ABSTRACT

Pectobacterium wasabiae (previously known as Erwinia carotovora) is an important plant pathogen that regulates the production of plant cell wall-degrading enzymes through an N-acyl homoserine lactone-based quorum sensing system and through the GacS/GacA two-component system (also known as ExpS/ExpA). At high cell density, activation of GacS/GacA induces the expression of RsmB, a noncoding RNA that is essential for the activation of virulence in this bacterium. A genetic screen to identify regulators of RsmB revealed that mutants defective in components of a putative Trk potassium transporter (trkH and trkA) had decreased rsmB expression. Further analysis of these mutants showed that changes in potassium concentration influenced rsmB expression and consequent tissue damage in potato tubers and that this regulation required an intact Trk system. Regulation of rsmB expression by potassium via the Trk system occurred even in the absence of the GacS/GacA system, demonstrating that these systems act independently and are both required for full activation of RsmB and for the downstream induction of virulence in potato infection assays. Overall, our results identified potassium as an essential environmental factor regulating the Rsm system, and the consequent induction of virulence, in the plant pathogen P. wasabiae.

IMPORTANCE Crop losses from bacterial diseases caused by pectolytic bacteria are a major problem in agriculture. By studying the regulatory pathways involved in controlling the expression of plant cell wall-degrading enzymes in Pectobacterium wasabiae, we showed that the Trk potassium transport system plays an important role in the regulation of these pathways. The data presented further identify potassium as an important environmental factor in the regulation of virulence in this plant pathogen. We showed that a reduction in virulence can be achieved by increasing the extracellular concentration of potassium. Therefore, this work highlights how elucidation of the mechanisms involved in regulating virulence can lead to the identification of environmental factors that can influence the outcome of infection.

INTRODUCTION

Pectobacterium spp. are Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae family. They cause soft-rot disease in several plants, including potatoes, carrots, and cabbages. Damage to plant tissues is caused by the action of a mixture of cellulases, proteases, pectate lyases (Pel), pectin lyases, and polygalacturonases secreted by these bacteria. The enzymes degrade plant cell wall components, releasing nutrients that fuel bacterial growth. Production of these plant cell wall-degrading enzymes (PCWDEs) is carefully coordinated by a complex multipartite regulatory system that integrates internal and external information to ensure that virulence is only switched on when conditions are optimal (1).

In Pectobacterium wasabiae (previously Erwinia carotovora [2]), production of PCWDEs is regulated mainly through two signal transduction systems. These systems coordinately control the expression and activity of the global posttranscriptional regulator RsmA, which represses the expression of PCWDEs by binding to their mRNAs. Transcription of rsmA is regulated by ExpI/ExpR, a typical quorum sensing system that relies on an N-acyl homoserine lactone (AHL) autoinducer (3–5). The second sensory pathway regulating RsmA, and therefore virulence, is the GacS/GacA two-component system (also known as ExpS/ExpA). The response regulator GacA is the major transcriptional activator of RsmB, a noncoding RNA that binds RsmA (6). This binding of RsmA by RsmB inhibits the RsmA-mediated repression of PCWDEs, ultimately promoting the expression of these virulence factors (7). Therefore, activation of RsmB expression is essential to induce virulence in P. wasabiae. Homologues of the Gac/Rsm system exist in many Gram-negative bacteria, including the Gac/Rsm system in Pseudomonas spp. and the BarA/UvrY/Csr system in Escherichia coli. Though these systems regulate a wide range of important physiological functions in bacteria, including primary and secondary metabolism, biofilm formation, motility, and virulence (reviewed in references 8 and 9), the chemical identity of the molecule(s) responsible for their activation remains unknown. Accumulation of intermediates of the Krebs cycle have been shown to stimulate the Gac/Rsm systems in Pseudomonas fluorescens and Vibrio fischeri (10, 11), but the physiological conditions that lead to the accumulation of these metabolites with the consequent activation of the Gac/Rsm system are still poorly understood. Additionally, short-chain fatty acids, such as acetate, formate, propionate, and butyrate, have been shown to influence the expression of csrB (a functional rsmB homologue) in E. coli or Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium at low pH, but the stimuli that activate the system at neutral pH have not been identified (12, 13).

To identify the physiological stimuli involved in the activation of the Gac/Rsm system and to understand how this system regulates virulence in the well-characterized P. wasabiae strain SCC3193, we performed a genetic screen to identify mutants affected in the expression of rsmB, the main target of the Gac/Rsm system in this bacterium. The screen revealed 5 mutants defective in genes coding for components of a putative homologue of the E. coli Trk potassium uptake system (10). Therefore, we investigated the importance of potassium and the Trk system to the regulation of RsmB. Our results demonstrated that extracellular potassium is a critical environmental factor influencing virulence in Pectobacterium spp.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

All of the strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. P. wasabiae strains are derived from the wild-type (WT) strain SCC3193 (14). Strains were grown at 30°C with aeration in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, M9 minimal medium (MM), or minimal potassium medium (15) with 0.4% (wt/vol) glycerol. When specified, the medium was supplemented with 0.4% polygalacturonic acid (PGA; Sigma P3850) to induce the expression of PCWDEs. Where mentioned, KCl was added at various final concentrations. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: 100 mg liter−1 ampicillin (Amp), 100 mg liter−1 streptomycin (Str), 50 mg liter−1 kanamycin (Kan), 50 mg liter−1 spectinomycin (Spec), and 25 mg liter−1 chloramphenicol (Cm). To assess bacterial growth, the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was determined by measuring absorbance at 600 nm in the Bioscreen C reader system (multiplate reader; Oy Growth Curves Ab Ltd.).

Genetic and molecular techniques.

Primers used in this study are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. The plasmid carrying the rsmB promoter fused to the green fluorescence protein (GFP) (PrsmB::gfp) was constructed using a modified version of the promoterless::gfp vector pCMW1 (16). First, the chloramphenicol resistance gene (cm) was amplified by PCR from pKD3 (17) using P0276-pKD3/4(BamHI) and P0277-pKD3/4(BamHI) primers and introduced into pCMW1, yielding PRSV59. Next a 392-bp fragment containing the promoter region of rsmB was amplified by PCR using the P0528-rsmB(SphI) and P0529-rsmB(SalI) primers and was ligated into PRSV59, yielding pRSV206. Deletion mutants were constructed by chromosomal gene replacement with an antibiotic marker using the λ Red recombinase system (17, 18). The DNA region of gacA, including approximately 500 bp upstream and 500 bp downstream of the gene, was amplified by PCR and cloned into pUC18 (19) using SalI and SacI. This construct, containing the gacA gene and its flanking regions, was divergently amplified by PCR using primers to introduce an XhoI restriction site in the 5′ and 3′ regions of the gene. The streptomycin resistance gene (str) was amplified from pKNG101 (20) with primers containing the XhoI restriction site. The amplified fragment containing the gene for streptomycin resistance was digested with XhoI and was introduced into the XhoI-digested PCR fragment. The final construct contained the antibiotic resistance marker flanked by the upstream and downstream regions of gacA. The 500-bp–str–500-bp fragment was amplified by PCR, and approximately 3 ng of DNA was electroporated into a strain expressing the λ Red recombinase system from pKD46 to allow recombination (17). To construct the trkA+ and trkH+ complementation plasmids, a 400-bp–trkA–400-bp fragment and a 400-bp trkH fragment were amplified from SCC3193 and were cloned into pOM18 using SalI and SacI or PstI and XbaI, respectively. pOM18 was constructed by amplifying the multiple cloning site of pUC18 and by cloning it into the BglII site created from the divergently amplified pOM1 (21). PCRs for cloning purposes were performed using the proofreading Herculase II polymerase (Agilent). Dream Taq polymerase (Fermentas) was used for all other PCRs. Digestions were done using FastDigest enzymes (Fermentas), and ligations were performed with T4 DNA ligase (New England BioLabs). All cloning steps were performed in E. coli DH5α. All mutants and constructs were confirmed by sequencing at the Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência sequencing facility.

Isolation of transposon insertion mutants with low rsmB expression.

A library of 15,126 SCC3193 mutants was constructed by transposon mutagenesis using the EZ-Tn5 <R6Kγori/KAN-2>Tnp Transposome kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Epicentre). Mutants were tested in 96-well plates for Pel activity levels using the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) method (22). The pRSV206 plasmid, which contained the PrsmB::gfp fusion, was introduced into mutants with low Pel activity by electroporation. To measure rsmB expression levels, these strains were grown in multiwell plates at 30°C in MM supplemented with Cm and Kan and were diluted 1:100 into fresh medium in black multiwell plates. After 24 h of growth, GFP expression was assessed using a multilabel counter (Victor3; PerkinElmer). We identified 29 mutants with <75% of rsmB expression level shown by WT bacteria. The transposon insertion site of these mutants was amplified by a two-step arbitrary PCR using the transposon-specific primers P0058-Kan_SP1 and P0057-Kan_SP2 and the arbitrary primers P0052-Arb1K, P0053-Arb2k, and P0054-Arb6K (23, 24). The insertion site was identified by DNA sequencing coupled with BLAST analysis against the Pectobacterium SCC3193 complete genome sequence (NCBI Taxonomy ID: 1166016).

Analysis of expression of PrsmB::gfp.

Analysis of rsmB expression was performed by flow cytometry. Mutant and WT strains of P. wasabiae SCC3193 containing the rsmB reporter fusion were grown overnight in MM supplemented with Cm and Kan and were then inoculated into fresh medium in multiwell plates at a starting OD600 of 0.02. Aliquots were collected at an OD600 of 0.3 or 0.4, as indicated in the figure legends. Cells were diluted 1:100 into phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the fluorescence intensity of GFP per cell was assessed immediately in the flow cytometer (LSRFortessa; BD). Results were analyzed with Flowing Software v2.5.1. A minimum of 5,000 GFP-positive single cells were acquired per sample and were analyzed for their rsmB expression. rsmB expression of the mutants with the PrsmB::gfp fusion is reported as the median GFP expression of the GFP-positive single cells in arbitrary units (a.u.).

Pel activity assay.

Overnight cultures of bacterial strains were diluted to an OD600 of 0.02 in fresh LB supplemented with PGA in multiwell plates. Bacteria were subcultured to an OD600 of 0.4, at which time cell-free supernatants were harvested by centrifugation. Extracellular Pel activity was measured using the previously described TBA colorimetric method (22). Briefly, supernatants were incubated for 3 h with the substrate mixture at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by acidification, TBA (Sigma T5500) was added, and the reaction mixture was boiled for 1 h. The pink coloration was measured at 548 nm using a multilabel counter (Victor3; Perkin-Elmer). The absorbance values obtained at 548 nm were divided by the OD600 of the corresponding cultures.

P. wasabiae virulence assay.

Virulence was determined using a modified protocol to assess maceration of potato tubers (25). Potatoes were washed and surface sterilized by soaking for 10 min in 10% bleach followed by 10 min in 70% ethanol. To prepare bacteria for inoculation, overnight cultures were washed twice in PBS, which contained a total of 4.5 mM potassium, or in PBS with various concentrations of KCl as indicated. Thirty microliters of cells at an OD600 of 0.05 was inoculated into previously punctured potatoes and incubated at 28°C with relative humidity above 90% for 48 h. After incubation, potatoes were sliced and macerated tissue was collected and weighed. To quantify the inoculum, serial dilutions of this bacterial suspension were performed in PBS and were plated, and bacterial growth was quantified by the number of CFU present in 30 μl.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed using Graphpad Prism 6 software and R program v3.0.2. The Mann-Whitney test was performed to determine statistical significance, and P values were adjusted using the Holm-Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. An adjusted P value of <0.05 was used as the cutoff for statistical significance.

RESULTS

Mutants with mutations in the Trk potassium uptake system are impaired in rsmB expression and production of PCWDEs.

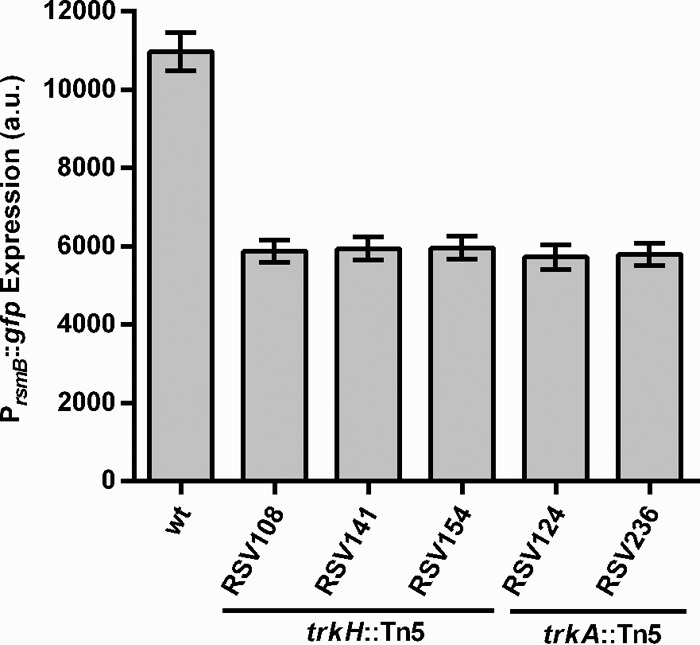

To identify regulators of the Gac/Rsm system we generated and screened a library of 15,126 P. wasabiae SCC3193 transposon mutants for changes in Pel activity. We obtained 58 mutants with reduced Pel activity compared to that of the WT strain. rsmB expression levels were then tested in these mutants following the introduction of a plasmid-encoded rsmB promoter-GFP fusion construct (pRSV206-PrsmB::gfp) into the mutants. Of these, 29 independent mutants showed <75% rsmB expression in comparison to the WT strain (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). From those 29 mutants, five were found to have transposon insertions in genes annotated as components of a putative Trk system, which is involved in potassium uptake in E. coli (26). As shown in Fig. 1, all five mutants had an approximately 2-fold reduction in the expression of the rsmB::gfp fusion compared to WT levels. Three of those mutants (RSV108, RVS141, and RSV154) had transposon insertions in the W5S_4400 gene, whose product is annotated as the potassium uptake protein TrkH. This protein has 89% sequence identity with one of the potassium uptake channel proteins (TrkH) from E. coli. This bacterium has two redundant Trk channel proteins, TrkH and TrkG; disruption of the two proteins is required for the abolishment of potassium uptake by the Trk system. In contrast, P. wasabiae has only one putative Trk channel protein, similar to most other bacteria containing the Trk transporter. The other two mutants (RSV124 and RSV236) had transposon insertions in the W5S_4132 gene, whose product is annotated as the potassium uptake protein TrkA. This protein shares 85% sequence identity with the TrkA protein from E. coli, a regulator of the Trk potassium uptake system. In E. coli, disruption of trkA results in a lower rate of potassium uptake by the Trk system (26). To investigate the role of the Trk system in the regulation of RsmB, one mutant with a transposon insertion in the trkH gene (RSV141) and another with an insertion in the trkA gene (RSV236) were selected for further characterization.

FIG 1.

Trk mutants have low rsmB expression. Expression of PrsmB::gfp promoter fusion from pRSV206 in P. wasabiae WT and RSV108 (trkH::Tn5), RSV141 (trkH::Tn5), RSV154 (trkH::Tn5), RSV124 (trkA::Tn5), or RSV236 (trkA::Tn5) mutant strains was measured by fluorescence flow cytometry of cells grown for 24 h in MM. Error bars represent standard deviations (SD); n = 3.

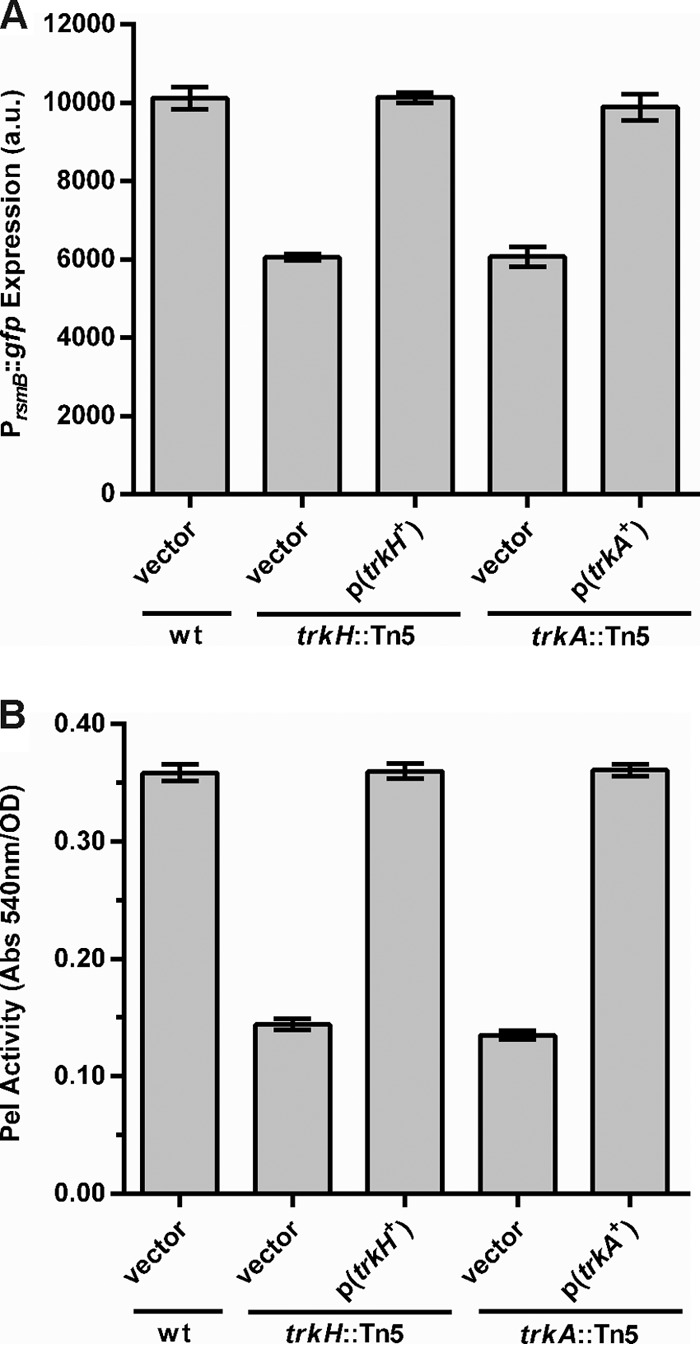

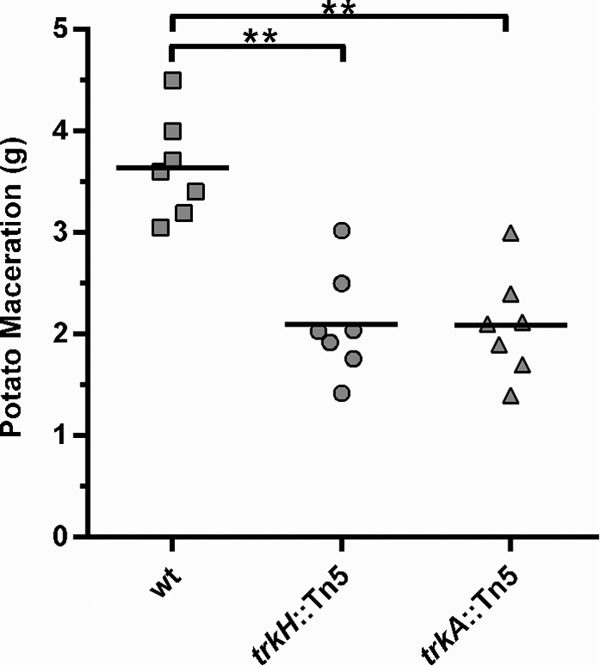

We tested the trkH::Tn5 and trkA::Tn5 mutants for complementation in trans with the trkH or trkA gene, respectively, for rsmB expression and Pel activity (Fig. 2). Due to the growth defect for both trkH and trkA mutant strains (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), cells were collected and analyzed at the same cell density (OD600 = 0.4). PrsmB::gfp expression was restored to WT levels in trkH and trkA mutants when the respective genes were expressed under the control of their own promoter, but it remained low in mutants carrying the empty vector (Fig. 2A). When tested for their ability to produce PCWDEs, these mutants had a >2-fold decrease in extracellular Pel activity, which was restored to WT levels upon expression of either trkH or trkA in trans (Fig. 2B). These data showed that the reduction in rsmB expression and the consequent effect upon the downstream induction of PCWDEs observed were a consequence of the disruption of trkH and trkA by the transposon insertion, and they suggested that the Trk system could affect regulation of virulence in P. wasabiae. We therefore investigated the ability of the selected trk mutants to cause tissue damage in potatoes. As shown in Fig. 3, the mutant strains were impaired in virulence, showing an approximately 40% reduction in the mass of macerated potato tuber tissue compared to that in tubers infected with WT bacteria.

FIG 2.

Complementation of the trkH and trkA mutants. (A) Expression of a PrsmB::gfp promoter fusion was measured in WT bacteria harboring the control vector (pOM18), the trkH::Tn5 mutant carrying either the pOM18 empty vector or the vector expressing trkH, p(trkH+), and the trkA::Tn5 mutant carrying either the pOM18 empty vector or the vector expressing trkA, p(trkA+). Fluorescence was measured in cells collected from cultures grown to an OD600 of 0.4 in MM. (B) Pel activity was measured in cell-free supernatants from cultures of the bacterial strains indicated above grown in LB supplemented with PGA at an OD600 of 0.4. Error bars represent standard errors of the means (SEM); n = 6.

FIG 3.

Mutants in the Trk system are impaired in virulence. The virulence of WT bacteria and trkH::Tn5 and trkA::Tn5 mutants was measured by quantification of the mass of potato tuber maceration induced by these bacteria 48 h after inoculation of the potato tubers. Potatoes were inoculated with approximately 3 × 105 cells of the respective strain grown overnight in LB. **, P < 0.01; n = 7. This is a representative experiment from three independent experiments.

Extracellular potassium levels influence rsmB expression.

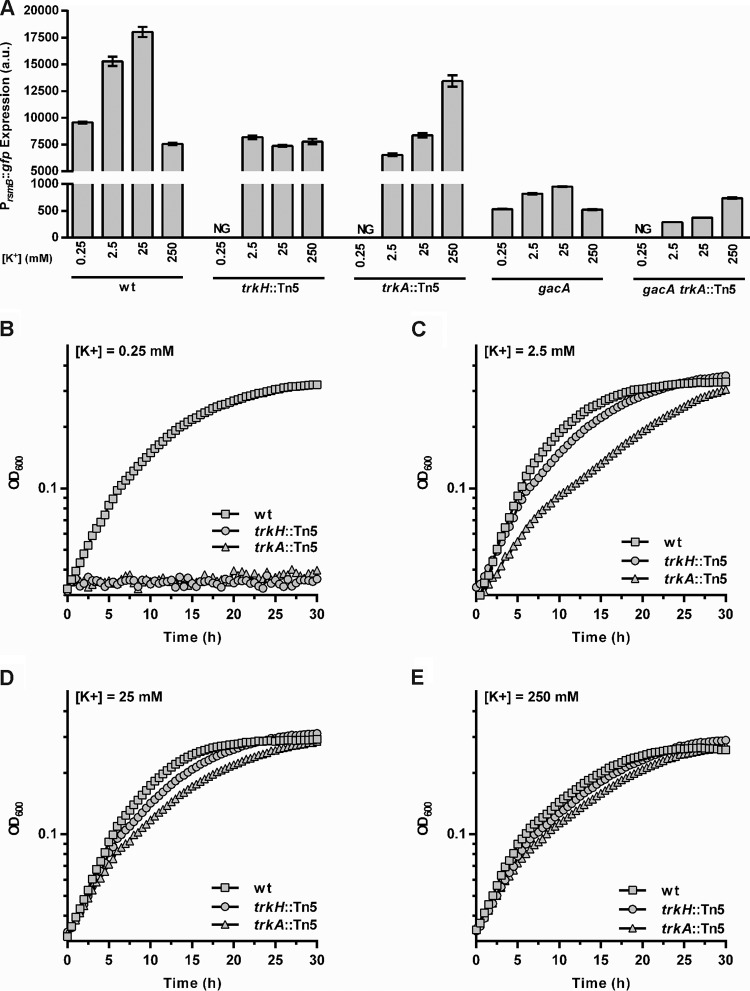

The requirement for a functional Trk potassium uptake system for full activation of rsmB expression indicated that induction of virulence might in fact be regulated by potassium. Therefore, we analyzed rsmB expression levels in WT P. wasabiae grown in different concentrations of potassium. Bacteria grown in 0.25, 2.5, or 25 mM potassium induced rsmB expression by responding positively to increasing concentrations of potassium. However, in cells grown in 250 mM potassium, induction was as low as that observed in cells with 0.25 mM potassium (Fig. 4A).

FIG 4.

Effect of extracellular potassium on rsmB expression and growth in P. wasabiae. (A) The expression of the rsmB promoter fusion (PrsmB::gfp) was measured by flow cytometry of cultures of WT bacteria and trkA::Tn5, trkH::Tn5, gacA, gacA trkA::Tn5 mutants grown to an OD600 of 0.3 in minimal potassium medium supplemented with a final potassium concentration of 0.25 mM, 2.5 mM, 25 mM, or 250 mM. NG, no growth. Error bars represent SEM; n = 6. (B to E) The OD600 was measured throughout growth for WT bacteria and trkH::Tn5 and trkA::Tn5 mutants in minimal potassium medium supplemented with 0.25, 2.5, 25, or 250 mM KCl (for growth rates, see Table S4 in the supplemental material).

To verify that this regulation was dependent upon the Trk system, we analyzed rsmB expression in the trkA and trkH mutants cultured in the same range of potassium concentrations. As neither mutant grew in the lowest concentration tested (0.25 mM) (Fig. 4B), it was not possible to determine the level of rsmB expression in these mutants under these conditions. Importantly, this lack of growth shows that the Trk system is required for the growth of P. wasabiae in low concentrations of potassium, supporting the predicted function of these genes in potassium uptake. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 4A, the two mutants yielded distinct phenotypes with regard to potassium-dependent regulation of rsmB expression, which is in agreement with the putative functions assigned by similarity to the Trk system in E. coli. In the trkH mutant, where based on knowledge from E. coli, we would expect Trk-dependent potassium uptake to be absent, rsmB expression was low when it was grown in the tested potassium concentrations. This result showed that no potassium-dependent regulation of rsmB expression was observed upon disruption of the putative Trk potassium channel protein. In contrast, trkA mutants retained some ability to induce rsmB expression in response to changes in potassium availability, though 100-fold higher concentrations (250 mM) were needed to reach the level of activation seen in the WT cultured with 2.5 mM potassium. This suggests that Trk-dependent potassium uptake is less efficient in P. wasabiae trkA mutants than in the WT strain, which is similar to what was reported for E. coli (26). Together these phenotypes support the prediction that these genes are part of a functional homologue of the Trk potassium transport system in P. wasabiae, and these results show that this system is involved in the potassium-mediated regulation of RsmB.

Previous studies of the Gac/Rsm system in pectobacteria and other bacterial species have established GacA as the key response regulator responsible for activating the expression of rsmB. To verify whether potassium-dependent regulation of RsmB occurs via this two-component system, we measured rsmB expression in mutants lacking gacA and determined the effect of potassium in the absence of this response regulator. In line with current literature, disruption of gacA resulted in reduced expression of rsmB compared to that of WT bacteria (Fig. 4A). Nonetheless, rsmB expression in the gacA mutant can still be induced with intermediate levels of potassium, which is similar to what was observed with WT bacteria. Furthermore, deletion of gacA in a trkA mutant background (gacA trkA::Tn5 double mutant) resulted in the same potassium-dependent activation of rsmB expression observed for the trkA single mutant. Therefore, potassium-dependent regulation of RsmB is not mediated by the GacS/GacA signal transduction pathway.

Overall, our results demonstrate that rsmB expression is regulated by extracellular levels of potassium and that this regulation requires the Trk system but is independent of the GacS/GacA system.

Virulence in P. wasabiae is regulated by the extracellular concentration of potassium.

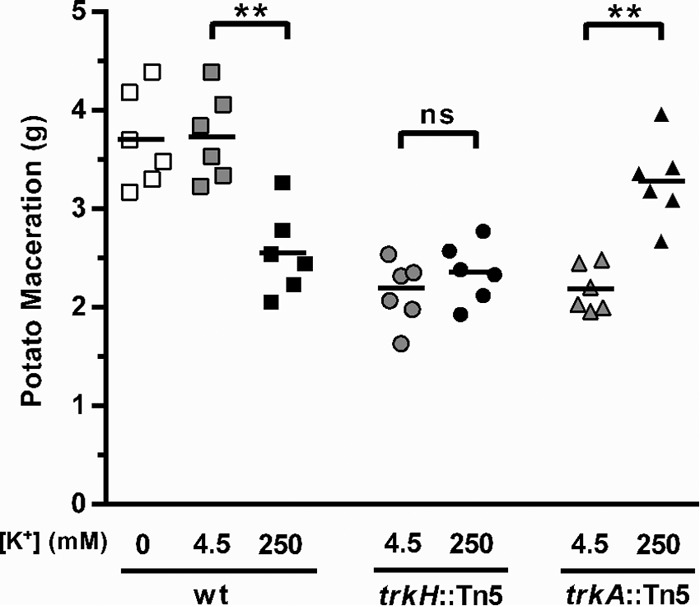

Next, we tested whether the potassium-dependent effect on rsmB expression observed in the in vitro studies described above had consequences for virulence in vivo using the maceration of potato tubers. We tested whether supplementation of the inoculum with different concentrations of potassium affected the outcome of infection. In agreement with the in vitro results for rsmB expression, high concentrations of extracellular potassium (250 mM) had an inhibitory effect on the virulence of WT bacteria; less tissue maceration was observed in potatoes inoculated with cells resuspended in buffer with 250 mM potassium than in potatoes infected with bacteria prepared in buffer supplemented with 4.5 mM potassium or no potassium (squares in Fig. 5). As for the mutants, the virulence of the trkH mutant was low at all potassium concentrations tested while that of the trkA mutant was also low at low potassium concentrations, though supplementation of high concentrations of potassium (250 mM) resulted in an increase in virulence to near WT levels (Fig. 5). The results for the trkH and trkA mutant strains are in full agreement with their respective phenotypes for RsmB induction obtained in vitro (Fig. 4A).

FIG 5.

Regulation of virulence by extracellular potassium concentration. The virulence of WT bacteria and trkH::Tn5 and trkA::Tn5 mutants was measured by quantification of the mass of macerated tissue 48 h after inoculation of potato tubers. Cells were cultured overnight in LB (approximately 8 mM potassium) and were harvested and resuspended in potassium-free PBS (WT only) or PBS supplemented with a final concentration of either 4.5 mM or 250 mM potassium. Potatoes were inoculated with approximately 3 × 105 cells of the respective strain at the different potassium concentrations. Error bars represent SEM; n = 6; **, P < 0.01; ns, not significant. This is a representative experiment from three independent experiments.

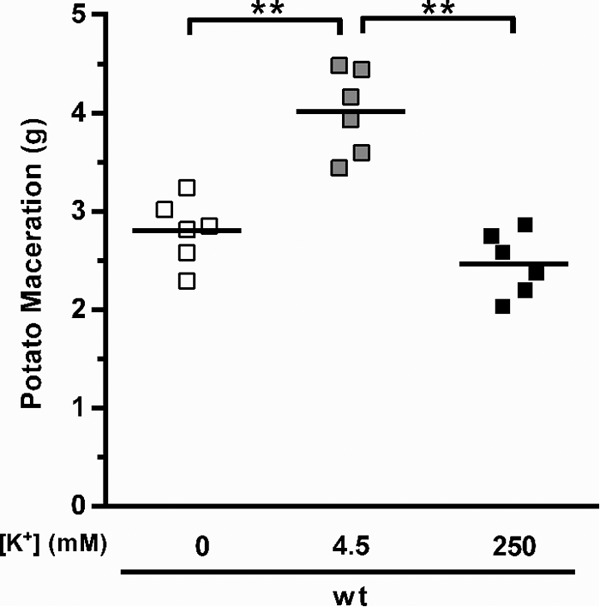

Nonetheless, no increase in the virulence of the WT bacteria occurred when potatoes were inoculated with cells prepared in 4.5 mM potassium compared to the virulence in those prepared without the addition of potassium. However, bacterial inocula were grown in LB (a medium that contains approximately 8 mM potassium [15]) prior to infections, and because our data showed that concentrations higher than 2.5 mM were sufficient to induce rsmB expression in WT bacteria in vitro (Fig. 4), we reasoned that such induction might sustain rsmB expression, and therefore virulence, during infection. To address this possibility and to determine if extracellular potassium at the site of infection is essential to induce virulence, WT P. wasabiae was grown under noninducing conditions in minimal potassium medium supplemented with low potassium (0.25 mM) and was then resuspended in buffer with different potassium concentrations before inoculation into potatoes. The trkH and trkA mutant strains were not tested under these conditions due to their lack of growth in low concentrations of potassium (Fig. 4B). As shown in Fig. 6, WT bacteria grown in 0.25 mM caused some tissue maceration even when no potassium was added to the inoculum, but importantly, an increase in virulence was observed with the addition of 4.5 mM potassium (Fig. 6). These results demonstrate that the addition of potassium at the time of infection induced virulence in cells that were grown under noninducing conditions. Again, high concentrations of potassium (250 mM) inhibited the induction of virulence; the mass of macerated tissue was as low under these conditions as when no potassium was added to the inoculum (Fig. 6).

FIG 6.

Induction of virulence by extracellular potassium. Virulence of WT bacteria was measured by determining the mass of damaged tissue 48 h after the infection of potato tubers. Potatoes were inoculated with approximately 3 × 105 cells of the respective strain grown overnight in minimal potassium medium supplemented with a final potassium concentration of 0.25 mM and resuspended in potassium-free PBS (0 mM), in PBS (4.5 mM potassium), or in PBS supplemented with potassium to a final concentration of 250 mM. Error bars represent SEM; n = 6; **, P < 0.01. This is a representative experiment from two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

The small RNA RsmB has a major role in the signaling network controlling virulence in P. wasabiae by preventing RsmA-mediated repression of PCWDE expression. Consequently, activation of rsmB transcription is essential for the production of these enzymes, and thus unraveling the signals and mechanisms involved in this regulation is a key step in understanding the environmental factors influencing virulence in Pectobacterium spp.

In a screen for regulators of RsmB, we isolated five mutants disrupted in the genes involved in the putative Trk potassium uptake system (trkH and trkA). We demonstrated that these mutants presented a reduced rsmB expression and that the Trk system is important for production of PCWDEs. These results led us to investigate the role of potassium in the expression of rsmB and virulence. We showed that intermediate concentrations of potassium (2.5 to 25 mM) were required to induce RsmB, but high potassium concentrations (250 mM) inhibited the expression of this regulatory RNA. The conclusion that potassium and Trk participate in RsmB regulation is further supported by the identification of another mutant isolated in our screen, which had the transposon inserted in the third gene of the annotated sapABCDF operon (RSV238) (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). This operon, in particular sapD, has been implicated in potassium transport via the Trk system in E. coli, as sapD mutants present no potassium uptake by the Trk system (27). It is thus possible that a transposon insertion in sapC also affects the Trk system.

Our analysis of the trk mutants showed that in P. wasabiae the Trk potassium system functions similarly to the E. coli Trk system. However, although in E. coli the Trk system seems to be important mainly at intermediate concentrations of potassium, in P. wasabiae this system appeared to be relevant in a broader range of potassium concentrations. In E. coli, an inducible high-affinity potassium system, the Kdp system, is the major system responsible for potassium uptake at concentrations lower than 5 mM (reviewed in reference 28), but in P. wasabiae the trk mutants had a strong growth defect at a low potassium concentration (2.5 mM) and did not even grow at 0.25 mM. These results showed that the Trk system is important at low potassium concentrations. This, together with the fact that we could not find any kdp-like gene in the genome of P. wasabiae, indicates that P. wasabiae, in contrast to E. coli, may lack a high-affinity potassium transporter and may rely solely on Trk at low potassium concentrations.

Our results showed that the Trk system regulated rsmB expression and provided strong support for the hypothesis that extracellular levels of potassium are important for virulence in P. wasabiae. Accordingly, we observed that extracellular potassium was required to fully induce maceration of plant tissue in WT bacteria and that this induction required an intact Trk system. Moreover, we observed that virulence was inhibited at high extracellular concentrations of potassium (250 mM). Importantly, this inhibition of virulence in WT bacteria at a concentration of 250 mM potassium is unlikely to be a consequence of growth inhibition because, at this potassium concentration in vitro, WT bacteria still grow better than the trkA mutant. In addition, despite its growth defect, the trkA mutant can cause almost as much tissue maceration with 250 mM potassium as the maximal levels observed with the WT strain (Fig. 4E and 5; see also Table S4 in the supplemental material). We also determined that the supplementation of a high concentration of potassium had no effect on the viability of the inoculum applied to the potato tubers in any of strains tested as shown in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material.

The mechanism by which the extracellular levels of potassium regulate rsmB expression via the Trk system is still unclear. As rsmB transcription is activated by the GacS/GacA system, we investigated whether the observed effects of potassium were also linked with or dependent upon the function of this two-component system. Although disruption of the gacA gene decreased the extent to which rsmB expression was induced, surprisingly potassium-dependent and Trk-dependent regulation was still observed in a gacA mutant. Two additional regulators in Pectobacterium spp., KdgR and RsmC, have been shown to repress RsmB expression (7, 29). However, disruption of these regulators had no effect on potassium-dependent regulation of rsmB expression (data not shown). These results provide evidence for additional players in the regulation of RsmB. The identity of such regulators could come from a genetic approach to isolate mutants that no longer respond to changes in extracellular levels of potassium. For example, it is possible that an additional two-component system is involved in such regulation. In fact, some transport systems have been associated with the activation of two-component systems (reviewed in reference 30). In E. coli, the DcuS/DcuR two-component system, which is activated by C4-carboxylates in the periplasm, is also regulated by the DcuB antiporter, which takes up C4-carboxylates. It has been proposed that, in the absence of C4-carboxylates, protein-protein interactions between DcuB and DcuS repress the autophosphorylation activity of the DcuS sensor kinase. Upon transport of these compounds, this repression is absent presumably because DcuB releases DcuS, which can then be activated by the periplasmic levels of C4-dicarboxylates (31). A similar interaction might happen between the Trk transport proteins and an unknown two-component system to regulate rsmB. Alternatively, it is possible that the observed regulation of rsmB is not responding to potassium flux through the Trk system but that it is instead sensitive to changes in intracellular potassium concentrations, as has been shown for the induction of biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis as a response to potassium leakage (32). In this case, it was proposed that in the presence of natural compounds that cause potassium leakage, the membrane kinase KinC responds to transient decreases in cytoplasmic potassium concentrations, activating a phosphorylation cascade that results in induction of exopolysaccharide production and biofilm formation.

The Trk system is widespread among bacteria, and it is the potassium transporter found in the largest number of species. This transport system is crucial for many of the intracellular functions of potassium, such as the maintenance of cell turgor pressure, the regulation of intracellular pH, adaptation to osmotic stress, and the function of many cytoplasmic enzymes that require potassium (reviewed in reference 28), but importantly it has also been implicated in the regulation of virulence in diverse bacteria. Trk mutants of Vibrio vulnificus, Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium, and Francisella tularensis are impaired in virulence; however, the molecular mechanisms involved in such regulation have not been identified (15, 33, 34). As both V. vulnificus and S. enterica also use homologues of the Rsm system (Csr) to regulate virulence, it is conceivable that Trk regulation of virulence in these organisms might also take place through the regulatory RNAs of the Csr system. Therefore, it is possible that the mechanisms identified here are conserved among the other pathogens that have the Gac/Rsm system. As the Gac/Rsm system has been shown to modulate carbon fluxes (10, 11), we propose that for bacteria that use the Trk transporter to regulate components of the Gac/Rsm pathway cells, we might benefit from coupling the information obtained from perceiving changes in potassium concentrations with the information on the metabolic state of the cell to modulate functions that go beyond maintaining the physiological functions of potassium to control activities that contribute to host colonization. For instance, when short-chain fatty acids accumulate during fermentation, bacterial cells typically use potassium transporters to manipulate intracellular potassium levels to cope with changes in cytoplasmic pH and to control turgor pressure (reviewed in reference 35). It is interesting that the Gac/Rsm homologue system in E. coli has been shown to respond under certain conditions to these weak organic acids (12), and thus, it is tempting to speculate that the link between the regulation of potassium transport and the regulation of the Gac/Rsm system might be related to the need to adapt to the presence of short-chain fatty acids. The benefit of regulating virulence in response to changes in potassium concentrations might also be related to the environmental changes typically experienced by pathogens during host invasion. For example, plant pathogens, such as P. wasabiae, are typically found in the soil, where potassium concentrations are in the 10 to 100 μM range, contrary to the 100 mM concentration found in eukaryotic cells (36). Hence, upon arrival of the bacteria to a wounded host, the local increased potassium concentration might provide a cue for the activation of the production of PCWDEs. The action of these enzymes will further disrupt the host cells with the consequent leakage of intracellular potassium, and the bacteria will have to adapt to the increasing potassium levels, which can ultimately reach the levels found inside the eukaryotic plant cells.

Crop losses resulting from bacterial diseases continue to cause significant agricultural and economic concerns. Understanding the regulatory networks responsible for the activation of virulence genes will help to define and improve control strategies that target this problem. The results presented here identify potassium as an important environmental factor in the regulation of virulence in the plant pathogen P. wasabiae and show that a reduction in WT virulence can be achieved by increasing the extracellular concentration of potassium (Fig. 5 and 6). Although additional work is required to fully characterize the molecular mechanisms behind the regulation of virulence by potassium via RsmB, our study highlights how potassium levels in the soil could affect the outcome of virulence in the plant pathogen P. wasabiae.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Joana Amaro for technical assistance and Jessica Thompson and Pol Nadal for helpful discussions. We are very grateful to Andres Mäe (Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology) for sharing protocols and strains and to Tapio Palva (University of Helsinki) for providing strains used in this study.

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.00569-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Põllumaa L, Alamäe T, Mäe A. 2012. Quorum sensing and expression of virulence in pectobacteria. Sensors 12:3327–3349. doi: 10.3390/s120303327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nykyri J, Niemi O, Koskinen P, Nokso-Koivisto J, Pasanen M, Broberg M, Plyusnin I, Törönen P, Holm L, Pirhonen M, Palva ET. 2012. Revised phylogeny and novel horizontally acquired virulence determinants of the model soft rot phytopathogen Pectobacterium wasabiae SCC3193. PLoS Pathog 8:e1003013. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pirhonen M, Flego D, Heikinheimo R, Palva ET. 1993. A small diffusible signal molecule is responsible for the global control of virulence and exoenzyme production in the plant pathogen Erwinia carotovora. EMBO J 12:2467–2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson RA, Eriksson AR, Heikinheimo R, Mäe A, Pirhonen M, Kõiv V, Hyytiäinen H, Tuikkala A, Palva ET. 2000. Quorum sensing in the plant pathogen Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora: the role of expR(Ecc). Mol Plant Microbe Interact 13:384–393. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.4.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sjöblom S, Brader G, Koch G, Palva ET. 2006. Cooperation of two distinct ExpR regulators controls quorum sensing specificity and virulence in the plant pathogen Erwinia carotovora. Mol Microbiol 60:1474–1489. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eriksson AR, Andersson RA, Pirhonen M, Palva ET. 1998. Two-component regulators involved in the global control of virulence in Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 11:743–752. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.8.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyytiäinen H, Montesano M, Palva ET. 2001. Global regulators ExpA (GacA) and KdgR modulate extracellular enzyme gene expression through the RsmA-rsmB system in Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 14:931–938. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.8.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bejerano-Sagie M, Xavier KB. 2007. The role of small RNAs in quorum sensing. Curr Opin Microbiol 10:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lapouge K, Schubert M, Allain FH-T, Haas D. 2008. Gac/Rsm signal transduction pathway of gamma-proteobacteria: from RNA recognition to regulation of social behaviour. Mol Microbiol 67:241–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeuchi K, Kiefer P, Reimmann C, Keel C, Dubuis C, Rolli J, Vorholt JA, Haas D. 2009. Small RNA-dependent expression of secondary metabolism is controlled by Krebs cycle function in Pseudomonas fluorescens. J Biol Chem 284:34976–34985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.052571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Septer AN, Bose JL, Lipzen A, Martin J, Whistler C, Stabb EV. 2014. Bright luminescence of Vibrio fischeri aconitase mutants reveals a connection between citrate and the Gac/Csr regulatory system. Mol Microbiol 95:283–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chavez RG, Alvarez AF, Romeo T, Georgellis D. 2010. The physiological stimulus for the BarA sensor kinase. J Bacteriol 192:2009–2012. doi: 10.1128/JB.01685-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawhon SD, Maurer R, Suyemoto M, Altier C. 2002. Intestinal short-chain fatty acids alter Salmonella Typhimurium invasion gene expression and virulence through BarA/SirA. Mol Microbiol 46:1451–1464. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pirhonen M, Palva ET. 1988. Occurrence of bacteriophage T4 receptor in Erwinia carotovora. Mol Gen Genet 214:170–172. doi: 10.1007/BF00340198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su J, Gong H, Lai J, Main A, Lu S. 2009. The potassium transporter Trk and external potassium modulate Salmonella enterica protein secretion and virulence. Infect Immun 77:667–675. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01027-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waters CM, Bassler BL. 2006. The Vibrio harveyi quorum-sensing system uses shared regulatory components to discriminate between multiple autoinducers. Genes Dev 20:2754–2767. doi: 10.1101/gad.1466506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy KC. 1998. Use of bacteriophage lambda recombination functions to promote gene replacement in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 180:2063–2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaniga K, Delor I, Cornelis GR. 1991. A wide-host-range suicide vector for improving reverse genetics in gram-negative bacteria: inactivation of the blaA gene of Yersinia enterocolitica. Gene 109:137–141. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90599-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Espéli O, Moulin L, Boccard F. 2001. Transcription attenuation associated with bacterial repetitive extragenic BIME elements. J Mol Biol 314:375–386. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherwood RT. 1966. Pectin lyase and polygalacturonase production by Rhizoctonia solani and other fungi. Phytopathology 56:279–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0434.1966.tb02264.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Toole GA, Pratt LA, Watnick PI, Newman DK, Weaver VB, Kolter R. 1999. Genetic approaches to study of biofilms. Methods Enzymol 310:91–109. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(99)10008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pratt LA, Kolter R. 1998. Genetic analysis of Escherichia coli biofilm formation: roles of flagella, motility, chemotaxis and type I pili. Mol Microbiol 30:285–293. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McMillan GP, Hedley D, Fyffe L, Pérombelon MCM. 1993. Potato resistance to soft-rot erwinias is related to cell wall pectin esterification. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 42:279–289. doi: 10.1006/pmpp.1993.1026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bossemeyer D, Borchard A, Dosch DC, Helmer GC, Epstein W, Booth IR, Bakker EP. 1989. K+-transport protein TrkA of Escherichia coli is a peripheral membrane protein that requires other trk gene products for attachment to the cytoplasmic membrane. J Biol Chem 264:16403–16410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harms C, Domoto Y, Celik C, Rahe E, Stumpe S, Schmid R, Nakamura T, Bakker EP. 2001. Identification of the ABC protein SapD as the subunit that confers ATP dependence to the K+-uptake systems Trk(H) and Trk(G) from Escherichia coli K-12. Microbiol Read Engl 147:2991–3003. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-11-2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Epstein W. 2003. The roles and regulation of potassium in bacteria. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 75:293–320. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(03)75008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kõiv V, Mäe A. 2001. Quorum sensing controls the synthesis of virulence factors by modulating rsmA gene expression in Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora. Mol Genet Genomics 265:287–292. doi: 10.1007/s004380000413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tetsch L, Jung K. 2009. The regulatory interplay between membrane-integrated sensors and transport proteins in bacteria. Mol Microbiol 73:982–991. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kleefeld A, Ackermann B, Bauer J, Krämer J, Unden G. 2009. The fumarate/succinate antiporter DcuB of Escherichia coli is a bifunctional protein with sites for regulation of DcuS-dependent gene expression. J Biol Chem 284:265–275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807856200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lopez D, Fischbach MA, Chu F, Losick R, Kolter R. 2009. Structurally diverse natural products that cause potassium leakage trigger multicellularity in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:280–285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810940106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen Y-C, Chuang Y-C, Chang C-C, Jeang C-L, Chang M-C. 2004. A K+ uptake protein, TrkA, is required for serum, protamine, and polymyxin B resistance in Vibrio vulnificus. Infect Immun 72:629–636. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.2.629-636.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alkhuder K, Meibom KL, Dubail I, Dupuis M, Charbit A. 2010. Identification of TrkH, encoding a potassium uptake protein required for Francisella tularensis systemic dissemination in mice. PLoS One 5:e8966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russell JB, Diez-Gonzalez F. 1998. The effects of fermentation acids on bacterial growth. Adv Microb Physiol 39:205–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dreyer I, Uozumi N. 2011. Potassium channels in plant cells. FEBS J 278:4293–4303. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.