Abstract

Purpose

Conduct a social network analysis of the health and non-health related organizations that participate in the Bogotá’s Ciclovía Recreativa (Ciclovía).

Design

Cross sectional study.

Setting

Ciclovía is a multisectoral community-based mass program in which streets are temporarily closed to motorized transport, allowing exclusive access to individuals for leisure activities and PA.

Subjects

25 organizations that participate in the Ciclovía.

Measures

Seven variables were examined using network analytic methods: relationship, link attributes (integration, contact, and importance), and node attributes (leadership, years in the program, and the sector of the organization).

Analysis

The network analytic methods were based on a visual descriptive analysis and an exponential random graph model.

Results

Analysis shows that the most central organizations in the network were outside of the health sector and includes Sports and Recreation, Government, and Security sectors. The organizations work in clusters formed by organizations of different sectors. Organization importance and structural predictors were positively related to integration, while the number of years working with Ciclovía was negatively associated with integration.

Conclusion

Ciclovía is a network whose structure emerged as a self-organized complex system. Ciclovía of Bogotá is an example of a program with public health potential formed by organizations of multiple sectors with Sports and Recreation as the most central.

Keywords: Ciclovía, physical activity, network analysis, public health, Complex systems, chronic diseases

Indexing Key Words: Manuscript format: research; Research purpose: modeling/relationship testing, descriptive; Study design: cross sectional study; Outcome measure: relationship variable; Setting: local community; Health focus: fitness/physical activity; Strategy: policy; Target population age: youth, adults, seniors; Target population circumstances: geographic location

PURPOSE

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are the leading cause of death worldwide1. The prevalence of NCDs is increasing globally, with the majority of cases occurring in low- and middle-income countries.1,2 Physical inactivity is one of the major risk factors for NCDs, accounting for an estimated 5.3 million deaths per year.3

To address the NCD burden due to inactivity, environmental and policy approaches can be effective ways to promote physical activity (PA), creating or enhancing access to places for physical activity with outreach programs.4 Intersectoral partnerships can support the creation of healthy policies that influence physical environments. Increasing population PA requires synergistic policies through intersectoral collaboration.5

Intersectoral partnerships are useful solutions to problems that cannot be tackled in isolation by the health sector.6 Network analysis is a potential approach to evaluate and improve multisectoral partnerships.7 This approach allows the study of the interactions between heterogeneous actors with diverse goals.8 Despite the challenges of collaboration between multiple sectors, community networks of intersectoral partnerships have been useful for understanding the overall structures between agencies addressing mental health,9–11 child abuse,12 the health of the elderly,13 tobacco control,14 health disparities in cancer,15 and for the prevention of diabetes.16 Network analysis has also recently been used to assess state level active living promotion network in Hawaii.17

Ciclovía Recreativa (Ciclovía) is considered as a promising program to promote PA.18,19 Ciclovía is a multisectoral, community-based mass program in which streets are temporarily closed to motorized transport, allowing exclusive access to individuals for leisure activities and PA.18 In this program, 90% of the participants are from low and middle socioeconomic strata.20 In a recent work, a cost-benefit analysis of four Ciclovía programs showed that the programs are cost beneficial for promoting PA.21

Ciclovía programs are expanding rapidly worldwide and can be found in more than 100 cities in at least 20 countries in North, Central, and South America.22,23 Currently, there are at least 75 programs in the United States as part of the Open Streets.23 Implementation of this program at both the national and local levels requires knowledge of how multisectoral partners are working together and how collaboration could be improved. Specific information about networking, such as barriers, importance and frequency of contact, and type of collaboration, as well as structural characteristics of the organizations, are important for understanding the collaborative relationships between the organizations involved in Ciclovía.

Bogotá’s Ciclovía is of particular interest because it has a 38-year history and is currently the largest such program in the world.24 It started in 1974 with a group of students and activists who, supported by city officials, took over several streets to use their bicycles. In the 1980s the city’s Ciclovía became a weekly program in which main avenues are temporarily closed for recreation and PA. Today it has a 121-kilometer continuous circuit, its attendance ranges from 600,000 to 1,400,000 users every Sunday and holiday, and organizations from various sectors work together to make the program possible.24

The objective of this study was to conduct a network analysis of the organizations that participate in Ciclovía to: 1) Identify which organizations from the health care and out of health care sector are part of Ciclovia’s network, 2) describe the network structure, 3) describe the role of the organizations within the network 4) describe the subgroups of organizations working together in the network, 5) assess the relationship between variables or structural tendencies and the likelihood of integration between the network’s members.

METHODS

Design

The research is a cross sectional study, in which the information of the organizations that participate in the Ciclovia was collected through relational variables with the purpose to develop a network analysis.

Sample

The selection of organizations for the study had two phases. First, we conducted a review of Ciclovía’s history, in which we identified 11 main organizations.24 Second, we contacted the director of the program, who identified another 14 organizations. An individualized e-mail (including a recruitment statement) and a follow-up phone call were sent to each organization, inviting them to complete a questionnaire. The data-collection questionnaire was adapted from the Guide for Useful Interventions for Physical Activity in Brazil and Latin America’s (GUIA) network analysis project survey.25,26 All materials were translated into Spanish and culturally adapted. The questionnaire was administered face to face (77% of organizations) or by email or telephone (23% of organizations) from March to June 2009. Each participant of the study signed an informed consent form. The protocol was reviewed and approved by Universidad de los Andes’s Institutional Review Board.

Of the 25 eligible organizations, 22 responded to the survey, for an 88% response rate. Three organizations did not answer the phone call, emails, or provide an appointment during study period but did not provide a reason for refusal. The organizations were classified into the following nine sectors: 1) Sports and Recreation, which included 12% of the organizations; 2) Transport and Urban Planning, which included 20% of the organizations; 3) Health, which included 8% of the organizations; 4) Education, which included 4% of the organizations; 5) Security, which included 8% of the organizations; 6) Marketing/Services, which included 16% of the organizations; 7) Research and Academy, which included 16% of the organizations; 8) Government, which included 12% of the organizations; and 9) Environment, which included 4% of the organizations (see Figure 1 and Table 1 for definitions and functions of the organizations, acronyms and corresponding nodes).

Figure 1.

a) Network with node size based on the number of times an organization was identified as a collaborator (in-degree). b) Network with node size based on the number of ties that an organization has to other actors in the network (out-degree). c) Network with node size based on the number of times that an organization is acting as a bridge between other organizations that are not directly connected (betweenness). d) Network with node size based on how close an organization is to all the other organizations in the network (closeness)

Table 1.

Organizations participating in Ciclovía

| Organizations | Sectors | Description /Organizational mission | Functions within Ciclovía |

|---|---|---|---|

| Node 1. City Hall | Government | Designs policies and implements them through the different institutes and secretariats. | Ciclovía is an IDRD program approved by City Hall. The IDRD depends from SCRS, which in turn depends from the City Hall. |

| Node 2. Secretariat of Movility (SoM) | Transport and Urban Planning | Formulates, directs, and implements policies that ensure the mobility of the city. | The SoM evaluates and implements the IDRD requirements regarding Ciclovía connectivity problems, with the smallest possible impact on the city’s mobility. |

| Node 3. Secretariat of Government (SoG) | Government | The SoG works with City Hall to design and asses public policies in terms of human rights, security, inequality and coexistence. | As with all policies and programs, Ciclovía was assessed and approved by the SoG. |

| Node 4. Secretariat of Health (SoH) | Health | In charge of preventing disease and guaranteeing access to health services to all residents of Bogotá. | Creates the procedures that the Ciclovia personnel must follow in case of accidents or emergencies. |

| Node 5. Secretariat of Education (SoEdu) | Education | Promotes educational offerings in the city to ensure access and retention of children in the education system. | In order to graduate, high school students must perform a number of hours of community service. Some students do these hours at Ciclovía working as guides. |

| Node 6. Secretariat of Planning (SoP) | Transport and Urban Planning | Leads the integrated planning of the Capital District through guidance, coordination and monitoring of land, economic, social, environmental, and cultural policies. | Ciclovía benefits from programs developed by the SoP that are related to the built environment, the mobility of the city, and bicycle use. |

| Node 7. Secretariat of Social integration (SoSI) | Government | Designs, implements, and evaluates public policies aimed at improving the quality of life in Bogotá. | Ciclovía has recreovías, which are adaptations of public space to encourage PA among people of all ages, ethnicities, and social statuses. These programs are related to the SoSI’s goal. |

| Node 8. Secretariat of Environment (SoEnv) | Environment | Promotes and designs sustainable development and a healthy city environment. | Programs such as the Car-free Day, Night Ciclovía, and Ciclovía have a positive influence on the quality of the air and reduce noise pollution, and are therefore of interest to the SoEnv. |

| Node 9. Secretariat of Culture, Recreation and Sport (SCRS) | Sports and Recreation | The governmental institution that guarantees the cultural and recreational rights of the people who live in Bogotá. | The SCRS, with City Hall and the SoG, designs the policies that the IDRD must follow. |

| Node 10. District Institute of Recreation and Sports (IDRD, for the Spanish acronym) | Sports and Recreation | The governmental organization committed to the promotion of recreation, PA, the good use of parks, and sports in Bogotá. | The IDRD leads the Ciclovía program and is attached to the SCRS. The IDRD is in charge of designing and implementing Ciclovía. Ciclovía is designed with the SoM and with the objective of being near people’s homes and running through important avenues without compromising the city’s mobility. Once a Ciclovía corridor is approved, the IDRD promotes the new corridor, acquires the signs and hires the guides needed for Ciclovía to work. |

| Node 11. Coldeportes (Colombian Institute of Sports) | Sports and Recreation | Responsible for formulating, coordinating and monitoring the practice of sport, recreation, physical education, leisure time, and PA; aimed at improving the quality of life of Colombian society. | Coldeportes helps through the development and implementation of public policies. Through programs such as the program of Healthy Life Style, which includes the Ciclovía program as a strategy to increase physical activity. |

| Node 12. Institute of Urban Development (IDU, for the Spanish acronym) | Transport and Urban Planning | In charge of maintaining the street network and managing the city’s infrastructure projects. | The IDU is in charge of maintaining the streets. Since Ciclovía uses the same roads as the cars, the street maintenance is for car mobility as well as that of bicycles and pedestrians using the program. |

| Node 13. Metropolitan Police (MP) | Security | In charge of maintaining public order in the city. | The IDRD has a contract with the MP to provide high school graduates doing military service to supervise Ciclovía. |

| Node 14. Transit Police (TP) | Security | In charge of enforcing the traffic code and responding to traffic accidents. | Handles critical intersections throughout the city, some of which are in Ciclovía. Duty is mostly related to traffic issues. |

| Node 15. Administrative Department for the Defense of Public Space (DADEP, for the Spanish acronym) | Transport and Urban Planning | DADEP is the institution in charge of protecting Bogotá’s public space. | Ciclovía takes place in public space. The DADEP makes sure that the space and the goods that are part of the public space are well used in the program and that after the program the public space is returned to its usual form. |

| Node 16. Ministry of Health (MoH) | Health | Directs and organizes the health system to guarantee access to health services and disease prevention programs throughout the country. | The MoH has an indirect role in the Ciclovía. Through the National Plan of Public Health and obesity law promotes Ciclovías throughout the country as a strategy to promote physical activity. |

| Node 17. Chamber of Commerce (CoC) | Research and academy | Aims to increase the prosperity of Bogotá’s residents through strengthening of business skills and a competitive environment. | Looks after the city’s heritage, of which Ciclovía is a part. Among other actions, opposed an initiative to reduce the hours of Ciclovía. |

| Node 18. Academy (Universidad de los Andes) | Research and academy | Purpose is to train professionals and scientists and to contribute to the country’s scientific and technological development. | Does scientific research into Ciclovía to study its effects on public health, social capital, and other issues. |

| Node 19. Research (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]) | Research and academy | Collaborates to create the expertise, information, and tools that people and communities need to protect their health. | Works with the Ciclovía Recreativa de las Américas (CRA), which includes Bogotá’s Ciclovía. Does a systematic scientific review of health issues, workshops for health promotion and disease prevention, and development of guides to expand the CRA. |

| Node 20. Fund of Education and Road Safety (FONDATT) | Transport and Urban Planning | Responsible for the management of traffic lights and, until 2007, collecting fines for traffic violations | FONDATT was the manager of the traffic lights that run through Ciclovía until it was discontinued in December 2009. Its responsibilities were assumed by the SoM. |

| Node 21. Media (IDRD publicity department) | Marketing/Services | This node represents newspapers, radio and television channels used to communicate information. | Ciclovía, its schedule, and any changes are communicated through the media. |

| Node 22. Providers (moving company Mudanzas) | Marketing/Services | These are logistics companies in charge of organizing events. | Providers take care of the logistics involved in closing the streets to cars and assembling and dismantling pallets and stores. |

| Node 23. Sponsors (pension and severance pay fund Porvenir S.A.) | Marketing/Services | This node represents the companies that use Ciclovía to promote their products. | Sponsors promote their products through Ciclovía by paying a fee to have their brand on the event. |

| Node 24. Public services (Administrative Unit of Special Public Services UAESP) | Marketing/Services | To manage and control solid waste and provide street lighting. | Hires other company to keep Ciclovía clean; manages Ciclovía’s street lighting through Codensa, which is one of its operators. |

| Node 25. Foundation (Amigos de la Bicicleta Foundation) | Research and academy | Aim is to improve quality of life through the use of the bicycle. | Uses Ciclovía in campaigns and to promote bicycle use. |

Measures

To analyze the organizational structure of the participating organizations, seven variables were examined using network analytic methods:25,27,28 relationship, link attributes (integration, contact, and importance), and node attributes (leadership, years in the program and the sector of the organization).

Relationship

The relationship variable provided information concerning the existence of links between the organizations. Respondents were asked to indicate whether their organization was linked to other organizations participating in Ciclovía. Response options were “unlinked” (did not work together at all, relationship=0) and “linked” (worked together in some way, relationship=1).

Importance

The importance variable provided information concerning the relevance of the organizations participating in Ciclovía. Respondents were asked about their perception of the importance of the participation of each of the other organizations to which they were linked. Response options were: not important (importance=0), of little importance (importance=1), important (importance=2), very important (importance=3), and extremely important (importance=4).

Integration

The integration variable described the relationship between linked organizations. Respondents were asked to choose the response that best described the current relationship between their organization and each of the other organizations. Response options were: communication (share information only when it is necessary), cooperation (share information and work together when any opportunity arises), collaboration (pursue opportunities to work together, but we do not establish a formal agreement), and partnership (work together as a formal team with specified responsibilities to achieve common goals across multiple projects).

Contact

The contact variable determines the frequency of contact among organizations. Respondents were asked to indicate how often their organization had contact with other organizations. Response options were: yearly (contact=1), quarterly (contact=2), monthly (contact=3), weekly (contact=4), and daily (contact=5).

Leadership

The leadership variable provides information about the leadership of the organizations involved in Ciclovía. Respondents were asked to indicate which organizations could be leaders in the Ciclovía program.

Organizational attributes

Two node attributes were used in the analysis. First, each organization was classified by sector (categorical variable with nine categories), which was determined by considering each organization’s role and type of activity. Second, each organization was classified by the number of years that it had been involved in Ciclovía. Additionally, to analyze the main barriers that make the integration of the organizations in Ciclovía difficult, respondents were asked to indicate which factors are barriers or enablers to working with other organizations.

Analysis

The analysis followed two approaches: first, a visual and descriptive analysis, and second, a stochastic network method using an exponential random graph model (see appendix).7 Analysis was conducted using Pajek, UCINET, GEPHI, and R.

Visual and descriptive analysis

Network visualization and description were performed to: 1) identify how the organizations were linked within the Ciclovía network, 2) identify the role of individual organizations in the Ciclovía network, and 3) recognize subgroups of organizations working together.

The analysis focused on network and individual node properties. The measurements calculated for the sociometric relationships of the network were: density (total number of connections divided by total possible connections), reciprocity (the percentage of correspondence of links in the network), in-degree (number of links that an organization have from others in the network), out-degree (number of links that an organization have to other actors in the network), betweenness (the extent to which an organization was acting as a bridge between other organizations that are not directly connected) and closeness (how close an organization was to all the other organizations in the network) (appendix pp 2–3).29 Additionally, a community detection algorithm was used to detect subgroups of organizations working together in the network (appendix p 3).30

Exponential random graph model (ERGM)

ERGM was conducted to estimate the parameters for each of the predictors of the integration ties between the organizations. ERGM represents a probability distribution of graphs on a fixed node set. The probability of observing a graph is dependent on the configurations of the model.31 In this case, the ERGM model was able to predict the likelihood of integration between the organizations linked to Ciclovía based on structural tendencies (transitivity and heterogeneity) and link and node attributes (appendix pp 4–5).31,32

The model building was developed in four stages. First, we built a null model, which took into account the relationship variable (Model 1). Second, node attributes were added to the model (Model 2). Then, the importance and contact variables of the connected organizations were added to the model (Model 3). Finally, the Model 3 without including the contact variable (Model 4) was assessed. For ERGM, the integration variable was dichotomized as 0=unlinked or communication, and 1=cooperation, collaboration, or partnership. This cutoff point was selected based on the distribution of responses.

Model 1

This model uses a single parameter (relationship) to explain the behavior of integration between two organizations.

Model 2

This model assesses the effects of organizational attributes in integration between organizations.

Model 3

For the construction of this model, two other variables (link attributes) were added to the model attributes: importance and contact. Additionally, three geometrically weighted terms (GWESP, GWDegree, and GWDSP) were included to analyze the network configuration and overcome the problem of model degeneracy.33–36 GWESP (geometrically weighted edgewise shared partner) is a measurement of the transitivity structure of the network. It captures the tendency of organizations that share a tie to form complete triangles with other organizations in the network.33,36 GWDegree (geometrically weighted degree statistic) captures the tendency of organizations with higher degree to form relationships with one another.34,36 GWDSP (geometrically weighted dyad-wise shared partner) is a measurement of the network’s structural equivalence. It captures the tendency of a pair of organizations to share ties with the same sets of partners.33

Model 4

This model used the same attributes and predictors as Model 3 without including the contact variable. Contact variable was excluded due to poor convergence.

RESULTS

Descriptive and visual analysis

The most central organizations in the network were from the Sports and Recreation, Government, and Security sectors. The density of the directed network was 0.23, indicating that approximately one fourth of the possible ties are present. The reciprocity measurement was 23.8%, indicating a low percentage of reciprocal relationships and a high percentage of one-sided relationships between organizations.

According to the survey, 48.5% of the relationships were communication, 23.9% were cooperation, 9.7% were collaboration, and 17.9% were partnerships. Nonetheless, 79.1% of those relationships were reported to be very important or extremely important, while only 2.2% were reported to be not important or of little importance. The average time that organizations have been involved in Ciclovía was 22.3 years (range: 1–35). In addition, the organizations that were perceived to be leaders in Ciclovía, were the District Institute of Recreation and Sports (IDRD, for the Spanish acronym), the Secretariat of Culture, Recreation and Sport (SCRS), City Hall, the Secretariat of Movility (SoM), and the Secretariat of Health (SoH). Specifically, 56% of the nominations were for the IDRD, 24% were for each of the SCRS and City Hall, and 16% were for the SoM and SoH. The rest of the organizations were not nominated.

The in-degree measurement showed that the organizations with the most ties from others in the network were from four sectors: Sports and Recreation (IDRD-node #10 [14]), Security (TP-node #14 [9], and MP-node #13 [9]), Transport and Urban Planning (SoM-node #2 [8]), and Government (City Hall-node #1 [8]) (Figure 1a). The analysis of the out-degree measurement showed that the organizations most related to other organizations were from three sectors: Sports and Recreation (IDRD-node #10 [23] and SCRS-node #9 [23]), Government (City Hall-node #1 [12] and SoG-node #3 [11]), Transport and Urban Planning (SoM-node #2 [11]), and Health (SoH-node #4 [11]) (Figure 1b). The betweenness measurement showed that the organizations from the Sports and Recreation sector (IDRD-node #10 [109.3] and SCRS-node #9 [20.8]) had the highest values, and therefore are the key intermediaries in the network (Figure 1c). The closeness measurement showed that the organizations from the Sports and Recreation sector (IDRD-node #10 [94.1] and SCRS-node #9 [94.1]) were also the most central nodes in the network, that is, the organizations closest to other organizations in the network (Figure 1d).

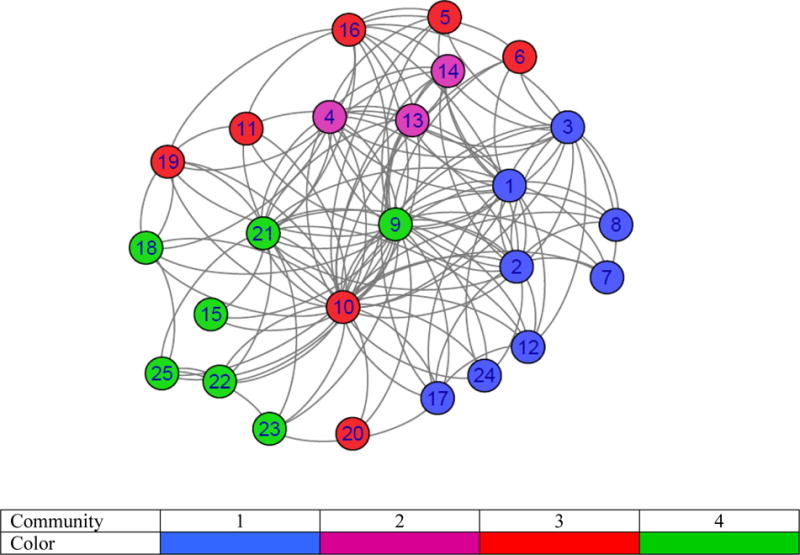

The community detection analysis showed that each of the four communities identified is formed by organizations of different sectors (Figure 2). For example, the organizations of Health sector, Secretariat of Health (SoH) and Ministry of Health (MoH), are in different communities. SoH (node #4) is in the community two with MP (node #13) and TP (node #14). MoH (node #16) is in the community three with SoEdu (node #5), SoP (node #6), IDRD (node #10), Coldeportes (node #11), CDC (node #19), and FONDATT (node #20).

Figure 2.

Network of Ciclovía organized by communities (Modularity)

Of the organizations that responded to the questionnaire, 40.9% reported that there is no factor limiting their ability to work with other organizations, 27.27% indicated that organizational structure/bureaucracy is the main barrier to work with others, 4.54% reported lack of time, 4.54% reported incompatibility of goals or strategies, 4.54% indicated lack of formal agreements, and 18.18% reported no barrier.

Stochastic Modeling

The results of Model 4 show that the variable “years working on Ciclovía” is inversely associated with integration and that importance was positively associated with integration. The log-odds of forming an integration tie decrease by 0.08 for every additional year that the organization participates in the program. The organizations considered most important by others are the most likely to cooperate, collaborate, or form partnerships. Model 4 had the best fit (appendix pp 4–5).

In addition, the following structural predictors of integration were statistically significant: GWOdegree, GWESP, and GWDSP (Table 2). There was a positive tendency for transitivity (GWESP), indicating that organizations tend to form complete triangles or cluster with other organizations. In this network, there was no tendency for organizations with high out-degree (GWOdegree) to cooperate, collaborate, or form partnerships with other organizations that also have high out-degree. The positive value of GWDSP indicates that there is a structural equivalence in the network; that is, a pair of organizations in the network tends to share arcs with the same sets of partners.

Table 2.

Stochastic Models predicting the probability of an integrative tie between two organizations that work to promote the Bogotá’s Ciclovía.

| Coefficient | Model 1: Null model | Model 2: Attribute predictors | Model 3: Attribute and structural predictors | Model 4: Attribute and structural predictors | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logit | Std. Error | Odds | Logit | Std. Error | Odds | Logit | Std. Error | Odds | Logit | Std. Error | Odds | |

| Edges | −2.04*** | 0.13 | 0.11 | −2.58*** | 0.26 | 0.071 | −19.52 | 15990 | 0 | −4.32*** | 1.08 | 0.01 |

| Years working on Ciclovía (nodeicov)† | 0.02* | 0.01 | 0.51 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.5 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.5 | |||

| Years working on Ciclovía (nodeocov)† | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.5 | −0.08*** | 0.02 | 0.48 | −0.08*** | 0.02 | 0.48 | |||

| Sector | −0.13 | 0.45 | 0.47 | −1.04 | 0.74 | 0.26 | −1.57* | 0.78 | 0.17 | |||

| Contact | 21.54 | 15990 | 1 | |||||||||

| Importance | 0.28 | 1.90 | 0.57 | 6.70*** | 1.18 | 0.99 | ||||||

| GWIdegree‡ | −1.02 | 0.87 | 0.27 | −1.39 | 0.80 | 0.19 | ||||||

| GWOdegree‡ | −3.37*** | 0.22 | 0.03 | −3.49*** | 0.20 | 0.03 | ||||||

| GWESP (clustering)§ | 0.29*** | 0.03 | 0.57 | 0.28*** | 0.03 | 0.57 | ||||||

| GWDSP (structural equivalence)‖ | 0.03** | 0.01 | 0.51 | 0.04*** | 0.01 | 0.51 | ||||||

| Model Fit | Likelihood | AIC | BIC | Likelihood | AIC | BIC | Likelihood | AIC | BIC | Likelihood | AIC | BIC |

| −214.1 | 430.21 | 434.61 | −210.03 | 428.05 | 445.6 | −50.09 | 120.2 | 164.2 | −55.48 | 128.96 | 168.54 | |

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001.

Main of the covariate years working on Ciclovía. This term adds a single network statistic to the model equaling the sum of the values for the attribute in the nodes (i) and (j) for all edges (i; j) in the network. For directed networks the model should use nodeicov and nodeocov.

Geometrically weighted degree statistic captures the tendency of organizations with higher degrees to form relations with one another. For directed networks the model should use GWIdegree and GWOdegree.

Geometrically weighted edgewise shared partner captures the tendency for organizations that share a tie to form complete triangles with other organizations in the network.

Geometrically weighted dyad-wise shared partner captures the tendency of a pair of organizations to share ties with the same sets of partners.

DISCUSSION

Ciclovía programs are rapidly expanding worldwide,5,24 and, therefore, information regarding their organizational structure is crucial. This study is the first to provide evidence of the institutional network structure of Bogotá’s Ciclovía, a promising program to promote PA, and it provides a methodology to assess similar PA programs. The analysis showed that Ciclovía is a multisectoral self-organized network with a small number of relationships within the organizations in charge of its management and operation. Most of the relationships in the network are considered important by the institutions even if there is no formal agreement establishing the network as a program policy. The organizations considered most important by others are most likely to cooperate, collaborate, or form partnerships. The centrality of the Sports and Recreation sector shows that it is crucial for mediating the relationships and activities carried out by the other organizations.

Although the network had only 23.8% of reciprocal ties and a density of 0.23, there is always a possible path for the flow of information through any pair of organizations. The structural robustness of networks is determined by removing a critical set of nodes until the network becomes fragmented in several components.37,38 In the context of the Ciclovía network, the Sports and Recreation organizations, which are the most central actors of the network, were removed to analyze the robustness of the network. The resulting network corresponded to a single connected sub-graph, except for the FONDATT organization that in fact was dissolved in 2009. These results suggest that the organizational structure of the Ciclovía network is robust.

Furthermore, there was an inverse relationship between the time that an organization was involved in the Ciclovía network and integration. This result might be explained by the maturity stage of the Ciclovía program18,24 in the organizational life cycle.39 In fact, 76% of the organizations that stated to be involved in the Ciclovia program have been participated for more than 14 years. Those organizations mainly focus on maintaining the program status quo by sharing information only when it is necessary. Newer organizations tend to form ties with other organizations to develop and execute innovative actions in the Ciclovía by working together, pursuing opportunities to work together, or working together as a formal team when an opportunity arises.

The IDRD, which belongs to the Sports and Recreation sector, has a mediator role, which is determinant for the communication flow in the network since it is the most likely organization to have access to all the other organizations involved. This is consistent with the functions of the IDRD within Ciclovía. IDRD is in charge of designing and implementing the Ciclovía. The management from IDRD started in the year 1996 and strengthened the Ciclovía by promoting well-being, PA, and the provision of healthy options for leisure time for the population. In that period, the length of Ciclovia was increased by 50% and the circuit went through 70% of administrative districts. New activities were implemented, such as complementary program of free PA classes.

We also found that the organizations in the network work in multisectoral clusters. In each cluster there are organizations with specific roles and activities that work together on Ciclovía. This is consistent with the multisectoral organization of other Ciclovias in the Americas that involve mainly the sectors of transport, recreation and security and are mainly funded by institutions from the government.18

Despite the fact that Ciclovia is a health promotion program, the analysis highlights that Health is not the most central sector in the network. The specific role of health related organizations included policy recommendations and response to major accidents. Widespread integration of Ciclovía programs into public health may require increasing the engagement of health organizations into the current network. Momentum for such integration is illustrated through the “Healthy Life Style” program, the networks of “Ciclovías of Colombia”, which is expanding Ciclovía programs to all the provinces of Colombia, and the Obesity Law of Colombia in which these programs are recommended as strategies to prevent obesity.

In addition, the network shows a positive tendency for transitivity, meaning that the organizations tend to cooperate, collaborate, or form partnerships in a group, rather than at the individual level. Within the clusters, the relationship between two organizations is often mediated by a third organization, explaining the observable lack of reciprocal ties. This work of the organizations in clusters may explain the network’s low density.

Network analysis is a relatively new approach for PA research. In Latin America, a previous study was performed for the PA networks of Brazil and Colombia.26 In contrast with the Ciclovía network, those networks are formally established by 35 participating institutions in the case of Brazil and 53 institutions in the case of Colombia. The network analysis of Brazil and Colombia showed that those networks have more density than the Ciclovía network and that the importance of organizations is also statistically significant in the integration prediction model. The networks that form the organizations that study and promote PA in Brazil and Colombia were established by government policies. The Ciclovía network, on the other hand, was not formally established; its structure emerged as a self-organized complex system with a history of more than 30 years.

Some limitations in the study are worth noting. We interviewed only one person from each institution who was recommended as the most involved in Ciclovía, assuming that his or her answers accurately represented the whole organization. Therefore, in future studies it is important to survey multiple persons from each organization to assess consistency of the data. Additionally, 12% of the participating organizations did not respond the survey; however, the analysis shows that these organizations were not central and prestigious in the network. In addition, this work only does an initial assessment of network’s integration level using self-reported data as a snapshot of one point in time (2009). To address this, it would be important to periodically track the network integration’s evolution. For this purpose, future studies should include periodically self-reported data from members of the organizations and additional predictors, such as the projects worked on by the two organizations, the results obtained in these projects, and the resources invested. Finally, the high percentage of participants that reported no barriers to work with others could be, in part, due to social desirability in the response.

Ciclovía is a network whose structure emerged as a self-organized complex system in which the organizations tend to cooperate, collaborate, or form partnerships in multisectoral clusters. Most of the relationships in the network are considered important by the institutions even if there is no formal agreement. Ciclovía of Bogota is an example of a program with public health potential formed by organizations of multiple sectors being the most central sector Sports and Recreation. This study provides a framework to understand how Bogotá’s Ciclovía program is structured and what works to develop and support this program to promote PA. Therefore, and considering that Ciclovía programs are expanding worldwide and showing promise as cost beneficial interventions for promoting PA21, the methodology presented could provide a framework for policy makers and practitioners to understand Ciclovía in their local context.

SO WHAT?

What is already known on this topic?

Ciclovía is a multisectoral, community-based mass program to promote PA where most participants are from low and middle socioeconomic status. In a recent work, a cost-benefit analysis of four Ciclovía programs showed that the programs are cost beneficial for promoting PA.

What does this article add?

This study shows that Ciclovía is a network whose structure emerged as a self-organized complex system in which the organizations tend to cooperate, collaborate, or form partnerships in multisectoral clusters.

What are the implications for health promotion practice or research?

To improve global health by increasing population levels of physical activity, programs should develop multisectoral strategies. Despite the fact that Ciclovia is a health promotion program, in this network health is not the most central sector. Widespread integration of Ciclovía into public health may require increasing the engagement of health organizations into the current network. This study provides a methodology for policy makers and practitioners to understand the structure of similar organizational networks within their local context.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. 2008 Available at: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/2004_report_update/en/index.html. Date accessed 2012 jun 12.

- 2.Abegunde DO, Mathers CD, Adam T, Ortegon M, Strong K. The burden and costs of chronic diseases in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet. 2007;370(9603):1929–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61696-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee I-M, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. The Lancet. 2012;380(9838):219–229. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heath G, Parra DC, Sarmiento OL, et al. Evidence-based physicalactivity intervention: lessons from around the globe. The Lancet. 2012;380(9838):272–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60816-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pratt M, Sarmiento OL, Montes F, et al. The implications of megatrends in information and communication technology and transportation for changes in global physical activity. The Lancet. 2012;380(9838):282–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60736-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roussos ST, Fawcett SB. A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving community health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21:369–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luke DA, Harris JK. Network analysis in public health: history, methods, and applications. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:69–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luke DA, Stamatakis KA. Systems science methods in public health: dynamics, networks, and agents. Annu Rev Public Health. 2012;33:357–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Becker T, Leese M, McCrone P, et al. Impact of community mental health services on users’ social networks. PRiSM Psychosis Study. 7. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:404–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.5.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakao K, Milazzo-Sayre LJ, Rosenstein MJ, Manderscheid RW. Referral patterns to and from inpatient psychiatric services: a social network approach. Am J Public Health. 1986;76(7):755–60. doi: 10.2105/ajph.76.7.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tausig M. Detecting «cracks» in mental health service systems: application of network analytic techniques. Am J Community Psychol. 1987;15(3):337–51. doi: 10.1007/BF00922702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mulroy EA. Building a neighborhood network: interorganizational collaboration to prevent child abuse and neglect. Soc Work. 1997;42(3):255–64. doi: 10.1093/sw/42.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaluzny AD, Zuckerman HS, Rabiner DJ. Interorganizational factors affecting the delivery of primary care to older Americans. Health Serv Res. 1998;33(2 Pt Ii):381–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krauss M, Mueller N, Luke D. Interorganizational relationships within state tobacco control networks: a social network analysis. Prev Chronic Dis. 2004;1(4):A08. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramanadhan S, Salhi C, Achille E, et al. Addressing cancer disparities via community network mobilization and intersectoral partnerships: a social network analysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e32130. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Provan KG, Harvey J, de Zapien JG. Network structure and attitudes toward collaboration in a community partnership for diabetes control on the US-Mexican border. J Health Organ Manag. 2005;19(6):504–18. doi: 10.1108/14777260510629706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchthal OV, Taniguchi N, Iskandar L, Maddock J. Assessing state-level active living promotion using network analysis. J Phys Act Health. 2013;10(1):19–32. doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarmiento O, Torres A, Jacoby E, et al. The Ciclovía-Recreativa: A mass-recreational program with public health potential. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(Suppl 2):S163–180. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.s2.s163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoehner CM, Soares J, Parra Perez D, et al. Physical activity interventions in Latin America: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(3):224–33. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torres A, Sarmiento OL, Zarama R. Ciclovia and Cicloruta programs: promising interventions to promote physical activity and social capital in Bogotá. Am J Public Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301142. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montes F, Sarmiento OL, Zarama R, et al. Do health benefits outweigh the costs of mass recreational programs? An economic analysis of four Ciclovía programs. J Urban Health. 2012;89(1):153–70. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9628-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The World Bank. Acting now to reverse the course. The World Bank. Human Development Network; 2011. The growing danger of Non-Communicable Diseases. [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Streets Plan Collaborative, The Alliance of Biking and Walking. The Open Streets Guide. 2012;1 Available at: http://openstreetsproject.org/. Accessed July 20, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Díaz del Castillo A, Sarmiento OL, Reis RS, Brownson RC. Translating evidence to policy: urban interventions and physical activity promotion in Bogotá, Colombia and Curitiba, Brazil. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(2):350–60. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0038-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brownson RC, Parra DC, Dauti M, et al. Assembling the puzzle for promoting physical activity in Brazil: a social network analysis. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(Suppl 2):S242–252. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.s2.s242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parra DC, Dauti M, Harris JK, et al. How does network structure affect partnerships for promoting physical activity? Evidence from Brazil and Colombia. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(9):1365–70. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris JK, Luke DA, Burke RC, Mueller NB. Seeing the forest and the trees: using network analysis to develop an organizational blueprint of state tobacco control systems. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(11):1669–78. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slonim AB, Callaghan C, Daily L, et al. Recommendations for Integration of Chronic Disease Programs: Are Your Programs Linked? Prev Chronic Dis. 2007;4(2):A34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wasserman S, Faust K. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. 1. Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blondel VD, Guillaume J-L, Lambiotte R, Lefebvre E. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment. 2008;10:P10008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robins G, Snijders T, Wang P, Handcock M, Pattison P. Recent developments in exponential random graph (p) models for social networks. Soc Networks. 2007;29(2):192–215. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robins G, Pattison P, Kalish Y, Lusher D. An introduction to exponential random graph (p*) models for social networks. Soc Networks. 2007;29(2):173–91. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hunter DR, Goodreau SM, Handcock MS. Goodness of Fit of Social Network Models. J Am Stat Assoc. 2008;103(481):248–58. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goodreau SM. Advances in exponential random graph (p*) models applied to a large social network. Soc Networks. 2007;29(2):231–48. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunter DR, Handcock MS, Butts CT, Goodreau SM, Morris M. ergm: A Package to Fit, Simulate and Diagnose Exponential-Family Models for Networks. J Stat Softw. 2008;24(3):1–29. doi: 10.18637/jss.v024.i03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Duijn MAJ, Gile KJ, Handcock MS. A framework for the comparison of maximum pseudo-likelihood and maximum likelihood estimation of exponential family random graph models. Soc Networks. 2009;31(1):52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen R, Havlin S. Complex Networks: Structure, Robustness and Function. Cambridge University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barrat A, Barthelemy M, Vespignani A. Dynamical processes on complex networks. Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Daft J, Willmott H. Organization theory and design. South-Western, Cengage Learning; 2010. [Google Scholar]