of pH on esterase activity was studied in the pH range of 5.0 to 12.0. The buffers used were 50 mM citrate-phosphate buffer (pH 5.0 to 8.0), 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0 to 9.0), and 50 mM sodium carbonate-sodium bicarbonate (pH 9.0 to 12.0). The same buffers were used to test the pH stability of EstD1. The effect of temperature on esterase activity was studied in the range of 20 to 90°C, using 0.6 mM p-NPC2 as the substrate. Enzyme thermostability was determined by incubating the enzyme at 37, 50, and 65°C for various time intervals. Residual activity was determined in the standard assay.

Deacetylase activity was determined using the K-ACET acetic acid kit by measuring the amount of acetic acid released from the substrate, 7-ACA. Megazyme Mega-Calc was used for calculating the concentration of acetic acid from the raw absorbance data according to the manufacturer's instructions. The reaction mixture contained 0.1 ml of enzyme solution and 0.3 ml of substrate solution (dissolved in 50 mM Na2HPO4-KH2PO4 buffer, pH 7.3) and was incubated at 25°C for 10 min. The sample blank contained no enzyme in the reaction mixture. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that released 1 μmol of acetic acid per min.

The effect of different potential inhibitors or activators (metal ions, chemical agents, and organic solvents) were studied by preincubating EstD1 with various inhibitors or activators in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) at 65°C for 5 min. Samples subsequently were placed on ice, and residual activity was measured using the standard assay. The activity of the enzyme without inhibitor or activator was defined as 100%.

Analytical methods.

For the mass spectrum analysis, 100 μl (0.22 μg) of purified EstD1 was added to 0.07 mol/liter Na2HPO4-KH2PO4 buffer (pH 7.3), which contained 16.5 mM (4.5 g/liter) 7-ACA, and the total volume was 400 μl. After incubation for 10 min at 25°C, the product of 7-ACA hydrolyzed by EstD1 was detected by injecting 100 μl of the reaction mixture into a Waters Acquity-Xevo TQ system (Waters, Milford, MA) using positive and negative electrospray ionization (ESI) and the following conditions: capillary voltage of 2.0 kV, cone of −30.0 V and 30 V, source temperature of 150°C, desolvation temperature of 200°C, desolvation gas flow of 400 liters/h, and cone gas flow of 150 liters/h. Daughter-ion scans were used to monitor the analytes.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using a Fast mutagenesis system kit (TransGen Biotech) with the following primers (modified codons are underlined): 5′-TGATTGGCGACGCCATCACTGAC-3′ and 5′-GGCGTCGCCAATCATCACGAG-3′ for the S15A mutant, 5′-GAGCTGGTCTGGCGCTCGCGTCCAT-3′ and 5′-AGCGCCAGACCAGCTCCATGTGTT-3′ for the D191A mutant, 5′-TCTGGCGATCGCGTCGCTCCATACATC-3′ and 5′-AGCGACGCGATCGCCAGACCAGCTCCA-3′ for the H194A mutant, and 5′-GGAGATGTTCTTGTTAGCCCCATTTTTCCT-3′ and 5′-GGCTAACAAGAACATCTCCTTAACGCGCG-3′ for the S135A mutant. DNA manipulations were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. All mutation sites were confirmed by DNA sequencing. For expression, plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells.

Structure prediction and 7-ACA docking.

The structure of EstD1 was built using SWISS-MODEL based on the crystal structure from PDB entry 3RJT for the GDSL lipolytic protein from A. acidocaldarius subsp. acidocaldarius DSM 446, with 66% identity to and 75% positivity for the query sequence (24). Docking was performed using AutoDock Vina (25), and the modeled D-1 structure and the ligand 7-ACA were prepared using AutoDockTools (26). Polar hydrogen atoms and partial charges were added to both target protein and ligand. In the grid preparation, we restricted our docking poses to a grid that was 20 Å by 20 Å by 20 Å and centered on all-atom centers of three active-site residues (Ser15, Asp191, and His194). Default values were used for the grid spacing and other docking parameters.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of the 16S rRNA and estD1 were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers DQ351931 and KM975483, respectively. The genomic sequence of A. tengchongensis has been deposited in the NCBI database under the accession number JXBW00000000.

RESULTS

Sequence analysis of the enzyme EstD1.

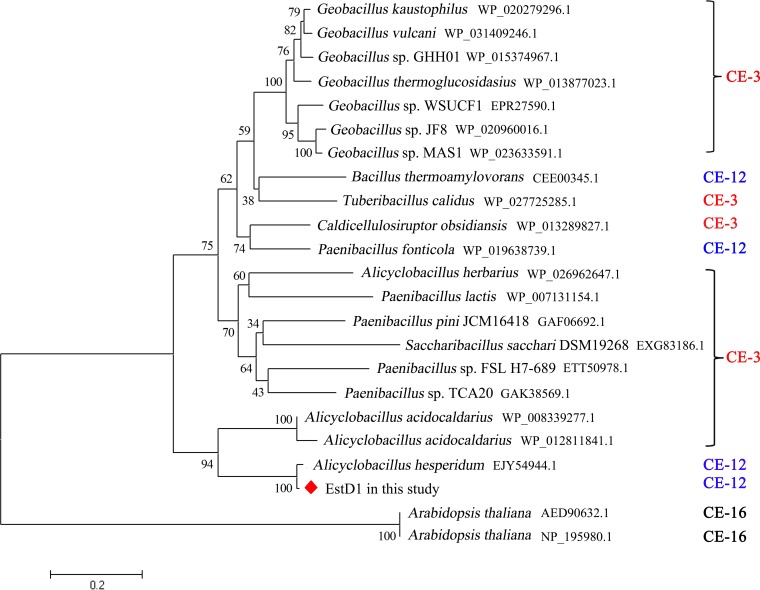

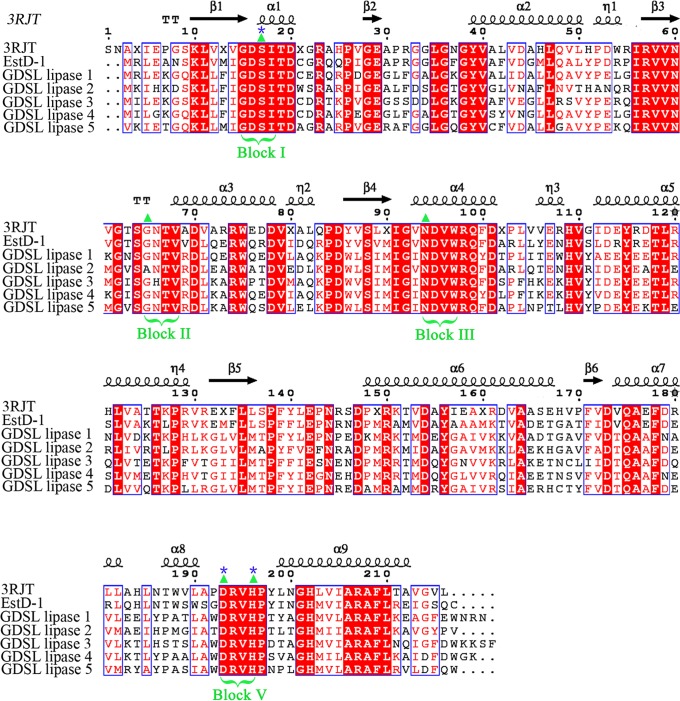

A thermophilic Alicyclobacillus tengchongensis strain growing in the range of 20 to 75°C (with the optimal temperature range being 45 to 50°C) was isolated from a hot spring in Tengchong, China. A. tengchongensis is a rod-shaped, spore-forming, Gram-positive bacterium. A comparison of the partial 16S rRNA sequence to those deposited in the GenBank database showed 99% nucleotide identities to Alicyclobacillus sacchari and Alicyclobacillus hesperidum strains (accession no. NR_041470.1 and AJ133632.1, respectively), indicating that they belong to the same genus. The A. tengchongensis strain has been deposited at the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC) as CGMCC1504. Comparative analysis of the genome of A. tengchongensis revealed a hypothetical protein (EstD1) with typical esterase features. Phylogenetic analysis showed that the GDSL lipases represented by EstD1 and the protein corresponding to NCBI accession no. EJY54944.1 form an independent clade (Fig. 1) and that they both belong to the CE-12 family. However, the protein corresponding to accession no. EJY54944.1 has not yet been characterized. Therefore, EstD1, the first characterized deacetylase in the Alicyclobacillus genus, is likely a new, distinct member of the SGNH superfamily. EstD1 consists of 215 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 25.3 kDa. Sequence analysis revealed that EstD1 has no predicted signal sequence using the SignalP 4.0 server and therefore is believed to be an intracellular enzyme. Comparison of the deduced amino acid sequence of EstD1 with those in the GenBank database showed that it had 66%, 58%, 57%, 54%, 54%, and 53% identity to the GDSL lipases from Alicyclobacillus acidocaldarius subsp. acidocaldarius DSM 446 (PDB entry 3RJT), (Paenibacillus fonticola (NCBI accession no. WP_019638739.1; GDSL lipase 1), Tuberibacillus calidus (WP_027725285.1; GDSL lipase 3), Pleomorphomonas oryzae (WP_026790528.1; GDSL lipase 2), Geobacillus kaustophilus (WP_020279296.1; GDSL lipase 4), and Chthonomonas calidirosea (WP_016481894.1; GDSL lipase 5), respectively (Fig. 2). Meanwhile, EstD1 shared 98% and 68% identity with the GDSL lipases from the genomic sequences of Alicyclobacillus hesperidum (WP_006447773.1) and A. acidocaldarius (WP_012811841.1), respectively, that have been deposited in GenBank. However, none of these proteins has been characterized, and there are no reports about their relevant function in the hydrolysis of 7-ACA.

FIG 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of EstD1. Protein sequences were aligned using the CLUSTAL W program (default parameters), and the EstD1 tree with the GDSL motif-containing lipase family was constructed using the neighbor-joining method. GenBank accession numbers or protein identifiers are shown at the end of each name. The lengths of the lines are proportional to the genetic distances between proteins. The scale bar represents the number of changes per nucleotide position, and the tree is unrooted. ⬥, EstD1 in the present study.

FIG 2.

Amino acid sequence alignment analysis of EstD1. Sequences retrieved from the NCBI server were aligned in CLUSTAL W and rendered using ESPript output. Sequences are grouped according to similarity. The protein corresponding to PDB entry 3RJT is from A. acidocaldarius subsp. acidocaldarius DSM 446; EstD1 is from A. tengchongensis, GDSL lipase 1 is from Paenibacillus fonticola (WP_019638739.1), GDSL lipase 2 is from Pleomorphomonas oryzae (WP_026790528.1), GDSL lipase 3 is from T. calidus (WP_027725285.1), GDSL lipase 4 is from G. kaustophilus (WP_020279296.1), and GDSL lipase 5 is from C. calidirosea (WP_016481894.1). Conserved motifs are highlighted. Residues strictly conserved among groups are shown in white font on a red background. Four conserved sequence blocks (blocks I to III and V; SGNH) found in all GDSL lipases are bracketed. Block I has the characteristic GDS sequence motif, block II has Gly as the only conserved residue in members of this family, and GXND is the consensus sequence in block III. Finally, block V has the DXXHP conserved sequence. Triangles represent the locations of the SGNH. The possible catalytic triads (serine [S], aspartic acid [D], and histidine [H]) are shown at the top of the alignment with asterisks. Symbols above blocks of sequences represent the secondary structure, springs represent helices, and arrows represent β-strands.

Cloning and purification of EstD1.

To investigate the biochemical properties of the enzyme, the estD1 gene was cloned from the genomic DNA of A. tengchongensis and expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3). As shown in Fig. S1 (lane 3) in the supplemental material, one band corresponding in size to the calculated molecular mass of EstD1 was detected (∼25.3 kDa). The band was absent from the control lane for E. coli BL21(DE3) cells carrying only the empty pEASY-E2 vector (see Fig. S1, lane 1), which was cultured and induced under the same conditions as those for the E. coli BL21(DE3)(pEASY-E2-EstD1) cells. The deduced molecular mass of four internal peptides from EstD1, LQHLNTWSWSGDR, VVNVGTSGNTVVDLQER, VKEMFLLSPFFLEPNR, and TVADETGATFIDVQAEFDER, match well with the primary amino acid sequences of EstD1, confirming that the sequence of EstD1 is correct (see Fig. S2).

Enzyme activity.

The activity of EstD1 was investigated using p-nitrophenol (p-NP) esters with various acyl-chain lengths, ranging from C2 to C16. EstD1 is active only on the short-chain p-nitrophenol esters of p-NPC2 and p-NPC4 and does not hydrolyze esters with acyl chains longer than four carbons. The catalytic efficiency toward p-NPC2 was approximately 26-fold higher than that toward p-NPC4 according to the highest maximum-initial-velocity kcat/Km values (Table 1). The fitted Michaelis-Menten curves of EstD1 for p-NP esters and α- and β-naphthyl acetate are shown in Fig. S3 and S4 in the supplemental material. No significant difference was found in the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) for the hydrolysis of β-naphthyl acetate and p-NPC2. This observation confirms the assumption that the enzyme EstD1 is an esterase (10, 23).

TABLE 1.

Kinetic parameters of recombinant EstD1a

| Substrate | Km (mM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (s−1 mM−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| p-NPC2 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 61.1 ± 2.4 | 191.7 |

| p-NPC4 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 1.13 ± 0.02 | 7.4 |

| α-Naphthyl acetateb | 0.44 ± 0.01 | 35.2 ± 0.5 | 79.6 |

| β-Naphthyl acetateb | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 42.6 ± 0.3 | 168.7 |

Reactions were conducted in triplicate in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.5, at 65°C in the standard reaction medium.

The experiment was carried out at pH 7.3 due to the substrate's chemical instability.

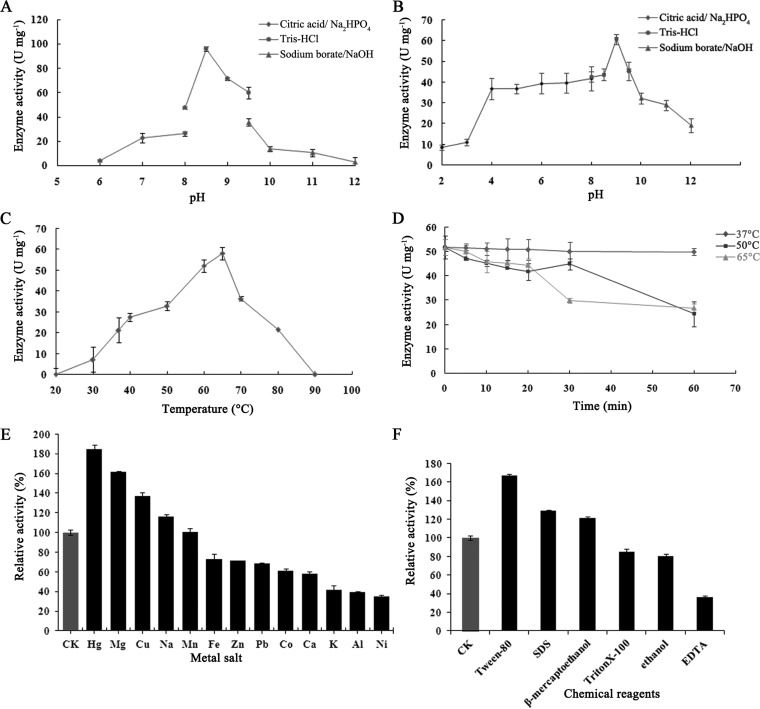

The effect of pH on EstD1 activity was measured in the pH range of 6.0 to 10.0, using p-NPC2 as a substrate at 37°C. Maximal activity was observed at pH 8.5 in Tris-HCl buffer. At a pH below 6.0 or above 9.0, there was substantial loss of activity (Fig. 3A). The pH stability analysis revealed that the enzyme was quite stable between pH 4.0 and 11.0, retaining more than 50% of the original activity after preincubation at that pH range for 1 h at 37°C (Fig. 3B).

FIG 3.

Biochemical characterization of EstD1. (A) Effect of pH on EstD1 activity. Reactions were performed in citrate phosphate (pH 5.0 to 8.0), Tris-HCl (pH 8.0 to 9.0), and boric acid (pH 9.0 to 12.0) buffers with identical ionic strengths (50 mM) at 37°C. (B) pH dependence of EstD1 stability. The enzyme was incubated for 1 h in buffers having various pH values (pH 2.0 to 12.0) at 37°C. (C) Effect of temperature on EstD1 activity was determined using p-NPC2 as the substrate in a temperature range of 20°C to 90°C in Tris-HCl buffer (50 mM; pH 8.5). (D) Thermostability of EstD1. The enzyme was incubated in Tris-HCl buffer (50 mM; pH 8.5) at 37, 50, and 65°C for 1 h. (E) Effects of metal salts on EstD1 stability. CK, without metal salt; Hg, Hg+; Mg, Mg2+; Cu, Cu2+; Na, Na+; Mn, Mn2+; Fe, Fe2+; Zn, Zn2+; Pb, Pb+; Co, Co2+; Ca, Ca2+; K, K+; Al, Al3+; Ni, Ni+ (1 mM). (F) Effects of chemical reagents on EstD1 stability. Reagents included Tween 80 (1% [vol/vol]), SDS (1 mM), β-mercaptoethanol (1 mM), Triton X-100, ethanol (1% [vol/vol]), and EDTA (1 mM). EstD1 was exposed to various inhibitors or activators in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) at 65°C for 5 min.

The effect of temperature on EstD1 activity was investigated by using p-NPC2 as a substrate at pH 8.5, with temperature ranging from 20°C to 90°C. Hydrolytic activity increased as temperature increased up to 65°C, and it decreased beyond that level. No activity was observed when the temperature was higher than 90°C (Fig. 3C). To assess temperature stability, EstD1 was incubated in Tris-HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 8.5) for 1 h at 37°C, 50°C, and 65°C. EstD1 displayed more than 50% hydrolytic activity at 50°C and 65°C. No enzyme activity loss was detected when enzymes were incubated at 37°C for 1 h (Fig. 3D). Optimal pH and temperature for enzyme hydrolysis were pH 8.5 and 65°C. The specific activity of the purified enzyme under optimal conditions was 0.32 ± 0.02 mM (Km) and 144.9 ± 5.6 U/mg (Vmax).

The effect of 13 different metal ions on EstD1 activity was examined by the addition of metal ions separately into the reaction mixture at a final concentration of 1.0 mM. Hg2+, Mg2+, Cu2+, and Na+ strongly activated enzyme activity (∼15 to 84% activation). Mn2+ had no obvious effect on the enzyme activity, while K+, Al3+, and Ni+ had strongly inhibitory effects (∼59 to 66% inhibition) (Fig. 4E). There was no obvious difference from YesT of B. subtilis 6633, in that Mn2+ and Mg2+ had no more than 25% inhibitory effects when they were tested at 2 mM (14). Chemical reagents such as Tween 80 (1%, vol/vol), SDS (1 mM), and β-mercaptoethanol (1 mM) strongly activated EstD1 activity (∼21 to 67% activation), while EDTA (1 mM) had a strong inhibitory effect (∼64% inhibition). This is in contrast to the activity of AXE as reported by Tian et al., who found that AXE activity was not influenced by EDTA and was strongly inhibited by Cu2+ at the same level tested (5). Triton X-100 and ethanol had little effect on enzyme activity (Fig. 3F), similar to the case of an SGNH hydrolase, Est24 from Sinorhizobium meliloti, reported by Bae et al. (27).

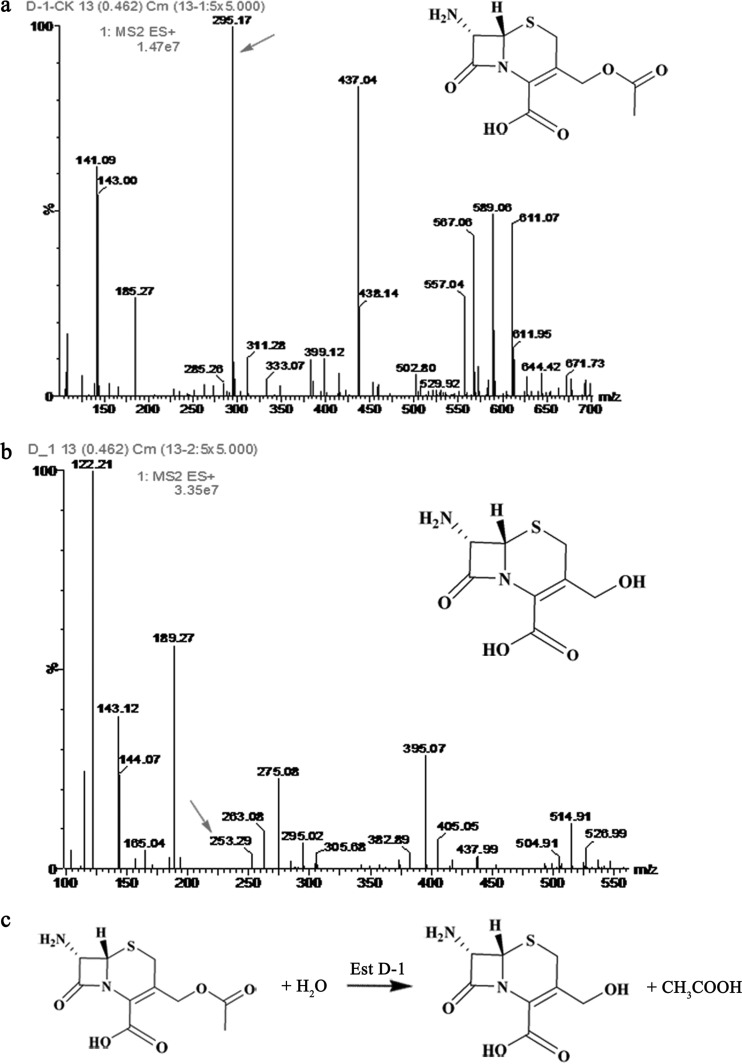

FIG 4.

Mass spectra of reaction solutions using 7-ACA as the substrate. (A) 7-ACA (16.5 mM; 4.5 g/liter) incubated at 25°C for 10 min without EstD1. (B) 7-ACA (16.5 mM; 4.5 g/liter) incubated with 100 μl EstD (10.441 mg/ml) at 25°C for 10 min. (C) Reaction of EstD1.

Examination of amino acid residues related to the hydrolytic activity of EstD1.

Essential amino acid residues in the enzyme active site could participate in substrate binding or in catalysis. It was difficult to assign a specific function to a particular residue on the basis of chemical modifications alone, but valuable information could be obtained. Loss in enzyme activity in the presence of a specific chemical modifier (phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF] and diethyl pyrocarbonate [DEPC]) suggested that serine and histidine residues play a role in enzyme activity (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The conserved amino acid residues of the proposed catalytic triad of EstD1 were identified within the GDSL motif at sequence positions 15 (Ser), 191 (Asp), and 194 (His), which form part of the conserved sequence motif DXXH, using sequence alignment (Fig. 2, asterisks). Thus, the chemical modification of these amino acids could provide valuable information for assigning them a function. To test whether Ser15, Asp191, and His194 form the catalytic triad of EstD1, an E. coli BL21(DE3) strain harboring pEASY-E2-hisS15A (where A indicates alanine), pEASY-E2-hisD191A, or pEASY-E2-hisH194A plasmid was separately constructed, and the His6-tagged S15A, D191A, and H194A mutant EstD1 proteins were purified (see Fig. S5A). Meanwhile, a negative control, the E. coli BL21(DE3) strain harboring pEASY-E2-hisS135A plasmid, also was constructed, and the His6-tagged S135A mutant was purified (see Fig. S5B). All three mutants, the S15A, D191A, and H194A mutants, lost most of the enzyme activity (see Fig. S5C) seen for the wild-type enzyme. However, the enzyme activity of S135A was nearly the same as that of wild-type enzyme EstD1 (see Fig. S5C). As shown in Table 2, the S15A and H194A mutants showed little activity (less than 10% compared to that of wild-type EstD1), and the D191A mutant was almost 7-fold less active than the wild type. These results strongly suggest that S15, D191, and H194 compose a catalytic triad.

TABLE 2.

Kinetic parameters of recombinant EstD1 and mutant variantsa

| Enzyme | Km (mM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (s−1 mM−1) | Sp act (U mg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EstD1 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 61.1 ± 2.4 | 191.7 | 95.8 ± 2.4 |

| S135A | 0.4 ± 0.05 | 72.2 ± 1.3 | 180.6 | 95.1 ± 3.2 |

| D191A | 0.51 ± 0.03 | 12.1 ± 0.1 | 23.8 | 15.9 ± 0.8 |

| H194A | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 6.8 ± 1.9 | 12.4 | 7.9 ± 0.9 |

Reactions were conducted in triplicate in Tris-HCl (50 mM, pH 8.5) with p-NPC2 as the substrate over a concentration range of 0.1 to 1.1 mM.

Deacetylase reaction mechanism of EstD1.

The products formed from the reaction catalyzed by His6-EstD1 were identified by comparison to the mass spectra (m/z) of the control reaction without enzyme by using ESI-MS. 7-ACA exhibits a peak at m/z 295.17. Two peaks corresponding to 7-ACA (m/z 295.17) and its deacetylated derivative, D-7-ACA (m/z 253.29), were detected in the reaction with EstD1 (Fig. 4B). However, only 7-ACA (m/z 295.17) was detected in the control reaction without EstD1 (Fig. 4A). The ion polarity of these compounds was positive ([M+Na]+). In addition, the deacetylase activity of EstD1 toward 7-ACA was confirmed by measuring the acetate released using an acetic acid detection kit. After the reaction, approximately 0.18 g/liter acetic acid was released. The activity of EstD1 toward 7-ACA was about 2.71 ± 0.03 U/mg, and the kcat/Km value was 0.37. Combined with the results described above, a reaction mode for the hydrolysis of 7-ACA by EstD1 was deduced (Fig. 4C).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we identified and characterized a 7-ACA deacetylase, EstD1, which can catalyze the hydrolysis of acetate from the 3′ position of 7-ACA. Thus far, B. subtilis (5, 6, 8, 13, 15), B. pumilus PS213 (7), B. halodurans C-125 (12), Thermotoga maritima MSB8 (10, 11), and Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum JW/SL-YS485 (9) species have been reported to have deacetylase activity toward 7-ACA. However, only a few enzymes involved in this process have been characterized, including AXE from B. subtilis CICC 20034 (5), CAH from B. subtilis SHS 0133 (6), Axe from B. pumilus PS213 (7), Cah from B. subtilis subsp. subtilis strain 168 (8), Axe1 from Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum JW/SL-YS485 (9), TM0077 from Thermotoga maritima MSB8 (10, 11), BH1115 from B. halodurans C-125 (12), CCD from Bacillus sp. strain KCCM10143 (13), and YesT from B. subtilis subsp. subtilis strain 168 (14). Sequence alignments show that EstD1 is not homologous to any of the above-described enzymes (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Moreover, EstD1 displayed no enzyme activity toward acetyl xylan in our study. Taken together, our results show that EstD1 may represent a new SGNH hydrolase in the CAZy family.

Sequence analyses suggested that EstD1 does not exhibit the conventional pentapeptide GXSXG but rather displays a feature common to SGNH hydrolases, such as an N-terminal catalytic domain that harbors a nucleophilic GDSL motif with the active-site serine residue and four invariant catalytic residues, Ser, Gly, Asn, and His (SGNH), in blocks I, II, III, and V (28). To firmly establish this annotation, the sequences of EstD1 along with those of representative members of the GDS(L) lipase family were compared to those of other organisms within the SGNH superfamily (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). The alignment revealed excellent conservation of the signature blocks centering around the four residues Ser, Gly, Asn, and His, as well as the catalytic triad residues Ser, Asp, and His, which is positioned within EstD1 according to the GDSL family consensus (that is very different from that of the α/β fold family; see Fig. S6). The conservation of the SGNH blocks and catalytic triad suggests that they have common critical functions that were preserved during evolution. Mutating the three putative catalytic residues of EstD1, Ser15, Asp191, and His194, led to the greatest loss of catalytic activity, suggesting that they all are necessary for activity and confirming that EstD1 is a GDS(L) serine esterase (see Fig. S5B). In addition, a three-dimensional structural model was generated using SWISS-MODEL to obtain structural insights into EstD1. The structure for PDB entry 3RJT, belonging to the GDSL family from A. acidocaldarius subsp. acidocaldarius DSM 446, with 66% identity to and 75% positivity for the query sequence, was used to build the EstD1 model (see Fig. S7A). In the first 9 docking poses, the binding affinities of different poses range from −5.2 to −4.4 kcal/mol. After carefully checking the binding mode between EstD1 and 7-ACA, the ligand was discovered to be well allocated to the cavity beside the active-site residues Ser15, Asp191, and His194 and formed stable interactions with active-site residues and other amino acids. Consistent with our experiment, the interactions between 7-ACA and active-site residues Ser15 and His194 were discovered to be more intense and frequent than the interaction formed with the negatively charged residue Asp191 (see Fig. S7C and D). Moreover, the docking pose with the highest binding free energy for 7-ACA was discovered to stably interact with His200 (see Fig. S7C). Asp191 cannot form strong electrostatic interactions with 7-ACA, mainly due to the lack of favorable space or a cavity to which the ligand can be allocated suitably (see Fig. S7B). This weakened interaction indicates that Asp191 is not the key active site that can influence the binding process and other activity of 7-ACA. In addition, the ESI-MS data also illustrated that 7-ACA can be transformed to D-7-ACA by EstD1 (Fig. 4).

Substrate specificities of purified EstD1 were determined using p-NPs of various chain lengths. EstD1 showed very high specificity toward p-NPC2 and had no activity with p-NP esters with carbon chains longer than four molecules (i.e., ≥C4), which is similar to AXE from B. subtilis CICC 20034 (5) and AXE (TM0077) from Thermotoga maritima (10). However, EstA from Thermotoga maritima has displayed activity against p-NP esters with carbon chains ranging from C2 to C10 (11). All of these enzymes exhibit 7-ACA deacetylase activity. EstD1 displayed relatively high activity toward p-NPC2 and β-naphthyl acetate, and the activity was 2.71 ± 0.03 U/mg when 7-ACA was used as the substrate. Purified EstD1 displayed remarkable thermostability and a broad range of pH tolerance. The optimal temperature for EstD1 activity was 65°C (Fig. 3C), and that of AXE from B. subtilis CICC 20034 was 50°C (5). The activity was barely changed when EstD1 was incubated at 37°C for 1 h, and the relative activity was above 50% when incubated at 50°C or 65°C for 1 h (Fig. 3D). This activity level was lower than those of EstA and AXE from Thermotoga maritima, which displayed optimal esterase activity at or above 95°C and 100°C, respectively (10, 11). However, 7-ACA was not considered their natural substrate, because the stability of 7-ACA at the optimal growth temperature (80°C) is very low (10, 11). Moreover, EstD1 was stable over a broad pH range (4.0 to 11.0), one that is broader than those of AXE from B. subtilis CICC 20034 (pH 6.0 to 11.0) (5), EstA from Thermotoga maritima (pH 5.0 to 11.0) (11), and AXE from Thermotoga maritima (pH 4.8 to 9.2) (10), and it even displayed activity when the pH reached 12.0 (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, EstD1 showed extremely high organic solvent tolerance (Fig. 3F) and also could be activated by some ions, which could be considered valuable characteristics when the enzyme is used in the presence of these solvents. We think that the activation of EstD1 by some ions and reagents is closely related to the growth environment of the bacterium A. tengchongensis. A. tengchongensis was isolated from a hot spring from Tengchong, China. The hot spring was located near a small village, and the local residents performed daily chores in the water, such as washing clothes, vegetables, and even killed animals. Thus, with the frequency human activities, A. tengchongensis has evolved for better viability and tolerance of the changes in the environment. Enzymes also may play very important roles during these processes. Although the activity of EstD1 toward 7-ACA is not high compared to that of other enzymes (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), its high temperature, pH, and organic solvent stability make it an attractive candidate for the production of new semisynthetic antibiotics. The abundance of currently available methods for the improvement of enzyme activity and function, such as directed evolution (29, 30), only add to its potential utility. Indeed, AXE from Penicillium purpurogenum was engineered by site-directed mutagenesis to accept a range of fatty acid esters of up to 14 carbons in length, whereas its wild-type preference was for acetate (31). Thus, it might be possible to engineer EstD1 to improve its activity toward 7-ACA. With the improvement of the activity of EstD1 toward 7-ACA, all of these characteristics would endow EstD1 with great potential for industrial application.

In conclusion, this study is the first to identify and characterize a novel SGNH hydrolase, EstD1, from the Alicyclobacillus genus. EstD1 can remove the acetyl group from the C-3′ position of 7-ACA, leading to the formation of deacetylated 7-ACA, which is a critical intermediate in the industrial and medical production of semisynthetic β-lactam antibiotics. However, without a three-dimensional structure, we are dependent on modeling, kinetic information, and site-directed mutagenesis results, such as those provided in this study, which have confirmed that EstD1 functions as an SGNH esterase. This study will greatly facilitate our general understanding of esterases from the SGNH superfamily. Further studies, such as directed evolution, will be required to improve the activity of EstD1 toward 7-ACA to make it more applicable to the large-scale industrial production of β-lactam antibiotics.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the National Key Technology Support Program (grant 2013BAD10B01), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 31160229 and 31460022), and the Scientific Research Fund of Yunnan Education Department (grant 2014Y141).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.00471-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fechtig B, Peter H, Bickel H, Vischer E. 1968. Concerning the preparation of 7-amino-cephalosporanic acid. Helv Chim Acta 51:1108–1119. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19680510513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeffery JD, Abraham EP, Newton GG. 1961. Deacetylcephalosporin C. Biochem J 81:591–596. doi: 10.1042/bj0810591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Callaghan CH, Muggleton PW. 1963. The formation of metabolites from cephalosporin compounds. Biochem J 89:304–308. doi: 10.1042/bj0890304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantarel BL, Coutinho PM, Rancurel C, Bernard T, Lombard V, Henrissat B. 2009. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res 37:233–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tian Q, Song P, Jiang L, Li S, Huang H. 2014. A novel cephalosporin deacetylating acetyl xylan esterase from Bacillus subtilis with high activity toward cephalosporin C and 7-aminocephalosporanic acid. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:2081–2089. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitsushima K, Takimoto A, Sonoyama T, Yagi S. 1995. Gene cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of a cephalosporin-C deacetylase from Bacillus subtilis. Appl Environ Microbiol 61:2224–2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Degrassi G, Kojic M, Ljubijankic G, Venturi V. 2000. The acetyl xylan esterase of Bacillus pumilus belongs to a family of esterases with broad substrate specificity. Microbiology 146:1585–1591. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-7-1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vincent F, Charnock SJ, Verschueren KH, Turkenburg JP, Scott DJ, Offen WA, Roberts S, Pell G, Gilbert HJ, Davies GJ, Brannigan JA. 2003. Multifunctional xylooligosaccharide/cephalosporin C deacetylase revealed by the hexameric structure of the Bacillus subtilis enzyme at 1.9 Å resolution. J Mol Biol 330:593–606. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00632-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lorenz WW, Wiegel J. 1997. Isolation, analysis, and expression of two genes from Thermoanaerobacterium sp. strain JW/SL YS485: a beta-xylosidase and a novel acetyl xylan esterase with cephalosporin C deacetylase activity. J Bacteriol 179:5436–5441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levisson M, Han GW, Deller MC, Xu Q, Biely P, Hendriks S, Ten Eyck LF, Flensburg C, Roversi P, Miller MD, McMullan D, von Delft F, Kreusch A, Deacon AM, van der Oost J, Lesley SA, Elsliger MA, Kengen SW, Wilson IA. 2012. Functional and structural characterization of a thermostable acetyl esterase from Thermotoga maritima. Proteins 80:1545–1559. doi: 10.1002/prot.24041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levisson M, Sun L, Hendriks S, Swinkels P, Akveld T, Bultema JB, Barendregt A, van den Heuvel RH, Dijkstra BW, van der Oost J, Kengen SW. 2009. Crystal structure and biochemical properties of a novel thermostable esterase containing an immunoglobulin-like domain. J Mol Biol 385:949–962. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Navarro-Fernández J, Martínez-Martinez I, Montoro-García S, García-Carmona F, Takami H, Sánchez-Ferrer Á. 2008. Characterization of a new rhamnogalacturonan acetyl esterase from Bacillus halodurans C-125 with a new putative carbohydrate binding domain. J Bacteriol 190:1375–1382. doi: 10.1128/JB.01104-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi D, Kim Y, Chung I, Lee S, Kang S, Han K. 2000. Gene cloning and expression of cephalosporin-C deacetylase from Bacillus sp. KCCM10143. J Microbiol Biotechnol 10:221–226. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martínez-Martínez I, Navarro-Fernández J, Lozada-Ramírez JD, García-Carmona F, Sánchez-Ferrer Á. 2008. YesT: a new rhamnogalacturonan acetyl esterase from Bacillus subtilis. Proteins 71:379–388. doi: 10.1002/prot.21705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Molgaard A, Kauppinen S, Larsen S. 2000. Rhamnogalacturonan acetylesterase elucidates the structure and function of a new family of hydrolases. Structure 8:373–383. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee LC, Liaw YC, Lee YL, Shaw JF. 2007. Enhanced preference for pi-bond containing substrates is correlated to Pro110 in the substrate-binding tunnel of Escherichia coli thioesterase I/protease I/lysophospholipase L(1). Biochim Biophys Acta 1774:959–967. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lescic Asler I, Ivic N, Kovacic F, Schell S, Knorr J, Krauss U, Wilhelm S, Kojic-Prodic B, Jaeqer KE. 2010. Probing enzyme promiscuity of SGNH hydrolases. Chembiochem 11:2158–2167. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie Z, Xu B, Ding J, Liu L, Zhang X, Li J, Huang Z. 2013. Heterologous expression and characterization of a malathion-hydrolyzing carboxylesterase from a thermophilic bacterium, Alicyclobacillus tengchongensis. Biotechnol Lett 35:1283–1289. doi: 10.1007/s10529-013-1195-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. 2011. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods 8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gouet P, Courcelle E, Stuart DI, Metoz F. 1999. ESPript: analysis of multiple sequence alignments in PostScript. Bioinformatics 15:305–308. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bradford MM. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levisson M, van der Oost J, Kengen SW. 2007. Characterization and structural modeling of a new type of thermostable esterase from Thermotoga maritima. FEBS J 274:2832–2842. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biasini M, Bienert S, Waterhouse A, Arnold K, Studer G, Schmidt T, Kiefer F, Cassarino TG, Bertoni M, Bordoli L, Schwede T. 2014. SWISS-MODEL: modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Res 42:W252–W258. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trott O, Olson AJ. 2010. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem 31:455–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, Olson JA. 2009. Auto Dock 4 and Auto Dock Tools 4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem 30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bae SY, Ryu BH, Jang E, Kim S, Kim TD. 2013. Characterization and immobilization of a novel SGNH hydrolase (Est24) from Sinorhizobium meliloti. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 97:1637–1647. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alalouf O, Balazs Y, Volkinshtein M, Grimpel Y, Shoham G, Shoham Y. 2011. A new family of carbohydrate esterases is represented by a GDSL hydrolase/acetylxylan esterase from Geobacillus stearothermophilus. J Biol Chem 286:41993–42001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.301051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dickinson BC, Packer MS, Badran AH, Liu DR. 2014. A system for the continuous directed evolution of proteases rapidly reveals drug-resistance mutations. Nat Commun 5:5352. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang S, Wu G, Feng S, Liu Z. 2014. Improved thermostability of esterase from Aspergillus fumigatus by site-directed mutagenesis. Enzyme Microb Technol 64–65:11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colombres M, Garate JA, Lagos CF, Araya-Secchi R, Norambuena P, Quiroz S, Larrondo L, Acle-Perez T, Eyzaguirre J. 2008. An eleven amino acid residue deletion expands the substrate specificity of acetyl xylan esterase II (AXE II) from Penicillium purpurogenum. J Comput Aided Mol Des 22:19–28. doi: 10.1007/s10822-007-9149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.