Abstract

Achieving a smooth and rapid emergence from general anesthesia is of particular importance for neurosurgical patients and is a clinical goal for neuroanesthesiologists. Recent data suggest that the process of emergence is not simply the mirror image of induction, but rather controlled by distinct neural circuits. In this narrative review, we discuss (1) hysteresis, (2) the concept of neural inertia, (3) the asymmetry between the neurobiology of induction and emergence, and (4) recent attempts at actively inducing emergence.

Achieving a smooth and rapid emergence from general anesthesia is a desired goal for all surgical patients but of particular importance for neurosurgical patients because of the need to identify rapidly any structural lesions attributable to the intervention. Traditionally, it has been assumed that the induction of and emergence from general anesthesia are mirror images of one another. The asymmetry—or “hysteresis”—of anesthetic concentrations required for induction vs. emergence has long been recognized, but has been attributed to pharmacokinetic characteristics. Emerging evidence suggests that this asymmetry may reflect a distinct neurobiology of the two processes and that the neural circuits mediating induction do not entirely overlap with the neural circuits mediating emergence.1 Furthermore, there has been a renewed interest in the modulation of emergence mechanisms in order to gain active control over what is currently a passive process. This stems in part from the sequelae of delayed emergence such as delayed identification of acute neurosurgical pathology and operating room inefficiency. Although short-acting agents such as remifentanil may expedite emergence, remifentanil has been associated with hyperalgesia,2,3 and its use has not consistently demonstrated fast emergence from neurosurgical anesthesia.4,5 Thus, patients may benefit clinically from an evolved strategy of anesthetic emergence informed by the neurobiology of arousal states. In this article, we provide a focused narrative review of this recent neurobiology as well as a discussion of its potential relevance to clinical neuroanesthesia.

The Concept of Hysteresis

First coined by Sir James Alfred Ewing, the term “hysteresis” is derived from an ancient Greek word meaning “deficiency” or “lagging behind.” Hysteresis is characteristic of dynamic systems in which response to a stimulus in one direction does not follow the same path in the opposite direction. It is a widely occurring phenomenon, found in both natural and constructed systems. Two key components of hysteresis are (1) “lagging,” where changes in output lag changes in input, and (2) “rate independence,” where the input-output relationship depends on the value of the input rather than the speed at which the input is changed.6 In physics, there is hysteresis in the thermodynamic phase changes of water freezing and ice melting, which results in distinct temperatures for the two transitions. As a biological example familiar to anesthesiologists, hysteresis is seen with the pressure-volume loop during respiratory cycle. The pressure volume curves of a respiratory cycle do not coincide to create a sigmoidal curve, but instead generate a hysteresis loop. The area of the loop represents the energy wasted as heat during stretching and recoil of lung tissue over a complete respiratory cycle7 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The hatched area plus the triangular area ABC represents work of breathing (pressure multiplied by volume). Triangular area ABC is the work required to overcome elastic forces, whereas the hatched area is the work required to overcome airflow or frictional resistances.

Hysteresis has long been observed in the process of induction and emergence, with the anesthetic concentration at which consciousness is lost being higher than the anesthetic concentration at which consciousness is regained. Of relevance to the thermodynamic example of water freezing and ice melting, anesthetic drug hysteresis is predicted by a thermodynamic model of anesthetic state transitions.8 However, hysteresis has classically been thought to relate to pharmacology and is usually obscured in daily anesthetic practice. Single-agent general anesthesia with controlled and symmetrical up- and down-titration is uncommon in this era of balanced anesthetic technique. Furthermore, induction is typically rapid due to intravenous bolus dosing while emergence is relatively slower due to inhaled anesthetic clearance and the presence of opioids for postoperative analgesia. Highly controlled experimental studies in the recent literature provide a clearer picture of anesthetic hysteresis and suggest that the entrance to and exit from anesthetic states are controlled by distinct neural circuits.1,8

Neural Inertia

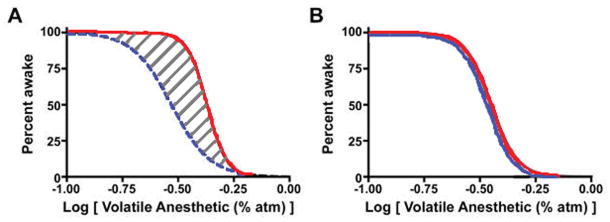

“Neural inertia” was proposed by Dr. Max Kelz as a fundamental and biologically conserved process through which neural circuits of the central nervous system resist behavioral state transitions, such as the shift from conscious to unconscious states.1 Neural inertia would help maintain aroused or depressed states of consciousness and create resistance to rapid and potentially catastrophic transitions between these states (such as wake-to-sleep transitions observed in patients with narcolepsy). In the context of general anesthesia, the area under the curve of an anesthetic dose-response hysteresis loop can serve as a practical surrogate of neural inertia (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Examples of path-dependent (A) and path-independent (B) processes. Panel A shows hysteresis with distinct curves for anesthetic induction and emergence; the hatched area between the two is a surrogate for neural inertia. Solid black curve represents individuals entering unconsciousness state while dotted black curve is of same individuals entering wake state, both of which are function of anesthetic dose. Panel B, by contrast, shows no hysteresis, with the induction and emergence curves completely overlapping. Reproduced with permission from Friedman et al.6 (Open access journal).

Using two different species, Friedman et al demonstrated that hysteresis and, in turn, neural inertia were susceptible to genetic and pharmacologic manipulation.1 At effector sites in the central nervous system, catecholamines (in particular, norepinephrine) were shown to play a role in how the brain overcomes the barriers to emergence. Dopamine β-hydroxylase (Dbh) knockout mice are unable to synthesize norepinephrine and epinephrine. These animals demonstrated increased sensitivity to induction by isoflurane but a profoundly altered threshold to emergence, with a significant increase in neural inertia (because the delayed emergence was out of proportion to the potentiated induction). The Drosophila melanogaster Shaker potassium-channel mutants, which are observed to sleep less, exhibited significant resistance to induction of anesthesia by isoflurane with a striking phenotype of reduced neural inertia.1

The discovery of neural inertia in two different species begs the question of whether such a behavioral state barrier exists in humans. Although anesthetic hysteresis is known to occur in humans, it is unclear whether neural inertia is altered in clinical situations associated with, for example, delayed emergence or unexpected resistance to anesthetic effects. Carefully controlled studies are warranted to confirm the principle of neural inertia in humans.

Regulation of neural inertia

The concept of neural inertia has shed light on how the brain transitions between wakeful and unconscious states in vertebrates and invertebrates. Mechanisms underlying neural inertia and processes that regulate this barrier have yet to be fully elucidated. Bistability is manifested behaviorally in a system that exists in either one of two stable states, e.g., wakefulness and general anesthesia. A robust, bistable switch has been hypothesized to regulate transitions between wakefulness and natural sleep9 and, similarly, between wakefulness and anesthetic-induced unconsciousness. Using four different genetic mutations of fruit flies that encode hyperpolarizing Shaker potassium channels, Joiner et al identified a bistable neural switch that might play a role in regulating neural inertia.10 Loss-of-function mutations led to a collapse of neural inertia, hyperaroused mutants did not show altered neural inertia and sleep-deprived flies displayed increased neural inertia. The investigators proposed that upon entry into the waking or anesthetized state, distinct neural feedback mechanisms are activated in order to shift drug sensitivity towards stabilizing a particular state. The feedback mechanism may be mutual inhibition or positive reinforcement by neurons that facilitate waking, anesthetized or sleep states. Distinct anatomical neural circuits were posited to exist and play a role in control of bistability.

Implications of neural inertia for neuroanesthesia

Neural inertia may provide greater insight into mechanisms of drug-induced unconsciousness and the return of normal consciousness and cognition. For example, does a widened neural inertial barrier explain the delayed emergence that is often observed after intracranial surgery under general anesthesia? Are there synergistic effects of neurosurgery and anesthesia that result in delayed emergence as opposed to one (e.g., awake craniotomy) or the other (e.g., non-neurologic surgery under general anesthesia) in isolation? The mechanisms underlying neural inertia may shed light on this interface between pharmacology and subclinical neural pathology, as well as frank pathological states like coma or persistent vegetative states.

On the other end of the spectrum, the genetic collapse or narrowing of neural inertia may help explain why certain individuals are at risk for awareness under general anesthesia. It has been shown, for example, that patients with a history of awareness have a 5-fold adjusted increase in risk for a subsequent awareness event.33 This susceptible population may be defined by genetic polymorphisms that affect neural circuits regulating neural inertia.

Awareness under general anesthesia, postoperative confusion, delirium and delayed emergence are associated with significant morbidity and lead to stress disorders, prolonged operating room or hospital stay and increased healthcare costs. An improved understanding of the clinical implications and identification of neural inertia patterns could lead to anesthetic techniques and drugs tailored to individual phenotypes, which may help offset anesthesia related morbidity.

In summary, neural inertia represents a barrier that creates resistance to behavioral state transitions. Consistent with this hypothesis, increased sensitivity to induction of anesthesia cannot be used to predict emergence from anesthesia. Feedback and bistability facilitate the range of reversibility between the waking and anesthetized or sleep states. The asymmetry or “hysteresis” of anesthetic concentrations required for induction and emergence from anesthesia is likely due to distinct neurochemical systems that do not overlap entirely.

Distinct Neurochemical Control of Induction and Emergence

In this section, we highlight three neurochemical systems that play an asymmetric role in anesthetic induction and emergence: acetylcholine in the thalamus, orexins in the hypothalamus and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the pontine reticular formation. The pontine reticular formation is located in the brainstem and, through various projections, plays a key role in arousal of the cortex.11,12 The hypothalamus is critical for control of the sleep-wake cycle and contains neuronal populations that, when activated, induce unconsciousness (e.g., ventrolateral preoptic nucleus)13,14 or arousal (e.g. orexin neurons or tuberomammillary nucleus).15,16 The thalamus serves as a processing station for incoming sensory information, a relay for ascending arousal signals and a key site that facilitates the integration of cortical computation. As such, the pons, hypothalamus and thalamus may all play a critical role in anesthetic induction and recovery.

Cholinergic system in thalamus

The thalamus plays a major role in sensory and information integration in the brain.17 Because of its theorized role in the conscious experience,18 it has become a major focus of research involving anesthetic-induced unconsciousness.19,20 Furthermore, because of the nearly uniform depression of thalamic function during exposure to sedative-hypnotics, Alkire et al previously proposed a thalamocortical switch for consciousness and anesthesia.21 However, there appears to be an asymmetry between the “on” and “off” functions for consciousness with cholinergic function in the thalamus.

The role of nicotinic cholinergic agonism in the central medial thalamus (CMT) in reversing loss of consciousness was described by Alkire et al.22 Using a rat model, the investigators tested the effect of cholinergic manipulation in the CMT on loss of righting reflex (LORR)—a surrogate for unconsciousness in rodents—induced by sevoflurane. Nicotine binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and, when microinjected in the CMT, was shown to reverse the effect of sevoflurane as evidenced by a return of the righting reflex despite a consistent delivery of the anesthetic. In rats pretreated with nicotinic antagonist mecacylamine, nicotine microinjection did not reverse the LORR response. A similar reversal of anesthetic effect was observed after the microinfusion of antibodies to voltage-gated potassium channels, which are highly susceptible to modulation by anesthetics,23 into the CMT.24

Importantly, however, microinfusion of mecamylamine alone prior to sevoflurane administration did not affect LORR, suggesting that the nicotinic cholinergic system in the CMT can be hijacked as an “on” switch for recovery of consciousness but not an “off” switch for anesthetic-induced unconsciousness.

Orexinergic neurons in the hypothalamus

Orexinergic neurons are located in the hypothalamus, innervate numerous arousal centers and cortical sites, and play a critical role in initiation, maintenance and stabilization of wakefulness.25 Indeed, deficiencies of orexinergic signaling result in narcolepsy across a number of species.26–28 A series of studies describes the role of the wake-active orexin system in modifying the anesthetized state.29 Using a genetically-engineered mouse model, Kelz and colleagues demonstrated the effects of commonly used volatile agents isoflurane and sevoflurane on orexinergic neural circuits. The mice were exposed to oxygen as a control, 1.25% isoflurane in oxygen, or 2.14% sevoflurane in oxygen for 2 hours. Isoflurane showed a 30% reduction and sevoflurane a 50% reduction in c-Fos expression—a marker of metabolic cell activity—in orexinergic neurons. The actions of these volatile agents were specific to wake-active orexinergic neurons in the hypothalamus as evidenced by the lack of inhibition of adjacent melanin concentrating hormone neurons. Genetic ablation (murine narcolepsy model) and pharmacological interventions (orexin receptor antagonist SB-334867-A) to suppress orexinergic neural circuits did not alter induction of anesthesia but resulted in delayed emergence from anesthesia. This seminal study provides clear evidence that emergence from the effects of halogenated ethers involves different neural circuits and neural substrates compared to induction. The wake-promoting and wake-stabilizing orexinergic system appears to specifically affect recovery from anesthesia while induction of anesthesia is unaffected. However, it must be noted that orexinergic neurons appear to play no role in halothane-induced unconsciousness or recovery.1 Thus, the asymmetric role of orexinergic signaling cannot be generalized to all inhaled anesthetics.

GABA in the pontine reticular formation

The foregoing examples demonstrate situations in which a neurochemical/neuroanatomic area is important for emergence from anesthesia but plays little or no role in the induction of anesthesia. Vanini et al recently demonstrated that the reverse can happen as well.30 Anesthetic traits induced by isoflurane have been correlated with decreases in GABA in the pontine reticular formation.31 This is counterintuitive, since GABA is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain and is increased in both sleep and anesthetic states. However, the pontine reticular formation is a site where low GABA is associated with depressed consciousness while high GABA is associated with states of cortical arousal.32 Recently, it has been found that pharmacological modulation of GABA in the pontine reticular formation can affect induction of isoflurane-induced unconsciousness (e.g., decreasing GABA levels potentiates the anesthetic), but plays no apparent role in emergence.30 This serves as another compelling example of how the neural circuitry of anesthetic emergence is distinct from that of anesthetic induction.

Inducing Emergence

Neural inertia provides a theoretical and neurobiological framework to help us understand the process of anesthetic emergence. Current efforts have been directed at hijacking the putative circuits involved in order to control anesthetic emergence. Traditionally, the induction of general anesthesia has been an active and rapid process while emergence, by contrast, has been a passive process that varies in length and may be defined by different neural trajectories of recovery.34–36 Recently, there has been more experimental focus on actively and rapidly “inducing emergence,” to create the parallel control in state transition currently found during induction of anesthesia.37,38 In this section we highlight two neurochemical systems that may play a role in inducing emergence from anesthesia.

Acetylcholine

As discussed, data from animal studies suggest that altered central cholinergic transmission, specifically in the CMT, can reverse the state of general anesthesia.22 The role of centrally-acting anticholinesterases in reversal of or antimuscarinic agents in blocking reversal of, anesthetic-induced unconsciousness has been explored in various animal and human studies. One such study using healthy human volunteers was described by Meuret et al.39 Physostigmine, a centrally-acting anticholinesterase, and scopolamine, a centrally-acting antimuscarinic antagonist, were used to restore or block reversal of propofol-induced unconsciousness. Physostigmine administration was accompanied by increase in amplitude of auditory steady-state response and bispectral index values.

Volunteers pretreated with scopolamine showed delayed emergence from anesthesia, suggesting blockade of physostigmine-induced reversal of propofol induced unconsciousness. Scopolamine prevented recovery of the neurophysiological indices as well.39 Importantly, in another study involving positron emission tomography, physostigmine-reversal of propofol anesthesia was correlated with increased cerebral blood flow in the thalamus and an area of the posterior parietal cortex (precuneus).40 Although less reliable compared to its effects on propofol, physostigmine partially reversed sevoflurane-induced loss of consciousness.41

Dopamine

Monoamine neurotransmitters, including dopamine, norepinephrine and histamine, promote arousal through pathways arising in pons, midbrain and hypothalamus.9,42 Methylphenidate acts by inhibiting dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake transporters, thereby increasing dopaminergic and adrenergic neurotransmission.43 Using a rat model, Solt et al44 explored the role of methylphenidate in inducing emergence from isoflurane anesthesia. While maintaining a continuous inhaled concentration of isoflurane at 1.5%, the median time to emergence (return of righting reflex) was 91s in rats that received IV methylphenidate (5mg/kg) versus 280s for rats that received IV normal saline. Methylphenidate induced a return in the electroencephalogram to an active θ dominant pattern, which is characteristic of waking states in rodents. Importantly, methylphenidate was also shown to reverse the effects of propofol, suggesting that its effects are independent of increasing ventilation.45

In a separate group of rats, IV droperidol, a dopaminergic antagonist, was administered 5 minutes prior to administration of IV methylphenidate; with pretreatment, none of the rats had return of righting reflex. The electroencephalogram continued to be in a δ dominant pattern, as seen in the anesthetized unconscious state. These data indicate that the observed effects of methylphenidate were mediated by antagonism of dopaminergic transmission. Solt’s laboratory later confirmed this hypothesis by demonstrating that a D1 dopaminergic agonist could reverse the effects of isoflurane.38 More recently, it was shown that electrical stimulation of the ventral tegmental area—but not the substantia nigra—could recapitulate this reversal effect37 suggesting that this particular source of dopamine is the critical arousal signal. A clinical trial to test the effects of IV methylphenidate in surgical patients recovering from general anesthesia is currently planned (Clinical Trial: NCT02051452). Carefully conducted clinical trials in humans will help answer the question as to whether the reanimation observed in animal studies after administration of arousal-promoting drugs is actually associated with improved cognition.

Conclusion

There has been a recent shift in neuroscientific attention from the mechanisms of anesthetic induction to the mechanisms of anesthetic emergence. Accumulating data demonstrate that the neurobiology of the two processes may not be mirror images but rather under the control of distinct neural circuits. These observations have given rise to the concept of neural inertia, which is hypothesized to be a barrier between behavioral state transitions. Neural inertia can have genetic and pharmacological influences, and may account for variations in emergence patterns. Recently, there has been an increased focus on “inducing emergence” to achieve control over the process that parallels that of inducing anesthesia. The ability to actively initiate the process of emergence may facilitate the identification of acute neurological pathology that requires urgent surgical intervention. Well-controlled clinical trials in humans are essential to establish the role of drugs such as physostigmine or methylphenidate in the reversal of general anesthesia. Such approaches may hold particular promise for neuroanesthesiologists, who may one day have greater control over the process of emergence based on the neurobiology of arousal.

References

- 1.Friedman EB, Sun Y, Moore JT, et al. A conserved behavioral state barrier impedes transitions between anesthetic-induced unconsciousness and wakefulness: evidence for neural inertia. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angst MS, Koppert W, Pahl I, et al. Short-term infusion of the mu-opioid agonist remifentanil in humans causes hyperalgesia during withdrawal. Pain. 2003;106:49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joly V, Richebe P, Guignard B, et al. Remifentanil-induced postoperative hyperalgesia and its prevention with small-dose ketamine. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:147–55. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200507000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Necib S, Tubach F, Peuch C, et al. Recovery from anesthesia after craniotomy for supratentorial tumors: comparison of propofol-remifentanil and sevoflurane-sufentanil (the PROMIFLUNIL trial) J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2014;26:37–44. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e31829cc2d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magni G, Baisi F, La Rosa I, et al. No difference in emergence time and early cognitive function between sevoflurane-fentanyl and propofol-remifentanil in patients undergoing craniotomy for supratentorial intracranial surgery. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2005;17:134–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ana.0000167447.33969.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris KA. What is Hysteresis? Appl Mech Rev. 2011;64:050801–14. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Escolar JD, Escolar A. Lung hysteresis: a morphological view. Histol Histopathol. 2004;19:159–66. doi: 10.14670/HH-19.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steyn-Ross ML, Steyn-Ross DA, Sleigh JW. Modelling general anaesthesia as a first-order phase transition in the cortex. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2004;85:369–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saper CB, Scammell TE, Lu J. Hypothalamic regulation of sleep and circadian rhythms. Nature. 2005;437:1257–63. doi: 10.1038/nature04284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joiner WJ, Friedman EB, Hung HT, et al. Genetic and anatomical basis of the barrier separating wakefulness and anesthetic-induced unresponsiveness. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lydic R, Baghdoyan HA. Sleep, anesthesiology, and the neurobiology of arousal state control. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:1268–95. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200512000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones BE. Arousal systems. Front Biosci. 2003;8:s438–51. doi: 10.2741/1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sherin JE, Shiromani PJ, Mccarley RW, et al. Activation of ventrolateral preoptic neurons during sleep. Science. 1996;271:216–9. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5246.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaus SE, Strecker RE, Tate BA, et al. Ventrolateral preoptic nucleus contains sleep-active, galaninergic neurons in multiple mammalian species. Neuroscience. 2002;115:285–94. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00308-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eriksson KS, Sergeeva O, Brown RE, et al. Orexin/hypocretin excites the histaminergic neurons of the tuberomammillary nucleus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9273–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09273.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bayer L, Eggermann E, Serafin M, et al. Orexins (hypocretins) directly excite tuberomammillary neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:1571–5. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Llinas R, Ribary U. Consciousness and the brain. The thalamocortical dialogue in health and disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;929:166–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edelman GM. Naturalizing consciousness: a theoretical framework. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5520–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931349100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu X, Lauer KK, Ward BD, et al. Differential effects of deep sedation with propofol on the specific and nonspecific thalamocortical systems: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:59–69. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318277a801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mashour GA, Alkire MT. Consciousness, anesthesia, and the thalamocortical system. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:13–5. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318277a9c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alkire MT, Haier RJ, Fallon JH. Toward a unified theory of narcosis: brain imaging evidence for a thalamocortical switch as the neurophysiologic basis of anesthetic-induced unconsciousness. Conscious Cogn. 2000;9:370–86. doi: 10.1006/ccog.1999.0423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alkire MT, Mcreynolds JR, Hahn EL, et al. Thalamic microinjection of nicotine reverses sevoflurane-induced loss of righting reflex in the rat. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:264–72. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000270741.33766.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lioudyno MI, Birch AM, Tanaka BS, et al. Shaker-related potassium channels in the central medial nucleus of the thalamus are important molecular targets for arousal suppression by volatile general anesthetics. J Neurosci. 2013;33:16310–22. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0344-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alkire MT, Asher CD, Franciscus AM, et al. Thalamic microinfusion of antibody to a voltage-gated potassium channel restores consciousness during anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:766–73. doi: 10.1097/aln.0b013e31819c461c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alexandre C, Andermann ML, Scammell TE. Control of arousal by the orexin neurons. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23:752–9. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin L, Faraco J, Li R, et al. The sleep disorder canine narcolepsy is caused by a mutation in the hypocretin (orexin) receptor 2 gene. Cell. 1999;98:365–76. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81965-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siegel JM. Narcolepsy: a key role for hypocretins (orexins) Cell. 1999;98:409–12. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81969-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishino S, Ripley B, Overeem S, et al. Hypocretin (orexin) deficiency in human narcolepsy. Lancet. 2000;355:39–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05582-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelz MB, Sun Y, Chen J, et al. An essential role for orexins in emergence from general anesthesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1309–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707146105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vanini G, Nemanis K, Baghdoyan HA, et al. GABAergic transmission in rat pontine reticular formation regulates the induction phase of anesthesia and modulates hyperalgesia caused by sleep deprivation. Eur J Neurosci. 2014;40:2264–73. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vanini G, Watson CJ, Lydic R, et al. Gamma-aminobutyric acid-mediated neurotransmission in the pontine reticular formation modulates hypnosis, immobility, and breathing during isoflurane anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:978–88. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31818e3b1b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vanini G, Wathen BL, Lydic R, et al. Endogenous GABA levels in the pontine reticular formation are greater during wakefulness than during rapid eye movement sleep. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2649–56. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5674-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aranake A, Gradwohl S, Ben-Abdallah A, et al. Increased risk of intraoperative awareness in patients with a history of awareness. Anesthesiology. 2013;119:1275–83. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee U, Muller M, Noh GJ, et al. Dissociable network properties of anesthetic state transitions. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:872–81. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31821102c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hight DF, Dadok VM, Szeri AJ, et al. Emergence from general anesthesia and the sleep-manifold. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014;8:146. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2014.00146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chander D, Garcia PS, Maccoll JN, et al. Electroencephalographic variation during end maintenance and emergence from surgical anesthesia. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106291. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solt K, Van Dort CJ, Chemali JJ, et al. Electrical stimulation of the ventral tegmental area induces reanimation from general anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2014;121:311–9. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor NE, Chemali JJ, Brown EN, et al. Activation of D1 dopamine receptors induces emergence from isoflurane general anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:30–9. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318278c896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meuret P, Backman SB, Bonhomme V, et al. Physostigmine reverses propofol-induced unconsciousness and attenuation of the auditory steady state response and bispectral index in human volunteers. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:708–17. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200009000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xie G, Deschamps A, Backman SB, et al. Critical involvement of the thalamus and precuneus during restoration of consciousness with physostigmine in humans during propofol anaesthesia: a positron emission tomography study. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:548–57. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Plourde G, Chartrand D, Fiset P, et al. Antagonism of sevoflurane anaesthesia by physostigmine: effects on the auditory steady-state response and bispectral index. Br J Anaesth. 2003;91:583–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brown EN, Purdon PL, Van Dort CJ. General anesthesia and altered states of arousal: a systems neuroscience analysis. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:601–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heal DJ, Cheetham SC, Smith SL. The neuropharmacology of ADHD drugs in vivo: insights on efficacy and safety. Neuropharmacology. 2009;57:608–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Solt K, Cotten JF, Cimenser A, et al. Methylphenidate actively induces emergence from general anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:791–803. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31822e92e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chemali JJ, Van Dort CJ, Brown EN, et al. Active emergence from propofol general anesthesia is induced by methylphenidate. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:998–1005. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182518bfc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]