Abstract

Importance

Identifying patients at risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression may facilitate more optimal nephrology care. Kidney failure risk equations (KFREs) were previously developed and validated in two Canadian cohorts. Validation in other regions and in CKD populations not under the care of a nephrologist is needed.

Objective

To evaluate the accuracy of the KFREs across different geographic regions and patient populations through individual-participant data meta-analysis.

Data Sources

Thirty-one cohorts, including 721,357 participants with CKD Stages 3–5 in over 30 countries spanning 4 continents, were studied. These cohorts collected data from 1982 through 2014.

Study Selection

Cohorts participating in the CKD Prognosis Consortium with data on end-stage renal disease.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data were obtained and statistical analyses were performed between July 2012 and June 2015. Using the risk factors from the original KFREs, cohort-specific hazard ratios were estimated, and combined in meta-analysis to form new “pooled” KFREs. Original and pooled equation performance was compared, and the need for regional calibration factors was assessed.

Main Outcome and Measure

Kidney failure (treatment by dialysis or kidney transplantation).

Results

During a median follow-up of 4 years, 23,829 cases of kidney failure were observed. The original KFREs achieved excellent discrimination (ability to differentiate those who developed kidney failure from those who did not) across all cohorts (overall C statistic, 0.90 (95% CI 0.89–0.92) at 2 years and 0.88 (95% CI 0.86–0.90) at 5 years); discrimination in subgroups by age, race, and diabetes status was similar. There was no improvement with the pooled equations. Calibration (the difference between observed and predicted risk) was adequate in North American cohorts, but the original KFREs overestimated risk in some non-North American cohorts. Addition of a calibration factor that lowered the baseline risk by 32.9% at 2 years and 16.5% at 5 years improved the calibration in 12/15 and 10/13 non-North American cohorts at 2 and 5 years, respectively (p=0.04 and p=0.02).

Conclusions and Relevance

KFREs developed in a Canadian population showed high discrimination and adequate calibration when validated in 31 multinational cohorts. However, in some regions the addition of a calibration factor may be necessary.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is increasing in incidence and prevalence worldwide.1 Rates of progression to kidney failure varies among individuals with CKD and depends on the severity of kidney disease, comorbid conditions, and risk of dying before kidney failure onset.2,3 Interventions to slow CKD progression, planning for initiation of dialysis and transplantation planning, and early creation of arteriovenous fistula have been advocated, but these strategies may be expensive and are associated with risks. Treatment would ideally be recommended only for patients at high risk of progression and where the benefit exceeds the harm.4,5

Tangri et al previously developed kidney failure risk equations (KFREs), which use demographic and laboratory data to predict progression of CKD to kidney failure.6 The KFREs were developed in 3,449 patients with CKD Stages 3–5 referred for nephrology care in Ontario, Canada, and validated in referred patients with CKD in British Columbia, Canada. The preferred KFREs (the 4-variable and 8-variable equations) are age-, sex- and laboratory value-based, thereby enabling automated risk reporting whenever laboratory tests are performed.7 The 4-variable equation requires age, sex, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR), facilitating integration into clinical practice.

The KFREs are widely used through electronic applications (e.g., www.qxmd.com/kfre), with some initial validation in other countries and health care systems.7–12 However, widespread adoption of the KFREs requires validation in additional populations including non-white ethnicities, patients not under nephrology care, and cohorts outside North America. The accuracy of the KFREs in different geographic regions and patient populations is evaluated here.

Methods

Participating Cohorts

Thirty-one cohorts participating in the Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium (CKD-PC) were selected for KFRE validation based on data availability.13 The CKD-PC is a collaborative research group integrating data from more than 50 cohorts spanning 40 countries and 2 million individuals.13 The diverse cohorts in the CKD-PC include populations across a wide range of baseline risk. For the purpose of this analysis, cohorts were selected to include patients with CKD Stages 3–5 [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 ml/min/1.73 m2] and absence of kidney failure at baseline who had follow-up information on kidney failure, defined as treatment by dialysis or a kidney transplant. Data transfer and analysis took place between July 2012 and June 2015; included cohorts collected data from September 1982 through October 2014. This study was approved for use of de-identified data by the institutional review board at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and the need for informed consent was waived.

Measurement of Variables in Cohorts

As in the original KFREs, GFR was estimated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) 2009 creatinine equation.14 Serum creatinine concentrations were standardized to isotope dilution mass spectrometry traceable methods where possible.14 For studies where creatinine measurements were not standardized to isotope dilution mass spectrometry, the creatinine levels were reduced by 5%, as previously reported.15,16 Albuminuria was represented as a log-transformed urine ACR. Alternative measures of urine protein excretion (protein-to-creatinine ratio, 24 hour urine collection, urinary dipstick) were transformed to the ACR using previously developed equations.6,17,18 When available, baseline values for serum albumin, phosphorous, calcium, and bicarbonate, as well as physical examination measures of weight, systolic and diastolic blood pressure were derived from each cohort. Age, sex and ethnicity (black/non-black), as well as the presence of diabetes and hypertension, were also derived from the individual cohorts, with information on race collected as part of routine clinical care for the health systems and as demographic data for the study cohorts. Diabetes was defined as fasting glucose of at least 7.0 mmol/L, non-fasting glucose of at least 11.1 mmol/L or glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) of at least 6.5%, use of glucose-lowering drugs, or self-reported diabetes. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure of at least 140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure of at least 90 mm Hg, or use of antihypertensive drugs for treatment of hypertension. Potential participants missing any baseline data were excluded from analysis. Information on individual cohorts is provided in eAppendix 1.

Statistical Analysis

There were four KFREs developed in the original cohorts: the 3-variable (age, sex, and eGFR), the 4-variable (3-variable + ACR), the 6-variable (4-variable + diabetes and hypertension), and the 8-variable (4-variable + calcium, phosphate, bicarbonate, and albumin). The 4-variable and 8-variable KFREs demonstrated the best performance in the original cohorts; thus, the focus of this validation effort centered on the 4-variable and 8-variable equations.

Participant-level data were analyzed for each individual cohort, and then meta-analysis was performed across studies using a random-effects model. Risk-relationships observed in the original cohorts were compared to those seen in the validation cohorts. Cox proportional hazards models were fit using the variables included in each of the original KFREs within each study, allowing both the regression coefficients and the baseline hazard to vary. All variables were centered (age 70 years, 56% male, eGFR 36 ml/min/1.73 m2, ACR 170 mg/g, phosphate 3.9 mg/dL, albumin 4.0 g/dL, bicarbonate 25.6 mEq/L, and calcium 9.4 mg/dL), as per the original study.6 The “refit” coefficients were then pooled across studies using random-effects meta-analysis. Pooled and original coefficients were compared using the z-test.19

Next, a set of “pooled” KFREs were developed to compare with the original KFREs. Pooled coefficients from the random-effects meta-analysis were combined with a pooled baseline hazard, defined as the average “refit” baseline hazard weighted by the number of kidney failure events.

Discrimination of the original and pooled KFREs was assessed using Harrell’s C statistic within each study, which was then meta-analyzed using random-effects models. Performance was also evaluated in predetermined subgroups of black/non-black race, presence or absence of diabetes mellitus, and age older/younger than 65 years. The discrimination of the original and pooled KFREs was compared by assessing the meta-analyzed difference in C statistic within individual studies. Finally, within each set of original and pooled KFREs, the discrimination of the 4- versus 6- and 4- versus 8-variable KFREs was compared by meta-analyzing the difference in individual study C statistics (6-variable performance is reported in the supplementary materials).

Calibration (the difference between observed and predicted risk) was examined by plotting the observed 2-year and 5-year probability of kidney failure in individual cohorts and comparing it to the predicted risk using the original and pooled KFREs. This was done in 5 risk categories: for 2 years, 0 to <2%, 2 to <6%, 6 to <10%, 10 to <20%, and ≥20%; for 5 years, 0 to <5%, 5 to <15%, 15 to <25%, 25 to <50%, ≥50%. In the absence of clinical practice guidelines that recommend risk cut-offs/strata for CKD progression, the risk categories used were adopted from the original development study and subsequent CKD-PC publications.6 Calibration varied across cohorts; thus, factors that might explain heterogeneity in baseline risk were investigated by regressing cohort-specific baseline risk on cohort characteristics (e.g., region of cohort, mean eGFR, proportion of the cohort with African American ethnicity, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension). Baseline risk was estimated for each cohort using Cox proportional hazards models, holding the variable coefficients constant and equal to the original KFRE regression coefficients, but allowing the intercept to vary. The only cohort characteristic associated with cohort-specific baseline hazard was region of cohort, with higher baseline risk in North American cohorts compared with non-North American cohorts.

Regional variation in baseline risk was then addressed through the development of two regional calibration factors (North America and non-North America). The regional calibration factors were developed as the ratio of the event-weighted regional mean to the original baseline hazard. A Brier Score, the squared difference between the observed vs. predicted binary outcomes (observed minus predicted risk), was used to evaluate whether calibration improved with the “regional-calibrated original” KFREs, in each study.20 The Wilcoxon sign-rank test was used to evaluate the differences in Brier Score between original and regional-calibrated original KFREs. An overall Brier Score was calculated using event-weighted means. The square-root of this overall score was reported as the root-mean-squared error between observed and predicted risk. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All tests were 2-sided. All analyses were performed using Stata MP 13 (College Station, TX).

Results

There were 721,357 CKD patients and 23,829 kidney failure events in 31 cohorts with an average follow-up time of 4.2 years (Table 1). A total of 16 cohorts (617,604 patients) were based in North America, and 15 cohorts (103,753 patients) were from Asia, Europe and Australasia. Missing data varied by cohort (median of 0%, 1%, and 41% for the 4-, 6-, and 8-variable equations; eAppendix 1). The amount of missing data was higher in North American cohorts (median missing for 4-variable, 6-variable, and 8-variable KFREs: 2%, 3%, 79%) than in non-North American cohorts (median missing: 0%, 1%, and 9%). All 31 cohorts had the variables necessary to validate the 4-variable KFREs, 29 cohorts had the variables necessary to validate the 6-variable KFREs, and 16 cohorts had the variables necessary to validate the 8-variable KFREs.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the participating cohorts

| Source | Cohort | Number of Participants |

F/U Time, years, Median (IQI) |

Age (years) |

Male, N (%) | Black ethnicity, N (%) |

eGFR (ml/min/ 1.73m2) (SD) |

Albuminuria, N (%)* |

Kidney Failure Events |

Kidney Failure Incidence (per 1000 py) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | AASK** | 898 | 8 (4, 10) | 55 (11) | 537 (60%) | 898 (100%) | 40 (12) | 592 (66%) | 303 | 47.3 |

| ARIC | 722 | 12 (7, 14) | 67 (5) | 332 (46%) | 171 (24%) | 50 (10) | 192 (27%) | 112 | 15.0 | |

| BC CKD** | 11,131 | 3 (2, 5) | 70 (13) | 6042 (54%) | 44 (0.4%) | 31 (11) | 7928 (71%) | 2,091 | 52.5 | |

| CCF ACR** | 4,102 | 2 (1, 4) | 71 (11) | 1950 (48%) | 747 (18%) | 48 (10) | 1643 (40%) | 101 | 10.4 | |

| CCF DIP** | 12,275 | 3 (1, 4) | 72 (13) | 5457 (44%) | 1579 (13%) | 46 (11) | 2835 (23%) | 300 | 10.3 | |

| CRIC** | 3,099 | 6 (4, 7) | 59 (11) | 1720 (56%) | 1315 (42%) | 40 (11) | 1866 (63%) | 796 | 49.4 | |

| Geisinger** | 20,720 | 4 (2, 6) | 70 (10) | 8605 (42%) | 211 (1%) | 51 (8) | 1961 (44%) | 453 | 4.9 | |

| ICES-KDT** | 100,569 | 4 (2, 6) | 73 (11) | 46883 (47%) | 0 (0%) | 46 (12) | 39611 (39%) | 3,093 | 7.0 | |

| KEEP | 16,425 | 4 (2, 6) | 69 (12) | 5338 (32%) | 3970 (24%) | 48 (10) | 3961 (33%) | 500 | 7.0 | |

| KPNW** | 1,486 | 5 (3, 6) | 73 (10) | 672 (45%) | 28 (2%) | 45 (11) | 478 (32%) | 100 | 15.3 | |

| MDRD** | 1,459 | 6 (3, 12) | 52 (13) | 891 (61%) | 166 (11%) | 33 (14) | 921 (85%) | 1,041 | 96.1 | |

| Mt Sinai BioMe** | 3,574 | 2 (1, 5) | 65 (13) | 1620 (45%) | 921 (26%) | 42 (14) | 970 (63%) | 525 | 47.7 | |

| Pima | 78 | 3 (1, 5) | 58 (14) | 23 (29%) | 0 (0%) | 36 (15) | 74 (95%) | 53 | 168.3 | |

| REGARDS | 3,158 | 7 (5, 8) | 72 (9) | 1402 (44%) | 1308 (41%) | 47 (11) | 1079 (36%) | 240 | 11.8 | |

| Sunnybrook** | 3,098 | 3 (2, 5) | 71 (14) | 1758 (57%) | 0 (0%) | 37 (13) | 1378 (75%) | 382 | 35.2 | |

| VA CKD | 434,810 | 4 (3, 4) | 75 (9) | 423521 (97%) | 38893 (9%) | 47 (11) | 14084 (41%) | 8,836 | 5.0 | |

| Sub-Total | 617,604 | 4 (3, 6) | 74 (10) | 506751 (82%) | 50251 (8%) | 46 (11) | 79573 (41%) | 18,926 | 7.5 | |

| Non-North America | CRIB** | 382 | 3 (1, 7) | 61 (14) | 248 (65%) | 22 (6%) | 21 (11) | 259 (84%) | 190 | 120.9 |

| GCKD | 3927 | 2 (2, 3) | 62 (11) | 2412 (61%) | 0 (0%) | 42 (10) | 2163 (56%) | 89 | 9.1 | |

| GLOMMS-1 | 1,007 | 4 (1, 6) | 71 (13) | 509 (51%) | 0 (0%) | 31 (9) | 701 (70%) | 122 | 31.2 | |

| Gonryo | 1,088 | 3 (1, 5) | 66 (13) | 652 (60%) | 0 (0%) | 32 (16) | 343 (95%) | 345 | 100.9 | |

| HUNT | 1,060 | 13 (6, 14) | 75 (8) | 393 (37%) | 0 (0%) | 49 (9) | 313 (30%) | 55 | 5.3 | |

| Maccabi | 58,630 | 5 (3, 6) | 73 (11) | 25820 (44%) | 0 (0%) | 49 (10) | 10938 (35%) | 1383 | 5.4 | |

| MASTERPLAN** | 579 | 6 (4, 6) | 61 (12) | 395 (68%) | 15 (3%) | 35 (12) | 314 (54%) | 134 | 45.1 | |

| MMKD | 140 | 4 (2, 5) | 49 (11) | 89 (64%) | 0 (0%) | 30 (15) | 133 (95%) | 70 | 131.3 | |

| NephroTest** | 1,317 | 3 (2, 6) | 61 (14) | 919 (70%) | 151 (11%) | 35 (13) | 857 (69%) | 292 | 55.4 | |

| NZDCS | 8,865 | 7 (4, 8) | 71 (11) | 3903 (44%) | 6 (0.07%) | 43 (15) | 1099 (15%) | 808 | 14.9 | |

| Okinawa83 | 1,698 | 17 (17, 17) | 69 (10) | 419 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 51 (8) | 599 (35%) | 55 | 1.9 | |

| Okinawa93 | 15,162 | 7 (7, 7) | 70 (10) | 4925 (32%) | 0 (0%) | 52 (7) | 1090 (7%) | 131 | 1.2 | |

| RENAAL**,† | 1,434 | 3 (2, 4) | 60 (7) | 890 (62%) | 199 (14%) | 37 (11) | 1434 (100%) | 335 | 82.7 | |

| Severance | 3,173 | 10 (9, 12) | 60 (10) | 1547 (49%) | 0 (0%) | 54 (7) | 384 (12%) | 92 | 2.9 | |

| SRR CKD** | 5,291 | 2 (1, 3) | 69 (14) | 3511 (66%) | 0 (0%) | 24 (9) | 4335 (82%) | 802 | 75.8 | |

| Sub-Total | 103,753 | 4 (3, 7) | 71 (12) | 46632 (45%) | 393 (0.4%) | 47 (12) | 24962 (34%) | 4,903 | 9.2 | |

| Overall Total | 721,357 | 4 (3, 7) | 74 (10) | 553383 (77%) | 50644 (7%) | 46 (11) | 104534 (40%) | 23,829 | 7.8 |

“Number of participants” indicates total N with data for the 3-variable equation.

Proportion of participants with urine albumin to creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g or urine protein to creatinine ratio ≥50 mg/g or dipstick protein ≥1+; proportion out of total number of participants with data for the 4-variable equation, this is listed in eAppendix 1.

Denotes cohorts that participated in the validation of the eight variable equation.

RENAAL contains participants from 28 countries, including United States and Canada. However, since the majority of participants stemmed from non-North American countries, the cohort was classified as non-North American.

Means (standard deviations) are presented except where specified otherwise. eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; IQI: interquartile interval. Kidney failure: treatment by dialysis or a kidney transplant.

Representative references for each cohort provided in eAppendix 3.

AASK: African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension. ARIC: Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. BC CKD: British Columbia CKD Study. CCF: Cleveland Clinic CKD Registry Study. CRIB: Chronic Renal Impairment in Birmingham. CRIC: Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study. GCKD: German Chronic Kidney Disease Study. Geisinger: Geisinger CKD Study. GLOMMS-1: GLOMMS-1: Grampian Laboratory Outcomes, Morbidity and Mortality Studies – 1. Gonryo: Gonryo Study. HUNT: Nord Trøndelag Health Study. ICES-KDT: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, Provincial Kidney, Dialysis and Transplantation program (ICES KDT). KEEP: Kidney Early Evaluation Program. KPNW: Kaiser Permanente Northwest. Maccabi: Maccabi Health System. MASTERPLAN: Multifactorial Approach and Superior Treatment Efficacy in Renal Patients with the Aid of a Nurse Practitioner. MDRD: Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study. MMKD: Mild to Moderate Kidney Disease Study. Mt. Sinai BioMe: Mount Sinai BioMe Biobank Platform. NephroTest: NephroTest Study. NZDCS: New Zealand Diabetes Cohort Study. Okinawa83: Okinawa 83 Cohort. Okinawa93: Okinawa 93 Cohort. Pima: Pima Indian Study. REGARDS: Reasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke Study. RENAAL: Reduction of Endpoints in Non-insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus with the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan. Severance: Severance Cohort Study. Sunnybrook: Sunnybrook Cohort. SRR-CKD: Swedish Renal Registry CKD Cohort. VA CKD: Veterans Administration CKD Study.

The mean age of the study population was 74 years, and the mean baseline eGFR was 46 ml/min/1.73 m2. Cohorts ranged from being predominantly male (Veterans Administration CKD, 97%) to majority female (Okinawa-83, 75%). Forty percent of the patients had diabetes, and 84% had hypertension (eTable 1). Forty percent of the study participants had a baseline urinary ACR ≥30 mg/g. The observed incidence of kidney failure ranged from 1.2 events per 1,000 person-years in Okinawa to 168.3 events per 1,000 person-years in the Pima Indian cohort. According to the original 4-variable KFRE, the proportion of each cohort who had a >20% 2-year predicted probability of kidney failure ranged from 0.23% (Okinawa93 cohort) to 50% (CRIB cohort).

Variable Coefficients in the Original and Pooled KFRE

In general, coefficients for the association between different characteristics (e.g. age, sex, eGFR, ACR) and the risk of kidney failure were similar in the original and pooled KFREs (Table 2). Exceptions were eGFR in the 4-variable equations (original vs. pooled: HR 0.57 vs. 0.63 per 5 ml/min/1.73 m2 higher eGFR) and serum bicarbonate in the 8-variable equations (0.93 vs. 0.99 per 1 mEq/L higher serum bicarbonate), both of which were stronger in the original KFRE.

Table 2.

Hazard ratios for kidney failure of the component variables in the original vs. pooled 4- and 8-variable equations

| Equation | Age per 10 years older |

Male sex | eGFR per 5 mL/min/ 1.73m2 |

ACR per log increase |

Calcium Per 1 mg/dl |

Phosphate Per 1 mg/dl |

Bicarbonate Per 1 mEq/L |

Albumin Per 1 g/dl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-Variable | ||||||||

| Original | 0.80 (0.75, 0.86) |

1.28 (1.04, 1.58) |

0.57 (0.54, 0.61) |

1.57 (1.44, 1.71) |

-- | -- | -- | -- |

| Pooled | 0.80 (0.76, 0.84) |

1.38 (1.29, 1.48) |

0.63* (0.60, 0.67) |

1.56 (1.47, 1.67) |

-- | -- | -- | -- |

| 8-Variable | ||||||||

| Original | 0.82 (0.77, 0.88) |

1.17 (0.95, 1.46) |

0.61 (0.58, 0.65) |

1.40 (1.28, 1.53) |

0.80 (0.68, 0.95) |

1.30 (1.18, 1.43) |

0.93 (0.90, 0.96) |

0.71 (0.56, 0.90) |

| Pooled | 0.83 (0.80, 0.86) |

1.34 (1.24, 1.44) |

0.66 (0.62, 0.70) |

1.42 (1.30, 1.54) |

0.85 (0.79, 0.93) |

1.17 (1.11, 1.24) |

0.99** (0.98, 1.00) |

0.70 (0.61, 0.80) |

Data presented are hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals).

eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate

ACR: urine albumin to creatinine ratio

Calcium, phosphate, bicarbonate and albumin values represent serum measures

Statistically significant differences between original and pooled estimates at * p<0.05;

p<0.001

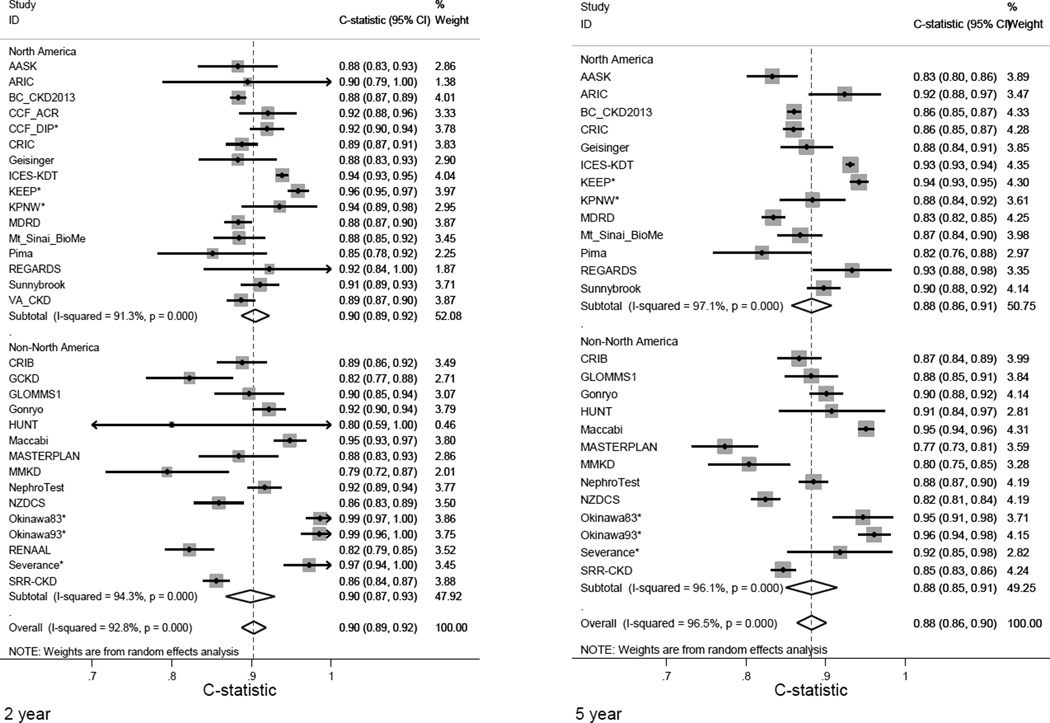

Discrimination

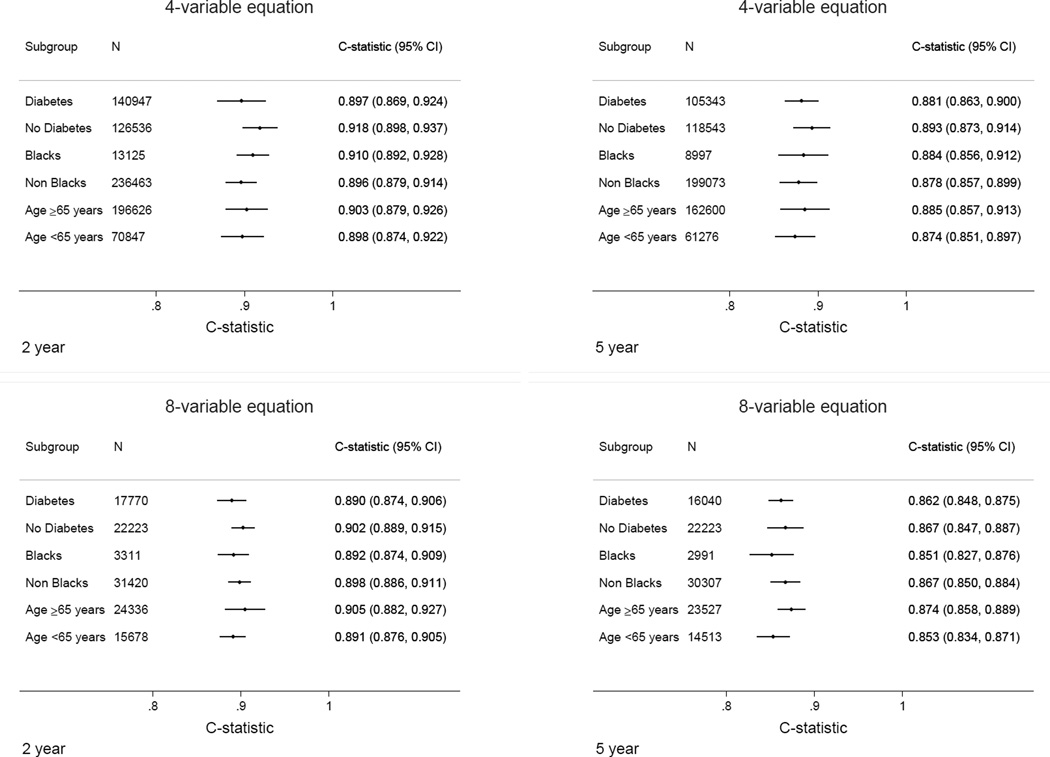

Measures of discrimination for the original 4-variable KFRE were excellent for the 2-year and 5-year predicted probability of kidney failure (Figure 1). Overall, the 4-variable equation had a pooled C statistic of 0.90 (95% CI 0.89–0.92) at 2 years, and 0.88 (95% CI 0.86–0.90) at 5 years. Within individual cohorts, discrimination was also excellent, with C statistic >0.80 in all but two cohorts (MMKD 2-year C statistic 0.79 (95% CI 0.72–0.87), MASTERPLAN 5-year C statistic 0.77 (95% CI 0.73–0.81). Discrimination for the original 8-variable KFRE was 0.89 (95% CI 0.88–0.91) at 2 years and 0.86 (95% CI 0.84–0.87) at 5 years (eFigure 1). In pre-specified subgroups of age, sex, race, region and diabetes status, discrimination was qualitatively unchanged, with C statistics for the 4-variable KFRE ranging from 0.90 to 0.92 for 2 years and 0.87 to 0.89 for 5 years (Figure 2). Similar statistics for the 6-variable equation are shown in eFigure 2.

Figure 1. Discrimination statistics (C statistics) for original 4-variable equation at 2 and 5 years by cohort.

An asterisk indicates this cohorts measuring dipstick proteinuria. Due to a limited number of events, confidence intervals were wide in some studies and therefore capped at 1.00 (maximum value for C statistic). Size is proportional to the weight of the study in a random effects meta-analysis. Arrows indicate that the true values are beyond the range of the axis. Representative references and expanded acronyms for each cohort name are provided in eAppendix 3.

Figure 2. Discrimination statistics (C statistics) for original 4-variable and 8-variable equations at 2 and 5 years by subgroup.

In the 4-variable equation analyses, 31 cohorts contributed for 2-year analysis and 26 cohorts for 5-year analysis. In the 8-variable equation analyses, 16 cohorts contributed for 2-year analysis and 11 cohorts contributed for 5-year analysis.

In general, the pooled 4-and 8-variable KFREs resulted in similar discrimination to the original KFREs (eTables 2–7). There was no significant difference in the overall C statistics of the pooled and the original KFREs (4-variable KFRE over 2 years: −0.0006, 95% CI −0.0020 −0.0008). When 2-year risk in all 31 cohorts was assessed individually, the pooled 4-variable KFRE performed significantly better than the original 4-variable KFRE in 5 cohorts, and in 5 cohorts it performed significantly worse (p<0.05 for each comparison).

Discrimination of the 8-variable KFRE was slightly better than the 4-variable KFRE in cohorts that had the necessary components for both equations (eTables 8 and 9). This was true using either the original KFRE or the pooled KFRE and in nearly all subgroups of interest.

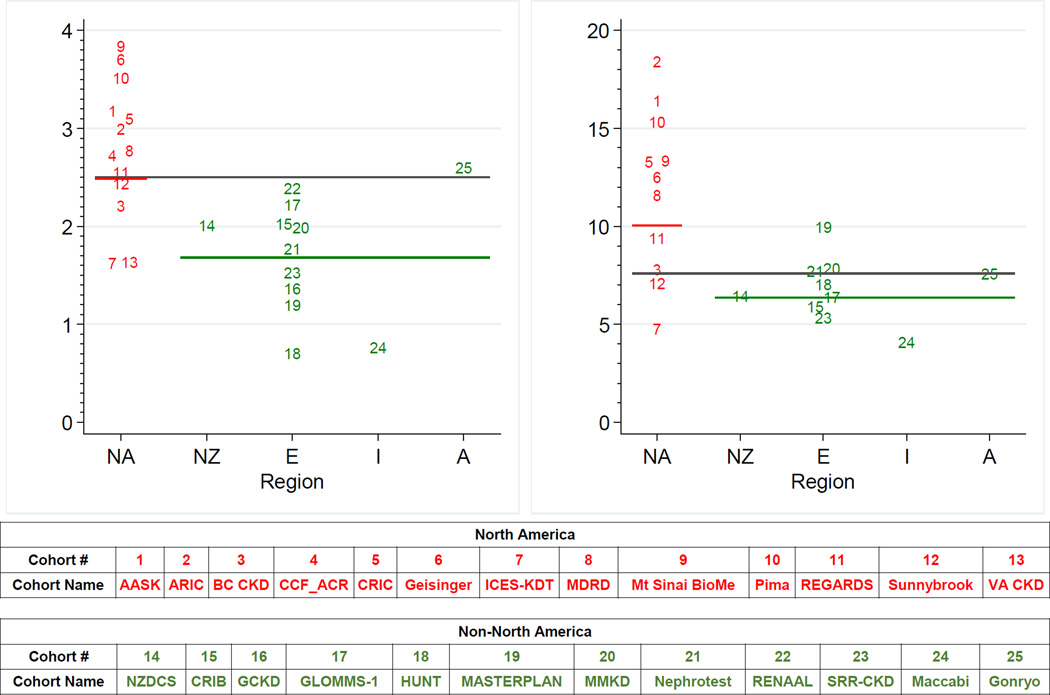

Calibration

Plots of the observed versus predicted risk demonstrated differences in calibration, with suboptimal performance in some of the non-North American cohorts (eFigures 3–6 for North American cohorts; eFigures 7–10 for non-North American cohorts). Baseline risk varied by region, with higher levels in North America compared with non-North America using the 4-variable equation (Figure 3). There was slightly less variation in baseline risk by region using the 8-variable equation (eFigure 11). In non-North American studies, use of a regional calibration factor that lowered the baseline risk by 32.9% at 2 years and 16.5% at 5 years decreased the root mean-squared distance of the observed to expected risk from 0.237 to 0.228 at 2 years and 0.299 to 0.287 at 5 years for the 4-variable equation and improved performance in 12 out of 15 studies at 2 years (p=0.04) and 10 out of 13 studies at 5 years (p=0.02) (eTable 10). In contrast, use of a regional calibration factor in North American cohorts, the region where the KFREs were developed, did not significantly improve performance. For example, the root mean-squared distance of the observed to expected risk at 2 years only minimally changed from 0.152 to 0.151 with the addition of the calibration factor and increased from 0.264 to 0.272 at 5 years for the 4-variable equation. eAppendix 2 shows all equations.

Figure 3. Refit baseline hazard of original 4-variable equation at 2 and 5 years in individual cohorts stratified by region.

Horizontal gray line represents the centered baseline hazard for the original 4-variable KFRE (age 70 years, male 56%, eGFR 36 ml/min/1.73 m2, ACR 170 mg/g); the red and green horizontal line represent the weighted mean refit baseline hazard within each region (North America and non-North America). NA: North America, NZ: New Zealand, E: Europe, I: Israel, A: Asia. The 25 cohorts included represent studies with available urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio. Studies with dipstick proteinuria were not included in the calculation. The North America cohorts include AASK, ARIC, BC CKD, CCF_ACR, CRIC, Geisinger, ICES-KDT, MDRD, Mt Sinai BioMe, Pima, REGARDS, Sunnybrook, and VA CKD. The New Zealand cohort is NZDCS. The Europe cohorts include CRIB, GCKD, GLOMMS-1, HUNT, MASTERPLAN, MMKD, Nephrotest, RENAAL, and SRR-CKD. The Israel cohort is Maccabi. The Asia cohort is Gonryo.

Discussion

In this collaborative meta-analysis of 721,357 patients, across 31 cohorts and over 30 countries, the KFREs accurately predict the 2-year and 5-year probability of kidney failure in patients with CKD with a wide range of variation in age, sex, race, and in the presence or absence of diabetes.

The original equations reported by Tangri et al demonstrated excellent discrimination and appropriate calibration in the majority of the North American cohorts, and addition of a recalibration factor optimized performance in non-North American populations. The 4-variable KFRE (age, sex, eGFR, and albuminuria) can be easily implemented in electronic medical records and laboratory information systems. The use of this equation is consistent with the KDIGO guideline which recommends integration of risk prediction in the evaluation and management of CKD,21 and is in agreement with a strong body of evidence demonstrating the importance of eGFR and albuminuria in predicting prognosis.13,15,22–35

Previous investigators developed alternative risk prediction models for progression of CKD to kidney failure,36 but most have not been externally validated. The KFREs developed by Tangri et al were externally validated in a cohort of Canadian CKD patients referred for nephrology care, but their accuracy in non-referred patients and regions outside Canada remained unknown. Thus, current clinical practice guidelines recommended the use of KFREs for predicting prognosis and planning dialysis access, but with appropriate caution regarding their external validity.37 The current validation study addresses these concerns, and more widespread clinical assessment of the KFREs can now be recommended. Similar to previous work, an incremental improvement in performance was observed with an 8-variable KFRE, which additionally includes serum albumin, phosphate, bicarbonate, and calcium levels over the 4-variable KFRE. The magnitude of improvement was smaller than in the original study, but may be meaningful for patients where data for both equations is readily available. These findings suggest that the 4-variable KFRE might be adopted more widely, but the 8-variable KFRE should be made available if the additional variables are obtained and increased precision is desired.

The risk associations observed in the pooled validation sample were similar to those in the original KFRE. In particular, younger age, male sex, lower eGFR and higher albuminuria were associated with a higher risk of kidney failure defined by treatment with dialysis or transplant. The finding of lower risk of kidney failure with older age is consistent with the previous literature25 and is likely due to a combination of factors: 1) the same disease process (e.g., diabetic nephropathy in a patient with type 1 diabetes with age of diagnosis at 15 years) is more likely to be indolent, if the patient has an eGFR of 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 at age 75 (60 years of exposure) vs. age 45 (30 years of exposure); 2) as patients age, they are more likely to die from a competing cause (malignancy, cardiovascular disease) than reach kidney failure; and 3) older patients may be more likely to choose conservative care for kidney failure rather than treatment with dialysis or transplant, our primary outcome.38 It is important to note that in the original development of the KFRE,6 competing risk models were evaluated and a threshold of eGFR of <10 ml/min/1.73 m2 was tested as a secondary outcome; no differences in the performance of the KFREs was observed.

Although recalibration was not needed in most North American cohorts, adding a regional calibration factor in non-North American cohorts improved calibration and would allow the KFREs to be used clinically in countries with different levels of baseline risk. This is similar to the Framingham Study Equation, which is used for estimating cardiovascular risk and has been recalibrated for use in multiple different populations.19 Differences in baseline risk between cohorts and regions may reflect different cohort inclusion criteria, or treatment preferences for kidney failure rather than physiological differences in disease progression, since risk relationships between the risk factors and kidney failure were fairly uniform across settings. Further studies examining additional causes of heterogeneity in higher vs. lower risk populations are needed.

There are important clinical and research implications to this study’s findings. Clinicians can now use the 4- or 8-variable KFRE, with the recalibration factor where applicable, and inform patient-clinician communication and treatment decisions around the absolute risk of kidney failure, rather than the CKD Stage alone. Decisions regarding access placement or transplant referral could be made once kidney failure risk thresholds are exceeded. Some kidney failure risk thresholds have been proposed on the basis of physician surveys and decision analyses (>3 or 5% risk for 5 years for nephrology referral, >20 or 40% risk over 2 years for vascular access planning), and should be evaluated further in cluster randomized trials or time series analyses. Routine reporting and clinical implementation is already underway in several centers, and its impact on patient care and health services is being studied. From a research perspective, the KFRE can be used to estimate event rates and statistical power for kidney failure outcomes in clinical trials, and may be useful in selecting higher-risk patients for trial inclusion and identifying risk-treatment interactions.39,40

This study has limitations. First, the KFRE does not assess kidney failure risk in patients with CKD Stages G1 (GFR ≥90 ml/min/1.73m2) and G2 (GFR 60–89 ml/min/1.73m2). Previous studies have shown that patients with Stages G1–2 and high levels of albuminuria should be considered as high risk. Second, due to the variables required, validation of the 8-variable equation was not possible in all cohorts. Therefore, nested comparisons between equations are limited to a subset. In some cohorts, proteinuria was converted to albuminuria, and although no meaningful differences in discrimination were observed in these populations, it is possible that risk relationships may differ slightly for the two measures. Furthermore, even with the inclusion of more than 700,000 participants in over 30 countries, there was not significant representation from countries where there is limited access to renal replacement therapy. Validation in these countries with a combined endpoint of treated and untreated kidney failure should be performed. Third, there were missing data, particularly in the North American health systems. Missing data reduces the generalizability of our findings to North American health systems. While this generalizability applies to the hypothetical world of all patients, the results do reflect participants as they would be used in clinical health systems. Furthermore, KFRE performance was similar in health system and research cohorts. Fourth, the risk equations provide the risk of kidney failure over 2 and 5 years. These timeframes are important for decisions regarding nephrology referral, dialysis access planning and pre-emptive transplantation (i.e., kidney transplant prior to receiving dialysis), but they do not capture longer-term risk of kidney failure, which may impact other clinical decisions such as lifestyle modification.41 Fifth, the KFRE incorporates routinely collected laboratory data. Accuracy of risk predictions may be enhanced in specific subpopulations by novel biomarkers of CKD; however, the incremental gain in predictive accuracy may not be justified by the cost of these newer assays for the entire CKD population.42 Sixth, there is no evidence that using the equation will improve outcomes. Well-designed pragmatic randomized trials are needed to definitively establish the evidence for efficacy.

Strengths of this study include the large patient population, and accompanying diversity in age, sex, race and etiology of kidney disease. In North America, the 4-variable original KFRE appears generalizable and highly accurate in most cohorts and can be easily implemented across multiple health care systems. Elsewhere, the recalibrated KFRE appears more accurate, and can also be integrated into healthcare platforms. Partnerships with mobile technology developers and health care systems may ensure that knowledge translation occurs without long delays, which are common in biomedical research.

Conclusions

KFREs developed in a Canadian population showed high discrimination and adequate calibration when validated in 31 multinational cohorts. However, in some regions the addition of a calibration factor may be necessary.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The CKD-PC Data Coordinating Center is funded in part by a program grant from the US National Kidney Foundation (NKF funding sources include AbbVie, Amgen, and Merck) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK100446-01). A variety of sources have supported enrollment and data collection including laboratory measurements, and follow-up in the collaborating cohorts of the CKD-PC. These funding sources include government agencies such as national institutes of health and medical research councils as well as foundations and industry sponsors listed in eAppendix 4. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Some of the data reported here have been supplied by the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the U.S. government.

Appendix

CKD-PC investigators/collaborators (study acronyms/abbreviations are listed in eAppendix 3):

AASK: Jackson T. Wright, Jr, MD, PhD, Case Western Reserve University, United States; Lawrence J. Appel, MD, MPH, Johns Hopkins University, United States; Tom Greene, PhD, University of Utah, United States; Brad C. Astor, PhD, MPH, University of Wisconsin, United States; ARIC: Josef Coresh, MD, PhD, Johns Hopkins University, United States; Kunihiro Matsushita, MD, PhD, Johns Hopkins University, United States; Morgan E. Grams, MD, PhD, Johns Hopkins University, United States; Yingying Sang, MS, Johns Hopkins University, United States; British Columbia CKD: Adeera Levin, MD, FRCPC, BC Provincial Renal Agency and University of British Columbia, Canada; Ognjenka Djurdjev, MSc, BC Provincial Renal Agency and Provincial Health Services Authority, Canada; CCF: Sankar D Navaneethan, MD, MPH, Cleveland Clinic, United States; Joseph V Nally, Jr, MD, Cleveland Clinic, United States; Jesse D Schold, PhD, Cleveland Clinic, United States; CRIB: David C Wheeler, MD, FRCP, University College London, United Kingdom; Jonathan Emberson, PhD, University of Oxford, United Kingdom; Jonathan N Townend, MD, FRCP, Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, United Kingdom; Martin J Landray, PhD, FRCP, University of Oxford, United Kingdom; CRIC: Lawrence J. Appel, MD, MPH, Johns Hopkins University, United States; Harold Feldman, MD, MsCE, University of Pennsylvania, United States; Chi-yuan Hsu, MD, MSc, University of California-San Francisco, United States; GCKD: Kai-Uwe Eckardt, MD, University of Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany; Anna Kottgen, MD, MPH, University of Freiburg, Germany; Florian Kronenberg, MD, Medical University of Innsbruck, Austria; Stephanie Titze, MD, MSc, University of Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany; Geisinger: Jamie Green, MD, MS, Geisinger Medical Center, United States; H Lester Kirchner, PhD, Geisinger Medical Center, United States; Robert Perkins, MD, Geisinger Medical Center, United States; Alex R Chang, MD, MS, Geisinger Medical Center, United States; GLOMMS-1 Study: Corri Black, MBChB, MRCP, MSc, MFPH, FFPH, University of Aberdeen, United Kingdom; Angharad Marks, MBBCh, MRCP, MSc, PhD, University of Aberdeen, United Kingdom; Nick Fluck, BSc, MBBC, DPhil, FRCP, NHS Grampian, Aberdeen, United Kingdom; Dr Laura Clark MBChB, MD, MRCP, NHS Grampian, Aberdeen; Gordon J Prescott, BSc, MSc, PhD, CStat, University of Aberdeen, United Kingdom; Gonryo: Sadayoshi Ito, MD, PhD, Tohoku University School of Medicine, Japan; Mariko Miyazaki, MD, Tohoku University School of Medicine, Japan; Masaaki Nakayama, MD, Fukushima Medical University and Tohoku University School of Medicine, Japan; Gen Yamada, MD, Tohoku University School of Medicine, Japan; HUNT: Stein Hallan, MD, PhD, Norwegian University of Science and Technology and St Olav University, Norway; Knut Aasarød, MD, PhD, Norwegian University of Science and Technology and St Olav University Hospital, Norway; Solfrid Romundstad, MD, PhD, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway; Kaiser Permanente NW: David H Smith, RPh, PhD, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, United States; Micah L Thorp, DO, MPH, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, United States; Eric S Johnson, PhD, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, United States; KEEP: Allan J. Collins, MD, Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation and University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, United States; Shu-Cheng Chen, MS, MPH, Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation, United States; Suying Li, PhD, Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation, United States; Maccabi: Gabriel Chodick, PhD, Maccabi Healthcare Services, Israel; Varda Shalev, MD, Maccabi Healthcare Services and Tel Aviv University, Israel; Nachman Ash, MD, Maccabi Healthcare Services, Israel; Bracha Shainberg, PhD, Maccabi Healthcare Services, Israel; MASTERPLAN: Jack F. M. Wetzels, MD, PhD, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands; Peter J Blankestijn, MD, PhD, University Medical Center Utrecht, The Netherlands; Arjan D van Zuilen, MD, PhD University Medical Center Utrecht, The Netherlands; MDRD: Mark J Sarnak, MD, MS, Tufts Medical Center, United States; Andrew S Levey, MD, Tufts Medical Center, United States; Lesley A Inker, MD, MS, Tufts Medical Center, United States; Vandana Menon, MD, PhD, Tufts Medical Center, United States; MMKD: Florian Kronenberg, MD, Medical University of Innsbruck, Austria; Barbara Kollerits, PhD, MPH, Medical University of Innsbruck, Austria; Eberhard Ritz, MD, Ruprecht-Karls-University, Germany; Mt. Sinai BioMe: Girish N Nadkarni, MD, MPH, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, United States; Erwin P Bottinger, MD, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, United States; Stephen B Ellis, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, United States; Rajiv Nadukuru, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, United States; NephroTest: Marc Froissart, MD, PhD, Paris Descartes University, France; Benedicte Stengel, MD, PhD, Inserm U1018 and University of Paris Sud-11, France; Marie Metzger, PhD, Inserm U1018 and University of Paris Sud-11, France; Jean-Philippe Haymann, MD, PhD, Sorbonne Universités, UPMC Univ Paris 06, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, France; Pascal Houillier, MD, PhD, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Paris Descartes University, France; Martin Flamant, MD, PhD, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, France; NZDCS: C Raina Elley, MBCHB, PhD, University of Auckland, New Zealand; Timothy Kenealy, MBCHB, PhD, University of Auckland, New Zealand; Simon A Moyes, MSc, University of Auckland, New Zealand; John F Collins, MBCHB, Auckland District Health Board, New Zealand; Paul L Drury, MA, MB, BCHIR, Auckland District Health Board, New Zealand; Okinawa 83/93: Kunitoshi Iseki, MD, University Hospital of the Ryukyus, Japan; ICES-KDT: Amit X Garg, MD, PhD, Western University and Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences Kidney, Dialysis and Transplantation Program, Canada; Eric McArthur, MSc, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences Kidney, Dialysis and Transplantation Program, Canada; Gihad Nesrallah, MD, MSc, Humber Regional Hospital, Keenan Research Centre, St. Michael’s Hospital, and Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences Kidney, Dialysis and Transplantation Program, Canada; S Joseph Kim, MD, PhD, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences Kidney, Dialysis and Transplantation Program, Canada; Pima Indian: Robert G. Nelson, MD, PhD, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, United States; William C. Knowler MD, DrPH, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, United States; REGARDS: David G Warnock, MD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States; Paul Muntner, PhD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States; Suzanne Judd, PhD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States; William McClellan, MD, MPH, Emory University, United States; Orlando Gutierrez, MD, MMSc, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States; RENAAL: Hiddo J Lambers Heerspink, PharmD, PhD, University of Groningen, The Netherlands; Barry E Brenner, MD, PhD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard School of Medicine, United States; Dick de Zeeuw, MD, PhD, University of Groningen, The Netherlands; Severance: Sun Ha Jee, PhD, Yonsei University, Republic of Korea; Heejin Kimm, MD, PhD, Yonsei University, Republic of Korea; Yejin Mok, MPH, Yonsei University, Republic of Korea; SRR-CKD: Marie Evans, MD, PhD, Karolinska Institutet and Swedish Renal Registry, Sweden; Maria Stendahl, Swedish Renal Registry and Hospital of Ryhov, Sweden; Sunnybrook: Navdeep Tangri, MD, PhD, FRCPC, University of Manitoba, Canada; Maneesh Sud, MD, University of Toronto, Canada; David Naimark, MD, MSc, FRCPC, University of Toronto, Canada; VA CKD: Csaba P Kovesdy, MD, Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center and University of Tennessee Health Science Center, United States; Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh, MD, MPH, PhD, University of California Irvine Medical Center, United States;

CKD-PC Steering Committee: Josef Coresh (Chair), MD, PhD, Johns Hopkins University, United States; Ron T Gansevoort, MD, PhD, University Medical Center Groningen, The Netherlands; Morgan E Grams, MD, PhD, Johns Hopkins University, United States; Paul E de Jong, MD, PhD, University Medical Center Groningen, The Netherlands; Kunitoshi Iseki, MD, University Hospital of the Ryukyus, Japan; Andrew S Levey, MD, Tufts Medical Center, United States; Kunihiro Matsushita, MD, PhD, Johns Hopkins University, United States; Mark J Sarnak, MD, MS, Tufts Medical Center, United States; Benedicte Stengel, MD, PhD, Inserm U1018 and University of Paris Sud-11, France; David Warnock, MD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States; Mark Woodward, PhD, George Institute, Australia

CKD-PC Data Coordinating Center: Shoshana H Ballew (Coordinator), PhD, Johns Hopkins University, United States; Josef Coresh (Principal investigator), MD, PhD, Johns Hopkins University, United States; Morgan E Grams (Director of Nephrology Initiatives), MD, PhD, Johns Hopkins University, United States; Kunihiro Matsushita (Director), MD, PhD, Johns Hopkins University, United States; Yingying Sang (Lead programmer), MS, Johns Hopkins University, United States; Mark Woodward (Senior statistician), PhD, George Institute, Australia

Footnotes

JC had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Contributors: NT, ASL, MG, JC, MJS, BS, MW, and KI conceived of the study concept and design. MG, JC, MW, and the CKD-PC investigators/collaborators listed below acquired the data. MW and the Data Coordinating Center members listed below analyzed the data. JC had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis and all authors had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication, informed by discussions with collaborators. NT, ASL, MG, JC, MW, and KI drafted the manuscript, and LA, BCA, GC, AJC, OD, CRE, ME, AG, SIH, LI, SI, CPK, FK, HJLH, AM, SDN, RGN, ST, MJS, and BS provided critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All collaborators shared data and were given the opportunity to comment on the manuscript. JC obtained funding for CKD-PC and individual cohort and collaborator support is listed in appendix.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007 Nov 7;298(17):2038–2047. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Hare AM, Batten A, Burrows NR, et al. Trajectories of kidney function decline in the 2 years before initiation of long-term dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012 Apr;59(4):513–522. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004 Sep 23;351(13):1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Hare AM, Bertenthal D, Walter LC, et al. When to refer patients with chronic kidney disease for vascular access surgery: should age be a consideration? Kidney Int. 2007 Mar;71(6):555–561. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tobe SW, Clase CM, Gao P, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with telmisartan, ramipril, or both in people at high renal risk: results from the ONTARGET and TRANSCEND studies. Circulation. 2011 Mar 15;123(10):1098–1107. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.964171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tangri N, Stevens LA, Griffith J, et al. A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA. 2011 Apr 20;305(15):1553–1559. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tonelli M, Manns B. Supplementing creatinine-based estimates of risk in chronic kidney disease: is it time? JAMA. 2011 Apr 20;305(15):1593–1595. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drawz PE, Goswami P, Azem R, Babineau DC, Rahman M. A simple tool to predict end-stage renal disease within 1 year in elderly adults with advanced chronic kidney disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013 May;61(5):762–768. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peeters MJ, van Zuilen AD, van den Brand JA, Bots ML, Blankestijn PJ, Wetzels JF. Validation of the kidney failure risk equation in European CKD patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013 Jul;28(7):1773–1779. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Acedillo RR, Tangri N, Garg AX. The kidney failure risk equation: on the road to being clinically useful? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013 Jul;28(7):1623–1624. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marks A, Fluck N, Prescott GJ, et al. Looking to the future: predicting renal replacement outcomes in a large community cohort with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015 Sep;30(9):1507–1517. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elley CR, Robinson T, Moyes SA, et al. Derivation and validation of a renal risk score for people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013 Oct;36(10):3113–3120. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, et al. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010 Jun 12;375(9731):2073–2081. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60674-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009 May 5;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsushita K, Mahmoodi BK, Woodward M, et al. Comparison of risk prediction using the CKD-EPI equation and the MDRD study equation for estimated glomerular filtration rate. JAMA. 2012 May 9;307(18):1941–1951. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Expressing the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Equation for Estimating Glomerular Filtration Rate with Standardized Serum Creatinine Values. Clin Chem. 2007 Apr 1;53(4):766–772. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.077180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parving HH, Lehnert H, Brochner-Mortensen J, et al. The effect of irbesartan on the development of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001 Sep 20;345(12):870–878. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grams ME, Li L, Greene TH, et al. Estimating time to ESRD using kidney failure risk equations: results from the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) Am J Kidney Dis. 2015 Mar;65(3):394–402. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D'Agostino RB, Sr, Grundy S, Sullivan LM, Wilson P. Validation of the Framingham coronary heart disease prediction scores: results of a multiple ethnic groups investigation. JAMA. 2001 Jul 11;286(2):180–187. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brier G. Verification of forecasts expressed in terms of probability. Monthly Weather Review. 1950;78:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Chapter 5: Referral to specialists and models of care. Kidney International Supplements. 2013;3(1):112–119. doi: 10.1038/kisup.2012.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Astor BC, Matsushita K, Gansevoort RT, et al. Lower estimated glomerular filtration rate and higher albuminuria are associated with mortality and end-stage renal disease. A collaborative meta-analysis of kidney disease population cohorts. Kidney Int. 2011 Jun;79(12):1331–1340. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Velde M, Matsushita K, Coresh J, et al. Lower estimated glomerular filtration rate and higher albuminuria are associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. A collaborative meta-analysis of high-risk population cohorts. Kidney Int. 2011 Jun;79(12):1341–1352. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gansevoort RT, Matsushita K, van der Velde M, et al. Lower estimated GFR and higher albuminuria are associated with adverse kidney outcomes in both general and high-risk populations. A collaborative meta-analysis of general and high-risk population cohorts. Kidney Int. 2011 Jul;80(1):93–104. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hallan SI, Matsushita K, Sang Y, et al. Age and Association of Kidney Measures With Mortality and End-stage Renal Disease. JAMA. 2012 Oct 30;308(22):2349–2360. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.16817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahmoodi BK, Matsushita K, Woodward M, et al. Associations of kidney disease measures with mortality and end-stage renal disease in individuals with and without hypertension: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;380(9854):1649–1661. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61272-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fox CS, Matsushita K, Woodward M, et al. Associations of kidney disease measures with mortality and end-stage renal disease in individuals with and without diabetes: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;380(9854):1662–1673. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61350-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nitsch D, Grams ME, Sang Y, et al. Associations of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with mortality and renal failure by sex: a meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f324. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shlipak MG, Matsushita K, Arnlov J, et al. Cystatin C versus creatinine in determining risk based on kidney function. N Engl J Med. 2013 Sep 5;369(10):932–943. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wen CP, Matsushita K, Coresh J, et al. Relative risks of chronic kidney disease for mortality and end-stage renal disease across races are similar. Kidney Int. 2014 Oct;86(4):819–827. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coresh J, Turin TC, Matsushita K, et al. Decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate and subsequent risk of end-stage renal disease and mortality. JAMA. 2014 Jun 25;311(24):2518–2531. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.6634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grams ME, Sang Y, Ballew SH, et al. A Meta-analysis of the Association of Estimated GFR, Albuminuria, Age, Race, and Sex With Acute Kidney Injury. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015 Oct;66(4):591–601. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.02.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.James MT, Grams ME, Woodward M, et al. A Meta-analysis of the Association of Estimated GFR, Albuminuria, Diabetes Mellitus, and Hypertension With Acute Kidney Injury. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015 Oct;66(4):602–612. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.02.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsushita K, Coresh J, Sang Y, et al. Estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria for prediction of cardiovascular outcomes: a collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015 Jul;3(7):514–525. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00040-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grams ME, Sang Y, Levey AS, et al. Kidney-Failure Risk Projection for the Living Kidney-Donor Candidate. N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 6; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tangri N, Kitsios GD, Inker LA, et al. Risk prediction models for patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013 Apr 16;158(8):596–603. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney International Supplements. 2013;3(1):1–150. doi: 10.1016/j.kisu.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hemmelgarn BR, James MT, Manns BJ, et al. Rates of treated and untreated kidney failure in older vs younger adults. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2507–2515. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fried LF, Emanuele N, Zhang JH, et al. Combined Angiotensin inhibition for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2013 Nov 14;369(20):1892–1903. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Zeeuw D, Akizawa T, Audhya P, et al. Bardoxolone methyl in type 2 diabetes and stage 4 chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2013 Dec 26;369(26):2492–2503. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turin TC, Tonelli M, Manns BJ, et al. Lifetime risk of ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012 Sep;23(9):1569–1578. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012020164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Isakova T, Xie H, Yang W, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and risks of mortality and end-stage renal disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. JAMA. 2011 Jun 15;305(23):2432–2439. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.