Abstract

Background:

Insulin resistance is a measure of metabolic stress in the perioperative period. Before now, no clinical trial has determined the summative effects of glutamine, L-carnitine, and antioxidants as metabolic conditioning supplements in the perioperative period.

Objectives:

The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of a new conditioning supplement on perioperative metabolic stress and clinical outcomes in non-diabetic patients.

Patients and Methods:

In this randomized controlled trial, 89 non-diabetic patients scheduled for coronary artery bypass grafting, with ejection fractions above 30%, were selected. Using the balanced block randomization method, the patients were allocated to one of four study arms: 1) SP (supplement/placebo): supplement seven days before and placebo 30 days after the surgery; 2) PS: placebo before and supplement after the surgery; 3) SS: supplement before and after the surgery; and 4) PP: placebo before and after the surgery. The supplement was composed of glutamine, L-carnitine, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium, which was manufactured for the first time by this research team. Five blood samples were drawn: seven days preoperatively, at the entrance to the operating room, while leaving the operating room, seven days postoperatively, and 30 days postoperatively. Levels of glucose, insulin, and HbA1c were measured in blood samples. Insulin resistance and sensitivity were calculated using a formula. Surgical complications were assessed 30 days postoperatively. Data analysis was done using one-way ANOVA, the Chi-square test, and a general linear model repeated-measures analysis with Bonferroni adjustment.

Results:

Blood glucose levels were increased postoperatively in the four groups (< 0.001), but a significantly higher increase occurred in the PP group compared to the SP (0.027), PS (0.026), and SS (0.004) groups. The superficial wound infection rate was significantly different between the four groups (0.021): 26.08% in PP, 9.09% in SP, 4.54% in PS, and 0% in SS.

Conclusions:

Our new metabolic conditioning supplement, whether given pre- or postoperatively, led to better perioperative glycemic control and decreased postsurgical wound infections in non-diabetic patients.

Keywords: Blood Glucose, Insulin Resistance, Metabolic Stress, Surgery, Infection

1. Background

Insulin resistance is a measure of metabolic stress in patients undergoing surgery (1). The magnitude of insulin resistance is associated with the severity and degree of the surgery. Major operations cause severe insulin resistance, while minor surgeries are correlated with mild resistance (1, 2). Insulin resistance increases 7- to 8-fold in adult patients undergoing elective major surgery (1), and it usually extends to 3 weeks after the surgery (3, 4). The surgical technique is also important in this regard. Compared to laparoscopic techniques, open surgery techniques cause higher degrees of insulin resistance (1).

In response to any trauma, such as surgery, several neuroendocrine changes occur, including increased plasma concentrations of cortisol, glucagon, and catecholamines, as well as increased levels of cytokines and immunologic responses (1, 2). These changes lead to a decreased insulin-to-glucagon ratio, and thus insulin resistance occurs (5, 6). Other factors also affect postoperative insulin resistance, such as postoperative oxidative stress, impaired function of skeletal muscle mitochondria, complete bed rest, and pain (1, 3, 7).

As a stress marker, postoperative insulin resistance is closely associated with clinical outcomes (8). In a study by Sato et al., insulin sensitivity that is decreased by 50% in patients undergoing abdominal surgery was related to 5 - 6 times as many major complications and 10 times as many severe infections. In other words, with a 1 mg/kg/minute decrease in insulin sensitivity, the incidence rates of major complications (OR: 2.23), severe infections (OR: 4.98), and minor infections (OR: 1.99) were increased (2).

Perioperative insulin resistance is accompanied by hyperglycemia (5). Acute hyperglycemia leads to increased inflammation, vulnerability to infection, and multiorgan system dysfunction via decreased nitric oxide production in the endothelium, decreased vasodilation, decreased complement function, increased cytokine levels, increased expression of adhesion molecules in leukocytes and endothelium, and impaired neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytosis (6, 9). Based on Van den Berghe et al.’s study, even a moderate (6 - 8 mM) increase in perioperative glucose concentration leads to increased mortality and morbidity (10).

Different approaches have been proposed to control perioperative insulin resistance, such as preoperative carbohydrate loading and early postoperative enteral feeding (3, 11). Studies have also revealed that metabolic conditioning using arginine, glutamine, and antioxidants helps to control insulin resistance in the perioperative period (3). Glutamine can control insulin resistance by metabolic regulation pre- and postoperatively via decreased muscle cell injury, increased antioxidant capacity, and increased peripheral glucose utilization (3, 12). The results of a meta-analysis of 14 clinical trials showed that postoperative intravenous glutamine leads to decreased length of hospital stays and fewer complications in surgical patients (3, 13). It is also reported that using antioxidants, such as vitamin C and E, as preconditioning agents reduces free-radical-induced complications from surgery (14, 15).

A newly recognized preoperative metabolic regulatory factor, which is also considered an adjunctive therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus, is L-carnitine (3, 16-18). L-carnitine can control insulin resistance via increased fatty acid oxidation (19). It also facilitates glucose utilization via increased pyruvate dehydrogenase activity (19), and it can control postoperative oxidative stress (20).

Before now, no clinical trial has evaluated the summative effects of carnitine, glutamine, and antioxidants. In a trial by Awad et al. (21), the effects of an oral nutritional supplement containing carbohydrate, glutamine, and antioxidants were assessed in 20 patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Patients received either 600 mL of the supplement or a placebo the evening before surgery and an additional 300 mL 3 - 4 hours before anesthesia. A 300-mL aliquot of ONS contained 50 g of carbohydrate, 15 g of glutamine, and antioxidants. Intraoperative liver glycogen reserves, plasma glutamine, and antioxidant concentrations increased after supplement ingestion. Muscle pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK4), forkhead transcription factor 1 (FOXO1), and metallothionein 1A (a marker of cellular oxidative stress) expressions were lower in the supplement group. It was proposed that preoperative ingestion of this oral nutritional supplement can reduce insulin resistance through lowering muscle PDK4 mRNA and protein expression (21).

2. Objectives

The role of insulin resistance is established in postoperative glycemic control and postsurgical morbidity and mortality, while metabolic conditioning agents such as glutamine, L-carnitine, and antioxidants play roles in the postoperative phase. In consideration of this, the present study aimed to determine the effects of a new metabolic conditioning supplement composed of glutamine, L-carnitine, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium, taken pre- and postoperatively, on perioperative metabolic stress and clinical surgical outcomes in non-diabetic patients.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Study Participants

The participants in the present study were selected from male and female patients scheduled for on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery at three government hospitals: Namazi, Faghihi, and Al-Zahra. These are referral hospitals for Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

The inclusion criteria were age of 30 - 70 years, ejection fraction above 30%, serum creatinine level less than 1.5 mg/dL, undergoing on-pump CABG in one of the above-named hospitals, not taking antioxidant supplements in the previous month, and being included in the surgery schedule at least eight days before the operation. Patients scheduled for off-pump CABG, valve repair, or emergency operations, as well as those with diabetes mellitus, infectious disease, metabolic disease, humoral disease, immunological disease, or stroke, were excluded from the study.

The sample size was determined based on a trial on the effect of L-carnitine on HOMA-IR, an insulin resistance index (19). Considering α = 0.05, 1-β = 0.90, difference = 0.8, and SD = 0.8, the sample size was calculated to be 22 patients in each arm (88 patients in the four groups). After eligible patients were identified, they were given oral and written explanations of the study, including its goal, benefits, and procedure, and were asked to read and sign an informed consent document. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the Research Council of the Deputy of Research Affairs of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

From June 2013 to March 2014, the patients who met all of the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria were enrolled consecutively, except for those who refused to enter the trial.

3.2. Supplement

The supplement used in the present study was composed of glutamine (15 g), L-carnitine (3 g), vitamin C (750 mg), vitamin E (250 mg), and selenium (150 μg). This supplement was manufactured for the first time by the research team, under the supervision of a pharmaceutics specialist. The powders were mixed with a cubic mixer, and a homogenous powder was packed into sachet forms for daily use. The patients’ instructions were to suspend the contents of one sachet in a glass of cold water and drink it after a meal.

The placebo sachets contained 5 g of starch powder. The same flavoring agent was used in the supplement and the placebo, and both types of sachet (drug and placebo) were tested blindly in volunteers to confirm that they were not distinguishable. There was no distinguishable difference in the packaging of the supplement and placebo.

3.3. Intervention Design

A randomized, placebo-controlled trial was carried out after the eligible patients were recruited between June 2013 and March 2014. We used balanced block randomization for random allocation of the patients into four groups. With a block size of four per group (A, B, C, D), there were 24 possible combinations. Each number in the random-number sequence in turn selected the next block, determining the next four participant allocations. Group SP received the supplement (one sachet daily) starting seven days before the surgery and the placebo (one sachet daily) for 30 days after the surgery. Group PS received the placebo for seven days before the surgery and the supplement for 30 days post-surgery. Group SS received the supplement for seven days before and 30 days after the surgery. Group PP received the placebo for seven days before and 30 days after the surgery.

A total of five blood samples were drawn from each patient. The first 7-mL venous sample was taken seven days before the operation, after eight hours of fasting. Then, depending on the patient’s allocation, seven sachets of supplement or placebo were provided, with instructions to take one sachet daily. The supplement or placebo was taken from the day of the first blood sample until the day before the operation. On the day of the operation, the second blood sample was drawn upon arrival in the operating room. The third blood sample was drawn at the end of the operation, as the patient was leaving the operating room. The supplement or placebo was restarted after extubation on the second day postoperatively. At discharge, additional supplement/placebo sachets were given to the patients, and the fourth blood sample was drawn seven days after the operation. The fifth sample was collected at 30 days. Complications from the surgery were assessed 30 days postoperatively, including mortality rate, myocardial infarction, requirement for intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), cerebrovascular accident, dialysis, serious or minor infections, and blood-product transfusions.

The demographic data were collected with interviews. Anthropometric assessments included measurement of weight and height. Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using the Seca 713 scale, with the subjects minimally clothed. Height was determined using non-stretchable measuring tape, without shoes, and body mass index was then calculated by dividing weight (kg) by squared height (m2). All of the equipment was calibrated each morning.

Based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines, a superficial wound infection was defined in this study as an infection limited to the skin and subcutaneous tissue with a clinical presentation of erythema, drainage, low-grade fever, and sternal instability, while a deep sternal wound infection (DSWI) reached the sternum but did not involve it. The diagnosis of DSWI required one of the following criteria: (1) detection of an organism in a culture of mediastinal tissue or fluid; (2) mediastinitis seen during the operation; or (3) either chest pain, sternal instability, or fever of > 38°C, and either purulent drainage from the mediastinum, isolation of an organism present in a blood culture, or culture of the mediastinal area (22, 23).

Based on the CDC criteria for the diagnosis of nosocomial pneumonia, clinical factors (such as fever and leukocytosis), radiological criteria (including persistent new findings on chest radiograph), and microbiologic evidence were all taken into account (24).

The clinical definition of urinary tract infection (UTI) was based on the presence of a minimum of one of the following characteristics: specific and nonspecific micturition-related symptoms and signs, a positive test (nitrite test, leukocyte esterase test, dipslide, or culture), antibiotic treatment for UTI, or UTI reported in the medical record (25). Specific symptoms and signs were pain before, during, or after micturition; increased frequency of micturition; abdominal pain; hematuria; foul smell; and common signs of sickness (fever > 37.9°C or 1.5°C above baseline temperature, chills, nausea, and vomiting) (25).

The diagnoses of the above-mentioned outcomes were confirmed by the surgeon. We also recorded the duration of the operation; the graft number; the cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) time; use of exogenous insulin; administration of epinephrine, dexamethasone, and hydrocortisone during the operation and in the ICU; total blood loss; duration of intubation; and length of ICU and hospital stays.

3.4. Biochemical Assessment

Blood was collected for measurement of glucose, insulin, and HbA1c. After transferring adequate amounts of the blood to EDTA-containing tubes for HbA1c measurement (for all samples except the third), blood samples were collected for serum separation. All blood samples were first centrifuged immediately after blood collection at 40 rpm for 10 - 30 minutes, and serum aliquots were stored at -70°C. To avoid day-to-day laboratory variables, all of the blood samples were analyzed in a single batch at the end of the clinical phase of the study. Serum glucose levels were measured spectrophotometrically on the BT 1500 autoanalyzer. Insulin was measured using ELISA (DRG kit), and HbA1c was measured by HPLC (Agilent, affinity technique). Before the start of measurement-taking, the instruments were calibrated using a reference standard with a known value to cover the range of interest. The measurement of that standard was performed with the instrument, and the result was compared with the known value.

Insulin resistance and sensitivity were calculated as follows (26):

3.5. Dietary Intake Assessment

The patients’ dietary intakes were evaluated upon enrollment and at the end of the study using 24-hour recall questionnaires. The food-processor software Nutritionist-4, modified by incorporating the Iranian food table, was used to calculate macro- and micronutrient consumptions.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

Data processing and analysis were done using SPSS version 17 for windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Normal distribution of the data was checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. In normally distributed data, one-way ANOVA was used to compare the variables between the four groups. Chi-square and Fisher Exact tests were used for categorical variables. General linear model repeated-measures analysis with Bonferroni adjustment was used to compare changes in time within and between the four groups. Skewed data were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test between the four groups. The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

This trial is registered with Clinicaltrial.gov (number NCT02184507), where the trial protocol can be accessed.

4. Results

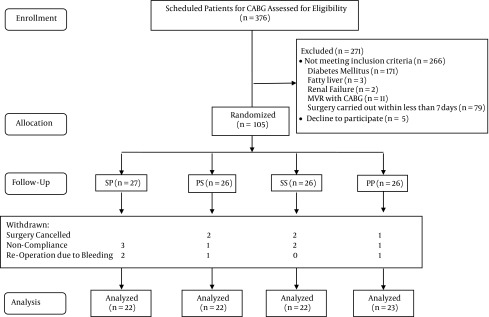

In this clinical trial, as shown in Figure 1, 105 patients were randomized, and then 16 were excluded, so that a total of 89 patients remained in the trial for analysis. The reasons for the exclusions are demonstrated in the flow diagram. There were no significant differences between the four groups at baseline (Table 1). Also, there were no significant differences between the four groups in the number of grafts, duration of surgery, administration of blood-glucose-increasing or -decreasing hormones during the operation and in the ICU, or blood loss (Table 2).

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of the Trial.

Table 1. Comparison of Demographic Variables and Baseline Characteristics in the Four Groupsa.

| Group | SP | PS | SS | PP | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 22 | 22 | 22 | 23 | |

| Age, y | 56.90 ± 7.5 | 58.72 ± 8.5 | 58.59 ± 6.4 | 55.21 ± 8.3 | 0.391 |

| Gender | 0.397 | ||||

| Male | 12 | 17 | 16 | 16 | |

| Female | 10 | 5 | 6 | 6 | |

| Body mass index, kg/m 2 | 26.19 ± 4.56 | 24.37 ± 2.55 | 25.69 ± 3.47 | 25.82 ± 3.77 | 0.382 |

| Ejection fraction, % | 51.47 ± 9.90 | 52.00 ± 7.40 | 49.95 ± 9.38 | 49.91 ± 10.05 | 0.830 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Hypertension | 11 (50.0) | 10 (45.4) | 10 (45.4) | 16 (69.5) | 0.340 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 9 (40.9) | 9 (40.9) | 8 (36.3) | 11 (47.8) | 0.891 |

| Smoking history | |||||

| Previous smoker | 1 (4.5) | 5 (22.7) | 4 (18.1) | 3 (13.0) | 0.305 |

| Current smoker | 12 (54.5) | 8 (36.36) | 11 (50.0) | 11 (47.8) | 0.744 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.02 ± 0.16 | 1.04 ± 0.21 | 1.00 ± 0.26 | 1.04 ± 0.20 | 0.902 |

aData are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

Table 2. Comparison of Surgical Parameters in the Four Groupsa.

| Variables | SP | PS | SS | PP | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of grafts | 3 (2 - 3) | 3 (3 - 3) | 3 (3 - 4) | 3 (3 - 3) | 0.209 |

| Duration of surgery, min | 174.77 ± 39.47 | 180.77 ± 56.8 | 178.57 ± 46.5 | 166.08 ± 51.7 | 0.390 |

| CPB time, min | 72.72 ± 19.29 | 76.13 ± 26.90 | 74.76 ± 21.13 | 68.34 ± 25.57 | 0.703 |

| During operation | |||||

| Epinephrine | 0.611 | ||||

| Epinephrine 0.01 - 0.05, μg/kg/min | 10 (45.45) | 7 (31.81) | 5 (22.72) | 11 (47.82) | |

| Epinephrine 0.06 - 0.1, μg/kg/min | 2 (9.09) | 3 (13.63) | 2 (9.09) | 2 (8.69) | |

| Dexamethasone, 8 - 16 mg | 4 (18.18) | 6 (27.27) | 4 (18.18) | 6 (26.08) | 0.838 |

| Hydrocortisone, 200 mg | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.34) | 1.00 |

| ICU | |||||

| Epinephrine | 0.505 | ||||

| Epinephrine 0.01 - 0.04, μg/kg/min | 12 (54.54) | 9 (40.9.) | 11 (50.0) | 14 (60.86) | |

| Epinephrine 0.05 - 0.08, μg/kg/min | 4 (18.18) | 9 (40.90) | 8 (36.36) | 7 (30.43) | |

| Epinephrine 0.08 - 0.11, μg/kg/min | 6 (27.27) | 4 (18.18) | 3 (13.63) | 2 (8.69) | |

| Dexamethasone 2 - 8, mg | 2 (9.09) | 2 (9.09) | 0 | 3 (13.04) | 0.504 |

| Hydrocortisone 10 - 200, mg | 3 (13.63) | 3 (13.63) | 3 (13.63) | 3 (13.04) | 1.00 |

| Insulin 3 - 15, units | 4 (18.18) | 5 (22.72) | 2 (9.09) | 4 (17.39) | 0.720 |

| Blood loss, mL b | 815 (465 - 1185) | 770 (500 - 1190) | 770 (495 - 1172) | 770 (540 - 1650) | 0.980 |

Abbreviation: CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass.

aData are expressed as No. (%), median (interquartile range), or mean ± SD.

bTotal drainage during the first 48 hours postoperatively in patients with chest tubes.

The changes in the measured parameters during the trial are shown in Table 3. The time-treatment interaction was significant for none of the parameters. Blood glucose levels increased postoperatively in the four groups, and the between-group differences were significant (0.003). In the post hoc analysis, there was a significant difference between the PP group and the SP (0.027), PS (0.026), and SS (0.004) groups.

Table 3. Comparisons of Measured Parameters Between and Within Groupsa.

| Group | −7 Days (1) | Pre OP (2) | Post OP (3) | +7 Days (4) | +30 Days (5) | Within Groups | Time-Treatment Interaction | Between Groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood glucose | < 0.001; 3: 1,2,4,5 (< 0.001) b; 4: 1,2,3,5 (< 0.001) | 0.236 | 0.003; SP: PP (0.027) b; PS: PP (0.026); SS: PP (0.004) | |||||

| SP | 93.18 ± 9.9 | 93.95 ± 15.8 | 164.50 ± 44.4 | 106.31 ± 21.6 | 95.72 ± 12.8 | |||

| PS | 92.19 ± 11.3 | 92.04 ± 13.0 | 167.76 ± 42.0 | 108.47 ± 27.1 | 92.00 ± 11.3 | |||

| SS | 99.00 ± 12.6 | 91.66 ± 22.8 | 153.80 ± 37.2 | 99.95 ± 12.9 | 94.71 ± 15.6 | |||

| PP | 101.68 ± 13.1 | 110.45 ± 34.8 | 189.31 ± 43.3 | 116.50 ± 21.9 | 102.13 ± 16.1 | |||

| Insulin (μU/mL) | < 0.001; 3: 1,2,5 (< 0.001) b; 3: 4 (0.001); 4: 1,3 (0.001); 4: 5 (0.018) | 0.686 | 0.855 | |||||

| SP | 7.90 ± 3.9 | 11.77 ± 5.8 | 16.51 ± 8.4 | 10.84 ± 6.0 | 8.94 ± 4.5 | |||

| PS | 7.81 ± 3.9 | 8.49 ± 5.3 | 16.11 ± 11.6 | 12.66 ± 6.0 | 9.03 ± 3.6 | |||

| SS | 11.00 ± 11.1 | 9.32 ± 6.3 | 16.60 ± 12.6 | 11.50 ± 8.1 | 9.96 ± 5.9 | |||

| PP | 8.5 ± 3.4 | 11.05 ± 6.6 | 17.04 ± 11.6 | 12.15 ± 4.9 | 11.1 ± 5.0 | |||

| HbA1c, % | 0.007; 1: 2 (0.033) b | 0.375 | 0.090 | |||||

| SP | 6.10 ± 0.3 | 6.14 ± 0.4 | - | 5.96 ± 0.4 | 5.87 ± 0.3 | |||

| PS | 5.93 ± 0.4 | 5.79 ± 0.3 | - | 5.90 ± 0.4 | 5.67 ± 0.4 | |||

| SS | 6.00 ± 0.4 | 6.06 ± 0.5 | - | 6.00 ± 0.7 | 5.64 ± 0.5 | |||

| PP | 6.12 ± 0.4 | 6.11 ± 0.5 | - | 5.94 ± 0.7 | 6.05 ± 0.5 | |||

| QUICKI index | < 0.001; 3: 1,2,4,5 (< 0.001) b; 4: 1,3 (< 0.001) | 0.607 | 0.184 | |||||

| SP | 0.35 ± 0.03 | 0.34 ± 0.04 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 0.33 ± 0.03 | 0.35 ± 0.05 | |||

| PS | 0.36 ± 0.04 | 0.36 ± 0.05 | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 0.33 ± 0.05 | 0.34 ± 0.02 | |||

| SS | 0.35 ± 0.04 | 0.36 ± 0.05 | 0.30 ± 0.03 | 0.34 ± 0.04 | 0.35 ± 0.04 | |||

| PP | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 0.33 ± 0.03 | 0.29 ± 0.03 | 0.32 ± 0.03 | 0.33 ± 0.03 | |||

| Bennett’s index | < 0.001; 3: 1,2,4,5 (< 0.001) b | 0.303 | 0.300 | |||||

| SP | 2.04 ± 1.7 | 1.70 ± 1.0 | 0.95 ± 0.2 | 1.44 ± 0.5 | 1.60 ± 0.4 | |||

| PS | 2.25 ± 2.0 | 2.84 ± 2.9 | 1.04 ± 0.3 | 1.38 ± 0.6 | 1.59 ± 0.4 | |||

| SS | 1.83 ± 0.9 | 2.62 ± 3.1 | 1.15 ± 0.4 | 1.68 ± 0.8 | 1.78 ± 0.9 | |||

| PP | 1.61 ± 0.6 | 1.59 ± 0.7 | 1.18 ± 1.4 | 1.50 ± 1.3 | 1.45 ± 0.6 | |||

| HOMA-IR | < 0.001; 3: 1,2,4,5 (< 0.001) b; 4: 1,3,5 (< 0.001) | 0.861 | 0.798 | |||||

| SP | 1.80 ± 0.8 | 2.87 ± 1.8 | 6.98 ± 4.8 | 2.87 ± 1.7 | 2.13 ± 1.1 | |||

| PS | 1.73 ± 0.9 | 1.94 ± 1.4 | 6.42 ± 4.7 | 3.34 ± 1.6 | 2.01 ± 0.8 | |||

| SS | 2.29 ± 1.9 | 2.12 ± 1.7 | 6.26 ± 5.5 | 2.84 ± 2.3 | 2.29 ± 1.4 | |||

| PP | 2.08 ± 0.8 | 2.63 ± 1.7 | 6.62 ± 3.3 | 3.49 ± 1.7 | 2.77 ± 1.2 | |||

| FIRI | < 0.001; 3: 1,2,4,5 (< 0.001) b; 4: 1,3,5 (< 0.001) | 0.845 | 0.601 | |||||

| SP | 1.62 ± 0.8 | 2.59 ± 1.6 | 6.28 ± 4.3 | 2.58 ± 1.6 | 1.92 ± 1.0 | |||

| PS | 1.56 ± 0.8 | 1.75 ± 1.2 | 5.77 ± 4.2 | 3.00 ± 1.4 | 1.81 ± 0.7 | |||

| SS | 2.06 ± 1.7 | 1.91 ± 1.5 | 5.64 ± 5.0 | 2.56 ± 2.1 | 2.06 ± 1.3 | |||

| PP | 1.93 ± 0.7 | 2.85 ± 2.7 | 5.99 ± 2.9 | 3.18 ± 1.5 | 2.58 ± 1.1 |

aData are expressed as mean ± SD.

bPair-wise comparisons.

The surgical outcomes are demonstrated in Table 4. Two deaths occurred: one in the SS group on the patient’s first night in the ICU, and the second one in the PP group two weeks after discharge from the hospital. With regard to infectious complications, DSWI was seen in only one patient from the PP group. The superficial wound infection rate was significantly different in the four groups: 26.08% in PP, 9.09% in SP, 4.54% in PS, and 0% in SS.

Table 4. Clinical Outcomes and Incidence of Adverse Events in the Study Patientsa.

| SP | PS | SS | PP | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 22 | 22 | 22 | 23 | NA |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.54) | 1 (4.3) | 0.865 |

| MI | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.3) | 1.00 |

| IABP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Dialysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| CVA | 1 (4.54) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.34) | 1.00 |

| Severe infection | |||||

| Pneumonia (requiring ventilation) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| DSWI | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.34) | 1.00 |

| Minor infection | |||||

| Pneumonia (not requiring ventilation) | 2 (9.09) | 2 (9.09) | 1 (4.54) | 3 (13.04) | 0.956 |

| Superficial wound infection | 2 (9.09) | 1 (4.54) | 0 | 6 (26.08) | 0.025 |

| UTI | 2 (9.09) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.34) | 0.455 |

| Blood transfusion | |||||

| RBC, mL/patient | |||||

| Number (percent) | 20 (90.90) | 19 (86.36) | 18 (81.81) | 21 (91.30) | 0.886 |

| Unit/Patient | 3.55 ± 2.36 | 2.72 ± 1.79 | 2.74 ± 1.72 | 3.84 ± 2.15 | 0.176 |

| FFP, mL/patient | |||||

| Number (percent) | 3 (13.63) | 4 (18.18) | 2 (9.09) | 6 (26.08) | 0.502 |

| Unit/Patient | 3.15 ± 0.78 | 3.85 ± 1.30 | 3.00 ± 1.41 | 4.14 ± 2.11 | 0.786 |

| Platelets (mL/patient) | |||||

| number (percent) | 1 (4.54) | 1 (4.54) | 2 (9.09) | 1 (4.34) | 0.935 |

| unit/patient | 2.0 | 4.0 | 4.00 ± 2.8 | 4.0 | 0.734 |

| Intubation time, h | 10 (8 - 14) | 9.9 (8.2 - 12.0) | 9.7 (7.1 - 11.1) | 10.0 (6.5 - 13.5) | 0.886 |

| ICU stay, h | 43.0 (40.5 - 48.0) | 43.0 (39.7 - 51.0) | 42 (41 - 43) | 43 (39 - 44) | 0.598 |

| Hospital stay, d | 3 (3 - 4) | 4 (3 - 4) | 3 (3 - 4) | 4 (3 - 4) | 0.311 |

Abbreviations:CVA, cerebrovascular accident; DSWI, deep sternal wound infection; FFP: fresh frozen plasma; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; MI, myocardial infarction; RBC, red blood cell; UTI, urinary tract infection.

aData are expressed as No. (%), median (interquartile range), or Mean ± SD.

With regard to the participants’ dietary intake, there were no significant differences in the intake of total calories, carbohydrates, protein, fat, fiber, vitamin C, vitamin E, or selenium among the four groups at the beginning and the end of the trial. In addition, there were no supplement-related complications.

5. Discussion

The results of the present study revealed for the first time that administration of a new metabolic conditioning supplement, whether pre- or postoperatively, led to better perioperative glycemic control and decreased post-CABG wound infection in non-diabetic patients.

Concerning glycemic control in the perioperative period, few studies have investigated the effects of metabolic conditioning using insulin-resistance-reducing agents such as arginine, glutamine, and antioxidants (3, 21, 27). With the introduction of L-carnitine as a novel conditioning agent (3), no clinical trial before now has evaluated the summative effects of glutamine, L-carnitine, and antioxidants as a metabolic conditioning supplement on surgery-induced metabolic stress. Our trial is also unique in its relatively long period of supplement administration pre- and post-surgery.

Postoperative blood glucose increased significantly in all four groups with the same pattern, but compared to the SP, PS, and SS groups, a significantly higher increase occurred in the PP group. Serum insulin levels and insulin resistance markers (HOMA-IR, FIRI) also increased significantly postoperatively, and again decreased to near the preoperative level after 30 days, but there were no significant differences between the four groups. Insulin sensitivity indices (QUICKI, Bennett’s) likewise decreased immediately postoperatively, then increased by 30 days postoperatively, without any significant differences between the four groups. In addition, there were no significant differences between the four groups with regard to HbA1c levels.

As expected, our metabolic conditioning supplement led to better glycemic control in the perioperative period. In a study by Alvez et al., intravenous administration of 50 g of L-Alanyl glutamine three hours prior to surgery, in patients with critical limb ischemia undergoing operative revascularization, resulted in reduced muscle cell damage, enhanced antioxidant capacity, and improved glucose utilization by the peripheral tissues (28). Glutamine supplementation has been proven to increase insulin-dependent glucose utilization in the peripheral tissues, leading to better glycemic control without changing the insulin concentration, via increasing insulin sensitivity in the periphery (12, 29).

Insulin resistance is associated with impaired mitochondrial function, which leads to decreased fatty acid oxidation. Inadequate and inefficient oxidative phosphorylation probably leads to oxidative stress and triglyceride accumulation in the skeletal muscles, which decreases insulin sensitivity (19, 30). Studies have revealed that L-carnitine concentration is reduced in diabetic patients (19). Low fatty acid oxidation is secondary to reduced carnitine palmitoyltransferase (CPT) activity (30), and it is proposed that exogenous carnitine supplementation may eliminate the deficit (19).

We used HOMA-IR, QUICKI, Bennett’s and FIRI to measure insulin resistance and sensitivity. Ljunggren et al. showed that HOMA-IR and QUICKI are unable to reflect the magnitude of surgery-induced insulin resistance. Compared to the clamp method, which is the gold standard method of assessing insulin sensitivity, HOMA-IR and QUICKI detected only 10% of postoperative insulin resistance. These static methods reflect the balance between insulin and glucose levels in the absence of any metabolic stress, while the dynamic method (the clamp technique) measures insulin resistance in hyperinsulinemic situations (31). In fact, these approaches reflect different aspects of insulin resistance. The clamp method measures insulin resistance developing in peripheral tissues, such as muscle and adipose tissue, while HOMA-IR and QUICKI act as markers of hepatic insulin resistance (31, 32). Ljunggren concluded that surgery-induced insulin resistance must be attributed to metabolic alterations in the peripheral tissues rather than to hepatic metabolism (31). Considering the established role of glutamine and L-carnitine in alleviating insulin resistance in the peripheral tissues, we can claim that our metabolic conditioning supplement played a role in controlling peripheral-tissue insulin resistance, and its effects were reflected in the glycemic control and infection rates. However, the static methods we used to measure insulin resistance and sensitivity (HOMA-IR, FIRI, QUICKI, and Bennett’s) were unable to detect our supplement’s effect on peripheral insulin resistance. We can also conclude that our metabolic conditioning agent did not have any effect on hepatic insulin resistance. Since HbA1c represents the mean glycemia level over the preceding 3-4 months (33), it seems logical that changes in its value are not statistically significant.

Surgical-site infection is the third most prevalent (17%) type of all nosocomial infections in hospitalized patients, and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the postoperative period (34, 35). Perioperative hyperglycemia is recognized as a modifiable risk factor for surgical-site infection (36). In a cohort of 149 diabetic patients undergoing colorectal resection, the mean 48-hour postoperative capillary glucose of > 200 mg/dL was independently associated with a greater than 3-fold increase in surgical-site infections, and this relationship was independent of the dose and regimen of the postoperative insulin administration (37). This means that glycemic control, rather than the dosage and regimen of the administered insulin, plays a role in infection control.

Several studies have also shown that by controlling postoperative blood glucose to levels below 11.0 mmol/L, the rate of sternal wound infections is reduced up to three times in cardiac surgery patients (38, 39). The largest randomized controlled trial (the Leuven trial), which included more than 1,500 critically ill patients, showed that with strict blood glucose control (<110 mg/dL), compared to a level of < 200 mg/dL, bloodstream infections were decreased and the mortality rate was reduced (40). The effects of hyperglycemia on a wound take place when the wound is in the inflammatory phase of healing (37). Hyperglycemia upregulates the release of pro-inflammatory mediators and suppresses the immune system (36).

In our study, DSWI occurred only in one patient from the PP group, and the minor wound infection rate was significantly higher in the PP group (26.08%) compared to the SP (9.09%), PS (4.54%), and SS (0%) groups. This result is in agreement with that of blood glucose levels in our study. Since the infection rate was the lowest in the SS group, we can conclude that our novel supplement must be taken both before and after the operation to exert its best effect on postoperative infection control.

In this trial, the metabolic conditioning supplement was taken seven days prior to the operation, which is in contrast to other studies in which the conditioning agents were ingested some hours before the surgery. Therefore, the effects seen in our study are not the acute effects of the ingredients.

The strengths of our study were its new metabolic conditioning supplement and the relatively long period of its administration. A limitation of our study was the use of formulas for estimating insulin resistance and sensitivity, instead of the hyperinsulinemic normoglycemic clamp technique. It is recommended that future studies evaluate the effects of our new supplement in diabetic patients undergoing major surgery. The effect of carbohydrate-loading while taking this metabolic conditioning supplement is also worthy of further study.

Our new metabolic conditioning supplement, whether taken pre- or postoperatively, led to better perioperative glycemic control and to decreased post-CABG wound infections in non-diabetic patients. The supplement’s best effect on the prevention of wound infection was seen when it was ingested both before and after the surgery.

Acknowledgments

We thank Osvah Pharmaceutical Co. for supplying the vitamin C, and Pegah Dairy Packaging Industries Co. for supplying the 5-layer film for packaging the supplement. The authors would also like to thank Dr. B. Ghasemzadeh and Dr. J. Badr for their cooperation, and also Dr. N. Shokrpour, at the Center for Development of Clinical Research at Namazi Hospital, for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contribution:Marzieh Akbarzadeh: study concept and design, study performance, biochemical analysis, manuscript preparation; Mohammad Hassan Eftekhari: study concept and design, study supervision, manuscript revision; Masih Shafa: clinical data gathering, manuscript revision; Shohreh Alipour: new supplement manufacturing, manuscript revision; Jafar Hassanzadeh: Statistical analysis, manuscript revision

Funding/Support:This article was extracted from Marzieh Akbarzadeh’s PhD dissertation and funded by Grant Number 91-6447 from Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

References

- 1.Ljungqvist O. Jonathan E. Rhoads lecture 2011: Insulin resistance and enhanced recovery after surgery. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2012;36(4):389–98. doi: 10.1177/0148607112445580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sato H, Carvalho G, Sato T, Lattermann R, Matsukawa T, Schricker T. The association of preoperative glycemic control, intraoperative insulin sensitivity, and outcomes after cardiac surgery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(9):4338–44. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Awad S, Lobo DN. Metabolic conditioning to attenuate the adverse effects of perioperative fasting and improve patient outcomes. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2012;15(2):194–200. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32834f0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ljungqvist O. Modulating postoperative insulin resistance by preoperative carbohydrate loading. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2009;23(4):401–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nygren J. The metabolic effects of fasting and surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2006;20(3):429–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipshutz AK, Gropper MA. Perioperative glycemic control: an evidence-based review. Anesthesiology. 2009;110(2):408–21. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181948a80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Awad S, Stephenson MC, Placidi E, Marciani L, Constantin-Teodosiu D, Gowland PA, et al. The effects of fasting and refeeding with a ‘metabolic preconditioning’drink on substrate reserves and mononuclear cell mitochondrial function. Clin Nutr . 2010;29(4):538–44. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ljungqvist O, Nygren J, Thorell A. Insulin resistance and elective surgery. Surgery. 2000;128(5):757–60. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.107166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turina M, Fry DE, Polk HJ. Acute hyperglycemia and the innate immune system: clinical, cellular, and molecular aspects. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(7):1624–33. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000170106.61978.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van den Berghe G, Wilmer A, Milants I, Wouters PJ, Bouckaert B, Bruyninckx F, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in mixed medical/surgical intensive care units: benefit versus harm. Diabetes. 2006;55(11):3151–9. doi: 10.2337/db06-0855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Awad S, Lobo DN. What's new in perioperative nutritional support? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2011;24(3):339–48. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e328345865e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grau T, Bonet A, Minambres E, Pineiro L, Irles JA, Robles A, et al. The effect of L-alanyl-L-glutamine dipeptide supplemented total parenteral nutrition on infectious morbidity and insulin sensitivity in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(6):1263–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820eb774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, Jiang ZM, Nolan MT, Jiang H, Han HR, Yu K, et al. The impact of glutamine dipeptide-supplemented parenteral nutrition on outcomes of surgical patients: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2010;34(5):521–9. doi: 10.1177/0148607110362587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baines M, Shenkin A. Use of antioxidants in surgery: a measure to reduce postoperative complications. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2002;5(6):665–70. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000038810.16540.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milei J, Ferreira R, Grana DR, Boveris A. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage in coronary artery bypass graft surgery: effects of antioxidant treatments. Compr Ther. 2001;27(2):108–16. doi: 10.1007/s12019-996-0004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mynatt RL. Carnitine and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2009;25 Suppl 1:S45–9. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Power RA, Hulver MW, Zhang JY, Dubois J, Marchand RM, Ilkayeva O, et al. Carnitine revisited: potential use as adjunctive treatment in diabetes. Diabetologia. 2007;50(4):824–32. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0605-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ringseis R, Keller J, Eder K. Role of carnitine in the regulation of glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity: evidence from in vivo and in vitro studies with carnitine supplementation and carnitine deficiency. Eur J Nutr. 2012;51(1):1–18. doi: 10.1007/s00394-011-0284-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molfino A, Cascino A, Conte C, Ramaccini C, Rossi Fanelli F, Laviano A. Caloric restriction and L-carnitine administration improves insulin sensitivity in patients with impaired glucose metabolism. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2010;34(3):295–9. doi: 10.1177/0148607109353440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pignatelli P, Tellan G, Marandola M, Carnevale R, Loffredo L, Schillizzi M, et al. Effect of L-carnitine on oxidative stress and platelet activation after major surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2011;55(8):1022–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2011.02487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Awad S, Constantin-Teodosiu D, Constantin D, Rowlands BJ, Fearon KC, Macdonald IA, et al. Cellular mechanisms underlying the protective effects of preoperative feeding: a randomized study investigating muscle and liver glycogen content, mitochondrial function, gene and protein expression. Ann Surg. 2010;252(2):247–53. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e8fbe6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh K, Anderson E, Harper JG. Overview and management of sternal wound infection. Semin Plast Surg. 2011;25(1):25–33. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1275168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salehi Omran A, Karimi A, Ahmadi SH, Davoodi S, Marzban M, Movahedi N, et al. Superficial and deep sternal wound infection after more than 9000 coronary artery bypass graft (CABG): incidence, risk factors and mortality. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:112. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang HC, Chen CM, Kung SC, Wang CM, Liu WL, Lai CC. Differences between novel and conventional surveillance paradigms of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(2):133–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caljouw MA, van den Hout WB, Putter H, Achterberg WP, Cools HJ, Gussekloo J. Effectiveness of cranberry capsules to prevent urinary tract infections in vulnerable older persons: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial in long-term care facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(1):103–10. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akbarzadeh M, Eftekhari MH, Dabbaghmanesh MH, Hasanzadeh J, Bakhshayeshkaram M. Serum IL-18 and hsCRP correlate with insulin resistance without effect of calcitriol treatment on type 2 diabetes. Iran J Immunol. 2013;10(3):167–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drover JW, Dhaliwal R, Weitzel L, Wischmeyer PE, Ochoa JB, Heyland DK. Perioperative use of arginine-supplemented diets: a systematic review of the evidence. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212(3):385–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alves WF, Aguiar EE, Guimaraes SB, da Silva Filho AR, Pinheiro PM, Soares Gdos S, et al. L-alanyl-glutamine preoperative infusion in patients with critical limb ischemia subjected to distal revascularization reduces tissue damage and protects from oxidative stress. Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24(4):461–7. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwashita S, Mikus C, Baier S, Flakoll PJ. Glutamine supplementation increases postprandial energy expenditure and fat oxidation in humans. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2006;30(2):76–80. doi: 10.1177/014860710603000276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manco M, Calvani M, Mingrone G. Effects of dietary fatty acids on insulin sensitivity and secretion. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2004;6(6):402–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-8902.2004.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ljunggren S, Nystrom T, Hahn RG. Accuracy and precision of commonly used methods for quantifying surgery-induced insulin resistance: Prospective observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2014;31(2):110–6. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdul-Ghani MA, Jenkinson CP, Richardson DK, Tripathy D, DeFronzo RA. Insulin secretion and action in subjects with impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance: results from the Veterans Administration Genetic Epidemiology Study. Diabetes. 2006;55(5):1430–5. doi: 10.2337/db05-1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koenig RJ, Peterson CM, Jones RL, Saudek C, Lehrman M, Cerami A. Correlation of glucose regulation and hemoglobin AIc in diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1976;295(8):417–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197608192950804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Niaimi AN, Ahmed M, Burish N, Chackmakchy SA, Seo S, Rose S, et al. Intensive postoperative glucose control reduces the surgical site infection rates in gynecologic oncology patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(1):71–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Lissovoy G, Fraeman K, Hutchins V, Murphy D, Song D, Vaughn BB. Surgical site infection: incidence and impact on hospital utilization and treatment costs. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37(5):387–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kao LS, Meeks D, Moyer VA, Lally KP. Peri-operative glycaemic control regimens for preventing surgical site infections in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD006806. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006806.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McConnell YJ, Johnson PM, Porter GA. Surgical site infections following colorectal surgery in patients with diabetes: association with postoperative hyperglycemia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13(3):508–15. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0734-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Furnary AP, Wu Y, Bookin SO. Effect of hyperglycemia and continuous intravenous insulin infusions on outcomes of cardiac surgical procedures: the Portland Diabetic Project. Endocr Pract. 2004;10 Suppl 2:21–33. doi: 10.4158/EP.10.S2.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Latham R, Lancaster AD, Covington JF, Pirolo JS, Thomas CJ. The association of diabetes and glucose control with surgical-site infections among cardiothoracic surgery patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22(10):607–12. doi: 10.1086/501830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, Verwaest C, Bruyninckx F, Schetz M, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(19):1359–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]