Abstract

Background

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) are a delivery and payment model aiming to coordinate care, control costs, and improve quality. Medicare ACOs are responsible for eight measures of preventive care quality.

Objectives

To create composite measures of preventive care quality and examine associations of ACO characteristics with performance.

Design

Cross-sectional study of Medicare Shared Savings Program and Pioneer participants. We linked quality performance to descriptive data from the National Survey of ACOs. We created composite measures using exploratory factor analysis, and used regression to assess associations with organizational characteristics.

Results

Of 252 eligible ACOs, 246 reported on preventive care quality, 177 of which completed the survey (response rate=72%). In their first year, ACOs lagged behind PPO performance on the majority of comparable measures. We identified two underlying factors among eight measures and created composites for each: disease prevention, driven by vaccines and cancer screenings, and wellness screening, driven by annual health screenings. Participation in the Advanced Payment Model, having fewer specialists, and having more Medicare ACO beneficiaries per primary care provider were associated with significantly better performance on both composites. Better performance on disease prevention was also associated with inclusion of a hospital, greater electronic health record capabilities, a larger primary care workforce, and fewer minority beneficiaries.

Conclusions

ACO preventive care quality performance is related to provider composition and benefitted by upfront investment. Vaccine and cancer screening quality performance is more dependent on organizational structure and characteristics than performance on annual wellness screenings, likely due to greater complexity in eligibility determination and service administration.

Keywords: preventive care, accountable care organizations, quality performance

INTRODUCTION

The role of preventive care in medicine and coverage of such services have shifted dramatically in the last decade. Prior to 2005, Medicare did not cover visits focused on health promotion or disease prevention.1 More recently, however, prevention has become a national priority. Amidst growing evidence of potential increases in life-years associated with preventions,2 the Affordable Care Act abolished patient cost sharing for all preventive services.3 Despite progress, no preventive care quality measure exceeded 85% in national completeness in 2013.4 Furthermore, there is widespread variation in performance, not only from provider to provider, but also from measure to measure for individual providers.5–7 Prior research has suggested that the more coordinated networks of Health Maintenance Organizations outperform traditional fee-for-service coverage plans on utilization of preventive visits8 and on preventive care quality.4,9,10 Several reasons may account for these findings, including (1) preventive services require repeated and regular provision to many or all patients, (2) they require interaction with the health care system even in the absence of any health problems, and (3) documentation requirements and provision by disparate providers complicate data abstraction and compilation.

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) were developed as a novel payment model to create a coordinated health system whereby providers contract together to take collective responsibility for managing the cost and quality of care for a population of patients.11 The model is purposefully flexible, allowing independent providers the freedom to experiment with innovative strategies for success.12 ACOs are particularly well positioned to execute on preventive care quality through coordinated care management and data collection,13 but we are only beginning to understand their taxonomy, strategic choices, and early performance.14,15 Some of the first ACOs emerged in 2012 through two Medicare programs: the Pioneer ACO Model and the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP). The Pioneer program was designed for more experienced and coordinated health systems as it involved higher level of risk and reward than the MSSP. Since 2012, numerous private insurers and Medicaid programs following suit with similar contracts.16 Indeed, 8 of the 33 quality measures for Medicare ACOs are related to prevention, including vaccinations and screenings.17,18 These measures directly impact the financial success of ACOs through contract incentives tying shared savings to performance.19,20 The remaining quality measures assess patient experience, chronic disease management, and care coordination domains. As most others are related to clinical outcomes (e.g. satisfaction, diabetic Hemoglobin A1c control, readmission rate), we posit that the process measures of preventive care are among the least complex, with simple eligibility rules, and brief and inexpensive service administration required for performance relative to other measures. Given the ACO program’s innovative and diverse structure, understanding patterns of variation in and drivers of preventive care quality performance represents an opportunity to inform continued improvement of quality management processes, for ACOs and other emerging quality-based contracts.

In this study, we used factor analysis to identify subgroups of, and generate composites for related quality measures among the eight preventive care quality measures for which Medicare ACOs are responsible, and then examined associations of higher composite quality performance with descriptive survey data on organizational characteristics. Ultimately, we aim to inform ACO strategies for execution on preventive care quality.

METHODS

We conducted a cross-sectional study examining Medicare ACO preventive care quality performance and describe associations with ACO characteristics from the National Survey of ACOs. We executed exploratory factor analysis to describe patterns of preventive care quality performance and collapse eight reported measures into a smaller set of composite measures. We then used linear regression to study associations of composite performance with ACO characteristics.

Data

We drew on two sources of data: (1) quality performance and limited descriptive data for Medicare ACOs publicly available from The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS),21–23 and (2) data from the National Survey of ACOs (NSACO) describing ACO composition, characteristics, and capabilities. We tested for response bias by comparing survey respondents with non-respondents on CMS data, and assessed the comparability of Medicare ACOs with average preventive care quality across the eight measures, above versus below the national mean, using t-tests and χ2 tests for significance.

Study Sample

For factor analysis of preventive care quality, we included all Medicare ACOs that reported on all preventive care measures in performance year one: 2012 for Pioneers, and 2013 for MSSPs (see Text Document: Methods Appendix, Supplemental Digital Content 1, detailed eligibility and sample description). For regression analysis, we used the subset of these Medicare ACOs that completed the NSACO in waves 1 or 2, which surveyed all ACOs created prior to August 2013 and was completed prior to the end of the first performance year in all cases.

ACO Characteristics

The NSACO targeted a senior administrator as the respondent. The survey is composed of several domains, including ACO background, contracts, leadership, structure, and capabilities; details of survey content and administration are published elsewhere.24 We a priori identified survey questions that we hypothesized to be related to preventive care quality performance in one of five conceptual groups: (1) beneficiary composition, (2) provider composition, (3) general characteristics, (4) electronic health record (EHR) capabilities, and (5) quality management capabilities. Additionally, descriptive characteristics of the beneficiaries and providers publicly reported by CMS for MSSPs were merged with survey data.23 We used dichotomous variables to indicate presence of characteristics, as well as continuous variables for counts (e.g. of providers) and likert-like descriptions of extent of capabilities (e.g. for Electronic Health Records). Additionally, we tested for non-linear relationships by considering quartile categorical indictors in place of continuous variables (see Text Document: Methods Appendix, Supplemental Digital Content 1).

Preventive Care Quality Performance

CMS publishes quality performance data for all Medicare ACOs on each of 33 measures, including eight related to preventive care.21,22 Each measure is scored as the percent of eligible patients receiving the indicated service in a given year, on a 0 to 100 point scale. Eligibility definitions and performance requirements are detailed elsewhere.18 Of the 252 eligible Medicare ACOs with performance year one in 2012 or 2013, 246 reported on preventive care quality performance. Quality performance data was available only for Medicare ACOs, and, thus, other NSACO respondents were not included in the study.

Composite Measure Creation

We sought to identify common themes in performance, or subsets of preventive care quality measures that tend to vary together. To this end, we executed exploratory factor analysis on the eight measures for Medicare ACOs, both for all reporting ACOs (n=246) and for the subset of NSACO respondents (N=177). Generated factors were tested for significance by parallel analysis, and then obliquely rotated to emphasize the components most strongly driving each. In addition to predicting factor scores, we calculated averages of the component measures with high loading (>0.4) for each factor (see Text Document: Methods Appendix, Supplemental Digital Content 1). We chose to present factor averages as primary dependent variables, as coefficients remain on the same 0–100 point scale of the original component measures.

Statistical Analysis

We examined associations between preventive care quality performance and various attributes of Medicare ACOs, as described by responses to survey questions and CMS descriptive data on attributed beneficiaries. We used linear regression to study relationships between composite quality performance and ACO characteristics, and created multivariate models for each underlying factor. Models were built around the five conceptual groups of variables, examining alternative variable representations and checking for correlations and interactions between variables. As our study was exploratory, we favored models that best balanced explanatory power with parsimony (adjusted R2 and F-statistic) and significance of included variables (P values). We tested the sensitivity of our results to model composition by (1) eliminating and exchanging independent variables to increase the included sample size and assess consistency in the observed relationships, and (2) using the factor score and the original quality measures as dependent variables to confirm validity of factor analysis methodology (see Text Document: Methods Appendix, Supplemental Digital Content 1). All analyses were performed using STATA version 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Survey Respondents

The 6 ACOs failing to report on preventive care quality measures were all MSSP participants (not Pioneer participants), smaller on average (6,596 vs. 16,989 beneficiaries; p=.10), and had significantly higher average proportion minority beneficiaries (33% vs. 15%, p=.008). Of 246 reporting ACOs, 177 completed the NASCO (response rate=72%). Survey respondents were not significantly different from non-respondents in terms of beneficiary or provider compositions, or overall average quality, but did differ on certain quality measures, including significantly higher performance by respondents on the disease prevention composite (see Table S.1, Supplemental Digital Content 3, comparison of respondents to non-respondents).

Baseline characteristics of respondents, stratified into high and low performers relative to average national performance across the eight measures, are presented in Table 1. Compared to low performers, high performers had significantly fewer full-time equivalent (FTE) specialist providers, were more likely to be MSSP rather than Pioneer participants, more likely to be a participant in the Advanced Payment Model, and had a higher ratio of attributed beneficiaries to FTE primary care providers (PCPs).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Medicare Accountable Care Organizations (ACO) Survey Respondents (n=177), by high and low performance relative to the national mean quality score across the eight preventive care measuresa

| High Performers (n=90) | Low Performers (n=87) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or % | Mean (SD) or % | P value | |

| Provider Composition | |||

| FTE Primary Care Providers (PCPs) | 133 (166) | 176 (164) | .10 |

| FTE Specialist Providers | 149 (210) | 320 (426) | .001 |

| Percent of Providers Employed by ACO | 39.2 (44.2) | 28.3 (37.2) | .10 |

| Percent of Providers that are PCPs | 58.8 (28.0) | 53.8 (27.5) | .26 |

| Attributed ACO beneficiaries per FTE PCPc | 212 (115) | 158 (85) | .002 |

| Beneficiary Composition | |||

| Estimated ACO beneficiaries | |||

| < 10,000 | 42.7% | 42.0% | |

| 10,000–20,000 | 37.8% | 33.3% | .86 |

| 20,000–50,000 | 15.9% | 19.8% | |

| > 50,000 | 3.7% | 4.9% | |

| Attributed ACO beneficiariesc | 17,300 (16,600) | 16,200 (12,300) | .63 |

| Percent Minority beneficiariesc | 14.7 (14.7) | 16.9 (16.5) | .32 |

| Percent Dual-Eligible beneficiariesc | 8.5 (11.3) | 8.9 (12.8) | .83 |

| General Characteristics | |||

| Inclusion of Hospital | 53.9% | 53.1% | .92 |

| Inclusion of Outpatient Pharmacy | 40.7% | 33.7% | .35 |

| Inclusion of Community Health Center | 26.8% | 28.1% | .86 |

| Integrated Delivery System | 54.3% | 50.0% | .58 |

| Physician Leadership | 60.0% | 58.6% | .85 |

| Joint Physician/Hospital Leadership | 31.1% | 29.9% | .86 |

| Contract Type | |||

| Pioneer | 10.0% | 19.5% | |

| MSSP 2012 | 64.4% | 37.9% | .002 |

| MSSP 2013 | 25.6% | 42.5% | |

| Number of ACO Contracts | 1.80 (1.26) | 2.03 (1.45) | .25 |

| Medicare Advanced Payment Model Participant | 19/90 (21.1) | 9/87 (10.3) | .05 |

| Electronic Health Record Capabilities | |||

| EHR Capability Indexd | 0.775 (0.179) | 0.754 (0.178) | .47 |

| 3 point chronic disease/prevention tracking | 2.29 (0.69) | 2.30 (0.71) | .95 |

| 3 point electronic specialty referrals | 2.11 (0.75) | 2.09 (0.74) | .84 |

| 3 point electronic patient reminders | 2.23 (0.73) | 2.11 (0.72) | .27 |

| Quality Management Capabilities | |||

| ACO experience with Pay-for-Performance | 20.6% | 26.0% | .43 |

| ACO experience with public quality reports | 26.3% | 20.3% | .38 |

| 3 point clinician Quality Improvement training | 2.08 (0.73) | 1.99 (0.80) | .47 |

| 3 point quality monitoring and physician feedback | 2.47 (0.64) | 2.38 (0.65) | .34 |

| Financial Performance | |||

| Benchmark expenditures (in millions $) | 228 (252) | 168 (117) | .07 |

| Savings (+) or losses (−) per beneficiary (in $) | 106 (1110) | −58 (551) | .26 |

| Reached shared savings | 32.2% | 20.7% | .08 |

FTE= Full-time equivalent; PCP = primary care provider; EHR = electronic health record

For continuous and ordinal categorical variables, mean (standard deviation) presented and p-value by t-test; for dichotomous and categorical variables, % of respondents with the characteristic presented, p-value by chi-squared test.

High and low performers dichotomized by the average quality score of the ACO across the eight measures being above, or below the national mean of these average scores across all 246 Medicare ACOs successfully reporting on all eight measures (mean = 60.74 points).

Variable derived using CMS data available only for MSSP ACOs (n=151).

EHR capability index (minimum of 0, maximum of 1) is assessed from survey responses to seven questions on potential capabilities of EHR systems, including the three selected measures presented subsequently.

Preventive Care Quality and Composite Measure Creation

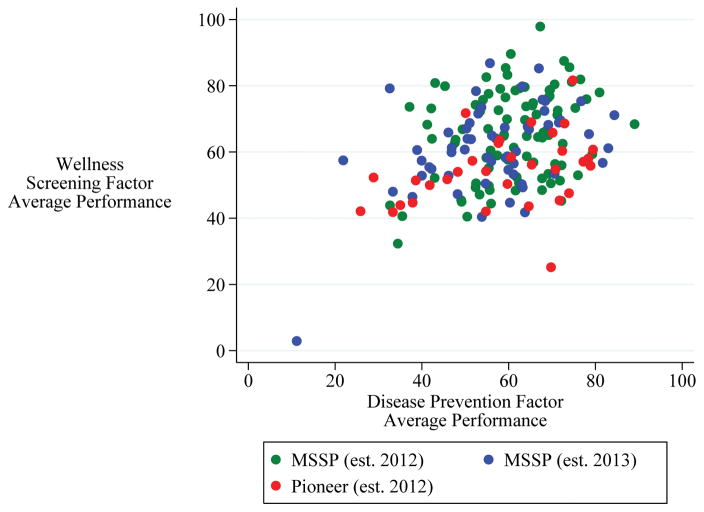

In their first year, Medicare ACOs failed to match performance of Medicare PPOs on four of five measures with comparable published estimates from the National Committee on Quality Assurance.4 Individual ACOs exhibited high variation in performance across the eight preventive care measures, with average standard deviation of 21 points (Table 2). Exploratory factor analysis identified two statistically significant underlying factors of preventive care quality performance, and results were robust to including all reporting Medicare ACOs versus limiting to the subset of NSACO respondents. Factor 1, henceforth “disease prevention,” had significant loading from the two vaccination measures (influenza and pneumococcus) and the two cancer screening measures (colon and breast). Factor 2, henceforth “wellness screening,” had significant loading from the four basic health screening measures (BMI, tobacco use, depression, and blood pressure). We averaged component measures with high loading (>0.4) for each factor to create the two composite measures. Performance on the two factor averages was significantly and positively correlated (rPearson’s=0.40; p<.001) (Figure 1; see Text Document: Results Appendix, Supplemental Digital Content 2).

Table 2.

Preventive care quality performance measures for Medicare ACOs

| Medicare PPO Performancea | Medicare ACO Performance | Rotated Factor Loadings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Measure | Mean | Mean (SD) | Interquartile Range | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

| Disease Prevention | |||||

| Influenza Vaccine | NR | 56.0 (14.6) | 45.6 – 66.7 | 0.68 | 0.20 |

| Pneumococcus Vaccine | 71.7 | 54.6 (19.4) | 42.3 – 68.4 | 0.92 | −0.08 |

| Colon Cancer Screen | 60.8 | 59.2 (13.7) | 50.8 – 69.0 | 0.82 | 0.04 |

| Breast Cancer Screen | 69.1 | 62.1 (12.8) | 54.3 – 71.0 | 0.64 | 0.15 |

| Wellness Screening | |||||

| Body Mass Index Screen | 84.9 | 61.2 (16.0) | 49.3 – 73.6 | 0.05 | 0.73 |

| Tobacco Screen/Counseling | 80.4 | 83.8 (14.8) | 78.3 – 93.2 | 0.35 | 0.46 |

| Depression Screen | NR | 29.4 (23.9) | 8.0 – 46.5 | 0.20 | 0.50 |

| Blood Pressure Screen | NR | 74.7 (22.8) | 59.1 – 92.9 | −0.40 | 0.51 |

| Composite Measure | Internal Consistency (Cronbach’s α) | ||||

| Disease Prevention Averageb | 58.0 (13.1) | 49.9 – 68.0 | 0.874 | ||

| Wellness Screening Averagec | 62.2 (13.4) | 52.8 – 71.6 | 0.604 | ||

| Overall Average | 60.1 (11.1) | 53.3 – 68.2 | 0.773 | ||

2013 National Center for Quality Assurance “2014 State of Health Care Quality Report” mean performance for Medicare PPO plans, overall sample represents voluntary reporting by health plans on quality measures for 171 million Americans (54% of population), including 353 PPOs.8 NR = not reported

Average of influenza vaccine, pneumococcus vaccine, colon cancer screen, and breast cancer screen measures (those with >0.4 loading on Factor 1)

Average of body mass index screen, tobacco screen/counseling, depression screen, and blood pressure screen measures (those with >0.4 loading on Factor 2)

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of Medicare ACO preventive care quality average performance on disease prevention factor measures (influenza and pneumococcal vaccines, breast and colon cancer screenings) and wellness screening factor measures (body mass index, depression, blood pressure, and tobacco screenings), by participant type.

Regression Analysis

Preferred multivariate models for disease prevention and wellness screening factor averages are presented in Table 3, alongside selected sensitivity analyses with variations in included variables and sample size. Included sample size fell in multivariate models due to varying question non-response, but remained at or above 65% in our preferred models. All reported coefficients are on the 0–100 point scale of the original measures, with a higher score indicating better performance. Additionally, we present regression-adjusted means for performance from the same preferred models in Figure 2, varying presence or absence of dichotomous characteristics, and mean levels of the top quartile to bottom quartile of continuous characteristics.

Table 3.

ACO characteristics associated with (A) disease prevention factor averagea quality performance, and (B) wellness screening factor averageb quality performance

| A.) Disease Prevention | Modelc | Preferred | Expanded | Reduced | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 115 | 104 | 132 | ||||

| F-Statistic | 10.50 | 10.24 | 8.77 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.400 | 0.473 | 0.263 | ||||

| Coefficient (95% CI) | P Value | Coefficient (95% CI) | P Value | Coefficient (95% CI) | P Value | ||

| Provider and Beneficiary Composition | |||||||

| Bottom quartile FTE PCPs (<50) | −10.4 (−15.7 to −5.08) | <.001 | −8.61 (−13.7 to −3.54) | .001 | −8.92 (−14.3 to −3.53) | .001 | |

| Top quartile FTE Specialists (>300) | −7.00 (−12.3 to −1.73) | .01 | −8.08 (−13.0 to −3.12) | .002 | −4.44 (−9.73 to 0.839) | .01 | |

| Attributed beneficiaries per FTE PCPd | 0.042 (0.021 to 0.064) | <.001 | 0.038 (0.018 to 0.058) | <.001 | 0.032 (0.009 to 0.053) | .005 | |

| Attributed Beneficiaries (in 1,000s)d | 0.017 (−0.113 to 0.146) | .80 | 0.018 (−0.099 to 0.136) | .76 | 0.045 (−0.086 to 0.176) | .50 | |

| Proportion Minority Beneficiariesd | −24.1 (−37.1 to −11.0) | <.001 | −25.3 (−39.1 to −11.5) | <.001 | −33.4 (−46.9 to −19.8) | <.001 | |

| General Characteristics | |||||||

| Includes a hospital | 5.27 (1.28 to 9.26) | .01 | 7.14 (3.32 to 11.0) | <.001 | - | - | |

| Number of ACO contracts | - | - | −1.02 (−2.48 to 0.43) | .17 | - | - | |

| Medicare Advanced Payment Model Participant | 7.65 (2.19 to 13.1) | .006 | 6.62 (1.41 to 11.83) | .001 | 5.05 (−0.46 to 10.56) | .07 | |

| EHR and Quality Management Capabilities | |||||||

| EHR Capability Indexe | 16.0 (5.84 to 26.2) | .002 | 17.3 (7.58 to 27.0) | .001 | - | - | |

| ACO experience with quality reporting | - | - | 4.15 (0.056 to 8.24) | .047 | - | - | |

| B.) Wellness Screening | Modelc | Preferred | Expanded | Fully Expanded | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 127 | 110 | 104 | ||||

| F-Statistic | 5.77 | 4.42 | 3.44 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.185 | 0.201 | 0.192 | ||||

| Coefficient (95% CI) | P Value | Coefficient (95% CI) | P Value | Coefficient (95% CI) | P Value | ||

| Provider and Beneficiary Compositions | |||||||

| Bottom quartile FTE PCPs (<50) | −4.82 (−10.8 to 1.17) | .11 | −2.62 (−9.10 to 3.86) | .43 | −3.13 (−9.90 to 3.64) | .36 | |

| Top quartile FTE Specialists (>300) | −8.58 (−14.4 to −2.75) | .004 | −9.88 (−16.2 to −3.52) | .003 | −10.2 (−16.9 to −3.53) | .003 | |

| Attributed beneficiaries per FTE PCPd | 0.021 (−0.003 to 0.046) | .09 | 0.024 (−0.002 to 0.050) | .08 | 0.026 (−0.002 to 0.053) | .07 | |

| Attributed Beneficiaries (in 1,000s)d | 0.078 (−0.064 to 0.223) | .28 | 0.059 (−0.095 to 0.213) | .45 | 0.064 (−0.095 to 0.223) | .43 | |

| Proportion Minority Beneficiariesd | - | - | - | - | 5.80 (−13.0 to 24.6) | .54 | |

| General Characteristics | |||||||

| Includes a hospital | - | - | 3.19 (−1.03 to 8.09) | .20 | 3.02 (−2.14 to 8.18) | .25 | |

| Includes a community health center | 4.29 (−0.47 to 9.05) | .08 | 4.13 (−1.03 to 9.28) | .12 | 3.19 (−2.40 to 8.77) | .26 | |

| Medicare Advanced Payment Model Participant | 12.5 (6.32 to 18.6) | <.001 | 12.7 (6.10 to 19.3) | <.001 | 13.1 (6.15 to 20.1) | <.001 | |

| EHR and Quality Management Capabilities | |||||||

| EHR Capability Indexe | - | - | - | - | −5.08 (−2.55 to 8.07) | .44 | |

| ACO experience with quality reporting | - | - | 3.17 (−1.79 to 8.13) | .21 | 2.76 (−2.55 to 8.07) | .30 | |

FTE = full-time equivalent; PCP = primary care provider; EHR = electronic health record

Average of influenza vaccine, pneumococcus vaccine, colon cancer screen, and breast cancer screen measures (those with >0.4 loading on Factor 1).

Average of body mass index screen, tobacco screen/counseling, depression screen, and blood pressure screen measures (those with >0.4 loading on Factor 2).

Presented model results from multiple linear regression including all other variables with coefficients in the given column.

Variable derived using CMS data available only for MSSP ACOs (n=151).

EHR capability index (minimum of 0, maximum of 1) is derived from survey responses to seven questions on level of particular EHR capabilities

Figure 2.

Regression-adjusted means from the preferred models for Medicare ACO preventive care quality average performance on (A) disease prevention factor measures (influenza and pneumococcal vaccines, breast and colon cancer screenings) and (B) wellness screening factor measures (body mass index, tobacco, depression, and blood pressure screenings), varying presence and absence of dichotomous attributes, and mean levels of the top and bottom quartiles for continuous attributes.

Provider and Beneficiary Composition

We found the numbers of FTE PCPs and FTE specialists to have significant, but non-linear relationships with preventive care quality. When controlling for overall size in terms of number of beneficiaries, ACOs with relatively more specialists or fewer PCPs generally performed worse than their counterparts. Organizations in the bottom quartile of total PCPs (<50) performed an average of 10.4 points worse on disease prevention measures (95% CI −15.7–−5.1; p=<.001) relative to those with more PCPs. Inversely, ACOs in the top quartile of specialists (>300) performed an average of 7.0 points worse on disease prevention (95%CI −12.3–−1.7; p=.01) and 8.6 points worse on wellness screening (95%CI −14.4–−2.8; p=.004), relative to those with fewer specialists. These two characteristics were largely non-overlapping (one ACO met both criteria), thus these relationships were only observed for extremes of absolute counts, and not when considering the continuous ratio of PCPs to specialists.

Although we felt it an important control to retain in multivariate models, ACO size in terms of the number of attributed beneficiaries was not a significant predictor of preventive care quality performance in any model. However, in terms of the patient mix, the proportion of minority beneficiaries in the ACO had a significant negative associations with disease prevention performance, with regression-adjusted mean performance for ACOs in the upper quartile (average 27% minority) estimated to be 5.8 points higher on disease prevention measures (62.3 points, 95%CI 60.0–64.5 points) than those in the bottom quartile (average 3% minority) (56.4 points; 95%CI 54.0–58.9 points).

Finally, we included an interaction term representing the ratio of Medicare ACO beneficiaries to FTE PCPs in both preferred models. The relationship was statistically significant for disease prevention (p<.001) and near-significant for wellness screening (p<.1 in preferred model and all sensitivity analyses). In terms of regression-adjusted means, ACOs in the top quartile (average 308 ACO beneficiaries per PCP) outperformed ACOs in the bottom quartile (average of 72 ACO beneficiaries per PCP) by an average of 10.0 points on disease prevention measures (64.8 vs. 54.8 points, 95%CI 61.6–68.0 and 51.8 to 58.8) and 5.0 points on wellness screening measures (66.3 vs. 61.3 points; 95%CI 62.6–70.0 and 57.9–64.2).

General Characteristics

We identified some select general ACO characteristics associated with preventive care quality performance. Participation in the Advanced Payment Model, in which rural MSSPs were awarded upfront investment to assist with ACO formation, was associated with significantly better performance on both disease prevention (7.7 points; 95%CI 2.2–13.1; p=.006) and wellness screening measures (12.5 points; 95%CI 6.3–18.6; p<.001). Additionally for disease prevention measures, ACOs that include a hospital performed an average of 5.3 points better (95%CI 1.3–9.3; p=.01) than those without inpatient facilities.

Electronic Health Record (EHR) and Quality Management Capabilities

Increased EHR capabilities were associated with significantly better performance on disease prevention (p=.002). In terms of regression-adjusted means, ACOs in the top quartile of EHR capabilities (average index=0.95) significantly outperformed those in the bottom quartile (average index=0.57) by an average of 6.1 points on disease prevention measures (62.6 vs. 56.5 points; 95%CI 60.0–65.2 and 53.9–59.1). Past experience of the ACO with quality reporting (either pay-for-performance or public reporting) was associated with 4.2 points better performance on disease prevention measures in an expanded model sensitivity analysis (95% CI 0.1–8.2; p=.047). No variables representing these capabilities were found to be related to wellness screening performance.

Sensitivity Analyses

We used sensitivity analyses to assess the consistency of the estimates with slight variations on model and included sample size (Table 3), analyses using a survey estimate of beneficiary numbers (Table S.2), and using component measures and raw factors as the dependent variable (Table S.3). We identified subtle differences in magnitude and significance of associations, but the results generally validated our chosen preferred models, and did not meaningfully change our conclusions (see Table 3; see Tables S.2-S.3, Supplemental Digital Content 4 and 5, sensitivity analyses).

DISCUSSION

Overview

In our study of Medicare ACOs, exploratory factor analysis demonstrated that preventive care quality can be distilled into two subgroups of related measures: disease prevention (vaccines and cancer screenings) and wellness screening (annual primary care health checks). To put this result into context, we should consider how the related measure subgroups might differ in the processes required for delivery on quality. These two factors are closely related and share similar overarching steps in execution: (1) eligibility determination, (2) service administration, (3) documentation, and (4) data management. However, on closer examination, we identify divergences at each step. Wellness screening measures are required annually for all patients, are almost exclusively delivered by PCPs as a part of a wellness visit, and must be carefully documented, including follow up plans for positive screens, then data compiled across the ACOs PCPs. Alternatively, disease prevention measures are periodic or seasonal, involve disparate locations or providers (vaccines are administered by employers, hospitals, pharmacies, and other locations in addition to PCPs; cancer screenings require specialist care), and, while simple to document, data must be compiled across this wider network. As this conceptual model of preventive care quality performance might indicate, we found that performance on the two groups of measures, disease prevention and wellness screening, showed some similar relationships with respect to certain fundamental aspects of the ACO. However, we also identified subtle differences that might be expected from the aforementioned process divergences, and indicate more extensive associations between organizational characteristics and the more complex processes required for disease prevention measures.

We suspected that delivery of preventive services, required by many or all beneficiaries, might be related to the ACO’s physician and beneficiary composition. We chose to explicitly control for plan size by including the number of attributed beneficiaries in all models, despite the fact that it failed to reach statistical significance in any model. However, controlling for number of beneficiaries, performance on both factors was negatively associated with having either few PCPs, or more specialists, relative to other ACOs. Prior research has shown an association of higher PCP to specialist ratio with better preventive care quality,9 perhaps because beneficiaries attributed to the ACO from specialist visits often remain unconnected to the ACO’s PCPs and are vulnerable to missing preventive services.25,26 We did not observe that ratio to be related, but rather found ACOs at either workforce extreme (few PCPs, or many specialists) performed worse on preventive care quality.

Furthermore, we observed a consistent and significant association of a higher ACO beneficiary to PCP ratio with better performance on both factors. If we assume that a given PCP sees a similar total number of patients, then this ratio is proportional to the fraction of a PCP’s patients that are a part of the ACO. It makes sense logically that having more ACO patients on one’s panel would lead to more experience with, and a greater focus on, that ACO’s quality measures. Having more patients under different contracts in addition to the ACO may greatly complicate quality measurement, leading to provider concerns over the burdens of excessive quality measurement.27 One provider participating in a Pioneer ACO described facing 219 unique metrics across 6 risk-based contracts, forcing choices about where to direct early organizational efforts,28 and pushback against burdensome measurement led CMS to cut the number of ACO measures nearly in half in the final rule.29

While the number of beneficiaries was not significantly associated with performance, the composition of those beneficiaries showed a strong relationship. Evidence has shown persistence of racial disparities in quality for Medicare ACOs,30 and that minority patients face added practical barriers to obtaining preventive care, likely most relevant for invasive specialty services such as cancer screenings.31 In agreement with this notion, we found having higher proportion minority beneficiaries was significantly associated with worse performance on disease prevention measures. While racial mix was unrelated to performance on wellness screening measures, we observed a weak relationship with inclusion of community health centers in the ACO, which improve access to PCPs for disadvantaged populations but struggle to overcome patient-related barriers to cancer screening,32–34 though it only reached statistical significance in one sensitivity analysis.

Finally, several organizational characteristics influencing preventive care quality performance were related to ACO infrastructure or financing. One of the strongest and most consistent associations observed in models for both factors was the link between better performance and participation in the Medicare Advanced Payment Model. This program gave upfront financial investment directly to smaller MSSP ACOs centered on physician groups lacking inpatient facilities, which could go to labor or capital devoted to quality performance.35 Better performance by these ACOs on preventive care may be driven by the investment itself, or some other quality common to ACOs targeted for the program. Additionally, for disease prevention measures specifically, we observed significant relationships between certain components of ACO infrastructure, inclusion of a hospital and more extensive EHR capabilities, with better performance. Multiple intervention studies have found effectiveness of leveraging EHR for preventive care, often focusing on electronic reminders.35–40 Such technology for reminders and data management would be expected to have a greater impact on the more irregular and complex disease prevention preventive services.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of our study lie in the availability of quality data from the full population of Medicare ACOs, and our use of advanced methods to identify patterns of measure-to-measure variation and create composites. Additionally, we used extensive survey data that offers a unique early perspective ACO development. Despite survey responses from over two-thirds of the sample frame, our main limitation remains small sample size, due primarily to the relatively small number of organizations that were forerunners in forming Medicare ACOs, as well as sizable non-response for some survey questions of interest. We are also limited by a cross-sectional perspective of the first year of operation by organizations with varying degrees of pre-existing cohesiveness and differing timelines of development. However, this data represents a true and largely complete view of the early state of Medicare ACO development.

Implications and Conclusions

With the Affordable Care Act abolishing cost sharing, preventive care has become a priority as an easily defined, process-oriented quality target that can potentially save lives. Evidence is showing that, with time and experience, ACOs are beginning to improve quality and lower cost.41–44 Our findings indicate that preventive care quality performance can be distilled into two related, but subtly different components. We find associations of both factors with several ACO characteristics, particularly provider composition and upfront financing through the Medicare Advanced Payment model. ACOs may benefit in preventive care quality by ensuring that all patients, including those attributed to the ACO due to specialist visits, are connected to primary care providers, particularly those serving larger numbers of ACO beneficiaries. Furthermore, vaccine and cancer screening quality performance is more dependent on the organizational structure and composition of the ACO, likely due to greater complexity in determining eligibility and administering these services, relative to the annual primary care wellness screenings for obesity, tobacco use, depression, and hypertension. While ACOs with fewer resources or more minority beneficiaries may face added barriers to performance on vaccine and cancer screening administration, some of these organizational characteristics associated with improved performance, such as EHR capabilities and hospital inclusion, may represent choices made during ACO formation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the assistance of Bruce Link, PhD (Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University) and Jared Wasserman, MS (The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth) for their assistance in exploratory factor analysis methodology.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Funding Disclosure: We gratefully acknowledge funding from The Commonwealth Fund (20150034), the National Institute on Aging (R33AG044251), and a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Changes in Health Care Financing and Organization (HCFO) Initiative (#72646)

References

- 1.Dewilde LF, Russell C. The “Welcome to Medicare” physical: a great opportunity for our seniors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:292–294. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.6.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maciosek MV, Coffield AB, Flottemesch TJ, et al. Greater use of preventive services in U.S. health care could save lives at little or no cost. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:1656–1660. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2008.0701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cogan JA., Jr The Affordable Care Act’s preventive services mandate: breaking down the barriers to nationwide access to preventive services. J Law Med Ethics. 2011;39:355–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2011.00605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Committee for Quality Assurance. The State of Health Care Quality 2014. Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flocke SA, Litaker D. Physician practice patterns and variation in the delivery of preventive services. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:191–196. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0042-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solberg LI, Kottke TE, Brekke ML. Variation in clinical preventive services. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4:121–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colla CHBJ, Austin A, Skinner J. Hospital Competition, Quality, and Expenditures in the US Medicare Population. In: Dormont B, Milcent C, editors. Hospitals: Competition Under Fixed Prices (working title) Oxford University Press; 2015. expected. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung S, Lesser LI, Lauderdale DS, et al. Medicare annual preventive care visits: use increased among fee-for-service patients, but many do not participate. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34:11–20. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillies RR, Chenok KE, Shortell SM, et al. The impact of health plan delivery system organization on clinical quality and patient satisfaction. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:1181–1199. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00529.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pauly MV, Sloan FA, Sullivan SD. An economic framework for preventive care advice. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:2034–2040. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher ES, Staiger DO, Bynum JP, et al. Creating accountable care organizations: the extended hospital medical staff. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:w44–57. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.1.w44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnes AJ, Unruh L, Chukmaitov A, et al. Accountable care organizations in the USA: types, developments and challenges. Health Policy. 2014;118:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hacker K, Walker DK. Achieving population health in accountable care organizations. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1163–1167. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher ES, Shortell SM, Kreindler SA, et al. A framework for evaluating the formation, implementation, and performance of accountable care organizations. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:2368–2378. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shortell SM, Wu FM, Lewis VA, et al. A taxonomy of accountable care organizations for policy and practice. Health services research. 2014;49:1883–1899. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis VA, Colla CH, Carluzzo KL, et al. Accountable Care Organizations in the United States: market and demographic factors associated with formation. Health Serv Res. 2013;48:1840–1858. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berwick DM. Making good on ACOs’ promise--the final rule for the Medicare shared savings program. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1753–1756. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1111671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 2014 Group Practice Reporting Option (GPRO) Web Interface: Narrative Measure Specifications. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis K, Abrams M, Stremikis K. How the Affordable Care Act will strengthen the nation’s primary care foundation. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1201–1203. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1720-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClellan M, McKethan AN, Lewis JL, et al. A national strategy to put accountable care into practice. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:982–990. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pioneer Accountable Care Organization Model Performance Year 1 (2012) Quality Results. In: Services CfMaM, ed. CMS.gov2013

- 22.Medicare Shared Savings Program 2013 Quality Results. In: Services CfMaM, ed. CMS.gov2014

- 23.Medicare Shared Savings Program Accountable Care Organizations [database online] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2015. Data.CMS.gov. Updated March 4, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colla CH, Lewis VA, Shortell SM, et al. First national survey of ACOs finds that physicians are playing strong leadership and ownership roles. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:964–971. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis VA, McClurg AB, Smith J, et al. Attributing patients to accountable care organizations: performance year approach aligns stakeholders’ interests. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:587–595. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer H. Many accountable care organizations are now up and running, if not off to the races. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:2363–2367. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blumenthal D, McGinnis JM. Measuring Vital Signs: an IOM report on core metrics for health and health care progress. JAMA. 2015;313:1901–1902. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Addicott R. What accountable care organizations will mean for physicians. BMJ. 2012;345:e6461. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenthal MB, Cutler DM, Feder J. The ACO rules--striking the balance between participation and transformative potential. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:e6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1106012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson RE, Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Quality of care and racial disparities in medicare among potential ACOs. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:1296–1304. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2900-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walsh JM, McPhee SJ. A systems model of clinical preventive care: an analysis of factors influencing patient and physician. Health Educ Q. 1992;19:157–175. doi: 10.1177/109019819201900202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forrest CB, Whelan EM. Primary care safety-net delivery sites in the United States: A comparison of community health centers, hospital outpatient departments, and physicians’ offices. JAMA. 2000;284:2077–2083. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.16.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lasser KE, Ayanian JZ, Fletcher RH, et al. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening in community health centers: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-9-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roetzheim RG, Christman LK, Jacobsen PB, et al. A randomized controlled trial to increase cancer screening among attendees of community health centers. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:294–300. doi: 10.1370/afm.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ballard DJ, Nicewander DA, Qin H, et al. Improving delivery of clinical preventive services: a multi-year journey. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:492–497. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Casalino L, Gillies RR, Shortell SM, et al. External incentives, information technology, and organized processes to improve health care quality for patients with chronic diseases. JAMA. 2003;289:434–441. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dexter PR, Perkins S, Overhage JM, et al. A computerized reminder system to increase the use of preventive care for hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:965–970. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa010181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shea S, DuMouchel W, Bahamonde L. A meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials to evaluate computer-based clinical reminder systems for preventive care in the ambulatory setting. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1996;3:399–409. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1996.97084513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stone EG, Morton SC, Hulscher ME, et al. Interventions that increase use of adult immunization and cancer screening services: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:641–651. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-9-200205070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilkinson C, Champion JD, Sabharwal K. Promoting preventive health screening through the use of a clinical reminder tool: an accountable care organization quality improvement initiative. J Healthc Qual. 2013;35:7–19. doi: 10.1111/jhq.12024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McWilliams JM, Chernew ME, Landon BE, et al. Performance differences in year 1 of pioneer accountable care organizations. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1927–1936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1414929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nyweide DJ, Lee W, Cuerdon TT, et al. Association of Pioneer Accountable Care Organizations vs traditional Medicare fee for service with spending, utilization, and patient experience. JAMA. 2015;313:2152–2161. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pham HH, Cohen M, Conway PH. The Pioneer accountable care organization model: improving quality and lowering costs. JAMA. 2014;312:1635–1636. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song Z, Rose S, Safran DG, et al. Changes in health care spending and quality 4 years into global payment. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1704–1714. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1404026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.