Abstract

The mu1 opioid receptor gene, OPRM1, has long been a high-priority candidate for human genetic studies of addiction. Because of its potential functional significance, the non-synonymous variant rs1799971 (A118G, Asn40Asp) in OPRM1 has been extensively studied, yet its role in addiction has remained unclear, with conflicting association findings. To resolve the question of what effect, if any, rs1799971 has on substance dependence risk, we conducted collaborative meta-analyses of 25 datasets with over 28,000 European-ancestry subjects. We investigated non-specific risk for “general” substance dependence, comparing cases dependent on any substance to controls who were non-dependent on all assessed substances. We also examined five specific substance dependence diagnoses: DSM-IV alcohol, opioid, cannabis, and cocaine dependence, and nicotine dependence defined by the proxy of heavy/light smoking (cigarettes-per-day > 20 versus ≤ 10). The G allele showed a modest protective effect on general substance dependence (OR = 0.90, 95% C.I. [0.83–0.97], p-value = 0.0095, N = 16,908). We observed similar effects for each individual substance, although these were not statistically significant, likely because of reduced sample sizes. We conclude that rs1799971 contributes to mechanisms of addiction liability that are shared across different addictive substances. This project highlights the benefits of examining addictive behaviors collectively and the power of collaborative data sharing and meta-analyses.

Keywords: Addiction, substance dependence, OPRM1, opioid receptor, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), genetic association

1. INTRODUCTION

The mu opioid receptors are part of a family of G protein-coupled receptors that are expressed in the brain and bind endogenous and exogenous opioids. The mu1 opioid receptor gene (OPRM1) has been one of the most studied genes in psychoactive substance research. It is a receptor for opioid analgesic agents and is involved in reward and analgesic pathways (Kreek and Koob 1998). The non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs1799971 (A118G) in exon 1 of OPRM1 causes an asparagine to aspartic acid substitution at the fortieth amino acid residue (Asn40Asp). The G (Asp) allele is the minor allele across multiple human populations, with frequencies ranging from 4% in African-American samples to ~16% in European-ancestry samples to over 40% in some Asian samples (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/snp_ref.cgi?rs=1799971). Multiple studies have examined the functional effects of this amino acid change on expression levels and receptor properties such as binding affinity and signaling (Befort et al. 2001; Beyer et al. 2004; Bond et al. 1998; Deb et al. 2010; Mague and Blendy 2010; Mague et al. 2009; Ray et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2005).

Because of its potential functional significance, many human genetic studies of substance dependence have targeted rs1799971. However, the role, if any, of rs1799971 in substance dependence remains unclear (Crist and Berrettini 2013; Levran et al. 2012; Mague and Blendy 2010). In studies of opioid dependence, results have been mixed, with the minor (G) allele reported to have no effect in some studies (Crowley et al. 2003; Levran et al. 2008; Nelson et al. 2014; Nikolov et al. 2011) and to decrease risk in others (Bond et al. 1998; Tan et al. 2003). Similarly, analyses of alcohol dependence have reported increased risk (Bart et al. 2005; Kim et al. 2004), no effect (Bergen et al. 1997; Rouvinen-Lagerstrom et al. 2013; Sander et al. 1998; Xuei et al. 2007), and decreased risk (Schinka et al. 2002; Town et al. 1999) for this allele. Analyses of rs1799971 with other addictive substances also show no consensus (Clarke et al. 2013; Crist and Berrettini 2013; Franke et al. 2001; Gelernter et al. 1999; Hardin et al. 2009; Munafo et al. 2013).

Literature-based meta-analyses have evaluated the association of rs1799971 with substance dependence (Arias et al. 2006), opioid dependence (Coller et al. 2009; Glatt et al. 2007; Haerian and Haerian 2013), and alcohol dependence (Chen et al. 2012a). Three of these meta-analyses reported no association (Arias et al. 2006; Coller et al. 2009; Glatt et al. 2007), while among Asian samples the G allele was reported to increase risk for alcohol (Chen et al. 2012a) and opioid dependence (Haerian and Haerian 2013). Although these meta-analyses attained large samples by combining published information, they were subject to heterogeneity from multiple sources, including differing phenotypes, ascertainment schemes, and statistical analysis models across the meta-analyzed publications.

To clarify the effect of rs1799971 on substance dependence risk, we conducted collaborative meta-analyses based on new analyses of multiple datasets. Our data-driven approach moves beyond the limitations of literature-based meta-analyses by (1) defining consistent phenotypes across studies, (2) performing new, uniform analyses across datasets as in our previous meta-analyses (Chen et al. 2012b; Hartz et al. 2012; Saccone et al. 2010), and (3) inviting investigators to contribute analyses from established studies with relevant phenotype and genotype data, irrespective of prior publication on rs1799971.

2. METHODS

2.1. Samples and Study design

Twenty-five datasets contributed a starting sample of 28,689 study participants of European ancestry. Invitations to participate were sent to all studies in the NIDA Genetics Consortium, which NIDA formed to facilitate collaboration among investigators in addiction genetics, as documented by the NIDA Center for Genetic Studies (https://nidagenetics.org/studies). We extended invitations to additional studies suggested by consortium members as likely to have relevant data, and to collaborators on a previous meta-analysis of smoking quantity and lung disease (Saccone et al. 2010). NIDA further advertised the opportunity to participate in this meta-analysis project with a web announcement at http://www.drugabuse.gov/researchers/research-resources/genetics-research-resources/collaborative-opportunities-genetics-research. Dataset inclusion criteria were: (1) rs1799971 must have been genotyped, and (2) at least one of these five phenotypes must have been assessed: DSM-IV defined alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, or opioid dependence, or categorized cigarettes per day (CPD) (0–10, 11–20, 21–30, and 31+ CPD).

Study participants with a history of abstinence from alcohol (never drank) were excluded prior to all analyses, so that included participants satisfied a minimum exposure to alcohol. For the main analyses, we filtered out study participants if they had no known substance dependence and were also under the age of 25. Thus, we included non-dependent (control) participants only if they were old enough to have passed through the period of highest risk, so as to reduce phenotypic misclassification. For each dataset, Table 1 gives demographic characteristics, the allele frequency of rs1799971, and key publications. Supplementary text S1 provides additional details for each dataset, including study recruitment, genotyping methods, and data quality control.

Table 1.

Study descriptions: sample sizes, G (minor) allele frequencies (overall, in general dependence cases, in general dependence controls), proportions of male participants, and age distribution (minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, and maximum) of each study.

| Study | Total N |

G-allele- freq |

Case G- allele- freq |

Control G- allele- freq |

proport- male |

age min |

age_q1 | age_med | age_q3 | age_max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BG a | 3999 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.83 | 18 | 25 | 28 | 30 | 58 |

| CADD b | 409 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.56 | 12 | 21 | 28 | 47 | 72 |

| CATS c | 1748 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.57 | 18 | 29 | 36 | 43 | 65 |

| CEDAR-SADS d | 747 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.35 | 14 | 18 | 37 | 42 | 65 |

| Cinciripini e | 627 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.48 | 18 | 33 | 42 | 50 | 74 |

| COGA f | 1024 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.46 | 18 | 36 | 43 | 51 | 77 |

| COGEND g | 2024 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.61 | 25 | 32 | 37 | 41 | 65 |

| Finnish Health 2000 h | 1025 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.8 | 30 | 37 | 46 | 54 | 87 |

| FSCD i | 558 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.5 | 18 | 25 | 34 | 40 | 54 |

| FT12 j | 617 | 0.22 | 0.48 | 20 | 22 | 22 | 23 | 27 | ||

| GADD k | 281 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.57 | 12 | 15 | 16 | 19 | 61 |

| GESGA l | 3501 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.65 | 18 | 39 | 47 | 56 | 84 |

| Kreek m | 750 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.59 | 17 | 31 | 43 | 52 | 82 |

| MCTFR-Parents n | 3842 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.46 | 30 | 43 | 46 | 50 | 72 |

| NAG-AUS o | 1281 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.59 | 18 | 36 | 43 | 50 | 82 |

| NAG-FIN p | 879 | 0.21 | 0.7 | 42 | 52 | 55 | 58 | 77 | ||

| NYS q | 552 | 0.1 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.49 | 35 | 37 | 39 | 41 | 44 |

| OYSUP r | 357 | 0.13 | 0.5 | 20 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 23 | ||

| PAGES s | 409 | 0.11 | 0.68 | 17 | 27 | 37 | 45 | 68 | ||

| PiP t | 809 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.48 | 18 | 35 | 43 | 53 | 79 |

| ROMA u | 732 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.38 | 0.83 | 18 | 25 | 28 | 32 | 53 |

| SMOFAM v | 166 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.63 | 26 | 27 | 29 | 30 | 62 |

| Utah w | 463 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.59 | 25 | 54 | 61 | 67 | 86 |

| VA-Twin x | 672 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.32 | 21 | 30 | 38 | 46 | 58 |

| Yale-Penn y | 1217 | 0.12 | 0.41 | 16 | 30 | 39 | 46 | 72 | ||

| Total | 28689 | (0.10–0.22) | (0.32–0.83) | (12–42) | (15–54) | (16–61) | (19–67) | (23–87) |

2.2. Phenotypes

We analyzed six primary dichotomous phenotypes: a “general” substance dependence diagnosis (lifetime dependence on any of five substances: alcohol, nicotine, cannabis, cocaine, and opioids), plus the corresponding five individual substance-specific lifetime dependence diagnoses. General substance dependence controls were required to be non-dependent on all substances assessed in that dataset; not all studies assessed all five substances. For each substance, individuals who did not meet dependence criteria were classified as non-dependent; abuse criteria were not considered. These phenotypes allowed us to examine the general (nonspecific) liability to substance dependence and compare non-specific and substance-specific associations.

DSM-IV criteria were used to define dependent cases for alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, and opioids. For nicotine dependence, we defined the proxy of heavy smoking cases (CPD > 20) and light smoking controls (CPD ≤ 10) for current and former smokers, based on CPD when they were smoking; if multiple measurements were available the maximum value was used. Heavy versus light CPD is more commonly measured than nicotine dependence and has been an informative proxy for nicotine dependence in large meta-analyses (Chen et al. 2012b; Hartz et al. 2012; Saccone et al. 2010); smokers meeting this threshold strongly overlap with nicotine dependent smokers. Because CPD does not account for dependence items such as withdrawal (Lessov et al. 2004), secondary analyses examined the effect of redefining general dependence using standard definitions of nicotine dependence (Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (Heatherton et al. 1991) and DSM-IV), in the subset of studies for which these were available.

In addition to filtering out subjects who did not meet minimum exposure to alcohol, we also defined analysis variables for exposure to each of the other four substances. For cannabis, cocaine, and opioids, the exposure threshold was “at least one lifetime use.” For nicotine, we used “at least 100 cigarettes smoked lifetime,” a commonly used threshold to define smoking exposure in epidemiological studies.

Table 2 shows dataset-specific counts for cases, controls, and exposed controls. Individuals dependent on multiple substances are counted and analyzed in the corresponding multiple categories.

Table 2.

Numbers of cases, total controls, and controls with exposure to each substance. These numbers were based on a filtered sample that removed participants not exposed to alcohol, and participants who are less than 25 years of age and have with no dependence to any assessed substances. NA indicates that the substance was not assessed in the study.

| Alcohol | Cigarettes Per Day (CPD) | Cannabis | Cocaine | Opioid | General Substance Dependence |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Datasets | Cases | Total Controls |

Heavy Smokers |

Total Controls |

Exposed Controls |

Cases | Total Controls |

Exposed Controls |

Cases | Total Controls |

Exposed Controls |

Cases | Total Controls |

Exposed Controls |

Cases | Controls |

| BG | 277 | 1278 | 1449 | 4 | 4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 948 | 3 |

| CADD | 93 | 264 | 54 | 109 | 57 | 72 | 285 | 218 | 35 | 306 | 141 | 6 | 351 | 106 | 161 | 72 |

| CATS | 651 | 1032 | NA | NA | NA | 857 | 831 | 765 | 416 | 1272 | 875 | 1259 | 429 | 102 | 1444 | 209 |

| CEDAR-SADS | 179 | 562 | NA | NA | NA | 255 | 486 | 338 | 86 | 655 | 263 | 114 | 627 | 418 | 342 | 399 |

| Cinciripini | NA | NA | 253 | 34 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 253 | 34 |

| COGA | 612 | 410 | 242 | 483 | 140 | 196 | 823 | 475 | 224 | 795 | 204 | 86 | 933 | 193 | 648 | 318 |

| COGEND | 463 | 1529 | 584 | 935 | 923 | 192 | 1808 | 1543 | 132 | 1871 | 560 | 34 | 1970 | 191 | 918 | 734 |

|

Finnish Health 2000 |

417 | 512 | 89 | 463 | 180 | 3 | 1011 | 0 | 0 | 1014 | 0 | 2 | 1012 | 0 | 453 | 283 |

| FSCD | 280 | 230 | 124 | 276 | 58 | 170 | 340 | 213 | 237 | 273 | 55 | 81 | 429 | 100 | 309 | 193 |

| FT12 | 93 | 470 | 198 | 15 | 15 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 251 | 0 |

| GADD | 43 | 110 | 11 | 57 | NA | 45 | 108 | 78 | 9 | 144 | 29 | NA | 153 | 35 | 75 | 20 |

| GESGA | 1333 | 1933 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1280 | 1926 |

| Kreek | 42 | 684 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 82 | 644 | 41 | 528 | 198 | NA | 527 | 198 |

| MCTFR-Parents | 226 | 2504 | NA | NA | NA | 93 | 2637 | 1637 | 37 | 2695 | 452 | 12 | 2722 | 125 | 283 | 2442 |

| NAG-AUS | 359 | 972 | 737 | 594 | 102 | 79 | 1249 | 694 | 5 | 1322 | 74 | 17 | 1310 | 137 | 766 | 507 |

| NAG-FIN | 221 | 513 | 354 | 115 | 115 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 450 | 101 |

| NYS | 65 | 466 | 71 | 135 | 63 | 25 | 508 | 368 | 26 | 507 | 157 | 1 | 532 | 86 | 135 | 125 |

| OYSUP | All participants were under 25 years of age | |||||||||||||||

| PAGES | 64 | 335 | 132 | 83 | 40 | 77 | 320 | 160 | 7 | 391 | 67 | 8 | 390 | 30 | 210 | 61 |

| PiP | NA | NA | 347 | 54 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 332 | 52 |

| ROMA | 18 | 240 | 209 | 7 | 6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 177 | 4 |

| SMOFAM | NA | NA | 20 | 67 | 34 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 20 | 67 |

| Utah | 112 | 283 | 235 | 60 | 60 | 36 | 359 | 88 | 16 | 379 | 34 | 9 | 386 | 9 | 272 | 35 |

| VA-Twin | NA | NA | 193 | 70 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 186 | 68 |

| Yale-Penn | 799 | 208 | 1094 | 113 | NA | 397 | 566 | 500 | 911 | 259 | 167 | 703 | 478 | 214 | 1208 | 3 |

| Total | 6347 | 14535 | 6396 | 3674 | 1797 | 2497 | 11331 | 7077 | 2223 | 12527 | 3119 | 2860 | 11920 | 1746 | 11648 | 7834 |

2.3. SNP for analysis

We required rs1799971 to be genotyped in each dataset. For analyses, we coded rs1799971 as the number of copies of the G (minor) allele.

2.4. Statistical analyses and meta-analysis

We conducted six correlated discovery tests corresponding to the six primary phenotypes: the general substance dependence diagnosis and the five specific substance dependence diagnoses. To limit the number of tests, we focused on testing for a main effect of rs1799971 on these outcomes. All discovery analyses filtered out study participants under the age of 25 with no known substance dependence to ensure that controls had passed the typical age of dependence onset; cases are dependent and thus have had sufficient exposure regardless of age. Additional interpretive tests examined the robustness and consistency of discovery test results, and included analyses without age filtering for comparison.

To ensure uniform analyses across datasets, the coordinating site at Washington University developed analysis scripts in SAS® and R. Scripts were distributed to collaborating sites, which then analyzed their datasets locally. Results were returned to the coordinating site for meta-analyses. We used standard inverse-variance-weighted meta-analysis as implemented in the rmeta package in R (Lumley; R Development Core Team 2012). Additionally, to be included in the meta-analysis of a given model, each dataset was required to have at least five cases and five controls available. This requirement was intended to reduce noise when some subgroups became very small after phenotypic filtering. All samples included for general dependence in fact met a higher threshold of at least 20 cases and 20 controls. We report fixed effect estimates together with Cochran’s Q and I2 to evaluate heterogeneity for each meta-analyzed model. No significant heterogeneity was observed among the studies analyzed (p-value for Q > 0.05, Table S1 and Tables 3 and 4). Correspondingly, Q values were close to the respective degrees of freedom (number of studies) and I2 values were small with no values greater than 26% (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 3.

Summary of the effect of rs1799971 on general substance dependence.

| Model | Cases | Controls | Cochrane’s Q | Q-Pvalue | Odds Ratio | L95%-U95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gen-Dep = age sex rs1799971 | 9064 | 7844 | 20.13 | 0.387 | 0.90 | 0.83–0.97 |

| Alcohol = age sex rs1799971 | 5086 | 7623 | 12.08 | 0.672 | 0.92 | 0.83–1.01 |

| Nicotine = age sex rs1799971 | 3358 | 2670 | 16.84 | 0.265 | 0.93 | 0.83–1.05 |

| Cannabis = age sex rs1799971 | 2077 | 5115 | 7.63 | 0.746 | 0.83 | 0.71–0.98 |

| Cocaine = age sex rs1799971 | 1307 | 5313 | 7.68 | 0.809 | 0.87 | 0.73–1.04 |

| Opioid = age sex rs1799971 | 2139 | 5168 | 7.87 | 0.641 | 0.84 | 0.70–1.00 |

Model column shows what outcome phenotype was tested for each model. Gen-Dep denotes general substance dependence. Each substance denotes the subsets of general substance dependence that were tested in interpretative phase of the analysis. All effects shows are fixed effect estimates. Controls were filtered for age and exposure to alcohol.

Table 4.

Summary of the effect of rs1799971 on specific substance dependence diagnoses in 9 studies that assessed all five substance dependence diagnoses and exposures.

| Ordinal Logistic Regression Results | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substance | Cases | Controls | Cochrane’s Q | Q-Pvalue | Odds Ratio | L95%-U95% | OR-Pvalue |

| Alcohol | 2031 | 3361 | 8.90 | 0.351 | 0.90 | 0.76–1.06 | 0.218 |

| Nicotine | 2718 | 2674 | 7.78 | 0.455 | 0.89 | 0.74–1.07 | 0.216 |

| Cannabis | 839 | 4553 | 10.76 | 0.216 | 0.91 | 0.73–1.14 | 0.420 |

| Cocaine | 992 | 4085 | 0.86 | 0.990 | 0.92 | 0.69–1.24 | 0.593 |

| Opioid | 607 | 4274 | 3.12 | 0.682 | 0.91 | 0.65–1.27 | 0.577 |

| Traditional Logistic Regression Results (Dependence as outcome variable) | |||||||

| Alcohol | 2051 | 3430 | 10.66 | 0.222 | 0.88 | 0.76–1.02 | 0.974 |

| Nicotine | 2066 | 1412 | 8.69 | 0.276 | 0.91 | 0.76–1.08 | 0.267 |

| Cannabis | 861 | 3036 | 9.08 | 0.336 | 0.90 | 0.74–1.09 | 0.283 |

| Cocaine | 1011 | 899 | 0.85 | 0.997 | 0.91 | 0.70–1.19 | 0.492 |

| Opioid | 600 | 577 | 2.31 | 0.679 | 0.91 | 0.67–1.24 | 0.547 |

Substance column shows the tested outcome phenotype. All effects shows are fixed effect estimates. In the traditional logistic regression results, controls were required to be exposed each tested substance, in addition to meeting the previously applied filters for age and exposure to alcohol.

2.5. General substance dependence analyses

Logistic regression was used to estimate the effect of rs1799971 on general substance dependence with covariates for sex and age. Of the 25 available datasets, 20 had at least five cases (dependent at least one of the five substances) and five controls (no known substance dependence diagnoses and exposed to alcohol) for analysis of general substance dependence.

Our interpretive tests examined the robustness of the general substance dependence results and compared them to substance-specific effects. Specifically, to assess the influence of each individual dataset, each of the 20 contributing datasets was, in turn, left out of the meta-analysis. In this leave-one-out test, observing consistency of summary odds ratios would suggest that it is unlikely that the overall meta-analysis result is primarily due to a single study. Also, we meta-analyzed only studies that had assessed all five substances to examine consistency of results; the general dependence controls in these studies were assessed for all five substances and thus more homogenous. Finally, to compare the effect of rs1799971 on general substance dependence liability with its effect on the constituent substance-specific diagnoses, we tested for association using individuals dependent on each specific substance as cases compared to the same controls used in the general dependence analysis (non-dependent on all assessed substances).

2.6. Specific substance dependence analyses

To test the association of rs1799971 with each specific dependence diagnoses while accounting for the remaining diagnoses, our primary analysis used ordinal logistic regression with additively coded rs1799971 as the dependent variable and the five dependence diagnoses, four exposures, sex, and age as explanatory variables. This model simultaneously estimates association of rs1799971 with each substance while accounting for co-morbidity (Grucza et al. 2008). This analysis used only the datasets that had all five substance dependence diagnoses and all four exposure variables because the model required that there be no missing variables.

To interpret and examine the robustness of these results, we evaluated traditional logistic regression models on the same datasets, also accounting for co-morbidity: each specific substance dependence was tested as the outcome, with log-additively coded rs1799971, age, sex, and the remaining specific substance dependence diagnoses as explanatory variables. Here, cases were dependent on a given substance, and controls were exposed but not dependent on that substance regardless of diagnoses for the remaining four substances. Additionally, to test equivalence of regression coefficients from ordinal regression analyses of individual substances, we conducted a two sample t-test assuming unequal variance.

To examine whether substance-specific results remained consistent with a larger number of datasets, we used all datasets that had assessed each substance for additional interpretive tests, with the dependence diagnosis as outcome and additively coded rs1799971, sex, and age as explanatory variables.

2.7. Multiple test correction

To estimate the effective number of independent tests corresponding to the six correlated discovery tests, we used matSpD [http://gump.qimr.edu.au/general/daleN/matSpD/], which accounts for correlations among phenotypes (Cheverud 2001; Li and Ji 2005; Nyholt 2004). Using Pearson correlations among the five dependence diagnoses from the studies with all five phenotypes assessed (see Table S3), plus one additional test for general substance dependence, we obtained a conservative estimate of 5.1218 independent tests, corresponding to a Bonferroni-corrected p-value threshold of α′ = 9.76 × 10−3 for statistical significance.

3. RESULTS

3.1. The G (Asp) allele of rs1799971 shows a modest protective effect on general substance dependence

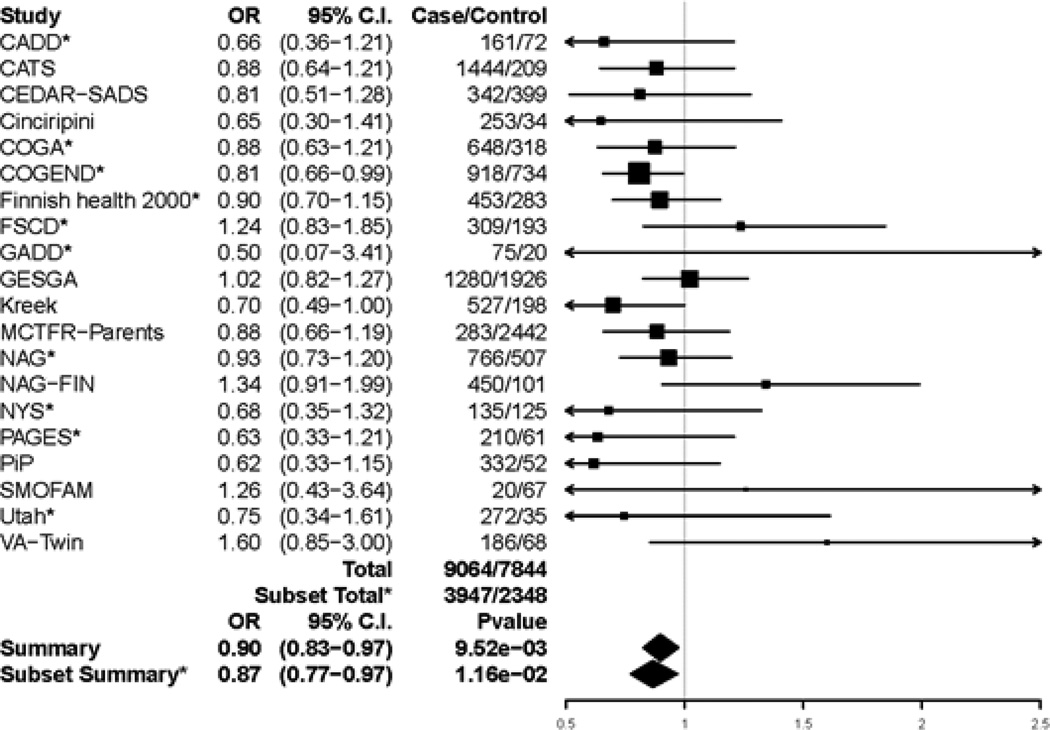

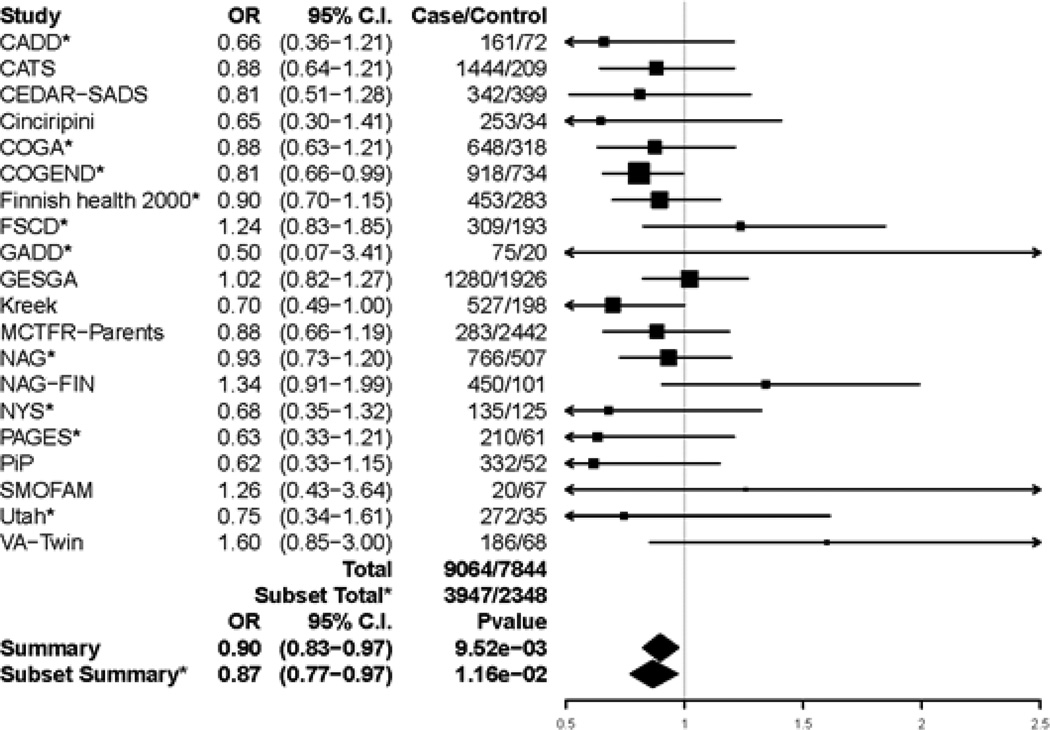

We observed a significant association between rs1799971 and general substance dependence (Figure 1). Based on 9064 cases and 7844 age-filtered controls from 20 datasets, the G allele showed a modest protective effect (OR = 0.90, 95% C.I. [0.83–0.97], p-value = 9.52 × 10−3, N = 16,908); 15 of the 20 studies showed a protective direction of the G allele. Heterogeneity variance was not statistically significant (Q=20.13, p-value = 0.39). A secondary analysis that did not require controls to be over 25 years old yielded a similar odds ratio (OR = 0.90, 95% C.I. (0.84–0.98), N = 17,918), but was not statistically significant after multiple correction in this larger sample (p-value = 1.06×10−2), consistent with our hypothesis that it is important for controls to be past the typical age of risk.

Figure 1.

Forest plot of general substance dependence and rs1799971 across studies that had at least 5 cases and 5 controls. Summary odds ratio, 95% Confidence Interval, and p-values are based on fixed effect meta-analysis. *indicates the subset of 10 studies that had all five specific substance dependence diagnoses, examined in secondary analyses to confirm consistency of results. Estimated heterogeneity variance was Q = 20.13 with a p-value of 0.387 among all 20 studies and Q = 6.49 with a p-value of 0.69 among the subset of 10 studies.

Leave-one-out test of robustness yielded odds ratio estimates ranging from 0.88 to 0.92, with none of the 20 iterations showing significant heterogeneity. This tight range of ORs centered on the overall odds ratio indicates that our finding was not driven by a single dataset. Only a few of the individual iterations showed significant association (e.g. 4 of 20 when using α′ =9.76×10−3 as the significance threshold), likely due to the reduced sample size.

To reduce potential heterogeneity among the general dependence controls, we meta-analyzed the 10 datasets that had all five substance-specific dependence diagnoses and at least 5 cases and 5 controls. For these 10 datasets (3947 cases and 2348 controls), the summary odds ratio was 0.87 (p-value = 0.01), very similar to the discovery result based on 20 studies.

Additionally, to aid interpretation, we compared the cases for each specific substance to the general dependence controls. We found that the G allele of rs1799971 was consistently protective (odds ratio of 0.83 to 0.93) across all five substances (Table 3), consistent with the interpretation that this allele is a non-substance-specific protective factor.

To further confirm robustness, we examined the effect of redefining general dependence using alternative definitions for nicotine dependence, namely the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) (case ≥ 4, control ≤ 1; 13 studies, N = 8,481) or DSM-IV nicotine dependence (14 studies, N = 11,711), in place of our CPD-based heavy/light phenotype (20 studies, N = 16,908). Analyses of these smaller samples gave similar protective odds ratios for general dependence, though results were not statistically significant: OR = 0.91, 95% C.I. (0.81–1.02) for FTND and OR = 0.94, 95% C.I. (0.85–1.03) for DSM-IV nicotine dependence.

3.2. For each substance-specific dependence, the G allele of rs1799971 is similarly protective but non-significant

In our primary test of rs1799971 genotype as the dependent variable on the 9 datasets that had assessed all five substance dependence diagnoses and exposures, we obtained odds ratios that ranged from 0.89 (nicotine dependence) to 0.92 (cocaine dependence). The odds ratio for each specific substance showed the same protective direction as that for general substance dependence, though none was statistically significant in these smaller samples (Table 4). Also, odds ratios for specific substances did not differ significantly from each other (Table S2), suggesting consistency across substances.

We also examined traditional logistic regression in these 9 datasets. Each substance dependence diagnosis was examined as the outcome (cases dependent on that substance and controls required to be non-dependent but exposed to that substance), with rs1799971 as the predictor and the remaining diagnoses as covariates. Results were similar to those from our ordinal logistic model (Table 4, bottom half). Finally, analyzing all available datasets for these same case/control outcomes (cases dependent on each specific substance, controls non-dependent and exposed to that substance) also showed protective, but non-significant, odds ratios consistent with those seen in the datasets that assessed all dependence diagnoses and exposures (Supplementary Figures S1–S5).

4. DISCUSSION

This project, the first collaborative genetic meta-analysis to investigate specific and general liability for these substance dependence diagnoses, has demonstrated that the G allele of rs1799971 has a modest protective effect on general substance dependence liability (OR = 0.90, 95% C.I. (0.83–0.97), p-value =9.52 × 10−3) in samples of European ancestry. This is the first meta-analysis to show that this non-synonymous variant, which has been heavily studied for functional effects, is significantly associated in European ancestry samples with liability to substance dependence. The small but significant effect size of rs1799971 suggests that variability in previous association reports may be due in part to sampling variation. This collaborative meta-analysis benefited from the opportunity to define uniform phenotypes across studies, perform coordinated, de novo analyses to test our hypotheses, and include existing datasets that have not yet focused on the question of rs1799971 and addiction.

The protective effect of this allele on substance dependence liability appears to be non-specific: it is not driven primarily by dependence on any particular substance. For each substance-specific subset of cases compared to the general dependence controls, we observed a protective effect of similar size to that observed for general dependence. Additional substance-specific analyses similarly showed consistent protective effects of the G allele. These substance-specific odds ratios were not statistically significant, but this may have been largely due to reduced sample size and power.

These findings indicate that rs1799971 in OPRM1 may contribute to mechanisms of addiction liability that are shared across different addictive substances, consistent with the high genetic correlation between the traits, high co-morbidity, and with prior studies showing that both substance-specific and non-specific genetic effects on addiction liability can be expected (Bierut et al. 1998; Kendler et al. 2007; Merikangas et al. 1998; Swan et al. 1997; Tsuang et al. 1998; Vanyukov et al. 2012; Vanyukov et al. 2003). Rs1799971 is now one of the few examples of a genetic factor that demonstrates a similar, general effect across multiple substances, albeit of modest magnitude. In this sense, our study is similar to a genome-wide association study of multiple psychiatric disorders that identified variants having a common, cross-disorder genetic effect on five major psychiatric diseases (Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium 2013). Both studies underscore the value of investigating the genetics of general liability underlying related diseases. Genetic studies of addiction would therefore benefit from including measures pertaining to multiple substances that can then be analyzed collectively. Indeed, a very recent genome-wide study of general substance dependence liability using four of the five substances studied here (alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, opioids) reported novel associations (Wetherill et al. 2015), further supporting the potential benefits.

Our results are compatible with negative results from prior genome-wide meta-analyses of cigarettes-per-day (Liu et al. 2010; The Tobacco and Genetics Consortium 2010; Thorgeirsson et al. 2010). Our hypothesis-driven analyses of a single SNP translate to a study-wide required significance threshold of 9.76×10−3. This led to statistically significant evidence for a modest effect (OR=0.90) of rs1799971 on general substance dependence liability, in N=16,908 subjects (Table 3). The three genome-wide smoking consortia tested OPRM1 only in each consortium separately (N=38,000, N=31,000, and N=16,000 smokers with cigarettes-per-day); estimated power to have detected the nicotine-specific odds ratio of 0.93 (Table 3) in at least one of the three consortia with genome-wide significance (alpha=5×10−8) is only 4%. Power details are in Supplementary Text S2. Hence it is not surprising that these smoking consortia did not report an OPRM1 effect.

This study contributes valuable information to connect functional findings to the clinically important outcome of addiction in humans. Several neurobiological, functional, and physiological changes have been demonstrated for the rs1799971 (A118G) amino acid change and a corresponding mutation in a similar region of the receptor in mice (A112G) (Drakenberg et al. 2006; Huang et al. 2012; Mague and Blendy 2010; Palmer and de Wit 2012; Ray et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2014). In vitro studies of the G allele have reported increased binding to β- endorphin (Bond et al. 1998), altered downstream signaling (Deb et al. 2010), and decreased mu opioid receptor expression (Zhang et al. 2005). In human brain imaging, the G allele is associated with striatal dopamine response to alcohol (Ramchandani et al. 2011) and increased mu opioid receptor binding potential (Ray et al. 2011). In mouse knock-in models (A112G), the G/G knock-in has shown reduced receptor protein levels overall and reduced reinforcing value of morphine in female mice (Mague et al. 2009), reduced G-protein signaling (Wang et al. 2014), and increased peak dopamine response to alcohol challenge (Ramchandani et al. 2011); changes are often brain-region specific.

It is important to note that some functional and neurobiological findings have been interpreted as indicating that the G allele of rs1799971 should increase risk for addiction, for example due to its association with greater alcohol-induced reinforcement and reward (Ramchandani et al. 2011; Ray and Hutchison 2004; Ray and Hutchison 2007; Ray et al. 2010). Our data-driven evidence of a modest protective effect of this allele on substance dependence liability is thus surprising and all the more important to integrate with functional findings to understand downstream contributions to human substance dependence. A protective effect of the G allele on addiction may be consistent with either increased or decreased reward/reinforcement, for example due to varying roles of positive versus negative reinforcement at different stages in the transition from use to dependence. Modeling these connections remains an open area to be worked out by neurobiological theories of addiction (Ray et al. 2012).

This project demonstrates the value of collaborative data sharing and meta-analysis, as the modest odds ratio of rs1799971 would be challenging to detect and consistently replicate in modestly sized candidate gene studies (Hall et al. 2013; Hart et al. 2013). Also important was our approach of defining consistent phenotypes across all datasets. In particular, careful definition of controls can help to detect associations (Nelson et al. 2013; Schinka et al. 2002). In our case, requiring controls to be at least 25 years of age led to stronger association results even with the reduced the number of controls.

This study has limitations. First, as in any meta-analysis, sample heterogeneity could not be completely avoided. Studies had diverse ascertainment schemes, with some designed to recruit dependent cases for one particular substance. Some studies recruited from the general population while others recruited potentially more extreme cases from treatment centers. Hence, over- and under-representation of phenotypes were present in contributing datasets, and the severity of dependence, degree of co-morbid dependence, and prevalence of substance exposure varied. Reduced proportions of exposed controls would reduce effective sample size and power for a study. But overall, uniform phenotype definitions were an important design feature to ameliorate effects of heterogeneity. Although some bias may have occurred, it seems unlikely to have been systematic in either direction. Similarly, it seems unlikely that systematic bias would have occurred due to differences between studies that contributed to this meta-analysis and those that declined to participate.

Second, this project interrogated only the non-synonymous variant rs1799971. As with any statistical association, our finding may reflect a proxy association for which the true functional variant(s) remain to be recognized. Other OPRM1 variants have been associated with addiction and merit consideration for future study (Clarke et al. 2013; Hancock et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2006a). Analyses of multiple SNPs and haplotypes will also be of future interest: recent evidence indicates an important role in heroin addiction for the haplotype structure of OPRM1, with the A allele of rs1799971 showing association only in the presence of the C allele of rs3778150 (Hancock et al. 2015). Importantly, (Hancock et al. 2015) also found that the G allele of rs1799971 is protective (A allele confers risk) on that background, agreeing with the direction of effect observed in our meta-analysis of general substance dependence.

Third, further phenotypic refinement is possible. We did not consider substance abuse criteria, nor did we use the newer diagnostic system, DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Our threshold for exposure was a single use for all substances except nicotine; therefore, the genetic effect of rs1799971 detected by our analyses may involve a combination of effects on development of regular/repeated use and effects on dependence. We focused on dichotomous diagnoses for each substance. For nicotine, we examined heavy/light smoking as the most widely available nicotine trait in our datasets. Consistency of results was confirmed using DSM-IV and Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence criteria when available. Because we focused on dichotomous diagnoses that could then be combined into the general substance dependence diagnosis, we did not examine quantitative or categorical cigarettes-per-day.

Fourth, we focused on main effects of rs1799971 to limit multiple testing. Thus, we did not examine gene-environment interactions (e.g., sex-specific effects) or gene-gene interactions. We did adjust statistically for sex, which showed no evidence for a main effect on general substance dependence (p = 0.57). Interactions likely have roles in a complex trait such as addiction, and could attenuate the genetic main effect when not accounted for (e.g. when the effect occurs only in a specific stratum). Thus, it is possible that the modest main effect that we detected could translate to a stronger effect if particular genetic or environmental backgrounds are considered. Future work could examine interactions nominated in the literature (Mague et al. 2009; Miranda et al. 2013; Ray et al. 2006).

Finally, a model that explicitly partitions the association between a general factor for any substance dependence and substance-specific components was not fitted to these data. Although such a model would allow a more refined distinction between general and specific associations (Medland and Neale 2010; Neale et al. 2006), we chose not to apply this because of the complexities of running and integrating such analyses across sites.

In closing, this data-driven, collaborative meta-analysis has demonstrated a modest protective effect of the G allele of rs1799971 on general liability to substance dependence. This work highlights the benefits of jointly studying related disorders: larger samples and insight into factors involved in underlying shared liability. An important strength of our approach is that the analyses of our datasets were designed and conducted in collaboration with the originating investigators. Thus, we benefited from collaborators' deep knowledge of their own data and our combined expertise on addiction. This effort underscores the value of collaboratively sharing data and expertise to accelerate discoveries.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Forest plot of general substance dependence and rs1799971 across studies that had at least 5 cases and 5 controls. Summary odds ratio, 95% Confidence Interval, and p-values are based on fixed effect meta-analysis. *indicates the subset of 10 studies that had all five specific substance dependence diagnoses, examined in secondary analyses to confirm consistency of results. Estimated heterogeneity variance was Q = 20.13 with a p-value of 0.387 among all 20 studies and Q = 6.49 with a p-value of 0.69 among the subset of 10 studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

For facilitating this collaboration to meta-analyze rs1799971, we thank Jonathan Pollock and the National Institute on Drug Abuse, which provided infrastructure support through conference calls and meetings. For this project we wish to acknowledge and thank the following people. For meta-analysis coordination at Washington University: Weimin Duan. For administrative support at Washington University: Sherri Fisher. We also thank Michael Bruchas, Washington University, for helpful discussions. For CADD: principal investigators John Hewitt, Institute for Behavioral Genetics, University of Colorado Boulder; Michael Stallings, Institute for Behavioral Genetics, University of Colorado Boulder; Christian Hopfer, University of Denver; Sandra Brown, University of California San Diego. For COGA: Principal Investigators B. Porjesz, V. Hesselbrock, H. Edenberg, L. Bierut; COGA includes ten different centers: University of Connecticut (V. Hesselbrock); Indiana University (H.J. Edenberg, J. Nurnberger Jr., T. Foroud); University of Iowa (S. Kuperman, J. Kramer); SUNY Downstate (B. Porjesz); Washington University in St. Louis (L. Bierut, A. Goate, J. Rice, K. Bucholz); University of California at San Diego (M. Schuckit); Rutgers University (J. Tischfield); Texas Biomedical Research Institute (L. Almasy), Howard University (R. Taylor) and Virginia Commonwealth University (D. Dick). Other COGA collaborators include: L. Bauer (University of Connecticut); D. Koller, S. O’Connor, L. Wetherill, X. Xuei (Indiana University); Grace Chan (University of Iowa); S. Kang, N. Manz, M. Rangaswamy (SUNY Downstate); J. Rohrbaugh, J-C Wang (Washington University in St. Louis); A. Brooks (Rutgers University); and F. Aliev (Virginia Commonwealth University). A. Parsian and M. Reilly are the NIAAA Staff Collaborators. We continue to be inspired by our memories of Henri Begleiter and Theodore Reich, founding PI and Co-PI of COGA, and also owe a debt of gratitude to other past organizers of COGA, including Ting-Kai Li, currently a consultant with COGA, P. Michael Conneally, Raymond Crowe, and Wendy Reich, for their critical contributions. The authors thank Kim Doheny and Elizabeth Pugh from CIDR and Justin Paschall from the NCBI dbGaP staff for valuable assistance with genotyping and quality control in developing the dataset available at dbGaP. For COGEND: COGEND is a collaborative research group and a part of the NIDA Genetics Consortium. Michael Brent, Alison Goate, Dorothy Hatsukami, Anthony Hinrichs, Heidi Kromrei, Tracey Richmond, Joe Henry Steinbach, Jerry Stitzel, Scott Saccone, Sharon Murphy; in memory of Theodore Reich, founding Principal Investigator of COGEND, we are indebted to his leadership in the establishment and nurturing of COGEND and acknowledge with great admiration his seminal scientific contributions to the field. For GADD: John Hewitt, Institute for Behavioral Genetics, University of Colorado Boulder; Michael Stallings, Institute for Behavioral Genetics, University of Colorado Boulder; Christian Hopfer, University of Denver; Sandra Brown, University of California San Diego. For Kreek: Matthew Randesi. For NAG: Yi-Ling Chou. For Yale-Penn: Genotyping services for a part of Yale-Penn were provided by the Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR) and Yale University (Center for Genome Analysis).

Funding Acknowledgments: R01 DA026911 from The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) supported this project and the coordinating team at Washington University. BG/ROMA are supported by R01 DA018823 from NIDA. CADD/GADD/NYS are supported by R01 DA021905, R01 AA017889, P60 DA011015, R01 DA012845, T32 DA017637, R01 DA021913, K24DA032555 and K01 AA019447 from NIDA and NIAAA. CATS is supported by R01 DA017305 from NIDA. Dr. Degenhardt is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Principal Research Fellowship. The National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre at the University of NSW is supported by funding from the Australian Government under the Substance Misuse Prevention and Service Improvements Grants Fund. CEDAR-SADS is supported by R01 DA019157, P50 DA005605 (CEDAR) and R01 DA011922 (SADS) from NIDA. Cinciripini was supported by R01 DA1182 (CASSI), K07 CA92209 (PEERS EMA), R21 CA81649 (PEERS NS), P50 CA070907 (PEERS WS) and P50 CA70907 (SCOPE) from NIDA and NCI. COGA is supported by U10 AA008401 from NIAAA and genotyping was supported by U01 HG004438 from The Genes and Environment Initiative (GEI) and HHSN268200782096C from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). COGEND is supported by R01 DA019963, R01 DA013423, P01 CA089392, R01 DA026911, and R01DA036583 from NIDA and the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Finnish Health 2000 is supported by Finnish National Institute for Health and Welfare institutional funding. Funding for COGEND genotyping was provided by 1 X01 HG005274-01 and performed at Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR) which is funded through a federal contract from NIH to JHU (HHSN268200782096C). Gene Environment Association Studies (GENEVA) Coordinating Center assisted with genotype cleaning as well as general study coordination. GENEVA is supported by U01 HG004446. FSCD is supported by R01 DA013423 from NIDA. FTC/FT12 is supported by K02 AA018755, AA-09203 and AA-12502 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), 141054 and 263278 from Academy of Finland. FTC/NAG-FIN is funded by GRAND from Pfizer Inc., 213506 and 129680 from Academy of Finland, Health-F4-2007-201413 from European Union Seventh Framework Programme, ENGAGE-project, DA12854 from NIDA, Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Sigrid Juselius Foundation and Jenny & Antti Wihuri Foundation. GESGA is supported by 01EB0410 from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, FZK 01GS08152 from National Genome Research Network (NGFN Plus), BMBF 01ZX1311A (e:Med program), and Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach-Stiftung. IAS is supported by R01 DA015789 from NIDA. Kreek is supported by P50 DA05130 from NIDA and The Adelson Medical Research Foundation. MCTFR is supported by R01 DA005147, R01 DA013240, U01 DA024417 from NIDA, R01 AA009367 and R01 AA0011886 from NIAAA and R01 MH066140 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). MGHD is supported by R01 DA012846 from NIDA/NIH, and grants from the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, NARSAD: The Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, the Sidney R. Baer, Jr. Foundation, and the Gerber Foundation. OYSUP is supported by RC2 DA028793 from NIDA. OZALC-NAG is supported by R01 AA075356, R01 AA07728, R01 AA13220, R01 AA13321, R01 AA13322, R01 AA11998 and R01 AA17688 from NIAAA, R01 DA12854 and K08 DA019951 from NIDA and grants from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. Patch II/PiP are supported by C53/A6281 from Cancer Research UK. Marcus Munafò and Paul Aveyard are members of the United Kingdom Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies, a UKCRC Public Health Research: Centre of Excellence. Funding from British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council, and the National Institute for Health Research, under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged. SMOFAM is supported by R01 DA003706, U01 DA020830 from NIDA and 7PT2000-2004 from University of California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program. Utah is supported by P01 HL72903 from NIDA and NHLBI. VA-Twin is supported by DA019498 from NIDA. Yale-Penn is supported by RC2 DA028909, R01 DA12690, R01 DA12849, R01 DA18432 and K01 DA24758 from NIDA, R01 AA017535 and R01 AA11330 from NIAAA and Young Investigator Award from NARSAD: the Brain and Behavior Research Fund. This project was also supported in part by the Division of Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health. Funding sources had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Bierut is listed as an inventor on Issued U.S. Patent 8,080,371, “Markers for Addiction” covering the used of certain SNPs in determining the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of addiction, and served as a consultant for Pfizer in 2008. Dr. NL Saccone is the spouse of Dr. SF Saccone, who is also listed as an inventor on the above patent. Dr. Cinciripini served on the scientific advisory board of Pfizer, conducted educational talks sponsored by Pfizer on smoking cessation (2006–2008), and has received grant support from Pfizer. Dr. Degenhardt has no relevant disclosures for this specific project; however, for general pharmaceutical company disclosures, Dr. Degenhardt has received untied educational grants from Reckitt Benckiser to conduct post-marketing surveillance of the diversion and injection of opioid substitution therapy medications in Australia. Although these activities are unrelated to the current study, Dr. Kranzler has been a consultant or advisory board member for Alkermes, Lilly, Lundbeck, Otsuka and Pfizer; he is also a member of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology's Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative, which is supported by Ethypharm, Lilly, Lundbeck, AbbVie, and Pfizer. Dr. Ridinger is member of the advisory board of Lundbeck referring to Nalmefene. Prof. Dr. N. Scherbaum received honoraria for several activities (advisory boards, lectures, manuscripts and educational material) by the factories Sanofi-Aventis, Reckitt-Benckiser, Lundbeck, and Janssen-Cilag. During the last three years he participated in clinical trials financed by the pharmaceutical industry. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent. The procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008. All participants provided informed consent.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th Edition. Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Tildesley E, Hops H, Duncan SC, Severson HH. Elementary school age children's future intentions and use of substances. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003;32(4):556–567. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias A, Feinn R, Kranzler HR. Association of an Asn40Asp (A118G) polymorphism in the mu-opioid receptor gene with substance dependence: a meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83(3):262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aromaa A, Koskinen S. Health and functional capacity in Finland: Baseline Results of the Health 2000 Health Examination Survey. Helsinki, Finland: National Public Health Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bart G, Kreek MJ, Ott J, LaForge KS, Proudnikov D, Pollak L, Heilig M. Increased attributable risk related to a functional mu-opioid receptor gene polymorphism in association with alcohol dependence in central Sweden. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30(2):417–422. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Befort K, Filliol D, Decaillot FM, Gaveriaux-Ruff C, Hoehe MR, Kieffer BL. A single nucleotide polymorphic mutation in the human mu-opioid receptor severely impairs receptor signaling. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276(5):3130–3137. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen AW, Kokoszka J, Peterson R, Long JC, Virkkunen M, Linnoila M, Goldman D. Mu opioid receptor gene variants: lack of association with alcohol dependence. Mol Psychiatry. 1997;2(6):490–494. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer A, Koch T, Schroder H, Schulz S, Hollt V. Effect of the A118G polymorphism on binding affinity, potency and agonist-mediated endocytosis, desensitization, and resensitization of the human mu-opioid receptor. J Neurochem. 2004;89(3):553–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierut LJ, Agrawal A, Bucholz KK, Doheny KF, Laurie C, Pugh E, Fisher S, Fox L, Howells W, Bertelsen S, Hinrichs AL, Almasy L, Breslau N, Culverhouse RC, Dick DM, Edenberg HJ, Foroud T, Grucza RA, Hatsukami D, Hesselbrock V, Johnson EO, Kramer J, Krueger RF, Kuperman S, Lynskey M, Mann K, Neuman RJ, Nothen MM, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Porjesz B, Ridinger M, Saccone NL, Saccone SF, Schuckit MA, Tischfield JA, Wang JC, Rietschel M, Goate AM, Rice JP. A genome-wide association study of alcohol dependence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(11):5082–5087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911109107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierut LJ, Dinwiddie SH, Begleiter H, Crowe RR, Hesselbrock V, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Porjesz B, Schuckit MA, Reich T. Familial transmission of substance dependence: alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, and habitual smoking: a report from the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(11):982–988. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.11.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierut LJ, Strickland JR, Thompson JR, Afful SE, Cottler LB. Drug use and dependence in cocaine dependent subjects, community-based individuals, and their siblings. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;95(1–2):14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond C, LaForge KS, Tian M, Melia D, Zhang S, Borg L, Gong J, Schluger J, Strong JA, Leal SM, Tischfield JA, Kreek MJ, Yu L. Single-nucleotide polymorphism in the human mu opioid receptor gene alters beta-endorphin binding and activity: possible implications for opiate addiction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(16):9608–9613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broms U, Wedenoja J, Largeau MR, Korhonen T, Pitkaniemi J, Keskitalo-Vuokko K, Happola A, Heikkila KH, Heikkila K, Ripatti S, Sarin AP, Salminen O, Paunio T, Pergadia ML, Madden PA, Kaprio J, Loukola A. Analysis of detailed phenotype profiles reveals CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4 gene cluster association with several nicotine dependence traits. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(6):720–733. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BL, Lam CY, Robinson JD, Paris MM, Waters AJ, Wetter DW, Cinciripini PM. Real-time craving and mood assessments before and after smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(7):1165–1169. doi: 10.1080/14622200802163084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Liu L, Xiao Y, Peng Y, Yang C, Wang Z. Ethnic-specific meta-analyses of association between the OPRM1 A118G polymorphism and alcohol dependence among Asians and Caucasians. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012a;123(1–3):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LS, Saccone NL, Culverhouse RC, Bracci PM, Chen CH, Dueker N, Han Y, Huang H, Jin G, Kohno T, Ma JZ, Przybeck TR, Sanders AR, Smith JA, Sung YJ, Wenzlaff AS, Wu C, Yoon D, Chen YT, Cheng YC, Cho YS, David SP, Duan J, Eaton CB, Furberg H, Goate AM, Gu D, Hansen HM, Hartz S, Hu Z, Kim YJ, Kittner SJ, Levinson DF, Mosley TH, Payne TJ, Rao DC, Rice JP, Rice TK, Schwantes-An TH, Shete SS, Shi J, Spitz MR, Sun YV, Tsai FJ, Wang JC, Wrensch MR, Xian H, Gejman PV, He J, Hunt SC, Kardia SL, Li MD, Lin D, Mitchell BD, Park T, Schwartz AG, Shen H, Wiencke JK, Wu JY, Yokota J, Amos CI, Bierut LJ. Smoking and genetic risk variation across populations of European, Asian, and African American ancestry--a meta-analysis of chromosome 15q25. Genet Epidemiol. 2012b;36(4):340–351. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Chen J, Williamson VS, An SS, Hettema JM, Aggen SH, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Variants in nicotinic acetylcholine receptors alpha5 and alpha3 increase risks to nicotine dependence. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheverud JM. A simple correction for multiple comparisons in interval mapping genome scans. Heredity. 2001;87(Pt 1):52–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2540.2001.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinciripini PM, Robinson JD, Carter BL, Lam C, Wu X, de Moor CA, Baile WF, Wetter DW. The effects of smoking deprivation and nicotine administration on emotional reactivity. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(3):379–392. doi: 10.1080/14622200600670272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinciripini PM, Tsoh JY, Wetter DW, Lam C, de Moor C, Cinciripini L, Baile W, Anderson C, Minna JD. Combined effects of venlafaxine, nicotine replacement, and brief counseling on smoking cessation. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;13(4):282–292. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.13.4.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke TK, Crist RC, Kampman KM, Dackis CA, Pettinati HM, O'Brien CP, Oslin DW, Ferraro TN, Lohoff FW, Berrettini WH. Low frequency genetic variants in the mu-opioid receptor (OPRM1) affect risk for addiction to heroin and cocaine. Neurosci Lett. 2013;542:71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coller JK, Beardsley J, Bignold J, Li Y, Merg F, Sullivan T, Cox TC, Somogyi AA. Lack of association between the A118G polymorphism of the mu opioid receptor gene (OPRM1) and opioid dependence: A meta-analysis. Pharmgenomics Pers Med. 2009:29–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crist RC, Berrettini WH. Pharmacogenetics of OPRM1. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Identification of risk loci with shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet. 2013;381(9875):1371–1379. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62129-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley JJ, Oslin DW, Patkar AA, Gottheil E, DeMaria PA, Jr, O'Brien CP, Berrettini WH, Grice DE. A genetic association study of the mu opioid receptor and severe opioid dependence. Psychiatr Genet. 2003;13(3):169–173. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200309000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David SP, Johnstone EC, Churchman M, Aveyard P, Murphy MF, Munafo MR. Pharmacogenetics of smoking cessation in general practice: results from the Patch II and Patch in Practice trials. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(3):157–167. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb I, Chakraborty J, Gangopadhyay PK, Choudhury SR, Das S. Single-nucleotide polymorphism (A118G) in exon 1 of OPRM1 gene causes alteration in downstream signaling by mu-opioid receptor and may contribute to the genetic risk for addiction. J Neurochem. 2010;112(2):486–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drakenberg K, Nikoshkov A, Horvath MC, Fagergren P, Gharibyan A, Saarelainen K, Rahman S, Nylander I, Bakalkin G, Rajs J, Keller E, Hurd YL. Mu opioid receptor A118G polymorphism in association with striatal opioid neuropeptide gene expression in heroin abusers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(20):7883–7888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600871103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edenberg HJ. The collaborative study on the genetics of alcoholism: an update. Alcohol Res Health. 2002;26(3):214–218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edenberg HJ, Koller DL, Xuei X, Wetherill L, McClintick JN, Almasy L, Bierut LJ, Bucholz KK, Goate A, Aliev F, Dick D, Hesselbrock V, Hinrichs A, Kramer J, Kuperman S, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Rice JP, Schuckit MA, Taylor R, Todd Webb B, Tischfield JA, Porjesz B, Foroud T. Genome-wide association study of alcohol dependence implicates a region on chromosome 11. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34(5):840–852. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Huizinga D, Ageton SS. Explaining delinquency and drug use. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Huizinga D, Menard S. Multiple Problem Youth: Delinquency, Drugs and Mental Health Problems. New York, NY: Springer; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Frank J, Cichon S, Treutlein J, Ridinger M, Mattheisen M, Hoffmann P, Herms S, Wodarz N, Soyka M, Zill P, Maier W, Mossner R, Gaebel W, Dahmen N, Scherbaum N, Schmal C, Steffens M, Lucae S, Ising M, Muller-Myhsok B, Nothen MM, Mann K, Kiefer F, Rietschel M. Genome-wide significant association between alcohol dependence and a variant in the ADH gene cluster. Addict Biol. 2012;17(1):171–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke P, Wang T, Nothen MM, Knapp M, Neidt H, Albrecht S, Jahnes E, Propping P, Maier W. Nonreplication of association between mu-opioid-receptor gene (OPRM1) A118G polymorphism and substance dependence. American journal of medical genetics. 2001;105(1):114–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelernter J, Kranzler H, Cubells J. Genetics of two mu opioid receptor gene (OPRM1) exon I polymorphisms: population studies, and allele frequencies in alcohol- and drug-dependent subjects. Mol Psychiatry. 1999;4(5):476–483. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelernter J, Kranzler HR, Sherva R, Almasy L, Koesterer R, Smith AH, Anton R, Preuss UW, Ridinger M, Rujescu D, Wodarz N, Zill P, Zhao H, Farrer LA. Genome-wide association study of alcohol dependence: significant findings in African- and European-Americans including novel risk loci. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(1):41–49. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelernter J, Kranzler HR, Sherva R, Koesterer R, Almasy L, Zhao H, Farrer LA. Genome-Wide association study of opioid dependence: multiple associations mapped to calcium and potassium pathways. Biol Psychiatry. 2013a doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelernter J, Sherva R, Koesterer R, Almasy L, Zhao H, Kranzler HR, Farrer L. Genome-wide association study of cocaine dependence and related traits: FAM53B identified as a risk gene. Mol Psychiatry. 2013b doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatt SJ, Bousman C, Wang RS, Murthy KK, Rana BK, Lasky-Su JA, Zhu SC, Zhang R, Li J, Zhang B, Lyons MJ, Faraone SV, Tsuang MT. Evaluation of OPRM1 variants in heroin dependence by family-based association testing and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90(2–3):159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grucza RA, Wang JC, Stitzel JA, Hinrichs AL, Saccone SF, Saccone NL, Bucholz KK, Cloninger CR, Neuman RJ, Budde JP, Fox L, Bertelsen S, Kramer J, Hesselbrock V, Tischfield J, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Almasy L, Porjesz B, Kuperman S, Schuckit MA, Edenberg HJ, Rice JP, Goate AM, Bierut LJ. A risk allele for nicotine dependence in CHRNA5 is a protective allele for cocaine dependence. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(11):922–929. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haerian BS, Haerian MS. OPRM1 rs1799971 polymorphism and opioid dependence: evidence from a meta-analysis. Pharmacogenomics. 2013;14(7):813–824. doi: 10.2217/pgs.13.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall FS, Drgonova J, Jain S, Uhl GR. Implications of genome wide association studies for addiction: are our a priori assumptions all wrong? Pharmacol Ther. 2013;140(3):267–279. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock DB, Levy JL, Gaddis NC, Glasheen C, Saccone NL, Page GP, Hulse GK, Wildenauer D, Kelty EA, Schwab SG, Degenhardt L, Martin NG, Montgomery GW, Attia J, Holliday EG, McEvoy M, Scott RJ, Bierut LJ, Nelson EC, Kral AH, Johnson EO. Cis-Expression Quantitative Trait Loci Mapping Reveals Replicable Associations with Heroin Addiction in OPRM1. Biol Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin J, He Y, Javitz HS, Wessel J, Krasnow RE, Tildesley E, Hops H, Swan GE, Bergen AW. Nicotine withdrawal sensitivity, linkage to chr6q26, and association of OPRM1 SNPs in the SMOking in FAMilies (SMOFAM) sample. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(12):3399–3406. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart AB, de Wit H, Palmer AA. Candidate gene studies of a promising intermediate phenotype: failure to replicate. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(5):802–816. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartz SM, Short SE, Saccone NL, Culverhouse R, Chen L, Schwantes-An TH, Coon H, Han Y, Stephens SH, Sun J, Chen X, Ducci F, Dueker N, Franceschini N, Frank J, Geller F, Gubjartsson D, Hansel NN, Jiang C, Keskitalo-Vuokko K, Liu Z, Lyytikainen LP, Michel M, Rawal R, Rosenberger A, Scheet P, Shaffer JR, Teumer A, Thompson JR, Vink JM, Vogelzangs N, Wenzlaff AS, Wheeler W, Xiao X, Yang BZ, Aggen SH, Balmforth AJ, Baumeister SE, Beaty T, Bennett S, Bergen AW, Boyd HA, Broms U, Campbell H, Chatterjee N, Chen J, Cheng YC, Cichon S, Couper D, Cucca F, Dick DM, Foroud T, Furberg H, Giegling I, Gu F, Hall AS, Hallfors J, Han S, Hartmann AM, Hayward C, Heikkila K, Hewitt JK, Hottenga JJ, Jensen MK, Jousilahti P, Kaakinen M, Kittner SJ, Konte B, Korhonen T, Landi MT, Laatikainen T, Leppert M, Levy SM, Mathias RA, McNeil DW, Medland SE, Montgomery GW, Muley T, Murray T, Nauck M, North K, Pergadia M, Polasek O, Ramos EM, Ripatti S, Risch A, Ruczinski I, Rudan I, Salomaa V, Schlessinger D, Styrkarsdottir U, Terracciano A, Uda M, Willemsen G, Wu X, Abecasis G, Barnes K, Bickeboller H, Boerwinkle E, Boomsma DI, Caporaso N, Duan J, Edenberg HJ, Francks C, Gejman PV, Gelernter J, Grabe HJ, Hops H, Jarvelin MR, Viikari J, Kahonen M, Kendler KS, Lehtimaki T, Levinson DF, Marazita ML, Marchini J, Melbye M, Mitchell BD, Murray JC, Nothen MM, Penninx BW, Raitakari O, Rietschel M, Rujescu D, Samani NJ, Sanders AR, Schwartz AG, Shete S, Shi J, Spitz M, Stefansson K, Swan GE, Thorgeirsson T, Volzke H, Wei Q, Wichmann HE, Amos CI, Breslau N, Cannon DS, Ehringer M, Grucza R, Hatsukami D, Heath A, Johnson EO, Kaprio J, Madden P, Martin NG, Stevens VL, Stitzel JA, Weiss RB, Kraft P, Bierut LJ. Increased Genetic Vulnerability to Smoking at CHRNA5 in Early-Onset Smokers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(8):854–860. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoft NR, Corley RP, McQueen MB, Schlaepfer IR, Huizinga D, Ehringer MA. Genetic association of the CHRNA6 and CHRNB3 genes with tobacco dependence in a nationally representative sample. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(3):698–706. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hops H, Andrews JA, Duncan SC, Duncan TE, Tildesley E. Adolescent drug use development: a social interactional and contextual perspective. In: Sameroff AJ, Lewis M, editors. Handbook of Developmental Psychopathology. New York: Cluwer Academic/Plenum; 2000. pp. 589–605. [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Chen C, Mague SD, Blendy JA, Liu-Chen LY. A common single nucleotide polymorphism A118G of the mu opioid receptor alters its N-glycosylation and protein stability. Biochem J. 2012;441(1):379–386. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor J, Elkins IJ, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance-use disorders: findings from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11(4):869–900. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamens HM, Corley RP, McQueen MB, Stallings MC, Hopfer CJ, Crowley TJ, Brown SA, Hewitt JK, Ehringer MA. Nominal association with CHRNA4 variants and nicotine dependence. Genes Brain Behav. 2013;12(3):297–304. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaprio J, Pulkkinen L, Rose RJ. Genetic and environmental factors in health-related behaviors: studies on Finnish twins and twin families. Twin Res. 2002;5(5):366–371. doi: 10.1375/136905202320906101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Myers J, Prescott CA. Specificity of genetic and environmental risk factors for symptoms of cannabis, cocaine, alcohol, caffeine, and nicotine dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(11):1313–1320. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.11.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes MA, Malone SM, Elkins IJ, Legrand LN, McGue M, Iacono WG. The enrichment study of the Minnesota twin family study: increasing the yield of twin families at high risk for externalizing psychopathology. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2009;12(5):489–501. doi: 10.1375/twin.12.5.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SG, Kim CM, Kang DH, Kim YJ, Byun WT, Kim SY, Park JM, Kim MJ, Oslin DW. Association of functional opioid receptor genotypes with alcohol dependence in Koreans. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28(7):986–990. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000130803.62768.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ, Koob GF. Drug dependence: stress and dysregulation of brain reward pathways. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51(1–2):23–47. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam CY, Robinson JD, Versace F, Minnix JA, Cui Y, Carter BL, Wetter DW, Cinciripini PM. Affective reactivity during smoking cessation of never-quitters as compared with that of abstainers, relapsers, and continuing smokers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;20(2):139–150. doi: 10.1037/a0026109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessov CN, Martin NG, Statham DJ, Todorov AA, Slutske WS, Bucholz KK, Heath AC, Madden PA. Defining nicotine dependence for genetic research: evidence from Australian twins. Psychological medicine. 2004;34(5):865–879. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levran O, Londono D, O'Hara K, Nielsen DA, Peles E, Rotrosen J, Casadonte P, Linzy S, Randesi M, Ott J, Adelson M, Kreek MJ. Genetic susceptibility to heroin addiction: a candidate gene association study. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7(7):720–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00410.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levran O, Yuferov V, Kreek MJ. The genetics of the opioid system and specific drug addictions. Hum Genet. 2012;131(6):823–842. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1172-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Ji L. Adjusting multiple testing in multilocus analyses using the eigenvalues of a correlation matrix. Heredity. 2005;95(3):221–227. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JZ, Tozzi F, Waterworth DM, Pillai SG, Muglia P, Middleton L, Berrettini W, Knouff CW, Yuan X, Waeber G, Vollenweider P, Preisig M, Wareham NJ, Zhao JH, Loos RJ, Barroso I, Khaw KT, Grundy S, Barter P, Mahley R, Kesaniemi A, McPherson R, Vincent JB, Strauss J, Kennedy JL, Farmer A, McGuffin P, Day R, Matthews K, Bakke P, Gulsvik A, Lucae S, Ising M, Brueckl T, Horstmann S, Wichmann HE, Rawal R, Dahmen N, Lamina C, Polasek O, Zgaga L, Huffman J, Campbell S, Kooner J, Chambers JC, Burnett MS, Devaney JM, Pichard AD, Kent KM, Satler L, Lindsay JM, Waksman R, Epstein S, Wilson JF, Wild SH, Campbell H, Vitart V, Reilly MP, Li M, Qu L, Wilensky R, Matthai W, Hakonarson HH, Rader DJ, Franke A, Wittig M, Schafer A, Uda M, Terracciano A, Xiao X, Busonero F, Scheet P, Schlessinger D, St Clair D, Rujescu D, Abecasis GR, Grabe HJ, Teumer A, Volzke H, Petersmann A, John U, Rudan I, Hayward C, Wright AF, Kolcic I, Wright BJ, Thompson JR, Balmforth AJ, Hall AS, Samani NJ, Anderson CA, Ahmad T, Mathew CG, Parkes M, Satsangi J, Caulfield M, Munroe PB, Farrall M, Dominiczak A, Worthington J, Thomson W, Eyre S, Barton A, Mooser V, Francks C, Marchini J. Meta-analysis and imputation refines the association of 15q25 with smoking quantity. Nat Genet. 2010;42(5):436–440. doi: 10.1038/ng.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loukola A, Broms U, Maunu H, Widen E, Heikkila K, Siivola M, Salo A, Pergadia ML, Nyman E, Sammalisto S, Perola M, Agrawal A, Heath AC, Martin NG, Madden PA, Peltonen L, Kaprio J. Linkage of nicotine dependence and smoking behavior on 10q, 7q and 11p in twins with homogeneous genetic background. Pharmacogenomics J. 2008;8(3):209–219. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumley T. rmeta: Meta-analysis, R package version 2.15. In, pp. [Google Scholar]

- Mague SD, Blendy JA. OPRM1 SNP (A118G): involvement in disease development, treatment response, and animal models. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108(3):172–182. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mague SD, Isiegas C, Huang P, Liu-Chen LY, Lerman C, Blendy JA. Mouse model of OPRM1 (A118G) polymorphism has sex-specific effects on drug-mediated behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(26):10847–10852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901800106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher BS, Vladimirov VI, Latendresse SJ, Thiselton DL, McNamee R, Kang M, Bigdeli TB, Chen X, Riley BP, Hettema JM, Chilcoat H, Heidbreder C, Muglia P, Murrelle EL, Dick DM, Aliev F, Agrawal A, Edenberg HJ, Kramer J, Nurnberger J, Tischfield JA, Devlin B, Ferrell RE, Kirillova GP, Tarter RE, Kendler KS, Vanyukov MM. The AVPR1A gene and substance use disorders: association, replication, and functional evidence. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70(6):519–527. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Keyes M, Sharma A, Elkins I, Legrand L, Johnson W, Iacono WG. The environments of adopted and non-adopted youth: evidence on range restriction from the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS) Behav Genet. 2007;37(3):449–462. doi: 10.1007/s10519-007-9142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medland SE, Neale MC. An integrated phenomic approach to multivariate allelic association. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18(2):233–239. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Stolar M, Stevens DE, Goulet J, Preisig MA, Fenton B, Zhang H, O'Malley SS, Rounsaville BJ. Familial transmission of substance use disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(11):973–979. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.11.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, Basu S, Cunningham J, Eskin E, Malone SM, Oetting WS, Schork N, Sul JH, Iacono WG, McGue M. The Minnesota Center for Twin and Family Research genome-wide association study. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2012;15(6):767–774. doi: 10.1017/thg.2012.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnix JA, Robinson JD, Lam CY, Carter BL, Foreman JE, Vandenbergh DJ, Tomlinson GE, Wetter DW, Cinciripini PM. The serotonin transporter gene and startle response during nicotine deprivation. Biol Psychol. 2011;86(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R, Jr, Reynolds E, Ray L, Justus A, Knopik VS, McGeary J, Meyerson LA. Preliminary evidence for a gene-environment interaction in predicting alcohol use disorders in adolescents. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(2):325–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munafo MR, Johnstone EC, Aveyard P, Marteau T. Lack of association of OPRM1 genotype and smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(3):739–744. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Harvey E, Maes HH, Sullivan PF, Kendler KS. Extensions to the modeling of initiation and progression: applications to substance use and abuse. Behav Genet. 2006;36(4):507–524. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EC, Lynskey MT, Heath AC, Wray N, Agrawal A, Shand FL, Henders AK, Wallace L, Todorov AA, Schrage AJ, Madden PA, Degenhardt L, Martin NG, Montgomery GW. Association of OPRD1 polymorphisms with heroin dependence in a large case-control series. Addict Biol. 2014;19(1):111–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EC, Lynskey MT, Heath AC, Wray N, Agrawal A, Shand FL, Henders AK, Wallace L, Todorov AA, Schrage AJ, Saccone NL, Madden PA, Degenhardt L, Martin NG, Montgomery GW. ANKK1, TTC12, and NCAM1 polymorphisms and heroin dependence: importance of considering drug exposure. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(3):325–333. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolov MA, Beltcheva O, Galabova A, Ljubenova A, Jankova E, Gergov G, Russev AA, Lynskey MT, Nelson EC, Nesheva E, Krasteva D, Lazarov P, Mitev VI, Kremensky IM, Kaneva RP, Todorov AA. No evidence of association between 118A>G OPRM1 polymorphism and heroin dependence in a large Bulgarian case-control sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;117(1):62–65. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyholt DR. A simple correction for multiple testing for single-nucleotide polymorphisms in linkage disequilibrium with each other. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74(4):765–769. doi: 10.1086/383251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]