Abstract

The synergistic antimicrobial effects of phytic acid (PA), a natural extract from rice bran, plus sodium chloride against Escherichia coli O157:H7 were examined. Exposure to NaCl alone at concentrations up to 36% (wt/wt) for 5 min did not reduce bacterial populations. The bactericidal effects of PA alone were much greater than those of other organic acids (acetic, citric, lactic, and malic acids) under the same experimental conditions (P < 0.05). Combining PA and NaCl under conditions that yielded negligible effects when each was used alone led to marked synergistic effects. For example, whereas 0.4% PA or 3 or 4% NaCl alone had little or no effect on cell viability, combining the two completely inactivated both nonadapted and acid-adapted cells, reducing their numbers to unrecoverable levels (>7-log CFU/ml reduction). Flow cytometry confirmed that PA disrupted the cell membrane to a greater extent than did other organic acids, although the cells remained viable. The combination of PA and NaCl induced complete disintegration of the cell membrane. By comparison, none of the other organic acids acted synergistically with NaCl, and neither did NaCl-HCl solutions at the same pH values as the test solutions of PA plus NaCl. These results suggest that PA has great potential as an effective bacterial membrane-permeabilizing agent, and we show that the combination is a promising alternative to conventional chemical disinfectants. These findings provide new insight into the utility of natural compounds as novel antimicrobial agents and increase our understanding of the mechanisms underlying the antibacterial activity of PA.

INTRODUCTION

Food safety has become an increasingly important aspect of public health. According to the World Health Organization, foodborne and waterborne diarrheal diseases kill an estimated 2 million people per year, many of whom are children (1). Although various chemicals are used to control the transmission of foodborne illnesses via the food and livestock industries (2, 3), several studies have suggested that synthetic sanitizers can have significant side effects (e.g., bleaching, formation of toxic compounds, and off odors) (4, 5). Because modern consumers tend to prefer the use of “natural” agents rather than “synthetic” ones (6), new antimicrobial agents are required; therefore, studies of natural compounds with antimicrobial actions are warranted.

Organic acids are a class of such natural antimicrobial agents. Several organic acids (particularly acetic, citric, and lactic acids) have long been used as preservatives or surface sanitizers for beef hides (7), carcasses (8), dairy products (9, 10), fresh-cut vegetables (11), and meat products (12). However, organic acids alone are not powerful enough to inactivate pathogenic bacteria after only a short exposure time (5, 13). Even if this problem could be overcome, applying adequate amounts of organic acids is impractical, because they generate strong acidic odors at working concentrations (5, 13). Thus, it is of vital importance to identify new alternatives or to develop alternative strategies to overcome barriers to the effective use of natural compounds.

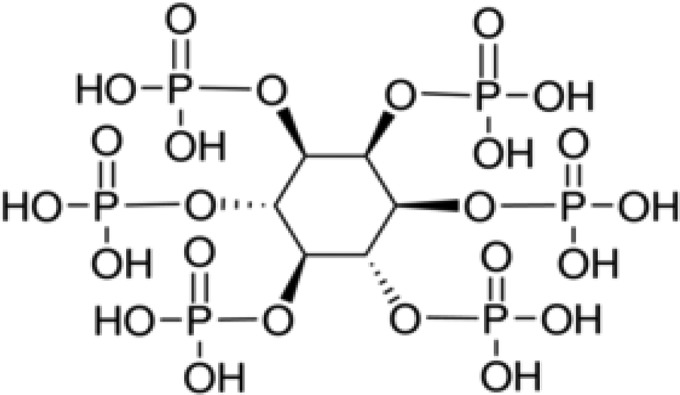

Phytic acid (PA) (2,3,4,5,6-pentaphosphonooxycyclohexyl dihydrogen phosphate) is used by many grain and cereal plants as a source of stored phosphorous, where it represents 1 to 9% of dry weight (14). Several recent studies reported that PA has beneficial effects on human health through its antioxidant (15), anticancer (16), and antidiabetic (17) effects. It can also protect against the development of Parkinson's disease (18) and renal calculi (19). However, PA has not been widely studied as a natural antimicrobial agent. The mechanism by which organic acids exert their antimicrobial activity is generally explained by the weak acid theory, i.e., only undissociated forms of the acid can enter the cytoplasm, where they inactivate bacteria by gradually dissociating into charged ions that disrupt cytoplasmic pH homeostasis (20). The mechanism underlying the antimicrobial properties of PA is likely to be quite different from that of other organic acids, because PA has a unique structure (12 replaceable protons on six reactive phosphate groups bonded to a cyclic six-carbon ring, i.e., C6H18O24P6) (Fig. 1) and a wide acidity range (pKa of 1.9 to 9.5) (21, 22). However, neither its bactericidal activity nor its mode of action has been examined in detail.

FIG 1.

Chemical structure of phytic acid (2,3,4,5,6-pentaphosphonooxycyclohexyl dihydrogen phosphate).

Sodium chloride is a typical condiment and food preservative that is widely used by the food industry and can be obtained from natural sources (it is present in the ocean at approximately 3 to 4% [wt/wt]) (23). The combination of organic acids and NaCl is a common example of hurdle technology in the food industry; many researchers have found that NaCl (at 3 to 5%) protects bacterial cells from the antimicrobial effects of organic acids (antagonism) (24–30). However, it is unclear how PA interacts with NaCl.

Escherichia coli O157:H7 is a representative foodborne pathogen that produces Shiga-like toxins, ingestion of which causes watery and bloody diarrhea or, occasionally, a more serious condition called hemolytic-uremic syndrome (31). In the United States, the bacterium causes an estimated 73,000 cases of infection per year, with up to 61 deaths (32), and several large outbreaks have occurred worldwide (33, 34). E. coli O157:H7 is a highly virulent pathogen because it carries genes for Shiga toxin production and has an adaptive acid tolerance response system that results in strong acid resistance (35–37). Therefore, we selected E. coli O157:H7 as the target pathogen for study of the bactericidal effects of natural acidic compounds.

The aims of the study were 2-fold, namely, to examine the antimicrobial potential of PA and other organic acids generally used by the food and livestock industries against both nonadapted and acid-adapted E. coli O157:H7 and to examine the antimicrobial effects of PA and NaCl (alone and in combination) and the mechanism underlying the interactions between PA and NaCl.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Three strains of Shiga-like-toxin-producing E. coli O157:H7, i.e., ATCC 35150 (harboring the stx1 and stx2 genes), ATCC 43889 (harboring stx2), and ATCC 43895 (harboring stx1 and stx2), were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). All strains have inherent acid-adaptable (ATCC 43889) or acid-resistant (ATCC 35150 and ATCC 43895) characteristics (38). The strains were stored at −20°C in tryptic soy broth (TSB) (Difco, Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA) containing 20% glycerol and were subcultured on a monthly basis.

Bacterial cell suspensions.

Each strain was cultivated for 24 h at 37°C in either TSB without glucose or TSB with glucose to obtain stationary-phase nonadapted cells or acid-adapted cells (cells adapted to pH 4.7 to 4.8), respectively (39). Cultures of individual cells of bacterial strains (either nonadapted or acid adapted) were mixed separately in a centrifuge tube and washed twice with 0.85% sterile saline by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 15 min. The final cell pellet was resuspended in 0.85% sterile saline to yield a prepared cell suspension of 9 to 10 log CFU/ml.

Chemical agents.

Purified acetic acid, citric acid, dl-lactic acid, dl-malic acid, and PA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Stock solutions (50% [wt/wt]) were prepared by dissolving each compound in deionized water (DW). Stock solutions were then sterilized by microfiltration using a polytetrafluoroethylene syringe filter (DISMIC-25HP; pore size, 0.45 μm; Toyo Roshi Kaisha Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) prior to the experiments. An appropriate amount of NaCl (Junsei Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was dissolved in DW to yield a working concentration (2 to 36% [wt/wt]) and then was autoclaved. A hydrochloric acid solution (35% [wt/wt] in water; Matsunoen Chemical Ltd., Osaka, Japan) was prepared (5 M) in sterile DW and used to adjust pH levels. All working solutions were prepared on the day of the experiment, and each was mixed thoroughly using a vortex mixer (KMC-1300V; Vision Scientific Co. Ltd., Daejeon, South Korea) at high speed for 1 min immediately prior to use.

Treatments.

An appropriate amount of each organic acid stock solution was added to sterile 0.85% saline (for single treatment, the final acid concentrations were 0.2%, 0.4%, 0.8%, and 1.6% [wt/wt]; for combined treatment, the final acid concentrations were 0.05%, 0.1%, 0.2%, and 0.4% [wt/wt] for PA and 0.4% [wt/wt] for other organic acids, in 2%, 3%, or 4% NaCl [wt/wt]). The effect of NaCl alone was assessed by exposing bacteria to solutions containing graded concentrations of NaCl (2%, 3%, 4%, 8%, 16%, and 32% [wt/wt]) approaching maximum solubility (36% [wt/wt] at 25°C). The net effect of pH was examined by using a sterile 0.85% saline solution, the pH of which was adjusted with 5 M HCl solution. Sterile glass culture tubes containing 9.9 ml of each solution were equilibrated to 22°C in a shaking water bath (VS-1205SW1; Vision Scientific Co. Ltd.) before the experiment. A prepared cell suspension (0.1 ml) was added to each solution (final concentration of target bacterial cells, 7 to 8 log CFU/ml). Both nonadapted and acid-adapted E. coli O157:H7 cells were exposed to each test solution for 5 min at 22°C, with shaking (100 rpm).

Viable cell counts and recovery of injured cells.

Untreated and treated bacterial cells were diluted to 10−6 in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (0.8% NaCl, 0.144% Na2HPO4, 0.024% KH2PO4, and 0.02% KCl [pH 7.4]). Both nondiluted samples (1 ml per five agar plates) and diluted samples (0.2 ml onto two agar plates) were spread plated onto tryptic soy agar (TSA) (Difco) plates and incubated at 37°C for 24 h (detection limit, 1 CFU/ml). Colonies growing on the plates were counted, and bacterial counts were expressed as a logarithmic value. To measure the residual antimicrobial effects of the treatment solution on target bacterial cells growing on the surface of the plates during incubation, 0.1 ml of cell suspension (7 to 8 log10 CFU/ml) and 0.1 ml of working solution were plated onto TSA plates, and bacterial growth was monitored at 37°C for 24 h. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Test solutions of the combined treatment-bacterial cell combinations (1 ml) that resulted in complete inactivation of the inoculum were inoculated into 9 ml of TSB, and recovery of injured cells was examined after incubation at 37°C for 24 h.

pH measurements.

The pH of each solution was measured three times using a pH meter (SevenCompact S220; Mettler-Toledo Inc., Columbus, OH, USA).

Statistical analysis.

All data were evaluated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Tukey's studentized range test was used to calculate the least significant differences between mean values (P < 0.05).

Cell staining.

Propidium iodide (PI) Molecular Probes reagent (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Grand Island, NY, USA) was used for cell staining (40). A stock solution of PI (3 mM) was prepared by dissolving the compound in sterile DW. The stock solution was then stored at 4°C in the dark. Cell suspensions (approximately 6 to 7 log CFU/ml) of untreated cells (living cells), treated cells, or dead cells (after treatment with 70% ethyl alcohol at 22°C for 5 min) were prepared in sterile PBS. Immediately after treatment, cells were diluted 10-fold in sterile PBS to prevent further bactericidal activity. Residual chemicals were removed by two washes with centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 3 min at 4°C. The diluted bacterial cells were then reconcentrated (10-fold). All target cells were stained with PI (final concentration, 60 μM) at 37°C for 20 min in the dark. The stained cells were then washed twice with sterile PBS and used for flow cytometry.

Flow cytometric analysis.

Flow cytometric analysis was performed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) with an excitation wavelength of 488 nm, generated by a blue argon laser (15 mW). Data were analyzed using BD CellQuest Pro software (Becton Dickinson Biosciences). An appropriate optical filter (FL3, ≤670 nm) was used to measure the red fluorescence emitted by PI. Light signals were detected as logarithmic signals by a photodiode detector with a forward scatter voltage setting of E02, and every 50,000 events were acquired at a flow rate of 12 μl/min. The acquired events were depicted as a histogram, and the M1 region was set using living and dead cells (both nonadapted and acid-adapted E. coli O157:H7 cells). The percentage of cells in the M1 region was calculated using the stat option in BD CellQuest Pro software.

RESULTS

Effects of treatment with phytic acid, other organic acids, or sodium chloride.

Table 1 shows the pH and antimicrobial effects of PA and other organic acids against E. coli O157:H7 when used at the same concentrations (0.2%, 0.4%, 0.8%, and 1.6%). While the pH of acetic, citric, lactic, and malic acids at these concentrations ranged from 2.5 to 3.0, 2.0 to 2.5, 2.1 to 2.6, and 2.0 to 2.5, respectively, PA had a much lower pH in sterile 0.85% saline solution (pH 1.3 to 1.9; P < 0.05). Indeed, PA showed the strongest bactericidal activity and the lowest pH (P < 0.05). The other organic acids had no effect on the bacterial population in the inoculum (P > 0.05), with the exception of citric acid (1.6%) or lactic acid (1.6%) treatment of nonadapted cells. Acid-adapted E. coli O157:H7 cells were significantly more tolerant to 0.4 to 1.6% PA than were nonadapted cells (P < 0.05). NaCl alone (up to its maximum solubility level of 36.0%) had no effect on the populations of nonadapted and acid-adapted E. coli O157:H7 cells after 5 min of treatment (P > 0.05) (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Effects of various organic acids (at 0.2 to 1.6%) on nonadapted and acid-adapted E. coli O157:H7 cells treated at 22°C for 5 min

| Organic acid and concn (% [wt/wt]) | pH (mean ± SD)a | Effect of organic acid on indicated bacteria (log CFU/ml) (mean ± SD)b |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonadapted cells | Acid-adapted cells | ||

| Acetic acid | |||

| 0.2 | 3.02 ± 0.01 A | −0.03 ± 0.06 Aa | −0.01 ± 0.05 Aa |

| 0.4 | 2.86 ± 0.02 B | −0.02 ± 0.07 Aa | −0.01 ± 0.02 Aa |

| 0.8 | 2.70 ± 0.01 C | −0.01 ± 0.08 Aa | −0.01 ± 0.03 Aa |

| 1.6 | 2.53 ± 0.02 E | −0.04 ± 0.08 Aa | 0.00 ± 0.09 Aa |

| Citric acid | |||

| 0.2 | 2.49 ± 0.02 E | 0.01 ± 0.01 Aa | −0.01 ± 0.02 Aa |

| 0.4 | 2.31 ± 0.01 F | 0.03 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.00 ± 0.02 Aa |

| 0.8 | 2.13 ± 0.01 GH | 0.01 ± 0.01 Aa | −0.03 ± 0.01Ab |

| 1.6 | 1.97 ± 0.01 J | 0.60 ± 0.08 Ba | 0.01 ± 0.07 Ab |

| Lactic acid | |||

| 0.2 | 2.63 ± 0.01 D | 0.01 ± 0.03 Aa | −0.02 ± 0.01 Aa |

| 0.4 | 2.48 ± 0.02 E | 0.01 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.00 ± 0.02 Aa |

| 0.8 | 2.29 ± 0.01 F | 0.02 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.00 ± 0.04 Aa |

| 1.6 | 2.12 ± 0.01 H | 0.64 ± 0.02 Ba | 0.29 ± 0.12 ABb |

| Malic acid | |||

| 0.2 | 2.53 ± 0.01 E | 0.02 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.00 ± 0.04 Aa |

| 0.4 | 2.35 ± 0.01 F | 0.03 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.01 ± 0.03 Aa |

| 0.8 | 2.19 ± 0.01 G | 0.03 ± 0.03 Aa | 0.02 ± 0.03 Aa |

| 1.6 | 2.04 ± 0.02 I | 0.03 ± 0.03 Aa | 0.04 ± 0.04 Aa |

| Phytic acid | |||

| 0.2 | 1.86 ± 0.01 K | 0.46 ± 0.28 Ba | 0.03 ± 0.20 Aa |

| 0.4 | 1.64 ± 0.01 L | 2.68 ± 0.39 Ca | 0.41 ± 0.35 Bb |

| 0.8 | 1.49 ± 0.04 M | 5.77 ± 0.08 Da | 4.01 ± 0.09 Cb |

| 1.6 | 1.29 ± 0.08 N | >6.13 ± 0.02 Ea | 4.54 ± 0.21 Db |

The initial pH value was 6.59 ± 0.02. Values in this column denoted by different capital letters (A through N) are significantly different (P < 0.05).

The initial nonadapted and acid-adapted E. coli O157:H7 populations were 7.13 ± 0.02 log CFU/ml and 7.02 ± 0.06 log CFU/ml, respectively. Values in the same column (A to E) or row (a and b) but denoted by different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Combination treatment with phytic acid or organic acids plus sodium chloride.

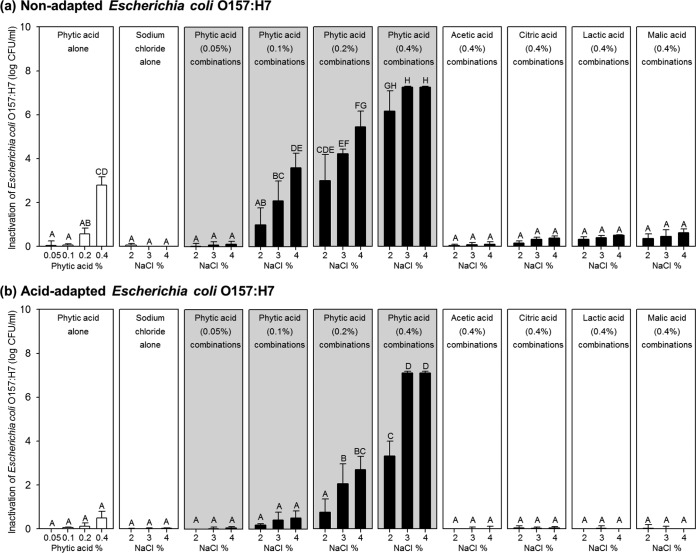

To examine the effects of PA or other organic acids plus NaCl (either alone or in combination), each was used at a concentration that showed negligible or insignificant bactericidal activity, as follows: 0.05 to 0.4% for PA, 0.4% for organic acids other than PA, and 2 to 4% for NaCl. Figure 2 shows bactericidal activity against nonadapted (Fig. 2a) and acid-adapted (Fig. 2b) E. coli O157:H7 cells mediated by single or combined treatment with PA and NaCl at 22°C for 5 min, compared with that mediated by combinations of other organic acids with sodium chloride.

FIG 2.

Inactivation of nonadapted (a) and acid-adapted (b) Escherichia coli O157:H7 cells treated with 0.05 to 0.4% phytic acid alone, 2 to 4% sodium chloride alone, a combination of the two, or combinations of sodium chloride plus other organic acids (acetic, citric, lactic, and malic acid) at 0.4% (wt/wt). The gray panels represent combinations of sodium chloride and phytic acid. Initial nonadapted and acid-adapted E. coli O157:H7 populations were 7.13 ± 0.02 log CFU/ml and 7.02 ± 0.06 log CFU/ml, respectively. Values in the same panel but denoted by different capital letters (A to H) are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Figure 2a shows that acetic, citric, lactic, and malic acids had no effect on nonadapted cells when used in combination with 2 to 4% NaCl; the reductions in the bacterial population mediated by combined treatment were not significantly different from those mediated by individual treatment (P > 0.05). However, PA plus NaCl had significantly greater bactericidal effects than did treatment with either alone (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2a, gray panels). As the concentrations of PA and NaCl were increased, a clear synergistic interaction was observed. While treatment with PA alone (up to 0.2%) yielded a negligible reduction in the population of nonadapted E. coli O157:H7 cells (<0.6 log CFU/ml), treatment with 0.1 or 0.2% PA plus 3 or 4% NaCl had much greater effects (2.1 to 5.5 log CFU/ml) (P < 0.05). When 0.4% PA was tested in combination with 3 or 4% NaCl, all cells in the inoculum were completely inactivated (>7.3-log CFU/ml reduction) and no cells recovered after further culture in TSB at 37°C for 24 h (data not shown). Combination treatment resulted in an additional 4.5-log CFU/ml reduction in the bacterial population, compared with individual treatment (PA, 2.8 log CFU/ml; NaCl, <0.1 log CFU/ml).

Figure 2b shows the results from the same experiment using acid-adapted E. coli O157:H7 cells. In common with the experiment using nonadapted cells, the combination of acetic, citric, lactic, or malic acid (each at 0.4%) plus NaCl had no effect on the population of acid-adapted E. coli O157:H7 cells (P > 0.05). A negligible reduction (<0.5 log CFU/ml) was observed after treatment with PA or NaCl alone; however, treatment with 0.2% PA plus 3 or 4% NaCl or 0.4% PA plus 2 to 4% NaCl had significantly greater effects (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2b, gray panels). In particular, the combination of 0.4% PA plus 3 or 4% NaCl eradicated all cells in the inoculum (>7.0-log CFU/ml reduction), with no recoverable cells (data not shown). These results show that PA in combination with NaCl has clear synergistic bactericidal actions; indeed, treatment achieved an additional 6.6-log CFU/ml reduction, compared with that achieved with either PA (0.5-log CFU/ml reduction) or NaCl (<0.1-log CFU/ml reduction) alone.

The combination of 0.4% PA plus 3 or 4% NaCl (pH 1.4 to 1.6) was selected for the validation experiment because these conditions led to complete inactivation of the inoculum. When both nonadapted and acid-adapted E. coli O157:H7 cells were inoculated into a series of 0.85% saline solutions with the same pH values as the PA-containing test solutions (pH 1.4 to 1.6), some cells in the inoculum survived after 5 min (nonadapted cells, 2.9 to 3.0 log CFU/ml; acid-adapted cells, 6.7 to 6.9 log CFU/ml) (data not shown). In addition, lowering the pH of 3 or 4% NaCl to the same level as that of the combined solutions (pH 1.4 to 1.6) did not eradicate all of the cells in the inoculum (survival of nonadapted cells, 2.3 to 2.5 log CFU/ml; survival of acid-adapted cells, 2.8 to 3.6 log CFU/ml) (data not shown).

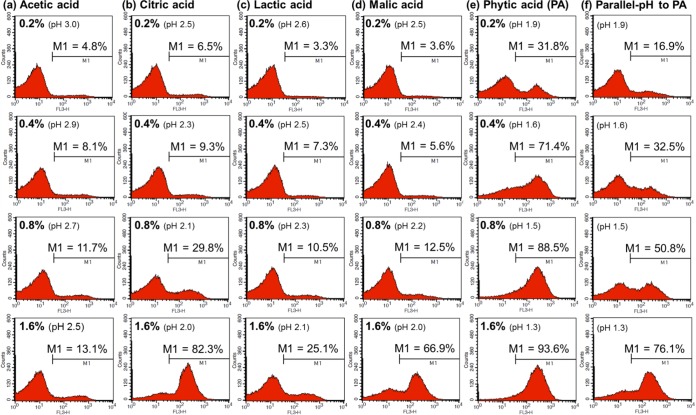

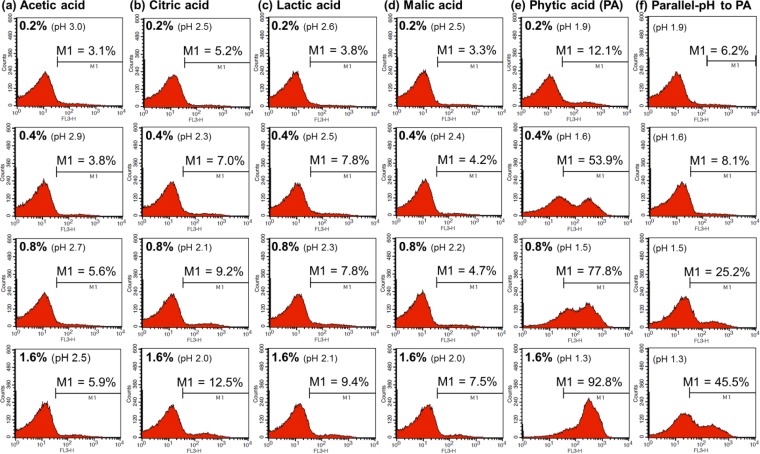

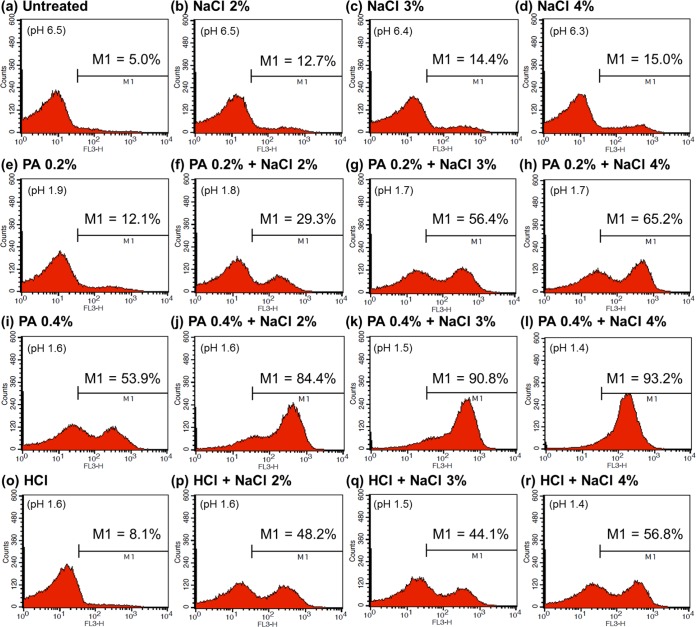

Effects of phytic acid and other organic acids alone on membrane integrity.

Figures 3 and 4 show how acetic acid, citric acid, lactic acid, malic acid, and PA affect the membrane integrity of nonadapted and acid-adapted E. coli O157:H7 cells, respectively. In addition, we measured the net effect of pH by treating cells with 0.85% saline solutions in which the pH had been adjusted to ensure it was the same as that in the PA solutions (pH adjusted with HCl). The percentage values for M1 indicate the proportions of damaged cells after each treatment. The results showed that the membrane-permeabilizing effect of PA was clearly greater than that of the other organic acids. The number of damaged cells tended to be much higher in the PA-treated groups (Fig. 3e and 4e) than in the other acid-treated groups (Fig. 3a to d and 4a to d) or in groups treated with pH-equivalent 0.85% saline solutions (Fig. 3f and 4f).

FIG 3.

Flow cytometric analysis of nonadapted Escherichia coli O157:H7 cells treated with 0.2 to 1.6% acetic acid (a), citric acid (b), lactic acid (c), malic acid (d), or phytic acid (PA) (e) or with NaCl-HCl solutions at pH values equivalent to those of 0.2 to 1.6% PA solutions (f).

FIG 4.

Flow cytometric analysis of acid-adapted Escherichia coli O157:H7 cells treated with 0.2 to 1.6% acetic acid (a), citric acid (b), lactic acid (c), malic acid (d), phytic acid (PA) (e), or NaCl-HCl solutions with pH values equivalent to those of 0.2 to 1.6% PA solutions (f).

For example, treatment with 0.4% PA led to the permeabilization of >50% of nonadapted (71.4%) and acid-adapted (53.9%) E. coli O157:H7 cells, whereas the other organic acids had little effect when tested at the same concentrations (cells in the M1 region, nonadapted, 5.6 to 9.3%; acid adapted, 3.8 to 7.0%). When the results for cells treated with 0.2 to 0.4% PA (pH 1.6 to 1.9) were compared with those for cells treated with pH-equivalent 0.85% saline solutions, we found that the percentages of permeabilized cells were much higher for the former (nonadapted, 31.8 to 71.4% [Fig. 3e]; acid adapted, 12.1 to 53.9% [Fig. 4e]) than for the latter (nonadapted, 16.9 to 32.5% [Fig. 3f]; acid adapted, 6.2 to 8.1% [Fig. 4f]).When 0.8% PA was applied, the percentages of damaged nonadapted and adapted cells reached 88.5% and 77.8%, respectively; when 1.6% PA was applied, the corresponding values were 93.6% and 92.8%, respectively. These percentages were much higher than those recorded after treatment with the other organic acids at the same working concentrations (cells in the M1 region, nonadapted, 10.5 to 82.3%; acid adapted, 4.7 to 12.5%). In addition, the membrane-permeabilizing effects of 0.85% saline solutions at pH values equivalent to those of the 0.8% and 1.6% PA solutions were much weaker than those of the PA solutions (nonadapted, 50.8 to 76.1% [Fig. 3f]; acid adapted, 25.2 to 45.5% [Fig. 4f]).

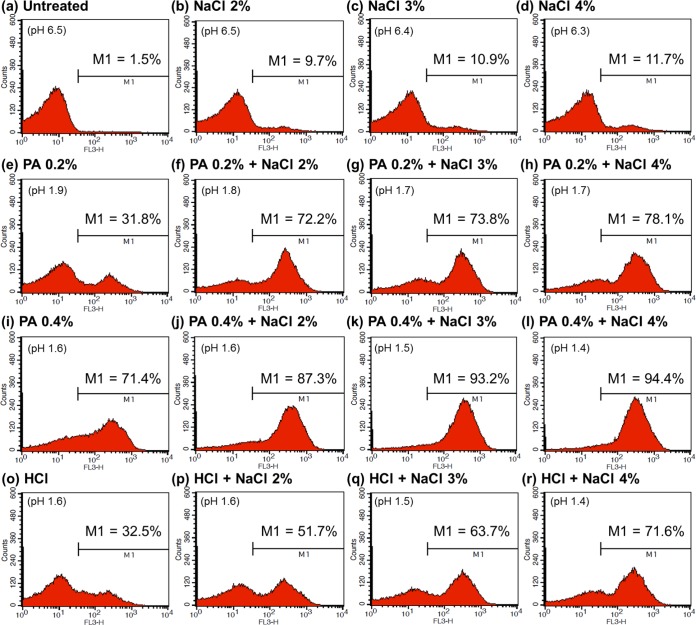

Changes in membrane integrity induced by treatment with phytic acid, sodium chloride, or a combination of the two.

Finally, to investigate the mechanism underlying the synergistic activity of 0.2 to 0.4% PA plus 2 to 4% NaCl solutions, we examined the membrane integrity of E. coli O157:H7 cells before and after treatment. The histograms generated in flow cytometric analysis of nonadapted E. coli O157:H7 cells are shown in Fig. 5. While fewer cells (9.7 to 11.7%) were permeabilized by treatment with 2 to 4% NaCl alone (Fig. 5b to d), increasing numbers were damaged upon addition of 0.2% or 0.4% PA to the 2 to 4% NaCl solutions (cells in the M1 region after addition of 0.2% PA, 72.2 to 78.1%; after addition of 0.4% PA, 87.3 to 94.4%). In particular, the combination of 0.4% PA with 3 or 4% NaCl permeabilized almost all of the cells in the inoculum (cells in the M1 region, 93.2 to 94.4%). When 2 to 4% NaCl solutions with pH values equivalent to those of the 0.4% PA solutions were applied (Fig. 5p to r), the proportions of damaged cells (51.7 to 71.6%) were significantly smaller than those induced by 0.4% PA plus 2 to 4% NaCl (87.3 to 94.4%).

FIG 5.

Flow cytometric analysis of nonadapted Escherichia coli O157:H7 cells that were untreated (a) or treated with 2 to 4% NaCl (b to d), 0.2% PA (e), 0.4% PA (i), combinations of 0.2% PA (f to h) or 0.4% PA (j to l) plus 2 to 4% NaCl, a solution with a pH equivalent to that of 0.4% PA (o), or 2 to 4% NaCl solutions with pH values equivalent to those of 0.4% PA plus 2 to 4% NaCl (p to r).

The results for acid-adapted cells are presented in Fig. 6. As shown in Fig. 6b to d, treatment with NaCl alone had little effect on the membrane integrity of acid-adapted cells (cells in the M1 region, 12.7 to 15.0%). Addition of 0.2 or 0.4% PA to 2 to 4% NaCl increased the proportions of damaged cells (0.2% PA, 29.3 to 65.3%; 0.4% PA, 84.4 to 93.2%) (Fig. 6f to h or j to l, respectively); however, the increases were smaller than those observed for nonadapted cells (0.2% PA, 72.2 to 78.1%; 0.4% PA, 87.3 to 94.4%) (Fig. 5f to h or j to l, respectively). In agreement with the results obtained for nonadapted cells, the combination of 0.4% PA plus 3 or 4% NaCl damaged >90% of acid-adapted cells. The extent of the damage was much greater (cells in the M1 region, 90.8 to 93.2%) (Fig. 6k to l) than that caused by the net effect of pH and 3 or 4% NaCl (cells in the M1 region, 44.1 to 56.8%) (Fig. 6q to r).

FIG 6.

Flow cytometric analysis of acid-adapted Escherichia coli O157:H7 cells that were untreated (a) or treated with 2 to 4% NaCl (b to d), 0.2% PA (e), 0.4% PA (i), combinations of 0.2% PA (f to h) or 0.4% PA (j to l) plus 2 to 4% NaCl, a solution with a pH equivalent to that of 0.4% PA (o), or 2 to 4% NaCl solutions with pH values equivalent to those of 0.4% PA plus 2 to 4% NaCl (p to r).

DISCUSSION

The present study examined the antimicrobial potential of a “natural” compound, namely, PA, and its synergistic interaction with NaCl. The major findings were that PA exhibited significantly stronger bactericidal effects against acid-resistant E. coli O157:H7 than did other organic acids at equivalent working concentrations and that PA plus NaCl had marked synergistic antibacterial effects. A combination of PA (0.4%) plus NaCl (3 or 4%) resulted in an additional reduction of 4 to 6 log CFU/ml, compared with the sum of the effects of PA alone and NaCl alone after 5 min; this synergism was much greater for PA than for other organic acids.

A previous report showed that E. coli is much more able to survive under extremely acidic conditions than other Enterobacteriaceae (41). Lin et al. (42) found that E. coli O157:H7 could resist pH values of 2.0 to 2.5 for 3 h (survival rates, 16 to 98%). Here we found that treatment with 0.8 to 1.6% PA (pH 1.3 to 1.5) led to a >4-log CFU/ml reduction in E. coli O157:H7 numbers within 5 min. Compared with other organic acids at the same concentrations, PA showed significantly stronger effects and greater acidity (pH 1.3 to 1.9) than acetic, citric, lactic, or malic acid (pH 2.0 to 2.5). However, it is difficult to conclude that the low pH of PA was the main reason for its greater bactericidal effects, because acid solutions of equivalent pH did not generate the same bactericidal effects. Thus, the role of charged phytate ion merits attention as a factor that leads to significantly greater bactericidal activity against E. coli O157:H7.

Gram-negative bacteria such as E. coli possess an outer membrane (OM) that functions as a barrier to antimicrobial agents or antibiotics (43). The protective effect of the OM is due mainly to the presence of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) molecules in the outer leaflet (44). Agents such as EDTA, citric acid, and lactic acid act on the OM (45–47) to disintegrate LPS by chelating OM-stabilizing divalent cations (e.g., Mg2+ and Ca2+); this is an effective strategy against Gram-negative bacteria. PA contains six reactive phosphate groups, which are responsible for its strong chelating capacity (22). These groups gradually become negatively charged as the hydrogen ion dissociates under aqueous conditions. Previous studies have focused only on the food-spoiling qualities of PA and how to overcome them (14, 21, 48); however, this strong chelating agent may have potential as an effective surface sanitizer because it can disrupt the molecular interactions between LPS molecules expressed on the OM of pathogenic bacteria.

Here we showed that PA disrupts the membrane integrity of E. coli O157:H7 cells, which supports this hypothesis. To empirically measure the damage to the cell membrane, we stained the treated cells with PI, which cannot penetrate intact cell membranes (49, 50). The permeabilizing ability of PA was much greater than that of acid solutions of equivalent pH, as demonstrated by higher PI uptake and stronger red fluorescence signals (Fig. 3 and 4). The disruption of membrane integrity by PA (due to the presence of H+ and phytate ions) was much greater (12.1 to 93.6% damaged cells) (Fig. 3e and 4e) than that by solutions containing HCl (which has the same number of H+ ions but Cl− rather than phytate) (16.9 to 76.1% damaged cells) (Fig. 3f and 4f). This may indicate that both H+ and charged phytate ions play major roles in bacterial inactivation.

In general, we expected that PA would show greater antimicrobial efficacy than other organic acids because the acidity of the protons derived from PA varies from very strong to very weak (pKa = 1.9 to 9.5) (22), whereas that of protons derived from the other organic acids is weak (pKa = 3.1 to 6.4). This result has implications regarding the practical use of organic acids as surface-sanitizing agents (51, 52). At the same working concentrations, the bactericidal and membrane-permeabilizing activities of PA were much greater than those of the other organic acids. Also, whereas the pungent odor of organic acids makes them unsuitable for use as surface sanitizers, PA is odorless. In addition, citric and malic acid are commonly used as natural chelating agents (53); therefore, the much stronger chelating ability of PA makes it a practical alternative agent for permeabilization of bacterial cells. Finally, the molarities of the 0.4% acetic, citric, lactic, and malic acid solutions were 66.9, 20.9, 44.6, and 30.0 mM, respectively, whereas that of PA was only 6.1 mM (9 to 29% that of other organic acids). Because PA showed much higher efficacy at lower molar concentrations, it might have potential as an alternative effective surface sanitizer.

We also found that the antibacterial action of PA was markedly enhanced in the presence of 3 or 4% NaCl. In contrast, the combination of other organic acids plus NaCl had no effect under the same experimental conditions. Previous studies examining the antimicrobial relationship between organic acids and NaCl mainly used long exposure times (0.5 to 120 h) along with acetic or lactic acid (pH 3.0 to 4.2) and 2 to 8% NaCl in nutrient broth or TSB to model acidic foods (e.g., dressings, fermented foods, pickled vegetables, and sauces) (24–29). They all concluded that NaCl (3 to 5%) protects cells from the antimicrobial effects of organic acids. Casey and Codon (24) reported that NaCl protected bacteria by reducing the water activity, which decreases the cell volume and increases the cytoplasmic pH. Kitko et al. (30) also reported that osmolytes, including NaCl, contribute to cytoplasmic pH homeostasis by increasing microbial recovery from a rapid acid shift. However, we found that NaCl did not protect E. coli O157:H7 cells from the bactericidal and chelating activities of PA at low pH (pH 1.4 to 1.9), even after a short exposure (5 min).

Decad and Nikaido (54) found that cell wall damage was minimal at NaCl concentrations up to 0.3 M (approximately 1.7%); however, a large percentage of the cells underwent plasmolysis at NaCl concentrations greater than 0.5 M (2.9%). While NaCl (2 to 4% [0.35 to 0.71 M]) alone had no effect on viable E. coli O157:H7 counts, the results of the present study partially support those of Decad and Nikaido (54) because the membrane integrity of the cells was slightly affected by treatment with 2 to 4% NaCl (9.7 to 15.0% damaged cells). In addition, when cell membranes are permeabilized by the chelating action of 0.4% PA, a few Na+ and Cl− ions may significantly disrupt pH homeostasis inside the cells (84.4 to 94.4% damaged cells). It can be presumed that both H+ and phytate ions play leading roles in the marked synergistic effects of PA and NaCl, because addition of incremental amounts of PA to a NaCl solution had greater effects (90.8 to 94.4% damaged cells) than did NaCl-HCl solutions of equivalent pH (44.1 to 71.6% damaged cells).

Since acid adaptation significantly increases the acid tolerance of E. coli O157:H7 cells (36, 39, 42), we suggest that the combination of NaCl plus PA, rather than NaCl plus other organic acids, is an effective tool for controlling acid-resistant E. coli O157:H7. Based on the evidence presented above, we suggest the following mechanistic steps to explain the synergistic effects of PA and NaCl: (i) reactive phosphate groups on PA chelate divalent cations, thereby releasing LPS from the OM; (ii) cells are permeabilized, but this damage is recoverable; (iii) Na+, Cl−, and H+ ions more easily penetrate the cell membrane; and (iv) these charged ions attack the organelles, resulting in complete dysfunction of the cells.

PA is listed as a food additive in the Food Additive Code in Korea (55) and the Generally Recognized as Safe Notification (GRN) inventory published by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (56). From a safety perspective, a number of repeated-dose studies have been conducted in rodents; no adverse effects were observed in a rat model with orally administered PA in the diet or drinking water at a concentration of approximately 1.0 to 2.5% for up to 12 weeks (17, 57–61). In addition, exposing the skin to PA may have more advantages than disadvantages. Some commercially available cosmetics contain PA, and several studies report that PA has the following positive effects on human skin: moisturization, lightening, increased elasticity, peeling, and improved acne vulgaris and melasma symptoms (62–64).

To conclude, the results of the present study suggest that PA is effective against E. coli O157:H7 and has a greater membrane-permeabilizing capacity than commonly used organic acids. It also shows outstanding synergistic effects when combined with NaCl. Both of these compounds are naturally occurring and cheap; PA is prepared from natural waste products from the rice-milling industry, and NaCl can be obtained from the ocean. The chelating characteristics of PA may enable other cell-impermeant antimicrobial agents (either electrically charged or hydrophobic molecules) to penetrate the cytoplasm, thereby increasing the susceptibility of microorganisms to hydrophobic antibiotics, detergents, lysozyme, or bacteriocins. These findings shed new light on the development of novel natural antimicrobial agents that have utility as disinfectants. Such agents may improve the microbiological safety of food and ensure hygiene in livestock industries and health care centers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF; grant NRF-2011-0012712).

We thank the School of Life Sciences and Biotechnology for BK 21 PLUS (Korea University) and the Institute of Biomedical Science and Food Safety, CJ-Korea University Food Safety Hall, for providing equipment and facilities.

We have no conflicts to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. 2014. Food safety: fact sheet no. 399. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs399/en. Accessed 22 July 2015.

- 2.Joshi K, Mahendran R, Alagusundaram K, Norton T, Tiwari BK. 2013. Novel disinfectants for fresh produce. Trends Food Sci Technol 34:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2013.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen JH, Ren Y, Seow J, Liu T, Bang WS, Yuk HG. 2012. Intervention technologies for ensuring microbiological safety of meat: current and future trends. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 11:119–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2011.00177.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hrudey SE. 2009. Chlorination disinfection by-products, public health risk tradeoffs and me. Water Res 43:2057–2092. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parish ME, Beuchat LR, Suslow TV, Harris LJ, Garrett EH, Farber JN, Busta FF. 2003. Methods to reduce/eliminate pathogens from fresh and fresh-cut produce. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2:161–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2003.tb00033.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carocho M, Morales P, Ferreira ICFR. 2015. Natural food additives: quo vadis? Trends Food Sci Technol 45:284–295. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2015.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlson BA, Ruby J, Smith GC, Sofos JN, Bellinger GR, Warren-Serna W, Centrella B, Bowling RA, Belk KE. 2008. Comparison of antimicrobial efficacy of multiple beef hide decontamination strategies to reduce levels of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella. J Food Prot 71:2223–2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cutter CN, Siragusa GR. 1994. Efficacy of organic acids against Escherichia coli O157:H7 attached to beef carcass tissue using a pilot scale model carcass washer. J Food Prot 57:97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jang HI, Rhee MS. 2009. Inhibitory effect of caprylic acid and mild heat on Cronobacter spp. (Enterobacter sakazakii) in reconstituted infant formula and determination of injury by flow cytometry. Int J Food Microbiol 133:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi MJ, Kim SA, Lee NY, Rhee MS. 2013. New decontamination method based on caprylic acid in combination with citric acid or vanillin for eliminating Cronobacter sakazakii and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in reconstituted infant formula. Int J Food Microbiol 166:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akbas MY, Ölmez H. 2007. Inactivation of Escherichia coli and Listeria monocytogenes on iceberg lettuce by dip wash treatments with organic acids. Lett Appl Microbiol 44:619–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2007.02127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi YM, Kim OY, Kim KH, Kim BC, Rhee MS. 2009. Combined effect of organic acids and supercritical carbon dioxide treatments against nonpathogenic Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella typhimurium and E. coli O157:H7 in fresh pork. Lett Appl Microbiol 49:510–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2009.02702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olaimat AN, Holley RA. 2012. Factors influencing the microbial safety of fresh produce: a review. Food Microbiol 32:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlemmer U, Frølich W, Prieto RM, Grases F. 2009. Phytate in foods and significance for humans: food sources, intake, processing, bioavailability, protective role and analysis. Mol Nutr Food Res 53(Suppl 2):S330–S375. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minihane AM, Rimbach G. 2002. Iron absorption and the iron binding and anti-oxidant properties of phytic acid. Int J Food Sci Technol 37:741–748. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2621.2002.00619.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vucenik I, Shamsuddin AM. 2006. Protection against cancer by dietary IP6 and inositol. Nutr Cancer 55:109–125. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5502_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SH, Park HJ, Chun HK, Cho SY, Cho SM, Lillehoj HS. 2006. Dietary phytic acid lowers the blood glucose level in diabetic KK mice. Nutr Res 26:474–479. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2006.06.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu Q, Kanthasamy AG, Reddy MB. 2008. Neuroprotective effect of the natural iron chelator, phytic acid in a cell culture model of Parkinson's disease. Toxicology 245:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saw NK, Chow K, Rao PN, Kavanagh JP. 2007. Effects of inositol hexaphosphate (phytate) on calcium binding, calcium oxalate crystallization and in vitro stone growth. J Urol 177:2366–2370. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davidson PM, Taylor TM. 2007. Chemical preservatives and natural antimicrobial compounds, p 713–745. In Doyle MP, Beuchat LR (ed), Food microbiology: fundamentals and frontiers, 3rd ed ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oatway L, Vasanthan T, Helm JH. 2001. Phytic acid. Food Rev Int 17:419–431. doi: 10.1081/FRI-100108531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans WJ, McCourtney EJ, Shrager RI. 1982. Titration studies of phytic acid. J Am Oil Chem Soc 59:189–191. doi: 10.1007/BF02680274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Talley LD. 2002. Salinity patterns in the ocean, p 629–640. In Munn T, MacCracken MC, Perry JS (ed), Encyclopedia of global environmental change, vol 1 The Earth system: physical and chemical dimensions of global environmental change. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, England: http://www-pord.ucsd.edu/∼ltalley/papers/2000s/wiley_talley_salinitypatterns.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casey PG, Condon S. 2002. Sodium chloride decreases the bacteriocidal effect of acid pH on Escherichia coli O157:H45. Int J Food Microbiol 76:199–206. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jordan KN, Davies KW. 2001. Sodium chloride enhances recovery and growth of acid-stressed Escherichia coli O157:H7. Lett Appl Microbiol 32:312–315. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765X.2001.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chapman B, Jensen N, Ross T, Cole M. 2006. Salt, alone or in combination with sucrose, can improve the survival of Escherichia coli O157 (SERL 2) in model acidic sauces. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:5165–5172. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02522-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chapman B, Ross T. 2009. Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica are protected against acetic acid, but not hydrochloric acid, by hypertonicity. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:3605–3610. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02462-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoon JH, Bae YM, Oh SW, Lee SY. 2014. Effect of sodium chloride on the survival of Shigella flexneri in acidified laboratory media and cucumber puree. J Appl Microbiol 117:1700–1708. doi: 10.1111/jam.12637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee SY, Rhee MS, Dougherty RH, Kang DH. 2010. Antagonistic effect of acetic acid and salt for inactivating Escherichia coli O157:H7 in cucumber puree. J Appl Microbiol 108:1361–1368. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitko RD, Wilks JC, Garduque GM, Slonczewski JL. 2010. Osmolytes contribute to pH homeostasis of Escherichia coli. PLoS One 5:e10078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaper JB, Nataro JP, Mobley HL. 2004. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat Rev Microbiol 2:123–140. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 5 August 2013. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli: pathogens and protocols. http://www.cdc.gov/pulsenet/pathogens/ecoli.html. Accessed 19 November 2015.

- 33.Buchholz U, Bernard H, Werber D, Böhmer MM, Remschmidt C, Wilking H, Deleré Y, an der Heiden M, Adlhoch C, Dreesman J. 2011. German outbreak of Escherichia coli O104:H4 associated with sprouts. N Engl J Med 365:1763–1770. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michino H, Araki K, Minami S, Takaya S, Sakai N, Miyazaki M, Ono A, Yanagawa H. 1999. Massive outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection in schoolchildren in Sakai City, Japan, associated with consumption of white radish sprouts. Am J Epidemiol 150:787–796. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng HY, Yang HY, Chou CC. 2002. Influence of acid adaptation on the tolerance of Escherichia coli O157:H7 to some subsequent stresses. J Food Prot 65:260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leyer GJ, Wang L-L, Johnson EA. 1995. Acid adaptation of Escherichia coli O157:H7 increases survival in acidic foods. Appl Environ Microbiol 61:3752–3755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benjamin MM, Datta AR. 1995. Acid tolerance of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol 61:1669–1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berry ED, Cutter CN. 2000. Effects of acid adaptation of Escherichia coli O157:H7 on efficacy of acetic acid spray washes to decontaminate beef carcass tissue. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:1493–1498. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.4.1493-1498.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buchanan RL, Edelson SG. 1996. Culturing enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli in the presence and absence of glucose as a simple means of evaluating the acid tolerance of stationary-phase cells. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:4009–4013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berney M, Hammes F, Bosshard F, Weilenmann H-U, Egli T. 2007. Assessment and interpretation of bacterial viability by using the LIVE/DEAD BacLight kit in combination with flow cytometry. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:3283–3290. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02750-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin J, Lee IS, Frey J, Slonczewski JL, Foster JW. 1995. Comparative analysis of extreme acid survival in Salmonella Typhimurium, Shigella flexneri, and Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 177:4097–4104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin J, Smith MP, Chapin KC, Baik HS, Bennett GN, Foster JW. 1996. Mechanisms of acid resistance in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:3094–3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nikaido H. 2003. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 67:593–656. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.593-656.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raetz CRH, Whitfield C. 2002. Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu Rev Biochem 71:635–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vaara M. 1992. Agents that increase the permeability of the outer membrane. Microbiol Rev 56:395–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leive L. 1965. Release of lipopolysaccharide by EDTA treatment of Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 21:290–296. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(65)90191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Helander IM, Mattila-Sandholm T. 2000. Fluorometric assessment of Gram-negative bacterial permeabilization. J Appl Microbiol 88:213–219. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lopez HW, Leenhardt F, Coudray C, Remesy C. 2002. Minerals and phytic acid interactions: is it a real problem for human nutrition? Int J Food Sci Technol 37:727–739. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2621.2002.00618.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berney M, Weilenmann H-U, Egli T. 2006. Flow-cytometric study of vital cellular functions in Escherichia coli during solar disinfection (SODIS). Microbiology 152:1719–1729. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28617-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Breeuwer P, Abee T. 2000. Assessment of viability of microorganisms employing fluorescence techniques. Int J Food Microbiol 55:193–200. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00163-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim HM, Shim IS, Baek YW, Han HJ, Kim PJ, Choi K. 2013. Investigation of disinfectants for foot-and-mouth disease in the Republic of Korea. J Infect Public Health 6:331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cherrington CA, Hinton M, Mead GC, Chopra I. 1991. Organic acids: chemistry, antibacterial activity and practical applications. Adv Microb Physiol 32:87–108. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(08)60006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ekholm P, Virkki L, Ylinen M, Johansson L. 2003. The effect of phytic acid and some natural chelating agents on the solubility of mineral elements in oat bran. Food Chem 80:165–170. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00249-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Decad GM, Nikaido H. 1976. Outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. XII. Molecular-sieving function of cell wall. J Bacteriol 128:325–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. 2013. Food additives. http://www.mfds.go.kr/eng/index.do?nMenuCode=64. Accessed 30 April 2014.

- 56.Keefe DM. 2012. Agency response letter GRAS notice no. GRN 000381. http://www.fda.gov/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/GRAS/NoticeInventory/ucm313045.htm. Accessed 4 February 2015.

- 57.Hiasa Y, Kitahori Y, Morimoto J, Konishi N, Nakaoka S, Nishioka H. 1992. Carcinogenicity study in rats of phytic acid ‘Daiichi,’ a natural food additive. Food Chem Toxicol 30:117–125. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(92)90146-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gaetke LM, McClain CJ, Toleman CJ, Stuart MA. 2010. Yogurt protects against growth retardation in weanling rats fed diets high in phytic acid. J Nutr Biochem 21:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kamao M, Tsugawa N, Nakagawa K, Kawamoto Y, Fukui K, Takamatsu K, Kuwata G, Imai M, Okano T. 2000. Absorption of calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, iron and zinc in growing male rats fed diets containing either phytate-free soybean protein or soybean protein isolate or casein. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol 46:34–41. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.46.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Onomi S, Okazaki Y, Katayama T. 2004. Effect of dietary level of phytic acid on hepatic and serum lipid status in rats fed a high-sucrose diet. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 68:1379–1381. doi: 10.1271/bbb.68.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Szkudelski T. 2005. Phytic acid-induced metabolic changes in the rat. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 89:397–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2005.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Deprez P. 2003. Easy phytic solution: a new alpha hydroxy acid peel with slow release and without neutralization. Int J Cosmet Surg Aesthetic Dermatol 5:45–51. doi: 10.1089/153082003767787187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Al-Mokadem S, Al-Aasser O, Nassar A, Al-Sharkawy EA. 2013. Easy phytic peel as a therapeutic agent in acne vulgaris and melasma. Egypt J Dermatol Venerol 33:6–11. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sarkar R, Bansal S, Garg VK. 2012. Chemical peels for melasma in dark-skinned patients. J Cutan Aesthetic Surg 5:247–253. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.104912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]