Abstract

Recent evidence indicated that interspecific hybridization was the major mode of evolution in Pyrus. The genetic relationships and origins of the Asian pear are still unclear because of frequent hybrid events, fast radial evolution, and lack of informative data. Here, we developed fluorescent sequence-specific amplification polymorphism (SSAP) markers with lots of informative sites and high polymorphism to analyze the population structure among 93 pear accessions, including nearly all species native to Asia. Results of a population structure analysis indicated that nearly all Asian pear species experienced hybridization, and originated from five primitive genepools. Four genepools corresponded to four primary Asian species: P. betulaefolia, P. pashia, P. pyrifolia, and P. ussuriensis. However, cultivars of P. ussuriensis were not monophyletic and introgression occurred from P. pyrifolia. The specific genepool detected in putative hybrids between occidental and oriental pears might be from occidental pears. The remaining species, including P. calleryana, P. xerophila, P. sinkiangensis, P. phaeocarpa, P. hondoensis, and P. hopeiensis in Asia, were inferred to be of hybrid origins and their possible genepools were identified. This study will be of great help for understanding the origin and evolution of Asian pears.

Introduction

The genus Pyrus, with the common name pear, is believed to have originated in the mountainous areas of western and southwestern China [1]. Based on their geographic distribution, Pyrus is divided into two groups: occidental and oriental pears [1,2]. The oriental pears (also referred to as Asian pears) include 12–15 species, the majority being native to China [3]. Wild pea pears: P. betulaefolia Bunge and P. calleryana Decne. (including P. dimorphophylla Makino, P. fauriei C.K.Schneid., and P. koehnei C.K.Schneid., which were once classified as varieties of P. calleryana), bearing small fruit with a diameter of ~1 cm and two carpels, are believed to be ancestral species [4]. P. pashia D. Don is naturally distributed in Southwest China, and shows morphological diversity and carpel numbers from two to five [5,6]. The majority of remaining species, such as P. phaeocarpa Rehder, P. hopeiensis T.T.Yu, P. xerophila T.T.Yu and P. serrulata Rehder, have been reported to be inter-specific hybrids [7,8], but their origins were uncertain. Most cultivated pears native to Asia are assigned to three species: P. ussuriensis Maxim. (Ussurian pear), P. sinkiangensis T.T.Yu (Xinjiang pear) and P. pyrifolia Nakai [9]. Based on the geographic distribution, the cultivated P. pyrifolia was further divided into three cultivar groups: Chinese white pear group (sometimes mistakenly assigned as P. bretschneideri Rehd.), Chinese sand pear group and Japanese pear group [3]. The origin of some cultivated pear groups is still controversial. Understanding the domestication process of the cultivated pear and the evolutionary process of the pear species will be helpful in exploiting elite genetic resources in pears and aid in modern breeding.

Frequent interspecific hybridization events, which cause reticulate evolution, hamper our ability to understand the evolutionary history of the plants. Owing to the lack of a reproductive barrier among Pyrus species, interspecific hybridization was determined to be the major mode of Pyrus evolution [6,7,10,11]. DNA-based markers, such as restriction fragment length polymorphisms [12], random amplified polymorphic DNAs (RAPDs) [13], simple sequence repeats (SSRs) [14,15], and amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLPs) [16], have been used to analyze the genetic relationships in Pyrus, and some possible hybridization events that occurred in Asian pears have been identified. Recently, DNA sequences of chloroplast regions and nuclear genes were used in phylogenetic analyses of Pyrus [6,11,17,18]. Because in these studies, the use of cpDNA fragments and nuclear genes provides limited information sites for analysis, the details of origins of cultivated Asian pears and natural hybrid species have not been resolved.

Retrotransposons are a widespread class of transposable elements that exist in all plant species investigated to date [19–21]. They undergo replicative transposition, by way of an RNA intermediate, and thus their copy numbers increase, occupying large fractions of the genome, especially in higher plants [22–24]. Recently, retrotransposon-based markers, such as retrotransposon-based insertion polymorphisms (RBIPs) [25] and sequence-specific amplification polymorphisms (SSAPs) [26] were developed to study genetic diversity and cultivar identification. Long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons are ubiquitously distributed throughout the Pyrus genome, and 42.4% of the genome has been reported to be LTR retrotransposons [27], implying that retrotransposons may play important roles in Pyrus evolution.

In previous studies, the high heterogeneity and insertion polymorphisms of retrotransposons within Pyrus species were shown by RBIP markers [28,29], indicating that retrotransposons replicated many times in the pear genome. However, RBIP markers only provided a few information sites. Although the use of a larger number of RBIP markers could overcome this short-coming, it would be costly. SSAP markers based on retrotransposons are similar to AFLPs [26]. They both reflect restriction size variation in the whole genome, but SSAP markers also identify polymorphisms produced by retrotransposon insertions [30]. Therefore, SSAP markers have the advantages of high heterogeneity and adequate information sites, which should make them more effective in revealing the genetic relationships within species. In the last years, SSAP markers have been ignored, with only a few studies on SSAPs reported [31,32], and efforts to develop plant SSAP markers were restricted by the lack of known LTR sequences. Recently, the whole genome of the Chinese white pear cultivar ‘Dangshansuli’ was released [27], leading to a faster and more economical approach to predicting retrotransposons and developing SSAP markers in Pyrus.

In this study, we developed SSAP markers based on retrotransposons across the whole pear genome to analyze Pyrus accessions, including cultivars/landraces and wild species from China, Japan, Korea, and Pakistan. The aim of this study was to evaluate the population structures and genetic relationships of pear species and cultivars from Asia, and to reveal the origins of Asian pears.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and DNA extraction

We analyzed 93 Pyrus accessions from four Asian countries. Accessions native to Asia were collected from the China Pear Germplasm Repository, Xingcheng, Liaoning Province, China; Gansu Pomology Institute, Gansu Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Lanzhou, Gansu Province, China; Wuhan Sand pear Germplasm Repository, Wuhan, Hubei Province, China; Tottori University, Tottori, Japan and University of Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan (Table 1). Three accessions of occidental pears were collected from the National Clonal Germplasm Repository, Corvallis, OR, USA.

Table 1. Accessions of investigated species and cultivars of Asian pears and outgroup.

| Code | Taxa | Accession | Origin | Source orLatitude (°N)/ Longitude (°E) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oriental pear | ||||

| Chinese white pear group (CWPG) | ||||

| 1 | P. pyrifolia | Piaobali | Guizhou, China | CPGR |

| 2 | P. pyrifolia | Dadongguo | Gansu, China | GPI |

| 3 | P. pyrifolia | Suli | Anhui, China | CPGR |

| 4 | P. pyrifolia | Fenhongxiao | Hebei, China | CPGR |

| 5 | P. pyrifolia | Fengxianjitui | Shanxi, China | CPGR |

| 6 | P. pyrifolia | Huangjitui | Jiangsu, China | CPGR |

| 7 | P. pyrifolia | Jingchuan | Gansu, China | CPGR |

| 8 | P. pyrifolia | Xiangchun | Shanxi, China | CPGR |

| 9 | P. pyrifolia | Xuehua | Hebei, China | CPGR |

| 10 | P. pyrifolia | Yali | Hebei, China | TU |

| 11 | P. pyrifolia | Yinbai | Hebei, China | CPGR |

| 12 | P. pyrifolia | Xiaojin | Shaanxi, China | CPGR |

| 13 | P. pyrifolia | Dongguo | Gansu, China | GPI |

| 14 | P. pyrifolia | Daaoao | Shangdong, China | CPGR |

| 15 | P. pyrifolia | Eli | Liaoning, China | CPGR |

| 16 | P. pyrifolia | Zhimasu | Hubei, China | CPGR |

| 17 | P. pyrifolia | Qixiaxiaoxiangshui | Shandong, China | CPGR |

| Chinese sand pear group | ||||

| 18 | P. pyrifolia | Baozhuli | Yunnan, China | WSGR |

| 19 | P. pyrifolia | Hongshaobang | Sichuan, China | WSGR |

| 20 | P. pyrifolia | Mandingxueli | Fujian, China | WSGR |

| 21 | P. pyrifolia | Yunlu | Zhejiang, China | WSGR |

| 22 | P. pyrifolia | Baihuli | Fujian, China | WSGR |

| 23 | P. pyrifolia | P. pyrifolia 1 | Yunnan, China | Yunnan, China |

| 24 | P. pyrifolia | Henshanli | Taiwan, China | WSGR |

| 25 | P. pyrifolia | Shexiangli | Hunan, China | WSGR |

| 26 | P. pyrifolia | Mashanshali | Guangxi, China | WSGR |

| Japanese pear group | ||||

| 27 | P. pyrifolia | Tosanashi | Japan | TU |

| 28 | P. pyrifolia | Kansaiyichi | Japan | TU |

| 29 | P. pyrifolia | Nekogoroshi | Japan | TU |

| 30 | P. pyrifolia | Hatsushimo | Japan | TU |

| 31 | P. pyrifolia | Tsukatanashi | Japan | TU |

| Accessions of P. pyrifolia from Korea | ||||

| 32 | P. pyrifolia | Chousennashi | North Korea | TU |

| 33 | P. pyrifolia | Hoeryongbae | North Korea | TU |

| 34 | P. pyrifolia | Hanheungli-Kou | North Korea | TU |

| 35 | P. pyrifolia | Hanheungli-Otsu | North Korea | TU |

| Accessions of P. ussuriensis | ||||

| 36 | P. ussuriensis | Hongbalixiang | Liaoning, China | CPGR |

| 37 | P. ussuriensis | Balixiang | Liaoning, China | CPGR |

| 38 | P. ussuriensis | Mangyuanxiang | Liaoning, China | CPGR |

| 39 | P. ussuriensis | Yaguangli | Hebei, China | CPGR |

| 40 | P. ussuriensis | Hongnanguoli | Liaoning, China | CPGR |

| 41 | P. ussuriensis | Nanguoli | Liaoning, China | CPGR |

| 42 | P. ussuriensis | Saozhoumiaozi | Hebei, China | CPGR |

| 43 | P. ussuriensis | Jianbali | Liaoning, China | CPGR |

| 44 | P. ussuriensis | Reqiuzi | Liaoning, China | CPGR |

| 45 | P. ussuriensis | Xiehuatian | Jilin, China | CPGR |

| 46 | P. ussuriensis | Huagai | Liaoning, China | CPGR |

| 47 | P. ussuriensis | Tianqiuzi | Liaoning, China | CPGR |

| 48 | P. ussuriensis | Ruanerli | Gansu, China | CPGR |

| Accessions of P. sinkiangensis | ||||

| 49 | P. sinkiangensis | Korlaxiangli | Xinjiang, China | CPGR |

| 50 | P. sinkiangensis | Kucheamute | Xinjiang, China | CPGR |

| 51 | P. sinkiangensis | Kunqieke | Xinjiang, China | CPGR |

| 52 | P. sinkiangensis | Zaoshujuju | Xinjiang, China | CPGR |

| 53 | P. sinkiangensis | Hesejuju | Xinjiang, China | CPGR |

| 54 | P. sinkiangensis | Ruantaijuju | Xinjiang, China | CPGR |

| Accessions originated from Pakistan | ||||

| 55 | unknown | Frashishi | Rawalakot, Pakistan | AJK |

| 56 | unknown | Nakh | Rawalakot Pakistan | AJK |

| 57 | unknown | Btangi | Rawalakot, Pakistan | AJK |

| 58 | unknown | Nashpati | Rawalakot, Pakistan | AJK |

| 59 | unknown | Bagugosha | Hajira, Pakistan | AJK |

| Wild pear species native to East Asia | ||||

| 60 | P. phaeocarpa | P. phaeocarpa | Gansu, China | GPI |

| 61 | P. hondoensis | P. hondoensis | Middle Japan | TU |

| 62 | P. hopeiensis | P. hopeiensis | Hebei, China | CPGR |

| 63 | P. pashia | P. pashia 1 | Yunnan, China | 25.12, 101.38 |

| 64 | P. pashia | P. pashia 2 | Yunnan, China | 25.37, 100.85 |

| 65 | P. pashia | P. pashia 3 | Yunnan, China | 24.97, 102.17 |

| 66 | P. pashia | P. pashia 4 | Yunnan, China | 24.97, 102.30 |

| 67 | P. pashia | P. pashia 5 | Yunnan, China | 24.83, 103.45 |

| 68 | P. pashia | P. pashia 6 | Yunnan, China | 26.86, 100.16 |

| 69 | P. pashia | P. pashia 7 | Yunnan, China | 22.45, 100.00 |

| 70 | P. pashia | P. pashia 8 | Yunnan, China | 28.05, 99.51 |

| 71 | P. betulaefolia | P. betulaefolia 1 | Henan, China | 33.31, 113.47 |

| 72 | P. betulaefolia | P. betulaefolia 2 | Shaanxi, China | 36.49, 109.61 |

| 73 | P. betulaefolia | P. betulaefolia 3 | Shaanxi, China | 35.10, 107.99 |

| 74 | P. betulaefolia | P. betulaefolia 4 | Hebei, China | 36.51, 113.57 |

| 75 | P. betulaefolia | P. betulaefolia 5 | Shandong, China | 35.56, 117.46 |

| 76 | P. betulaefolia | P. betulaefolia 6 | Shandong, China | 36.22, 120.45 |

| 77 | P. betulaefolia | P. betulaefolia 7 | Hebei, China | 36.51, 113.57 |

| 78 | P. betulaefolia | P. betulaefolia 8 | Gansu, China | 35.45, 107.95 |

| 79 | P. calleryana | P. calleryana 1 | Zhejiang, China | 28.78, 119.87 |

| 80 | P. calleryana | P. calleryana 2 | Zhejiang, China | 28.78, 119.87 |

| 81 | P. calleryana | P. calleryana 3 | Zhejiang, China | 28.78, 119.87 |

| 82 | P. calleryana | P. calleryana 4 | Zhejiang, China | 29.87, 119.67 |

| 83 | P. calleryana | P. calleryana 5 | Zhejiang, China | 29.87, 119.67 |

| 84 | P. calleryana | P. calleryana 6 | Zhejiang, China | 29.87, 119.67 |

| 85 | P. calleryana | P. calleryana 7 | Zhejiang, China | 29.53, 120.97 |

| 86 | P. xerophila | P. xerophila 1 | Gansu, China | GPI |

| 87 | P. xerophila | P. xerophila 2 | Gansu, China | GPI |

| 88 | P. xerophila | P. xerophila 3 | Gansu, China | GPI |

| 89 | P. xerophila | P. xerophila 4 | Gansu, China | GPI |

| 90 | P. xerophila | P. xerophila 5 | Gansu, China | GPI |

| Occidental pear species | ||||

| 91 | P. gharbiana | P. gharbiana 789 | Morocco | NCGR, PI541663 |

| 92 | P. cordata | P. cordata 750 | France | NCGR, PI541580 |

| 93 | P. salicifolia | P. salicifolia 2720 | Russia | NCGR, CPYR2720 |

CPGR: China Pear Germplasm Repository, Xingcheng, Liaoning Province, China; GPI: Gansu Pomology Institute, Gansu Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Lanzhou, Gansu Province, China; NCGR: National Clonal Germplasm Repository, USA; TU: Tottori University, Japan; WSGR: Wuhan Sand Pear Germplasm Repository, Wuhan, Hubei Province, China; and AJK: University of Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan.

Total genomic DNA was extracted from the leaf tissues of plants following the modified CTAB protocol described by Doyle and Doyle [33]. The DNA concentrations were diluted to 10–30 ng μL-1 after the quality and quantity were determined on 1% (w v-1) agarose gels using standard DNA markers (Takara, Dalian, China).

Development of SSAP markers

In a previous study, 10 subfamilies (KF806690-KF806699) of retrotransposons were isolated in Pyrus [29]. The conserved LTRs of these retrotransposons were used to design the primers.

SSAP analysis

The SSAP analysis was performed using the protocol of Syed and Flavell [34]. Genomic DNA (500 ng) was digested with two restriction enzymes (EcoRI and MseI; New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) then ligated to EcoRI/MseI adapters with T4 DNA ligase (Takara, Dalian, China). After ligation, pre-amplification was performed with EcoRI and MseI primers containing non-selective nucleotides. The pre-amplification products were diluted (1: 10) with TE buffer.

The selective amplifications were carried out with a combination of one LTR primer and one adapter-specific primer. An economic method for fluorescent labeling of PCR fragments was used during selective amplification [35]. We found 12 primer combinations that were polymorphic in our preliminary data analysis, and these were employed for the main data set analysis (Table 2). A tail (M13 universal sequence, TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGT) was added to the 5′ end of each of the MseI adapter-specific primers containing selective nucleotides (Table 2). The tail primers were labeled with the following four dyes: FAM (blue), HEX (green), NED (yellow), and PET (red). The FAM-tail and HEX-tail were synthesized by Invitrogen Trading Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), and the NED-tail and PET-tail by Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA). PCR amplifications were performed in a final volume of 20 μL (2 μL 10× PCR buffer, 200 μM dNTPs, 8 pmol tail primer, 2 pmol adapter-specific primer, 10 pmol LTR-specific primer, 1 U rTaq Polymerase, and 1 μL pre-amplified DNA) using the following parameters: 94°C for 5 min for initial denaturation, then 12 cycles at 94°C (30 s)/65°C (1 min)/72°C (1 min), in which the annealing temperature decreased 0.7°C per cycle, followed by 24 cycles of 94°C (30 s)/53°C (1 min)/72°C (1 min), and a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C. Amplicons were pooled together with an internal size standard (GeneScan™ 500 LIZ, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) according to the distinct dyes, and then, subsequently separated and sequenced using an ABI 3700XL Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Fragment sizes for each accession using each primer combination were analyzed.

Table 2. List of primer sequences used in this study.

| Primer name | Forward sequence | Reverse sequence |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ppcr3F: AATCTTGTATGTTGGTGGAATC | tail-M-ACT / tail |

| 2 | Ppcr1F: TGGACTTTAGATTGGGTTGTGG | tail-M-ACT / tail |

| 3 | Ppgr1F: CAATGTTGTGGCAGGTATTCA | tail-M-ACC / tail |

| 4 | Ppgr1F: CAATGTTGTGGCAGGTATTCA | tail-M-AGC / tail |

| 5 | Ppcr2F: CCAGCATTTTCAACATTACCA | tail-M-AAG / tail |

| 6 | ppgr4F: CTAGCGAAGGTCACAAACTTGA | tail-M-ACC / tail |

| 7 | Ppcr3F: AATCTTGTATGTTGGTGGAATC | tail-M-AAT / tail |

| 8 | ppgr4F: CTAGCGAAGGTCACAAACTTGA | tail-M-AGG / tail |

| 9 | Ppcr3F: AATCTTGTATGTTGGTGGAATC | tail-M-AAC / tail |

| 10 | Ppcr1F: TGGACTTTAGATTGGGTTGTGG | tail-M-AGG / tail |

| 11 | Ppcr4F: CTTGTTGCTTCCCTCCTTTCT | tail-M-AAT / tail |

| 12 | Ppcr3F: AATCTTGTATGTTGGTGGAATC | tail-M-ACG / tail |

Tail indicates the M13 primer (5′TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGT 3′); M indicates the MseI adaptor (5′GATGAGTCCTGAGTAA 3′)

Data analysis

For each primer combination, fragment sizes in all samples were collected and repetitive bands were removed in Microsoft Excel. Total bands without repetition were obtained. Then, based on the total bands, a Perl script was compiled to transform the presence (1) or absence (0) of each band in an accession to binary data.

The genetic relationship was evaluated by a Bayesian approach using the software STRUCTURE 2.3.4 [36,37]. This revealed the genetic structure by assigning individuals or predefined groups to clusters. Ten runs of STRUCTURE were performed with the number of homogeneous genepools (K) from 1 to 10. Each run consisted of a burn-in period of 200,000 iterations followed by 200,000 Monte Carlo Markov Chain iterations, assuming an admixture model. The results were uploaded to the STRUCTURE HARVESTER web site [38] to estimate the most appropriate K value. Replicate cluster analyses of the same data resulted in several distinct estimated assignment coefficients, even though the same starting conditions were used. Therefore, we employed CLUMPP software [39] to average the 10 independent simulations and illustrated the result graphically using DISTRUCT [40].

A dendrogram was constructed based on Nei’s genetic distances [41] by the Neighbor-joining (NJ) method with 500 bootstrap replicates using TREECON (version 1.3b) [42].

Results

Polymorphisms of SSAP

The 93 pear accessions were analyzed for SSAPs using 12 primer combinations, which produced 2,833 fragments varying in size from 70 bp to 500 bp (S1 Table). A total of 2,799 fragments were polymorphic. The average percentage of polymorphic bands for all primer combinations was 98.80% (Table 3). For each primer combination, the number of bands was from 172 to 301. The polymorphic percentage of loci ranged from 0 to 100% (S1 Fig). The specificity increased with the band length (S1 Fig).

Table 3. The polymorphic characterization of sequence-specific amplification polymorphism primers in Asian pear.

| Primer pairs | Number of bands | Number of polymorphic bands | Percentage of polymorphic bands |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ppcr3/M-ACT | 301 | 295 | 98.01 |

| 2 ppcr1/M-ACT | 172 | 170 | 98.84 |

| 3 ppgr1/M-ACC | 246 | 240 | 97.56 |

| 4 ppgr1/M-AGC | 175 | 173 | 98.86 |

| 5 ppcr2/M-AAG | 242 | 241 | 99.59 |

| 6 ppgr4/M-ACC | 270 | 268 | 99.26 |

| 7 ppcr3/M-AAT | 249 | 245 | 98.39 |

| 8 ppgr4/M-AGG | 207 | 207 | 100.00 |

| 9 ppcr3/M-AAC | 278 | 274 | 98.56 |

| 10 ppcr1/M-AGG | 197 | 195 | 98.98 |

| 11 ppcr4/M-AAT | 289 | 288 | 99.65 |

| 12 ppcr3/M-ACG | 207 | 203 | 98.07 |

| Total | 2833 | 2799 | 98.80 |

Genetic relationship of Pyrus accessions

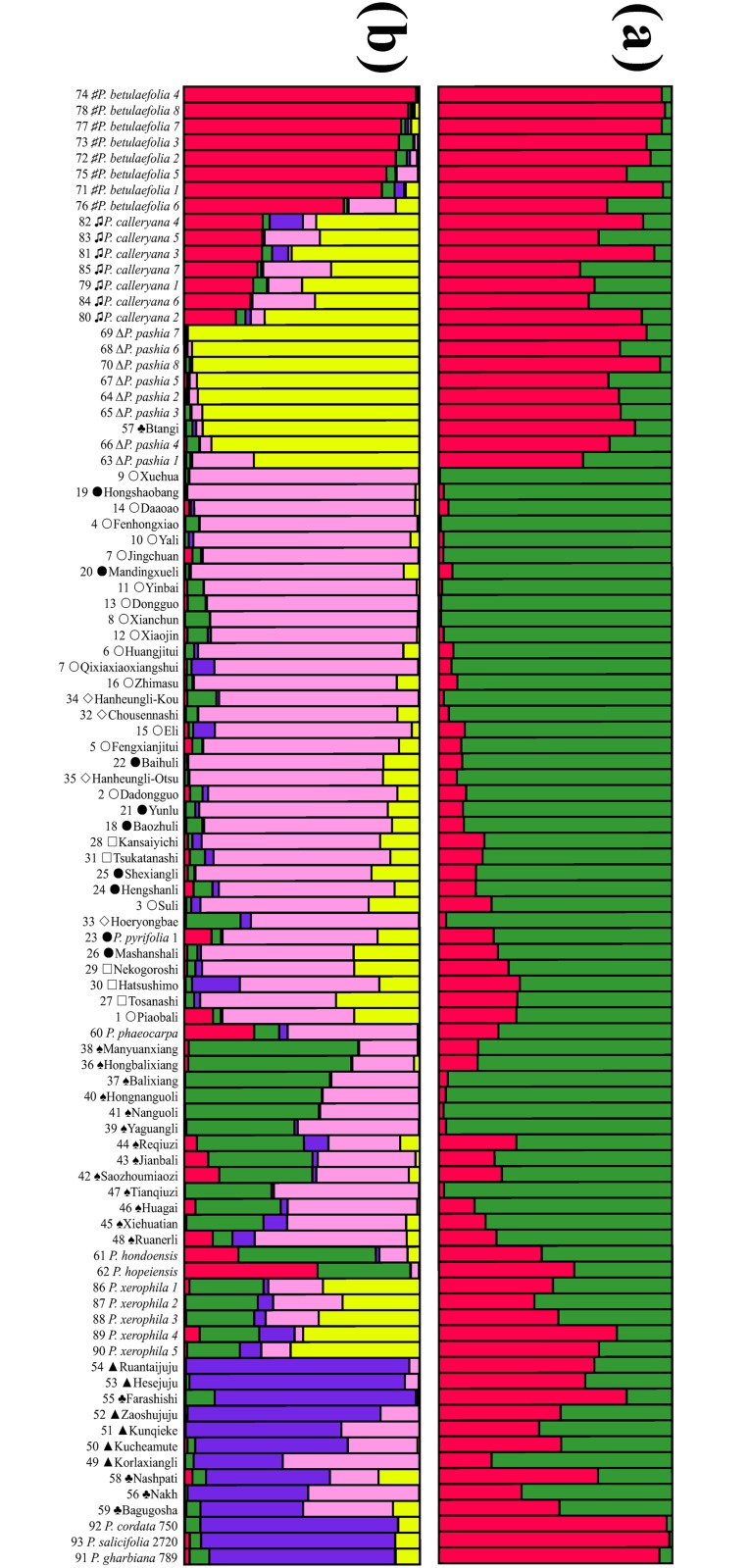

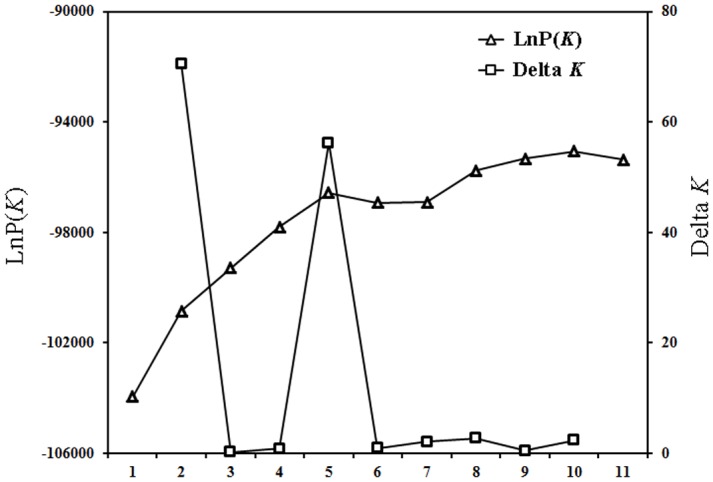

The number of homogeneous genepools (K) among the genotypes of the 93 accessions was modeled by Bayesian methods using the software STRUCTURE. The evaluation of the optimum number of K, which followed the procedure described by Evanno et al. [37], indicated two clear maxima for ΔK at K = 2 and 5 (Fig 1), suggesting that a model with two genepools captured a major split in the data, with substantial additional resolution provided under the model with K = 5. Barplots of the proportional allocations to each genepool for K = 2 and 5 in STRUCTURE are shown in Fig 2.

Fig 1. Modeling of cluster numbers for Asian pears using STRUCTURE software.

LnP (K) and Delta K were calculated in accordance with the method of Evanno et al. [37].

Fig 2. Genetic relationships among the 93 accessions of Asian pears revealed by a Bayesian modeling approach with number of genepools.

(a) K = 2. (b) K = 5.

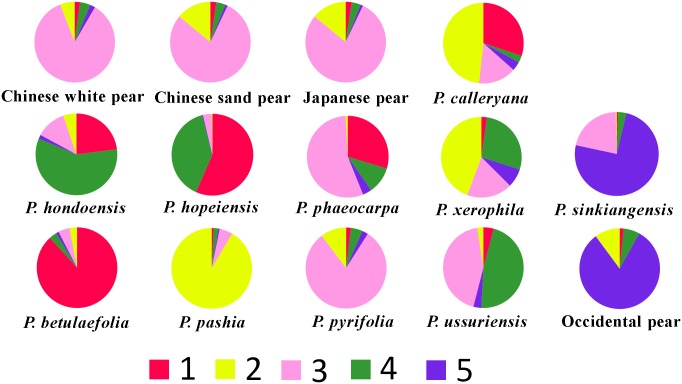

At K = 2, occidental pears and three wild Asian species (P. pashia, P. calleryana, and P. betulaefolia), constituted a genepool (red; Fig 2a). Most of the cultivars from Asia were in another genepool (green; Fig 2a). Under this model, the two genepools substantially overlapped, and the hierarchical levels in these two clusters could hardly be recognized. The model with five genepools was also strongly supported by the STRUCTURE result. Under this model, five genepools for all pear accessions were observed (Figs 2b and 3). The first genepool (red) consisted mainly of P. betulaefolia and P. calleryana accessions and a large portion of P. phaeocarpa, P. hondoensis, and P. hopeiensis clones were also in this genepool. The second genepool (yellow) consisted mostly of P. pashia and P. calleryana but also contained some accessions of P. pyrifolia, P. xerophila, and one accession of the Pakistani pear ‘Btangi’. Accessions of P. calleryana existed in several genepools, mainly in genepools one and two. The third genepool (pink) mainly consisted of P. pyrifolia, P. ussuriensis, and P. sinkiangensis. This genepool contained a large proportion of P. pyrifolia accessions. Two cultivars of ‘Xuehua’ and ‘Hongshaobang’ were present in a very high proportion in the third genepool. Some cultivars, such as ‘Mashanshali’, ‘Nekogoroshi’, ‘Tosanashi’, and ‘Piaobali’ were also present in a relatively large proportion in the second genepool. P. ussuriensis accessions were mainly in the third and fourth genepools (green). The green genepool also contained P. xerophila, P. hondoensis, and P. hopeiensis. The last genepool (blue) consisted mostly of occidental pears, Xinjiang pears (P. sinkiangensis), and majority of pears from Pakistan. In six accessions of P. sinkiangensis, two cultivars (‘Ruantaijuju’ and ‘Hesejuju’) existed in the last genepool. The other four cultivars of Xinjiang pears and accessions from Pakistan contained two major genepools, the third and fifth. For occidental pears, one major genepool (blue) was observed.

Fig 3. The composition of genepools (K = 5) in pear species/groups.

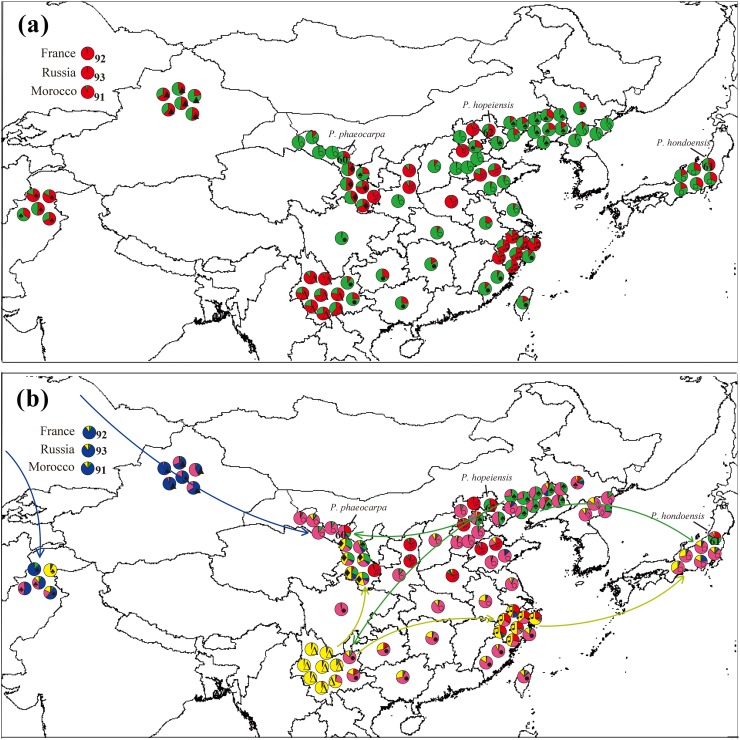

The geographic distribution of genepools for pear accessions

Under the model of K = 2, the two genepools were scattered in different regions (Fig 4a). The direction of genepool spread was hardly recognizable. Under the model of K = 5, the distribution of genepools was related to the species (Fig 4b). The third genepool (pink) was distributed extensively in Asia in accordance with the geographical distribution of P. pyrifolia (including Chinese white pear, Chinese sand pear, and Japanese pear). The last genepool (blue) mainly appeared in Xinjiang Province, Pakistan, and Europe where P. sinkiangensis and occidental pears exist (Fig 4b). The first genepool (red) was mainly distributed in northern China, which was related to the distribution of P. betulaefolia. The second genepool (yellow) appeared in southern China, northwestern China, and Japan, corresponding to the distribution of P. pashia, P. pyrifolia, and P. xerophila. The fourth genepool (green) was mainly in northeastern and northwestern China where P. ussuriensis and P. xerophila are distributed, and also in Japan where P. hondoensis (closer to P. ussuriensis) exists.

Fig 4. The geographic distribution of genepools of Asian pears.

(a) Assignment of samples to two genepools under the cluster numbers K = 2 model. (b) Assignments of samples to five genepools under the K = 5 model. ‘○’: Chinese white pear; ‘●’: Chinese sand pear; ‘□’: Japanese pear; ‘◊’: Korean pear; ‘♠’: Pyrus ussuriensis; ‘▲’: P. sinkiangensis; ‘♣’: Pakistani pear; ‘Δ’: P. pashia; ‘♫’: P. calleryana; ‘♯’: P. betulaefolia; ‘♦’: P. xerophila. The three outgroup accessions are sited in the top left corner.

Genetic relationships among Pyrus species and cultivars revealed by NJ dendrogram

Genetic relationships among the 93 pear accessions were revealed by neighbor-joining clustering approach. The NJ dendrogram (S2 Fig) clearly distinguished occidental pears from oriental pears. In oriental pear group, two wild pears groups were well supported including P. pashia (subgroup II) and P. xerophila (subgroup V). Accessions from P. pyrifolia (Chinese white pear and sand pear) and P. ussuriensis intermingled together, their relationship was poorly resolved. Japanese pears clustered together in Subgroup I with two cultivars from Korea and ‘Yunlu’, a Chinese sand pear from Zhejiang, China. Among the five Pakistan pear accessions, ‘Btangi’ fell into Subgroup II. ‘Nakh’ fell into Subgroup VI with the accessions of P. sinkiangensis, and the remaining three accessions clustered loosely between occidental and oriental pears in the dendrogram (S2 Fig).

Discussion

Characteristics of SSAP markers

In Pyrus, the most abundant retrotransposon families were gypsy and copia, constituting 25.5% and 16.9%, respectively, of the genome [27]. Although the role of retrotransposons in the genome evolution is not yet clear, considering that they comprise a large amount of the genome, they may be an essential part of the plant [30]. The amount of the genome consisting of retrotransposons varies among plants. In Rosaceae, 42.2% of the apple genome is retrotransposons [43], but in peach, this ratio decreased to 18.6% [43,44], which infers that retrotransposons have changed during the evolution of Rosaceae. In Pyrus, retrotransposon insertions indicated a high heterogeneity in different species [29]. Kim et al. [28] and Jiang et al. [29] developed RBIP markers, based on the oriental pear genome, that could be amplified in the oriental species of Pyrus. However, very few amplified in the occidental pear, suggesting that these retrotransposon insertions in the oriental pears occurred after the division of occidental and oriental pears. In this study, 12 SSAP primer combinations revealed high polymorphisms in different Pyrus species (Table 3, S1 Fig), which indicated that retrotransposons had replicated many times during pear development. The percentage of polymorphic bands identified by SSAP markers (98.8%) was higher than that of AFLP markers in Pyrus (89%, [16]), implying that the use of SSAP markers would be more efficient for resolving the genetic relationships among Pyrus species. Fluorescence primers were used in this study to analyze the band sizes, thus avoiding the errors of artificial counting and increased band relevance ratios. In this study, a total of 2,799 polymorphic fragments were obtained from the 12 primer combinations. The informative data from SSAP markers in pears was much more than those from AFLP (77 bands per primer combination, [16]) and SSR markers (28 bands per primer pair, [14]). Because of its low cost and simple protocols, fluorescent SSAP could be more widely used in studies on population structure and genetic relationships in plants.

Primitive genepools and primary species in Asian pears

This is the first time to clarify a clear genetic relationship in Pyrus using retrotransposon-based markers. The STRUCTURE result (Fig 2) and NJ dendrogram (S2 Fig) divided Pyrus into oriental pears and occidental pears, which is in good accordance with the results obtained using AFLP, RAPD, and SSR markers, and DNA sequences [6,15,45].

The structure results provided two models for the genetic relationships of Asian pears. Under the model of K = 2, only two genepools (red and green) were identified (Fig 2a). Generally, the red genepool consisted of wild Asian species and occidental pears. The green genepool included all Asian cultivated pears and putative hybrid species. Although the model of K = 2 was supported by the structure (Fig 2a), it roughly separated wild and cultivated pears, but did not reveal much regarding the relationships among Asian pears. The model of K = 5 provided substantially more resolution (Fig 2b). Under this model, Asian pears, including putative hybrids, originated from five primitive genepools. Except for one genepool corresponded to the occidental pears, the remaining four primitive genepools corresponded to four Asian species: P. pyrifolia, P. ussuriensis, P. betulaefolia, and P. pashia. Therefore, these could be recognized as primary species as defined by Challice and Westwood [46]. The other species in Asia were included in at least two major genepools, which could be considered as hybrid origins.

Gene introgression during cultivated pear development

Whether using the K = 2 or K = 5 structural model, the genotypes of almost all accessions were composed from at least two genepools, which implied that gene introgression commonly occurred during Pyrus evolution and the development of pear cultivars (Fig 2). This introgression was particularly apparent in cultivars of P. pyrifolia and P. ussuriensis. This finding supported the previous hypothesis that interspecific hybridization was the major mode of evolution in Pyrus [6,7,10,11].

There are three major cultivar groups in P. pyrifolia: Chinese sand pear, Chinese white pear and Japanese pear [3,9,16]. Japanese pears have been considered to be from the same germplasm as Chinese sand pears (P. pyrifolia). Recently, Iketani et al. [10] reported genetic differences between Japanese pear, Chinese pear, and Korean pear cultivars, and treated Japanese pears as a new cultivar group, named the Pyrus Japanese pear group. In NJ dendrogram (S2 Fig), five Japanese pear cultivars clustered in subgroup II with two Korean pears and one Chinese pear ‘Yunlu’ from Zhejiang Province. The result of STRUCTURE showed there was almost no difference between the Japanese pear and the Chinese sand pear (Figs 2b and 3). Although most Japanese pears clustered separately from Chinese accessions of the P. pyrifolia in a previous study, a few Japanese pears clustered closely with Chinese sand pears or white pears, especially those that originated from the coastal provinces of China, such as Zhejiang and Fujian [16]. Therefore, the primitive germplasm of the Japanese pear might have been introduced from ancient China, and then, Japanese pear cultivars developed independently, becoming specific.

Among the accessions of Chinese sand pears and white pears, two cultivars, ‘Xuehua’ and ‘Hongshaobang’, had very pure genepools (pink; Fig 2b), and other accessions had complex compositions of genepools, suggesting that most Chinese sand pears and white pears were of hybrid origin. The same situation also occurred in other cultivar groups or species, which explains the poor phylogenetic resolution of Pyrus mentioned in previous research [6,10]. In the past, we considered the current Chinese sand pear cultivars with large fruit as selected and developed artificially from the wild P. pyrifolia of the Changjiang River region. In this study, most accessions of P. pyrifolia were revealed to evolve by a process of introgressive hybridization between P. pyrifolia and P. pashia. The geographic distribution of Pyrus genepools indicated that Chinese sand pear cultivars in southwestern China and Japanese pears were from the same genepool (yellow), while Chinese white pear cultivars in northern China were from a different genepool (green; Fig 4b), which suggested that the gene introgression occurred from P. pashia to P. pyrifolia in southwestern China and Japan, while in northern China the gene introgression happened from P. ussuriensis to P. pyrifolia.

Pyrus ussuriensis is naturally distributed in Northeast China. A few studies revealed differences between cultivars and wild plants of P. ussuriensis, and introgression occurred among wild P. ussuriensis and cultivated P. pyrifolia [47,48]. In this study, the samples of wild P. ussuriensis were not included, but the genetic makeup of cultivars of P. ussuriensis could be clearly revealed. The results of the structure analysis showed that almost all of the P. ussuriensis cultivars were from two major genepools (Fig 2b), and one of them (pink) was from P. pyrifolia. It was noted that the P. ussuriensis cultivars had their own genepool (green) which inferred that the cultivars of P. ussuriensis should be involved in the hybridization between P. pyrifolia and wild P. ussuriensis which might have pure green genepool. The germplasm of P. ussuriensis cultivars were probably manipulated by human activity through hybridization with P. pyrifolia to produce a large fruit.

Origins of hybrid species in Asia

The result of the genetic analysis showed clearly the origins of the putative hybrid species P. calleryana, P. xerophila, P. sinkiangensis, P. phaeocarpa, P. hondoensis, and P. hopeiensis from more than two genepools (Fig 3).

Pyrus calleryana, an important pea pear and excellent rootstock resource, was believed to be an ancestral Pyrus species [1,4] and was treated as a primary species [46]. However, in this study, P. calleryana occurred in two major genepools and a few minor genepools (Fig 3): one major genepool from P. pashia and the other genepool from P. betulaefolia (Fig 4b). P. calleryana and P. betulaefolia had some similar characteristics, including small fruit with (two or three) carpels and lobed leaves during the juvenile stages. However, the leaf shape and margin of P. calleryana were similar to those of P. pashia. According to the distribution of Pyrus [8], P. betulaefolia and P. pashia were both distributed in south part of Northwest China. The hybridization between P. betulaefolia and P. pashia occurred in the areas where these two species overlapped. Then, P. calleryana spread across other regions. A recent report based on multiple genes also indicated P. calleryana was polyphyletic [6].

Pyrus xerophila is mainly distributed in Gansu Province [8] and originated through ancient genetic recombinants that arose by interspecific hybridization involving both oriental and occidental species [6,29]. In our results (Fig 2b), this species was included in three major genepools (yellow, green, and pink/blue), indicating that the species originated through the hybridization of at least P. pashia, P. ussuriensis, and the occidental pears. Occidental pears may have been introduced into Gansu Province from central Asia and west Asia during ancient times through the Silk Road (Fig 4b) [13], which provides the possible hybridization origin of P. xerophila. Pyrus sinkiangensis was shown to contain hybrids between occidental pears and oriental pears [13]. In the results of the STRUCTURE (Fig 2b), two cultivars, ‘Ruantaijuju’ and ‘Hesejuju’, were from a major genepoo1 (blue), while the other four cultivars also contained another genepool (pink), which indicated the hybrid origin of P. sinkiangensis between occidental pears and P. pyrifolia, and the complex genetic composition within the species.

The origins of P. phaeocarpa, P. hopeiensis and P. hondoensis were revealed based on morphological characteristics [4,8] and DNA markers [9]. In this study, only single clones of P. phaeocarpa, P. hopeiensis and P. hondoensis were included. Therefore, remarks on their origins are subjective. However, genetic clues to the origins of these two species can be inferred. P. phaeocarpa shared two major genepools (pink and red; Fig 3) and one minor (green), which indicated that P. phaeocarpa might have originated from the hybridization of P. betulaefolia, P. pyrifolia, and P. ussuriensis. P. hopeiensis occurred in two major genepools (red and green) (Fig 3) which confirmed speculation that the hybrid origins of this species involved P. betulaefolia and wild P. ussuriensis. P. hondoensis contained elements of two major genepools (red and green) and two minor genepools (pink and yellow) (Figs 2 and 3), suggesting its close relationship with P. ussuriensis and the complex genetic composition resulting from hybridization with local species, most probably P. dimorphophylla Makino, which showed a close genetic relationship with P. calleryana [9] and was once classified as a variety of P. calleryana.

Five Pakistan accessions [49] were investigated in this study. ‘Btangi’ was identified as P. pashia, while ‘Nakh’ was grouped together with P. sinkiangensis (Fig 2, S2 Fig). This is the first report on the existence of P. pashia in Pakistan. The remaining three accessions were located between occidental and oriental pears in the NJ dendrogram (S2 Fig). In the STRUCTURE results (Fig 2b), these three species were in two genepools, that of the P. pyrifolia (pink) and that of the occidental pear (blue). We inferred that these three accessions were the result of hybridization events between occidental and oriental pears.

Conclusion

This is the first study on the development of fluorescent SSAP markers based on retrotransposons for the evaluation of the genetic relationships in Asian pears. The result showed that all Asian pear species originated from five primitive genepools. The origin of two major cultivated pear species native to East Asia: P. pyrifolia and P. ussuriensis were involved in gene introgression. P. calleryana, P. xerophila, P. sinkiangensis, P. phaeocarpa, P. hondoensis, and P. hopeiensis were inferred to be hybrid species. Thus, fluorescent SSAP provided enough informative sites to efficiently reveal population structure and the complex hybrid origins in Pyrus. The method applied in this study provides a new insight into the origins of Asian pears and can be used in solving phylogenetic relationships of intrageneric taxa with complex hybrid origins.

Supporting Information

(TIF)

The numbers (1–93) represented code of accessions in sample list. ‘○’: Chinese white pear; ‘●’: Chinese sand pear; ‘□’: Japanese pear; ‘◊’: Korean pear; ‘♠’: Pyrus ussuriensis; ‘▲’: P. sinkiangensis; ‘♣’: Pakistani pear; ‘Δ’: P. pashia; ‘♫’: P. calleryana; ‘♯’: P. betulaefolia; ‘♦’: P. xerophila.

(TIF)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jing Liu, Yu Zong and Chun-Yun Hu for their collections and/or providing leaf samples for DNA extraction.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by a Grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31201592, http://www.nsfc.gov.cn/) awarded to DC, and a Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education (20110101110091, http://www.cutech.edu.cn/cn/index.htm) and a Grant for Innovative Research Team of Zhejiang Province of China (2013TD05, http://www.zjnsf.gov.cn/) awarded to YT. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Rubstov GA. Geographical distribution of the genus Pyrus and trends and factors in its evolution. Am Nat. 1944; 78: 358–366. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailey L. Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture. New York, USA: Macmillan Press; 1917. pp. 2865–2878. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teng Y, Tanabe K. Reconsideration on the origin of cultivated pears native to East Asia. Acta Hortic. 2004; 634: 175–182. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kikuchi A. Horticulture of Fruit Trees. Tokyo, Japan: Yokendo Press; 1948. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu J, Sun P, Zheng X, Potter D, Li K, Hu C, Teng Y. Genetic structure and phylogeography of Pyrus pashia (Rosaceae) in Yunnan Province, China, revealed by chloroplast DNA analyses. Tree Genet Genomes. 2013; 9: 433–441. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng X, Cai D, Potter D, Postman J, Liu J, Teng Y. Phylogeny and evolutionary histories of Pyrus L. revealed by phylogenetic trees and networks based on data from multiple DNA sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2014; 80: 54–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng X, Hu C, Spooner D, Liu J, Cao J, Teng Y. Molecular evolution of Adh and LEAFY and the phylogenetic utility of their introns in Pyrus (Rosaceae). BMC Evol Biol. 2011; 11: 255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu D. Taxonomy of the fruit trees in China. Beijing: China Agriculture Press; 1979. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teng Y, Tanabe K, Tamura F, Itai A. Genetic relationships of Pyrus species and cultivars native to East Asia revealed by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA markers. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2002; 127: 262–270. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iketani H, Katayama H, Uematsu C, Mase N, Sato Y, Yamamoto T. Genetic structure of East Asian cultivated pears (Pyrus spp.) and their reclassification in accordance with the nomenclature of cultivated plants. Plant Syst Evol. 2012; 298: 1689–1700. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng X, Cai D, Yao L, Teng Y. Non-concerted ITS evolution, early origin and phylogenetic utility of ITS pseudogenes in Pyrus. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008; 48: 892–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iketani H, Manabe T, Matsuta N, Akihama T, Hayashi T. Incongruence between RFLPs of chloroplast DNA and morphological classification in east Asian pear (Pyrus spp). Genet Resour Crop Ev. 1998; 45: 533–539. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teng Y, Tanabe K, Tamura F, Itai A. Genetic relationships of pear cultivars in Xinjiang, China, as measured by RAPD markers. J Hortic Sci Biotech. 2001; 76: 771–779. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bao L, Chen K, Zhang D, Cao Y, Yamamoto T, Teng Y. Genetic diversity and similarity of pear (Pyrus L.) cultivars native to East Asia revealed by SSR (simple sequence repeat) markers. Genet Resour Crop Ev. 2007; 54: 959–971. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bassil N, Postman J. Identification of European and Asian pears using EST-SSRs from Pyrus. Genet Resour Crop Ev. 2010; 57: 357–370. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bao L, Chen K, Zhang D, Li X, Teng Y. An assessment of genetic variability and relationships within Asian pears based on AFLP (amplified fragment length polymorphism) markers. Sci Hortic-Amsterdam. 2008; 116: 374–380. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katayama H, Tachibana M, Iketani H, Zhang S, Uematsu C. Phylogenetic utility of structural alterations found in the chloroplast genome of pear: hypervariable regions in a highly conserved genome. Tree Genet Genomes. 2012; 8: 313–326. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lo EYY, Donoghue MJ. Expanded phylogenetic and dating analyses of the apples and their relatives (Pyreae, Rosaceae). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2012; 63: 230–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabot F, Schulman AH. Parasitism and the retrotransposon life cycle in plants: a hitchhiker's guide to the genome. Heredity (Edinb). 2006; 97: 381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.SanMiguel P, Tikhonov A, Jin YK, Motchoulskaia N, Zakharov D, Melake-Berhan A, et al. Nested retrotransposons in the intergenic regions of the maize genome. Science. 1996; 274: 765–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wicker T, Sabot F, Hua-Van A, Bennetzen JL, Capy P, Chalhoub B, et al. A unified classification system for eukaryotic transposable elements. Nat Rev Genet. 2007; 8: 973–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Havecker ER, Gao X, Voytas DF. The diversity of LTR retrotransposons. Genome Biol. 2004; 5: 225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peterson DG, Schulze SR, Sciara EB, Lee SA, Bowers JE, Nagel A, et al. Integration of Cot analysis, DNA cloning, and high-throughput sequencing facilitates genome characterization and gene discovery. Genome Res. 2002; 12: 795–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.SanMiguel P, Gaut BS, Tikhonov A, Nakajima Y, Bennetzen JL. The paleontology of intergene retrotransposons of maize. Nat Genet. 1998; 20: 43–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalendar R, Flavell AJ, Ellis TH, Sjakste T, Moisy C, Schulman AH. Analysis of plant diversity with retrotransposon-based molecular markers. Heredity (Edinb). 2011; 106: 520–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waugh R, McLean K, Flavell AJ, Pearce SR, Kumar A, Thomas BB, et al. Genetic distribution of Bare-1-like retrotransposable elements in the barley genome revealed by sequence-specific amplification polymorphisms (S-SAP). Mol and Gen Genet. 1997; 253: 687–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu J, Wang Z, Shi Z, Zhang S, Ming R, Zhu S, et al. The genome of the pear (Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd.). Genome Res. 2013; 23: 396–408. 10.1101/gr.144311.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim H, Terakami S, Nishitani C, Kurita K, Kanamori H, Katayose Y, et al. Development of cultivar-specific DNA markers based on retrotransposon-based insertional polymorphism in Japanese pear. Breeding Sci. 2012; 62: 53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang S, Zong Y, Yue X, Postman J, Teng Y, Cai D. Prediction of retrotransposons and assessment of genetic variability based on developed retrotransposon-based insertion polymorphism (RBIP) markers in Pyrus L. Mol Genet Genomics. 2015; 290: 225–237. 10.1007/s00438-014-0914-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar A, Bennetzen JL. Plant retrotransposons. Annu Rev Genet. 1999; 33: 479–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Syed NH, Sorensen AP, Antonise R, van de Wiel C, van der Linden CG, van't Westende W, et al. A detailed linkage map of lettuce based on SSAP, AFLP and NBS markers. Theor Appl Genet. 2006; 112: 517–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tam SM, Mhiri C, Vogelaar A, Kerkveld M, Pearce SR, Grandbastien MA. Comparative analyses of genetic diversities within tomato and pepper collections detected by retrotransposon-based SSAP, AFLP and SSR. Theor Appl Genet. 2005; 110: 819–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doyle JJ, Doyle JL. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem Bull. 1987; 19: 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Syed NH, Flavell AJ. Sequence-specific amplification polymorphisms (SSAPs): a multi-locus approach for analyzing transposon insertions. Nat Protoc. 2007; 1: 2746–2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuelke M. An economic method for the fluorescent labeling of PCR fragments. Nat Biotechnol. 2000; 18: 233–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000; 155: 945–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol Ecol. 2005; 14: 2611–2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Earl DA, Vonholdt BM. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv Genet Resour. 2012; 4: 359–361. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jakobsson M, Rosenberg NA. CLUMPP: a cluster matching and permutation program for dealing with label switching and multimodality in analysis of population structure. Bioinformatics. 2007; 23: 1801–1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenberg NA. DISTRUCT: a program for the graphical display of population structure. Mol Ecol Notes. 2004; 4: 137–138. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nei M, Tajima F, Tateno Y. Accuracy of estimated phylogenetic trees from molecular data. II. Gene frequency data. J Mol Evol. 1983; 19: 153–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vandepeer Y, Dewachter R. Treecon for Windows—a Software Package for the Construction And Drawing of Evolutionary Trees for the Microsoft Windows Environment. Comput Applic Biosci. 1994; 10: 569–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Velasco R, Zharkikh A, Affourtit J, Dhingra A, Cestaro A, Kalyanaraman A, et al. The genome of the domesticated apple (Malus x domestica Borkh.). Nat Genet. 2010; 42: 833–839. 10.1038/ng.654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verde I, Abbott AG, Scalabrin S, Jung S, Shu S, Marroni F, et al. The high-quality draft genome of peach (Prunus persica) identifies unique patterns of genetic diversity, domestication and genome evolution. Nat Genet. 2013; 45: 487–U447. 10.1038/ng.2586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Monte-Corvo L, Cabrita L, Oliveira C, Leitao J. Assessment of genetic relationships among Pyrus species and cultivars using AFLP and RAPD markers. Genet Resour Crop Ev. 2000; 47: 257–265. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Challice JS, Westwood MN. Numerical taxonomic studies of the genus Pyrus using both chemical and botanical characters. Bot Jo Linn Soc. 1973; 67: 121–148. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wuyun T, Ma T, Uematsu C, Katayama H. A phylogenetic network of wild Ussurian pears (Pyrus ussuriensis Maxim.) in China revealed by hypervariable regions of chloroplast DNA. Tree Genet Genomes. 2013; 9: 167–177. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iketani H, Yamamoto T, Katayama H, Uematsu C, Mase N, Sato Y. Introgression between native and prehistorically naturalized (archaeophytic) wild pear (Pyrus spp.) populations in Northern Tohoku, Northeast Japan. Conserv Genet. 2010; 11: 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahmed M, Anjum MA, Khan MQ, Ahmed MJ, Pearce S. Evaluation of genetic diversity in Pyrus germplasm native to Azad Jammu and Kashmir (Northern Pakistan) revealed by microsatellite markers. Afr J Biotechnol. 2010; 9: 8323–8333. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(TIF)

The numbers (1–93) represented code of accessions in sample list. ‘○’: Chinese white pear; ‘●’: Chinese sand pear; ‘□’: Japanese pear; ‘◊’: Korean pear; ‘♠’: Pyrus ussuriensis; ‘▲’: P. sinkiangensis; ‘♣’: Pakistani pear; ‘Δ’: P. pashia; ‘♫’: P. calleryana; ‘♯’: P. betulaefolia; ‘♦’: P. xerophila.

(TIF)

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.