Abstract

We assessed a multidimensional model of parent alcohol socialization in which key socialization factors were considered simultaneously to identify combinations of factors that increase or decrease risk for development of adolescent alcohol misuse. Of interest was the interplay between putative risk and protective factors, such as whether the typically detrimental effects on youth drinking of parenting practices tolerant of some adolescent alcohol use are mitigated by an effective overall approach to parenting and parental modeling of modest alcohol use. The sample included 1,530 adolescents and their mothers; adolescents’ mean age was 13.0 (SD = .99) at the initial assessment. Latent profile analysis was conducted of mothers’ reports of their attitude toward teen drinking, alcohol-specific parenting practices, parental alcohol use and problem use, and overall approach to parenting. The profiles were used to predict trajectories of adolescent alcohol misuse from early to middle adolescence. Four profiles were identified: two profiles reflected conservative alcohol-specific parenting practices and two reflected alcohol-tolerant practices, all in the context of other attributes. Alcohol misuse accelerated more rapidly from grade 6 through 10 in the two alcohol-tolerant compared with conservative profiles. Results suggest that maternal tolerance of some youth alcohol use, even in the presence of dimensions of an effective parenting style and low parental alcohol use and problem use, is not an effective strategy for reducing risky adolescent alcohol use.

Keywords: adolescent, alcohol misuse, parent socialization, alcohol-specific parenting practices

The negative consequences of adolescent alcohol use, especially heavier use (Heron, 2013; Windle & Windle, 2006), make adolescent alcohol misuse a leading public health problem and a keen concern of parents (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2007). The premise of the current study is that although multiple parental factors are thought to have substantial influence on adolescent alcohol use outcomes, the interplay among these factors is not adequately understood. As elaborated below, in prior research where multiple parental factors have been examined, the focus has tended to be on either unique effects or indirect effects of parental variables on youth alcohol use rather than interactions among multiple parental factors. Yet researchers have noted the complexity of relations among parent influences on youth alcohol and other substance use and the need to consider how these factors relate to each other in shaping adolescent behaviors (e.g., Barnes, Farrell, & Cairns, 1986; Chassin & Handley, 2006; Ennett, Foshee, Bauman, Hussong, Cai, Reyes, et al., 2008). We examine a model of parent alcohol socialization in which key socialization factors are considered simultaneously to identify combinations of factors that increase or decrease risk for development of adolescent alcohol misuse. Such an investigation allows for the possibility that putative risk and protective factors will be joined together in the same profile with potentially unexpected effects on adolescent alcohol misuse.

Theoretical Support for a Multidimensional Model

Social ecological theories of development such as Bronfenbrenner’s ecology of human development posit the importance of the joint effects of the multiple attributes characterizing the social contexts in which development takes place (Bronfenbrenner, 1977). Specific to the parent context, Darling and Steinberg (1993) propose an integrative model of parenting in which they theorize that the effects of parenting practices on adolescent behavior differ depending on the overall parenting context in which those practices are enacted. Parenting practices are domain-specific and refer, in this instance, to what parents do and say specific to children’s alcohol use behaviors. Parenting style, or parents’ overall approach to parenting, defines the context in which parenting practices are enacted. It is defined by the dual elements of demandingness and responsiveness—with the former referring to parental demands to bring about child conformity to societal and family expectations and the latter to parental support and reinforcement of the developing child’s individuality.

According to Darling and Steinberg’s integrative model, parenting style is posited to be relatively constant across a range of parent-child interactions, thereby indicating an overall approach to parenting. Parenting style is expected to moderate relations between domain-specific parenting practices and specific developmental outcomes. Darling and Steinberg argue that the effectiveness of parenting practices will be enhanced in the context of a parenting style marked by balanced and relatively high levels of demandingness and responsiveness (authoritative versus non-authoritative parenting style).

In a similar way, parents’ general attitude about teen drinking and their own established patterns of alcohol use can be understood to contribute to the context in which parenting practices specific to adolescent alcohol use take place and could moderate any effects of these parenting practices on youth drinking. For example, parent modeling of moderate alcohol use might enhance parenting practices intended to deter risky alcohol use whereas parental modeling of problem use might diminish the influence of protective practices.

Empirical Studies of Parental Factors and Adolescent Alcohol Use

Prior research has demonstrated the influence of multiple parental factors on youth alcohol use (for a review, see Ryan, Jorm, & Lubman, 2010), including both parenting style and parenting practice variables, as suggested by the integrative model, as well as parental attitude toward teen drinking and parents’ own alcohol use. Problematic parent alcohol use has consistently been shown to be a risk factor for adolescent alcohol use (Chassin, Flora, & King, 2004; Sieving, Maruyama, Williams, & Perry, 2000; Van den Zwaluw, Scholte, Vermulst, Buitelaar, Verkes, & Engels, 2008), as has parental alcohol use (Alati, Baker, Betts, Connor, Little, Sanson, et al., 2014; Latendresse, Rose, Viken, Pulkkinen, Kaprio, & Dick, 2008), although the evidence is more equivocal than for problem use.

Adolescents of parents with an authoritative compared with other parenting styles are less likely to use or abuse alcohol (for a review, see Cablová, Pazderková, & Miovský, 2014). When the two dimensions of parenting style have been examined separately, demandingness and other indicators of parental supervision or control have been found to be protective with respect to youth alcohol use ( Peterson, Hawkins, Abbott, & Catalano, 1994; Van der Vorst, Engels, Meeus, & Dekovi, 2006a; Van der Zwaluw et al., 2008), whereas parental responsiveness and other indictors of support have demonstrated both protective (Ennett et al., 2008; Latendresse, Rose, Viken, Pulkkinen, Kaprio, & Dick, 2009) and null associations (Van der Vorst et al. 2006a).

Permissive alcohol-specific parenting practices, including ease of access to alcohol at home (e.g., Komro, Maldonado-Molina, Tobler, Bonds, & Muller, 2007; Van den Eijnden, Van den Mheen, Vet, & Vermulst, 2011) and parental allowance of youth alcohol use (e.g., Danielsson, Romelsjö, & Tengström, 2011; Kaynak, Winters, Cacciola, Kirby, & Arria, 2014), consistently have been shown to increase the risk of adolescent alcohol use. Evidence is more limited for the protective effects of anti-alcohol socialization practices. Longitudinal studies of parental rules about adolescent drinking, for example, have reported protective, detrimental, and null effects (Jackson, Henriksen, & Dickinson, 1999; Mares, Lichtwarch-Aschoff, Burke, Van der Vorst, & Engels, 2012; Van der Vorst, Engels, Dekovi, Meeus, & Vermulst, 2007). Evidence is also equivocal for the relations between parent-child communication about alcohol and youth alcohol use (Andrews, Hops, Ary, & Tildesley, 1993; Ennett, Bauman, Foshee, Pemberton, & Hicks, 2001; Reimuller, Hussong, & Ennett, 2011), but communication is assumed to be a primary means by which parents convey alcohol-specific parenting practices.

Echoing findings on permissive alcohol-specific parenting practices, risk of alcohol use and misuse has been found to be higher among adolescents with parents holding a permissive attitude toward youth drinking (Fergusson, Lynskey, & Horwood, 1994; Koning, Van den Eijnden, Verdurmen, Engels, & Vollebergh, 2012). Risk tends to be lower among adolescents of disapproving parents (Andrews et al., 1993; Mares, Van der Vorst, Engels, & Lichtwarck-Aschoff, 2011; Sieving et al., 2000).

When multiple potential parent influences on development of youth alcohol use and misuse have been studied together, the focus typically has been on unique and indirect (mediated) effects rather than on interactions or joint effects. For example, studies that have included both alcohol-specific parenting practices and parenting style have assessed the unique effect of each controlling for the other (Jackson et al., 1999, Komro et al., 2007) or have examined parenting practices as mediators of parenting style effects (Van Zundert, Van der Vorst, Vermulst, & Engels, 2006; Van den Zwaluw et al., 2008). Interactions between alcohol-specific parenting practices and parenting style have not been examined. Similarly, studies of parent alcohol use have examined unique effects of parent alcohol use after accounting for other parenting variables (e.g., Alati et al., 2014) or focused on parental mediators of any influence on youth alcohol use; for example, whether the mechanism of effect is through communication with the child about alcohol (Mares et al., 2011), rules about alcohol use (e.g., van der Vorst, Engels, Meeus, & Dekovi, 2006b; van Zundert et al., 2006), or exposure to adult intoxication (Kerr, Capaldi, Pears, & Owen, 2012). Rarely have studies examined interactions among parent variables (Ennett et al., 2008).

Some recent studies of adolescent alcohol use, however, have applied latent profile analysis to identify patterns of influence among multiple parent variables. Latent profile analysis is an analytic approach for assessing interactions–or joint effects–among multiple factors (Collins & Lanza, 2010; Flaherty & Kiff, 2012). Three studies have used this approach to identify patterns among parenting variables that characterize discrete parenting profiles and examined relationships between the profiles and adolescent alcohol use (Koning et al, 2012; Latendresse et al, 2009; Luyckx, Tildesley, Soenens, Andrews, Hampston, Peterson et al., 2011). Two of these studies measured profiles based on indicators of general parenting, such as knowledge of the child’s whereabouts and positive parenting (Latendresse et al., 2009; Luyckx et al., 2009) and the third measured profiles based on adolescents’ perceptions of alcohol-specific parenting, such as perceived rule-setting and communication about alcohol use (Koning et al., 2012). None, however, included indicators of both parenting practices and parenting style together in the analysis, as would be suggested by the integrative model, or took into account the role of parent alcohol use or attitude toward teen drinking. Nevertheless, all three studies showed that adolescents with parent profiles characterized by either more positive general parenting or by less permissive alcohol-specific parenting practices compared with other profiles were at lower risk on alcohol outcomes.

Current Study

We use latent profile analysis (LPA) to examine how alcohol-specific parenting practices, parent alcohol use and problem use, mother’s attitude toward adolescent drinking, and dimensions of parenting style interrelate in influencing adolescent alcohol misuse. As described in the methods, all these socialization factors are based on mother’s reports.

Building on results of prior studies, we hypothesize identification of at least two profiles: an alcohol-intolerant parental profile and an alcohol-tolerant parental profile. We expect the former to be characterized by anti-alcohol use parenting practices and a disapproving maternal attitude toward adolescent alcohol use, and the latter to be characterized by parenting practices permissive of alcohol use and a less disapproving attitude toward adolescent drinking. Following from the integrative model of parenting, the interplay between parenting practices and parenting style is of interest. Of perhaps particular interest is whether a tolerant profile is identified that places permissive attitudes and practices in the context of overall effective parenting and modest parental drinking and whether such a combination is shown to have a protective effect on adolescent alcohol misuse. Similarly, given our extension of the parenting context to include parent alcohol use, it is of interest whether an alcohol intolerant profile is identified in the context of higher parent alcohol use or problem use and to what effect on adolescent drinking.

Method

Study Design

Data are from adolescents and mothers who participated in a longitudinal study of the influence of family and other contextual factors on development of adolescent alcohol and other substance use. The study used a cohort sequential design in which all eligible 6th, 7th, and 8th grade students in three complete public school systems in North Carolina were entered into the study and surveyed in school every 6 months, from spring 2002 through spring 2004, for a total of five waves (N=5,220 at wave 1). Students were in the 8th, 9th, and 10th grades at the completion of the study. A simple random sample of parents of the adolescents was interviewed at the first wave of data collection (N=1,663). All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the investigators.

Adolescent Sample and Data Collection

At each wave, all students in the targeted grades were eligible for the study unless they were exceptional children in self-contained (not regular) classrooms or were unable to complete the survey due to limited English reading skills, and whose parents did not refuse their participation and who themselves provided written assent to participate in the study. The student sample ranged in size from 5,220 (wave 1) to 5,017 (wave 5) with 6,891 unique cases across all waves; response rates for waves 1–5 were 88.4%, 81.3%, 80.9%, 79.1, and 76.0%, respectively. Approximately one-third of students were in each of the three grade cohorts.

Trained data collectors administered questionnaires on at least two occasions to reduce the effect of absenteeism on the response rates. Teachers stayed in classrooms to help maintain order but did not answer questions or walk around the classroom. Adolescents completed the questionnaire in approximately 1 hour.

Parent Sample and Data Collection

A simple random sample of 2,215 parents was selected from all parents of adolescents who participated in the wave 1 data collection, excluding those who had more than one child in the study and who were unable to complete the telephone interview in English. Of this sample, 1,663 (75.1%) completed a 25-minute telephone interview. By design, preference was given to interviewing mothers because of their typically greater involvement in child socialization.

Analytic Sample

Of the 1,663 pairs of participating adolescents and parents, we restricted the analytic sample to those pairs in which the mother was the participating parent (98.3%), the mother self-identified as either White or Black (96.7%), data were complete for parent education and family structure (92.0%), and the adolescent provided the alcohol misuse outcome measure for at least one wave of data collection (99.4%) (N=1,530; 92.0%). We excluded mothers who reported their race/ethnicity as other than White or Black because of their small numbers. In the final sample (N = 1,530) 60.3% of mothers were White and 39.7% Black; 45.4% of mothers had a high school education or less; 32.3% had some college education or had graduated from community college or technical school; and 22.3% had a college education or more. Most adolescents reported the same race/ethnicity as their mother: 57.9% White and 37.0% Black; 5.1% reported another race/ethnicity. Adolescents were 48.2% male; 66.8% lived in a household with two parents; and the mean age at wave 1 was 13.0 years (SD=.99).

Measures

All alcohol socialization measures were based on mother reports. Mothers answered questions for themselves or the household for the attitude and alcohol-specific parenting practices questions, and for themselves and the adolescent’s father, if the father lived in the same home or lived elsewhere but was engaged in child rearing, for the parenting style and alcohol use questions. We used mothers’ responses for themselves and, as available, for fathers for the latter measures because we wanted to capture as much of the parenting context as possible, while recognizing the heterogeneity in family structures. Descriptive statistics for the variables used to define parent alcohol socialization profiles are presented in Table 1. Adolescent alcohol misuse was based on adolescent reports. Demographic measures were based on self-reports of either the adolescent or mother, as applicable.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for the Alcohol Socialization Factors

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Mother’s attitude toward adolescent alcohol use | -- | .12 | −.11 | −.03 | −.04 | .00 | .07 | .07 |

| 2. | Mother’s communication about negative consequences of alcohol use | -- | −.04 | −.17 | −.12 | .05 | .08 | .09 | |

| 3. | Mother’s permissive communication about alcohol use | -- | .40 | .27 | .05 | .01 | .05 | ||

| 4. | Perceived accessibility of alcohol at home | -- | .33 | .15 | −.00 | .00 | |||

| 5. | Parent alcohol use | -- | .24 | −.03 | −.05 | ||||

| 6. | Parent problem alcohol use | -- | −.12 | −.22 | |||||

| 7. | Parent demandingness | -- | .42 | ||||||

| 8. | Parent responsiveness | -- | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Range | 1–5 | 0–3 | 0–3 | 1–4 | 0–30 | 0–1 | 1–4 | 1–4 | |

| Mean (SD) | 4.72 (.44) | 2.57 (.87) | .59 (.89) | 1.61 (1.00) | 4.30 (5.46) | .10 (.30) | 3.65 (.47) | 3.77 (.32) | |

| α | .66 | .79 | .61 | -- | -- | -- | 0.68 | 0.69 | |

| N | 1529 | 1530 | 1530 | 1529 | 1529 | 1525 | 1530 | 1530 | |

Note. Bold correlation coefficients are significant at p < .05 or better.

Mother’s attitude toward adolescent alcohol use

The measure was formed from averaging two items that asked mothers how disappointed they would be to discover that the adolescent had a drink of alcohol and that the adolescent had gotten drunk. Responses ranged on a 5-point scale from “not at all” (1) to “extremely” (5). Mothers were not asked about fathers’ attitudes about adolescent drinking.

Mother’s alcohol-specific parenting practices

We measured three practices: communication with the child about the negative consequences of alcohol use, permissive communication about alcohol use, and perceived ease of alcohol accessibility at home. The two measures of communication were constructed as sums using a series of yes/no questions about things the mother might have told her child about alcohol use. Both communication about negative consequences (e.g., “drinking can cause loss of control”) and permissive communication (e.g., “under some circumstances, it’s okay to have sips of a drink”) were measured by three items each. Perceived alcohol accessibility at home was measured by a single item that asked how difficult or easy it would be for the adolescent to get alcohol at home; response options ranged from “very difficult” (1) to “very easy” (4).

Parent alcohol use

We measured parents’ frequency-quantity of alcohol use and problem alcohol use. Mothers were asked about their own alcohol use and, if applicable, the adolescent’s father’s alcohol use. Separate frequency-quantity measures were formed for mothers and fathers and the highest value of the two was used to capture the maximum exposure to alcohol likely experienced by the adolescent. The measures were formed from the product of the number of days in the past 3 months the parent had 1 or more drinks of alcohol and the usual amount of alcohol consumed on those occasions. The frequency measure ranged from no days (0) to almost every day (6) and the quantity measure ranged from 1 drink (1) to 5 or more drinks (5), yielding a range of 0 to 30. Problem alcohol was measured by a single item, asked separately for the mother and father, about whether drinking had ever caused the parent to have any problems (Cuijpers & Smit, 2001). The variable was coded to capture any adolescent exposure to parent problem use by contrasting one or both parents having problems versus neither.

Parenting style

Items measuring the two dimensions of parenting style—demandingness and responsiveness—were asked separately for mothers and, if applicable, fathers, using six items from the Authoritative Parenting Index (Jackson, Henriksen, & Foshee, 1998); the parent means were averaged to form the measures. Response categories for the items ranged on a four-point scale from “never” (1) to “often” (4). Demandingness was measured by three items per parent (e.g., “you tell (child) times when he/she must come home”). Responsiveness also was measured by three items per parent (e.g., “you tell (child) when he/she does a good job on things”).

Adolescent alcohol misuse

We used a scale of alcohol misuse based on eight adolescent self-report items about recent alcohol use. Items measured problematic levels of use (e.g., “had 5 or more drinks in a row,” “gotten drunk or very high from drinking alcoholic beverages”) and negative consequences associated with use (e.g., “gotten into a physical fight because of drinking”). Each item had five response categories ranging from “none” (0) to “10 or more times” (4) in the past three months. We used item response theory (IRT) to construct the scale of adolescent alcohol misuse (Thissen, Nelson, Rosa, & McLead, 2001). After dichotomizing ordinal item responses (any endorsement of the item versus none), we used MULTILOG software to run 2-parameter logistic IRT models, simultaneously fitted to all five waves of data to compute expected a posteriori (EAP) scores (Thissen, Chen, & Bock, 2003). This method is preferred over the more conventional sum and average approach when the response distribution is highly skewed, which is expected when quantifying alcohol misuse among a general population sample of young people in the age range we examined. Due to missingness of some items during the construction of this scale, multilevel multiple imputation techniques (Schaefer, 2001) were used to create five sets of imputed data.

Levels of alcohol misuse among the sample were relatively comparable to those of youth in the national general population. The percentages of youth in wave 5, surveyed in 2004, who reported having been recently drunk were 8.7% and 19.3% of 8th and 10th graders, respectively, in the current sample compared with 6.2% and 18.5% of 8th and 10th graders in the national Monitoring the Future study; even so the reference periods differed in being the past 3 months for the current study versus the past 30 days for the national study (Johnston, Bachman, O’Malley, Schulenberg, & Miech, 2014).

Demographics

Adolescent sex was coded so the reference group was female. Mother’s race/ethnicity was coded so the reference group was White. Parent education was coded as high school graduate or less (reference group) versus some college or more based on the highest level reported for the mother and, if applicable, the father. Family structure was coded to contrast two parent families (reference group) with single parent families. Grade cohort was coded with the wave 1 values of 6, 7, or 8.

Analysis

Using Mplus Version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2014), we conducted a latent profile analysis (LPA) of the alcohol socialization measures. Four fit indices were used in choosing the optimal latent class model. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) measure how closely the model fits the data, adjusting for the number of parameters; lower values indicate a better balance of fit and parsimony. The Vuong Lo Mendell Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT) tests the null hypothesis that a model with k classes does not provide a closer fit to the data than a model with one fewer class; thus, as models with a successively larger number of classes are tested, the chosen model is the one with the greatest number of classes before the LRT result becomes non-significant. Finally, entropy is a measure of class separation, with values between zero and one; higher values indicate greater classification certainty (or class separation).

Following the selection of an optimal number of classes, we re-ran the model including the demographic variables as auxiliary variables in order to determine whether there were any demographic differences between the classes, without altering the class solution itself (Clark & Muthén, 2009; Wang, Brown, & Bandeen-Roche, 2005). Three demographic covariates—mother race/ethnicity, parent education, and family structure—showed some significant differences between profiles. Neither adolescent grade at wave 1 nor sex showed significant differences between the classes; however, given that our goal was to link the class solution with time-varying alcohol misuse variables, we considered it important to control for individually-varying starting times by including adolescent grade at wave 1. Thus, our final model included mother race/ethnicity, parent education, family structure, and adolescent grade at wave 1 as covariates.

After selecting the latent profile model, we then used the three-step approach of Asparouhov & Muthén (2014) to determine whether the parenting profiles were linked to adolescent alcohol misuse trajectories. The first step refers to the estimation of the LPA described above. The second step involves assignment of each case to a profile on the basis of these LPA results, where assignment is made with uncertainty. In the third step, the individual class assignments are linked to the alcohol use trajectories of the adolescents of the parents assigned to each profile while taking into account the measurement error of the latent profile assignment variable. This is done by obtaining estimates of the misclassification rates from the latent profile model, and including these as probabilities in a secondary model that includes the outcome variable (Vermunt, 2010). This secondary model is a growth curve model of the alcohol misuse scores from the spring semester of sixth grade through spring semester of tenth grade. Each adolescent contributed alcohol misuse scores a maximum of five time points, corresponding to the five waves of data collection. But because of the cohort sequential design, alcohol misuse scores were available for all nine time points for the semesters from spring of sixth grade to spring of tenth grade. The alcohol misuse trajectory for each profile was modeled and between profile comparisons in alcohol misuse trajectories were made after adjusting for measurement error. Post-hoc Wald tests for the latent curve model were performed in order to test whether the intercept and slope differed between levels of the profile variables. A separate Wald test was performed on each pairwise combination of levels of the profile variable; Wald tests were done separately for intercept and slope. Importantly, we did not correct for multiple comparisons and consider the results to be exploratory. Because the alcohol misuse score variable was generated using multiple imputation, we performed this portion of the analyses on each imputed dataset and pooled parameter estimates over datasets. All analyses were conducted in MPlus.

Results

Class enumeration

Fit indices for the unconditional model without demographic covariates are shown in Table 2. The AIC and BIC decreased steadily as the number of classes increased, indicating that no one model provided the best balance of fit and parsimony. Entropy was greatest in the 2-class solution, followed by the 4-class solution. The LRT favored a 4-class solution, as this was the greatest number of classes for which the test was significant. We proceeded with the 4-class model because the LRT favored this solution; solutions with a greater number of classes tended to have either trivially small classes or simply subdivided the larger classes into very similar classes. Additionally, the 4-class model yielded interpretable results from an empirical and theoretical perspective.

Table 2.

Fit Indices for Unconditional Latent Profile Analysis of the Parenting Factors

| Unconditional Model

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 classes | 3 classes | 4 classes | 5 classes | |

| AIC | 23162.29 | 22562.02 | 22286.27 | 22051.71 |

| BIC | 23338.58 | 22818.44 | 22622.82 | 22468.40 |

| LRT p value | .00 | .00 | .01 | .14 |

| Entropy | .92 | .81 | .86 | .84 |

Note. AIC = Akaike information criteria; BIC = Bayesian information criteria; LRT = Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test.

Fit indices from the model containing demographic covariates were similar to those in the unconditional model, in that the AIC and BIC decreased steadily with an increasing number of classes. Unlike the unconditional model, the LRT favored the 3-class solution over the 4-class solution. However, the LRT (like the AIC and BIC) penalizes model complexity, which increases dramatically when covariates are included; as such, including covariates when deciding on the number of classes can result in selecting a model with too few classes (Tofighi & Enders, 2007). Thus, we chose to proceed with the 4-class solution in the conditional model as well, due to its similarity to the unconditional 4-class solution. The fact that the classes themselves did not change greatly between the unconditional and conditional 4-class solutions is evidence that there were no omitted covariate effects (Muthén, 2004).

The four-profile model

Table 3 shows the pattern of indicators for the final model, a 4-class model with demographic covariates included. Classification probabilities are shown in the top row of the table. These values (ranging from zero to one) indicate the probability that an individual classified into a given class k is truly a member of that class; higher values suggest less measurement error in a latent class variable. Classification is quite good for all four classes, with correct classification rates mostly around 90%. Class four shows somewhat more measurement error than the other classes, but still shows relatively good classification. Odd ratios for the likelihood of profile membership (with the conservative class described below as the reference class) by the demographic covariates are shown at the bottom of the table. After controlling for other demographic variables, the classes did not differ on adolescent grade at wave 1, indicating that profiles can be taken as relatively consistent across grade levels.

Table 3.

Latent Classes of Parent Alcohol Socialization

| Class One Conservative 53.01% (n=811) | Class Two Conservative, Low Authoritative 11.57% (n=177) | Class Three Tolerant, Low Parental Use 29.15% (n=446) | Class Four Tolerant, High Parental Use 6.26% (n=96) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classification probability | .95 | .90 | .89 | .83 |

| Disapproving attitude Negative consequences communication | 4.74 | 4.67 | 4.73 | 4.62 |

| 0 messages (%) | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.18 |

| 1 messages (%) | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.04 |

| 2 messages (%) | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.05 |

| 3 messages (%) | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.64 | 0.73 |

| Permissive communication | ||||

| 0 messages (%) | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.27 | 0.48 |

| 1 messages (%) | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.39 | 0.31 |

| 2 messages (%) | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.12 |

| 3 messages (%) | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.04 |

| Alcohol accessibility | ||||

| Very difficult (%) | 0.92 | 0.77 | 0.21 | 0.59 |

| Somewhat difficult (%) | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0.18 |

| Somewhat easy (%) | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.26 | 0.14 |

| Very easy (%) | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.26 | 0.10 |

| Frequency-quantity of use | 1.15 | 3.53 | 7.3 | 17.25 |

| Problem use (%) | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| Demandingness | 3.81 | 2.71 | 3.74 | 3.70 |

| Responsiveness | 3.84 | 3.38 | 3.82 | 3.76 |

| Logistic regression results relating classes to covariates | ||||

| Grade level at wave 1 | Reference | .08 | .07 | .03 |

| Black | Reference | −.20 | −1.56**** | −1.55** |

| Parent education | Reference | 0.20 | 1.25*** | −.26 |

| Family structure | Reference | 1.77*** | −.13 | −.04 |

Note. Model controls for adolescent grade in wave 1, mother race/ethnicity, parent education, and family structure.

p < .01.

p < .001.

p < .0001.

The majority of the sample (53.01%) was characterized by a conservative pattern of alcohol socialization. Mothers in this class were highly likely to report having communicated three or more messages about the negative consequences of alcohol and no permissive messages related to alcohol use to their adolescents. Further, 92% of them reported that their adolescents would have a very difficult time obtaining alcohol in their homes. Mothers in this class reported high levels of parental demandingness and responsiveness, a disapproving attitude toward their adolescent’s alcohol use, and low levels of alcohol use by themselves and fathers. A second class, the conservative, low-authoritative profile (11.57% of sample) was distinguished from the conservative profile in having comparatively lower scores on the demandingness and responsiveness scales measuring parenting style. A substantial fraction of mothers in this class, 22%, reported problem alcohol use for themselves or fathers. Additionally, these mothers were significantly more likely to be in a single-parent household than mothers in the conservative class (p < .001). Taken together, the results for these two classes indicate that the majority of the sample (roughly 65%) was characterized by relatively conservative alcohol-specific socialization, with differences between conservative profiles being mainly in parenting style and parental problem drinking history.

The remainder of the sample broke into two classes, each of which was characterized by somewhat more tolerant alcohol-specific practices. The tolerant, low parental use profile (29.15% of the sample) was most permissive with regard to alcohol-related messaging; these mothers communicated fewer negative messages and more permissive messages about alcohol and were more likely than any other class to perceive that their children had easy home access to alcohol. They reported relatively low levels of parent alcohol use, a disapproving attitude toward adolescent drinking, and high levels of parental demandingness and responsiveness. They were more likely to be White (p < .0001) and to have attained higher education levels (p < .001) than mothers in the referent conservative class.

Finally, the profile containing the smallest portion of the sample, the tolerant, high parental use profile (6.26% of the sample), was distinguished from the other tolerant class mainly by parental alcohol use: mothers in this class reported high quantity-frequency of alcohol use for themselves and/or fathers, as well as relatively frequent problem use. Their messaging about alcohol was only slightly less permissive than their low-use counterparts, and they showed almost no differences from the other profiles in parenting style. These mothers were more likely to be White than those in the conservative class (p < .01), but unlike the tolerant, low parental use class, did not show higher levels of education.

Linking the profiles to outcomes

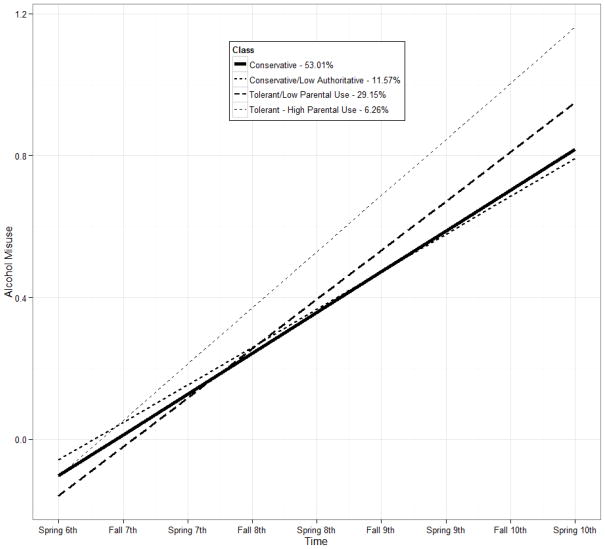

Figure 1 shows the estimated trajectories of adolescent alcohol misuse for the four profiles. The trajectories were estimated as growth curve models with an intercept and slope factor. Because these factors were estimated as a secondary model in the three-step latent class analysis framework (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014), they are adjusted for measurement error. Note that the demographic covariates were not included as covariates because they were included in the enumeration of classes. As shown, all of the adolescents in the sample increased in drinking from fall of sixth grade to spring of tenth grade. However, the smallest increases in drinking over this time period were among adolescents linked with profiles characterized as conservative (i.e., the conservative and conservative, low authoritative classes). Steeper increases over time were observed among adolescents whose mothers were permissive in their alcohol-related communication (i.e., the tolerant, low parental use profile and the tolerant, high parental use profile). The most substantial increases in drinking were seen among adolescents in the latter class whose mothers communicated permissive messages about alcohol and whose mother and/or father drank heavily.

Figure 1.

Adolescent alcohol misuse trajectories by parenting profile

Post-hoc tests comparing the intercept and slope factors of each profile’s trajectory were conducted. These analyses are considered exploratory because their significance levels depend on the sample size of each class and are not adjusted for multiple comparisons. No significant differences were expected between the intercepts given that all of the adolescents drank relatively little in the fall of sixth grade. The intercept for the tolerant, low parental use profile, however, was marginally lower than those of the conservative and conservative, low authoritative profiles, χ2(1) = 3.364, p = .0667 and χ2(1) = 3.032, p = .0816, respectively. Comparisons between slopes showed that the slope of alcohol misuse for the tolerant, low parental use group was significantly steeper than those for both the conservative class, χ2(1) = 5.741, p = .0166, and the conservative, low authoritative class, χ2(1) = 3.978, p = .0461. Similarly, the slope of alcohol misuse for the tolerant, high parent alcohol use group differed significantly from those of both the conservative class, χ2(1) =4.135, p = .0420, and the conservative, low authoritative class, χ2(1) = 4.035, p = .0446. No other differences were significant. These results are similar to those suggested by Figure 1, namely that alcohol tolerant parenting profiles compared with conservative profiles are linked to more substantial increases in alcohol misuse between sixth and tenth grade.

Discussion

Our investigation of multiple parent factors expected to influence adolescent alcohol misuse was motivated by the contextual theoretical perspective of Bronfenbrenner’s ecology of human development (Bronfenbrenner, 1977). This theory emphasizes the need for holistic study of the social contexts in which children are embedded and the particular importance of interactions among defining contextual factors. Our investigation also was motivated by Darling and Steinberg’s integrative model of parenting, which differentiates between general parenting style and domain-specific parenting practices and posits the moderating effect of parenting style on parenting practices (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). We extended the logic of the integrative model by including parent alcohol use and problem use and mother’s attitude toward teen drinking to more fully define the context of parent alcohol socialization. The results of our latent profile analysis indicate the usefulness of analyzing joint effects of parenting variables.

Consistent with theoretical expectations, varying patterns of alcohol socialization among parents were evident in the four profiles identified, with two profiles reflecting conservative, anti-alcohol socialization and two reflecting alcohol tolerant socialization. Youth with parents in tolerant compared with conservative profiles showed greater acceleration in alcohol misuse over the developmental period from middle to high school. Mothers’ reports of alcohol-specific parenting practices were the primary factors distinguishing these profiles and likely account for the differential profile effects on youth alcohol misuse development. What mothers communicated to their adolescents about alcohol use—in particular, permissive messages and practices that signaled tolerance of use even if only in some circumstances—differentiated the trajectories of adolescent misuse alcohol for the two conservative versus two tolerant profiles. These results are consistent with prior research demonstrating that parental permissiveness for youth alcohol use is associated with increased risk of alcohol use (Jackson, Ennett, Dickinson, & Bowling, 2012; Kaynak et al., 2014).

According to our theoretical perspectives, however, the effects of alcohol-specific parenting practices should be expected to differ depending on the values of the other parent variables. In the second, less common conservative profile, the context for high levels of anti-alcohol parenting practices was characterized by low levels of parent demandingness and responsiveness and high levels of parent problem alcohol use. The steeper plotted trajectory of adolescent alcohol misuse linked with this parenting profile compared with the more common conservative profile could reflect the diminished effect of parenting practices in the context of less than optimal parenting, as predicted by the integrative model of parenting, or the countering effect of parent modeling of problem alcohol use. But the trajectories linked to the two conservative profiles did not differ from each other, suggesting that anti-alcohol parenting practices were the driving influence.

The two alcohol tolerant profiles were both characterized by permissive alcohol-specific parenting practices in the context of authoritative parenting as indicated by high demandingness and responsiveness. Trajectories of alcohol misuse linked with these profiles were both steeper than for the conservative profiles. The detrimental effect of this combination of parenting practices and parenting style on the adolescent alcohol misuse trajectories suggests that the protective effect of an authoritative parenting style (e.g., Cablová et al., 2014) can be diminished in the presence of permissive parenting practices. Alternatively, and more consistent with the integrative model, the findings could reflect detrimental effects of permissive parenting practices being enhanced in the context of more authoritative parenting. The tolerant profiles differed in parent alcohol use—low parental alcohol use and misuse in the more common of the two tolerant profiles and high parental problem use in the less common tolerant profile. The steepest trajectory of alcohol misuse was in the latter profile, where problem use could be expected to exacerbate effects of permissive practices. Although the trajectory of alcohol misuse was less steep in the alcohol tolerant profile characterized by low parent alcohol use, the trajectories of the two tolerant profiles did not significantly differ from each other. Again, the driving force appears to have been parenting practices; in this instance, permissive practices.

It is noteworthy that we found no differentiation in profiles by the measure of mother’s attitude toward the adolescent’s alcohol use. All mothers were disapproving of alcohol use by their teens, yet they differed in their approach to preventing teen use. There were differences in profile membership by some demographic characteristics: white mothers and those who had attained higher education levels were more likely to belong to the tolerant, low parental alcohol use profile than the common conservative profile. Almost 30% of mothers in our sample were associated with this profile. This finding is consistent with the suggestion in the literature that a substantial proportion of parents, particularly more highly educated parents (Ennett et al., 2001; Jackson et al., 2012), take a tolerant approach to adolescent alcohol use. As noted above, parental tolerance of youth alcohol use in the context of an authoritative parenting style and in the presence of modest parental alcohol use did not deter risky adolescent alcohol use. More highly educated mothers may be a target for family-based interventions to reduce risk of adolescent alcohol misuse.

Our results add to those of the small number of studies that have examined adolescent alcohol use outcomes in the context of profiles of parenting measured by a latent class approach (Koning et al., 2012; Latendresse et al., 2009; Luyckx et al., 2011). Consistent with prior studies, our findings showed that profiles characterized as permissive in alcohol-specific parenting practices conveyed more risk to adolescents than those characterized as more strict (Koning et al., 2012), as did those characterized by more indulgent rather than more attentive general parenting (Latendresse et al., 2009; Luckx et al., 2013). Although none of these adolescent studies considered both parenting practices and parenting style together or included parent alcohol use, a study of college students did include a broad set of parenting characteristics (Abar, Turrisi, & Mallett, 2014). Similar to the findings of the current study, a pro-alcohol parenting profile was characterized by heavy parental alcohol use and perceived high levels of parent approval of alcohol use; college students in this group had the highest initial levels of alcohol use as well as the greatest increases in weekend drinking over time.

Our results should be considered in the context of several study limitations. Regarding the measures, mother’s attitude toward adolescent alcohol use was measured by only two items and was reflective of only mothers, which may have diminished its usefulness. With one exception, alphas for the other alcohol socialization measures ranged between .61 and .69 and thus were lower than desirable. The attitude measure and parenting practices measures were based on mothers’ reports for themselves only, whereas the measures of parent alcohol use and misuse and parenting style dimensions were based on mothers’ reports for themselves and for fathers, as available. For the latter measures, we collapsed the indicators to create parent measures rather than separate measures for the mother and fathers, thus obscuring differences in mother and father influence, which are known to exist (e.g., Andrews et al., 1993; Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2006). Our collapsed measures, however, allowed comparability of these parent measures for two parent and single parent households and provided a fuller accounting of the context in which alcohol socialization takes place. Different profile results likely would have been obtained if we had separate measures for mothers and fathers for all of the parenting indicators. We did not have a measure of rules about adolescent alcohol use; rules have been identified in the literature as a potentially important strategy for preventing alcohol misuse. On the study sample, although it was drawn from the general population, with high response and low attrition rates, it was a local sample and results may not be generalizable beyond the participating families.

Other limitations rest primarily in the analysis strategy. The latent profiles were based on measures obtained at the first wave of data collection. Although the profiles did not vary by the wave 1 grade of the cohorts (grades 6 to 8), the profiles may well have varied over the entire grade span of 6 to 10 if measured longitudinally (Koning et al., 2012). The profiles obtained from this analysis are best regarded as useful summaries of interactions between socialization variables in the dataset, and should not be reified as definitive classes of parenting. Additionally, the tests of differences between classes in terms of intercept and slope parameters for trajectories of adolescent alcohol misuse relied on repeated use of linear contrasts, and should be regarded as exploratory; with the development of more systematic tests of the differences in parameters between classes, our expectations about between-class differences in trajectories should be retested in other studies.

In linking the parenting profiles to outcomes, we have proceeded with caution. Profile membership is based on estimates that are subject to classification uncertainty. Since membership to each profile is estimated from the data and not known a priori, some individuals will be misclassified (Collins & Lanza, 2010). This could have been a particular problem for the tolerant, high parental alcohol use profile, as this was the smallest class with the highest degree of classification error; estimates of the differences between this class and the others might be somewhat less stable. However, our use of the new three-step approach of linking latent profiles to trajectories (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014), which allows for classification error to be taken into account directly, was able to partially address this problem. Our approach represents a significant improvement over traditional methods that do not account for uncertainty of profile membership and often yield biased estimates of the relation between classes and outcomes.

Conclusion

Our multidimensional model of parenting factors and methodological strategy extend understanding of parental influence on adolescent alcohol misuse by identifying patterns of maternal and parental factors predictive of adolescent alcohol misuse. The two most common profiles identified were a conservative profile characterized by mothers’ anti-alcohol socialization and a tolerant profile characterized by alcohol-tolerant socialization. Both profiles were characterized by low parent alcohol use, mothers’ disapproving attitude toward adolescent alcohol use, and attributes of an effective parenting style. Across all four profiles, alcohol-specific parenting practices appeared to be the driving influence, with those effects marginally increased or decreased by interrelations with the other parent socialization variables. The steeper rate of adolescent alcohol misuse linked with the tolerant compared with the conservative profile does not support an alcohol-tolerant approach to preventing risky alcohol misuse among adolescents even in the presence of other protective factors, such as low parental alcohol use.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R01 DA13459) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (5T32HD007376-24).

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Susan T. Ennett, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Christine Jackson, RTI International.

Veronica T. Cole, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Susan Haws, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Vangie A. Foshee, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Heathe Luz McNaughton Reyes, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Alison Reimuller Burns, Children’s National Health System.

Melissa J. Cox, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Li Cai, University of California at Los Angeles.

References

- Abar CC, Turrisi RJ, Mallett KA. Differential trajectories of alcohol-related behaviors across the first year of college by parenting profiles. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28(1):53–61. doi: 10.1037/a0032731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alati R, Baker P, Betts KS, Connor JP, Little K, Sanson A, Olsson CA. The role of parental alcohol use, parental discipline and antisocial behaviour on adolescent drinking trajectories. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014;134:178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Hops H, Ary DV, Tildesley E. Parental influence on early adolescent substance use: Specific and nonspecific effects. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 1993;13(3):285–310. doi: 10.1177/0272431693013003004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: 3-step appraoches using mplus. 2013. Mplus Web Notes: No. 15 ed. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Farrell MP, Cairns A. Parental socialization factors and adolescent drinking behaviors. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1986;48(1):27–36. doi: 10.2307/352225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist. 1977;32(7):513–531. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cablová L, Pazderková K, Miovský M. Parenting styles and alcohol use among children and adolescents: A systematic review. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy. 2014;21(1):1–13. doi: 10.3109/09687637.2013.817536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Flora DB, King KM. Trajectories of alcohol and drug use and dependence from adolescence to adulthood: The effects of familial alcoholism and personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113(4):483–498. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.483. Retrieved from https://auth.lib.unc.edu/ezproxy_auth.php?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2004-20178-001&site=ehost-live&scope=site. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Handley ED. Parents and families as contexts for the development of substance use and substance use disorders. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20(2):135–137. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S, Muthén B. Relating latent class analysis results to variables not included in the analysis. 2009 Retrieved, 2014, Retrieved from https://www.statmodel.com/download/relatinglca.pdf.

- Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. Hoboken, N.J: John Wiley & Sons; 2010. Retrieved from http://search.lib.unc.edu?R=UNCb6059135. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Smit F. Assessing parental alcoholism: A comparison of the family history research diagnostic criteria versus a single-question method. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26(5):741–748. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00155-6. Retrieved from https://auth.lib.unc.edu/ezproxy_auth.php?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2002-06536-011&site=ehost-live&scope=site. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsson A, Romelsjö A, Tengström A. Heavy episodic drinking in early adolescence: Gender-specific risk and protective factors. Substance use & Misuse. 2011;46(5):633–643. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2010.528120. Retrieved from https://auth.lib.unc.edu/ezproxy_auth.php?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2011-05188-008&site=ehost-live&scope=site. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113(3):487–496. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Foshee VA, Pemberton M, Hicks KA. Parent-child communication about adolescent tobacco and alcohol use: What do parents say and does it affect youth behavior? Journal of Marriage & the Family. 2001;63(1):48–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00048.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Hussong A, Cai L, Reyes LHM, DuRant R. The social ecology of adolescent alcohol misuse. Child Development. 2008;79(6):1777–1791. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01225.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ. Childhood exposure to alcohol and adolescent drinking patterns. Addiction. 1994;89(8):1007–1016. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty BP, Kiff CJ. Latent class and latent profile models. In: Cooper H, Camic PM, Long DL, Panter AT, Rindskopf D, Sher KJ, editors. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2012. pp. 391–404. Retrieved from https://auth.lib.unc.edu/ezproxy_auth.php?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2011-23865-019&site=ehost-live&scope=site. [Google Scholar]

- Heron M. Deaths: Leading causes for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2013 Jul 22;62(6) 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C, Ennett ST, Dickinson DM, Bowling JM. Letting children sip understanding why parents allow alcohol use by elementary school-aged children. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2012;166(11):1053–1057. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C, Henriksen L, Dickinson D. Alcohol-specific socialization, parenting behaviors and alcohol use by children. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60(3):362–367. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.362. Retrieved from https://auth.lib.unc.edu/ezproxy_auth.php?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=1999-13806-010&site=ehost-live&scope=site. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C, Henriksen L, Foshee VA. The authoritative parenting index: Predicting health risk behaviors among children and adolescents. Health Education & Behavior. 1998;25(3):319–337. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2013: Volume I, secondary school students. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kaynak O, Winters KC, Cacciola J, Kirby KC, Arria AM. Providing alcohol for underage youth: What messages should we be sending parents? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:590–605. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr DCR, Capaldi DM, Pears KC, Owen LD. Intergenerational influences on early alcohol use: Independence from the problem behavior pathway. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24(3):889–906. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komro KA, Maldonado-Molina M, Tobler AL, Bonds JR, Muller KE. Effects of home access and availability of alcohol on young adolescents’ alcohol use. Addiction. 2007;102(10):1597–1608. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koning IM, Van den Eijden R, Verdurmen JEE, Engels RCME, Vollebergh WAM. Developmental alcohol-specific parenting profiles in adolescence and their relationships with adolescents’ alcohol use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2012;41(11):1502–1511. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9772-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latendresse SJ, Rose RJ, Viken RJ, Pulkkinen L, Kaprio J, Dick DM. Parenting mechanisms in links between parents’ and adolescents’ alcohol use behaviors. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32(2):322–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00583.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latendresse SJ, Rose RJ, Viken RJ, Pulkkinen L, Kaprio J, Dick DM. Parental socialization and adolescents’ alcohol use behaviors: Predictive disparities in parents’ versus adolescents’ perceptions of the parenting environment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38(2):232–244. doi: 10.1080/15374410802698404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luyckx K, Tildesley EA, Soenens B, Andrews JA, Hampson SE, Peterson M, Duriez B. Parenting and trajectories of children’s maladaptive behaviors: A 12-year prospective community study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40(3):468–478. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.563470. Retrieved from https://auth.lib.unc.edu/ezproxy_auth.php?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2011-09172-011&site=ehost-live&scope=site. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mares SHW, Lichtwarck–Aschoff A, Burk WJ, van dV, Engels RCME. Parental alcohol – specific rules and alcohol use from early adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53(7):798–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mares SHW, Van der Vorst H, Engels RCME, Lichtwarck-Aschoff A. Parental alcohol use, alcohol-related problems, and alcohol-specific attitudes, alcohol-specific communication, and adolescent excessive alcohol use and alcohol-related problems: An indirect path model. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(3):209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B. Latent variable analysis: Growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. In: Kaplan D, editor. Handbook of quantitative methodology for the social sciences. Sage Publications; 2004. pp. 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2014. [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham J, Morgan-Lopez A. College drinking behaviors: Mediational links between parenting styles, impulse control, and alcohol-related outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20(2):117–125. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson PL, Hawkins JD, Abbott RD, Catalano RF. Disentangling the effects of parental drinking, family management, and parental alcohol norms on current drinking by black and white adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence (Lawrence Erlbaum) 1994;4(2):203–227. Retrieved from https://auth.lib.unc.edu/ezproxy_auth.php?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=11301247&site=ehost-live&scope=site. [Google Scholar]

- Reimuller A, Hussong A, Ennett ST. The influence of alcohol-specific communication on adolescent alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences. Prevention Science. 2011;12(4):389–400. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0227-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan SM, Jorm AF, Lubman DI. Parenting factors associated with reduced adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;44(9):774–783. doi: 10.1080/00048674.2010.501759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer JL. Multiple imputation with PAN. In: Collins LM, Sayer AG, editors. New methods for the analysis of change. 1. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 355–378. [Google Scholar]

- Sieving RE, Maruyama G, Williams CL, Perry CL. Pathways to adolescent alcohol use: Potential mechanisms of parent influence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2000;10(4):489–514. doi: 10.1207/SJRA1004_06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thissen D, Chen WH, Bock RD. Multilog (version 7) Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Thissen D, Nelson L, Rosa K, McLead LD. Item response theory for items scored in two categories. In: Thissen D, Wainer H, editors. Test scoring. Mahwah, N.J: L. Erlbaum Associates; 2001. pp. 141–185. Retrieved from http://search.lib.unc.edu?R=UNCb3921279. [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, Enders CK. Identifying the correct number of classes in a growth mixture model. In: Hancock GR, Samuelson KM, editors. Advances in latent variable mixture models. Greenwich, CT: Information Age; 2007. pp. 317–341. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The surgeon general’s call to action to prevent and reduce underage drinking: A guide to action for families. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Eijnden R, Van den Mheen D, Vet R, Vermulst A. Alcohol-specific parenting and adolescents’ alcohol-related problems: The interacting role of alcohol availability at home and parental rules. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72(3):408–417. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.408. Retrieved from https://auth.lib.unc.edu/ezproxy_auth.php?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2011-10674-007&site=ehost-live&scope=site. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Zwaluw CS, Scholte RHJ, Vermulst AA, Buitelaar JK, Verkes RJ, Engels RCME. Parental problem drinking, parenting, and adolescent alcohol use. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;31(3):189–200. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9146-z1464-1476.10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Vorst H, Engels RCME, Dekovi M, Meeus W, Vermulst AA. Alcohol-specific rules, personality and adolescents’ alcohol use: A longitudinal person-environment study. Addiction. 2007;102(7):1064–1075. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Vorst H, Engels RCME, Meeus W, Dekovi M. Parental attachment, parental control, and early development of alcohol use: A longitudinal study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006a;20(2):107–116. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Vorst H, Engels RCME, Meeus W, Dekovi M. The impact of alcohol-specific rules, parental norms about early drinking and parental alcohol use on adolescents’ drinking behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006b;47(12):1299–1306. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01680.x. Retrieved from https://auth.lib.unc.edu/ezproxy_auth.php?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2006-22157-013&site=ehost-live&scope=site. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Vorst H, Engels RCME, Meeus W, Dekovi M, Van Leeuwe J. The role of alcohol-specific socialization in adolescents’ drinking behaviour. Addiction. 2005;100(10) doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Zundert Rinka MP, Van DV, Vermulst AA, Engels RCME. Pathways to alcohol use among dutch students in regular education and education for adolescents with behavioral problems: The role of parental alcohol use, general parenting practices, and alcohol-specific parenting practices. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20(3):456–467. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.3.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK. Latent class modeling with covariates: Two improved three-step approaches. Political Analysis. 2010;18:450–469. [Google Scholar]

- Wang CP, Brown CH, Bandeen-Roche K. Residual diagnostics for growth mixture models: Examining the impact of a preventive intervention on multiple trajectories of aggressive behaviors. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2005;100:1054–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Windle RC. Alcohol consumption and its consequences among adolescents and young adults. In: Galanter M, editor. New York, NY, US: Springer Science + Business Media; 2006. pp. 67–83. Retrieved from https://auth.lib.unc.edu/ezproxy_auth.php?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2005-15632-004&site=ehost-live&scope=site. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]