Abstract

Anatomy of male and female external genitalia of adult mice (Mus musculus) and broad-footed moles (Scapanus latimanus) was re-examined to provide more meaningful anatomical terminology. In the past the perineal appendage of male broad-footed moles has been called the penis, while the female perineal appendage has been given several terms (e.g. clitoris, penile clitoris, peniform clitoris and others). Histological examination demonstrates that perineal appendages of male and female broad-footed moles are the prepuce, which in both sexes are covered externally with a hair-bearing epidermis and lacks erectile bodies. The inner preputial epithelium is non-hair-bearing and defines the preputial space in both sexes. The penis of broad-footed moles lies deep within the preputial space, is an “internal organ” in the resting state and contains the penile urethra, os penis, and erectile bodies. The clitoris of broad-footed moles is defined by a U-shaped clitoral epithelial lamina. Residing within clitoral stroma encompassed by the clitoral epithelial lamina is the corpus cavernosum, blood-filled spaces and the urethra. External genitalia of male and female mice are anatomically similar to that of broad-footed moles with the exception that in female mice the clitoris contains a small os clitoridis and lacks defined erectile bodies, while male mice have an os penis and a prominent distal cartilaginous structure within the male urogenital mating protuberance (MUMP). Clitori of female broad-footed moles lack an os clitoridis but contain defined erectile bodies, while male moles have an os penis similar to the mouse but lack the distal cartilaginous structure.

Keywords: prepuce, penis, clitoris, preputial space, moles, mice

Introduction

The European mole (Talpa europaea) is one of numerous mammalian species whose external genitalia defy the conventional visual distinctions between males and females so obvious in humans, in so far as perineal appendages (external genitalia) of male and female moles are of similar size (Wood-Jones, 1914; Matthews, 1935; Drea and Weil, 2008; Cunha et al., 2014). Female ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) and spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta) present even more extreme examples of masculinization of the external genitalia (Drea and Weil, 2008; Cunha et al., 2014). While the masculinized female perineal appendages of these species are striking, what is the correct anatomical identity of these structures? The answer to this question is crucial, as research on sexual differentiation of external genitalia requires anatomical precision when stipulating the nature of sex differences. The ongoing reference to penile clitoris or peniform clitoris in discussions of female mole genitalia of diverse species lacks such precision.

Recent studies on external genitalia in mice have emphasized their anatomical complexity (Yang et al., 2010; Rodriguez et al., 2011; Blaschko et al., 2013). These studies addressed the question of the anatomic nature of perineal appendages in male and female mice and demonstrated that female and male mouse perineal appendages are prepuce (and not clitoris or penis), which raises the question of the nature of the perineal appendages in male and female moles. The male prepuce is a flap of skin associated with the penis that covers part of the penis (human) or creates a voluminous space that houses the penis (mice, moles and rats). In contrast, the penis is a rod-like organ containing erectile bodies, urethra and in some species bone. These simple universal anatomical features of penis versus prepuce are the starting points of our investigation.

Historically, the two most influential treatises on mole external genitalia were published by F. Wood-Jones in 1914 and L.H. Matthews in 1935 (Wood-Jones, 1914; Matthews, 1935). Both of these investigators were impressed by the similarity in size and shape of perineal appendages in male and female moles, which were described as penis and clitoris. Matthews also used the terminology, “peniform clitoris, which is traversed by the urethra” (Matthews, 1935). Both Wood-Jones and Matthews recognized the prepuce, which ensheathed both the penis and clitoris, but based upon developmental considerations considered the prepuce integral to the penis/clitoris as indicated in the following quote: “The genital tubercle ensheathed in the overgrown outer genital fold has become recognizable as the adult penis” (Wood-Jones, 1914). We now recognize the perineal appendage in mice as an independent structure called the external prepuce which creates a voluminous space housing the penis (Rodriguez et al., 2011; Weiss et al., 2012; Blaschko et al., 2013; Cunha et al., 2015). Male mice and rats (see below) have two prepuces. The large external prepuce is not part of the penis, but instead creates a protective space housing the penis. The smaller internal prepuce of male mice and rats is integral to the penis and thus is similar to that of humans (Blaschko et al., 2013). The idea espoused by Wood-Jones and Matthews that the prepuce is an integral part of clitoris or penis in moles is hardly justified given that neither Wood-Jones nor Matthews presented any histological data of adult external genitalia of Talpa europaea to support this idea. The wholemount gross anatomical images of external genitalia of the adult European mole (Talpa europaea) (Wood-Jones, 1914; Matthews, 1935) is simply inadequate to resolve the question of whether the prepuce is integral to the penis or clitoris or is a separate entity. Accordingly, it is appropriate to re-examine in moles and mice the terms, penis, clitoris and prepuce, in order to determine which elements within adult mole external genitalia are responsible to the apparent female masculinization.

Matthews relied on Wood Jones' anatomical description of differentiation and development of the clitoris and adds that: “The urethra is formed along the ventral surface of the genital tubercle by fusion of the inner genital folds (labia minora), while the labial-scrotal folds enwrap the genital tubercle, fusing in the mid-ventral line to form the outer layers and prepuce of the clitoris” (Matthews, 1935). Accordingly, Matthews designated the perineal appendages of male and female moles as penis and peniform clitoris. Clearly, Wood-Jones and Matthews considered the similarly sized perineal appendages of Talpa europaea to be penis and clitoris, despite the fact that definitive histological data on adult external genitalia was not presented in their publications.

Given the use of the term peniform clitoris by Matthews and the apparent similarity of size and shape of external genitalia in moles cited by Wood-Jones, subsequent investigators perpetuated and in some cases expanded the descriptive terminology of mole external genitalia to include such terms as phallic-like clitoris, penile clitoris, phallus, female urinary papilla and peniform clitoris (Gorman and Stone, 1990; Whitworth et al., 1999; Rubenstein et al., 2003; Zurita et al., 2003; Carmona et al., 2008) in papers focused, not on anatomy of mole external genitalia, but instead on the endocrine parameters that might account for masculinization of the female external genitalia.

The term, peniform clitoris, has also been used in reference to the spotted hyena. In the spotted hyena the clitoris is a pendulous perineal appendage similar in size to the penis, contains erectile bodies, and is capable of erections fully justifying the term penile clitoris (Cunha et al., 2014). Similarly, the external genitalia of female ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) clearly merit the term penile clitoris (Drea, 2007). Whether the terms penile clitoris, peniform clitoris or similar terms are justified in regard to moles is the subject of this paper. Accordingly, our paper asks the questions in mice and moles: (a) What defines a penis? (b) What defines a clitoris? (c) What defines the prepuce, and (d) is the perineal appendage in moles a penis, a clitoris or prepuce?

Based upon recent findings on the anatomy of external genitalia of mice and spotted hyenas (Yang et al., 2010; Rodriguez et al., 2011; Weiss et al., 2012; Blaschko et al., 2013; Cunha et al., 2014), the ongoing use of terms such as penile clitoris and peniform clitoris, in reference to mole external genitalia requires critical re-evaluation and detailed objective anatomic/histologic analysis. Terminology of mole external genitalia, as enunciated in the pioneering studies of F. Wood-Jones and L. H. Matthews, was based upon gross anatomical analysis without corroborating histologic observations, which are essential to distinguish prepuce from penis and clitoris. In a broader sense, the anatomy of external genitalia of numerous mammalian species, especially in “rodent-like” animals (mice, rats, and moles) has suffered from inaccurate and inadequate terminology that persists to this day. For example, in the website, “Contents – The Anatomy of the Laboratory Mouse” (http://www.informatics.jax.org/cookbook/contents.shtml), is a drawing of male mouse external genitalia in which the perineal elevation is labeled as “penis”. Unfortunately, the perineal elevation of mice is the prepuce. The penis is a rod-like organ situated within the preputial space defined by the prepuce (Rodriguez et al., 2011; Cunha et al., 2015). Likewise, the literature of female mouse external genitalia is particularly under-represented. For example, a Pubmed search with “clitoris”, “mouse” or “mice” in the title field yields only two anatomically relevant papers (Homburger et al., 1950; Martin-Alguacil et al., 2008b). A similar Pubmed search of with “clitoris” and “rat” in the title field yields only three papers relevant to morphology (Purinton et al., 1976; Dangoor et al., 2005; Welsh et al., 2010). Thus, the anatomy of the external genitalia is strikingly under-represented in the literature and in many cases in need of critical re-evaluation.

Several mole species from North America, Europe and Japan possess an ovotestis, which has been shown to be the source of androgens that might account for masculinization of female external genitalia (Jimenez et al., 1993; Whitworth et al., 1999; Zurita et al., 2003; Zurita et al., 2007). Curiously mole species lacking an ovotestis (Scapanus latimanus, Scapanus orarius, and Scalopus aquaticus) also have what has been called a masculinized clitoris (Mossman and Duke, 1973; Rubenstein et al., 2003). In this paper we have examined the external genitalia of a North American mole, Scapanus latimanus, whose females lack ovotestes but nonetheless have a prominent perineal projection similar in size to that of males. Accordingly, we have used Scapanus latimanus to define the anatomy of a generic mole clitoris that has not been altered by possible androgen production from the ovotestis using modern anatomical techniques. In so doing, other mole species possessing an ovotestis (Talpa europaea) can be compared and contrasted to Scapanus latimanus, and possible effects of the ovotestis can be studied in the context of accurate, histologically verified anatomy. Our paper provides an accurate detailed description of the external genitalia of broad-footed mole (Scapanus latimanus) based upon gross and microscopic anatomy with comparison to mouse external genitalia and objectively defines the various anatomical components constituting mole external genitalia.

Our current study demonstrates that the perineal appendages (external genitalia) of male and female broad-footed moles are not the penis or penile clitoris, but instead is prepuce. Using the mouse as a prototypic model of rodent/insectivore external genitalia, we have arrived at explicit objective definitions of the elements constituting mouse and mole external genitalia, which provide the required anatomical precision for our future study of the comparative anatomy of 4 species of moles: the broad-footed mole (Scapanus latimanus), the star-nosed mole (Condylura cristata), the hairy-tailed mole (Parascalops breweri), and the Japanese shrew mole (Urotrichus talpoides).

Materials and Methods

Mice (Mus Musculus)

Adult wild-type CD-1 mice (Mus musculus, Charles River Breeding Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA) were housed in polycarbonate cages (20 X 25 X 47 cm3) with laboratory grade pellet bedding. Mice were given Purina lab diet and tap water ad libitum and euthanized at 60 days of age. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California, San Francisco approved all animal protocols. Following euthanasia of adult male and female mice, the hair surrounding the external genitalia was removed following treatment with Nair © to allow clear photography of the external genitalia. This study is based upon the analysis of 19 male and 11 female mice.

Broad-footed mole (Scapanus latimanus)

Live broad-footed moles were obtained from golf courses in San Francisco and Moraga, California (Moraga Country Club, San Francisco Golf Club, Harding Park Golf Club, and the Presidio Golf Course) between 2008 and 2010. Broad-footed moles were euthanized using 0.05 ml of Euthasol diluted with saline (from Virbac Animal Health Inc., 390mg Pentobarbital sodium and 50mg phenytoin sodium per ml). Animals were either perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde before dissection, or the lower torso was cut open to expose the reproductive organs and immersed in fixative. After a minimum of 48 hours of fixation, tissues were transferred sequentially through graded ethanols before being stored at room temperature in 70% ethanol. Subsequently, hair was plucked and trimmed to obtain a clear view of the external genitalia.

For the purposes of this paper adult non-breeding season male and female broad-footed moles were used since breeding season animals mostly eluded our traps. Seasonal classification of males was based on testicular weight and sperm production. The difference in testicular weight from the breeding season to the non-breeding season is significant. Histological examination of testes revealed breeding season males to have larger more developed interstitial cells and large seminiferous tubules containing developing sperm relative to non-breeding season individuals. Classification of males as either adult or juvenile was determined by histological examination of preputial separation from the penis. Preputial separation has been found to be androgen-dependent and to occur near the onset of puberty (Korenbrot et al., 1977).

Adult non-breeding season female broad-footed moles were also utilized. As reported previously (Rubenstein et al., 2003), the vagina was imperforate in females trapped in March-November, which was consistent with the non-breeding season for this species (Gorman and Stone, 1990). Uteri and oviducts of adult non-breeding season females are significantly smaller, less vascularized, and less developed than breeding season females, which coincided with vaginal impatency. This study is based upon the analysis of 11 male and 9 female moles (Scapanus latimanus).

Rats (Rattus rattus)

Six adult male rats were euthanized as per the mice, and external genitalia were dissected, and photographed. Serial paraffin sections were then prepared. Based upon gross anatomical and microscopic examination, a simple line drawing of the salient features of the rat penis and internal and external prepuces was constructed.

Histological Analysis

Mouse and broad-footed mole external genitalia were dissected, fixed in 10% buffered formalin and subsequently stored in 70% ethanol at room temperature prior to paraffin embedding and serial sectioning (transversely and longitudinally) at 7μm for hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Anatomical three-dimensional computer reconstructions were created from serial transverse sections utilizing SURF driver 3.5 software (SURF driver, University of Hawaii and University of Alberta). Sections were digitized to achieve linear tracings of relevant structures, including penis, clitoris, os penis, urethra, corpus cavernosum, and prepuce. Digital linear tracings from adjacent sections were serially aligned in sequence using Photoshop software (Adobe, Inc. San Rafael, CA 94903) and then exported into SURF driver for three-dimensional reconstruction.

Surface details were elucidated via scanning electron microscopy (SEM). External genitalia were dissected and fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde 0.1M sodium cacodylate buffer at pH 7.2 for 6 hours. The specimens were then post-fixed in 2% osmium tetraoxide for 2 hours, subsequently dehydrated in serial alcohol solutions and critical point dried in a Tousimis AutoSamdri 815 Critical Point Dryer (Tousimis, Rockville, MD). Specimens were then mounted on a stub with carbon tape, and images were obtained using a Hitachi TM-1000 Scanning Electron Microscope (Hitachi High Technologies America, Inc. Pleasanton, CA).

Results

Through comparison of the gross and microscopic anatomy of external genitalia of mice and broad-footed moles, it is possible to precisely and accurately define the various components that constitute the external genitalia of these species. Accordingly, we present objective criteria and descriptions of the anatomy of the penis, clitoris, phallus, prepuce, and preputial space of mice and moles as a basis for future studies of the endocrinology of sexual dimorphism.

The perineum of mice and broad-footed moles has a prominent appendage, which is of similar size in males and females, even though the perineal appendage is slightly larger in male mice and male broad-footed moles versus their female counterparts (Fig. 1). In the case of male mice and broad-footed moles, this perineal appendage is the prepuce based upon the following criteria: (a) The perineal appendage lacks erectile bodies, (b) does not contain a urethra, (c) is covered with a hair-bearing epidermis, and (d) defines a large space housing the penis lined with a stratified squamous glabrous (non-hair-bearing) epithelium (Fig. 2B & D). The epithelium lining the inner surface of the male prepuce reflects onto the penile surface deep within the preputial space and thus is continuous with penile surface epithelium (Fig. 3). The ducts of mouse preputial glands open onto the inner surface of the prepuce near the preputial meatus (not illustrated). Broad-footed moles lack preputial glands, but otherwise preputial anatomy of male mice and broad-footed moles is similar (Figs. 1-3).

Figure 1.

Side views of male and female broad-footed mole (A-C) and mouse (D & E) external genitalia. (F) External genitalia of the breeding season female broad-footed mole shown in (C), but at a ¾ side view showing the vaginal opening with forceps inserted. For both species the size of male and female external genitalia are remarkably similar. Red arrows in each panel denote the approximate level from which transverse sections in figure 2 were taken. For all images the cranial aspect is to the left.

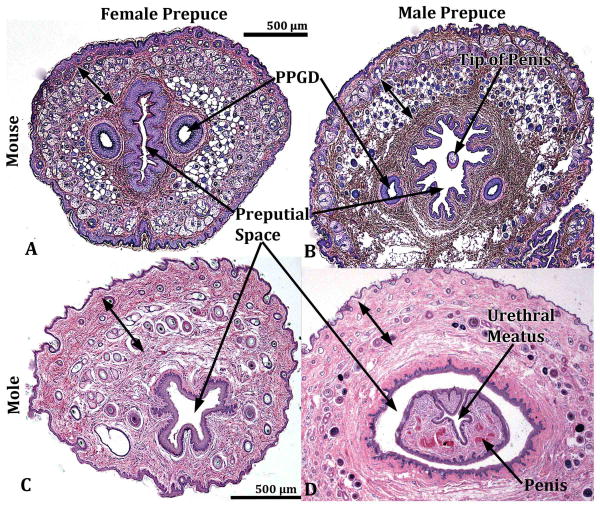

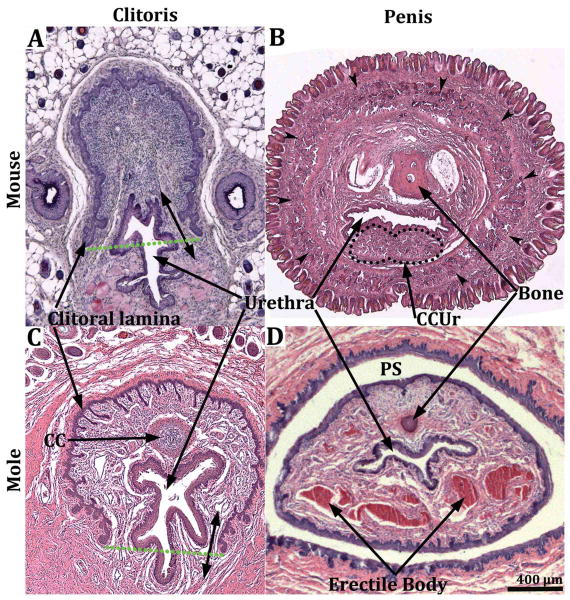

Figure 2.

Transverse sections of the external genitalia of male and female mouse (A & B) and broad-footed mole (C & D). See red arrows in figure 1 for the approximate level from which the sections were taken. The male and female perineal appendages illustrated grossly (Fig. 1) and in transverse sections (2A-D) are indicative of the prepuce by virtue of having the following features: (a) an absence of erectile bodies, (b) covered externally by a hair-bearing epidermis, (c) lined by a non-hair-bearing inner epithelium defining the preputial space, which in the case of males (B & D) houses the penis. Double-headed arrows denote hair follicles. Preputial gland ducts present in mice are labeled PPGD.

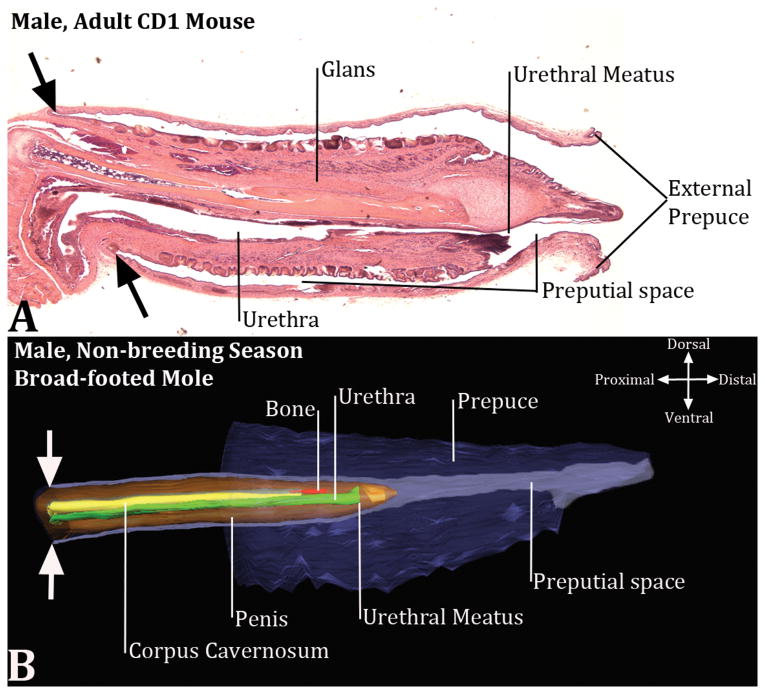

Figure 3.

Mid-sagittal section of the mouse penis (A) and a three dimensional reconstruction of the broad-footed mole external genitalia (B) and associated preputial space. Much of the mouse prepuce has been removed (A), but the fact that the mouse penis is housed within the preputial space is clearly evident. Note the continuity of the inner preputial epithelium with penile surface epithelium denoted by the large black arrows. (B) The three dimensional reconstruction of the broad-footed mole external genitalia, which also indicates that the penis is an “internal organ” housed within the preputial space. The large opposed white arrows in (B) indicate the junction between the external part of the penis that resides within the preputial space and the internal part of the penis that lies deep to the preputial space. In (B) red denotes the os penis, green denotes the urethra, orange denotes the penis, yellow denotes the corpus cavernosum, purple denotes prepuce and preputial space.

The perineal appendage (external genitalia) of female mice and broad-footed moles is the female prepuce (Fig. 1) in so far as the histology of the perineal appendage of female mice and moles is virtually identical to that of the male prepuce (Fig. 2). In female mice and broad-footed moles a stratified squamous epidermis bearing hair follicles covers the outer surface of the prepuce, while the inner surface of the prepuce defines a space (female preputial space) lined by a stratified squamous glabrous (non-hair-bearing) epithelium (Fig. 2A & C). Erectile bodies are absent in the female prepuce (Fig. 2A & C). The perineal appendage of female moles (Scapanus latimanus) are similar in size, gross morphology and histology during the breeding and non-breeding seasons (Fig. 1).

Morphometric analysis was performed to determine overall length of the perineal appendage (prepuce) of male (N=7) and female (N=6) moles by counting the number of 7μm sections from the distal preputial tip to the proximal point where the prepuce merges with the body wall. The prepuce of male moles averaged 3320μm in length (St. Dev.=371), while the female prepuce averaged 2717μm in length (St. Dev.=161) (Figs. 5 & 7). This difference was statistically significant (p=0.0405). The histologic section in which the distal tip of the penis or clitoris tissue first appeared was also noted. The distal tip of the penis first appeared at 1914μm (St. Dev.= 252) from the distal preputial tip, while the distal tip of the clitoris appeared at 1517μm (St.Dev. = 375) from the distal preputial tip (Figs. 5 & 7). Thus, in males the distal 58% (±4%) of the perineal appendage is comprised of prepuce only, and in female broad-footed moles 55% (±10%) of the perineal appendage is comprised of prepuce only. For both the penis and clitoris the inner preputial epithelium reflects onto the penile and clitoral surface proximal to the distal tips of these organs (Fig. 9).

Figure 5.

Diagrams demonstrating that the penis is an “internal” organ housed within the preputial space. (A) Side view of the adult mouse external prepuce with a colorized SEM image superimposed. The penis is in its typical position almost 2mm from the tip of the prepuce. (B) Drawing of the mouse external genitalia depicting the external prepuce. (C) Three dimensional reconstruction of the prepuce and penis of an adult broad-footed mole demonstrating the position of penis relative to the prepuce. As in the mouse, the mole penis at rest is an “internal” organ housed within the preputial space. The perineal appendage (prepuce) merges with the body surface (green asterisks). The red arrowheads denote the reflection of the inner preputial epithelium onto the surface of the penis. Note the morphometric measures mentioned in the text.

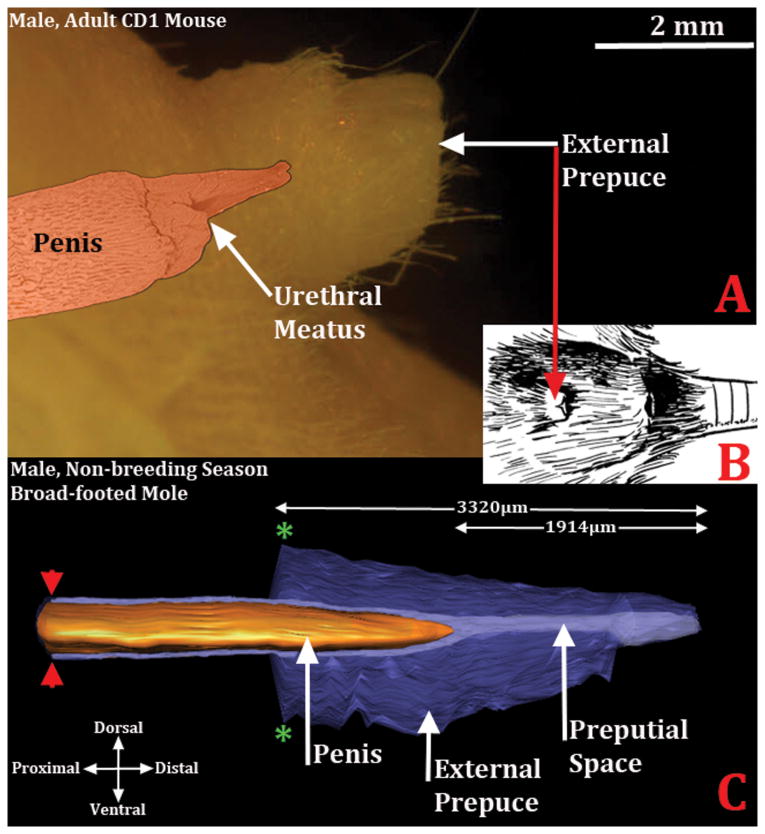

Figure 7.

Images demonstrating the “internal” position of the mouse (A) and broad-footed mole clitoris (E) as well as the changing position of the urethra in both species on a proximal/distal basis (B-D and F-H). In (A) a three dimensional reconstruction of the U-shaped clitoral lamina (blue) is superimposed on a side view of adult female mouse external genitalia. Sections B-D in proximal to distal order illustrate the changing position of the urethra relative to the clitoral lamina. Note also that sections (B & C) contain a stand-alone urethra. In (D) a complex epithelium is present in which the clitoral lamina and urethra are fused together. In (E), a three dimensional reconstruction of the broad-footed mole clitoris, the internal position of the clitoris in evident along with its color-coded internal constituents. In sections (F-H), taken at the positions so indicated, the stand-alone urethra is seen (F) as well as the preputial space (G) where the epithelium of the clitoral lamina and urethra are fused. (H) is a section through the female prepuce only showing the preputial groove. CC=corpus cavernosum.

Figure 9.

Drawings of the external genitalia of male and female rat, mouse, human and mole (Scapanus latimanus). The upper row depicts penises of the three species. The lower row contains mole (Scapanus latimanus) male and female drawings that are to morphometric scale as per the Results text. The mouse and the rat have two prepuces: (a) an external protective prepuce, which creates a voluminous space housing the penis and (b) an internal prepuce integral to the penis itself, which is similar to that of humans. The external prepuce creates the perineal appendage seen externally in both rats, mice and Scapanus latimanus. The arrangement of structures for Scapanus latimanus is similar to that of the mouse and rat with the exception of the absence of an internal prepuce. Note that in Scapanus latimanus the prepuce is non-integral to both the penis and clitoris.

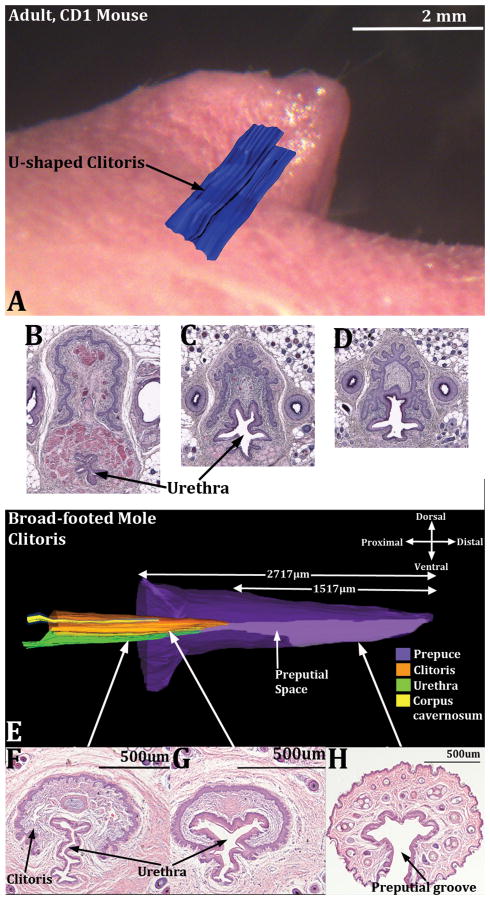

The clitoris of both mice and broad-footed moles is defined by a U-shaped clitoral epithelial lamina (Fig. 4A & C) (Martin-Alguacil et al., 2008a; Martin-Alguacil et al., 2008b; Martin-Alguacil et al., 2008c; Weiss et al., 2012) and is mostly located proximal to the female preputial space even though the distal aspect of the clitoris projects a short distance into the preputial space (Figs. 3, 5, 7 & 9). The fundamental difference between the penis (phallus) and the clitoris is that the penis is rod-like and is defined by a circumferential epithelium covering its surface (Figs. 2B & D, 4B & D, 8A). In contrast, the mouse and broad-footed mole clitoris is almost completely deep to the preputial space and is defined by a U-shaped clitoral epithelial lamina (Figs. 4A & C, 7B, C & F, 8B) (Martin-Alguacil et al., 2008a; Martin-Alguacil et al., 2008b; Martin-Alguacil et al., 2008c; Weiss et al., 2012). The anatomical differences between penis versus clitoris are so extreme that the terms, phallic-like clitoris, penile clitoris, and peniform clitoris are completely inappropriate in this mole species.

Figure 4.

Transverse sections of the clitoris of the mouse (A) and broad-footed mole (C) and the penis of the mouse (B) and broad-footed mole (D). The clitoris of both species is defined by a U-shaped clitoral epithelial lamina (A & C). The boundaries of clitoral stroma are defined by the clitoral epithelial lamina as well as the green dotted lines. In both species the female urethra is located partially within and partially outside of clitoral stroma. The extent of retention of the urethra within clitoral stroma is dependent upon the proximal/distal position of the section. In more proximal regions the urethra is completely ventral to clitoral stroma, which is the case for both mice and moles. Note the absence of defined erectile bodies within the mouse clitoris (A), and the presence of a corpus cavernosum (CC) located within the clitoral stroma of the broad-footed mole (C). The mouse and broad-footed mole penis is round to oval in shape, contains a urethra, and erectile bodies (double-headed arrows in [B] denote the corpus cavernosum glandis). The corpora cavernosa urethrae (CCUr) is highlighted by a dotted line. Note the network of blood filled cavernous spaces within the penis of the broad-footed mole (D). An os penis is present in both species.

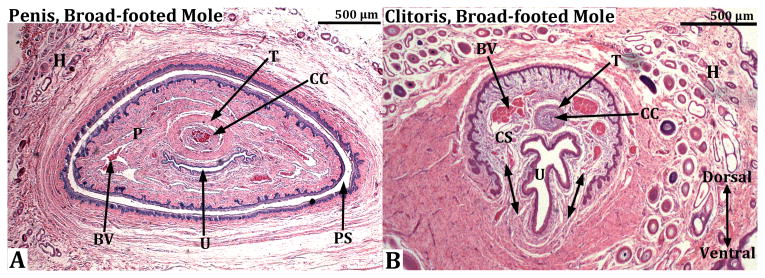

Figure 8.

Transverse sections through the penis (A) and clitoris (B) of an adult broad-footed mole. In (A) note that the penis (P) resides within the preputial space (PS) and contains the urethra (U), the corpus cavernosa (CC) surrounded by the tunica albuginea (T), and blood-filled spaces (BV). The os penis is not present at the level of this section. In (B) the U-shaped clitoral lamina partially surrounds the urethra (U). Residing within the space defined by the clitoral lamina is the corpus cavernosa (CC) surrounded by the tunica albuginea (T) and blood filled spaces (BV). Note that clitoral stroma (CS) within the U-shaped clitoral lamina is in continuity ventrally with the surrounding stroma (double-headed arrows). Finally, the substance of the preputial wall contains hair follicles (H) in both (A) and (B).

One of the distinctive anatomical features of mice and broad-footed moles is that the penis is an “internal” organ (Figs. 5 & 9), which at rest resides within the preputial space (Figs. 2B, 2D, 3, 4D, 8A & 9), even though during mating and presumably during urination the penis extends distally beyond the preputial meatus. Thus, penises of mice and broad-footed moles are not seen in external views of the perineum, but can be seen upon manual retraction of the prepuce. Penises of mice and broad-footed moles are divided into external and internal portions (Fig. 6). The external portion of the mouse and broad-footed mole penis is an appendage projecting from the body wall, housed within the voluminous preputial space (Figs. 2B, 2D, 3, 4D, 8A, 9) containing the urethra, erectile bodies, and in some species bone (os penis) (Rodriguez et al., 2011). The internal portion of the penis in both mice and moles lies deep to the body surface contour, and is constituted by attachments of erectile bodies to the pubic bones (Fig. 6) (Rodriguez et al., 2011). Thus, the penis and male prepuce are radically different anatomically and easily distinguished in both species. One defining penile feature of mice and broad-footed moles is that the external penile surface is covered by a stratified squamous epithelium, which in the case of the mouse is adorned by penile spines (Rodriguez et al., 2011), but is without spines in the case of Scapanus latimanus in both the non-breeding and breeding seasons (Figs, 2D, 4D, 8A). The penile surface epithelium is devoid of hair follicles in both mice and broad-footed moles (Figs. 2-4, 8). The penile urethra is completely surrounded by penile stroma (Figs. 4 & 8) and opens distally at the urethral meatus into the preputial space (Figs. 2D, 3, 5). Another unique feature of the penis of mice and broad-footed moles is the presence of well-defined erectile bodies. The external portion of the mouse penis, called the glans (Fig. 6), contains three erectile bodies: the MUMP corpora cavernosa (not illustrated), the corpus cavernosum urethrae, and the corpus cavernosum glandis (Figs. 4B) (Rodriguez et al., 2011). In broad-footed moles the penis contains a well-defined corpus cavernosum and an extensive diffuse network of blood sinus spaces (Figs. 4D & 8A). None of these features of penile anatomy are shared with the prepuce of male mice and broad-footed moles. Thus, for both male mice and broad-footed moles, the prominent perineal appendage is the hair-bearing male prepuce that creates the preputial space housing the internally situated penis.

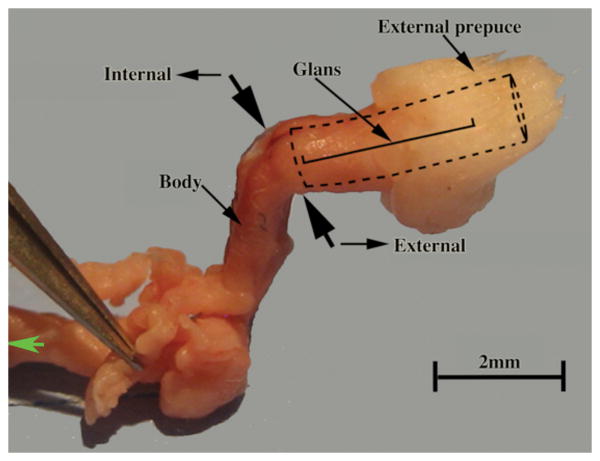

Figure 6.

Dissected prepuce and penis of the mouse. The two large opposed black arrows denote the junction between the external portion of the penis (glans) housed within the preputial space (as signified by the dotted lines) and the internal body of the penis lying deep to the preputial space. The position of the glans is illustrated.

The clitoris of mice and broad-footed moles (like the penis) is also an “internal organ” (Figs. 7 & 9) defined along most of its extent by a U-shaped epithelial lamina (Figs. 4A & 4C, 7, 8B) (Martin-Alguacil et al., 2008b; Weiss et al., 2012). Distinct erectile bodies are not present in the mouse clitoris (Figs. 4A & 7), while in broad-footed moles a distinct corpus cavernosum is present (Figs. 4C, 7E & 7F, 8B), which is similar to its counterpart in the penis of broad-footed moles (Fig. 8A). The clitoris of broad-footed moles also contains a diffuse network of blood sinus spaces (Figs. 4C & 8B).

While the description of rat external genitalia will be the subject of a future paper, preliminary gross and microscopic anatomical studies indicate that the arrangement of structures (external prepuce, internal prepuce and penis) are similar in the rat to that of the mouse. In both species the penis has an integral internal prepuce and is housed in a voluminous preputial space defined by the external prepuce that forms the perineal appendage (Fig. 9). A similar arrangement of structures is seen in the external genitalia of male broad-footed moles, with the exception of the absence of an internal prepuce (Fig. 9).

In summary, comparative anatomy and histology of external genitalia of mice and broad-footed moles have validated the remarkable similarity in preputial anatomy between these two species and have led to the conclusions (a) that the prepuce forms the perineal appendages of male and female mice (Mus musculus) and the broad-footed moles (Scapanus latimanus), (b) that the prepuce is non-integral to penis and clitoris, and (c) that the prepuce (external prepuce in the case of mice and rats) creates a space housing the penis and contains the distal tip of the clitoris. Accurate descriptions of anatomy of the mole external genitalia will facilitate ongoing analysis of endocrine parameters accounting for sexual dimorphism.

Discussion

External genitalia of most mammalian species exhibit substantial sexual dimorphism, and the various components of external genitalia (prepuce, penis, clitoris) are readily identifiable and accurately described for many species. Moles (this paper) and the spotted hyena (Cunha et al., 2014) are particularly interesting because the size of female external genitalia approaches that of males. Accordingly, these striking exceptions to the general rule of sexual dimorphism have attracted research interest and speculation as to how female external genitalia becomes masculinized. In the case of moles, there are 9 papers published over the period 1914 to 2008 on external genitalia. Seven of these contain descriptions or measurements of mole external genitalia. However measurements of “phallus” length were in reality measures of preputial length, the actual penis and clitoris residing within or deep to the preputial space. These studies on mole external genitalia have used a variety of terms to describe the prominent female perineal projection: “peniform clitoris”, “female urinary papilla”, “phallic like clitoris”, “phallus” and “penile clitoris”. Based upon re-evaluation using modern morphological techniques, it is now evident that the perineal appendage of male and female mice, rats and Scapanus latimanus (which lacks ovotestes) is the prepuce. Furthermore, the prepuce is non-integral to the penis and clitoris of these two species (Fig. 9). Unlike the human, the mouse, rat and mole (external) prepuce is surely not introduced into the vagina during mating, as the stiff preputial hairs projecting distally would surely prevent vaginal penetration. Thus, the penis of mice, rats and moles is a stand-alone structure capable of erection and presumably projects beyond the preputial meatus during urination and mating.

The mole clitoris, like that of the mouse, is defined by an inverted U-shaped epithelial lamina (Martin-Alguacil et al., 2008a; Martin-Alguacil et al., 2008b; Martin-Alguacil et al., 2008c; Weiss et al., 2012) and mostly lies deep to the preputial space. Unlike the mouse, the mole clitoris contains a corpus cavernosum, which is smaller but less vascularized than that of the mole penis. The mouse clitoris contains as os clitoridis, while the clitoris of Scapanus latimanus lacks as os clitoridis. Mice and Scapanus latimanus contain an os penis. In summary, the histological features distinguishing the penis and clitoris of Scapanus latimanus and mice are dramatically different from that of the prepuce, which forms the perineal appendage in both species.

As seen in 3D reconstructions of serial sections of the mole (Scapanus latimanus, which lacks an ovotestis), the clitoris is deeply placed with only its distal tip projecting into the preputial space (Figs. 7 & 9), an arrangement also seen in mice. Moreover, the mole clitoris and the prepuce are non-integral entities. Future studies are required to determine if mole species possessing the ovotestes have a more masculine clitoris worthy of the term penile clitoris.

The original publications on mole external genitalia by Wood-Jones and Matthews dealt with a European species (Talpa europaea), which was followed by several other reports also on European mole species. Thus, the question arises as to whether our observations on a North American mole (Scapanus latimanus) are relevant to European moles. Unfortunately, Talpa europaea was not available for our analysis. Remarkably, three North American moles species that we have examined (Scapanus latimanus, Condylura cristata and Parascalops breweri) exhibit masculinization of their external genitalia virtually identical to that of Talpa europaea, suggesting that the detailed morphology (and the conclusions drawn) presented herein is relevant to both North American and European moles (Sinclair, unpublished).

Of the 7 reports dealing with the morphology of mole external genitalia, all contain or perpetuate anatomical mis-interpretations to varying degrees in regard to terminology of male and female perineal appendages as mentioned above. We have carefully scrutinized these 7 papers and compared the terminology used with the revised terminology of the current paper (Table 1). Our re-evaluation of the anatomy of mole external genitalia will surely facilitate a standardized terminology for future studies.

Table 1. Review of the literature on mole external genitalia.

| Author | Descriptive term for Prepuce | Focus | Sex | Features Observed: Prepuce, internal structures of penis/clitoris or both | Used “received wisdom”. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wood-Jones (1914) | clitoris & penis | ExG, gonads, & internal UG organs | M&F | Prepuce, internal UG organs, gonads, | N/A |

| Matthews (1935) | clitoris, penis & peniform clitoris | ExG, gonads, & internal UG organs | M&F | Prepuce, ovary, testis, & internal reproductive organs | Used “received wisdom” and references Wood-Jones with the statement, “the clitoris is remarkably like the penis but slightly smaller” |

| Gorman and Stone (1990) | female urinary papilla | ExG & gonads | M&F | Prepuce, ovotestes, testes, vagina | Used “received wisdom” and refers to “female urinary papilla” resembling penis of male. Quotes Matthews “that all moles are male until 1 year old”. |

| Whitworth et al (1999) | clitoris, phallus, phallic-like clitoris | Ovotestes & ExG | M&F | Ovotestes, testes, prepuce, ExG | Used “received wisdom” and showed gross image of male and female ExG labeled clitoris and phallus. Used term “phallic-like clitoris”. |

| Zurita et al (2003) | penile clitoris | Sex duct development, AMH gene, testosterone levels | M&F | Mullerian and Wolffian ducts | Used “received wisdom” and was first use of term “penile clitoris” |

| Rubenstein et al (2003) | phallus & peniform clitoris | Ovary & ExG | M&F | Ovary, testes, prepuce, penis, clitoris | Used “received wisdom”. Showed images of ExG, and transverse histologic sections of penis, clitoris and prepuce. Measured prepuce length and designated it “Phallus length”. Also used the term, “peniform clitoris”. |

| Carmona et al (2008) | peniform clitoris | Ovotestes & Exg | F | Ovary/ovotestes, female prepuce | Used “received wisdom”. Showed gross images of female ExG, used term, “peniform clitoris” |

Abbreviations: ExG=external genitalia, UG=urogenital, AMH=anti-Mullerian duct hormone, M=male, F=female

While confusion concerning the anatomy and terminology of mole external genitalia has a history of ∼100 years, it is perhaps worth noting that drawings of male and female “External Genitalia” in the “Anatomy of the Laboratory Mouse” website (http://www.informatics.jax.org/cookbook/) also lack precision in that the male prepuce is incorrectly labeled “penis” and female prepuce is labeled “urethral orifice”. The current study demonstrates that the perineal appendages in male and female mice, rats and broad-footed moles are hair-bearing male and female prepuces completely lacking in erectile bodies, features unique and specific to the penis and in some species to the clitoris as well. Inappropriate interpretation of anatomical features of external genitalia are not restricted to ancient mole literature, but is also found in our recent publication on moles (Rubenstein et al., 2003) in which the terms “phallus' and “peniform clitoris” were applied to female external genitalia. The term “phallus”, which has been applied to the prepuce of male and female moles, is clearly incorrect since the definition of phallus is penis according to Dorland's Medical Dictionary.

The prepuce in mice (and presumably in moles) develops from the preputial swellings. Preputial swellings appear as secondary lateral outgrowths of the ambisexual male and female genital tubercles. The preputial swellings grow ventrally and fuse in the ventral midline to form the prepuce (Perriton et al., 2002). The prepuce, thus formed, grows distally to completely cover the genital tubercle, thus rendering the penis and clitoris as “internal organs” whose distal tips in adulthood are situated a considerable distance from the apex of the prepuce as seen in figures 3, 5, 7 and 9 (Baskin et al., 2002; Weiss et al., 2012). This developmental sequence is consistent with the adult perineal appendage being prepuce and the penis and clitoris being internal organs.

While gross views of male and female external genitalia typically reveal distinct sexual dimorphism as is the case for humans, photographs depicting external genitalia of male and female mice and broad-footed moles are remarkably similar, respectively (Fig. 1), while in humans the absolute size and anatomy of the penis and clitoris are dramatically different. This substantial size difference in humans also applies to the human penile prepuce and the prepuce of the clitoris (Clemente, 1985). In contrast, size and anatomy of the perineal appendages (prepuce) in male and female mice and broad-footed moles are remarkably similar. This situation also applies to rats, and we suspect to many other rodent-like species. This raises the question as to whether this pattern of similarly sized external genitalia (prepuce) in rodent-like species was selected through evolution. Recent studies of mouse external genitalia indicate that the male mouse actually has 2 prepuces (Blaschko et al., 2013). The male mouse perineal appendage, which houses the penis, is called the external prepuce. The male mouse internal prepuce is a fold of skin integral to the distal aspect of the penis and encircling it, similar to the human prepuce (Blaschko et al., 2013). In similar fashion, the rat also has both an external and an internal prepuce (Fig. 9). The external prepuce of laboratory mice (and perhaps all mouse species) provides a voluminous space housing and protecting the penis and ensuring its cleanliness. This arrangement appears ideal for rodent-like animals (including moles) built low to the ground and is certainly also the case for rats.

The female ring-tailed lemurs and the spotted hyenas are two additional species renown for profound masculinization of the external genitalia, which raises the question of the correct anatomical terminology applicable to these two species. In the case of the spotted hyena, terms such as penile clitoris or peniform clitoris are fully justified as the pendulous clitoris is derived directly from the genital tubercle of the embryo, is rod-like in morphology, is circular in transverse section, is traversed by a central canal which conveys urine to the exterior, contains erectile bodies, is capable of erections, and is adorned distally by a prepuce integral to the clitoris (Matthews, 1939; Cunha et al., 2003; Cunha et al., 2005; Glickman et al., 2006; Cunha et al., 2014). The prominent perineal appendage of the female ring-tailed lemur has also been called a pendulous external clitoris similar to that of the spotted hyena (Drea and Weil, 2008). Even though histological analysis was not used to arrive at this designation, the data in support of this conclusion are convincing.

Finally, Table 2 presents the salient features of the penis, clitoris, as well as male and female prepuces of mice and the broad-footed moles. It is evident that the flaw common in previous literature on mole external genitalia stems from mis-identification of the prepuce using such terms as: peniform clitoris, female urinary papilla, phallus-like clitoris, phallus and penile clitoris. This mis-interpretation is due in large part to the lack of adequate histological examination of adult mole external genitalia. Understanding that the clitoris is an “internal” organ defined by a U-shaped clitoral lamina in both mice and broad-footed moles leaves no room for attributing penile features to this clearly non-penile organ.

Table 2. Anatomical features defining male and female external genitalia of mice and broad-footed moles.

| Structure | Anatomical features |

|---|---|

| Penis |

|

| Male prepuce |

|

| Female prepuce |

|

| Clitoris |

|

| Preputial space |

|

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the following grants: NSF Grant IOS-0920793 and NIH grant RO1 DK0581050.

Abbreviations

- MUMP

male urogenital mating protuberance

- SEM

scanning electron microscopy

- St. Dev

standard deviation

References

- Baskin LS, Liu W, Bastacky J, Yucel S. Anatomical studies of the mouse genital tubercle. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2002;545:103–148. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8995-6_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaschko SD, Mahawong P, Ferretti M, Cunha TJ, Sinclair A, Wang H, Schlomer BJ, Risbridger G, Baskin LS, Cunha GR. Analysis of the effect of estrogen/androgen perturbation on penile development in transgenic and diethylstilbestrol-treated mice. Anatomical record. 2013;296:1127–1141. doi: 10.1002/ar.22708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona FD, Motokawa M, Tokita M, Tsuchiya K, Jimenez R, Sanchez-Villagra MR. The evolution of female mole ovotestes evidences high plasticity of mammalian gonad development. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2008;310:259–266. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente CD, editor. Gray's Anatomy. 13th. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha GR, Place NJ, Baskin L, Conley A, Weldele M, Cunha TJ, Wang YZ, Cao M, Glickman SE. The ontogeny of the urogenital system of the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta Erxleben) Biol Reprod. 2005;73:554–564. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.041129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha GR, Risbridger G, Wang H, Place NJ, Grumbach M, Cunha TJ, Weldele M, Conley AJ, Barcellos D, Agarwal S, Bhargava A, Drea C, Siiteri PK, Coscia EM, McPhaul MJ, Hammond GL, Baskin LS, Glickman SE. Development of the External Genitalia: Perspectives from the Spotted Hyena (Crocuta crocuta) Differentiation; research in biological diversity. 2014;87:4–22. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha GR, Sinclair A, Risbridger G, Hutson J, Baskin LS. Current understanding of hypospadias: relevance of animal models. Nature reviews Urology. 2015;12:271–280. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2015.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha GR, Wang Y, Place NJ, Liu W, Baskin L, Glickman SE. Urogenital system of the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta Erxleben): A functional histological study. J Morphol. 2003;256:205–218. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangoor D, Giladi E, Fridkin M, Gozes I. Neuropeptide receptor transcripts are expressed in the rat clitoris and oscillate during the estrus cycle in the rat vagina. Peptides. 2005;26:2579–2584. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drea CM. Sex and seasonal differences in aggression and steroid secretion in Lemur catta: are socially dominant females hormonally ‘masculinized’? Horm Behav. 2007;51:555–567. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drea CM, Weil A. External genital morphology of the ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta): females are naturally “masculinized”. J Morphol. 2008;269:451–463. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickman SE, Cunha GR, Drea CM, Conley AJ, Place NJ. Mammalian sexual differentiation: lessons from the spotted hyena. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006;17:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman ML, Stone RD. The natural history of moles. Ithaca: Comstock Publishing Associates; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Homburger F, Forbes I, Desjardins R. Renotropic effects of some androgens upon experimental hydronephrosis and upon the clitoris in the mouse. Endocrinology. 1950;47:19–25. doi: 10.1210/endo-47-1-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez R, Burgos M, Sanchez A, Sinclair AH, Alarcon FJ, Marin JJ, Ortega E, Diaz de la Guardia R. Fertile females of the mole Talpa occidentalis are phenotypic intersexes with ovotestes. Development. 1993;118:1303–1311. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.4.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korenbrot CC, Huhtaniemi IT, Weiner RI. Preputial separation as an external sign of pubertal development in the male rat. Biol Reprod. 1977;17:298–303. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod17.2.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Alguacil N, Pfaff DW, Shelley DN, Schober JM. Clitoral sexual arousal: an immunocytochemical and innervation study of the clitoris. BJU Int. 2008a;101:1407–1413. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Alguacil N, Schober J, Kow LM, Pfaff D. Oestrogen receptor expression and neuronal nitric oxide synthase in the clitoris and preputial gland structures of mice. BJU Int. 2008b;102:1719–1723. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Alguacil N, Schober JM, Sengelaub DR, Pfaff DW, Shelley DN. Clitoral sexual arousal: neuronal tracing study from the clitoris through the spinal tracts. The Journal of urology. 2008c;180:1241–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews L. Reproduction of the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta Erxleben) Phil Tran Roy Soc, Lond B. 1939;230:1–78. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews LH. The oestrous cycle and intersexuality in the female mole (Talpa europea Linn) Proc Zool Soc, London, Series B. 1935;230:347–383. [Google Scholar]

- Mossman HW, Duke KL. Comparative morphology of the mammalian ovary. 1973:461. [Google Scholar]

- Perriton CL, Powles N, Chiang C, Maconochie MK, Cohn MJ. Sonic hedgehog signaling from the urethral epithelium controls external genital development. Developmental biology. 2002;247:26–46. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purinton PT, Fletcher TF, Bradley WE. Innervation of pelvic viscera in the rat. Evoked potentials in nerves to bladder and penis (clitoris) Investigative urology. 1976;14:28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez E, Jr, Weiss DA, Yang JH, Menshenina J, Ferretti M, Cunha TJ, Barcellos D, Chan LY, Risbridger G, Cunha GR, Baskin LS. New insights on the morphology of adult mouse penis. Biol Reprod. 2011;85:1216–1221. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.091504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein NM, Cunha GR, Wang YZ, Campbell KL, Conley AJ, Catania KC, Glickman SE, Place NJ. Variation in ovarian morphology in four species of New World moles with a peniform clitoris. Reproduction. 2003;126:713–719. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1260713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss DA, Rodriguez E, Jr, Cunha T, Menshenina J, Barcellos D, Chan LY, Risbridger G, Baskin L, Cunha G. Morphology of the external genitalia of the adult male and female mice as an endpoint of sex differentiation. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2012;354:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh M, MacLeod DJ, Walker M, Smith LB, Sharpe RM. Critical androgen-sensitive periods of rat penis and clitoris development. International journal of andrology. 2010;33:e144–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2009.00978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth DJ, Licht P, Racey PA, Glickman SE. Testis-like steroidogenesis in the ovotestis of the European mole, Talpa europaea. Biol Reprod. 1999;60:413–418. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.2.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood-Jones F. Some phases in the reproductive history of the female Mole (Talpa europea) Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London??? 1914:191–216. [Google Scholar]

- Yang JH, Menshenina J, Cunha GR, Place N, Baskin LS. Morphology of mouse external genitalia: implications for a role of estrogen in sexual dimorphism of the mouse genital tubercle. The Journal of urology. 2010;184:1604–1609. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurita F, Barrionuevo FJ, Berta P, Ortega E, Burgos M, Jimenez R. Abnormal sex-duct development in female moles: the role of anti-Mullerian hormone and testosterone. Int J Dev Biol. 2003;47:451–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurita F, Carmona FD, Lupianez DG, Barrionuevo FJ, Guioli S, Burgos M, Jimenez R. Meiosis onset is postponed to postnatal stages during ovotestis development in female moles. Sexual development : genetics, molecular biology, evolution, endocrinology, embryology, and pathology of sex determination and differentiation. 2007;1:66–76. doi: 10.1159/000096240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]