ABSTRACT

Neisseria meningitidis, an exclusively human pathogen and the leading cause of bacterial meningitis, must adapt to different host niches during human infection. N. meningitidis can utilize a restricted range of carbon sources, including lactate, glucose, and pyruvate, whose concentrations vary in host niches. Microarray analysis of N. meningitidis grown in a chemically defined medium in the presence or absence of glucose allowed us to identify genes regulated by carbon source availability. Most such genes are implicated in energy metabolism and transport, and some are implicated in virulence. In particular, genes involved in glucose catabolism were upregulated, whereas genes involved in the tricarboxylic acid cycle were downregulated. Several genes encoding surface-exposed proteins, including the MafA adhesins and Neisseria surface protein A, were upregulated in the presence of glucose. Our microarray analysis led to the identification of a glucose-responsive hexR-like transcriptional regulator that controls genes of the central carbon metabolism of N. meningitidis in response to glucose. We characterized the HexR regulon and showed that the hexR gene is accountable for some of the glucose-responsive regulation; in vitro assays with the purified protein showed that HexR binds to the promoters of the central metabolic operons of the bacterium. Based on DNA sequence alignment of the target sites, we propose a 17-bp pseudopalindromic consensus HexR binding motif. Furthermore, N. meningitidis strains lacking hexR expression were deficient in establishing successful bacteremia in an infant rat model of infection, indicating the importance of this regulator for the survival of this pathogen in vivo.

IMPORTANCE Neisseria meningitidis grows on a limited range of nutrients during infection. We analyzed the gene expression of N. meningitidis in response to glucose, the main energy source available in human blood, and we found that glucose regulates many genes implicated in energy metabolism and nutrient transport, as well as some implicated in virulence. We identified and characterized a transcriptional regulator (HexR) that controls metabolic genes of N. meningitidis in response to glucose. We generated a mutant lacking HexR and found that the mutant was impaired in causing systemic infection in animal models. Since N. meningitidis lacks known bacterial regulators of energy metabolism, our findings suggest that HexR plays a major role in its biology by regulating metabolism in response to environmental signals.

INTRODUCTION

Neisseria meningitidis is a leading cause of meningitis and fulminant septicemia and is a significant public health problem, affecting mainly children and young adults. The annual number of invasive disease cases worldwide is estimated to be at least 1.2 million, with 135,000 deaths related to invasive meningococcal disease (1, 2). Meningococci are classified into 12 serogroups on the basis of the structure of the polysaccharide capsule; the majority of invasive meningococcal infections are caused by serogroups A, B, C, W, Y, and X (3).

N. meningitidis is an encapsulated Gram-negative diplococcal bacterium and a strictly human pathogen. It colonizes about 3 to 30% of the human population, where it resides asymptomatically in the nasopharynx, its only known reservoir (4). For reasons not yet fully understood, some strains of N. meningitidis are able to cross the mucosal epithelium and enter the bloodstream, where they evade immune killing by undergoing antigenic variation, by expressing surface antigens that mimic host molecules, and by recruiting human complement regulators (5–7). Furthermore, this pathogen can cross the blood-brain barrier and multiply in the cerebrospinal fluid, causing meningitis (8).

Meningococcal adaptation to the different human host niches also occurs at the level of the metabolism (9), and the acquisition of nutrients that enable the bacterium to sustain growth and to multiply rapidly, causing septicemia, is critical for the outcome of meningococcal disease. N. meningitidis is thus capable of adapting to different anatomical compartments of the host, including the nasopharyngeal mucosa, the bloodstream, and the subarachnoid compartment (10), where the available key nutrients, such as carbon sources, are diverse. Moreover, this bacterium can utilize a restricted variety of substrates, such as glucose, lactate, or pyruvate, as sole carbon sources to allow growth (11–13). Glucose is the predominant carbon source in blood and cerebrospinal fluid (14), the two main host niches of infection; therefore, glucose constitutes a crucial carbon source for N. meningitidis. Accordingly, about one-half of the genes that are essential for systemic infection encode enzymes that are involved in the metabolism and transport of nutrients (15). In addition, several environmental signals have effects on the transcriptional regulation of N. meningitidis during host infections, as shown for iron (16, 17), zinc (18), nitric oxide (19), human saliva (20), and human blood (21, 22). Therefore, virulence factors and genes essential for survival need to be regulated tightly and rapidly at the gene expression level in order to respond to the various microenvironments encountered during infection.

In this work, we assessed for the first time the effects of glucose on N. meningitidis at the transcriptional level. We observed that, besides an increase in energy metabolism through the Entner-Doudoroff (ED) pathway, there is upregulation of genes encoding surface-exposed proteins that have been implicated in adhesion and immune evasion, such as the MafA proteins and NspA (23, 24), respectively. Moreover, we identified an RpiR-like transcriptional regulator, HexR, that is responsible for part of the glucose-responsive regulation and that affects the fitness of this bacterium in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

N. meningitidis strains MC58 (25) and 2996 (26) (Table 1) were routinely cultured in GC medium-based agar (Difco) supplemented with Kellogg's supplement I (27). Liquid cultures were grown at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. For determination of growth curves, strains were grown to the stationary phase in GC medium-based medium with Kellogg's supplement I. For transcriptomic experiments, strains were grown to the mid-logarithmic phase in modified Catlin 6 (C6) medium (28). Because the concentration of glucose in human blood has been reported to be 4.5 mM (14), we decided to assay the effects of glucose on gene transcription in vitro by adding a 12-fold excess of glucose (55 mM) to the growth medium (1% [wt/vol]). Strains were stocked in GC medium with 15% glycerol and were stored at −80°C. When required, chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml), kanamycin (100 μg/ml), and/or isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (1 mM) were added to culture media at the indicated final concentrations. Escherichia coli DH5α (29) and BL21(DE3) (30) strains were grown in Luria-Bertani medium; when required, ampicillin and/or IPTG was added to achieve final concentrations of 100 μg/ml and 1 mM, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids and strains used in this study

| Plasmid or strain | Description | Antibiotic resistancea | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | |||

| pGEMT | Cloning vector | Amp | Promega |

| pGEMT-hexRKO::Kan | Plasmid for deletion of N. meningitidis hexR gene by homologous recombination | Amp, Kan | 31 |

| pGEMT-Pzwf | Plasmid harboring 321-bp promoter fragment upstream of zwf gene | Amp | This study |

| pGEMT-Pedd | Plasmid harboring 386-bp promoter fragment upstream of edd gene | Amp | This study |

| pET15b(+) | Plasmid for inducible expression of histidine-tagged recombinant proteins in E. coli | Amp | Life Technologies |

| pET15b(+)-hexR | Plasmid for expression and purification of histidine-tagged HexR in E. coli | Amp | This study |

| pComCmrPind | Plasmid for allelic replacement at chromosomal location between ORFs NMB1428 and NMB1429 and inducible expression under control of Ptac promoter and lacI repressor | Amp, Clm | 33 |

| pComCmrPind-hexR | Plasmid for complementation of ΔhexR null mutant; derivative of pComCmrPind containing copy of hexR gene | Amp, Clm | This study |

| Strains | |||

| MC58 | Laboratory-adapted N. meningitidis reference strain | 60 | |

| MC58 ΔhexR | MC58 derivative lacking hexR gene | Kan | 31 |

| MC58 ΔhexR c-hexR | MC58 derivative lacking hexR gene, with copy of hexR reintroduced out of locus under control of inducible Ptac promoter | Kan, Clm | This study |

| 2996 | Clinical isolate | 25 | |

| 2996 ΔhexR | 2996 derivative lacking hexR gene | Kan | This study |

Amp, ampicillin; Kan, kanamycin; Clm, chloramphenicol.

Construction of mutant and complemented strains.

DNA manipulations were carried out routinely as described for standard laboratory methods (31). N. meningitidis hexR mutants of the MC58 and 2996 strains were constructed as described previously (32). For complementation of the MC58 ΔhexR null mutant, the hexR gene under the control of the Ptac promoter and the lacI repressor was reinserted into the intergenic region between the converging open reading frames (ORFs) NMB1428 and NMB1429 by transformation with pComCmrPind-hexR (Table 1), a derivative plasmid of pSLComCmR (33) in which the hexR gene was amplified from the MC58 strain with the primers GG006 and GG007 (Table 2) and cloned as a 849-bp NdeI/NsiI fragment downstream of the Ptac promoter. This plasmid was transformed into the MC58 ΔhexR strain, and transformants were selected on chloramphenicol. All transformants were verified by PCR analysis for the correct insertion through a double homologous recombination event.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequencea | Restriction site | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| GG006 | ATATCATATGTTAAGCAAAATCAGCGAATCACTG | NdeI | hexR complementation |

| GG007 | ATATATGCATTCAATCTTTGTCGTAATCGATGTGC | NsiI | hexR complementation |

| GG012 | CTGTACTTCCAGGGCTTAAGCAAAATCAGCGAATCACTG | PIPE cloning of hexR | |

| GG013 | AATTAAGTCGCGTTAATCTTTGTCGTAATCGATGTGC | PIPE cloning of hexR | |

| GG034 | CTCGAGCGTCTGAAAGTGGGAAGCGG | XhoI | zwf promoter probe |

| GG035 | GGATCCGTACTCATCGTATTATCTCGTCAGG | BamHI | zwf promoter probe |

| GG036 | CTCGAGCCCCTATTCCGTTACAACAATCG | XhoI | edd promoter probe |

| GG037 | GGATCCTTCACGGTCGGTCTCCTGTC | BamHI | edd promoter probe |

| 0089RT-F | GAAACGATGCTGGTGGAAC | qRT-PCR | |

| 0089RT-R | CCGCTGGTAATGATGTATTGG | qRT-PCR | |

| 0207RT-F | TGACCAAATTCGACACCGT | qRT-PCR | |

| 0207RT-R | ATCGACACCGAGTTCTTTCC | qRT-PCR | |

| 0334RT-F | ATTTTGATTGACCGCCTCAC | qRT-PCR | |

| 0334RT-R | CACTGATCGAAGGGGTTGAC | qRT-PCR | |

| 0663RT-F | TATGCCGTTACCCCGAATGT | qRT-PCR | |

| 0663RT-R | CAGTGTTGACTTTGCCGATG | qRT-PCR | |

| 1389RT-F | ATGGTTTCCCGCCTCTTG | qRT-PCR | |

| 1389RT-R | CGATGTGCTTGTTGTGTATGCT | qRT-PCR | |

| 1392RT-F | AGCCTGTGAAAACCTTGCTG | qRT-PCR | |

| 1392RT-R | TTGATTTGCTGGGAAGAAGC | qRT-PCR | |

| 1393RT-F | TTGAAAAGCGAAATGGGTTC | qRT-PCR | |

| 1393RT-R | GGTGTAAGGGTGGACGAAGG | qRT-PCR | |

| 1476RT-F | ACGTTGCCATTTACAACGAA | qRT-PCR | |

| 1476RT-R | GTTCGGCGTTGGTAATTTCT | qRT-PCR | |

| 1710RT-F | GCAAATGAGTTCCGCCATC | qRT-PCR | |

| 1710RT-R | ATAGGCAGGGTGGTCAAGG | qRT-PCR | |

| 1968RT-F | TCAAACAAGGTGCGAAATTG | qRT-PCR | |

| 1968RT-R | CCATACTGTTGTCGGTGTCG | qRT-PCR | |

| 2159RT-F | GTTATCTCCGCCGCTTCCT | qRT-PCR | |

| 2159RT-R | GCTGTTGGGCACGATGTT | qRT-PCR | |

| 16SRT-F | ACGTAGGGTGCGAGCGTTAATC | qRT-PCR | |

| 16SRT-R | CTGCCTTCGCCATCGGTATTCCT | qRT-PCR |

Underlined letters indicate restriction enzyme sites.

RNA preparation.

Bacterial cultures were grown in liquid medium to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5 to 0.7 and then were added to an equal volume of frozen medium to bring the temperature immediately to 4°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3,400 × g for 20 min. In preparation for transcriptome experiments, total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen), following the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA was extracted from three independent bacterial cultures, and 15-μg aliquots of the samples were pooled. Three independent RNA pools were prepared for each condition tested.

Microarray procedures, hybridization, and analysis.

DNA microarray analysis was performed using Agilent custom-designed oligonucleotide arrays (34). cDNA probes were prepared from 5 μg of RNA pools and hybridized as described previously (34). Three hybridizations per experiment were performed, using cDNA probes from three independent pools, as detailed above. Changes in transcript levels were assessed by grouping all log2 ratios of the Cy5 and Cy3 values corresponding to each gene within experimental replicas and spot replicas and were filtered by comparing them against the zero value by Student's t test (one tailed). Validation of microarray results was performed by real-time quantitative (qRT)-PCR analysis of individual RNA samples unrelated to the microarray RNA pools, as detailed below.

Real-time quantitative PCR experiments.

For qRT-PCR experiments, 2 μg of total RNA treated with Turbo DNA-free DNase (Ambion) was reverse transcribed using random hexamer primers and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega), following the manufacturer's instructions. qRT-PCR assays were performed in triplicate on distinct RNA preparations, in 25-μl reaction mixtures containing 80 ng of cDNA, 1× Brilliant II SYBR green quantitative PCR master mixture (Agilent), and 0.2 μM gene-specific primers (Table 2). Amplification and detection of specific products were performed with a LightCycler 480 real-time PCR system (Roche), using the following procedure: 95°C for 10 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 30 s; and then dissociation curve analysis. The 16S rRNA gene was used as an internal reference for normalization, and relative transcript changes were determined by using the 2−ΔΔCT relative quantification method (35). Relative transcript changes for each gene were plotted with the standard deviation of the three replicates.

Expression and purification of recombinant HexR.

The hexR gene was amplified from the MC58 genome using primers GG012 and GG013 (Table 2) and was cloned as a 843-bp fragment into the pET15b(+) vector (Life Technologies) by using the polymerase-incomplete primer extension (PIPE) enzyme-free cloning method (36), generating the pET15b(+)-hexR plasmid (Table 1). This plasmid was transformed into the E. coli BL21(DE3) strain, the expression of a recombinant HexR protein containing an N-terminal histidine tag was induced by the addition of 1 mM IPTG and growth at 25°C for 6 h, and the protein was purified by Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) (Qiagen) affinity chromatography under nondenaturing conditions, according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, IPTG-induced E. coli cultures were concentrated in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 1 mg/ml chicken egg lysozyme) supplemented with complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and were incubated for 30 min at 4°C. Lysis was then performed by sonication, and cleared filtered supernatants were applied to the column for Ni-NTA affinity purification. After washing of the Ni-NTA resin with 12.5 volumes of wash buffer (20 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, 25 mM imidazole), the His-HexR protein was eluted with 2.5 volumes of elution buffer (20 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole). Eluted fractions were collected and pooled, and protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford colorimetric method (Bio-Rad). Pooled eluates were then dialyzed four times against 150 volumes of storage buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 10 to 50% glycerol); the concentration of glycerol was increased in a stepwise manner up to a final concentration of 50%.

DNase I footprinting.

The zwf and edd promoter regions were amplified with the primer pairs GG034/GG035 and GG036/GG037, respectively (Table 2). The PCR products were purified and cloned into the pGEMT vector (Promega) as 321-bp and 386-bp fragments, generating pGEMT-Pzwf and pGEMT-Pedd, respectively (Table 1). Two-picomole samples of each plasmid were end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP by T4 polynucleotide kinase, after digestion at either the XhoI or BamHI site introduced by PCR with the oligonucleotides described above. Following a second digestion with either BamHI or XhoI, the labeled probes were purified by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) as described previously (37). DNA-protein binding reactions were carried out for 15 min at room temperature in footprinting buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.05% Nonidet P-40) containing 60 fmol of labeled probe, 100 ng of salmon sperm DNA, and a range of HexR concentrations, as indicated (see Fig. 4B). Samples were then treated with 0.3 U of DNase I (Roche) for 2 min at room temperature. DNase I digestions were stopped and samples were purified, loaded, and run on 8 M urea-6% polyacrylamide gels as described previously (38). A G+A sequence reaction (39) was performed for each probe, in parallel with the footprinting reactions.

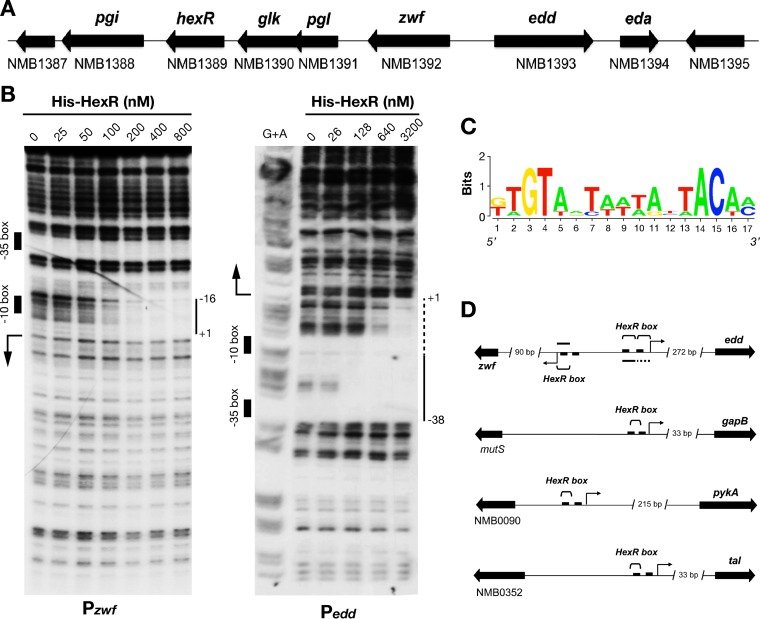

FIG 4.

Direct binding of HexR to the promoter regions of genes involved in central carbon metabolism. (A) Genetic organization of the hexR locus with respect to central carbon metabolism genes. (B) DNase I footprinting analysis of HexR binding to the zwf and edd promoter regions. Bars, regions protected against DNase I digestion by HexR; arrows, operon transcriptional start sites identified by total RNA sequencing experiments (data not shown); boxes, putative promoter elements. (C) HexR binding consensus sequence derived from mapped sites on the zwf and edd promoters (WebLogo 3.2). (D) Sequences matching the HexR binding consensus sequence found upstream of HexR-regulated operons (EMBOSS fuzznuc algorithm). Brackets, predicted HexR binding sequences overlapping putative promoter elements.

Bioinformatic analysis of the HexR binding site.

The HexR binding consensus sequence was derived by aligning the three 17-bp sites mapped on the zwf and edd promoters by DNase I footprinting. The sequence of each intergenic region from the MC58 strain genome was extracted and scanned in silico for the presence of HexR binding motifs, using the EMBOSS fuzznuc algorithm (A. Bleasby, European Bioinformatics Institute).

In vivo infant rat model.

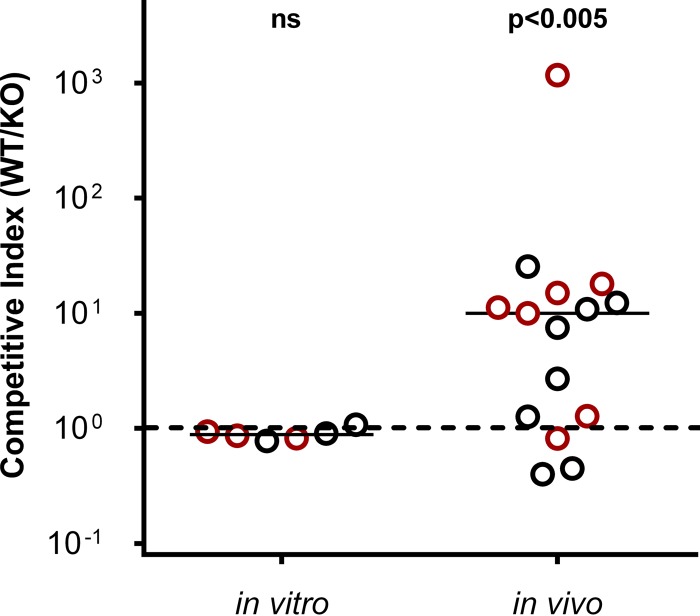

A competitive index (CI) assay was performed in infant rats to determine the in vivo fitness of the ΔhexR mutant strain, relative to the wild-type (WT) strain, as described by Fagnocchi and coworkers (32). N. meningitidis strain 2996 was used because it requires significantly smaller inocula (103 to 104 CFU) for infection than does the MC58 strain (108 CFU). Briefly, bacteria of N. meningitidis strain 2996 were grown to the mid-logarithmic phase in Mueller-Hinton medium supplemented with 0.25% (wt/vol) glucose and were diluted to the desired concentration in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Six- to 8-day-old pups from litters of outbred Wistar rats (Charles River) were challenged intraperitoneally with wild-type strain 2996 and the isogenic knockout mutant strains, at a 1:1 ratio, to establish mixed infections. Groups of infant rats were used for the infectious doses of 4.5 × 103 and 4.5 × 104 CFU. A control group of 9 infant rats was injected with PBS. Eighteen hours after the bacterial challenge, blood samples were obtained by cheek puncture and aliquots were plated for viable cell counting. In parallel, the experiment was reproduced in vitro by establishing mixed inocula of the wild-type and mutant strains, at a 1:1 ratio, with the same infectious doses as described above. The number of CFU per milliliter retrieved after each experiment was determined after overnight incubation at 37°C, in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, on Columbia agar supplemented with 5% horse blood, with or without kanamycin. Enumeration of wild-type bacteria and mutant bacteria allowed determination of the CI ratio using the following formula: CI = (WT output/mutant output)/(WT input/mutant input). Observed CIs for the two infectious doses followed the same statistical distribution and were pooled to increase the power of the analysis. Statistical significance was assessed with the Mann-Whitney test.

Ethics statement.

All animal trials were carried out in compliance with current Italian legislation on the care and use of animals in experimentation (legislative decree 116/92) and with Novartis animal welfare policies and standards. Protocols were approved by the Italian Ministry of Health (authorization no. DM 166/2012-B) and by the local Novartis animal welfare body (AWB) (research project AWB 201202). Following infection, animals were clinically monitored daily for criteria related to their feeding ability, reactivity, and motility, as well as cutaneous redness. After 18 h, all animals were alive and normally reactive and were euthanized by cervical dislocation, as preestablished in agreement with Novartis animal welfare policies.

RESULTS

Global analysis of Neisseria meningitidis gene expression in response to glucose.

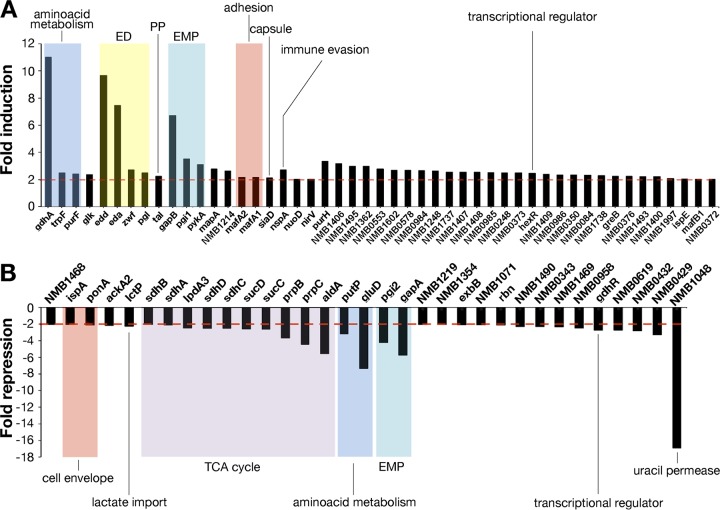

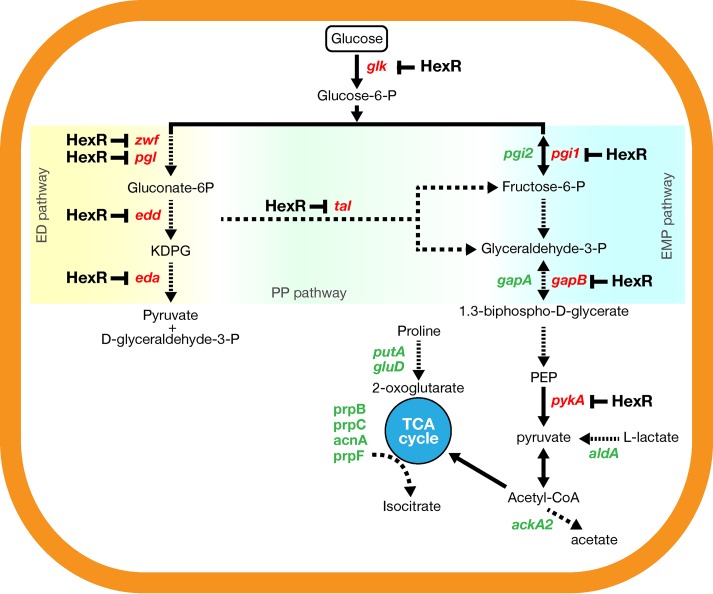

In order to investigate the effects of glucose on global transcripts in N. meningitidis, we compared the RNA profiles of bacteria grown to the exponential growth phase in the presence or absence of glucose, using custom Agilent oligonucleotide microarrays (34). The ratios of fluorescence values in the red and green channels corresponding to each gene were grouped and then filtered to select only genes that displayed the same changes in fluorescence across three independent replicates (P ≤ 0.05). A gene was defined as being differentially transcribed when it displayed >2-fold changes in fluorescence between the glucose samples and the reference samples (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Growth of the N. meningitidis MC58 strain in the presence of glucose altered the transcript levels of 82 genes (3.8% of the MC58 genome). Among these, transcript levels of 49 genes increased and transcript levels of 33 genes decreased; we proposed to refer to these sets of genes as upregulated and downregulated, respectively (Table 3). The global gene expression could be grouped into 13 functional protein categories, some of which are overrepresented, including energy metabolism (30%), hypothetical proteins (26%), transport and binding proteins (11%), and cell envelope (9%) (Table 3). Genes belonging to the Entner-Doudoroff (ED) pathway (zwf, pgl, edd, and eda), the pentose phosphate (PP) pathway (tal), and the catabolic branch of the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas (EMP) pathway (pgi1, gapB, and pykA) were found to be highly upregulated (Fig. 1; also see Table S1 in the supplemental material). In contrast, genes belonging to the anabolic branch of the EMP pathway (pgi2 and gapA) were found to be downregulated. Therefore, the presence of glucose upregulates genes that encode functions leading to glucose catabolism (glycolysis) and downregulates genes whose products catalyze the inverse reactions (gluconeogenesis), thus promoting the utilization of available sugar energy sources. We also observed downregulation of all genes involved in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (aldA, prpB, prpC, lpdA3, sdhABCD, and sucCD), as well as acetate production (ackA2). Genes related to amino acid metabolism and transport were also differentially expressed. The NADPH-specific glutamate dehydrogenase gene (gdhA) was upregulated, together with genes related to amino acid metabolism (trpF and purF). In contrast, the NADH-specific counterpart to gdhA (gluD) was downregulated, as was the proline importer gene (putP). Consistent with the availability of a carbon source such as glucose, the lactate importer gene (lctP) was downregulated, together with a gene encoding a putative uracil permease (NMB1048).

TABLE 3.

Numbers of genes differently expressed in the presence of glucose, grouped in functional categories according to the TIGR family classifications

| Functional category | No. of genes |

% of regulated genes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Downregulated | Upregulated | ||

| Amino acid biosynthesis | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Biosynthesis of cofactors, prosthetic groups, and carriers | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Cell envelope | 2 | 5 | 9 |

| Cellular processes | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Energy metabolism | 12 | 13 | 31 |

| Hypothetical proteins | 8 | 13 | 26 |

| Mobile element functions | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Protein fate | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Purines, pyrimidines, nucleosides, and nucleotides | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Regulatory functions | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Transcription | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Transport and binding proteins | 5 | 4 | 11 |

| Unknown function | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Total | 33 | 49 | 100 |

FIG 1.

Transcriptional profile of N. meningitidis strain MC58 in response to glucose. The relative ratios of the microarray competitive hybridizations are shown for glucose-responsive expression (MC58 with glucose versus MC58 without glucose). Differentially expressed genes, with P values of ≤0.05 and >2-fold induction (A) or >2-fold repression (B), are shown. ED, Entner-Doudoroff pathway; PP, pentose phosphate pathway; EMP, Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway; TCA, tricarboxylic acid.

In addition to metabolic changes, genes related to N. meningitidis pathogenesis were induced by glucose (Fig. 1; also see Table S1 in the supplemental material). For instance, nspA (encoding NspA, a factor H binding protein) was upregulated by glucose, as was the capsule gene NMB0067 (siaD). Furthermore, several genes coding for surface-exposed proteins that exhibit immunogenic properties and were proposed previously as vaccine candidates, such as NMB0390 and NMB1468, were upregulated and downregulated, respectively, in the presence of glucose. Genes coding for proteins involved in contact and interaction with the host were also differentially transcribed in the presence of glucose. The mafA (multiple adhesion family A) genes NMB0375 and NMB0652, encoding polymorphic glycolipid-binding lipoproteins implicated in adhesion (23), were upregulated by glucose. Interestingly, NMB1214, encoding the effector protein (HrpA) in a two-partner secretion system implicated in adhesion and intracellular survival (40), also was upregulated in the presence of glucose. Genes coding for proteins related to the cell envelope, such as NMB1807 (ponA, encoding penicillin-binding protein 1) and NMB0342 (ispA, encoding intracellular septation protein A), were downregulated in the presence of glucose. Interestingly, both of these genes have been found to be downregulated in glucose-rich human blood (22).

In order to confirm the results obtained in the microarray expression profiling, we selected a subset of 8 genes with changes ranging from highly upregulated to downregulated and we performed real-time quantitative (qRT)-PCR (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). The results obtained are similar to the microarray data, with a good coefficient of correlation (r2 = 0.82) (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material). Therefore, we conclude that glucose is involved in the control of gene expression related to metabolism and to functions relevant for N. meningitidis interactions with the host.

NMB1389, a HexR transcriptional regulator.

Searching the N. meningitidis genome for potential orthologues of the major bacterial carbon-source-responsive regulators, i.e., the cAMP receptor protein (Crp) and the catabolic repressor/activator protein (Cra) (41), we identified no orthologues of these regulators. In contrast, two potential carbon-related transcriptional regulators were differentially transcribed in response to glucose within the microarray data set; NMB1711 (gdhR) was downregulated by glucose and was described previously as being involved in the regulation of glutamate transport (42), and NMB1389 was upregulated in the presence of glucose (Fig. 1).

The NMB1389 gene encodes a protein with 41% amino acid identity and 58% amino acid similarity to the HexR protein of Pseudomonas putida (43). HexR-like transcriptional regulators from the RpiR family are often involved in sugar catabolism regulation in proteobacteria (43, 44). HexR contains two domains, namely, a helix-turn-helix (HTH) binding domain in the N-terminal region and a sugar isomerase (SIS) domain in the C-terminal region that is predicted to bind phosphosugars. In the gammaproteobacteria P. putida and Shewanella oneidensis, binding of the 2-dehydro-3-deoxyphosphogluconate (KDPG) metabolic intermediate of glycolysis was reported to dissociate HexR from its target DNA (43, 44). The NMB1389 (hexR) nucleotide sequence is highly conserved (>98%) among the available N. meningitidis genome sequences, and it is present in all species of the Neisseria genus, such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Neisseria lactamica, Neisseria cinerea, Neisseria flavescens, Neisseria mucosa, Neisseria sicca, and Neisseria subflava.

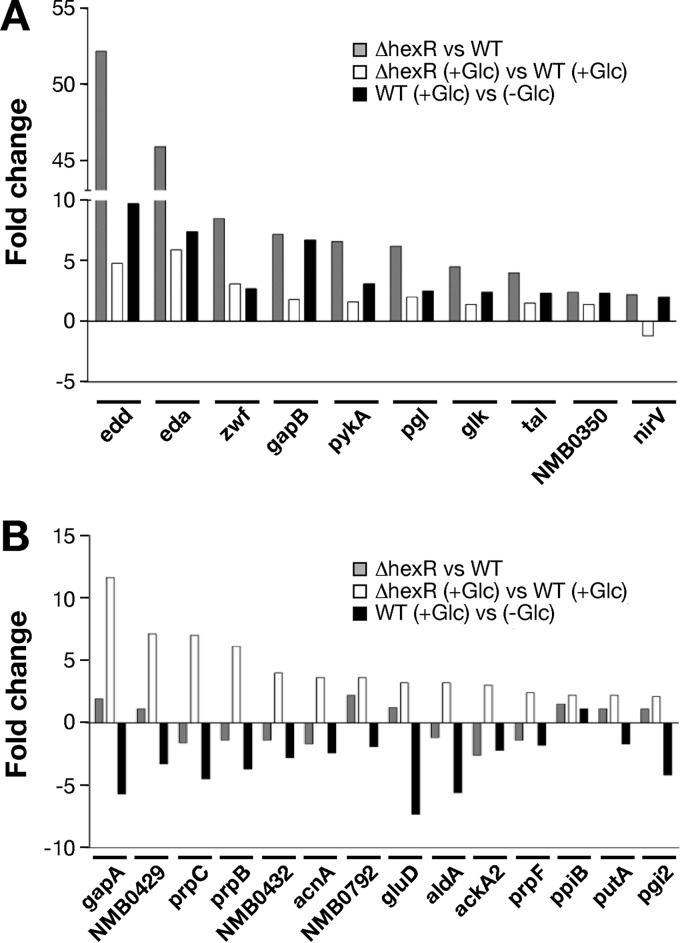

In order to assess the role of HexR in N. meningitidis carbon metabolism regulation, we generated a knockout ΔhexR strain and we performed microarray analysis of the wild-type MC58 strain and its isogenic ΔhexR mutant strain grown to the exponential growth phase in the presence or absence of glucose. In the absence of glucose in the growth medium, 23 genes showed changes in transcript levels in the ΔhexR strain versus the wild-type strain, with a 2-fold change threshold and t test P values of ≤0.05 (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). When the same strains were grown in the presence of glucose, hexR deletion altered transcript levels of 19 genes (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). Transcripts of 6 genes (zwf, edd, eda, hexR, ackA2, and NMB0792) were altered under both conditions, and consequently the deletion of hexR resulted in the upregulation or downregulation of 36 genes in total. Among these, upregulated genes were compared for their transcripts profiles under both conditions, as well as in our glucose data set (Fig. 2). Interestingly, all genes that were upregulated in the ΔhexR mutant in the absence of glucose displayed the same trend when the wild-type strain was exposed to glucose. This observation indicated that HexR repressed these genes in the absence of glucose and that HexR mediated the glucose-induced response in the transcription of these genes (Fig. 2A). In contrast, when bacteria were grown in the presence of glucose, the lack of hexR induced the upregulation of genes that were repressed by glucose in the wild-type strain (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, such regulation was lost when the strain lacking hexR was not exposed to glucose (Fig. 2B), indicating that glucose regulation of these genes is independent of HexR.

FIG 2.

Comparison of the relative ratios of microarray competitive hybridizations for hexR-dependent expression in the absence or presence of glucose (Glc), showing that HexR represses a variety of genes in response to glucose. The relative ratios for glucose-responsive expression in the WT strain are also shown. Only genes that were upregulated in the ΔhexR strain versus the WT strain, with >2-fold changes in the absence (A) versus the presence (B) of glucose, are shown.

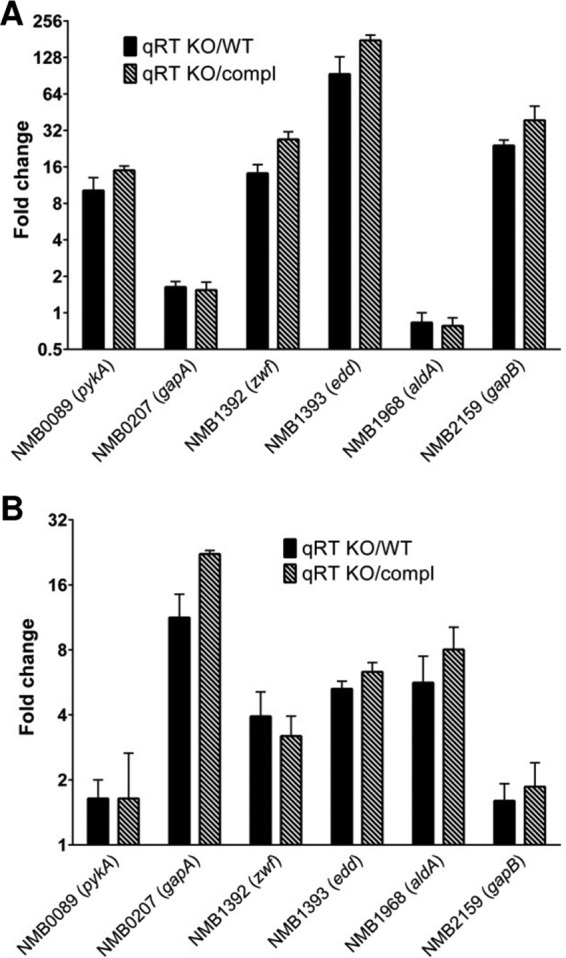

In order to validate the results obtained in the hexR microarray experiments, we selected 6 genes that showed different transcript levels under the two experimental conditions (C6 medium in the presence or absence of glucose), and we performed qRT-PCR analyses of RNA extracted from the ΔhexR and WT strains under those conditions. The results obtained were in agreement with the microarray data (see Fig. S1C and D in the supplemental material). We also performed a similar analysis comparing the ΔhexR strain with either the wild-type strain or the complemented c-hexR strain, in which expression of HexR had been induced with 1 mM IPTG. We observed similar trends and expression levels for the selected genes in the ΔhexR strain in comparison with the wild-type strain or the c-hexR strain (Fig. 3). In conclusion, these results confirm that expression of these genes is under the direct or indirect control of HexR.

FIG 3.

Comparison of qRT-PCR expression levels for 6 selected genes in the ΔhexR knockout (KO) strain versus the WT strain and in the ΔhexR strain versus the complemented (compl) strain, when grown in C6 medium in the absence (A) or presence (B) of glucose. Bars, fold changes for selected genes; error bars, standard deviations of three qRT-PCR biological replicates.

HexR binds to edd and zwf promoter regions.

The N. meningitidis hexR gene maps within a genomic region that includes genes of central carbohydrate metabolism (Fig. 4A). Because these genes showed different transcript levels in the ΔhexR mutant, we decided to investigate whether transcription could be regulated by HexR. Therefore, DNase I footprinting experiments were performed with the Pzwf and Pedd promoter probes to identify the binding sites of the HexR protein, with results shown in Fig. 4B. With increasing concentrations of recombinant HexR protein, we observed the appearance of defined protected areas. The presence of 100 nM HexR resulted in a partially protected region of the Pzwf probe, whose boundaries became clear with protein concentrations of ≥200 nM. The protected region spans position +1 to position −16 with respect to the transcriptional start site, thus overlapping the −10 promoter element. In a similar footprint experiment with the Pedd promoter probe, 128 nM HexR resulted in an area of DNase I protection, whose boundaries were extended with 640 and 3,200 nM protein. The protected region spans position −38 to position +1, thus overlapping the −35 promoter region with high affinity and the −10 region with low affinity. This region of protection likely is constituted by two adjacent HexR binding sites with different affinities (Fig. 3B).

In gammaproteobacteria, the KDPG metabolic intermediate of glycolysis was reported to abrogate the affinity of HexR for its target DNA (43, 44). Therefore, we tested several metabolic intermediates (KDPG, glucose-6-phosphate, fructose-1,6-biphosphate, and 6-phosphogluconic acid) as putative effectors for N. meningitidis HexR binding in vitro. However, we did not observe differences in the HexR binding affinity for its cognate targets in the presence of the tested molecules (data not shown). Differences in the amino acid sequence of the phosphosugar-binding C-terminal region of the protein may account for a still unknown HexR effector in response to glucose in N. meningitidis.

In silico prediction of N. meningitidis HexR DNA-binding consensus sequence.

From DNase I footprinting analysis, we identified three HexR binding sites. These sequences were used to grasp information on the HexR binding consensus sequence, identifying a 17-bp pseudopalindromic motif (KTGTANTWWWANTACAM) (Fig. 4C). This sequence resembles the HexR binding motif predicted in silico for betaproteobacteria in the RegPrecise database (45). We then used this motif to screen the N. meningitidis MC58 genome in silico and obtained 428 hits, among which 5 overlapped the promoter regions of HexR-regulated operons (Fig. 4D). Besides the central carbon metabolism genes zwf and edd (part of the ED pathway), the same motif was identified upstream of the gapB and pykA (part of the glycolytic branch of the EMP pathway) and tal (part of the pentose phosphate pathway) genes. We hypothesize that HexR regulates transcription of these genes through direct binding to their promoter regions.

HexR deletion impairs survival of N. meningitidis during in vivo infection.

In order to assess the viability of the ΔhexR mutant strain in vivo, a competitive index (CI) assay was performed with N. meningitidis strain 2996 in infant rats, to determine the fitness of the mutant relative to the wild-type strain, as described by Fagnocchi and coworkers (32). Growth curves in GC-rich medium as well as in C6 medium with and without glucose showed no significant differences for the ΔhexR mutant versus the wild-type strain (data not shown). The median CI observed for the challenged infant rats in the hexR experiment was >1, indicating that more wild-type bacteria (approximately 10-fold more) survived in the animal model than did ΔhexR mutant bacteria (Fig. 5). When the same competition assay was performed under in vitro conditions, no difference in survival was observed between wild-type and mutant bacteria (Fig. 5). This suggests that the lack of HexR expression significantly affects the survival of N. meningitidis during in vivo infection.

FIG 5.

Deletion of hexR impairs survival during infection in vivo. Individual competitive index (CI) values from in vitro growth assays or intraperitoneal challenge of infant rats (in vivo) with N. meningitidis WT and ΔhexR knockout (KO) strains in a 1:1 ratio are shown. Circles, individual samples. Two infectious doses were used, i.e., 4.5 × 103 CFU (red) and 4.5 × 104 CFU (black). Solid line, median; dashed line, CI of 1. A CI of >1 indicates that the WT strain is more competitive than the mutant. CIs observed with the two infectious doses followed the same statistical distribution and were pooled to increase the power of the analysis. Statistical significance was assessed with the Mann-Whitney test. ns, not significant.

DISCUSSION

The ability of microorganisms to detect and to respond to variable external conditions, such as environmental stress and the availability of carbon sources in different niches, requires a coordination of sensing mechanisms and regulatory circuits (46) and often is crucial for the adaptation of pathogenic bacteria to the host environment. Here we show the transcriptional profile of N. meningitidis in response to glucose, one of the main carbon sources that the bacterium encounters in its different niches of colonization. Glucose induces the differential expression of a large number of genes; interestingly, some of them are found to have the same trend of regulation in response to human blood (21), where glucose is abundant. In N. meningitidis, glucose is metabolized mainly through the Entner-Doudoroff (ED) pathway and to a lesser extent through the pentose phosphate (PP) pathway (47, 48), while the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas (EMP) pathway is not fully functional, because it lacks the phosphofructokinase gene (49). Similarly, in P. putida the ED pathway synthesizes the major part of the pyruvate (67 to 87%) and the PP pathway accounts for the remaining part (50). Accordingly, N. meningitidis microarray analysis revealed that genes driving glucose catabolism through these pathways (glk, zwf, edd, eda, pgl, pgi1, gapB, and pykA) were highly upregulated by the presence of glucose (Fig. 6). In contrast, genes from the gluconeogenesis pathway (pgi2 and gapA) were downregulated in the presence of glucose (Fig. 6). This can have physiologically relevant consequences, since gapA was shown to play a role in adhesion (51) and its expression is controlled by the NadR repressor (20). Furthermore, the acetate kinase gene ackA2, which is involved in the production of acetate from acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), was downregulated by glucose (Fig. 6). Since the catabolism of glucose results in the accumulation of acetate, a feedback effect of an acetate surplus could explain this observation. Similarly, other pathways that would be directly affected by an overabundance of acetyl-CoA, such as the TCA cycle enzymes encoded by prpB, prpC, lpdA3, sdhABCD, and sucCD, were found to be repressed in the presence of glucose (Fig. 6). Indeed, growth on glucose has been reported to reduce the levels of TCA cycle enzymes also in gonococci (52, 53). Interestingly, the glucose-repressed genes encoding the TCA cycle enzymes were also repressed in glucose-rich human blood (21, 22) and, in a recent report, the TCA cycle prp operon was suggested to help N. meningitidis in the colonization of the propionate-rich and glucose-poor oral cavities of adults (54). Also, the NADH-specific glutamate dehydrogenase gene gludD was found to be repressed in the presence of glucose, as was the putP-putA operon, which is involved in glutamate degradation and proline utilization. This suggests an interconnection between carbon catabolism and nitrogen metabolism in response to carbon source availability. In contrast, NADPH-specific gdhA was upregulated by glucose. High-level expression of gdhA is dependent on ammonia assimilation from the TCA cycle intermediate 2-oxoglutarate and may result in growth advantages when the glucose concentration is higher than that of lactate (55), such as in human whole blood, where gdhA has been found to be upregulated (21).

FIG 6.

Model of glucose- and HexR-mediated regulation in N. meningitidis, showing the main metabolic pathways affected by glucose availability. Genes that are significantly upregulated (red) and downregulated (green) by glucose are shown. Genes subject to glucose-responsive HexR repression are highlighted. ED, Entner-Doudoroff; PP, pentose phosphate; EMP, Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas; TCA, tricarboxylic acid; P, phosphate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate.

Overall, we observed that the N. meningitidis response to glucose modulates a large number of genes, compared to the responses to other environmental signals, such as zinc (17 genes [18]), iron (83 genes [16, 17]), or lactate (23 genes [data not shown]). Furthermore, 11 genes that were found to be differentially expressed in the presence of glucose showed similar patterns of expression when N. meningitidis was exposed to lactate (data not shown), suggesting that these genes respond to the availability of a carbon source rather than to the type of sugar added. Most of these genes encode hypothetical proteins but also proteins related to the cell envelope, such as NMB0342 (ispA), NMB1729 (exbB), and NMB0543 (lctP).

This study identified an RpiR family HexR regulator controlling the central carbon metabolism of N. meningitidis in response to glucose (Fig. 6). Although only 28% of the total glucose-regulated genes in N. meningitidis are also controlled by HexR, this regulator controls the majority (60%) of the glucose-regulated genes belonging to the functional category of energy metabolism. The number of genes differentially expressed in a ΔhexR mutant strain of N. meningitidis is similar to values reported for other proteobacteria (44). In other species, members of this family can be repressors such as RpiR in Escherichia coli (56), transcriptional activators like GlvR of Bacillus subtilis, which modulates maltose metabolism (57), or dual-purpose transcriptional factors like HexR in P. putida (43), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (58), and S. oneidensis (44). The N. meningitidis HexR acts as a repressor by binding specific DNA sequences within the promoters of its target genes, albeit with different affinities. In our DNA-protein footprinting experiments, we identified a 100 nM HexR affinity site in the zwf promoter and a site with similar affinity (128 nM) in the edd promoter, while a second site within the edd promoter required 640 nM HexR for protection. Similar results were obtained in P. putida, where 100 nM to 3 μM HexR was necessary to bind to the operators within the zwf and edd/gap-1 promoter regions in DNA footprinting (43). Interestingly, in the transcriptome data, the fold change for edd, containing two HexR operators, was almost double that for zwf, for which only one operator was identified. Overall, our in vitro data agree with findings reported for HexR in other proteobacterial species, where it directly regulates the transcription of central carbon metabolism genes (44). Furthermore, the HexR binding DNA consensus sequences are very similar for N. meningitidis, P. putida, and Shewanella spp., and common HexR-responsive genes are found among these species (43).

Our results show that HexR not only controls the expression of genes from central carbon metabolism but also regulates genes involved in nitrogen metabolism, redox potential, and denitrification, therefore suggesting that HexR may play an important role in connecting these major pathways in responses to environmental adaptation. In E. coli, expression of the enzymes in the ED pathway is essential for colonization of the gastrointestinal tract (59); in P. putida, the ED pathway plays an important role in the generation of redox currency, which is required to counteract oxidative stress (60). Similarly, a meningococcal strain lacking hexR showed reduced fitness during in vivo infection, which indicates the importance of this transcriptional regulator not only in metabolic adaptation but also in the survival of N. meningitidis within the host. It would be interesting to investigate the steps of infection, such as adhesion, colonization, and/or multiplication, during which HexR is mostly expressed in vivo and therefore regulating its targets.

It is interesting to note that, although N. meningitidis inhabits different niches in the host (such as the nasopharynx, blood, and meninges), where nutrient availability is very diverse, it uses a restricted range of carbon sources, does not have a complete EMP pathway for carbon metabolism, and has no equivalent to known global carbon catabolite regulators. This means that N. meningitidis does not follow the same paradigm of carbon catabolite repression as reported for enterobacteria or Gram-positive low-G+C bacteria and that HexR plays a major role in the biology of N. meningitidis by regulating its central carbon metabolism in response to environmental signals. However, we have also shown that not all glucose-responsive genes are regulated through HexR (e.g., nspA), suggesting that other mechanisms, either transcriptional or posttranscriptional, could affect gene expression in response to glucose.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Scilla Buccato for help with the PIPE cloning method, Fabio Rigat for help with statistical analyses, Giorgio Corsi for the artwork, and the animal care facility at GSK Vaccines for technical assistance.

Ana Antunes is the recipient of a research grant from the European Community Seventh Framework Program (EIMID-IAAP grant PIAP-GA-2008-217768). Giacomo Golfieri is the recipient of a graduate student fellowship from the University of Bologna.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.00659-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rouphael NG, Stephens DS. 2012. Neisseria meningitidis: biology, microbiology, and epidemiology. Methods Mol Biol 799:1–20. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-346-2_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang Q, Tzeng YL, Stephens DS. 2012. Meningococcal disease: changes in epidemiology and prevention. Clin Epidemiol 4:237–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenstein NE, Perkins BA, Stephens DS, Popovic T, Hughes JM. 2001. Meningococcal disease. N Engl J Med 344:1378–1388. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caugant DA, Maiden MC. 2009. Meningococcal carriage and disease: population biology and evolution. Vaccine 27(Suppl 2):B64–B70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill DJ, Griffiths NJ, Borodina E, Virji M. 2010. Cellular and molecular biology of Neisseria meningitidis colonization and invasive disease. Clin Sci 118:547–564. doi: 10.1042/CS20090513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer TF. 1991. Evasion mechanisms of pathogenic neisseriae. Behring Inst Mitt (88):194–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider MC, Exley RM, Ram S, Sim RB, Tang CM. 2007. Interactions between Neisseria meningitidis and the complement system. Trends Microbiol 15:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Virji M. 2009. Pathogenic neisseriae: surface modulation, pathogenesis and infection control. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:274–286. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Exley RM, Shaw J, Mowe E, Sun YH, West NP, Williamson M, Botto M, Smith H, Tang CM. 2005. Available carbon source influences the resistance of Neisseria meningitidis against complement. J Exp Med 201:1637–1645. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nassif X, Bourdoulous S, Eugene E, Couraud PO. 2002. How do extracellular pathogens cross the blood-brain barrier? Trends Microbiol 10:227–232. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(02)02349-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leighton MP, Kelly DJ, Williamson MP, Shaw JG. 2001. An NMR and enzyme study of the carbon metabolism of Neisseria meningitidis. Microbiology 147:1473–1482. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-6-1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith H, Tang CM, Exley RM. 2007. Effect of host lactate on gonococci and meningococci: new concepts on the role of metabolites in pathogenicity. Infect Immun 75:4190–4198. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00117-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baart GJ, Zomer B, de Haan A, van der Pol LA, Beuvery EC, Tramper J, Martens DE. 2007. Modeling Neisseria meningitidis metabolism: from genome to metabolic fluxes. Genome Biol 8:R136. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-7-r136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith H, Yates EA, Cole JA, Parsons NJ. 2001. Lactate stimulation of gonococcal metabolism in media containing glucose: mechanism, impact on pathogenicity, and wider implications for other pathogens. Infect Immun 69:6565–6572. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.11.6565-6572.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun YH, Bakshi S, Chalmers R, Tang CM. 2000. Functional genomics of Neisseria meningitidis pathogenesis. Nat Med 6:1269–1273. doi: 10.1038/81380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delany I, Grifantini R, Bartolini E, Rappuoli R, Scarlato V. 2006. Effect of Neisseria meningitidis fur mutations on global control of gene transcription. J Bacteriol 188:2483–2492. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.7.2483-2492.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grifantini R, Sebastian S, Frigimelica E, Draghi M, Bartolini E, Muzzi A, Rappuoli R, Grandi G, Genco CA. 2003. Identification of iron-activated and -repressed Fur-dependent genes by transcriptome analysis of Neisseria meningitidis group B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:9542–9547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1033001100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pawlik MC, Hubert K, Joseph B, Claus H, Schoen C, Vogel U. 2012. The zinc-responsive regulon of Neisseria meningitidis comprises 17 genes under control of a Zur element. J Bacteriol 194:6594–6603. doi: 10.1128/JB.01091-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heurlier K, Thomson MJ, Aziz N, Moir JW. 2008. The nitric oxide (NO)-sensing repressor NsrR of Neisseria meningitidis has a compact regulon of genes involved in NO synthesis and detoxification. J Bacteriol 190:2488–2495. doi: 10.1128/JB.01869-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fagnocchi L, Pigozzi E, Scarlato V, Delany I. 2012. In the NadR regulon, adhesins and diverse meningococcal functions are regulated in response to signals in human saliva. J Bacteriol 194:460–474. doi: 10.1128/JB.06161-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Echenique-Rivera H, Muzzi A, Del Tordello E, Seib KL, Francois P, Rappuoli R, Pizza M, Serruto D. 2011. Transcriptome analysis of Neisseria meningitidis in human whole blood and mutagenesis studies identify virulence factors involved in blood survival. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002027. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hedman AK, Li MS, Langford PR, Kroll JS. 2012. Transcriptional profiling of serogroup B Neisseria meningitidis growing in human blood: an approach to vaccine antigen discovery. PLoS One 7:e39718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paruchuri DK, Seifert HS, Ajioka RS, Karlsson KA, So M. 1990. Identification and characterization of a Neisseria gonorrhoeae gene encoding a glycolipid-binding adhesin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87:333–337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis LA, Carter M, Ram S. 2012. The relative roles of factor H binding protein, neisserial surface protein A, and lipooligosaccharide sialylation in regulation of the alternative pathway of complement on meningococci. J Immunol 188:5063–5072. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tettelin H, Saunders NJ, Heidelberg J, Jeffries AC, Nelson KE, Eisen JA, Ketchum KA, Hood DW, Peden JF, Dodson RJ, Nelson WC, Gwinn ML, DeBoy R, Peterson JD, Hickey EK, Haft DH, Salzberg SL, White O, Fleischmann RD, Dougherty BA, Mason T, Ciecko A, Parksey DS, Blair E, Cittone H, Clark EB, Cotton MD, Utterback TR, Khouri H, Qin H, Vamathevan J, Gill J, Scarlato V, Masignani V, Pizza M, Grandi G, Sun L, Smith HO, Fraser CM, Moxon ER, Rappuoli R, Venter JC. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B strain MC58. Science 287:1809–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Comanducci M, Bambini S, Brunelli B, Adu-Bobie J, Arico B, Capecchi B, Giuliani MM, Masignani V, Santini L, Savino S, Granoff DM, Caugant DA, Pizza M, Rappuoli R, Mora M. 2002. NadA, a novel vaccine candidate of Neisseria meningitidis. J Exp Med 195:1445–1454. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kellogg DS Jr, Peacock WL Jr, Deacon WE, Brown L, Pirkle DI. 1963. Neisseria gonorrhoeae. I. Virulence genetically linked to clonal variation. J Bacteriol 85:1274–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koeberling O, Delany I, Granoff DM. 2011. A critical threshold of meningococcal factor H binding protein expression is required for increased breadth of protective antibodies elicited by native outer membrane vesicle vaccines. Clin Vaccine Immunol 18:736–742. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00542-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanahan D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol 166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Studier FW, Moffatt BA. 1986. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J Mol Biol 189:113–130. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fagnocchi L, Bottini S, Golfieri G, Fantappie L, Ferlicca F, Antunes A, Guadagnuolo S, Del Tordello E, Siena E, Serruto D, Scarlato V, Muzzi A, Delany I. 2015. Global transcriptome analysis reveals small RNAs affecting Neisseria meningitidis bacteremia. PLoS One 10:e0126325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ieva R, Alaimo C, Delany I, Spohn G, Rappuoli R, Scarlato V. 2005. CrgA is an inducible LysR-type regulator of Neisseria meningitidis, acting both as a repressor and as an activator of gene transcription. J Bacteriol 187:3421–3430. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.10.3421-3430.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fantappie L, Oriente F, Muzzi A, Serruto D, Scarlato V, Delany I. 2011. A novel Hfq-dependent sRNA that is under FNR control and is synthesized in oxygen limitation in Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol 80:507–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klock HE, Lesley SA. 2009. The polymerase incomplete primer extension (PIPE) method applied to high-throughput cloning and site-directed mutagenesis. Methods Mol Biol 498:91–103. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-196-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Metruccio MM, Pigozzi E, Roncarati D, Berlanda Scorza F, Norais N, Hill SA, Scarlato V, Delany I. 2009. A novel phase variation mechanism in the meningococcus driven by a ligand-responsive repressor and differential spacing of distal promoter elements. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000710. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delany I, Spohn G, Rappuoli R, Scarlato V. 2001. The Fur repressor controls transcription of iron-activated and -repressed genes in Helicobacter pylori. Mol Microbiol 42:1297–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maxam AM, Gilbert W. 1977. A new method for sequencing DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 74:560–564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.2.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tala A, Progida C, De Stefano M, Cogli L, Spinosa MR, Bucci C, Alifano P. 2008. The HrpB-HrpA two-partner secretion system is essential for intracellular survival of Neisseria meningitidis. Cell Microbiol 10:2461–2482. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gorke B, Stulke J. 2008. Carbon catabolite repression in bacteria: many ways to make the most out of nutrients. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:613–624. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pagliarulo C, Salvatore P, De Vitis LR, Colicchio R, Monaco C, Tredici M, Tala A, Bardaro M, Lavitola A, Bruni CB, Alifano P. 2004. Regulation and differential expression of gdhA encoding NADP-specific glutamate dehydrogenase in Neisseria meningitidis clinical isolates. Mol Microbiol 51:1757–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2003.03947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daddaoua A, Krell T, Ramos JL. 2009. Regulation of glucose metabolism in Pseudomonas: the phosphorylative branch and Entner-Doudoroff enzymes are regulated by a repressor containing a sugar isomerase domain. J Biol Chem 284:21360–21368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.014555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leyn SA, Li X, Zheng Q, Novichkov PS, Reed S, Romine MF, Fredrickson JK, Yang C, Osterman AL, Rodionov DA. 2011. Control of proteobacterial central carbon metabolism by the HexR transcriptional regulator: a case study in Shewanella oneidensis. J Biol Chem 286:35782–35794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.267963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Novichkov PS, Laikova ON, Novichkova ES, Gelfand MS, Arkin AP, Dubchak I, Rodionov DA. 2010. RegPrecise: a database of curated genomic inferences of transcriptional regulatory interactions in prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res 38:D111–D118. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chubukov V, Gerosa L, Kochanowski K, Sauer U. 2014. Coordination of microbial metabolism. Nat Rev Microbiol 12:327–340. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holten E. 1974. Glucokinase and glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase in Neisseria. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand B Microbiol Immunol 82:201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holten E, Jyssum K. 1974. Activities of some enzymes concerning pyruvate metabolism in Neisseria. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand B Microbiol Immunol 82:843–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baart GJ, Langenhof M, van de Waterbeemd B, Hamstra HJ, Zomer B, van der Pol LA, Beuvery EC, Tramper J, Martens DE. 2010. Expression of phosphofructokinase in Neisseria meningitidis. Microbiology 156:530–542. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.031641-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.del Castillo T, Ramos JL, Rodriguez-Herva JJ, Fuhrer T, Sauer U, Duque E. 2007. Convergent peripheral pathways catalyze initial glucose catabolism in Pseudomonas putida: genomic and flux analysis. J Bacteriol 189:5142–5152. doi: 10.1128/JB.00203-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tunio SA, Oldfield NJ, Ala'Aldeen DA, Wooldridge KG, Turner DP. 2010. The role of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GapA-1) in Neisseria meningitidis adherence to human cells. BMC Microbiol 10:280. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hebeler BH, Morse SA. 1976. Physiology and metabolism of pathogenic Neisseria: tricarboxylic acid cycle activity in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Bacteriol 128:192–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morse SA, Hebeler BH. 1978. Effect of pH on the growth and glucose metabolism of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun 21:87–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Catenazzi MC, Jones H, Wallace I, Clifton J, Chong JP, Jackson MA, Macdonald S, Edwards J, Moir JW. 2014. A large genomic island allows Neisseria meningitidis to utilize propionic acid, with implications for colonization of the human nasopharynx. Mol Microbiol 93:346–355. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schoen C, Kischkies L, Elias J, Ampattu BJ. 2014. Metabolism and virulence in Neisseria meningitidis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 4:114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sorensen KI, Hove-Jensen B. 1996. Ribose catabolism of Escherichia coli: characterization of the rpiB gene encoding ribose phosphate isomerase B and of the rpiR gene, which is involved in regulation of rpiB expression. J Bacteriol 178:1003–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamamoto H, Serizawa M, Thompson J, Sekiguchi J. 2001. Regulation of the glv operon in Bacillus subtilis: YfiA (GlvR) is a positive regulator of the operon that is repressed through CcpA and cre. J Bacteriol 183:5110–5121. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.17.5110-5121.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hager PW, Calfee MW, Phibbs PV. 2000. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa devB/SOL homolog, pgl, is a member of the hex regulon and encodes 6-phosphogluconolactonase. J Bacteriol 182:3934–3941. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.14.3934-3941.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chang DE, Smalley DJ, Tucker DL, Leatham MP, Norris WE, Stevenson SJ, Anderson AB, Grissom JE, Laux DC, Cohen PS, Conway T. 2004. Carbon nutrition of Escherichia coli in the mouse intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:7427–7432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307888101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chavarria M, Fuhrer T, Sauer U, Pfluger-Grau K, de Lorenzo V. 2013. Cra regulates the cross-talk between the two branches of the phosphoenolpyruvate:phosphotransferase system of Pseudomonas putida. Environ Microbiol 15:121–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.