Abstract

Emerging evidence indicates that differentiation and mobilization of hematopoietic cell are critical in the development and establishment of hypertension (HTN) and HTN-linked vascular pathophysiology. This, coupled with the intimate involvement of the hyperactive renin-angiotensin system in HTN, led us to investigate the hypothesis that chronic angiotensin II (Ang II) infusion impacts hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) regulation at the level of the bone marrow (BM). Ang II infusion resulted in increases in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPC; 83%) and long-term HSC (LT-HSC; 207%) in the BM. Interestingly, increases of HSCs and LT-HSCs were more pronounced in the spleen (228% and 1117% respectively). Furthermore, we observed higher expression of C-C chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR2) in these HSCs, indicating there was increased myeloid differentiation in Ang II infused mice. This was associated with accumulation of CCR2+ proinflammatory monocytes in the spleen. In contrast, decreased engraftment efficiency of GFP+ HSC was observed following Ang II infusion. Time-lapse in vivo imaging and in vitro Ang II pretreatment demonstrated that Ang II induces untimely proliferation and differentiation of the donor HSC resulting in diminished HSC engraftment and BM reconstitution. We conclude that 1) Chronic Ang II infusion regulates HSC proliferation, mediated by angiotensin receptor type 1a, 2) Ang II accelerates HSC to myeloid differentiation resulting in accumulation of CCR2+ HSCs and inflammatory monocytes in the spleen, and 3) Ang II impairs homing and reconstitution potentials of the donor HSCs. These observations highlights the important regulatory roles of Ang II on HSC proliferation, differentiation and engraftment.

Keywords: Hypertension, Hematopoietic stem cell, Angiotensin II, Bone marrow transplantation, in vivo imaging, Engraftment, Inflammation

Introduction

Recent evidence indicates that the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) plays critical roles in the development of the hematopoietic system1–4 and hematopoiesis.5–7 Components of the RAS, including angiotensinogen, angiotensin II (Ang II), angiotensin 1–7 [Ang-(1–7)], angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), ACE2, angiotensin receptor type 1a (AT1R), AT2R are all present in bone marrow (BM) cells.8, 9 Several studies have shown that ACE inhibitors and AT1R/AT2R antagonists induces abnormal hematopoiesis suggesting that RAS regulates hematopoiesis through angiotensin receptors.5, 10 In addition, Ang II and Ang-(1–7) have been demonstrated to influence proliferation of hematopoietic progenitors and facilitate early recovery from mild myelosuppression.11, 12 Consistent with these are our previous studies demonstrating increases in BM proinflammatory cells and a decrease in endothelial progenitor cells in chronic Ang II induced hypertension.13 These observations led us to propose that Ang II would exert a profound influence in hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) at the BM level. Understanding how Ang II regulates HSC would be critical as various BM originated hematopoietic cells have been shown to contribute to initiation and progress of hypertension (HTN)14–17 and HTN associated diseases such as cardiac infarction and arthrosclerosis.18, 19

More than 1 million HSC transplantation (HSCT) were performed around the world to correct a variety of bone marrow deficiencies.20 During or after HSCT, immunosuppressive drugs such as cyclosporine A are widely used to minimize the risk of graft rejection and to increase the engraftment efficacy.21 However, their clinical use is frequently associated with 2–5 folds increased Ang II level in the serum and kidney, resulting in systemic and renal vasoconstriction that leads to HTN.22–24 Considering this side effect of immune suppressors and prevalence of HTN in public, it is critical to understand the role of RAS, especially the potent effector Ang II on HSC homing and engraftment to enhance HSCT efficiency. Engraftment of the donor derived HSC in lethally irradiated recipients involves dynamic and multistep processes.25 The donor HSCs recruited to the BM go through trans-marrow migration and lodge in the HSC niche (HSC homing). Once the HSC arrives to the niche, its expansion is orchestrated by a complex interplay of niche cells, cytokines, and adhesion molecules in the microenvironment.26, 27 Therefore, arrival of HSCs to the HSC niche is critical for efficient reconstitution of hematopoiesis. Our second goal in this study was to know if Ang II plays any important role in HSC homing and engraftment. Taken together, it is of extreme importance to understand how Ang II impacts HSC regulation to enhance treatment of HTN and HSCT. Thus, our objectives in the present study were: (1) to determine the effects of Ang II on proliferation and differentiation of the most primitive HSC in vivo and (2) to investigate whether Ang II affects HSC engraftment efficiency.

Methods

Mice and Ang II infusion

Male C57BL6 mice (2–3 month old) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. UBC-GFP and CX3CR1GFP/GFP mice were originally purchased from Jackson Laboratory and maintained at the University of Florida. The latter mice were bred with C57BL6/J mice to generate CX3CR1+/GFP animals. Osmotic mini-pumps (1004, ALZAT Corporation) were loaded either with Ang II (Bachem) dissolved in 0.9% saline (w/v) or with saline alone. Ang II was delivered at a dose of 1000ng·kg 1·min 1. Pumps were designed to administer Ang II or saline for at least 28 days, which were implanted subcutaneously into the dorsum. In some experiments, osmotic pumps were replaced at the third week for constant saline/Ang II infusion. Losartan (Sigma-Aldrich) was administered daily by intraperitoneal injection (20mg·kg 1·day 1) All experimental procedures performed on animals were in accordance with the University of Florida’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Video and statistical analysis

All videos were first captured using Volocity 5.5 and further processed and edited with Apple iMovie and Sony Vegas Pro 9.0. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test using Prism 5 (Graphad). P values were designated as follows: *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001. All values in the data are mean±SEM.

All experimental protocols and methods are available in the online-only Data Supplement.

Results

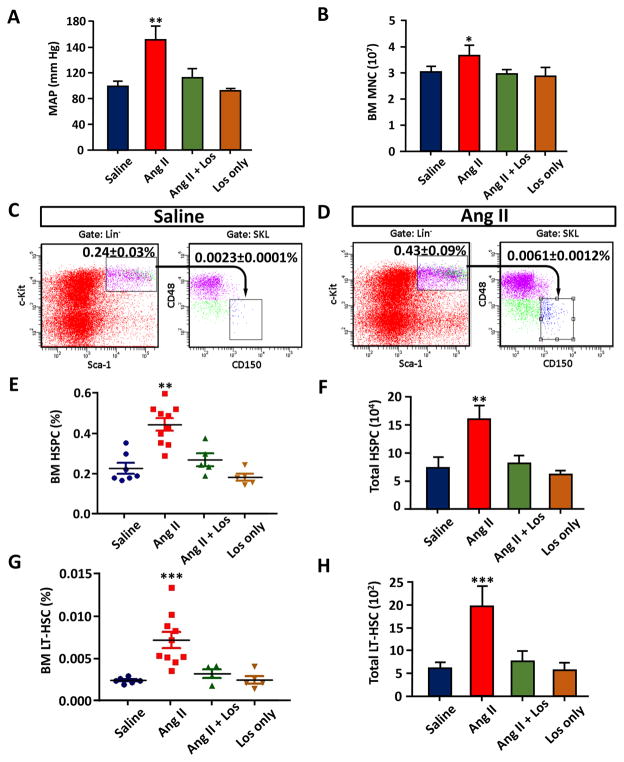

Ang II increases HSC in both the bone marrow and spleen

Infusion of Ang II (1000ng·kg 1·min 1) for 3 weeks in C57BL6 mice resulted in 53 mm Hg increase in MAP (102±8 mmHg control vs. 155±16 mmHg Ang II, Figure 1A). This effect was blunted by co-administration with losartan (20mg·kg 1·day 1), an AT1R antagonist (Figure 1A). The number of BM mononuclear cells (MNC) in Ang II infused mice was increased by 16% (Figure 1B). In the BM of normotensive mice, Sca-1+, c-Kit+, Lin− (SKL) cells that are highly enriched for hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPC) represented approximately 0.24% of the BM MNC (Figure 1C). The HSPC population was increased by 83% in Ang II treated mice (Figure 1D, E and F). Co-administration with Ang II and losartan significantly attenuated the increase of SKL cells (Figure 1A, E and F). We further purified the long-term HSC (LT-HSC) from SKL cells by CD150+ and CD48− selection. LT-HSC is a rare population of HSC in the BM (~0.002% of total BM cells, Figure 1C and D) that has been shown to be normally quiescent but possesses life-long hematopoietic repopulation potentials.28, 29 We observed 207% increase of LT-HSC in the BM, which was also attenuated by co-treatment with losartan (Figure 1G, H). These data indicate that chronic Ang II infusion resulted in an increase in HSC proliferation.

Figure 1.

Effect of chronic Ang II infusion on BM HSPC and LT-HSC. A, Mean arterial pressure (MAP) measured by tail cuff after 3 weeks of Ang II infusion. B, The numbers of average bone marrow mononuclear cells (BM MNC) per one hind leg (1 femur and 1 tibia). C and D, Flow cytometric gating strategy for BM SKL (HSPC) and CD 150+, CD48− SKL cells (LT-HSC) in saline infused and Ang II infused mice. E, Percentile of HSPC in the BM. F, The average of absolute numbers of total HSPC from one hind leg. G, Percentile of LT-HSC in the BM. H, The average of absolute numbers of total LT-HSC from one hind leg. n=5–10 for each cohort. P values were designated as follows: *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001.

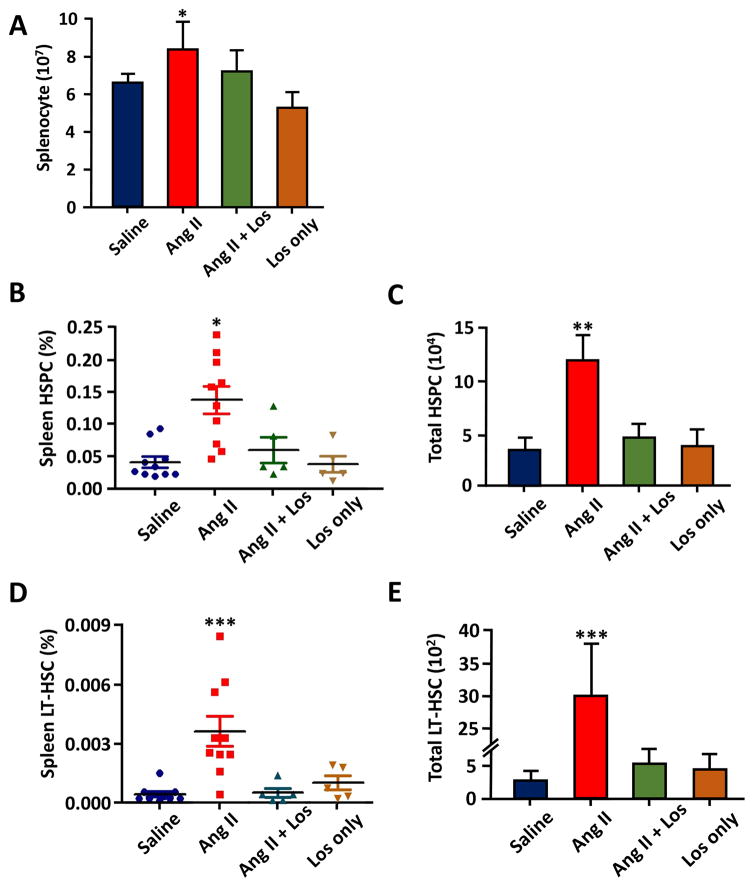

Next, we examined the levels of HSCs in the spleen. Interestingly, Ang II treatment resulted in 22% increase in total splenocytes (Figure 2A), 228% increase in HSC (Figure 2B, C) and 1117% increase in LT-HSC in the spleen of Ang II mice (Figure 2D, E). These increases were attenuated by co-treatment with losartan. This demonstrates a significant increase of extramedullary hematopoietic activity in the spleen of Ang II-treated animals.

Figure 2.

Effect of chronic Ang II infusion on spleen HSPC and LT-HSC. A, The average numbers of splenocytes from each spleen. B, Percentile of HSC in the spleen. C, Absolute numbers of total HSC from each spleen. D, Percentile of LT-HSC in the spleen. E, The average of absolute number of total LT-HSC from each spleen. n=5–10 for each cohort. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001.

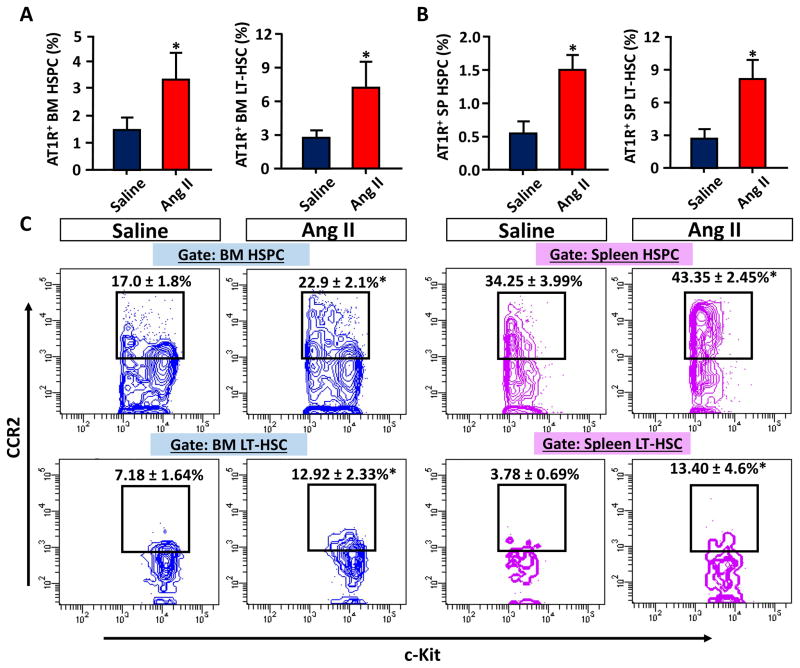

Ang II regulates HSC differentiation

We investigated if the expression levels of AT1R changed in HSPC and LT-HSC in Ang II treated animals. We observed significant increases of AT1R expressions on HSCs of both BM and spleen (Figure 3A and B). Next, we measured the CCR2 levels to determine if Ang II caused differentiation of HSCs into further differentiated progenitors. A recent study showed that the CCR2 level in HSC is a critical marker for the initiation of HSC to myeloid differentiation and that CCR2+ HSCs are the intermediate HSC (IM-HSC) with no long term reconstitution potentials.30 FACS analysis showed that CCR2+ HSC populations are markedly increased in both BM and spleen of Ang II infused animals, showing Ang II acts as an important initiator of HSC differentiation (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Increased AT1R and CCR2 expressions in HSCP and LT-HSC of Ang II infused mice. A, AT1R expressing cells were analyzed in BM SKL cells (left) and BM CD150+, CD48− SKL cells (right). B, The same AT1R expressing cells were analyzed in spleen (SP). C, FACS contour plots showing CCR2+ cells (y axis) in HSPC and LT-HSC of saline or Ang II infused mice. *, P ≤ 0.05.

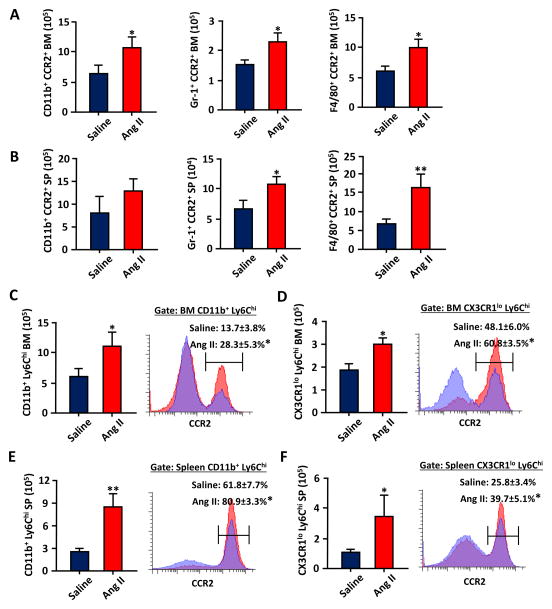

As the CCR2+ HSC is thought to be the most upstream contributor of myelopoiesis,30 we next investigated if the increase of CCR2+ HSCs in Ang II mice was also associated with increased myeloid cells that expressed CCR2. We observed overall increases of CCR2+ expressing myeloid (CD11b+/Gr-1+/F4/80+) cells (49–80% in the BM and 58–142% in the spleen; Figure 4 A and B). When more defined Ly6Chi monocytes (CD11b+, Ly6Chi) and inflammatory monocytes (CX3CR1lo, Ly6Chi) were analyzed and further gated for CCR2, we found that the number of monocytes and their CCR2 expressions were consistently increased in Ang II infused mice. This suggests that Ang II impacted downstream myeloid differentiation following HSC proliferation and that CCR2 expression was the key signal for BM to spleen mobilization.31, 32

Figure 4.

Chronic Ang II infusion results in increased HSC differentiation toward CCR2+ myeloid/monocytic cells in the BM and spleen. A, The average absolute numbers of CCR2+ and CD11b+/Gr-1+/F4/80+ cells from each hind leg after 3 week saline/Ang II infusion (n=5–10). B, The average absolute numbers of CCR2+ and CD11b+/Gr-1+/F4/80+ cells from each spleen (SP). C, The average absolute numbers of CD11b+, Ly6Chi cells were further gated for CCR2 expression from the BM cells of saline or Ang II infused mice. D, The average absolute numbers of CX3CR1lo, Ly6Chi cells were further gated for CCR2 expression from the BM cells. E and F, The same CCR2+,CD11b+, Ly6Chi cells and CCR2+,CX3CR1lo, Ly6Chi cells were analyzed from splenocytes. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01.

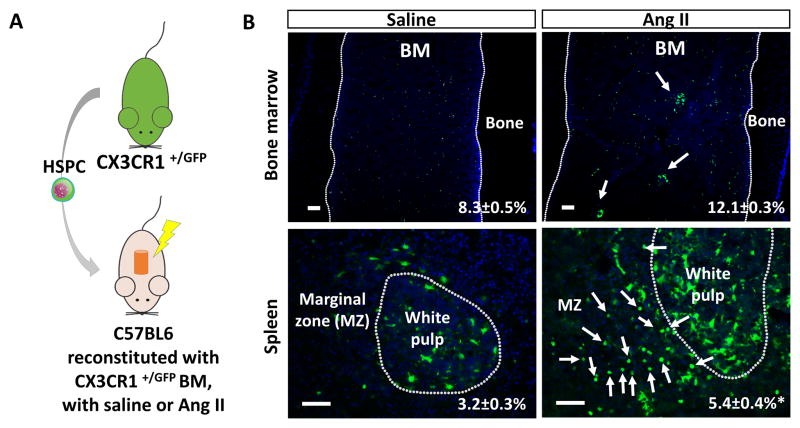

C57BL6 mice were reconstituted with HSPC from the BM of CX3CR1 +/GFP mice to determine the origin of increased myeloid cells in the BM and spleen (Figure 5A). We observed an increase of CX3CR1+/GFP in Ang II infused BM (Figure 5B). In addition, CX3CR1+/GFP myeloid colonies were observed only in the Ang II infused BM (arrows in the BM). Furthermore, there was significant accumulation of CX3CR1+/GFP cells in the spleen with marked increase of round cells with typical monocyte morphology primarily located in the marginal zone of the spleen (arrows in the spleen). The result suggests that accumulation of myeloid/monocyte cells in the BM and spleen originated from the BM HSCs.

Figure 5.

The increased myeloid cells are originated from the BM HSC. A, A diagram showing HSPC transplantation from CX3CR1+/GFP mice (n=5). B, Histology of the femur (top) and spleen (bottom) showing increased CX3CR1-GFP+ cells (arrows) after 3 weeks of Ang II infusion (all bars=100μm). *, P ≤ 0.05.

Aberrant engraftment of HSC in Ang II treated mice

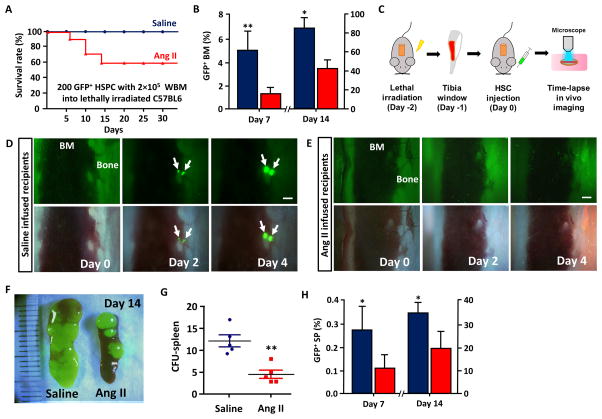

We next determined if effects of Ang II on proliferation, differentiation and mobilization of HSC adversely affected engraftment of HSC into the BM in the HSCT setting. Homing and engraftment of HSC into the BM were compared between the saline/Ang II infused groups that are lethally irradiated by two different methods. At first, we injected the minimal survival number of HSPC from UBC-GFP mice (200 GFP+ SKL cells, determined from a separate pilot study) with 2×105 whole BM (WBM) cells into saline or Ang II (1000ng·kg 1·min 1) infused and lethally irradiated mice. Survival rates of the chimeric mice were monitored over 30 days for engraftment success. Only 58% of the Ang II infused HTN mice survived while all saline infused control mice were rescued (Figure 6A). This was associated with a noticeable reduction in engraftment of the donor HSC derived GFP+ cells (24–50% compared to control), which was more prominent at the early engraftment stage of HSC (Day 7) than the later (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Inefficient and abnormal engraftment of HSC in Ang II treated mice. A, The survival rate of saline or Ang II infused, lethally irradiated mice rescued with 200 GFP+ SKL cells and 2×105 whole bone marrow cells (n=12). B, BM reconstitution from 5×103 GFP+ SKL cells in saline or Ang II infused recipients at day 7 and 14 after transplantation. C, A diagram showing the process of in vivo tibia imaging. D and E, Time-lapse in vivo imaging of HSC engraftment (arrows) in saline or Ang II infused recipients, F, Direct visualization of spleen engraftment. (Unit=mm) G, CFU-s count in saline and Ang II infused recipients. H, GFP+ cells in the spleen of saline or Ang II infused recipients at day 7 and 14 after transplantation. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01.

Secondly, we used a time-lapse imaging technique of the mouse tibial bone to directly track the HSC engraftment over time in saline and Ang II infused mice.33 In saline infused control group, individual HSCs that developed into colonies at the later time points were found mainly near the endosteum (Video S1), where osteoblasts and other microenvironmental cells are enriched to support HSC.25, 34, 35 These GFP+ SKL cells started to engraft and actively expand in the osteoblastic HSC niche within 48h of injection, which is a critical hallmark of functional HSC (Figure 6D)26. In contrast, GFP+ SKL cells in Ang II treated animals did not localize to the HSC niche and rarely formed proliferative colonies suggesting that most HSCs were further differentiated and lost the engraftment potential (Figure 6E and Video S1). As extramedullary hematopoiesis in the spleen commonly occurs in lethally irradiated mice to facilitate hematopoietic recovery,6 we examined the spleen of these two groups to find out that there was a statistically significant reduction in the number of colony forming unit-spleen (CFU-s) in Ang II infused mice (Figure 6F, G). Furthermore, there was a marked decreases of the GFP+ cells in the spleens of these mice demonstrating that overall engraftment of Ang II infused mice was inefficient compared to saline treated controls (Figure 6H).

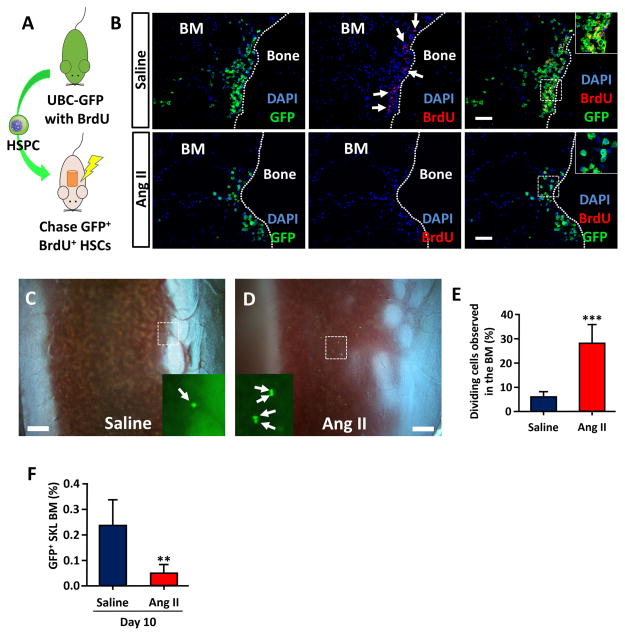

Proliferation and differentiation of HSC result in decreased engraftment in Ang II infused mice

To further investigate how HSCs engraft differently in these two groups, we first used a BrdU label retaining assay to track slow cycling HSCs that maintained stemness in saline or Ang II infused mice (Figure 7A).36 While many BrdU retaining HSCs were observed near the osteoblastic HSC niche of the saline treated animals, few BrdU retaining cells were observed at the same area in Ang II infused animals (Figure 7B). In vivo imaging of donor HSCs 18h after cell injection also indicated that there was very early cell division of HSC in Ang II treated mice (Figure 7C, D and Video S2). While most of the transplanted HSCs in saline infused mice remained as single cells at 18h after injection, about 1 out of 4 cells in Ang II infused mice were observed as dividing cells (Figure 5E). Donor derived SKL cells analyzed 10 days after injection indicated that there was a significant decrease of remaining HSCs in Ang II infused animals (Figure 7F). Taken together, the results suggest that Ang II has adverse effects on HSC homing and engraftment due to untimely proliferation and early differentiation before reaching to the HSC niche.

Figure 7.

Untimely proliferation and differentiation of HSC result in poor engraftment in Ang II infused mice. A, A diagram showing the BrdU retention assay. HSPCs from BrdU fed UBC-GFP mice were transplanted into C57BL6 recipients. B, Immunohistochemistry of femur from saline and Ang II infused mice. BrdU retaining GFP+ cells (slow cycling HSC) were mostly observed near the endosteum of saline infused mice (arrows, bar=100μm). C and D, In vivo imaging of homing GFP+ HSC (arrows) 18h after HSC injection. E, Percentile of dividing cells observed in the tibia BM (bar=200μm). F, GFP+ SKL cells in whole BM at day 10. **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001.

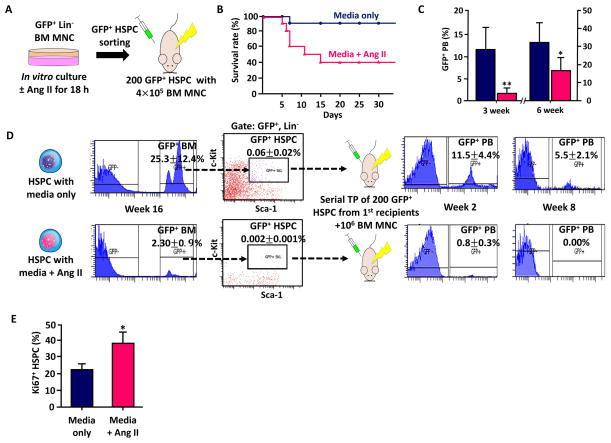

Ang II directly affects long-term reconstitution potential of HSC

To exclude the possibility that hemodynamic changes or any other indirect in vivo effects from systemic Ang II infusion influenced the engraftment efficiency, we incubated GFP+ Lin− BM cells with or without Ang II for 18h in vitro, sorted and injected SKL cells (GFP+ HSPC) into lethally irradiated animals (Figure 8A). The recipients were all normotensive and the GFP+ HSPC were exposed to Ang II only in vitro before injection. The early survival rate of recipients that received Ang II exposed HSPC was much lower than the control (40% vs. 90%, Figure 8B). The rate of hematopoiesis from Ang II exposed HSPC was also significantly lower, confirming the direct effect of Ang II on HSC engraftment (Figure 8C). In addition, we observed poor BM reconstitution and a significant decrease of SKL cells in mice that received Ang II exposed HSPC (Figure 8D). We performed serial transplantation of SKL cells from the first recipients to further test whether Ang II truly affected the long-term reconstitution potential of the HSC.29 While the control HSPC still maintained the strong reconstitution potential in the secondary recipients, the Ang II exposed HSPC failed to restore hematopoiesis and GFP+ peripheral blood disappeared completely within 8 weeks in the secondary recipients (Figure 8D). Ki67 staining showed that more HSPCs were in active phases of the cell cycle when exposed to Ang II in vitro, confirming the previous result of untimely proliferation observed in Ang II infused animals. The results indicate that Ang II directly and negatively affects long-term reconstitution potential of HSC.

Figure 8.

Serial transplantation assay to confirm the direct effect of Ang II on long-term reconstitution potential of HSC. A, A diagram showing the experimental approach. Lineage marker negative BM mononuclear cells from UBC-GFP mice (GFP+ Lin− BM MNC) were incubated in vitro with media or media+Ang II for 18h, sorted for HSPC and injected into lethally irradiated recipients with 106 BM MNC from C56BL6 mice. B, The survival rate of the primary recipients that had either HSPC incubated with STEMSPAN media or HSPC incubated with media and Ang II (250 μg/ml) for 18h (n=10) C, GFP+ peripheral blood (PB) reconstitution of each group on week 3 and 6. D, Serial transplantation assay using HSPC exposed to Ang II prior to injection. Ang II exposed HSPC showed significantly lower BM engraftment and did not reconstitute peripheral blood in the second transplantation. E, Ki67+ HSPCs that are in active phases of the cell cycle after 18h in vitro culture with or without Ang II. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01.

Discussion

The most significant finding of this study is that Ang II has profound influence on the compositions of HSC and myeloid progenitors. Ang II directly induced HSPC/LT-HSC proliferation and CCR2+ monocytes accumulation in the BM and spleen, while impairing homing and engraftment of HSC in the HSCT setting. We propose that these actions contribute to hypertensive effects of Ang II and suggest that controlling the RAS activity should be considered prior to HSC transplantation (HSCT) to enhance engraftment efficacy of HSC. We observed that Ang II markedly increased numbers of both HSPC and quiescent LT-HSC, an effect attenuated by losartan, suggesting that upregulated AT1R transactivated various tyrosine and nontyrosine kinase receptors to carry out its pleiotropic effects for cell proliferation.37 Our finding that Ang II has direct action on the BM HSC is supported by other reports showing the presence of AT1R in various BM cells and HSC7, 8, 38, 10. In addition, AT1R mediated signaling is known to play critical roles for myeloid differentiation,39, 40 highlighting the importance of Ang II in HSC regulation. Although direct Ang II actions are clearly evident from our data, its indirect effects on other regulatory microenvironmental cells in the BM such as osteoblasts41, 42 and mesenchymal stem cells43, 44 or extracellular matrix such as collagen, which is an important structural component of the HSC niche, 45, 46 cannot be ruled out at the present time.

Most of the HSCs reside within the BM, while very few are found in the spleen and circulation. These peripheral HSCs can contribute to extramedullary hematopoiesis in pathological conditions such as infection, cardiovascular diseases or irradiation.19, 32, 47–49 Although HSCs in the spleen resemble BM HSCs because they are capable of multilineage reconstitution,47 LT-HSCs that have life-long hematopoiesis potentials are thought to exist in the BM, based on observations that only the BM has all microenvironmental cells that constitute the HSC niche for LT-HSC maintenance. 27, 50 Interestingly, LT-HSCs that were extremely rare in the spleen of control mice were readily detectable in Ang II infused mice, with an 8.6 fold increase in percentile and 11 fold increase in absolute number (Figure 2). We also observed accumulation of cells with myeloid lineage and inflammatory monocytes along with the increase of CCR2+ HSC. CCR2 is an important signal for recruiting hematopoietic cells to the inflammatory sites31 and it could have played similar roles for mobilization of HSC to the spleen (Figure 3–5).32 In addition, we speculate that the oxidative stress from Ang II infusion could have induced CCR2 overexpression and myeloid biased differentiation.51, 52

Our study is unique in a way that it uses continuous time-lapse in vivo imaging at a single cell resolution, allowing direct observation of functional bona fide HSC with engraftment and proliferation potentials (Figure 6). Using this technology, we have shown that Ang II infusion significantly inhibited homing and engraftment of HSC into the BM HSC niche. In vivo imaging showed that many donor derived HSC went through early proliferation possibly from the proliferative effect of Ang II through AT1R mediated MAP kinases and/or the JAK/STAT activation37. This untimely event resulted in a decrease of available HSC for engraftment in the BM osteoblastic HSC niche (Figure 7). As the microenvironmental signals that HSC receive from the niche are critical for efficient engraftment and proliferation,27 this led to abnormal and inefficient engraftment of HSC in Ang II treated recipients. As in vitro exposure of Ang II to HSCs also negatively impacted engraftment in normotensive recipients, the results highlight the direct and adverse role of Ang II for HSC engraftment potentials (Figure 8).

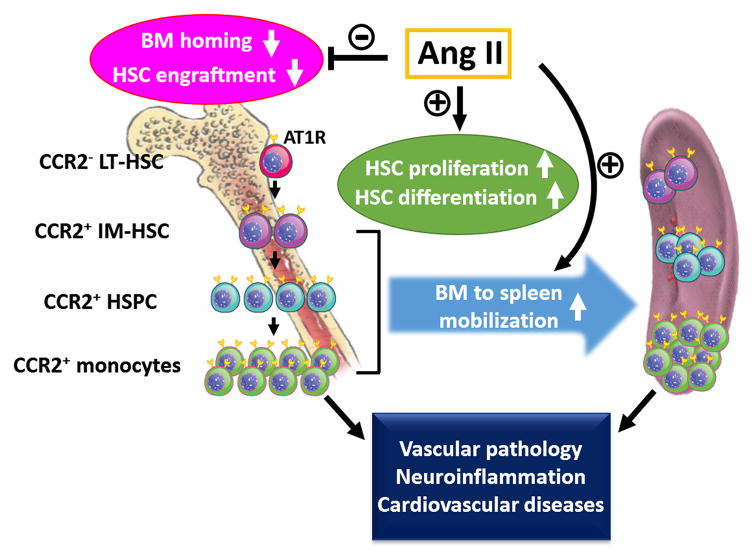

We have summarized our conclusion in Figure 9, describing the important dual roles of Ang II in HSC regulation. While chronic Ang II infusion increased the numbers of HSCs leading to myeloid biased differentiation in the BM and mobilization of CCR2+ HSCs/monocytes to the spleen, it also decreased engraftment efficiency of HSC in the lethally irradiated recipients because of early differentiation and undue proliferation prior to homing. It would be interesting to investigate the roles of increased myeloid progenitors and monocyte in the progress of Ang II induced HTN. There is a growing body of evidence that immune changes and increased inflammatory monocytes are the key to development of HTN and cardiovascular diseases through vascular inflammation.15, 53 In addition, our previous evidence has shown that neuroinflammation plays important roles in the development and establishment of neurogenic hypertension.13, 54 Based on our present data, it is tempting to speculate that increases of HSC and myeloid progenitors in the BM and spleen would be critical to mobilization of these proinflammatory cells into the brain.14, 55, 56

Figure 9.

A diagram summarizing multiple effects of Ang II on HSC regulation. Ang II initiated proliferation/differentiation of BM LT-HSC leading to the increases and accumulation of CCR2+ intermediate HSC (IM-HSC), HSPC and monocytes to the spleen. The increased CCR2+ proinflammatory cells are proposed to facilitate the progresses of vascular inflammation, neuroinflammation and HTN associated cardiovascular diseases in the discussion. Ang II also triggered premature proliferation of HSC that had adverse effects on BM homing, resulting in decreased engraftment efficiency.

Perspectives

Our study shows that Ang II has profound influence on BM and spleen HSCs, impacting their proliferation, differentiation and engraftment efficiency. Considering that the level of circulating Ang II can change drastically in HTN patients,57 these changes may similarly impact human BM and spleen, contributing to the progress of HTN16, 17 and HTN associated cardiovascular diseases18, 19, 30 Although we used the pressor dose to investigate immune changes in the animal model, the effects of Ang II on hematopoietic cells may vary depending on the dose and exposure time. Further study would be required to understand AT1R/AT2R mediated signalings that lead to immune changes in HTN. The negative effects of Ang II on HSC engraftment and homing have significant clinical implications in HSCT, as Ang II induced HTN is one of the major side effects of immunosuppressive drugs used after allogeneic HSCT.23 Angiotensin-receptor blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors are commonly prescribed to treat HTN in HSCT patients58 and our results show that anti-hypertensive drugs should be carefully chosen for these patients.59 There is no clinical data that has clearly addressed the impact of HTN on HSCT success and patients survival. Thus, it would be relevant to undertake a retrospective study to determine the influence of high BP in HSCT.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What Is New?

This study provides a direct evidence that Ang II regulates hematopoiesis in vivo at the stem cell level. Ang II infusion resulted in increased number of CCR2 expressing HSC and myeloid cells in the BM and these changes were even more significant in the spleen, suggesting that the spleen can act as an important reservoir for both CCR2+ HSC and inflammatory monocytes.

Reconstitution assays and in vivo imaging of the tibia bone in lethally irradiated mice showed that Ang II negatively affects the HSC homing to its stem cell niche.

What Is Relevant?

Ang II induced increases of CCR2+ HSC and myeloid progenitors in the BM and spleen could contribute development of hypertension and cardiovascular diseases.

As Ang II exposure triggers untimely proliferation and differentiation of HSC resulting in poor engraftment, anti-hypertensive drugs that regulate RAS should be carefully chosen for HSCT patients.

Summary.

Our study have shown that that Ang II is very closely associated with altered hematopoiesis and increased inflammation responses, which required activation of different levels of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. We showed that Ang II regulates primitive HSC populations by increasing proliferation, myeloid biased differentiation and mobilization to the spleen through CCR2 expression. We used reconstitution assays and a novel time-lapse in vivo imaging of the tibia to demonstrate that Ang II impairs homing efficacy of HSC to the BM stem cell niche, resulting in poor hematopoietic reconstitution and survival in lethally irradiated mice. The findings demonstrate the important roles of Ang II in HSC regulation and may have clinical relevance in HTN treatment and HSC transplantation.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the helps from Neal Benson and Dr. Vermali Rodriguez for data analysis.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by NIH grants HL33610 and HL56921.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Zambidis ET, Park TS, Yu W, Tam A, Levine M, Yuan X, Pryzhkova M, Peault B. Expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme (cd143) identifies and regulates primitive hemangioblasts derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Blood. 2008;112:3601–3614. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-144766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savary K, Michaud A, Favier J, Larger E, Corvol P, Gasc JM. Role of the renin-angiotensin system in primitive erythropoiesis in the chick embryo. Blood. 2005;105:103–110. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinka L, Biasch K, Khazaal I, Peault B, Tavian M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (cd143) specifies emerging lympho-hematopoietic progenitors in the human embryo. Blood. 2012;119:3712–3723. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-314781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jokubaitis VJ, Sinka L, Driessen R, Whitty G, Haylock DN, Bertoncello I, Smith I, Peault B, Tavian M, Simmons PJ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (cd143) marks hematopoietic stem cells in human embryonic, fetal, and adult hematopoietic tissues. Blood. 2008;111:4055–4063. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-091710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park TS, Zambidis ET. A role for the renin-angiotensin system in hematopoiesis. Haematologica. 2009;94:745–747. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.006965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hubert C, Savary K, Gasc JM, Corvol P. The hematopoietic system: A new niche for the renin-angiotensin system. Nature clinical practice. Cardiovascular Medicine. 2006;3:80–85. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodgers KE, Dizerega GS. Contribution of the local ras to hematopoietic function: A novel therapeutic target. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2013;4:157. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haznedaroglu IC, Ozturk MA. Towards the understanding of the local hematopoietic bone marrow renin-angiotensin system. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2003;35:867–880. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strawn WB, Richmond RS, Ann Tallant E, Gallagher PE, Ferrario CM. Renin-angiotensin system expression in rat bone marrow haematopoietic and stromal cells. British Journal of Haematology. 2004;126:120–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chisi JE, Wdzieczak-Bakala J, Thierry J, Briscoe CV, Riches AC. Captopril inhibits the proliferation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in murine long-term bone marrow cultures. Stem Cells. 1999;17:339–344. doi: 10.1002/stem.170339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodgers K, Xiong S, DiZerega GS. Effect of angiotensin ii and angiotensin(1–7) on hematopoietic recovery after intravenous chemotherapy. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2003;51:97–106. doi: 10.1007/s00280-002-0509-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodgers KE, Xiong S, diZerega GS. Accelerated recovery from irradiation injury by angiotensin peptides. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2002;49:403–411. doi: 10.1007/s00280-002-0434-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jun JY, Zubcevic J, Qi Y, Afzal A, Carvajal JM, Thinschmidt JS, Grant MB, Mocco J, Raizada MK. Brain-mediated dysregulation of the bone marrow activity in angiotensin ii-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2012;60:1316–1323. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.199547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santisteban MM, Ahmari N, Carvajal JM, Zingler MB, Qi Y, Kim S, Joseph J, Garcia-Pereira F, Johnson RD, Shenoy V, Raizada MK, Zubcevic J. Involvement of bone marrow cells and neuroinflammation in hypertension. Circulation Research. 2015;117:178–191. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrison DG, Guzik TJ, Lob HE, Madhur MS, Marvar PJ, Thabet SR, Vinh A, Weyand CM. Inflammation, immunity, and hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;57:132–140. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trott DW, Harrison DG. The immune system in hypertension. Advances in Physiology Education. 2014;38:20–24. doi: 10.1152/advan.00063.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wenzel P, Knorr M, Kossmann S, Stratmann J, Hausding M, Schuhmacher S, Karbach SH, Schwenk M, Yogev N, Schulz E, Oelze M, Grabbe S, Jonuleit H, Becker C, Daiber A, Waisman A, Munzel T. Lysozyme m-positive monocytes mediate angiotensin ii-induced arterial hypertension and vascular dysfunction. Circulation. 2011;124:1370–1381. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.034470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nahrendorf M, Pittet MJ, Swirski FK. Monocytes: Protagonists of infarct inflammation and repair after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2010;121:2437–2445. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.916346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M. Leukocyte behavior in atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and heart failure. Science. 2013;339:161–166. doi: 10.1126/science.1230719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pasquini MC, Aljurf MD, Confer DL, Baldomero H, Bouzas LF, Horowitz MM, Iida M, Kodera Y, Lipton JH, Oudshoorn M, Gluckman E, Passweg JR, Szer J, Novitzky N, van Rood JJ, Noel L, Madrigal JA, Frauendorfer K, Gratwohl A, Appelbaum FR. Global hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (hsct) at one million: An achievement of pioneers and foreseeable challenges for the next decade. A report from the worldwide network for blood and marrow transplantation (wbmt) Blood. 2013;122:2133–2133. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chinen J, Buckley RH. Transplantation immunology: Solid organ and bone marrow. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2010;125:S324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lassila M. Interaction of cyclosporine a and the renin-angiotensin system; new perspectives. Current Drug Metabolism. 2002;3:61–71. doi: 10.2174/1389200023337964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishiyama A, Kobori H, Fukui T, Zhang GX, Yao L, Rahman M, Hitomi H, Kiyomoto H, Shokoji T, Kimura S, Kohno M, Abe Y. Role of angiotensin ii and reactive oxygen species in cyclosporine a-dependent hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;42:754–760. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000085195.38870.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis JJ. Hypertensinogenic mechanism of the calcineurin inhibitors. Current Hypertension Reports. 2002;4:377–380. doi: 10.1007/s11906-002-0067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nilsson SK, Simmons PJ, Bertoncello I. Hemopoietic stem cell engraftment. Experimental Hematology. 2006;34:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lapidot T, Dar A, Kollet O. How do stem cells find their way home? Blood. 2005;106:1901–1910. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Purton LE, Scadden DT. StemBook [Internet] Cambridge (MA): Harvard Stem Cell Institute; 2008. The hematopoietic stem cell niche. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arai F, Suda T. Stembook. Cambridge (MA): 2008. Quiescent stem cells in the niche. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Purton LE, Scadden DT. Limiting factors in murine hematopoietic stem cell assays. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dutta P, Sager HB, Stengel KR, Naxerova K, Courties G, Saez B, Silberstein L, Heidt T, Sebas M, Sun Y, Wojtkiewicz G, Feruglio PF, King K, Baker JN, van der Laan AM, Borodovsky A, Fitzgerald K, Hulsmans M, Hoyer F, Iwamoto Y, Vinegoni C, Brown D, Di Carli M, Libby P, Hiebert SW, Scadden DT, Swirski FK, Weissleder R, Nahrendorf M. Myocardial infarction activates ccr2(+) hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:477–487. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsou CL, Peters W, Si Y, Slaymaker S, Aslanian AM, Weisberg SP, Mack M, Charo IF. Critical roles for ccr2 and mcp-3 in monocyte mobilization from bone marrow and recruitment to inflammatory sites. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117:902–909. doi: 10.1172/JCI29919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M, Etzrodt M, Wildgruber M, Cortez-Retamozo V, Panizzi P, Figueiredo JL, Kohler RH, Chudnovskiy A, Waterman P, Aikawa E, Mempel TR, Libby P, Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. Identification of splenic reservoir monocytes and their deployment to inflammatory sites. Science. 2009;325:612–616. doi: 10.1126/science.1175202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bengtsson NE, Kim S, Lin L, Walter GA, Scott EW. Ultra-high-field mri real-time imaging of hsc engraftment of the bone marrow niche. Leukemia. 2011;25:1223–1231. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin T, Li L. The stem cell niches in bone. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2006;116:1195–1201. doi: 10.1172/JCI28568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kunisaki Y, Bruns I, Scheiermann C, Ahmed J, Pinho S, Zhang D, Mizoguchi T, Wei Q, Lucas D, Ito K, Mar JC, Bergman A, Frenette PS. Arteriolar niches maintain haematopoietic stem cell quiescence. Nature. 2013;502:637–643. doi: 10.1038/nature12612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson A, Laurenti E, Oser G, van der Wath RC, Blanco-Bose W, Jaworski M, Offner S, Dunant CF, Eshkind L, Bockamp E, Lio P, Macdonald HR, Trumpp A. Hematopoietic stem cells reversibly switch from dormancy to self-renewal during homeostasis and repair. Cell. 2008;135:1118–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehta PK, Griendling KK. Angiotensin ii cell signaling: Physiological and pathological effects in the cardiovascular system. American journal of physiology. Cell Physiology. 2007;292:C82–97. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00287.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodgers KE, Xiong S, Steer R, diZerega GS. Effect of angiotensin ii on hematopoietic progenitor cell proliferation. Stem Cells. 2000;18:287–294. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.18-4-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin C, Datta V, Okwan-Duodu D, Chen X, Fuchs S, Alsabeh R, Billet S, Bernstein KE, Shen XZ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme is required for normal myelopoiesis. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2011;25:1145–1155. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-169433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsubakimoto Y, Yamada H, Yokoi H, Kishida S, Takata H, Kawahito H, Matsui A, Urao N, Nozawa Y, Hirai H, Imanishi J, Ashihara E, Maekawa T, Takahashi T, Okigaki M, Matsubara H. Bone marrow angiotensin at1 receptor regulates differentiation of monocyte lineage progenitors from hematopoietic stem cells. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2009;29:1529–1536. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.187732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, Weber JM, Olson DP, Knight MC, Martin RP, Schipani E, Divieti P, Bringhurst FR, Milner LA, Kronenberg HM, Scadden DT. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425:841–846. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Querques F, Cantilena B, Cozzolino C, Esposito MT, Passaro F, Parisi S, Lombardo B, Russo T, Pastore L. Angiotensin receptor i stimulates osteoprogenitor proliferation through tgfbeta-mediated signaling. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2015;230:1466–1474. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mendez-Ferrer S, Michurina TV, Ferraro F, Mazloom AR, Macarthur BD, Lira SA, Scadden DT, Ma’ayan A, Enikolopov GN, Frenette PS. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010;466:829–834. doi: 10.1038/nature09262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Y, Lv J, Guo H, Wei X, Li W, Xu Z. Hypoxia-induced proliferation in mesenchymal stem cells and angiotensin ii-mediated pi3k/akt pathway. Cell Biochemistry and Function. 2015;33:51–58. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Diop-Frimpong B, Chauhan VP, Krane S, Boucher Y, Jain RK. Losartan inhibits collagen i synthesis and improves the distribution and efficacy of nanotherapeutics in tumors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:2909–2914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018892108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lam BS, Cunningham C, Adams GB. Pharmacologic modulation of the calcium-sensing receptor enhances hematopoietic stem cell lodgment in the adult bone marrow. Blood. 2011;117:1167–1175. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-286294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morita Y, Iseki A, Okamura S, Suzuki S, Nakauchi H, Ema H. Functional characterization of hematopoietic stem cells in the spleen. Experimental Hematology. 2011;39:351–359. e353. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Griseri T, McKenzie BS, Schiering C, Powrie F. Dysregulated hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell activity promotes interleukin-23-driven chronic intestinal inflammation. Immunity. 2012;37:1116–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Massberg S, Schaerli P, Knezevic-Maramica I, Kollnberger M, Tubo N, Moseman EA, Huff IV, Junt T, Wagers AJ, Mazo IB, von Andrian UH. Immunosurveillance by hematopoietic progenitor cells trafficking through blood, lymph, and peripheral tissues. Cell. 2007;131:994–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schofield R. The relationship between the spleen colony-forming cell and the haemopoietic stem cell. Blood Cells. 1978;4:7–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ishibashi M, Hiasa K, Zhao Q, Inoue S, Ohtani K, Kitamoto S, Tsuchihashi M, Sugaya T, Charo IF, Kura S, Tsuzuki T, Ishibashi T, Takeshita A, Egashira K. Critical role of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 receptor ccr2 on monocytes in hypertension-induced vascular inflammation and remodeling. Circulation Research. 2004;94:1203–1210. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126924.23467.A3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang GOK. Homocysteine stimulates the expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 receptor (ccr2) in human monocytes: Possible involvement of oxygen free radicals. The Biochemical Journal. 2001;357:233–240. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Libby P. Inflammation and cardiovascular disease mechanisms. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;83:456S–460S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.456S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shan Z, Zubcevic J, Shi P, Jun JY, Dong Y, Murca TM, Lamont GJ, Cuadra A, Yuan W, Qi Y, Li Q, Paton JF, Katovich MJ, Sumners C, Raizada MK. Chronic knockdown of the nucleus of the solitary tract at1 receptors increases blood inflammatory-endothelial progenitor cell ratio and exacerbates hypertension in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension. 2013;61:1328–1333. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zubcevic J, Jun JY, Kim S, Perez PD, Afzal A, Shan Z, Li W, Santisteban MM, Yuan W, Febo M, Mocco J, Feng Y, Scott E, Baekey DM, Raizada MK. Altered inflammatory response is associated with an impaired autonomic input to the bone marrow in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension. 2014;63:542–550. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zubcevic J, Santisteban MM, Pitts T, Baekey DM, Perez PD, Bolser DC, Febo M, Raizada MK. Functional neural-bone marrow pathways: Implications in hypertension and cardiovascular disease. Hypertension. 2014;63:e129–139. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.02440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Catt KJ, Cain MD, Zimmet PZ, Cran E. Blood angiotensin ii levels of normal and hypertensive subjects. British Medical Journal. 1969;1:819–821. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5647.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Savani BN, Griffith ML, Jagasia S, Lee SJ. How i treat late effects in adults after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:3002–3009. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-263095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chisi JE, Briscoe CV, Ezan E, Genet R, Riches AC, Wdzieczak-Bakala J. Captopril inhibits in vitro and in vivo the proliferation of primitive haematopoietic cells induced into cell cycle by cytotoxic drug administration or irradiation but has no effect on myeloid leukaemia cell proliferation. British Journal of Haematology. 2000;109:563–570. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.