Abstract

Introduction

The Geriatric Resources for the Assessment and Care of Elders (GRACE) program has been shown to decrease acute care utilization and increase patient self-rated health in low-income seniors at community-based health centers.

Aims

To describe adaptation of the GRACE model to include adults of all ages (named Care Support) and to evaluate the process and impact of Care Support implementation at an urban academic medical center.

Setting

152 high-risk patients (≥5 ED visits or ≥2 hospitalizations in the past 12 months) enrolled from four medical clinics from 4/29/2013 to 5/31/2014.

Program Description

Patients received a comprehensive in-home assessment by a nurse practitioner/social worker (NP/SW) team, who then met with a larger interdisciplinary team to develop an individualized care plan. In consultation with the primary care team, standardized care protocols were activated to address relevant key issues as needed.

Program Evaluation

A process evaluation based on the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research identified key adaptations of the original model, which included streamlining of standardized protocols, augmenting mental health interventions and performing some assessments in the clinic. A summative evaluation found a significant decline in the median number of ED visits (5.5 to 0, p = 0.015) and hospitalizations (5.5 to 0, p<0.001) 6 months before enrollment in Care Support compared to 6 months after enrollment. In addition, the percent of patients reporting better self-rated health increased from 31% at enrollment to 64% at 9 months (p = 0.002). Semi-structured interviews with Care Support team members identified patients with multiple, complex conditions; little community support; and mild anxiety as those who appeared to benefit the most from the program.

Discussion

It was feasible to implement GRACE/Care Support at an academic medical center by making adaptations based on local needs. Care Support patients experienced significant reductions in acute care utilization and significant improvements in self-rated health.

Introduction

‘Complex care’ refers to patients with health care needs that are complicated by significant medical and psychosocial factors, such as multiple chronic conditions and comorbid physical and mental health conditions.[1, 2] Patients with complex care needs are a major driver of health care costs, with 10% of patients accounting for 64% of total health care costs.[3, 4]

The Geriatric Resources for the Assessment and Care of Elders (GRACE) program is a health care delivery model that was developed to improve care while controlling costs for older patients with complex care needs.[5] GRACE was designed to serve as a support system between patients/caregivers and the primary care provider (PCP). The model includes a nurse practitioner/social worker (NP/SW) team that performs comprehensive, structured assessments in patients’ homes and then meets as part of a larger interdisciplinary team that includes a geriatrician, mental health liaison and pharmacist. The driver of GRACE Team Care is an individualized care plan developed by the GRACE team based on the initial in-home assessment and the patient’s goals of care. The care plan is built using the GRACE Protocols for common geriatric conditions. A few of the GRACE Protocols are Cognitive Impairment, Difficulty Walking/Falls, Health Maintenance, and Advance Care Planning. These care protocols and corresponding Team Suggestions for evaluation and management are a combination of medical and psychosocial interventions and based on published practice guidelines. The GRACE Protocols provide a checklist to ensure a standardized and state-of-the-art approach to care. The GRACE Team works alongside the patient’s primary care team to implement the care plan and modify it as needed over time. Additional information is available on the GRACE Team Care website: http://graceteamcare.indiana.edu/home.html.

In a randomized, controlled trial, patients at high risk for hospital admission who received GRACE team care versus a ‘usual care’ control group had decreased healthcare utilization and healthcare costs; improved quality of care; increased patient and provider satisfaction; and improved quality of life.[6, 7]

The primary objective of the current study was to evaluate the adaptation and implementation of GRACE at an urban academic medical center. Our evaluation was informed by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) and was performed as a partnership among clinical and research teams.[8] We performed a process evaluation to assess fidelity to the original program, adaptations for the current environment, and barriers and facilitators encountered. As described in detail below, one of the key adaptations was to include adult patients 18 years and older who met enrollment criteria; therefore, the program was renamed Care Support to reflect this more inclusive age range. We also performed a summative evaluation to examine the impact of implementation on health care utilization and patient quality of life.

Methods

Setting and Patient Population

The setting for this implementation study was four primary care medical clinics at a large urban academic medical center. Within each clinic, ‘high-risk’ patients—defined as patients with ≥5 emergency department (ED) visits or ≥2 inpatient hospitalizations in the past 12 months—were identified based on lists of recent admissions and direct referrals. These high-utilizing patients were then vetted by PCPs for appropriateness of enrollment taking into consideration the patients’ needs, current resources and potential for engagement. For example, PCPs may have decided that Care Support was not necessary for patients whose high utilization was appropriate for their medical condition and were already well-supported, who were connected with another team providing aggressive care management, or who were rapidly declining and unlikely to benefit. Patients who were approved by their PCPs were placed on the Care Support Registry. To target enrollment to those patients with persistent high utilization, after their next ED visit or hospitalization, PCPs were asked to contact patients directly to assess their interest in participating in Care Support. Patients who agreed were then contacted by the Care Support team to schedule an initial in-home assessment by the NP/SW team.

This study was approved by the UCSF Institutional Review Board (IRB). Because our study involved retrospective review of data that had been previously collected as part of clinical care and quality improvement, patient informed consent and HIPAA authorization were waived. The UCSF IRB approved release of a limited dataset for this publication, which is included as supplementary information (S1 Appendix). To minimize the risk of loss of privacy for older patients, age has been truncated to a maximum value of 89 years. We do not have IRB approval to provide specific ages for patients age 90 years or older.

Overview of Care Support

At the initial in-home assessment, the NP/SW team performed a comprehensive evaluation of the patient’s needs and available resources. In some cases, the initial assessment was performed in the clinic or by phone if the patient declined the in-home assessment. The initial assessment was then discussed with the larger interdisciplinary team that included a geriatrician, mental health liaison and pharmacist. An individualized care plan was created for each patient that included activation of specific care protocols, which were then reviewed and modified as needed by the primary care physician. Follow-up visits were typically conducted by phone unless a follow-up home visit was deemed critical to the patient’s ongoing well-being. Patients continued to receive regular telephone contacts as needed and were discussed at interdisciplinary team meetings on a quarterly basis or more frequently if needed. After hours support was provided by the primary care team.

Process Evaluation

Patients, Process and Fidelity

A dedicated Care Support database included information gathered by the NP/SW team at the initial home assessment, such as patient demographic information, insurance status, falls, housing status, depressive symptoms (PHQ-4),[9] and dependency in basic and instrumental activities of daily living (ADL/IADL).[10, 11] Data also were collected on process measures including time between key milestone events (e.g., patient enrollment and initial home assessment); number and type of protocols recommended; and number of face-to-face and telephone patient contacts over time. Additional data on diagnoses and use of alcohol and tobacco were assessed by the clinical team from the electronic medical record. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the patient population, implementation process and fidelity to the original GRACE model. In addition, age groups (<65 vs. ≥65 years) were compared using t-tests, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests or Chi-square tests as appropriate.

Adaptations, Barriers and Facilitators

Semi-structured group and individual interviews were performed with Care Support team members in July 2014, approximately 14 months after the first patient had been enrolled. Interview questions were based on the CFIR conceptual model and focused on identifying adaptations to the original GRACE model and barriers and facilitators to implementation. In addition, team members were asked to reflect on the characteristics of patients that appeared to benefit the most and the least from participation in the program. One investigator who was not part of the clinical team (DB) took detailed notes and performed a thematic analysis which was then reviewed and confirmed by clinical team members.

Summative Evaluation

Health care Utilization

Utilization data including dates of ED visits and hospital admissions for Care Support patients both 6 months prior to enrollment and 6 months after enrollment were extracted from the electronic medical record. Length of stay during hospital admissions was also determined. Given differential dates of enrollment and lengths of follow-up, we calculated ED and hospitalization rates per 1,000 observation days. Because the distributions were highly skewed, we compared pre- and post-enrollment rates using non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. In addition, we compared the proportions of patients with zero ED visits or hospitalizations pre- and post-enrollment using McNemar’s test. Analyses of health care utilization were restricted to patients with >25 days of follow-up to ensure that the median number of observation days was similar during the pre- and post-enrollment observation periods. Patients also were asked about ED visits and hospital admissions outside UCSF at the initial home assessment and every 3 months thereafter (see below).

Patient Self-Rated Health

The NP/SW team assessed patient self-rated health at the initial home visit and either in person or by telephone every 3 months thereafter based on current health status (poor, fair, good, very good, excellent) and health status compared to three months ago (much worse, somewhat worse, about the same, somewhat better, much better). ‘Good’ current self-rated health at each time point was defined as reporting good, very good or excellent health. ‘Better’ health at each time point was defined as reporting somewhat or much better health over the past 3 months. Changes compared to baseline values were determined using McNemar’s test.

Results

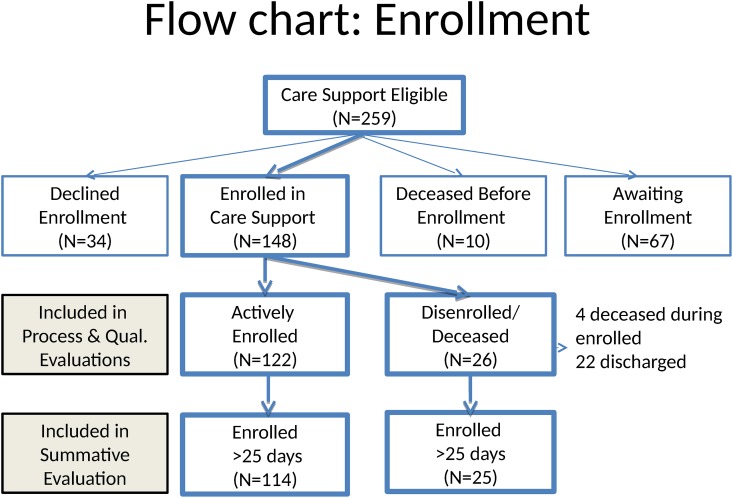

The flow of patients is shown in Fig 1. A total of 259 patients were identified as being eligible for Care Support. Of these, 148 were enrolled from 4/29/2013 to 5/31/2014 while 34 declined enrollment, ten died before enrollment, and 67 were placed on a waitlist. There were a variety of reasons for disenrollment, including: 1) patient request, 2) team assessment that patient goals for the program had been met and 3) inability to engage patient due to lack of interest or to reach patient by phone or in person. The process evaluation included all 148 patients who enrolled in Care Support, of whom 26 disenrolled (22 were discharged, 4 died) during the observation period. The summative evaluation was restricted to the 139 patients with >25 days of follow-up, of whom 25 had disenrolled or died during the observation period.

Fig 1. Flow of Patients.

Process Evaluation

Patients, Process and Fidelity

Demographic characteristics of Care Support patients are shown in Table 1. Patients had a mean age of 65 years at enrollment; 60% were women, 85% had at least a high school degree, and 26% were living alone. Younger patients were more likely than older patients to report fair/poor self-rated health (85% vs. 55%, p<0.001) and had more depressive symptoms (median: 4 vs. 1, p<0.001) but were less likely to be dependent in one or more IADLs (37% vs. 72%, p<0.001) or ADLs (19% vs. 6%, p = 0.02).

Table 1. Characteristics of Care Support Patients.

| Characteristics | Value /Sub-Group | Overall (n = 148) | Age < 65 (n = 67) | Age ≥ 65 (n = 81) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment | Mean ± SD | 65.5 ± 18.5 | 49.1 ± 12.7 | 79.0 ± 9.3 | <0.001 |

| Female sex | Number (%) | 89 (60.1) | 35 (52.2) | 54 (66.7) | 0.074 |

| Education | Number (%) | ||||

| <High School | 22 (15.5) | 7 (10.9) | 15 (19.2) | 0.301 | |

| High School | 32 (22.5) | 17 (26.6) | 15 (19.2) | ||

| >High School | 88 (62.0) | 40 (62.5) | 48 (61.5) | ||

| Living alone | Number (%) | 37 (25.7) | 13 (20.0) | 24 (30.4) | 0.050 |

| Insurance status | Number (%) | ||||

| Medicare A/B | 90 (60.8) | 19 (28.4) | 71 (87.7) | <0.001 | |

| Medicaid | 82 (55.4) | 44 (65.7) | 38 (46.9) | 0.022 | |

| Private | 59 (39.9) | 22 (32.8) | 37 (45.7) | 0.112 | |

| Self-rated health | Number (%) | ||||

| Fair/Poor | 96 (68.6) | 55 (84.6) | 41 (54.7) | <0.001 | |

| Medical diagnoses | Number (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 70 (54.3) | 29 (52.7) | 41 (55.4) | 0.763 | |

| Diabetes | 45 (34.9) | 20 (36.4) | 25 (33.8) | 0.761 | |

| Renal disease | 42 (32.6) | 13 (23.6) | 29 (39.2) | 0.062 | |

| CHF | 35 (27.1) | 8 (14.5) | 27 (36.5) | 0.006 | |

| COPD | 34 (26.4) | 20 (36.4) | 14 (18.9) | 0.026 | |

| Depressive symptoms | Median (range) | 2 (0–12) | 4 (0–12) | 1 (0–11) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption | Number (%) | ||||

| None | 95 (70.4) | 41 (66.1) | 54 (74.0) | .234 | |

| Moderate | 23 (17.0) | 11 (17.7) | 12 (16.4) | ||

| High | 17 (12.6) | 10 (16.1) | 7 (9.6) | ||

| Smoking | Number (%) | ||||

| Current | 26 (19.7) | 17 (28.8) | 9 (12.3) | 0.022 | |

| Former | 44 (33.3) | 21 (35.6) | 23 (31.5) | ||

| Never | 62 (47.0) | 21 (35.6) | 41 (56.2) | ||

| ≥ 1 IADL dependency | Number (%) | 81 (56.3) | 24 (36.9) | 57 (72.2) | <0.001 |

| ≥ 1 ADL dependency | Number (%) | 19 (13.2) | 4 (6.2) | 15 (19.0) | 0.024 |

| Fall, past 6 months | 57 (41.6) | 22 (35.5) | 35 (46.7) | 0.186 |

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; SD, standard deviation. Percentages calculated excluding missing data. Data missing as follows: education (n = 6), living alone (n = 4), self-rated health (n = 8), medical diagnosis (n = 19), PHQ4 (n = 21), alcohol (n = 13), smoking (n = 16), IADL (n = 4), ADL (n = 4), falls (n = 11).

Process measures and fidelity to the original GRACE model are shown in Table 2. In general, Care Support adhered to the process goals of GRACE with high fidelity. An average of six standardized protocols were activated, the most common of which were chronic condition self-management (95%), social service coordination (87%) and advanced care planning (83%). Mental health protocols were activated more often in younger than older patients (70% vs. 48%, p = 0.007). The Care Support team interacted with patients an average of once in person and three times by phone during the first 30 days of enrollment.

Table 2. Process Measures and Fidelity to GRACE Model.

| GRACE Process Target Achieved | Value /Sub-Group | Overall (n = 148) | Age < 65 (n = 67) | Age ≥ 65 (n = 81) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-home assessment ≤ 15 days after enrollment | Number (%) | 146 (98.6) | 66 (98.5) | 80 (98.8) | -- |

| Team conference ≤ 15 days after in-home assessment | Number (%) | 144 (97.3) | 66 (98.5) | 78 (96.3) | 0.196 |

| Team conference included: | Number (%) | ||||

| Geriatrician | 144 (97.3) | 64 (95.5) | 80 (98.8) | 0.117 | |

| Mental health | 134 (90.5) | 60 (89.6) | 74 (91.4) | 0.728 | |

| Pharmacist | 123 (83.1) | 55 (82.1) | 68 (84.0) | 0.783 | |

| Care plan reviewed with PCP ≤ 15 days | Number (%) | 139 (93.9) | 63 (94.0) | 76 (93.8) | 0.463 |

| Care plan reviewed with patient ≤ 1 month | Number (%) | 142 (95.9) | 65 (97.0) | 77 (95.1) | -- |

| Patient contacted ≤ 5 days after ED visit or discharge * | Number (%) | 38 (79.2) | 30 (93.8) | 8 (50.0) | <0.001 |

| Other Process Measures | |||||

| Protocols activated | Mean ± SD | 5.6 ± 1.7 | 5.4 ± 1.7 | 5.7 ± 1.6 | 0.283 |

| Protocol types activated | Number (%) | ||||

| Chronic condition | 141 (95.3) | 64 (95.5) | 77 (95.1) | 0.895 | |

| Social service | 131 (88.5) | 61 (91.0) | 70 (86.4) | 0.380 | |

| Advanced care planning | 124 (83.8) | 62 (92.5) | 62 (76.5) | 0.009 | |

| Mental health | 86 (58.1) | 47 (70.1) | 39 (48.1) | 0.007 | |

| Medication management | 59 (39.9) | 21 (31.3) | 38 (46.9) | 0.054 | |

| Mobility/falls | 58 (39.2) | 14 (20.9) | 44 (54.3) | <0.001 | |

| Caregiver support | 56 (37.8) | 19 (28.4) | 37 (45.7) | 0.031 | |

| Face-to-face contacts, first 30 days | Mean ± SD | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 0.837 |

| Telephone contacts, first 30 days | Mean ± SD | 2.6 ± 2.2 | 2.7 ± 1.8 | 2.6 ± 2.5 | 0.742 |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; PCP, primary care physician. Missing data included in denominator for percentages. Data missing as follows: team conference (n = 2), care plan reviewed (n = 6), patient contacted ≤ 5 days after ED visit (n = 6), face-to-face contacts (n = 6), telephone contact (n = 6).

*Restricted to patients with at least one ED visit or discharge during the first 30 days.

Adaptations, Barriers and Facilitators

Several adaptations were made to accommodate the internal environment (Table 3). Enrollment criteria were relaxed to include patients of all ages who PCPs felt could potentially benefit from the interventions; standardized protocols were adapted based on the needs of this expanded patient population; some assessments were performed in the clinic or by phone rather than at home based on patient preferences. Despite these adaptations, most core elements of the GRACE model were not changed, including the comprehensive NP/SW assessment, development of individualized care plans in consultation with an interdisciplinary team, review and approval by the PCP, and activation of standardized care protocols.

Table 3. Core Components of GRACE and Adaptations for Care Support.

| Original GRACE Model | Adaptations for Care Support |

|---|---|

| Age ≥ 65 | No age restriction |

| Comprehensive in-home assessment by NP/SW team | Some assessments performed in clinic |

| Individualized care plan developed with interdisciplinary team | -- |

| Approval of care plan by primary care physician | -- |

| Activation of standardized care protocols | Protocols simplified and streamlined |

The key barriers to Care Support implementation included: changes in the enrollment criteria as the program evolved, which made it more difficult for PCPs to identify appropriate patients for enrollment and sometimes resulted in frustration with the program and the process; limited initial access to mental health services, which made it difficult to support patients with more severe mental illness; being spread out at multiple sites, which made meeting and communication more difficult; and the size of the patient panel, which sometimes limited the amount of time available to address the needs of each patient.

The key facilitators identified included: the GRACE protocols, which provided structured and adaptable templates and enabled the team to more efficiently manage patients with complex care needs; the home visit, which provided the team with key insights into the real-world issues and day-to-day needs of each patient in their own environment; the comprehensive assessment, which provided a complete picture of all of the patient’s needs and the interdisciplinary team, which enabled incorporation of a wide range of perspectives. In addition, being embedded in the primary care clinics enabled the Care Support team to build greater rapport with PCPs and to meet patients at their clinic visits, thereby increasing the frequency of in-person “touches” and increasing the ability to implement interventions quickly and strengthening relationships with patients.

Finally, several patient profiles were described as seeming to benefit the most from Care Support. 1) In patients with high, resource-intensive needs—particularly those with multiple complex conditions and poor care coordination—the Care Support team was able to hand-pick a team of expert care providers, augment self-management and caregiver support and assist with care coordination in order to provide these complex patients with optimal care. 2) In patients with little community support—particularly those who were living alone, non-trusting of the medical system or resistant to care—the Care Support team was able to build trust using a more personal approach and to help these patients develop their self-management skills once trust had been gained. 3) In patients with mild anxiety who were using the ED to address an array of symptom concerns, the Care Support team was able to develop personal relationships in which patients would call them before going to the ED, so that the Care Support team could provide reassurance when indicated and minimize unnecessary ED visits.

In contrast, patients who seemed to benefit the least from Care Support exhibited different patient profiles. In particular, the NP/SW teams felt that they did not have the training to provide optimal care for patients with more severe or very complex mental health needs, such as those with active substance abuse, alcoholism or personality disorders. It was felt that these patients would be better served by either referral to specialty mental health professionals or integration of mental health professionals into the team. In addition, some patients were not ready to engage with the Care Support team or learn self-management skills.

Summative Evaluation

Health care Utilization

By design, all patients had 182 observation days during the 6-month period before enrollment in Care Support. After enrolling in Care Support, the number of observation days varied widely (median: 180; range: 26–397): patients were enrolled on an ongoing basis from 4/29/2013–5/31/2014; therefore, those enrolled earlier had more time available for follow-up. However, the median number of observation days in the pre- and post-Care Support periods did not differ significantly (p = 0.54).

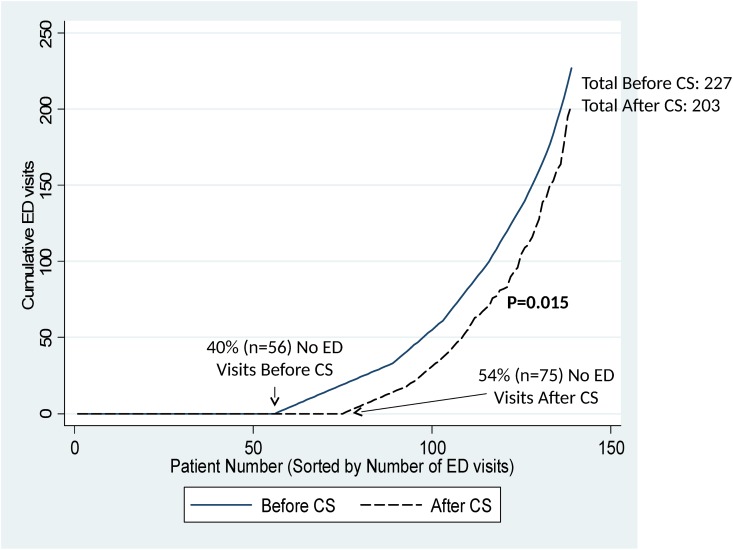

The median number of ED visits/1000 observation days declined significantly from 5.5 (range: 0–54.9) before Care Support to 0 (range: 0–87.0) after Care Support enrollment (p = 0.015). As shown in Fig 2, this difference was primarily attributable to a significant increase in the proportion of patients with zero ED visits before and after enrollment (40% vs. 54%, p = 0.015). The total number of ED visits in these patients was 227 before Care Support and 203 after Care Support.

Fig 2. Cumulative Number of Emergency Department (ED) Visits in Care Support (CS) Patients Before and After Enrollment.

The cumulative number of ED visits is shown as a function of patient number (sorted by number of ED visits) during the 6 months before enrollment in Care Support (solid line) and the 6 months after enrollment (dashed line). The proportion of patients with zero ED visits increased significantly from 40% pre-enrollment to 54% post-enrollment (McNemar’s test, p = 0.015).

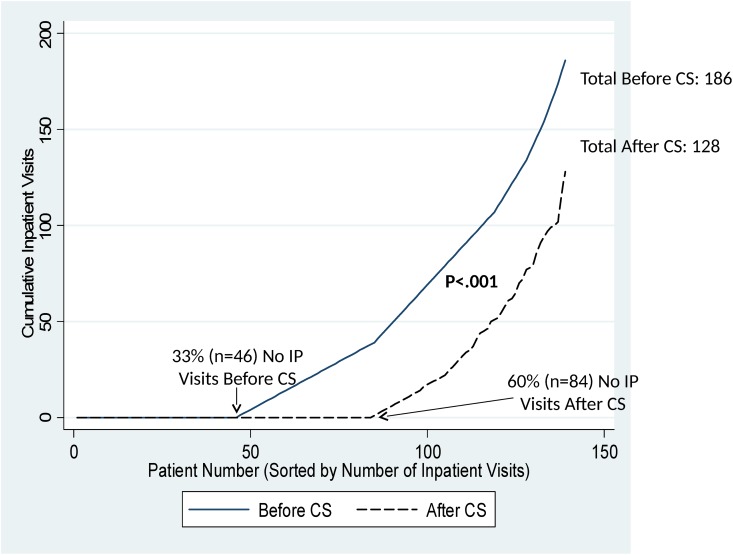

Similarly, the median number of hospitalizations/1000 observation days declined significantly from 5.5 (range: 0–33.0) to 0 (range: 0–43.0) before and after Care Support enrollment (p<0.001). This difference also was primarily attributable to the proportion of patients with zero hospitalizations, which nearly doubled from 33% before Care Support to 60% after Care Support (p<0.001, Fig 3). The total number of hospitalizations in these patients was 186 before Care Support and 128 after Care Support. In those who were hospitalized, median length of stay did not differ before (median: 6 days; range: 1–57) vs. after (median: 5; range: 1–72) Care Support (p = 0.25). There was no evidence of difference based on age.

Fig 3. Cumulative Number of Inpatient Visits (IP) Visits in Care Support (CS) Patients Before and After Enrollment.

The cumulative number of IP visits is shown as a function of patient number (sorted by number of IP visits) during the 6 months before enrollment in Care Support (solid line) and the 6 months after enrollment (dashed line). The proportion of patients with zero IP visits increased significantly from 33% pre-enrollment to 60% post-enrollment (McNemar’s test, p<0.001).

There were relatively few non-UCSF ED visits and hospitalizations reported. Patients reported 20 non-UCSF ED visits during the 6 months before enrollment in Care Support compared to 16 after (p = 0.56). There was a significant decline in non-UCSF ED admissions, with 16 reported prior to enrollment in Care Support and 4 reported after enrollment (p = 0.008).

Patient Self-Rated Health

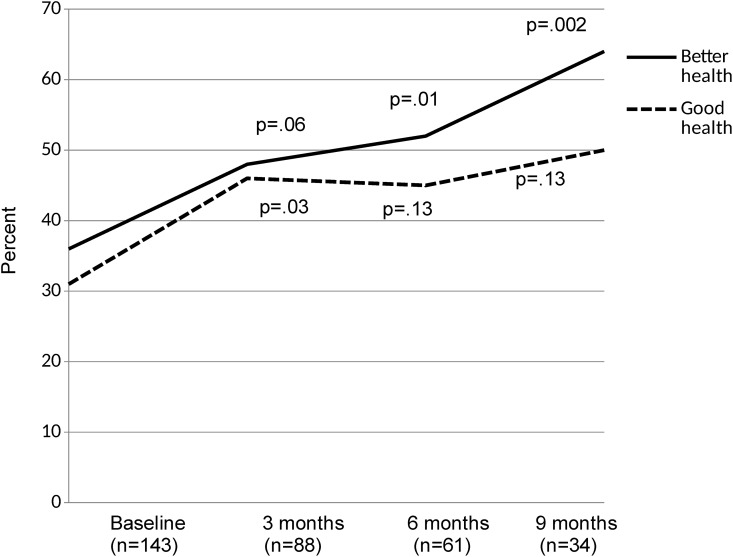

The proportion of patients who rated their health as good, very good or excellent increased over time from 31% at the time of enrollment in Care Support to 50% after 9 months, although this was statistically significant only at 3 months (Fig 4). Similarly, the proportion of patients who reported that their health was somewhat or much better than three months ago increased from 36% at enrollment to 64% at 9 months (p = 0.002) (Fig 4).

Fig 4. Changes in Self-Rated Health in Care Support Patients Over Time.

The percentage of patients who self-reported good health (defined as good, very good or excellent versus fair or poor) is shown in red, while the percentage of patients who self-reported that their health was better than 3 months ago (defined as somewhat or much better versus about the same, somewhat worse or much worse) is shown in blue. P-values are based on McNemar’s test for paired proportions compared to baseline values.

Discussion

In this study, we used the CFIR conceptual model to evaluate the process and impact of implementation of the evidence-based GRACE model at an urban, academic medical center. Importantly, one of the key adaptations to meet the needs of our medical center was to expand the program to include high-utilizing and high-need adult patients of all ages rather than restricting enrollment to older patients, which resulted in changing the name to Care Support, revising protocols and addressing an array of patient concerns beyond traditional geriatric syndromes. None-the-less, most core components of the program remained consistent with the original model, including comprehensive in-home assessments by an NP/SW team; creation of a comprehensive care plan in consultation with an interdisciplinary care team; and activation of standardized care protocols to address common issues. Care Support team members felt that the patients who appeared to benefit the most were those with complex medical needs, little community support, and mild levels of anxiety, which are known drivers of high health care utilization.[3, 12] Those who benefitted the least were those with more severe mental health issues and lack of interest in engaging with the health care system.

In patients who enrolled in Care Support, health care utilization declined significantly for both ED visits and hospitalizations when comparing utilization 6 months before versus 6 months after enrollment. In addition, patients reported significantly better self-rated health over time after enrolling in Care Support. The impact of Care Support implementation was similar to the original efficacy study, which found decreased acute care utilization and improved self-rated health in those who participated in the program compared to a usual care control group.[6]

There is growing evidence that home-based and team-based care models can improve quality of care while reducing utilization and costs. Although one recent systematic review of preventive home visits from health or social care professionals concluded that they had no effect on mortality, institutionalization or hospitalization and only small effects on function and quality of life,[13] several other systematic reviews and meta-analyses have identified specific aspects of home-based care that are associated with better outcomes. Specifically, beneficial effects of home visits are greater in interventions that include more visits,[14] younger patients[14, 15] and multidimensional assessment.[14, 15] In addition, home-based primary care is most effective when it involves interprofessional care teams that meet regularly and provide after-hours support,[16] all of which are aspects of Care Support.

Similarly, a comparative effectiveness review found that outpatient case management for adults with complex care needs is associated with small improvements in quality of life, quality of care and health care utilization.[17] Characteristics of successful interventions included greater contact time, longer duration, face-to-face visits, and integration with patients’ usual care providers.[17]

A comprehensive synthesis of care management in patients with complex health care needs[18] found that there is “convincing evidence” that care management in primary care improves quality of care, with significant improvements observed in 7 of 9 studies.[6, 19–26] However, only 3 of these studies found significant reductions in utilization and costs, one of which was GRACE.[6, 20, 22] All three of these studies specifically targeted patients with multiple chronic conditions and an increased risk of incurring major health care costs. In addition, they all emphasized training of the care management team, reasonable patient panel sizes, building relationships with PCPs and frequent contacts with patients.[18]

Identifying key elements of care for patients who have complex care needs is becoming particularly relevant as payers and healthcare systems focus on value-based care.27 Whereas much of the emphasis of integrated care delivery networks has been on identifying those with the highest need using various types of “analytics,”28 an equal amount of attention will need to be directed toward which care elements offer the most benefit to those with a complex array of health and social concerns. The adaptations of GRACE described in this study may be relevant in a number of care settings and, with standardization, could be disseminated widely.

Strengths of our study include the comprehensive evaluation using the CFIR model. Weaknesses include lack of randomization to intervention and control groups, which we attempted to address by using patients as their own controls and comparing utilization during the 6 months before and after enrollment in Care Support. We did not use the 67 patients on the waitlist as controls because implementation of Care Support was associated with changes in the targeted clinics (e.g., staffing, education) that could potentially have had indirect benefits in those not formally enrolled. In addition, our analyses of utilization outside our medical center were based on self-report. Our interdisciplinary team included a mental health professional (PhD psychologist), which may not be available in all healthcare settings; however, this team member primarily served as a consultant to the team, and there is growing awareness of the importance of incorporating mental health to maximize patient well-being. Finally, although utilization decreased, we were unable to perform a formal cost-benefit analysis. The key costs were related to staffing, which included a full-time social worker and full-time nurse practitioner. During implementation, this was increased from one to two teams. The savings due to decreased utilization would be extremely difficult to estimate because different patients had different types of insurance with different payment policies.

In summary, our study suggests that it is feasible to implement the GRACE/Care Support model at an academic medical center by making adaptations based on local needs, and that patients who participated in Care Support experienced significant reductions in acute care utilization and improvements in self-rated health.

Supporting Information

To minimize the risk of loss of privacy for older patients, age has been truncated to a maximum value of 89 years.

(XLS)

Acknowledgments

Contributors: We would like to thank the following individuals for the contributions to the development and evaluation of Care Support at UCSF: Brie Williams, MD, MS, Associate Professor of Medicine in the Division of Geriatrics at UCSF, Medical Director of the San Francisco VA Geriatrics Clinic and Associate Director of Discovery for Tideswell™ at UCSF; Anna Chang, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine in the Division of Geriatrics at UCSF and Associate Director for Education and Leadership for Tideswell™ at UCSF; G. Michael Harper, MD, Professor of Medicine in the Division of Geriatrics at UCSF and Associate Director for Clinical Care Models for Tideswell™ at UCSF; Tim Moriarty, MBA, MA, EPIC Clarify Certified Consultant, UCSF Medical Center; and the Indiana University GRACE Training and Resource Center.

Prior presentations: California Association of Public Hospitals and Health Systems/Safety Net Institute Annual Conference, December 2014, San Diego, CA; and American Geriatrics Society, May 2015, National Harbor, MD.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files. To minimize the risk of loss of privacy for older patients, age has been truncated to a maximum value of 89 years. We do not have IRB approval to provide specific ages for patients age 90 years or older.

Funding Statement

Evaluation of Care Support was supported by a grant to TideswellTM at UCSF from the S.D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation. The SCAN Foundation provided support for the training and implementation assistance provided by the Indiana University Geriatrics GRACE Training and Resource Center to the UCSF Care Support program. The SCAN Foundation – advancing a coordinated and easily navigated system of high-quality services for older adults that preserve dignity and independence. For more information, please visit www.TheSCANFoundation.org. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Grant RW, Ashburner JM, Hong CS, Chang Y, Barry MJ, Atlas SJ. Defining patient complexity from the primary care physician's perspective: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(12):797–804. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-12-201112200-00001 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss KB. Managing complexity in chronic care: an overview of the VA state-of-the-art (SOTA) conference. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22 Suppl 3:374–8. 10.1007/s11606-007-0379-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conwell LI, Cohen JW. Characteristics of persons with high medical expenditures in the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population, 2002. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, March 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feder JL. Predictive modeling and team care for high-need patients at HealthCare Partners. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(3):416–8. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0080 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Buttar AB, Clark DO, Frank KI. Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders (GRACE): a new model of primary care for low-income seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(7):1136–41. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00791.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO, Tu W, Buttar AB, Stump TE, et al. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(22):2623–33. 10.1001/jama.298.22.2623 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Tu W, Stump TE, Arling GW. Cost analysis of the Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders care management intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1420–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613–21. 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of Illness in the Aged. The Index of Adl: A Standardized Measure of Biological and Psychosocial Function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–9. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–86. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fogarty CT, Sharma S, Chetty VK, Culpepper L. Mental health conditions are associated with increased health care utilization among urban family medicine patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(5):398–407. 10.3122/jabfm.2008.05.070082 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayo-Wilson E, Grant S, Burton J, Parsons A, Underhill K, Montgomery P. Preventive home visits for mortality, morbidity, and institutionalization in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e89257 10.1371/journal.pone.0089257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stuck AE, Egger M, Hammer A, Minder CE, Beck JC. Home visits to prevent nursing home admission and functional decline in elderly people: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. JAMA. 2002;287(8):1022–8. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huss A, Stuck AE, Rubenstein LZ, Egger M, Clough-Gorr KM. Multidimensional preventive home visit programs for community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(3):298–307. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stall N, Nowaczynski M, Sinha SK. Systematic review of outcomes from home-based primary care programs for homebound older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(12):2243–51. 10.1111/jgs.13088 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hickam DH, Weiss JW, Guise J-M, Buckley D, Motu'apuaka M, Graham E, et al. Outpatient case management for adults with medical illness and complex care needs Comparative effectiveness review no. 99. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, January 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bodenheimer T, Berry-Millett R. Care management of patients with complex health care needs. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, December 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boult C, Boult LB, Morishita L, Dowd B, Kane RL, Urdangarin CF. A randomized clinical trial of outpatient geriatric evaluation and management. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(4):351–9. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boult C, Reider L, Frey K, Leff B, Boyd CM, Wolff JL, et al. Early effects of "Guided Care" on the quality of health care for multimorbid older persons: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(3):321–7. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen HJ, Feussner JR, Weinberger M, Carnes M, Hamdy RC, Hsieh F, et al. A controlled trial of inpatient and outpatient geriatric evaluation and management. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(12):905–12. 10.1056/NEJMsa010285 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dorr DA, Wilcox AB, Brunker CP, Burdon RE, Donnelly SM. The effect of technology-supported, multidisease care management on the mortality and hospitalization of seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(12):2195–202. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02005.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gagnon AJ, Schein C, McVey L, Bergman H. Randomized controlled trial of nurse case management of frail older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(9):1118–24. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schraeder C, Shelton P, Sager M. The effects of a collaborative model of primary care on the mortality and hospital use of community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(2):M106–12. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sledge WH, Brown KE, Levine JM, Fiellin DA, Chawarski M, White WD, et al. A randomized trial of primary intensive care to reduce hospital admissions in patients with high utilization of inpatient services. Dis Manag. 2006;9(6):328–38. 10.1089/dis.2006.9.328 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stock R, Mahoney ER, Reece D, Cesario L. Developing a senior healthcare practice using the chronic care model: effect on physical function and health-related quality of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(7):1342–8. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01763.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

To minimize the risk of loss of privacy for older patients, age has been truncated to a maximum value of 89 years.

(XLS)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files. To minimize the risk of loss of privacy for older patients, age has been truncated to a maximum value of 89 years. We do not have IRB approval to provide specific ages for patients age 90 years or older.